“'I Pencil': An Intellectual History (1644-1958)”

By David M. Hart

[Created: 2 August, 2014]

[Revised: 29 March, 2025] |

This is part of a collection of Papers by David M. Hart

Introduction

Leonard Read (1898-1983) was the founder and president of the Foundation for Economic Education (FEE) [online elsewhere], which for many years was located in Irvington-on-Hudson near New York city. He devoted his life to educating people about the nature of individual liberty and free markets which he did by means of publications such as The Freeman magazine which was founded in 1950 by John Chamberlain, Henry Hazlitt, and Suzanne La Follette, and the taken over and run by FEE in 1956. One of his best known popular essays was “I, Pencil,” which was first published in the December 1958 issue and it has influenced many thousands of readers ever since. [1]

It is the story, "as told to Leonard E. Read," of how a simple pencil, told in its own words, came into being without any one person knowing how to make one. Read cleverly made use of this story to simplify a number of complex economic ideas so that ordinary readers could understand how a free market in pencils functioned, and by extension, markets for every other product as well. It was republished in 1998 as a pamphlet with an introduction by the Nobel Prize winning economist Milton Friedman (1976) who had featured the story in his PBS documentary and book Free to Choose in 1980. [2]

Read came to write "I, Pencil" after coming across the writings of the French economist Frédéric Bastiat in the 1940s when he was working with R.C. Hoyles in Los Angeles in republishing Bastiat's works, and Friedrich Hayek's essay "The Use of Knowledge in Society" (1945). [4] He wanted to use the method of the outstanding popularizer of economic ideas, Bastiat, to make Hayek's sophisticated theory of knowledge and prices accessible to ordinary readers. Read would even adapt one of Bastiat's essays, The Law (1850), into an illustrated, almost cartoon-like edition sometime in the late 1940s [4] and later be instrumental in translating and publishing much more of Bastiat's writings in the early 1960s. Thus, we should see "I, Pencil" as one of several attempts Read made to popularise complex economic ideas, and it is without doubt his most successful one.

However, Read's was only one of many similar attempts by economists to explain themselves by means of amusing or simplified stories. It was a rhetorical device which attracted many famous economists, not all of whom had the literary talent of a Bastiat to pull it off. However, their attempts are instructive. [5] This anthology brings together several of these efforts, along with Read's classic version, in order to show the intellectual history of his best known work of popularization. It includes selections from the works of an anonymous Englishman in the 17thC, the Dutch-English writer Bernard Mandeville (1670-1733), the economist Adam Smith (1723-1790), the businessman and economist J.B. Say (1767-1832), one of the leading speakers of the Anti-Corn Law League William Fox (1786-1864), the economist Frédéric Bastiat (1801-1850), and Leonard Read (1898-1983). I have given them new titles in keeping with the tone of Leonard Read's original story:

- Anon, "I, Mill Horse" (1644)

- Bernard Mandeville, "I, Beehive" (1714)

- Adam Smith, "I, Pin-Maker" (1776)

- Jean-Baptiste Say, "I, Playing Card Maker" (1828)

- William Fox, “I, Foreigner” (1844)

- Frédéric Bastiat, “I, Carpenter” (1848)

- Frédéric Bastiat, "I, Broken Window" (1850)

- Leonard Read, “I, Pencil” (1958)

I think the important economic ideas Read and his predecessors were trying to explain with their stories are the following:

- that no one person knows how to make an object as simple as a pin or a pencil without complex social cooperation operating in a system of free pricing (Hayek's theory of the problem of knowledge, and the coordinating effects of free prices)

- that no one person can physically make an object as simple as a pin or a pencil without making use of the skills, labour, and capital of other people (the principle of the division of labor)

- that trade makes it possible for consumers to enjoy the benefits of buying products from all over the world everyday (the principle of free trade, both domestic and international, and the idea of comparative advantage)

- that the self-interest of producers leads them to satisfy voluntarily the needs of self-interested consumers in mutually beneficial exchanges (Adam Smith's notion of the invisible hand, Bastiat's idea of the "harmony" of the free market, and Hayek's idea of spontaneous order)

- that some individuals (entrepreneurs) see profit opportunities and therefore step forward to coordinate the financing, production, and sale of these goods to consumers without the need for central planning by a government bureaucracy (Kirzner's theory of entrepreneurship and Mises theory of the impossibility of rational central planning)

The rhetorical devices they used varied according to time, place, and circumstances and ranged from a talking pencil and a horse, a fly-on-the-wall description of a manufacturing process in a pin or a card making factory, a show-and-tell of the things owned by an aristocratic land-owner, the things around a carpenter as he goes about his business, the difficulties faced by a shopkeeper who has his window smashed, or the activities which take place within a bee-hive. Whatever the fictional device they use, they all share some deep insights into how societies and economies function, and a certain skill in telling a story about complex theoretical ideas.

