[William Walwyn], Englands Lamentable Slaverie (11 October, 1645).

For further information see the following:

- This is part of the Leveller Collection of Tracts and Pamphlets Project.

- some biographical information about William Walwyn (1600-1680)

- a full list of the Leveller Tracts and Pamphlets in chronological order

Bibliographical Information

ID Number

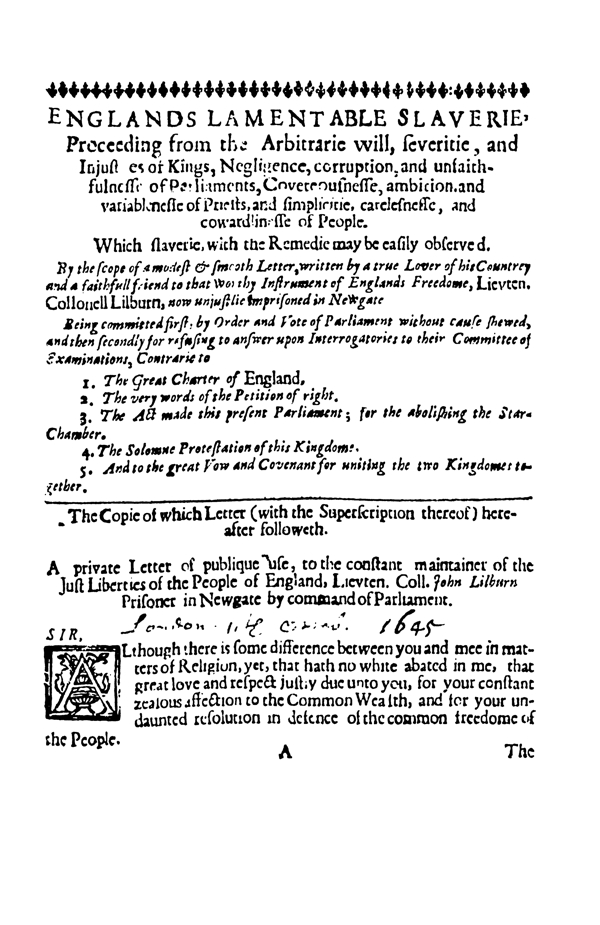

T.50 [1645.10.11] [William Walwyn], Englands Lamentable Slaverie Proceeding from the Arbitrarie will, severitie, and Injustices of Kings, Negligence, corruption, and unfaithfulnesse of parliaments (11 October, 1645).

Full title

[William Walwyn], Englands Lamentable Slaverie Proceeding from the Arbitrarie will, severitie, and Injustices of Kings, Negligence, corruption, and unfaithfulnesse of parliaments, Covetousnesse, ambition, and variablenesse of priests, and simplicitie, carelessnesse, and cowardlinesse of People. Which slaverie, with the Remedie may be easily observed. By the scope of a modest & smooth letter, written by a true Lover of his Countrey and a faithful friend to that Worthy Instrument of Englands Freedome, Lieuten. Collonell Lilburn, now unjustly imprisoned in Newgate. Being committed first, by Order and Vote of parliament without cause Shewed, and then secondly for refusing to answer some Interrogatories to their Committee of Examinations, Contrarie to

1. The Great Charter of England.

2. The very words of the Petition of right.

3. The Act made this present parliament; for the abolishing the Star Chamber.

4. The Solemne Protestation of this Kingdom.

5. And to the great Vow and Covenant for uniting the two kingdomes together.

The pamphlet contains the following parts:

- Letter

- The Printer to the Reader

Estimated date of publication

11 October, 1645.

Thomason Tracts Catalog information

TT1, p. 400; Thomason E.304 (18).

Editor’s Introduction

(Placeholder: Text will be added later)

Text of Pamphlet

Although there is some difference between you and mee in matters of Religion, yet, that hath no while abated in me, that great love and respect justly due unto you, for your constant zealous affection to the Common Wealth, and for your undaunted resolution in defence of the common freedome of the People.

