GEORGE BUCHANAN,

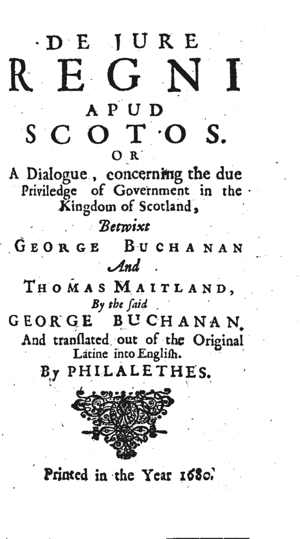

De jure regni apud Scotos, or, A dialogue, concerning the due priviledge of government in the kingdom of Scotland, betwixt George Buchanan and Thomas Maitland (1680)

|

|

[Created: 14 October, 2024]

[Updated: 14 October, 2024] |

The Guillaumin Collection

|

This title is part of “The Guillaumin Collection” within “The Digital Library of Liberty and Power”. It has been more richly coded and has some features which other titles in the library do not have, such as the original page numbers, formatting which makes it look as much like the original text as possible, and a citation tool which makes it possible for scholars to link to an individual paragraph which is of interest to them. These titles are also available in a variety of eBook formats for reading on portable devices. |

Source

, De jure regni apud Scotos, or, A dialogue, concerning the due priviledge of government in the kingdom of Scotland, betwixt George Buchanan and Thomas Maitland by the said George Buchanan ; and translated out of the original Latine into English by Philalethes (1680).http://davidmhart.com/liberty/OtherLiberals/Buchanan/1680-Dialogue/index.html

George Buchanan, De jure regni apud Scotos, or, A dialogue, concerning the due priviledge of government in the kingdom of Scotland, betwixt George Buchanan and Thomas Maitland by the said George Buchanan ; and translated out of the original Latine into English by Philalethes (1680).

This title is also available in a facsimile PDF of the original and various eBook formats - HTML, PDF, and ePub.

This book is part of a collection of works by George Buchanan (1506-1582).

The TRANSLATOR To the READER.↩

Candide Reader

I Have presumed to trouble your attention with the Ceremony of a Preface, the end and designe of which is not to usher in my Translation to the world with curious embellishments of Oratory (that serving only to gratify, or enchaunt a Luxuriant fancy) but allennatly to apologize for it, in case a Zoilus, or a Momus, shall happen to peruse the same. Briefly, then I reduce all that either of these will (as I humbly perceive) object against this my Work to these two Generals, Prevarication and Ignorance. First, they will call me a Prevaricator or prevaricating Interpreter, and that upon two accounts. 1. Because I have (say they) sophisticated the genuine sense and meaning of the [3] learned Author, by interpreting and foisting in spurious words of mine own. Secondly, That I have quite alienated the literal sense in other places by a too Paraphrastical exposition. To the first I answer, that none are ignorant, that the Original of this piece is a lofty Laconick stile of Latine: Now I once having undertaken Provinciam Interpretis, behoved to render my interpretation somewhat plain, and obvious, which I could never do in some places, without adding some words (claritatis gratiâ) but alwayes I sought out the scope (as far as my shallow capacity could reach) and suited them thereunto. Wherein I am hopfull, that no ingenuous impartial Reader not prepossessed wiih prejudice against the matter contained in the Original, and consequently against the Translation thereof, will find much matter of quarrell upon that account, if he will but take an overly view of the Original, and so compare the Translation therewith. For I have been very sparing in adding ought of my own. To the second branch of the first challenge I answer briefly; there are none who have the least smattering of common sense, but know wel enough, that it is morally impossible [3] for an Interpreter to make good language of any Latine piece, if he shall alwayes verbum verbo redere; I mean, if he adhere so close to the very rigour of the Original, as to think it illicite to use any Paraphrase, although the succinctness and summary comprehensiveness of the Original stile even cry aloud for it, as it were; but to silence in a word these Critical Snarlers, where ever I have used any Paraphrase, I likewise have set down the exposition ad verbum (to the best of my knowledge) as near as I could.

The Second Challenge is of Ignorance, & that because I have passed by some Latine verses of Seneca, which are at the end of this Dialogue, containing the Stoicks description of a King, without translating them into English. Now, true it is I have done so, not because I knew not how to interpret them (for I hope, Candide Readers at least will not so judge of me) but because I thought it not requisite to meddle with them, unless I could have put as specious a lustre upon them, as my pen would have pulled off them (for otherwise I would have greatly injured them) which could never be done without a sublime veine of Poesy, wherein I ingenuously profess ignorance: [4] so that if the last challenge be thus understood, transeat, because

Nec fonte labra prolui Cabalino,

Nec in bicipiti somniasse Parnasso,

Memini ut repente sic Poeta prodirem.

And hence it is, that all the Latine verses, which occurre in this Dialogue, are by me translated into Prose, as the rest: But I fear I have wearied your patience too long already, and therefore I will go no further, I wish you satisfaction in the Book, and so

Vive & Vale.

A Dialogue treating of the Jus, or Right, which the Kings of Scotland have for exercising their Royal Power.

George Buchanan, Author

[The Epistle Dedicatory'↩

George Buchanan to King James, the Sixth of that name King of Scots, wisheth all health and happiness.

I WROTE several years ago, when among us affaires were very turbulent, a dialogue of the right of the Scots Kings, wherin I endeavoured to explain from the very beginning (if I may so say) what right, or what authority both kings and people have one with another. [Page] Which book, when for that time it seemed somewhat profitable, as shutting the mouths of some who, more by importunat clamours at that time, than what was right, inveighed against the course of affaires, requiring they might be levelled according to the rule of right reason; but matters being somewhat more peaceable, I also having laid down my armes, very willingly devoted my self to publick concord. Now having lately fallen upon that disputation, which I found amongst my papers, and perceiving therein many things which might be necessary for your age (especially you being placed in that part of humane affaires), I thought good to publish it, that it might be a standing witness of mine affection towards you, and admonish you of your duty toward your subjects. Now many things perswaded me that this my endeavour should not be in vain: especially your age not yet corrupted by prave opinions, and inclination far above your years for undertaking all heroicall and noble attempts, spontaneously [Page] making haste thereunto, and not only your promptitude in obeying your instructors and governours, but all such as give you sound admonition, and your judgment and diligence in examining affaires, so that no mans authority can have much weight with you unless it be confirmed by probable reason. I do perceive also that <as> you, by a certain natural instinct, do so much abhorre flattery, which is the nurse of tyranny and a most grievous plague of a kingdome, so as you do hate the Court solaecismes and barbarismes no less than those that seeme to censure all elegancy do love and affect such things, and everywhere in discourse spread abroad, as the sawce thereof, these titles of Majesty, Highness, and many other unsavoury compellations. Now albeit your good natural disposition and sound instructions, wherein you have been principled, may at present draw you away from falling into this errour, yet I am forced to be some what jealous of you, lest bad company, the fawning foster-mother of all vices, draw aside your soft and tender mind into the [Page] worst part; especially seeing I am not ignorant how easily our other senses yeeld to seduction. This book therefore I have sent unto you to be not only your monitor, but also an importunat and bold exactor, which in this your tender and flexible years may conduct you in safety from the rocks of flattery, and not only may admonish you, but also keep you in the way you are once entred into: and if at any time you deviat, it may reprehend and draw you back. The which if you obey, you shall for your self and for all your subjects acquire tranquillity and peace in this life, and eternal glory in the life to come. Farewell, from Stirveling, the tenth day of January in the ear of mans salvation one thousand five hundred seventy-nine.

