THE LEVELLER TRACTS PROJECT

"THE SPARKS OF FREEDOM IN THE MINDS OF MEN":

Three Tracts by John Warr (1648-1649)

|

|

|

[Created: 23 January, 2025]

[Updated: 27 May, 2025] |

Source

, "The Sparks of Freedom in the Minds of Men": Three Tracts by John Warr (1648-1649). Edited by David M. Hart (The Pittwater Free Press, 2025).http://davidmhart.com/liberty/LevellerTracts/T123.html

John Warr, "The Sparks of Freedom in the Minds of Men": Three Tracts by John Warr (1648-1649). Edited by David M. Hart (The Pittwater Free Press, 2025).

This anthology consists of three tracts published by John Warr in 1648 and 1649:

- John Warr, Administrations Civil and Spiritual in Two Treatises. The First Entitled The Dispute betwixt Equity and Form. The Other The Dispute betwixt Form and Power. (London: Giles Calvert, 1648).

- John Warr, The Priviledges of the People, or Principles of Common Right and Freedome asserted, briefely laid open and asserted in two Chapters (London: Giles Calvert, 1649). Dated 5 February, 1649.

- John Warr, The Corruption and Deficiency of the Lawes of England soberly discovered: or, Liberty working up to its just height (London: Giles Calvert, 1649). Dated 11 June, 1649.

Note:

- This is part of a collection of Leveller Tracts and Pamphlets: general information - full list.

- The page numbers refer to the page numbering in the original pamphlet. Sometimes page numbers were missing or there were duplicates. On many occasions the text in the margin notes is unreadable as a result of poor scanning of the original.

Table of Contents

- Administrations Civil and Spiritual in Two Treatises. The First Entitled The Dispute betwixt Equity and Form. The Other The Dispute betwixt Form and Power (1648)

- The Priviledges of the People, or Principles of Common Right and Freedome asserted, briefely laid open and asserted in two Chapters (5 February, 1649)

- The Corruption and Deficiency of the Lawes of England soberly discovered: or, Liberty working up to its just height (11 June, 1649)

- Chap. I. Containing the just measure of all good Lawes, in their Originall, Rule, and end: Together with a reflexion (by way of Antithesis) upon unjust Lawes.

- Chap. II. The Failers of our English Lawes, in their Originall, Rule, and End.

- Chap. III. Of the necessity of the Reformation of the Laws of England, together with the excellency (and yet difficulty) of the worke.

- Chap. IV. Of the corrupt Jnterest of Lawyers in the Common-wealth of England.

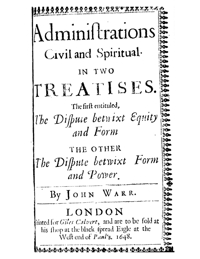

John Warr, Administrations Civil and Spiritual in Two Treatises (1648)

Full Title:

John Warr, Administrations Civil and Spiritual in Two Treatises. The First Entitled The Dispute betwixt Equity and Form. The Other The Dispute betwixt Form and Power. (London: Giles Calvert, 1648).

Title ID: T.296 [1648.00] John Warr, Administrations Civil and Spiritual (1648 no month given).

Estimated date of publication: 1648 - no month given.

Thomason Tracts Catalog information: Not listed in Thomason Tracts.

Table of Contents

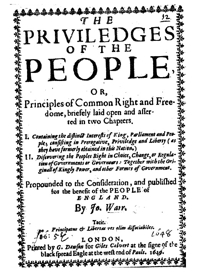

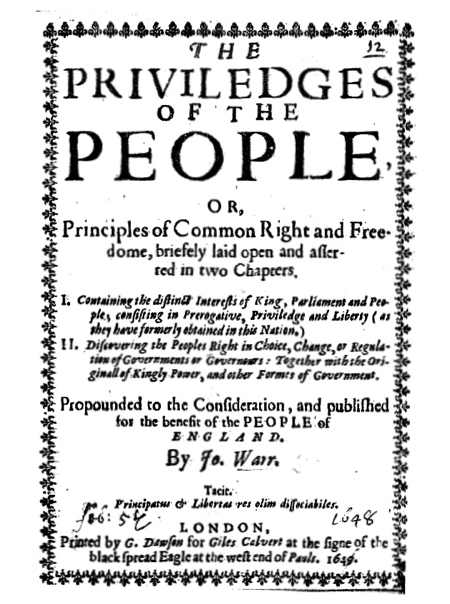

John Warr, The Priviledges of the People, or Principles of Common Right and Freedome (5 February, 1649)

Full Title

John Warr, The Priviledges of the People, or Principles of Common Right and Freedome asserted, briefely laid open and asserted in two Chapters.

I. Containing the distinct Interests of King, Parliament and People; consisting in Prerogative, Priviledge and Liberty (as they have formerly obtained in this Nation.)

II. Discovering the Peoples Right in Choice, Change, or Regulation of Governments or Governours: Together with the Originall of Kingly Power, and other Formes of Government.

Propounded to the Consideration, and published for the benefit of the PEOPLE of ENGLAND. By Jo. Warr.

Tacit. Principatus & Libertas res olim dissociabiles.

LONDON, Printed by G. Dawson for Giles Calvert at the signe of the black spread Eagle at the west end of Pauls. 1649.

Title ID: T.180 [1649.02.05] John Warr, The Priviledges of the People, or Principles of Common Right and Freedome (5 February, 1649).

Estimated Date of Publication: 5 February, 1649.

Thomason Tracts Catalogue Information: TT1, p. 721; Thomason E. 541. (12.)

Table of Contents

- CHAP. I. Discovering the distinct Interests of King, Parliament, and People, p. 1.

- Sect. I. Of Prerogative or Kingly Interest.

- Sect. II. Of Priviledge, or Parliament Interest.

- SECT. 3. Of Liberty, or the Peoples Interest.

- CHAP. II. Of the Peoples Right in the Choyce, Change, or Regulation of Government, together with the originall of Kingly Power, and other Formes of Government., p. 8.

- Englished thus,

[1]

CHAP. I. Discovering the distinct Interests of King, Parliament, and People.↩

Sect. I. Of Prerogative or Kingly Interest.

THe Interest of the King having advanced it self into a Principle of Distinction, Seperation, and Superiority above the Interest of the People, is called Prerogative or Kingly greatnes; which is a Tuber or exuberance growing out from the stock of the Common wealth, partly through the weaknes and indulgence of People to their Kings and Rulers, (which hath been most eminent in the English Nation) and partly through the ambition and lust of Princes themselves, who not considering their greatnesse as in a principle of union with the People, in a way of tendencie and subserviencie to the Peoples good, have heightned themselves beyond their due bounds, and framed a distinct Interest of their own, pretendedly Supream? To advance this Interest, Kings and Princes have politiques, and Principles of their own, and certain State-maxims, whereby they soare a loft, and walk in a distinct way of opposition to the Rights and Freedomes of the People; all which you may see in Machiavils Prince.

Hence it is that Kings have been always jealous of the people, and have held forth their own Interest, as a Mystery or Riddle, not to be pried into by ordinary understandings: And [2] the Proselytes of this corrupt and tyrannous Interest have alwayes served it up, as a Sacred thing, a thing as much above our reach, as it is truly and indeed against our Freedomes.