The craft and delusion of those that would master and controle the People, hath not availed (by fomenting our differences in Religion, which is their common practice) to make me judge preposterously, either of your or any other mens sufferings.

We have a generall caution, that no man suffer as an evill doer; but if any suffer for well doing, who are they that would be thought Christians, and can exempt themselves from suffering with them? No certainly, it is neither pettie differences in opinions, nor personall frailties in sufferers, nor both, that can acquite or excuse us in the sight of God so we are not simplie to be spectators or beholders of them afar off (as too many doe) but if one suffer, all ought to suffer with that one, even by having a sympathie and fellow feeling of his miserie, and helping to beare his burden; so that he may be eased in the day of tentation; yea and the sentences both of absolution and condemnation shall be pronounced at the great day, according to the visiting or not visiting of Prisoners, and hearing of their mourning, sighs, and groanes.

This is my judgement, from whence hath issued this my practice, that when I heare of the sufferings of any man, I doe not enquire, what his judgement is in Religion, nor doe I give eare to any tales or reports of any mans personall imperfection (being privie to mine owne) but I presently labour to be rightly informed of the cause of his sufferings (alledged against him) whether that be evill or good, and of the proceedings thereupon, whether legall or illegall, just or unjust.

And this hath been my course and practice in things of that nature for almost a score of yeares, whoever have been the Judges, whether Parliament, King, Counsell-board, Starr-Chamber, High Commission, Kings-bench, or any Judicatory, yea what ever the accuser, or the accused, the judgement or punishment hath been; I have taken this my just and necessary liberty; for having read, observed, debated, and considered both ancient and latter times the variations and changes of Governments and Governors, and looking upon the present with an impartiall judgement, I still find a necessity of the same my accustomed watchfullnesse, it never being out of date; [the more my hearts griefe] for worthy and good men (nay the most publique spirited men) to suffer for well doing, unto whom only is promised the blessing and the heavenly Kingdome: Mat. 5. 10.

Your suffering at present, is become every good mans wonder, for they all universally conclude your faithfulnesse and zeale to the publique weale to be such, as no occasion or temptation could possibly corrupt, and the testimonies you have given thereof to be so great, as greater could not be.

They observe likewise, the large testimonie given of your deserts, by your honourable and worthy Friend in the Armie, Lieuten. Generall Cromwell.

And therefore, that you should now be kept in safe custodie, was very sad newes to all that love you; knowing how impossible it was, to make you flee or start aside; but when they heard that you were sent to that reproachfull prison of Newgate, they were confounded with griefe.

It should seeme, that you being questioned by the Committee of Examinations stood upon your old guard alledging it to be against your liberty, as you were a free borne Englishman, to answer to questions against your selfe, urging MAGNA CHARTA to justifie your so doing; And complaining that contrary to the said Charter, you had beene divers times imprisoned by them.

Now it is not much to be wondred at, that this your carriage should be very offensive unto them; for you were not the first by divers, (whom I could name) that have been examined upon questions, tending to their own accusation and imprisonment too, for refusing to answer, but you are the first indeed, that ever raised this new doctrine of MAGNA CHARTA, to prove the same unlawfull.

Likewise, You are the first, that compareth this dealing to the crueltie of the Starre Chamber, and that produced the Vote of this Parliament against those cruelties (so unjustly inflicted on your selfe by that tyrannous Court) And how could you Imagine this could be indured by a Committee of Parliament? No, most Parliament men are to learne what is the just power of a Parliament, what the Parliament may doe, and what the Parliament (it selfe) may not doe. It’s no marvell then that others are ignorant, very good men there be; who affirm, that a Parliament being once chosen, have power over all our lives estates and liberties, to dispose of them at their pleasure whether for our good or hurt, All’s one (say they) we have trusted them, and they are bound to no rules, nor bounded by any limits, but whatsoever they shall ordaine, binds all the people, it’s past all dispute, they are accountable unto none, they are above MAGNA CHARTA and all Lawes whatsoever, and there is no pleading of any thing against them.

