QUOTATIONS ABOUT LIBERTY AND POWER

(August 2024 edition)

[Created: 16 August, 2024]

[Updated: 22 August, 2024] |

Introduction

I compiled this collection of 600 quotations about liberty and power over a 15 year period 2004-2018 for the Liberty Fund's Online Library of Liberty of which I was the founding Director. It was designed to show the range of thinking about the 30 or so topics listed below, as well as to provide an entry point to the full text in order to allow the reader to explore the topic more deeply.

The OLL has broken the links back to the specific paragraph where the quotation is located. The link still takes you eventually to the whole text. From there you will have to navigate to the quote yourself. Sorry!

Guides to the Classical Liberal Tradition

This Guide is part of a collection of material relating to the history and theory of classical liberal/libertarian thought:

- a series of lectures and blog posts on The Classical Liberal Tradition: A 400 Year History of People, Ideas, and Movements for Reform

- The Great Books of Liberty: the large Guillaumin Collection in an "enhanced" HTML format and a citation tool for scholars (nearly 200 titles); and my personal favourites

- a collection of 600 Quotations about Liberty and Power from some of the key works in the Classical Liberal tradition. This collection of shorter pieces is organised into 30 topics. Each quotation has a brief commentary.

- The Classical Liberal Tradition: A Reader on Individual, Economic, and Political Liberty with a 100 or so chapter-length items to date. Each extract is accompanied by an introduction.

- articles from The Encyclopedia of Libertarianism (2008) organised thematically

Source

, Quotations about Liberty and Power. Edited by David M. Hart (The Pittwater Free Press, 2024).http://davidmhart.com/liberty/ClassicalLiberalism/Quotations/Quotes-2024.html

Various Authors, Quotations about Liberty and Power. Edited by David M. Hart (The Pittwater Free Press, 2024).

Table of Contents

- Class

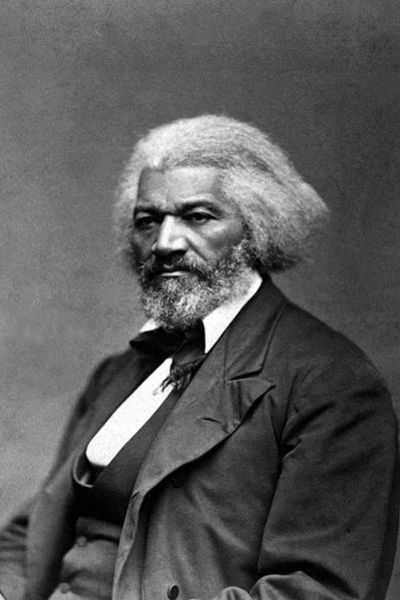

- Colonies, Slavery & Abolition

- Economics

- Education

- Food & Drink

- Free Trade

- Freedom of Speech

- Justice

- Law

- Liberty

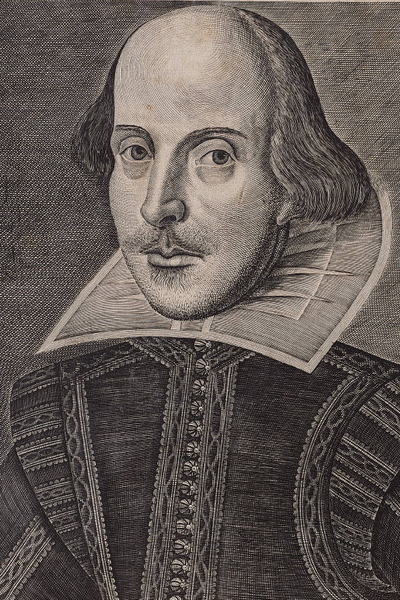

- Literature & Music

- Money & Banking

- Natural Rights

- Odds & Ends

- Origin of Government

- Parties & Elections

- Philosophy

- Politics & Liberty

- Presidents, Kings, Tyrants, & Despots

- Property Rights

- Religion & Toleration

- Revolution

- Rhetoric of Liberty

- Science

- Socialism & Interventionism

- Society

- Sport and Liberty

- Taxation

- The State

- War & Peace

- Women’s Rights

Class

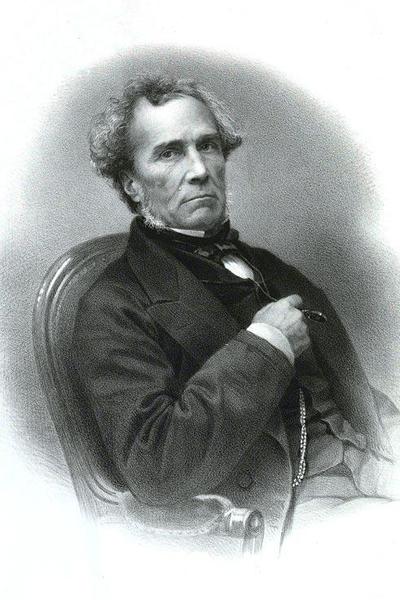

- John C. Calhoun notes that taxation divides the community into two great antagonistic classes, those who pay the taxes and those who benefit from them (1850)

- John Stuart Mill discusses the origins of the state whereby the “productive class” seeks protection from one “member of the predatory class” in order to gain some security of property (1848)

- Richard Cobden outlines his strategy of encouraging more people to acquire land and thus the right to vote in order to defeat the “landed oligarchy” who ruled England and imposed the “iniquity” of the Corn Laws (1845)

- James Madison on the “sagacious and monied few” who are able to “harvest” the benefits of government regulations (1787)

- Bentham on how “the ins” and “the outs” lie to the people in order to get into power (1843)

- James Mill on the “sinister interests” of those who wield political power (1825)

- Molinari on the elites who benefited from the State of War (1899)

- James Mill on the ruling Few and the subject Many (1835)

- William Cobbett on the dangers posed by the “Paper Aristocracy” (1804)

- Herbert Spencer observes that class structures emerge in societies as a result of war and violence (1882)

- Jeremy Bentham argued that the ruling elite benefits from corruption, waste, and war (1827)

- Adam Smith on why people obey and defer to their rulers (1759)

- Algernon Sidney on how the absolute state treats its people like cattle (1698)

- Adam Smith on the dangers of faction and privilege seeking (1759)

- Yves Guyot warns that a new ruling class of managers and officials will emerge in the supposedly “classless” socialist society of the future (1908)

- James Bryce on the autocratic oligarchy which controls the party machine in the American democratic system (1921)

- Jeremy Bentham on how the interests of the many (the people) are always sacrificed to the interests of the few (the sinister interests) (1823)

- Adam Smith thinks many candidates for high political office act as if they are above the law (1759)

- William Graham Sumner on the political corruption which is “jobbery” (1884)

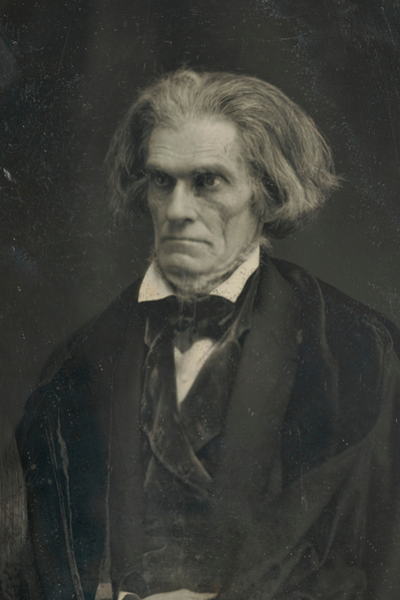

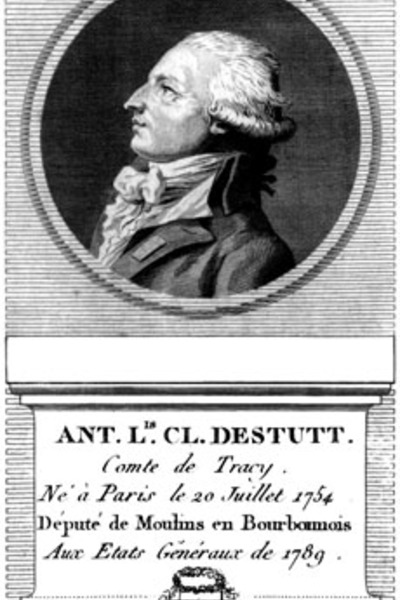

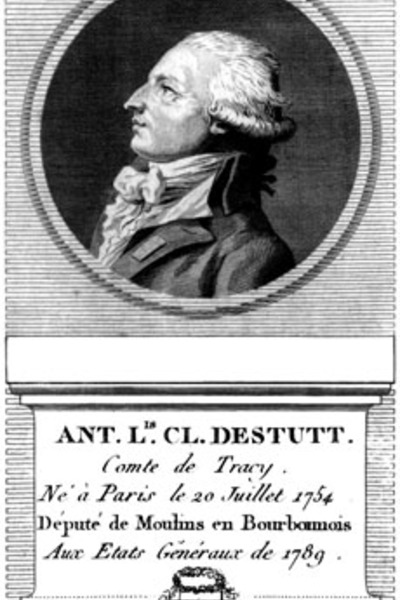

John C. Calhoun notes that taxation divides the community into two great antagonistic classes, those who pay the taxes and those who benefit from them (1850) ↩

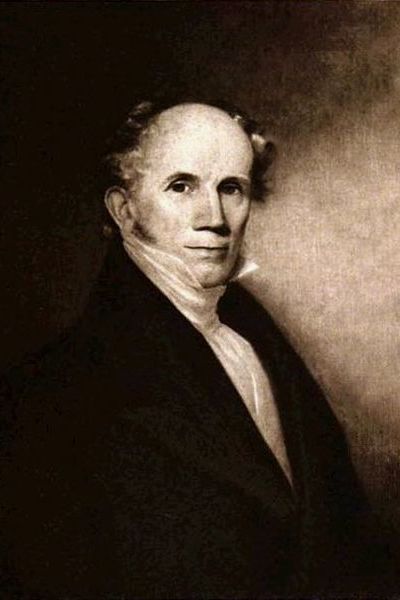

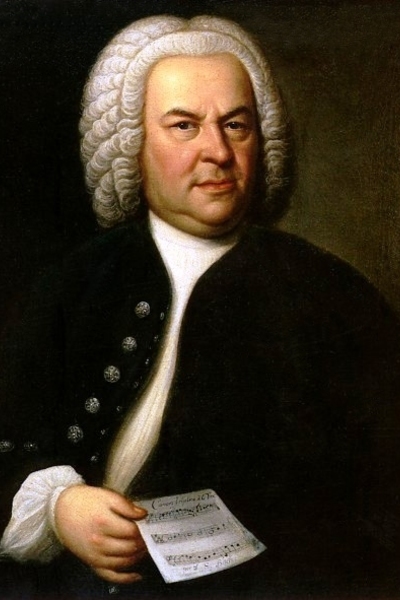

John C. Calhoun (1782 – 1850)

In an extended critique of The Federalist, the pre-Civil War Southern political philosopher John C. Calhoun argued that any system of taxation inevitably divided citizens into two antagonistic groups - the net tax payers and the net tax consumers:

Few, comparatively, as they are, the agents and employees of the government constitute that portion of the community who are the exclusive recipients of the proceeds of the taxes. Whatever amount is taken from the community, in the form of taxes, if not lost, goes to them in the shape of expenditures or disbursements. The two—disbursement and taxation—constitute the fiscal action of the government. They are correlatives. What the one takes from the community, under the name of taxes, is transferred to the portion of the community who are the recipients, under that of disbursements. But, as the recipients constitute only a portion of the community, it follows, taking the two parts of the fiscal process together, that its action must be unequal between the payers of the taxes and the recipients of their proceeds. Nor can it be otherwise, unless what is collected from each individual in the shape of taxes, shall be returned to him, in that of disbursements; which would make the process nugatory and absurd. Taxation may, indeed, be made equal, regarded separately from disbursement. Even this is no easy task; but the two united cannot possibly be made equal.