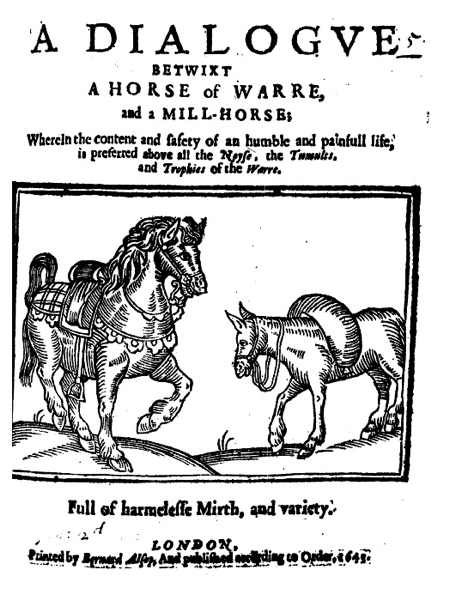

Anon., A Dialogue betwixt a Horse of Warre, and a Mill-Horse (1644)↩

Source

Anon., A Dialogue betwixt a Horse of Warre, and a Mill-Horse; Wherein the content and safety of an humble and painfull life, is preferred above all the Noyse, the Tumults, and Trophies of the Warre. Full of harmelesse Mirth, and variety. (London, Printed by Bernard Alsop, and published according to order, 1643).

The title page of the pamphlet:

Introduction

The pamphlet consists of a long conversation between “the Cavalier’s Warre Horse” and “the Country-mans Mill-Horse”: where Cavaliers (Royalists) were supporters of the absolutist monarchy of Charles I, and Country-men (Roundheads) were supporters of Parliament (which was divided into constitutional monarchists and more radical groups who were Levellers or republicans).

More generally the Mill horse might be seen as representing the ordinary working person who most of the time had to pay the taxes and supply the food (compulsory billeting of soldiers), but who in time of war had to put down their farm tools and fight for what they believed in. While the War horse represents those who were in the King’s army as professional officers and soldiers and who made fighting their life’s work.

During the conversation the Warre horse mocks what the Mill horse has to do, and the Mill horse lists the crimes committed and the suffering of ordinary people caused by the Warre horse. A contrast is made between the ideal of the honour and nobility of war and the courage of the soldier in battle vs. the ideal of the slow, mundane tasks of earning a living and living peaceably with others.

The Mill Horse says:

What though upon my back I carry sacks;

Thy meat is plunderd out of barnes and stacks;

While thou dost feed on stolen Dates and Hay

The wronged Farmers curse the strength away

Of all thy Diet, often wishing that

Diseases may consume thy ill-got fat.

Therefore recant and never more appeare

In field a Champion for the Cavallier;

Let not his spurre nor false fame prick thee on

To fight in unjust warres as thou hast done.

The two horses trade insults with other, with the Mill horse accusing the Cavaliers of raping and pillaging , and the Warre horse calling the Mill horse “dull and tedious” and a liar. Eventually the Mill horse says he hopes the Warre horse will be eaten by dogs for his crimes; while the Warre horse threatens to use violence against him - “To kick thee into manners with my heeles.”

The Mill horse patiently replies that:

… the war-horse are

Guilty of blood-shed, in this cruell war

And yet the Cavalliers horse as I beare

At Kenton field beshit themselves for feare.

And the Cavalliers being kill’d, they run about

The field to seek another master out,

Therefore love war, and have of wounds thy fill.

While I in Peace doe walk unto the Mill;

I will be alwayes true unto my selfe,

And love the Kingdome and the Commonwealth.

A discourse between the Cavalliers Warre Horse, and the Country-mans Mill-Horse.

Cav. hors.

WEll met old Mill-Horse or indeed an Asse,

I must instruct thee before we doe passe

How to live bravely; look on me and view

My Bridle and my Saddle faire and new;

Warre doth exalt me, and by it I get

Honour, while that my picture is forth set

Cut out in Brasse, while on my back I beare

Some Noble Earle or valiant Cavallier.

Come therefore to the Wars, and doe not still

Subject thy selfe to beare Sacks to the Mill.

Mil-hors.