So that Ignorance being the Mother and Nurse of Bondage, such Principles have been watchfully observed, as have ushered in any Light, or discovery of the corruptnesse of the Prerogative Interest; hence is it that the Expositions of Pareus upon Rom. 13. were censured and condemned by the Court Party, as giving too much Liberty to Subjects, to resist their Kings: and the Genevah notes upon Exod. 1. v. 17. were disliked by King James, because they countenanced the Midwives disobedience to the King; not, but that the thing commanded was unlawfull, but it was interpreted to open too great a gap to the ruine of this Interest, of which wee now speak.

And yet some have not been wanting, who in times of greatest hazard have adventured their own Freedomes as a Sacrifice to the Publike; and have made forth discoveries of the corruption & rottenes of this oppressive Prerogative Interest, upon conscientious grounds of Publike Freedome. Though this hath been censured by the Potencie of that Interest which it did oppose, as an offence no lesse then piacular; And their Persons loaded with calumnies of all sorts, as being a faction or Party of Levellers, as King James cals some in his Star-chamber Speech.

And though we may possibly suppose that the corruption of this Interest, may be in some measure discovered to those that use it, and that Kings themselves may suck in some principles of common Right and Freedome; some glimmerings whereof, seem to sparkle in the writings of King James, yet their judgements are so over clouded by their Interests, that they doe not onely blinde themselves, but hoodwink others, and all to establish that, which God himself purposes to destroy and overthrow.

For when Principles of light and knowledge shall be advanced amongst men, they shall then scorn to be subject to the corrupt Wils and Lusts of others: they shall know no Policie, but integritie and honestie; False interests shall tumble down [3] truth and righteousnesse take place, and Prerogative be worried, as an Enemy to Freedome.

And if this were made out to Princes themselves, they would not onely prophane their own mysteries, and make them common, but sacrifice their greatnesse to the light of Truth, (which hath so often sacrificed Truth to it self) and study which way to advance the Peoples Interest, though in opposition to their own. And if this self-denying spirit were in them, and the power of Truth, the rough way of worldly force and spoile would be prevented, and the work rendered more easie to themselves and others.

Sect. II. Of Priviledge, or Parliament Interest.

IF the voice of Common Right or Freedome could be heard amongst Men, the world would not be so deeply engaged in factions, and distinct Parties, as they are; but this is the misery, The mindes of men being prejudiced with corrupt Interests of one sort or other, and pertinaciously adhearing to them, doe contribute their utmost assistance to maintain them, partly through the inbred corruption within men, and partly through those provocations which (in the heat of contest) they meet with, from Interests which are at variance with their own (for even truth itself will justle its adversarie in a narrow passe) Hence it is that some are said to be for the King, some for the Parliament, some for the Army.

But is Truth divided? Is there not one common principle of Freedome, which (if discovered) would reconcile all; Tis true this Principle may be weakly and imperfectly managed by the Children thereof, but the miscarriage (whether reall or supposed) is not to be charged upon the Principle it self; And yet this is the practise of corrupt men, who take advantage from common frailties in the prosecution of just things, to cry down the things Themselves, and so to strengthen their adhesion to their own Interests, though never so corrupt.

The purest civill interest, is the Peoples Freedome, which [4] may be crushed by Priviledge as well as Prerogative; For Prerogative and Priviledge (in its usuall adoeptation) are neer of kin; and it is possible for a Societic to exercise Tyrannie as well as a single Person. What hath been spoken of Prerogative, may be affirmed of Priviledge, the Impe thereof; For Man being naturally of an aspiring temper, mannages all advantages to set up himself, and to this the Peoples election is a faire temptation, and though the gentlenesse of the phrase doth word the Parliament, To serve for their Country, yet tis sometimes in the same kinde of oratory, as the Pope is the servant of the Church, whilest he exerciseth rule and domination over it.

Priviledge hath formed it self into a distinct Interest, as well as Prerogative, and hath forgot its originall and fire, thinks it self compleat without superior or equall: Thus hath it broke off it self, from its stock, and like a succour draws nourishment away from the true branches; so that, where Prerogative and Priviledge are in a thriving posture, the Freedomes of that People are underlings and leane as being crop’d on both sides.

When things doe continue in their proper place and order, they stand in God, and are usefull to those ends for which he hath appointed them; but when they warpe, they turn aside from God; and when they leave their station, and would be of themselves (as Lucifer) they fall down into Hell and a condition of darknesse; The way to advance Priviledge is to keep it within its due bounds.

Tis true, somethings doe naturally ascend, but tis to their own place and Center, and when they are there, they are cloathed with Majestie and glory. Every thing is beautifull in its place and season: There is a beauty in Priviledge (thus considered) as well as in Libertie.

To ascend beyond due and measured bounds, is no way honourable but monstrous, as if the Feet should grow out of the Thighs, or the Hands upon top of the Head; this is a disorder and confusion, and thus Pride is the wombe of darknesse, which may be verified in Priviledge as well as Prerogative.

Tis true, Priviledge hath a stronger plea, as being founded [5] upon Election and Consent, but this will not justifie the Abuse thereof: for when Priviledge soares high, the people sometimes follow it, either through ignorance of its Nature or bounds, or else that they may not lose the benefit of that, which is truly so called, and is usefull in its place. For as Water ascends for the continuation of it selfe, so the interest between Parliament and people, must not bee discontinued. And yet this motion on the peoples part is violent, not naturall: for Liberty should not ascend to Priviledge, but Previledge should stoop downe to Liberty, as its Center and Rest.

Priviledges may sometimes mount so high, that Liberty cannot onely not follow, but is endangered by it. In this case Priviledge discontinues it selfe, and Liberty casts off homage and subjection thereto, such Priviledge is to be lop’d off as a burden to Freedome.

True priviledge of Parliament is this, in a principle of Union with the peoples Right, an Immunity and Freedome to mind just things, and to prosecute impartiall grounds of righteousnesse and Truth, other priviledges may be pared away, as bearing no proportion with their End, but this shall continue as subservient unto Freedome.

SECT. 3. Of Liberty, or the Peoples Interest.

IN every Common-wealth the Interest of the People is the True and Proper-Interest of that Common-wealth; other Interests have advanced themselves, pretendedly to exalt This, and yet being once gotten into the Throne of Rule, they labour nothing lesse, or rather indeed they bend their utmost endeavour to overthrow It.

Prerogative and Priviledge Interests, (as formerly explained in their corrupt notions) are altogether inconsistent with True Freedome: Hence it is that there is an irreconcileable contest between Them, which will never cease, till either Prerogative and Priviledge be swallowed up in Freedome, [6] or Liberty it selfe be led caprive by Prerogative. He which hath the worst Cause may sometimes have the best Successe, (for Time and Chance happens to all) and thus Liberty may be worsted by Priviledge, as having lesse specious advantages in the Flesh. For true Freedome is in the Mind, and its Proselytes are but few. Most men give up themselves to the Idoll-Interests of Prerogative and Priviledge, as being more taking with flesh and blood.

And when Liberty is once put to the rout, it is not easie to rally again, or to redeem it selfe, for the darkest Dungeon is its Prison, ’tis chained with oathes and servile bonds, yea and the strong bolts of human. Lawes doe keep it in subjection. Thus are all things made sure, with a Grave-stone, a Seale, and a Watch, and oppression rides in triumph upon the backes of the people.

