William Walwyn, The Fountain of Slaunder Discovered (30 May 1649).

For further information see the following:

- This is part of the Leveller Collection of Tracts and Pamphlets Project.

- some biographical information about William Walwyn (1600-1680)

- a full list of the Leveller Tracts and Pamphlets in chronological order

Bibliographical Information

ID Number

T.196 [1649.05.30] William Walwyn, The Fountain of Slaunder Discovered (30 May 1649).

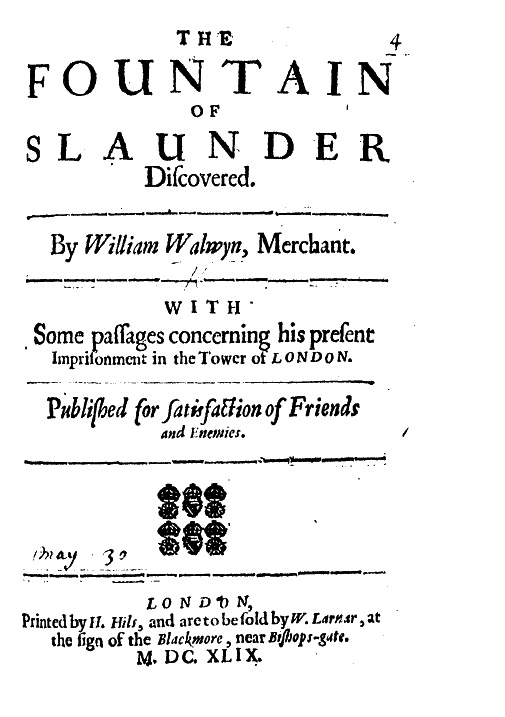

Full title

William Walwyn, The Fountain of Slaunder Discovered. By William Walwyn, Merchant. With some passages concerning his present Imprisonment in the Tower of London. Published for satisfaction of Friends and Enemies.

London, Printed by H. Hils, and are to be sold by W. Larnar, at the sign of

the Blackmore, near Bishops-gate. M.DC.XLIX. (1649)

Estimated date of publication

30 May 1649.

Thomason Tracts Catalog information

TT1, p. 746; Thomason E. 557. (4.)

Editor’s Introduction

(Placeholder: Text will be added later.)

Text of Pamphlet

The Fountain of Slander discovered, &c.

From my serious and frequent consideration of the goodness of God towards man, the innumerable good things he created for his sustenance & comfort; that he hath made him of so large a capacity as to be Lord over other creatures; ever testifying his love, by giving rain and fruitfull seasons, feeding our hearts with food and gladnesse: That he hath made him, as his own Vicegerent, to see all things justly and equally done, and planted in him an ever living conscience to mind him continually of his duty; I could not but wonder that this should not be sufficient to keep mankind in order, and the world in quiet.

But when I considered the infinite obligations of love and thankfulnesse, wherewith men, as Christians, are bound unto God, and yet how extremely averse all sorts of Christians were, to the essentiall and practicall part of Religion; so great ingratitude did quite astonish me.

And made me with much patience passe over the many injuries I have suffered for my own endeavours after common good; and to resolve within my self, that for any man to give good heed to the voyce of God in his own conscience, and vigorously to appear against the unrighteousnesse of men, is certainly the way to affliction and reproaches.

And hereupon, when of late I have been hunted with open mouth, and could appear in no place, but I was pointed at, and frown’d upon almost by every man, I was but little moved; for why should I expect better measure than my Maker and Redeemer? And so with patience sate me down, and considered, whence so many undeserved aspersions should proceed against me at a time too, when I was most secure; all power being then in the hands of such, from whom I had merited nothing but love and friendship.

I was sure any man that had a mind to know what, or where I was, might easily trace me from my present habitation in Moor-Fields, to Newland in Worcestershire, where I was born of no unknown or beggarly parentage, as some have suggested to disparage me; but such as were both generous, as the world accounts; and ingenuous too, as wise men judge; and to whose exemplary virtue I owe more, then for my being.

I knew an exact accompt might be taken of me, in lesse then one daies time: and that this may gain belief, I shall refer the enquiry of my birth and breeding to Mr Sallaway, a Member of Parliament for the County of Worcester; and for my first eight years in London to Mr Crowder, another Member of this present Parliament: The truth of whose relation, I suppose none will doubt, and I shall be obliged to them, to satisfie as many as desire it.

For 13 years together, after that, I dwelt in the Parish of Saint James, Garlick-hill, London: Where, for all that time, any that please, may be satisfied; since which time, I have lived in Moor-Fields, where now my Wife and Children are; and what my demeanour there hath been, my neighbours will soon resolve.

I have been married 21 years, and have had almost 20 Children; my profession hath been Merchandising, but never was beyond the Seas; but my Brother died in Flanders in my imployment, and cost me near 50 pounds, rather then he should want that buriall accustomed to Protestants; which one would think might suffice to prove me no Jesuite.

In all which time, I believe scarce any that ever knew me, will be so dis-ingenuous as to spot me with any vice; and as little of infirmity as of any other; having never heard ill of my self, untill my hopes of this Parliament encouraged me to engage in publique affairs; being then 40 years of age, 20 of which I had been a serious and studious reader and observer of things necessary.

But then in short time, I heard such vile unworthy things as I abhorred, and made me blush to hear; and ever since, reproaches have pursued me, like rowling waves, one in the neck of another.

All which being groundlesse, as my conscience well knew, I soon concluded, they were devised purposely by some Politicians (whose corrupt interest I opposed) to render me odious to all societies of men, and so to make me uselesse to the Commonwealth, which my long experience and observation told me, was a common practice in all ages.

So as to me it is evident, that corrupt interests are the originall of Politicians; for a just course of life, or interest, needs no crafts or policies to support it: And it is as clear to me, that Politicians are the originall of reproaches, and the fountain of slander: for that it being impossible to defend an ill cause by reason; reproaches necessarily must be devised, and cast upon the opposers to discredit what they speak; or it were impossible for any corrupt interest to stand the least blast of a rationall opposition.

Most miserable unhappy therfore are those men, who are engaged and resolved to continue in any kind of corrupt interest, or way of living; since they are thereby all their life long necessitated to become meer Politicians, devisers of lies, slanders, falshoods, and many times to perpetrate the most dishonest actions that can be imagined, for supportation of their interest.

And upon this accompt I am certain, and upon no other, so much dirt hath been cast upon me; for when art and sophistry will not serve to vanquish truth and reason, aspersion generally wil do the deed.

Which hath made discreet and considerable men to make a contrary use of aspersions: For whereas the rash, and weak, when they hear either man or Cause asperst, they presently shun the men, and abhominate the cause upon little or no examination, as being affrighted therewith. Wise and discreet men, skilfull in the common rules and practises of the world, are so far from prejudging either the man or cause of evil; that without prejudging, or partiality, they make an exact enquiry, how things are, and determine nothing but upon good and reall satisfaction.

And there is good cause for every man so to do; for if all stories be well searcht into, it will be found. That unjust, cruel, covetous, or ambitious men, such as were engaged in corrupt interests, or in some wicked designs, were ever the aspersers; and honest, just and publique spirited men the aspersed.

That this is a certain truth, examples need not be brought out of common histories, whilst the Scriptures abound therewith.

It was the portion both of the Prophets and Apostles, and of all the holy men of all times: yea, our blessed Saviour, who spent all his time on earth in doing good, was neverthelesse tearmed, a Wine-bibber, a Friend of Publicans and sinners, a Caster out of Devils by Beelzebub the Prince of Devils. And who were they that so asperst him, but the great and learned Politicians of the times, who with the Scribes and Pharisees, set themselves against him and his doctrines, because he gave knowledge to the poor and simple; by which, their delusion, pride, oppression and corrupt interests were plainly discovered.