[1]

A DIALOGUE TREAT OF THE IUS OR RIGHT OF GOVERNMENT AMONGST THE SCOTS.↩

PERSONS, GEORGE BUCHANAN AND THOMAS MAITLAND

THOMAS Maitland beeing of late returned home from France, and I seriously enquiring of him the state of affaires there, began (for the love I bear to him) to exhort him to continue in that course he had taken to honour, and to entertain that excellent hope in the progress of his studies. “For if I, being but of an ordinary spirit and almost of no fortune, in an illiterat age, have so wrestled with the iniquity of the times, as [2] that I seeme to have done somewhat: then certainly they who are born in a more happy age, and who have maturity of years, wealth and pregnancy of spirit, ought not to be deterred by paines from noble designes, nor can such despair, beeing assisted by so many helps. They should therefore go on with vigour to illustrat learning, and to commend themselves and those of their nation to the memory of after ages and posterity, yea if they would but bestirre themselves herin somewhat actively, it might come to pass, that they would eradicat out of mens minds that opinion, that men in the cold regions of the world are at as great distance from learning, humanity, and all endowments of the mind, as they are distant from the sun. For as Nature hath granted to the Affricans, Egyptians, and many other nations more subtile motions of the mind, and a greater sharpness of wit, yet she hath not altogether so far cast off any nation, as to shut up from it an entry to vertue and honour.”

Hereupon, whilst he did speak meanly of him self (which is his modesty), but of me more affectionatly than truely, at last the tract of discourse drew us on so far, that when he had asked me concerning the troubled state of our countrey, and I had answered him as far as I judged convenient for that time, I began by course to ask him what was the opinion of the Frenches or other nations with whom he had conversed in France, concerning our affairs. For I did not [3] question, but that the novelty of affaires (as is usual) would give occasion and matter of discourse thereof to all. “Why (saith he) do you desire that of me? For seeing you are wel acquanted with the course of affaires, and is not ignorant what the most part of men do speak, and what they think, you may easily guess in your own conscience, what is, or at least should be the opinion of all.”

B. But the further that forrain nations are at a distance, they have the less causes of wrath, hatred, love and other perturbations, which may divert the mind from truth, and for the most part they so much the more judge of things sincerely, and freely speak out what they think. That very freedome of speaking and conferring the thoughts of the heart doth draw forth many obscure things, dicover intricacies, confirme doubts, and may stop the mouth of wicked men, and teach such as are weak.

M. Shall I be ingenuous with you?

B. Why not?

M. Although I had a great desire after so long a time to visite my native country, parents, relations, and friends, yet nothing did so much inflame my desire, as the clamour of a rude multitude. For albeit I thought my selfe well enough fortified either by my own constant practice, or the morall precepts of the most learned, I know not how I could conceale my pusillanimity. For when that horrid villany not long since here perpetrat, all with one [4] voice did abominat it. The author hereof not being known, the multitude, which is more acted by a precipitancy than ruled by deliberation, did charge the fault of some few upon all, and the common hatred of a particular crime did redound to the whole nation, so that even such as were most remote from any suspicion were inflamed with the infamy of other mens crime. When therefore this storme of calumny was calmed, I betook my self very willingly into this port, wherein notwithsanding I am afraid I may dash upon a rock.

B. Why, I pray you?

M. Because the atrociousness of that late crime doth seeme so much to inflame the minds of all already exasperat, that now no place of apology is left. For how shall I be able to sustain the impetuous assaults, not only of the weaker sort, but also of those who seeme to be more sagacious, who will exclaime against us, that we were content with the slaughter of an harmeless youth, an unheard of cruelty, unless we should shew another new example of atrocious cruelty against women, which sexe very enemies to spare when cities are taken by force? Now from what villany will any dignity or majesty deterre those who thus rage against kings? Or what place for mercy will they leave, whom neither the weakness of sexe, nor innocency of age will restrain? Equity, custome, lawes, the respect to soveraignty, reverence of lawful magistracy, [5] which hence forth they will either retain for shame, or coerce for fear, when the power of supreame authority is exposed to the ludibry of the basest of the people? The difference of equity and iniquity, of honesty and dishonesty being once taken away, almost by a publick consent there is a degeneracy into cruel barbarity. I know I shall hear these, and more atrocious than these, spoken how soon I shall returne into France again, all mens ears in the mean time being shut from admitting any apology or satisfaction.

B. But I shall easily liberat you of this fear, and our nation from that false crime. For, if they do so much detest the atrociousness of the first crime, how can they rationally reprehend severity in revenging it? Or if they take it ill that the Queen is taken order with, they must needs approve the first deed: choose you then, which of the two would you have to seeme cruel. For neither they nor you can praise or reproach both, provided you understand your selves.

M. I do indeed abhorre and detest the Kings murther, and am glad that the nation is free of that guilt, and that it is charged upon the wickedness of some few. But this last fact I can neither allow nor disallow, for it seemes to me a famous and memorable deed, that by counsel and diligence they have searched out that villany, which since the memory of man is the most hainous, and do pursue the perpetrators in a hostile manner. But in that they have taken order [6] with the chief magistrat, and put contempt upon soveraignty, which amongst all nations hath been alwayes accounted great and sacred, I know not how all the nations of Europe will relish it, especially such as live under kingly government. Surely the greatness and novelty of the fact doth put me to a demurre, albeit I am not ignorant what may be pretended on the contrary, and so much the rather, because some of the actors are of my intimate acquaintance.

B. Now I almost perceive that it doth perhaps not trouble you so much as those of forrain nations, who would be judges of the vertues of others, to whom you think satisfaction must be given. Of these I shall set down three sorts especially, who will vehemently enveigh against that deed. The first kind is most pernicious, wherein those are who have mancipated themselves to the lusts of tyrants, and think every thing just and lawfull for them to do wherein they may gratify kings, and measure every thing not as it is by it self, but by the lust of their masters. Such have so devoted themselves to the lusts of others that they have left to themselves no liberty either to speak or do. Out of this crew have proceeded those who have most cruelly murdered that innocent youth without any cause of enmity, but through hope of gain, honour, and power at Court to satisfy the lust of others. Now whilst such feign to be sorry for the Queens case, they are not grieved for her misfortunes, but [7] look for their own security , and take very ill to have the reward of their most hainous crime (which by hope they swallowed down) to be pulled out of their throat. I judge therefore that this kind of men should not be satisfied so much by reasoning, as chastised by the severity of lawes and force of armes. Others again are all for themselves; these men, though otherwise not malicious, are not grieved for the publick calamity (as they would seeme to be) but for their own domestick damages, and therefore they seeme to stand in need rather of some comfort than of the remedies of perswasive reasoning and lawes. The rest is the rude multitude, which doth admire at all novelties, reprehend many things, and think nothing is right but what they themselves do or see done. For how much any thing done doth decline from an ancient custome, so farr they think it is fallen from justice and equity. And because these be not led by malice and envy, nor yet by self-interest, the most part will admitt information, and to be weaned from their errour, so that being convinced by the strength of reason, they yeeld. Which in the matter of religion, we find by experience very often in these dayes, and have also found it in preceeding ages, there is almost no man so wilde that can not be tamed, “if he will but patiently hearken to instruction.”

M. Surely we have found oftentimes that very true.

B. When you therefore deale with this kind [8] of people, so clamorous and very importunat, ask some of them what they think concerning the punishment of Caligula, Nero or Domitian, I think there will be none of them so addicted to the name King that will not confess they were justly punished.

M. Perhaps you say right, but these very same men will forthwith cry out that they complain not of the punishment of tyrants, but are grieved at the sad calamities of lawfull kings.

B. Do you not then perceive how easily the people may be pacified?

M. Not indeed, unless you say some other thing.

B. But I shall cause you understand in few words. The people (you say) approve the murther of tyrants, but compassionat the misfortune of kings. Would they then not change their opinion, if they clearly understood what the difference is betwixt a tyrant and a king? Do you not think that this might come to pass, as in many other cases?