Despite me not thou Cavalliers War-Horse

For thouogh to live I take an idle course,

Yet for the common-wealth I alwayes stand,

And am imploy’d for it, though I’m nam’d

A Mill-Horse, I am free and seem not under

Malignants that doe townes and houses plunder.

Transported on thy back, while thou must be

Valse guilty of their wrong, and injurie.

Done to their country, while without just cause,

Thou fightest for the King against the Lawes.

Against Religion, Parliament and all,

And least the Pope and Bishops downe would fall.

Thou art expos’d to battle, but no thanks,

Thou bast at all when thou dost break the Ranks

Of our stout Muskettiers, whose bullets flye

In showres, as in the fight at Newbery,

And force thee to retreat with wounds, or lame,

Is this the glory of thy halting fame.

Whereof thou dost so bragge [Editor: illegible word] beside thy fault

Of fighting for them who have alwayes fought,

Against the common-wealth, is such a sin,

That doth stick closer to thee then thy skin,

What though upon my back I carry sacks;

Thy meat is plunderd out of barnes and stacks;

While thou dost feed on stolen Dates and Hay

The wronged Farmers curse the strength away

Of all thy Diet, often wishing that

Diseases may consume thy ill-got fat.

Therefore recant and never more appeare

In field a Champion for the Cavallier;

Let not his spurre nor false fame prick thee on

To fight in unjust warres as thou hast done.

Cav. hors.

Fame is not what I aime at, but the knowne

Right of the King, the trumpet that is blowne

Unto the Battell doth not give me more

Courage, then what I had in him before,

As if we did partake of more then sense

And farre exceeded mans intelligence,

In stooping unto Kings, and doe prove thus

Our selves descended from Bucephalus,

That Horse who did no loyall duty lack

But kneeling downe received on his back

Great Alexander, while men kick and fling

Against the power of so good a King

As time hath blest us with, O let this force

A change in thee who art a dull Mill-horse.

Thou art no Papist being without merit,

Nor zealous Brownist, for thou dost want spirit.

But with a Halter ty’d to block or pale,

Dost pennance, while thy master drinks his Ale

In some poore Village; such a poore thing are thou

Who Gentry scorne, beare till thy ribs doe bow

Burthens of corne or meale, while that Kings are

My Royall Masters both in Peace and Warre.

Mil-hors.

Boast not of happy fortune, since time brings

A change to setled States and greatest Kings,

England was happy; peace and plenty too

Did make their rich abode here, but now view

The alteration, Warrs hath brought in woe.

And sad destruction doth this land o’flown

Now thou art proud, but if this warre in peace

Should land thy high ambition would then cease;

Thy strength and courage would find no regard,

Thy plundering service should get no reward,

Although in warrs thou trample down and kill

Thy foe in age thou shalt beare sacks to Mill

As I doe now, and when thy skinne is grizzle

Groan underneath thy burthen, fart, and fizzle

Like an old horse, a souldier of the Kings,

“All imploy’d valour sad repentance brings,

When thou art lame, and wounded in a fight

Not knowing whether thou dost wrong or right,

Or what is the true ground of this sad warre

Where King and subjects both ingaged are;

Both doe pretend the justnesse of their cause.

One for Religion, Liberty, and Lawes;

Doth stand, while that the King doth strive again

His Right and due Prerogative to maintaine;

The king keeps close to this, while subjects be

Growne mad to eclipse the sonne of Majestie

By enterposing differences; how canst thou judge

Where the fault is: both at each other grudge,

I know that this discourse is farre too high

For us, yet now to talke of Majesty;

In boldest manner is a common thing

While every cobler will condemn a King,

And be so politick in their discourse.

Yet know no more then I a poore Mill-horse;

Who for the common-wealth doe stand and goe,

Would every commonwealths man did doe so.

Cav hors.

Mill-horse in this thy space and speech agree

Both wanting spirit dull and tedious bee;

The King and commonwealth are vexed theames

Writ on by many; prethee think on Beanes

And Oates well ground, what need hast thou to care

How the deplored commonwealth doth fare;

For policy this rule in mind doth keep,

“Laugh when thou hast made others grieve and weep

What care we how the State of things doe goe?

“While thou art well, let others feele the woe.

If I have store of provender I care not,

Let Cavalliers full plunder on and spare not,

When Ockingham was burned I stood by

And like each widdowes wept at ne’re an eye,

When the town burnt a fellow said in leather

“He lov’d to see a good fire in cold weather;

And with the simple clowne I doe say still

“If I doe well I care not who doth ill;

For with the Cavalliers I keep one course,

And have no more Religion then a Horse,

I care not for the Liberty nor Lawes.

