Biographies of the Leading Levellers (and others)

Levellers: Henry Ireton | John Lilburne | Richard Overton | Thomas Rainborow | Edward Sexby | John Streeter | William Walwyn | John Wildman

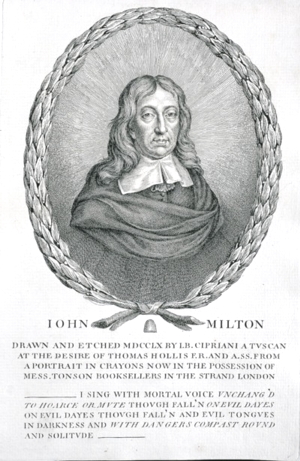

Others: James Harrington | Andrew Marvell | John Milton | Marchamont Needham | William Prynne | Algernon Sidney

Critics: Sir Robert Filmer

Note: See the collection of Leveller Tracts.

[Created: 22 Dec. 2020]

[Updated: March 25, 2024 ] |

Levellers

Henry Ireton (1611–1651)

Dictionary of National Biography entry

Source: Charles Harding Firth, ”Ireton, Henry” Dictionary of National Biography (1885-1900), pp. 37-43. <https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Dictionary_of_National_Biography,_1885-1900/Ireton,_Henry>

IRETON, HENRY (1611–1651), regicide, baptised 3 Nov. 1611, was the eldest son of German Ireton of Attenborough, near Nottingham. His father, who settled at Attenborough about 1605, was the younger brother of William Ireton of Little Ireton in Derbyshire (Cornelius Brown, Worthies of Nottinghamshire, p. 182). Henry became in 1626 a gentleman-commoner of Trinity College, Oxford, and took the degree of B.A. in 1629. According to Wood, ‘he had the character in that house of a stubborn and saucy fellow towards the seniors, and therefore his company was not at all wanting’ ( Athenæ Oxon. ed. Bliss, iii. 298). In 1629 he entered the Middle Temple (24 Nov.), but was never called to the bar ( The Trial of Charles I, with Biographies of Bradshaw, Ireton, &c., in Murray's Family Library, 1832, xxxi. 130).

At the outbreak of the civil war Ireton was living on his estate in Nottinghamshire, ‘and having had an education in the strictest way of godliness, and being a man of good learning, great understanding, and other abilities, he was the chief promoter of the parliament's interest in the county’ (Hutchinson, Memoirs of Col. Hutchinson, ed. 1885, i. 168). On 30 June 1642 the House of Commons nominated Ireton captain of the troop of horse to be raised by the town of Nottingham ( Commons' Journals, ii. 664). With this troop he joined the army of the Earl of Essex and fought at Edgehill, but returned to his native county with it at the end of 1642, and became major in Colonel Thornhagh's regiment of horse (Hutchinson, i. 169, 199). In July 1643 the Nottinghamshire horse took part in the victory at Gainsborough (28 July), and shortly afterwards Ireton ‘quite left Colonel Thornhagh's regiment, and began an inseparable league with Colonel Cromwell’ (ib. pp. 232, 234). He was appointed by Cromwell deputy governor of the Isle of Ely, began to fortify the isle, and was allowed such freedom to the sectaries that presbyterians complained it was become ‘a mere Amsterdam’ ( Manchester's Quarrel with Cromwell, Camden Soc., 1875, pp. 39, 73). He served in Manchester's army during 1644, with the rank of quartermaster-general, and took part in the Yorkshire campaign and the second battle of Newbury. Although Ireton, in writing to Manchester, represented the distressed condition of the horse for want of money ( Hist. MSS. Comm. 8th Rep. pt. ii. p. 61), he was anxious that Manchester should march west to join Waller, and after the miscarriages at Newbury supported Cromwell's accusation of Manchester by a most damaging deposition ( Cal. State Papers, Dom. 1644–5, p. 158).

Ireton does not appear in the earliest list of the officers of the new model, but directly the campaign began he obtained the command of the regiment of horse to which Sir Michael Livesey had been at first appointed ( Lords' Journals, viii. 278; Sprigge, Anglia Rediviva, ed. 1854, p. 331). The night before the battle of Naseby he surprised the royalists' quarters, ‘which they had newly taken up in Naseby town,’ took many prisoners, and alarmed their whole army. Next day Fairfax, at Cromwell's request, appointed Ireton commissary-general of the horse and gave him the command of the cavalry of the left wing. The wing under his command was worsted by Rupert's cavaliers and partially broken. Ireton, seeing some of the parliamentary infantry hard pressed by a brigade of the king's foot, ‘commanded the division that was with him to charge that body of foot, and for their better encouragement he himself with great resolution fell in amongst the musketeers, where his horse being shot under him, and himself run through the thigh with a pike and into the face with an halbert, was taken prisoner by the enemy.’ When the fortune of the day turned Ireton promised his keeper liberty if he would carry him back to his own party, and thus succeeded in escaping ( ib. pp. 36, 39, 42). He recovered from his wounds sufficiently quickly to be with the army at the siege of Bristol in September 1645 ( ib. pp. 99, 106–18). The letter of summons in which Fairfax endeavoured to persuade Rupert to surrender that city was probably Ireton's work.

Ireton was one of the negotiators of the treaty of Truro (14 March 1646), and was afterwards despatched with several regiments of horse to block up Oxford, and prevent it from being provisioned ( ib. pp. 229, 243). The king tried to open negotiations with him, and sent a message offering to come to Fairfax, and live wherever parliament should direct, ‘if only he might be assured to live and continue king.’ Ireton refused to discuss the king's offers, but wrote to Cromwell begging him to communicate the king's message to parliament. Cromwell blamed him for doing even that, on the ground that soldiers ought not to touch political questions at all (Cary, Memorials of the Civil War, i. 1; Gardiner, Great Civil War, ii. 470). Ireton took part in the negotiations which led to the capitulation of Oxford, and married Bridget, Cromwell's daughter, on 15 June 1646, a few days before its actual surrender. The ceremony took place in Lady Whorwood's house at Holton, near Oxford, and was performed by William Dell [q. v.], one of the chaplains attached to the army (Carlyle, Cromwell, i. 218, ed. 1871).

Though the marriage was the result of the friendship between Cromwell and Ireton, rather than its cause, it brought the two men closer together. The union and the confidence which existed between them was during the next four years a factor of great importance in English politics. Each exercised much influence over the other. ‘No man,’ says Whitelocke, ‘could prevail so much, nor order Cromwell so far, as Ireton could’ ( Memorials, f. 516). Ireton had a large knowledge of political theory and more definite political views than Cromwell, and could present his views logically and forcibly either in speech or writing. On the other hand, Cromwell's wider sympathies and willingness to accept compromises often controlled and moderated Ireton's conduct.

On 30 Oct. 1645 Ireton was returned to parliament as member for Appleby; but there is no record of his public action in parliament until the dispute between the army and the parliament began ( Names of Members returned to serve in Parliament, i. 495). His justification of the petition of the army, which the House of Commons on 29 March 1647 declared seditious, involved him in a personal quarrel with Holles, who openly derided his arguments. A challenge was exchanged between them, and the two went out of the house intending to fight, but were stopped by other members, and ordered by the house to proceed no further. On this basis Clarendon builds an absurd story that Ireton provoked Holles, refused to fight, and submitted to have his nose pulled by his choleric opponent ( Clarendon MSS. 2478, 2495; Rebellion, x. 104; Ludlow, ed. 1751, p. 94; Commons' Journals, 2 April 1647). Thomas Shepherd of Ireton's regiment was one of the three troopers who presented the appeal of the soldiers to their generals, which Skippon on 30 April brought to the notice of the House of Commons. In consequence Ireton, Cromwell, Skippon, and Fleetwood, being all four members of parliament, as well as officers of the army, were despatched by the house to Saffron Walden ‘to employ their endeavours to quiet all distempers in the army.’ The commissioners drew up a report on the grievances of the soldiers, which Fleetwood and Cromwell were charged to present, while Skippon and Ireton remained at headquarters to maintain order. Ireton foresaw a storm unless parliament was more moderate, and had little hope of success. In private and in public he had at first discouraged the soldiers from petitioning or taking action to secure redress, but when an open breach occurred he took part with the army ( Clarke Papers, i. 94, 102; Cary, Memorials of the Civil War, i. 205, 207, 214). When Fairfax demanded by whose orders Joyce had removed the king from Holdenby, Ireton owned that he had given orders for securing the king there, though not for taking him thence (Huntingdon's reasons for laying down his commission, Maseres, Tracts, i. 398). From that period his prominence in setting forth the desires of the army and defending its conduct was very marked. ‘Colonel Ireton,’ says Whitelocke, ‘was chiefly employed or took upon him the business of the pen, … and was therein encouraged and assisted by Lieutenant-general Cromwell, his father-in-law, and by Colonel Lambert’ ( Memorials, f. 254).

