William Walwyn, A Prediction of Mr. Edwards (11 August 1646).

For further information see the following:

- This is part of the Leveller Collection of Tracts and Pamphlets Project.

- some biographical information about William Walwyn (1600-1680)

- a full list of the Leveller Tracts and Pamphlets in chronological order

Bibliographical Information

ID Number

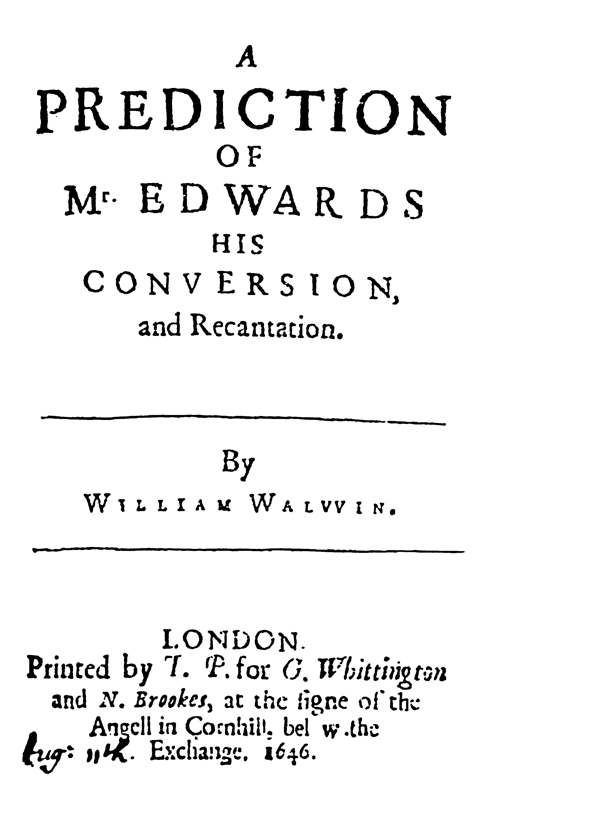

T.73 [1646.08.11] William Walwyn, A Prediction of Mr. Edwards. His Conversion, and Recantation (11 August 1646)

Full title

William Walwyn, A Prediction of Mr. Edwards. His Conversion, and Recantation. By

William Walwyn.

London. Printed by T.P. for G. Whittington and N. Brookes, at the signe of

the Angell in Cornhill, below the Exchange. 1646.

Estimated date of publication

11 August 1646.

Thomason Tracts Catalog information

TT1, p. 457; E. 1184. (5.)

Editor’s Introduction

(Placeholder: Text will be added later.)

Text of Pamphlet

There hath of late so much labour, and so many good discourses beene bestowed upon Mr. Edwards, and with so pious and good intentions, that it is not to be supposed, so many precious endevours can be vaine or fruitlesse, in reference to his conversion.

In cases so desperate as his, the worst signes are the best; as wee use to say, when things are at the worst, they are nearest to an amendment.

To an impartiall judgement, that seriously considers the violence of his spirit, manifested against harmelesse, well-meaning people, that differ with him in judgement: He cannot but seeme, at best, in that wretched condition, that Paul was in, when hee breathed out threatnings and slaughter, against the disciples of the Lord; and went unto the High Priest, and desired of him letters to Damascus, to the Synagogues, that if he found any of this way, whether they were men or women, he might bring them bound unto Jerusalem.

For certainly, had not Authority, in these our times, being endowed with much more true Christian wisdome then such teachers, and through the power thereof, had not restrained the bitternesse of his (and the like) spirits: we had had (before this time) multitudes of both men and women, brought from all parts of this Nation, bound, unto London, if not burned in Smithfield.

But many there are, that feare, his condition is much more sad, and desperate, then this of Pauls, (which yet the blessed Apostle was much troubled to thinke on, long after his conversion, accompting himselfe as one borne out of due time, and not worthy the name of an Apostle, because he persecuted the Church of God.) It being exceedingly feared that in all his unchristian writings, preachings, and endevours, to provoke Authority against conscientious people, that therein he goeth against the light of his owne conscience, that he is properly an Heretique, one that is subverted and sinneth, being condemned of himselfe.

