THE PUTNEY DEBATES

The General Council of Officers

at Putney (Oct.-Nov. 1647)

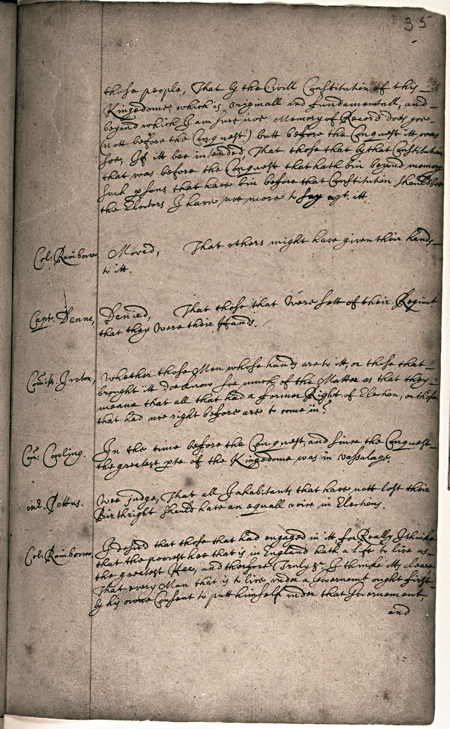

Page from the Putney debates record book, 1647, located at Worcester College, Oxford, MS 65 ff.34v-35r, showing the handwritten record of the conversation. Worcester College, Oxford.

[Created: 4 February, 2021]

[Updated: 22 July, 2024] |

Source

, The Clarke Papers. Selections from the Papers of William Clarke, Secretary to the Council of the Army, 1647-1649, and to General Monck and the Commanders of the Army in Scotland, 1651-1660, ed. C.H. Firth (Camden Society, 1891-1901). Volume 1 (1891).http://davidmhart.com/liberty/T111-PutneyDebates.html

The Clarke Papers. Selections from the Papers of William Clarke, Secretary to the Council of the Army, 1647-1649, and to General Monck and the Commanders of the Army in Scotland, 1651-1660, ed. C.H. Firth (Camden Society, 1891-1901). 4 vols. Volume 1 (1891) includes the "Putney Debates" (28 October - 11 November 1647), pp. 226-428.

The complete text of The Clarke Papers, vol. 1 in HTML [Online] (Levellers/ClarkePapers/ClarkePapers1-1891.html).

This text contains the following parts:

- Discussion of 28 Oct. 1647

- The Answer of the Agitators read

- Discussion of 29 Oct. 1647

- The Paper called The Agreement read

- Discussion of Saturday 30 Oct. 1647

- Discussion of 1 Nov. 1647

- Discussion of 2 Nov. 1647

- At the Committee of Officers appointed by the General Council (3 Nov. 1647)

- Discussion of 8 Nov. 1647

- Desires of the Army

- Discussion of 9 Nov. 1647

- Discussion of 11 Nov. 1647

ID Number

T.111 [Several Hands] [1647.10] The Putney Debates. The General Council of Officers at Putney (October/November 1647).

Collection

This pamphlet/tract is part of a collection of Leveller Tracts.

Note: The page numbers refer to the page numbering in the original pamphlet. Sometimes page numbers were missing or there were duplicates. On many occasions the text in the margin notes is unreadable as a result of poor scanning of the original.

Table of Contents

- Att the Generall Councill of Officers att Putney. 28 October, 1647.

- The Answer of the Agitators read.

- The Answer of the Agitators, the 2d time read.

- Att the Meeting of the officers for calling uppon God, according to the appointment of the Generall Councill, after some discourses of Commissary Cowling, Major White, and others.

- The Paper called the Agreement read.

- Att the Committee of Oficers att the Quartermaster Generalls.

- Att the Committee of Officers appointed to consider of the Agreement, and compare itt with Declarations.

- Att the Generall Councill of the Army.

- Att the Meeting of the Committee.

- Att the Committee of Officers appointed by the Generall Councill

- [Desires of the Army.]

- Generall Councill.

- Att the 2d Meeting of the Committee of Officers appointed by the Generall Councill.

- Endnotes

The Putney Debates (28 Oct. - 11 Nov. 1647)

[226]

Att the Generall Councill of Officers att Putney. 28 October, 1647.↩

The Officers being mett, first said,

Lieutennant General Cromwell. [321]

That the Meeting was for publique businesses. Those that had anythinge to say concerning the publique businesse might have libertie to speake.

Mr. Edward Sexby.

Mr. Allen, Mr. Lockyer, and my self are three.

They have sent two Souldiers, one of your owne Regiment and one of Col. Whalley’s, with two other Gentlemen, Mr. Wildman and Mr. Petty.

Commissary General Ireton.

That hee had nott the paper of what was done uppon all of them.

Itt was referr’d to the Committee, that they should consider of the paper that was printed, “The Case of the Army Stated,” and to examine the particulars in itt, and to represent and offer somethinge to this Councill about itt. [322] They were likewise appointed [227] to send for those persons concern’d in the paper. The Committee mett according to appointment that night. Itt was only then Resolv’d on, That there should bee some sent in a freindlie way (nott by command, or summons) to invite some of those Gentlemen to come in with us, I thinke.

Mr. Sexby.

I was desired by the Lieutennant Generall to [let him] know the bottome of their desires. They gave us this answer, that they would willinglie draw them uppe, and represent them unto you. They are come att this time to tender them to your considerations with their resolutions to maintaine them.

Wee have bin by providence putt upon strange thinges, such as the ancientist heere doth scarce remember. The Army acting to these ends, providence hath bin with us, and yett wee have found little [fruit] of our indeavours; and really I thinke all heere both great and small (both Officers and Souldiers), wee may say wee have lean’d on, and gone to Egypt for helpe. The Kingdomes cause requires expedition, and truly our miseries with [those of] our fellow souldiers’ cry out for present helpe. I thinke, att this time, this is your businesse, and I thinke itt is in all your hearts to releive the one and satisfie the other. You resolv’d if any thinge [reasonable] should bee propounded to you, you would joyne and goe alonge with us.

The cause of our misery [is] uppon two thinges. We sought to satisfie all men, and itt was well; butt in going [about] to doe itt wee have dissatisfied all men. Wee have labour’d to please a Kinge, and I thinke, except wee goe about to cutt all our throates, [228] wee shall nott please him; and wee have gone to support an house which will prove rotten studds, [323] I meane the Parliament which consists of a Company of rotten Members.

And therfore wee beseech you that you will take these thinges into your consideration.

I shall speake to the Lieut. Generall and Commissary Generall concerning one thinge. Your creditts and reputation hath bin much blasted uppon these two considerations. The one is for seeking to settle this Kingdome in such a way wherein wee thought to have satisfied all men, and wee have dissatisfied them—I meane in relation to the Kinge—The other is in referrence to a Parliamentarie aucthoritie (which most heere would loose their lives for), to see [324] those powers to which wee will subject our selves loyally called. These two things are as I thinke conscientiously the cause of all those blemishes that have bin cast uppon either the one or the other. You are convinc’t God will have you to act on, butt [ask] onelie to consider how you shall act, and [take] those [ways] that will secure you and the whole Kingdome. I desire you will consider those thinges that shall bee offer’d to you; and, if you see any thinge of reason, you will joyne with us that the Kingdome may bee eas’d, and our fellow souldiers may bee quieted in spiritt. These thinges I have represented as my thoughts. I desire your pardon.

[229]

Lieut. Generall.