So that let no man look to escape aspersions, that sets himself to promote any publique good, or to remove any old or new setled evil; but let him resolve, according to the good he endeavoureth, so shall his aspersion be: Nor let him thinke, when time and his constant actings have worn out, one, or two, or ten aspersions, that he is therfore free; but if he continue to mind more good, he shall be sure to find new aspersions, such as he never dream’d of, or could imagine.

Luther opposeth the delusions and oppressions of the Pope, and his Clergy, and the ruine of Emperours, Kings and great ones of the world, laies them all open and naked to the view of all men: and who was ever more asperst then he?

Cornelius Agrippa sets forth a Treatise, entituled, The vanity of Arts and Sciences; and is reputed a Conjurer for his labour.

How faisly and vilely were our Martyrs reproached and cruelly used in Queen Maries daies, for opposing the wickednesse of the great ones of that time? And how unjustly Mr Greenwood, Mr Penry, and Mr Barrow suffered in Queen Elizabeths daies for publishing unwelcome truths, is yet sadly remembred.

Yet how odious did the Bishops set forth those that pretended for the Discipline of Presbyterie? all along comparing them to the Anabaptists of Munster; affirming, that (whatever they pretended) they aimed to destroy all Magistracy and Government; to have plurality of wives, and all things common; saying any thing of them to render them odious to the people.

In like manner the Court reproached Parliaments upon their least shew of redresse of grievances, or abatement of Prerogative; calling them, a factious, seditious, viperous brood, that intended to bring all to Anarchy, parity and confusion.

And even so divers Presbyters of late have dealt with the Independents, Brownists, Anabaptists, Antinomians, and the like; stiling them Heretiques, Blasphemers, Sectaries; and comparing the Army and their Leaders to Jack Cade, Wat Tyler, and John of Leydon. And so about that time dealt the Parliament with many wellminded people, that petitioned them for removall of long setled, and new imposed grievances, tearming them factious, and seditious Sectaries; and burnt their just Petitions most reproachfully by the common hangman.

And just so now deal some most unworthy Independents with many the present Asserters of common freedom, stiling them Levellers, Anti-scripturists, Atheists; and devise such scandalous, false aspersions against them; and publish the same with so much bitternesse and vilenesse of expression, as if they resolved of all that went before them, from Rabshekah, to the unhappy daies of Mr Edwards, and his Contemporaries, none should come nigh them for invention, or calumniation; and that upon no cause, except for opposing the present corruption and corrupt interests of the times; wherein it should seem, many of them are now engaged, and taking pleasure therein, are as impatient as ever Demetrius and the Crafts-men were with Paul for preaching against the Goddesse Diana, by making of whose Shrines they lived, tis like, very plenteously.

And although nothing be more evident, then that Aspersers are ever deceivers, and asperse for no other end but for their own interest and advantage, yet are not men sufficiently cautious to avoid their wiles, but are ensnared perpetually; for let a man with never so much discretion and fidelity, make known a publique grievance, or an imminent danger, and propose never so effectuall means for redresse and prevention, yet if one of these subtil Politicians, or their Agents, can have opportunity to buz into the ears of those that are concerned, thou the proposer art an Heretique, a Blasphemer, an Atheist, a denier of God and Scriptures; or, which is worse to most rich men, that he is a Leveller, and would have all things common: then out upon him, away with such a fellow from off the earth; better perish then be preserved by so prophane a person: and in the mean time, who so seemingly pious, meek and religious as the asperser? Whose councel so readily harkned to as his? which yet leadeth to a certain bondage, or destruction, never feared till felt.

And truly but for these deceits in Politicians, and these weaknesses in the people, it had been impossible but these times must necessarily have produced much more good to the Common wealth: and it is wonderfull to consider, how powerfully this delusion proves in all times; no warning or experience being guard enough against it, though to a reasonable judgment, no deceit be more palpable.

For generally the asperser is really guilty of what he unjustly brands another withall: So, the false Prophets accuse the true of falsnesse: In like manner, the false Apostles accuse the true: The Scribes and Pharisees were, indeed, friends of Publicans and Sinners, reall friends of Beelzebub, as being the chief of Hypocrites: The Pope and his Clergie really guilty of all they fained against Luther: Emperours and Great ones of the world, cry out of perfidiousnesse, and breach of Oaths; who have broken so frequently as they? or make so little of it when ’tis done? Those who cry out against Community, Parity and Levelling, in the mean time enforce all to their own wils, both Persons, Estates and Consciences, and if resisted, fire and sword, halters, axes and prisons, must be their Executioners. The persecutor is for the most part the most desperate heretick, and those that cry out so much against blasphemy, neither regard man nor honour God, pretending Godlinesse onely for by, and base respects: Those who make so great a noise against Atheists, are they not such as say in their hearts, there is no God? denying him in their actions and conversations, back-biting, covetousnesse, pride, and usury being no sinnes amongst them, men that have a meer specious forme of Godlinesse, but no power at all: Those that raise fames of denying the Scriptures; you shall have them do it so as if they did it purposely to bring Scriptures in question, and write so in defence of them, as if they bent all their endeavours (though subtilly and obscurely) to weaken the credit and belief thereof; and have the impudence to call their uncertaine, doubtfull preaching and sermons the word of God, preach for filthy lucre, and take money for that which is not bread; so that if people had but any consideration in them, they would easily discover the fraud, policy and malice of aspersors, and be armed against their stratagems.

And although the people for some time may be deceived by their delusions, and do not perceive their devises: yet God in the end discovers them to their shame; setting their nakednesse and the shame of their nakednesse open in the sight of all men; and that garment of hypocriticall Godlinesse with which they stalked so securely, becomes a badge of their reproach.

The Scribes, and Pharisees, and Herod, and Pilat had their time; but are their names now any other but a by-word? and doth not the Doctrine of Luther, shine in despite of all his mighty opposers?

What gained the Bishops by bespeaking the Presbyter of so much errour and madnesse, but their own down-fall? what got the Courtiers by accusing Parliaments of intending Anarchy and Community but their own ruine? and have not these Presbyters brought themselves to shame by their bitter invective Sermons and writings against the Independent and Sectaries?

And are all these forementioned, acquitted of the aspersions cast upon them? and am I and my friends guilty? why must these scandalous defamations be truer of us then of them? in their severall times they were beleeved to be true of them, and its time onely and successe that hath cleared them, and should perswade men to forbear censuring us of evil unlesse the just things we have proposed, and Petitioned for be granted; and if we content not our selves within the bounds of just Government let us then be blamed, and not before: but what sayes the politician if somebody be not asperst. Mischief cannot prosper if these men be believed and credited, downe goes our profit. And truely, that enemies to the common freedome of this Nation, or enemies to a just Parliamentary Government, enemies to the Army, or men of persecuting principles and practices, should either divide or scatter these false aspersions against me, I did never wonder at: beleiving these to be but as clouds that would soon vanish upon the rising of the friends of the Common wealth, and prevailing of the Army; And so it came to passe, and for a season continued; but no sooner did I and my friends in behalf of the Common-wealth, manifest our expectation of that freedome so long desired, so seriously promised them in the power of friends to give and grow importunate in pursuit thereof, but out flies these hornets againe about our ears, as if kept tame of purpose to vex and sting to death those that would not rest satisfied with lesse then a well grounded freedome: and since, we have been afresh more violently rayled at then ever, as if all the corrupt interests in England must downe, except we were reproacht to purpose.

And certainly there was never so fair an opportunity to free this Nation from all kinds of oppression and usurpation as now, if some had hearts to do their endeavour, that strongly pretended to do their utmost; and what hinders, is as yet, somewhat in a mistery; but time will reveal all, and then it will appear more particularly then will yet be permitted to be discovered, from what corrupt fountaine, (though sweetned with flowers of Religion) these undeserved clamours have issued against me and my friends.