The form, if not the idea, of the ‘engagement’ of the army (5 June) was probably due to Ireton, and the remonstrance of 14 June was also his work (Rushworth, vi. 512, 564). He took part in the treaty between the commissioners of the army and the parliament, and when the former decided to draw up a general summary of their demands for the settlement of the kingdom, the task was entrusted to Ireton and another ( Clarke Papers, i. 148, 211). The result was the manifesto known as ‘The Heads of the Army Proposals.’ By it Ireton hoped to show the nation what the army would do with power if they had it, and he was anxious that no fresh quarrel with parliament should take place until the manifesto had been published to the world. He hoped also to lay the foundation of an agreement between king and parliament, and to establish the liberties of the people on a permanent basis ( ib. pp. 179, 197). But, excellent though this scheme of settlement was, it was too far in advance of the political ideas of the moment to be accepted either by king or parliament. Ireton was represented as saying that what was offered in the proposals was so just and reasonable that if there were but six men in the kingdom to fight to make them good, he would make the seventh (‘Huntingdon's Reasons,’ Maseres, i. 401). In his anxiety to obtain the king's assent he modified the proposals in several important points, and consequently imperilled his popularity with the soldiers. When the king rejected the terms offered him by parliament, Ireton vehemently urged a new treaty, and told the house that if they ceased their addresses to the king he could not promise them the support of the army (22 Sept. 1647). Pamphlets accused him of juggling and underhand dealing, of betraying the army and deluding honest Cromwell to serve his own ambition, and of bargaining for the government of Ireland as the price of the king's restoration ( Clarke Papers, i. Preface, xl–xlvi; A Declaration of some Proceedings of Lieutenant-colonel John Lilburn, 1648, p. 15). In the debates of the council of the army during October and November 1649, Sexby and Wildman attacked him with the greatest bitterness. Ireton passionately disavowed all private engagements, and asserted that if he had used the name of the army to support a further application to the king, it was because he sincerely believed himself to be acting in accordance with the army's views. He had no desire, he said, to set up the king or parliament, but wished to make the best use possible of both for the interest of the kingdom ( Clarke Papers, i. 233). In resisting a rupture with the king he urged the army, for the sake of its own reputation, to fulfil the promises publicly made in its earlier declarations ( ib. p. 294). With equal vigour he opposed the new constitution which the levellers brought forward, under the title of ‘The Agreement of the People,’ and denounced the demand for universal suffrage as destructive to property and fatal to liberty, although for a limitation of the duration and powers of parliament and a redistribution of seats he was willing to fight if necessary ( ib. p. 299). He wished to limit the veto of the king and the House of Lords, but objected to the proposal to deprive them altogether of any share in legislation.

Burnet represents Ireton as sticking at nothing in order to turn England into a commonwealth; but in the council of the army he was in reality the spokesman of the conservative party among the officers, anxious to maintain as much of the existing constitution as possible. The constitution was always in his mouth, and he detested and dreaded nothing so much as the abstract theories of natural right on which the levellers based their demands ( ib. Preface, pp. lxvii–lxxi; Burnet, Own Time, ed. 1833, i. 85).

On 5 Nov. the council of the army sent a letter to the speaker, disavowing any desire that parliament should make a fresh application to the king, and Ireton at once withdrew from their meetings, protesting that unless they recalled their vote he would come there no more ( Clarke Papers, p. 441). But the flight of the king to the Isle of Wight (11 Nov.) led to an entire change in his attitude. The story of the letter from Charles to the queen, which Cromwell and Ireton intercepted, is scarcely needed to account for this change. Without it Ireton perceived the impossibility of the treaty with Charles, on which he had hoped to rest the settlement of the kingdom (Birch, Letters between Colonel Robert Hammond, General Fairfax, &c., 1764, p. 19). He held that the army's engagements to the king were ended, and when Berkeley brought the king's proposals for a personal treaty to the army, received him with coldness and disdain, instead of his former cordiality (29 Nov. 1647; Berkeley, Memoirs; Maseres, i. 384). Huntingdon describes him as saying, when the probability of an agreement between king and parliament was spoken of, ‘that he hoped it would be such a peace as we might with a good conscience fight against them both’ ( ib. i. 404). When Charles refused the ‘Four Bills,’ Ireton urged parliament to settle the kingdom without him (Walker, History of Independency, i. 71, ed. 1661). As yet he was not prepared to abandon the monarchy, and for a time supported the plan of deposing the king and setting the Prince of Wales or Duke of York on the throne ( ib. p. 107; Gardiner, Great Civil War, iii. 294, 342).

In the second civil war Ireton served under Fairfax in the campaigns in Kent and Essex. After the defeat of the royalists at Maidstone he was sent against those in Canterbury, who capitulated on his approach (8 June 1648) (Rushworth, vii. 1149; Lords' Journals, x. 320). He then joined Fairfax before Colchester, and was one of the commissioners who settled the terms of its surrender (Rushworth, vii. 1244). To Ireton's influence and to his ‘bloody and unmerciful nature’ Clarendon and royalist writers in general attribute the execution of Lucas and Lisle ( Rebellion, xi. 109; Mercurius Pragmaticus, 3–10 Oct. 1648; Gardiner, Great Civil War, iii. 463). Ireton approved the decision of the council of war which sentenced them to death, and defended its justice both in an argument with Lucas himself at the time and subsequently as a witness before the high court of justice. There is no foundation for the charge that the sentence was a breach of the capitulation [see Fairfax, Thomas, third Lord Fairfax].

The fall of Colchester (28 Aug.) was followed by a renewal of agitation in the army, and Ireton's regiment was one of the first to petition for the king's trial (Rushworth, vii. 1298). Already a party in the parliament was anxious that the army should interpose to stop the treaty of Newport, but Ludlow found Ireton strongly opposed to premature action. He thought it best ‘to permit the king and the parliament to make an agreement and to wait till they had made a full discovery of their intentions, whereby the people, becoming sensible of their danger, would willingly join to oppose them’ (Ludlow, Memoirs, p. 102). About the end of September Ireton offered to lay down his commission, and desired a discharge from the army, ‘which was not agreed unto’ (Gardiner, Great Civil War, iii. 473–5). For a time he left the headquarters and retired to Windsor, where he is said to have busied himself in drawing up the army remonstrance of 16 Nov. 1648 (reprinted in Old Parl. Hist. xviii. 161). All obstacles to agreement among the officers of the army were removed by the king's rejection of their last overtures. ‘It hath pleased God,’ wrote Ireton to Colonel Hammond, ‘to dispose the hearts of your friends in the army as one man … to interpose in this treaty, yet in such wise both for matter and manner as we believe will not only refresh the bowels of the saints, but be of satisfaction to every honest member of parliament.’ He conjured Hammond, in the national interest, to prevent the king from escaping, and endeavoured to convince him that he ought to obey the army rather than the parliament (Birch, Letters to Hammond, pp. 87, 97). In conjunction with Ludlow he arranged the exclusion of obnoxious members known as ‘Pride's Purge’ ( Memoirs, p. 104). In conjunction with Cromwell he gave directions for bringing the king from Hurst Castle; he sat regularly in the high court of justice, and signed the warrant for the king's execution (Nalson, Trial of Charles I, 1684).

During December 1648 the council of the army was again busy considering a scheme for the settlement of the kingdom, which resulted in the ‘Agreement of the People’ presented to the House of Commons on 20 Jan. 1649 ( Old Parl. Hist. xviii. 516). The first sketch of the ‘Agreement’ was not Ireton's, but by the time it left the council of war it had been revised and amended till it substantially represented his views. While a section in the council held that the magistrate had no right to interfere with any man's religion, Ireton claimed for him a certain power of restraint and punishment. Lilburne complains that Ireton ‘showed himself an absolute king, against whose will no man must dispute’ ( Legal Fundamental Liberties, 1649, 2nd ed. p. 35). Outside the council of war his influence was limited. The levellers hated him as much as they did Cromwell, and denounced both in the ‘Hunting of the Foxes by five small Beagles’ (24 March 1649) and in Lilburne's ‘Impeachment of High Treason against Oliver Cromwell and his son-in-law, Henry Ireton’ (10 Aug. 1649). With the parliament he was, as the chief author of the ‘Agreement,’ far from popular, and though he was added by them to the Derby House Committee (6 Jan. 1649) they refused to elect him to the council of state (10 Feb. 1649).