M. If all would confess that tyrants are justly killed, we might have a large entry made open to us for the rest, but I find some men, and these not of small authority, who, while they make kings liable to the penalties of the lawes, yet they will maintain tyrants to be sacred persons; but certainly by a preposterous judgment, if I be not mistaken, yet they are ready to maintain their government, albeit immoderat and intolerable, as if they were to fight for things both sacred and civil.

B. I have also met with several persons oftentimes who maintain the same [9] very pertinaciously; but whether that opinion be right or not, we shall further discuss it hereafter at better conveniency. In the mean time, if you please, let us conclude upon this, upon condition that, unless hereafter it be not sufficiently confirmed unto you, you may have liberty to retract the same.

M. On these terms indeed I will not refuse it.

B. Let us then conclude these two to be contraries, a king and a tyrant.

M. Be it so.

B. He therefore that shall explain the original and cause of creating kings, and what the duties of kings are towards their people, and of people towards their kings, will ne not seeme to have almost explained on the other hand what doth pertain to the nature of a tyrant.

M. I think so.

B. The representation then of both being laid out, do you not think that the people will understand also what their duty is towards both?

M. It is very like they will.

B. Now contrary wise, in things that are very unlike to one another, which yet are contained under the same genus, there may be some similitudes, which may easily induce imprudent persons into an errour.

M. Doubtless there may be such, and especially in the same kind, where that which is the worst of the two doth easily personat the best of both, and studies nothing more than to impose the same upon such as are igorant.

B. Have you not some representation of a king and of a tyrant impressed in your mind? [10] For if you have it, you will save much pains.

M. Indeed I could easily express what idea I have of both in my mind, but I fear it may be rude and without forme. Therefore I rather desire to hear what your opinion is, lest whilst you are a refuting me, our discourse become more prolixe, you being both in age and experience above me, and are well acquainted not only with the opinions of others, but also have seen the customes of many, and their cities.

B. I shall then do it, and that very willingly, yet I will not unfold my own opinion so much as that of the ancients, that thereby a greater authority may be given to my discourse, as not being such as is made up with respect to this time, but taken out of the opinions of those who, not being concerned in the present controversy, have no less eloquently than briefly given their judgment, without hatred, favour, or envy, whose case was far from these things; and their opinions I shall especially make use of, who have not frivolously trifled away their time, but by vertue and counsel have flourished both at home and abroad in well governed common wealths. But before I produce these witnesses, I would ask you some few things, that, seeing we are at accord in some things of no small importance, there may be no necessity to digress from the purpose in hand, nor to stay in explaining or confirming things that are perspicuous and well known.

M. I [11] think we should do so, and if you please, ask me.

B. Do you not think that the time hath been, when men did dwell in cottages, yea and in caves, and as strangers did wander to and fro without lawes or certain dwelling places, and did assemble together as their fond humours did lead them, or as some comodity and comon utility did allure them?

M. For sooth I beleeve that, seeing it is consonant to the course and order of nature, and is testified by all the histories of all nations, almost, for Homer doth describe the representation of such a wilde and barbarous kind of life in Siciliy, even in the time of the Trojans. “Their courts (saith he) do neither abound with counciles nor judges, they dwell only in darksome caves, and every one of them in high mountains ruleth his own house, wife and children, nor is any of them at leisure to communicat his domestick affaires to any other.” About the same time also Italy is said to be no better civilized, as we may easily conjecture from the most fertile regions almost of the whole world, how great the solitude and wastness there was in places on this side of Italy.

B. But whether do you think the vagrant and solitary life, or the associations of men civilly incorporat, most agreable to nature?

M. The last, without all peradventure, which “utility the mother almost of justice and equity” did first convocat, and commanded “to give signes or warnings by sound of trumpet [12] and to defend themselves within walls, and to shut the gates with one key.”

B. But do you think that utility was the first and main cause of the association of men?

M. Why not, seeing I have heard from the learned that men are born for men?

B. Utility indeed to some seems to be very efficacious, both in begetting and conserving the publick society of mankind; but if I mistake not, there is a far more venerable or ancient cause of mens associating, and a more antecedaneous and sacred bond of their civil community. Otherwise, if every one would have a regard to his own private advantage, then surely that very utility would rather dissolve than unite humane society together.

M. Perhaps that may be true, therefore I desire to know what other cause you will assigne.

B. A certain instinct of nature, not only in man, but also in the more tamed sort of beasts, that, although these allurements of utility be not in them, yet do they of their own accord flock together with other beasts of their own kind. But of these others we have no ground of debate. Surely we see this instinct by nature so deeply rooted in Man, that if any one had the affluence of all things which contribute either for maintaining health or pleasure and delight of the mind, yet he will think his life unpleasant without humane converse. Yea, they who, out of a desire of knowledge an an endeavour of investigating the truth, have [13] with drawn themselves from the multitude and retired to secret corners, could not long endure a perpetual vexation of the mind, nor, if at any time they should remit the same, could they live in solitude, but very willingly did bring forth to light their very secret studies, and as they had laboured for the publick good, they did communicat to all the fruit of their labour. But if there be any man who doth wholly take delight in solitude, and flee from converse with men, and shun it, I judge it doth rather proceed from a distemper of the mind, than from any instinct of nature, such as we have heard of Timon the Athenian and Bellerophon the Corinthian, who (as the Poet saith) “was a wandering wretch on the Elean coast, eating his own heart, and fleeing the very footsteps of men.”

M.I do not in this much dissent from you, but there is one word naturehere set down for you, which I do often use rather out of custom, than that I understand it, and is by others so variously taken, and accommodat to so many things, that for the most part I am at a stand to what I may mainly apply it.

B. Forsooth at present I would have no other thing to be understood thereby than that light infused by God into our minds, for when God formed that “createure more sacred, and capable of a celestial mind,” and which might have dominion over the other creatures, He gave not only eyes to his body, whereby he might evite things [14] contrary to his condition, and follow after such as might be usefull, but also He produced in his mind a certain light, whereby he might discerne things filthy from honest. This light some call nature, others the law of nature; for my own part, truly I think it is of a heavenly stamp, and I am fully perswaded that “nature doth never say one thing, and wisdom another.” Moreover, God hath given us an abridgement of that Law, which might contain the whole in few words, viz., that “we should love Him with all our soul, and our neighbours as our selves.” All the books of Holy Scripture which treat of ordering our conversation do contain nothing else but an explication of this law.

M. You think then that no orator or lawyer, who might congregat dispersed men, hath been the author of humane society, but God only?

B. It is so indeed, and with Cicero, I think “there is nothing done on earth more acceptable to the great God Who rules the world than the associations of men legally united, which are called civil incorporations,” whose several parts must be as compactly joyned together as the several members of our body, and every one must have their proper function, to the end there may be a mutual cooperation for the good of the whole, and a mutual propelling of injuries, and a foreseeing of advantages, and these to be communicat for engaging the benevolence of all amongst themselves.

M. You do not then make utility but that [15] divine law rooted in us from the beginning to be the cause (indeed the far more worthy and divine of the two) of mens incorporating in political societies.

B. I mean not indeed that to the mother of equity and justice, as some would have it, but rather the handmaid, and to be one of the guards in cities well constitute.

M. Herein I also agree with you.

B. Now as in our bodies, consisting of contrary elements, there are diseases, that is, perturbations, and some intestine tumults, even so there must of necessity in these greater bodies, that is in cities, which also consist of various (yea and for the most part contrary) humours, or sorts of men, and these of different ranks, conditions and natures, and which is more, of such as ”can not remain one hour approving the same things.” And surely such must needs soon dissolve and come to nought, if one be not adhibited, who as a physician may quiet such disturbances, and by a moderat and wholesome temperament confirme the infirme parts and compensce redundant humors, that the weaker may not languish for want of nutrition, nor the stronger become luxuriant too much.

