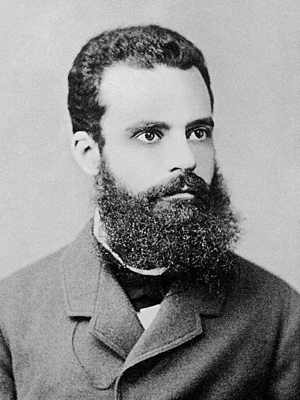

VILFRED PARETO,

"An Application of Sociological Theories" (July 1900)

|

i |

[Created: 6 April, 2025]

[Updated: 5 April, 2025] |

The Guillaumin Collection

|

This title is part of “The Guillaumin Collection” within “The Digital Library of Liberty and Power”. It has been more richly coded and has some features which other titles in the library do not have, such as the original page numbers, formatting which makes it look as much like the original text as possible, and a citation tool which makes it possible for scholars to link to an individual paragraph which is of interest to them. These titles are also available in a variety of eBook formats for reading on portable devices. |

Source

, An Application of Sociological Theories. Translated and edited by David M. Hart (Pittwater Free Press, 2025).http://davidmhart.com/liberty/FrenchClassicalLiberals/Pareto/1900-Applicazione/Pareto_Application1900.htm

Vilfredo Pareto, An Application of Sociological Theories. Translated and edited by David M. Hart (Pittwater Free Press, 2025).

Vilfredo Pareto, “Un’ applicazione di teorie sociologiche,” Rivista Italiana di sociologia, (Luglio 1900), p. 401-456.

Note: This essay was first translated into English in 1968: Vifredo Pareto, The Rise and Fall of the Elites: An Application of Theoretical Sociology. Introduction by Hans L. Zetterberg (Totowa, New jersey: The Bedminster Press, 1968).

This title is also available in the original Italian in facsimile PDF and enhanced HTML.

This book is part of a collection of works by Vilfredo Pareto (1848-1923).

Table of Contents

[401]

AN APPLICATION OF SOCIOLOGICAL THEORIES

(Introduction)↩

The aim of the present study is entirely objective and seeks solely to test certain sociological theories against the facts.

Usually, those who write about sociology or political economy have some practical arrangement they wish to advocate; nor do I wish to blame this approach now, but merely to inform the reader that I do not follow such a path here. It is appropriate to state this clearly, because that custom has had the consequence that an author’s words are understood in a somewhat broader sense than their literal meaning. Thus, if he describes some defect of a system A, it is taken to mean that he generally and entirely condemns that system A, and often, going even further, it is inferred that he is a supporter of a certain other system B, opposed to A.

Whoever finds faults in universal suffrage is understood to favor limited suffrage; whoever recounts the woes of democracy is assumed to be advocating aristocratic government; whoever praises the monarchy in some respects is certainly against the republic, or vice versa; and in general, every statement that is literally partial is interpreted in a general sense. To do this is not entirely wrong, in fact, it often hits the mark, since the author deliberately says less so that more may be understood, and this is a praiseworthy method in literature, though much less so in science. Therefore, it is important for me to emphasize that in the present work, every statement carries no more than its own meaning, and should in no way be understood in a broader sense.

I must also write a few words to explain why I chose to study present facts instead of only past ones. The latter [402] have the very great advantage, indeed, of being considered with a cooler mind and less conflict of feelings and prejudices; but they also suffer the serious disadvantage of being known to us in a very imperfect way. Moreover, the advantage mentioned is often more apparent than real, since we tend to project present-day emotions onto the past. For example, the German historian who is a fanatic supporter of the German empire cannot tolerate anything negative being said of Caesar or Augustus, while our own democrats take offense at Aristophanes.

Let us now turn to the subject at hand and begin by recalling certain sociological laws which, having been induced from the facts, we now wish to test anew, through deduction, against those same facts. In this way, we follow the method recommended by Claude Bernard, which proceeds from fact to idea, and then from idea back to fact. In the fragment published here, the reader will find only the second part; the first, which is considerably longer, will not be missing from the treatise on sociology that I am working on, if, indeed, I am able to complete and publish it. [1] For now, the laws stated should be considered as more or less plausible hypotheses, and we shall see whether they help us explain the facts.

Most human actions originate not from logical reasoning, but from feeling; this is especially true for actions with a non-economic purpose. The opposite holds for economic actions, especially those involving trade and large-scale production.

Although man is driven to act by non-logical motives, he takes pleasure in logically connecting his actions to certain principles, and therefore he imagines these principles a posteriori to justify such actions. Thus, it happens that an action A, which in reality is the result of a cause B, is presented by the person performing it as the result of a cause C, which is often entirely imaginary. The man who in this way deceives others with his claims has first deceived himself, and he firmly believes what he asserts.

It follows from this that every sociological phenomenon has two well-defined and often entirely different forms: an objective form, which establishes relations between real objects, and a subjective form, which establishes relations between psychic states. Suppose we have a curved mirror, objects reflected in it appear distorted: what is straight appears curved, what is small seems large, or vice versa; [403] likewise, in the mind the objective phenomenon is reflected and made known to us through history or contemporary testimony. Thus, if we wish to know the objective phenomenon, we must not be satisfied with the subjective one, but must suitably deduce the former from the latter. This, in essence, is the task of historical criticism, which goes far beyond the material critique of sources and reaches into the critique of the human psyche.

The Athenians, fearful of the Persian invasion, sent to consult the oracle of Delphi, which, among other things, responded that Zeus granted Tritogenia a wooden wall that alone would be impregnable. So the Athenians took refuge in their fleet and won at Salamis. This is how the phenomenon appeared to many contemporaries, and so it was passed down to us by Herodotus. But the objective form is clearly quite different. Today, it is to be hoped that no one still believes in Apollo, in Athena Tritogenia, or even in Zeus, and therefore some more real cause must be sought to explain the victory at Salamis, which, in fact, was prepared by Themistocles when he persuaded the Athenians to use the treasury funds on the fleet. But it is notable that Herodotus, in reporting this, makes no mention of that real cause; a fortunate coincidence had the ships ready, so it was easy to obey the oracle. And according to our author, the differing opinions of the Athenians regarding the best course of action were only concerned with finding the true meaning of Apollo’s response, some believing that the wooden walls referred to the citadel, others arguing that the god was referring to the fleet; and Themistocles himself, still according to Herodotus, spoke solely on the interpretation of the oracle’s words. Thus, the contrast between the real and the subjective phenomenon becomes all the more striking.

It is not enough to seek out the two phenomena and their correspondence; a third problem arises: how the real phenomenon works to modify the subjective one, and vice versa. Darwinism offers a very simple answer to this question, but unfortunately one that is only partly true. According to that doctrine, the correspondence between the two phenomena would be achieved through the removal of those in which such correspondence does not exist.

Yet, in the case mentioned, there was no such removal, and we will never know why the Athenians embraced one [404] interpretation of the oracle rather than another, nor even whether, in his interpretations, Themistocles was sincere. Nowadays, when similar events occur, there is neither absolute credulity nor absolute disbelief; thus, if it were legitimate to judge the people of the past by those of today, we would be inclined to believe that the real cause, Athens' naval power, was influencing Themistocles unconsciously, and that, so impelled, he first persuaded himself and then others that the god had indeed meant the fleet.

The example we have chosen may seem to some superfluous because it is too obvious, but whoever thinks so would quickly change their mind if presented with some modern example, essentially identical to the ancient one. [2] How many in France invoke the “immortal principles of 1789” and the “defense of the republic,” or in other countries the “defense of the glorious monarchy,” just as Themistocles interpreted the oracle, and thus give imaginary reasons for their actions, while concealing the real ones? It has always been true that we see the speck in our neighbor’s eye but not the beam in our own, and those who laugh at ancient superstitions have very often merely replaced them with modern ones, which are no more reasonable or real than the old.

