FRÉDÉRIC BASTIAT,

The Law (1850):

The Students Edition (2025)

Frédéric Bastiat (1801-1850) |

|

[Created: 17 March, 2025]

[Updated: 19 April, 2025] |

Source

, The Law: The Students Edition. Translated, edited, and with Notes by David M. Hart (The Pittwater Free Press, 2025).http://davidmhart.com/liberty/FrenchClassicalLiberals/Bastiat/Books/1850-LaLoi/StudentEdition/Bastiat_TheLaw-StudentEdition.html

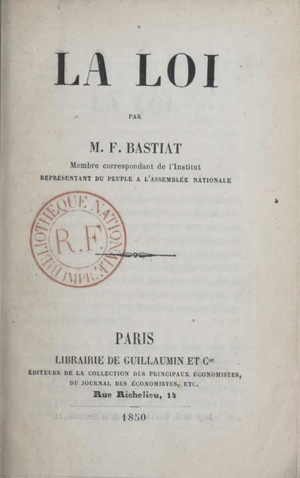

Frédéric Bastiat, La Loi. Par M. F. Bastiat. Membre correspondent de l'Institut. représentant du peuple a l'assemblée nationale. (Paris: Librairie de Guillaumin et Cie, 1850). Online. In facs. PDF and enhanced HTML.

Frédéric Bastiat, The Law: The Students Edition. Translated, edited, and with Notes by David M. Hart (The Pittwater Free Press, 2025).

See also the 1850 edition of the work in French in facs. PDF and enhanced HTML.

This book is part of a collection of works by Frédéric Bastiat (1801-1850).

Table of Contents

Editor's Introduction↩

(To come)

The Text↩

[3]

The Law perverted! [1] The Law, and along with it all the coercive powers [2] of the nation—The Law, I say, not only diverted from its purpose but applied to pursuing an aim directly opposed to it! The Law, becoming the tool of all forms of greed instead of being their restraint! The Law itself perpetrating the very injustice it was meant to punish! Certainly, this is a grave matter—if it is true—one that I must be allowed to bring to the attention of my fellow citizens.

We hold from God [3] the gift that encompasses all others for us: Life—physical, intellectual, and moral life.

But life does not sustain itself. He who gave it to us [4] left us with the task of maintaining it, developing it, perfecting it.

[4]

For this purpose, He endowed us with a set of marvelous faculties and placed us in an environment of diverse elements. It is through the application of our faculties to these elements that the phenomenon of assimilation, [5] of appropriation, takes place—by which life follows the course assigned to it.

Existence, our faculties, and assimilation—in other words, personhood, [6] liberty, and property—this is what man is.

One can say of these three things, [7] without any demagogic subtlety, that they are prior to and superior to all human legislation.

It is not because men have enacted Laws that personhood, liberty, and property exist. On the contrary, it is because personhood, liberty, and property preexist that men create Laws.

What, then, is the Law? As I have said elsewhere, it is the collective organization of the individual right to legitimate (self) defense.

Each of us certainly holds from nature, from God, [8] the right to defend his person, his liberty, and his property, since these are the three elements that constitute or preserve life—elements that complement one another and [5] cannot be understood separately. For what are our faculties if not an extension of our personhood, and what is property if not an extension of our faculties? [9]

If every man has the right to defend, even by force, his person, his liberty, and his property, then several men have the right to come together, to reach an agreement, and to organize a common (use of coercive) force to provide for this defensein a regular manner.

Thus, this collective right (to use force) has its principle, its justification, and its legitimacy in the individual's right (to do this), and the common (use of) force can rationally have no other purpose, no other task, than the (use of) force by isolated individuals which it replaces.

Therefore, just as the (use of) force by an individual cannot legitimately violate the person, the liberty, or the property of another individual, by the same reasoning, the common (use of) force cannot be legitimately used to destroy the person, the liberty, or the property of individuals or classes.

For this perversion of (the use of) force would, in one case as in the other, contradict our premises. Who would dare to say that (the use of) force was given to us not to defend our rights but to destroy the equal rights of our brothers? And if this is not true for each individual to use force acting in isolation, how could it be true of [6] the collective (use of) force, which is merely the organized combination of the (use of) force by isolated individuals?

Thus, if anything is evident, it is this: the Law is the organization of the natural right of legitimate (self) defense; it is the substitution of the collective use offorce for for that of individuals, in order to enable (people) to act within the limits where these forces have the right to act, to do what they have the right to do—to protect persons, Liberties, and property, to preserve each person's' rights, and in order to ensure the reign ofJUSTICE over us all.

And if a nation [10] were constituted on this basis, it seems to me that order would prevail in both deeds and ideas. It seems to me that such a people would have the simplest, most economical, least burdensome, least intrusive, least harmful, and the most just, and therefore most stable government imaginable, regardless of its political form.

For under such a regime, each person would fully understand that he would enjoy all the benefits as well as have all the responsibility for his ownexistence. As long as his person was respected, his labor free (of restrictions), and the fruits of his labor protected from unjust violation, no one would have any reason to take issue with the state. If we were content with our lot, we would not, it is true, have to thank it for [7] our successes; but if we were not content, we would no more blame the state for our misfortunes than our farmers blame it for hail or frost. We would only know that it was the invaluable blessing of SECURITY.

One may further argue that, thanks to the non-intervention of the state in private affairs, our needs and the satisfaction of those needs [11] would develop in their natural order. One would not see poor families seeking a literary education before having bread. One would not see cities swelling in size at the expense of the countryside, or the countryside at the expense of cities. One would not see these great displacements of capital, labor, and population, causedby the passing of laws [12] —displacements that render the very sources of existence so uncertain and precarious, and thereby greatly increase the demand placed on governments to be be responsible for it.

Unfortunately, the Law has not remained confined to its proper role. Worse still, it has not merely strayed into unimportant or debatable matters. It has done worse: it has acted contrary to its own end; it has destroyed its own purpose; it has worked to destroy the very justice it was meant to uphold, to erase the limit it was meant to enforce between rights; it [8] has put the collective use of force at the service of those who seek to exploit, without risk (to themselves) and without scruple, the person, the liberty, or the property of others; it has converted plunder into a right in order to protect it, and (converted) legitimate (self) defense into a crime in order to punish it.

How has this perversion of the Law come about? What have been its consequences?

The Law has been perverted under the influence of two very different causes: thoughtless egoism [13] and false philanthropy. [14]

Let me speak about the first one:

To preserve and develop oneself—this is the common aspiration of all men, so much so that if each person enjoyed the free exercise of his faculties and the free disposal of the things they produced, social progress would be constant, uninterrupted, and unerring.

However, there is another tendency which is just as common, namely to live and grow at the expense of others whenever possible. This is not a reckless accusation born of a bitter or pessimistic mind. History bears witness to it through endless wars, migrations of people, oppression by priests, [15] the universal practice of slavery, industrial fraud, [9] and the monopolies with which the annals of history are filled. [16]

This disastrous tendency originates from the very constitution of man, from that primitive, universal, and overwhelming impetus that drives him toward well-being and makes him flee from pain.

Man can only live and enjoy life by means of constant (process) of assimilation and appropriation (of the things around him)—that is, by the constant application of his faculties to (other) things, or through labor. From this comes (the need for) property.

But in reality, he can also live and enjoy by assimilating or appropriating the product of his fellow man's faculties. From this comes plunder.

Now, since labor itself is painful, and man is naturally inclined to avoid pain, it follows—as history proves—that wherever plunder is less burdensome than labor, it prevails. It prevails despite religion, despite morality, which, in such a case, are powerless to prevent it. [17]

When, then, does plunder cease? When it becomes more burdensome, more dangerous than labor.