Nor priviledge of Subjects, nor the cause,

Let us stand well affected to good Oates,

While that the ship of State and Kingdome floates

On bloody waves, the staved rack shall be

Crammeed with hey, a commonwealth to me.

Mill-hors.

Alasse I pitty thee thou great war-horse

Who art like Cavalliers without remorse:

The sad affliction which the Kingdome feeles,

Regarding not, thou caste it at thy heeles

And so dost prove that horses have no braine

Or if they have they little wit containe.

Unto the Kingdomes tale thy prick eares lend

Whose griefe I will describe, and right defend.

Cav-hors.

Thou defend right, thy right to the high way

Is lost, as sure as thou dost live by hey,

In telling of a tale without all doubt

Thou needs must stumble, and wilt soon run out

Of breath and sense, good Mill-horse, therefore prethee

Leave tales, there are too many tales already,

That weekly flye with more lies without faile

Then there be haires within a horses taile;

And if the writers angry be I wish,

You would the Cavalliers horse arse both kisse,

Not as the Miller thy back doth kisse with whip,

But as a Lover doth his Mistresse sip;

For know the Cavalliers brave warlick horse

Scornes vulgar Jades, and bids them kisse his arse.

Mill-hors.

Thou pamperd Jade that liv’st by plunderd oates

My skin’s as good as thine and worth ten groates,

Though slow of foot, I come of a good kind,

Of Racers, gotten by the boistrous wind

When the mare turned her back side in the mouth

Of Boreas, being Northerne breed not South.

The Millers horse before the warres began,

Would take the way of Lord or Gentleman;

And when Peace shall Malignants keep in aw,,

I shall see thee in Cauch or Dung-cart draw,

Cav. hors.

I scorne thy motion, after this sad Warre,

Perhaps I may draw in some Coach or Carre;

And which doth grieve me, Cavaliers most high-born

I may be forced to draw on to Tiburne:

In time of Peace my blood shall not be spilt,

But like to Noble Beere, shall run at Tilt.

In Peace I serve for Triumphs, more then that

I shall be made a Bishop, and grow fat,

As Archey said, when Bishops rul’d ’twas worse,

That had no more Religion then a Horse.

But thou shalt weare thy selfe out, and be still

An everlasting Drudge unto some Mill.

Mil-hors.

No matter, I wil spend my life and health,

Both for my Country and the common-wealth,

And it is Prince-like (if well understood)

To be ill-spoken off for doing good,

And if a horse may shew his good intent,

Some Asses raile thus at the Parliament.

Scorn is a burthen laid on good men still.

Which they must beare, as I do Sackes to Mill:

But thou delighted to bear trumpets rattle.

An animall rushing into lawlesse battle;

If thou couldst think of those are slain and dead,

Thy skin would blush, and all thy haires look red

With blood of men, but I do with for peace,

On that condition Dogs might eate thy flesh.

Then should the Mil-horse meat both fetch and bring.

Towns brew good Ale, and drink healthe to the King.

Cav. hors.

Base Mill-horse have I broke my bridle, where

I was tyed by my Master Cavaliere

To come and prattle with thee, and doest thou

Wish Dogs might eat my flesh? I scorn thee now.

My angry sense a great desire now feeles.

To kick thee into manners with my heeles.

But for the present I will curb my will.

If thou wilt tell me some newes from the mill.

Mil-hors.

If thou wilt tell me newes from Camp & Court,

Ile tell thee Mill-newes that shall make thee sport.

Cav. hors.

If Country news thou wilt relate and shew me,

Halters of love shall binde me fast unto thee,

Mil-hors.

It chanced that I carried a young Maid

To Mill, and was to stumble much afraid,

She rid in handsome manner on my back,

And seem’d more heavie then the long meale sacke

On which she sate, when she alighted, I

Perceiv’d her belly was grown plump and high;

I carried many others, and all were

Gotten with childe still by the Cavaleer,

So that this newes for truth I may set downe,

There’s scarce a Maid left in a Market towne;

An woman old with Mufler on her chin,

Did tell the Miller she had plundered been

Thrice by the Cavaliers, and they had taken.

Her featherbeds, her brasse, and all her bacon,

And she her daughter Bridget that would wed

Clodes sonne was plundered of her maidenhead,

Besides I heare your Cavaliers doe still,

Drinke sacke like water that runs from the Mill;

We heare of Irish Rebels comming over,

Which was a plot that I dare not discover.

