CHARLES DUNOYER.

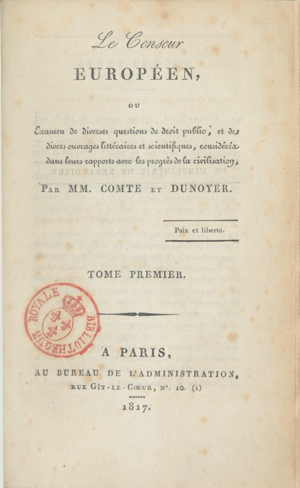

"On the Influence exerted on Government by the Salaries paid for carrying out Pubic Functions", Le Censeur européen (1819)

Charles Dunoyer (1786-1862) |

|

[Created: 27 March, 2025]

[Updated: 27 March, 2025] |

Source

, "On the Influence exerted on Government by the Salaries paid for carrying out Pubic Functions", Le Censeur européen T.11 (15 Feb. 1819), pp. 75-118.http://davidmhart.com/liberty/FrenchClassicalLiberals/Comte/CenseurAnthology/EnglishTranslation/CE17-Dunoyer_GovtSalaries_T11_1819.html

[D…..r], "De l'influence qu'exercent sur le gouvernement les salaires attachés à l'exercice des fonctions publiques" ("On the Influence exerted on Government by the Salaries paid for carrying out Pubic Functions"), Le Censeur européen T.11 (15 Feb. 1819), pp. 75-118.

This essay is part of an anthology in French: Charles Comte and Charles Dunoyer, An Anthology of Articles from Le Censeur (1814-1815) and Le Censeur européen (1817-1819). Edited by David M. Hart (Pittwater Free Press, 2021). In enhanced HTML.

On the Influence exerted on Government by the Salaries paid for carrying out Pubic Functions↩

[75]

Much has been said about the taxes we pay to government in terms of the hardship they impose on us, the effects they have on our comfort, our prosperity, and the progress of national wealth; but less attention appears to have been paid to the influence these taxes exert on the government itself. Our aim here is to consider them from this particular point of view. We propose to investigate the effect, with respect to the government, of the salaries we pay to those who govern. We wish to examine whether one can, without endangering liberty, make public service into a lucrative profession; whether the government can be salaried without it becoming hostile to the very interests it is charged with protecting; whether it is possible to turn it into an industry without it degenerating into exploitation and despotism.

There are countries where no one can become wealthy except through the practice of private professions, where public service is a burden for all and a [76] benefit for none, where power brings to those who wield it only respect and fatigue, where public positions, far from being sources of profit, generally do not even offer a way of making a living—except for lower-level employees, the laborers of the administration, so to speak. We can cite as examples certain cantons of Switzerland; we can also cite the United States. There are very few clerks in the Republic of Geneva who are not better paid than the most eminent public officials. The republic grants its chief magistrate only eighty louis per year; it gives no more than sixty to its second-tier officials. In other states of the Helvetic Confederation, the salaries attached to high offices are even more meager. They are no less so, in proportion, in the United States of America. The civil list of the president of the twenty-two states does not come close to matching the salary of one of our ministers: he receives only $25,000 a year, about 125,000 francs. The ministers receive only $4,500, about 22,500 francs. The expenditures of the speaker and various internal departments, excluding war and the navy, [77] amount to only one million eight hundred thousand dollars, about 9 million francs. The war department costs, in francs, 28 or 29 million; the navy 20 million. The budget for all ordinary annual expenditures does not exceed 11 million 500 thousand dollars, or about 57 million francs. It must also be noted that in the United States money is worth, relative to other goods, about a third less than in France, which reduces the president’s civil list from 125 thousand francs to 83 thousand, the ministers’ salaries from 22 thousand to less than 15, and the government’s total expenditure from 57 million to about 38. In general, in the United States, public officials are reimbursed, not enriched; they receive compensation, not a salary; they maintain or increase their fortunes through the same means as other citizens—through agriculture, commerce, the practice of industrial arts, and private professions—never through the exercise of public functions. It has been such a principle to prevent the exercise of power from becoming a means of profit that it has been enshrined as a formal legal provision. A fundamental article of the Pennsylvania Constitution, [78] an article adopted by most of the Union’s states, requires that any man who does not possess sufficient property must engage in some private profession that can provide him with an honest livelihood. This article also states that no lucrative positions should ever be created; and it adds that as soon as a post offers enough profit to tempt the greed of multiple individuals, the legislature must hasten to reduce the salary.