Such being the case, it must necessarily follow, that some one portion of the community must pay in taxes more than it receives back in disbursements; while another receives in disbursements more than it pays in taxes. It is, then, manifest, taking the whole process together, that taxes must be, in effect, bounties to that portion of the community which receives more in disbursements than it pays in taxes; while, to the other which pays in taxes more than it receives in disbursements, they are taxes in reality—burthens, instead of bounties. This consequence is unavoidable. It results from the nature of the process, be the taxes ever so equally laid, and the disbursements ever so fairly made, in reference to the public service…

The necessary result, then, of the unequal fiscal action of the government is, to divide the community into two great classes; one consisting of those who, in reality, pay the taxes, and, of course, bear exclusively the burthen of supporting the government; and the other, of those who are the recipients of their proceeds, through disbursements, and who are, in fact, supported by the government; or, in fewer words, to divide it into tax-payers and tax-consumers.

But the effect of this is to place them in antagonistic relations, in reference to the fiscal action of the government, and the entire course of policy therewith connected. For, the greater the taxes and disbursements, the greater the gain of the one and the loss of the other—and vice versa; and consequently, the more the policy of the government is calculated to increase taxes and disbursements, the more it will be favored by the one and opposed by the other.

The effect, then, of every increase is, to enrich and strengthen the one, and impoverish and weaken the other. This, indeed, may be carried to such an extent, that one class or portion of the community may be elevated to wealth and power, and the other depressed to abject poverty and dependence, simply by the fiscal action of the government; and this too, through disbursements only—even under a system of equal taxes imposed for revenue only. If such may be the effect of taxes and disbursements, when confined to their legitimate objects—that of raising revenue for the public service—some conception may be formed, how one portion of the community may be crushed, and another elevated on its ruins, by systematically perverting the power of taxation and disbursement, for the purpose of aggrandizing and building up one portion of the community at the expense of the other. That it will be so used, unless prevented, is, from the constitution of man, just as certain as that it can be so used; and that, if not prevented, it must give rise to two parties, and to violent conflicts and struggles between them, to obtain the control of the government, is, for the same reason, not less certain.

About this Quotation

In 1850 John C. Calhoun penned one of the most important pieces of political theory in 19th century America, his Disquisition on Government. In it he proposed a new way of viewing societies as torn between two competing and antagonistic groups, “classes” if you will. On the one hand there are those who pay the taxes upon which all government activities ultimately depend (the “tax-payers”), and on the other hand there are those whose livelihoods depend upon this tax revenue (the “tax-consumers”). At the same time in France, Frédéric Bastiat had developed very similar ideas. In Germany, Marx was becoming increasingly confused on this same issue.

Source

John C. Calhoun, Union and Liberty: The Political Philosophy of John C. Calhoun, ed. Ross M. Lence (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 1992). [Source at OLL website]

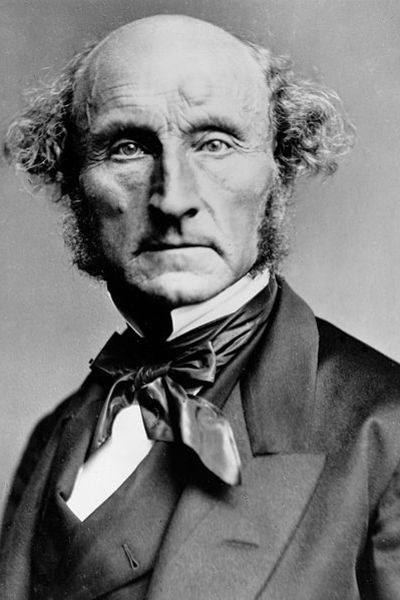

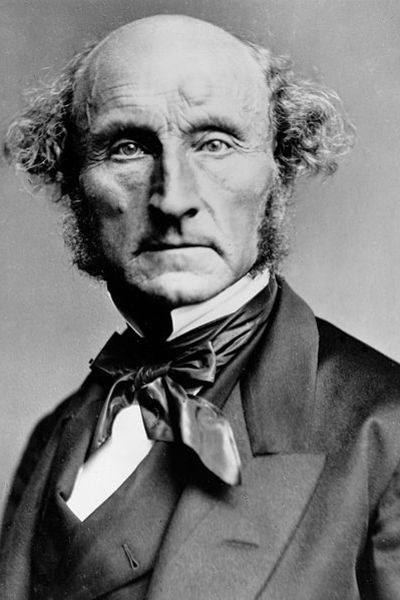

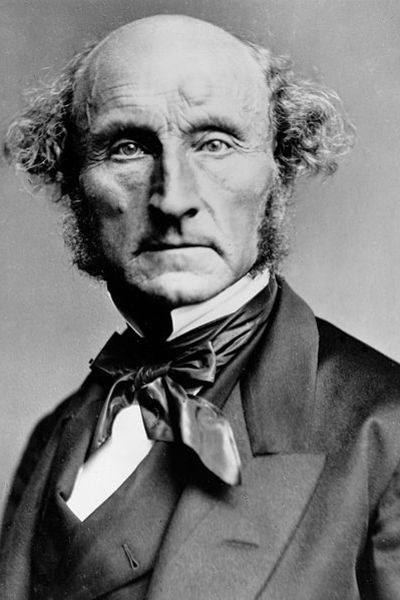

John Stuart Mill discusses the origins of the state whereby the “productive class” seeks protection from one “member of the predatory class” in order to gain some security of property (1848) ↩

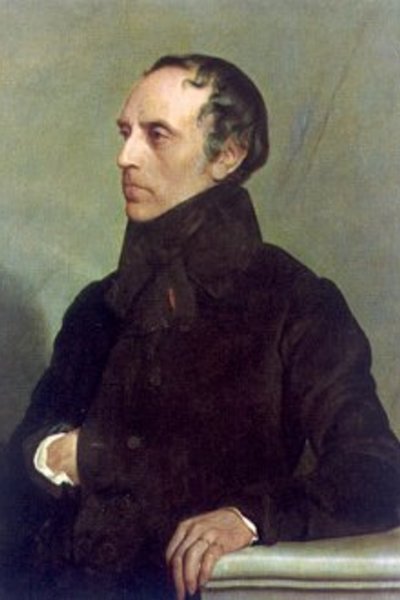

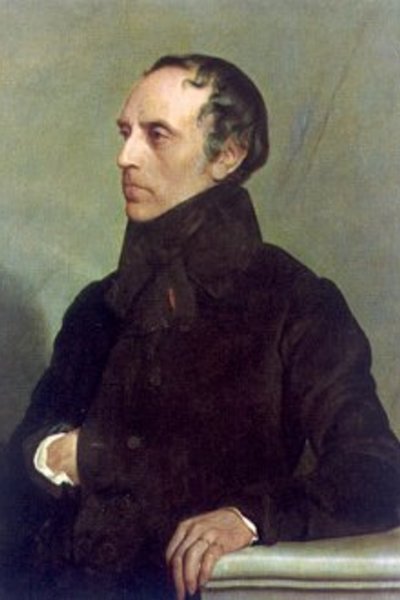

John Stuart Mill (1806 – 1873)

In a chapter on the function of government in The Principles of Political Economy (1848) John Stuart Mill observed how the state (or the predatory class) forces the productive classes into a condition of uncertainty, insecurity, and dependence:

§ 1. [Effects of imperfect security of person and property] Before we discuss the line of demarcation between the things with which government should, and those with which they should not, directly interfere, it is necessary to consider the economical effects, whether of a bad or of a good complexion, arising from the manner in which they acquit themselves of the duties which devolve on them in all societies, and which no one denies to be incumbent on them.

The first of these is the protection of person and property. There is no need to expatiate on the influence exercised over the economical interests of society by the degree of completeness with which this duty of government is performed. Insecurity of person and property, is as much as to say, uncertainty of the connexion between all human exertions or sacrifice, and the attainment of the ends for the sake of which they are undergone. It means, uncertainty whether they who sow shall reap, whether they who produce shall consume, and they who spare to-day shall enjoy to-morrow. It means, not only that labour and frugality are not the road to acquisition, but that violence is. When person and property are to a certain degree insecure, all the possessions of the weak are at the mercy of the strong. No one can keep what he has produced, unless he is more capable of defending it, than others who give no part of their time and exertions to useful industry are of taking it from him. The productive classes, therefore, when the insecurity surpasses a certain point, being unequal to their own protection against the predatory population, are obliged to place themselves individually in a state of dependence on some member of the predatory class, that it may be his interest to shield them from all depredation except his own. In this manner, in the Middle Ages, allodial property generally became feudal, and numbers of the poorer freemen voluntarily made themselves and their posterity serfs of some military lord.

Nevertheless, in attaching to this great requisite, security of person and property, the importance which is justly due to it, we must not forget that even for economical purposes there are other things quite as indispensable, the presence of which will often make up for a very considerable degree of imperfection in the protective arrangements of government. As was observed in a previous chapter, the free cities of Italy, Flanders, and the Hanseatic league, were habitually in a state of such internal turbulence, varied by such destructive external wars, that person and property enjoyed very imperfect protection; yet during several centuries they increased rapidly in wealth and prosperity, brought many of the industrial arts to a high degree of advancement, carried on distant and dangerous voyages of exploration and commerce with extraordinary success, became an overmatch in power for the greatest feudal lords, and could defend themselves even against the sovereigns of Europe: because in the midst of turmoil and violence, the citizens of those towns enjoyed a certain rude freedom, under conditions of union and co-operation, which, taken together, made them a brave, energetic, and high-spirited people, and fostered a great amount of public spirit and patriotism. The prosperity of these and other free states in a lawless age, shows that a certain degree of insecurity, in some combinations of circumstances, has good as well as bad effects, by making energy and practical ability the conditions of safety. Insecurity paralyzes, only when it is such in nature and in degree, that no energy of which mankind in general are capable, affords any tolerable means of self-protection. And this is a main reason why oppression by the government, whose power is generally irresistible by any efforts that can be made by individuals, has so much more baneful an effect on the springs of national prosperity, than almost any degree of lawlessness and turbulence under free institutions. Nations have acquired some wealth, and made some progress in improvement, in states of social union so imperfect as to border on anarchy: but no countries in which the people were exposed without limit to arbitrary exactions from the officers of government, ever yet continued to have industry or wealth. A few generations of such a government never fail to extinguish both. Some of the fairest, and once the most prosperous, regions of the earth, have, under the Roman and afterwards under the Turkish dominion, been reduced to a desert, solely by that cause. I say solely, because they would have recovered with the utmost rapidity, as countries always do, from the devastations of war, or any other temporary calamities. Difficulties and hardships are often but an incentive to exertion: what is fatal to it, is the belief that it will not be suffered to produce its fruits.