It is quite evident that the purpose of the Law should be to use the collective use of force as a powerful obstacle against this disastrous tendency (of men)—that it should take the side of property against plunder.

[10]

But the Law is most often made by one man or by a class of men. And since the Law cannot exist without the sanction, without the support of an overwhelming (coercive) force, it inevitably places this force in the hands of those who make the laws. [18]

This inevitable phenomenon, combined with the harmful tendency we have just observed in the human heart, explains the nearly universal perversion of the Law. We can understand how, instead of restraining injustice, it becomes a tool—and the most invincible tool—of injustice. We can understand how, according to the power of the legislator, it destroys, for his benefit and to varying degrees among the rest of mankind, (the right to) personhood be means of slavery, liberty by means of oppression, and property by means of plunder.

It is in the nature of man to react against the injustice he suffers. Therefore, when plunder is organized by the Law for the benefit of the classes that make it, all the plundered classes [19] seek, by peaceful or revolutionary means, to have a say in the making of the Laws. These classes, depending on their level of enlightenment, may pursue two very different objectives when they strive to conquer their political rights: [20] either they wish to put an end to legal plunder, [21] [11] or they aspire to take part in it.

Woe, three times woe, to the nations where this latter thought dominates the masses at the moment they seize legislative power!

Up until now, legal plunder has been exercised by the few upon the many, as seen in nations where the right to pass laws is concentrated in the hands of a few. [22] But now it has become universal, and an equilibrium is being sought in universal plunder. [23] Instead of eliminating injustice from society, it is being generalized. As soon as the (politically) disinherited classes regain their political rights, their first thought is not to free themselves from plunder (that would presuppose a level of enlightenment they cannot yet have), but to organize a system of retaliation against the other classes and, ultimately, against themselves—as if, before the reign of justice can arrive, a cruel retribution must strike them all, some for their injustice, others for their ignorance. [24]

No greater transformation and no greater misfortune [12] could be introduced into society than this: the Law turned into a tool of plunder.

What are the consequences of such a disturbance? [25] It would take volumes to describe them all. [26] Let us be content with pointing out the most striking.

The first is that it erases from people's consciences the notion of justice and injustice.

No society can exist if respect for the Law does not prevail to some degree. But the surest way for the Law to be respected is for it to be respectable. When the Law and Morality contradict each other, the citizen finds himself in the cruel dilemma of either losing his moral sense or losing his respect for the Law—two equally great misfortunes, between which it is difficult to choose.

It is so natural for the Law to ensure that justice prevails that, in the minds of the masses, Law and justice are one and the same thing. We all have a strong tendency to regard what is legal as (also) legitimate—to such an extent that many people mistakenly derive all their notions of justice from the Law itself. Thus, as soon as the Law decrees and enshrines plunder, plunder appears just and sacred in the eyes of many consciences. Slavery, [13] (trade) restrictions, monopoly—all find defenders not only among those who benefit from them but also among those who suffer from them. [27] Try to raise doubts about the morality of these institutions. "You are," they will say, "a dangerous innovator, a utopian, [28] a theorist, someone who has a contempt for the law; you are shaking the very foundation upon which society rests." If you teach a course in morality or political economy, there will be official bodies ready to petition the government with the wish:

"Let science henceforth be taught, no longer from the sole perspective of Free Trade (of liberty, property, and justice), as has been the case until now, but also, and above all, from the perspective of the facts and legislation (contrary to liberty, property, and justice) that governs French industry."

"Let the professors, with chairs which are funded by the Treasury, [29] rigorously abstain from the slightest attack on the respect due to existing laws, etc." [30]

Thus, if there exists a law that sanctions slavery or monopoly, oppression, or [14] plunder in any form whatsoever, it must not even be mentioned, for how can one speak of it without undermining the respect it inspires? Even more, morality and political economy must be taught from the perspective of this Law—that is to say, on the assumption that it is just merely because it is the Law.

Another effect of this deplorable perversion of the Law is that it grants an exaggerated importance to political passions and struggles, and, in general, to politics itself.

I could prove this proposition in a thousand ways. I will limit myself, by way of example, to connecting it to the topic that has recently occupied all minds: universal suffrage. [31]

Regardless of what the adherents of Rousseau’s school may think—a school that claims to be very advanced but which I believe has regressed twenty centuries—universal suffrage (taking the term in its strictest sense) is not one of those sacred dogmas about which examination and even doubt are considered crimes.

It is open to serious objections.

First of all, the word "universal" hides a gross sophism. [32] France has thirty-six million inhabitants. For suffrage to be truly universal, it would have to be recognized for thirty-six million [15] voters. Even under the broadest system of voting, it is recognized only for nine million. Three out of four people are therefore excluded—and, what is more, they are excluded by that fourth person. On what principle is this exclusion based? On the principle of incapacity. Thus, universal suffrage means: universal suffrage of those who are capable. This leaves the factual question: who are the capable? Are age, sex, and criminal record the only signs by which incapacity can be recognized?

If one examines this closely, one quickly perceives the reason why the right to vote is based on the presumption of capability. The broadest system differs from the most restrictive only in its assessment of the signs by which this capability is recognized—this is not a difference of principle, but of degree.

This reason is that the voter does not legislate only for himself but for everyone.

If, as the republicans of the Greek and Roman persuasion claim, the right to vote were as inherent to us as life itself, it would be unjust for adults to prevent women and children from voting. Why are they prevented? Because they are presumed to be incapable. And why is incapacity a reason for exclusion? Because the voter does not bear alone the responsibility for his vote; [16] because each vote binds and affects the entire community; because the community has the right to require certain guarantees regarding the acts upon which its well-being and existence depend.

I know what could be said in response. I also know what could be replied in turn. This is not the place to go into such a controversy in detail. What I wish to point out is that this very controversy (as well as most political questions), which agitates, inflames, and unsettles nations, would lose almost all its importance if the Law had always been what it ought to be.

Indeed, if the Law confined itself to ensuring respect for (the rights of) all persons, all Liberties, and all Properties—if it were nothing more than the organization of the individual right of legitimate (self-)defense, the obstacle, the restraint, the punishment set against all kinds of oppressions and all kinds of plunder—do we think that we would argue so fiercely, as citizens, about the question of whether suffrage should be more or less universal? Do we think it would threaten the greatest of all good, public peace? Do we think that the (politically) excluded classes would not patiently wait their turn? Do we think that the (politically) included classes would be very jealous of their privilege? And is it not [17] clear, since their (self-)interest would be identical and common (to all), that one group could act without significant inconvenience on behalfthe others?

But let this disastrous principle be introduced—let it be admitted that, under the pretext of (providing) organization, regulation, protection, or encouragement, the Law may take from some to give to others, take wealth acquired by all classes to increase that of a single class—sometimes that of the farmers, sometimes that of the manufacturers, merchants, shipowners, artists, or actors—oh! then, certainly, there is no class that will not claim, with good reason, (the right) to lay its hands on the Law; that will not fiercely demand its right to vote and to be elected; that will not overthrow society rather than be denied these privileges. Even beggars and vagrants will prove to you that they have undeniable claims. They will say to you:

"We never buy wine, tobacco, or salt without paying taxes, [33] and part of that tax is allocated by legislation in bonuses and subsidies to men richer than us. Others use the Law to artificially raise the prices of bread, meat, iron, and cloth. Since everyone exploits the Law for their benefit, we too want to exploit it. We want to extract from it the right to public assistance, [18] which is the poor man's share of plunder. To do this, we must be voters and legislators so that we can organize charity on a large scale for our class, just as you have organized protection on a large scale for yours. Do not tell us that you will provide our share for us, that you will throw us, as Mr. Mimerel suggests, [34] a sum of 600,000 francs as if it were a bone to gnaw on. We have other demands, and in any case, we want to vote on it for ourselves just as the other classes have voted on it for themselves!"

