JOHN WILDMAN,

Putney Projects. Or the Old Serpent in a new Forme (30 December 1647)

|

|

| John Wildman (c. 1621– 1693) |

[Created: 24 February, 2024]

[Updated: 24 February, 2024] |

Bibliographical Information

, Putney Projects. Or the Old Serpent in a new Forme (London, 1647).http://davidmhart.com/liberty/Levellers/Wildman/1647-12-30_T124-Wildman_PutneyProjects/index.html

ID Number: T.124 [1647.12.30] John Wildman (with William Walwyn), Putney Projects. Or the Old Serpent in a new Forme (30 December 1647).

Estimated date of publication: 30 December 1647.

Thomason Tracts Catalog information: TT1, p. 580; Thomason E. 421. (19.)

Note: This is part of a collection of Leveller Tracts and Pamphlets.

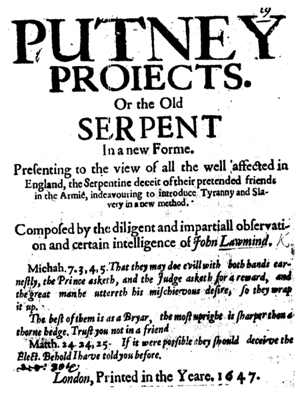

Full title

John Wildman (with William Walwyn), Putney Projects. Or the Old Serpent in a new Forme. Presenting to the view of all the well affected in England, the Serpentine deceit of their pretended friends in the Armie, indeavouring to introduce Tyranny and Slavery in a new method. Composed by the diligent and impartiall observation and certain intelligence of John Lawmind.

Michah. 7. 3, 4, 5. That they may doe evill with both hands earnestly, the Prince asketh, and the Judge asketh for a reward, and the great man he uttereth his mischiervous desire, so they wrap it up.

The best of them is as a Bryar, the most upright is sharper then a thorne hedge. Trust you not in a friend.

Matth. 24. 24, 25. If it were possible they should deceive the Elect. Behold I have told you before.

London, Printed in the yeare. 1647.

[1]

PVTNEY PROIECTS. OR The Old Serpent in a new forme.

GOds present great designe in the world is, the shaking of the powers of the earth, and marring the pride of all flesh. Isay 2. 11. The lofty lookes of man shall be humbled, and the haughtinesse of men shall be bowed down, and the Lord alone shall be exalted in that day. For the day of the Lord of Hosts shall be upon every one that is proud and lofty, and upon every one that is lifted up, and he shall be brought low.

To day is this Scripture fulfilled in our eares, God is humbling the lofty, the pride of every state in this nation is already fallen, the King, Peers, Parliament, Grandees in the Army have lost their glory.

It hath been the sinne of England, to trust to an Arme of flesh, and therefore the curse denounced against fleshly confidence is justlyfulfilled.

When Tyranny brake forth from the Kings throne a Parliament was our refuge and the rock of our confidence: When unrighteousnesse appeared in the Parliament, the Army was our refuge, and we hoped, they should save us.

But we see that all are but flesh and not spirit, they are but men, and not God: we may truly say of our selves as it is prophesied of the day of the Lord. Amos 5. 19. It is with us as if we fled from a Lyon, and a beare met us, and fled from a beare, and leaning our hands on the wall a Serpent bites us.

How confidently hath the honest partie in England cast themselves, their lives, their all, into the laps of some eminent Commanders in the Army, supposing that the very sunne might as soone be pluckt from the heavens, as they warpt from the wayes of righteousnesse. But Proh dolor how are our hopes perished how have they by their unlawfullnesse, and sinfull compliances, almost insnared us again in our enemies fetters.

We desire not to blazen, or make publique the blemishes of any, much lesse of such men, whom God once so highly honoured with the presence of his mighty power, enabling them to conquer and triumph over the most [2] insulting enemie, but periat potius unus equqm unitas, its better that a few mercinaries should rot, and their honour be forever layed in the dust, then that a people, a nation should perish, by putting their confidence in broken reeds, which will pierce their hands.

To unfold therefore plainly the mysterie of deceit, wherein our chiefe Commanders in the Armie walke, two things are necessary. 1. To spread abroad the cloak of their promises, wherewith they have covered themselves. 2. To present them naked in their actions.

To begin with the first. In the time of Cromwells and Iretons straights, when Hollises and Stapletons faction domineered over them, and intended to dethrone them, then were their words smoother then oyle their words dropped like the honey Comb, into the mouths of the hungry, oppressed people, how were their words seemingly bedewed with teares in pittie and compassion to the distressed people how did they represent their hearts devided, and rent in sunder with hearing the dolefull cryes, and beholding the bloody teares of the oppressed. What professed gallant resolutions did the seeming deep impression that the peoples miseries made upon their hearts beget in them? how did they appearingly slight their estates, the enjoyment of their relations, yea their dearest blood in comparison of the peoples liberties? what gallant principles of freedome and righteousnesse did they professe? how loud were their cryes against all Arbitrary powers and all seekers of private or particular interests? how positive and absolute were they in their resolutions to have all the liberties of the nation cleared and secured, how did they seeme impatient of any delayes or protraction of time.

To present to your view some particulars.

What valiant Champions did these men appeare for Englands freedom? how did old English valour, and undanted courage to oppose the stoutest enemies of the publique interest and advantage sparkle forth in them upon June 4. and 5. 1647. When they boldly ingaged in opposition to the Parliaments orders not to disband nor to divide until they had security that the freedom of the poeple of England should not be subject to the like injury, oppression, and abuse as had been attempted: Did ever the most faithfull Patriots to the most noble nation passe a larger ingagement to their Country then this? Who could have forborne to conclude, that these would have been our worthy [Editor: illegible word] that would have pierced the bowels of every oppressor and destroyer of England? Who could upon the sight of this Engagement but imagine that these would never have given themselves rest untill they had seene the top-stone laid in the beautious fabrick of Englands native freedom? [a] [3] Did they not oblige themselves in this Ingagement, to bid defiance to every oppressor and abuser of the people, to the King Lords, Commons in Parliament, Committees, Lawyers, and all others, were they not hereby bound to stand like the Iewes with NEHEMIAH with their swords in their hands, not only untill Englands breathes were repaired, but also untill the strongest possible iron gates were composed to defend the conscientious persons, liberties and estates of all Englishmen from oppressors: indeed could any ingage to procure more perfect freedome for the people, then they did in this Ingagement? Can more be said then this that they would have security, that the people should not be subject to the like injuries or abuses as had been attempted? All men know there had been attempts to offer all kinds and degrees of wrong and abuse to the people and therefore they promised and ingaged to secure them from all.

2. How were the purest most exact principles of freedome and righteousnesse, professed by these to be the only grounds where upon they thus ingaged even against the Parliament, the undefiled law of nature, [b] was declared to be the rule of their proceedings in their Declaration of Jun 14, the establishment of Common and equall right and freedome to the whole Nation was promised should be their study, [c] All purposes or designes to advance any private interest, were disavowed and disclaimed: [d] Yea, they when the Parliament unvoted and expunged from their Iournall booke those votes whereby the Soldiers were declared enemies for petitioning in order to their satisfaction, these then professed such principles of freedome and common good, that they slighted the particular reparation in that case of common contentent and declared, that they did not value or regard their own injustice or reparations in comparison to the consequence of the one, or practices of the other to the future security of common right and freedome in the nation. [e]

And how did these pretended Patriots seeme to disdaine selfish private interests or advantages they seemed to think it too base and unworthy for them to be a marauding Armie, to service the arbitrary power of a state for money, & therfore they disavowed their standing as such an Army, [f] and declared, that they tooke up Armes in judgement and conscience as called forth by the Parliaments Declarations, to the defence of their own and the peoples right and liberties? And were not their avowed principles as purely free, as [Editor: illegible word] purely publique? [g] They declared the equitable sense of the law as the supreame [Editor: illegibe word] and so dispense with it when the safety of the people is concerned, and likewise that all authority is fundamentally seated in the office, and but ministerially in the persons. Were ever clearer principles of freedome planted in any heroic hearts, then proceeded from these mens mouths? did not every [4] discerning eye see the tendency of these gallant pure principles, to perfect-freedome and common justice? Were not the hearts of the oppressed people by the sight of these declared principles (and Engagements upon them) filled with living hope of perfect freedome from all kinds of tyranny or oppression, though sheltered under the visible formes of Kingly, Lordly, or Parliamentary power. Did not every unprejudiced and truly English heart expect that the crooked wills of man should no more have been the measure of Englands freedome, but only the straightest rule of nature. [i] [j]