On 15 June 1649 Ireton was selected to accompany Cromwell to Ireland as second in command, and set sail from Milford Haven on 15 Aug. His division was originally intended to effect a landing in Munster, but the design was abandoned, and he disembarked at Dublin about the end of the month ( Commons' Journals, vi. 234; Murphy, Cromwell in Ireland, p. 74). During Cromwell's illness in November 1649, Ireton and Michael Jones commanded an expedition which captured Inistioge and Carrick, and in February 1650 he took Ardfinnan Castle on the Suir (Carlyle, Cromwell's Letters, cxvi. cxix.). On 4 Jan. 1650 the parliament appointed him president of Munster ( Cal. State Papers, Dom. 1649–50, pp. 476, 502; Commons' Journals, vi. 343). When Cromwell was recalled to England he appointed Ireton to act as his deputy (29 May 1650). Parliament approved the choice (2 July), and appointed Ludlow and three other commissioners to assist Cromwell in the settlement of Ireland ( ib. vi. 343, 479). All Connaught, the greater part of Munster, and part of Ulster still remained to be conquered. Ireton began by summoning Carlow (2 July 1650), which surrendered on 24 July. Waterford capitulated on 6 Aug. and Duncannon on 17 Aug. Half Athlone was taken (September) and Limerick was summoned (6 Oct.), but as the season was too late for a siege it was merely blockaded. Ireton's army went into winter quarters at Kilkenny in the beginning of November (Gilbert, Aphorismical Discovery, iii. 218–25; Borlase, Hist. of the Irish Rebellion, ed. 1743, App. pp. 22–46). The campaign of 1651 opened late. On 2 June Ireton forced the passage of the Shannon at Killaloe, and the next day came before Limerick, which did not capitulate till Oct. 27. In announcing the fall of Limerick he congratulated the parliament that the city had not accepted the conditions tendered it at the beginning of the siege. This obstinacy, he said, had served to the greater advantage of the parliament ‘in point of freedom for prosecution of justice—one of the great ends and best grounds of the war;’ and also ‘in point of safety to the English planters, and the settling and securing of the Commonwealth's interest in this nation’ (Gilbert, iii. 265). Twenty-four persons were excepted from mercy, some on account of their influence in prolonging the resistance, others as ‘original incendiaries of the rebellion, or prime engagers therein’ ( ib. p. 267). Seven of the excepted were immediately hanged, and others reserved for future trial by civil or military courts. Ireton's severity, however, was not indiscriminate. His ‘noble care’ of Hugh O'Neill, the governor of Limerick, is praised by the author of the ‘Aphorismical Discovery’ (iii. 21). He cashiered Colonel Tothill for breaking a promise of quarter made to certain Irish prisoners, and executed two other officers for ‘the killing one Murphy, an Irishman’ (Borlase, App. p. 34; Several Proceedings in Parliament, 31 July–7 Aug. 1651). The distinction he drew between the different classes among his opponents is clearly set forth in his letter of summons to Galway (7 Nov. 1651; Mercurius Politicus, p. 1401). Ireton's policy as to the settlement of Ireland was a continuation of Cromwell's. He regarded the replantation of the country with English colonists as the only means of permanently securing its dependence on England. He ordered the inhabitants of Limerick and Waterford to leave those towns with their families and goods within a period of from three to six months, on the ground that their obstinate adherence to the rebellion and the principles of their religion rendered it impossible to trust them to remain in places of such strength and importance. He promised, however, to show favour to any who had taken no share in the massacres with which the rebellion began, and to make special provision for the support of the helpless and aged (Borlase, p. 345). Toleration of any kind he refused, believing that the catholics were a danger to the state, and that they claimed not merely existence but supremacy. He forbade all officers and soldiers under his command to marry catholic Irishwomen who could not satisfactorily prove the sincerity of their conversion to protestantism (1 May 1651; Several Proceedings in Parliament, p. 1458; Ludlow, Memoirs, p. 145).

In the civil government of Ireland and in the execution of his military duties Ireton's industry was indefatigable. Chief-justice Cooke describes him ‘as seldom thinking it time to eat till he had done the work of the day at nine or ten at night,’ and then willing to sit up ‘as long as any man had business with him.’ ‘He was so diligent in the public service,’ says Ludlow, ‘and so careless of everything that belonged to himself, that he never regarded what clothes or food he used, what hour he went to rest, or what horse he mounted’ ( ib. p. 143). Immoderate labours and neglect of his own health produced their natural result, and after the capture of Limerick Ireton caught the prevailing fever, and died on 26 Nov. 1651. On 9 Dec. parliament ordered him a funeral at the public expense ( Commons' Journals, vii. 115). His body was brought to Bristol, and conveyed to London, where it lay in state at Somerset House, and was interred on 6 Feb. 1652 in Henry VII's Chapel in Westminster Abbey (Chester, Westminster Abbey Registers, p. 522; Cal. State Papers, Dom. 1651–2, pp. 66, 276). His funeral sermon was preached by John Owen, and published under the title of ‘The Labouring Saint's Dismission to his Rest’ (Orme, Life of Owen, p. 139). An elegy on his death is appended to Thomas Manley's ‘Veni, Vidi, Vici’ (12mo, 1652). A magnificent monument was erected with a fervid epitaph, which is printed in Crull's ‘Antiquities of Westminster’ (ed. 1722, ii. App. p. 21). ‘If Ireton could have foreseen what would have been done by them,’ writes Ludlow, ‘he would certainly have made it his desire that his body might have found a grave where his soul left it, so much did he despise those pompous and expensive vanities, having erected for himself a more glorious monument in the hearts of good men by his affection to his country, his abilities of mind, his impartial justice, his diligence in the public service, and his other virtues, which were a far greater honour to his memory than a dormitory amongst the ashes of kings' ( Memoirs, p. 148). On 4 Dec. 1660 The House of Commons ordered the 'carcasses' of Cromwell, Ireton, Bradshaw, and Pride to be taken up, drawn on a hurdle to Tyburn there to be hanged up in their coffins for some time, and after that buried under the gallows ( Commons' Journals, viii. 197). This sentence was carried into effect on 26-30 Jan. 1661 [see Cromwell, Oliver].

The royalist conception of Ireton's character is given by Sir Philip Warwick ( Memoirs, p. 354) and by Clarendon ( Rebellion, xiii. 175). The latter describes him as a man 'of a melancholic, reserved, dark nature, who communicated his thoughts to very few, so that for the most part he resolved alone, but was never diverted from any resolution he had taken, and he was thought often by his obstinacy to prevail over Cromwell, and to extort his concurrence contrary to his own inclinations. But that proceeded only from his dissembling less, for he was never reserved in the communicating his worst and most barbarous purposes, which the other always concealed and disavowed.' According to Ludlow, Ireton was in the last years of his life 'entirely freed from his former manner of adhering to his own opinion,' which had been observed to be his greatest infirmity' ( Memoirs, p. 144). Ludlow's panegyric on the lord deputy expresses the general opinion of his companions in arms. 'We that knew him,' wrote Hewson, 'can and must say truly we know no man like-minded, most seeking their own things, few so singly mind the things of Jesus Christ, of public concernment, of the interest of the precious sons of Zion' ( Several Proceedings in Parliament, 4-11 Dec. 1651). John Cooke describes Ireton's character at length in the preface to 'Monarchy no Creature of God's making' (12mo, 1652), dwelling on his industry, self-denial, love of Justice, godliness, and extraordinary learning. Ireton's disinterestedness was undoubted. On the news that parliament had voted him a reward of 2,000 l. a year he said 'that they had many just debts, which he desired they would pay before they made any such presents; that he had no need of their land, and therefore would not have it, and that he should be more contented to see them doing the service of the nation than so liberal in disposing of the public treasure.' 'And truly,' adds Ludlow, 'I believe he was in earnest' ( Memoirs, p. 143; Commons' Journals, vii. 15). This disinterestedness, combined with the rigid republicanism attributed to Ireton, led to the belief that he would have opposed Cromwell's usurpation, and made him the favourite hero of the republican party (Clarendon, Rebellion, xiii. 175; Life of Col. Hutchinsoh, ii. 185). Portraits of Ireton and his wife by Robert Walker, in the possession of Mr. Charles Polhill, were numbers 785 and 789 in the National Portrait Exhibition of 1866. Engraving are given in Houbraken's 'Illustrious Heads,' and Vandergucht's illustrations to Clarendon's 'Rebellion.' A royalist newspaper, in a pretended hue and cry after Ireton, thus describes his person: ' A tall, black thief with bushy curled hair, a meagre envious face, sunk hollow eyes, a complection between choler and melancholy, a four-square Machiavellian head, and a nose of the fifteens' ( The Man in the Moon, 1-15 Aug. 1649).

Ireton's widow, Bridget Cromwell, married in 1652 General Charles Fleetwood [q. v.], and died in 1662. By her Ireton left one son and three daughters: (l) Henry, married Katharine, daughter of Henry Powle, speaker of the House of Commons in 1689, became lienteuant-colonel of dragoons and gentleman of the horse to William III. He left no issue; (2) Elizabeth, born about 1647, married in 1674 Thomas Polhill Otford, Kent; (3) Jane, born about 1648, married in 1668 Richard Lloyd of London; (4) Bridget, born about 1650, married in 1669 Thomas Bendish (Noble, House of Cromwell, ed. 1787;. ii. 324-46; Waylen, House of Cromwell, 1880, pp. 58, 72; Notes and Queries, 5th ser. vi. 391, and art. supra Bendish, Bridget).

John Ireton (1615-1689), brother of the general, was lord mayor of London in 1658, and was knighted by Cromwell. After the Restoration he was excepted from the Act of Indemnity, and for a time imprisoned in the Tower. In 1662 he was transported to Scilly, was released later, and imprisoned again in 1685 (Noble, i, 445; Cat. State Papers, Dom. 1661-2, p. 460). Another brother, Thomas Ireton, captain in Colonel Rich's regiment in 1645, was seriously wounded at the storming of Bristol (Sprigge, pp. 121, 131).