About this Quotation

In an analysis of the history of the formation of the state which is quite similar to that of Franz Oppenheimer (1864-1943) John Stuart Mill begins by discussing the deleterious effects on production caused by the “incomplete security of person and property”. One should recall his discussion of the “vultures” and their “harpies” which drive the productive classes to seek some security from the strongest “vulture” against the myriad other “vultures” who prey on them. In exchange for continuing to pay the strongest “vulture” his protection money, the productive class is spared from having to pay off all the others. Thus begins the state in the medieval period according to Mill. In another interesting passage Mill discusses the impact that established governments have on national prosperity: “oppression by the government, whose power is generally irresistible by any efforts that can be made by individuals, has so much more baneful an effect on the springs of national prosperity, than almost any degree of lawlessness and turbulence under free institutions.”

Source

John Stuart Mill, The Collected Works of John Stuart Mill, Volume III - The Principles of Political Economy with Some of Their Applications to Social Philosophy (Books III-V and Appendices), ed. John M. Robson, Introduction by V.W. Bladen (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1965). [Source at OLL website]

Richard Cobden outlines his strategy of encouraging more people to acquire land and thus the right to vote in order to defeat the “landed oligarchy” who ruled England and imposed the “iniquity” of the Corn Laws (1845) ↩

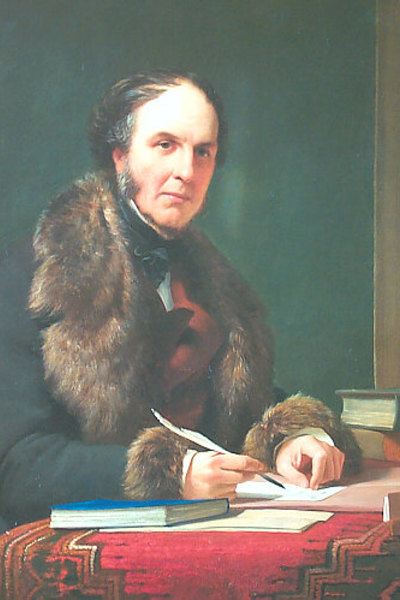

Richard Cobden (1804 – 1865)

In the Covent Garden Theatre in London on 15 January 1845 Richard Cobden (1804-1865) addressed a large crowd on the continuing struggle to abolish the Corn Laws (tariffs) which was eventually achieved when Sir Robert Peel announced their repeal on 27 January, 1846. In this New Year speech Cobden urged the better off members of the middle class to purchase land in the counties so that they could acquire the right to vote and thus defeat the “landed oligarchy”. In passing, he suggested that women should also have the right to vote:

I remember quite well, five years ago, when we first came up to Parliament to petition the Legislature, a certain noble earl, who had distinguished himself previously by advocating a repeal of the Corn-laws, called upon us at Brown’s Hotel. The committee of the deputation had a private interview with him, during which he asked us what we came to petition for? We replied, for the total and immediate repeal of the Corn-laws. His answer was, ‘My belief is, that the present Parliament would not pass even a 12s. fixed duty; I am quite sure they would not pass a 10s.; but as for the total repeal of the Corn-law, you may as well try to overturn the monarchy as to accomplish that object.’ I do not think any one would go so far as to tell us that now; I do not suppose that, if you were to go to Tattersall’s, ‘Lord George’ would offer you very long odds that this law will last five years longer. We have done something to shake the old edifice, but it will require a great deal of battering yet to bring it down about the ears of its supporters. It will not be done in the House; it must be done out of it. Neither will it be effected with the present constituency; you must enlarge it first. I have done something towards that end since I last saw you. I have assisted in bringing four or five thousand new ‘good men and true’ into the electoral list—four or five thousand that we know of in Lancashire, Yorkshire, and Cheshire; and I believe there are five or ten times as many more throughout the country, who have taken the hint we gave them of getting possession of the electoral franchise for the counties. Some people tell you that it is very dangerous and unconstitutional to invite people to enfranchise themselves by buying a freehold qualification. I say, without being revolutionary or boasting of being more democratic than others, that the sooner the power in this country is transferred from the landed oligarchy, which has so misused it, and is placed absolutely—mind, I say ‘absolutely'’—in the hands of the intelligent middle and industrious classes, the better for the condition and destinies of this country.

I hope that every man who has the ability to possess himself of the franchise for a county, will regard it as his solemn and sacred duty to do so before the 31st of this month. Recollect what it is we ask you to do: to take into your own hands the power of doing justice to twenty-seven millions of people! When Watt presented himself before George III., the old monarch asked him what article he made; and the immortal inventor of the steam-engine replied, ‘Your Majesty, I make that which kings are fond of—power.’ Now, we seek to create a higher power in England, by inducing our fellow-countrymen to place themselves upon the electoral list in the counties. We must have not merely the boroughs belonging to the people; but give the counties to the towns, which are their right; and not the towns to the counties, as they have been heretofore. There is not a father of a family, who has it at all in his power, but ought to place at the disposal of his son the franchise for a county; no, not one. It should be the parent’s first gift to his son, upon his attaining the age of twenty. There are many ladies, I am happy to say, present; now, it is a very anomalous and singular fact, that they cannot vote themselves, and yet that they have a power of conferring votes upon other people. I wish they had the franchise, for they would often make a much better use of it than their husbands. The day before yesterday, when I was in Manchester (for we are brought up now to interchange visits with each other by the miracle of steam in eight hours and a half), a lady presented herself to make inquiries how she could convey a freehold qualification to her son, previous to the 31st of this month; and she received due instructions for the purpose. Now, ladies who feel strongly on this question—who have the spirit to resent the injustice that is practised on their fellow-beings—cannot do better than make a donation of a county vote to their sons, nephews, grandsons, brothers, or any one upon whom they can beneficially confer that privilege. The time is short; between this and the 31st of the month, we must induce as many people to buy new qualifications as will secure the representation of Lancashire, the West Riding of Yorkshire, and Middlesex. I will guarantee the West Riding of Yorkshire and Lancashire; will you do the same by Middlesex?

I am quite sure you will do what you can, each in his own private circle. This is a work which requires no gift of oratory, or powerful public appeals; it is a labour in which men can be useful privately and without ostentation. If there be any in this land who have seen others enduring probably more labour than their share, and feel anxious to contribute what they can to this good cause, let them take up this movement of qualifying for the counties; and in their several private walks do their best to aid us in carrying out this object. We have begun a new year, and it will not finish our work; but whether we win this year, the next, or the year after, in the mean time we are not without our consolations. When I think of this most odious, wicked, and oppressive system, and reflect that this nation—so renowned for its energy, independence, and spirit—is submitting to have its bread taxed, its industry crippled, its people—the poorest in the land—deprived of the first necessaries of life, I blush that such a country should submit to so vile a degradation. It is, however, consolation to me, and I hope it will be to all of you, that we do not submit to it without doing our best to put an end to the iniquity.

About this Quotation

At the beginning of 1845 Richard Cobden could sense that victory in the struggle to repeal the Corn Laws was imminent. As he realised, a great deal had been achieved politically in the 5 years the Anti-Corn Law League had been active and that “the old edifice” of the English establishment had been shaken by the movement he led. In the final push he urged the better off members of the middle class to purchase land in the counties in order to qualify to vote in the next election which might see the power of the “landed oligarchy” challenged and the Corn Laws finally abolished. In passing, he makes a remarkable admission about women and the right to vote, stating that he wished they had the franchise “for they would often make a much better use of it than their husbands.”

Source

Richard Cobden, Speeches on Questions of Public Policy by Richard Cobden, M.P., ed. by John Bright and J.E. Thorold Rogers with a Preface and Appreciation by J.E. Thorold Rogers and an Appreciation by Goldwin Smith (London: T.Fisher Unwin, 1908). 2 volumes in 1. Vol. 1 Free Trade and Finance. [Source at OLL website]