3. What fiery zeale and burning indignation did these our seeming, Saviours breath forth against the invaders of our native freedome, and obstructors of their speedy settlement’s were not their words speares and swords, and hot burning coales against Hollis, Stapleton, Waller, and that faction? Did not these stout hopefull Patriots reach the tongues of the whole Soldery to cry aloud at New-Market and Triple Heathe Justice, Justice against those invaders of Englands freedomes, was it not the first borne of their desires, that the heads of that faction might be suspended the house upon their generall charge of treason against them; and had not the purging the house from these and other perverters of Justice the preheminence of all their desires in that choicest of their Declarations dated Iune 14. 1647. Yet they were so transported with morale for the removal of those Apostate Members, that in Iune 23. 1647. at St. Albans, they prefixed a day to the Parliament, for their suspension from the House, menacing them to take in extraordinary ways unless by that day they were suspended, and appearing so solicitous were they of purging the house from all obstructors of Common freedome and good that when the Parliaments Commissioners on Iuly 7. 1647. invited them to hasten the Treaty between the Army and the Parliament for a settlement, they answered that no comfortable effect of a Treaty could be expected so long as the Parliament was constituted of some persons whose interests were contrary to common good, [k] thus they represented themselves even jealous for the peoples sake and industrious (even by exaltation) for freedome and justice.

4. How did these promising Patriots seem to be so devoted to the peoples services that sorrow and sadnesse appearingly filled their hearts, in beholding the efficacy of their endeavours for these, by means of the corrupted itself, they professed themselves as baptized, as the very hearts because their way was not cleare to purge the House from those unworthy men, who were banding and defending against publique good, and upon this account when 70. or 80. usurpedthe Parliamentary power, and complottedthe imbruing the people in blood, their hearts of wood to abound [5] with joy, that God had cleared their way to purge the House from those treacherous breakers of their publique trust, then said Cromwell and Ireton, the Lord hath iustified our cause, and hath suffered the enemies of our peace and freedom, to dig pits of destruction for themselves; they have written their wickednesse in their foreheads, and made the way plaine for their own ejection from the house. Thus their feares, sorrowes, joyes and delights had the peoples good and freedome for their visible Center.

5. What detestation and abhorrency of the Kings corrupt interest did these pretended lovers of their Country then felt? they seemingly loathed it, as being the originall of the peoples slavery and misery, the very spring from whence arise all those floods of oppression and tyranny, that overflowes the people, they esteemed it the highest treason to court that common strumpet the Kings interest, they iudged them adulterers, breakers of their Covenant with their spouse, their Country, which gave but a kind salute to that Harlot. Yea, they thought the Courtiers to be but pimpes and panders to that mother of tyranny, and therefore they preiudged his honesty, whoever did but privately converse with them.

This was that high treason with which they charged Hollis, Stapleton, and that faction, that they had private conference with some of the Kings Courtiers, [l] and bowed the head to kisse the Kings interest, by advising the King to a personall Treaty, and this was the high aggravation of Hollis his treason that he reviled those well affected Members [m] of Parliament, who were pure from any base compliance, on purpose to ingratiate himself with the Kings party, Thus their hatred of the peoples capitall enemy seemed to be so absolute, so perfect, that they hated even the favour of that royal party as they were such, viz. supporters of the Kings inslaving interest.

6. How tedious and irksome to these our deliverers were the delayes [n] in clearing and securing the peoples liberties, when the hopes of the people deferred made their hearts sick? How did they professe the nearest and deepest sympathy in their Declaration of June 44. “And how did they declare June 23. at St. Albans, That their respect to the peoples safety inforced them to admit of no longer delayes, and that they could alow the House not above foure or five dayes, where in they might give assistance and security to them and the people, of a safe and speedy proceeding to settle the Armys and the Kingdomes rights and freedoms. [o] [p]

Thus common right and freedome was visibly the choice object of all their actions and intentions, that was seemingly the golden ball of their contention, the ultimate end of their hazzardous race. Whatsoever they [6] desired for themselves, was professed to be insisted upon only in relation to that publique end, their hearts seemed to be so inflamed, with desires of the peoples rights and freedomes, that no quiet content or satisfaction could possesse them, so long as the people groaned under Tyranny and Oppression, they seemed so farre to prefer the peoples good to their own advantage, that they declared, they would never have entered into so hot a contest with the Parliament, for reparations for their private wrongs, abuses, or incroachments upon their particular freedomes, had not their suffering those particular wrongs, been preiudiciall to common freedome.

Now O yee Commons of England, behold these your great Commanders thus cloathed with the glorious garment of their Declarations, of such a curious texture, thus adorned with variety of the fairest promises, as so many bright orient pearles, and doe not they appeare like Absolon without spot or blemish from head to foot? are they not like to Saul, higher by the head then all the people? can you forbeare to cry, there is none like unto them? did ever more hopefull sonnes spring from Englands fruitfull wombe? did ever more lightsome stars arise in this Horizon? did not their hearts seeme to be the thrones of righteousnesse, and their breasts the habitation of goodnesse and compassion to the oppressed, was not Iustice as a robe to them, and mercy as a diadem? did they not appeare to goe forth in the strength of the Lord, to break the lawes of the wicked and oppressors: to pluck the spoyle out of their teeth, did they not give such hopes of deliverance to those who were bound in chains of tyranny, and of reliefe to the poore afflicted, which had none to help them, that the scores that heard their words rejoyced, and the blessing of many that were ready to perish came upon them.

And what Eagle eye could at first discerne, that this glorious cloathing was but painted paper? What jealous heart imagined that these promising Patriots were only sweet mouthed courtiers who could have harboured the least suspition that these visible stars of heaven were but blazing comets? who imagined, that the most mighty wind from Court could have shaken such seeming immoveable pillars of freedome and justice? Who could have believed that the resisters unto blood of all inslaving Arbitrary powers, should have drunke the wine of the Kings delusion.

But if love to my native country, did not at Queen Regent give a mandamus to my pen. I should (like Shem and Iaphet) string a garment to cover the nakednesse of these, whom I have so much honoured but Amicus Socrates, amicus Plato, sed magis amica patria I dare not conceale treachery [7] against my dearest Covntrey, I shall therefore impartially communicate the actions of Cromwell, Ireton, and their adherents in their continued series, and when your eyes shall behold them naked, I shall submit them to your censure.