[Lives of Ireton are contained in Wood's Athenæ Oxon. ad. Bliss, iii. 298; Noble's House of Cromwell, ed. 1787. ii. 319; and Cornelius Brown's Worthies of Notts, 1882, p. 181. The fullest biography is that appended to the Trial of Charles I and of some of the regicides, vol. xxxi. of Murray's Family Library, 1832. Letters by Ireton are printed in Cary's Memorials of the Civil War, 1842; Birch's Letters to Colonel Robert Hammond, 1764; and Nicholls's Original Letters and Papers addressed to Oliver Cromwell, 1743. Borlase's History of the Irish Rebellion, ed. 1743, has a valuable supplement, containing a number of Ireton's letters derived from the papers of his secretary, Mr. Cliffe. For other authorities on his services in Ireland see the bibliography of the article on Oliver Cromwell. The Clarke Papers, published by the Camden Society (vol. i. 1891), throw much light on Ireton's career, and contain reports of his speeches in the council of the army. The Memoirs of Ludlow and the Life of Colonel Hutchinson are of special value for Ireton's Life.]

John Lilburne (1614?–1657)

|

See some pamphlets by John Lilburne.

Dictionary of National Biography entry

Source: Charles Harding Firth, "Lilburne, John," Dictionary of National Biography (1885-1900), vol. 33, pp. 243-50. https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Dictionary_of_National_Biography,_1885-1900/Lilburne,_John

LILBURNE, JOHN (1614?–1657), political agitator, was the son of Richard Lilburne ( d. 1667) of Thickley Puncherdon, Durham, by Margaret, daughter of Thomas Hixon, yeoman of the wardrobe to Queen Elizabeth ( Visitation of Durham, 1615, p. 31; Foster, Durham Pedigrees, p. 215). His father signalised himself as one of the last persons to demand trial by battle in a civil suit (Rushworth, vii. 469). Robert Lilburne [q. v.] was his elder brother. A younger brother, Henry, served in Manchester's army, was in 1647 lieutenant-colonel in Robert Lilburne's regiment, declared for the king in August 1648, and was killed at the recapture of Tynemouth Castle of which be was governor (Rushworth, vii. 1226; Clarke Papers,i. 142,368,419; Carlyle Cromwell, Letter xxxix.) A cousin, Thomas, son of George Lilburne of Sunderland, was a staunch Cromwellian while the Protector lived, but in 1660 assisted Lord Fairfax against Lambert, and thus forwarded the Restoration (Thurloe, vii, 411,436; Cal. State Papers, Dom. 1659-60 p. 294, 1663-4 p. 445; Le Neve, Monumenta Anglieana, ii, 108).

Lilburne was born at Greenwich ( Innocency and Truth Justified, 1645, p. 8). At the close of a letter appended to that pamphlet and dated 11 Nov. 1638, he describes himself as then in his twenty-second year; in the portrait prefixed to another he is described as twenty-three in 1641 ( An Answer to Nine Arguments written by T. B., 1645). The 'Visitation' appears to prove that in each case his age was understated. He was educated at Newcastle and Auckland schools, and then apprenticed by his father to Thomas Hewson, a wholesale cloth merchant in London, with whom he remained from about 1630 to 1636 ( The Legal Fundamental Liberties of the People of England, 1649, 2nd edit., p. 25; Innocency and Truth Justified, p.8). In his spare time he read Foxe's 'Book of Martyrs' and the Puritan divines, and about 1636 became acquainted with John Bastwick, then a prisoner in the Gatehouse. Lilburne'a connection with Bastwick, whose 'Litany' he had a hand in printing, obliged him to fly to Holland. The story that he was Prynne's servant seems to be untrue (Bastwick, Just Defence; Prynne, Liar Confounded, 1646, p. 2; Lilburne, Innocency and Truth, p. 7). On his return from Holland, Lilburne was arrested (11 Dec. 1637) and brought before the Star Chamber on the charge of printing and circulating unlicensed books, more especially Prynne's 'News from Ipswich.' In his examinations he refused to take the oath known as the 'ex-officio' oath—on the ground that he was not bound to criminate himself, and thus called in question the court's usual procedure (see Gardiner, History of England, viii. 248; Stephens, History of the Criminal Law , i. 343). As he persisted in his contumacy, he was sentenced (13 Feb. 1638) to be fined 500 l ., whipped, pilloried, and imprisoned till he obeyed (Rushworth, ii. 463-6; State Trials , iii. 1315-67). On 18 April 1638 Lilburne was whipped from the Fleet to Palace Yard. When he was pilloried he made a speech denouncing the bishops, threw some of Bastwick's tracts among the crowd, and, as he refused to be silent, was finally gagged. During his imprisonment he was treated with great barbarity (Lilburne, The Christian Man's Trial , 1641; A Copy of a Letter written by John Lilburne to the Wardens of the Fleet , 4 Oct. 1640; A True Relation of the Material Passage of Lieutenant-Colonel John Lilburne's as they were proved before the House of Peers , 13 Feb. 1645; State Trials, iii. 1315). He contrived, however, to write and to get printed an apology for separation from the church of England, entitled 'Come out of her, my people' (1639), and an account of his own punishment styled 'The Work of the Beast' (1638).

As soon as the Long parliament met, a petition from Lilburne was presented by Cromwell, and referred to a committee ( Commons' Journals, ii. 24; Memoirs of Sir Philip Warwick, p. 247). On 4 May 1641 the Commons voted that Lilburne's sentence was 'illegal and against the liberties of the subject,' and also 'bloody, wicked, cruel, barbarous, and tyrannical ( ib. ii. 134). The same day Lilburne, who had been released at the beginning of the parliament, brought before the House of Lords for speaking words against the king, but as the witnesses disagreed the charge was dismissed ( Lords' Journals, iv. 233).

When the civil war broke out, Lilburne, who had in the meantime taken to brewing, obtained a captain's commission in Lord Brooke's foot regiment, fought at the battle of Edgehill, and was taken prisoner in the fight at Brentford (12 Nov. 1642; Innocency and Truth Justified, pp. 41, 65). He was then put on his trial at Oxford for high treason in bearing arms against the king, before Chief-justice Heath. Had not parliament, by a declaration of 17 Dec. 1642, threatened immediate reprisals, Lilburne would have been condemned to death (Rushworth, v. 93; A Letter sent from Captain Lilburne, 1643; The Trial of Lieutenant-Colonel John Lilburne, 24-36 Oct. 1619, by Theodorus Varax, pp. 33-9). In the course of 1643 Lilburne obtained his liberty by exchange. Essex gave him 300 l. by way of recognition of his undaunted conduct at his trial, and he says that he was offered a place of profit and honour, but preferred to fight, though it were for eight pence a day, till he saw the peace and liberty of England settled ( Legal Fundamental Liberties, p. 27). Joining Manchester's army at the siege of Lincoln, he took part as a volunteer in its capture, and on 7 Oct. 1643 was given a major's commission in Colonel King's regiment of foot. On 16 May 1644 he was transferred to Manchester's own dragoons with the rank of lieutenant-colonel. He left the army on 30 April 1645), finding that he could not enter the new model without taking the covenant.

Lilburne had gained a great reputation for courage and seems to have been a good officer, but his military career was unlucky. He spent about six months in prison at Oxford, was plundered of all he had at Rupert's relief of Newark (22 March 1644), was shot through the arm at the taking of Walton Hall, near Wakefield (3 June 1644), and received very little pay. His arrears when he left the service amounted to 880 l. ( Innocency and Truth Justified, pp. 25, 43, 46, 69; The Resolved Man's Resolution, p. 32). He also succeeded in quarrelling, first with Colonel King and then with the Earl of Manchester, both of whom he regarded as lukewarm, incapable, and treacherous. He did his beet to get King cashiered, and was one of the authors of the charge of high treason against him, which was presented to the House of Commons by some of the committee of Lincoln in August 1644 ( Innocency and Truth, p.43; England's Birthright 1645, p. 17, The Just Man's Justification ). The dispute with Manchester was due to Lilburne's summoning and capturing Tickhill Castle against Manchester's orders, and Lilburne was one of Cromwell's witnesses in his charge against Manchester ( Cal. State Papers, Dom. 1644- 1645, p. 146; England's Birthright, p. 17; Legal Fundamental Liberties, p. 30).

Besides these feuds Lilburne soon engaged in a quarrel with two of his quondam fellow sufferers. On 7 Jan. 1645 be addressed a letter to Prynne, attacking the intolerance of the presbyterians, and claiming freedom of conscience and freedom of speech for the independents ( A Copy of a Letter to William Prynne upon his last book entitled 'Truth Triumphing over Error,' etc., 1645), Prynne, bitterly incensed, procured a vote of the Commons summoning Lilburne before the committee for examinations (17 Jan. 1645), When he appeared (17 May 1645) the committee discharged him with a caution ( Innocency and Truth Justified, p. 9; The Reasons of Lieutenant-Colonel Lilburne sending his Letter to Mr. Prynne, 1645). A second time (18 June 1645) Prynne caused Lilburne to be brought before the same committee, on a charge of publishing unlicensed pamphlets, but he was again dismissed unpunished. Prynne vented his malice in two pamphlets: 'A Fresh Discovery of prodigious Wandering: Stars and Firebrands, and 'The Liar Confounded,' to which Lilburne replied in 'Innocency and Truth Justified' (1645), Dr. Bastwick took a minor part in the same controversy.