Let us turn to much less well-known considerations, which must later be combined with those just noted.

Economic crises, which, to tell the truth, are simply a particular case of the law of rhythm that Spencer assigned to [405] movement in general, have been carefully studied in our times, especially through the work of Jevons, Clément Juglar, and other capable men. In my Cours d’Économie politique, [3] I expressed the opinion, which further studies have confirmed, that these crises depend not only on purely economic causes, but also on human nature, and are nothing other than one of the many manifestations of psychological rhythm. This rhythm appears in other forms too, as I also noted at the time; in moral philosophy, in religion, in politics, one observes fluctuations very similar to the economic ones. [4] These did not escape the notice of historians, but, except for theories such as that of (historical) cycles, which stray too far from the truth, they were generally not considered as partial manifestations of rhythmic movement. Only here and there is some analogy noted among the most striking examples. [5]

All those who have studied Roman history have observed the great fluctuations by which the educated classes [6] passed from incredulity, as it appears toward the end of the Republic and in the first century of our era, to credulity, which we find toward the end of the Empire.

The religious current from which Christianity later emerged—Christianity which triumphed not without deeply transforming itself and not without broadly assimilating the principles of competing doctrines, was general and overwhelmed the entire ancient world. Pagan authors hold Christian-like maxims and thoughts, so much so that it was even supposed there were relations between Seneca and Saint Paul to explain the former’s sentiments. Renan recognized that Christianity was nothing more than one of the many forms taken at that time by religious feeling. [7] We are used to seeing in the history of that time a battle between Christianity and other [406] religions or doctrines, which we assume to be essentially different, and we imagine that modern history would have been entirely different had the cult of Mithras, or some other Oriental cult, triumphed instead of Christianity, or if paganism had been reborn.

None of this holds up. A fierce battle did indeed exist among the sects A, B, C..., all of which stemmed from a single cause X, namely, the heightened religious feeling. But the principal fact is precisely X, and the facts A, B, C... are merely secondary. It cannot be said that they had no importance at all, since form also has some value in modifying phenomena determined by substance, but the error lies in giving first place to something that belongs in second.

D'Orbigny, speaking of Bolivia, says:

“At the entrance to the valley and at the summit of each slope, I noticed all along the road mounds of stones of various sizes, most often topped with a wooden cross... I learned, and later had the opportunity to confirm by finding them throughout the part of the Republic of Bolivia inhabited by the Indians, that these were apachectas. These mounds existed before the arrival of the Spaniards. They were made by burdened natives who, laboriously climbing the steep slopes, gave thanks to Pachacamac—or the invisible god, mover of all things—for having given them the strength to reach the summit, while also asking him for new strength to continue their journey. They would stop, rest for a moment, throw a few eyebrow hairs to the wind, or else deposit on the pile of stones the coca they were chewing—as the most precious thing to them—or if they were poor, they simply picked up a stone from the surroundings and added it to the pile. Today, nothing has changed; only now the native no longer thanks Pachacamac, but rather the God of the Christians, whose symbol is the cross.” [8]

“In Sicily,” says Maury, “the Virgin took possession of all the sanctuaries of Ceres and Venus, and the pagan rites were in part redirected toward her.” [9] Now, here it is evident that there is a common feeling, which manifests in various forms, and that those forms are of secondary importance compared to the feeling. “The fountain,” Maury adds, “continues to receive in the name of a saint the [407] offerings it once received as a deity.” [10] In this case, what is the principal fact? The feeling that drives people to propitiate the fountain, or the manifestation of that feeling through invocation of this or that saint, this or that divinity? The answer is not in doubt. Believing that the intervention of some divine being can heal the eyes is the principal fact; turning therefore to Asclepius or to Saint Lucy is secondary. The same holds for invoking the Christian Devil instead of the pagan Hecate, the principal point is the belief in the power of such invocation. It is not entirely accurate to represent one belief as having originated from the other; it is far closer to the truth to see them as having both arisen from a single source, namely the human feeling that one can compel mysterious powers to serve oneself.

Now it becomes clear how the victory of sect A over sects B, C... is often a victory of form and not of substance. Between the ideas of Lucian, on one hand, and those of the admirers of the prophet Alexander, on the other, there is certainly a question of substance; and if mankind had been won over by Lucian’s ideas, the history of Europe would be entirely different from the one we know. But between the ideas of the admirers of Alexander and those of the admirers of other prophets, it is, if not exclusively, almost entirely a question of form, and history would have changed very little if these or those had won, especially since the victor is always forced to make, even in form, concessions to the vanquished.

This is not the place to investigate how those great currents of feeling arise and gain strength, whether they originate, as the materialist interpretation of history claims, solely from economic conditions, or whether other causes, which cannot be reduced to these, also contribute. Attempting to solve all problems at once is an essentially unscientific method; instead, they must be studied one at a time. Today, we take the existence of these currents as a given; at another time and place, we will attempt to delve further into the inquiry.

Men, usually unaware of being swept up by these currents, and who, as already noted, wish to present as voluntary what is involuntary, and as logical what is illogical, come up [408] strangely imaginary reasons, and with these they deceive themselves and others about the true causes of their actions. Often the formal disputes among sects A, B… dissolve into incoherent arguments; and anyone, for example, who studies the quarrels of the Christian sects during the Byzantine period ends up feeling as though they are in a madhouse. And generally, even when some question of substance lies beneath these formal disputes, one is reminded of what Montesquieu said of theological books: “Doubly unintelligible, both because of the subject matter they treat and the manner in which they treat it.” [11] When reading the speeches of certain French “nationalists,” one begins to doubt whether those people are entirely sane, yet beneath those words, insipid in appearance and in fact, there lies a most serious question of substance, since “nationalism” is now the only form in which resistance to socialism takes shape in France.

Even when a dispute is reasonable, it rarely happens that the reasons given refer to the substance. In France, on the eve of the 1789 Revolution, people spoke of nothing but “humanity,” “sensibility,” “fraternity”, while in fact, Jacobin massacres and looting were being prepared. Now the old game begins again, and our bourgeoisie eloquently speaks of “solidarity,” all while preparing for itself disasters that will reduce it to nothing.

People, except during brief intervals, are always governed by an aristocracy, [12] understanding this term in its etymological sense and using it to mean the strongest, most energetic, and capable individuals, both for good and for ill. [13] But due to a physiological law of great importance, aristocracies do not last, and thus human history is the history of the succession of these aristocracies: while one rises, another declines. This is the real phenomenon, though it often appears to us in another form. The new aristocracy, which wants to overthrow the old or even just to share in its power and honors, does not frankly express this aim, but instead becomes the champion of all the oppressed. It claims to seek not its own benefit, but that of the many; and it launches the assault not in the name of the rights of a narrow class, but in that of the rights of nearly all citizens. Needless to say, once victorious, it forces its allies back under the yoke, or at most grants them some superficial concessions.

[409]

Such is the history of the struggles between the aristocracy of the plebs and the patricians at Rome; such also, well noted by modern socialists, is the history of the victory of the bourgeoisie over the aristocracy of feudal origin.

Professor Pantaleoni, in a recent work [14], denies that socialism is destined to win; I have maintained that its victory is highly probable and almost inevitable [15]. The two opinions may seem contradictory, but they are not, because we are speaking of different things: Pantaleoni turns his mind to the subjective phenomenon; I, to the objective one. In the end, we are in agreement.