And that the malignant Army of the King,

Into this Land blinde Popery would bring.

Cav. hors.

Peace, peace, I see thou dost know nothing now,

Thy fleeting jests I cannot well allow;

And there are Mercuriés abroad that will,

Tell better news then a horse of the Mill;

But I will answer thee, and tell thee thus,

Thou lyest as bad as ere did Aulicus.

Who though he writ Court-newes ile tell you what,

Heele lye as fast as both of us can trot.

You tell of Maydens that have been beguild,

And by the Cavaleers are got with childe,

And hast not thou when thou wast fat and idle,

Often times broke thy halter and thy bridle,

And rambled over hedge and ditch to come,

Unto some Mare, whom thou hast quickly wonne

To thy desire, and leapt her in the place,

Of dull Mill-horses to beget a race;

While that the Cavaliers when they do fall

To worke, will get a race of souldiers all.

It had been newes whereas I would have smilde,

If the maids had got the Cavalliers with childe.

Mill-hors.

I ramble over hedge, thou meanst indeed

The Cavalliers, who were compelt’d with speed

Both over hedge and ditch away to flye.

When they were lately beat at Newbery.

The Proverb to be true is prov’d by thee

That servants like unto their masters bee;

Those plundering devills on thy back doe ride,

Have fill’d thee with a pamper’d spirit of pride,

And thou hast eaten so much Popish Dates,

That in thy belly thou hast got three Popes;

The great Grand-father of that race did come

That bore Pope Joane in triumph through Rome

I beare to Mill of corne a plump long sack.

Thou carried a great Pluto on thy back.

Oh Cavallier, and who can then abide thee.

When that malignant Fooles and Knaves doe ride thee.

From town to town, and plunder where they come,

The country is by Cavalliers undone.

And these thy masters are, who fight and kill

And seek the blood of Protestants to spill;

For thus the newes abroad both alwayes runns,

That the Kings forces are in horse most strong.

Whereby it doth appeare the war-horse are

Guilty of blood-shed, in this cruell war

And yet the Cavalliers horse as I beare

At Kenton field beshit themselves for feare.

And the Cavalliers being kill’d, they run about

The field to seek another master out,

Therefore love war, and have of wounds thy fill.

While I in Peace doe walk unto the Mill;

I will be alwayes true unto my selfe,

And love the Kingdome and the Commonwealth.

Cav. hors.

Mill-horse, because thou shew’st thy railing wits

Ile give thee a round answer with some kicks,

Which Ile bestow upon thee, but I am undone,

Yonder my master Cavallier doth come

To fetch me back, and Yonder too I see

The Miller comming for to take up thee;

If thou lik’st not my discourse very well,

Mill-horse take up my taile, and so farwell.

FINIS.

Bernard Mandeville, "I, Beehive" (1705)↩

Introduction

Bernard Mandeville (1670-1733) was born in Holland in 1670 into a family of physicians and naval officers. He received his degree of Doctor of Medicine at Leiden in 1691 and began to practice as a specialist in nerve and stomach disorders, his father’s specialty. Perhaps after a tour of Europe, he ended up in London, where he soon learned English and decided to stay. He married in 1699, fathered at least two children, and brought out his first English publication in 1703 (a book of fables in the La Fontaine tradition). He wrote works on medicine (A Treatise of the Hypochondriack and Hysterick Passions, 1711), poetry (Wishes to a Godson, with Other Miscellany Poems, 1712), and religious and political affairs (Free Thoughts on Religion, the Church, and National Happiness, 1720). He died in 1733. His most famous work, The Fable of the Bees, or Private Vices, Publick Benefits, came out in more than half a dozen editions beginning in 1714 (the poem The Grumbing Hive upon which it was based appeared in 1705) and became one of the most enduringly controversial works of the eighteenth century for its claims about the moral foundations of modern commercial society.

Bernard Mandeville uses a fable about bees to show how prosperity and good order comes about through spontaneous order. This poem, which formed the basis of Mandeville’s longer work The Fable of the Bees, is a clever and witty attempt to make a profound point of economic theory, namely that structure and order can arise from individual action and does not have to be imposed from above by a King (in this case shouldn’t it be a “Queen”?).

The Fable of the Bees

Source: Bernard Mandeville, The Fable of the Bees or Private Vices, Publick Benefits, 2 vols. With a Commentary Critical, Historical, and Explanatory by F.B. Kaye (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 1988). Vol. 1. [online elsewhere].