What response can be made to this argument? Yes, as long as it is admitted in principle that the Law may be diverted from its true mission—that it may violate property instead of protecting it—every class will seek to make the Law, either to defend itself against plunder or to organize it for its own benefit. The political question will always be prejudicial, predominant, and all absorbing; in short, men will fight at the doors of the Legislative Palace. [35] The struggle will be no less fierce within. To be convinced of this, it is hardly necessary to look at what happens in the Chambers of France and England; it is enough to understand how the question is framed.

Is it necessary to prove that this odious [19] perversion of the Law is a constant source of hatred and discord, [36] even capable of leading to social disorganisation? [37] Look at the United states. It is the (one) country in the world where the Law remains most true to its role—guaranteeing each person their liberty and property. Thus, it is the (one) country in the world where social order appears to rest on the most stable foundations. Yet even in the United states, there are two issues—and only two—that, since the nation’s founding, have repeatedly threatened political stability. And what are these two issues? Slavery and tariffs [38] —precisely the only two issues where, contrary to the general spirit of the republic, the Law has taken on the character of a plunderer. Slavery is a legally sanctioned violation of the rights of the person. protectionism is a violation of the right to propertyperpetrated by the Law. And certainly, it is remarkable that, among so many other debates, this dual legal scourge—this sad inheritance from the Old World—is the only one capable of bringing about, and perhaps ultimately causing, the rupture of the Union. Indeed, one cannot imagine a more significant fact within a society than this: the Law has become a tool of injustice. And if this fact generates such momentous consequences in the United states, where it is merely an [20] exception, what must it be like in Europe, where it is a principle, a system (of government)?

M. de Montalembert, [39] echoing the idea behind a famous proclamation by M. Carlier, declared: "We must wage war on socialism." [40] And by socialism, we must believe, according to the definition of M. Charles Dupin,[41] that he meant plunder.

But which kind of plunder was he referring to? For there are two kinds. There is extra-legal plunder [42] and legal plunder. [43]

As for extra-legal plunder—the kind commonly called theft or fraud, which is defined, anticipated, and punished by the Penal Code—I truly do not think it can be dignified with the name of socialism. This is not the type of plunder that systematically threatens the foundations of society. Besides, the war against this kind of plunder did not wait for the signal from M. de Montalembert or M. Carlier. It has been waged since the beginning of time; France had already addressed it long before the February Revolution, long before the rise of socialism, through an entire apparatus [44] of magistrates, police, gendarmes, prisons, penal colonies, and scaffolds. It is the Law itself that conducts this war, and what I would wish is [21] for the Law to always maintain this stance against plunder.

But such is not the case. The Law sometimes takes the side of plunder. Sometimes it even carries it out with its own hands, sparing the beneficiary [45] the shame, the danger, and the guilt (of doing it themselves). Sometimes it places the entire apparatus of the magistrates, police, gendarmes, and prisons at the service of the plunderer, treating as a criminal the plundered person who defends himself. In a word, there is legal plunder, and it is undoubtedly this kind that M. de Montalembert speaks of.

Such plunder may be only an exceptional stain on a nation’s legislation, and in that case, the best course of action—without excessive declamations and lamentations—is to erase it as soon as possible, despite the outcry of those with vested interests. How can it be recognized? It is quite simple. One must examine whether the Law takes from some individuals what belongs to them in order to give to others what does not belong to them. One must examine whether the Law commits, for the benefit of one citizen and to the detriment of others, an act that this citizen could not perform himself without committing a crime. Hasten to repeal such a Law; it is not only an injustice—it is a fertile source of (additional) injustices, for it invites retaliation. And if you do not take care, the exceptional case will spread, multiply, [22] and become systematic. No doubt, the beneficiaries will cry out in protest; they will invoke the rights they have already acquired. They will say that the state owes them protection and support for their industry. They will argue that it is good for the state to enrich them because, being wealthier, they will spend more and thus distribute wages like rain upon the poor workers. [46] Beware of listening to such sophists, for it is precisely by systematizing such arguments that legal plunder itself becomes systematic.

This is what has happened. The illusion of the day is to enrich every class at the expense of all the others—to generalize plunder under the pretext of organizing it.Now, legal plunder can be carried out in an infinite number of ways. Hence the infinite number of organizational schemes: tariffs, protectionism, subsidies, grants, bounties, progressive taxation, free education, the right to work, [47] the right to profit, the right to wages, the right to public assistance, the right to (be given) tools, interest-free credit, [48] etc., etc. And it is the sum of all these schemes, in what they have in common—legal plunder—that takes the name of socialism. [49]

Now, what kind of war do you want to wage against socialism, defined thus as a body of ideas? Surely, it (has tobe) a war of ideas? [50] If you find [23] these ideas are false, absurd, revolting—refute them. That will be all the easier for you, the more false, absurd, and revolting they are. Above all, if you wish to be strong, begin by removing from your own legislation all traces of socialism that may have crept into it—and that task is not a small one. [51]

M. de Montalembert has been accused of wanting to use brute force against socialism. [52] This is an accusation from which he should be absolved, for he explicitly stated: "We must wage war on socialism in a manner that is compatible with law, honor, and justice." [53]

But how does M. de Montalembert not see that he is caught in a vicious circle? You wish to oppose socialism with the Law? But socialism itself invokes the Law! It does not aspire to extra-legal plunder—it seeks legal plunder. It aims, like all monopolists, to make the Law its tool. And once it has the Law on its side, how do you expect to use the Law against it? How do you intend to bring it under the jurisdiction of your courts, your gendarmes, your prisons?

So what do you do? You want to prevent socialism from getting its hands on the making of laws. [54] You [24] want to keep it outside the Legislative Palace. But you will not succeed, I dare predict, as long as inside the Assembly laws are being passed based on the principle of legal plunder. This is too unjust; it is too absurd.

This question of legal plunder must absolutely be resolved, and there are only three possible solutions:

- That the few plunder the many.

- That everyone plunders everyone.

- That no one plunders anyone.

Partial plunder, universal plunder, or the absence of plunder—one must choose.[55] The law can only pursue one of these three outcomes.

Partial plunder was the prevailing system as long as suffrage was partial [56] —a system to which some now wish to return in order to prevent the rise of socialism.

Universal plunder is the system we were threatened with when suffrage became universal, [57] as the masses conceived the idea of making laws along the same principlesas the legislators who preceded them.

The absence of plunder is the principle of justice, peace, order, stability, conciliation, and common sense, which I will proclaim with all the strength—alas, far too insufficient—of my lungs, until my last breath. [58]

And, sincerely, can anything else be asked [25] of the Law? The Law, having force as its necessary sanction, can it be reasonably employed for anything other than guaranteeing each person their rights? I challenge anyone to take it outside this circle without turning it—and consequently, without turning the use of force—against (their) rights. And since this is the most disastrous, the most illogical social disturbance imaginable, [59] it must be recognized that the long-sought solution to the social problem is contained in these simple words: THE LAW IS ORGANIZED JUSTICE.

Now, let us be clear: organizing justice by means of the Law, that is to say, by means of (the public use of) force, excludes the idea of organizing, by Law or by force, any kind of human activity (such as) labor, charity, agriculture, commerce, industry, education, fine arts, religion; for it is impossible for any of these secondary organizations (organised in this way) not to destroy the (primary and) essential organization (not based upon the use of force). Indeed, how can we imagine force being used against the liberty of the citizens without infringing upon justice, without acting against its own purpose?