In France, our views on all this are quite different from those of the Americans. Instead of saying that any man without property should engage in a private profession, we say that an honest man who lacks wealth should strive to obtain a salaried position and seek to live off the public sector. What shocks us is not that one might make a profitable career out of exercising power; what would shock us is if any class of individuals sought to arrogate the exclusive privilege of exploiting it. We hold only one maxim regarding public office: that such posts must be equally accessible to all. That principle granted, we universally agree that there can never be too many such positions, nor can they be too generously endowed. So long as this career [79] is open to every with such an ambition, we are content that they find in it the means to live; we want power to be not only the foremost, the noblest, but also the most lucrative of all industries. Accordingly, we create as many positions as we can, and endow them with all the grandeur we can muster. We grant, for example, to the supreme head of the administration a sum approximately equal to the total expenditure of the government of the twenty-two United States of America. We set the civil list at 34 million. A single one of our ministers receives more than all the American ministers put together. The rest are paid in proportion. Ultimately, we attach such salaries to the exercise of power—especially in the higher offices—that among us there is no kind of industry where better returns are generally made, and in France the most profitable trade by far is that of governing.

There is thus this difference between us and the people we have just mentioned: we generously salary our public officials, whereas they merely compensate theirs; we pay them in money, while they [80] pay them chiefly in esteem; they make public service a burden, while we make it a path to fortune. The question now is: which of us, or of these people, demonstrates the greater wisdom and foresight? Which form of government—those that are salaried or those that are not—are more apt to fulfill their purpose, under which the security of persons and property, the liberty of opinions, of conscience, of all industries, are best established and most scrupulously respected?

Looking first only at the facts, without inquiring yet into the causes to which they should be attributed, we are forced to recognize that the interests needing protection are better safeguarded in countries where public officials are barely compensated than in those where they are lavishly endowed. Thus, for example, it appears to be a fact that property—the foremost interest any government must defend—is more secure from any private violation in the United States, where legal protection costs less than forty million per year, than it is in England, where public expenditures amount annually to over three billion. It likewise appears certain that in countries where governments demand [81] a significant share of citizens’ wealth as their salary, there is less security for individuals and less liberty in thought and action. One need only glance at countries where public service is a lucrative profession to see that individuals there are subject to far more harassment, violence, and coercion than in those where it offers no opportunity for gain; that more arbitrary acts, for example, are committed in France than in the United States; and, generally speaking, that despotism tends to rise in direct proportion to public taxation.

But let us not stop at merely pointing out these facts; let us show that they are the consequence of the cause we have stated, and that where government becomes a means of making one's fortune, it must, by the very force of things, degenerate into tyranny.

To begin with, one constant truth is this: the mere act of making the exercise of power into a lucrative profession gives those who wield it an interest that is opposed to that of the rest of mankind. Power, considered as an industry, has a character quite different from that of most other forms of labor. While all private industries thrive through mutual prosperity, that of officeholders [82] can only flourish at the expense of all the others. The labor of a public official is far from being productive, as is well known: everything he is given, in exchange for his good or bad services, is definitively lost to the common wealth. Ambition, which is merely competition in the career of power—ambition, so fruitful in good results within ordinary occupations—is here a principle of ruin; and the more a public official seeks to advance in the profession he has chosen, the more he tends, quite naturally, to rise up the ranks and to increase his earnings, the more of a burden he becomes to the society that pays him. To make public office a means of making one's fortune is thus to create a class of men who are, by their very status, and in fact if not in intention, enemies of the well-being and prosperity of all others.

Moreover, it is to cause this class of men to grow without limits. Every living species, every nation, every class of individuals, every family tends naturally to increase in proportion to its means of subsistence. To allocate to the class of men who pursue official careers a more or less substantial portion of public revenues [83] is therefore to provoke, within this class, a population growth equal to the number of individuals that these revenues can support; and since it is the natural order of things that children follow the same profession as their parents, provoking such population growth means ever-increasing multiplication of men who seek to make a profession out of exercising public functions. We will not dwell further on this point of view. We have already shown elsewhere how salaries make office-seekers proliferate; we refer the reader to the volume in which this phenomenon has been developed. [1]

But it is not only by multiplying births within families devoted to public service that salaries tend to grow the governing classes; it is also by constantly attracting new recruits; they grow from without as well as from within, by accession as much as by generation. The effect of salaries is to stir ambitious passions in every rank of society, and [84] to provoke continual entry of the laboring classes into the governing classes. When public service is a lucrative profession, it happens to this profession what happens to all sectors of industry where large profits can be made: everyone turns toward it. There is even a special reason why the crowd flocks toward government more eagerly than toward any other profession. Success in ordinary careers is only possible under certain conditions that one must necessarily meet. A certain degree of talent, activity, orderliness, intelligence is required. None of this is strictly necessary to become an officeholder: chance, intrigue, and favoritism determine most appointments. From that moment, there is no one who does not believe himself capable of obtaining one; government becomes a kind of lottery in which everyone flatters himself that he will draw a winning ticket. It presents itself as a fallback for those who have no other; all men without a profession aspire to make it their trade; and an almost countless multitude of schemers, idlers, honest and dishonest men throw themselves pell-mell into this [85] career, where there soon appear a thousand times more bodies than there are roles to assign.