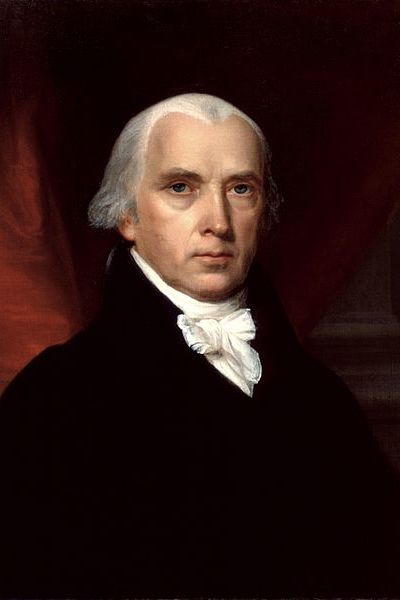

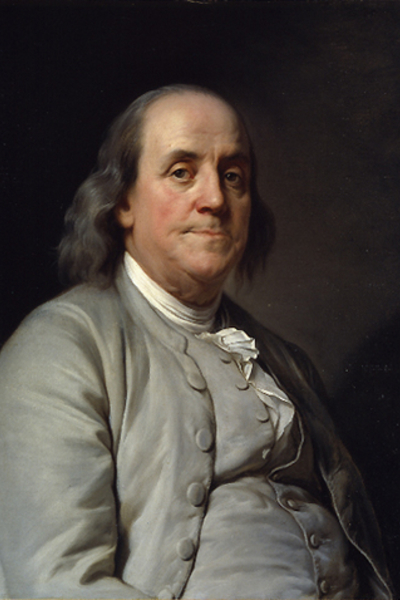

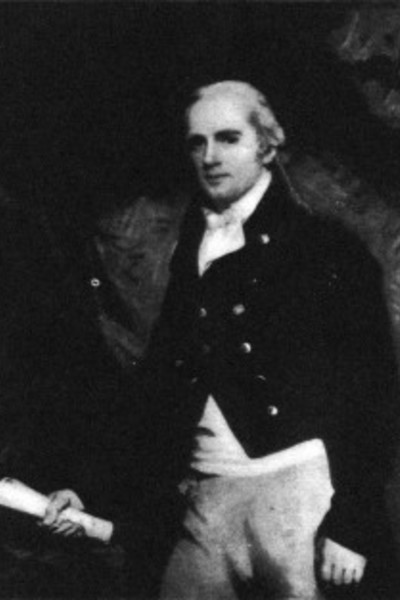

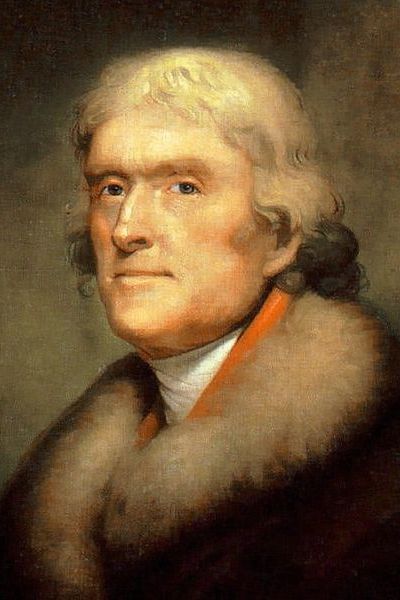

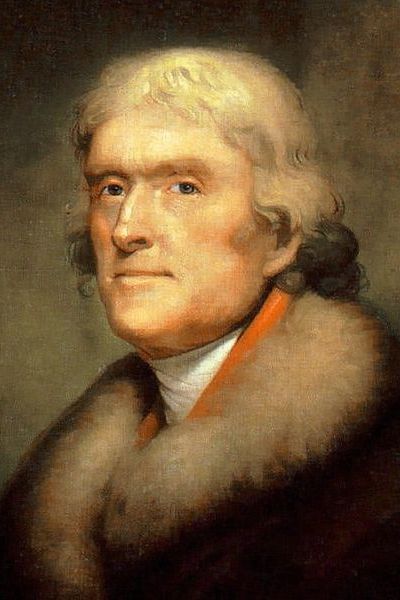

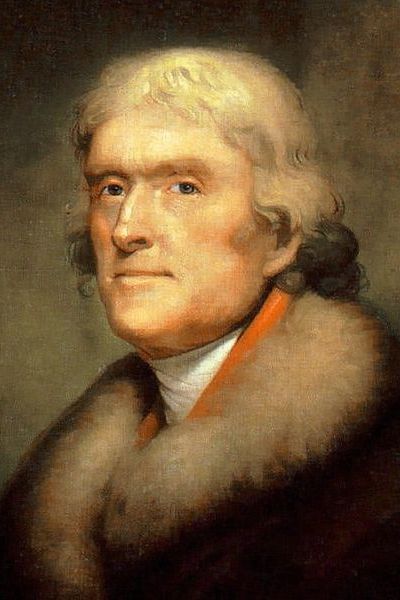

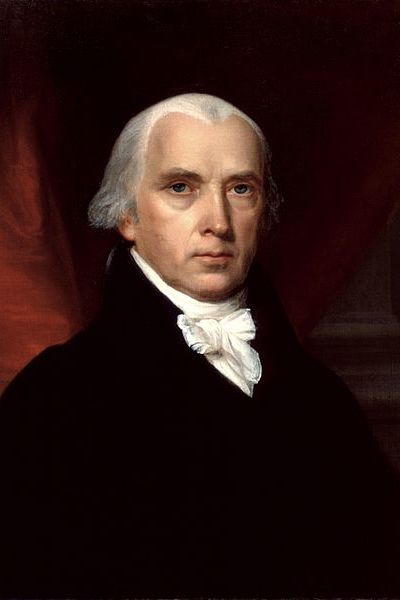

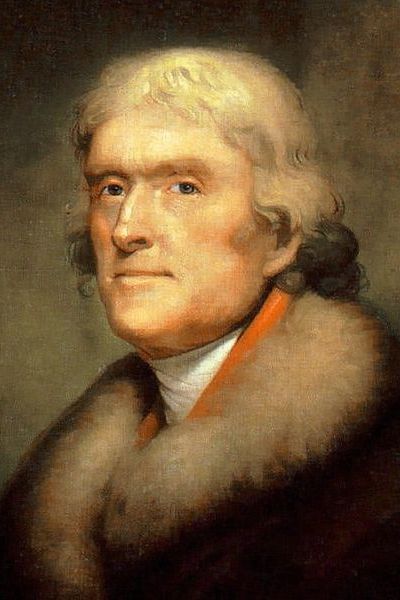

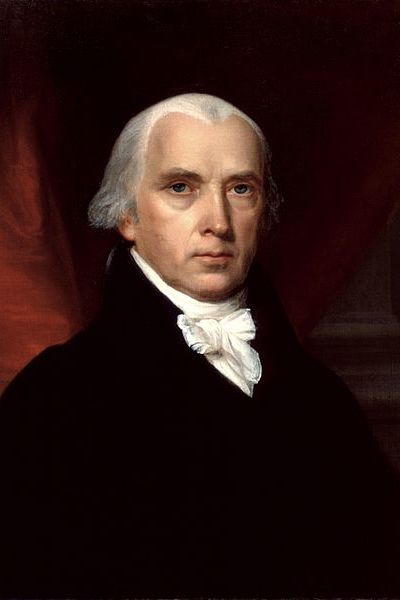

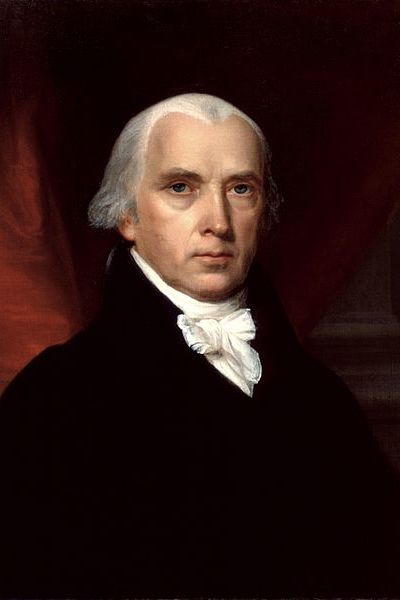

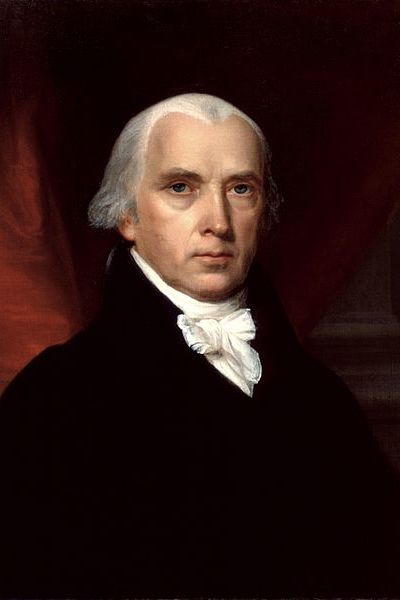

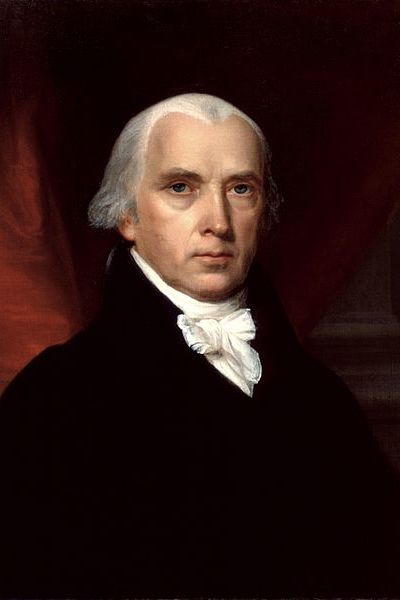

James Madison on the “sagacious and monied few” who are able to “harvest” the benefits of government regulations (1787) ↩

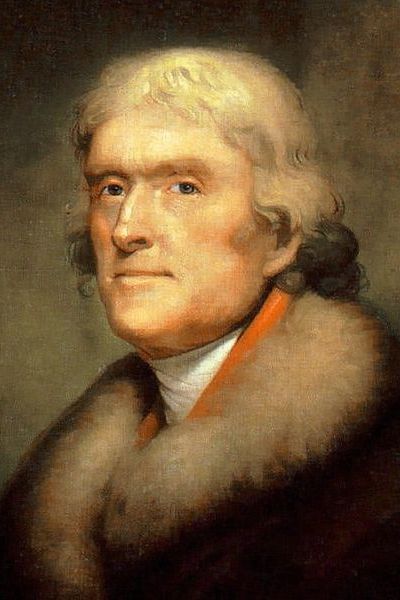

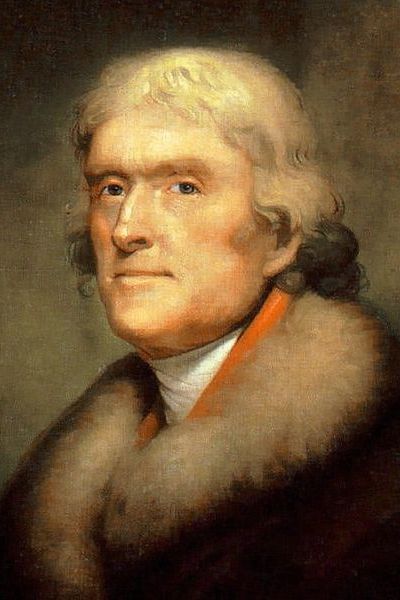

James Madison (1751 – 1836)

In Federalist Paper no. 62 James Madison (1751-1836) observes that every piece of government legislation opens up opportunities for profit by a “sagacious and monied few” to take advantage of their less well-informed fellow citizens:

To trace the mischievous effects of a mutable government, would fill a volume. I will hint a few only, each of which will be perceived to be a source of innumerable others…

The internal effects of a mutable policy are still more calamitous. It poisons the blessings of liberty itself. It will be of little avail to the people, that the laws are made by men of their own choice, if the laws be so voluminous that they cannot be read, or so incoherent that they cannot be understood: if they be repealed or revised before they are promulg[at]ed, or undergo such incessant changes, that no man who knows what the law is to-day, can guess what it will be to-morrow. Law is defined to be a rule of action; but how can that be a rule, which is little known and less fixed.

Another effect of public instability, is the unreasonable advantage it gives to the sagacious, the enterprising, and the monied few, over the industrious and uninformed mass of the people. Every new regulation concerning commerce or revenue, or in any manner affecting the value of the different species of property, presents a new harvest to those who watch the change, and can trace its consequences; a harvest, reared not by themselves, but by the toils and cares of the great body of their fellow citizens. This is a state of things in which it may be said, with some truth, that laws are made for the few, not for the many.

About this Quotation

It should not be surprising to see many so-called “public choice” insights in the writings of the Founding Fathers of the American constitution. They were accutely aware of the self-interested activities of legislators and their allies in commerce and industry. Here we have an excellent example of this kind of analysis more commonly associated with the modern Public Choice school of economics pioneered by Tullock and Buchanan. Madison uses the analogy of “harvesting” to describe the behavior of well-informed and politically well-connected individuals who are able to extract “rents” from the opportunities opened up by government regulations and legislation. These “sagacious and monied few” are able then to pocket their political “harvest” at the expence of the “ industrious and uninformed mass of the people”.