Meanwhile Lilburne was ineffectually endeavouring to obtain from the House of Commons the promised compensation for his sufferings. He procured from Cromwell a letter recommending his case to the house. His attendance, wrote Cromwell, had kept him from other employment, and 'his former losses and late services (which have been very chargeable) considered, he doth find it a hard thing in these times for himself and his family to subsist' ( Innocency and Truth Justified, p. 63). Lilburne hoped also to attract the notice of parliament by giving them a narrative of the victory of Langport, which he had witnessed during his visit to Cromwell ( A more full Relation of the Battle fought between Sir T. Fairfax and Goring made in the House of Commons, 14 July 1645).

But all chance of obtaining what he asked was entirely destroyed by a new indiscretion. On 19 July he was overheard relating in conversation certain scandalous charges against Speaker Lenthall [see Lenthall, William]. King and Bastwick reported the matter to the Commons, who immediately ordered Lilburne's arrest ( Commons' Journals, iv. 213). Brought before the committee for examinations, Lilburne refused to answer the questions put to him unless the cause of his arrest were specified, saying that their procedure was contrary to Magna Charta and the privileges of a freeborn denizen of England ( Innocency and Truth, p. 13; The Liar Confounded, p. 7). In spite of his imprisonment Lilburne contrived to print an account of his examination and arrest, in which he attacked not only several members by name, but the authority of the Commons house itself ( The Copy of a Letter from Lieutenant-Colonel Lilburne to a friend, 1645). The committee in consequence sent him to Newgate (9 Aug.), and the house ordered that the Recorder of London should proceed against him in quarter sessions. The charge against the speaker was investigated, and voted groundless, but no further proceedings were taken against Lilburne, and he was released on 14 Oct. 1645 ( Commons' Journals, iv. 235, 237, 274, 307; Godwin, History of the Commonwealth, ii. 21).

Lilburne was for a short time comparatively quiet. He presented a petition to the Commons for his arrears, but, as he refused to swear to his accounts, could not obtain his pay. His case against the Star-chamber was pleaded before the Lords by Bradshaw, and that house transmitted to the Commons an ordinance granting him 2,000 l. in compensation for his sufferings ( A True Relation of the Material Passages of Lieutenant-Colonel John Lilburne's Sufferings, as they were represented before the House of Peers, 13 Feb. 1645–6; Lords' Journals, viii. 201). But the ordinance hung fire in the Commons, and in the meantime Prynne and the committee of accounts alleged that Lilburne owed the state 2,000 l., and Colonel King claimed 2,000 l. damages for slander. In this dilemma Lilburne wrote and printed (6 June 1647) a letter to Judge Reeve, before whom King's claim was to be tried, explaining his embarrassments and asserting the justice of his cause ( The Just Man's Justification, 4to, 1646). Incidentally he reflected on the Earl of Manchester, observing that if Cromwell had prosecuted his charge properly Manchester would have lost his head. Lilburne was at once summoned before the House of Lords, Manchester himself, as speaker, occupying the chair, but he refused to answer questions or acknowledge the jurisdiction of the peers (16 June). They committed him to Newgate, but he continued to defy them. To avoid obedience to their summons he barricaded himself in his cell, refused to kneel or to take off his hat, and stopped his ears when the charge against him was read. The lords sentenced him to be fined 4,000 l., to be imprisoned for seven years in the Tower, and to be declared for ever incapable of holding any office, civil or military ( Lords' Journals, viii. 370, 388, 428–32; The Freeman's Freedom vindicated; A Letter sent by Lieutenant-Colonel John Lilburne to Mr. Wollaston, keeper of Newgate; The Just Man in Bonds; A Pearl in a Dunghill, 4to, 1646).

On 16 June Lilburne had appealed to the Commons as the only lawful judges of 'a commoner of England,' or 'freeborn Englishman.' On 3 July accordingly the house appointed a committee to consider his case, before which Lilburne appeared on 31 Oct. and 6 Nov., but the business presented so many legal and political difficulties, that their report was delayed ( Anatomy of the Lords' Tyranny … exercised upon John Lilburne ). Lilburne looked beyond the House of Commons, and appealed to the people in a series of pamphlets written by himself, his friend Richard Overton [q. v.], and others ( A Remonstrance of Many Thousand Citizens; Vox Plebis; An Alarum to the House of Lords ). He found time also to attack abuses in the election of the city magistrates, to publish a bitter attack on monarchy, and to quarrel with his gaolers about the exorbitant fees demanded of prisoners in the Tower ( London's Liberty in Chains Discovered, 1646; Regal Tyranny Discovered, 1647; The Oppressed Man's Oppressions Declared, 1647). In the last-named he abused the Commons for delaying his release, and was therefore called before the committee for scandalous pamphlets (8 Feb. 1647). His attitude is shown in the title of a tract published on 30 April 1647: 'The Resolved Man's Resolution to maintain with the last drop of his heart's blood his civil liberties and freedom.' Despairing of help from the House of Commons, Lilburne now appealed to Cromwell and the army ( Rash Oaths Unwarrantable; Jonah's Cry out of the Whale's Belly ). The agitators took up his case and demanded Lilburne's release as one of the conditions of the settlement between the army and parliament ( Clarke Papers, i. 171). When the army marched through London and Fairfax was made lieutenant of the Tower, Lilburne's expectations of immediate release were again disappointed. Though the committee at last reported (14 Sept.), the Commons referred the report back to it again, and appointed a new committee specially to consider the legal questions involved (15 Oct.). Lilburne was allowed to argue his case before the committee (20 Oct.), and on 9 Nov. the Commons ordered that he should have liberty from day to day to come abroad, to attend the committee and to instruct his counsel, without a keeper ( The Grand Plea of Lieutenant-colonel John Lilburne; The Additional Plea; Commons' Journals, v. 301, 334). Before his release Lilburne offered, if he could obtain a reasonable proportion of justice from the parliament, to leave the kingdom and not to return as long as the present troubles lasted ( Additional Plea; Commons' Journals, v. 326; Tanner MSS. lviii. 549). But ever since June his suspicions of Cromwell had been increasing, and he now regarded him as a treacherous and self-seeking intriguer. The negotiations of the army leaders with the king, and the suggestions of royalist fellow-prisoners in the Tower, led him to credit the story that Cromwell had sold himself to the king ( Jonah's Cry; Two Letters by Lilburne to Colonel Henry Marten; The Jugglers Discovered, 1647). Cromwell's breach with the king, in November 1647, which Lilburne attributed solely to the fear of assassination, did not remove these suspicions, and the simultaneous suppression of the levelling party in the army seemed conclusive proof of Cromwell's tyrannical designs. Regardless of his late protestations, Lilburne, in conjunction with Wildman, with the 'agents' representing the mutinous part of the army, and with the commissioners of the levellers of London and the adjacent counties, drew up a petition to the commons, as 'the supreme authority of England,' demanding the abolition of the House of Lords and the immediate concession of a number of constitutional and legal changes. Emissaries were sent out to procure signatures, and mass meetings of petitioners arranged. Information of these proceedings was given to the House of Lords on 17 Jan. 1648, and on their complaint the House of Commons summoned Lilburne to the bar (19 Jan.), and after hearing his lengthy vindication committed him again to the Tower ( Lords' Journals, ix. 663–666; Commons' Journals, v. 436–8; Truth's Triumph, by John Wildman; The Triumph Stained, by George Masterson; A Whip for the present House of Lords, by Lilburne, A Declaration of some proceedings of Lieutenant-colonel John Lilburne and his associates; An Impeachment of High Treason against Oliver Cromwell and Henry Ireton, by Lilburne, 1649). Six months later the presbyterian leaders in the Commons, calling to mind the charge which Lilburne had brought against Cromwell at his last appearance before the house, resolved to set him free. On 27 July Sir John Maynard, one of the eleven members impeached by the army in 1647, set forth his case in a powerful speech. On 1 Aug. the Commons passed a vote for Lilburne's release, and next day the Lords not only followed their example but remitted the fine and sentence of imprisonment which they had imposed two years earlier ( A Speech by Sir John Maynard, 1648; Commons' Journals, v. 657; Lords' Journals, x. 407).

