Yves Guyot, Where and Why Public Ownership has failed (1914)

|

|

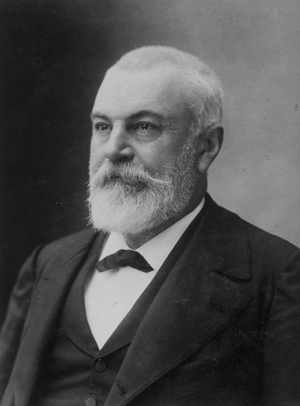

| Yves Guyot (1843-1928) |

Source

Yves Guyot, Where and Why Public Ownership has failed. Translated from the French by H.F. Baker (New York: The Macmillan Company, 1914).

See the facs. PDF.

Also the French original, La Gestion par l’État et les Municipalités (Felix Alcan, 1913) in HTML and facs, PDF.

Table of Contents

BOOK I PUBLIC AND PRIVATE TRADING OPERATIONS

- CHAPTER I TWO PRECEPTS

- CHAPTER II THE THREE MAINSPRINGS OF HUMAN ACTION

- CHAPTER III DETERMINING MOTIVES OF PRIVATE AS AGAINST PUBLIC ENTERPRISES

- CHAPTER IV GOVERNMENT AND MUNICIPAL TRADING OPERATIONS

BOOK II FINANCIAL RESULTS OF GOVERNMENT AND MUNICIPAL OWNERSHIP

- CHAPTER I BOOKKEEPING IN STATE AND MUNICIPAL TRADING ENTERPRISES

- CHAPTER II THE BELGIAN STATE RAILROADS

- CHAPTER III PRUSSIAN RAILROADS

- CHAPTER IV STATE RAILWAYS OF AUSTRIA AND HUNGARY

- CHAPTER V ITALIAN RAILWAYS

- CHAPTER VI THE RAILWAYS OF THE SWISS FEDERATION.

- CHAPTER VII RAILWAYS OF NEW ZEALAND

- CHAPTER VIII GOVERNMENT RAILROADS IN FRANCE

- CHAPTER IX PUBLIC VS. PRIVATE OPERATION

- CHAPTER X THE HOLY CITIES OF MUNICIPAL OPERATION

- CHAPTER XI OPERATION OF GAS AND ELECTRICITY IN THE UNITED KINGDOM

- CHAPTER XII TRAMWAYS IN GREAT BRITAIN

- CHAPTER XIII HOUSING OF THE WORKING CLASSES AND PUBLIC OWNERSHIP IN GREAT BRITAIN

- CHAPTER XIV HOUSING OF THE WORKING CLASSES ON THE CONTINENT

- CHAPTER XV GOVERNMENT CONTROL OF FOOD SUPPLIES

- CHAPTER XVI VICTIMS OF GOVERNMENT OWNERSHIP

- CHAPTER XVII CHARGES, DEBTS AND CREDIT

- CHAPTER XVIII FICTITIOUS PROFITS

- CHAPTER XIX FISCAL MONOPOLIES

- CHAPTER XX THE ALCOHOL MONOPOLY IN SWITZERLAND AND RUSSIA

- CHAPTER XXI FINANCIAL DISORDER

- CHAPTER XXII THE PURCHASE PRICE

- CHAPTER XXIII DELUSIONS OF PROFIT AND THE LIFE INSURANCE MONOPOLY IN ITALY

- CHAPTER XXIV THE FISCAL MINES OF THE SAAR DISTRICT

- CHAPTER XXV PUBLIC VERSUS PRIVATE ENTERPRISE

BOOK III ADMINISTRATIVE RESULTS

- CHAPTER I ADMINISTRATIVE RESULTS

- CHAPTER II THE SAFETY OF TRAVELERS UPON STATE AND PRIVATE RAILWAY LINES

- CHAPTER III DISORDERS, DELAYS AND ERRORS

- CHAPTER IV OFFICIAL CONSERVATISM

- CHAPTER V LABOR

- CHAPTER VI THE CONSUMER

- CHAPTER VII PROGRAMS OF ORGANIZATION AND REGULATION

BOOK IV POLITICAL AND SOCIAL CONSEQUENCES OF PUBLIC OPERATION

- CHAPTER I SOCIALIST PROGRAMS AND THE FACTS

- CHAPTER II BLUFF

- CHAPTER III RESULTS OF EXPERIENCE

- CHAPTER IV THE STATE A DISHONEST MAN

- CHAPTER V CORRUPTION

- CHAPTER VI NATIONALIZATION OF PUBLIC UTILITIES AND THE FOUNDATION OF GREAT FORTUNES

- CHAPTER VII DISINTEGRATING CHARACTER OF PUBLIC OPERATION

- APPENDIX "A" ALCOHOLISM IN RUSSIA

- APPENDIX "B" THE FINANCIAL YEAR IN AUSTRALIA

- APPENDIX "C" THE SHORTCOMINGS OF THE TELEPHONE IN ENGLAND

PREFACE↩

The chief difficulty in preparing this book has been to make a coherent arrangement of the material, as the various sources from which it has been gathered are more or less incomplete. Indeed the obstacles in the way of presenting a true picture of industrial enterprises, as operated by states and local governments, can scarcely be exaggerated.

The partisans of government and municipal ownership of every species of public utility have assumed a distinctive title. They call themselves representatives of the movement for direct operation (Représentants de la Régie Directe). Their leader in France is Edgard Milhaud, occupying the chair of Political Economy at the University of Geneva, where he makes a special point of emphasizing Socialism.1 In a little periodical, entitled Annales de la Régie Directe, he presents the case for all government and municipal undertakings, although his enthusiasm frequently receives cruel setbacks, as in the suicide of the Mayor of Elbeuf. He has also published several articles for the purpose of demonstrating that accidents are much less frequent upon government railways than upon the lines of private companies. We shall see later (Book 3, Chapter [vi] 2) the value of these attempts to justify his creed, and we may judge from them the importance that is to be attached to his other statements.

For the academic year 1911–1912, L'École des Hautes Études Sociales organized a series of conferences on the subject of public operation under the direction of M. Milhaud. It was considered advisable that at the close of this series a dissenting voice should be heard—a rôle ultimately assigned to me. In addition to ten preceding lectures, wherein the whole theory and practice of Socialism had been set forth, M. Milhaud was to speak for forty minutes, after which I was to be allotted forty in which to refute the points previously developed by him during 640 minutes. Then we were both to be allowed twenty minutes in order to sum up our arguments. I had at least the satisfaction of knowing that L'Humanité2 attached sufficient importance to this conference to announce that for several days before it was to take place entrance tickets would be reserved for "comrades"; under which conditions it was not difficult to foresee that the hall would be converted into a public assembly room.

His audience, thus prepared and won over, naturally gave M. Milhaud an enthusiastic welcome. However, despite some murmurs, it proved itself not unwilling to allow me to oppose my facts to his statements.

I borrow from the report of the discussion, as published in L'Humanité, November 14, 1911, the following résumé of the argument of M. Milhaud:

[vii]"Private monopoly, seeking nothing but maximum profit, is far more costly than public monopoly, which is not bound by the same conditions. Money costs public enterprises less, and, therefore, they can amortize their debt and thus reduce general expenses. On the other hand, heavier expenses for labor can be supported by public undertakings. The management of a public enterprise can even hope for profit, and all this can be accomplished within less rigid limits than those which necessarily confine private monopoly.

Milhaud concluded by outlining the tendency of public enterprises to become administrative autonomies. In order that they may escape pernicious bureaucratic influences, they are being transformed into separate commercial entities. Through increased control by the consumer, on the one hand, and by labor on the other, they are being gradually but completely socialized.

Through reduction in prices, these enterprises create larger bodies of consumers, and they also bring about more flexible relations between employers and employed. The representatives of collectivism, individual consumers and producers, may thus unite in behalf of social progress."