M. Truely, it must needs be so.

B. How then shall we call him who performeth these things in a civil body?

M. I am not very anxious about his name, for by what name soever he be called, I think he must be a very excellent and divine person, [16] wherein the wisdom of our ancestors seemeth to have much foreseen, who have adorned the thing in it self most illustrious with an illustrious name. I suppose you mean King, of which word thee is such an emphasis, that it holds forth before us clearly a funciton in it self very great and excellent.

B. You are very right, for we designe God by that name. For we have no other more glorious name, whereby we may declare the excellency of His glorious nature, nor more suteable, whereby to signify his paternal care and providence towards us. What other names shall I collect, which we translate the function of a king, such as ”Father Aeneas, ”Agamemenon, Pastor of the People,” also a leader, prince, governour? By all which names such a signification is implyed, as we may shew that kings are not ordained for themselves, but for the people. Now as for the name we agree well enough. If you please, set us conferre concerning the function, insisting in the same footsteps we began upon.

M. Which, I pray?

B. Do you remember what hath been lately spoken, that an incorporation seemeth to be very like our body, civil commotions like to diseases, and a king to a physician? If therefore we shall understand what the duty of a physician is, I am of the opinion we shall not much mistake the duty of a king.

M. It may be so, for the rest you have reckoned are very like, and seem to me very near in kin.

B. Do [17] not expect that I will here describe every petty thing, for the time will not permit it, neither doth the matter in hand call for it; but if briefly these agree together, you shall easily comprehend the rest.

M. Go on, then, as you are doing.

B. The scope seemeth to be the same to us both.

M. Which?

B. The health of the body, for curing of which they are adhibited.

M. I understand you, for the one ought to keep safe the humane body in its state, and the other the civil body in its state, as far as the nature of each can bear, and to reduce into perfect health the body diseased.

B. You understand very wel, for there is a twofold duty incumbent on both. The one is to preserve health, the other is to restore it, if it become weak by sickness.

M. I assent to you.

B. For the diseases of both are alike.

M. It seemeth so.

B. For the redundance of things hurtfull, and want or scarcity of things necessary are alike noxious to both, and both the one and other body is cured almost in the same manner, namely either by nourishing that which is extenuat and tenderly cherishing it, or by asswaging that which is full and redundant by casting out superfluities and exercising the body with moderat labours.

M. It is so, but here seems to be the difference, that the humours in the one and manners in the other are to be reduced into a right temperature.

B. You understand it wel, for the body politick as wel as the natural have their own proper [18] temperament, ;which I think very rightly we may call justice. For it is that which doth regard every member, and cureth it so as to be kept in its function. This sometimes is done by letting of blood, sometimes by the expelling of hurtfull things, as by egestion, and sometimes exciting cast-down and timorous minds and comforting the weak, and so reduceth the whole body into that temperament I spoke of; and being reduced, exerciseth it with convenient exercises, and by a certain prescribed temperature of labour and rest, doth preserve the restored health as much as can be.

M. All the rest I easily assent to, except that you place the temperament of the body politick in justice, seeing temperance even by its very name and profession doth justly seem to claime these parts.

B. I think it is no great matter on which of them you conferre this honour. For seeing all vertues, whereof the strength is best perceived in action, are placed in a certain mediocrity and equability, so are they in some measure connected amongs themselves and cohere, so as it seems to be but one office in all, that is, the moderation of lusts. Now in whatsoever kind this moderation is, it is no great matter how it be denominat, albeit that moderation which is placed in publick matters and mens mutual commerces doth seem most fitly to be understood by the name of justice.

M. Herein I very willingly assent to you.

B. In the creation of a king, I think the [19] ancients have followed this way, that if any among the citizens were of any singular excellency, and seemed to exceed all others in equity and prudence, as is reported to be done in bee-hives, they willingly conferred the government or kingdom on him.

M. It is credible to have been so.

B. But what if none such as we have spoken of should be found in the city?

M. By that law of nature, whereof we formerly made mention, equals neither can, nor ought to usurpe domination; for by nature I think it just that amongst these that are equal in all other things, their course of ruling and obeying should be alike.

B. What if a people, wearied with yearly ambition, be willing to elect some certain person not altogether endowed with all royal vertues, but either famous by his noble descent or warlike valour? Will you not think that he is a lawfull king?

M. Most lawfull, for the people have power to conferre the government on whom they please.

B. What if we shall admitt some acute man, yet not endowed with notable skill, for curing diseases? Shall we presently account him a physician, as soon as he is chosen by all?

M. Not at all, for by learning and the experience of many arts, and not by suffrages is a man made a physician.

B. What maketh artists in other arts?

M. I think there is one reason of all.

B. Do you think there is any art of reigning or not?

M. Why not?

B. Can you give me [20] a reason why you think so?

M. I think I can, namely, that same which is usually given in other arts.

B. What is that?

M. Because the beginnings of all arts proceed from experience. For whilst many did rashly and without reason undertake to treat of many things, and others again through exercitation and consuetude did the same more sagaciously, noticing the events on both hands, and perpending the causes thereof, some acute men have digested a certain order of precepts, and called that description an art.

B. Then by the like animadversion may not some Art of Reigning be described, as well as the Art of Physick?

M. I think there may.

B. Of what precepts shall it consist?

M. I do not know at present.

B. What if we shall find it out by comparing it with other arts?

M. What way?

B. This way: there be some precepts of grammar, of physick, and husbandry.

M. I understand.

B. Shall we not call these precepts of grammarians and physicians arts and lawes also, and so of others?

M. I seems indeed so.

B. Do not the civill lawes seem to be certain precepts of royal art?

M. They seem so.

B. He must therefore be acquaint therewith, who would be accounted a king.

M. It seemes so.

B. What if he have no skill therein? Albeit the people shall command him to reigne, think you that he should be called a king?

M. You cause me here hesitate. For if I [21] would consent with the former discourse, the suffrages of the people can no more make him a king than any other artist.

B. What think you shall then be done? For unless we have a king chosen by suffrages, I am afraid we shall have no lawfull king at all.

M. And I fear also the same.

B. Will you then be content that we more accuratly examine what we have last set down in comparing arts one with another?

M. Be it so, if it so please you.

B. Have we not called the precepts of artists in their several arts lawes?

M. We have done so.

B. But I fear we have not done it circumspectly enough.

M. Why?

B. Because he would seem absurd who had skill in any art, and yet not to be an artist.

M. It were so.

B. But he that doth performe what belongs to an art, we will account him an artist, whether he do it naturally, or by some perpetual and constant tenour and faculty.

M. I think so.

B. We shall then call him an artist who knowes wel this rational and prudent way of doing any thing wel, providing he hath acquired that faculty by constant practice.

M. Much better than him who hath the bare precepts without use and exercitation.

B. Shall we not then account these precepts to be art?

M. Not at all, but rather a certain similitude thereof, or rather a shaddow of art.

B. What is then that governing faculty of cities which we shall call civil art or science?

M. It seemes you would call it prudence; [22] out of which, as from a fountain or spring, all lawes, provided they be usefull for the preservation of humane society, must proceed and be derived.

B. You have hit the nail on the head. If this then were compleat and perfect in any person, we might say he were a king by nature, and not by suffrages, and might resigne over to him a free power over all things; but if we find not such a man, we shall also call him a king, who doth come nearest to that eminent excellency of nature, embracing in him a certain similitude of a true king.

M. Let us call him so, if you please.

B. And because we fear he be not firme enough against inordinat affections, which may, and for the most part use to decline men from truth, we shall adjoyn to him the law, as if it were a colleague, or rather a bridler of his lusts.