Here, I come up against the most popular prejudice of our time. It is not enough that the Law be just; it must also be philanthropic. It is not enough that it guarantees each citizen the free and harmless exercise [26] of their faculties, in pursuit of their physical, intellectual, and moral development; it is required that it directly spread well-being, education, and morality across the nation. This is the seductive aspect of socialism.

But, I repeat, these two tasks of the Law contradict each other. A choice must be made. A citizen cannot be both free and not free at the same time. M. de Lamartine [60] once wrote to me: "Your doctrine is only half of my program; you have stopped at liberty, while I go on as far as fraternity." [61] I replied: "The second half of your program will destroy the first." And, indeed, I find it utterly impossible to separate the word fraternity from the word voluntary. I find it utterly impossible to conceive of legally enforced fraternity without legally destroying liberty and legally trampling justice underfoot. [62]

Legal plunder has two roots: one, as we have just seen, lies in Human egoism; the other in false Philanthropy.

Before going further, I believe I must clarify my use of the word plunder.

I do not take it, as is too often done, in a vague, indeterminate, approximate, or metaphorical sense. I use it in a strictly scientific sense, as expressing [27] the idea opposed to that of (the right to) property. When a portion of wealth passes from the person who has acquired it, without their consent and without compensation, to someone who has not created it—whether by force or by fraud—I say that the right to property has been violated, that there (has been an act of) plunder. I say that this is precisely what the Law should repress everywhere and always. And if the Law itself commits the act it ought to repress, I say that there is still plunder, and even, socially speaking, with aggravated circumstances. Only in this case, it is not the one who benefits from the plunder who is responsible; it is the Law, it is the legislator, it is society itself, and this is what makes it politically dangerous.

It is unfortunate that this word carries a suggestion of something offensive. [63] I have searched in vain for another, for at no time, and less today than ever, would I wish to introduce an inflammatory term into our disputes. So, whether one believes it or not, I declare that I do not intend to question the intentions or morality of anyone. I am attacking an idea that I believe to be false, a system that seems unjust to me, and so far removed from personal motives that each of us benefits from it unwittingly and suffers from it unknowingly. One must write under the influence of party spirit or fear to [28] question the sincerity of (those who defend) protectionism, socialism, and even communism, which are merely one and the same plant at three different stages of its development. [64] All that can be said is that plunder is more visible, by its partiality, in protectionism; [65] by its universality, in communism; from which it follows that of the three systems, socialism is still the most vague, the most indecisive, and consequently the most sincere.

Be that as it may, to acknowledge that legal plunder has one of its roots in false philanthropy is evidently to put (the) intentions (of its advocates) beyond reproach.

With this understood, let us examine the value, origin, and consequences of this popular aspiration that seeks to achieve the general good through general plunder.

Socialists tell us: Since the Law [29] organizes justice, why should it not organize labor, education, and religion?

Why? Because it cannot organize labor, education, and religion without disorganizing justice.

Consider that the Law is (the use of) force, and that consequently, the domain of the Law cannot legitimately extend beyond the legitimate domain of (the uses of) force.

When the Law and (the uses of) force confine a man within (the circle of) justice, they impose nothing but a mere negation. They impose only the abstention from harming others. They do not infringe upon his personhood, his liberty, or his property. They merely safeguard the personhood, liberty, and property of others. They remain defensive; they defend the equal rights of all. They fulfill a task whose harmlessness is evident, whose utility is palpable, and whose legitimacy is indisputable.

This is so true that, as one of my friends pointed out to me, to say that the purpose of the Law is to make justice reign is to use an expression that is not strictly accurate. It should be said: The purpose of the Law is to prevent Injustice from reigning. Indeed, it is not justice that has an independent existence; it is Injustice. The former results from the absence of the latter.

[30]

But when the Law—through its necessary agent, (the use of) force—imposes a way of working, a method or subject of education, a (particular) faith or a form of worship, it no longer acts negatively; it acts positively upon men. It substitutes the legislator’s will for their own, the legislator’s initiative for their own initiative. They no longer need to confer with others, to make choices, or to plan for the future; the Law does all of this for them. Their minds become a useless piece of furniture; they cease to be men; they lose their personhood, their liberty, and their property.

Try to imagine a form of labor imposed by force that is not a violation of liberty; a transfer of wealth imposed by force that is not a violation of liberty property. If you cannot, then acknowledge that the Law cannot organize labor and industry without organizing Injustice.

When a writer surveys society from the depths of his study, he is struck by the spectacle of inequality before him. He laments the suffering endured by so many of our brethren, suffering made all the more distressing by the stark contrast between luxury and opulence.

Perhaps he should ask himself whether such a social condition [31] is not the result of past (acts of) plunder carried out through conquest and new (acts of) plunder carried out by means of the Law. [66] He should ask himself whether, given that all men aspire to well-being and improvement, the rule of justice alone is not sufficient to bring about the greatest possible progress and the greatest degree of equality—compatible, of course, with the individual responsibility that God has put aside as the fair reward for virtue and vice.

But he does not even consider this. His thoughts turn instead to schemes, arrangements, and organizations which are artificial and imposed by law. [67] He seeks the remedy in the perpetuation and exaggeration of the very cause of the problem.

For, apart from justice—which, as we have seen, is a true negation—is there a single one of these "legal arrangements" that does not contain the principle of plunder?

You say: “There are men who lack wealth,” and you turn to the Law. But the Law is not a breast that fills itself, nor are its milk-bearing ducts able to draw nourishment from anywhere but society. Nothing enters the public treasury for the benefit of a particular citizen or a class except what other citizens and other classes have been forced to put there.If each one [32] withdraws only the equivalent of what he has contributed, then indeed your Law is not plunderous—but it also does nothing for those who lack wealth, nor does it promote equality. The Law can only be a tool of equalization if it takes from some to give to others, and in that case, it is a tool of plunder.[68] Consider from this perspective tariff protection, incentive bonuses, the right to a profit, the right to a job, the right to public assistance, the right to state-funded education, progressive taxation, free credit, and state-sponsored workshops [69] —you will always find, at their core, legal plunder, organized Injustice.

You say: “There are men who lack education,” and you turn to the Law. But the Law is not a torch that radiates its own light. It hovers over a society in which there are men who know things and men who do not, citizens who need to learn and others who are willing to teach. The Law can only do one of two things: either to allow this type of transaction to occur freely, to allow this kind of need to be satisfied freely, or to force the wills of some by taking from them the means to pay teachers who will then educate others free of charge. But in this second case, it cannot avoid [33] infringing upon (the rights of) liberty and property—that is to say Legal plunder.

You say: “There are men who lack morality or religion,” and you turn to the Law. But the Law is force, and is it necessary for me to say how violent and absurd it is to attempt to introduce force into such matters?

After all this effort and all this system building, it seems that socialism, however indulgent it is toward itself, cannot help but recognize the monster which is legal plunder. But what does it do? It cleverly disguises it from all eyes—including its own—under seductive names like fraternity, solidarity, organization, and association. [70] And because we demand nothing more from the Law than justice, because we insist upon nothing but justice, it assumes that we reject fraternity, solidarity, organization, and association, and hurls at us the epithet of individualists.

Let it be known, then, that what we reject is not natural organization but forced organization. [71]

It is not free association, but the forms of association that it seeks to impose upon us.

It is not spontaneous fraternity, but legal fraternity.