Such is the first effect of salaries. This effect has two inevitable consequences, which must be elaborated. The first is that as aspirants to power multiply, the government is compelled to extend its functions. The second is that as it extends its functions, it is compelled to increase its expenditures. Naturally, public power should not have many duties to fulfill. To ensure internal and external security is, more or less, its whole task. But how can it keep within its bounds, when an ever-growing number of staff press it to exceed them? How can it restrict its action when its tools multiply beyond all measure? It is clear that the more the path fills up, the more it must widen; the more its branches must extend and multiply. Thus, a government which, by the principle of its foundation, ought to concern itself only with the maintenance of security, will be led—so as to create markets for the ever-swelling crowd of its dependents—to occupy itself with a multitude of matters [86] more or less foreign to its natural functions. While watching over public safety, it will want to take charge of education, of health, of directing thought, of shaping morals; it will claim the right to supply certain commodities; it will set itself up as the regulator of most types of labor; in the end, it will grow to such proportions that it will soon be impossible to escape its action in any movement, any thought, any part of one’s existence.

That is not all; as the multiplication of claimants forces it to extend its activity to new objects, the multiplication of its activities will necessarily compel it to increase both the number and weight of taxes; so that the more burdensome its action becomes, the more costly it will be: with every new creation of offices, it will simultaneously reduce both the freedom to act and the mays of making a living; it will increase the weight of taxation at the same time as it multiplies restrictions, and there will be no end to its encroachments on the independence and property of the citizens. [2]

By continually increasing the class of individuals who devote themselves to the exercise of public functions, salaries therefore make inevitable [87] the indefinite multiplication of offices and the unlimited growth of public burdens. These consequences, in turn, have others that are no less worthy of attention. As power thus expands and grows heavier under the influence of salaries, new reasons of a different kind arise for it to expand and grow heavier still. As it degenerates into a form of exploitation, it becomes the source of a thousand disorders, the repression of which then demands that it increase yet further in both scope and intensity. It fills society with idlers, beggars, thieves, bankrupts, and wrongdoers of every kind.

Now, the more criminals abound, the more the government must be strong in order to repress them. It populates society especially with ambitious and discontented individuals, and this is chiefly what compels it to become oppressive. It is impossible for a government to raise and distribute large sums of money without creating many enemies and many envious rivals for itself—many enemies, because it becomes unbearably burdensome for those who pay; many envious ones, because it becomes extraordinarily profitable for those who receive. It thereby places itself in a state of hostility both with factions who passionately covet [88] its privileges, and with the general public who, with all its strength, aspires to be free of them. And it finds itself compelled, in order to prevent its rule from deteriorating or from passing into other hands, to surround itself with spies, henchmen, state prisons, scaffolds, and to arm itself with a thousand tools of violence and terror.

Such is the influence of salaries; such is how, by turning the exercise of government power into an industry, one turns those who are entrusted with it into a class hostile to the well-being of all others; how this class then takes on indefinite expansion; how, as it grows and multiplies, the government is forced to extend its functions and raise its expenditures; how, as it thus encroaches on the independence and fortunes of citizens, it becomes the source of many disorders that it can repress only by becoming still more oppressive; how, finally, by growing and weighing ever more heavily, it ends up surrounding itself with a whole people of rivals and enemies, against whom it can only defend itself by descending to the lowest depths of violence and arbitrariness.

And this is no idle theory we are developing. One need only look around [89] to find striking proof of the danger involved in making public service a lucrative profession. See to what disorderly expansion salaries have caused the administration to grow—especially since the exploitation of public office ceased to be the privilege of a single caste, and since anyone has been able to devote himself to this kind of industry; especially since the head of the last government began to make it so profitable. How the number of officeholders has multiplied! How the functions of power have expanded! How the weight of taxation has increased! We regret not having before us the almanacs published over the last thirty years. It would be interesting to show how, year after year, the administrative workforce has grown; how the offices, the waiting rooms, the barracks have become progressively overcrowded. One can judge from what has occurred in certain departments what has likely occurred in all.

In 1791, the central offices of the tax administration had only 116 employees; today they have 190. At the same time, there were only 83 departmental directors; today, with the territory unchanged, there are [90] 88. The number of inspectors in 1791 was only 166; today it is 216. The number of controllers was likewise only 166; now it is 232. In 1791, Paris had only one registration director; today it has three, all regarded and paid as first-class directors. In 1792, eighteen offices sufficed in Paris for the distribution of stamped paper; since then, the number has grown so much that some distributors barely collect, in a quarter, a sum equal to their salary. In 1813, the stamp printing workshop had only 159 employees to supply paper to 130 departments; today, to supply just 84 departments, it has 174: it needs 15 more employees to serve 46 fewer departments.

In 1791, the central customs administration had only 58 employees; today it has 108. That same administration, in 1791, had only 15,000 officers; today, with the customs border to be guarded being the same, the number of officers is nearly 24,000: it has grown by more than a third. In 1811, there were only 8 agents at the Paris customs office; [91] now, to collect far less revenue, there are 21. There were only 17 at the salt warehouse; today there are 28, despite revenues having significantly declined.