And indeed, who ever shall consider, the exceeding Light that hath been darted from so many Seraphick Quills, shining round about him; amidst his persecuting intentions, (all which he hath hitherto resisted) will find and confesse; there is cause to feare: So great a shining and a burning light, that it cannot be doubted, but that hee discerneth, how unreasonable a thing it is, that one erring man should compell or comptroule another mans practice, in things supernaturall: or that any lawes should be made for punishing of mis-apprehentions therein, wherein thousands are as liable to be mistaken; as one single person.

He must needs know, that, only things naturall and rationall are properly subject unto government: And that things supernaturall, such as in Religion are distinguished by the title of things divine; such, as the benefit and use thereof, could never have beene perceived by the light of nature and reason: that such things are not liable to any compulsive government, but that therein every one ought to be fully perswaded in their owne minds; because whatsoever is not of faith is sinne.

He cannot be ignorant, how disputable all the parts of Divinity are amongst the most learned, how then can he judge it so horrible a thing as he seems to doe, for men to differ, though upon the highest points: he knowes every one is bound to try all things, the unlearned as well as the learned: now if there be different understandings, some weaker and some stronger, (as there are) how is it possible but there will (upon every tryall) be difference in degrees of apprehensions: and surely he will not say that weaknesse of understanding is sinfull where there is due endevour after knowledge: and though it should be sinfull in the sight of a pure God, yet will he not say it is punishable, by impure and erronious man: But,

To rayle revile, reproch, backbite, slander, or to despise men and women, for their weaknesses: their meanes of trades and callings, or poverty, is so evidently against the rule of Christ and his Apostles, that he cannot but condemne himselfe herein: his understanding is so great, and he is so well read in Scripture, that he must needs acknowledge, these cannot stand with Love: that knowne and undisputable Rule.

Insomuch, as if bad signes in so desperate a case as his is, are the best, surely he is not farre from his recovery and conversion.

With God there is mercy, his mercyes are above all his workes, his delight is in shewing mercy: and the Apostle tells us where sinne hath abounded grace (or love) hath super-abounded: O that he would stand still a while, and consider the love of Christ, that he would throw by his imbittered pen, lock himselfe close in his study, draw his curteines, and sit downe but two houres, and seriously, sadly, and searchingly lay to heart, the things he hath said and done, against a people whom he knoweth, desire to honour God: and withal to bear in mind the infinite mercy of God, that where sin hath abounded, grace hath over abounded: certainly it could not but work him into the greatest and most burning extremity that ever poor perplexed man was in, such an extremity as generally proves Gods opportunity, to cast his aboundant grace so plentifully into the distressed soule, as in an instant burnes and consumes all earthly passions, and corrupt affections, and in stead thereof fills the soule with love, which instantly refineth and changeth the worst of men, into the best of men.

May this be the happy end of his unhappy labours: it is the hearty desire of those whom he hath hitherto hated, and most dispitefully used; (nothing is to hard for God) it will occasion joy in Heaven, and both joy and peace in earth, you shal then see him a man composed of all those opinions he hath so much reviled: an Independent: so far as to allow every man to be fully perswaded in his owne mind, and to molest no man for worshiping God according to his conscience.

A Brownist: so far, as to separate from all those that preach for filthy lucre: An Anabaptist: so far, at least, as to be rebaptised in a floud of his owne true repentant teares: A seeker: in seeking occasion, how to doe good unto all men, without respect of persons or opinions: he will be wholly incorporate into the Family of love, of true Christian love, that covereth a multitude of evils: that suffereth long, and is kind, envieth not, vanteth not it selfe, is not puffed up, doth not behave it selfe unseemly, seeketh not her owne, is not easily provoked &c. And then: you may expect him to breake forth and publish to the world, this or the like recantation.