When we come to examine the assertions of the propagandists of public operation, we perceive that they are of no better quality than any other Socialist theories; but the assured manner with which these statements are declared succeeds in disturbing and intimidating many people. Yet, in the elections of 1910, Paul Forsans, President of La Société des Intérêts Économiques, was able to organize a vigorous campaign against an alcohol and insurance monopoly.

French Socialists, unable to appeal to the experience [viii] of the Western (state) railroad, or the experience of the town of Elbeuf, say: "Very good, but in Prussia the state railways are altogether satisfactory, and, in all the important cities of Great Britain, Municipal Socialism is enjoying a veritable triumph."

Such partisans quote the testimony of public departments, never weary of boasting of their own successful administration, and of municipalities which, inspired by local pride, declare that they have accomplished miracles. But how can we accept these prejudiced certificates of good conduct until we have been privileged to make a detailed inventory?

There is a crying need at the present time for collections of precise facts, which shall show the vanity and "bluff" of Socialist programs, and such facts must be placed before the public. My sole object in writing this book has been to present just such a compilation of rigidly investigated, authentic facts and figures regarding public ownership and operation. If I have not been able to affirm that government and municipal undertakings are efficient the fault is not mine. I have not found them so.

A well-known American, Arthur Hadley, President of Yale University, says, in his book entitled Economics:

"The advantages of intervention on the part of a government are visible and tangible facts: The evil that results from such intervention is much more indirect and can only be appreciated after close and intensive study."

I have vainly sought for the benefit arising from public operation by states and municipalities. On the [ix] contrary an unbiassed survey of the whole subject forces me to testify to the resulting harm.

Y. G.

November, 1912.

For the American edition the facts and figures herein set forth have been brought up to date—June, 1913.

Footnotes for Preface

1. See La Démocratie Socialiste Allemande, Paris, F. Alcan.

2. The organ of the Socialist propaganda.

[1] [x]TRANSLATOR'S NOTE↩

The translation has been read and revised by the Author. Otherwise my hearty thanks for most valuable assistance given in translation are due to Miss Elise Warren and Mr. William D. Kerr.

[v]

BOOK I

PUBLIC AND PRIVATE TRADING OPERATIONS

CHAPTER I

TWO PRECEPTS↩

Neither national nor local governments should attempt that which can be done by individuals: says the economist.

Labor for personal profit must be replaced by labor for the sake of service: answers the Socialist.

Experiments in the way of nationalization and municipalization of public utilities, with the Socialist ideal in view, have been sufficiently numerous. Do they warrant the decision that nations and municipalities have reaped the advantages promised by their advocates? This question—primarily a psychological one—we are going to try and answer in the following pages.

[2]CHAPTER II

THE THREE MAINSPRINGS OF HUMAN ACTION↩

- 1. Compulsion.—Bribery.—Instinct for Personal Gain.—Government and Municipal Ownership Would Substitute the First Two Influences for the Third.

- 2. No Dividends on Capital of Public Undertakings.—Interest and Amortization.—The Altruism of Disinterested Managing Boards.—Work for the Sake of Service.

1. Down to the present time there have been only three mainsprings of human action—compulsion, bribery and instinct for personal gain.

Compulsion is the true basis of confiscation and slave labor. Give or I take. Work or I strike.

Bribery, in the way of high office, rewards, decorations, rank and homage, helps to blind us to the presence of compulsion. The church, the schools, and the army furnish the best and most familiar examples of the effect of these two forces, which government and municipal ownership would substitute for the incentive of personal gain.

Neither compulsion nor bribery, however, has proved quite sufficient to induce continuous action on the part of employees and officials entrusted with the operation of national and municipal services, for they are utterly incompatible with any form of contract. The very nature of a contract requires free assent to [3] its terms on both sides. Therefore, the third force, the instinct for personal gain, is invoked.

Personal gain does imply a preliminary agreement—assent on the part of him who offers his services as well as of him who is to pay for them. Every group of employees at the present day is working, not for the sake of service, but for gain.

2. Is the management of a national or municipal undertaking more economical than the management of a private enterprise? "Yes," answers the Socialist, "because no dividend need be paid on capital."

But there are interest and amortization to provide for on capital. Consequently the margin of economy is only the difference between interest and amortization, which public undertakings must provide, and dividends which the capital of private enterprises must have.

"The high-salaried employees are paid less by public than by private enterprises: and there are no boards of financially interested directors," continues the Socialist.

This is possible, but the salaries of ministers, burgomasters and mayors are high; though these high salaries come from the exercise of several different functions. It is probable that high-salaried government employees are paid less than their colleagues of the same relative rank in the employ of private industry; but, in general, the personnel of public undertakings is more numerous and the expenses, therefore, amount to more in the long run. The management of the Western (government) [4] railway, of France, for example, has established sixteen directorships in place of the three departmental divisions customary in the case of private railways. There are no financially interested boards of directors, but it is a question whether the altruism of the councils which direct and control national or municipal undertakings is of greater advantage to these enterprises than personal interest would be.

In effect the partisans of public operation find economy in the non-remuneration of capital, outside of interest and amortization, and in the meager remuneration of promoters, directors, councillors, and the chief managers of the enterprise.

[5]CHAPTER III

DETERMINING MOTIVES OF PRIVATE AS AGAINST PUBLIC ENTERPRISES↩

- 1. Why Do Individuals Establish an Undertaking?

- 2. The Motives of Politicians.—Sacrifice of the Service to Personal Ends.—The Roof of the Louvre.—The Department of Fine Arts (Beaux Arts).

- 3. The Freycinet Program.

- 4. Municipal Interests.—Public Officials.

- 5. Invidia Democratica—Appeal to Party Passions.—Purchase of the Railways.—The Purchase of the Western Line.—Socialization a Political Necessity.

- 6. Financial Aims and Hypocritical Excuses.—Pretexts and Realities.—The Alcohol Monopoly in Switzerland and Potatoes.—The Alcohol Monopoly in Russia, Temperance and Fiscal Laws.

1. When one or more individuals invest their energy, their knowledge, and their capital in an industrial enterprise they must be convinced beforehand that in so doing they are responding to a demand on the part of a group of consumers having a sufficient purchasing power to repay them for their services, as well as for the products which will be offered.

If the estimates of the founders of such an enterprise are correct, they will gain; if incorrect, they will lose. In either case they will bear the responsibility for their acts. Gain or loss is the inevitable [6] and infallible consequence of every such enterprise. And, as every man who is on the point of engaging in business knows that one of them must occur, his energy is spurred on by the hope of the one, while at the same time it is being curbed by the fear of the other.

The industrial and commercial progress of all nations far advanced along the pathway of evolution proves that the majority of those individuals or groups of individuals who have engaged in business undertakings have calculated accurately.

2. Statesmen at the head of nations or municipalities are not necessarily responsive to the conditions just described. The undertakings in which they involve the state or the municipality will not yield them any personal profit in case they succeed, nor will they be called upon to suffer any loss if they fail. The inevitable and infallible criterion of the business man is lacking in their case. By what test, then, are their motives to be construed?

As a rule their action is determined by the amount of personal advantage resulting for themselves; not, it is true, in the form of gain, but in the form of an increase in the duration or extent of their power. They establish such or such an enterprise, because, in looking about for some bait likely to attract the public, they have found this particular one. Does the enterprise fill a long-felt want? That is a secondary question. The first consideration is what will make the broadest appeal to the popular prejudices and sympathies of the moment. I have heard ministers and [7] deputies say: "There is nothing to do, but we must do something."

Now expenditures which have a certain audacity about them are sure to be accepted with a much better grace than those which do not appeal to the imagination of the public.

As an instance in point, let me quote from my own experience.

When I became minister of Public Works I speedily discovered that the government buildings under the jurisdiction of my department were being very badly kept up by the department of fine arts (Beaux Arts). Knowing by personal experience the importance of roofs I turned my attention first to them. In the case of the Louvre, to quote but a single example, the water leaking through the roofs was cracking the walls. Moreover, not one of the seventeen lightning rods attached to the building was in working condition, while the majority of them were so insecure that they were liable to fall at any moment on the heads of passers-by. I used the entire appropriation at my disposal to insure an efficient roofing of the buildings entrusted to my care. The rest could wait.

