[William Walwyn], A Helpe to the right understanding of a Discourse concerning Independency (6 February 1645).

[Created: 21 Apr. 2021]

[Updated: October 31, 2022 ] |

For further information see the following:

- This is part of the Leveller Collection of Tracts and Pamphlets Project.

- some biographical information about William Walwyn (1600-1680)

- a full list of the Leveller Tracts and Pamphlets in chronological order

Bibliographical Information

ID Number

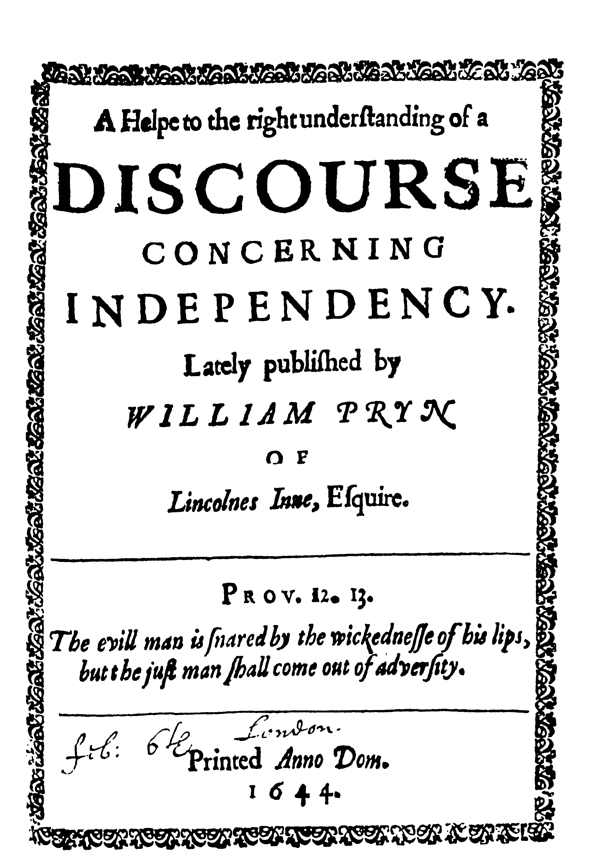

T.43 [1645.02.06] [William Walwyn], A Helpe to the right understanding of a Discourse concerning Independency (6 February 1645).

Full title

[William Walwyn], A Helpe to the right understanding of a Discourse concerning Independency. Lately published by William Pryn of Lincolnes Inne, Esquire.

Prov. 12.13. The evill man is snared by the wickednesse of his lips, but the just man shall come out of adversity.

Printed Anno Dom. 1644.

Estimated date of publication

6 February 1645

Thomason Tracts Catalog information

TT1, p. 360; Thomason E. 259. (2.)

Editor’s Introduction

This pamphlet is a strong defence of religious toleration written in opposition to a couple of tracts by the Parliamentarian William Prynne attacking “Independency” - Indpendency Examined (26 Sept. 1644 and Truth Triumphing over Falsehood (n.d.??). Walwyn believes that Prynne had sold out and no longer practiced what he preached, especially when it came to his defence of high lawyer’s fees and the requirement for plaintiffs to travel to London to get their cases heard.

Furthermore, Prynne seems to have forgotten that many of the adherents of religious sects (such as Anabaptists, Brownists, Separation, Independents, or Antinomies) had fought for political and religious liberty in the civil war, were thus friends of liberty, and should d be respected for this by having their religious views and practices tolerated by others. Freedom of conscience was perhaps the most important freedom of them all and thus should not be violated by others, whether acting as individuals or by their delegates in Parliament .

Walwyn concludes by arguing that the “freedom of discourse” is the best way to eliminate error and falsehood and given Prynne’s skill as a writer Walwyn believes that if he is in fact correct in his religious views and if “the Press (were) open for all Subjects” then he would be able to “out-write his opposers” without the need to persecute them.

Text of Pamphlet

A helpe to the right understanding of a Discourse concerning INDEPENDENCY, &c.

As it is a very great benefit to the world when wise and considerate men, suffer for maintenance of a just cause: so also it proveth often-times very prejudiciall to a Nation, when rash inconsiderate men, wise only in their owne strong conceits, doe suffer though for a cause as just as common freedome it selfe: because suffering winneth reputation to the person that suffereth, whereby his sayings, opinions, and writings carry authority with them: and though never so much blended with slightnesse, arrogance, impurity, violence, error, and want of charity: yet make they deep impression in the minds of many well meaning people, and sway them to the like, or dislike of things: not as they are really good, or palpably evill in themselves, but according to the glosse, or dirt, that such men through ignorance, impatience, or malice cast upon them.