Where have I been! Into what strange and uncouth pathes have I run my self! I have long time walked in the counsell of the ungodly, stood in the way of sinners, and too too long sate in the seat of the scornful!

O vile man, what have I done? Abominable it is!

O wretched man, how have I sinned against God! It shameth me: It repenteth me: My spirit is confounded within me.

I have committed evils, of a new and unparalelled nature, such as the Protestant Religion in all after-ages will be shamed of. For I have published in print to the view of all men the names of divers godly well affected persons, and reproached them as grand Impostors, Blasphemers, Heretiques and Schismatiques, without ever speaking with them my seife.

And though I am conscious to my selfe, of many weaknesses, and much error, and cannot deny, but I may be mistaken in those things, wherein, at present I am very confident, yet have I most presumptuously and arrogantly, assumed to my selfe, a power of judging, and censuring all judgements, opinions, and wayes of worship (except my owne) to bee either damnable, hereticall, schismaticall, or dangerous: And though I have seene and condemned the evill of it in the Bishops and Prelates, yet (as they) have I reviled & reproached them, under the common nicknames of Brownists, Independents, Anabaptists, Antinomians, Seekers, and the like: of purpose to make them odious to Authority, and all sorts of men: whereby I have wrought very much trouble to many of them, in all parts throughout this Nation; and have caused great disaffection in Families, Cities and Counties, for difference in judgement, (which I ought not to have done) Irritating and provoking one against an other, to the dissolving of all civill and naturall relations, and as much as in me lay, inciting and animating to the extirpation and utter ruine one of another, in so much as the whole Land (by my unhappy meanes, more then any others) is become a Nation of quarrels, distractions, and divisions, our Cities, Cities of strife, slander, and backbiting; by occasion whereof, both our counsell and strength faileth, and all the godly party in the Land, are now more liable to abuse and danger, whether they are Presbyterians, Independents, or others, then they have been since the beginning of this Parliament; though many of them are so blinded by my writings and discourses, and so perverted in their understandings that they cannot discerne it: And wherefore I have done all this, O Lord God thou knowest, and I tremble to remember, for I have done it out of the pride and vanity of my owne mind, out of disdaine, that plaine unlearned men should seeke for knowledge any other way then as they are directed by us that are learned: out of base feare, if they should fall to teach one another, that wee should lose our honour, and be no longer esteemed as Gods Clergy, or Ministers Jure divino; or that we should lose our domination in being sole judges of doctrine and discipline, whereby our predecessours have over ruled States and Kingdomes.

O lastly, that we should lose our profits and plentious maintenance by Tithes, offerings, &c. which our predecessours (the Clergie) for many ages have enjoyed as their proper right, and not at the good will of the owners, or the donation of humane authority: All this I saw comming in with that liberty, which plaine men tooke, to try and examine all things; and therefore being overcome with selfe-respect, and not being able to withstand so strong temptations, being also then filled with a kind of knowledge that puffeth up: I betooke my selfe to that unhappy worke, to make all men odious, that, either directly, or by consequence, did any thing towards the subversion of our glory, power, or profit.

In doing whereof: what wayes and means I have taken for intelligence: What treachery, inhumanity, and breach of hospitality, I have countenanced and encouraged; my conscience too sadly tels me, and my unhappy bookes (if duly weighed) will to my shame discover.

The most knowing, judicious, understanding men that opposed me, or my interest, I knew were those, that did and could most prejudice our cause; and therefore I set my selfe against them in a more speciall manner, labouring by any meanes to make them odious to all societies, that so they might not be credited in any thing they spake.