I thinke itt is good for us to proceede to our businesse in some order, and that will bee if wee consider some things that are latelie past. There hath bin a booke printed, called, “The Case of the Armie Stated,” and that hath bin taken into consideration, and there hath bin somewhat drawne uppe by way of exception to thinges contayn’d in that booke; and I suppose there was an Answer brought to that which was taken by way of exception, and yesterday the Gentleman that brought the Answer hee was dealt honestly and plainly withall, and hee was told, that there were new designes a driving, and nothing would bee a clearer discovery of the sincerity of [their] intentions, as their willingnesse that were active to bringe what they had to say to bee judg’d of by the Generall Officers, and by this Generall Councill, that wee might discerne what the intentions were. Now itt seemes there bee divers that are come hither to manifest those intentions according to what was offer’d yesterday, and truly I thinke, that the best way of our proceeding will bee to receive what they have to offer. Onely this, Mr. Sexby, you were speaking to us two. [i do not know why you named us two,] except you thinke that wee have done somewhat or acted somewhat different from the sence and resolution of the Generall Councill. Truly, that that you speake to, was the thinges that related to the Kinge and thinges that related to the Parliament; and if there bee a fault I may say itt, and I dare say, itt hath bin the fault of the Generall Councill, and that which you doe speake both in relation to the one and the other, you speake to the Generall Councill I hope, though you nam’d us two, Therfore truly I thinke itt sufficient for us to say, and ’tis that wee say—I can speake for my selfe, lett others speake for them selves—I dare maintaine itt, and I dare avowe I have acted nothing butt what I have done with the publique consent, and approbation and allowance of the Generall Councill. That I dare say for my self, both in relation to the one, and to the other. What I have acted in Parliament in the name of the Councill or of the Army I have [230] had my warrant for from hence. What I have spoken in another capacitie, as a Member of the House, that was free for mee to doe; and I am confident, that I have nott used the name of the Army, or interest of the Army to anythinge butt what I have had allowance from the Generall Councill for, and [what they] thought itt fitt to move the House in. I doe the rather give you this account, because I heare there are some slanderous reports going uppe and downe uppon somewhat that hath bin offer’d to the House of Commons [by me], as being the sence and opinion of this Armie, and in the name of this Army, which, I dare bee confident to speake itt, hath bin as false and slanderous a report as could bee raised of a man. And that was this; That I should say to the Parliament and deliver itt as the desire of this Armie, and the sence of this Armie, that there should bee a second addresse to the Kinge by way of propositions. I dare bee confident to speake itt, what I deliver’d there I deliver’d as my owne sence, and what I deliver’d as my owne sence I am nott ashamed of. What I deliver’d as your sence, I never deliver’d butt what I had as your sence. [325]

[231]

Col. Rainborow.

For this the Lieutennant Generall was pleas’d to speake of last, [232] itt was moved, that day the propositions were brought in. That itt was carried for making a second addresse to the Kinge, itt was when both the Lieutennant Generall and my selfe were last heere, and where wee broke off heere, and when wee came uppon the Bill itt was told us, That the House had carried itt for a second addresse; and therfore the Lieutenant Generall must needes bee cleare of itt. Butt itt was urged in the House that itt was the sence of the Army that itt should bee soe.

Com̃. Gen. Ireton.

I desire nott to speake of these thinges, butt onely to putt thinges into an orderly way, which would lead to what the occasion is that hath brought these Gentlemen hither that are now call’d in; yett I cannott butt speake a worde to that that was last touch’t uppon.

If I had told any man soe (which I know I did nott) if I did, I did tell him what I thought; and if I thought otherwise of the Army, I protest I should have bin ashamed of the Armie and detested itt; that is, if I had thought the Army had bin of that minde, they would lett those propositions sent from both Kingdomes bee the thinges which should bee [final] whether peace or noe, without any farther offers; and when I doe finde itt, I shall bee asham’d on’t, and detest any dayes condescention with itt. And yett for that which Mr. Sexby tells us hath bin one of the great businesses [cast] uppon the Lieutennant Generall and my self, I doe detest and defie the thought of that thinge, of any indeavour, or designe, or purpose, or desire to sett uppe the Kinge; and I thinke I have demonstrated, and I hope I shall doe still, [that] itt is the interest of the Kingdome that I have suffer’d for. As for the Parliament too, I thinke those that know the beginninges of these principles, that wee [set forth] in our Declarations of late for clearing and vindicating the Liberties of the people, even in relation to Parliament will have reason [to acquit me]. And whoever doe know how wee were led to the declaring of that point [233] as wee have, as [a fundamental] one, will bee able to acquitt mee that I have bin farre from a designe of setting uppe the persons of these men, or of any men whatsoever to bee our Law Makers. Soe likewise for the Kinge; though I am cleare, as from the other, from setting uppe the person of one or other, yett I shall declare itt againe; I doe nott seeke, or would nott seeke, nor will joyne with them that doe seeke the destruction either of Parliament or Kinge. Neither will I consent with those or concurre with them who will nott attempt all the wayes that are possible to preserve both, and to make good use, and the best use that can bee of both for the Kingedome; and I did nott heare any thinge from that Gentleman (Mr. Sexby) that could induce or incline mee to that resolution. To that point I stand cleare as I have exprest. Butt I shall nott speake any more concerning myself.

The Committee [326] mett att my lodginges assoone as they parted from hence; and the first thinge they resolved on hearing there was a meeting of the Agitators [was, that] though itt was thought fitt by the Generall Councill heere they should bee sent for to the Regiment[s], yett itt was thought fitt to lett them know what the Generall Councill had done, and to goe on in a way that might tend to unitie; and [this] being resolved on wee were desired by one of those Gentlemen that were desired to goe, that least they should mistake the matter they went about, itt might bee drawne in writing, and this is itt:

That the Generall Councill, etc. [blank].

This is the substance of what was deliver’d. Mr. Allen, Mr. Lockyer, and Mr. Sexby were sent with itt, and I thinke itt is fitt that the Councill should bee acquainted with the Answer.

Mr. Allen.

As to the Answer itt was short (truly I shall give itt as shorte). [234] Wee gave them the paper, and read itt amongst them, and to my best remembrance they then told us, that they were nott all come together whome itt did concerne, and soe were nott in a capacitie att the present to returne us an Answer; butt that they would take itt into consideration, and would send itt as speedily as might bee. I thinke itt was neare their Sence.

The Answer of the Agitators read. [327]↩

Com̃. Generall.

Wheras itt was appointed by the Councill and wee of the Committee did accordingly desire, that these Gentlemen, being Members of the Army and engaged with the Army, might have come to communicate with the Generall Councill of the Army and those that were appointed by them for a mutuall satisfaction: by this paper they seeme to bee of a fix’t resolution, setting themselves to bee a divided partie or distinct Councill from the Generall Councill of the Army, and [seem to say] that there was nothing to bee done as single persons to declare their dissatisfaction, or the grounds for informing themselves better or us better, butt that they as all the rest should concurre soe as to hold together as a form’d and setled partie distinct and divided from others; and withall seem’d to sett downe these resolutions to [as things] which they expect the compliance of any others, rather then their compliance with others to give satisfaction. Butt itt seemes uppon some thinge that the Lieutennant Generall and some others of that Committee did thinke fitt [to offer] the Gentlemen that brought that paper have bin since induced to descend a little from the heighth, and to send some of them to come as agents particularlie, or Messengers from that Meeting or from that Councill, to heare what wee have to say to there, or to offer somethinge to us relating to the matters in that paper. I beleive there are Gentlemen [328] sent with them that though [235] perhaps the persons of them that are Members of the Army may nott give the passages in itt they may bee better able to observe them; and therefore if you please that they may proceede.

Buffe-Coate.

May itt please your Honour, to give you satisfaccion in that there was such a willingnesse that wee might have a conference, whereuppon I did engage that interest that was in mee that I would procure some to come hither both of the souldiers and of others for assistance; and in order thereunto heere are two souldiers sent from the Agents, and two of our freinds alsoe, and to present this to your considerations, and desire [329] your advice. [we believe that] according to my [330] expectations and your engagement you are resolved every one to purchase our inheritances which have bin lost, and free this Nation from the tyranny that lies uppon us. I question nott butt that itt is all your desires: and for that purpose wee desire to doe nothing butt what wee present to your consideration, and if you conceive itt that itt must bee for us to bee instruments, that wee might shelter our selves like wise men before the Storme comes. Wee desire that all carping uppon words might bee laid aside, and [that you may] fall directly uppon the matter presented to you.

Wee have heere met on purpose [331] according to my Engagement that whatsoever may bee thought to bee necessary for our satisfaction, for the right understanding one of another [may be done] that wee might goe on together. For, though our ends and aimes bee the same, if one thinkes this way, another another way—butt that way which is the best for the subject [is] that they [both] may bee hearkned unto.