A Spacious Hive well stockt with Bees,

That liv’d in Luxury and Ease;

And yet as fam’d for Laws and Arms,

As yielding large and early Swarms;

Was counted the great Nursery

Of Sciences and Industry.

No Bees had better Government,

More Fickleness, or less Content:

They were not Slaves to Tyranny,

Nor rul’d by wild Democracy;

But Kings, that could not wrong, because

Their Power was circumscrib’d by Laws.These Insects liv’d like Men, and all

Our Actions they perform’d in small:

They did whatever’s done in Town,

And what belongs to Sword or Gown:

Tho’ th’ Artful Works, by nimble Slight

Of minute Limbs, ’scap’d Human Sight;

Yet we’ve no Engines, Labourers,

Ships, Castles, Arms, Artificers,

Craft, Science, Shop, or Instrument,

But they had an Equivalent:

Which, since their Language is unknown,

Must be call’d, as we do our own.

As grant, that among other Things,

They wanted Dice, yet they had Kings;

And those had Guards; from whence we may

Justly conclude, they had some Play;

Unless a Regiment be shewn

Of Soldiers, that make use of none.

Text: Mandeville on the social cooperation which is required to produce a piece of scarlet cloth (1723)

Introduction

In this Addendum to his “Fable of the Bees” (1705) Mandeville provides an early account of how interdependent markets had already become by the early 18th century. Fifty years later Adam Smith would explain that this cooperation, which was not planned by any individual person, was the result of the operation of an “invisible hand” which seemed to guide the activities of self-interested, profit-seeking individuals to produce a socially useful outcome which was not their primary consideration. Mandeville’s example was a piece of fashionable red cloth which, on the surface, might appear to be a rather useless luxury item, but which brought together thousands of dispersed individuals, or as he termed it “so many Hands, honest industrious labouring Hands”, from all over the world to produce items of enormous value for all of them. He also argues, prefiguring Adam Ferguson and Adam Smith, that these labours, by peacefully combining “so many voluntary Actions, belonging to different Callings and Occupations that Men are brought up to for a Livelihood,” results in a prosperous society “in which every one Works for himself, how much soever he may seem to Labour for others.”

In Mandeville’s view, this was just another example of how a “private vice” like “Female Luxury” produces a “public benefit” which in this case was employment for the poor. Mandeville was only the first of many free market advocates to make this point: compare it with Bastiat’s story of “The Cabinet Maker & the Student” in Economic Harmonies (1850) and Leonard Read’s “I, Pencil” (December 1958).

Text 2: Remark Y.) T’ enjoy the World’s Conveniencies. Page 23. Line 3.

THAT the Words Decency and Conveniency were very ambiguous, and not to be understood, unless we were acquainted with the Quality and Circumstances of the Persons that made use of them, has been hinted already in Remark (L.) The Goldsmith, Mercer, or any other of the most creditable Shopkeepers, that has three or four thousand Pounds to set up with, must have two Dishes of Meat every Day, and something extraordinary for [279] Sundays. His Wife must have a Damask Bed against her Lying-in, and two or three Rooms very well furnished: The following Summer she must have a House, or at least very good Lodgings in the Country. A Man that has a Being out of Town, must have a Horse; his Footman must have another. If he has a tolerable Trade, he expects in eight or ten Years time to keep his Coach, which notwithstanding he hopes that after he has [248] slaved (as he calls it) for two or three and twenty Years, he shall be worth at least a thousand a Year for his eldest Son to inherit, and two or three thousand Pounds for each of his other Children to begin the World with; and when Men of such Circumstances pray for their daily Bread, and mean nothing more extravagant by it, they are counted pretty modest People. Call this Pride, Luxury, Superfluity, or what you please, it is nothing but what ought to be in the Capital of a flourishing Nation: Those of inferior Condition must content themselves with less costly Conveniencies, as others of higher Rank will be sure to make theirs more expensive. Some People call it but Decency to be served in Plate, and reckon a Coach and six among the necessary Comforts of Life; and if a Peer has not above three or four thousand a Year, his Lordship is counted Poor.