M. You do not then think that a king should have an arbitrary power over all things.

B. Not at all, for I remember that he is not only a king, but also a man, erring in many things by ignorance, often failing willingly, doing many things by constraint, yea a creature easily changeable at the blast of every favour or frown, which natural vice a magistrat useth also to increase, so that here I chiefly find that of the comedy made true, ”all by licence become worse.” Wherefore the most prudent have thought it expedient to adjoyne to him a law, which may either shew him the way, if he be ignorant, or bring him back again [23] into the way, if he wander out of it. By these, I suppose, you understand, as in a representation, what I judge to be the duty of a true king.

M. Of the cause of creating kings, of their name and duty you have fully satisfied me. Yet I shall not repine, if you please to add ought thereto. Albei4t my mind doth hasten to hear what yet seemes to remain, yet there is one thing which in all your discourse did not a little offend me, which I think should not be past over in silence, viz. that you seem somewhat injurious to kings, and this very thing I did suspect in you frequently before, whilst I often heard you profusely commend the ancient common-wealths and the city of Venice.

B. You did not rightly herein judge of me. For I do not so much look to the different forme of civil government (such as was amongst the Romans, Massilians, Venetians and others, amongst whom the authority of lawes were more powerfull than that of men) as to the equity of the forme of government; nor do I think it matters much whether King, Duke, Emperour, or Consul be the name of him who is the chiefest in authority, provided this be granted, that he is placed in the magistracy for the maintenance of equity, for if the government be lawfull, we must not contend for the name thereof. For he whom we call the Duke of Venice is nothing else but a lawfull king, and the first Consuls did not only retain the honours of [24] kings, but also their empire and authority; this only was the difference, that not one, but two of them did reigne (which also you know was usual in all the Lacedemonian kings), who were created or chosen, not constantly to continue in the government, but for one year. We must therefore alwayes stand to what we spoke at first, that kings at first were institute for maintaining equity. If they could have holden that soveraignty in the case they had received it, they might have holden and kept it perpetually, but this is free and loosed by lawes. But (as it is with humane things) the state of affaires tending to worse, the soveraigne authority which was ordained for publick utility degenerated into a proud domination. For when the lust of kings stood in stead of lawes, and men being vested with an infinite and immoderate power did not contain themselves within bounds, but connived at many things out of favour, hatred, or self-interest, the insolency of kings made lawes to be desired. For this cause therefore lawes were made by the people, and kings constrained to make use, not of their own licentious wills in judgement, but of that right or priviledge which the people had conferred upon them. For they were taught by many experiences that it was better that their liberty should be concredited to lawes than to kings, whereas the one might decline many wayes from the truth, but the other, being deafe both to intreaties and threats, [25] might still keep one and the same tenor. This one way of government is to kings prescribed, otherwise free, that they should conforme their actions and speech to the prescripts of laws, and by sanctions thereof divide rewards and punishments, the greatest bonds of holding fast together humane society. And lastly, even as saith that famous legistlator, “a king should be a speaking law, and the law a dumb king.”

M. At first you so highly praised kings that you made their majesty almost glorious and sacred, but now, as if you had repented in so doing, I do not know within what strait bonds you shut them up, and being thrust into the prison (I may say) of lawes, you do scarce give them leave to speak. And as for my part, you have disappoynted me of my expectation very farre. For I expected that (according to the most famous historians) you should have restored the thing which is the most glorious both with God and Man into its own splendor, either of your own accord, or at my desire, in the series of your discourse, which being spoiled of all ornaments, you have brought it into subjection; and that authority, which through all the world is the chiefest, you have hedged-in round about and made it almost so contemptible as not to be desired by any man in his right witts. For what man in his right witts would not rather live as a private man with a mean fortune, than, being still in action about other mens affaires, [26] to be in perpetual trouble, and, neglecting his own affaires, to order the whole course of his life according to other mens rule? But if that be the tearmes of government every where proposed, I fear there will be a greater scarcity of kings found than was of bishops in the first infancy of our religion. Nor do I much wonder if kings be regarded according to this plate-forme, being but men taken from feeding cattell and from the plough, who took upon them that glorious dignity.

B. Consider, I pray you, in how great an errour you are, who does think that kings were created by people and nations, not for justice, but for pleasure, and does think there can be no honour where wealth and pleasures abound not; wherein consider how much you diminish their grandour. Now that you may the more easily understand it, compare any one king of those you have seen apparelled like a childs puppet, brought forth with a great deale of pride and a great many attendants, meerly for vain ostentation, the representation whereof you miss in that king whom we describe. Compare, I say, some one of those who were famous of old, whose memory doth even yet live, flourisheth and is renowned to all posterity. Indeed they were such as I have now been describing. Have you hever heard what an old woman, petitioning Philip, King of Macedon, to hear her cause, answered him, he having said to her, he had no leisure; to which she [27] replyed, ”then cease (said she) to be king?” Have you never heard, I say, that a king victorious in so many batells, and conqueror of so many nations, admonished to do his duty by a poor old wife, obeyed, and so acknowledged that it was the duty of kings so to do? Compare then this Philip not only with the greatest kings that are now in Europe, but also with all that can be remembred of old, you shall surely find none of them comparable to those either for prudence, fortitude, or activity; few equal to them for largeness of dominions. If I should enumerat Agesilaus, Leonidas and the rest of the Lacedemonian kings (o how great men were they!), I shal seem to utter but obsolete examples. Yet one saying of a Lacedemonian maid I cannot pass over with silence, her name was Gorgo, the daughter of Cleomedes. She, seeing a servant pulling off the stockings of an Asian ghuest, and running to her father, cryed out ”father, the ghuest hath no hands!”, from which speech of that maid you may easily judge of the Lacedemonian discipline, and domestick custome of their kings. Now those who proceded out of this rustick but courageous way of life did very great things, but those who were bred in the Asiatick way lost by their luxury and sloth the great dominions given them by their ancestors. And, that I may lay aside the ancients, such a one was Pelagius not long ago among the people of Galicia, who was [28] the first that weakned the Saracen forces in Spain, “yet him and all his the grave did inclose.” Yet of him the Spanish kings are not ashamed, accounting it their greatest glory to be descended of him.

But seeing this place doth call for a more large discourse, let us returne from whence we have digressed. For I desire to shew you with the first what I promised, namely that this forme of government hath not been contrived by me, but seemes to have been the same to the most famous men in all ages, and I shall briefly shew you the spring from whence I have drawn these things. The books of Marcus Tullus Cicero which are intituled Of Offices are by common consent of all accounted most praise worthy; in the second Book thereof these words are set down verbatim. ”It seems as Herodotus saith that of old well bred kings were created, not amongst the Medes only, but also amongst our ancestors for executing of justice, for whilst at first the people were oppressed by those that greatest wealth, they betook themselves to some one who was eminent for vertue, who, whilst he kept off the weakest from injuries, establishing equity, he hemmed in the highest with the lowest by equall lawes to both. And the reason of making lawes was the same as of the creation of kings, for it is requisite that justice be alwayes equall, for otherwise it were not justice. If this they did obtain from one good and just man, they were therewith [29] wel pleased; when that did not occurre, lawes were made, which by one and the same voice might speak to all alike. This then indeed is evident, that those were usually chosen to governe, of whose justice the people had a great opinion. Now this was added, that these rulers or kings might be accounted prudent, there was nothing that men thought they could not obtain from such rulers.” I think you see from these words what Cicero judgeth to be the reason of requiring both kings and lawes. I might here commend Zenophon, a witness requiring the same, no less famous in war-like affairs than in the study of philosophy, but that I know you are so well acquaint with his writings as that you have all his sentences marked. I pass at present Plato and Aristotle, albeit I am not ignorant how much you have them in estimation. For I had rather adduce for confirmation men famous in a midle degree of affaires, than out of Schools. Far less do I think fit to produce a Stoick king, such as by Seneca in Thyestes is described, not so much because that idea of a king is not perfect, as because that examples of a good prince may be rather impressed in the mind, than at any time hoped for. But lest in those I have produced there might be any ground of calumny, I have not set before you kings out of the Scythian solitude, who did either ungird their own horses, or did other servile work, which might be [30] very far from our manner of living, but even out of Greece and such, who in these very times, wherein the Grecians did most flourish in all liberall sciences, did rule the greatest nations or wel governed cities; and did so rule, that whilst they were alive were in very great esteeme amongst their people, and being dead left to posterity a famous memory of them selves.