All imaginary gaps for the re-entrance of Freedome, being thus stop’d up, it were impossible for it to arise from the dead, or to recover its true and proper state, if God himselfe did not appeare, and laugh the counsels of men to scorn, yea and open the Iron gates, and knock off the bolts, and lead forth Freedome to open view, as the Angel did Peter.

In this designe God co-operates with Man, and makes him instrumentall in the work, by clearing his principles, and stirring up his spirit. There are some sparkes of Freedome in the mindes of most, which ordinarily lye deep, and are covered in the Darke, as a spark in the ashes. This spark is the image of God in the mind, which is indeed the Man, (for the divine Image makes the Man.) This Man is hid in most persons, onely the Tyrant, the Beast, or the slavish principle appeares, and the whole bulk is hurried about by the motion of that principle, and the Man within us swimmes with the stream.

But God favours all weak things, and hath a speciall regard to tender ones, when under darknesse and oppression. And in order hereunto he layes the Axe to the root of the Tree, and strengthers our weake principle, he layes the foundation of Freedome within us, and so proceeds to blow up the fire, till the roome be too hot for unrighteousnesse and wrong.

Thus Tyranny being driven out of the Spirit, or Mind (its [7] surest hold, its Metropolis, or Citie of Refuge) ’tis hunted too and fro like a beast of pray. Neither is this a rare thing, but according to the usuall proceedings of God in the World, who spoyles the Spoyler, and punishes oppression in Methodes of its owne, that Men may see and admire his Greatnesse and Power.

Be wise now therefore, O yee Kings, be instructed O yee Iudges of the earth. Most of your designes are founded upon Selfe, and are against the Lord you establish your selves and your own greatnesse; your hands are against every one, and every ones hands against you, you have led Liberty captive. ’Tis the voyce of God to you, Let my oppressed goe free. Some of you have allowed a Mock-freedom to Liberty, your prisoner, when you could keep it close no longer, you have sent it abroad, but with prison garments, some badges of Slavery have remained upon it; no portion of Freedome hath been wrung from you, but through exigence or necessity. Thus have you demeaned your selves, as if the people had been made for you, not you for the people. For these things doth God arise, and the day of your visitation is come.

For why? ’Tis not possible for a people to be too free. True Liberty hath a cleare sight Principle or Rule, and a large compasse, a spacious walk, ’tis not limited or circumscribed, but by the bounds of righteousnesse. Liberty is the daughter of Truth and Righteousnesse, and hath Light within it, as the Sun, other lights are borrowed from it. Tyranny is as a Clog, or an Eclipse to Freedome. God sees good that Liberty should recover but by degrees, that so the world may be ballanced with light and knowledge, according to the advance thereof, and be more considerate in her actings. The deeper the Foundation, the surer the Work, Liberty in its full appearance would darken the eye newly recovered from blindnesse, the principles thereof are infused to us by degrees, that our heads may be strengthened (not overturned) by its Influence.

[8]

CHAP. II. Of the Peoples Right in the Choyce, Change, or Regulation of Government, together with the originall of Kingly Power, and other Formes of Government.↩

ALL Governments being fundamentally (as to Man) seated in the People, which Maxime is sufficiently spoken to of late. The inhabitants of severall Countries, for the equall distribution of Justice to the whole, have voluntarily submitted to severall Administrations and Formes of Government, either under one or many Rulers: so that Election, or Consent (setting aside Titles by Conquest) are the proper source and Fountain of all Just Governments. Hence it is that the power of Rulers is but Ministeriall, and in order to the peoples good, which hath given occasion to that known Maxime, That the safty of the people is the supream Law.

From hence wee may see the Reason, why some Governments are more or lesse Free, viz. according to the prudence or neglect of Auncestors in bargaining with the Princes, and setting limits to their Power. Some have (as it were) given up themselves to the Wils of their Princes, and out of confidence of their integritie have left them to themselves, not considering, that just men are liable to temptations, when they are in place and power; which if it were possible for them to avoid, yet Justice is not hereditary, nor goes by discent. Some Nations having been pinched with this inconvenience, have afterwards set Bounds and Lawes to their Rulers, according as Tully doth excellently describe it. Lib. 2. de offic. Eadem constituendarum legum fuit causa, quæ Regum, Jus enim semper quesitum est aquabile, neque aliter esset Jus, id si ab uno [9] just, & bono viro consequebantur, eo comenti, cum id minus contingeret, Leges sunt inventæ, quæ cum omnibus temper una & eadem voce loquerentur.

Englished thus,

There is the same reason for Laws, as there was for Kings, for People have alwayes sought after Right, or an equall, distribution of things, which if they did obtain from one just and good man, they were content therewith; but when they failed thereof, Laws were found out, which spake one and the same thing to all men.

Those Nations which have been most strict in prescribing such Rules, are most Free, unlesse in processe of time, through the oscitancie of the people, Princes have trampled upon their bounds, and made them common; and in this case, as good none at all, as not observed.

Though then Governments have been diversifyed according to the different tempers and apprehensions of their Founders, the People; yet the Rise of them all, is One and the same: so that what Tully affirmes of the originall of Monarchy, or Kingly Government, may be said of all the rest, his words are these, lib. 2. de Offic. Apud majores nostros fruenda justitiæ causa videntur olim bene morati Reges constituti: nam cum premerentur olim multitudo ab iis qui majores opes habebant, ad unum aliquem confugiebant virtutem præstantem, qui cum prohiberet injuria tenuiores acquitate constituenda, summos cum inimis pari jure retinebat. The effect of which in English is this, Our Ancestors first appointed Kings for the administration of justice: For when the multitude was oppressed by great and mighty men, they presently addressed themselves to some one eminent and vertuous man, who defended the poore from wrong, and kept both poor and rich within the bounds of Equity. An instance of this kinde wee have in Herod: Clio, where the Medes revolting from the Assyrians, chose one Deioces for their King, a man of supposed strictnesse and Equity in preventing disorders and abuses [10] amongst them. But this remedy in time proved as bad as the disease so that people were enforced to seek protection under severall Rulers, which they missed under One. Hence it came to passe that the Romans banished their King and his Government together, and submitted themselves to another Forme.

But at first they which subject themselves to the government of One, may by the same reason submit to many, which is Aristocracie, or may alter their government from one Form to another: For they that choose may change, provided it bee upon just and valuable grounds. Famous was the dispute had before Octavius Cæsar by two of his Favourites and Councellors, about continuance or change of Monarchy, of which you may read in Dion. lib. 52. The story is this, When Octavius Cæsar had by the Armes and successes of his predecessors and his own, reduced the world to peace, and made a compleat conquest of the great known part thereof, hee tooke counsell with Agrippa and Mecænas, two of his intimate friends, whether he should maintaine the Empire and Monarchy in his own hands, or resigne it to the Senate and people of Rome; Agrippa makes an eloquent Oration against Monarchy, perswading him to surrender up the Government into the hands of the Senate. On the other side, Mecænas perswades the contrary, and pleads for Monarchy, whose counsell was followed by Cæsar, yet so, as that Agrippa was still honorably entertained and respected by him. From which Story we may observe two things.