[236]

The Answer of the Agitators, the 2 d time read. [332]↩

Buffecoate.

I thinke itt will bee strange that wee that are souldiers cannott have them [for] our selves, if nott for the whole Kingedome; and therfore wee beseech you consider of itt.

Lieut. Generall.

These thinges that you have now offered they are new to us; they are thinges that wee have nott att all (att least in this method and thus circumstantially) had any opportunity to consider of them, because they came to us butt thus as you see; this is the first time wee had a view of them.

Truly this paper does containe in itt very great alterations of the very Governement of the Kingedome, alterations from that Governement that itt hath bin under, I beleive I may almost say since itt was a Nation, I say I thinke I may almost say soe, and [237] what the consequences of such an alteration as this would bee, if there were nothing else to be consider’d, wise men and godly men ought to consider. I say if there were nothing else [to be considered] butt the very weight and nature of the thinges contayn’d in this paper. Therfore, although the pretensions in itt, and the expressions in itt are very plausible, and if wee could leape out of one condition into another, that had soe specious thinges in itt as this hath, I suppose there would nott bee much dispute, though perhaps some of these thinges may bee very well disputed—How doe wee know if whilest wee are disputing these thinges another companie of men shall gather together, and they shall putt out a paper as plausible perhaps as this? I doe nott know why itt might nott bee done by that time you have agreed uppon this, or gott hands to itt, if that bee the way. And not onely another, and another, butt many of this kinde. And if soe, what doe you thinke the consequence of that would bee? Would itt nott bee confusion? Would itt nott bee utter confusion? Would itt nott make England like the Switzerland Country, one Canton of the Switz against another, and one County against another? I aske you whether itt bee nott fitt for every honest man seriouslie to lay that uppon his heart? And if soe, what would that produce butt an absolute desolation—an absolute desolation to the Nation—and wee in the meane time tell the Nation, “It is for your Libertie, ’Tis for your priviledge,” “ ’Tis for your good.” Pray God itt prove soe whatsoever course wee run. Butt truly, I thinke wee are nott onely to consider what the consequences are (if there were nothing else butt this paper), butt wee are to consider the probability of the wayes and meanes to accomplish: that is to say [to consider] whether, [333] according to reason and judgement, the spiritts and temper of the people of this Nation are prepared to receive and to goe on alonge with itt, and [whether] those great difficulties [that] lie in our way [are] in a likelihood to bee either overcome or removed. Truly, to anythinge that’s good, there’s noe doubt on [238] itt, objections may bee made and fram’d; butt lett every honest man consider, whether or noe there bee nott very reall objections [to this] in point of difficulty. I know a man may answer all difficulties with faith, and faith will answer all difficulties really where itt is, but [334] wee are very apt all of us to call that faith, that perhaps may bee butt carnall imagination, and carnall reasonings. Give mee leave to say this, There will bee very great mountaines in the way of this, if this were the thinge in present consideration; and therfore wee ought to consider the consequences, and God hath given us our reason that wee may doe this. Itt is nott enough to propose thinges that are good in the end, butt suppose this modell were an excellent modell, and fitt for England, and the Kingedome to receive, itt is our duty as Christians and men to consider consequences, and to consider the way. [335]

Butt really I shall speake to nothing butt that that, as before the Lord, I am perswaded in my heart tends to uniting of us in one to that that God will manifest to us to bee the thinge that hee would have us prosecute; and hee that meetes nott heere with that heart, and dares nott say hee will stand to that, I thinke hee is a deceivour. I say itt to you againe, and I professe unto you, I shall offer nothing to you butt that I thinke in my heart and conscience tends to the uniting of us, and to the begetting a right understanding amonge us, and therefore this is that I would insist uppon, and have itt clear’d amonge us.

Itt is nott enough for us to insist uppon good thinges; that every one would doe—there is nott 40 of us butt wee could prescribe many thinges exceeding plausible, and hardly anythinge worse then our present condition, take itt with all the troubles that are uppon us. Itt is nott enough for us to propose good thinges, butt itt behoves honest men and Christians that really will approve themselves soe before God and men, to see whether or noe they bee in a condition, [to attempt] whether, taking all thinges into consideration, they may honestly indeavour and attempt that that is fairly [239] and plausibly proposed. For my owne parte I know nothing that wee are to consider first butt that, before wee would come to debate the evill or good of this [paper], or to adde to itt or substract from itt; [336] which I am confident, if your hearts bee upright as ours are—and God will bee judge betweene you and us—if wee should come to any thinge, you doe nott bringe this paper with peremptorinesse of minde, butt to receive amendements to have any thinge taken from itt that may bee made apparent by cleare reason to bee inconvenient or unhonest. This ought to bee our consideration and yours, saving [that] in this you have the advantage of us—you that are the souldiers you have nott—butt you that are nott [soldiers] you reckon your selves att a loose and att a liberty, as men that have noe obligation uppon you. Perhaps wee conceive wee have; and therfore this is that I may say—both to those that come with you, and to my fellow officers and all others that heare mee—that it concernes us as wee would approve our selves [as honest men] before God, and before men that are able to judge of us, if wee doe nott make good engagements, if wee doe nott make good that that the world expects wee should make good. I doe nott speake to determine what that is, butt if I bee nott much mistaken wee have in the time of our danger issued out Declarations; wee have bin requir’d by the Parliament, because our Declarations were generall, to declare particularly what wee meant; and having done that how farre that obliges or nott obliges [us] that is by us to bee consider’d, if wee meane honestly and sincerely and to approve our selves to God as honest men. And therfore having heard this paper read, this remaines to us; that wee againe review what wee have engaged in, and what wee have that lies uppon us. Hee that departs from that that is a reall engagement and a reall tye uppon him, I thinke hee transgresses without faith, for faith will beare uppe men in [240] every honest obligation, and God does expect from men the performance of every honest obligation. Therefore I have noe more to say butt this; wee having received your paper shall amongst our selves consider what to doe; and before wee take this into consideration, itt is fitt for us to consider how farre wee are obliged, and how farre wee are free; and I hope wee shall prove our selves honest men where wee are free to tender any thinge to the good of the publique. And this is that I thought good to offer to you uppon this paper.

Mr. Wildman.

Being yesterday att a Meeting where divers Country-Gentlemen, and souldiers and others were, and amongst the rest the Agents of the five Regiments, and having weigh’d their papers, I must freely confesse I did declare my agreement with them. Uppon that they were pleas’d to declare their sence in most particulars of their proceedinges to mee, and desir’d mee that I would bee their mouth, and in their names to represent their sence unto you; and uppon that ground I shall speake something in answer to that which your Honour last spake.

I shall nott reply any thinge att present till itt come to bee further debated, either concerning the consequences of what is propounded, or [the contents] of this paper; butt I conceive the cheif weight of your Honour’s speech lay in this, that you were first to consider what obligations lay uppon you, and how farre you were engaged, before you could consider what was just in this paper now propounded; adding, that God would protect men in keeping honest promises. To that I must only offer this, that according to the best knowledge [I have] of their apprehensions, they doe apprehend that what ever obligation is past must bee consider’d afterwards, when itt is urged whether itt were honest or just or noe; and if [the obligation [337]] were nott just itt doth nott oblige the persons, if itt bee an oath itt self. Butt if, while there [241] is nott soe cleare a light, any person passes an Engagement, itt is judged by them, (and I soe judge itt), to bee an act of honesty for that man to recede from his former judgement, and to abhorre itt. And therfore I conceive the first thinge is to consider the honesty of what is offer’d, otherwise itt cannott bee consider’d of any obligation that doth prepossesse. By the consideration of the justice of what is offer’d that obligation shall appeare whether itt was just or noe. If itt were nott just, I cannott butt bee confident of the searinges of your consciences. I conceive this to bee their sence; and uppon this account, uppon a more serious review of all Declarations past, they see noe obligations which are just that they contradict by proceeding in this way.

Commissary Gen. Ireton.