[280]

SINCE the first Edition of this Book, several have attack’d me with Demonstrations of the certain Ruin, which excessive Luxury must bring upon all Nations, who yet were soon answered, when I shewed them the Limits within which I had confined it; and therefore that no Reader for the future may misconstrue me on this Head, I shall point at the Cautions I have given, and the Proviso’s I have made in the former as well as this present Impression, and which if not overlooked, must prevent all rational Censure, and obviate several Objections that otherwise might be made against me. I have laid down as Maxims never to be departed from, that the Poor should be kept strictly to Work, and that it was Prudence to relieve their Wants, but Folly to cure them; that Agriculture and Fishery should be promoted in all their Branches in order to render Provisions [249] , and consequently Labour cheap. I have named Ignorance as a necessary Ingredient in the Mixture of Society: From all which it is manifest that I could never have imagined, that Luxury was to be made general through every part of a Kingdom. I have likewise [281] required that Property should be well secured, Justice impartially administred, and in every thing the Interest of the Nation taken care of: But what I have insisted on the most, and repeated more than once, is the great Regard that is to be had to the Balance of Trade, and the Care the Legislature ought to take that the Yearly Imports never exceed the Exports; and where this is observed, and the other things I spoke of are not neglected, I still continue to assert that no Foreign Luxury can undo a Country: The height of it is never seen but in Nations that are vastly populous, and there only in the upper part of it, and the greater that is the larger still in proportion must be the lowest, the Basis that supports all, the multitude of Working Poor.

Those who would too nearly imitate others of Superior Fortune must thank themselves if they are ruin’d. This is nothing against Luxury; for whoever can subsist and lives above his Income is a Fool. Some Persons of Quality may keep three or four Coaches and Six, and at the same time lay up Money for their Children: while a young Shopkeeper is undone for keeping one sorry Horse. It is impossible there should be a rich Nation without Prodigals, yet I never knew a City so full of Spendthrifts, but [282] there were Covetous People enough to answer their Number. As an Old Merchant breaks for having been extravagant or careless a great while, so a young Beginner falling into the same Business gets an Estate by being saving or more industrious before he is Forty Years- [250] Old: Besides that the Frailties of Men often work by Contraries: Some Narrow Souls can never thrive because they are too stingy, while longer Heads amass great Wealth by spending their Money freely, and seeming to despise it. But the Vicissitudes of Fortune are necessary, and the most lamentable are no more detrimental to Society than the Death of the Individual Members of it. Christnings are a proper Balance to Burials. Those who immediately lose by the Misfortunes of others are very sorry, complain and make a Noise; but the others who get by them, as there always are such, hold their Tongues, because it is odious to be thought the better for the Losses and Calamities of our Neighbour. The various Ups and Downs compose a Wheel that always turning round gives motion to the whole Machine. Philosophers, that dare extend their Thoughts beyond the narrow compass of what is immediately before them, look on the alternate Changes in the Civil Society no otherwise than they do on the risings and fallings of the Lungs; the latter of which are as much a Part of Respiration in the more perfect Animals as the first; so that [283] the fickle Breath of never-stable Fortune is to the Body Politick, the same as floating Air is to a living Creature.

Avarice then and Prodigality are equally necessary to the Society. That in some Countries, Men are more generally lavish than in others, proceeds from the difference in Circumstances that dispose to either Vice, and arise from the Condition of the Social Body as well as the Temperament of the Natural. I beg Pardon of the attentive Reader, if here in behalf of short Memories I repeat some things, the Substance of which they have already seen in Remark (Q.) More Money than Land, heavy Taxes and scarcity of Provisions, Industry, Laboriousness, an active and stirring Spirit, Ill-nature and Saturnine Temper; Old Age, [251] Wisdom, Trade, Riches, acquired by our own Labour, and Liberty and Property well secured, are all Things that dispose to Avarice. On the contrary, Indolence, Content, Good-nature, a Jovial Temper, Youth, Folly, Arbitrary Power, Money easily got, Plenty of Provisions and the Uncertainty of Possessions, are Circumstances that render men prone to Prodigality: Where there is the most of the first the prevailing Vice will be Avarice, and Prodigality where the other turns the Scale; but a National Frugality there never was nor never will be without a National Necessity.

[284]

Sumptuary Laws may be of use to an indigent Country, after great Calamities of War, Pestilence, or Famine, when Work has stood still, and the Labour of the Poor been interrupted; but to introduce them into an opulent Kingdom is the wrong way to consult the Interest of it. I shall end my Remarks on the Grumbling Hive with assuring the Champions of National Frugality that it would be impossible for the Persians and other Eastern People to purchase the vast Quantities of fine English Cloth they consume, should we load our Women with less Cargo’s of Asiatick Silks.