But I shame to thinke how readily, the most irrationall sencelesse aspersions cast upon me, are credited by many, whom I esteemed sincere in their way of Religion, and that most uncharitably against the long experience they have had of me, and most unthankfully too, against the many services I have done them, in standing for their liberties (and animating others so to do) when they were most in danger and most exposed, never yet failing though in my own particular I were not then concerned) to manifest as great a tendernesse of their welfare as mine owne.

But in patience I possesse my self, such as the tree is such I perceive will be the fruit: and as I see a man is no farther a man then as he clearly understands; so also I perceive a Christian is no farther a Christian then as he stands clear from errour, and superstition, with both which were not most men extreamly tainted? such rash and harish censures could never have past upon me, such evil fruits springing not from true Religion; wherein, as full of zeal, as the times seeme to be; most men are far to seek: every man almost differs from his neighbour, yet every man is confident, who then is right in judgement? and if the judgement direct to practice (as no doubt it ought) no marvell we see so much weaknesse, so much emptinesse, vanity, and to speak softly, so much unchristianity, so many meer Nationall and verball, so few practicall and reall Christians, but busie-bodies, talebearers, serviceable, not to God, in the preservation of the life or good name of their neighbours, but unto polititians in blasting and defaming, and so in ruining of their brother.

If I now amidst so great variety of judgements and practises as there are, should go a particular way; Charity and Christianity would forbear to censure me of evill, and would give me leave to follow mine owne understanding of the Scriptures, even as I freely allow unto others.

Admit then my Conscience have been necessitated to break through all kinds of Superstition, as finding no peace, but distraction and instability therein, and have found out true uncorrupt Religion, and placed my joy and contentment therein; admit I find it so brief and plaine, as to be understood in a very short time, by the meanest capacity, so sweet and delectable as cannot but be embraced, so certain as cannot be doubted, so powerfull to dissolve man into love, and to set me on work to do the will of him that loved me, how exceedingly then are weak superstitious people mistaken in me?

That I beleive a God, and Scriptures, and understand my self concerning both, those small things I have occasionally written and published, are testimonies more then sufficient; as my Whisper in the eare of Mr. Thomas Edwards; My Antidote against his poyson; My prediction of his conversion and recantation: My parable or consultation of Physitians upon him: and My still and soft voice (expresly written though needlesse after the rest) for my vindication herein, all which I intreat may be read and considered: and surely if any that accuse and backbite me, had done but half so much, they would (and might justly) take it very ill not to be believed.

But when I consider the small thanks and ill rewards I had from some of Mr. Edward’s his opposers, upon my publishing those Treatises, I have cause to beleive they are fraught with some such unusuall truths, that have spoiled the markets of some of the more refined Demetrius’s and crafts-men; I must confesse I have been very apt, to blunt out such truths as I had well digested to be needfull amongst men: wherein my conscience is much delighted, not much regarding the displeasure of any, whilst I but performe my duty.

And in all that I have written my judgement concerning Civil Government is so evident, as (if men were men indeed, and were not altogether devoid of Conscience) might acquit me from such vanities as I am accused of; but for this, besides those I have named, I shall refer the Reader to my Word in Season, published in a time of no small need; and to that large Petition that was burnt by the hand of the common Hangman, wherein with thousands of wel-affected people I was engaged: and to which I stand, being no more for Anarchy and Levelling, then that Petition importeth; the burners thereof, and the then aspersers of me and my friends having been since taught a new lesson, and which might be a good warning to those that now a fresh take liberty to abuse us: but no heart swoln with pride as the politicians, but scornes advice, spurns and jeers, and laugh at all; yet for all their confidence, few of them escape the severe hand of Gods justice first and last, even in this world.

Indeed it hath been no difficult thing to know my judgement by the scope of that Petition, and truely were I as deadly an enemy unto Parliaments (as I have been and still am a most affectionate devotant to their just Authority) I could not wish them a greater mischief then to be drawne to use Petitioners unkindly, or to deny them things reasonable, upon suspition that they would be emboldened to ask things unreasonable, by which rule, no just things should ever be granted; wishing with all my heart that care may be speedily taken in this particular, the people already being too much enclined to be out of love with Parliaments, then which I know no greater evill can befall the Common-wealth.

Another new thing I am asperst withall, is, that I hold Polygamie, that is, that it is lawfull to have more wives then one; (I wonder what will be next, for these will wear out, or returne to the right owners) and this scandall would intimate that I am addicted loosely to women; but this is another envenomed arrow drawne from the same Pollitick quiver, and shot without any regard to my inclination; and shewes the authors to be empty of all goodnesse, and filled with a most wretchlesse malice; for this is such a slander as doggs me at the heels home to my house; seeking to torment me even with my wife and children and so to make my life a burthen unto me; but this also loseth its force, and availeth nothing, as the rest do also, where I am fully known; nay it produceth the contrary; even the increase of love and esteeme amongst them, as from those, whose goodnesse and certain knowledge can admit no such thoughts of vanity or vilenesse in me: one and twenty years experience with my wife, and fifteen or sixteen with my daughters, without the least staine of my person, putting the question of my conversation out of all question.

There are also that give out that I am of a bloudy disposition, its very strange it should be so and I not know it, sure I am, and I blesse God for it, that since I was a youth I never struck any one a blow through quarrell or passion; avoyding with greatest care all occasions and provocation; and although possibly nature would prevaile with me to kill rather then be killed; yet to my judgement and conscience, to kill a man is so horrid a thing, that upon deliberation I cannot resolve I should do it.

And though to free a Nation from bondage and tyranny it may be lawfull to kill and slay, yet I judge it should not be attempted but after all means used for prevention; (wherein I fear there hath been some defect) and upon extreme necessity, and then also with so dismall a sadnesse, exempt from that usuall vapouring and gallantry (accustomed in meer mercinary Souldiers) as should testifie to the world that their hearts took no pleasure therein; much lesse that they look’d for particular gaine and profit for their so doing: and I wish those who have defamed me in this, did not by their garnisht outside, demonstrate that they have found a more pleasing sweetnesse in bloud then ever I did.

Now some may wonder why those religious people that so readily serve the Polliticians, turnes in catching and carrying these aspersions from man to man, have not so much honesty or charity, as to be fully satisfied of the truth thereof, and then deale with me in a Christian way, before they blow abroad their defamations; or why the taking away of my good name, which may be the undoing of my wife and children should be thought no sin amongst them? but truely I doe not wonder at it, for where notionall or verball Religion, which at best is but superstition, is author of that little shadow of goodnesse which possesses men, its no marvell they have so little hold of themselves: for they want that innate inbred vertue which makes men good men, and that pure and undefiled Religion, which truly denominateth men good Christians; and which only giveth strength against temptations of this nature.

And as men are more or lesse superstitious, the effects will be found amongst them; nor is better to be expected from them untill they deeme themselves, no further Religious, then as they find brotherly love abound in their hearts towards all men: all the rest being but as sounding brasse and tinkling Simbals; nor will they ever be so happy as to know their friends from their foes, except they will now at length be warned against these cunning ways of Polliticians, by scandals and aspersions to divide them; and be so wise, as to resolve to beleeve nothing upon report, so as to report it againe, untill full knowledge of the truth thereof; and then also to deal as becommeth a discreet Christian, to whom anothers good name is as pretious as his own; being ever mindfull, that love covereth a multitude of sins.

But I have said enough as I judge for my owne vindication and discovery of the infernall tongues of Polliticians, that set on fire the whole course of nature, and am hopefull thereby to reclaime some weak wel-minded people from their sodain beleeving or inconsiderate dispersing of reproaches; and so to frustrate the polliticians ends in this dangerous kind of delusion.

As for those who know me and yet asperce me, or suffer others unreproved, all such I should judge to be polliticians their hirelings, or favourers; and I might as well undertake to wash a Blackmore white, as to turne their course, or restore them to a sound and honest mind.