Sure this Gentleman hath nott bin acquainted with our Engagements, for hee that will cry out of breach of Engagement in slight and triviall thinges, and thinges necessitated to, that is soe tender of an Engagement as to frame or concurre with this Booke [338] in their insisting uppon every punctilio of Engagement, I can hardly thinke that man [339] can bee of that principle that noe Engagement is binding further then that hee thinkes itt just or noe. For itt hintes that, if hee that makes an Engagement (bee itt what itt will bee) have further light that this engagement was nott good or honest, then hee is free from itt. Truly if the sence were putt thus, that a man that findes hee hath entred into an engagement and thinkes that itt was nott a just Engagement, I confesse some thinge might bee said that [such] a man might declare himself for his parte to suffer some penalty uppon their persons, or uppon their partie. [242] The question is, whether itt bee an Engagement to another partie. Now if a man venture into an Engagement from him [self] to another, and find [340] that Engagement [not] just and honest, hee must apply himself to the other partie, and say “I cannott actively performe itt, I will make you amends as neere as I can.” Uppon the same ground men are nott obliged to [be obedient to] any aucthoritie that is sett uppe, though itt were this aucthority that is proposed heere, I am nott engaged to bee soe actively to that aucthority. Yett if I have engag’d that they shall binde mee by Law, though afterwards, I finde that they doe require mee to a thinge that is nott just or honest, I am bound soe farre to my Engagement that I must submitt and suffer, though I cannott act and doe that which their Lawes doe impose upon mee. If that caution were putt in where a performance of an Engagement might bee expected from another, and hee could nott doe itt because hee thought itt was nott honest to bee performed; if such a thinge were putt into the case, itt is possible there might bee some reason for itt. Butt to take itt as itt is deliver’d in generall, whatever Engagement wee have entred into, though itt bee a promise of somethinge to another partie, wherin that other partie is concerned, wherin hee hath a benefitt, if wee make itt good, wherin hee hath a prejudice if wee make itt nott good [that we are free to break it if it be not just]: this is a principle that will take away all Commonwealth[s], and will take away the fruite of this Engagement if itt were entred into; and men of this principle would thinke themselves as little as may bee [obliged by any law] if in their apprehensions itt bee nott a good Law. I thinke they would thinke themselves as little obliged to thinke of standing to that aucthority [that is proposed in this paper].

Truly Sir I have little to say att the present to that matter of the paper that is tendred to us. I confesse there are plausible thinges in itt, and there are thinges really good in itt, and there are those thinges that I doe with my heart desire, and there are [243] those thinges for the most parte of itt [that] I shall bee soe free as to say, if these Gentlemen, and other Gentlemen that will joyne with them can obtaine, I would nott oppose, I should rejoice to see obtayn’d. There are those thinges in itt, divers [of them]; and, if wee were as hath bin urged now, free; if wee were first free from consideration of all the dangers and miseries that wee may bringe uppon this people, [the danger] that when wee goe to cry out for the libertie of itt wee may nott leave a being [in it], free from all [those] Engagements that doe lie uppon us, and that were honest when they were entred into, I should concurre with this paper further then as the case doth stand I can. Butt truly I doe account wee are under Engagements; and I suppose that whatsoever this Gentleman that spoke last doth seeme to deliver to us, holding himself absolved from all Engagements, if hee thinkes itt, yett those men that came with him (that are in the case of the Armie,) [341] hold themselves more obliged; and therfore that they will nott perswade us to lay aside all our former Engagements and Declarations, if there bee any thinge in them, and to concurre in this, if there bee any thinge in itt that is contrary to those Engagements which they call uppon us to confirme. Therfore I doe wish that wee may have a consideration of our former Engagements, of thinges which are the Engagements of the Army generallie. Those wee are to take notice of, and sure wee are nott to recede from them till wee are convinct of them that they are unjust. And when wee are convinc’t of them that they are unjust, truly yett I must nott fully concurre with that Gentleman’s principle, that presently wee are, as hee sayes, absolv’d from them, that wee are nott bound to them, or wee are nott bound to make them good. Yett I should thinke att least, if the breach of that Engagement bee to the prejudice of another whome wee have perswaded to beleive by our Declaring such thinges [so] that wee made them and led them to a confidence of itt, to a dependance uppon itt, to [244] a disadvantage to themselves or the loosing of advantages to them, though wee were convinc’t they were unjust, and satisfied in this Gentleman’s principle, and free, and disengag’d from them, yett wee who made that engagement should nott make itt our act to breake itt. Though wee were convinc’t that wee are nott bound to performe itt, yett wee should nott make itt our act to breake [it]. And soe uppon the whole matter I speake this to inforce. As uppon the particulars of this Agreement; whether they have that goodnesse that they hold forth in shew? or whether are nott some defects in them which are nott seene? that if wee should rest in this Agreement without somethinge more [whether] they would nott deceive us? and whether there bee nott some considerations that would tend to union? And withall [i wish] that wee who are the Armie and are engag’d with publique Declarations may consider how farre those publique Declarations, which wee then thought to bee just, doe oblige, that wee may either resolve to make them good if wee can in honest wayes, or att least nott make itt our worke to breake them. And for this purpose I wish—unlesse the Councill please to meete from time to time, from day to day and to consider itt themselves—to goe over our papers and declarations and take the heads of them, I wish there may bee some specially appointed for itt; and I shall bee very glad if itt may bee soe that I my self may bee none of them.

Col. Rainborow.

I shall crave your pardon if I may speake something freelie, and I thinke itt will bee the last time I shall speake heere, and from such a way that I never look’t for. The consideration that I had in this Army and amongst honest men—nott that itt is an addition of honour and profitt to mee butt rather a detriment in both—is the reason that I speake somethinge by way of apologie. I saw this paper first by chance and had noe resolution to have bin att this Councill nor any other since I tooke this imployment uppon [245] mee, butt to doe my duty. [342] I mett with a Letter (which truly was soe strange to mee that I have bin a little troubled, and truly I have soe many sparkes of honour and honesty in mee) to lett mee know that my Regiment should bee imediately disposed from mee. I hope that none in the Army will say butt that I have perform’d my duty, and that with some successe, as well as others. I am loath to leave the Army with whome I will live and die, insomuch that rather then I will loose this Regiment of mine the Parliament shall exclude mee the House, [or] imprison mee; for truly while I am [employed] abroad I will nott bee undone att home. This was itt that call’d mee hither, and nott any thinge of this paper. Butt now I shall speake somethinge of itt.

I shall speake my minde; that whoever hee bee that hath done this hee hath done it with much respect to the Good of his Country. Itt is said there are many plausible thinges in itt. Truly, many thinges have engaged mee, which, if I had nott knowne they should have bin nothing butt Good, I would nott have engag’d in. Itt hath bin said, that if a man bee Engag’d hee must performe his Engagements. I am wholly confident that every honest man is bound in duty to God and his Conscience, lett him bee engag’d in what hee will, to decline itt when hee is engag’d and clearly convinc’t to discharge his duty to God as ever hee was for itt; [246] and that I shall make good out of the Scripture, and cleare itt by that if that bee any thinge. There are two objections are made against itt.

The one is Division. Truly I thinke wee are utterly undone if wee devide, butt I hope that honest things have carried us on thus longe, and will keepe us together, and I hope that wee shall nott devide. Another thinge is Difficulties. Oh unhappy men are wee that ever began this warre; if ever wee [had] look’t uppon difficulties I doe nott know that ever wee should have look’t an enemy in the face. Truly I thinke the Parliament were very indiscreete to contest with the Kinge if they did nott consider first that they should goe through difficulties; and I thinke there was noe man that entred into this warre that did nott engage [to go through difficulties]. And I shall humbly offer unto you—itt may bee the last time I shall offer—itt may bee soe, butt I shall discharge my conscience in itt—itt is this; that truly I thinke that lett the difficulties bee round about you, have you death before you, the sea on each side of you and behinde you, are you convinc’t that the thinge is just I thinke you are bound in conscience to carry itt on; and I thinke att the last day itt can never bee answer’d to God that you did nott doe itt. For I thinke itt is a poore service to God and the Kingedome to take their pay and to decline their worke. I heare itt said, “Itt’s a huge alteration, itt’s a bringing in of New Lawes,” and that this Kingedome hath bin under this Governement ever since itt was a Kingdome. If writinges bee true there hath bin many scufflinges betweene the honest men of England and those that have tyranniz’d over them; and iff itt bee [true what i have] read, there is none of those just and equitable lawes that the people of England are borne to butt that they are intrenchment altogether. [343] Butt if they were those which the people have bin alwayes under, if the people finde that they are [not] suitable to freemen as they are, I know noe reason [247] should deterre mee, either in what I must answer before God or the world, from indeavouring by all meanes to gaine any thinge that might bee of more advantage to them then the Government under which they live. I doe nott presse that you should goe on with this thinge, for I thinke that every man that would speake to itt will bee lesse able till hee hath some time to consider itt. I doe make itt my Motion, that two or three dayes time may bee sett for every man to consider, and all that is to bee consider’d is the justnesse of the thinge—and if that bee consider’d then all thinges are—that there may bee nothing to deterre us from itt, butt that wee may doe that which is just to the people.