[34]

It is not providential solidarity, but artificial solidarity, which is merely an unjust displacement of responsibility. [72]

Socialism, like the old politics from which it springs, confuses government with society. That is why, every time we refuse to allow something to be done by the government, it concludes that we do not want that thing to be done at all. We reject state-controlled education; therefore, we are against education. We reject a state religion; therefore, we are against religion. We reject state-enforced equality; therefore, we are against equality, and so on. It is as if it accused us of wanting people to starve simply because we refuse to have the state grow wheat.

How could such a bizarre idea have taken hold in the political world—the idea of getting things from the Law which are not there: "the good" (in the broad sense of the term), wealth, science, religion?

Modern writers, particularly those of the socialist school, base their various theories on a common assumption—one that is undoubtedly the strangest, the most arrogant, ever conceived in the human mind.

[35]

They divide humanity into two parts. The entirety of mankind, minus one, forms the first; the writer himself, alone, forms the second—and is by far the most important.

Indeed, they begin by assuming that men do not carry within themselves any principle of action [73] or means of making judgements; that they lack initiative; that they are inert matter, passive molecules, atoms without spontaneity—at best, a form of vegetation indifferent to its own mode of existence, [74] susceptible to being shaped into an infinite number of more or less symmetrical, artistic, and perfected forms by an external will and hand. [75]

Then, without hesitation, each of them assumes that he himself—under the titles of organizer, prophet, legislator, instructor, founder—is that very will and hand, that universal motive force, [76] that creative power whose sublime mission is to gather together into society these scattered materials that are men.

Starting from this premise, just as a gardener, according to his whim, prunes his trees into pyramids, parasols, cubes, cones, vases, espaliers, distaffs, or fans, so too does each socialist, following his own fantasy, shape poor humanity into groups, series, centers, [36] sub-centers, cells, social workshops, harmonic or contrasting collectives, etc., etc. [77]

And just as the gardener needs axes, saws, pruning knives, and shears to shape his trees, so too does the writer need forces that he can find only in the Law: customs laws, tax laws, welfare laws, education laws.

It is so true that socialists view humanity as mere material for making various social combinations that, ifby chance they are not entirely sure of the success of these combinations, they at least demand a small segment of humanity as material for experimentation. We know how popular the idea of testing every system has become among them, and we have even seen one of their leaders seriously request that the Constituent Assembly grant him a commune, [78] along with all its inhabitants, to conduct his experiment. [79]

This is how every inventor first builds a small prototype before creating the full-sized machine. This is how the chemist sacrifices a few reagents, how the farmer sacrifices a few seeds and a corner of his field to test a new idea. [80]

But what an immeasurable distance separates the gardener from his trees, the inventor from his machine, the chemist from his reagents, the farmer from his seeds! … Yet the socialist, [37] in all sincerity, believes that the same distance separates him from humanity.

It is no wonder that the writers of the nineteenth century regard society as an artificial creation, the product of the genius of the legislator.

This idea, a product of classical education, has dominated the minds of all the great thinkers and writers of our country. [81]

All have perceived the same relationship between humanity and the legislator as that which exists between clay and the potter.

Furthermore, if they have conceded that man possesses within himself a principle of action and a principle of judgement, they have also thought that, in this, God has given him a disastrous giftin that humanity, under the influence of these two driving forces, tends inexorably toward its own degradation. They have assumed as a fact that, left to its own devices, humanity would concern itself with religion only to descend into atheism, with education only to sink into ignorance, with labor and trade only to perish in poverty.

Fortunately, according to these same writers, there exist a few men—called rulers and legislators—who have received from heaven not only [38] for themselves, but for all others, entirely opposite tendencies.

While humanity tends toward Evil, they tend toward Good; while humanity marches into darkness, they aspire to the light; while humanity is drawn toward vice, they are drawn toward virtue. And, having established this, they demand the use of force so that they may substitute their own tendencies for those of the entire human race. [82]

It takes nothing more than opening a random book on philosophy, politics, or history to see how deeply rooted this idea is in our country—this idea, the offspring of classical studies and the progenitor of socialism—that humanity is inert matter receiving from government its life, its organization, its morality, and its wealth; or worse still, that humanity, if left to itself, tends toward its own ruin and is stopped only by the mysterious hand of the legislator. Everywhere, classically inspiredconventional thinking shows us that, standing behind passive society, is an occult power that, under the names of Law, legislator, or, more conveniently and vaguely, “one,”[83] moves humanity, animates it, enriches it, and adds a moral sense to it.

BOSSUET. [84]

"One of the things that THEY (who?) [85] most strongly impressed upon the minds of the Egyptians was love of country... It was not permitted to be useless to the state; the Law assigned each person their profession, which continued from father to son. One could neither have two professions nor change from one to another... But there was one occupation that had to be common to all: the study of laws and wisdom. Ignorance of religion and the governance of the country was excused in no condition. Moreover, each profession had its designated district (assigned by whom?)... Among all the good laws, the best was that everyone was nurtured (by whom?) with the spirit of observing them... Their Mercuries filled Egypt with marvelous inventions and left it with hardly anything unknown that could make life comfortable and peaceful." [86]

Thus, according to Bossuet, men derive nothing from themselves: patriotism, wealth, activity, wisdom, inventions, agriculture, sciences—all came to them through the operation of laws or kings. It was only a matter of them (the people)letting them (the rulers) do their job. [87]. This reaches the point where, when Diodorus accused the Egyptians of rejecting combat and music, Bossuet refuted him. How could that be possible, he asked, since these arts had been invented by Trismegistus? [88]

The same was true for the Persians:

[40]

"One of the first duties of the prince was to make agriculture flourish... Just as there were officials responsible for leading armies, there were also those appointed to oversee rural labor... The respect inspired among the Persians for royal authority reached the level of excess." [89]

Even the Greeks, though full of intelligence, were no more the masters of their own destiny than dogs or horses—so much so that, left to themselves, they would not have risen to even the simplest games. In the classical tradition, it was an accepted belief that everything came to the people from outside sources.

"The Greeks, naturally full of wit and courage, had been cultivated early on by Kings and colonies from Egypt. From them, they had learned physical exercises, running on foot, on horseback, and in chariots... The best thing the Egyptians had taught them was to make themselves docile, to allow themselves to be shaped by laws for the public good." [90]

FÉNELON. [91]

Raised in the study and admiration of antiquity and a witness to the power of Louis XIV, Fénelon could hardly escape the idea that humanity is passive, and that its misfortunes as well as its prosperity, its virtues as well as its [41] vices, result from external action exerted upon it by the Law or by the one who enacts it. Thus, in his utopian Salente,[92] he places men—their interests, faculties, desires, and property—entirely at the discretion of the legislator. In any matter, they never judge for themselves; it is always the Prince who decides. The nation is nothing but formless material, and the Prince is its soul. It is within him that thought, foresight, the principle of all organization, all progress, and therefore all responsibility reside.

To prove this assertion, I would have to transcribe the entire tenth book of Télémaque. I refer the reader to it and will content myself with citing a few passages, taken at random, from this famous poem—one that, in all other respects, I am the first to acknowledge as remarkable.

With that astonishing credulity characteristic of classical thinkers, Fénelon, despite all reasoning and factual evidence, accepts as truth the universal happiness of the Egyptians—and attributes it, not to their own wisdom, but to that of their Kings.