M. If now you ask me what my judgment is, I scarce dare confess to you either mine inconstancy or timidity, or by what other name it shall please you call that vice. For as often as I read these things you have now recited in the most famous historians, or hear the same commended by very wise men whose authority I dare not decline, and that they are approved by all good and honest men to be not onely true, equitable and sincere, but also seeme strong and splendid; again, as oft as I cast mine eyes on the neatness and elegancy of our times, that antiquity seemeth to have been venerable and sober, but rude and not sufficiently polished. But of these things we may perhaps speak of hereafter at more leisure. Now, if it please you, go on to prosecute what you have begun.

B. May it please you then that we recollect briefly what hath been said? So shall we understand best what is past, and if ought be rashly granted, we shall very soon retract it.

M. Yes indeed.

B. First of all then, we agree that men by nature are made to live in society [31] together, and for a communion of life.

M. That is agreed upon.

B. That a king also chosen to maintain that society is a man eminent in vertue.

M. It is so.

B. And as the discords amongst themselves brought in the necessity of creating a king, so the injuries of kings done against their subjects were the cause of desiring lawes.

M. I acknowledge that.

B. We held lawes to be a proofe of the art of government, even as the preceps of physick are of the medicinal art.

M. It is so.

B. But it seems to be more safe (because in neither of the two have we set down any singular and exact skill of their severall arts) that both do, as speedily as may be, heal by these prescripts of art.

M. It is indeed safest.

B. Now the precepts of the medicinal arts are not of one kind.

M. How?

B. For some of them are for preservation of health, others for restauration thereof.

M. Very right.

B. What say you of the governing art?

M. I think there be as many kinds.

B. Next then, it seems that we consider it. Do you think that physicians can so exactly have skill of all diseases, and of their remedies, as nothing more can be required for their cure?

M. Not at all, for many new kinds of diseases arise almost in every age, and new remedies for each of them are by mens industry found out, or brought from far countries.

B. What think you of the lawes of [32] commonwealths?

M. Surely their case seemes to be the same.

B. Therefore neither physicians nor kings can evite or cure all diseases of commonwealths by the precepts of their arts which are delivered to them in writ.

M. I think indeed they cannot.

B. What if we shall further try of what things lawes may be established in commonwealths, and what cannot be comprehended within lawes?

M. That will be worth our pains.

B. There seems to be very many and weighty things which cannot be contained within lawes. First, all such things as fall into the deliberation of the time to come.

M. All indeed.

B. Next, many things already past, such are these wherein truth is sought by conjecturs, confirmed by witnesses, or extorted by torments.

M. Yes indeed.

B. In unfolding then these questions what shal the king do?

M. I see here there is no need of a long discourse, seeing kings do not so arrogate the supream power in those things which are institute with respect to the time to come, that of their own accord they call to councill some of the most prudent.

B. What say you of those things which by conjectures are found out, and made out by witnesses, such as are the crimes of murther, adultery and witchcraft?

M. These are examined by the skill of lawyers, discovered by diligence, and these I find to be for the most part left to the judgment of judges.

B. And perhaps very [33] right; for if a king would needs be at the private causes of each subject, when shal he have time to think upon peace and war, and those affaires which maintain and preserve the safety of the commonwealth? And lastly when shall he get leave to rest?

M. Neither would I have the cognition of every thing to be brought unto a king, neither can one man be sufficient for all the causes of all men, if they be brought unto him; that counsel no less wise than necessary doth please me exceedingly well, which the father in law of Moses have him in dividing amongst many the burden of hearing causes, whereof I shall not speak much, seeing the history is known to all.

B. But I think these judges must judge according to law.

M. They must indeed do so. But, as I conceive, there be but few things which by lawes may be provided against, in respect of those which cannot be provided against.

B. There is another thing of no less difficulty, because all these things which call for lawes cannot be comprehended by certain prescriptions.

M. How so?

B. Lawyers, who attribute very much to their own art, and who would be accounted the priests of justice, do confess that there is so great a multitude of affairs that it may seeme almost infinit, and say that daily arise new crimes in cities, at were severall kinds of ulcers. What shall a lawgiver do herin, who doth accomodat lawes both to things [34] present and pretent?

M. Not much, unless he be some divine-like person.

B. An other difficulty doth also occurre, and that not a small one, that in so great an inconstancy of humane frailty no art can almost prescribe any things altogether stable and firme.

M. There is nothing more true than that.

B. It seemeth then most safe to trust a skilfull physician in the health of the patient, and also the king in the state of the common wealth. For a physician without the rule of art will often times cure a weak patient either consenting thereto, or against his will; and a king doth either perswade a new law yet usefull to his subjects, or else may impose it against their will.

M. I do not see what may hinder him therein.

B. Now seeing both the one and the other do these things, do you think that, besides the law, either of them makes his own law?

M. It seemes that both doth it by art. For we have before concluded not that to be an art which consists of preceps, but vertue contained in the mind, which the artist usually makes use of in handling the matter which is subject to arts. Now I am glad (seeing you speak ingenuously) that you, being constrained, as it were, by an interdiction of the very truth, do so far restore the king from whence he was by force dejected.

B. Stay, you have not yet heard all. There is an other inconvenient in the authority of lawes. For the law being as it were a pertinacious, [35] and a certain rude exactor of duty, thinks nothing right but what it self doth command. But with a king there is an excuse of infirmity and temerity, and place of pardon left for one found in an errour. The law is deaf, cruel and inexorable. A young man pleads the frailty of his years, a woman the infirmity of her sexe, another his poverty, drunkenness, affection. What saith the law to these excuses? ”Go, officer or serjeant, conveene a band of men, hoodwink him, scourge him, hang him on a tree.” Now you know how dangerous a thing it is, in so great a humane frailty, to have the hope of safety placed in innocency alone.

M. In very truth you tell me a thing full of hazard.

B. Surely as oft as these things come into mind, I perceive some not a little troubled.

M. You speak true.

B. When therefore I ponder with my self what is before past as granted, I am afraid lest the comparison of physician and king in this case seem not pertinently enough introduced.

M. In what case?

B. When we have liberat both of the servitude of preceps, and given them almost a free liberty of curing.

M. What doth herin especially offend you?

B. When you hear it, you will then judge. Two causes are by us set down, why it is not expedient for a people that kings be loosed from the bonds of lawes, namely love and hatred, which drive the minds of men to and from in [36] judging. But in a physician it is not to be feared lest he faile through love, seeing he expecteth a reward from the patient being restored to health. But if a patient understand that his physician is solicited by intreaties, promises and money against his life, he may call another physician, or if he can find none other, I think it is more safe to seek some remedy from books, how deaf soever, than from a corrupt physician. Now because we have complained of the cruelty of lawes, look if we understand one another sufficiently.

M. How so?

B. We judged an excellent king, such as we may more see in mind than with bodily eyes, not to be bound by any lawes.

M. By none.

B. Wherefore?

M. I think because, according to Paul, he should be a law to himself and to others, that he may express in life what is by law enjoyned.

B. You judge rightly, and that you may perhaps the more admire, several ages before Paul, Aristotle did see the same, following nature as a leader. Which therefore I say, that you may see the more clearly what hath been proved before, to wit, that the voice of God and nature is the same. But that we may prosecute our purpose. What shall we say they had a respect unto, who first made lawes?