However I shall no whit dispaire of the prosperity of the just cause I have hitherto prosecuted, because (though at present I be kept under) yet I have this to comfort me, that understanding increaseth exceedingly, and men daily abandon superstition, and all unnecessary fantastick knowledge; and become men of piercing judgements, that know the arts and crafts of deceivers, and have abillity to discover them; so that besides the goodnesse of the cause which commands my duty, I may hope to see it prosper, and to produce a lasting happinesse to this long enthraled Nation.

A good name amongst good men I love and would cherish; but my contentment is placed only in the just peace and quietnesse of my own conscience, I may be a man of reproaches, and a man of crosses, but my integrity no man can take from me; I may by my friends and nearest alliances, be blamed as too forward in publique affaires, be argued of pride, as David was by his brother; yet I thinke the family whereof I am, is so ingenious as to acquit me, and to believe my conscience provokes me to do what I have done; but admit it should not be so, my answer might be the same as his. Is there not a cause? nay may I not rather wonder the harvest being so great, that the labourers be so few; if all men should be offended with me for endeavouring the good of all men, in all just wayes (for I professe I know no other cause against me) I should choose it rather then the displeasure of God or the distaste of my owne conscience, affliction being to me a better choice then sin.

And this my judgement (as necessary for that time) I put into writing about 16 monthes since or somewhat more, but deferred the publishing, because it was once denied the Licencing, (which by the way was hard measure, considering how freely aspersers have been Licenced or countenanced against me) but chiefly I omitted to Print it, because I thought my continuall acting towards the common peace, freedome, and safety of the Nation, would yet in time clear off all my reproaches, and for that I could not possibly vindicate my selfe, but that I must necessarily reflect upon some sorts of men, whom I did hope time and their grouth in knowledg would have certified in their judgements concerning me, and the things I ever promoted; But finding now at length, that notwithstanding all times since, I walked in an uprightnesse of heart towards their publique good; without any the least wandering and deviation, (as their Petitioners of the 11 of September will bear me witnesse) notwithstanding I can prove I have rendered very much good, to those that had done me very much evil, and from whom its known I have deserved better things; yet my aspersions after the last Summers troubles were over, flew abroad a fresh, (for in all that time I had very fair words) and now say but Walwin was a Jesuite, and a Pentioner to the Pope, or some Forraigne State: but for proof not one sillable ever proved one while I was a Leveller, then on a sodaine I drove on the King’s designe, and none so countenanced as those that were officious in telling strange stories and tales of me: Insomuch, as I found it had an effect of danger towards my life; divers of the Army giving out, that it would never be well till some dispatch were made of me; that I deserved to be stoned to death; All which, though I considered it to its full value, yet did it not deterre me from pursuing my just Cause, according to my just Judgement and Conscience; but this was my portion from too many, from whom I may truly say, I had deserved better: yet in all these things it was my happinesse to have good esteem from such as I account constant to the Cause, and uncorrupted men of Army and Parliament, to whose love in this kind, for many years, I have been exceedingly obliged, and who never shunned me in any company, nothwithstanding all reproaches, but ever vindicated me, as having undoubted assurance of my integrity; and believing confidently, that I was asperst for no other cause, but for my perpetuall solicitation for the Common-wealth.

But there is no stopping the mouth of corrupt interests, against which only I have ever steered, and not in the least against persons; being still of the same mind I was when I wrote my Whisper in the ear of Mr. Edwards, Minister; professing still, as there in pag: 3. I did, in sincerity of heart; That I am one that do truly and heartily love all mankind, it being my unfeined desire, that all men might be saved, and come to the knowledge of the truth: That it is my extreme grief, that any man is afflicted, molested or punished, and cannot but most earnestly wish them all occasion were taken away—That there is no man weak, but I would strengthen; nor ignorant, but I would reform; nor erroneous, but I would rectifie; nor vicious, but I would reclaim; nor cruel, but I would moderate and reduce to clemency—I am as much grieved that any man should be so unhappy as to be cruel or unjust, as that any man should suffer by cruelty or injustice; and if I could, I would preserve from both.

And however I am mistaken, it is from this disposition in me, that I have engaged in any publique affairs, and from no other—Which my manner of proceeding, in every particular businesse wherein I have in any measure appear’d, will sufficiently evince to all that have, without partiality, observed me.

I never proposed any man for my enemy, but injustice, oppression, innovation, arbitrary power, and cruelty; where I found them, I ever opposed my self against them; but so, as to destroy the evil, but to preserve the person: And therfore all the war I have made, other then what my voluntary and necessary contributions hath maintained, which I have wisht ten thousand times more then my ability; so really am I affected with the Parliaments just cause for the common freedom of this Nation. I say, all the war I have made, hath been to get victory over the understandings of men, accounting it a more worthy and profitable labour to beget friends to the Cause I loved, rather then to molest mens persons, or confiscate mens estates: and how many reall Converts have been made through my endeavours, reproaches might tempt me to boast, were I not better pleased with the conscience of so doing.

Of this mind I was in the year, 1646, and long before; and of the same mind I am at this present; and, I trust, shall ever but be so.

And hence it is, that I have pursued the settlement of the Government of this Nation by an Agreement of the People; as firmly hoping thereby, to see the Common-wealth past all possibility of returning into a slavish condition; though in pursuite thereof, I have met with very hard and froward measure from some that pretended to be really for it: So that do what I will for the good of my native Country, I receive still nothing but evil for my labour; all I speak, or purpose, is construed to the worst; and though never so good, fares the worse for my proposing; and all by reason of those many aspersions cast upon me.

If any thing be displeasing, or judged dangerous, or thought worthy of punishment, then Walwyn’s the Author; and no matter, saies one, if Walwyn had been destroyed long ago: Saies another, Let’s get a law to have power our selves to hang all such: and this openly, and yet un-reproved; affronted in open Court; asperst in every corner; threatned wherever I passe; and within this last month of March, was twice advertised by Letters, of secret contrivances and resolutions to imprison me.

And so accordingly (sutable to such prejudgings and threatnings) upon the 28th of March last, by Warrant of the Councel of State; I that might have been fetcht by the least intimation of their desire to speak with me, was sent for by Warrant under Sergeant Bradshaw’s hand, backt with a strong party of horse and foot, commanded by Adjutant Generall Stubber (by deputation from Sir Hardresse Waller, and Colonel Whaley) who placing his souldiers in the allyes, houses, and gardens round about my house, knockt violently at my garden gate, between four and five in the morning; which being opened by my maid, the Adjutant Generall, with many souldiers, entred, and immediately disperst themselves about the garden, and in my house, to the great terror of my Family; my poor maid comming up to me, crying and shivering, with news that Souldiers were come for me, in such a sad distempered manner (for she could hardly speak) as was sufficient to have daunted one that had been used to such sudden surprisals; much more my Wife, who for two and twenty years we have lived together, never had known me under a minutes restraint by any Authority; she being also so weakly a woman, as in all that time, I cannot say she hath enjoyed a week together in good health; and certainly had been much more affrighted, but for her confidence of my innocence; which fright hath likewise made too deep an impression upon my eldest Daughter, who hath continued sick ever since, my Children and I having been very tender one of another: Nor were my neighbours lesse troubled for me, to whose love I am very much obliged.

The Adjutant Generall immediately followed my maid into my Chamber, as I was putting on my clothes; telling me, that he was sent by the Councel of State (an Authority which he did own) to bring me before them: I askt, for what cause? he answered me, he did not understand particularly, but in the notion of it, it was of a very high nature: I askt him, if he had any warrant? he answered, he had; and that being drest, I should see it.