Source

George W. Carey, The Federalist (The Gideon Edition), Edited with an Introduction, Reader’s Guide, Constitutional Cross-reference, Index, and Glossary by George W. Carey and James McClellan (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 2001). [Source at OLL website]

Bentham on how “the ins” and “the outs” lie to the people in order to get into power (1843) ↩

Jeremy Bentham (1748 – 1832)

Jeremy Bentham (1748-1832) created a Handbook of Political Fallacies in which he painstakingly categorized the different types of “fallacies” politicians used to deceive the public. He did this in order to show how those in government deceived the people in order to win office or get favours from those in office:

By the name of fallacy, it is common to designate any argument employed, or topic suggested, for the purpose, or with a probability, of producing the effect of deception,—of causing some erroneous opinion to be entertained by any person to whose mind such argument may have been presented….

First, fallacies of authority (including laudatory personalities;) the subject-matter of which is authority in various shapes—and the immediate object, to repress, on the ground of the weight of such authority, all exercise of the reasoning faculty.

Secondly, fallacies of danger (including vituperative personalities;) the subject-matter of which is the suggestion of danger in various shapes—and the object, to repress altogether, on the ground of such danger, the discussion proposed to be entered on.

Thirdly, fallacies of delay; the subject-matter of which is an assigning of reasons for delay in various shapes—and the object, to postpone such discussion, with a view of eluding it altogether.

Fourthly, fallacies of confusion; the subject-matter of which consists chiefly of vague and indefinite generalities—while the object is to produce, when discussion can no longer be avoided, such confusion in the minds of the hearers as to incapacitate them for forming a correct judgment on the question proposed for deliberation….

Parliament (is) a sort of gaming-house; members on the two sides of each house the players; the property of the people—such portion of it as on any pretence may be found capable of being extracted from them—the stakes played for. Insincerity in all its shapes, disingenuousness, lying, hypocrisy, fallacy, the instruments employed by the players on both sides for obtaining advantages in the game: on each occasion—in respect of the side on which he ranks himself—what course will be most for the advantage of the universal interest, a question never looked at, never taken into account: on which side is the prospect of personal advantage in its several shapes—this the only question really taken into consideration: according to the answer given to this question in his own mind, a man takes the one or the other of the two sides—the side of those in office, if there be room or near prospect of room for him: the side of those by whom office is but in expectancy, if the future contingent presents a more encouraging prospect than the immediately present….

About this Quotation

The first version of Bentham’s Handbook of Political Fallacies appeared in French early in the 19th century and it had a important impact on the thinking of Frédéric Bastiat who produced his own examination of “economic fallacies” in the mid and late 1840s (mainly to do with tariffs and government subsidies). Bentham thought that the British Parliament was so corrupt that he could fill an entire book with carefully articulated definitions and categories of lying, deception, intimidation, and obfuscation used by politicians and bureaucrats to hoodwink the public into accepting taxes, regulations, and payments to favoured groups. In this marvelous passage he compares the Parliament to a casino, where the politicians were the gamblers, and the property of the citizens was the stakes being played for. “Disingenuousness, lying, hypocrisy, (and) fallacy” were the tactics used by the players in order to win each round of the game. Those who were “the ins” (in office) had a temporary advantage in the game; those who were “the outs” (those aspiring to be in office next) could only hope their turn would soon come. In Bentham’s cynical though realistic view, “the universal interest (was) a question never looked at, never taken into account” by the players.

Source

Jeremy Bentham, The Works of Jeremy Bentham, published under the Superintendence of his Executor, John Bowring (Edinburgh: William Tait, 1838-1843). 11 vols. Vol. 2. [Source at OLL website]

James Mill on the “sinister interests” of those who wield political power (1825) ↩

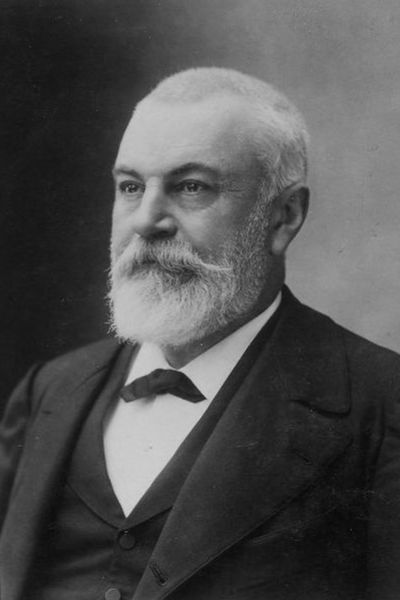

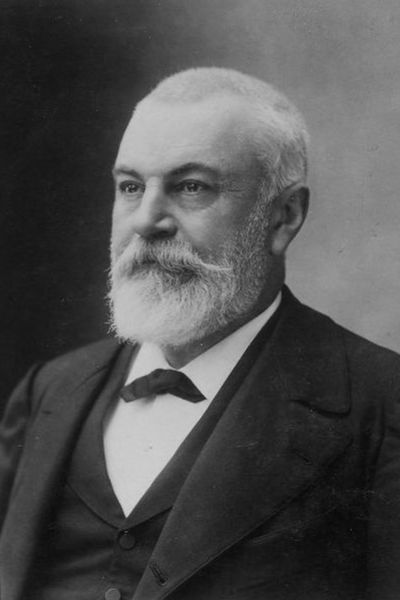

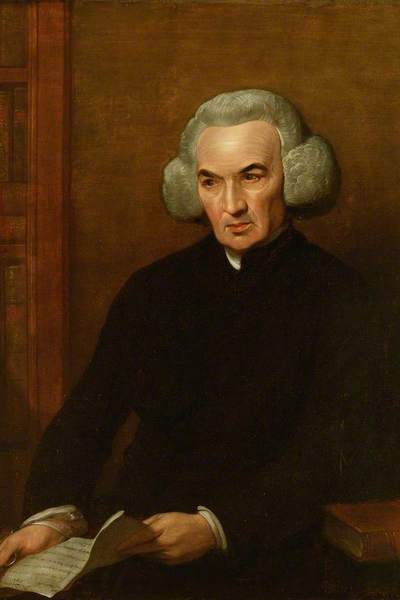

James Mill (1773 – 1836)

The Utilitarian and Philosophic Radical James Mill (1773-1836) wrote a series of articles for the Supplement to the 1825 edition of the Encyclopedia Britannica. In the article on “Government” he warns of the dangers of the selfish and “sinister interests” all those who wield power, unless checked by an informed people:

We have seen already, that if one man has power over others placed in his hands, he will make use of it for an evil purpose; for the purpose of rendering those other men the abject instruments of his will. If we, then, suppose, that one man has the power of choosing the Representatives of the people, it follows, that he will choose men, who will use their power as Representatives for the promotion of this his sinister interest.

We have likewise seen, that when a few men have power given them over others, they will make use of it exactly for the same ends, and to the same extent, as the one man. It equally follows, that, if a small number of men have the choice of the Representatives, such Representatives will be chosen as will promote the interests of that small number, by reducing, if possible, the rest of the community to be the abject and helpless slaves of their will.

In all these cases, it is obvious and indisputable, that all the benefits of the Representative system are lost. The Representative system is, in that case, only an operose and clumsy machinery for doing that which might as well be done without it; reducing the community to subjection, under the One, or the Few.

When we say the Few, it is seen that, in this case, it is of no importance whether we mean a few hundreds, or a few thousands, or even many thousands. The operation of the sinister interest is the same; and the fate is the same, of all that part of the community over whom the power is exercised. A numerous Aristocracy has never been found to be less oppressive than an Aristocracy confined to a few.

The general conclusion, therefore, which is evidently established is this; that the benefits of the Representative system are lost, in all cases in which the interests of the choosing body are not the same with those of the community.

About this Quotation

The Philosophic Radicals and Utilitarians who were influenced by the writings of Jeremy Bentham, such as James Mill (the father of John Stuart), were very skeptical of the intentions of those who wielded political power. Bentham had warned in his Handbook of Political Fallacies that politically powerful people would use deception and lies to promote their own interests. This idea is very similar to Frédéric Bastiat’s idea of “sophisms” which were used by powerful economic interests to promote their subsidies and tariff protection at the expense of ordinary consumers. James Mill took that suspicion a step further in the several articles he wrote for the 1825 Supplement to the Encyclopedia Britannica, especially the article on “Government”. Here he develops the idea of a “sinister interest” which was held by all those with unchecked political power. Unless they were well chosen and closely supervised by an informed electorate, the politically powerful would inevitably use their position to promote their own selfish, private interests at the expense of the ordinary taxpayer.

Source

James Mill, Supplement to the Encyclopedia Britannica (London: J. Innes, 1825). [Source at OLL website]

Molinari on the elites who benefited from the State of War (1899) ↩

Gustave de Molinari (1819 – 1912)

The French economist Gustave de Molinari (1819-1912) concluded in 1899 that wars would continue to be fought, in spite of their growing cost in terms of destruction wrought, lives lost, and high taxes, as long as powerful groups within society benefited personally from such a situation. To his mind, this meant the powerful political, bureaucratic, and military elites which controlled European societies at the end of the 19th century:

The fact that war has become useless is not, however, sufficient to secure its cessation. It is useless because it ceases to minister to the general and permanent benefit of the species, but it will not cease until it also becomes unprofitable, till it is so far from procuring benefit to those who practise it, that to go to war is synonymous with embracing a loss.

A consideration of modern wars from this aspect produces two opposite replies. Every State includes a governing class and a governed class. The former is interested in the immediate multiplication of employments open to its members, whether these be harmful or useful to the State, and also desires to remunerate these officials at the best possible rate. But the majority of the nation, the governed class, pays for the officials, and its only desire is to support the least necessary number. A State of War, implying an unlimited power of disposition over the lives and goods of the majority, allows the governing class to increase State employments at will—that is, to increase its own sphere of employment. A considerable portion of this sphere is found in the destructive apparatus of the civilised State—an organism which grows with every advance in the power of the rivals. In time of peace the army supports a hierarchy of professional soldiers, whose career is highly esteemed, and is assured if not particularly remunerative. In time of war the soldier obtains an additional remuneration, more glory, and an increased hope of professional advancement, and these advantages more than compensate the risks which he is compelled to undergo. In this way a State of War continues to be profitable both to the governing class as a whole, and to those officials who administer and officer the army. Moreover, every industrial improvement increases this profit, for the enormous late increase in the wealth which nations derive from this source necessitates enlarged armaments, but also permits the imposition of heavier imposts.