On the day of Lilburne's release Major Huntington laid before the lords his charge against Cromwell. Lilburne states that he was 'earnestly solicited again and again' to join Huntington in impeaching Cromwell, 'and might have had money enough to boot to have done it,' but he was afraid of the consequences of a Scottish victory, and preferred to encourage Cromwell by a promise of support ( Legal Fundamental Liberties, 1649 ed., ii. 32). Nevertheless all Lilburne's actions during the political agitation of the autumn of 1648 were marked by a deep distrust of the army leaders. He refused to take part in the king's trial, and, though holding that he deserved death, thought that he ought to be tried by a jury instead of by a high court of justice. He also feared the consequences of executing the king and abolishing the monarchy before the constitution of the new government had been agreed upon and its powers strictly defined. The constitutional changes demanded by Lilburne and his friends had been set forth in the London petition of 11 Sept. 1648 (Rushworth, vii. 1257), and he next procured the appointment of a committee of sixteen persons—representing the army and the different sections of the republican party—to draw up the scheme of a new constitution. But when the committee had drawn up their scheme, the council of officers insisted on revising and materially altering it. Lilburne, who regarded these changes as a gross breach of faith, published the scheme of the committee (15 Dec.) under the title of 'The Foundations of Freedom, or an Agreement of the People,' and addressed a strong protest to Fairfax ('A Plea for Common Right and Freedom,' 28 Dec. 1648). The council of officers also, on 20 Jan. 1649, presented their revised version of the scheme to parliament, also calling it 'An Agreement of the People' (Gardiner, Great Civil War, iii. 501, 528, 545, 567; Old Parliamentary History, xviii. 516; Legal Fundamental Liberties, pp. 32–42). The difference between the two programmes was considerable, especially with regard to the authority given to the government in religious matters. Moreover, while the officers simply presented the 'Agreement' to parliament for its consideration, Lilburne had intended to circulate it for signature among the people, and to compel parliament to accept it. He now appealed to the discontented part of the army and the London mob, in the hope of forcing the hands of parliament and the council of officers. On 26 Feb. he presented to the parliament a bitter criticism of the 'Agreement' of the officers, following it up (24 March) by a violent attack on the chief officers themselves ( England's New Chains Discovered, pts. i. ii.; answered in 'The Discoverer,' attributed to Frost, the secretary of the council of state). Parliament voted the second part of 'England's New Chains' seditious, and ordered that its authors should be proceeded against (27 March). Lilburne and three friends were brought before the council of state, and after refusing to own its jurisdiction, or answer questions incriminating themselves, were committed to the Tower, 28 March ( The Picture of the Council of State; Commons' Journals, vi. 183; Cal. State Papers, Dom. 1649–50, p. 57). Immediately a number of petitions in Lilburne's favour were presented—one from London, another from ten thousand well-affected persons in the county of Essex, and a third from a number of women ( Commons' Journals, vi. 178, 189, 200). The leaders of the rising which took place in May 1649 threatened that if a hair of the heads of Lilburne and his friends were touched they would avenge it 'seventy times sevenfold upon their tyrants' (Walker, History of Independency, pt. ii. p. 171). Lilburne, whom it seems to have been utterly impossible to deprive of ink, fanned the excitement by publishing an amended version of his constitutional scheme, a vindication of himself and his fellow-prisoners, a controversial tract about the lawlessness of the present government, and a lengthy attack on the parliament ( An Agreement of the Free People of England, 1 May 1649; A Manifestation from Lieutenant-colonel John Lilburne and others, commonly, though unjustly, styled 'Levellers,' 14 April; A Discourse between Lieutenant-colonel John Lilburne and Mr. Hugh Peter, upon May 25, 1649; The Legal Fundamental Liberties of the People of England Vindicated, 8 June 1649). None the less on 18 July the house, at Marten's instigation, ordered Lilburne's release on bail on account of the illness of his wife and children ( Commons' Journals, vi. 164). A compromise of some kind seems to have been attempted and failed, and then on 10 Aug. Lilburne published 'An Impeachment of High Treason against Oliver Cromwell and his Son-in-law, Henry Ireton,' combining the accusations he had made against Cromwell in January 1648 with the charges brought by Huntington in August following. Of more practical importance was a tract appealing to the army to avenge the blood of the late mutineers, which Lilburne personally distributed to some of the soldiers quartered in London ( An Outcry of the Young Men and Apprentices of London, addressed to the Private Soldiers of the Army ). Its immediate result was the mutiny of Ingoldsby's regiment at Oxford in September 1649. On 11 Sept. the parliament voted the 'Outcry' seditious, and ordered immediate preparations for Lilburne's long-delayed trial ( The Moderate, 11–18 Sept. 1649; Commons' Journals, vi. 293). Three days later he was examined by Prideaux, the attorney-general, who reported that there was sufficient evidence to convict him ( Strength out of Weakness, or the Final and Absolute Plea of Lieutenant-colonel John Lilburne; Cal. State Papers, Dom. 1649–50, p. 314). Lilburne himself offered to refer the matter to a couple of arbitrators, or to emigrate to America provided that the money due to him from the state were first paid ( The Innocent Man's First Proffer, 20 Oct.; The Innocent Man's Second Proffer, 22 Oct.).

His trial at the Guildhall by a special commission of oyer and terminer lasted three days (24–26 Oct.) Lilburne began by refusing to plead, and contesting the authority of the court. He was indicted under two recent acts (14 May 1649, 17 July 1649), declaring what offences should be adjudged treason, and his defence was a denial of the facts alleged against him, and an argument that he was not legally guilty of treason. He carried on a continuous battle with his judges, and appealed throughout to the jury, asserting that they were judges of the law as well as the fact, and that the judges were 'no more but cyphers to pronounce their verdict.' Though Judge Jermyn pronounced this 'a damnable blasphemous heresy,' the jury acquitted Lilburne ( Trial of Lieutenant-colonel John Lilburne, by Theodorus Varax, 1649; State Trials, iv. 1270–1470; the legal aspects of the trial are discussed in Stephen, History of the Criminal Law, 1883, i. 356, Willis Bund Selections from the Slate Trials, 1879. i. 602, and Inderwick, The Interregnum, 1891, p. 275). Warned by the popular rejoicings, the council of state accepted the verdict, and released Lilburne and his associates (8 Nov. 1649).

So far as politics was concerned, Lilburne for the next two years remained quiet. He was elected on 21 Dec. 1649 a common councilman for the city of London, but on the 26th his election was declared void by parliament, although he had taken the required oath to be faithful to the commonwealth ( Commons' Journal, vi. 338; The Engagement Vindicated and Explained ). No disposition, however, was shown to persecute him. On 22 Dec, 1648 he had obtained an ordinance granting him 3,000 l, in compensation for his sufferings, from the Star-chamber, the money being made payable from the forfeited estates of various royalists in the county of Durham. As this source had proved insufficient, Lilburne, by the aid of Marten and Cromwell, obtained another ordinance (30 July 1650), charging the remainder of the sum on confiscated chapter-lands, and thus became owner of some of the lands of the Durham chapter ( Commons' Journals, i. 441, 447).

Now that his own grievance was redressed, he undertook to redress those of other people. Ever since 1644, when he found himself prevented by the monopoly of the merchant adventurers from embarking in the cloth trade, Lilburne had advocated the release of trade from the restrictions of chartered companies and monopolists ( Innocency and Truth Justified, p. 43; England's Birthright Justified, p. 9). He now took up the case of the soap-makers, and wrote petitions for them demanding the abolition of the excise on soap, and apparently became a soap manufacturer himself ( The Soapmaker' Complaint for the Loss of their Trade, 1650). The tenants of the manor of Epworth hold themselves wronged by enclosures which had taken place under the schemes fur draining Hatfield Chase and the Isle of Axholme. Lilburne took up their cause, assisted by his friend, John Wildman, and headed a riot (19 Oct. 1650), by means of which the commoners sought to obtain possession of the disputed lands. His zeal was not entirely disinterested, as he was to have two thousand acres for himself and Wildman if the claimants succeeded ( The Case of the Tenants of the Manor of Epworth, by John Lilburne, 18 Nov. 1650; Two Petitions from Lincolnshire against the Old Court Levellers; Lilburne Tried and Cast, pp. 83–90; Tomlinson, The Level of Hatfield Chace, pp. 91, 258–76; Cal. State Papers, Dom. 1652–3. p. 373). John Morris, alias Poyntz, complained of being swindled out of some properties by potent enemies, with the assistance of John Browne, late clerk to the House of Lords. Lilburne, who had exerted himself on behalf of Morris as far back as 1648. now actively took up his cause again ( A Whip for the Present House of Lords, 27 Feb. 1647–8; The Case of John Morris, alias Poyntz, 29 June 1651).

Much more serious in its consequences was Lilburne's adoption of the quarrel of his uncle, George Lilburne, with Sir Arthur Hesilrige. In 1649, Lilburne had published a violent attack on Hesilrige, whom he accused of obstructing the payment of the money granted him by the parliamentary ordinance of 28 Dec. 1648 ( A Preparative to an Hue and Cry after Sir Arthur Haslerig, 18 Aug, 1649). George Lilburne's quarrel with Hesilrige was caused by a dispute about the possession of certain collieries in Durham—also originally the property of royalist delinquents— from which he had been ejected by Hesilrige in 1649. In 1651 the committee for compounding delinquents' estates had confirmed Hesilrige's decision. John Lilburne intervened with a violent attack on Hesilrige and the committee, terming them 'unjust and unworthy men, fit to be spewed out of all human society, and deserving worse than to be hanged' ( A just Reproof to Haberdashers' Hall, 30 July 165l). He next joined with Josiah Primat—the person from whom George Lilburne asserted that he had bought the collieries—and presented to parliament, on 23 Dec. 1651, a petition repeating and specifying the charges against Hesilrige. Parliament thereupon appointed a committee of fifty members to examine witnesses and documents; who reported on 16 Jan. 1653, that the petition was 'false, malicious, and scandalous.' Lilburne was sentenced to pay a fine of 3,000 l, to the state, and damages of 2,000 l, to Hesilrige, and 500 l. apiece to four members of the committee for compounding. In addition he was sentenced to be banished for life, and an act of parliament for that purpose was passed on 30 Jan. ( Commons' Journals, vii. 55, 71, 78; Calendar of the Proceedings of the Committee for compounding, pp. 1917, 2127, An Anatomy of Lieutenant-colonel J. Lilburne's Spirit, by T. M. 1649; Lieutenant-colonel J. Lilburne Tried and Cast, 1653; A True Narrative concerning Sir A. Hesilrige's possessing of Lieutenant-colonel J. Lilburne's estate, 1653).