1. That Anti-monarchicalnes is no crime at all, but a difference in judgement about an Externall Forme of Civill government: Yea great Statesmen (such as Agrippa) have given in their judgements freely against Monarchical government, as Agrippa here did.

2. That to perswade and endeavour the alteration of Governments from one form to another, hath been the subject of the discourse and action of wisemen, as we see here in Agrippa.

And though there may be a beauty in Monarchy, (duely circumscribed) as well as in other forms of Government, yet such [11] cases may sometimes fall out, when Reason and Judgement may not onely call for, but enforce a change; A provocation it must be of grand and fundamentall importance, which if it cannot be otherwise or not so conveniently redressed, may undergoe this kinde of cure; which in cases of extremity hath been practised by Nations.

Smaller inconveniencies may be redressed without the abolition of a form, viz. by prescribing limits to those Rulers, who have abused their Power, which under pain of guilt they may not exceed; For the whole body of the People is above their Ruler, whether one or more.

Not to spend much time herein, I shal conclude this with the argument of the Bishop of Burgen in the Councel of Basil (which was in the reign of our Henry the 6th) where disputing against the authority of the Pope above Councels, he urgeth this argument, that as Kingdoms are and ought to be above Kings, so is a Councel above a Pope. So that former ages have had some light, as touching the Office and duty of a chiefe Ruler or King and would have been able to descry the flattery of those, who ascribe so much Majestie and Sacrednesse either to Man, or Men.

For are not Rulers themselves under a Law? are they not accountable for what they do? Are they not subject to frailties like other men? Are we not all derived from one common Stock? Is not every man born free? when wee ascribe so much to Man, wee detract from the praise and glory of God.

True Majesty is in the spirit and consists in the Divine Image of God in the minde, which the Princes of the World comming short off, have supplyed its defect with outward badges of Fleshly honour; which are but Empty shews and carnall appearances, when void of the substance.

But as weake as they are, they have dazled our eyes, through the darknesse which is in us, when we our selves shall be raised up to an inward glory, we shall then be able to judge of that Majesty and Glory, which rests upon another.

FINIS.

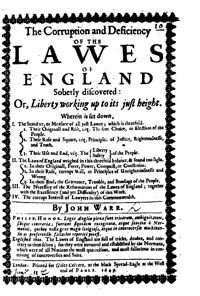

John Warr, The Corruption and Deficiency of the Lawes of England (11 June, 1649)

Full Title:

John Warr, The Corruption and Deficiency of the Lawes of England soberly discovered: or, Liberty working up to its just height. Wherein is set down,

I. The Standart, or Measure of all just Lawes; which is threefold.

- Their Originall and Rise, viz. The free Choice, or Election of the People.

- Their Rule and Square, viz. Principle; of Justice, Righteousnesse, and Truth.

- Their Use and End, viz. the Liberty/Safety of the People.

II. The Laws of England weighed in this threefold balance, & found too light.

- In their Originall, Force, Power, Conquest, or Constraint.

- In their Rule, corrupt Will, or Principles of Unrighteousnesse and Wrong.

- In their End, the Grievance, Trouble, and Bondage of the People.

III. The Necessity of the Reformation of the Lawes of England; together with the Excellency (and yet Difficulty) of this Work.

IV. The corrupt Interest of Lawyers in this Commonwealth.

By John Warr.

Philip Honor. Leges Angliæ plenæ sunt tricarum, ambiguitatum, sibique contrariæ; fuerunt siquidem excogitatæ, atque sancitæ à Normannis, quibus nulla gens magis litigiosa, atque in controversiis machinandis ac proferendis fallacior reperiri potest.

Englished thus. The Lawes of England are full of tricks, doubts, and contrary to themselves; for they were invented and established by the Normans, which were of all the Nations the most quarrelsome, and most fallacious in contriving of controversies and Suits.

London: Printed for Giles Calvert, at the black Spread-Eagle at the West end of Pauls. 1649.

Title ID: T.198 [1649.06.11] John Warr, The Corruption and Deficiency of the Lawes of England (11 June, 1649).

Estimated date of publication: 11 June, 1649.

Thomason Tracts Catalog information: TT1, p. 750; Thomason E. 559. (10.)

Table of Contents

- Chap. I. Containing the just measure of all good Lawes, in their Originall, Rule, and end: Together with a reflexion (by way of Antithesis) upon unjust Lawes.

- Chap. II. The Failers of our English Lawes, in their Originall, Rule, and End.

- Chap. III. Of the necessity of the Reformation of the Laws of England, together with the excellency (and yet difficulty) of the worke.

- Chap. IV. Of the corrupt Jnterest of Lawyers in the Common-wealth of England.

[1]

Chap. I. Containing the just measure of all good Lawes, in their Originall, Rule, and end: Together with a reflexion (by way of Antithesis) upon unjust Lawes.↩

Those Laws which do carry any thing of Freedom in their bowells, do owe their Originall to the Peoples choice; and have been wrested from the Rulers and Princes of the world, by importunity of intreaty, or by force of Armes: For the great men of the world being invested with the Power thereof, cannot be imagined to eclipse themselves or their own Pomp, unlesse by the violent interposition of the peoples spirits, who are most sensible of their own burdens, and most forward in seeking reliefe. So that Exorbitancie and Injustice on the part of Rulers was the rise of Laws in behalf of the People, which consideration will afford us this generall Maxime, That the pure and genuine intent of Lawes was to bridle Princes, not the People, and to keep Rulers within the bounds, of just and righteous Government: from whence, as from a Fountain, the rivulet of subjection and obedience on the peoples part, did reciprocally flow forth, partly to gratifie, and partly to incourage good and vertuous Governers: So that Lawes have but a secondary reflexion on the People, glancing onely at them, but looking with a full eye upon Princes. Agreeable to this is that of [2] Cicero Lib. 2. de Offic. whose words are to this effect: Cum premeretur ulim multitudo ab iis qui majores opes habebant, statim confugiebat ad unum aliquem virtute prastantem, &c. Jus enim semper quæsitum est æquabile, neq; enim aliter esset jus; id si ab uno bono et justo viro consequebantur, eo erant contenti; cum id minus contingeret, leges sunt inventæ," &c. (.i.) When the people did obtain redresse of their wrongs from some just and good man, they were satisfied therewith; but when they failed thereof, they found out Lawes, &c.

From which Assertion we may deduce a twofold corallarie.

1. That at the Foundation of Governments Justice was in men, before it came to be in Laws; for the onely Rule of Government, to good Princes, was their own wills; and people were content to pay them their subjection upon the security of their bare words: So here in England, in the daies of King Alfred, the Administration of Justice was immediately in the Crown, and required the personall attendance of the King.

2. But this course did soon bankerupt the world, and drive men to a necessity of taking bond from their Princes, and setting limits to their Power; hence it came to passe, that Justice was transmitted from men to Laws, that both Prince and People might read their duties, offences, and punishments before them.