First; I shall not prejudge the singlenesse of Cromwells or Iretons hearts as to publique good, in their first ascociating with the Army at New market, but its worth the knowing, that they both in private opposed those gallant endeavours of the Army for their Countries freedom. Yet their arguments against them, were only prophesies of sad events; confusion and ruine, said they, will be the portion of the actors in that designe, they will never be able to accomplish their desires against such potent enemies. They were as clearly convinced, as if it had been written with a beam of the Sun, that an apostate party in Parliament (viz. Hollis his faction) did subject our lawes and liberties to their inordinate wills and lusts, and exercised such tyranny, iniustice, arbitrarinesse, and oppression, as the worst of arbitrarie Courts could never paralell. [r] But to oppose a Party of Tyrants so powerfull; hic labor hoc opus est, there was a Lyon and a Beare in the way. And lest meer suspition of their compliance with the Army in any attempt to affront those insulting Tyrants should have turned to their prejudice, they were willing at least by their Creatures, to suppresse the Soldiers first most innocent and modest petition. C. Rich sent several Orders to some of his Officers; to prevent subscriptions of that petition. And the constant importunity and solicitation of many friends, could not prevaile with Cromwell to appeare, untill the danger of imprisonment forced him to flie to the Army, (the day after the first Rendezvouz) for shelter. And then both he and Ireton joyning with the Army and assuming offices to themselves, (acting without Commissions, and being outed by the self denying Ordinance of Parliament, and the Generall having no power to make Generall Officers,) they were ingaged in respect to their own safety, to crush and overturne Hollis his domineering, tyrannicall faction. And to that end their invasion of the peoples freedome, their injustice and oppression, [s] was painted in the most lively colours to the peoples eyes, and Petitions to the Generall against those obstructors of justice in Parliament, drawn by Cromwell himself, were sent to some Counties to subscribe, and then the most mellifluous enamouring promises were passed to petitioners of clearing and securing their rights and liberties, then the Generall ingaged himself to them, [8] that what he wanted in expression of his devotion to their service, should be supplyed in action: And hereby their names were ingraven in the peoples hearts for gallant Patriots; and the most noble Heroes of our age, and then they boldly encountered their daring enemies with a thundring charge, and demanded them as conquered before their tryall; then they boldly marched towards their Quarters at Westminster, crying IVSTICE, IVSTICE, We cannot stand as lookers on, to see the Kingdome ruined by the obstruction and deny all of justice. But did not the issue declare that there was little simplicity or integrity of heart in those sweetest Eccohs of justice? was it any more then partiall respective justice which they pursued? nay, was it not rather animosity and revenge? then pure impartiall justice, had single simple justice been the object of their desires, then they could have known no bounds or limits, no respects or relations. But injustice oppression, & corruption in whatsoever subject would have been the object of their hatred, and the execution of the law upon them, their desire and intention [t] they would have known no difference between the meanest Scavenger and the highest Lord, yea (that originall of injustice) the King himself. But their justice was restrained to eleven Members only, though they could have produced as high a charg against ten times 11. (for the particular matter of their charge was to seek, after they had in generall charged them) they knew that neer 200. of the Commons besides the Earle of Northumberland and other Lords were charged by Mr. Waller, [v] for correspondence with the King in that plot against the City, for which Tompkins and Challener were hanged. Cromwell knew of a charg to purpose against the Earl of Man. and M. Lenthal the Speaker, they knew that Comittees and sub-Com. Sequestrators, Treasurers, &c. were sinks of rottennes, corruption and impiety. Yet though their cry for justice was universall, it was confined to eleaven persons only, nay the issue hath discovered, that justice against them was not their prime intention. When they only voluntarily absented themselves from the house, these just men (contrary to the dictates of their consciences) applauded them for their modesty, [w] and were contented. And though they exhibited a charge against them, they never prosecuted them further upon it, or moved for securing their persons untill a legal tryed yea though the time which the House permitted those Members to be absent be long since expired, yet they and their crimes remaine in the grave of forgetfulnesse. Is it not by these things grosly [9] palpable? that the superiority of Hollis his faction to them, and their proud domination over them was the greatest became in their eyes, or (in the largest Charity) that their private security or liberty was the Center of their actions and intentions: What face of justice appeares to a single impartiall eye even in this master piece of their pretended justice? yet in this I judge not.

But when by these specious pretences (like so many silver stayres) they had ascended to the highest thrones of power in England, so that the Parliament it self trembled at the shaking of their rod, and every of their desires to the House was a mandamus, when their power like a mighty streame could easily have swept away every obstruction to justice, peace and freedome, Let us observe what was then the fruit of those fairest blossomes of their promises.

After Cromwells awfull approach to Westminster, and his imperiall Messages to the House, had commanded Hollis his faction to absent themselves, Cromwell being then secure from the impoysoned arrows of their mortall malice, and having subiected even ad annum to his beck both King and Parliament, his first publique actions could be then no other but the expresse Character of his intentions. Therefore let the Manifesto upon June the 27 from Uxbridge be perused, let the matter of those seaven proposalls therein be duely weighed, upon the granting whereof, they promised to draw back from London, & doth not the whole amount to this? That the Parliament should own them for their Army, and provide them pay, and vote against all opposite forces. There’s not the least punctum of Common iustice moved to be done before their retreat, not so much as a Declaration insisted upon against those enslaving presidents of burning petitions, and abusing petitioners, no publique vindication of the Army, as to their right of petitioning, [x] and against that monster of iniustice and tyranny, the Declaration against them, as enemies to the State, for petitioning, that was the oppression of the Army, whose sad Consequence did equally extend to all the people, tending to destroy all freedom, and render all the people the worst of slaves. [y] Yet the remedy of that was neglected, and all publique good pretended on June 23. to be the primary reason of their march to London, was thus by June 27. in the grave of Oblivion. Doubtlesse the above mentioned and many other foundations of freedome might have been setled in as short a time as the matter of the seaven proposalls, but it seemes 4. dayes changed their judgements, they thought the oppressed, inslaved [10] people could admit of longer delayes, and beare the yoaks of tyranny and oppression longer.

Its a known maxime, that the end of an action is the center where the heart rests. I wish the application be not true, that their private interest was their highest end, and therefore in the inioyment of that they acquiesced. Questionlesse, had the cryes and groanes of the oppressed, took such deep impression upon their hearts, as they professed [z had their hearts been fired (as they appeared) with the sacred flames of love to their native Country, they would have travaylled in the birth of its perfect peace and freedome, and been pained till they were delivered, they would have said like Pompey, taking ship in a dangerous storme, with corne to relieve his famishing Country, Necesse est ut eam non ut vivam, its more necessary that we relieve the oppressed, then preserve our lives A dayes delay, when the Country is even expiring its last, would have been like a sword in their bones, they would have deeply laid it to heart that they kept many thousand in Armes, upon pretence of clearing and securing to the people their rights and freedomes; and that every day they neglected or delayed their settlement, they eate their bread for nought, yea were but THEEVES AND ROBBERS that spoyled and destroyed the people. But alasse, though Jehu like they marched furiously towards London, saying, come see our zeale for IUSTICE, MERCY, and FREEDOME, for our perishing country, yet they retreated without distilling the least drop of those sweetest waters of iustice and mercy upon the thirsty weary people, yea without clearing the fountaine, viz, purging the Parliament. They drew back from London, and their righteous principles at the same time, From Vxbridge they retired to Wickham, from thence to Reading, and to as great a distance from iustice as from London: then the enemies were left to obstruct our peace and freedomes, and to complot and designe mischiefe, then were such disputes at a distance, as occasioned most distracting and consuming delayes, then were those condemned of rashnesse and imprudence, who breathed forth quicknings and hastnings, or condemned their neglect sloathfullnesse, feare or slownesse. Though Cromwell himself was forced to confesse the reason and iustice of what those offered, when their delayes had indanger’d a new warre.

3. While these pretended Champions thus slept, the Court Devill laboriously sowed those cursed tares of Court principles, and their [11] hearts being a naturall soyle for those poysonous seeds, they choaked those sprouting principles of freedom & justice. Yea from that time the King had his Emissaries at the Head Quarters, viz. Sir John Berkley, Mr. Ashburnham, and Maior Boswell, these by courtings and flatteries, were to foster those seeds of Domination, Lordlinesse, and Arbitrarinesse, that were already sowen, and none found better entertainment from Cromwell and Ireton then these, none had more of Cromwells gracious nodds, or Courtly imbraces. And this visible correspondence with the Court being maintained by the Officers Generall, some of the inferior readily conformed to their example, and none could kneele more courtly to kisse the Kings defiled hand then they: yea suddenly the Kings flatteries proved like impoysoned arrowes, which infected all the blood in Cromwels and Iretons veins, his insinuations & unlimited promises proved an intoxicating cup, which polluted their iudgements, and poysoned their hearts, and from that bottomlesse fountaine of wickednesse, tyranny, and cruelty the Kings heart was infused such venemous notions into their braines, as converted all their speeches, actions, and councells into a courtly forme. And in this particular, I cannot but observe their palpable Hypocriste in their Declarations or else their grosse Apostacie from their first principles.

They declared Iune 14. 1647. That they continued in Armes in iudgement and conscience to the ends specified in the Parliaments Declarations. [a] And could they be ignorant? that the Parliament had declared the intent of the War to be the removing of the Kings evill councell from him.