If one took the trouble to make such comparisons across the various branches of public service, one would find that the workforce has grown everywhere in the same proportion. It has grown in all ministries, in internal administration, in the justice system, and in the army. It has especially grown in the general staffs. Consider, for example, the growth that the army’s general staff must have undergone during wartime, by looking at the growth it has seen in peacetime. At the time when our military forces were at their peak, in 1812, we had only 553 lieutenant generals or major generals. Since the Restoration, the number of general officers has nearly doubled: it has increased from 553 to 951. A single company of the king’s bodyguards, with no more than 240 men, today has in its general staff as many senior officers and generals as the largest army corps under Bonaparte.

And to fully grasp [92] the staggering growth of the family of officeholdings, it is not enough to look inside the administration; one must look around it. It is not enough to count those who already hold office; one must also count those who seek it, who aspire to it. These latter groups encompass nearly the entire nation. Whether one goes east or west, south or north, one finds everywhere the same hunger for public office. There are hardly any families—especially in the poorer departments—that do not lift pleading eyes toward the administration, asking it to take responsibility for the future of at least some of their children. This is the upward movement Bonaparte spoke of: from all sides the nation rises to desert to the government and claim a share of the tax it levies on itself.

As this movement has driven more men toward power, power has been forced to expand its framework. It has not contented itself with multiplying posts within existing administrations; it has created a multitude of new ones. One could probably count thirty kinds of administrative offices it has created to open avenues for the ever-growing crowd [93] of aspirants, or to increase its resources. The office of tobacco, the office of salt, the office of gaming, the office of hospitals, the office of schools, the office of commerce, the office of manufacturing, etc., etc., etc. . . .

It was not enough for government to multiply the number of jobs; it also had to multiply salaries, and the more its domain expanded, the more all its expenditures increased. There are scarcely any branches of service whose expenses, in the past twenty-six years or fewer, have not doubled or tripled: here are a few examples.

In 1791, personnel expenses in the central administration of registration and public lands amounted to only 325,000 francs; today, they amount to 774,000. Departmental directors cost only 600,000 francs; they now cost nearly 1,500,000. Inspectors and controllers together received only 840,000 francs; today they are paid more than two million. Stamp office employees cost only 100,000 francs; they now cost more than 240,000. The total expenditure of the registration administration did not exceed four million; it now surpasses ten. — The same growth has occurred in customs expenditures. The expenses of that [94] administration in 1791 did not exceed eight and a half million; today, although the customs line is unchanged, they exceed 23 million—they have nearly tripled. — In 1802, the general expenses of the Ministry of the Interior, including the salaries of prefects, sub-prefects, prefectural councilors, and general secretaries, amounted to only 30 million; those same expenses today amount to nearly 40 million, even though France is now reduced in size by more than one-fifth. In 1802, the office staff of this ministry, including those of bridges and roads and public education (which were then part of the interior ministry), received together only 625,000 francs; today they receive nearly 1,300,000. — Today, the expenses of the Ministry of Justice are 8 million higher than they were in 1802, when France was one-fifth larger. — In 1802, the gendarmerie cost only 14 million; today, even though France has 22 fewer departments, it costs nearly 28 million. — In 1802, the budget for all ordinary expenses, including the public debt, was only 500 million; today, even though France is one-fifth smaller, the budget for those same expenses is over 680 million.

[95]

It is truly curious to see how, year after year, the budgets have gradually increased as the multitude of officeholders has grown and the domain of administration has expanded. As we said, ordinary expenditures did not exceed 500 million in 1802; they rose to 589 in 1803. They reached 720 in 1807, 772 in 1808, 786 in 1809, and 795 in 1810. In 1811, they hit one billion. They rose to 1 billion 30 million in 1812, and in 1813 they exceeded 1.15 billion. At the time of the Restoration, France’s territory having been reduced by more than a third, public expenditures were naturally expected to decrease significantly; yet they remained proportionally higher than they had been before the fall of the empire, and the budgets continued their upward trajectory. Indeed, while in 1815 the budget for ordinary and extraordinary expenditures amounted to only 791 million, that of 1816 rose to 884 million, that of 1817 to 1 billion 69 million, and that of 1818 to 1 billion 98 million. The budget for this year will no doubt show a reduction due to the departure of foreign troops, but [96] it is likely that, if it is lower in one area, it will be higher in another, and one will still observe an increase in the ordinary expenditures of the administration.