M. Equity, I think, as hath been said before.

B. I do not now demand that, what end they had before them, but rather what patterne they proposed to themselves?

[37]

M. Albeit perhaps I understand that, yet I would have you to explain it, that you may confirme my judgement, if I rightly take it up; if not, you may amend my error.

B. You know, I think, what the dominion is of the mind over the body.

M. I seem to know it.

B. You know this also, what ever we do not rashly, that there is a certain idea thereof first in our minds, and that it is a great deale more perfect than the works to be done, which according to that patterne the chiefest artists do frame and, as it were, express.

M. That indeed I find by experience both in speaking and writing, and perceive no less words in my mind, than my minds in things wanting. For neither can our mind, shut up in this dark and troubled prison of the body, perceive the subtilty of all things, nor can we so endure in our mind the representations of things however foreseen in discourse with others, so as they are not much inferiour to these which our intellect hath formed to it self.

B. What shall we say then which they set before them, who made lawes?

M. I seem almost to understand what you would be at. Namely, that they in councill had an idea of that perfect king, and that they did express a certain image, not of the body, but of the mind, according to that aforesaid idea as near as they could. And would have that to be in stead of lawes which one is to think might be good and equitable.

[38]

B. You rightly understand it. For that is the very thing I would say. But now I would have you to consider what manner of king that is which we have constitute at first, was he not one firme and steadfast against hatred, wrath, envy, and other perturbations of the mind?

M. We did indeed imagine him to be such a one, or believed him to have been such to those ancients.

B. But do lawes seeme to have been made according to the idea of him?

M. Nothing more likely.

B. A good king then is no less severe and inexorable than a good law.

M. He is even as severe; but since I can change neither, or ought to desire it, yet I would slaken both somewhat if I can.

B. But God desires not that mercy be shewed even to the poor in judgment, but commandeth us to respect that one thing which is just and equal, and to pronounce sentence accordingly.

M. I do acknowledge that, and by truth am overcome. Seing therefore it is not lawfull to loose kings from the bonds of lawes, who shal then be the lawgiver? Whom shall we give him as a pedagogue?

B. Whom do you think fittest to performe this duty?

M. If you ask at me, I think the king himself. For in all other arts almost, we see their precepts are given by the artists; whereof they make use, as if it were of comments for confirming their memory, and putting others in mind of their duty.

B. On the contrary, [39] I see no difference; let us grant that a king is at liberty and solved from the lawes, shall wee grant him the power to comand lawes? For no man will willingly lay bonds and fetters upon himself. And I know not whether it be better to leave a man without bonds, or to fetter him with slight bonds, because he may rid himself thereof when he pleases.

M. But when you concredit the helme of government rather to lawes than to kings, beware, I pray you, lest you make him a tyrant, whom by name you make a king, who “with authority doth oppress and with fetters and imprisonment doth bind,” and so let him be sent back to the plough again, or to his former condition yet free of fetters.

B. Brave words: I impose no lord over him, but I would have it in the peoples power, who gave him the authority over themselves, to prescribe to him a modell of his government, and that the king may make use of that justice which the people gave him over themselves. This I crave. I would not have these lawes to be by force imposed, as you interpret it, but I think that by a common council with the king, that should be generally established, which may generally tend to the good of all.

M. You will then grant this liberty to the people?

B. Even to the people, indeed, unless perhaps you be of another mind.

M. Nothing seemes less equitable.

B. Why so?

M. You know [40] that saying, “a beast with many heads.” You know, I suppose, how great the temerity and inconstancy of a people is.

B. I did never imagine that that matter ought to be granted to the judgment of the whole people in general, but that, near to our custome, a select number out of all estates may conveen with the king in council. And then how soon an overture by them is made, that it be deferred to the peoples judgment.

M. I understand well enough your advice. But this so carefull a caution you seem to help your self nothing. You will not have a king loosed from lawes. Why? Because, I think, within man two most cruell monsters, lust and wrath, are in a continuall conflict with reason. Lawes have been greatly desired, which might repress their boldness and reduce them, too much insulting, to regard a just government. What will these counsellours given by the people do? Are they not troubled by that same intestine conflict? Do they not conflict with the same evils as well as the king? The more, then, you adjoyn to the king as assessors, there will be the greater number of fools, from which you see what is to be expected.

B. But I expect a far other thing than you suppose. Now I shall tell you why I do expect it. First, it is not altogether true what you suppoze, viz., that the assembling together of a multitude is to no purpose, of which number there will perhaps be none of [41] a profound wit. For not only do many see more and understand more than one of them apart, but also more than one, albeit he exceed their wit and prudence. For a multitude for the most part doth better judge of all things than single persons apart. For everey one apart have some particular vertues, which being united together make up one excellent vertue, which may be evidently seen in physicians pharmacies, and especially in that antidot which they call Mithredat. For therein are many things of themselves hurtfull apart, which, being compounded and mingled together, make a wholesome remedy against poyson. In like manner in some men slowness and lingering doth hurt, in others a precipitant temerity, both which, being mingled together in a multitude, make a certain temperament and mediocrity, which require to be in every kind of vertue.

M. Be it so, seeing you will have it so, let the people make lawes and execute them, and let kings be, as it were, keepers of registers. But when lawes seem to clash, or are not exact and perspicuous enough in sanctions, will you allow the king no interest or medling here? Especially since you will have him to judge all things by written lawes, there must needs ensue many absurdities. And, that I make use of a very common example of that law commended in the Schooles, If a stranger scale scale a wall, let him die, what can [42] be more absurd than this, that the author of a publick safety (who have thrust down the enemies pressing hard to be up) should be drawn to punishment, as if he had in hostility attempted to scale the walls?

B. That is nothing.

M. You approve then that old saying, ”the highest justice is the highest injury.”

B. I do indeed.

M. If any thing of this kind come into debate, there is need of a meek interpreter, who may not suffer the lawes which are made for the good of all to be calamitous to good men, and deprehended in no crime.

B. You are very right, neither is there any thing else by me sought in this dispute (if you have sufficiently noticed it) than that Ciceronian law might be venerable and inviolable, salus populi suprema lex esto. If then any such thing shall come into debate, so that it be clear what is good and just, the king’s duty will be to advert that the law may reach that rule I spoke of. But you in behalf of kings seems to require more than the most imperious of them assume. For you know that this kind of questions is usually deferred to judges, when law seemeth to require one thing and the lawgiver another, even as these lawes which arise from an ambiguous right or from the discord of lawes amongst themselves. Therefore in such cases most grievous contentions of advocats arise in judicatories, [43] and orators preceps are diligently produced.

M. I know that to be done which you say. But in this case no less wrong seemes to be done to lawes than to kings. For I think it better to end that debate presently from the saying of one good man, than to grant the power of darkning rather than interpreting lawes to subtile men, and sometimes to crafty knaves. For whilst not only contention ariseth between advocat for the causes of parties contending, but also for glory, contests are nourished in the mean time. Right or wrong, equity or inequity is called in question, and what we deny to a king we grant to men of inferiour rank, who study more to debate than to find out the truth.

B. You seeme to me forgetfull of what we lately agreed upon.

M. What is that?

B. That all things are to be so freely granted to an excellent king, as we have described him, that there might be no need of any lawes. But whilst this honour is conferred to one of the people who is not much more excellent than others, or even inferiour to some, that free and loose licence from lawes is dangerous.

M. But what ill doth that to the interpretation of law?

B. Very much. Perhaps you do not consider that in other words we restore to him that infinit and immoderat power which formerly we denyed to a king, namely that according to his own hearts lust he may turn all things upside down.