"We could not cast our eyes upon either riverbank without seeing opulent cities, country homes pleasantly situated, fields [42] that, year after year, yielded golden harvests without ever lying fallow; meadows full of livestock; laborers burdened by the weight of the fruits that the earth poured forth from her bosom; shepherds whose flutes and reed pipes echoed sweet sounds throughout the valleys. ‘Happy,’ said Mentor, ‘is the people governed by a wise King!’" [93]

"Then Mentor pointed out to me the joy and abundance spread throughout the Egyptian countryside, where there were said to be as many as twenty-two thousand towns. He admired the good governance of the towns; justice exercised in favor of the poor against the rich; the excellent education of children, who were raised in obedience, hard work, sobriety, and love for the arts and letters; the strict adherence to all religious ceremonies; the selflessness, ambition for honor, fidelity toward men, and fear of the gods that every father instilled in his children. He never tired of admiring this beautiful order. ‘Happy,’ he said to me, ‘is the people governed in this way by a wise King!’" [94]

Fénelon paints an even more idyllic picture of Crete. Then, through the voice of Mentor, he adds:

"Everything you see on this marvelous island is the fruit of Minos’s laws. The education he [43] provided to children made their bodies strong and robust. From an early age, they were accustomed to a simple, frugal, and laborious life; it was assumed that any pleasure weakened both body and mind. They were never offered any other satisfaction than that of becoming invincible through virtue and acquiring great glory... Here, three vices that go unpunished among other people are strictly punished: ingratitude, deceit, and greed. As for ostentation and luxury, they never need to be suppressed, for they are unknown in Crete... There are neither precious furnishings nor magnificent garments, neither lavish feasts nor gilded palaces." [95]

Thus, Mentor prepares his pupil to mold and manipulate the people of Ithaca at his will—and, for greater assurance, provides him with an example in Salente.

This is how we receive our first political lessons. We are taught to treat men much like Olivier de Serres [96] teaches farmers to treat and mix soils.

MONTESQUIEU. [97]

"To maintain the spirit of commerce, all laws must favor it; these same Laws, through their provisions, must divide fortunes as commerce increases them, ensuring that every poor citizen reaches a level of sufficient [44] comfort to be able to work like the others, and that every wealthy citizen remains in such mediocrity that he must work to maintain or acquire wealth..." [98]

Thus, the Laws regulate all fortunes.

"Although real equality is the soul of a democracy, it is so difficult to establish that an extreme precision in this regard would not always be appropriate. It is sufficient to establish a property qualification that reduces or fixes differences at a certain level. After that, it is up to specific laws to, so to speak, equalize inequalities through the burdens they impose on the rich and the relief they grant to the poor..." [99]

This is, yet again, the equalization of wealth by law—by (the use of) force.

"There were two types of republics in Greece. Some were military, like Sparta; others were commercial, like Athens. In some, THEY wanted citizens to be idle; in others, THEY sought to cultivate a love for labor."

"I ask that people pay close attention to the extent of the genius required of these legislators, who, by defying all established customs and blending together all virtues, demonstrated their wisdom to the world. [45] Lycurgus, mixing theft with the spirit of justice, the harshest slavery with extreme liberty, the most atrocious sentiments with the greatest moderation, brought stability to his city. He seemed to strip it of all resources—arts, commerce, money, fortifications. There, ambition existed without hope of personal gain; natural human sentiments were present, yet one was neither child, husband, nor father; even modesty was taken away from chastity. It was through this path that Sparta was led to greatness and glory..."

"This extraordinary phenomenon that was seen in the institutions of Greece has also appeared in the dregs and corruption of our modern times. An honest legislator has formed a people where probity seems as natural as bravery among the Spartans. Mr. Penn [100] is a true Lycurgus, and although the former pursued peace while the latter pursued war, they are similar in the unique path they have set for their people, in the authority they have exerted over free men, in the prejudices they have overcome, in the passions they have subdued."

"The example of Paraguay [101] can provide another case. Some have criticized the Society that sees the pleasure of ruling as the sole good in life; but it will always be admirable to govern men by making them happier..."

"Those who wish to establish similar institutions [46] will adopt the communal ownership of property from Plato’s Republic, the reverence he demanded for the gods, the separation from foreigners to preserve morals, and a system where trade is conducted by the city rather than by individual citizens; they will provide for our arts without our luxury and satisfy our needs without fostering desires." [102]

No matter how much the crowd may exclaim, "It is Montesquieu, therefore it is magnificent! It is sublime!", I will have the courage of my convictions and say:

What! You have the nerve to find this beautiful? [103]

But it is horrifying! revolting! These excerpts, which I could multiply, show that in Montesquieu’s view, individuals, liberties, properties, and all of humanity itself are nothing more than raw materials for the legislator’s ingenuity.

ROUSSEAU. [104]

Although this writer, the supreme authority of democrats, bases the social structure on the general will, no one has more completely embraced the hypothesis of humanity’s complete passivity in the presence of the legislator.

"If it is true that a great prince is a rare man, how much rarer must a great legislator be? The first need only follow the model that the latter must create. [47] The legislator is the mechanic who invents the machine; the prince is merely the worker who assembles and operates it." [105]

And what are men in all this? The machine that is assembled and set in motion—or rather, the raw material from which the machine is made!

Thus, between the legislator and the Prince, and between the Prince and his subjects, there exist the same relationships as between an agronomist and a farmer, and between the farmer and the soil. How high above humanity must the writer be placed if he dares to govern even the legislators themselves, dictating their craft to them in these imperative terms:

"Do you want to give consistency to the state? Reduce the gap between the extremes as much as possible. Tolerate neither the very wealthy nor the destitute.

"If the land is barren or infertile, or the country too crowded for its inhabitants, turn to industry and the arts, exchanging their products for the goods you lack... If you have fertile land but lack people, devote all your efforts to agriculture, which increases population, and banish the arts, which would only further depopulate the country... If you have extensive, convenient coasts, cover the sea with ships; you will have a brilliant but short-lived existence. If the sea washes only against inaccessible cliffs on your shores, remain barbarous and live off fishing; [48] you will be more peaceful, perhaps better, and certainly happier. In short, besides the general maxims common to all, each people carries within itself a unique cause that dictates its own laws. Thus, in ancient times, the Hebrews and more recently the Arabs had religion as their principal concern; the Athenians, literature; Carthage and Tyre, commerce; Rhodes, maritime affairs; Sparta, war; and Rome, virtue. The author of The Spirit of Laws [106] has demonstrated how the legislator directs institutions toward each of these ends... But if the legislator, mistaken in his goal, chooses a principle that contradicts the natural order—one leading to servitude while the other aims at liberty, one toward wealth while the other fosters increased population, one toward peace while the other seeks conquest—then the laws will gradually weaken, the constitution will erode, and the state will be in perpetual turmoil until it is either destroyed or transformed, and the invincible force of nature regains its dominion." [107]

But if nature is invincible enough to reclaim its dominion, why does Rousseau not acknowledge that it did not need the legislator to assume that dominion in the first place? Why does he not admit that, following their own initiative, men would naturally turn to agriculture in fertile lands, to commerce [49] on vast and accessible coasts, without requiring a Lycurgus, a Solon, or a Rousseau to intervene—at the risk of being mistaken?

No matter what, one cannot ignore the immense responsibility that Rousseau places on the inventors, educators, leaders, legislators, and manipulators of societies. Consequently, he is extremely demanding of them.

"He who dares to undertake the foundation of a nation must feel capable of changing, so to speak, human nature—of transforming each individual, who by himself is a complete and solitary whole, into a part of a greater whole, from which he derives, in whole or in part, his life and being; of altering the constitution of man to strengthen it; of substituting a partial and moral existence for the physical and independent existence that we all received from nature. In short, he must take away from man his own forces to give him others that are foreign to him..." [108]

Poor human race—what would become of dignity under Rousseau’s followers?