But have they not opened a free way of access to the King, for his most desperate, Malignant Councellors. I cannot spare time or paper for all their names. The Duke of Leonex, Earle of Ormond, Earle of Cleveland Sir Marmaduke Langdale, Sir Francis Cob, Sir Edward Ford, Sir John Barkley, Mr. Ashburnham, Col. Legg, &c. Cum multis aliis Did they not cause that compendium of wickednesse Col. Legg, to be admitted of the Kings bed Chamber? had not these publik enemies by their indulgence such command at Court? that they could be admitted when Col. Whaly himselfe (the chiefe Commander of the pretended guard) just been excluded, and were not these suffered? without check or controle to complot or designe mischiefe with the King, and to take the assistance of those grand Incendiaries in France and Holland, had they not their known constant dayes of writing letters for that intent? Certainly [12] these were the repairers of the Kings broken Iuncto, the restorers of its rotten elected Members.

But further, have not they maintained the most constant possible correspondence with the King? though they declared it treason in Mr. Hollis, to make private addresses to the Kings party yet they have multiplied private addresses to the Capitall enemie, the King himselfe: they reputed Mr. Hollis his correspondence with the King, to be a breach of his trust, a breach of his oath taken in Iune 1643. a breach of the Parliaments Ordinance in Octob. 1643. [b] But had they esteemed it reall treachery, periury, and contempt of the Parliaments power, they durst not have so far transcended their predecessors in such impleties. They could never have been so hardned as to persist weeks and moneths in a continued course of correspondence, they would never have suffered Maior Boswell (that known Intelligencer between the King and Queen) to have been their frequent Messenger to the King; they would never have suffered him to remaine constantly almost at the head quarters, and to make it his imployment to corrupt the Soldiery, and advance the Kings corrupt interest in their hearts; they would never have entertained Sir Edward Foord, Iretons brother in law (a known Papist, who brok prison, and by right is a prisoner in the Tower) they would I say, never have provided him and his family Quarters at the Head Quarters, that he might be the Kings Resident Solicitor, that he might lye in Iretons bed and bosome. They would never have suffered the Head Quarters so to swarme with Cavialeers, that no word against the Kings interest could be spoken in the streets, but it was newes for the King. That there could be no transactions of affaires in the Generall Councell, but the King had the full relation in two houres; who can imagine what these men intended in charging the eleven Members with treason, for petty correspondence with the Kings party, when they thus boldly before any peace concluded, have thus openly maintained the nearest intimacy with the King himself, and his worst adherents. Surely their meaning was, that Hollis was guilty of treason against themselves, for diverting the Kings affections from them, or making a Monopoly of the Kings favour to their Presbyterian faction. And therefore it was inserted into Hollis his charge as no small crime, that he endeavoured to ingratiate himselfe with the Kings party by reviling them. But have not Cromwell, &c. joyned himself to the worst of the royall party in the strongest bands of [13] amity? have not his endeavours been superlative to purchase their favour? have not his countenance and indulgence to them been so eminent? that by the influence thereof, their malignity have gained such audacity, that they have insulted over, and trampled upon the most faithfull to God and their Country. And when honest men have breathed out their complaints of most insufferable abuses and threatnings, when some have shewn the halters hanged upon their doores by those common enemies, with their pictures going up the Ladder to the Gallows, yet Cromwells eares have been deafe. Thus whilest Cromwell judged the 11. Members, he have condemned himself, for he himself have exceeded in the same wickednesse for which he judged them. Thus he that said a man should not commit adulterie with the Kings interest, he himself is the greatest adulterer, he that said he abhorred that grand Idoll the King, even he hath worshipped and adored him.

4. But least these passages should seeme obscure, I shall proceed to examine the most eminent action of these great Commanders, even the first borne of Iretons braine, the Proposalls from Colebrook, which as they say containe the particulars of their desires, in order to the clearing and securing the rights and liberties of the people, and setling a lasting peace. [c] By these you shall passe the most certaine judgement upon your professed Patriots, let it therefore be diligently observed, whether the foundations of the peoples freedome be not undermined in those, and whether the totering pillars of the Kingly and Lordly interest, be not strongly supported?

But Oh the Commons of England, I must not defraud or beguile you with these proposalls, by stiling them the Armies proposalls, I confesse I know not whether I may properly call them the Armies as now they are, I scarce beleeve that they passed a Generall Councell, before they were published. But thats not all, for they last of all passed the Kings file, and therefore it was no wonder that he moved for a personall Treaty upon those Proposalls, When these Proposalls were roughly drawn, IRETON IN A PRIVATE CONFERENCE WITH THE KING, INGAGED HIMSELF TO SEND HIM A COPY, and though at the first some of the other Generall Officers opposed it, yet Ireton professed he was fixed in his resolution to fulfill this INGAGEMENT, though the General should hang him, accordingly a Copy of them was sent by Huntington, Cromwells own [14] Maior, and the same Copy was returned with the Kings crosses and scratches upon them, with his own pen. Afterward some conferences were appointed with the King and many mssages were sent by the King to the grand Officers by SIR IOHN BERKLEY: At last SIR JOHN BERKLEY and Mr. ASHBVRNHAM brought the Kings answer to them at Colebrook on Angust 1. & the Proposalls bear date, August 2. Now whether this were a Treaty with the King actually I iudge not, but let it be remembred, that it was the first Article of the Charge against the 11, Members, that Mr. Hollis advised the King to a Treaty with the Parliament, but is this the prime passage worthy of observations in this intercourse or Treaty with the King (if it may be so called,) that the PROPOSALLS WERE ALTERED in five or six particulars, NEERLY RELATING TO THE KINGS INTEREST.

1. When the Proposalls were first composed, there was a small restriction of the Kings Negative voice, it was agreed to be proposed, that whatsoever bill should be propounded by two immediate succeeding Parliaments, should stand in full force and effect as any other law, though the King should refuse to consent. By this, the people should not have been absolutely vassalls to the Kings will, they should have been under some possibility of reliefe under any growing oppressions. But this intrenched too much upon the Kings interest, to be insisted upon. This was an offer to strike at the KINGS DEAREST DARLING, his principle inslaving power, whereby he makes all the people depend upon his will for all their succour, and reliefe under any common pressure, and therefore this was expunged.

2. In that rough draught it was proposed, that all who have been in Hostility against the Parliament, be incapable of bearing office of power, or publique trust for ten yeares, without consent of Parliament. But in further favour of the Kings interest, these ten yeares of excluding Delinquents from power or trust, were changed to five yeares.

3. It was further added, after this intercourse with the King, that the Councell of State should have power to admit such Delinquents to any office of power or trust before those five yeares were expired, and that by the Kings insinuations to that Councell (if any such should be constituted) and their owne relations, the greatest Delinquents in England, would be in the greatest tryst before twelve months end.

4. In the Composure of the proposalls it was desired that an act [15] for the extirpation of Bishopps might be passed by the King: but if there should be none to preach up the Kings interest, and by flattering seduceing words to beguile the people, and foster high imaginations and superstitious conceits of the King in their hearts, under the rude, and generall notion of authority, his Lordlinesse and Tyranny would be soone distasted. And therefore this proposall was so moderated that the office and function of Bishops might be continued, and it is now only proposed that the coercive power and jurisdiction of Bishops extending to any Civill penalties upon any be abolished.

5. After this Treaty with the King, the proposall for passing an Act to confirm the sale of Bishops Lands was wholly obliterated; and though the Army afterward desired the Parliament to proceed in the sale and alienation of those Lands, yet that was none of their proposals in order to a peace with the King, but according to their proposalls for a setled peace, the King was first to be established in his Throne with HIS VSVRPED POWER OF A NEGATIVE VOYCE to all Lawes or determinations of Parliament, and then they knew that the King might be at his choyce, whether he would permit an alienation of these Lands, Nay doubtlesse they knew his resolution to reserve those Lands, to maintaine his Bishops glory and pompe, to cause them to be had in admiration amongst the people, and to enable them to exercise a Lordly command over them, that with the more facility they may induce the people much more to admire, the greatnesse and magnificence of their Soveraigne Lord and CREATOR, and to adore him under that awfull title of his most sacred Majesty, and simply to account it their honour to be vassalls to his basest lusts.