But, from the point of view of popularity, I had made, as I had foreseen, a wretched move. That form of flattery which consists in the sacrifice of one's own to public opinion forms part of the very stock in trade of the politician; and, if he is shrewd, he will not hesitate to make the sacrifice.

Again, in 1902 the French Parliament passed a law on public hygiene, under which municipalities are required to furnish drinking water and sewerage systems. [8] A number of deputies and senators who had voted for the bill hastened immediately to the minister of the interior to demand that the law should not be applied to the municipalities in their particular districts. And so it goes.

The following illustrates a different but equally dangerous tendency:

Certain officials of the Beaux Arts are provided with funds for the purpose of placing orders or for the purchasing of works of art at the salons. These men are beset by recommendations and advice of all sorts. Concentration of their appropriations upon one important work is out of the question; they must fritter them away in small amounts, because there are so many people to satisfy. In all purchases of art works there is, of course, a large proportion of mistakes, which will be accounted in the future as dead losses; but it is not necessary to begin by buying failures, as so frequently happens.

Nor does this criticism refer solely to contemporary officials. Ministers and under-secretaries of state of other periods than our own were equally human. Side by side with the Thomi Thierry art collection in the Louvre are to be found government purchases of works by the same artists, made at the same time. The degree of taste shown in the choice of the pictures included in the Thierry collection is far superior to that shown in the official collection.

3. In 1879 Charles de Freycinet prepared his grand program of public works. There is no more agreeable pastime than to prepare a program of public works. [9] Hope is inspired, delusions encouraged, and we can leave to our successors the trouble of realizing them. All succeeding ministers of Public Works have been liquidators of the Freycinet program. The spirit which dictated it struck the public imagination. "The government," it was said, with the hearty applause of the French Parliament, "must assume charge of the national savings." As if there were any savings except those of individuals, and as if those who had known how to accumulate them would not be more careful to use them to good purpose than those who had had no interest in their acquisition! All the deputies and senators demanded a share of the cake for their constituents. M. de Freycinet yielded everything, encouraged still further demands, and requested engineers to submit plans for railways, canals, or ports. The government concentrated all its energies on carrying out his program.

In 1883, however, and as a result of all this, the nation would have been bankrupt if M. Raynal had not closed certain contracts with the railway companies; contracts which Camille Pelletan later described as infamous. But he has never explained what the government would have done if the contracts had not been signed.

4. A so-called movement of public opinion frequently rewards intensive study. Any day you may be suddenly aroused to the consciousness that there is a movement on foot in favor of a certain public undertaking. On the side you are informed that so and so and so and so (local politicians) have made large [10] speculations in view of precisely this project. The municipality, for its part, may placidly obey the hidden impulse. If not, the parties interested proceed to take a more or less direct part in the struggle. In any event the simple, hoodwinked people become very enthusiastic for or against the issue.

In 1902 the City of Birmingham decided to submit a bill to Parliament which would permit it to take over and operate its urban tramway system. A referendum vote was taken. Out of 102,712 registered electors, only 15,742, or 15 per cent. of the total electorate, voted. Moreover, according to the Daily News, "high officials of the town led gangs of municipal workmen to the polls."1 Major Leonard Darwin says in this connection:

"The more energetic and able they (the officials) are, the more likely will they be to view with favor new projects connected with municipal trade."2 In the end, perhaps, such an extension of the official functions will mean more work for such enthusiasts. But their influence will probably be greater, and conceivably even doubled, through the resulting increase in their financial importance.

5. The promotors and leaders of movements in the direction of government and municipal ownership frequently resort to exciting and exploiting the so-called invidia democratica, or democratic jealousy, one of the plagues of the Roman Republic, and always [???] [11] evidence in an individualistic state. Men who are at the head of private enterprises are denounced as exploiting their fellow-citizens. Their profits—usually exaggerated—are quoted, and the claim is made that such moneys will be restored to the people when governments, local or national, provide everything and individuals nothing.

Was the object of the purchase of the Western railway in France economy in expenditure and improvement in transportation facilities? Not one of those who demanded and voted for it dared to make such a claim. With the lines belonging to the state the deputies would have places for their constituents, a certain right of political interference in the administration, and hence a large degree of electoral influence. Resolutions favoring the purchase of the Western railway had been rife since 1902, but no minister of Public Works had endorsed them. Immediately after the elections of 1906, however, Georges Clemenceau, then Minister of the Interior, started on a hunt for a program which would be Socialist without being collectivist. Socialism is the present phase of the movement; collectivism is the Socialist's dream.

Clemenceau took from his predecessors: 1. Noonday rest. 2. Limitation of working hours and a collective labor contract. 3. The income tax. 4. Labor pensions.

But he was also anxious, by socializing something, to conciliate the Socialists and the Radical Socialists. He therefore selected the purchase of the Western railway as suited to his purpose. Then, in order to be certain that the affair would go through, he implicated [12] Louis Barthou in the affair, in the latter's capacity of minister of Public Works, although Barthou's antecedents did not point to him as especially fitted to carry out such a measure.

6. One of the chief incentives to the establishment of a government monopoly is the hope of procuring resources without the stigma of an apparent fiscal object attached. It is one way of making the taxpayers pay taxes without perceiving that they are taxes. As a matter of fact they are simply misrepresented taxes. Appeals of their promoters to the moral and hygienic interests of the nation, in order to effect the desired object, are equally disingenuous.

For example, the alcohol monopoly in Switzerland was submitted to the people as designed to combat alcoholism, while putting an end to the ohmgeld duties, a sort of internal revenue duty. As for alcoholism, the financial history of the individual cantons, which have been receiving their share of the profits of the monopoly for the purpose of fighting it, proves just how relative has been the attention devoted to the eradication of that particular evil.

But there was still another motive, although it has been mentioned only in conversation. In Switzerland every quart of alcohol is produced from potatoes. Growers found that the distillers were buying their potatoes too cheaply. Therefore, at the opportune moment, the Federal government increased the purchase price of domestic alcohol, saying to the potato grower: "You see, we have increased the price of alcohol. Whereas, in Austria, alcohol costs 20 or 30 [13] francs, we in Switzerland pay more than 80 francs for it; and we are doing so in order that you can sell your potatoes at a good price. In other words we are granting you a subsidy."

When the monopoly of alcohol was established in Russia it was repeated in every key that the object in view was moral and not financial. It was established, in the first place, in order to ensure to the moujik (peasant) absolutely pure alcohol. Emphasis was placed on the characteristic retail shops of the government, kept by officials who can have no interest in increasing consumption. There is neither chair, corkscrew, nor glass in the shop; therefore, the moujik, after buying, must go elsewhere to drink.

But, in 1912, the receipts from the monopoly on alcohol were estimated at 763,990,000 roubles, out of a total income of 2,896,000,000 roubles, or 26 per cent. It is, therefore, easily surmised that officials charged with the sale of alcohol would be held to a strict account if devotion to the temperance cause should happen to bring about a deficit in the budget. The moral aspect of the monopoly is completely effaced by fiscal interest.

M. Augugneur heads a local and national ownership party. Why should he advocate public ownership? Simply in order to have a platform—a reason for party existence. The future of municipal or government undertakings is a secondary matter. What is necessary is an issue which will lead to political action and to immediate power.

If any enterprise inaugurated by a mayor or by a [14] minister is difficult and useless neither the mayor, the minister, the municipal councillors, the deputies, nor the senators who have brought it into being will be called upon to bear any material responsibility for it. The taxpayers of to-day and to-morrow must assume the entire burden. Sometimes the failure of an undertaking involves a decrease in the influence of the politicians who were its promoters. But frequently it increases their importance in the public eye.