For instance whereof, I am somewhat troubled that I must alledge Mr. William Pryn, who to his great commendation in the late arbitrary times suffered for the maintenance of the just liberties of his Country: but in a great example of late it is too sadly proved that he that did the greatest service, may live to doe the greatest mischiefe: and I am fully instructed, That only perseverance in well-doing, is praise-worthy: and therefore I conceive I may without breach of charity, be as bold with him as with any other man whatsoever: that others may learne by me to respect good men no longer then they continue so.

Of late he is fallen upon so unhappy a subject (The difference of judgement in matters of Religion) and hath so totally engaged himselfe therein that even men who have formerly had him in great repute for integrity, begin to doubt his ends; supposing that he strikes in with the rising party in hope to raise himselfe with them, and by them; and that he is carried away with that infirmity unto which men of his tribe have been much subject.

Others there are that conceive he is defective only in his understanding, and easily out-witted, and wrought to doe that, which he intended not to do, charitably hoping by his endeavours in the argument of Church government that he really intended the reconciling of all parties, and that he hath unhappily wrought a contrary effect, and made the division greater, through his want of judgement, and naturally passionate weaknesse: inconsiderately engaging, and (being engaged) and prosecuting with violence: and they argue it to be so, from his publishing Romes master-piece; and the Archbishops Diary; intending, no doubt, to blazon the vilenesse of that Arch Incendiary to the world; whereas to an advised Reader, it will be evident that the first is framed of purpose to lay the designe of all our troubles upon the Papists; and make the Archbishop such an enemy thereunto, as that they plotted to take away his life; as if Satan were divided against Satan; and his Diary is so subtilly contrived, as that among those from whom he expecteth honour, it cannot faile to worke most powerfully thereunto, so great are his good workes therein expressed, so large are his pious intentions, so watchfull over his wayes, so seldome offending, so penitent after offences, so devout in prayer, so learned and patheticall in his expressions; that to any that are but tainted with the least Prelaticall superstition, he will appeare a Saint, if not equall to Noah, Lot and David, yet full parallel with the most holy Primitive Fathers; especially when they shall consider that these his works were published by his greatest enemy, which was the Archbishops Master-piece indeed, being both written of purpose to be published in their best season, and by a person that should most advantage the deceit: if it had not been so, they had easily been fiend or concealed, past his finding: no man can thinke the Bishop so impolitick, as after so long imprisonment, not to be warned concerning his notes.

Others judge him to be much of the Archbishops spirit, his late adversary, and feare that if he had equall power to that he once had, he would exceed him in cruelty of persecution; and their reason is, because he is so violently busie already, egging and inciting the Parliament, like their evill Genius, to acts of tyranny against a people he knows innocent: how much more would he rage against them had he that command of censure, fine, pillory, imprisonment and banishment, which the Archbishop unjustly usurped; especially since his rage against them has so exceeded all bounds of modesty already, as to affirme that their writings are destructive to the very being of Parliaments, and as bad or worse then the Popish Gunpowder-plot, and to tearme their honest and submisse demeanours, Insolencies, unparalleled publicke violations and impeachments of the rights and priviledges of Parliament, and of the tranquility and safety of our Church and State. I am at stand Methinks, and cannot but grieve within my selfe to consider how full swolne with bitter malice, yea and the very poyson of Aspes, that breast must needs be from whence proceeds such malevolent and scandalous speeches, yet so grossely untrue and unsutable to the spirits of the Independents.