But whether those proposalls be purely Iretons, or begotten by the Courts influence upon his braines as sol et homo generat hominem; yet since they are called the Armyes proposalls, let them be considered as they are and when they be opened, let every seeing Eye judge whether they be any other then a Close Cabinet wherein are locked up the KINGS CHOYSEST JEWEELLS [d] viz. HIS ENSLAVING PRINCIPLES whereby his Tyranny over the people is maintained.

There are five Principles, that appeare in the Kings Lustfull Eye, to be the most sparkling Diamonds, wherewith he desires to adorne his Crowne.

1. Principle That all power and authority in this Nation, is fundamentally [16] seated in the WILL of him, and his heires, and successors. That his Le roy Le vult, HIS ROYALL PLEASURE is the originall of al authority, to be executed, Its his WILL (saith he) which gives the being to Majors, Bayliffs, Justices, Sheriffs, Iudges, Peeres, yea to Parliaments; he arrogates to himselfe the Title, of THE [e] FOVNTAIN OF IUSTICE AND PROTECTION, as if all Justice and protection that proceeds to the people from any power or authority, did depend solely upon his WILL, and pleasure.

Its needlesse to seek for evidence, that the King endevours to erect to himself this highest Throne, wherin he would sit like God to be depended upon, and adored by the people as God.

The experience of his whole reigne witnesseth abundantly, that his absolute WILL was the sole CREATOR of Lords, Earles, Marquesses, &c and Iudges, Sheriffes, Justices, were the meere products, or CREATVRES of the same will. Yea an absolute omnipotency was claimed, as the proper attribute of his will. It was his WILL which did annihilate officers, as well as create them. At his PLEASVRE, Judges were displaced, because they refused to do against their [f] oathes, and consciences, and least his WILL should have been restrained, so that he could not have displaced Judges, at pleasure, as well as placed them; the accustomed clause in the Judges pattents, quam diu so bene gesserit, id est, that he should be Judge during his faithfull execution of his office, this clause was left out and instead thereof durante bene placito was inserted, [h] id est, they should continue during the Kings PLEASVRE. And likewise to abolish all limits to his WILL, that relique of freedome, the pricking of Sheriffs was destroyed, and Sheriffs made by his obsolute WILL. And his WILL was fruitfull in bringing forth new Iudicatoryes, and new powers in old; witnesse the pretended arbitrary Court of the Earl Marshal, the Star chamber, high Commission [i] Councell table, the Courts of the President, and Councel in the North, the oppressive powers of the Chancery, Exchequer-Chamber, Court of Wards, the stannery Courts, and other such forges of misery, violence, and oppression. Yea the being of that supreame authority of Parliament, is claimed to have its being and vse solely from his WILL: the Kings owne words are these, we (saith the King of the Parliament) called [k] them, and without that call, they could not have come together, and (saith he) What the extent of their Commission and trust is nothing can better teach them, then our own writ wherby they are met. And he further adds, [17] were they not trusted by us when we first sent for them? and were they not trusted by us when we passed them our promise not to dissolve them? thus he claimes the peoples representative (who receive not only the Supream but all power immediately from the people) to be the Creature of his WILL to be called, or dissolved, to exercise power, or to be powerlesse at his pleasure.

The Kings second inslaving Principle is this.

That his absolute WILL is supream, or a law paramount to all the determinations of Parliaments. That his WILL can dispense with or anull all their Orders and Decrees, so that as his WILL gives a BEING to Parliaments, so likewise its to be the rule of all their Councells, and Decrees, the only point wherein all their resolutions must center, and all their conclusions or orders that run not paralell with his WILL, are null and void in themselves.

This principle, the Kings practice hath written in such Capitall letters, that he which runs may read it, hath he not alwayes claimed a negative voice to all lawes? And I should but light a Candle to shew you the Sun, should I frame demonstrations, to prove that his claime to a negative voice, amounts to this principle: whats the meaning of the negative voice but this? that every Order of Parliament is invalid, and no way obligatory, unlesse the King WILL. Should the Parliament spend seaven yeares in framing lawes, one breath of the King consumes them in a moment: his simple non placet, makes them all no better then Abortives, that never see the Sun. Though the Parliament as it represents the earthly Lord and Creator of the King, THE PEOPLE should condiscend so low, as to petition him to consent to a wholesome law which they have composed, yet if it suites not with his crooked will, its no better then an Almanack out of date; and doe not the ruins, and dessolations, the blood and misery of the Nation, sigh forth to every care, that this principle is ingraven in the Kings mind? was it not to maintaine this principle? that he hath made his footsteps in blood, that he hath given Commissions to powre out the peoples blood like water, to multiply rapes, rapines, murthers, and crueltys without number. Is it not to maintaine this principle? that he hath caused every street to be filled with the mournfull cryes, and brinish teares of the widdow and the fatherlesse.

[18]

O yee Commons of England! mistake not, this was the ground of the Kings quarrell against the Parliament. The quiver of the malice of the subverters of our lawes and liberties, being full of impoysoned arrowes, and their bowes being ready bent against all your noble Patriots in Parliament, and the faithfull to God and their Country, the wisedome of Parliament conceived it of absolute necessitie, to dispose of the Militia into such confiding hands, as it might be a shield and buckler unto them and the people. And accordingly an Ordinance was drawn for that purpose [l] in February 1641. and the King refusing obstinately to concurre, they [m] resolved on March 2. 1647. forthwith to execute their own Ordinance, thereupon the Kings indignation flamed against them, swearing by [n] God on March 10. that he would not grant the settlement of the Militia for an houre. But this principle was the bellowes to the fire of his wrath, that his WILL is supreme to all the resolutions of Parliaments. Consult his Declaration March 9. 1641. from New Market 1. part of book of Parliaments Declarations pag. 106. and his message from Huntington, March 15. 1641. 1. part book Declarat. pag. 114. prohibiting all the people to presume under pretence of Order, or Ordinance not consonant to his WILL, to execute any thing concerning the Militia, or any other matters, whatsoever. And on March 26. 1642. 1. part book of Declarat. pag. 126. he declares the Houses Ordinances to be void and NOTHING. Read the Kings Declaration of May 6. 1. part book of Parliaments Decla. pag. 175, 176. Read his Message about Hull, 1. part book Decl. pag. 182. and his answer to the Parliaments Remonstrance of May 19. 1642. 1. part book Decl. pag. 243. see his answer to the Parliaments Remonstrance of May 26. 1642. 1. part book Decl. pag. 289. 292. and in the same answer, book Decl. pag. 289 He collects from the Parliaments Remonstrance, such positions as are abominable to him, amongst which he inserts this, that the Parliament affirmes, he hath no negative voice [o] to lawes. But the Parliament being sensible that the people had betrusted them with all thats dearest to them, adheared to their resolutions of proceedings according to the fundamentall lawes, and their highest trust, to settle the Militia for the security of the peoples Lives, Liberties and Estates.

Thereupon the King by Proclamation of May [p] 27. 1647. breathed out most terrible menaces against all that should yeeld obedience to that Ordinance: and forthwith Commissions of Array were issued [19] out, and least that principle of the supremacy of his WILL, should have been obliterated, he resolved to have it written in red Characters with the peoples blood.

And though the curse of the Almighty, hath rested upon his right hand, and right eye, in his prosecution of that design, yet the whole current of his endeavours at present, tends to induce the Parliaments and Armie, to avow that principle by a law: and whosoever consults his last Declaration from Hampton Court, may observe that his indignation boyles against the opposers of a Negative voice, which he claimes for himself, and the Lords his Creatures, and the result of that is but this maxime; that the WILL of him, and of what Creatures he shall please to create, is supream to the determinations of the peoples representative. And though this maxime be pleaded for only in the negative, yet the consequence extends to establish it also in the affirmative: for the Kings WILL may be as justly supream to the Parliaments resolutions, in the question of his making a law against their consent, as of his denying a law against their desires.

The Kings third vasalizing or inslaving Principle is this.]