RAYNAL. [109]

"Climate—that is, the sky and the soil—is the first rule of the legislator. His resources dictate his duties. He must first consult his local position. A people settled on a maritime coast will have laws related to navigation... [50] If the colony is inland, a legislator must anticipate both the type and the degree of its fertility..."

"It is above all in the distribution of property that the wisdom of legislation will shine. In general, and in all parts of the world, when founding a colony, land must be given to all men—that is, each must receive enough land to sustain a family..."

"If ONE were to populate a wild island with children, one would only need to let the seeds of truth develop naturally through reason... But when a pre-existing people is established in a new land, the skill lies in only letting it have those opinions and habits that cannot be cured or corrected. If one wishes to prevent their transmission, care must be taken to oversee the second generation through a common and public education of children. A prince, a legislator, should never found a colony without first sending wise men ahead for the education of the youth... In a nascent colony, all the conditions are in place for the legislator who seeks to purify the blood and morals of a people. If he possesses both genius and virtue, the lands and men at his disposal will inspire in him a plan of society that a mere writer can only outline vaguely, always subject to the instability of hypotheses, [51] which vary and become entangled with countless unforeseen and complex circumstances..." [110]

Does this not sound like an agriculture professor instructing his students? "Climate is the first rule for the farmer. His resources dictate his duties. He must first consult his local position. If he is on clay soil, he must proceed in a certain way. If he has sandy land, here is how he must manage it. All the means are available to the farmer who seeks to water and improve his soil. If he has skill, the land and fertilizers at his disposal will inspire him with a plan of cultivation, which a professor can only outline vaguely, subject to the instability of hypotheses, which vary and become entangled with countless unforeseen and complex circumstances."

But, oh, sublime writers, please remember now and then that this clay, this sand, this manure that you so arbitrarily manipulate—these are human beings! Your equals! Intelligent and free beings, like you, who have received from God, like you, the ability to see, to anticipate, to think, and to judge for themselves!

[52]

MABLY. [111]

(He assumes that laws have been corroded by the rust of time, the negligence of security, and he continues in this manner:)

"In such circumstances, one must be convinced that the mechanisms of government have become slack. Tighten them anew (this is addressed to the reader), and the problem will be solved... Focus less on punishing faults than on encouraging the virtues you need. By this method, you will restore the vigor of youth to your republic. It is because this principle was unknown to free peoples that they lost their liberty! But if the progress of decay is such that ordinary magistrates can no longer effectively address it, resort to an extraordinary magistracy, one of short duration but considerable power. At such times, the imagination of the citizens must be struck..." [112]

And everything continues in this tone for twenty volumes.

There was a time when, under the influence of such teachings—which form the foundation of classical education—everyone sought to place themselves outside and above humanity, to arrange, organize, and shape it at will.

CONDILLAC. [113]

“Rise, my lord, as a Lycurgus or a Solon. Before continuing to read this work, amuse yourself by giving laws to some [53] savage people in America or Africa: Establish these wandering men in fixed dwellings; teach them to raise livestock...; work to develop the social qualities that nature has placed within them... Order them to begin practicing the duties of humanity... Poison the pleasures promised by passions through punishments, and you will see these barbarians, with each article of your legislation, lose a vice and adopt a virtue.” [114]

"All people have had laws. But few of them have been happy. What is the cause? It is that legislators have almost always ignored the fact that the purpose of society is to unite families through a common interest."

"The impartiality of laws consists of two things: establishing equality in the wealth and dignity of citizens... As your laws establish greater equality, they will become dearer to every citizen... How could avarice, ambition, indulgence, laziness, idleness, envy, hatred, and jealousy agitate men who are equal in wealth and dignity, and for whom the laws leave no hope of breaking that equality?" (Then follows the idyll.)

"What has been told to you about the republic of Sparta should provide you with great insight into this question. No other state has ever had laws more in conformity with the order of nature or with equality." [115]

[54]

It is not surprising that the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries regarded the human race as inert matter, waiting to receive everything—form, shape, impetus, movement, and life—from a great Prince, a great legislator, or a great genius. These centuries were nourished by the study of antiquity, and antiquity everywhere—in Egypt, Persia, Greece, and Rome—presents the spectacle of a few men manipulating humanity at will, enslaved by force or deception. What does this prove? That, because man and society are perfectible, error, ignorance, despotism, slavery, and superstition must have accumulated all the more at the beginning of history. The fault of the writers I have cited is not that they observed this fact, but that they proposed it as a model for admiration and imitation by future generations. Their fault is that, with an inconceivable lack of critical thinking and through blind acceptance of a childish conventional thinking, they embraced what is utterly inadmissible—namely, the grandeur, dignity, morality, and well-being of these artificial societies of the ancient world. They failed to understand that time produces and spreads enlightenment, that as light increases, (the use of) force shifts to the side of (what is right) right, and society reclaims possession over itself.

[55]

And indeed, what is the political movement we are witnessing (today)? It is nothing other than the instinctive effort of all people (to move) toward liberty. And what is liberty—that word that has the power to stir all hearts and shake the world—if not the sum of all freedoms: freedom of conscience, of education, of association, of the press, of movement, of labor, of trade? In other words, the unrestricted exercise, for all, of all harmless faculties. [116] In yet other words, the destruction of all forms of despotisms, even legal despotism, and the reduction of the Law to its only rational function: regulating the individual right to legitimate (self) defense and repressing injustice.

This tendency of the human race, however, must be acknowledged as being greatly hindered, particularly in our own country, by the unfortunate disposition—born of classical education—that is common to all writers: the habit of placing themselves outside of humanity to arrange, organize, and shape it at will.

For while society struggles to realize liberty, the great men who position themselves at its head—steeped in the principles of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries—think only of bending it beneath the philanthropic despotism of their [56] social inventions, making it docilely bear, according to Rousseau’s expression, the yoke of public happiness as they have imagined it. [117]

This was clearly evident in 1789. Scarcely had the old legal regime been destroyed when efforts were made to subject the new society to other artificial arrangements, always starting from this unquestioned premise: the omnipotence of the Law.

SAINT-JUST. [118]

“The legislator commands the future. It is up to him to will the good. It is up to him to make men into what he wants them to be.” [119]

ROBESPIERRE. [120]

“The function of government is to direct the physical and moral forces of the nation toward the purpose of its institution.” [121]

BILLAUD-VARENNES. [122]

“The people must be recreated to be restored to liberty. Since it is necessary to destroy old prejudices, change ancient habits, perfect depraved affections, curb superfluous needs, and eradicate deep-seated vices, a strong action is required, a vehement impulse... Citizens, the inflexible austerity of Lycurgus became the unshakable foundation of the republic in Sparta; the weak and trusting nature of Solon plunged Athens back into slavery. This parallel contains the entire science of government.” [123]

[57]

LEPELLETIER. [124]

“Considering to what extent the human race is degraded, I have become convinced of the necessity of carrying out a complete regeneration and, if I may put it this way, of creating a new people.” [125]

As we can see, men are nothing more than cheap raw material. It is not for them to will the good—they are incapable of it, — it is for the legislator, according to Saint-Just. Men are only what he wants them to be.

According to Robespierre, who literally copies Rousseau, the legislator begins by assigning the purpose of the nation's founding. Then, governments have only to direct all physical and moral forces toward this purpose. The nation itself remains entirely passive in all of this, and Billaud-Varennes teaches us that it should have only the prejudices, habits, affections, and needs that the legislator authorizes. He even goes so far as to say that the inflexible austerity of one man is the foundation of the republic.

We have seen that in cases where the evil is so great that ordinary magistrates cannot remedy it, Mably recommended dictatorship to make virtue flourish.