Lilburne spent his exile in the Netherlands at Bruges and elsewhere, where he published a vindication of himself, and an attack on the government ( Lieutenant-colonel John Lilburne's Apologetical Narrative, relating to his illegal and unjust sentence, Amsterdam, April 1652 printed in Dutch and English; As you were, May 1652). In his hostility to the army leaders Lilburne had often contrasted the present governors unfavourably with Charles I. Now he frequented the society of cavaliers of note, such Lords Hopton, Colepeper, and Percy. If he were furnished with ten thousand pounds, he undertook to overthrow Cromwell, the parliament, and the council of state, within six months. 'I know not.' he was heard to say, 'why I should not vye with Cromwell, since I had once as great a power as he had, and greater too, and am as good a gentleman.' But with the exception of the Duke of Buckingham, non of the royalists placed any confidence in him. ( Several informations taken concerning Lieutenant-colonel John Lilburne, concerning his apostacy to the party of Charles Stuart, 1653; Malice detected in printing certain Information, etc.; Lieutenant-colonel John Lilburne received ; Cal. Clarendon Papers , ii. 141, 146, 213). The news of the expulsion of the Rump in April 1653 excited Lilburne's hopes of returning to England. Counting on Cromwell's placable disposition, he boldly applied to him for a pass to return to England, and, when it was not granted, came over without one (14 June). The government at once arrested him, and lodged him in Newgate, whence he continued to importune Cromwell for his protection, and to promise to live quietly if he might stay in England ( A Defensive Deceleration of Lieutenant-colonel John Lilburne, 22 June 1653; Mercurius Politicus, pp. 2515, 2525, 2529; Cal. State Papers, Dom. 1652-3, pp. 410, 415, 436). His trial began at the Old Bailey on 13 July, and concluded with his aquittal on 20 Aug. As usual Lilburne contested every step with the greatest pertinacity. 'He performed the great feat which no one else ever achieved, of extorting from the court a copy of his indictment, in order that he might put it before counsel, and be instructed as to the objections he might take against it' (Stephen, History of the Criminal Law , i. 367; State Trials , v. 407-460, reprints Lilburne's own account of the trial, and his legal pleas; see also Godwin, iii. 554). Throughout the trial popular Sympathy was on his side. Petitions on his behalf were presented to parliament, so strongly worded that the petitioners were committed to prison. Crowds flocked to see him tried; threats of a rescue were freely uttered; and tickets were circulated with the legend:

And what, shall then honest John Lilburne die?

Three-score thousand will know the reason why.

The government filled London with troops, but in spite of their officers, the soldiers shouted and sounded their trumpets when they heard that Lilburne was acquitted ( Commons' Journals, vii. 285, 294 ; Thurloe Papers, i. 367,429, 435, 441; Clarendon, Rebellion, xiv. 52; Cal. Clarendon Papers, ii. 237, 246). The government, however, declined to leave Lilburne at large. T0.0he jurymen were summoned before the council of state, and the council of state was ordered to secure Lilburne. On 28 Aug. he was transferred from Newgate to the Tower, and the lieutenant of the Tower was instructed by parliament to refuse obedience to any writ of Habeas Corpus ( Commons' Journals, vii. 306, 309, 358; Cal. State Papers, Dom. 1653-4, pp. 98-102; A Hue and Cry after the Fundamental Laws and Liberties of England ). Consequently Lilburne's attempt to obtain such a writ failed ( Clavis Aperiendum Carceris, by P. V., 1654). On l6 March 1654, the council ordered that he should be removed to Mount Orgueil Castle, Jersey; and he was subsequently transferred to Elizabeth Castle, Guernsey. Colonel Robert Gibbon, the governor, complained that he gave more trouble than ten cavaliers. The Protector offered Lilburne his liberty if he would engage not to act against the government, but he answered that he would own no way for his liberty but the way of the law ( Cal. Sate Papers, Dom. 1654, pp. 33,46; Thurloe Papers, iii. 512, 629). Lilburne's health suffered from his confinement, and in 1654 his death was reported and described ( The Last Will and Testament of Lieutenant-colonel John Lilburne ). His wife and father petitioned for his release, and in Oct. 1655 he was brought back to England and lodged in Dover Castle ( Cal. State Papers, Dom. 1655, pp. 263, 556), Immediately after his return, he declared himself a convert to the tenets of the Quakers, and announced his conversion in a letter to his wife. General Fleetwood showed a copy of this letter to the Protector, who was at first inclined to regard it merely as a politic device to escape imprisonment. When Cromwell was convinced that Lilburne really intended to live peaceably, he released him from prison, and seems to have continued till his death the pension of 40's'. a week allowed him for his maintenance during his imprisonment ( The Resurrection of John Lilburne, now a prisoner in Dover Castle , 1656 Cal. Stat Papers , Dom. 1656-7, p.21). He died at Eltham 29 Aug. 1657, and was buried at Moorfields, 'in the new churchyard adjoining to Bedlam' ( Mercurius Politictus, 27 Aug.-3 Sept, 1657).

Lilburne married Elizabeth, daughter of Henry Dewell. During his imprisonment in 1649 he lost two sons, but a daughter and other children survived him ( Biographia Britannica, p. 2957; Thurloe, iii. 512). On 21 Jan. 1659 Elizabeth Lilburne petitioned Richard Cromwell for the discharge of the fine imposed on her husband by the act of 30 Jan. 1652, and her request was granted. Parliament on a similar petition recommended the repealing of the act, and the recommendation was carried by the restored Long parliament, 15 Aug. 1659 ( Cal. State Papers, Dom. 1658-9, p. 260; Commons' Journals, vii. 600, 608, 760).

Lilburne's political importance is easy to explain. In a revolution where others argued about the respective rights of thing and parliament, he spoke always of the rights of the people. His dauntless courage and his powers of speech made him the idol of the mob. With Coke's 'Institutes' in his hand he was willing to tackle any tribunal. He was ready to assail any abuse at any cost to himself, but his passionate egotism made him a dangerous champion, and he continually sacrificed public causes to personal resentments. It would be unjust to deny that he had a real sympathy with sufferers from oppression or misfortune; even when he was himself an exile he could interest himself in the distresses of English prisoners of war, and exert the remains of his influence to get them relieved ( Letter to Henry Marten, 8 Sept. 1652, MSS of Captain Loder-Symonds, but cf. The Upright Man's Vindication, 1 Aug. 1653; Lieut.-col. John Lilburne Tried and Cast ). In his controversies he was credulous, careless about the truth of his charges, and insatiably vindictive. He attacked in turn all constituted authorities—lords, commons, council of state, and council of officers—and quarrelled in succession with every ally. A life of Lilburne published in 1657 supplies this epitaph:

Is John departed, and is Lilburne gone!

Farewell to Lilburne, and farewell to John...

But lay John here, lay Lilburne here about,

For if they ever meet they will fall out.

A similar saying is attributed by Anthony Wood to 'magnanimous Judge Jenkins.'

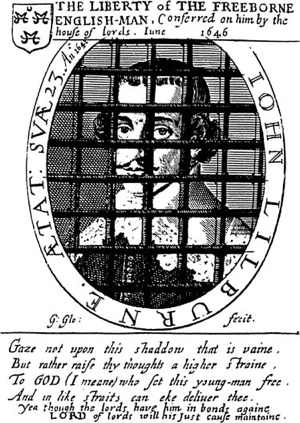

There are the following contemporary portraits of Lilburne; (1) an oval, by G. Glover, prefixed to 'The Christian Man's Trial.' 1641. (2) the same portrait republished in 1646, with prison bars across the face to represent Lilburne's imprisonment. (3) a full length representing Lilburne' pleading at the bar with Coke's 'Institutes' in his hand; prefixed to 'The Trial of Lieut.-col. John Lilburne, by Theodorus Varax,' 1649.

[A bibliographical list of Lilburne's pamphlets compiled by Mr. Edward Peacock, is printed in Notes and Queries for 1898. Most of them contain autobiographical matter. The earliest life of Lilburne is The Self-Afflicter lively Described, 8vo, 1657; the beat is that contained in Biographia Britannica, 1760, v. 2337-61. Other lives are contained in Wood's Athenæ Oxon. and Guizot's Portraits Politiques des Hommes des differents Partis, 1651. Godwin, in his History of the Commonwealth, 1824, traces Lilburne's career with great care. Other authorities are cited in the text.]

Richard Overton (fl. 1646)

See some pamphlets by Richard Overton.

Dictionary of National Biography entry

Source: Charles Harding Firth, "Overton, Richard," Dictionary of National Biography (1885-1900), vol. 42, pp. 385-87. <https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Dictionary_of_National_Biography,_1885-1900/Overton,_Richard>

OVERTON, RICHARD ( fl. 1646), pamphleteer, was probably a relative of Henry Overton, a printer, who began to publish in 1629, and had in 1642 a shop in Pope's Head Alley, London (Arber, Stationers' Register, iv. 218, 494; Lemon, Catalogue of Broadsides in the possession of the Society of Antiquaries ). Richard Overton probably spent part of his early life in Holland (B. Evans, Early English Baptists, i. 254). He began publishing anonymous attacks on the bishops about the time of the opening of the Long parliament, together with some pungent verse satires, like 'Lambeth Fayre' and 'Articles of High Treason against Cheapside Cross,' 1642.