Men likewise say that this must needs proceed from spleene: for if he were a really conscientious man he would first pull the beame out of his own eye, as he is a Lawyer, and examine his owne wayes in the course of his practise, or set out something to set out the unlawfulnesse of tythes, as learned Mr. Selden hath done. Mr. Pryn professeth the true Christian Religion, and that most zealously, yet continueth to take fees for pleading mens causes, a thing that the vertuous men amongst the very heathens accounted base, and would doe it gratis: and what fees taketh he? no lesse then treble the vaine of what is taken by pleaders in Popish Countries; but he taketh as little as any man of his calling, and no more but what is lawfull for him to take: therein, say they, consists the misery of the Common-wealth, with all other the extreame abuses of our Laws, the very way of the ending of controversies, being so totally pernicious and full of vexation: that were he truly conscientious for the good of the whole Nation, as he pretendeth, he would have laid open to the Parliament, how improper it is that our Laws should be writen in an un-knowne language, that a plaine man cannot understand so much as a Writ without the helpe of Councell; how prejudiciall it is that for ending a controversie, men must travell Terme after Terme from all quarters of the Land to London, tiring their persons and spirits, wasting their estates, and beggering their families; tending to nothing but the vexation of the people, and enriching of Lawyers; with a little labour had he been so vertuously disposed, he could have discovered the corrupt originall thereof, and have layed open all the absurdities therein, and shewed the disagreement thereof to the rules of Christianity: he-could also have shewed to the Parliament what of our Lawes themselves are unnecessary, what are prejudiciall to good men, and have moved for reducing all to an agreement with Christianity: were he (say they) truly pious, and could deny himselfe, this he would have done, though he had thereby made himselfe equall to men of low degree, both in estate, food, and rayment: yea though for his livelihood hee had beene constrained to have laboured with his hands, &c. This indeed had beene a proper worke for him a Christian Lawyer in a time of Reformation: What needed he to have meddled against the Independent and Separation, there being so many learned Divines (as hee himselfe esteemes them) sitting in Councell so neare the Parliament, which shewes him to bee too officious?

And as concerning Church-Government: If hee had really intended the good of the Nation, and the weale of all peaceable minded men, he would have had in minde such considerations as these.

The Parliament are now upon setling the affaires of the Church, a thing of a very nice and dainty nature, especially being undertaken in a time of a homebred Warre: If it be not very advisedly and cautiously done, it may soone divide the wel-affected party within it selfe, then which nothing can be more pernitious and destructive: already I have seene some that have laid downe Armes, and many withdraw their persons and estates into forreigne parts, for no other cause but for being disturbed or discouraged in exercising of their consciences in matters of Religion: And it was but thus in the Prelaticall time. I finde by my selfe, that Christians cannot live, though they should enjoy all naturall freedome and content, where they are not free to worship God in a way of Religion: And I finde also by my selfe that Christians cannot worship God in any way but what agreeth with their understandings and consciences; and although I may be at liberty to worship God according to that way which the Parliament shall set up for a generall rule to the whole Nation; yet if I were not perswaded that I might lawfully submit thereunto, all the torments in the World should not enforce mee: and this I finde to bee the case of many conscientious people, very well affected to the Parliament and to common freedome: Men that have spent their estates, and hazarded their lives as freely in defence of just Government, as any men whatsoever; and whether they are under the names of Anabaptists, Brownists, Separation, Independents, or Antinomies; wee have had all their most affectionate helpe in throwing down Episcopacy and arbitrary government: men they are that still remaine in most opposition to the Popish and malignant parties, somewhat we must doe for the ease of these our brethren, it must not be in the settlement of our Reformation that they remaine under the same restraint or molestation for their consciences as they were in the Prelaticall time; we must doe as we would be done unto: if any sort of them were greater in number then we, and had authority to countenance them, we should esteem it hard measure, to be restrained from exercising our Religion according to our consciences, or to be compelled by fines, imprisonments, or other punishments, to worship contrary to our consciences, we must beare with one anothers infirmities; no condition of men in our dayes have an infallibility of judgment: every one ought to be fully perswaded in his owne minde of the lawfulnesse of the way wherein he serveth God; if one man observe a day to the Lord, and others not; and both out of conscience to God, both are allowed by the Apostle; and the one is not to molest, no not to despise or condemne, Rom. 14. v. 3. much lesse compell the other to his judgement, because whatsoever is not of faith or full assurance of minde is sin: had Mr. Pryn debated thus with himselfe, he had shewed himselfe a true Disciple of Christ and his Apostle: differing opinions would not then have appeared such abominable, damnable things in his sight: The dealing of our Saviour with those most erronious Sadduces, would have come into his mind, they beleeved that there was neither Angell nor Spirit, and that there was no resurrection: Opinions as contrary to the current of the then Interpreters, as any in our time, and yet they professed it openly, as appeareth by their attempting our Saviour, and were as unreproved of him as of authority; he resolves their question by an answer which removed that absurdity which they thought impossible: briefly telling them, That they neither marry nor are married, but as the Angels of God in heaven; using them gently, without threats or reproaches.