The risks which the Freycinet program carried with it; the uselessness of a quantity of the work included in it; the burdens which have accrued from the operation of railroads; an excess of 30 per cent. in the construction of navigable ways which are not yet finished, all this has in no way injured the prestige of the author of that program. The advocates of the purchase of the Western line are coping cheerfully with the deceptions it has engendered, and they imagine—and rightly—that no one, or almost no one, has ever placed in parallel columns their promises and the actual facts.

Again, had M. Barthou conducted a private business after the fashion in which he carried through the purchase of the Western road, he would long since have been branded as a defrauding bankrupt. As a public official the state has rewarded him for his efforts in this direction with the premiership of France.

CONCLUSIONS.

1. Any private undertaking has a definite objective point—gain; and a certain test—gain or loss.

[15]2. The motive behind municipal and national undertakings is usually political or administrative influence for their promoters.

3. The promoters of public undertakings escape all material and—generally—all moral penalty.

Footnotes for Chapter III

1. Raymond Boverat, Le Socialisme Municipal en Angleterre et ses Résultats Financiers, p. 444.

2. Municipal Trade.

[16]CHAPTER IV

GOVERNMENT AND MUNICIPAL TRADING OPERATIONS↩

- 1. The Report of Gustave Schelle to the International Statistical Institute.—List of Public Industrial Operations.—Postal, Telegraph and Telephone Systems.—Mints.

- 2. Public Trading Enterprises of Denmark, Switzerland, Holland, Italy, France, Belgium, Sweden, Austria, Germany.

- 3. The United Kingdom and the United States.

- 4. The London County Council.

- 5. The Municipal Activity of Russia.

- 6. New Zealand.—Government Socialism More Fully Developed Than in Any Other Country.—Socialist Enterprises.

- 7. Nationalization of the Soil in New Zealand.

- 8. Government and Municipal Trading Operations Restricted in Scope.

1. When zealots in the cause of "a transference of trading and commercial undertakings to public bodies" declare that it is a general and irresistible movement, they are mistaking their hopes for an accomplished fact. Public trading enterprises in actual existence are relatively few.

During the session of the International Statistical Institute of 1909, at the suggestion of MM. Arthur Raffalovich and Gustave Schelle, a committee was [17] appointed for the purpose of collecting statistics regarding state and municipal trading undertakings. The members of this committee were: Yves Guyot, chairman; Gustave Schelle, secretary, and MM. Colson, Raffalovich, Fellner, Nicolai and Hennequin. The report of this committee was presented to the session of the International Statistical Institute which met at The Hague in 1911.

The industries monopolized by nations or cities appear in the report as follows: The postal systems in every country and telegraphs and telephones in every country except the United States. All governments coin money, either free, as in England, or for a slight charge. In the following summary we will not speak of these four utilities unless they present some special characteristic peculiar to the country under consideration.

2. The report begins with Denmark. It is generally known that this country is very active and very highly developed industrially. Its population, however, is smaller than that of the city of Paris.

Denmark operates, in connection with its army, twenty public enterprises, employing altogether 2,335 people. The railway system comprehends 37 enterprises, employing 4,797 people. In addition to these there are 16 other enterprises, employing 279 people, and including a dressmaking establishment and a workshop attached to the royal theater.

The total number of these enterprises is thus 73, employing 7,411 people, of whom 7,166 are laborers. But the majority of Danish state undertakings are [18] only semi-public in character. The principal object of the factory at Usseröd is the manufacture of cloth for the Army and Navy, but it has a retail shop for the benefit of the public. The powder mill of Frederiksvärk has a monopoly of the manufacture of powder. The three ports of Helsingör, Frederikshavn, and Esbjerg are the three great ports of the state. The royal manufacture of porcelain is not counted among government industries.

As for the towns the census of 1906 gives 43 water works, 1 street paving enterprise, 2 embankment enterprises, 1 dredging undertaking, 2 construction undertakings with 29 workmen, 1 shipyard, 1 combined gas and water plant, 2 moulding undertakings, 1 installation of electrical apparatus, 8 plants for the production and distribution of electricity, 60 gas works, 2 wrecking enterprises, and, finally, 1 chimney sweep and 1 machinist, each of whom is considered as a municipal enterprise. The total is 126 enterprises, employing 2,274 people, or an average of 18 persons each.

In Switzerland the state alcohol monopoly buys potato spirit and sells it again. It does not manufacture it. The state both owns and operates its railways.

In Holland the state publishes an official journal and operates the Wilhelmina and Emma pit coal mines. The government railways are operated for the state by a private company.

For Italy, Giovanni Giolitti, then minister of the Interior, had already furnished statistics of the [19] principal municipal trading undertakings up to 1901, in a report presented to the Chamber of Deputies, March 11, 1902. The report lists 171 slaughter houses, 151 water works and artesian wells, 24 plants for the production of electrical energy, 20 public laundries, 15 gas works, 12 undertaking enterprises, 12 public baths, 4 ice plants, 3 sewage disposal plants, 3 irrigation enterprises, 2 bakeries, 2 pharmacies, and a few other less important services. The railways are state-owned and operated.

The law of March 29, 1903, enumerates 19 enterprises which municipalities may undertake. Outside of the usual services, water, gas, electricity, etc., we might mention pharmacies, mills and bakeries, as "normal regulators" of prices, ice plants, public bill posting, drying rooms and store houses for corn, the sale of grain, seeds, plants, vines and other arboreal and fruit-bearing plants.

The same law has determined the manner in which local governments may purchase concessions previously granted to private interests. They must pay to the owners an equitable indemnity, and account must be taken (a) of the market value of the construction and of the movable and immovable equipment; (b) of the advances or subsidies made by the local government; the registration taxes paid by the concessionaires; and the tax that the companies were able to pay to the towns on excess business; (c) of the profit lost to the concessionaires through the purchase, based on the legal interest rate for the number of years which the franchises have still to run, with annual sums equal to [20] the average profits of the five years last passed (not including interest on capital).

The law of April 4, 1912, established a life insurance monopoly.

The report of the Congress of the Federation of Municipal Enterprises, held at Verona, May 21 and 22, 1910, enumerates 74 special public enterprises, 31 of which were in existence before the law of 1903. This would tend to prove that the law had not aided greatly in their further development.

France has: 1. Fiscal monopolies, such as matches, tobacco and powder. 2. Postal system. 3. Government railways, comprising the system bought before the Western line; the Western railway; and the railway from Saint Georges de Commiers to La Mure, in the district of Isère, the operation of which constitutes a distinct department aside from that of the other government railways. Little is known concerning this third system.

Other enterprises are: the National Printing Office; the official journal (Journal Officiel); the manufacture of metals and coins; the manufacture of Sèvres porcelain; the manufacture of Gobelin tapestry; the manufacture of Beauvais tapestry; the water works of Versailles and de Marly; stock farms; and the baths of Aix-les-Bains.

The City of Paris has organized several commercial ventures. In 1890 a municipal department of electricity was installed, which was abandoned in 1907. The city has also taken full control, since June 1, 1910, [21] of the Belleville cable railroad. In 1905 it municipalized the undertaking service, and it operates a stone quarry for the benefit of the city streets. These are the only directly managed undertakings of the City of Paris. A mistake was made in becoming a shareholder in a gas company. In the case of water the city has undertaken to construct and maintain pumping stations and also mains, but it has granted to a private company the right to construct branch pipe connections, to receive subscriptions and to collect rents.

The Municipal Council of Paris has leased its electrical supply down to 1940 and also its transportation facilities, both surface and underground.

Belgium owns and operates nearly all its railways. It runs steamers from Ostend to Dover, and on the canal from Anvers to the port of Flanders.

In Sweden the state owns and operates the railways.

In Austria, according to a work compiled under the supervision of J. G. Grüber, by Doctor Rudolph Riemer, secretary of the Central Bureau of Statistics, outside of the customary monopolies the state controls fiscal monopolies, such as tobacco, salt, powder, lotteries, railways, a national printing office, an official journal, docks, stock farms, forests, and other public lands and mines.