"Have recourse," he says, "to an extraordinary magistracy, whose duration is short but whose power is considerable. The imagination of the citizens [58] must be struck."

This doctrine has not been lost. Let us listen to Robespierre:

"The principle of republican government is virtue, and its means, while it is being established, is terror. We want to substitute, in our country, morality for selfishness, honesty for honor, principles for customs, duties for decorum, the rule of reason for the tyranny of fashion, contempt for vice for contempt for misfortune, pride for insolence, greatness of soul for vanity, love of glory for love of money, good people for good company, merit for intrigue, genius for wit, truth for brilliance, the charm of happiness for the tedium of pleasure, the greatness of man for the littleness of the great, a magnanimous, powerful, happy people for a pleasant, frivolous, miserable one—in other words, all the virtues and miracles of the Republic instead of all the vices and absurdities of the monarchy." [126]

To what heights above the rest of humanity does Robespierre place himself here! And note the circumstances under which he speaks. He does not merely express a wish for a great renewal of the human heart; he does not even expect it to result from a regular government. No, he wants to bring it about himself—and through terror. The [59] speech from which this childish and laborious heap of contradictions is extracted was intended to set forth the moral principles that should guide a revolutionary government. Observe that when Robespierre calls for dictatorship, it is not merely to repel the foreigner and combat factions; it is, above all, to impose his own moral principles through terror, even before the constitution takes effect. His aim is nothing less than to eradicate from the country, by terror, selfishness, honor, customs, decorum, fashion, vanity, love of money, good company, intrigue, wit, pleasure, and poverty. Only after he, Robespierre, has accomplished these miracles—as he rightly calls them—will he allow the laws to resume their rule. Oh, miserable men who believe yourselves so great, who judge humanity to be so small, who want to reform everything—reform yourselves! That task alone should suffice for you.

However, in general, gentlemen reformers, legislators, and writers do not seek to exercise direct despotism over humanity. No, they are too moderate and too philanthropic for that. They seek only despotism, absolutism, the omnipotence of the Law. They merely aspire to make the Law.

[60]

To show how universal this strange frame of mind has been in France, just as I would have had to copy all of Mably, all of Raynal, all of Rousseau, all of Fénelon, and long excerpts from Bossuet and Montesquieu, I would also have to reproduce the entire record of the sessions of the Convention. [127] I will refrain from doing so and refer the reader to them instead.

It is easy to see that this idea must have appealed to Bonaparte.[128] He embraced it fervently and applied it energetically. Seeing himself as a chemist, he viewed Europe as mere material for experimentation. But soon this material revealed itself to be a powerful reagent. Three-quarters disillusioned, Bonaparte, at Saint Helena, seemed to acknowledge that there is some initiative in people, and he became less hostile to liberty. That did not, however, prevent him from leaving this lesson to his son in his will: "To govern is to spread morality, education, and well-being."

Is it necessary now to cite tedious passages to show where Morelly, Babeuf, Owen, Saint-Simon, and Fourier got their ideas?[129] I will content myself with submitting a few excerpts from Louis Blanc's [130] book On the Organization of Labor. [131]

[61]

"In our project, society receives its impetus from power." (Page 126.) [132]

And what does this impetus that power gives to society consist of? The imposition of Louis Blanc’s plan.

On the other hand, society means humanity.

Thus, ultimately, humanity receives its impetus from Louis Blanc.

He is free to do so, one might say. Indeed, humanity is free to follow the advice of whomever it wishes. But this is not how Mr. L. Blanc understands the matter. He insists that his project be turned into Law and consequently imposed by force through the power of the state.

"In our project, the state merely provides labor with a legal framework (excuse the modesty) by virtue of which industrial activity can and must proceed in complete freedom. The state does nothing more than place society on a slope (nothing more than that) which it then descends, once placed there, by the sheer force of circumstances and as a natural consequence of the established mechanism." [133]

But what is this slope?—The one indicated by Mr. L. Blanc.—Does it not lead to an abyss?—No, it leads to happiness.—Then why does society not place itself there of its own accord?—Because it does not know what it wants and [62] needs an impetus.—Who will provide this impetus?—The government. And who will give the government its impetus?—The inventor of the mechanism, Mr. L. Blanc.

We never escape this cycle: a passive humanity and a great man who moves it through the intervention of the Law.

Once on this slope, will society at least enjoy some freedom?—Certainly.—And what is freedom?

"Let us say it once and for all: freedom consists not only in the right granted but in the Power given to man to exercise and develop his faculties, under the rule of justice and the safeguard of the law."

"And this is not an empty distinction: its meaning is profound, and its consequences are immense. For as soon as one admits that man must have, in order to be truly free, the power to exercise and develop his faculties, it follows that society owes each of its members the appropriate education without which the human mind cannot unfold, and the tools of labor without which human activity cannot take flight. Now, through whose intervention will society provide each of its members with the necessary education and tools of labor, if not through the intervention of the state?" [134]

[63]

Thus, freedom is power.—And what does this POWER consist of? The possession of education and tools of labor.—Who will provide the education and tools of labor? society, which owes them to its members.—Through whose intervention will society provide tools of labor to those who lack them?—Through the intervention of the state.—From whom will the state take them?

It is up to the reader to answer this question and see where all of this leads.

One of the strangest phenomena of our time, which will probably astonish our descendants, is that the doctrine based on this triple hypothesis—the radical inertia of humanity, the omnipotence of the Law, the infallibility of the legislator—should be the sacred symbol of the party that proclaims itself exclusively democratic.

It is true that this party also calls itself social. [135]

In so far as it is democratic, it has boundless faith in humanity.

In so far as it is social, it places humanity above the mud.

When it comes to political rights—when it is a question of drawing the legislator from the bosom of the people—oh! then, according to this party, the people possess innate wisdom; they are endowed with admirable tact; their will is always just, the general will cannot err. Suffrage cannot be universal enough. No one owes society [64] any guarantees. The ability and will to choose wisely are always assumed. Can the people be mistaken? Are we not living in the age of enlightenment? What! Shall the people remain in tutelage forever? Have they not won their rights through enough effort and sacrifice? Have they not given sufficient proof of their intelligence and wisdom? Have they not reached maturity? Are they not capable of judging for themselves? Do they not know their own interests? Is there a man or a class that dares to claim the right to substitute itself for the people, to decide and act on their behalf? No, no, the people want to be free, and they will be. They want to manage their own affairs, and they will manage them.

But once the legislator has been released from making speeches and attending meetings, once he is elected, oh! then the language changes. The nation returns to passivity, to inertia, to nothingness, and the legislator takes possession of omnipotent powers. He takes charge of invention, direction, impetus, and organization. Humanity has only to submit; the hour of despotism has struck. And note that this is inevitable; for this people, just now so enlightened, so moral, so perfect, suddenly has no tendencies, or if it does, they all lead to degradation. And people want to leave them a little bit of liberty! But [65] do you not know that, according to Mr. Considérant, [136] liberty inevitably leads to monopoly? [137] Do you not know that liberty means competition? And that competition, according to Mr. L. Blanc, is for the people a system of extermination, and for the bourgeoisie a cause of ruin? [138] That is why the more free the people are, the more they are exterminated and ruined—witness Switzerland, Holland, England, and the United states. Do you not know, again according to Mr. L. Blanc, that competition leads to monopoly, and that for the same reason, cheap prices lead to exorbitant prices? That competition tends to dry up the sources of consumption and drives production into a frenzied activity? That competition forces production to increase while consumption decreases—hence it follows that free peoples produce without consuming; that competition is at once oppression and madness, and that it is absolutely necessary for Mr. L. Blanc to intervene? [139]