Suppose that, when the first Christian communities were arising in Judea, someone had reasoned as follows: “These people will never rule the world. It is a fable to believe that all differences in wealth, education, and social rank can vanish among men. It is foolish to suppose that all men will truly be brothers, that they will renounce all sensual pleasures, that in a woman’s flesh they will see only the splendors of eternal life. Rest assured that a thousand years from now there will still be rich and poor, kings and subjects, powerful and humble; be certain that many living people will still be conquered by gluttony, lust, and rage, and that these new brothers will even kill each other by treachery.” This person would have spoken truly, and certainly the kingdom of Christ, as imagined by the first Christians, is still far off; but whoever had asserted that Christianity would be victorious would also not have spoken falsely, and the facts bear witness to this. A single name here indicates many different things.

A more complete comparison can be drawn from times closer to us, and therefore better known. Let us pretend we are in France at the dawn of the 1789 Revolution. One man says:

“These good folks who want to reform the State are dreaming. But who can believe in that social contract? — The general will cannot err. — Bravo, and that’s why there’s no error so gross, no insane superstition that hasn’t had nearly a whole people, and often almost all people, on its side at some time and place. — Men are all born good; only priests and kings make them bad. — Yes, not even children believe these fables anymore. If your new government is based on that fine principle, you’ll have to wait many thousands of years [410] before seeing it in practice. — The reign of reason is at hand. — What a poor psychologist you are; the majority of human actions will continue for many, many centuries to be determined by feeling. — Under the empire of reason, good, honest, virtuous, ‘sensitive’ commoners will gently and peacefully change the present state of affairs [16]. — Whoever believes that can also believe that the fiercest beasts have become gentle doves. Get out of here—your entire literature rests on falsehood; and your elegant ladies swooning as they chirp about the virtues of ‘natural man’ are silly girls who don’t know what they’re saying. The next century, rest assured, will have men more or less like those of our own, and the new era longed for by your philosophers is not about to dawn.”

Another replies:

“Excellent; all of that is true. Neither now nor ever will ochlocracy (mob rule) stably govern. You are right, the idyll of peace and virtue sung by our philosophers is about as real as a fairy tale. But look beneath those words and see what lies hidden: you’ll see the rise of an oligarchy which seeks to overthrow and replace the one that currently governs us. The victory of this new oligarchy is certain because energy and strength lie on its side. That victory could be bloodless if the old aristocracy were strong, and at the same time tolerant and wise—if, mindful of the saying si vis pacem, para bellum (if you want peace prepare for war), it showed itself on one hand prepared to fight manfully, and on the other hand knew how to suitably welcome into its ranks all those rising from the plebs who are about to form the new aristocracy [17]. Instead, the change will cost the old aristocracy many tears and much blood, because it, almost struck by madness, on one side disarms and weakens itself with foolish humanitarian declamations, and on the other rejects the new aristocracy, thus forcing it to wage battle.”

[411]

Events unfolded precisely in a way that showed both opinions to be true, and they are by no means contradictory.

De Tocqueville observed that “the French Revolution was a political revolution that acted like a religious one and in some ways took on its appearance.” One may set aside what is debatable in this statement and firmly state that the French Revolution was a religious revolution, prepared by the upper classes, [18] later carried out against them, and which gave power to a new chosen class—namely, the bourgeoisie.

It has been said that the Revolution was the daughter of Voltaire and the Encyclopedists; this is true only in a small part and in a certain sense, namely, in the sense that humanitarian skepticism had enfeebled the upper classes. The influence of Voltaire and the Encyclopedists on the lower classes [19] was virtually nil, and the Revolution was primarily a reaction of the religious sentiments (understood in the broad sense) of the lower classes against the skepticism of the upper classes. The same occurred, in part, at the time of the Reformation. Then too, the theocratic upper classes were becoming skeptical, and the popes cared much more for earthly matters than for heavenly ones. It is no coincidence that the Reformation arose among the rough northern people, where Christian religious sentiment was stronger, and made few converts in refined and skeptical Italy. At that time, the religious reaction took a Christian form; in 1789, in France, it took the form of a social, patriotic, revolutionary, and even anti-Christian religion. In both cases, the sentiments were of the same kind, though they took different forms.

The rule of the new aristocracy born of the French Revolution, that is, the bourgeoisie, has lasted briefly and already shows signs of steep decline, at least in France, barely a century after its rise. It is true, however, that in the United States of America, in Germany, and in other countries, it still retains considerable strength.

If we consider the phenomenon from the objective standpoint, three major categories of facts strike us: 1. a growing intensity of religious feeling, which shows that we are in the ascending period of the crisis; [20] 2. the decline of the old aristocracy; [21] 3. the rise of a new aristocracy. [22]

Subjectively, the first of these categories is perceived by the mind without being too distorted; however, the other two [412] take on a form very different from the real one: the decline of the old aristocracy appears as the growth of humanitarian and altruistic sentiments; the rise of the new aristocracy appears as the vindication of the humble and the weak against the powerful and the strong.

The ascending period of the religious crisis.↩

Even the most superficial observation is enough to see that, among civilized people, religious sentiment has grown in recent years and continues to grow. This has benefited not only already existing religious forms, such as the various Christian denominations, but has chiefly given strength to a new order of religious sentiments, which are manifested in socialism. Many able men, both among the socialists and their opponents, have clearly seen that socialism is now a religion; and anyone who studies history must recognize that this religious phenomenon is among the most magnificent ever seen, and can only be compared to the rise of Buddhism, Christianity, Islam, the Protestant Reformation, or the French Revolution.

Moreover, patriotism has become exalted and takes on the form of religion: in Germany, where an authoritative journal even speaks of the “German god”; in England, with imperialism; in France, with nationalism; in the United States of America, with jingoism, etc.

Alongside these great phenomena, which appear in the revival of ancient religions and in the birth of a new and powerful one, other lesser phenomena show us how religious sentiment is invading all expressions of human activity; in fact, it seems that these now have an irresistible tendency to take on a religious form [23].

Here, for example, are some good people who believe that the use of alcoholic beverages is harmful to the human race. Their activity does not remain within the modest and tempered limits of an ordinary hygienic measure but extends even into the realm of religious exaltation [24]. [413] Ascetics, apostles, martyrs arise, ready for every sacrifice, provided they can prevent a human being from drinking a glass of wine; and when they succeed, they say they have “saved a man,” just as the Christian apostle says he has “saved a soul” [25]. There are [414] sects, such as the anti-alcoholic one called the Buoni templari (Good Templars), that can be compared to religious congregations like the Dominicans, Franciscans, or others of the sort. They have initiations, cultic ceremonies, mysterious bonds, and they exalt themselves with mystical harangues. Moreover, not a few hygienists nowadays are so zealous in defending their doctrines that they seem mad to anyone who has not completely lost the light of reason; and they would almost go so far as to kill a man in order to keep him healthy, less reasonably than the Inquisition, which burned him to save his soul.

Others have taken it upon themselves to hunt down “immoral literature,” and they too go beyond the moderate limits of honest censorship. Certainly, among them are highly respectable people, deserving of every praise, but it is strange to see how there are people so fixated on this subject that they cannot, they are unable to turn their minds to anything else. These individuals express the most moralistic concepts in the most indecent terms; in one place, they even had students in secondary schools sign a petition to shut down brothels, and the wording of the petition was obscene. Sometimes, when speaking with one of the more fanatical among them, you see his face flush, his eyes gleam, and, in short, all the signs appear that are seen in a man when he longs for a woman, while this fellow endlessly discusses sexual union and shows an incredibly intense hatred for any man who enjoys amorous pleasures.