The Souldiers I perceived very loud in the garden; and I not imagining then, there had been more disperst in my neighbours grounds and houses; and being willing to preserve my credit (a thing sooner bruised then made whole) desired him, to cause their silence, which he courteously did: Then I told him, if he had known me in any measure, he would have thought himself, without any souldiers, sufficient to bring me before them: That I could not but wonder (considering how well I was known) that I should be sent for by Souldiers, when there was not the meanest civil Officer but might command my appearance: That I thought it was a thing not agreeable to that freedom and liberty which had been pretended.

That now he saw what I was, I should take it as a favour, that he would command his Souldiers off, which he did very friendly, reserving some two very civil Gentlemen with him; so being ready, he shewed me the Warrant: the substance whereof was, for suspicion of treason, in being suspected to be the Author of a Book, entituled, The second part of Englands new Chains discovered: I desired him to take a Copy of it, which was denied, though then and afterwards by my self, the Lieut. Col. John Lilburn (who was likewise in the same Warrant) importuned very much for.

Then I went out with him into Moor-Fields, and there I saw, to my great wonder, a great party of souldiers, which he commanded to march before, and went with me, (only with another Gentleman, at a great distance) to Pauls; yet such people as were up, took so much notice of it, as it flew quickly all about the Town; which I knew would redound much to my prejudice, in my credit; which was my only care, the times being not quallified for recovery of bruises in that kind.

In Pauls Church-yard was their rendezvous; where I was no sooner come, but I espied my Friends, Mr Lilburn and Mr Prince, both labouring to convince the souldiers of the injury done unto us, and to themselves, and to posterity, and the Nation in us: in that they, as souldiers, would obey and execute commands in seizing any Freeman of England, not Members of the Army, before they evidently saw the civil Magistrates and Officers in the Common-wealth, were resisted by force, and not able to bring men to legall trials, with very much to that purpose; and in my judgment, prevailed very much amongst them; many looking, as if they repented and grieved to see such dealings.

Then they removed to a house for refreshment, where, after a little discourse, we perswaded them to release two of Mr Davenish his sons, whom a Captain had taken into custody without Warrant: but that kind of errour being laid fully open, they were enlarged with much civility, which I was glad to see, as perceiving no inclination in the present Officers or Souldiers, to defend any exorbitant proceedings, when this understood them to be such.

So the Adjutant Generall sent off the whole party, and with some very few, took us, by water, to his Quarters at Whitehall (where after a while, came in Mr Overton) the Adjutant intending about nine of the clock, to go with us to Darby house.

But the Councel not sitting till five at night, we were kept in his Quarters all that time; where some, but not many of our friends that came to visit us, were permitted.

About five a clock, the Councel sate; so he took us thither, where we continued about two houres, before any of us were called in; and then Mr Lilburn was called, and was there about a quarter of an hour, and then came out to us, and his Friends, declaring at large all that had past between him and them.

Then after a little while, I was called in, and directed up to Sergeant Bradshaw the President; who told me, that the Parliament had taken notice of a very dangerous Book, full of sedition and treason; and that the Councel was informed, that I had a hand in the making or compiling thereof; that the Parliament had referred the enquiry and search after the Authors and Publishers, to that Councel; and that I should hear the Order of Parliament read, for my better satisfaction: so the Order was read, containing the substance of what the President had delivered; and then he said, by this you understand the cause wherfore you are brought hither; and then was silent, expecting, as I thought, what I would say.

But the matter which had been spoken, being only a relation, I kept silence, expecting what further was intended; which being perceived, the President said. You are free to speak, if you have any thing to say to it: to which I said only this, I do not know why I am suspected: Is that all, said he: To which I answered. Yes; and then he said. You may withdraw: So I went forth.

And then Mr Overton, and after him, Mr Prince, were called in; and after all four had been out a while, Mr Lilburn was called in again, and put forth another way; and then I was called in again:

And the President said to this effect, that the Parliament had reposed a great trust in them for finding out the Authors of that Book; and that the Councel were carefull to give a good accompt of their trust; in order whereunto, I had been called in, and what I had said, they had considered; but they had now ordered him to ask me a question, which was this: Whether or no I had any hand in making or compiling of this Book? holding the Book in his hand: To which, after a little while, I answered to this effect. That I could not but very much wonder to be asked such a question; howsoever, that it was very much against my judgment and conscience, to answer to questions of that nature which concem’d my self; that if I should answer to it, I should not only betray my own liberty, but the liberties of all Englishmen, which I could not do with a good conscience: And that I could not but exceedingly grieve at the dealing I had found that day; that being one who had been alwaies so faithfull to the Parliament, and so well known to most of the Gentlemen there present, that neverthelesse I should be sent for with a party of horse and foot, to the affrighting of my family, and ruine of my credit; and that I could not be satisfied, but that it was very hard measure to be used thus upon suspicion only; professing, that if they did hold me under restraint from following my businesse and occasions, it might be my undoing, which I intreated might be considered.

Then the President said, I was to answer the question; and that they did not ask it, as in way of triall, so as to proceed in judgment thereupon, but to report it to the House: To which I said, that I had answered it so as I could with a good conscience, and could make no other answer; so I was put forth a back way, as Mr Lilburn had been, and where he was.

After this, they cal’d in Mr Overton, and after him Mr Prince, using the very same expressions, and question to all alike; and so we were all four together; and after a long expectance, we found we were committed Prisoners to the Tower of London, for suspicion of high treason; where now we are, to the great rejoycing of all that hate us, whose longing desires are so far satisfied: And to make good that face of danger, which by sending so many horse and foot was put upon it, a strong Guard hath ever since been continued at Darby house, when the Councel sits.

And now again, fresh aspersions and reproaches are let loose against us, and by all means I, that never was beyond the Seas, nor ever saw the Sea, must be a Jesuite, and am reported to be now discovered to be born in Spain: That because I am an enemy to superstition, therfore they give out, I intend to destroy all Religion; and (which I never heard till now) that I desire to have all the Bibles in England burnt; that I value Heathen Authors above the Scriptures: whereas all that know me, can testifie how, though I esteem many other good Books very well, yet, I ever prefer’d the Scriptures; and I have alwaies maintained, that Reason and Philosophy could never have discovered peace and reconciliation by Christ alone, nor do teach men to love their enemies; doctrines which I prize more then the whole world: It seems I am used so ill, that except by aspersions I be made the vilest man in the world, it will be thought, I cannot deserve it: And though I were, yet (living under a civil Government) as I hope, I ever shall do, and not under a Military, I cannot discern how such dealing could be justified: For, admit any one should have a mind to accuse me of treason, the party accusing ought to go to some Justice of the Peace, dwelling in the County or hundred, and to inform the fact; which if the Justice find to be against the expresse law, and a crime of treason; and that the accuser make oath of his knowledge of the fact; then the Justice may lawfully give out a Warrant, to be served by some Constable, or the like civil Officer, to bring the party accused before him, or some other Justice: wherein the party accused is at liberty to go to what Justice of Peace he pleaseth; and as the matter appeareth when the parties are face to face before a Justice, with a competent number of friends about him to speak in his behalf, as they see cause, his house being to be kept open for that time; then the Justice is to proceed as Laws directeth, as he will answer the contrary at his perill; being responsible to the party, and to the Law, in case of any extra-judiciall proceeding; and the Warrant of attachment and commitment ought to expresse the cause of commitment in legall and expresse tearms, as to the very fact and crime; and to refer to the next Gaol delivery, and not at pleasure.

Whereas I was fetcht out of my bed by souldiers, in an hostile manner, by a Warrant, expressing no fact that was a crime by any law made formerly, but by a Vote of the House, past the very day the Warrant was dated: Nor was I carried to a Justice of the Peace, much lesse to such a one as I would have made choyce of, where my Accuser (if any) was to appear openly face to face, to make oath of fact against me, if any were, but before a Councel of State, where I saw no Accuser face to face, nor oath taken, nor my friends allowed to be present, nor dores open; but upon a bare affirmation that the Councel was informed that I had a hand in compiling a Book, the title nor matter whereof was not mentioned in any law extant: whereas treason by any law, is neither in words nor intents, but in deeds and actions, expresly written, totidem verbis, in the law. And after, being required to answer to a question against my self, in a matter (avouched by Vote of Parliament to be no lesse then Treason) was committed Prisoner, not to a common County prison, (nor for the time) referred to the next Gaol delivery, by the ordinary Courts of Justice, my birthright, but to the Tower of London, during pleasure, preferred to be tryed by the upper Bench, whereas treason is triable only in the County where the fact is pretended to be committed.