And yet such hath been the interest of Princes in the world, that the sting of the Law hath been plucked out as to them; and the weight of it fallen upon the People, which hath been more grievous, because out of its place, the Element of the Law being beneficiall, not cumbersom within its own sphere. Hence it is, that Laws (like swords) come to be used against those which made them; and being put upon the rack of self and worldly interest, are forced to speak what they never meant, and to accuse their best friends, the People. Thus the Law becomes any thing or nothing, at the courtesie of great men, and is bended by them like a twig: Yea, how easie is it for such men to break those Customes which will not bow, and to erect traditions of a more complying temper [3] to the wills of those, whose end they serve. So that Law comes to be lost in Will and Lust; yea Lust by the adoption of greatnesse is enacted Law. Hence it comes to passe, that Laws upon Laws do bridle the People; and run counter to their end; yea the farther we go, the more out of the way. This is the originall of unjust Laws.

No marvell that Freedom hath no voice here, for an Usurper reigns; and Freedom is proscribed like an Exile, living only in the understandings of some few men, and not daring to appear upon the Theater of the world.

But yet the minds of men are the great wheeles of things; thence come changes and alterations in the world; teeming Freedom exerts and puts forth it self; the unjust world would suppresse its appearance, many fall in this conflict, but Freedom will at last prevaile, and give Law to all things.

So that here is the proper Fountain of good and righteous Laws, a spirit of understanding big with Freedom, and having a single respect to Peoples Rights, Judgement goes before to create a capacity, and Freedom follows after to fill it up. And thus Law comes to be the bank of Freedom, which is not said to straighten, but to conduct the streame. A people thus watered, are in a thriving posture; and the rather because the foundation is well laid, and the Law reduced to its originall state, which is the protection of the Poor against the Mighty.

If it were possible for a People to choose such Laws as were prejudiciall to themselves, this were to forsake their own interest: Here (you’l say) is free choice; But bring such Laws to the Rule, and there is a failer there; the Rule of righteous Laws are clear and righteous Principles (according to the severall appearances of truth within us) for Reason is the measure of all just Laws though the size differ according to the various apprehensions of People, or tempers of Common-Wealths, so that choice abstracted or considered in it self is no undeniable badge of a just Law, but as it is mixed with other ingredients; as on the contrarie Force and Power are not therefore condemned, because they have hands to strike, but because they have no eyes to see (i.e.) they are not usually [4] ballanced with understanding and right reason in making or executing of Laws, the sword having commonly more of the Beast in it, then the Man.

Otherwise, to be imposed upon by the art of truth, is to be caught by a warrantable guile, and to be kept by force from injuring ones self or others, hath more of courtesie then severenesse therein; And in this case reason will cast the scales and ascribe more to a seeing force then a blind choice; the righteousnesse or unrighteousnesse of things depends not upon the circumstances of our embracing or rejecting then, but upon the true nature of the things themselves: Let righteousnesse and truth be given out to the Nation, we shall not much quarrell at the manner of conveighance, whether this way, or that way, by the Beast, or by the Man, by the Vine, or by the Bramble.

There is a twofold Rule of corrupt Laws.

1. Principles of self and wordly greatnesse in the Rulers of the world, who standing upon the Mountain of Force and Power, see nothing but their own Land round about them, and make it their design to subdue Lawes as well as Persons, and enforce both to do homage to their wills.

2. Obsequiousnesse, Flatterie, or Compliancie of spirit to the foresaid principles, is the womb of all degenerous laws in inferiour Ministers: ’Tis hard indeed, not to swim with the stream, and some men had rather give up their Right then contend, especially upon apparent disadvantage; ’Tis true these things are temptations to men, and ’tis one thing to be deflowred, but to give up ones self to uncleannesse is another: ’Tis better to be ravished of our Freedoms (corrupt times have a force upon us) then to give them up as a Free-wil offering to the lusts of great men, especially if we our selves have a share with them in the same design.

Easinesse of spirit is a wanton frame, and so far from resisting, that it courts an assault; yea such persons are prodigall of other mens stock, and give that away for the bare asking, which will cost much labour to regain. Obsequious and servile spirits are the worst Guardians of the Peoples Rights.

Upon the advantage of such spirits, the interest of Rulers [5] hath been heightned in the world, and strictly guarded by severest Laws, And truly, when the door of an Interest flies open at a knock, no marvell that Princes enter in.

And being once admitted into the bosom of the Law, their first work is to secure themselves; And here what servility and flatterie are not able to effect, that Force and Power shall: And in order hereto a guard of Lawes is impressed to serve and defend Prerogative Power, and to secure it against the assaults of Freedom, so that in this case, Freedom is not able to stir without a load of prejudice in the minds of men, and (as a ground thereof) a visible guilt, as to the Letter of the Law.

But how can such Lawes be good which swerve from their end: The end of just Laws is the safety and freedom of a People.

As for safety, just Laws are bucklers of defence: when the mouth of violence is muzzled by a law, the innocent feed and sleep securely: when the wolvish nature is destroyed, there shall then be no need of law, as long as that is in being, the curb of the law keeps it in restraint, that the great may not oppresse or injure the small.

As for safety, laws are the Manacles of Princes, and the guards of private men: So far as lawes advance the Peoples Freedoms, so far are they just, for as the Power of the Prince is the measure of unrighteous lawes, so just laws are weigh’d in the balance of Freedom: where the first of these take place, the People are wholly slaves; where the second, they are wholly free: but most Common-wealths are in a middle posture, as having their lawes grounded partly upon the interest of the Prince, and partly upon the account of the People, yet so as that Prerogative hath the greatest influence, and is the chiefest ingredient in the mixture of Law, is in the Laws of England will by and by appear.

[6]

Chap. II. The Failers of our English Lawes, in their Originall, Rule, and End.↩

THe influence of force and power in the sanction of our English lawes, appears by this, That severall alterations have been made of our lawes, either in whole, or in part, upon every conquest. And if at any time the Conqueror hath continued any of the Ancient lawes, it hath been only to please and ingratiate himself into the people, for so generous Thieves give back some part of their money to Travellers; to abate their zeal in pursuit.

Upon this ground I conceive it is, why Fortescue (and some others) do affirm;Fortesc. cap. 17. That notwithstanding the severall conquests of this Realm, yet the same lawes have still continued, his words are these: Regnum Angliæ primò per Britones inhabitatum est, deinde per Romanos regulatum, iterumq́, per Britones, ac deinde per Saxones possessum, qui nomen eujus ex Britannia in Angliam mutaverunt; extunc per Danes idem regnum parumper dominatum est, & iterum per Saxones, sed finaliter per Normannes, quorum propago regnum illud obtinet in præsenti, & in omnibus Nationum harum & Regum earum temporibus, regnum illud iisdem quibus jam regitur consuetudinibus continuè regulatum est. That is, The Kingdom of England was first inhabited by the Britons, afterwards ’twas governed by the Romans; and again by the Britons, and after that by the Saxons; who changed its name from Brittain to England: In processe of time the Danes ruled here, and again the Saxons, and last of all the Normans, whose posterity, governeth the Kingdome at this day; And in all the times of these severall Nations, and of their Kings, this Realme was still ruled by the same customes, that it is now governed withall: Thus far Fortescue in the Reign of Henry the Sixth. Which opinion of his can be no otherwise explained (besides what we have already said) then that succeeding Conquerors did still retain those parts of former [7] Lawes, which made for their own interest; otherwise ’tis altogether inconsistent with reason, that the Saxons who banished the Inhabitants, and changed the Name, should yet retain the Lawes of this Island. Conquerors seldom submit to the law of the conquered (where Conquests are compleat, as the Saxons was) but on the contrary, especially when they bare such a mortall feud to their persons: which argument (if it were alone) were sufficient to demonstrate, that the Britons and their Lawes were banished together; and to discover the weaknesse of the contrarie opinion, unlesse you take the Comment together with the Text, and make that explanation of it which we have done.