Municipalities which M. Schelle has not listed operate gas and electric plants, undertaking services, baths, pawnshops, horticultural establishments, slaughter [22] houses, savings banks, theaters, docks, hydro-electric works, race tracks, tramways, and daily newspapers.

In regard to Germany M. Schelle had received no information concerning the German railways, nor the fiscal mines of Prussia. The government operates coal mines in upper Silesia, the districts of Deister and Oberkirchen, in Westphalia, and in the district of La Saar. These mines were employing 91,671 workers in 1910.1

The Prussian government also produces lignite, amber, iron ore and other ores, both calcareous and gypsum, potash, rock salt and refined salt, and operates blast furnaces and foundries of metals other than iron. These various industries employ 12,759 workers, which makes for the two classes enumerated a total of 104,430 persons employed. The state also operates the Prussian bank.2

3. The report does not take up the public undertakings of the United Kingdom, or of the United States. The results of the investigation made by The National Civic Federation of America, for the purpose of discovering whether the attempts at municipalization made in Great Britain ought to be imitated in the United States, were published in 1907 (3 volumes). However, the information given is most incomplete.

In Great Britain the telephone was not taken over [23] by the state until 1912. In the United States the telegraph and telephone are still under private management.

The Postmaster-General of the United States, in his report of 1912, recommended the annexation of the telegraph service. But President Taft, in transmitting the recommendation to Congress, declared that he by no means favored the suggestion.3

However the President complimented the Postmaster-General with having brought about economy in his department. But, as the Journal of Commerce observed, to bring about economy in a government department, and to ensure an economic administration of a trading enterprise, are two very different things.

In the British Isles municipal enterprises have been multiplied, following the Public Health Act of 1875, which act granted to sanitary districts authority to establish water and gas works, and the Municipal Corporations Act of 1882, which codified the municipal law. This latter act gives to municipalities the right to spend their income; but, in order to contract loans and make purchases or sales of land, they must obtain permission through the medium of private acts of Parliament.

The industrial undertakings of British towns are much less important than might be supposed from the rhapsodies they inspire in government ownership fanatics. In proof of this statement it is sufficient to enumerate the industrial operations of the London County Council.

[24]4. The London County Council was established in 1888. From 1888 to 1894 and from 1898 to 1906 it called itself progressive. Its progress consisted chiefly in seizing, by right of its own authority, the greatest possible number of public utilities. However, the distribution of the London water supply is not controlled by the Council, despite all its efforts to obtain such control. The control of water was given by the law of 1902 to the Metropolitan Water Board, composed of 66 representatives of the various local authorities comprised within the area of distribution, which is not less than 537 square miles, or 5 times that of London. The Board has the right to levy taxes, and it has acquired, by private contract and without opposition, the holdings of 8 companies for a total of about £1,900,000 ($9,253,000). It has spent one million and a half pounds sterling ($7,305,000) in public works. In 1904 it furnished 81,823,000,000 gallons of water to 7,000,000 people, or 32 gallons a day per capita, 53 per cent. of which comes from the Thames, 25 per cent. from the river Lea, and 22 per cent. from springs and wells.

The London docks were constructed by private companies. In 1907 the government introduced a bill to take over these enterprises from the companies, which received an indemnity of £22,368,916 ($108,936,000) from the Port of London. This latter corporation, presided over by Lord Devonport, who showed himself so energetic in the strike of the dock laborers, is composed of thirty members, appointed by the government, by the municipal authorities and by individual merchants. The Port of London [25] is so independent of the London County Council that the latter refused to guarantee the loans that the former was forced to contract in order to pay the indemnity to the dock companies.

Neither does the London County Council furnish gas to the inhabitants of London. The companies manufacturing gas were organized by private capital. In 1855 there were 20 of these, but by 1860 the number had been reduced to 13. Subsequently there were several mergers, which necessitated private bills. Thus a way was opened for an intervention which established a scale of dividends proportioned to the price of gas. The dividend rate was fixed at 4 per cent. If there is a decrease in the price of gas the dividend can be increased 1s 5d (34 cents) for each penny of the decrease in price, which was then fixed at 3s 2d (76 cents) for 1,000 cubic feet of gas of 14 candle-power. If there is an increase in the price the dividend is diminished in the same proportion. London is lighted by two gas companies. One company sells its gas at a rate of 2s 7d (62 cents). The London County Council has only the right of fixing the quality.

The Electric Lighting Act of 1882 provided that local governments could purchase, at the end of 21 years, any electrical enterprise established within their territories. The law of 1888 extended the purchase period to the end of 42 years.

Several local governments of London have established electrical service in a number of different ways. In 16 out of 29 of the local districts there are municipal plants, but they represent a service over only 55 ½ square miles, while the electrical [26] companies supply a surface of 64 ½ square miles. In greater London the municipal plants supply 167 square miles, and 19 companies 331 square miles.

The London County Council, in 1907, planned to create an electric central station supplying a district of 451 square miles; but, when the "progressive majority" of the London County Council was replaced by a "moderate majority," the plan was abandoned. Later Parliament passed a bill, demanded by 8 out of the 10 existing companies, permitting them to consolidate their systems. But the London County Council will still have the right to buy them out, in 1931, or at the end of any subsequent ten-year period.

In fact, the Council has exercised its authority actively only in the direction of operating tramways. In 1870 the Tramway Act authorized a local government, or any private company which had obtained its consent, to ask for a private bill in order to establish a line. The Metropolitan Board of Works of London granted several companies authority to establish lines. In 1894 the Council demanded the right to purchase these. In 1898 it bought out two companies, one of which possessed 43 miles of tramway lines in the north of London. The Council left to the company the right of operation during 14 years. In 1898 the operation of the other tramway lines was begun. The Council bought up the lease of the other companies in 1906. It has now 136 miles of tramway lines, and its receipts are diminishing.

The London County Council likewise attempted to [27] operate, beginning with 1906, a line of boats on the Thames. The first two years the undertaking resulted in a deficit of £90,683 ($441,626). The service was abandoned one or two years later. The 30 boats, which had cost, in 1906, £7,000 each, were sold in a lot for £18,204. The Council also took upon itself the demolition and reconstruction of a certain number of cheap lodgings. Therefore, in the way of actual municipal industrial services, it has managed a boat line upon the Thames, demolished and reconstructed cheap lodgings, and is now operating tramways.

The partisans of public operation say, none the less, that, "in principle, municipal ownership has been accepted." Only those who are honest add "but public opinion has confined it within very narrow limits." Moreover, the elections of 1912 have kept the progressives in the minority.4

5. According to an article in the Fortnightly Review, of January, 1905, it is in Russia that local public ownership and operation have been most widely extended. The sale of agricultural implements, medicines, magic lanterns, translations of Molière and Milton, the expurgated novels of Dostoiewski, sewing machines and meat are among Russian public enterprises. It is said also that it is useless for cities to demand subsidies from the government. The stock answer of the administration to all requests for aid is: Municipalize. This advice is easy and costs nothing.

[28]6. Ownership and operation on a national scale have been most widely developed in New Zealand. The constitution of 1852 gave to legislators of that country all possible authority without other restriction than "to do nothing repugnant to the English law." Nor are their powers limited, as in the United States, by a supreme court.

New Zealand is isolated. It has no competitors. It has large undeveloped resources. It has a territory of 271,300 square kilometers (104,344 square miles), or more than half that of France, and a population of 1,044,000 people, or 4 inhabitants per square kilometer (10 inhabitants per square mile). Naturally the experiments of a restricted population, distributed over a vast area, have not the same importance as those attempted by a population of several million inhabitants concentrated within narrow boundaries.

In a work entitled State Socialism in New Zealand5 Messrs. Le Rossignol and Stewart give us a complete picture of the Socialist enterprises which have been attempted there.

Most of the soil was originally government land. As we shall see further on, the government has not retained possession of it for the purpose of exploiting it.