That its his essentiall propertie to sit in the throne as our God on earth, without any BAND upon him to conforme his actions to our lawes, as their proper rule. He arrogates to himself, a superiority to all lawes, and an exemption from all the censures and penalties which are the strength, vigour, and life of the lawes. He imagine himself to be exalted to that transcendent height, that its prophanenesse for the wisest, most noble Heroes, that ever sprung from Adams loynes; to presume Actiones inspicare, to pry into the Arke of his most sacred actions he fretted and fumed against the Parliament, for asserting that they had power to iudge [q] his actions, and whether he discharged his trust. And to what doe this amount: seeing he allowes not the supream authority of the Nation, the peoples Representatives, to passe judgement upon his actions, no not of his faithfullnesse to the people in his office, or treachery against them, by necessary consequence; no penalty can possible be inflicted upon him for the foulest crimes that can be the fruit of those seeds of Iniquity, wherewith his heart is filled Though he should by his immediate hand like Manasseth, fill the streets with the blood of the innocent, yet he shall be secure from all [20] the Arrowes of justice that can be shot from the bow of the law against him. And seeing he thus usurps a freedome from the judgement and censure of the law, how is he oblieged to regulate his actions by the law, doubtlesse the binding power of lawes meerly humaine, as they are such, consists in their censures and penalties annexed to them, to be inflicted upon the transgressors of them, and therefore his disavowing any iudge of his actions, is tant amount, as if he possitively and expresly averred, that the lawes are not the rule of his actions, and this would keep harmony or agreement with that avowed maxime, that THE KING CAN DOE NO WRONG. [r]

The Kings fourth inslaving Principle is this.

That the estates, liberties, and lives of the whole Nation, are his RIGHT and PROPERTY, and at his absolute WILL and pleasure for the disposing whereof be neither OVGHT nor can be REQUJRED to render the least ACCOVNT.

In his answer to the Parliaments Remonstrance of May 26. 1642. he avers, that he had the same title [s] to the Town of Hull, which any man hath to his money or lands, and in the same dialect he speakes and writes, OVR Townes, Forts, and Magazines. And doubtlesse if he hath such a property in all the Townes of England, he hath the same property in all the people that he hath in their houses, and therefore he claimes the disposall of their persons by his personall commands, in the same manner, wherein a man commands the use of his money. But theres no clearer Christall glasse, through which every eye may read this principle fairly written in the Kings heart, then his proud claim to the absolute sole command of the whole Militia, therein he insults like a reall Conquerer, at whose feet the Estates, Liberties, and lives of the Nation lye prostrate. IN VS (saith he to the Parliament) and JN VS ONLY is that power to command the Militia [t] placed. And againe, with the authority in execution of the Militia, God [u] hath trusted us solely. And likewise in his letter to Leicestershire, Iune 12. 1642. It belongs (saith be) SOLELY to us to order and governe the Militia of the Kingdome. [w]

And so absolute an intire power doth he plead for, in this Command of the Militia, that at his pleasure he disdaines the advice of the people in Parliament, when the Parliament declared, that his trust with the [21] Militia was to be managed by their advice, [x] and that the Kingdome had betrusted them for that purpose. Can it be beleeved? (saith the King) that the people intended you for our Guardians and Controlers in that trust.

Besides this his single Arbitrary command, of the whole Militia, let his claim be considered to an entire power of treaties of War or peace without consent or advice of Parliament, and to raise men for forraign service at his pleasure; And then it will appeare indisputable, that he esteemes the estates, liberties, persons, and lives of all the people at his own dispose, by this its invincibly evident, that he pretends to such an interest, or propertie in our liberties and lives, that he may at his pleasure rend us from our neerest relations, command us to expend our estates, and hazzard our persons, and yet he professe he owe no ACCOVNT [y] [z] to any but God in the managing of this trust of such vast consequence, and importance, he disavowes the peoples power in their Deputies the Parliament to intermedle either in advising him or taking ACCOMPTS of the discharge of his duty. The people (saith he) are by their oaths uncapable of conferring such a trust upon their representatives. Thus he erects to himself a Throne so high, that the estates, liberties, persons, and lives of all the people, must be his foot-stoole. And least any should conceive that the King intends to be regulated by law, in disposing of all the peoples enjoyments, which he claimes as his property, he hath professedly assumed to himself, the supream indiciall power [a] to declare the sense of the Law: So that in the issue it amounts to the same, that the whole Nation should be at his absolute WILL and pleasure exposed unavoidably, to what rapes, rapines, murthers, and abuses may proceed from him or his Creatures.

The Kings fift beloved principle.

That its essentiall to his absolute dominion and greatnesse to maintaine the government of the Church by Bishops; Qualii pater, talis silius, the infection of this principle is Morbus Hereditarius, it was part of the inheritance that diseended to him from his father. No Bishop, no King, was a principle maxim in his fathers Politicks, and Naturam expellas furca, licet usq; recurret, policie commanded him once to condiscend to the settlement of a Presbyterie for three yeares, but love to tyranny hired his conscience for its advocate, to plead against the demolishing the pillars of Prelacy, their Lordships, lands and Pallaces: [22] its Sacriledge, saith that Advocate very devoutly, to convert the goods of the Church to civill prophane uses.

Now let us search whether under the Armies Proposalls, Jreton have not craftlly hidden these glittering pearles of the Crown, as Rachell hid Labans Idols.

Truly at a superficiall view, the first of these Jewells of the Crown may be discovered. Its the continued voice of the Proposalls.

That all power and authority in this Nation is fundamentally seated in the WILL of the King, his heires and successors.

They proclaime aloud as with a Trumpet, that all power in Courts of Iudicature, and all Officers both military and civill, ought DE IURE REGALI, to be the CREATVRES of his WILL. This is the unanimous voice of the 1, 2, and 3. [b] particular under the first generall proposall. And of the 1, 2, and 3. particulars in the second Proposall, and the third Proposall is but a dependant upon the second. Likewise the voice of the fourth proposall concurres with the former, and the foureteenth and last proposall in order to a peace with the King, and his settlement, is a seale to all the former, and the ninth and eleventh Proposall in effect, or by consequence speakes the same of the sole power of the Kings WILL to abolish Courts of Iudicature, Officers and their powers, that the former doth of its power to constitute them.

To make it evident.

1. Such an earthly omnipotency to create all Officers of power and trust in this Nation, as none can be made or appointed but by his Will is proposed to returne to him and his heires after 10. years. Thus in the second Proposal concerning Military Officers, its proposed that only for ten yeares the representative of all England (who are betrusted with all power [c]) should dispose of the Militia, and then to return to the King, as if that command did properly and peculiarly belong to him. Whats a clearer acknowledgement of the power of the Militia, de iure, to belong to him? then thus, to receive it from him by gift, grant, or lease for ten yeares. And though its added, that after ten yeares, the King that NOW IS, shall not order, dispose, or exercise the Militia without the consent of Parliament. Yet thats but a clearer declaration of his right and interest, because he is by that acknowledged to have the principall, supream power over the Militia, only there shall be a restriction of that power, or an obligation upon him, to admit of the advice of Parliament, and having gained so cleare a confession (should [23] these Proposalls have passed) of his Right to exercise the Militia at pleasure: can a rationall head imagine, that he will suffer the advice of a Parliament, to bound, or limit his will in executing that power, whensoever oportunity, or occasion shall prompt him? especially considering that his Concession of the ten years lease of this power, was during the restraint of his person, and so voyd and null in Law: but however, there wil be a constant occasion of a new Controversie, and Imbruing the Nation againe in blood. This was the late Quarrell, that the King would exercise the Militia [a] without the advice, or consent of Parliament. But further, the power of creating al Military Officers is yet more clearely (if possible) stated in the Kings will; for the Proposals leave his claime to the Militia, and his Right, as its acknowledged by them, to descend to his Heires as an inheritance, and lay not the least obligation upon them, to accept, or admit of the advice, or consent of Parliament, in their exercise of it; and therefore no Question, Commissary Gen. IRETON politiquely inserted his Majesty THAT NOW IS shall not dispose of the Militia without the consent or advise of Parliament. Surely he was observant of the Kings Message sent by Sir John Berclay from Oxborne to Bedford after the Proposalls were sent to him, viz. that he would agree with them provided that they desired nothing that intrenched upon the honour or power of his Posterity, or his owne Conscience, i.e. the abolishing Bishops. The exposition of which is this, Let it be provided, that the Power which he usurped to create Authorityes, & Officers, Military, and Civill at his will, be declared his Right; at least, virtually, and by Consequence, by being suffered to descend as his proper Right, [b] to his Posterity, that so he may in effect, be justified, in drinking up so much innocent Blood; and may with appearance of Justice, when oportunity serves, Wade in Blood again, to re-instate himselfe in a boundlesse power: or at least that his SONNE, whose tender hands are already washed in blood, may be invested with power to revenge his fathers Quarrell. [24] Let this be done and he shall then agree.