All which I have laboured with all the understanding I have, or can procure, to make appear to be just and reasonable, but cannot as yet find any satisfaction therin; being clear in my judgment, that a Parliament may not make the people lesse free then they found them, but ought at least to make good their liberties contained in Magna Charta, the Petition of Right, and other the good Laws of the Land, which are the best evidences of our Freedoms. Besides, I consider the consequence of our Sufferings; for in like manner, any man or woman in England is liable to be fetcht from the farthest parts of the Land, by parties of horse and foot, in an hostile manner, to the affrighting and ruining of their Families; and for a thing, or act, never known before by any Law to be a crime, but voted to be so, only the very day perhaps of signing the Warrent: And therfore that such power can be in this, or any other Parliament; or that such a kind of proceeding can be consistent with freedom, I wish any would give me a reason that I might understand it; for certainly the meer voting of it, will hardly give satisfaction: And now I well perceive, they had good ground for it, who asserted this belief into the first Agreement of the people; namely,

That as the laws ought to be equall, so they must be good, and not evidently destructive to our liberties; and I wish that might be well considered in making of any Law: And likewise. That no Law might be concluded, before it be published for a competent time; that those who are so minded, might offer their reasons either for or against the same, as they see cause: But I forget my self, not considering that my proposing of this, will be a means to beget a dislike thereof, and may possibly work me some new aspersions.

I am said likewise to have worse opinions then this; whereof one is, That I hope to see this Nation governed by reason, and not by the sword.

Nay worse yet; That notwithstanding all our present distractions, there is a possibility upon a clear and free debate of things, to discover so equall, just and rationall Propositions, as should produce so contentfull satisfaction, and absolute peace, prosperity and rest to this Nation; as that there should be no fear of man, nor need of an Army; or at worst, but a very small one.

But if I should declare my mind in this more fully, it would, as other good motions and propositions of mine have done, beget me the opinion of a very dangerous man, and some new aspersion; there being some, whose interest must not suffer it to be believed.

And yet it may be true enough; for I could instance a Country, not so surrounded with Seas as ours is, nor so defensible from Enemies, but that is surrounded with potent Princes and States, and was as much distracted with divisions as ours at present is, yet by wisdom so order themselves, as that they keep up no Army, nor dread no war, but have set the native Militia in such a posture, as that all the Countries round about them dare not affront them with the least injury; or if they do, satisfaction being not made, upon demand, in 48 hours, a wel disciplin’d Army appears in Field to do themselves justice; it being a maxim and principle among them, to do no injury, nor to suffer any the least from Forraigners; as also, not to let passe, without severe exemplar punishment, the least corruption in publique Officers and Magistrates; without a due regard unto both which, it is impossible for any people to be long in safety; and to hold authority, or command beyond the time limited by law, or Commission amongst them, is a capitall offence, and never fails of punishment: So that this opinion of mine is not the lesse true because I hold it, but is of the number of those many usefull ones, that this present age is not so happy as to believe: Nor are we like to be happier, till we are wiser.

But as subject as some would make me to vain opinions, there is one that hath been creeping upon us about eight months, which yet gets no hold upon me; and that is. That the present power of the Sword may reign; from this ground, that the power which is uppermost is the power of God; and the power of the Sword being now (as some reason) above the civil Authority, it is therfore the power of God: But the greatest wonder in this, is, that some Anabaptists who are descended from a people so far from this opinion, that they abhorred the use of the sword, though in their own defence (to such extremities are people subject to, that think themselves to have all knowledge and religion in them, when in truth it is but imagination and Scripture). As for me, I am of neither of these opinions, but should be glad once-again to see the sword in its right place, in all senses; and the civil Authority to mind as well the essence as the punctilio’s and formalities, but neglecting neither; and that the People would be so far carefull of their own good, as to observe with a watchfull eie, the right ordering and disposing both of the civill and military power; we having no warrant to argue that to be of God, but what is justly derived, attained and used to honest means; the ends, I mean, of all Government, viz. the safety, peace, freedom and prosperity of the people governed; whereas otherwise. Tyrants, Theeves, out-laws, Pirats and Murtherers, by the same kind of arguing, may prove themselves to be of God; which in reall effect, perverts the whole supreme intent of Government, being constituted every where for the punishment and suppression of all evil and irregular men.

But why spend I my time thus, in clearing mens understandings, that so they might be able to preserve themselves from bondage and misery, being so ill requited for my labour? Nay that might have thanks, and other good things besides, if I would forbear? To which truly I have nothing to say, but that my conscience provokes and invites me to do what I do, and have done in all my motions for the Common-wealth; nor have I, I blesse God, any other reason; and which to me is irresistible; unlesse I should stifle the power of my conscience, which is the voyce of God in me, alwaies accusing or excusing me: So that whil’st I have opportunity, I shall endeavour to do good unto all men.

But I have other businesse now upon me, then ever I had, being now in prison, which (I praise God for it) I never was in my life before; where though I think I have as much comfort as another, yet it is not a place I like, and therfore am carefull how to become free as soon as I can, my restraint being very prejudiciall to me; especially considering how the corruptions of some false hearted people doth now break out against me, in renewed clamours and aspersions; which whil’st I labour to acquit my self of it, it proves to me like the laving of the ever-flowing Fountain of Slander; the invective brain of some resolved Politicians; for I see I must be asperst, till honesty gets the victory of policy, and true Religion over superstition; the one being the Inventer, and the other the Disperser, as the fore-going discourse will, I judge, sufficiently demonstrate: And therfore henceforth let men say and report what evil they will of me, I shall not after this regard it, nor trouble my self any more in this way of vindication, hoping to find some other way.

Only one aspersion remains, which I thought good to quit here; which is, that I am a Pentioner to some forraign State; which indeed is most false, and is invented for the end, as all the rest are, to make me odious: And truly if men were not grown past all shame, or care of what they said or heard of me, it would be impossible to get belief, for which way doth it appear? I think, nay am sure, that in my house no man (bred in that plenty I was) ever contented himself with lesse, which is easily known—and for the apparell of my self, my Wife and Children, if it exceed in any thing, it is in the plainesse, wherewith we are very well satisfied; and so in houshold stuff, and all other expenses; and for my charge upon publique, voluntary occasions, I rather merit a charitable construction from those I have accompanied with, then any thanks or praise for any extraordinary disbursments: and I am sure I go on foot many times from my house to Westminster, when as I see many inferiour to me in birth and breeding, only the favorites of the times, on their stately horses, and in their coaches; and when I have been amongst my Friends in the Army, as many times I have had occasion, I must ever acknowledge that I have received amongst them ten kindnesses for one; and yet (not to wrong my self) I think, nay am sure, there is not a man in the world that is of a more free or thankfull heart; and have nothing else to bear me up against what good and worthy men (whom I have seen in great necessities) might conjecture of me, when as I have administred nothing to relieve them—when was the time, and where the place, I gave dinners or suppers, or other gifts? For shame, thou black-mouth’d slander, hide thy head, till the light of these knowing times be out; all that thou canst do, is not sufficient to blast me amongst those with whom I converse, or who have experience of my constancy in affection & endeavour to the generall good of all men, but to thy greater torment & vexation, know this, they that entirely love me for the same, are exceedingly increased, and many whom thou hadst deceived, return daily, manifesting their greater love to me and the publique, as willing to recompence the losse of that time thou deceivedst them.