If Mr. Pryn had thought of this Subject, with such like considerations, he would soone have seen, That the people of a Nation in chusing of a Parliament cannot confer more then that power which was justly in themselves: the plain rule being this: That which a man may not voluntarily binde himselfe to doe, or to forbear to doe, without sinne: That he cannot entrust or refer unto the ordering of any other: Whatsoever (be it Parliament, Generall Councels, or Nationall Assemblies:) But all things concerning the worship and service of God, and of that nature; that a man cannot without wilfull sin, either binde himselfe to doe any thing therein contrary to his understanding and conscience: nor to forbeare to doe that which his understanding and conscience bindes him to performe: therefore no man can refer matters of Religion to any others regulation. And what cannot be given, cannot be received: and then as a particular man cannot be robbed of that which he never had; so neither can a Parliament, or any other just Authority be violated in, or deprived of a power which cannot be entrusted unto them.

That Emperours, and Kings, and Popes, have assumed an absolute power over Nations in matters of Religion, need not to have beene so laboriously proved; nor that Councels and Parliaments have done the like: the matter is what they have done of right: who knowes not that all these have erred as often as they did so: our present Parliament have greater light then any former, and propose to themselves to abandon what ever former Parliaments have either assumed, or done upon mis-information: and have not yet declared themselves to dissent from the fore recited rule: and then Mr. Pryn may consider, whether he hath not extreamly mispent his time, and with much uncharitablenesse injured that faithfull servant of God, and sincere lover of his Country, Mr. John Goodwin, a man that to my knowledge, and to the knowledge of many, values neither life nor livelihood, could he therewith, or with losse thereof, purchase a peaceable liberty to his Country, or a just Parliamentary government; so far is he, or that other worthy man Mr. Burton; or any Independent, Anabaptist, Brownist, or any of the Separation now extant, from deserving either those slight, but arrogant expressions of his in his said Epistle, telling the honourable Parliament, That he knows not what evill Genius, and Pithagorian Metempsychosis, the Antiparliamentary soules formerly dwelling in our defunct Prelats earthly Tabernacles, are transmigrated into, and revived into a new generation of men (started up of late amongst us) commonly knowne by the name of Independents: such bombast inck-horne tearmes, savouring so much of a meer pedanticke, as ill beseemeth his relation to that supream power of Parliament: And thogh those Independents, for the most part are such by his owne acknowledgement, whose affections and actions have demonstrated them to be reall and cordiall to the Parliament and Church of England, for which (saith he) and for their piety they are to be highly honoured, yet hath not he so much charity as to shew any inclination that they should be relieved in their just desire of Christian liberty; but prosecutes all those their severall judgements, as derogatory and destructive unto Parliament and Church in their Anarchicall and Antiparliamentary positions; for which, and for their late gathering of Independent Churches, contrary to Parliamentary injunctions (which were never seen) they are he sayes, to be justly blamed as great Disturbers of our publicke peace and unity: these his great words make a great noise, I confesse: a man that did not converse amongst these people, may easily be induced to believe them to be very dangerous. Mr. Pryn is of great credit with many in authority, and how far he hath therein done them wrong, his owne conscience will one day tell him to his cost.

If Mr. Pryn were a stranger to the Separation, and unacquainted with the innocency of their wayes and intentions, I might charitably judge him to plead for the persecution of Gods people ignorantly, as St. Paul did: but since he cannot but know that they are both in affection and action reall and cordiall to the Parliament, as himselfe confesses, and hath found them for his owne particular compassionate in his sufferings, and liberally assistant to him in his miseries: I professe, I can make no other construction of his so violent pleading for persecution, and incensing the Parliament against a People he knowes harmlesse, and modest and reasonable in their desires whose utmost end is only not to be molested in their serving of God: I can make no other construction of it, I say, that engagement to the Divines, and some interest of his owne hath begot a hardnesse over his heart, and clouded that noble courage and common spirit which did possesse him. If he wanted information, I would labour with him, but since I cannot doubt but that he hath sufficient of that, I will leave him till the truth and excellency of that freedome against which he fights, till the sincerity and uprightnesse of the Separation which he delivers up to the sword, in these words, Immedicabile uninus ense recidendum est, make him one day appeare even to his present admirers, the man he is indeed.