There is nothing in all of this that should surprise us, nor anything we can reasonably complain about. These consequences are the natural and inevitable result of the mercenary character we have given to the administration. As long as we insist that public service be a job, an industry, a lucrative profession—and the most lucrative of all professions—it will inevitably follow that the number of officeholders will constantly increase, that the government will extend its usurpations day by day, and that its expenditures will grow daily. Salaried positions will give rise to more salaried positions; offices will breed more offices; the spirit of taxation will disguise itself under a thousand forms to seize the public’s income by surprise. When it is no longer possible to take anything more from current revenues, the benefits of credit will be extolled, and borrowing will begin to devour capital. Not only will the administration never show a surplus on the funds allocated to it, but even though it is granted every year everything it requests, [97] it will still exceed its appropriations every year. It will treat arrears as a resource and inflate its debts in order to increase its expenditures. It will, after several years, request millions more than were originally approved for a given year. Ministers will allow themselves to sell off government bonds and add to the public debt without any authorization. For several years, no account will be given for funds of uncertain value. Knowledge of important branches of public revenue will be withheld from the legislative chambers. No mention will be made of profits obtained through the trading in public securities. No account will be given of the proceeds from minting coins. Various unauthorized fees will be collected under different guises. In the end, there will be no trick that is not devised to try to get a little more money each year. All of this will happen despite the best intentions of the ministers, and solely due to the force of circumstances. In vain will the government promise to reduce the number of its employees and cut its expenses; it will, in spite of those promises, increase both its expenses and its number of employees. We have a recent and memorable example of this. [98] In 1817, the ministry had made a firm commitment to push reforms and cutbacks as far as possible in 1818. In 1818, it requested nineteen million more than in 1817; and, in making this request, it did not hesitate to affirm that it had scrupulously kept its commitment and pushed reforms and reductions as far as possible. Let us add, to better highlight the irony of such words, that at the very time this 19-million increase in expenditure was made, the administration's workforce was further expanded, and that the minister who spoke of the reforms had increased the number of his employees from 1,352 to 1,355. Such is the way governments with salaried officeholders fulfill their promises of retrenchment. For them, to retrench never means to renounce existing abuses; at most, it means holding back on introducing new ones. And if, from one year to the next, they have only increased lucrative posts by the hundreds, if they have only added tens of millions to already scandalous expenditures, they will believe themselves to have practiced a remarkably strict economy; they will boast of their sacrifices; they will claim to have scrupulously [99] fulfilled their promise to reduce expenses.[3]

It seems unnecessary to pursue these observations further. What little we have said appears sufficient to resolve the question we set out to answer. If it is true, as both reasoning and facts demonstrate, that it is impossible to endow offices and turn public service into a means of enrichment without multiplying the number of officeholders beyond all measure; if it is true that, as this class of men grows and multiplies, the administration is forced to continually extend its functions and its means of defense; if it is true, finally, that as it [100] encroaches and becomes more threatening, it is forced to constantly increase the weight of taxation—then it is proven that, by the mere fact that public service takes on the character of an industry, it must necessarily degenerate into exploitation and despotism; it is proven that under governments with salaried officeholders, there can be neither liberty of action, nor inviolability of persons, nor security of property.

And indeed, what liberty of action can exist under governments that, in order to provide work and livelihoods to the ever-growing multitude of job-seekers, must interfere in everything, appoint regulators, and impose constraints on industries that ought to be the most independent? What security can persons enjoy where governments, in order to defend themselves against the greed of factions stirred up by their expenditures, or against the discontent of a public they have drained and overburdened, are forced to surround themselves with informers, dungeons, special tribunals, and to sow everywhere mistrust and terror? And what security can there be for property, where the administration, as it [101] grows, must always further expand its encroachments on private wealth? Where it demands every year, as its salary, a fifth, a quarter, a third, even up to half of all public revenue? Will it be said that it protects property against private attacks? That can only be partially true, at best; for as a government impoverishes a country through excessive expenditure, it necessarily increases the number of thieves, and a time comes when it causes more thefts to be committed, unwittingly, than it suppresses. But even if, by taking the biggest portion of all national income, a government succeeded in preventing or punishing every private assault on property, it would still be untrue to say that it protects property. What does it matter to you if a government defends your goods from thieves, if it takes from you every year in taxes more than thieves ever could? If you must give it more than robbers could steal from you, even while it claims to protect you from them? Who would dare to say, for example, that the English government—which costs its subjects over three [102] billion annually, more than half their total income—truly protects their property? [4]

It is therefore true that there can be neither security for persons and property, nor independence for industry, opinions, or consciences, where government takes on the character of a lucrative profession. Such a government naturally tends toward the invasion of all liberties and of all national revenues; and one can say that a nation which, in establishing its political institutions, attaches large salaries to the exercise of power, is infallibly laying the foundations of tyranny.