And yet this is no honor at all to the Lawes of England, that they are such pure servants to corrupt interests, that they can keep their places under contrary masters; just and equall lawes will rather indure perpetuall imprisonment, or undergo the severest death, then take up Arms on the other side (yea Princes cannot trust such lawes) An hoary head (in a law) is no Crown, unlesse it be found in the way of righteousnesse, Prov. 16. 31.

By this it appears that the notion of fundamental law, is no such Idoll as men make it: For, what (I pray you) is fundamentall law, but such customs as are of the eldest date, & longest continuance? Now Freedom being the proper rule of Custom, ’tis more fit that unjust customs should be reduced, that they may continue no longer, then that they should keep up their Arms, because they have continued so long. The more fundamentall a law is, the more difficult, not the lesse necessarie, to be reformed: but to return.

Upon every Conquest, our very lawes have been found transgressors, and without any judiciall processe, have undergone the penalty of Abrogation; not but that our Lawes needed to be reformed, but the onely reason in the Conqueror was his own will, without respect to the Peoples Rights; and in this case the riders are changed, but the burdens continued, for meer force is a most partiall thing, and ought never to passe in a Jury upon the Freedoms of the People; and yet thus it hath been in our English Nation, as by examining the originall of it may appear; and in bringing down its pedigree to this present time,The several alterations of the Lawes of England. we shall easily perceive, that the British laws were altered by the Romans, the Roman law by the Saxons, the Saxon law by the Danes, the Danish law by King Edward the Confessor, King Edwards Lawes by [8] William the Conqueror, which being somewhat moderated and altered by succeeding Kings, is the present Common law in force amongst us, as will by and by appear.

The History of this Nation is transmitted down to us upon reasonable credit for 1700. yeers last past; but whence the Britons drew their originall (who inhabited this Island before the Roman Conquest) is as uncertainly related by Historians, as what their Lawes and Constitutions were; and truly after so long a series of times, ’tis better to be silent, then to bear false witnesse.

But certain it is, that the Britains were under some kind of Government, both Martiall and Civill, when the Romans entred this Island, as having perhaps borrowed some Lawes from the Greeks, the refiners of humane spirits, and the ancientest inventers of Lawes: and this may seem more then conjecturall, if the opinion of some may take place, that the Phœnicians or Greeks first sailed into Britain, and mingled Customes and Languages together: For, it cannot be denyed, that the Etymon of many British words seems to be Greekish, as (if it were materiall to this purpose) might be clearly shown.

But ’tis sufficient for us to know, that whatever the lawes of the Britons were upon the Conquest of Cæsar, they were reviewed and altered,Brittish Laws altered by the Romans. and the Roman law substituted in it’s room, by Vespasian, Papinian and others, who were in person here; yet divers of the British Nobles were educated at Rome, on purpose to inure them to their lawes.

The Civill law remaining in Scotland, is said to have been planted there by the Romans, who conquered a part thereof. And this Nation was likewise subject to the same law, till the subversion of this State by the Saxons, who made so barbarous a Conquest of the Nation, and so razed out the Foundation of former lawes, that there are lesse footsteps of the Civill law in this, then in France, Spain, or any other province under the Roman Power.

So that whilst the Saxons ruled here, they were governed by their own lawes,Roman Law altered by the Saxons. which differed much from the British law, some of these Saxon laws were afterward digested into form, and are yet extant in their originall tongue, and translated into Latin.

[9]

Saxon law altered by the Danes.The next alteration of our English lawes was by the Danes, who repealed and nulled the Saxon law, and established their owne in its stead; hence it is, that the Laws of England do bear great affinity with the Customes of Denmarke, in Descents of Inheritance, Trialls of Right, and severall other wayes: ’tis propable that originally Inheritances were divided in this Kingdom amongst all the Sons by Gavel-kind, which Custome seemes to have been instituted by Cæsar both amongst us, and the Germans, (and as yet remaines in Kent, not wrested from them by the Conqueror) but the Danes being ambitious to conform us to the pattern of their owne Countrey, did doubtlesse alter this Custome, and allot the Inheritance to the eldest son; for that was the course in Denmarke, as Walsingham reports in his Vpodigma Neustriæ; Pater cunctos filios adultos à se pellebat, præter unum quem haeredem sui juris relinquebat; (i.e.) Fathers did expose and put forth all their sons, besides one whom they made heir of their estates.

So likewise in Trialls of Rights by twelve men our Customes agree with the Danish, and in many other particulars which were introduced by the Danes, disused at their expulsion, and revived againe by William the Conqueror.

For after the Massacre of the Deans in this Island,Danish Law altered by K. Edward the Confessor. King Edward the Confessor did againe alter their Laws, and though he extracted many particulars out of the Danish Lawes, yet he grafted them upon a new stock, and compiled a Body of lawes since knowne by his name, under the protection of which the people then lived; so that here was another alteration of our English lawes.

And as the Danish law was altered by King Edward,Edw. the Confessors Laws altered by William the Conqueror. so were King Edwards lawes disused by the Conqueror, and some of the Danish Customes againe revived: And to clear this, we must consider, that the Danes and Normans were both of a stock, and situated in Denmarke, but called Normans from their Northern Situation, from whence they sailed into France, and setled their Customes in that part of it, which they called Normandy by their owne name, and from thence into Britain. And here comes in the great alteration of our English lawes by William the Conqueror, who selecting some passages out of the Saxon, and some out of the Danish law, and in both having greatest respect to [10] his owne Interest, made by the Rule of his Government, but his own will was an exception to this Rule as often as he pleased.

For, the alterations which the Conqueror brought in, were very great, as the clothing his lawes with the Norman Tongue, the appointment of Termes at Westminster, whereas before the people had Justice in their owne Countreyes, there being severall Courts in every County, and the Supreme Court in the County was called, Generale Placitum, for the determining of those Controversies which the Parish or the Hundred Court could not decide; the ordaining of Sheriffes and other Court-Officers in every County to keep people in subjection to the Crowne, and upon any attempt for redresse of injustice, life and land was forfeited to the King: Thus were the Possessions of the Inhabitants distributed amongst his Followers,Holinshed. yet still upon their good behaviour, for they must hold it of the Crowne, and in case of disobedience, the Propriety did revert: And in order hereto, certaine Rents yeerly were to be paid to the King. Thus as the Lords and Rulers held of the King, so did inferiour persons hold of the Lords; Hence come Landlord, Tenant, Holds, Tenures &c. which are slavish ties and badges upon men, grounded originally on Conquest and Power.