The truth is: In this my perverse and sad condition, whilst I stood for maintenance of my corrupt interest, it was impossible for me, truly to love a judicious or an enquiring man: I loved none, but superstitious or ignorant people, for which such I could perswade, and over such I could bear rule: such would pay whatsoever I demanded, and do whatever I required: they spake as I spake, commended what I approved, &c reproached, as I reproached: I could make them run point-blanck against Authority, or fly in the face of any man, for these took me really for one of Gods Clergie, admired my parts and learning, as gifts of the Holy Ghost, and beleeved my erring Sermons to be the very word of God; willingly submitted their consciences and religion to my guidance.

Whilst (as indeed it is) an understanding enquiring man, studious in the Scriptures, instantly discerneth me to be but as other laymen, and findeth our learning to be but like other things that are the effects of study and industry, and that our preachings are like any other mens discourses, liable to errours and mistakings, and are not the very Word of God, but our apprehensions drawne from the Word.

I confesse now most willingly to my owne shame, that there was nothing which I conceived effectuall, to work upon the superstitious or ignorant, but I made use thereof as the Prelats had don before me, yea I strictly observed order in such things as few men consider, & yet are very powerful in the minds of many; as the wearing of my Cloak of at least a Clergy-mans length, my Hat of a due breadth and bignesse, both for brim and crown, somewhat different from lay men, my band also of a peculiar straine, and my clothes all black, I would not have worne a coloured sute at any rate, that I thought enough to betray all, nor any triming on my black, as being unsutable to a Divines habit.

I had a care to be sadder in countenance and more sollernne in discourse because it was the custom of a Clergy man, this I did though I knew very well the Apostles of Christ, used no such vaine distinctions, but being not indeed unlike other men, through any endowments from on high, or power of miracles, and yet resolving to maintayn a distinction, (being unable to do it by any thing substantiall, I concluded it must be done (as it long time had been, both in the Romish and Prelatique Church) even by vain and Fantastick distinctions, such as clothes and other formalities; and though I knew full well, that God was no respecter of persons, and that he made not choise of the great, or learned men of the world, to be his Prophets and publishers of the Gospel: but Heards-men, Fisher-men Tentmakers Tollgatherers, &c. and that our Blessed Saviour thought it no disparagement to be reputed the Sonne of a Carpenter: yet have I most unworthily reviled and reproached, divers sorts of honest Tradesmen, and other usefull laborious people, for endevouring to preach and to instruct those that willingly would be instructed by them, tearming them illiterate Mechanicks, Heriticks, and Scismaticks, meerly because I would not have my superstitious friends, to give any eare or regard unto them.

And for these respects, have I magnified our publique Churches or meeting places, and reproached and cryed out upon all preachings in private houses, calling them conventicles and using all endevours, to make all such private meetings liable to that Statute that was enacted, and provided to restraine and avoyd all secret plotings against the civill government, when in the meane time I knew the scriptures plainly shewed, both by the precepts and practices of our Saviour and his Apostles, that all places are indifferent, whether in the mountaine or in the fields, on the water, in the ship, or on the shore, in the Synagogues Or, privat houses, in an upper or low-roome; all is one, they went preaching the Gospell from house to house. Not in Jerusalem, nor in this mountaine, but in every place he that lifteth up pure hands is accepted. Wheresoever two or three are gathered together in my name, there (saith our Saviour) I will be in the widest of them, all this I knew: yet, because the superstitious were (through long custom) zealous of the publique places, I applyed my selfe therein, to their humors and my owne ends, and did what I could to make all other places odious and ridiculous: though now I seriously acknowledge, that a plaine discreet man in a privat house, or field, in his ordinary apparell, speaking to plaine people (like himseife) such things as he conceiveth requisit for their knowledge, out of the word of God, doth as much (if not more) resemble the way of Christ and the manner of the Apostles, as a learned man in a carved pulpet, in his neate and black formalities, in a stately, high, and stone-built Church, speaking to an audience, much more glorious and richly clad, then most Christians mentioned in the Scriptures: and may be as acceptable. I have most miserably deluded the world therein, and those most with whom I have beene most familiar, and have thereby drawne off their thoughts from a consideration of such things as tended to love, peace and joy in the Holy Ghost, to such things as tended neither to their owne good nor the good, of others. I have beene wise in my own eyes, and despised others, but I must abandon all, I must become a foole that I may bee wise, hitherto I have promoted a meere Clergy Religion, but true Christian religion; pure religion and undefiled I have utterly neglected: I have wrested the covenant from its naturall and proper meaning, to make use thereof for the establishment of such a Church government, as would maintaine the power of the Clergy distinct from and above the power of Parliaments, and such as would have given full power to suppresse and crush all our opposers, but I now blesse God, the wisdom of Parliament discerned and prevented it.