Let us add that if making public service into an industry is dangerous for the liberty of the governed, it is scarcely less fatal to the [103] security of the governors. Salaries, by causing public officeholders to proliferate, soon multiply them to the point where there is no longer room for all within the same business. One can see an example of this terrible phenomenon in France. There are perhaps in the kingdom ten times more aspirants to power than the most enormous administration could ever accommodate. One sees, amassed on the soil of old France, all the men who once sufficed to administer half of Europe. There one finds all the employees of the former monarchy, and all the new men whom the latest purges have brought onto the scene. One would easily find there enough to govern twenty kingdoms. Now, when matters have reached this point—and the natural effect of salaries is to bring them there—it is no longer possible for governments to enjoy peace. Their rest and security are just as incompatible as the people’s liberty is with the existence of this mass of individuals who have made, or who aspire to make, an industry out of the exercise of public functions. Unless they are wise and skillful enough to send this rabble of public men [104] back into private life, governments are left with no viable way to deal with them. What, indeed, could they do? Admit them all? That is obviously impossible. Admit one particular faction in preference to others? That would be to set themselves against the rest. Compose a mixed party from men chosen from all factions? That would be to alienate all of them. Try to play one group off against the others? That would only make all of them more hostile. Let anyone reflect on it, and they will see that a government which has boundlessly multiplied officeholders around itself and is then forced to operate in the midst of such a population, without being able to integrate them into its ranks, truly has no means of securing its own course. It drags on amid factions that harass it and far from the public that abandons it to their mercy—a precarious and shameful existence that nearly always ends in a violent downfall.

What unrest has the government not experienced over the last four years, amid the old and new nobilities, amid the officeholders of the ancien régime and those brought forth by the Revolution? At first it sought to surround itself with men of the monarchy—it stirred up the men of the Empire: [105] this led to the revolution of March 20. Then on September 5, it appeared to seek a rapprochement with men of the Empire—it stirred up the monarchists: they sounded the alarm; they were accused of having fomented the gravest disorders, and not long ago there was even doubt as to whether they had conspired against the government. Today, caught between these factions, unable to reject any one of them without peril, incapable of satisfying all their demands, the government finds itself in a violent and inextricable position—one it will vainly try to escape from so long as the cause that perpetuates it endures, so long as government remains a lucrative profession, so long as the possibility of making one’s fortune in office draws everyone into the pursuit of public posts and multiplies the factions surrounding the government.

It would therefore be absolutely essential—if there were the slightest desire to consolidate the government and make it favorable to liberty, to shield it from the assaults of ambition and prevent it from degenerating into despotism—to strive against this deplorable tendency of the public to enter public office, to live off public office, to better and enrich themselves by means of public office. But is there any way to [106] reverse a tendency that has such deep roots, that has become so general and so powerful? This is the question we must now examine.

History teaches us what kind of remedy has been employed, in other times, to put an end to such disorders.

“The Guises,” says M. de Lacretelle, [5]“at first sought to increase the number of their partisans by the liberality and favors that usually mark the beginning of a new reign. They debased the Order of Saint Michael by distributing it too freely. But they soon repented of having multiplied the number of petitioners around them. The Cardinal of Lorraine let his impatience explode with ferocious brutality. The court was at Fontainebleau; the town was filled with people who had come to submit petitions either to the king or to his ministers. The Cardinal of Lorraine had a gallows erected beside the château, and had an ordinance proclaimed by public crier, declaring that all who had come to Fontainebleau to request favors must leave within twenty-four hours, under penalty of being hanged.”

[107]

We do not propose to imitate such conduct. The remedy of Cardinal of Lorraine, aside from being somewhat harsh, would clearly be inadequate. If one were to hang today all those who covet or solicit public office, one would have to hang half of France—starting with a portion of its deputies, who during the legislative sessions come here for no other reason than to act as petitioners. Moreover, it would be a very poor means of discouraging the pursuit of office to try to repel by violence those who wish to obtain it. Such a remedy, far from extinguishing ambitious passions, would only inflame them further. The one thing that men in our time are least willing to endure is that the holders of power—whoever they may be—should claim the exclusive right to exploit others. If it is agreed that the exercise of public functions is to be a means of fortune, then everyone will want the right to make his fortune by this means. If you are to fleece the public, no one else will want to be left out. If France is to be devoured, the whole nation will gradually [108] ask to take part in the feast. These outcomes are inevitable. Governments that have built themselves a rich domain upon the revenues of the people must no longer expect to remain tranquil possessors of that wealth. If they still enjoy it without remorse, they will no longer enjoy it without fear: their fate is to live amid factions and unrest. It is no longer in their power to prevent the spectacle of the immense spoils they distribute to their creatures from inflaming distant greed and raising up around them a turbulent and ever-growing population of ambitious and scheming men, ravenous for their share. If, then, they wish to repel this hungry and menacing throng, there is clearly only one course of action open to them: to renounce what attracts it. To dissolve the factions, they must necessarily abandon what unites them. It is by making power far too desirable in the eyes of ordinary men, by attaching to it enormous profits, and at the same time, bysurrounding it with distinctions and honors. Experience shows that the prestige attached to office, in countries where offices are not endowed, is more than sufficient to make them sought after. There is no profit in holding [109] public positions—especially high ones—in the United States, and yet they do not go unfilled. Let us therefore cease to make power a means of making a fortune, if we do not want it to remain the universal object of ambition—if we do not want it to perpetuate despotism and anarchy in our midst. It is by multiplying salaried positions, by gradually inflating salaries, that everything has been drawn into public service; men can only be drawn back to the tasks of private life by the opposite process. The level of salaries must be reduced, and the number of posts must be diminished; only compensation should be paid for carrying out necessary offices, and all useless functions must be abolished—that is, all those that fall outside the true functions of government, all those that exist solely to provide a job and a means of making one's fortune for those who fill them, all those created merely to support or defend abuses.