In the meanetime, I turne to the people, and desire them to enquire after the Separation, and have full knowledge of them: they will then finde they are extreamly misunderstood by authority, and all others that apprehend them to be any other then a quiet harmlesse people, no way dangerous or troublesome to humane society: I have found them to be an ingenious enquiring people, and charitable both in their censures of others, and due regard to the poore. I am become their advocate, out of no engagement or relation to them, I professe, more then what my knowledge of their sincerity and true affection to their Country hath begotten in me.

Mr. Goodwin, I need not speak much of, he is a man so well knowne, that Mr. Pryns so rigid urging of his expressions upon him, as he hath too largely and spleenishly done in his Epistle, making so unsavoury and utterly disproportioned comparisons betwixt him, and the malignant Prelats, and Antiparliamentary Cavaliers, that a man that knows the antipathy betweene them cannot but stand amazed thereat; and necessarily conclude that something hath blinded not only the light of Mr. Pryns conscience, but of his understanding also, and then after a most unchristian application, his sentence is in these dismall old Antichristian and Prelaticall tearms; if they will not be reclaimed, fiat justitia, better some should suffer then all perish: but happy it is, that the power of Parliament is not in Mr. Pryn: if it were (in the minde he is now in) ’tis much to be doubted, his part would differ little from Bonners or Gardiners in Queen Maries dayes: but blessed be God, it is otherwise; nor will that just Authority I presume be moved either with his fierce exclamations, or incomparable flatteries to doe any thing contrary to right reason and true Christianity: nor is there indeed (the fore mentioned rule holding) any cause why that supreme Authority should be offended: for all sorts of Independents, whether Anabaptists or Brownists, or Antinomians, or any other doe all agree, that in all Civill and Military causes and affaires, they have an absolute supreme power: And if they shall conceive it just and necessary for the State to propose one way of worship for a generall rule throughout the Land, and shall ingratiate the same by an exemption from all offence and scandall of weake consciences as far as is possible: The Independents, &c. have nothing to oppose against their wisdomes: and if the publicke way should be such as should agree with any of their judgments and consciences, they would most readily joyne in fellowship therein: but if their judgements and consciences should not be fully satisfied concerning the same, then whatsoever is not of faith is sinne; and they cannot but disjoyne: and in such a case, all good men that know them will shew themselves true Christians indeed, in becomming humble suters to the Parliament, that as for convenience to the State they propose one generall publicke way: so for the ease of tender consciences, and for avoyding of sinne either in compelling of worship contrary to conscience, or in restraint of consciencious worship: they would be pleased to allow unto all men (that through difference of judgement could not joyne with the publicke congregations) the free and undisturbed exercise of their consciences in private congregations.

And if they should be pleased so to doe; it is but what is agreeable to common equity and true Christian liberty: It hath beene the wisdome of all judicious Patriots to frame such laws and government as all peaceable well minded people might delight to live under; binding from all things palpably vitious by the greatest punishments, and proposing of rewards and incouragements to all publicke vertue: but in things wherein every man ought to be fully perswaded in his particular minde of the lawfulnesse or unlawfulnesse thereof; there to leave every man to the guidance of his owne judgement; and where this rule is observed, there all things flourish, for thither will resort all sorts of ingenious free borne minds: such Commonwealths abound with all things either necessary or delightfull, and which is the chiefe support of all: such a government aboundeth with wise men, and with the generall affections of the people: for where the government equally respecteth the good and peace of all sorts of virtuous men, without respect of their different judgments in matters of Religion: there all sorts of judgements cannot but love the government, and esteem nothing too pretious to spend in defence thereof.

Who can live where he hath not the freedome of his minde, and exercise of his conscience? looke upon those Governments that deny this liberty, and observe the envyings and repinings that are amongst them, and how can it be otherwise, when as if a man advance in knowledge above what the State alloweth, he can no longer live freely, or without disturbance exercise his conscience? what follows then? why he takes his estate, and trade, and family, and removes where he may freely enjoy his minde, and exercise his conscience: and as this hath been the sad condition of this Nation to its extreame lesse divers wayes: so Mr. Pryn would have it continued for ought by his writings can bee discovered; nor is he any whit troubled in spirit to see at this day of Jubile, and of Reformation unto all just liberty: thousands of well-affected persons at their wits end, not knowing where to set their foot, for want of encouragement in the cause of conscience.

I but, sayes Mr. Pryn, our Covenant bindes us to maintaine an absolute Ecclesiastick power in the Parliament: it bindes us to maintaine their undoubted rights, power, priviledges: but Mr. Pryn must ever beare in minde, that what the people cannot entrust that they cannot have; which will answer all objections of that nature.