But while the State of War has become more and more profitable to the class interested in the public services, it has become more burdensome and more injurious to the infinite majority which only consumes those services. In time of tranquillity it supports the burden of the armed peace, and the abuse, by the governing class, of the unlimited power of taxation necessitated by the State of War, intended to supply the means of national defence, but perverted to the profit of government and its dependents. The case of the governed is even worse in time of war. Whatever the issue of the struggle, and receiving none of the compensation afforded in previous ages, when a war ensured its safety from attack by the barbarian, it supports an immediate increase in the taxes, and a future and semi-permanent increase in the interest on loans, those inseparable accidents of modern war, and also the indirect losses which accompany the disorganisation of trade—injuries whose effects become more far-reaching with every extension in the time and area covered by modern commercial relations.

The human balance sheet under a State of War thus favours the governor at the expense of the governed, nor can the most cursory glance at the budgets of civilisation—especially if directed to their provisions for the service of National Debts—fail to perceive to which quarter, and in how large a degree, that balance inclines. This, in itself, affords no guarantee that the State of War is nearing an end, for the governing class, under present conditions, disposes of a far more formidable power than that immense, but, as we may call it, amorphous strength, which is dormant in the masses. They, as no one may deny, have often risen against governments extorting too high a price for their services, or threatening to overwhelm them with intolerable burdens, but the success of such movements seldom results in more than a change of masters, and the new governing class has usually been larger and of inferior quality. The result of these revolutions has been what it always must be—augmented burdens and a recrudescence of the State of War.

Nevertheless, this State of War must come to its inevitable conclusion. It continuously and, one may say, automatically drains the resources of the governed, and, since it is these resources which support the governing class, that class must eventually find itself face to face with the end. The same influences that maintain the State of War, though long since effete, will then close it, and humanity will enter a new and better period of existence, the period of Peace and Liberty. We have already attempted to sketch the political and economic organisation which will follow, built upon understanding of the motive forces and natural laws which govern human action. The difference between this organisation and the socialistic programme is singularly essential—it will observe, while theirs denies, these laws.

About this Quotation

As early of the late 1890s the French economist Gustave de Molinari (1819-1912) could see that the resurgence of tariffs, the arms race (especially the naval arms race), and the scramble for colonies in the third world was leading inevitably to a major conflict between the major European powers. He asked himself how this was possible given the enormous physical costs of modern warfare and the economic burdens it imposed on ordinary taxpayers. His sad conclusion was that bellicose policies benefited certain members of the governing class who were well organised, whereas the governed class who bore the burdens were “amorphous” and not well organised in the opposition. He identified a number of powerful groups in European societies who benefited from what he called “the State of War”: the political elites who dominated the legislatures and controlled expenditure, the senior bureaucrats who administered government expenditure, the military elites who got to spend taxpayers money on new ships and artillery and who benefitted from promotions, the business elites whose factories produced the war materiel, and the officials who administered colonial policy in the occupied territories. Molinari concluded, perhaps somewhat wistfully, that this situation had to come to an end when the taxpayers and the producers realised the enormous expences they were forced to pay. Molinari died in 1912 two years before the outbreak of World War One showed how destructive modern wars would be.

Source

Gustave de Molinari, The Society of Tomorrow: A Forecast of its Political and Economic Organization, ed. Hodgson Pratt and Frederic Passy, trans. P.H. Lee Warner (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1904). [Source at OLL website]

James Mill on the ruling Few and the subject Many (1835) ↩

James Mill (1773 – 1836)

James Mill (1773-1836) identifies two groups in British society, namely “the ruling Few” who enjoy legal and economic privileges, and “the subject Many” who pay the taxes and submit to the regulations:

To understand this unhappy position of a portion of our fellow-citizens, we must call to mind the division which philosophers have made of men placed in society. They are divided into two classes, Ceux qui pillent,—et Ceux qui sont pillés [those who pillage, and those who are pillaged]; and we must consider with some care what this division, the correctness of which has not been disputed, implies.

The first class, Ceux qui pillent [those who pillage], are the small number. They are the ruling Few. The second class, Ceux qui sont pillés [those who are pillaged], are the great number. They are the subject Many.

It is obvious that, to enable the Few to carry on their appropriate work, a complicated system of devices was required, otherwise they would not succeed; the Many, who are the stronger party, would not submit to the operation. The system they have contrived is a curious compound of force and fraud:—force in sufficient quantity to put down partial risings of the people, and, by the punishments inflicted, to strike terror into the rest; fraud, to make them believe that the results of the process were all for their good.

First, the Many were frightened with the danger of invasion and ravage, by foreign enemies; that so they might believe a large military force in the hands of the Few to be necessary for their protection; while it was ready to be employed in their coercion, and to silence their complaints of anything by which they might find themselves aggrieved.

Next, the use of all the circumstances calculated to dazzle the eyes, and work upon the imaginations of men, was artfully adopted by the class of whom we speak. They dwelt in great and splendid houses; they covered themselves with robes of a peculiar kind; they made themselves be called by names, all importing respect, which other men were not permitted to use; they were constantly followed and surrounded by numbers of people, whose interest they made it to treat them with a submission and a reverence approaching adoration; even their followers, and the horses on which they rode, were adorned with trappings which were gazed upon with admiration by all those who considered them as things placed beyond their reach.

And this was not all, nor nearly so. There were not only dangers from human foes; there were invisible powers from whom good or evil might proceed to an inconceivable amount. If the opinion could be generated, that there were men who had an influence over the occurrence of this good or evil, so as to bring on the good, or avert the evil, it is obvious that an advantage was gained of prodigious importance; an instrument was found, the power of which over the wills and actions of men was irresistible.

Ceux qui pillent have in all ages understood well the importance of this instrument to the successful prosecution of their trade. Hence the Union of Church and State; and the huge applauses with which so useful a contrivance has been attended. Hence the complicated tissue of priestly formalities, artfully contrived to impose upon the senses and imaginations of men—the peculiar garb—the peculiar names—the peculiar gait and countenance of the performers—the enormous temples devoted to their ceremonies—the enormous revenues subservient to the temporal power and pleasures of the men who pretended to sand between their fellow-creatures and the evils to which they were perpetually exposed, by the will of Him whom they called their perfectly good and wise and benevolent God.

If, besides the power which the priestly class were thus enabled to exercise over the minds of adult men, they were also permitted to engross the business of education—that is, to create such habits of mind in the rising generation, as were subservient to their purposes, and to prevent the formation of all such habits as were opposed to them—the chains they had placed on the human mind would appear to have been complete: the prostration of the understanding and the will—the perpetual object of their wishes and endeavours down to the present hour—to have been secured for ever.

The alliance of the men, who wielded the priestly power, was, in these circumstances, a matter of great importance to those who wielded the political power; and the confederacy of the two was of signal service to the general end of both—the maintenance of that old and valuable relation—the relation between Those qui pillent, and Those qui sont pillés.

About this Quotation

In this essay Mill provides one of his regular surveys of “the state of the nation” in which he sums up political developments in Britain. It was written a few years after the success of the “Reform Party” in agitating for electoral reform which greatly increased the size of the electorate with the Reform Act of 1832. Now that most of the middle class could vote it was hoped that the Members of Parliament who represented them would dramatically reform British politics, especially in the areas of aristocrat control of Parliament, the legal system, the established church, and free trade. Concerning the latter, the Anti-Corn Law League was established in 1838 under the leadership of Richard Cobden and it was able to achieve its goal of eliminating the protectionist corn laws in 1846. Mill acknowledges “the strength of the spirit of reform” which was sweeping Britain but is also aware of the continuing strength of its opponents among conservatives and the fact that the reform party was split into “moderate” and “radical” reformers. Concerning the former, he develops a French liberal inspired theory of class which explains politics as a struggle between two contending groups, “ceux qui pillent” (those who pillage, also known as “the ruling Few”) and “ceux qui sont pillés” those who are pillaged, also known as “the subject Many”). Concerning the latter, he urges the reform party to continue pushing for reforms in all areas by adopting the strategy of the radical reformers. Mill believed that liberty in Britain would not be achieved until the privileged elites had been deprived of their power and the people were allowed to rule in their place. He had in mind removing the privileges of “the priests of all three classes; those who serve at the altar of state, those who serve at the altar of law, and those who serve at the altar of religion.”

Source

James Mill, The Political Writings of James Mill: Essays and Reviews on Politics and Society, 1815-1836, ed. David M. Hart . [Source at OLL website]

William Cobbett on the dangers posed by the “Paper Aristocracy” (1804) ↩

William Cobbett (1763 – 1835)

The English radical William Cobbett (1763-1835) objected to the funding of the war against Napoleon by issuing debt and suspending gold payments. He called the financial elite who benefited from the huge increase in government debt as the “Paper Aristocracy”:

Amongst the great and numerous dangers to which this country, and particularly the monarchy, is exposed, in consequence of the enormous public debt, the influence, the powerful and widely-extended influence, of the monied interest is, perhaps, the most to be dreaded, because it necessarily aims at measures which directly tend to the subversion of the present order of things. In speaking of this monied interest, I do not mean to apply the phrase, as it was applied formerly, that is to say, to distinguish the possessors of personal property, more especially property in the funds, from persons possessing lands; the division of the proprietors into a monied interest, and a landed interest, is not applicable to the present times, all the people who have any thing, having now become, in a greater or less degree, stock-holders. From this latter circumstance it is artfully insinuated, that they are all deeply and equally interested in supporting the system; and, such is the blindness of avarice, or rather of self-interest, that men in general really act as if they preferred a hundred pounds’ worth of stock to an estate in land of fifty times the value. But, it is not of this mass of stock-holders; it is not of that description of persons who leave their children’s fortunes to accumulate in those funds, where, even according to the ratio of depreciation already experienced, a pound of to-day will not be worth much above a shilling twenty years hence; it is not of these simpletons of whom I speak, when I talk of the monied interest of the present day; I mean an interest hostile alike to the land-holder and to the stock-holder, to the colonist, to the real merchant, and to the manufacturer, to the clergy, to the nobility and to the throne; I mean the numerous and powerful body of loan-jobbers, directors, brokers, contractors and farmers general, which has been engendered by the excessive amount of the public debt, and the almost boundless extension of the issues of paper-money,——It was a body very much like this, which may with great propriety, I think, be denominated the Paper Aristocracy, that produced the revolution in France. Burke evidently had our monied interest, as well as that of France, in his view; but, when, in another passage of his celebrated work, he was showing the extreme injustice of seizing upon the property of the Church to satisfy the demands of the paper aristocracy of France, he little imagined that an act of similar injustice would so soon be thought of, and even proposed, in England, where clergyman and pauper are become terms almost synonymous. He had been an attentive observer of the rise and progress of the change that was taking place in France: and he thought it necessary to warn his own country, in time, against the influence of a description of persons, who, aided by a financiering minister, who gave into all their views, had begun the destruction of the French monarchy.——Our paper-aristocracy, who arose with the schemes of Mr. Pitt, have proceeded with very bold strides; theirs was the proposition for commuting the tithes; theirs the law for the redemption of the land-tax; theirs the numerous laws and regulations which have been made of late years in favour of jobbing and speculation, till at last they obtained a law compelling men to take their paper in payment of just debts, while they themselves were exempted, by the same law, from paying any part of the enormous debts which they had contracted, though they had given promissory notes for the amount!