Lieut. Generall.

Truly I am very glad, that this Gentleman that spoke last is heere, and nott sorry for the occasion that brought him hither; because itt argues wee shall enjoy his company longer then I thought wee should have done.

Col. Rainborow.

If I should nott bee kick’t out.

Lieut. Generall.

And truly then I thinke itt shall nott bee longe enough. Butt truly I doe nott know what the meaning of that expression is, nor what the meaning of any hatefull worde is heere. For wee are all heere with the same integrity to the publique; and perhaps wee have all of us done our parts nott affrighted with difficulties, one as well as another; and I hope have all purposes henceforward, through the Grace of God, nott resolving in our owne strength, to doe soe still. And therefore truly I thinke all the consideration is, That amongst us wee are almost all souldiers; all considerations [of not fearing difficulties] or wordes of that kinde doe wonderfully please us, all words of courage animate us to carry on our businesse, to doe God’s businesse, [and] that which is the will of [248] God. I say itt againe, I doe nott thinke that any man heere wants courage to doe that which becomes an honest man and an Englishman to doe. Butt wee speake as men that desire to have the feare of God before our eyes, and men that may nott resolve to doe that which wee doe in the power of a fleshly strength, butt to lay this as the foundation of all our actions, to doe that which is the will of God. And if any man have a false deceit—on the one hand, deceitfulnesse, that which hee doth nott intend, or a perswasion on the other hand, I thinke hee will nott prosper.

Butt to that which was mov’d by Col. Rainborow, of the objections of difficulty and danger [and] of the consequences, they are nott proposed to any other end, butt [as] thinges fitting consideration, nott forged to deterre from the consideration of the businesse. In the consideration of the thinge that is new to us, and of every thinge that shall bee new that is of such importance as this is, I thinke that hee that wishes the most serious advice to bee taken of such a change as this is,—soe evident and cleare [a change]—who ever offers that there may bee most serious consideration, I thinke hee does nott speake impertinently. And truly itt was offer’d to noe other end then what I speake. I shall say noe more to that.

Butt to the other, concerning Engagements and breaking of them. I doe nott thinke that itt was att all offer’d by any body, that though an Engagement were never soe unrighteous itt ought to bee kept. Noe man offer’d a syllable or tittle [to that purpose]. For certainly itt’s an act of duty to breake an unrighteous Engagement; hee that keepes itt does a double sin, in that hee made an unrighteous Engagement, and [in] that he goes about to keepe itt. Butt this was onely offer’d; and I know nott what can bee more fit, that before wee can consider of this [paper] wee labour to know where wee are, and where wee stand. Perhaps wee are uppon Engagements that wee cannott with honesty breake, Butt lett mee tell you this, that hee that speakes to you of Engagements heere, is as free from Engagements to the Kinge as [249] any man in all the world; and I know that [344] if itt were otherwise I believe my future actions would provoke some to declare itt. Butt I thanke God I stand uppon the bottome of my owne innocence in this particular; through the Grace of God I feare nott the face of any man, I doe nott. I say wee are to consider what Engagements wee have made, and if our Engagements have bin unrighteous why should wee nott make itt our indeavours to breake them. Yett if unrighteous Engagements [345] itt is nott a present breach of them unlesse there bee a consideration of circumstances. Circumstances may bee such as I may nott now breake an unrighteous Engagement, or else I may doe that which I did scandalously, if the thinge bee good. [346] If that bee true concerning the breaking of an unrighteous Engagement itt is much more verified concerning Engagements disputable whether they bee righteous or unrighteous. If soe, I am sure itt is fitt wee should dispute [them], and if, when wee have disputed them, wee see the goodnesse of God inlightening us to see our liberties, I thinke wee are to doe what wee can to give satisfaction to men. Butt if itt were soe, as wee made an Engagement in judgement and knowledge, soe wee goe off from itt in judgement and knowledge. Butt there may be just Engagements uppon us such as perhaps itt will bee our duty to keepe; and if soe itt is fitt wee should consider, and all that I said [was] that wee should consider our Engagements, and there is nothing else offer’d, and therefore what neede anybody bee angry or offended. Perhaps wee have made such Engagements as may in the matter of them nott binde us, in some circumstances they may. Our Engagements are publique Engagements. They are to the Kingedome, and to every one in the Kingdome that could looke uppon what wee did publiquely declare, could read or heare itt read. They are to the [250] Parliament, and itt is a very fitting thinge that wee doe seriously consider of the thinges. And shortly this is that I shall offer: that because the Kingedome is in the danger itt is in, because the Kingdome is in that condition itt is in, and time may bee ill spent in debates, and itt is necessary for thinges to bee putt to an issue, if ever itt was necessary in the world itt is now, I should desire this may bee done.

That this Generall Councill may bee appointed [to meet] against a very short time, two dayes, Thursday, if you would, against Saturday, or att furthest against Munday: that there might bee a Committee out of this Councill appointed to debate and consider with those two Gentlemen, and with any others that are nott of the Army that they shall bringe, and with the Agitators of those five Regiments: that soe there may bee a liberall and free debate had amongst us, that wee may understand really as before God the bottome of our desires, and that wee may seeke God together, and see if God will give us an uniting spiritt. Give mee leave to tell itt you againe, I am confident there sitts nott a man in this place that cannott soe freely act with you, but if hee sees that God hath shutt uppe his way that hee cannott doe any service hee will bee glad to withdraw himself, and wish you all prosperity in that way as may bee good for the Kingedome. [347] And if this heart bee in us, as is knowne to God that searches our hearts and tryeth the reines, God will discover whether our hearts bee nott cleare in this businesse. Therefore I shall move that wee may have a Committee amongst our selves [to consider] of the Engagements, and this Committee to dispute thinges with others, and a short day [to be appointed] for the Generall Councill. I doubt nott butt if in sincerity wee are willing to submitt to that light that God shall cast in amonge us God will unite us, and make us of one heart and one minde. Doe the plausiblest thinges you can doe, doe that which hath the most appearance of reason in itt that tends to change, att this conjuncture of time you will finde difficulties. Butt if God satisfie our spiritts this will bee a ground of confidence to every [251] good man, and hee that goes uppon other grounds hee shall fall like a beast. I shall desire this, that you or any other of the Agitators or Gentlemen that can bee heere will bee heere, that wee may have free discourses amongst our selves of thinges, and you will bee able to satisfie each other. And really, rather then I would have this Kingedome breake in pieces before some company of men bee united together to a settlement, I will withdraw my self from the Army tomorrow, and lay downe my Commission; I will perish before I hinder itt. [348]

Bedfordshire Man.