The real development of governmental activity is chiefly due to the energy of one man, Sir Julius Vogel. At his instance a government life insurance system was established in 1869. In 1870 he outlined a [29] vast policy of public works, calling for an expenditure, in the course of 10 years, of £10,000,000 ($48,700,000), a sum which was actually doubled within that period. In 1876 he abolished provincial boundary lines, took over the land and the railways, and burdened the state with a fully developed administrative organization, the expenses of which were paid for by taxation, and carried out only with the help of loans and a heavy debt.

In 1879 New Zealand went through a crisis which would have ruined her if she had not been saved by the application of refrigeration to the transportation of meat. Even with that help it took her 16 years to recover.

I shall not speak here of the social legislation introduced by William Pember Reeves, from 1890 to 1895, which has frequently been remodeled.

New Zealand has owned the telegraph since 1865; the railways since 1876; the telephone since 1884. National coal mining and accident insurance were taken up in 1901, and fire insurance in 1903, at rates which render any competition impossible. From time to time the government has undertaken the operation of small industries, such as the purchasing of patents for the prussic acid process, a right to which the state leases to miners for a certain fee. The management of the oyster beds of Auckland, the establishment of fish hatcheries, the stocking of the rivers with trout, and the establishment of resorts for tourists and invalids are also among New Zealand government enterprises.

But, although New Zealand represents the maximum [30] of effort in the way of Socialist enterprises, few industries are directly managed by the government.

"Scarcely a month passes," says Mr. Guy H. Scholefield, "without some convention passing a cheerful resolution demanding that the government should step in and operate some new industry for the benefit of the public. Now it is banking; to-morrow bakeries; over and over again some moderate reformers have called upon the government to become controllers of the liquor traffic; once upon a time it was importuned to become a wholesale tobacco-seller; more than once to purchase steamers to fight the supposed monopoly of existing lines."6

"But," say Le Rossignol and Stewart, "notwithstanding these demands, the feeling seems to be growing that the government should not move too rapidly in the direction of State Socialism."

7. In nationalization of the soil New Zealand has had an experience, the more interesting in that most of the soil was once government land. Ought the state to have conserved its interest in the land, or was its action wise in transforming it into private property? The following facts regarding this question are to be found in that remarkable work, State Socialism in New Zealand, from which I have already quoted.

The Hon. William Rolleston, who became minister of Public Lands in 1879, held that one-third of the crown lands ought to be leased in perpetuity for a rent of 5 per cent. of the value of land, with a revaluation [31] every 21 years. The resulting resources might be applied to education.

The Upper Chamber granted the right of purchase at the value of the prairie land, or £1 per acre, after any prospective property holder should have cultivated one-fifth of his claim. Socialist legislation developed when the Liberal party, having acquired a majority in the elections of December 5, 1890, came into power on the strength of two issues, agitation against the great property holders, and agitation of workmen whose salaries had fallen since 1879 and who, in the month of November, had organized an unsuccessful strike.

John Ballance, head of the Cabinet in 1891, and John McKenzie, minister of Public Lands, were ardent partisans of government and property reform. Together they put in force five acts, one after the other, which have since undergone several modifications. Ballance, also a partisan of nationalization of the soil, was anxious that one-third of its lands should remain under the control of the state, to be leased by it, however, with periodic revaluation. His plan fell through. McKenzie granted leases for 999 years at a fixed rental of 4 per cent. on the capital value of the land at the time the lease was taken up, without revaluation. The area which could be held by one man was limited to 640 acres for first-class land, and 2,000 acres for second-class land. The system received the name of "the eternal lease." At this rate of lease, the government would lose more by way of land tax than it got by way of rent.

But, at the end of 10 years, the perpetual tenants [32] began to ask for the right to buy the freehold of their properties. The Labor party was constantly proposing a revaluation of rents. In 1907 the right of purchase was recognized, but under conditions of valuation which provoked the strongest resentment. The tenants maintained that the state's interest in the land was only the capitalized rental of 4 per cent. on the original value of the land.

The lease in perpetuity was abolished by the Act of 1907. However, under this system of leasing, which had been in force for 15 years, over two million acres of the best land in the colony had been parted with. In the place of the "eternal lease" was enacted the "renewable lease," a lease for 66 years, with provision for valuation and renewal at the end of the term with reappraised rent. But the public lands can always be sold immediately on the occupation-with-right-of-purchase system. It is therefore a mistake to believe that the government of New Zealand owns all its soil.

On March 21, 1906, the total area of 66,861,440 acres was held roughly as follows:

| Freehold… | 18,500,000 |

| Leased from Crown… | 17,000,000 |

| Held by natives… | 8,250,000 |

| Reserved for educational purposes and national parks… | 12,250,000 |

| Unfit for use… | 7,000,000 |

| Not yet dealt with… | 3,300,000 |

It is estimated that 63 per cent. of New Zealand families own property of £100 and above; and it is probable that 75 per cent. of the families own some [33] kind of property. A number of small properties are exempt from taxation. Those who are without property are young people earning large salaries who, with health and a fair chance, will achieve a good position in life.

The land laws have not only increased the number of proprietors, but, although they have had a Socialist aim, they have actually brought about anti-socialist results, since they serve to encourage the system of private ownership.

The Labor party advocates nationalization of the soil; but the tenants, supported by the freeholders, continue to demand the right of transforming their leases into property holdings. At a crisis they would insist upon a lowering of the rent. One witness, in 1905, made this profound observation before the Land Commission:

"I believe in the freehold because, in times of trouble, the freeholder is the man to whom the state will look; and the leaseholder is the man who, in times of trouble, will look to the state."

Messrs. Le Rossignol and Stewart, the authors of State Socialism in New Zealand, conclude:

"It is not easy to show that New Zealand has derived any benefit that could not have been obtained from freehold tenure combined with taxation of land values."

CONCLUSIONS

8. Except in the United States the telegraph and telephone systems are nationally owned and operated. [34] The coining of money is also a function of governments. The railways are government owned, either wholly or in part, in France, Germany, Austria-Hungary, Italy, Denmark, Sweden, and Belgium, but the extent of the private systems is greater than that of government lines.

Industrial operation by governments and municipalities is still very limited in scope. Nevertheless, it is already sufficiently widespread to make a conclusion possible as to whether the dreams of its advocates are being materialized, or their promises fulfilled.

Footnotes for Chapter IV

1. See Circulaire du Comité des Houillères, February 20, 1913.

2. Arthur Raffalovich in Journal des Économistes, October, 1912.

3. Journal of Commerce, New York, February 24, 1912.

4. Claude W. Mullins, L'Activité Municipale de Londres, Revue Economique Internationale, 1910.

5. State Socialism in New Zealand, by James Edward Le Rossignol, Professor of Economics in the University of Denver, and William Downie Stewart, Barrister at Law, Dunedin, New Zealand, 1 volume in 12mo, George C. Harrop & Co., London.

6. New Zealand and Evolution, page 58.

[35]

BOOK II

FINANCIAL RESULTS OF GOVERNMENT AND MUNICIPAL OWNERSHIP

CHAPTER I

BOOKKEEPING IN STATE AND MUNICIPAL TRADING ENTERPRISES↩

- 1. Report of Gustave Schelle to the International Statistical Institute.—Denmark.

- 2. Receipts and Expenses of Public Operation in France; Costs of Construction.—Receipts and Expenses Outside of the Budget.—Special Accounts.—Capital Charges.

- 3. British Municipalities. — Belgium. — Sweden. — City of Paris.

- 4. Austria.

- 5. Conclusions.—Attempts to Organize Special Accounts for Government and Municipal Trading Enterprises Have Failed. They Are Incompatible with a Homogeneous Budget. Sane Budget Regulations and Public Operation of Trading Enterprises Are Contradictions in terms.

1. I have already quoted from the report to the International Statistical Institute, compiled by Gustave Schelle, former minister of Public Works, [36] wherein he discusses the financial situation of the various state and municipal trading enterprises, from which he has received reports, with all the authority of his official position, and with a mind which has remained both alert and independent throughout his administrative career. The difficulties in the way of estimating and comparing the value of such enterprises are very great.