No doubt such a reform is not without its difficulties. There is resistance to overcome; all ambitions are united in defense of abuses; no faction wants power to be diminished, and the suppression of a [110] harmful or useless office may be as fiercely opposed by those who covet it as by those who hold it. Nevertheless, however formidable one may imagine these difficulties to be, they are not insurmountable; and a government that chose to undertake their removal would be sure, with a little energy and some tact, to succeed.

Consider first that there is no relation between the number of people whose interests a sound reform might injure and the number to whom it would be beneficial—between the number of friends it makes and the number of enemies it provokes. The ending of an abuse can alienate from the government only a few privileged or aspiring men of ambition; it will infallibly win over the esteem and affection of the public. It may even happen that it wins over the many who benefit from it without arming against itself the few whom it harms. There is such authority in obvious justice that those who suffer from it do not always have the courage to complain. We find it hard to believe, for instance, that if, with clear motives of economy, order, and public good, the government [111] resolved to eliminate a branch of the administration clearly detrimental to the country, there would be many among the employees affected by this measure who would dare take offense. If in 1814 the officers of the old army took umbrage at being sent home with half their pay, it was much less—justice requires this to be said—because they regretted losing their commands and their salary than because of the natural resentment they felt in seeing them handed over to others with no more claim than themselves. The same may be said of most officials dismissed since the Restoration. In general, if these removals stirred up so much irritation and bitterness, it was less due to the injury suffered than to the insult received. Had the reforms not seemed motivated by a regrettable spirit of preference and favoritism—had they appeared inspired by a sincere desire for the public good, a measure of compassion for the suffering of taxpayers, a wish to relieve them—they certainly would not have aroused such resentment. What stings is injustice; but there are few men [112] who cannot be brought to sacrifice their private interest to the clearly demonstrated interest of the public.

It even seems that this would be no great difficulty, provided that while working for the general good, some care is also taken for individual interests—if, while striking at abuses, one avoided wounding persons too cruelly. And this is a precaution that prudence and justice alike would recommend. However useless or even harmful certain offices may be, one cannot in good conscience condemn those who have spent a part of their lives carrying them out—who are no longer able to pursue another profession—to find themselves suddenly without a way of making a living, their families left in distress. There would be injustice and cruelty in this. If, in private professions, individuals suddenly rendered jobless by the advance of industry or the invention of new machines have at times received assistance, why should it not be the same in public service? Why, as government becomes simplified and improved, should we not support those whom the suppression of useless offices deprives of their livelihood? [113] The best way to make reforms easy is to disarm those they affect. If such wisdom had been shown at the start of the Revolution—if, in attacking certain abuses, the government had also made provisions for those who lived off them—we would be right in thinking that the Revolution would have had a few less obstacles to overcome.

It would therefore not be impossible, strictly speaking, to carry out the reform we propose without arousing too many outcries or provoking too much resistance. It would suffice, so to speak, to kill the abuses while letting the persons live—to eliminate useless offices while compensating, as needed, those who are stripped of them. In this way both claimants and incumbents would be kept at bay: the latter would consent to withdraw, having no grounds for complaint; the former would cease to covet what is no longer there. As the number and profitability of offices decreased, the administration would necessarily grow milder, and the number of the ambitious would diminish; and while the nation freed itself from despotism, the government would gradually shield itself from revolution.

[114]

Instead of this, what has been done? The abuses have been carefully spared, and severe measures have been taken against persons. Offices have been preserved; employees have been dismissed. The number and rewards of posts have been increased, and new individuals have been called to enjoy them. There was an old guard—it was pushed aside, and a new one was formed. There was an army too large to pay—we brought in Swiss troops, who are paid double. There were already ten times more officers than could be employed—a multitude of new officers was created, and they were given the posts of the old ones with higher salaries. There were many excess prefects and sub-prefects—a general purge doubled their number. There were too many judges—new judges were appointed. Too many administrators—new ones were created. The administrations were crowded with clerks—they were dismissed, and an even greater number were brought in. In short, everywhere persons were struck down, while disorders were respected and multiplied. Look at the administration left by Bonaparte; examine the general staffs, the administrative offices, the number [115] of posts, the level of salaries: all of this has been preserved, increased, exaggerated, pushed to the point of scandal. The only change is that these things are no longer held by the same people: the field has been improved, but it has passed into new hands.