But here, besides religious feeling in general, another cause is at work, which, if I am not mistaken, is the following. It has already been observed that sometimes erotic feeling takes on the guise of religious feeling, and many such cases have been reported, especially among hysterical women. Now it happens that there are some men who, had they lived in another time, for example, toward the end of the eighteenth century, would undoubtedly have given in to the erotic feelings that dominate them, but who today, feeling remorse due to the different environment in which they live, withdraw from action as much as they can, and feed their uncontainable appetite with words. In short, they are happy to find an opportunity [415] to concern themselves morally with something immoral and to be at peace with their conscience while procuring for themselves a certain kind of enjoyment [26]. A friend of mine knew a rich and beautiful lady, not exactly chaste in her younger years, who, as she aged, but still had the power to stir desire, became deeply and sincerely religious, and with admirable zeal and great sacrifices, dedicated every moment to an endeavor to lead prostitutes away from vice. My friend was convinced of the honesty of her intentions and explained her incredible fervor for that apostolate by the idea that, in doing so, she obtained a reflection of the past and still longed-for pleasures, not only without remorse but indeed with the conscience of doing a good deed. As for the bitter hatred that some fanatical moralist shows toward the less ascetic man, it originates not only from that religious and sectarian feeling that demands the heretic be silenced and destroyed, but also from that envy which, unconsciously and unwillingly, is felt by the non-pleasure-seeker toward the pleasure-seeker, the eunuch toward the virile man.

Vegetarians are also a fairly ridiculous sect. They have calculated that cultivated land can produce far more wheat and rice than meat, and so they want to take meat away from us to increase the supply of food. A mystical-social sect has also arisen, which, citing certain physiological experiments in support of its thesis, claims that we all eat too much and wants to put us on a strict diet. With this, these worthy individuals say, “the social question” will be solved, because there will be food for a larger number of people, and above all, it will be possible to have many more children. For these poor fanatics, there is no greater crime than the union of man and woman without the birth of a child. Malthus is their Satan; they would burn all Greek and Latin poets for being insufficiently chaste; their ideal is a nation of ascetics who do not eat meat, do not drink wine, and do not feel any emotion of love except [416] liberorum quaerendorum causa (for the sake of having children), and whose only pleasure will perhaps remain to sing hymns to solidarity. [27]

These ascetics are to the socialists as the Montanists are to the orthodox Christian church. That church always had much to do to rid itself of those who foolishly exaggerated its doctrine; expelled on one side, they reappeared on the other, down to the flagellants of the Middle Ages and the visionary Jansenists [28].

[417]

Anyone living in Italy and who has not spent a long time abroad, long enough to know not only the majority, who are sane, but also the little cliques of fanatics, cannot have a clear idea of the doctrines of modern ascetics and will think exaggerated those accounts that still fall far short of the truth [29]. Italy has always been, since Roman times, a rather irreligious country. Who knows whether it may one day produce a new Renaissance, like the one too soon halted by the Protestant Reformation.

Spiritism, occultism, and other such superstitions now have quite a few followers and gain strength from the general growth of religious sentiment. Here we have people who take seriously the ravings of a poor hysterical woman who writes in the language spoken on the planet Mars; and on that fine scientific topic, conferences are held, attended by crowds of women and girls enamored of mysticism. The archangel Gabriel chirps in Paris through the mouth of a young girl; charlatans of every kind cure the sick with mystical operations; and if we lack a Lucian to narrate their deeds, we are not lacking those who play the part of Alexander of Abonoteichus.

When we are not in the ascending period of the crisis, such fantasies remain within a small circle of men and have little effect; but during that period, their influence greatly expands and helps to accelerate the general movement.

In literature, in art, and in science, mysticism, “symbolism,” and other such vanities which appear to be something make wide inroads. You may still choose the religious form to which you want to dedicate [418] a hymn [30], but the hymn must not be lacking anything, otherwise, the public won’t buy the book, and no publisher will want to print it.

Our new mystics believe they are reasoning, but in reality they gravely offend logic and most often can do no more than repeat the nonsense of ancient mystics. For example, to prove, let’s say, that there is some truth to a story about the transmigration of a human being to the planet Mars, they tell us with great solemnity that “science cannot explain everything.” Very true; but just because Titius cannot explain a phenomenon, it does not logically follow that he must accept Caius’s explanation. If Titius does not know what thunder is, he is not, therefore, logically compelled to agree with Caius that it is produced by Jupiter. Others, with more refined cunning, repeat an argument that is also quite old and, in essence, say: “This thing must be true because it is useful for man that it be true.” Now people have rediscovered a truth known for many centuries: that man is guided by feeling [419] more than by reason. From this, one may deduce that religious feeling plays a notable role in maintaining the social order, but from that alone, one cannot determine precisely how large that role must be in order to achieve the greatest social utility. Still less can one deduce that form A, rather than forms B, C, etc., is the one useful to mankind. A line of reasoning that essentially says: “Man is largely guided by feeling, therefore he must completely submit to a religion, which therefore must be A,” is a type of illogical reasoning. The anti-alcoholics inject wine under the skin of a little animal, which dies in convulsions, and from this they deduce, as a logical consequence, that man must not drink wine! They even experiment on humans. They observe that in someone who has ingested alcoholic beverages, the transmission of sensations to the brain becomes slower for a short time. From this, they conclude that alcohol is a poison to the nervous system and that man must abstain from it. If such reasoning is logical, then so is the following: Immediately after eating, while one is digesting, the brain becomes sluggish and all intellectual operations slow down; therefore, food is a poison to the nervous system, and man must abstain from it… and die of hunger. If, as some say, the use of alcoholic drinks will destroy the species in a few years, [420] then the water-drinkers need only let time do its work, soon, through natural selection, they alone will remain in the world. In fact, it is astonishing that since the days of Noah, this hasn’t already come to pass.

They say that, in the name of “solidarity,” A must give money to B, because A must take pleasure in B’s well-being; but by the same logic, B should, again in the name of solidarity, refuse to plunder [31] A and cause him serious harm and displeasure. It is observed that society is an organic whole, and that the suffering of one part B of that whole reverberates onto part A; from this it is deduced that A must help B—and must help in a certain way. The conclusion is not logical. 1. A might just as well eliminate B, as one has a limb amputated when gangrene sets in. 2. If that method of helping B results in the proliferation of degenerate individuals unsuited to their environment, then the help given to B will harm not only part A, but all of society.

It is a vain effort to demonstrate the falsity of such arguments, since the men who use them were not persuaded by them in the first place, but rather invented them to justify after the fact what they were already persuaded of; and so, even if it were to happen, though it would be most unusual, that the demonstration was so clear and compelling as to impose itself upon the minds of those men and to force them to abandon those arguments, nothing would be gained except to see them replaced by others equally or even more erroneous, while their belief, which arises from an entirely different origin, would remain unaltered, with very rare exceptions.

Not even the positive sciences are safe from the invasive religious sentiment. An esteemed astronomer, H. Faye, while discussing the origins of the solar system, feels the need to say:

“Let us not leave these primitive times without paying homage to the first chapter of Genesis. It proves that humanity did not begin either with the silliness of fetishism, or with the charming absurdities of polytheism, or with the degrading fantasies of astrology.” [32]

Who knows whether the author truly believes that the first chapter of Genesis describes primitive humanity? Has he never heard of historical research on ancient people, nor of studies on prehistoric humans? He ends his book saying that life will one day end, “but we hope, we [421] believe that it will not be the same for the works of intelligence that will have brought us closer to our divine model. These do not need light, nor warmth, nor a new earth in order to persist; they are preserved so as not to perish.” It is not clear what the author means or how these “works of intelligence” will persist when all life has been extinguished. Faced with such babble, the doctrine of metempsychosis is a model of scientific precision. Luckily, among the “works of intelligence” destined to survive when the earth is deserted by every living being, the author did not include “solidarity”; perhaps we shall find it turning up in some other astronomy treatise. A Laplace once spoke quite differently from Faye, but wise men change with the times.