In Denmark, for example, railway outlays for pensions and general administration and inspection costs are borne by the railroads themselves. For other enterprises such costs are met by the general budget.

Before 1904 and 1905 the postoffice and the telegraph yielded no net proceeds. In 1908-1909 this was also true of the mint.

No report is made regarding the interest charges upon loans for the establishment of such enterprises.

In 1908-1909 the results of municipal operation of gas, electricity and water were as follows:

| COPENHAGEN | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Plants | Capital, Crowns | Net Proceeds, Crowns | |

| Gas… | 4 | 30,636,000 | 3,247,000 |

| Electricity… | 5 | 14,451,000 | 3,490,000 |

| Water… | 6 | 12,392,000 | 632,000 |

| PROVINCIAL CITIES | |||

| Gas… | 57 | 13,144,000 | 1,640,000 |

| Electricity… | 17 | 4,727,000 | 450,000 |

| Water… | 50 | 10,873,000 | 839,000 |

In Holland, according to information furnished by M. Methorst, director-in-chief of the Central Bureau of Statistics, the cost of constructing the postoffice, telegraph and telephone systems amounted, on [37] January 11, 1909, to 24,854,000 florins ($9,941,000). This capital bears an interest charge in favor of the public treasury of 3½ per cent., for the systems were established by means of public funds. Repayments are made periodically at a rate varying from 1 to 12½ per cent. The enterprise has a special double entry system, and no account is taken, in reckoning up receipts, of either free railroad transportation or official correspondence.

The funds for the operation of the Wilhelmina and Emma mines are supplied by the budget.

No information is given in the report concerning the financial results of municipal enterprises in Italy.

2. I quote literally the observations of M. Schelle concerning France:

A. Receipts and Expenses of Operation:

"In the case of the mints, the National Printing Office and the state railroads, the receipts and expenses of operation are placed opposite each other in budgets annexed to the general budget, and the difference in gain or loss is indicated only in this latter budget. The records of expenditures, however, as well as of receipts, are incomplete.

"In the case of the fiscal monopolies, the postal service and the official journal, the receipts of operation are included in the general receipts of the general budget, while the expenses are charged to the department under whose jurisdiction the enterprise may happen to be, without any comparison being made between receipts and expenditures.

[38]"As for the other and less important industrial enterprises, the provisions of the general budget furnish no indication whatever of their condition. Tentative receipts are mixed with the receipts of other enterprises under different headings.

"Sometimes the expenses are deducted from the gross receipts, and the net proceeds alone figure in the budget; sometimes they are included in the expenditures of the department concerned, now and then without being in evidence. Information on the subject of these enterprises is impossible except in the final accounts."

B. Costs of Construction:

"The costs of construction, in the case of certain enterprises, are so mixed in the accounts with other expenses as to make it utterly impossible to disentangle them. Even where enterprises have been made the subject matter of the budgets called annexes, the budget documents and the final accounts for each year indicate only the increase in the expenses to be incurred during the year under consideration, without regard to the expenses of former years. In order to get at the amount of capital employed, it is necessary to examine the final accounts of all the years. The resulting labor sometimes recalls that of the Benedictines, and, moreover, is far from always yielding satisfactory results, whether by reason of the antiquity of the expenses or the impossibility of disentangling them."

C. Receipts and Expenses Outside of the Budget:

"Government undertakings keep no daily record of the requisitions made on them by other departments, so that important financial transactions do not appear.

"Certain utilities profit gratuitously from services rendered [39] them by other public or quasi-public enterprises; thus the postal and telegraph departments pay the railroads for but a small share of the services which they receive from them.

"Public enterprises do not pay rent for the use of government property, for the real estate they occupy, nor are they charged with the materials they use. On the other hand, the National Printing Office includes among its receipts, at a rate which is generally considered high, the amount of work which it does for other departments. It does not include among its expenses, however, the interest on the capital sunk in the buildings in which it is installed.

"The postal and telegraph facilities granted to ministers and various public departments do not figure among the receipts of the postal enterprises.

Finally, among the annual expenses of the post and telegraph offices are included the subsidies paid to packet boats prompted, at least in part, by considerations altogether foreign to the mail service."

D. Special Accounts:

"When an enterprise possesses a technical equipment or a stock of merchandise, no document ever shows the true value of such equipment.

"Exceptions to the above are the special accounts published at the close of each fiscal year: 1st, in the match and tobacco monopolies; 2d, in the case of the state railroads. However the value assigned in these special accounts to stock and equipment is not a commercial value. It is a simple difference between the expenses of purchase and manufacture and the proceeds of actual sales.

"Moreover, the fixed capital, buildings, real estate, etc., [40] of the enterprises enter into these accounts in the same manner as the stock of manufactured products, so that it is impossible to get at the capital really involved.

"Finally, the amount realized from sales of real estate, when there are any, is not deducted from the capital, such sales being made by the Government Lands Department.

"The accounts of the Government Railroad Department published each year are no more satisfying. Statements as to the costs of construction are to be found among them, but these include only those expenses contracted directly by the department, and no mention is made of the very considerable expenditures which are covered by the budget of the ministry of Public Works.

"The Statistique des Chemins de Fer is the only document which gives an approximate idea of the actual costs of construction of the state railroads and that of the small line of Saint Georges de Commiers à La Mure."

E. Capital Charges:

"It is not sufficient to know the amount of actual capital invested in an industrial enterprise in order to be able to form a correct judgment as to its management. It is also necessary to be informed as to the capital charges. Exact computation is impossible unless the expenses relative to each enterprise have been covered by special loans. We must be content, therefore, with an approximation difficult to make at this late day, because no care has been taken to make such an estimate each year since the enterprises were established. In order to make any progress, it would be necessary to estimate the applicable rates based on the price of government bonds or of bonds guaranteed by the government at the time when the various construction expenses were [41] incurred. Expenses for building materials, etc., and for the installation and equipment of the various government enterprises have been a burden upon the Treasury since that date. This is evident in the case of the costs of construction defrayed with funds from loans not yet paid off. But it is true also of expenses paid for in this or that year out of the ordinary resources of the budget. These expenses may not be considered as paid off while a perpetual public debt exists, even though resources are at hand which might have been employed toward their extinction."

3. The municipalization of public utilities has considerably increased the expenses and debts of British local governments. M. Schelle declares, however, that he has been unable to obtain the data necessary to a compilation of statistics as accurate in character as the purposes of the International Institute would naturally require.

A portion of his report is devoted to the financial condition of the Belgian state railroad, of which we will speak later in detail.

In Sweden the principal state operations are the postal, telegraph and telephone services and the government railways. The receipts from the railways represent 1.30 per cent. of the average annual capital.

The City of Paris municipalized the service of burying the dead in 1905. In 1906 the receipts were 5,242,000 francs ($995,980), while the labor and equipment expenses were respectively 2,500,000 francs ($475,000) and 2,135,000 francs ($405,650), or a total of 4,635,000 francs ($880,650).

In 1910 the receipts were 4,660,000 francs [42] ($885,400). The labor expenses had risen to 2,760,000 francs ($524,400) while those for equipment had been reduced to 1,765,000 francs ($335,350). At the same time there was an outstanding loan of 348,000 francs ($66,120)—a total expense of 4,873,000 francs ($925,870).

In the case of the quarry operated by the City of Paris the results are still more unsatisfactory, according to a report to the Municipal Council in 1908. The labor expenses are very much higher than in neighboring quarries.

4. An important part of the report is devoted to Austria, and is based upon a previous report drawn up under the direction of J. G. Grüber, by Dr. Rudolph Riemer, secretary of the Central Bureau of Statistics.

Outside the usual monopolies the Austrian government owns docks and mines and operates lotteries.