And in the same manner the power of disposing all the Civil Officers, is proposed to returne to him after ten yeares; and so likewise that shall descend as a right to his Heires; thus in the fourth [c] Proposall: and the seeming Limitation of that power, by the Parliaments nomination of three persons for any great Office, out of which the King should elect, though its but a shadow of freedome in it selfe, yet its not proposed to extend to the Heires of the King, so that its positively declared to be the Kings Right singly by his absolute will to Create all Officers, Now what can more exactly run parallel, with the Kings prime inslaving principle, then these proposalls? the King contended at first, only for a cleare stating such an absolute power in him, In his answer to the Parliament concerning the Militia, (saith he) we [d] expected that that necessary power should be first invested in us, before we transferre it to other men. And you may observe, that congruent to this, is the Kings late voluntary proffer to the Parliament, to give them the disposing of the Militia during his Life: thereby he should attaine his end, viz. an acknowledgement, that De jure, that power resides in him, and a conveyance of a claime to the pretended Right, to his successors: whereby the people shall be vassalls to their wills.

2. A power of constituting at his pleasure A PARLIAMENT, (where in the supreame Authority resides) is proposed in the third [e] particular of the first proposall: I confesse, there is a shadow of Restriction to the absolutenesse of his will, in constituting a Parliament; Its said thus: the King upon advice of the Councell of State to call a Parliament in the intervalls of Bieniall Parliaments, but what intelligent head discernes not, that the King, who scornd the advice of Parliament, when they declared it his duty to manage his trust by the advice of that [f] Grand Councell, will incomparably more disdaine, any contradiction of his will, by a petty Councel, new constituted? And if it may be supposed, that such a Councell, should not only be such [25] chaste virgins, as to loath the defilements by Court embraces, but also such Noble Heroick Champions, as would make their integrity their shield, and be fearlesse of those sharpest Arrows, the Kingly frowns; and so should dare to enter the lists, to contest with the King, should all this (I say) be supposed, yet can it rationally be imagined, that the Interest of such an unknowne, unheard of Councell, in the Peoples hearts, should be able to parallel the Kings Interest? should such a Councell, issue forth their Orders, to contradict the Kings writs for elections; would the influence of such Orders from an unheard of Authority, countervaile the influence of the Kings writ upon the People? neither doth the Proposals invest that new potentiall Councel, with such a power to oppose the Kings WILL in that particular, its not said that he shall not call a Parliament without the advice of that Councell, so that his WILL is in effect allowed by this Proposall to give being to a Parliament.

And by this Proposall, When so ever the Parliament shall be disolved, (which I suppose by the concurrence of the Kings will, and their own, shall be everlasting, if he be once invested with such power as is proposed; for there can never be a Parliament more obliged, and engaged to serve the Kings corrupt ends, then this will be, upon his re-establishment:) yet (I say) should it be disolved, the King might call a Parliament within a Month, to try at least, whether they would contribute more to the estating an absolute boundless power in his will, and abolish those toothlesse, uselesse Lawes, that were small bounds and limits to its exorbitancy.

And in case men of worth, and integrity, faithfull to God and their Country, should be elected, then he may disolve them in the imediate succeeding day or houre, to the manifestation of their faithfullnesse, and there is no restriction in this Proposall to the Kings will, from issuing out new writs for another election, and another after that also, before a Bieniall Parliament be called, and then may the interest of him and his creatures, in the [26] Cities and Country, be improved with more diligence against that new election; so that by investing the Kings will with a power to give a being to Parliaments, Ad libitum, if all circumstances be duely weighed, as to his influence upon the People in Elections, and to his power of disolving them at pleasure; to his superiority to them, by his Negative voice, and that all subordinate authorities, powers, and offices, may be erected, or abolished, made or displaced, without controversie, by his concurrence with them: In the result of all, it amounts to little lesse, then the making his will the originall of all Power and Authority in this Nation.

But that which appeares to intrench upon the Royall Prerogative, or that Principle, that the Kings will is the originall of all power, is the provision made in the 1, and 2. part of the first Proposall, for certain Bieniall Parliaments, and their certain sitting 120. dayes; hereby it seemes the being of some Parliaments shall not have their foundation in the Kings will, or depend upon it for their continuance, as those other (as they are called) extraordinary Parliaments: But whatsoever eye shall pierce through the bowels of these Proposals, shall neither see such absolute certainty for these Bieniall Parliaments, nor such independency of them, for their being, or power, upon the Kings will, as their superficies pretend.

First, the provision for the certainty of their being, is the same that was in the Act for trieniall Parliaments; and according to that Act, the Parliament is to be summoned, (or to have its being) primarily from the Kings Writ, the tenure of which is this, Quoddam Parliamentum nostrum teneri, &c. Nos ordinavimus We have decreed a Parliament of ours to be holden, &c. i.e. Its our will that a Parliament be holden, &c. Now how neare a compliance there is in this, with the Kings principle, that Parliaments have their being from his [g WILL, the most purblind eye may discern: And though the King be obliged to issue out such Writs, yet in case of his default the same Writs are to be issued [27] out by the Chancellour, or Lord Keeper, then by twelve Peeres, &c. but how uncertain the being of these Bieniall Parliaments may be, notwithstanding all such provision for the issuing forth Writs for elections, let Englands sad experience testifie; while Parliaments were so long discontinued by the King; that it was a crime to name them: there were Lawes and Statutes, for the Kings calling a Parliament at least once every year; [h but alas! such Lawes as require personall observance or obedience from Kings, are uselesse ciphers, while Kings are permitted to claime a superiority to the Law, or an exemption from the censures or penalties annexed. And though inferiour officers are appointed to issue forth Writs for Elections, in case the King neglects, yet that is no security, Regis ad exemplum totus componitur orbis, when King James in an humour to try his Nobles, at noone-tide vowed he discerned a Star shining bright a little distance from the Sun, most of the Nobles vowed they saw it: Dionisius courtiers lickt his spittle, vowing it to be sweeter then Nectar and Ambrosia: who can imagine that the Kings creatures, as the Lord Keeper, Lord Chancellour, or the Peeres, will beare the Kings direfull frownes, for the Peoples sake? That they will issue forth Writs in the Kings name, when his pleasure shall be signifyed to them to the contrary: yea, suppose a miracle, that vertue and faithfulnesse, should once bee exalted to such Dignity to be Lord Keeper, Lord Chancellor, &c. so that there should be an attempt, to issue forth Writs for elections in the Kings name; who should secure those Officers, from the impoysoned arrowes of the Kings indignation, untill elections were made, and the Parliament assembled? who knowes not that the Forces in pay, will be at the Kings beck, when ever he be warme in his Throne? Did not many Regiments at Ware cry out, for the King and Sir Thomas, for the King and Sir Thomas? and shal not the King then over-awe, or crush, every such faithfull Officer? And when every gallant Officer in his various Orbe, be slain, or foyled, in his encounter with the Kings fury, [28] where will probably the first Champion be found amongst the People? to invite the People together, in despight of the Kings power or wrath to make their elections.