And this imprisonment, which thou hast procured me, for my greater and irrecoverable reproach amongst good men; thy poyson’d heart would burst to see how it hath wrought the contrary, so far, as I never had so clear a manifestation of love and approbation in my life, from sincere single-hearted people, as now to my exceeding joy I find.

And possibly for time to come, these notorious falshoods with which the slanderous tongue hath pursued me, may have the same effect upon these weak people thou makest thy instruments, which they have had upon me; and that is. That I am the most backward to receive a report concerning any mans reputation, to his prejudice, of any man in the world, and account it a basenesse to pry into mens actions, or to listen to mens discourses, or to report what I judge they would not have known, as not beseeming a man of good and honest breeding, or that understands what belongs to civil society.

But leaving these things, which I wish I had had no occasion to insist upon, it will concern me to consider the condition I am in; for though I know nothing of crime or guilt in my self, worthy my care, yet considering how, and in what an hostile manner I was sent for out of my bed and house, from my dear Wife and Children; the sense of that force and authors of my present imprisonment, shewing so little a sencibility or fellow-feeling of the evils that might follow upon me and them, by their so doing; it will not be a misse for me to view it in the worst cullers it can bear.

As for the booke called The second part of Englands new chaines discovered: for which Lieut. Col. John Lilburn, Mr Prince, Mr Overton and my self are all questioned: it concernes me nothing at all, farther then as the matter therein contained agreeth or disagreeth with my judgement; and my judgement will work on any thing I read in spight of my heart; I cannot judge what I please, but it will judge according to its owne perceverance.

And to speake my conscience, having read the same before the Declaration of Parliament was abroad; I must professe I did not discerne it to deserve a censure of those evils which that Declaration doth import, but rather conceived the maine scope and drift thereof tended to the avoiding of all those evils: and when I had seen and read the Declaration, I wished with all my heart, the Parliament had been pleased for satisfaction of all those their faithfull friends who were concerned therein, and of the whole Nation in generall: To have expresly applied each part of the book to each censure upon it, as to have shewed in what part it was false, scandalous, and reproachfull; in what seditious, and destructive to the present Government, especially since both Parliament and Army, and all wel affected people have approved of the way of settlement of our Government, by an Agreement of the People.

Also that they had pleased to have shewed what part, sentence or matter therein, tended to division and mutiny in the Army, and the raising of a new War in the Common-wealth: or wherein to hinder the relief of Ireland, and continuing of Free-quarter; for certainly it would conduce very much to a contentfull satisfaction, to deal gently with such as have been friends in all extremities; and in such cases as these to condescend to a fair correspondency, as being willing to give reasons in all things, to any part of the people; there being not the least or most inconsiderable part of men that deserve so much respect, as to have reason given them by those they trust, and not possitively to conclude any upon meere votes and resolutions: and in my poor opinion had this course been taken all along from the beginning of the Parliament to this day, many of the greatest evils that have befalne, had been avoided; the Land ere this time had been in a happy and prosperous condition.

There being nothing that maintaines love, unity and friendship in families; Societies, Citties, Countries, Authorities Nations; so much as a condescention to the giving, and hearing, and debating of reason.

And without this, what advantage is it for the people to be, and to be voted the Supreme power? it being impossible for all the people to meet together, to speak with, or debate things with their Representative; and then if no part be considerable but only the whole, or if any men shall be reckoned slightly of in respect of opinions, estates, poverty, cloathes; and then one sort shall either be heard before another: or none shall have reasons given them except they present things pleasing: the Supreme power, the People, is a pittifull mear helplesse thing; as under School-masters being in danger to be whipt and beaten in case they meddle in things without leave and licence from their Masters: and since our Government now inclines to a Commonwealth, ’twere good all imperiousnesse were laid aside, and all friendlinesse hereafter used towards the meanest of the people especially (if Government make any dissention at all.)

And truly I wish there had been no such imperious courses taken in apprehending of me, nor that I had been carried before the Councell of State; nor that the Declaration had been so suddenly and with such solemnity proclaimed upon our commitment, there being no harsh expression therein; but what through the accustomed transportation of mens spirits towards these that suffer, but is applied to us, so that we are lookt upon as guilty already of no lesse then Mutiny, Sedition, and Treason; of raising a new War, or hindering the relief of Ireland, and continuance of Free-quarter; insomuch as though now we shall be allowed a legall triall in the ordinary Courts of Justice: as certainly the times will afford us that, or farewell all our rights and liberty, so often protested and declared to be kept inviolable; and within these two years so largely promised to be restored and preserved: yet what Judge will not be terrified and preposest by such a charge laid upon us by so high an Authority, and attached by Soldiers, and sent Prisoners to the Tower: nay what Judge will not be prejudiced against us?

If they should be persons relating to the Army, we are represented as Mutineers: if to the present actings in Government, to such we are represented as seditious and destructive: if such as are sensible of the losse of Trade, who can be more distrustfull to them then those that are said to raise a new Warre: if any of them should be of those who are engaged in the affairs of Ireland, to these we are represented as hinderers of the relief of Ireland: and what punishment shall seeme too great for us, from such as have been tired and wasted with Freequarter? who are pointed out to be the continuers thereof: if any Jurymen should be of that sort of men who stile themselves of the seaven Churches of God, what equity are we like to finde from them who have already engaged against us, by their Pharisaicall Petition, for though they name us not, yet all their discourses point us out as the princiapall persons therein complained of; an ill requitall for our faithfull adherence unto them in the worst of times, and by whose endeavours under God they attained to that freedome they now enjoy; and can Churches prove unthankfull? nay watch a time when men are in prison to be so unthankfull as to oppose their enlargement? what to wound a man halfe dead by wounds? a Priest or Levite would have been ashamed of such unworthinesse: what, Christians that should be full of love, even to their enemies, to forget all humanity, and to be so dispightfull to frinds? alas, alas, for Churches that have such Pastors for their leaders; nay for Churches of God to owne such kind of un-Christian dealing: Churches of God, so their Petition denominates them; if the tree should be judged by his fruit, I know what I could say, but I am very loath to grive the spirits of any welmeaning people: and know there are whole societies of those that call themselves Churches, that abhor to be thought guilty of such unworthinesse; Mr Lamb a pastor at the Spittle, offering upon a free debate, to prove the presenters of the Petition guilty of injustice, arrogance, flattery, and cruelty: ye many members of these seven Churches, that have protested against it; and many more that condemn them for this their doing, to whom I wish so much happinesse as they will seriously consider how apt in things of this civil nature, these their Pastors have been to be mistaken, as they were when they misled them not very long since to Petition for a Personall Treaty, which I would never thus have mentioned but that they persist for by-ends, offices or the like (it may be) to obstruct all publick-good proceedings, and to maligne those, who without respect of persons or opinions, endeavour a common good to all men. And truly to be thus fore-laied; and as it were prejudg’d by Votes, and Declarations, and Proclamations of Parliament, under such hideous notions of sedition and Treason; apprehended in so formidable a way, and imprisoned in an extraordinary place, no Bayle being to be allowed: and after all these to be renounced and disclaimed by the open mouthes of the Pastors, and some members of seven Churches assuming the title of the Churches of God; are actions that may in one respect or other, worke a prejudicate opinion of us, in any jury that at this day may or can be found.

So as I cannot but exceedingly prefer the ordinary way of proceedings (as of right is due to every English-man) in Criminall cases by Justices of the Peace, which brings a man to a Triall in an ordinary way, without those affrightments and prejudgings which serve only to distract the understanding, and bias Justice, and to the hazarding of mens lives in an unreasonable manner, which is a consideration not unworthy the laying to heart of every particular person in this Nation; for what is done to us now, may be done to every person at any time at pleasure.