In most of these enterprises the costs of construction and of equipment are indicated separately in the final accounting, but only those expenditures made during any one year are to be found there, regardless of those of the preceding years. The items for determining how much of the original debt has been paid off are lacking. Interest and sinking fund charges on loans contracted in view of government operation do not figure in the final accounting in the chapter especially devoted to the particular industry concerned, but in a chapter issued by the ministry of Finance under the heading, Public Debt and Administration of the Public Debt. Special information in regard to the auditing of the public debt may be [43] found in the annual report of the special committee (Commission de Contrôle) managing the debt. But in this report the information touching interest and sinking fund charges does not inform us as to the actual application of the loan.

The same conditions prevail in the case of the public debt contracted for the benefit of the railroads. Our information covers only interest and sinking fund charges on the amortizable debt. But even that portion of the debt does not represent all the loans contracted for the benefit of the railroads.

According to the Statistique des Finances de la Haute-Autriche et de Salzburg (8th annual report) the expenses of all the towns of Upper Austria arising from the operation of their utilities amount to 4.44 per cent. of all their expenses. The costs of construction are quoted en bloc in a special chapter.

The result of M. Schelle's investigation proves that almost everywhere the data necessary in order to determine exactly the profits or losses upon state or municipal industrial operations are insufficient.

"Whatever be the end in view when states or municipalities organize industrial enterprises—whether the object be fiscal or economic, for the sake of the consumer or even in the exclusive interest of employees—it is indispensable to know whether these enterprises are actually resulting in profits or losses, and the amount of each.

"As far as the essential functions of the state are concerned, such as providing for public safety, public highways, etc., the establishment of special accounts would be impossible and without much value, inasmuch as these [44] services provide no opportunity for direct payment on the part of consumers. Such services derive no receipts, properly so-called, nor can they be abolished. When it is expedient to know whether the management of these activities is not too extravagant, it is necessary to proceed by contrasting one year with another, or by comparing certain items of expense with similar items in other countries, or in other localities.

"Public industrial enterprises are almost never essential, since they may be intrusted to private operation. They resemble private enterprises and provide opportunity for special receipts. It should, therefore, be possible to furnish to the taxpayers, in whatever concerns them, means of knowing the amount of income, just as opportunities for such information are afforded to the stockholders or creditors of any private concern. To pretend that the financial side of state or municipal enterprises should be neglected because such undertakings are created for the public interest is only an effort to side-track possible criticism. Public management, like any other, can be good or bad. If it is directed toward securing advantages, justly or unjustly, to this or that class of people, whether consumers or employees, it is at least necessary that those who are to foot the bills, that is to say, taxpayers, should know, personally or through their representatives, whether the contributions demanded are not exorbitant. Such a requirement should not be questioned in any country.

"From another point of view, how can the pretention be sustained that, in certain cases, the state or municipality can serve the public to better advantage than private companies when such states or municipalities do not furnish the public with adequate information concerning their administration.

[45]CONCLUSIONS

5. "In fact," concludes M. Schelle, "the efforts made to organize special accounts for state and municipal industrial enterprises have failed. Public documents sometimes furnish precise enough information as to receipts or expenses of operation, but it is nearly always difficult to discover the amount of the costs of construction, and it is impossible to get any adequate idea of capital charges, interest and amortization." His observations, in regard to Denmark, Holland, France, and Austria, prove that in no respect do the accounts ever bring out the real gains or losses of state enterprises.

The difficulties encountered arise from the fact that a state or a municipality cannot have more than one budget. Moreover all the receipts should be entered on one side, all the expenses on the other. In this respect at least public organizations should be managed like private corporations. If these latter fail their creditors demand the amount of their claims at so many cents on the dollar. A well-organized state should have only one purse, nor should any distinction be made between its various loans. All should be secured upon one single guaranty—its credit.

Without a unified budget sound finance is out of the question. A special account for a state or municipal industrial enterprise can have only a fictitious value.

In other words, sane budget regulations and public management of trading enterprises are contradictions in terms.

[46]CHAPTER II

THE BELGIAN STATE RAILROADS↩

- 1. Accounts.—Capital Charges.—Rates of Issue.—Review of Receipts and Expenditures.—Final Profits Do Not Contribute toward Balancing the Budget.—The Budget Has Obtained No Advantage from State Operation of Railroads.

- 2. Passengers and Shippers.—Increase of the Rate on Pit Coal.—Resolution of November 29, 1911.—Plan of M. Hubert.

1. Railroads are the most important industrial enterprises undertaken by a state. What, then, are the financial results of their public operation?

The Belgian state railway was established by the organic law of June 1, 1834. By reason of the length of time it has been in operation it has a right of precedence.

Marcel Peschaud has published in the May and June numbers of the Revue Politique et Parlementaire a remarkable study of the Belgian railways, but his analysis would lead us too far astray. I must confine myself, therefore, to a résumé of what M. Schelle has to say on the subject in his report to the International Statistical Institute.

The law of 1834 provided that a complete account of the operations of the railways be presented to the [47] Chambers annually, by which account are understood the receipts and expenditures, together with the use of the funds for the construction of lines placed at the disposal of the new department. The accounts thus rendered soon proved to be altogether inadequate.

In 1845 estimates of interest and sinking fund charges were added to the previous requirements. Controversies arose over these estimates, and it became necessary to change the system several times in order to settle the rate question. At the close of 1878 it was decided that the management of the railroads should make up a balance sheet in the form of commercial balance sheets. This was done, but capital charges were computed at a uniform rate based on a period of retirement of ninety years.

Moreover, according to M. Nicolai (Government Railways of Belgium, 1885) the cost of replacements and reconstructions was charged to the construction accounts without deductions for renewals and repairs. On the other hand, the annual payments for the purchase of lines which should have been charged to construction were charged to operation.

"Never," says the minister of Public Works (Report for the year 1905), "have the railway accounts, that is to say, the accounts prescribed by law, been found other than defective. On the contrary, the statements of conditions, the statistics, the estimates and reports, relating in part to such items as interest, sinking funds, pensions, etc. (which are not within the legal powers of the railroad department to pass upon), have never ceased to be the subject of the most lively discussions. Charges have been made in turn, or sometimes simultaneously, that [48] the profits were swelled and concealed, that there was too much red tape, even to the point of disregarding the essential rules of a business enterprise, or that there was not enough control, because the accounts were separate from those of the Treasury. The subject has furnished an inexhaustible theme of argument."

Of late years it has been decided that the data contained in the annual reports ought to be kept with the Treasury accounts, and that the balance sheets should be made up between the department of Public Works and that of Finance. The accounts for 1905 and the years following have been established upon this new basis.

As for capital charges met by enlarging the public debt, a rate of issue was adopted, which varied from 4.90 per cent. to 3.11 per cent. Then the government proceeded to publish, under the title of "annexes" to the financial report: 1". A general balance sheet for the year ending December 31, showing on the credit side construction costs since the beginning of the undertaking and the gross operating receipts and on the debit side the capital already retired and remaining to be retired, the amount of charges upon this capital, the dues and rents paid by the state railway system to other railroad enterprises, operating expenses and the profit and loss balance. 2". A separate account of operating receipts and expenditures for the preceding year. 3". A provisional account of operations for the current year, and of profit and loss, comprising, on the one hand, operating expenses, pensions charged to the [49] general budget, fixed charges, including yearly installments, and the portion of receipts due to companies whose lines are operated by the government; and, on the other hand, the profits of operation, properly so-called, together with various other profits. 4". A table recapitulating the financial results since the establishment of the system (1835) setting forth the annual balances in profits or in losses. 5". A table of interest and sinking fund charges from the beginning. Finally, tables of operating statistics.

As a result of the new system adopted the profit shown in a large number of the previous reports was transformed into a deficit.

The report for the year 1909 gives the following results, computed in francs:

| INSTALLATION COSTS | |

|---|---|

| Francs | |

| Lines constructed by the state… | 675,655,000 |

| Lines constructed by contract… | 176,317,000 |

| Lines purchased and completed… | 978,017,000 |

| Completion of lines operated under rentals… | 10,293,000 |

| Station structures… | 72,928,000 |

| Surveys… | 18,547,000 |

| Equipment… | 719,188,000 |

| Total… | 2,650,945,000 |