About this Quotation

In this critique of the massive increase in British government debt to fund the war against Napoleon, Cobbett makes two interesting points. One is the observation that a similar thing had happened in France and this was a bad omen for what Prime Minister Pitt was doing in England, what he called the “Pitt System”. The French state had massive debts which it could not pay off from the war against England fought in North America during the 1750s and 1760s. In an attempt to do so, it became indebted to its own Paper Aristocracy of state financiers and tax farmers with dire consequences. To raise more money the King called a meeting of the Estates General, which triggered the Revolution in 1788-89. The second point Cobbett makes, is that he makes a clear distinction between the non-productive, parasitical financiers of state debt (the Paper Aristocracy) and other productive members of the economy such as “the land-holder and the stock-holder, the colonist, the real merchant, and the manufacturer.”

Source

William Cobbett, Selections from Cobbett’s Political Works: being a complete abridgement of the 100 volumes which comprise the writings of “Porcupine” and the “Weekly political register.” With notes, historical and explanatory. By John M. Cobbett and James P. Cobbett. (London, Ann Cobbett, 1835). Vol. 1. [Source at OLL website]

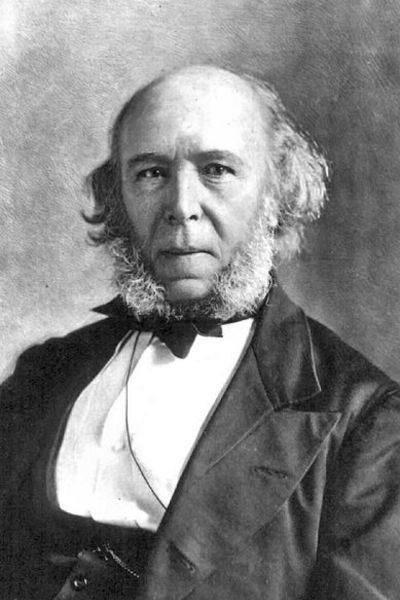

Herbert Spencer observes that class structures emerge in societies as a result of war and violence (1882) ↩

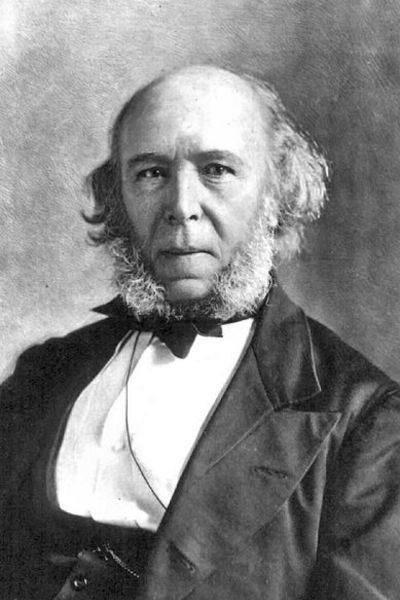

Herbert Spencer (1820 – 1903)

In his discussion of the origin of the state and the elites which control it, Herbert Spencer (1820-1903) notes that war made it possible for class and exploitation to emerge, whether between men and women or between master and slave:

So is it when we pass from the greater or less political differentiation which accompanies difference of sex, to that which is independent of sex—to that which arises among men. Where the life is permanently peaceful, definite class-divisions do not exist. …

§ 456. As, at first, the domestic relation between the sexes passes into a political relation, such that men and women become, in militant groups, the ruling class and the subject class; so does the relation between master and slave, originally a domestic one, pass into a political one as fast as, by habitual war, the making of slaves becomes general. It is with the formation of a slave-class, that there begins that political differentiation between the regulating structures and the sustaining structures, which continues throughout all higher forms of social evolution. …

… Be this as it may, however, we find that very generally among tribes to which habitual militancy has given some slight degree of the appropriate structure, the enslavement of prisoners becomes an established habit. That women and children taken in war, and such men as have not been slain, naturally fall into unqualified servitude, is manifest. They belong absolutely to their captors, who might have killed them, and who retain the right afterwards to kill them if they please. They become property, of which any use whatever may be made.

The acquirement of slaves, which is at first an incident of war, becomes presently an object of war. …

The class-division thus initiated by war, afterwards maintains and strengthens itself in sundry ways. Very soon there begins the custom of purchase. … Then the slave-class, thus early enlarged by purchase, comes afterwards to be otherwise enlarged. There is voluntary acceptance of slavery for the sake of protection; there is enslavement for debt; there is enslavement for crime.

Leaving details, we need here note only that this political differentiation which war begins, is effected, not by the bodily incorporation of other societies, or whole classes belonging to other societies, but by the incorporation of single members of other societies, and by like individual accretions. Composed of units who are detached from their original social relations and from one another, and absolutely attached to their owners, the slave-class is, at first, but indistinctly separated as a social stratum. It acquires separateness only as fast as there arise some restrictions on the powers of the owners. Ceasing to stand in the position of domestic cattle, slaves begin to form a division of the body politic when their personal claims begin to be distinguished as limiting the claims of their masters.

About this Quotation

One of the things that makes it hard to read Spencer’s magnum opus The Principles of Sociology is the large number of historical examples Spencer provides to support each of his claims. In this quotation I have removed the examples in order to focus on Spencer’s conclusions. The key passages refer to the very different types of societies which emerge under peace (“industrial types of society”) or under war and violence (“militant types of society”). In his view, in a peaceful society dominated by voluntary exchange and other relationships, “where the life is permanently peaceful, definite class-divisions do not exist.” The very existence of class, where one group uses force to dominate and exploit another, does not appear until war becomes the dominant feature of the society. The need to fight and to supply the fighters with the resources they need, creates class. It turns relations between men and women “political” whereby they become “the ruling class and the subject class” respectively. Much the same happens to domestic slavery as “habitual war” turns slavery into a “mass commodity” (my term not his).

Source

Herbert Spencer, The Principles of Sociology, in Three Volumes (New York: D. Appleton and Company, 1898). Vol. 2. [Source at OLL website]

Jeremy Bentham argued that the ruling elite benefits from corruption, waste, and war (1827) ↩

Jeremy Bentham (1748 – 1832)

According to Jeremy Bentham (1748-1832) the “ruling one” (the monarch) along with its companion group, “the sub-ruling few” (the establishment), have an interest in creating or maintaining corruption, waste, and war:

Under a government which has for its object the greatest happiness of the greatest number, official frugality is an object uniformly and anxiously pursued: peace, were it only as an instrument of such frugality, cultivated with proportionable sincerity and anxiety: any want of effect given to the laws, by which contributions are required for the maintenance of government, universally felt and regarded as a mischief: all endeavours employed in the evasion of them regarded as generally mischievous, and as such punished, and with full reason, by general contempt.

Under a government which has for its main object the sacrifice of the greatest happiness of the greatest number, to the sinister interest of the ruling one and the sub-ruling few, corruption and delusion to the greatest extent possible, are necessary to that object: waste, in so far as conducive to the increase of the corruption and delusion fund, a subordinate or co-ordinate object: war, were it only as a means and pretence for such waste, another object never out of view: that object, together with those others, invariably pursued, in so far as the contributions capable of being extracted from contributors, involuntary or voluntary, in the shape of taxes, or in the shape of loans, i. e. annuities paid by government by means of further taxes, can be obtained:—under such a government, by every penny paid into the Treasury, the means of diminishing the happiness of the greatest number receive increase;—by every penny which is prevented from taking that pernicious course, the diminution of that general happiness is so far prevented.

As, under the one government, every man, in proportion to the regard he feels for the greatest happiness of the greatest number, will give his strength to the revenue laws, and set his strength against all endeavours employed for the evasion of them,—so, under the other sort of government, in proportion to the regard he feels for that same object, will he set his strength against the laws, and in support of all endeavours employed for the evasion of them. Thus in particular, and so in general. In so far as the laws have been made every man’s enemy, every man in defence, not only of his own happiness, but of the happiness of the greatest number, will, in desire and endeavour, be an enemy to the laws.

About this Quotation

A key insight Bentham had into the operation of politics was the idea of “the sinister interest.” According to Bentham, every individual had both universal interests (a concern for the interests of mankind in general) and sinister interests (or personal and selfish interests which worked against the universal interests of mankind). It was the task of rational bureaucrats who ran the state to ensure that sinister interests did not over-ride the universal interests of mankind. In this passage from his Principles of Judicial Procedure (1827) he argues that when the state is instead run by a few individuals, or what he calls “the ruling one and the sub-ruling few,” they have a vested interest in promoting the corruption from which they derive their livelihoods. This “corruption” is made possible by government waste, war and war contracts, the increase of taxes, and government loans. Although normally a stickler for obeying the law at all times, when corruption is rife in a state he believes upright men and women should evade the revenue laws in order to deprive the corrupt sinister interests of their source of revenue and income, and thus promote “the happiness of the greatest number”.

Source

Jeremy Bentham, The Works of Jeremy Bentham, published under the Superintendence of his Executor, John Bowring (Edinburgh: William Tait, 1838-1843). 11 vols. Vol. 2. [Source at OLL website]

Adam Smith on why people obey and defer to their rulers (1759) ↩

Adam Smith (1723 – 1790)

In the Theory of Moral Sentiments (1759) Adam Smith (1723-1790) reflects on why so many people defer to authority, especially to monarchs and the nobility:

Upon this disposition of mankind, to go along with all the passions of the rich and the powerful, is founded the distinction of ranks, and the order of society. Our obsequiousness to our superiors more frequently arises from our admiration for the advantages of their situation, than from any private expectations of benefit from their goodwill. Their benefits can extend but to a few; but their fortunes interest almost every body. We are eager to assist them in completing a system of happiness that approaches so near to perfection; and we desire to serve them for their own sake, without any recompense but the vanity or the honour of obliging them. Neither is our deference to the inclinations founded chiefly, or altogether, upon a regard to the utility of such submission, and to the order of society, which is best supported by it. Even when the order of society seems to require that we should oppose them, we can hardly bring ourselves to do it. That kings are servants of the people, to be obeyed, resisted, deposed, or punished, as the public conveniency may require, is the doctrine of reason and philosophy; but it is not the doctrine of nature. Nature would teach us to submit to them for their own sake, to tremble and bow down before their exalted station, to regard their smile as a reward sufficient to compensate any services, and to dread their displeasure, though no other evil were to follow from it, as the severest of all mortifications. To treat them in any respect as men, to reason and dispute with them upon ordinary occasions, requires such resolution, that there are few men whose magnanimity can support them in it, unless they are likewise assisted by similarity and acquaintance. The strongest motives, the most furious passions, fear, hatred, and resentment, are scarce sufficient to balance this natural disposition to respect them: and their conduct must, either justly or unjustly, have excited the highest degree of those passions, before the bulk of the people can be brought to oppose them with violence, or to desire to see them either punished or deposed. Even when the people have been brought this length, they are apt to relent every moment, and easily relapse into their habitual state of deference to those whom they have been accustomed to look upon as their natural superiors. They cannot stand the mortification of their monarch. Compassion soon takes the place of resentment, they forget all past provocations, their old principles of loyalty revive, and they run to re-establish the ruined authority of their old masters, with the same violence with which they had opposed it. The death of Charles I. brought about the restoration of the royal family. Compassion for James II., when he was seized by the populace in making his escape on ship-board, had almost prevented the Revolution, and made it go on more heavily than before.