Yea the lawes of the Conqueror were so burthensome to the people, that succeeding Kings were forced to abate of their price, and to give back some freedome to the people: Hence it came to passe, that Henry the first did mitigate the lawes of his Father the Conqueror, and restored those of King Edward; hence likewise came the Confirmation of Magna Charta, and Charta Forestæ, by which latter, the power of the King was abridged in inlarging of Forrests, whereas the Conqueror is said to have demolished a vast number of buildings to erect and inlarge New Forests by Salisbury, which must needs bee a grievance to the people. These freedomes were granted to the people not out of any love to them, but extorted from Princes by fury of War, or incessantnesse of addresse; and in this case Princes making a vertue of necessity, have given away that, which was none of their own, and they could not well keep, in hope to regaine it at other times; so that what of freedome we have by the law, is the price of much hazard and blood. Grant, that the People seem to have had a shadow of freedome in choosing of lawes, as consenting [11] to them by their Representatives, or Proxies both before and since the Conquest, (for even the Saxon Kings held their Conventions or Parliaments,) yet whosoever shall consider how arbitrary such meetings were, and how much at the devotion of the Prince both to summon and dissolve, and withall how the spirit of Freedome was observed and kept under, and likewise how most of the Members of such Assemblies were Lords, Dukes, Earls, Pensioners to the Prince, and the Royall Interest, will easily conclude, that there hath been a failer in our English Lawes, as to matter of Election or free choice, there having been alwaies a rod held over the Choosers, and a Negative Voice, with a Power of dissolution, having alwaies nipt Fredome in the Bud.

The Rule of our English Lawes is as faulty as the Rise. The Rule of our laws may be referred to a twofold Interest.

1. The interest of the King which was the great bias and rule of the law, and other interests, but tributary to this: hence it is all our laws run in the name of the King, and are caried on in an Orb above the sphere of the people; hence is that saying of Philip Honor, Cum à Gulielmo Conquestore, quod perinde est ac tyrannus, institutæ sint leges Angliæ, admirandum non est quod solam Principis utilitatem respiciant, subditorum verò bonum desertum esse videatur. (i.e.) Since the laws of England were instituted by William the Conqueror, or Tyrant, ’tis no wonder that they respect onely the Prerogative of the King, and neglect the Freedome of the People.

2. The interest of the People, which (like a worme) when trod upon did turne againe, and in smaller iotas and diminutive parcells, wound in it selfe into the Texture of law, yet so as that the Royall interest was above it, and did frequently suppresse it at its pleasure. The Freedom which we have by the law, owns its originall to this interest of the People, which as it was formerly little knowne to the world, so was it misrepresented by Princes, and loaden with reproaches, to make it odious: yea, liberty the result thereof was obtained but by parcells, so that we have rather a tast then a draught of Freedome.

If then the rise and rule of our law be so much out of tune, no marvell that we have no good Musick in the end, but [12] Bondage, instead of freedom, and instead of safety, danger. For the law of England is so full of uncertainty, nicety, ambiguity, and delay, that the poor people are ensnared, not remedied thereby: the formality of our English law is that to an oppressed man, which School-Divinity is to a wounded spirit, when the Conscience of a sinner is peirced with remorse, ’tis not the niceitie of the Casuist, which is able to heale it, but the solid experience of the grounded Christian.

’Tis so with the law, when the poor & oppressed want right, they meet with law; which (as ’tis managed) is their greatest wrong; so that law it self becoms a sin, & an experimented grievance in this Nation. Who knows not that the web of the law intangles the small flies, and dismisseth the great? so that a mite of equity is worth a whole bundle of law: yea many times the very law is the badge of our oppression, its proper intent being to enslave the people; so that the Inhabitants of this Nation are lost in the law, such and so many are the References, Orders, and Appeales, that it were better for us to sit down by the losse, then to seek for relief; for law is a chargeable Physitian, and he which hath a great Family to maintain, may well take large fees.

For the Officers or meniall servants of the law are so numerous, that the price of right is too high for a poor man; yea many of them procuring their places by sinister waies, must make themselves savers by the vailes of their office; yea ’twere well, if they rested here and did not raise the Market of their Fees, for they that buy at a great rate, must needs sell deer.

But the poor and the oppressed pay for all, hence it is, that such men grow rich upon the ruines of others, and whilest law and Lawyer is advanced, equity and truth are under hatches, and the people subject to a legall Tyranny, which of all bondages is one of the greatest.

Meer force is its own argument, and hath nothing to plead for it, but it self, but when oppression comes under the notion of law, ’tis most ensnaring; for sober-minded men will part with some right to keep the rest, and are willing to bear to the utmost; but perpetuall burdens will break their backs (as the strongest jade tyres at the last) especially when there is no hope of relief.

[13]

Chap. III. Of the necessity of the Reformation of the Laws of England, together with the excellency (and yet difficulty) of the worke.↩

THe more generall a good is, the more divine and God-like: Grant that Prerogative lawes are good for Princes, and advantagious to their Interest, yet the shrubs are more in number then the Cedars in the Forrest of the world; and Lawes of Freedome in behalfe of the people are more usefull, because directed to a more generall good. Communities are rather to be respected, then the Private Interests of great men.

Good Patriots study the people, as Favourites do the Prince, and it is altogether impossible, that the people should be free without a Reformation of the law, the source and root of Freedome. An equall and speedy distribution of Right ought to be the Abstract and Epitome of all lawes, and if so,

Why are there so many delayes, turnings and windings in the laws of England?

Why is our law a Meander of Intricacies, where a man must have contrary winds before he can arrive at his destred Port?

Why are so many men destroyed for want of a Formality and Punctilio in law? And who would not blush, to behold seemingly grave and learned sages to prefer a letter, syllable or word before the weight and merit of a cause?

Why do the issue of most Law-suits depend upon Presidents rather then the Rule, especially the Rule of Reason?

Why are mens lives forfeited by the law upon light and triviall grounds?

Why do some laws exceed the offence? and on the contrary other offences are of greater demerit then the penalty of the law?

[14]

Why is the Law still kept in an unknown tongue, and the nicety of it rather countenanced then corrected?

Why are not Courts rejourned into every County, that the People may have right at their own doors, and such tedious journyings may be prevented?

Why under pretence of equity, and a Court of Conscience, are our wrongs doubled and trebled upon us, the Court of Chancerie being as extortionous (or more) then any other Court? yea ’tis a considerable Quaere, whether the Court of Chancery were not first erected meerly to elude the Letter of the Law, which though defective, yet had some certainty; and under a pretence of Conscience to devolve all causes upon meer will, swayed by corrupt interest. If former Ages have taken advantage to mix some wheat with the Tares, and to insert some mites of Freedom into our Lawes: why should we neglect (upon greater advantages) to double our files, and to produce the perfect image of Freedom, which is therefore neglected, because not known.

How otherwise can we answer the Call of God, or the cryes of the People, who search for Freedom as for an hid Treasure? yea, how can we be registred, even in the Catalogue of Heathens, who made lesse shew, but had more substance, and were excellent Justiciaries, as to the Peoples Rights: so Solon, Lycurgus &c. such morall appearances in the minds of men, are of sufficient Energie for the ordering of Common-wealths, and it were to be wished, that those States which are called Christian, were but as just as Heathens in their lawes, and such strict promoters of Common Right.

Pure Religion is to visit the Fatherlesse, and the most glorious Fast to abstain from strife, and smiting with the fist of wickednesse; in a word, to relieve the oppressed, will be a just Guerdon and reward for our pains and travell in the reformation of the law.