[44]

M. If I do that, then certainly I do it imprudently.

B. I shall tell you more plainly, that you may understand it. when you grant the interpretation of lawes to a king, you grant him such a licence, as the law doeth not tell what the lawgiver meaneth, or what is good and equall for all in generall, but what may make for the interpreters benefit, so that he may bend it to all actions for his own benefit or advantage, as the Lesbian rule. Appius Claudius in his decemviratus made a very just law, that in a liberall cause or plea, sureties should be granted for liberty. What more clearly could have been spoken? But by interpreting, the same author made his own law useless. You see, I suppose, how much liberty you give a prince by one cast, namely that what he pleaseth, the law doth say; what pleaseth him not, it doth not say. If we shall once admit this, it will be to no good purpose to make good lawes for teaching a good prince his duty, and hemme in an ill king. Yea, let me tell you more plainly, it would be better to have no lawes at all than that freedom to steal should be tolerat, and also honoured under pretext of law.

M. Do you think that any king will be so impudent that he will not at all have any regard of the fame and opinion that all men have of him? Or that he will be so forgetfull of subjects that he will degenerat into their privaty, whom [45] he hath restrained by ignominy, imprisonment, confiscation of goods, and, in a word, with very grievous punishments?

B. Let us not believe that these things will be, if they had not been done long ago, and that to the exceeding great hurt of the whole world.

M. Where do you tell these things were done?

B. Do you ask where? As if all the nations in Europe did not only see, but feele also how much mischief hath the immoderat power and unbridled tyranny of the Pope of Rome brought upon humane affairs. Even that power which from small beginning and seemingly honest he had got, every man doth know that no less can be feared by unwary persons. At first, lawes were proposed to us, not only drawn out of the innermost secrets of nature, but given by God Himself, explaind by the Prophets from the Holy Spirit, at last confirmed by the Son of God, and by the same God confirmed, committed to the writings of those praise worthy men, expressed in their life, and sealed with their blood. Neither is there in the whole law any other place more carefully, commendably, or more clearly delivered than that of the office of bishops. Now, seeing it is lawfull to no man to add any thing to these lawes, to abrogat or derogat ought therefrom, or to change any thing therein, there did remain but one interpretation, and whilst the Pope did arrogat it, he not only [46] did oppress the rest of the Churches, but claimed a tyranny the most cruell of all that ever were, daring to command not only men but angels also, plainly reducing Christ into order. If this be not to reduce him into order, that what thou wilt have done in heaven, in earth and amongst the damned in Hell be ratifid, what Christ hath commanded, let it be ratified, if thou wilt, for if the law seeme to make but little for your behoofe, interpreting it thus you may back-bend it, so that not only by your mouth, but also according to the judgment of your mind Christ is constrained to speak. Christ therefore speaking by the mouth of the Pope, Pipin is set in Childerick’s place of government, Ferdinandus of Arragon substitute to John King of Navarre; the son arose in armes against his father, and subjects against their king. Christ is full of poison, then he is forced by witches so that he killeth Henry of Luxemburg by poison.

M. I have heard these things often before, but I desire to hear more plainly somewhat of that interpretation of lawes.

B. I shall offer you one example, from which you may easily understand how much this whole kind is able to do. The law is A bishop must be the husband of one wife, than which law what is more clear, and what may be said more plain? “One wife” (saith the law), “one church” (saith the Pope), such is his interpretation. As if that law were made [47] not to repress the lust of bishops, but their avarice. Now this explanation, albeit it saith nothing to the purpose, yet doth contain a judgement honest and pious, if he had not vitiated that law again by another interpretation. What doeth therefore the Pope devise for excuse? “It varieth (saith he) in regard of persons, cases, places and times. Some are of that eminent disposition that no number of churches can satisfy their pride. Some churches again are so poor that they cannot maintain him who was lately a begging monk, if he now have a mitre, if he would maintain the name of a bishop.” There is a reason invented from that crafty interpretation of the law, that they may be called bishops of one church, or other churches given them in commendam, and all may be robbed. Time would faile me if I should reckon up the cheats which are daily excogitat against one law. But albeit these things be most unbeseeming as well the name of a Pope as of a Christian, yet their tyranny rests not here. For such is the nature of all things that, when they once begin to fall, they never stay untill they fall headlongs into destruction. Will you have me to shew you this by a famous example? Do you not remember upon any of the Roman emperours blood who was more cruell and wicked than Caius Caligula?

M. There was none that I know of.

B. Now what was his most nefarious [48] villany, think you? I do not speak of those deeds which Popes do reckon upon some reserved cases, but in the rest of his life?

M. I do not at present remember.

B. What do you think of that, that having called upon his horse, he invited him to sup with him? Set a golden grain of barley before him and made him Consul?

M. Indeed it was most impiously done.

B. What think you of that, how he made the same horse his colleague in the priesthood?

M. Do you tell me that in good earnest?

B. Indeed in good earnest, nor do I admire that these things seeme to you feigned. But that Roman Jupiter of ours hath done such things that those done by Caligula may seem true to posterity. I say Pope Julius the Third, who <it> seems contended with Caius Caligula, a most wicked wretch, for preheminence of impiety.

M. What did he of that kind?

B. He made his ape-keeper, a man almost more vile than the vilest beast, his colleague in the papacy.

M. Perhaps there was another cause of choosing him.

B. Some are reported indeed, but I have picked out the most honest. Seeing then so great a contempt, not only of the priesthood, but also a forgetfulness of humanity arise from this freedome of interpreting lawes, beware you think that to be a small power.

M. But the ancients seeme not to have thought it so great a business of interpreting, as you would have [49] it seeme to be. Which by this one argument may be understood, because the Roman emperours granted it to lawyers; which one reason doth overturne your whole tedious dispute, nor doth it only refute what you spoke of the greatness of that power, but that also which you most shun, it perspicuously declareth what power they granted to others of answering rightly was not denyed to themselves, if they had been pleased to exerce that office, or could have done it by reason of greater affaires.

B. As for those Roman emperours whom the souldiers did choose indeliberately and without any regard to the common good of all, these fall not under this notion of kings which we have described, so that by those that were most wicked were they chosen who for the most part were most wicked, or else laid hold upon the government by violence. Now I do not reprehend them for granting power to lawyers to interpret the law. And albeit that power be very great, as I have said before, it is notwithstanding most safely concredited to them to whom it cannot be an instrument of tyranny. Moreover it was concredited to many whom mutuall reverence did hold within the bounds of duty, that if one decline from equity, he might be refuted by another. And if they should have all agreed together into fraud, the help of the judge was above them, who was not obliged to hold for law [50] what ever was given by lawyers for an answer. And over all was the emperour, who might punish the breach of lawes. They, beeing astricted by so many bonds, were hemmed in, and did fear a more grievous punishment than any reward of fraud they could expect. You see, I suppose then, that the danger to be feared from such kind of men was not so great.

M Have you no more to say of a king?

B. First, if you please, let us collect together what is already spoken, so that the more easily we may understand if any thing be omitted.

M. I think we should do so.

B. We seemed to be at accord sufficiently concerning the origine and cause of creating kings and making lawes, but of the lawgiver not so; but at last, though somewhat unwillingly, you seeme to have consented, being enforced by the strength of truth.

M. Certainly you have not only taken from a king the power of commanding lawes, but also of interpreting them, even whilst I as an advocat strongly protested against it. Wherein I am afraid, if the matter come to publick hearing, lest I be accused of prevarication for having so easily suffered a good cause, as it seemed at first, to be wrung out of my hands.

B. Be of good courage. For if any accuse you of prevarication in this case, I promise to be your defence.

M. Perhaps we will find that shortly.

B. There seems to be many kinds [51] of affaires which can be comprehended within no lawes, whereof we laid over a part on ordinary judges, and a part on the kings council by the kings consent.

M. I do remember we did so indeed. And when you was doing that, wot you what came into my mind?

B. How can I, unless you tell me?