As for our Brethren of Scotland: there is no doubt, but they are sad observers of all the distempers and misunderstandings that are amongst us, and would be most glad that the wisdome of Parliament would minister a speedy remedy; although therein they should somewhat vary from their way of Church Government; as well knowing there can be no greater advantage given to our common Enemy, then the continuance of these our divisions and disaffections.

And where Mr. Pryn may suppose all liberty of this kinde, would tend to the encreasing of erronious opinions, and disturbance to the State; I beleeve he is mistaken; for let any mans experience witnesse whether freedome of discourse be not the readiest way both to give and receive satisfaction in all things.

And as for disturbance to the State: admit any mans judgement be so misinformed, as to beleeve there is no sinne; if this man now upon this government should take away another mans goods, or commit murder or adultery; the Law is open, and he is to be punished as a malefactor, and so for all crimes that any mans judgement may mislead him unto.

And truly you are to consider in reading his great Book (improperly entituled, Truth triumphing over falshood) that he acknowledges them to bee but nocturnall lucubrations, distracted subitane collections; and if you truly weigh them you will finde them very light, and little better compacted then meere dreams, or such fumes as men use to have betwixt sleeping and waking: and when you have viewed all those many sheets, consider them as in one, and it will resemble Saint Peters vision, a mixt multitude of unclean testimonies raked out of the serpentine dens of meer tyrannous Princes, Antichristian and Machivillian Councells, erronious Parliaments, and bloudy persecuting Councells and Convocations, which he hath produced, to be perswaders and controlers in these times of pure Reformation. Certainly if a man were not in a deep Lethargy, such a masse of so grosse excrements could not passe from him without offence to his owne nostrill; if it be his case, hee that scracheth him most, and handles him most roughly, is his best friend, there being no other remedy; when he is recovered and broad awake hee will thanke his Physitian: in the meane time thus much is presented to his admirers, to preserve them from that malevolent infection, unto which his writings and reputation of former sufferings might subject them unto; and this by one who is no more obliged to any Independent, Anabaptist, Brownist, Separation, or Antinomian, then Mr. Pryn himseife; but hath taken paines to know them somewhat better, and cannot but love them for their sincere love to our dear Country, to the just liberties thereof, and to our just Parliamentary Government: most heartily wishing them their just desires and a peacefull life amongst us: That they might be encouraged to joyne heart and hand with us, in prosecution of the common Enemies, of our common liberties, knowing no reason why I should not love and assist every person that loves his Country unfeignedly, and endeavours to promote the good and freedome thereof, though of different judgement with me in matters of Religion; in which case I am not to judge or controle him, nor he me: and I heartily wish all true lovers of their Country were in this minde: and when they are so, then the miseries of this Nation will soon be ended, and untill then, they will continue, as is too much to be feared: I could heartily wish that what is here written, might worke a good alteration in Mr. Pryn but when I remember the story. That a certain Lawyer came to our Saviour, tempting him; I fear it is in respect of himself, but washing of a Blackamoore: self deniall, is too hard a lesson for him; and if so, you shall have him in some bitter reply instantly; for though he cannot out-reason men, yet if he can but out-write his opposers, he claps his wings and crows victoria, that he hath silenced them all. Truly for writing much, I verily believe that he out-does any man in ‘England, which is no commodity at all to a State or the Truth, and then considering what free liberty he hath to Print whatsoever he writeth, discreet men will consider what a great advantage he hath therein, and will not deem it want of ability in his opposers, though they doe not see him presently answered to their full satisfaction; and yet I am confident his great Booke will be suddenly answered throughly: but if Mr. Pryn would deale upon equall tearmes, and use meanes that the Presse may be open for all Subjects, but for six moneths next comming free from the bonds of Licencers; if Mr. Pryn be not so silenced, as that all his former and late books doe not under sell browne paper; let me be henceforward esteemed as vaine a boaster, as now I esteem him: for his opposers, as in the justnesse of this cause they cannot regard his spleene; so nothing would be more welcome to them then his love, and change of minde, whereof some doe not dispaire: however, I end with his owne words, more justly applyed fiat justitia; better it is that he undergoe this my plaine dealing, then that either the Readers of his bookes should be seduced, or so many innocent well-affected persons be so grossely abused by him.