Neverthelesse, neither I nor my partners in suffering are any whit doubtfull of a full and clear Vindication, upon a legall triall; for in my observation of trials I have generally found, Juries and Jury-men to be full of conscience, care, and circumspection, and tendernesse in cases of life and death; and I have read very remarkable passages in our Histories; amongst which the Case and Triall of Throckmorton, in Queen Maries time is most remarkeable: the consciences of the Jury being proof against the opinion of the Judges, the rhetorick of the Councell who were great and Learned, nay against the threats of the Court, which then was absolute in power and tyranny, and quit the Gentleman, like true-hearted, wel-resolved English-men, that valued their consciences above their lives; and I cannot think but these times, will afford as much good conscience, as that time of grosse ignorance and superstition did: and the liberty of exception against so many persons returned for Jury-men, is so mighty a guard against partaking, that I cannot doubt the issue.

Besides since in Col. Martin’s Case, a worthy Member of Parliament, it is clear that Parliaments have been mistaken in such censures, as appears by his restauration, and razing all matters concerning his Sentence out of the House Book: And since the Parliament revoked their Declaration against the Souldiers Petitioning in the beginning of the year, 1647 as having been mistaken therein: since they have so often imprisoned Mr Lilburn my fellow Prisoner, and some others, and have after found themselves mistaken; yea since some of these Gentlemen who now approve of the way of an Agreement of the People, as the only way to give rest to the Nation; about a year since voted it destructive to Parliaments, and to the very being of all Governments, imprisoning divers for appearing in behalf thereof.

I am somewhat hopefull, that a Jury will not much be swaied by such their sudden proceedings towards us; as not perfectly knowing, but that they may also have been mistaken concerning us now; for it was never yet known, that Mr Lilburn, or I, or any of us, ever yet had a hand in any base, unworthy, dangerous businesse: though sometimes upon hasty apprehensions and jealousies of weak people, we have been so rendred: But (be this businesse what it wil) I do not know why I should be suspected in the least, and can never sufficiently wonder at this their dealing towards me.

And as for any great hurt the Pastors of the seven Churches are like to do, by their petitioning against us, though their intentions were very bad and vile, yet considering how few of their honest members approve thereof, and that the high esteem of the Church-way is a most worn out, being not made (as the Churches we reade of in Scriptures) of everlasting, but fading matter; as the Book, entituled. The vanity of the present Churches, doth fully demonstrate: a little consideration of these things by any Jury, will easily prevent the worst they intended: Wherein also, possibly, they may deserve some excuse, as being (probably) mis-led thereto by the same politique councels, as drew them in, to petition for a Personall Treaty: Such as these being fit instruments for Politicians; as in the former part of this Discourse is evinced.

But, be it as it may, if I be still thought so unworthy as to deserve a prosecution, a fair legall triall by twelve sworn men of the neighbourhood, in the ordinary Courts of Justice, is all I desire (as being even more willing to put myself upon my Country, then on the Court, or any the like Prerogative way) and have exceeding cause to rejoyce in the sincere affection of a multitude of Friends, who out of an assured confidence of our integrity, and sensible of the hard measure we have found, and of the prejudice our present imprisonment might bring upon us, did immediately bestir themselves, and presented a Petition for our present enlargement with a speedy legall triall: whose care and tender respects towards us, we shall ever thankfully acknowledge: But the seven Churches were got before them, and had so much respect, that our Friends found none at all; but what remedy but patience? all things have their season, and what one day denies, another gives.

And so I could willingly conclude, but that I shall stay a little to take in some more aspersions, which are brought in apace still, and I would willingly dispatch them.

I and my fellow prisoners are now abused, and that upon the Exchange, by the mouths of very godly people; so it must run. That say, all our bustlings are, because we are not put into some Offices of profit and Authority, and if we were once in power, we would be very Tyrants: But pray. Sirs, you that are at this loosenesse of conscience, why produce you not the Petitions we presented to your Patrons? Why tell you not the time and place, where we solicited for any advantage to our selves? But allow we had done so, with what faces can you reprove us? For shame pluck out the beams out of your own eies, you that have turned all things upside down for no other end, and run continually to and fro to furnish your selves and Friends, thrusting whole families out to seek their bread, to make room for you. And how appears it, that if we were in any power and Authority we would be very Tyrants? We never sought for any, and that’s some good sign; those who do, seldom using it to the good of the publique: And for ought is seen, we might have had a large share if we would have sought it; but account it a sure rule, that into Muse as they use: So generally true is it, that the Asperser is really guilty of what he forgeth against another: And that this may appear, let all impartiall people but look about them, and consider what and who they are, that seek most after offices and power, and how they use them when they have them; and then say, whether those that asperse us, or we who are aspersed, do most deserve this imputation.

Nay, we find by experience, that we are reproacht scarce by any, but such as are engaged in one kind of corrupt interest or other; either he hath two or three offices or trusts upon him, by which he is enriched and made powerfull; or he hath an office in the excise, or customs; or is of some monopolizing company; or interested in the corruption of the laws; or is an encloser of fens, or other commons; or hath charge of publique monies in his hands, for which he would not willingly be accomptable; or hath kept some trust, authority or command in hand longer then commission and time intended; or being in power, hath done something that cannot well be answered; or that hath money upon usury in the excise; or that makes title of tythes, and the like burthenous grievances; or else such as have changed their principles with their condition; and of pleaders for liberty of Conscience, whil’st they were under restraint, and now become persecutors, so soon as they are freed from disturbance; or some that have been projectors, still fearing an after-reckoning; or that have received gifts, or purchased the publique lands at undervalues.

And we heartily wish, that all ingenuous people would but enquire into the interest of every one they hear asperse us; the which if they clearly do, it’s ten to one the greatest number of them by far, will prove to belong to some of those corrupt interests forenamed; and we desire all men to mark this in all places: And the reason is evident, namely, because they are jealous (our hands being known to be clear from all those things) that by our, and our Friends means, in behalf of the common good, first or last, they shall be accomptable; and if those who hear any of these exclaiming against us would but tread, their corrupt interests a little upon the toe where the shoe pinches, they might soon have reason of them, and they will be glad to be silent: and this is a medicine for a foul mouth, I have often used very profitably.

And now comes one that tels me, it’s reported by a very godly man, that I am a man of a most dissolute life, it being common with me to play at Cards on the Lord’s day; there is indeed no end of lying and backbiting; nor shame in impudence, or such palpable impostors could never be beleived; and I am perswaded the Inventers would give a good deal of money I were indeed addicted to spend my time in gaming, drinking or loosnesse; from which I praise God, he hath alwaies preserved me, and hath so inclined my mind and disposition, as that it takes pleasure in nothing but what is truly good and virtuous; the most of my recreation being a good Book, or an honest and discoursing Friend: Other sports and pastimes that are lawfull and moderate, though I allow them well to yet I have used them as seldom my self as any man, I think, hath done: But I see, slander will have its course; and that a good conscience, and a corrupt interest can no more consist in one and the same person, then Christ and Belial.

And for a conclusion to all these scandals, it is imposed upon us, that we are an unquiet, unstaied people, that are not resolved what will satisfie us; that we know not where to end, or what to fix a bottom upon—and truly this hath been alwaies the very language of those, who would keep all power in their hands, and would never condescend to such an issue as could satisfie; such as would content themselves with the least measure of what might justly be called true freedom: But what sort of men ever offered at, or discovered so rationall a way for men to come to so sure a foundation for peace and freedom, as we have done and long insisted on, namely, by an Agreement of the People, and unto which we all stand: As for the way, and as to the matter, we have been long since satisfied in our selves, but our willingnesse to obtain the patronage of some thereto, instead of furtherance, procur’d its obstruction: Because we cannot submit to things unreasonable, and unsafe in an Agreement, shall any brand us, that we are restlesse, and have no bottom? Certainly it had been time enough for such an aspersion, if there had been a joynt and free consent to what was produc’t and insisted on by others.