Even the Copernican and Galilean theories are now indirectly under threat. Mansion, a competent mathematician, in a communication to the International Scientific Congress of Catholics (April 4, 1891), wrestles to show that the Ptolemaic system was ultimately just as valid, or almost, as the modern one:

“Another, deeper reason for choosing the geocentric system is the following: the ancients clearly distinguished between astronomy as a science of celestial phenomena and the search for the causes of the movements of the stars... Hence, the choice of astronomical hypotheses was indifferent to them, and there was no drawback to adopting the geocentric viewpoint, more in keeping with appearances and of more direct application than the other.”

Still, it takes quite a bit of gall to try to convince us that the ancients could have followed Newtonian theory, had they wished, but chose Ptolemy’s because it was “more in keeping with appearances and of more direct application.”

Brunetière, who knows very little astronomy, exclaims: “Leave us in peace with your Galileo”; our author, who is a capable scientist, skirts around with subtle distinctions:

“In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, before and after the trial of Galileo, the distinction between the philosophical explanation of astronomical phenomena and the astronomical explanation itself was familiar to scholars; at that time, thanks to this distinction, it was perfectly understood that Galileo could be condemned in the name of philosophy without this in any way hindering astronomical research.” [33]

[422]

Poor Galileo, if he came back to life, our neo-Catholics would probably throw him back in prison! That gentleman Mansion is moderately amusing when he tells us that having condemned and imprisoned Galileo “did not in any way hinder astronomical research.”

Leaving aside now these secondary signs and returning to the main ones, it seems likely that the rise of religious feeling will benefit socialism more than the old religious forms, since it is a new form. This has generally been the case in great religious crises. Whether that advantage will extend to the destruction of the old beliefs, as happened with Christianity in relation to paganism, or whether it will allow them to coexist, as with Buddhism and the Protestant Reformation, is still unclear; but the latter hypothesis seems to me more likely, provided, of course, that socialism modifies itself and borrows heavily from its competing religions.

The resemblance between the current socialist movement and the rise of Christianity has often been noted; but the resemblance with the Protestant Reformation, although less well known, is no less true. And let it be well understood that we must not stop at such analogies, but rather we will find others wherever a great [423] religious crisis manifests itself; and we shall soon see that the analogy goes beyond the purely religious phenomenon.

It is striking how even in certain details the correspondence is exact. It is well known how the first Christians believed that the Kingdom of Christ would soon come upon the earth, and just a few years ago, socialists believed the triumph of their doctrine was imminent. Engels made predictions in this regard that facts have already disproved, and now similar forecasts re-emerge, for a somewhat more distant future, just as they did among Christian millenarians.

“When,” says Lactantius [34], “the earth shall be oppressed and men lack the strength to resist tyrants, who, with a great army of thieves, hold the world in subjugation, then divine aid will be needed for so great a calamity.”

And the socialists said and say: when wealth is concentrated in a few hands and economic crises grow more frequent and intense, collectivism will necessarily come to the world’s aid.

“The earth,” says Lactantius [35], “shall show its fertility and spontaneously produce abundant fruits. The mountain rocks shall drip with honey, wine shall flow in streams, and rivers of milk shall flood the land; the world shall rejoice, and all nature shall be joyful, freed from the reign of evil, impiety, crime, and error.”

A similar happiness awaits the world under collectivism, and many, among them let De Amicis suffice as an example, describe it.

Some Christians grew tired of waiting for the Kingdom of Christ to soon arrive on earth, and the more prudent among them realized that, to defeat their adversaries, they had to be more practical and more compromising. So, keeping the original doctrine as an ideal goal, in practice they conformed to the ordinary way of life and common concepts. Likewise, socialists now act with the “minimum program,” and Bernstein frankly points to the new path. In Holland, intransigent and revolutionary socialism is disappearing and giving way to state socialism. [36] Others have gone, and now go, even further and draw closer to the secular world. In France, socialists have become a party of government, and Millerand is part of the Waldeck-Rousseau ministry. In England, the majority of the Fabians voted in favor of imperialism; in Germany, there are many socialists who [424] would like to make love to the empire: Pastor Naumann, in his book Demokratie und Kaisertum, openly preaches that the emperor should be the head of the socialists. That Christian collectivist also preaches militarism, war and extermination for Germany’s enemies, and even for those who, without being enemies, do not wish to be its slaves [37]. From the day Jesus preached love and peace in Galilee to the day when warrior prelates donned breastplates over their vestments and killed in the name of the divine master, several centuries passed; but from the day when the German Marx announced the good news to the proletarians to the day when some German socialists replaced the motto “Proletarians of the world, unite” with “Proletarians, kill one another,” only a few years have gone by.

From these facts we shall later draw further consequences; for now, let it suffice to note that, just as in economic crises, in the present ascending period of the religious crisis, the signs are already appearing of the forces that will bring about the descending period. Naumann and his associates are neither religious, nor Christian, nor socialist, they are shrewd individuals who seek to profit from the beliefs of others, just as the popes used the meagre offerings made by Christians to build Saint Peter’s, or worse, spent it on pagan festivities. After those politically practical socialists have prevailed, some man who has preserved the old socialist faith will repeat: Ah Constantine, how much evil was born of you, and the rest that follows; and he might also add:

Now tell me, how much treasure did our Lord

Require from Saint Peter, before

He placed the keys in his keeping?

Surely, he asked no more than: Follow me.

That is: how much treasure did Marx ask of Liebknecht or of Bebel to consecrate them as his disciples?

[425]

Another illusion that will surely appear in the descending period is hypocrisy, which is now almost entirely absent from the socialist faith in countries like Italy, where socialism is persecuted, but is already peeking out in other countries like France, where the socialists are part of the government. Many politicians have become socialists to get elected to some public office, many writers to sell their books, many playwrights to please the public, many professors to obtain a university chair. Still, the evil is not yet widespread. In countries like Italy and Germany [38], where socialist faith demands sacrifice, the hypocrites keep their distance; they will flock in droves only when it begins to bring honor, power, and wealth.

Nor are hypocrites lacking in those areas we earlier identified as secondary manifestations of religious sentiment. In one city, no need to name it, the president of a society “for the uplift of morality,” which condemns sexual union outside of legal marriage as the greatest of all crimes, was forced to flee because he was being blackmailed by a prostitute who claimed to have borne him a child. At a congress against immoral literature, the president had to warn members that certain obscene prints had been brought to the congress only to arouse righteous indignation, not so that some might secretly pocket them. In Paris, there are students and young doctors who, in public, pretend to abstain from alcoholic beverages in order to win the favor of professors who are fanatical anti-alcoholics, while in private they indulge liberally not only in wine but in spirits. An anonymous author, who seems to have eluded the invasive religious sentiment, left us in the Greek Anthology an epigram joking about Irene, meaning “peace” and also a woman’s name, where it is written: “Peace to all, says the bishop as he comes; but how can she be with all, she who is shut up for him alone?” [39] Thus had the evil seed already sprouted early [426], which would later bear so rich a harvest. Wait a little, and Boccaccio’s mocked friars will find worthy successors.

In every age, human thought tends to express itself in the forms current in society. A few centuries ago, every discourse was clothed in the language of Christian religion. Machiavelli ridicules this custom when, in the Mandragola, he has Friar Timoteo cite sacred authors and Christian doctrine to persuade Madonna Lucrezia to give in to her lover’s desires. Today, Friar Timoteo would have brought up “solidarity” and humanitarian maxims [40].

Another similarity between the present crisis and others should be noted: the proliferation of sects. Early Christianity maintained unity and orthodoxy through the institution of the papacy. So far, the congresses, or ecumenical socialist councils, have been able to maintain a certain degree of unity, and in Germany, Bebel and Liebknecht have managed, if not to dispel, at least to quiet heresy; but the question remains open for the future, and the approach taken will be worth observing.