May itt please your Honour,

I was desired by some of the Agents to accompanie this paper, manifesting my approbation of itt after I had heard itt read severall times, and they desir’d that itt might bee offer’d to this Councill, for the concurrence of the Councill if itt might bee. I finde that the Engagements of the Army are att present the thinges which is insisted to bee consider’d. I confesse my ignorance in those Engagements, butt I apprehend, att least I hope, that those Engagements have given away nothing from the people that is the people’s Right. Itt may bee they have promised the King his Right, or any other persons their Right, butt noe more. If they have promised more then their Right to any person or persons, and have given away any thinge from the people that is their Right, then I conceive they are unjust. And if they are unjust [they should be broken], though I confesse for my owne parte I am very tender of breaking an Engagement when itt concernes a particular person—I thinke that a particular person ought rather to sett downe and loose then to breake an Engagement—butt if any man have given away any thinge from another whose Right itt was to one or more whose Right itt was nott, I conceive these men may [break that engagement]—at least many of them thinke themselves [252] bound nott onely to breake this Engagement, butt to place [349] to give every one his due. I conceive that for the substance of the paper itt is the peoples due; and for the change of the Governement which is soe dangerous, I apprehend that there may bee many dangers in itt, and truly I apprehend there may bee more dangers without itt. For I conceive if you keepe the Governement as itt is and bringe in the Kinge, there may bee more dangers then in changing the Governement. Butt however, because from those thinges that I heard of the Agents they conceive that this conjuncture of time may almost destroy them, they have taken uppon them a libertie of acting to higher thinges, as they hope, for the freedome of the Nation, then yett this Generall Councill have acted to. And therefore as their sences I must make this motion; that all those that uppon a due consideration of the thinge doe finde itt to bee just and honest, and doe finde that if they have engaged any thinge to the contrary of this itt is unjust and giving away the people’s Rights, I desire that they and all others may have a free libertie of acting to any thinge in this nature, or any other nature, that may bee for the peoples good, by petitioning or otherwise; wherby the fundamentalls for a well-ordered Governement for the people’s Rights may bee established. And I shall desire that those that conceive themselves bound uppe would desist, and satisfie themselves in that, and bee noe hinderances to hinder the people in a more perfect way then hath bin [yet] indeavour’d.

Capt. Awdeley.

I suppose you have nott thought fitt, that there should bee a dispute concerning thinges att this time. I desire that other thinges may bee taken into consideration, delayes and debates. Delayes have undone us, and itt must bee a great expedition that must further us, and therfore I desire that there may bee a Committee appointed.

[253]

Lieut. Col. Goffe.

I shall butt humbly take the boldnesse to put you in minde of one thinge which you moved enow. [350] The Motion is, that there might bee a seeking of God in the thinges that now lie before us.

I shall humbly desire, that that Motion may nott die. Itt may bee there are or may bee some particular opinions amonge us concerning the use of ordinances and of publique seeking of God. Noe doubt formes have bin rested uppon too much; butt yett since there are soe many of us that have had soe many and soe large experiences of an extraordinarie manifestation of God’s presence, when wee have bin in such extraordinarie wayes mett together, I shall desire that those who are that way [inclined] will take the present opportunity to doe itt. For certainly those thinges that are now presented, as they are, are well accepted by most of us; and though I am nott prepared to say any thinge either consenting or dissenting to the paper, as nott thinking itt wisedome to answer a matter before I have consider’d, yett when I doe consider how much ground there is to conceive there hath bin a withdrawing of the presence of God from us that have mett in this place—I doe nott say a totall withdrawing; I hope God is with us and amongst us. Itt hath bin our trouble night and day that God hath nott bin with us as formerly, as many within us soe without us [have told us], men that were sent from God in an extraordinarie manner to us. I meane [that though] the Ministers may take too much uppon them, yett there have bin those that have preached to us in this place, [in] [351] severall places, wee know very well that they spake to our hearts and consciences, and told us of our wandringes from God, and told us in the name of the Lord, that God would bee with us noe longer then wee were with him. Wee have in some thinges wandred from God, and as wee have heard [254] this from them in this place, soe have wee had itt very frequently prest uppon our spiritts [elsewhere], prest uppon us in the Citty and the Country. I speake this to this end, that our hearts may bee deeply and throughly affected with this matter. For if God bee departed from us hee is some where else. Iff wee have nott the will of God in these Councills God may bee found amonge some other Councills. Therfore I say, lett us shew the spiritt of Christians, and lett us nott bee ashamed to declare to all the world, that our Councills, and our wisedome, and our wayes they are nott altogether such as the world hath walked in; butt that wee have had a dependancie uppon God, and that our desires are to follow God (though never soe much to our disadvantage in the world) if God may have the glory by itt. And I pray lett us consider this: God does seeme evidently to bee throwing downe the glory of all flesh; the greatest powers in the Kingedome have bin shaken. God hath throwne downe the glory of the Kinge and that partie; hee hath throwne downe a partie in the Citty; I doe nott say, that God will throw us downe—I hope better thinges—butt hee will have the glory; lett us nott stand uppon our glory and reputation in the world. If wee have done some thinges through ignorance, or feare, or unbeleif, in the day of our straights, and could nott give God that glory by beleiving as wee ought to have done, I hope God hath a way for to humble us for that, and to keepe us as instruments in his hand still. There are two wayes that God doth take uppon those that walke obstinately against him; if they bee obstinate and continue obstinate hee breakes them in pieces with a rod of iron; if they bee his people and wander from him hee takes that glory from them, and takes itt to himself. I speake itt I hope from a divine impression. If wee would continue to bee instruments in his hand, lett us seriously sett our selves before the Lord, and seeke to him and waite uppon him for conviction of spiritts. Itt is nott enough for us to say, “if wee have offended wee will leave the world, wee will goe and confesse to the Lord what wee have done amisse, butt wee will doe noe more soe.’ [255] Aaron went uppe to Hur and died, and Moses was favour’d to see the land of Canaan, hee did nott voluntarily lay himself aside. I hope our strayings from God are nott soe great, butt that a conversion and true humiliation may recover us againe; and I desire that wee may bee serious in this, and not despise any other instruments that God will use. God will have his worke done; itt may bee wee thinke wee are the onely instruments that God hath in his hands. I shall onely adde these two thinges. First, that wee bee warie how wee lett forth any thinge against his people, and that which is for the whole Kingedome and Nation. I would move, that wee may nott lett our spiritts act too freely against them till wee have throughly weighed the matter, and considered our own wayes too. The second is to draw us uppe to a serious consideration of the weightiness of the worke that lies before us, and seriously to sett our selves to seeke the Lord; and I wish itt might bee consider’d of a way and manner that itt should be conveniently done, and I thinke to morrow will bee the [best] day.

Lieut Generall.

I know nott what Lieut. Col. Goffe meanes for to morrow for the time of seeking God. I thinke itt will bee requisite that wee doe itt speedily, and doe itt the first thinge, and that wee doe itt as unitedly as wee can, as many of us as well may meete together. For my parte I shall lay aside all businesse for this businesse, either to convince or bee convinc’t as God shall please. I thinke itt would bee good that to morrow morning may bee spent in prayer, and the afternoone might bee the time of our businesse. I doe nott know that these Gentlemen doe assent to itt that to morrow in the afternoone might bee the time.

Lieut. Col. Goffe.

I thinke wee have a great deale of businesse to doe, and wee have bin doing of itt these ten weekes. Itt is an ordinance that [256] God hath blest to this end. I say goe about what you will, for my parte I shall nott thinke any thinge can prosper, unlesse God bee first sought.

If that bee approved of, that to morrow shall bee a time of seeking the Lord, and that the afternoone shall bee the time of businesse, if that doth agree with your opinion and the generall sence, lett that bee first order’d.

Com̃. Gen. Ireton.

That which Lieut. Col. Goffe offer’d hath [made] a very great impression uppon mee; and indeed I must acknowledge to God through him, that, as hee hath severall times spoke in this place, and elsewhere to this purpose, hee hath never spoke butt hee hath touched my heart; and that especially in the point that hee hintes. That one thinge is, that in the time of our straights and difficulties, I thinke wee none of us—I feare wee none of us—I am sure I have nott—walked soe closely with God, and kept soe close with him, [as] to trust wholly uppon him, as nott to bee led too much with considerations of danger and difficulty, and from that consideration to waive some thinges, and perhaps to doe some thinges, that otherwise I should nott have thought fitt to have done. Every one hath a spiritt within him—especially [he] who has that communion indeed with that spirit that is the only searcher of hearts—that can best search out and discover to him the errours of his owne wayes, and of the workinges of his owne heart. And though I thinke that publique actinges, publique departings from God are the fruites of unbeleif and distrust, and nott honouring God by sanctifying him in our wayes; they doe more publiquely engage God to vindicate his honour by a departing from them that doe soe, and if there bee any such thinge in the Army that is to bee look’t uppon with a publique eye in relation to the Army. [352] I thinke the maine thinge is for every one [257] to waite uppon God, for the errours, deceits, and weaknesses of his owne heart, and I pray God to bee present with us in that. Butt withall I would nott have that seasonable and good Motion that hath come from Lieut. Col. Goffe to bee neglected, of a publique seeking of God, and seeking to God, as for other thinges soe especially for the discovery of any publique deserting of God, or dishonouring of him, or declining from him, that does lie as the fault and blemish uppon the Army. Therfore I wish his Motion may bee pursued, that the thinge may bee done, and for point of time as was moved by him. Onely this to the way; I confesse I thinke the best [way] is this, that itt may bee only taken notice of as a thinge by the agreement of this Councill resolv’d on, that tomorrow in the morning, the forenoone wee doe sett aparte, wee doe give uppe from other businesse, for every man to give himself uppe that way, either in private by himself, though I cannott say not in public. For the publique Meeting att the Church, itt were nott amisse that itt may bee thus taken notice of as a time given from other imployments for that purpose, and every one as God shall incline their hearts, some in one place, and some another, to imploy themselves that way.