Others there are (as good wise and juditious men) who affirme, that a Parliamentary authority is a power intrusted by the people (that chose them) for their good, safetie, and freedome; and therefore that a Parliament cannot justlie doe any thing to make the people lesse safe or lesse free then they found them: MAGNA CHARTA (you must observe) is but a part of the peoples rights and liberties, being no more but what with much striving and fighting, was by the blood of our Ancestors, wrestled out of the pawes of those Kings, who by force had conquered the Nation, changed the lawes and by strong hand held them in bondage.

For though MAGNA CHARTA be so little as lesse could not be granted with any pretence of freedome, yet as if our Kings had repented them of that little, they alwaies strove to make it lesse, wherein very many times they had the unnaturall assistance of Parliaments to helpe them: For Sir, if we should read over all the hudge volume of our Statutes, we might easily observe how miserablie Parliaments assembled, have spent most of their times, and wee shall not find one Statute made to the enlargement of that streight bounds, deceitfully and improperlie called MAGNA CHARTA, (indeed so called to blind the people) but if you shall observe and marke with your pen, every particular Statute made to the abridgement of MAGNA CHARTA, you would make a very blotted booke, if you left any part unblotted.

Sometimes you shall find them very seriously imployed, about letting loose the Kings prerogatives, then denominating what should be Treason against him (though to their owne vexation and continuall danger of their lives) sometimes enlarging the power of the Church, and then againe abridging the same, sometimes devising punishments for Heresie, and as zealous in the old grossest superstitions, as in the more refined and new, but ever to the vexation of the people.

See how busie they have been about the regulating of petty inferiour trades and exercises, about the ordering of hunting, who should keep Deere and who should not, who should keep a Greayhound, and who a Pigeon-house, what punishment for Deere stealing, what for every Pidgeon killed, contrary to law, who should weare cloth of such a price, who Velvet, Gold, and Silver, what wages poore Labourers should have, and the like precious and rare businesse, being most of them put on of purpose to divert them from the very thoughts of freedome, suitable to the representative body of so great a people.

And when by any accident or intollerable oppression they were roosed out of those waking dreames, then whats the greatest thing they ayme at? Hough with one consent, cry out for MAGNA CARTA, (like great is Diana of the Ephesians) calling that messe of pottage their birthright, the great inheritance of the people, the great Charter of England.

And truly, when so choice a people, (as one would thinke Parliaments could not faile to be) shall insist upon such inferiour things, neglecting greater matters, and be so unskilfull in the nature of common and just freedom, as to call bondage libertie, and the grants of Conquerours their Birth-rights, no marvaile such a people make so little use of the greatest advantages; and when they might have made a newer and better Charter, have falne to patching the old.

Nor are you to blame others for extolling it, that are tainted therewith your selfe, (saving only that its the best we have) Magna Charta hath been more precious in your esteeme then it deserveth; for it may be made good to the people, and yet in many particulars, they may remaine under intolerable oppressions, as I could easily instance: And if there be any necessity on your behalfe, it shall not faile (with Gods grace) to be effected, let who so will be offended, but if there be not a necessity, I conceive it better (for this present age) to be concealed, then any wise divulged.

But in this point you are very cleare, that the parliament ought to preserve you in the Freedomes and liberties contained in Magna Charta at the least, and they are not to permit any authority or Jurisdiction whatsoever to abridge you or any man thereof, much lesse may they be the doers thereof themselves: Something may be done through misinformation, but believe it, upon consideration, they are to make amends. Humanum est errare.

But as Abraham reasoning with God, was bold to say to that Almighty power, Shall not the Judge of all the earth doe right? Much more may I in this your case be bold to say, shall not the Supreame Judicatory of the Common Wealth doe right? God forbid.

That libertie and priviledge which you claime is, as due unto you, as the ayre you breath in; for a man to be examined in crimminall cases against himselfe and to be urged to accuse himselfe is as unnaturall and unreasonable, as to urge a man to kill himselfe, for though it be not so high a degree of wickednesse, yet it is as really wicked.