Overton turned next to theology, and wrote an anonymous tract on 'Man's Mortality,' 4to, 1643. This he described as 'a treatise wherein 'tis proved, both theologically and philosophically, that whole man (as a rational creature) is a compound wholly mortal, contrary to that common distinction of soul and body: and that the present going of the soul into heaven or hell is a mere fiction; and that at the resurrection is the beginning of our immortality, and then actual condemnation and salvation, and not before.' Eccl. iii. 19 is quoted as a motto, and the tract is signed 'R. O.,' and said to be 'printed by John Canne' [q. v.] at Amsterdam. According to Thomason's note in the British Museum copy, it appeared on 19 Jan. 1643–4, and was really printed in London (Masson, Life of Milton, iii. 156). The tract made a great stir, and a small sect arose known as 'soul sleepers,' who adopted Overton's doctrine in a slightly modified form (Pagitt, Heresiography, ed. 1662, p. 231). On 26 Aug. 1644 the House of Commons, on the petition of the Stationers' Company, ordered that the authors, printers, and publishers of the pamphlets against the immortality of the soul and concerning divorce should be diligently inquired for, thus coupling Overton with Milton as the most dangerous of heretics (Masson, iii. 164; Commons' Journals, iii. 606). Daniel Featley [q. v.] in the 'Dippers Dipt' and Thomas Edwards (1599–1647) [q. v.] in 'Gangræna' (i. 26) both denounced the unknown author, the latter asserting that Clement Wrighter [q. v.] 'had a great hand in the book.'

Meanwhile Overton had commenced a violent onslaught against the Westminster assembly, under the pseudonym of 'Martin Marpriest,' who was represented as the son of Martin Marprelate, the antagonist of the Elizabethan bishops. The series of tracts he issued under this name, of which the chief are 'The Arraignment of Mr. Persecution,' 'Martin's Echo,' and 'A Sacred Synodical Decretal,' were published clandestinely in 1646, with fantastic printers' names appended to them. The 'Decretal' is a supposed order of the Westminster assembly for the author's arrest, purporting to be 'printed by Martin Claw-Clergy, printer to the reverend Assembly of Divines, for Bartholomew Bang-priest, and are to be sold at his shop in Toleration Street, at the sign of the Subjects' Liberty, right opposite to Persecuting Court.' Prynne denounced these tracts to the parliament as the quintessence of scurrility and blasphemy, and demanded the punishment of the writer, whom he supposed to be Henry Robinson ( A Fresh Discovery of some Prodigious New Wandering Blazing Stars, 1645, p. 9). Overton's authorship was suspected, but could not be proved ( A Defiance against all Arbitrary Usurpations, 4to, 1646, p. 25). He did not own his responsibility till 1649, when the assembly of divines had come to an end ( A Picture of the Council of State, 4to, 1649, p. 36).

In 1646 Overton, who had been concerned in printing some of Lilburne's pamphlets, took up his case against the lords, and published 'An Alarum to the House of Lords against their Insolent Usurpation of the common Liberties and Rights of this Nation, manifested in their Attempts against Lieutenant-colonel John Lilburne,' 4to, 1646. For this he was arrested by order of the house on 11 Aug. 1646, and, refusing to acknowledge their jurisdiction, was committed to Newgate ( Lords' Journals, viii. 457; Hist. MSS. Comm. 6th Rep. pp. 46, 130). But, in spite of his confinement, he contrived to publish a narrative of his arrest, entitled 'A Defiance against all Arbitrary Usurpations,' and a still more violent attack on the peers, called 'An Arrow shot from the Prison of Newgate into the Prerogative Bowels of the Arbitrary House of Lords.' His wife Mary and his brother Thomas were also imprisoned for similar offences ( ib. p. 172; Lords' Journals, viii. 645, 648; The Petition of Mary Overton, Prisoner in Bridewell, to the House of Commons, 4to, 1647).

The army took up the cause of Overton and his fellow prisoners, and demanded that they should be either legally tried or released ( Clarke Papers, i. 171; Old Parliamentary History, xvi. 161). He was unconditionally released on 16 Sept. 1647 ( Lords' Journals, ix. 436, 440). This imprisonment did not diminish Overton's democratic zeal. He had a great share in promoting the petition of the London levellers (11 Sept. 1648). He was also one of those who presented to Fairfax on 28 Dec. 1648 the 'Plea for Common Right and Freedom,' a protest against the alterations made by the council of the army in Lilburne's draft of the Agreement of the People. On 28 March 1649 he was arrested, with Lilburne and two other leaders of the levellers, as one of the authors of 'England's new Chains Discovered.' Overton, who refused to acknowledge the authority of the council of state or to answer their questions, was committed to the Tower ( A Picture of the Council of State, 1649, pp. 25–45; Commons' Journals, vi. 174, 183; Cal. State Papers, Dom. 1649–50, pp. 57–9). In conjunction with his three fellow-prisoners he issued on 1 May 1649 the 'Agreement of the Free People of England,' followed on 14 April by a pamphlet denying the charge that they sought to overthrow property and social order ( A Manifestation from Lieutenant-colonel John Lilburne, Mr. Richard Overton, and others, commonly, though unjustly, styled Levellers, 4to, 1649).

On his own account he published on 2 July a 'Defiance' to the government, in the form of a letter addressed 'to the citizens usually meeting at the Whalebone in Lothbury, behind the Royal Exchange,' a place which was the headquarters of the London levellers. The failure of the government to obtain a verdict against Lilburne involved the release of his associates, and on 8 Nov. Overton's liberation was ordered ( Cal. State Papers, Dom. 1649–50, p. 552). The only condition was that he should take the engagement to be faithful to the Commonwealth, which he probably had no hesitation in doing. In September 1654 Overton proposed to turn spy, and offered his services to Thurloe for the discovery of plots against the Protector's government. In the following spring he was implicated in the projected rising of the levellers, and fled to Flanders in company with Lieutenant-colonel Sexby. There, through the agency of Sir Marmaduke (afterwards Lord) Langdale [q. v.], he applied to Charles II, and received a commission from him. Some months later he returned to England, supplied with Spanish money by Sexby, and charged to bring about an insurrection ( Thurloe State Papers, ii. 590, vi. 830–3; Cal. Clarendon Papers, iii. 55; Egerton MS. 2535, f. 396). Overton's later history is obscure. He was again in prison in December 1659, and his arrest was ordered on 22 Oct. 1663, apparently for printing something against the government of Charles II ( Commons' Journals, vii. 800; Cal. State Papers, Dom. 1663–4, p. 311).

It is difficult to give a complete list of Overton's works, as many are anonymous. The chief are the following: 1. 'New Lambeth Fair newly Consecrated, wherein all Rome's Relics are set at sale' (a satire in verse), 1642. 2. 'Articles of High Treason exhibited against Cheapside Cross, with the last Will and Testament of the said Cross' (a satire in verse), 1642. 3. 'Man's Mortality,' Amsterdam, 1643; a second and enlarged edition was published in 1655, in 8vo, entitled 'Man wholly Mortal.' 4. 'The Arraignment of Mr. Persecution … by Reverend young Martin Marpriest,' 1645. 5. 'A Sacred Synodical Decretal for the Apprehension of Martin Marpriest,' 1645. 6. 'Martin's Echo; or a Remonstrance from his Holiness, Master Marpriest' [about 1645]. 7. 'An Alarum to the House of Lords,' 1646. 8. 'A Defence against all arbitrary Usurpations, either of the House of Lords or any other,' 1646. 9. 'An Arrow against all Tyrants or Tyranny,' 1646. 10. 'The Commoners' Complaint,' 1646. 11. 'The Outcries of oppressed Commons' (by Lilburne and Overton jointly), 1647. 12. 'An Appeal from the Degenerate Representative Body, the Commons of England, assembled at Westminster, to the … Free People in general, and especially to his Excellency, Sir Thomas Fairfax,' 1647. 13. 'The Copy of a Letter written to the General from Lieutenant-colonel Lilburne and Mr. Overton on behalf of Mr. Lockyer,' 1649. 14. 'A Picture of the Council of State' (by Overton and three others), 1649. 15. 'A Manifestation of Lieutenant-colonel Lilburne and Mr. Overton, etc.,' 1649. 16. 'An Agreement of the Free People of England tendered as a Peace-offering to this distressed Nation, by Lieutenant-colonel Lilburne, Mr. Overton, etc.,' 1649. 17. 'Overton's Defiance of Act of Pardon,' 1649. 18. 'The Baiting of the Great Bull of Bashan,' 1649. There are also a number of petitions addressed by Overton to the two houses of parliament.

[Brit. Mus. Cat.; authorities cited in the article.]

Thomas Rainborow (or Rainborowe, or Rainsborough) ( d. 1648)

Dictionary of National Biography entry

Source: Charles Harding Firth, “Rainborow, Thomas” Dictionary of National Biography (1885-1900), pp. 172-73. <https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Dictionary_of_National_Biography,_1885-1900/Rainborow,_Thomas>