The decline of the old aristocracy.↩

This aristocracy, still the ruling class, [41] consists mainly of the bourgeoisie, and to a small extent of remnants of other aristocracies.

When an aristocracy declines, two signs are generally observed to appear simultaneously: 1. That aristocracy becomes more gentle, more mild, more humane, and less able to defend [427] its own power. 2. On the other hand, its greed and covetousness for the property of others does not diminish, and it strives as much as it can to increase its unlawful appropriations, to make greater usurpations upon the national patrimony. So that on one side it makes its yoke heavier, and on the other has less strength to maintain it. From these two elements arises the catastrophe in which that aristocracy perishes, whereas it could have survived had one of the two been absent. Thus, if its power does not diminish but grows, it may also increase its appropriations; and if these diminish, it may, though more rarely, preserve its dominion with less strength. Thus the feudal nobility, when it was on the rise, could increase its usurpationsbecause its power was also growing; thus the Roman aristocracy and the English aristocracy were able, by yielding at the right time, to preserve their power. Instead, the French aristocracy, eager to preserve its privileges, and perhaps even to increase them, while its power to defend them was dwindling, provoked the violent revolution of the late eighteenth century. In short, there must be a certain balance between the power a social class enjoys and the force it has at its disposal to defend it. Power without force is something that cannot last.

Aristocracies often end in anemia; they retain a certain passive courage but entirely lack active courage. One is astonished to see how, in imperial Rome, the men of the aristocracy, without attempting the slightest defense, committed suicide or allowed themselves to be killed, simply to please Caesar; a similar feeling of astonishment strikes us when we see how many nobles in France died on the guillotine instead of falling in battle, weapons in hand [42].

[428]

To great amazement, Rome saw the ancient aristocratic vigor blossom again in Silanus. Besieged in Bari, he replied to the centurion urging him to open his veins (suadentique venas abrumpere) that he was ready to die, but also to fight, and though unarmed, he did not stop defending himself and to strike with his bare hands as best he could, until he fell, as in combat, pierced by wounds received from the front [43].

Had Louis XVI possessed the spirit of Silanus, he might have saved himself and his own, and perhaps spared his nation much blood and sorrow. Even on August 10, he could still have fought with hope of victory. “If the king had wished to fight, he could still have defended himself, saved himself, and even won,” says Taine [44].But the aristocracy of that time closely resembled today’s bourgeoisie, [429] as we see in countries like France, where democratic evolution is most advanced. Taine speaks of that era, and his words precisely describe France’s present condition when he says:

“At the end of the eighteenth century, in the upper and even in the middle class, there was a horror of blood; the gentleness of manners and idyllic dreams had softened the will to fight. (And now the French bourgeoisie dreams sweetly once more.) Everywhere, magistrates forgot that the maintenance of society and civilization is an infinitely greater good than the lives of a handful of criminals and madmen, that the primary purpose of government—like that of the police—is the preservation of order through the use of force.” [45]

The same phenomenon was seen in Rome and prepared the fall of the Empire [46]; and now, once again, we see it repeating among our bourgeoisie, so that the end will likely not differ from what has previously been observed [47].

At present, this phenomenon can be seen in almost all civilized states, but it is most evident in France and Belgium, which are the countries furthest advanced in radical-socialist evolution and, in a certain sense, mark the goal toward which evolution in general is trending.

A superficial observation is enough to see that in those countries the ruling class is being swept along by a sentimental and humanitarian current entirely similar to the one that existed at the end of the eighteenth century. The sensitivity of that class has become almost morbid and threatens to render penal laws entirely ineffective. Every day, new laws are devised to come to the aid of poor thieves, charming murderers, and where no new law exists, a convenient [430] interpretation of the old one comes to the rescue. At Château-Thierry, a judge, now famous, sets aside the law and rules according to the blind passions of the mob [48]. The bourgeoisie resigns itself and remains silent. If another judge dares to do his duty, he is viewed with suspicion, and even ridiculed on the stage. With all repression lacking, vagabonds have become a true scourge in the countryside; in isolated cottages, they make demands under threat; out of vengeance, malice, or mere recklessness, they set fire to the castles of the wealthy, arson has now become frequent. The authorities see all this and do nothing, because they know that if they rigorously perform their duty, there will be questions in Parliament and perhaps the fall of the ministry. Even stranger is the behavior of the victims, who remain silent and resign themselves, as if facing ills for which there is no remedy. The more courageous among them merely hope that some general or other will repeat the operation of Napoleon III and rid them of this plague.

Crimes committed during strikes go unpunished; judges sometimes pronounce a sentence, but it is only formal, pardon follows immediately, either imposed by the workers or spontaneously granted by the government, “to pacify the spirits.” The workers have inherited the privileges of the gentlemen of old, they are, in fact, above the law. They even have a special court of their own, namely that of the probiviri ("Honest Men" or Arbitrators), who always condemn the “employer” and the “bourgeois,” even when they are entirely in the right. Where there is [431] that parody of justice, the honest lawyer advises you not to file suit, for you would surely lose. Naturally, socialist democracy wants to extend the jurisdiction of that exceptional court. The ecclesiastical court was abolished, and behold, the workers’ court has arisen. Athenian democracy ruined the rich through lawsuits, it was imitated by the democracies of the Italian republics [49], and it is now imitated by modern democracy. For that matter, aristocracies, when they held power, did worse still; thus, nothing can be concluded from these facts against this or that form of government [50] they are simply [432] a sign indicating which class is declining and which is rising. Where class A has legal privileges and the laws are interpreted unjustly in its favor and against class B, it is evident that A dominates or is about to dominate B, and vice versa.

Jury verdicts are also a sign in that direction, showing that the bourgeoisie has adopted the worst sentiments of the mob.

Where a little romance is involved, bourgeois sentimentality reveals itself as stupidly malicious. Among many examples, one recent case will suffice. A gentleman, himself childishly sentimental, marries a prostitute “to rehabilitate her”; later, living together becomes impossible, he seeks a divorce, and his wife kills him. The jury acquits her, and listen now to the fine reasoning of the accused:

“One cannot grieve for a man who, in the decline of life, fails to complete the good deed he began. What I regret is that I was forced to kill him because he left me. I also killed him because he asked for a divorce, because he covered me with disgrace, staining his name at the same time. Divorce, me? Never! So there was only one solution.” [51]

One sees here the influence of feminism and of all the declamations on stage, in novels, in the press, in defense of prostitutes. The murdered man had been infected with these very theories, he wrote to his wife: “I had taken you like Fantine from Les Misérables, and I had faith in your rehabilitation.” What a good man! Instead of listening to Victor Hugo, to Dumas fils, and to other praise-singers of the fallen woman, [433] he would have done better to marry an honest girl. Certainly, the fault he committed in believing such empty rhetoric may have merited punishment, but death was perhaps a bit excessive. And moreover, the manner and the person by whom it was inflicted offend justice. It may appear, to anyone not entirely drunk on “humanitarian” doctrines, that those good, sentimental, feminist jurors might have had at least some doubt about the theory that whoever “does not complete a good deed once begun” deserves to be killed by the very person he sought to benefit.

The fate of that humanitarian so poorly rewarded is an image of what befell the humanitarian French aristocracy at the time of the Revolution, and of what awaits our bourgeoisie, which will surely atone, through plunder [52] and perhaps even the noose and the guillotine, for the sin of “not completing the good deed” to which it is now entirely devoted, if not in deeds, then at least in words, by striving to uplift, rehabilitate, and exalt the wretched, the degenerate, the vicious, and the criminal.