I have been too cruel and hard hearted against men for erors in religion, or knowledge supematurall, though I my selfe have no infallible spirit to discern between truth and erors, yea though I have seene them so zealous & conscientious in their judgments (as to be ready to give up their lives for the truth thereof) yet have I (as the Bishops were wont) argued them of obstinacy, and in stead of taking a christian-like way to convert them, have without mercy censured, some of them worthy of imprisonments, and some of death, but I would not be so used, nor have I done therein as I would be done unto my selfe.

I have beene a great respecter of persons, for outward respects, the man in Fine rayment, and with the gold ring, I have ever prefered whilst the poore and needy have beene low in my esteeme.

I have too much loved greetings in the market place, and the uppermost places at feasts, and to be called Rabby.

And to fill up the measure of my iniquity: I have had no compassion on tender consciences, but have wrought them all the trouble cruelty and misery I could, and had done much more but that through the goodnesse of God, the present authority was too just and pious to second my unchristian endevours: My mercifull Saviour would not breake the brused reed, nor quench the smokeing flax, but my hard heart hath done it. O that I had not quenched, that I had not resisted the Spirit, what fruit have I of those things whereof I am now ashamed; 0 how fowle I am, and filthy, yea how naked and all-uncovered, my hidden sinne lyes open, I see it, and the shame of it, and how fowie it is; and the sight of it grieveth and exceedingly troubleth me. I would faine hide my selfe from mine owne sinne, but cannot; it pursueth me, it cleaveth unto me, it stands ever before me and I am made to possesse my sinne, though it be grievous and loathsome and abominable and filthy above all that I can speake, what shall I doe? whither shall I fly? who can deliver me from this body of death? my spirit is so wounded I am not able to beare: Can there be mercy for me? can there be balme for my wounded spirit, that never had compassion on a tender conscience? my case is sad and misserable, but there is balme in Gilead: with God there is mercy: with him is plenteous redemption, I will therefore goe to my Father and say unto him. Father I have sinned against Heaven and against thee, I am not worthy to be called thy child, make me as one of thine hired servants, I will faithefully apply my selfe to thy will, and to the study of thy Commandements, yea I will both study and put in practice thy new commandement, which is love, I will redeem the time I have mispent: love will help me, for God is love, the love of Christ will constraine me, through love I shall be enabled to doe all things, should I not love him that hath loved me, and shewed mercy unto me, for so many thousand sinnes, shall not his kindnesse beget kindnesse in me, yes love hath filled me with love, so let me eate, and so let me drinke, for ever, love is good and seeketh the good of all men, it helpeth and hurteth not, it blesseth, it teacheth, it feedeth, it clotheth, it delivereth the captive, & setteth the oppressed free, it breakes not the brused reed, nor quencheth the smokeing flaxe, farewell for ever all old things, as pride envy coveteousnesse reviling, and the like, and welcome love, that maketh all things new, even so let love possesse me, let love dwell in me, and me in love, and when I have finished my dayes in peace, and my yeares in rest, I shall rest in peace, and I shall dwell with love, that have dwelt in love.

May his meditations hence-forward, and his latter end be like unto this, or more exellent and Heavenly, which is all the harme I wish unto him, as haveing through Gods mercy, in some measure, learned that worthy and Heavenly lesson of my Saviour, But I say unto you, love your enemies etc. and may all that love the Lord Jesus, increase therein.