And for any man to be imprisoned without cause declared, and witnessed (by more then one appearing face to face) is not only unjust, because expreslie against Magna Charta (both of Heaven and Earth) but also against all reason, sense, and the common Law of equitie and justice.

Now in such cases as these, no authoritie in the world can over-rule with out palpable sinne; It is not in these cases as it is in other things contained in Magna Charta, such as are the freedomes of the Church therein mentioned for some doe argue that their power must be above Magna Charta, or otherwise they would not justlie alter the Government of the Church, by ArchBishops and Bishops, who have their foundation in Magna Charta.

But such are to consider, that the Government of the Church is a thing disputable, and uncertaine, and was alwaies burthensome to the people: now unto things in themselves disputable and uncertaine, as there is no reason why any man should be bound expresly to any one forme, further then his Judgement and conscience doe agree thereunto, even so ought the whole Nation to be free therein, even to alter and change the publique forme, as may best stand with the safety and freedome of the people. For the Parliament is ever at libertie to make the People more free from burthens and oppressions of any nature, but in things appertaining to the universall Rules of common equitie and justice, all men and all Authority in the world are bound.

This Parliament was preserved and established, by the love and affections of the people because they found themselves in great bondage and thraldome both spirituall and temporall; out of both which, the Parliament proposed to deliver them in all their endeavours, at least Declarations, wherein never was more assistance given by a people.

And for the first, it was a great thing, the exterpation of Episcopacie, but that meerly is not the main matter the people expected which indeed is, that none be compelled against Conscience in the worship of God, nor any molested for Conscience sake, the oppression for Conscience, having been the greatest oppression that ever lay upon religious people, and therefore except that be removed, the people have some case by removall of the Bishops, but rather will be in greater bondage, if more and worse spirituall taskmasters be set over us.

These were no small matters also, their abolishing the High-Commission, and Starre Chamber for oppressing the people, by imposing the Oath Ex Officio, and by imprisoning of men, contrary to law, equitie, and justice. But if the people be not totally freed from oppression of the same nature, they have a very small benefit of the taking downe of those oppressing Courts. Seeming goodnesse is more dangerous then open wickednesse. Kind deeds are easily discerned from faire and pleasing words. All the Art and Sophisterie in the world, will not availe to perswade you, that you are not in Newgate, much lesse that you are at libertie.

And what became of that common and threed-bare doctrine, that Kings were accountable only to God, what good effects did it produce? No, they are but corrupt and dangerous flatterers, that maintaine any such fond opinions concerning either Kings or Parliaments.

What prejudice is it to any in any authority, meaning well, to be accountable, for indeed and truth all are accountable, and it is but vaine, (if not prejudiciall) for any to thinke otherwise. Doth any man entrust, and not looke for justice and good dealing from him he trusts.

And if he find him through weakenesse or wickednesse doing the contrary, will he forbeare to set him right (if he can.) Can he sit downe silently with injurie or prejudice? I could judge those people very neare to bondage, (if not to ruine) that could be brought to beleeve it, there be many instances both Forraigne and Domestick, which yet I forbeare to expresse.

The greatest safety will be found in open and universall justice, who relyeth on any other, will be deceived. Remember therefore (saith God) whence thou art falne and repent, and doe the first workes, or else I will come quickly, and will remove thy Candle sticke out of his place. March not so swiftly ye mighty ones, one single honest hearted man alone oftimes by unpleasing importunity, not only stayes, but saves a whole Army from inevitable danger; for better is wisdome then weapons of warre Ecclesiastes 9.18. Timely mementoes and cautions to advised and modest men (howsoever uttered) are never without good effect. If godly David made some good use even of rash Simeis railing, then what happie use may the godly minded make of any faithfull mans words, which tend altogether, to justice, equitie, and reason?