… So long as the sun

Shines upon human misfortunes,

The sheep will be eaten by the wolf [53]; the only thing left is for those who know and can, not to become sheep.

At the banquet of the Republican Committee of Commerce and Industry, held on June 22, 1900, Millerand opened with the usual phrases and declared himself moved by the mention made “of the efforts I have undertaken to bring about some progress in the path of social justice, where the Republic must always march forward, never stopping, and in the work of social reparation, which consists in leaning toward the most unfortunate and trying to bring them more [434] justice and well-being.” And then he tried to win over those bourgeois, speaking to them of alliance: “Our ministry has demonstrated the necessity of an alliance between the bourgeoisie and the workers, and we must be proud of it.” None of those present recalled the old fable:

Nunquam est fidelis cum potente societas ;

(Never is there loyalty in alliance with the powerful);

nor dared respond to the citizen, “comrade,” and minister: “When we have helped you defeat the nationalists, you will do as the lion in the fable and take everything:

Sic totam praedam sola improbitas abstulit .

(Thus did sheer greed carry off the entire prize).

“In fact, you’ve already begun. You call us allies and yet allow us to be robbed with impunity. To complete the work, your friend Jaurès, whom you’ve brought into the Office du travail (Labour Office), proposes that if the majority of workers wish to strike, the minority should be forced by public authority to comply, and the employer should be forbidden from hiring any of the striking workers or other outside laborers.” There were many industrialists present, and none dared utter a word. People so lacking in courage truly deserve no respect, and Millerand, thinking of them, might well have recalled the saying of Tiberius about another degenerate aristocracy: O homines ad servitutem paratos (O men fit for servitude).

It is pitiable to see how all parties now court and flatter the people. Even a man like Galliffet says, in the French Chamber, that he is a socialist! Everyone prostrates themselves before the new sovereign, and in his presence becomes cowardly [54].

[435]

In this ever-growing weakness of the bourgeoisie lies, in part, the origin of the new religious fervor that is invading that class, and thus also one of the many causes of the present religious crisis. It has often been said that when the devil grows old, he becomes a monk; just as a courtesan, when she ages, withdraws from vice and becomes a pious churchgoer. The case of our bourgeoisie is not entirely the same, for it has indeed become pious, but without withdrawing in the least from vice.

The humanitarian and sentimental feelings it flaunts are inflated, artificial, and false. Let it be granted that prostitutes, thieves, and murderers deserve compassion, but does the honest housewife, do respectable men, not deserve it as well? It is a fine and noble thing to sympathize with the sufferings of today’s poor and to try to alleviate them, but are the sufferings of tomorrow’s poor, that is, of the man who is well-off today and is to be plundered and reduced to poverty, of a different nature? In truth, today’s bourgeoisie does not look that far ahead; it exploits the present and lets the deluge come. Its sensitivity is expressed in words, and often conceals shameful profits. The weak are usually also cowardly, they commit theft [55] by sleight of hand, but do not dare resort to armed robbery.

Declining aristocracies are accustomed to display humanitarian sentiments and great kindness, but such kindness, when it is not simply weakness, is more apparent than real. Seneca was a perfect Stoic, but he had vast wealth, magnificent palaces, and countless slaves. The French nobles who applauded Rousseau knew how to extract heavy payments from their “tenants,” and their new love for virtue did not prevent them from squandering, in orgies with prostitutes, the money extorted from starving peasants. Today in France, a landowner has his fellow citizens pay him several thousand lire through tariffs on grain and livestock; he donates a hundred lire or so to a “People’s University,” and thus fattens his purse, quiets his conscience, and even hopes to win some popular election. Feeling pity for the poor and wretched amid luxury provides a pleasant titillation to the senses. How many [436] today are landowners but will be socialists in the future, thus feeding from two troughs. That future is so distant, who knows when it will come! In the meantime, it is sweet to enjoy one’s wealth and talk about equality, to curry friendships, win public office, sometimes even find good opportunities to profit, and to pay with words and promises for a time far off. There is always profit to be had by exchanging a sure good for promissory notes due at such a distant and uncertain date.

The sum improperly appropriated by the ruling class [56] through protective tariffs, subsidies for shipping and sugar and similar things, state-subsidized enterprises, syndicates, trusts, etc., is enormous, and certainly comparable to the amounts extorted by ruling classes in other times. The only advantage for the nation is that the method of shearing the sheep [57] has been refined, so that for the same amount of wealth extorted, the amount wasted is less. The feudal lord who plundered travelers hindered the growth of commerce, stole a few coins, and indirectly destroyed many more lire; his successor, who profits from protective tariffs, unjustly appropriates a greater amount of wealth while indirectly destroying less.

Our ruling class [58] is insatiable; as its power diminishes, its acts of malfeasance increase. Every day in France, Italy, Germany, and America, it demands new tariff hikes, new measures to protect shopkeepers, new commercial restrictions under the pretext of health regulations, new subsidies of every kind. In Italy, under Depretis, the government sent soldiers to harvest the fields of landowners who refused to pay the wages demanded by free harvesters—and now this fine practice is being renewed. It seems the feudal corvées are returning. Soldiers, instead of being used solely to defend the homeland, serve the landowning gentlemen to depress wages below what free competition would establish.

Such is the way our excellent “humanitarians” go about plundering the poor. Anti-tuberculosis congresses are admirable things, but better still would be not to steal the bread from the mouths of the starving; and it would be good either to be a little less “humanitarian,” or to have a little more respect for other people’s stuff.

There is not the slightest sign that the ruling class is about to turn from its evil path, and there is every reason to believe it will continue to [437] follow it until the day of final catastrophe. This was already seen in France with the old aristocracy. Even on the very eve of the Revolution, they besieged poor Louis XVI and begged him for money [59]. Today, in that country, socialism is spreading—and protectionism is rampant. In Italy, under Depretis, robbery and looting [60] were systematically orchestrated. From voter to elected official, everyone was buying and selling themselves. The tightening of protectionism in 1887 was a means of auctioning off and selling to the highest bidder the right to impose private taxes on citizens; others got to exploit railroads, banks, steelworks, the merchant marine. The entire ruling class crowded around the government, clamoring for at least a bone to gnaw on. At that time, the evil seed was sown that bore fruit in tears and blood in May 1898, and which may bear even more bitter fruit in the future. To the ruling class’s illicit appropriations corresponded the violence of the mob, repressed, not extinguished, by unjust repression. Unjust, I say, because it was not aimed at protecting order and [438] property, but at defending privilege, perpetuating robbery, and making possible such scandalous events as the Notarbartolo trial.

Let the reader note that when we speak of the waning strength of the ruling class, we do not in the least mean a waning of violence; on the contrary, it often happens that the weak are precisely the most violent. No one is more cruel and violent than the coward. Strength and violence [61] are entirely different things. Trajan was strong and not violent; Nero was violent and not strong.

If, as seems likely, the contrast between ever-growing misdeeds and ever-diminishing spirit, courage, and strength continues to sharpen, the end can only be a violent catastrophe that will restore the equilibrium so gravely disturbed.

The rise of a new aristocracy.↩

It is an illusion to believe that facing the ruling class today is the people. What stands against it, and this is something quite different, is a new and future aristocracy that relies on the people; and indeed, a few faint signs of tension already appear between this new aristocracy and the rest of the people, making it foreseeable that, as time goes on, we will witness events similar to those seen in Rome during the conflict between the aristocracy of the plebs and the rest, and in the Italian republics between the greater guilds and the lesser. [62] These latter conflicts resemble, at least in part, those now observed in England between the old Trade Unions and the new ones.