And yet this work is very hard, there being so many concerned therein, and most being buisier to advance and secure themselves, then to benefit the publike: yea our Phisitians being themselves Parties, and ingaged in those interests which freedom condemns, will hardly be brought to deny themselves, unlesse upon [15] much conviction and assistance from above; and yet this we must hope for, that the reformation of the times may begin in the breasts of our Reformers, for such men are likely to be the hopefull fire of freedom, who have the image of it engrafted in their own minds.

Chap. IV. Of the corrupt Jnterest of Lawyers in the Common-wealth of England.↩

OF Interests, some are grounded upon weaknesse, and some upon corruption; the most lawfull interests are sown in weaknesse, and have their rise and growth there: Apostle, Prophet, Evangelist were onely for the perfecting of the Saints; Phisitians are of the like interest to the body; marriage is but an help and comfort in a dead state for in the Resurrection they neither marry, nor are given in marriage.

Interests grounded upon weaknesse may be used, as long as our weaknesse doth continue, and no longer, for the whole need not a Phisician, &c. such interests are good, profitable, usefull; and in their own nature self-denying, (i.e) contented to sit down, and give way to that strength and glory to which they serve.

But the interest of Lawyers in this Common-wealth, seems to be grounded rather upon corruption, then weaknesse, as by surveying its originall, may appear. The rise and potency of Lawyers in this Kingdom, may be ascribed to a twofold ground.

1. The Unknownesse of the law, being in a strange tongue, whereas when the law was in a known language (as before the Conquest) a man might be his own Advocate. But the hiddennesse of the law, together with the fallacies and doubts thereof, render us in a posture unable to extricate our selves, but we must have recourse to the shrine of the Lawyer, whose Oracle is in such request, because it pretends to resolve doubts.

2. The quarterly Terms at Westminster, whereas when justice was administred in every County, this interest could not possibly grow to an height, but every man could mind and attend his own cause [16] without such journeying to and fro, and suchchargeable Attendance, as at Westminster-Hall. For, first in the County, the law was plain, and controversies decided by Neighbours of the Hundred who could be soon informed in the state of the matter, and were very ready to administer Justice, as making it their own case; but, as for Common Lawyers, they carry only the Idea of right and wrong in their heads, and are so far from being touched with the sense of those wrongs, against which they seem to argue, that they go on meerly in a formalitie of words, I speak not this out of emulation or envy against any mans person, but singly in behalf of the people against the corruption of the interest it self.

After the Conquest, when Courts and Terms were established a Westminster (for how could the Darling of Prerogative thrive unlesse alwaies under the Kings eye?) men were not at leisure to take so much pains for their own, but sometimes they themselves, sometimes their friends in their behalf, came up in Term-time to London, to plead their causes, and to procure justice: as yet the interest of Lawyers was a puny thing, for one friend would undertake to plead his cause for another; and he which was more versed in the tricks of the law, then his neighbour, would undertake a journey to London, at the request of those who had businesse to do, perhaps his charges born on the way, and some small reward for his pains; Innes of Court why so called, and when erected. there were then no stately Mansions for Lawyers, but such Agents (whether Parents, Friends or Neighbour to the Parties) lodged like other Travellers in Innes as Country Attornies still do: hence it came to passe, that when the interests of Lawyers came to be advanced in Edward the third's Time, their Mansions or Colledges were still called Innes, but with an Addition of honor, Innes of Court.

The proceed of Lawyers interest is as followeth: when such Agents, as we have spoken of, who were employed by their neighbours at London, and by this means coming to be versed in the niceties of the law, found it sweeter then the Plough, and Controversies beginning to increase, they took up their Quarters here till such time as they were formed into an orderly body, and distinct interest, as now they are. [1]

There is ground enough to conclude, even from the Letter of the Statute Law (in 28. Edw. 1. c. 11.) that mens Parents, Friends or Neighboures did plead for them, without the help of any other Lawyer.

[17]

After the Lawyers were formed into a Society and had hired the Temple of the Knights Templers for the place of their abode, their interest was not presently advanced, but by the Contentions of the people, after a long series of time, so that the interest of Lawyers (in the height which now it is) comes from the same root, as pride and idlenesse, (i.e.) from fulnesse of bread, or prosperity the mother of strife; not but that just and equall administrators of laws are very necessary in a Common-wealth, but when once that which was at first but a Title, comes to be framed into an interest, then it sets up it self, and growes great upon the ruines of others, and thorough the corruption of the people.

I take this to be a main difference between lawfull and corrupt interests, just interests are the servants of all, and are of an humble spirit, as being content to have their light put out by the brightnesse of that glory which they are supplemental to. But corrupt interests feare a change, and use all wiles to establish themselves, that so their fall may be great, and their ruin as chargeable to the world as it can; for such interests care for none but themselves.

The readiest way to informe such men is to do it within us for most men have the common Barrator within them, (i.e.) principles of contention and wrong; and thus the law becomes the Engine of strife, the instrument of lust, the mother of debates, and Lawyers are as make-bates between a man and his neighbour.

When Sir Walter Rawleigh was upon his triall, the Lawyers that were of Councell for the King, were very violent against him, whereupon Sir Walter turning to the Jury, used these words, Gentlemen, I pray you consider, that these men, meaning the Lawyers, do usually defend very bad causes every day in the Courts, against men of their own profession, as able as themselves, what then will they not do against me?&c. which Speech of his may be too truly affirmed of many Lawyers, who are any thing or nothing for gaine, and measuring Causes by their owne Interest, care not how long right be deferred and suits prolonged: There was a Suit in Glocestershire between two Families,Cambden Brit. in Glocest. which lasted since the Reign of Edward the fourth, till of late composed, which certainly must be ascribed either to the ambiguity of the law, or the subtilty of the Lawyers, neither of which are any great honor to the English Nation.

How much better were it to spend the acutenesse of the mind [18] in the reall and substantiall ways of good, and benefit to ourselves and others? and not to unbowell our selves into a meer Web, a frothy and contentious way of law, which the oppressed man stands in no more need of, then the tender-hearted Christian of Thomas Aquinas to resolve him in his doubts.

If there be such a thing as right in the world, let us have it sine suco.Why is it delayed, or denyed, or varnished over with guily words? Why comes it not forth in its owne Dresse? Why doth it not put off law, and put on reason; the mother of all just laws? Why is not ashamed of its long and mercenary train? Why can we not ask it and receive it our selves, but must have it handed to us by others? In a word, why may not a man plead his own Case? or his friends and acquaintance (as formerly) plead for him?

Memorable is that passage in King James Speech in Star-Chamber, In Countreys (sayes he) where the formality of law hath no place, as in Denmark, all their State is governed only by a written law, there is no Advocate or Procter admitted to plead, only the parties themselves plead their own cause, and then a man stands up and pleads the law, and there is an end; for the very Law-Book it self is their only Judge: happy were all Kingdoms, if they could be so: but here curious wits, various conceits, different actions, and variety of examples breed questions in law. Thus far he. And if this Kingdom doth resemble Denmark in so many other Custom, why may it not be assimilated to it in this also? especially considering, that the world travells with Freedom, and some real compensation is desired by the people, for all their sufferings, losses, (and) blood.

To clear the Channel of the law is an honorable worke for a Senate, who should be preservers of the Peoples Rights.

FINIS.