About this Quotation

In a chapter on “the Origin of Ambition, and of the Distinction of Ranks” Adam Smith reflects on why people are so deferential to people with power and authority, or as he put it why are we so “obsequiousness to our superiors?” He provides a number of answers to that question but one that is very interesting is the notion that we do so not out of some expectation of any personal benefit or of fear of punishment if we don’t but out of a feeling of “admiration for the advantages of their situation”. In an important passage, Smith notes that a rational person would “resist, depose, or punish, (a king) as the public conveniency may require” but most do not. We have so internalised our love and respect for our rulers that we “submit to them for their own sake” and they forget “the easy price at which they may acquire the public admiration”. When the people’s resentment at their mistreatment by their rulers reaches the point of violence, as it did with King Charles I in 1649, the people are quickly remorseful at what they have done, “Compassion soon takes the place of resentment, they forget all past provocations, their old principles of loyalty revive, and they run to re-establish the ruined authority of their old masters, with the same violence with which they had opposed it.”

Source

Adam Smith, Essays On, I. Moral Sentiments: II. Astronomical Inquiries; III. Formation of Languages; IV. History of Ancient Physics; V. Ancient Logic and Metaphysics; VI. The Imitative Arts; VII. Music, Dancing, Poetry; VIII. The External Senses; IX. English and Italian Verses, ed. Joseph Black and James Hutton (London: Alex. Murray & Son, 1869). [Source at OLL website]

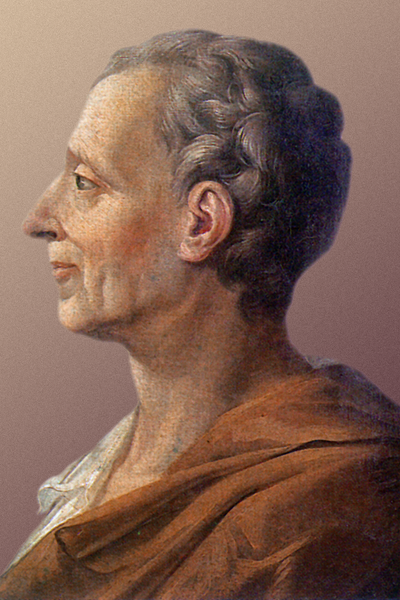

Algernon Sidney on how the absolute state treats its people like cattle (1698) ↩

Algernon Sidney (1622 – 1683)

The English radical republican Algernon Sidney (1623-1683) argues that absolute rule over others means that the people are treated like so many oxen who are only fed so “that they may be strong for labour, or fit for slaughter”:

His reasons for this are as good as his (Filmer’s) doctrine: It is, saith he, the multitude of people and abundance of riches, that are the glory and strength of every prince: the bodies of his subjects do him service in war, and their goods supply his wants. Therefore if not out of affection to his people, yet out of natural love unto himself, every tyrant desires to preserve the lives and goods of his subjects. I should have thought that princes, tho tyrants, being God’s vicegerents, and fathers of their people, would have sought their good, tho no advantage had thereby redounded to themselves, but it seems no such thing is to be expected from them. They consider nations, as grazers do their herds and flocks, according to the profit that can be made of them: and if this be so, a people has no more security under a prince, than a herd or flock under their master. Tho he desire to be a good husband, yet they must be delivered up to the slaughter when he finds a good market, or a better way of improving his land; but they are often foolish, riotous, prodigal, and wantonly destroy their stock, tho to their own prejudice. We thought that all princes and magistrates had been set up, that under them we might live quietly and peaceably, in all godliness and honesty: but our author teaches us, that they only seek what they can make of our bodies and goods, and that they do not live and reign for us, but for themselves. If this be true, they look upon us not as children, but as beasts, nor do us any good for our own sakes, or because it is their duty, but only that we may be useful to them, as oxen are put into plentiful pastures that they may be strong for labour, or fit for slaughter. This is the divine model of government that he offers to the world. The just magistrate is the minister of God for our good: but this absolute monarch has no other care of us, than as our riches and multitude may increase his own glory and strength.

About this Quotation

Born to an aristocratic family, Algernon Sidney became one of the leading republican theorists of the late 17th century whose works exerted a considerable influence on 18th century America. He served in the army during the 1640s and 1650s, sat in Parliament where he voted against the execution of the king, lived in exile in Holland and France for much of the Restoration (of the Stuart monarchy after 1660), and in the late 1670s and early 1680s became involved in various plots against the Crown which led to arrest and execution for high treason. His major and best known work is his Discourses concerning Government (written 1679-1683, published 1698) which Sidney wrote to refute Sir Robert Filmer’s (1588-1653) patriarchal theory of the monarchy, Patriarcha, or the Natural Power of Kings, which had appeared in 1680. Filmer’s work also prompted John Locke to write part of the Two Treatises of Government so it is be doubly famous for having prompted into being two classics of the republican Commonwealthman tradition which was to so influence the 18th century, especially those in America who were challenging the right of the British king to rule over them. Sidney’s criticisms of the arbitrary and despotic powers of the restored Stuart monarchy so inflamed their supporters that Sidney was singled out for persecution and its was with delight that they found in his rooms an unpublished manuscript of his Discourses which they used as evidence of treason against him, the judge arguing that “scribere est agere” (to write is to act - i.e that writing in favour of an act is the same as carrying out that act). Sidney lost the case and was duly beheaded, but was spared the indignity of having his body drawn and quartered. The Discourses were published a few years after his execution (1698) and again by Thomas Hollis in 1762. Copies of Sidney’s work were widely circulated and read in the American colonies thus making it one of the key texts for understanding the thinking of the American revolutionaries.

Source

Algernon Sidney, Discourses Concerning Government, ed. Thomas G. West (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund 1996). [Source at OLL website]

Adam Smith on the dangers of faction and privilege seeking (1759) ↩

Adam Smith (1723 – 1790)

Smith argues that “hostile factions” are constantly struggling to gain new government privileges and protect the ones they already have:

Every independent state is divided into many different orders and societies, each of which has its own particular powers, privileges, and immunities. Every individual is naturally more attached to his own particular order or society, than to any other. His own interest, his own vanity, the interest and vanity of many of his friends and companions, are commonly a good deal connected with it. He is ambitious to extend its privileges and immunities. He is zealous to defend them against the encroachments of every other order of society

Upon the manner in which any state is divided into the different orders and societies which compose it, and upon the particular distribution which has been made of their respective powers, privileges, and immunities, depends, what is called, the constitution of that particular state.

Upon the ability of each particular order or society to maintain its own powers, privileges, and immunities, against the encroachments of every other, depends the stability of that particular constitution. That particular constitution is necessarily more or less altered, whenever any of its subordinate parts is either raised above or depressed below whatever had been its former rank and condition.

All those different orders and societies are dependent upon the state to which they owe their security and protection. That they are all subordinate to that state, and established only in subserviency to its prosperity and preservation, is a truth acknowledged by the most partial member of every one of them. It may often, however, be hard to convince him that the prosperity and preservation of the state requires any diminution of the powers, privileges, and immunities of his own particular order of society. This partiality, though it may sometimes be unjust, may not, upon that account, be useless. It checks the spirit of innovation. It tends to preserve whatever is the established balance among the different orders and societies into which the state is divided; and while it sometimes appears to obstruct some alterations of government which may be fashionable and popular at the time, it contributes in reality to the stability and permanency of the whole system.

About this Quotation

In his Theory of Moral Sentiments (1759) Smith has much to say about the dangers posed to society by factions, party-men, and men of system. Here he acknowledges that every faction tries to gain and then protect their “own particular powers, privileges, and immunities” but seems to be satisfied that, if there are enough of them, no one faction will become dominant and thereby pose a threat to the political equilibrium of the state. This seems to be a rather optimistic assessment which he tries to address a few passages further on. He raises the problem of what happens if, “amidst the turbulence and disorder of faction” one “successful party” which has become imbued with “a certain spirit of system” manages to become the dominant one. Driven by ideological “fanaticism” this party might decide to completely “remodel the constitution” and use violence to do so. Smith then introduces his wonderful analogy of the hand of the central planner arranging human beings on “the great chess-board of human society” which would most likely lead to dire consequences for humanity. Perhaps in order to avoid the dangers of the latter, it would be better to remove the temptations offered to the various factions by the state in the first place.

Source

Adam Smith, Essays On, I. Moral Sentiments: II. Astronomical Inquiries; III. Formation of Languages; IV. History of Ancient Physics; V. Ancient Logic and Metaphysics; VI. The Imitative Arts; VII. Music, Dancing, Poetry; VIII. The External Senses; IX. English and Italian Verses, ed. Joseph Black and James Hutton (London: Alex. Murray & Son, 1869). [Source at OLL website]

Yves Guyot warns that a new ruling class of managers and officials will emerge in the supposedly “classless” socialist society of the future (1908) ↩

Yves Guyot (1843 – 1928)

The French economist and politician Yves Guyot (1843-1928) very quickly realised that socialism would not lead to a peaceful and classless society as promised, but would result in a new form of class rule of party officials:

The class war, says the “Communist Manifesto,” must result in the abolition of classes, but it will establish “the proletariat as the ruling class” (§52). Accordingly, if the proletariat be a ruling class, there will be a class which oppresses and a class which is oppressed. The classes will not have disappeared, they will merely have changed their positions. The “Communist Manifesto” makes it a supreme consideration to “centralise the means of production in the hands of the State.” (§52).

There will be at least two classes, one consisting of officials to distribute the burdens and the results of labour, the other of the drudges to execute their commands. Such a dispensation would not bring with it social peace, for political would take the place of economic competition.

So far only three means of calling human activity into being have been recognised, those of coercion, allurement and remuneration. Coercion is servile labour—work, or strike. The allurement of high office, decorations, rank or a crown may complete the coercion; we see the two employed together in the schools, the Church and the Army. Their success implies two conditions, on the one hand the art to command, and on the other the spirit of discipline. But what are these? They are the conditions which underlie the military spirit, founded upon respect for a hierarchy. Order, in a Communist Society, requires the virtues of convents and of barracks. But establishments of this kind consume without producing, and have furthermore eliminated the question of women and children.

In a collectivist society will there be citizens with electoral rights? Presumably; but the ballot is but an instrument for classifying parties, so that there will be parties, majorities and minorities; parties which will attain to power and others which will be in opposition.