Nor can I imagine any evill is now intended towards you for your faithfull and plaine dealings, except by some few, and those instigated by one onely, who (by his great successe, in getting out Mr. Henry Martine, that just and zealous Patriot of his Countrey, and some other prevalencies) hath swolne so big with confidence, of greater matters, that he thinkes Lilburns blood the next meat Sacrifice for Oxford, so that what the King could not doe to him (as one of the Parliaments best friends) when he was close Prisoner there, the Parliament themselves must endeavour to doe to him in his unjust prisonment here.

The Poyson of Asps is under that wicked mans tongue, with which he laboureth alwaies to poyson Scripture, (mixing it figuratively) in his discourse to corrupt, sinister, and unworthy ends, whose malice and hypocrisie (doubtlesse) will ere long discover him to all men.

And (I doubt not) but that same God that took a happie course with Haman, and delivered Mordicai and all his people, will in your greatest necessity and his fittest opportunity, fight against all your enemies, and deliver both you and all yours out of all your afflictions, at least so to mitigate and sweeten them (by supporting you under them, or rather bearing of them with you,) that this shall prove to be exceeding joyes and consolations, to you and all that love you.

The honest and plaine men of England in dispite of that mans mallice shall be your Judges, and will spread forth in order (like King Ezekias letter) both before God and their owne consciences, what a world of injuries and miseries you (betweene 20. and 30. yeares of age scarcely to be paraleld any where in this age) have with great fidelity, magnanimitie, and constancie undergone, in the discharge of your conscience, and defence of the liberties of your native Countrey, and will not suffer a haire of your head to be touched, nor any reproach to be stucke upon your good name, but you shall live and be an honour to your Nation in the hearts of all honest and well affected men, which shall ever be the hearty desire of me.

There is here a copie of an excellent letter, which comming to my hands, by the carefull meanes of a worthy friend, who is a Wel-willer both to his Countreys priviledges, and to those few who either stand for them, or for the truth, have thought it my dutie not to smother nor obscure such a needfull Epistle but rather (as times are) to manifest it to the world, according as it came entituled to me, namely, A Private letter of publique use: Whereby it may appeare now in these dangerous dayes, both how the States and Clergie of this Kingdome have pittifully abused the people, even our antient predicessors for many ages, both in Church and Common wealth.

First, In bringing them with a high hand, under heavy thraldome and great bondage, and then keeping them in lamentable slaverie for many hundreds of yeares, as still their Successors the States men and Clergie of our dayes, doe with all their policie and machinations; and what designes they cannot thereby bring to passe, they endeavour by all possible meanes (whether directly or indirectly) even by open violence, without shewing any just cause, and yet all under the colour of lawes, when in the meane time they were called together, sworne, intrusted and commanded, both to rectifie whatever wicked decrees, Popish Cannons, Arbitrary, corrupt, or defective Lawes, their predicessors in the dayes of grosse ignorance and palpable darknesse, did establish.

Howsoever, the body of the Letter doth not specific in plaine tearmes, what the title painteth out in lively colours, yet thou being judicious and industrious, may easily enough perceive the same by the full scope, true intent and meaning thereof, intimated to thy understanding, under the Authors modest and loving expressions, to this worthy instrument of Englands delivery, Lieuten. Collonell Lilburn, that he may see more cleerly, then (it may be) he did formerly, both how far short even those which we call our best lawes, commeth of the marke of perfection, justice, integrity, and reason, that the worthyes of Parliament, according to their duty unto the people, and the peoples due at their hands, may not only reforme what is amisse (and that now whiles they professe reformation) but likewise carrie that dutyfull respect unto him, as one of their most trusty servants, and that according to the degree, nature, and eminencie of all his faithfull services, and cruell sufferings, and that such others, (though these be few) may be rather encouraged to persist, then any wise being so rewarded, to desist. Fare you well.

Courteous Reader, I desire thee to read a late Printed Booke intituled Englands birthright justified, against Arbitrarie usurpation, whether Regall or Parliamentary, or under what Vizar soever.