Agreed for the Meeting for Prayer to bee att Mr. Chamberlaine’s

Lieut. Gen.

That they should nott meete as two contrary parties, butt as some desirous to satisfie or convince each other.

Mr. Petty.

For my owne parte, I have done as to this businesse what was desired by the Agents that sent mee hither. As for any further [258] Meeting to morrow or any other time I cannott meete uppon the same ground, to meete as for their sence, [but only] to give my owne reason why I doe assent to itt.

Com̃. Ireton.

I should bee sorry, that they should bee soe suddaine to stand uppon themselves.

Mr. Petty.

To procure three, four, or five more or lesse to meete, for my owne parte I am utterly unconcern’d in the businesse.

Buffe-Coate.

I have heere att this day answer’d the expectations, which I engaged to your Honours; which was, that if wee would give a Meeting you should take that as a symptome, or a remarkeable testimonie of our fidelitie. I have discharged that trust reposed in mee. I could nott engage for them. I shall goe on still in that method. I shall engage my deepest interest for any reasonable desires to engage them to come to this.

Lieut. Generall.

I hope wee know God better then to make appearances of Religious Meetings as covers for designes for insinuation amongst you. I desire that God that hath given us some sinceritie will owne us according to his owne goodnesse, and that sincerity that hee hath given us. I dare bee confident to speake itt, that [design] that hath bin amongst us hitherto is to seeke the guidances of God, and to recover that presence of God that seemes to withdraw from us; and our end is to accomplish that worke which may bee for the good of the Kingedome. It seems to us in this as much as anything we are not of a minde, and for our parts wee doe nott desire or offer you to bee with us in our seeking of God further then your owne satisfaccions lead you, butt onely [that] against to-morrow in the afternoone (which will bee design’d for the consideration [259] of these businesses with you) you will doe what you may to have soe many as you shall thinke fitt to see what God will direct you to say to us. Perhaps God may unite us and carry us both one way, that whilest wee are going one way, and you another, wee bee nott both destroyed. This requires spiritt. Itt may bee too soone to say, itt is my present apprehension; I had rather wee should devolve our strength to you then that the Kingedome for our division should suffer losse. [353] For that’s in all our hearts, to professe above any thinge that’s worldlie, the publique good of the people; and if that bee in our hearts truly, and nakedlie, I am confident itt is a principall that will stand. And therefore I doe desire you, that against to morrow in the afternoone, if you judge itt meete, you will come to us to the Quartermaster Generall’s Quarters, and there you will finde us [at prayer], if you will come timely to joyne with us; at your libertie, if afterwards [you wish] to speake with us. [354]

Mr Wildman.

I desire to returne a little to the businesse in hand that was the occasion of these other motions. I could nott butt take some notice of some thinge that did reflect uppon the Agents of the five Regiments, in which I could nott butt give a little satisfaction to them; and I shall desire to prosecute a motion or two that hath bin already made. I observ’d that itt was said, that these gentlemen doe insist upon Engagements in “The Case of the Army,” and therefore it was said to bee contrary to the principles of the Agents, that an Engagement which was unjust should lawfully bee broken. [355] I shall onely observe this; that though an unjust Engagement when [260] itt appeares unjust may bee broken, yett when two parties engage [each that] the other partie may have satisfaccion, yett because they are mutually engaged each to other one partie that apprehends they are broken [is justified] to complaine of them; and soe itt may bee their case, with which I confesse I made my concurrence. The other is a principle much spreading and much to my trouble, and that is this: that when persons once bee engaged, though the Engagement appeare to bee unjust, yett the person must sett downe and suffer under itt; and that therefore, in case a Parliament, as a true Parliament, doth anythinge unjustly, if wee bee engaged to submitt to the Lawes that they shall make, if they make an unjust law, though they make an unrighteous law, yett wee must sweare obedience.

I confesse to mee this principle is very dangerous, and I speake itt the rather because I see itt spreading abroad in the Army againe. Wheras itt is contrary to what the Army first declar’d: that they stood uppon such principles of right and freedome, and the lawes of nature and nations, wherby men were to preserve themselves though the persons to whome aucthority belong’d should faile in itt, and urged the example of the Scotts, and [that] the Generall that would destroy the Army they might hold his hands; and therfore if any thinge tends to the destruction of a people, because the thinge is absolutely unjust and tends to their destruction, [they may preserve themselves]. [356] I could nott butt speake a worde to that. The motion that I should make uppon that account is this.

[261]

That wheras there must bee a Meeting I could nott finde [but] that they were desirous to give all satisfaccion, and they desire nothing but the union of the Army. Thus farre itt is their sence. That the necessity of the Kingdome for present actinges is such that two or three dayes may loose the Kingdome. I desire in the sight of God to speake plainly: I meane there may bee an agreement betweene the Kinge [and the parliament] by propositions, with a power to hinder the making of any lawes that are good, and the tendring of any good [lawes]. And therfore, because none of the people’s greivances are redrest, they doe apprehend that thus a few dayes may bee the losse of the Kingedome. I know it is their sence. That they desire to bee excused that itt might nott bee thought any arrogancie in them, butt they are clearlie satisfied, that the way they proceede in is just, and desire to bee excus’d if they goe on in itt; and yett notwithstanding will give all satisfaccion. And wheras itt is desir’d that Engagements may bee consider’d, I shall desire that onely the justice of the thinge that is proposed may bee consider’d. Whether the chief thinge in the Agreement, the intent of itt, bee nott this, to secure the Rights of the people in their Parliaments, which was declar’d by this Army in the Declaration of the 14th of June to bee absolutely insisted on? I shall make that motion to bee the thinge consider’d: whether the thinge bee just or the people’s due, and then there can bee noe Engagement to binde from itt.

[262]

Com̃. Gen. Ireton.

Truly Sir, by what Lieut. Col. Goffe moved I confesse I was soe taken off from all [other] thoughts in this businesse that I did nott thinke of speaking any thinge more. Butt what this Gentleman hath last said hath renewed the occasion, and indeed if I did thinke [357] all that hee hath deliver’d bee truth and innocence—nay, if I did nott thinke that it hath venome and poyson in itt—I would nott speake itt.