Everywhere, workers who hold lucrative trades try to exclude the rest of the population from them, strictly limiting the number of those allowed to learn the craft. Glassmakers, typographers, and workers in other such trades form closed castes [63]. Many strikes originate from the fact that unionized workers reject non-unionized ones. In short, we see the amorphous mass splitting into distinct layers, the upper ones forming the new aristocracy.

It is notable that, so far, the political leaders of this new aristocracy are almost all bourgeois, that is, taken from the old aristocracy, which has indeed decayed in character but not in intelligence. Also contributing to this is the bad behavior of our bourgeoisie, which drives the best part of itself into the ranks of the opposition, whatever that opposition may be, thus further weakening the ruling class, which bleeds out and loses its most [439] capable, moral, and honest men. When, as happens in Italy, an honest man is faced with the dilemma of either approving outright crimes, such as acts of malfeasance of the banks and the deeds revealed in the Notarbartolo trial, or siding with the socialists, he is driven irresistibly to the latter.

It seems likely that the current ratio between bourgeois and working-class leaders of the new aristocracy will change, and that the number of workers will increase, this is because the working class [64] is becoming ever more active, educated, and strong.

Already, by the early years of the 19th century, the present evolution could be foreseen. It is a most certain law for both living organisms and social organisms that there is a close relationship between the organs of nutrition and the general shape of the body [65]. No one will believe that a carnivore and a herbivore can have entirely similar forms, nor can one believe that warlike societies and industrial societies [66] should have the same social structures. Our societies are certainly much more industrial and less warlike than those of the previous century, and therefore their structure had to change. Where industry flourishes, the working class must, sooner or later, acquire great power. Just observe what happens in countries where political elections are held: if a city becomes industrial, it is almost certain to send socialist or at least radical deputies to parliament. In Italy, Milan, which once belonged to the “consorti”, and Turin, which was monarchist, now elect socialists, republicans, radicals, because industry has grown enormously in those cities. Florence, where it has grown much less, remains more faithful to the moderate party.

This general movement has been so often noted that it is unnecessary to dwell on it further; but another movement, which is also of great importance, has only recently been studied. I refer to the movement by which a portion of the working class begins to earn high wages, and thereby constitutes the first nucleus of the new aristocracy.

The principal origin of this phenomenon must be sought in the enormous increase in savings and capital. After 1870, there were no more great European wars that caused grave destruction of savings, and though its growth was hindered by [440] the waste brought on by state socialism, protectionism, and other acts of malfeasance by the ruling class, these causes could not prevent a substantial increase in the total amount. Therefore, as the ratio between capital and labor shifted, the former became less valuable, the latter more valuable. Wherever technically possible, machines replace human physical strength, and this can be done economically precisely because capital is not lacking among civilized people. Among others, the transformation, though technically possible, is often not economically feasible, and human labor plays a greater role in physical labour. Where capital is abundant, men are pushed toward the types of labor in which machines cannot compete with them, that is, work that requires sense and intelligence. Moreover, there is an incentive to be rigorously selective and to offer high wages to obtain men of uncommon intellectual strength to operate the machines. For a ditch-digger, two strong arms are sufficient, and if there is a Hercules as strong as two average men, he can be paid double, but not more, since the work could just as well be done by two others. But to operate a locomotive, one needs a man with intelligence and judgment, and if he were slightly deficient in those, one could not remedy the situation by placing two engineers on the locomotive instead of one. Two, three, or even four mediocre machinists do not perform the work of a single skilled and intelligent one. Ten ignorant chemists are worth nothing compared to a single good one in a chemical plant. Here then is a most powerful force, operating constantly, dividing workers into various classes, assigning great advantages to the upper ones, and thereby becoming a principal cause in the formation of a new aristocracy.

The state socialists, who want to squander capital, pay no attention to this and do not realize that they are, unwittingly, helping the old aristocracy by obstructing the rise of the new one, which takes firm shape only where capital is abundant. The Marxists have a truer understanding of the phenomenon, and if not scientifically, at least instinctively, they have grasped that their victory can only occur if it is prepared by the abundance of capital, or, as they say, socialist evolution must pass through a “capitalist” phase.

[441]

Another rigorous selection, which also contributes to the formation of the new aristocracy, is carried out by workers’ unions and syndicates. This phenomenon can be considered a consequence of the former, since those unions and syndicates are only possible and thrive where the abundance of capital has allowed large industry to arise and prosper. In the beginning, there is always the abundance of savings and capital. However, let us not forget that, while this appears to be and indeed is in part a cause of the phenomenon, it is also, in part, an effect, since the development of industry and the formation of the new working-class aristocracy [67] help to increase the total savings and capital.

Paul de Rousiers has admirably noted the characteristics of the evolution of workers in England, and if these are carefully studied, it becomes clear that they are also those of the formation of the new aristocracy. Speaking of the leaders of the Trade Unions, he says: “The first quality one notices in them is a practical, clear, and precise mind, a sense of what is possible, firm good sense leading to effective effort” [68]. Exactly the qualities that are lacking in the dying old aristocracy.

“Even those who believe in the necessity of a profound upheaval in society and are drawn to the most advanced socialist theories retain in their minds an ideal dream, but apply themselves in practice to obtaining specific results… Moreover, many of them confine themselves entirely to the pursuit of advantages that in no way require a remaking of social institutions.”

They speak as strong men and do not possess the flabby humanitarian sentiments of our bourgeoisie; they say that one cannot

“improve the condition of the weak unless they themselves struggle against their own weakness… a vigorous conscience is needed, a virile sense of their moral responsibility… Practical spirit, moral elevation, intellectual culture—these are the three main qualities that ensure the success of the trade union leaders” [69].

Are these not precisely the qualities that distinguish the aristocracy (understood etymologically as “the best”) from the rest of men? [70]

After the generals come the captains, the sergeants, the soldiers, and all are men who have been selected. [71] Strictly speaking, [442] there is never just one aristocratic class [72], there are various stratified classes that constitute the aristocracy. [73]

“One must go down to the ordinary personnel, to the simple workers, to see the profound causes to which a union owes its success. It is above all their regularity in paying weekly dues that produces financial prosperity, the indispensable material foundation. The workers who join unions in England make a serious commitment and fulfill it with punctuality. After a few weeks, the delinquent member is simply struck from the rolls—unless, of course, he is receiving aid due to unemployment, accident, illness, etc.” And where does he go? He falls into a new proletariat, now forming alongside the new aristocracy, and it is there that the children of today’s bourgeoisie will likely end up, once they have been plundered by the new aristocracy. “I insist on this material fact of the regularity of dues payments,” says de Rousiers again, “because in addition to the financial power it ensures the unions, it marks the quality of the men who compose them. We will often have occasion to observe this: union personnel is the result of selection: The best men belong to the Union. These men, voluntarily grouped for a goal they understand… are the true basis of success” [74]. How else can one describe the formation of an aristocracy?

Italian socialists have often said that where their doctrine spreads, workers become more moral, more honest, less violent, they no longer beat their wives, otherwise they are excluded; they educate themselves instead of getting drunk at taverns. All this is true, except that, for the most part, they do not become such; rather, they are selected that way, and that is quite a different matter. No one denies that a man can change his habits, but by now, everyone knows that is the exception. The rule is that, while a species can slowly, very slowly, change, the individual changes very little. To have a good mathematician, one must choose him; you can’t really turn just any fool into one with a good education. Who is capable of turning a cowardly man into a courageous one, a promiscuous woman into a chaste matron, a careless man into a prudent one?

[443]

This is not to say that socialists do not increase the number of good and virtuous workers; they do increase that number because they provide those workers who already are such with the means to emerge and prove themselves. Let us even grant, being very generous, that they radically transform a few: still, a residue remains of people lacking in character, honesty, morality, and intelligence, and this group will form the new proletariat.