Indeed its beyond controversie (Consideratis considerandis) that there is no possible provision for an absolute certainty of the being of Parliaments, while the People shall depend upon Writs or Warrants for elections; neither can I imagine what shadow of sound reason can be rendred, for the least use, much lesse necessity of such Writs or Warrants. The day of the Parliments meeting shall be certain, and why should not one certain day be prefixed, whereupon all the People might meet on course in their several divisions to elect the Members? Parliaments proper use is to preserve the Peoples freedome, from the incroachment of the King and his creatures; who therefore will be so faithful to the People to provide for Parliaments, as they will be to themselves and their owne freedome?

But though through the obscurity of that Proposall, every eye should not discerne a perfect union between the Kings enslaving principle, and these two proposalls, which beares the highest pretence to our freedomes, yet the correspondency between them is grossely palpable: the second particular Proposall clearly offers, that the being of every Parliament, for halfe the time of its sitting, should depend totally upon his absolute will: after 120. dayes, saith the proposall, Parliaments to be adiournable or dissolvable by the King; i.e. at his will and pleasure: herein, both the established Law and the foundations of freedome are overturnd; this Proposal constitutes the King the supreame judge of the Peoples safety, which in the controversie about Ship money, was contradicted by Parliament, and partly upon that consideration, those Judges that allowed it were severely censured: and its more expresly declared by Parliament, that the King is not supreame Judge [i] of the peoples safety, in their reply to the kings answer to their declaration of May 26. 1642. and by Law Parliaments ought to sit untill every petition of the [29] people be duely answered, and a publike demand by Proclamation in the Parliament, and within the pallace of the Parliament, whether any hath delivered a petition and hath not received answer: so that in effect, the people are the supreame Judge of their own freedome and security, and may only continue or dissolve the Parliament, or punctually prefixe the time of their sitting, which through the danger of mens corruption by long continuance in so high a trust, is of extreame necessity: I shall omit here (for brevity sake) to discover how wide a doore of opportunity this Proposall sets open to the king, to obtain a faction in Parliament, for his corrupt interest, and then to continue it, to enslave the People by a Law: and this advantage to the King would want no evidence; if the Parliaments dependance upon him, by reason of his negative voice in the whole time of their sitting be considered; and to that, adde their dependance upon him for their very being, halfe the time: It is well known, Occasio facit Furem, it is oportunity makes a Thiefe and a Tyrant. [k]

But further, as those Proposals cleare not Parliaments from a dependance upon the Kings will for their very being: so much lesse do they evidence that the power of Parliaments is not derived originally from the Kings will; yea rather they secretly establish the Kings maxime, that his will is the fountain of their Power: This highest treachery against the freedomes of England, lyes closely couched under their approbation of calling Parliaments by the Kings accustomed Writs, according to the Act for trieniall [l Parliaments; the forme of the Writ is this, Quia de advisamento & assensu consilii nostri pro quæbusdam arduis & urgentibus negotiis nos, &c. quoddam Parliamentum nostrum, &c. teneri ordinavimus. Herein the King prescribes the Parliaments power, confining it only to advise, and limiting that advice, Ad quædam ardua, to some hard things; and so the whole power of Parliaments seem to be received from the Kings will, [m as matter of trust; and Com. Gen. Ireton, when he framed the Proposals, [30] was well acquainted, that the King by vertue of this Writ claimed the power of Parliaments to be matter of trust, conveighed from him, or his will. Saith he, what the extent of their Commission and [n trust is, nothing can better teach them, then the Writ whereby they are met; they are our Counsellors, and not in all things, but in some, De quibusdam arduis, in some difficult matters: and he produces a president of a miscarriage of Queen Elizabeths committing one Wentworth, a Member of Parliament to the Tower, for proposing that they might advise her in a matter that shee thought they had nothing to do to medle in; thus the Parliament is claimed to be the trustees of the King, and their power so to have its foundation [* in his will, that he may censure them at pleasure, if they shall advise him in any thing not consonant to his will: all this was clearly known by Ireton, and objected to him urgently, when his Proposals were upon the Forge, and yet there is not the least exception taken against the calling Parliaments by those Writs: And the king having so candidly declared this enslaving maxime, and so ingeniously expounded his own Writ, and after so hot and bloody a contest about the extent of the Parliaments power, and trust, if that forme of Writs for elections be now established, how can the truth of the kings turkish principle, that his will is the originall of Parliaments power, be more clearely attested? and what would such an agreement with the king, amount to lesse, then boring of our eares for perpetuall vassallage to his will, or lust?

3. To demonstrate if possible yet more clearely, that these Proposals do establish the kings first enslaving principle: It is to be observed, that whatsoever power for present is estated in [31] Parliament by the proposals either to dispose of the Militia make warre or peace about the calling or dissolving Parliaments, disposiing Officers Military or Civil &c. is declared in the 14. proposal to be a Limitation to the exercise of the Regal power; here by its insinuated, or rather clearly declared, that all that power now proposed in the things aforesaid, to be exercised by the Parliament ought de jure to be exercised by the King; so that the right to the Militia, to the disposall of offices, calling, and dissolving of Parliaments, is stated in him; and consequently, the King contended only for his right, and must be justified from all the blood, Lamentations, and Woes, that are the effects and issues of the late warre, and so the price of our blood, shall be betrayed into our enemies hands, and all shall be engaged to adore his most sacred WILL, as of right their supream Lord, and Law-giver; and let no man question the Kings unwearied uncessant dilligence, to recover his declared right.

4. If evidence may super-abound take notice that all the Limitations to the exercise of the regall power, are proposed to be received as Acts of his GRACE by a Le-roy Le-veut, the conquered enemy must be petitioned to grant, and confirme the price of the blood of thousands: and an act drawn in this form. YOVR MAJESTIES LOYAL SVBJECTS who have subdued your Maiesty by their sword, whose prisoner now you are, now assembled in Parliament, do HVMBLY PRAY, [o] that it be inacted, &c. spectatum admissi risum teneatis amici? I might still further add, that by these proposalls, the abolition of all Courts, or offices, which have flayed of the peoples skins, and even eaten their flesh, The abolition (I say) of those, is to depend at present upon the Kings WILL, and PLEASVRE. The King being allowed a Negative voice in the Proposalls (as shall appeare) not the least of the of the multitude of the Oppressive Courts, and Offices, that are even Canibals to the people, can be abolished, but by that WILL of his, which is totally intent upon creating oppressions, and estating himself in an absolute, unlimited, dominion, that at pleasure he may devoure and destroy his opposers with a word. But especially let these foure distinct notes be conioyned in one; let the return after ten years of an Omnipotency to his WILL to creat all Officers both Military and Civill: the acknowledgement (in effect) of the BEING and POWER of Parliaments to depend upon his WILL: the insinuation, that the chiefe powers exercised by the supreame Court of Parliament, is only a limitation to the exercise of a regall power, not a declaration of the nature of a regall power: and the accepting of all such limitations, as acts of favour and grace from his WILL. Let all these I say [32] be considered, and let every impartiall Iudgement, passe his sentence upon the question, whether IRETONS and CROMWELS (or as they are called the Armies) PROPOSALLS, doe not confirme that foundation of tyranny, the Kings first enslaving principle? viz. that all power and authority in this nation, is fundamentally seated in the Kings WILL.

And is this the freedom they ingaged to plead for? O monstrum horrendum informe, &c. is this the fruit of those fairest blossomes that ever sprouted forth in an English June? Are these the silver streames of justice, that the thirsty, perishing people longed after? but to proceed. [†]

Is not the Kings 2 inslaving principle as visibly confirmed by the Proposalls as the first? cannot every humble eye read in them, that the Kings absolute WILL is supreame, or a law paramount to all the determinations of Parliament. Let the seventh particular in the full proposall, be compared with the fourteenth proposall. In the seventh particular its proposed, that the orders, and rules set down by the Commons in Parliament, for the freedome of election of their Members, and the right constitution of their own house be as lawes, thus restraining the Kings negative voice, only in that one particular.

And in the fourteenth proposall, its expresly desired, that here might be no further limitation to the EXERCISE of the regall power, then according to the foregoing particulars. And the King esteemes his usurpation of that Negative voice (though contrary to his oath) one of the fairest flowers in the Garland of his regall rights. So that in this, Cromwell and Ireton come little short of the King himself, in pleading for this his second enslaving principle.