First, I cannott butt speake somethinge unto the two particulars that hee holds forth as dangerous thinges,—indeed hee hath cleerlie yoak’t them together, when before I was sensible of those principles and how farre they would run together—that is that principle of nott being obliged, by nott regarding what Engagements men have entred into, if in their future apprehensions the thinges they engaged to are unjust; and that principle on the other hand of nott submitting passively for peace sake to that authority wee have engaged to. For hee does hold forth his opinion in those two points to cleare their way; and I must crave leave on my parte to declare [that] my opinion of that Distinction doth lie on the other way. I am farre from holding, that if a man have engag’d himself to a thinge that is nott just—to a thinge that is evill, that is sin if hee doe itt—that that man is still bound to performe what hee hath promised; I am farre from apprehending that. Butt when wee talke of just, itt is nott soe much of what is sinfull before God, which depends uppon many circumstances of indignation to that man and the like, butt itt intends of that which is just according to the foundation of justice betweene man and man. And for my parte I account that the great foundation of justice betweene man and man, and that without which I know nothing of justice betwixt man and man—in particular matters I meane, nothing in particular thinges that can come under humane Engagement one way or other—there is noe other foundation of right I know of, right to one thinge from another man, noe foundation of [263] that justice or that righteousnesse, butt this generall justice, and this generall ground of righteousnesse, that wee should keepe covenant one with another. Covenants freely made, freely entred into, must bee kept one with another. Take away that I doe nott know what ground there is of any thinge you can call any man’s right. I would very faine know what you Gentlemen or any other doe account the right you have to any thinge in England, any thinge of estate, land, or goods that you have, what ground, what right you have to itt? What right hath any man to any thinge if you lay nott that principle, that wee are to keepe covenant? If you will resort onely to the law of Nature, by the law of Nature you have noe more right to this land or any thinge else then I have. I have as much right to take hold of any thinge that is for my sustenance, [to] take hold of any thinge that I have a desire to for my satisfaction as you. Butt heere comes the foundation of all right that I understand to be betwixt men, as to the enjoying of one thinge or nott enjoying of itt; wee are under a contract, wee are under an agreement, and that agreement is what a man has for matter of land that a man hath received by a traduction from his ancestors, which according to the law does fall uppon him to bee his right. [the agreement is] that that hee shall enjoy, hee shall have the property of, the use of, the disposing of, with submission to that generall aucthoritie which is agreed uppon amongst us for the preserving of peace, and for the supporting of this law. This I take to bee [the foundation of all right] for matter of land. For matter of goods, that which does fence mee from that [right] which another man may claime by the law of nature of taking my goods, that which makes itt mine really and civillie is the law. That which makes itt unlawfull originally and radically is onely this: because that man is in covenant with mee to live together in peace one with another, and nott to meddle with that which another is posses’t of, butt that each of us should enjoy, and make use of, and dispose of, that which by the course of law is in his possession, and [another] shall nott by violence take itt away from him. This is [264] the foundation of all the right any man has to any thinge butt to his owne person. This is the generall thinge: that wee must keepe covenant one with another when wee have contracted one with another. And if any difference arise among us itt shall bee thus and thus: that I shall nott goe with violence to prejudice another, butt with submission to this way. And therefore when I heare men speake of laying aside all Engagements to [consider only] that wild or vast notion of what in every man’s conception is just or unjust, I am afraid and doe tremble att the boundlesse and endlesse consequences of itt. [358] What you apply this paper to. You say, “If these thinges in this paper, in this Engagement bee just, then,” say you, “never talke of any Engagement, for if any thinge in that Engagement bee against this, your Engagement was unlawfull; consider singly this paper, whether itt bee just.” In what sence doe you thinke this is just? There is a great deale of equivocation [as to] what is just and unjust.

Mr. Wildman.

I suppose you take away the substance of the question. Our [359] [sense] was, that an unjust Engagement is rather to be broken then kept. The Agents thinke that to delay is to dispose their Enemy into such a capacitie as hee may destroy them. I make a question whether any Engagement can bee to an unjust thinge. [if] a man may promise to doe that which is never soe much unjust, a man may promise to breake all Engagements and duties. Butt [i say] this, wee must lay aside the consideration of Engagements, soe as nott to take in that as one ground of what is just or unjust amongst men in this case. I doe apply this to the case in hand: that itt might bee consider’d whether itt bee unjust to bringe in the Kinge in such a way as hee may bee in a capacity to destroy the people. This paper may bee applyed to itt.

[265]

Com̃. Generall.

You come to itt more particularly then that paper leads. There is a great deale of equivocation in the point of justice, and that I am bound to declare.

Capt. Awdeley.

Mr. Wildman sayes if wee stay butt three dayes before you satisfie one another, and if wee tarry longe the kinge will come and say who will be hang’d first.

Com̃ Gen.

Sir, I was saying this; wee shall much deceive our selves, and bee apt to deceive others if wee doe nott consider that there is two parts of justice. There may bee a thinge just that is negatively [so], itt is nott unjust, nott unlawfull—that which is nott unlawfull, that’s just to mee to doe if I bee free. Againe there is another sence of just when wee account such a thinge to bee a duty,—nott onely a thinge lawfull “we [360] may doe itt,” but itt’s a duty, “you ought to doe itt,”—and there is a great deale of mistake if you confound these two. If I engage my self to a thinge that was in this sence just, that’s a thinge lawfull for mee to doe supposing mee free, then I account my Engagement stands good to this. On the other hand, if I engage my self against a thinge which was a duty for mee to doe, which I was bound to doe; or if I engag’d myself to a thinge which was nott lawfull for mee to doe, which I was bound nott to doe, in this sence I doe account this [engagement] unjust. If I doe engage my self to what was unlawfull for mee to engage to, I thinke I am nott then to make good activelie this Engagement. Butt though this bee true, yett the generall end and equitie of Engagements I must regard, and that is the preserving right betwixt men, the nott doing of wronge or hurt to men, one to another. And therfore if [by] that which I engage to, though the thinge bee unlawfull for mee to doe, another man bee prejudict in case I [266] did not perform it—though itt bee a thinge which was [361] unlawfull for mee to doe, yett [if] I did freelie [engage to do it] and I did [engage] uppon a consideration to mee, and that man did beleive mee, and hee suffer’d a prejudice by beleiving—though I bee nott bound by my Engagement to performe itt, [362] yett I am [bound] to regard that justice that lies in the matter of Engagement, soe as to repaire that man by some just way as farre as I can; and hee that doth nott hold this, I doubt whether hee hath any principle of justice, or doing right to any att all in him. That is [if] hee that did nott thinke itt lawfull hath made another man beleive itt to his prejudice and hurt, and [made] another man bee prejudic’t and hurt by that, hee that does nott hold that hee is in this case to repaire [it] to that man, and free him from [the prejudice of] itt, I conceive there is noe justice in him. And therfore I wish wee may take notice of this distinction when wee talke of being bound to make good Engagements or nott. This I thinke I can make good in a larger dispute by reason. If the thinges engaged to were lawfull to bee done, or lawfull for mee to engage to, then [i] by my Engagement am [363] bound to [perform] itt. On the other hand if the thinge were nott lawfull for mee to engage, or [if it were] a duty for mee to have done to the contrary, then I am nott bound positively and actively to performe itt. Nay I am bound nott to performe itt, because itt was unlawfull [and] unjust by another Engagement. Butt when I engage to another man, and hee hath a prejudice by beleiving, I nott performing itt, I am bound to repaire that man as much as may bee, and lett the prejudice fall upon my self and nott uppon any other. This I desire wee may take notice of to avoide falacie on that part. For there is an extremity to say on the one hand, that if a man engage what is nott just hee may act against itt soe as to regard noe relation or prejudice. [267] [there’s an extremity] for a man to say on the other hand, that whatsoever you engage, though itt bee never soe unjust, you are to stand to itt. One worde more to the other parte which Mr. Wildeman doth hold out as a dangerous principle acting amongst us, that wee must bee bound to active obedience to any power acting amongst men.

Wildman.

You repeat not the principle right—“To thinke that wee are bound soe absolutely to personall obedience to any Magistrates or personall aucthoritie that if they worke to our destruction wee may nott oppose them.”

[Ireton.]

That wee may nott deceive ourselves againe [by arguments] that are fallacious in that kinde I am a little affected to speake in this, because I see that the abuse and misapplication [364] of those thinges the Army hath declar’d hath led many men into a great and dangerous errour and destructive to all humane society. Because the Army hath declar’d, in those cases where the foundation of all that right and libertie of the people is, if they have any, that in these cases they will insist uppon that right, and that they will nott suffer that originall and fundamentall right to bee taken away; and because the Army when there hath bin a command of that supreame aucthority the Parliament have nott obeyed itt, butt stood uppon itt to have this fundamentall right setled first, and requir’d a rectification of the supreame aucthority of the Kingedome; for a man therfore to inferre [that] uppon any particular, you may dispute that aucthority by what is commanded what is just or unjust, if in your apprehension nott to obey, and soe farre itt is well, and if itt tend to your losse to oppose itt. [365]

[268]

Mr. Wildman.

If itt tend to my Destruction that was the worde I spoke.

Com̃. Gen.