It is easy to see what the consequences of such conduct must have been. Since the reform touched only people, it encountered invincible resistance that it would not have met had it targeted things. The men of the imperial government, seeing themselves stripped of office only to make way for men of the old regime, saw no reason to resign themselves to the sacrifice; instead of returning to private life, they stubbornly clung to the pathways of power, waiting on time and circumstance to reclaim them. Later, the men of the old regime, seeing that some of their posts were being taken away only to be handed back to men of the Empire, in turn saw no reason to allow themselves to be displaced in favor of their rivals. Instead of quietly enjoying the power that remained to them, they raised an [116] appalling outcry to recover what they had lost. Finally, the general public, feeling no relief at all from these shufflings of personnel; seeing that the imperial administration still weighed on them with all its force; seeing that despite a few improvements to the general forms of government, they remained strapped, harnessed, and burdened as under Bonaparte—and that the burden was perhaps even heavier—the general public, we say, had no strong reason to be pleased with the reforms that had been made. Instead of rallying to the ministry, they did everything in their power to rid themselves of the abuses it sought to preserve. The ministry, by directing its reforms only at individuals while preserving and accumulating the abuses, thus placed itself in the position of having to struggle constantly both against a faction and against the public. Now, this necessity will remain for as long as reforms target men instead of things; for as long as it insists on maintaining general staffs, sinecures, inflated salaries, and thousands of useless positions—for as long, in short, as it insists that political power remain a domain of activity. No faction will ever willingly relinquish that domain in favor [117] of another. Still less will the public ever allow any faction to enjoy it peacefully. If the ministry tries to fill it with the royalists, it will have the Bonapartists and the nation against it. If it tries to fill it with the Bonapartists, it will have the nation and the royalists against it. If it tries to fill it with a third party formed of both, it will have both factions and the public against it. If, to secure possession of it, it arms itself with laws of terror and resorts to violent measures, those measures will only make both the excluded faction and the public—upon whom the exploitation is carried out—more hostile. It clearly has only one way out of this state of conflict and danger: to ensure that there is no longer any such domain, to relinquish what the factions are fighting over and what the public refuses to grant. This single change in policy will necessarily bring about a highly favorable change in its situation. If, instead of taking a sinecure from a royalist to give it to a Bonapartist, it simply eliminates the sinecure, it is clear that none of the claimants can complain, and the public, in whose favor the reform is made, will have reason to be satisfied. Thus, it is not by changing factions that the government should [118] seek improvement, but by eliminating what divides the factions and alienates the public—by eliminating useless positions, reducing the profits of high but necessary offices, and making power appear not as a benefit, but as a burden, thereby changing both its character and its nature. In carrying out this reform, it will undoubtedly lose the support of the factions, but it will also free itself from their attacks; it will see the factions dissolve, and the public rally to it; and while it gains in strength, the nation will gain in wealth and in liberty.

D….R.

Notes↩

[1] See Volume VII, pages 1 to 79. (Editor: [CC??], “De la multiplication des pauvres, des gens à places, et des gens à pensions" CE T.7 (28 mar. 1818), pp. 1-79.)

[2] (Editor's Note) There is a revised section of this paragraph which has been added to the version of this article which appeared in Dunoyer’s Oeuvres, T. 3, p. 111. Dunoyer, Charles, Oeuvres de Dunoyer, revues sur les manuscrits de l'auteur, 3 vols., ed. Anatole Dunoyer (Paris: Guillaumin, 1870, 1885, 1886). It goes as follows: "The considerable mass of salaries assigned to the endowment of government, by continually increasing the class of individuals who devote themselves to the exercise of public functions, therefore makes inevitable, for that very reason, the indefinite multiplication of offices and the unlimited growth of burdens that weigh on all citizens. These consequences, in turn, have others still, which are no less worthy of attention. As power expands and grows heavier under the effects of a salaried system applied to the endowment of public offices, new reasons of a different kind are added to the first, compelling it to extend and strengthen itself even further, and to increase the burden of taxes—the product of which is the very source from which it draws its strength. Having degenerated into an exploitation of private fortunes, to the point that it takes on the character of an enterprise of legal plunder, government becomes indirectly—but inevitably—the primary cause of a thousand disorders, the repression of which then requires that it give a new degree of intensity to its action."

[3] Here is how the Minister of Finance expressed himself when presenting the 1818 budget to the King, in which ordinary expenditures exceeded those of the year 1817 by 18,847,633 francs: “I must declare to Your Majesty, it is only after having become convinced of the impossibility of carrying retrenchments and reforms any further that his ministry proposes this allocation. At the last session, the government had pledged to reduce expenditures and to go no further along the path of sacrifice than the point marked out by the interest of the state; that pledge has been scrupulously fulfilled.”

[4] M. Say, in his work entitled On England and the English, page 11 and following, reports from Colquhoun (On the Wealth of the British Empire) that in 1813, the total expenditures made by the English government amounted to the astonishing sum of 2,697 million francs. Add to this the 384 million already accounted for by the poor tax; add also the tithe paid to the clergy; add the local expenses, and you will see that the burdens borne annually by the English population far exceed three billion francs.

[5] History of the Wars of Religion, Volume I, Book IV, page 342.