Adam Smith, "I, Pin-Maker" (1776)↩

Source

Adam Smith, An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations by Adam Smith, edited with an Introduction, Notes, Marginal Summary and an Enlarged Index by Edwin Cannan (London: Methuen, 1904). Vol. 1. Book I, Chapter I: Of the Division of Labour [Online] (EnglishClassicalLiberals/Smith/WoN/1904-Cannan/index.html#WoN-01_235).

Text

THE greatest improvement in the productive powers of labour, and the greater part of the skill, dexterity, and judgment with which it is any where directed, or applied, seem to have been the effects of the division of labour.

The effects of the division of labour, in the general business of society, will be more easily understood, by considering in what manner it operates in some particular manufactures. It is commonly supposed to be carried furthest in some very trifling ones; not perhaps that it really is carried further in them than in others of more importance: but in those trifling manufactures which are destined to supply the small wants of but a small number of people, the whole number of workmen must necessarily be small; and those employed in every different branch of the work can often be collected into the same workhouse, and placed at once under the view of the spectator. In those great manufactures, on the contrary, which are destined to supply the great wants of the great body of the people, every different branch of the work employs so great a number of workmen, that it is impossible to collect them all into the same workhouse. We can seldom see more, at one time, than those employed in one single branch. Though in such manufactures, therefore, the work may really be divided into a much greater number of parts, than in those of a more trifling nature, the division is not near so obvious, and has accordingly been much less observed.

To take an example, therefore, from a very trifling manufacture; but one in which the division of labour has been very often taken notice of, the trade of the pin-maker; a workman not educated to this business (which the division of labour has rendered a distinct trade), nor acquainted with the use of the machinery employed in it (to the invention of which the same division of labour has probably given occasion), could scarce, perhaps, with his utmost industry, make one pin in a day, and certainly could not make twenty. But in the way in which this business is now carried on, not only the whole work is a peculiar trade, but it is divided into a number of branches, of which the greater part are likewise peculiar trades. One man draws out the wire, another straights it, a third cuts it, a fourth points it, a fifth grinds it at the top for receiving the head; to make the head requires two or three distinct operations; to put it on, is a peculiar business, to whiten the pins is another; it is even a trade by itself to put them into the paper; and the important business of making a pin is, in this manner, divided into about eighteen distinct operations, which, in some manufactories, are all performed by distinct hands, though in others the same man will sometimes perform two or three of them. I have seen a small manufactory of this kind where ten men only were employed, and where some of them consequently performed two or three distinct operations. But though they were very poor, and therefore but indifferently accommodated with the necessary machinery, they could, when they exerted themselves, make among them about twelve pounds of pins in a day. There are in a pound upwards of four thousand pins of a middling size. Those ten persons, therefore, could make among them upwards of forty-eight thousand pins in a day. Each person, therefore, making a tenth part of forty-eight thousand pins, might be considered as making four thousand eight hundred pins in a day. But if they had all wrought separately and independently, and without any of them having been educated to this peculiar business, they certainly could not each of them have made twenty, perhaps not one pin in a day; that is, certainly, not the two hundred and fortieth, perhaps not the four thousand eight hundredth part of what they are at present capable of performing, in consequence of a proper division and combination of their different operations.

In every other art and manufacture, the effects of the division ofThe effect is similar in all trades and also in the division of employments. labour are similar to what they are in this very trifling one; though, in many of them, the labour can neither be so much subdivided, nor reduced to so great a simplicity of operation.

Jean-Baptiste Say, "I, Playing Card Maker" (1828)↩

Source

Cours complet d'économie politique pratique. Ouvrage destiné à mettre sous les yeux des hommes d'état, des propriétaires fonciers et des capitalistes, des savants, des agriculteurs, des manufacturiers, des négociants, et en général de tous les citoyens l'économie des sociétés, Volume 1. 2nd ed. Horace Say (Paris:Guillaumin, 1840). 3rd ed. 1852. vol. 1 CHAPITRE XV. De la Division du travail, pp. 165-166.

Introduction

Say prefers another example instead of the pin factory in order to make his point about the benefits of the division of labour ("séparation des occupations") - this time it is the manufacture of playing cards ("les cartes à jouer"). [6] The manufacture of playing cards had been highly regulated under the old regime but early in the revolution (1791) all such restriction were abolished and a free market in designing and making cards quickly appeared. The old licenses and monopolies where re-introduced during the Restoration of the monarchy after 1815. Thus, Say might well have seen the new flourishing card making industry in the 1790s and early 1800s.

Text

Adam Smith a très ingénieusement remarqué combien ce qu'il a le premier appelé la division du travail augmente sa puissance productive. Il croit que c'est à cette seule cause qu'il faut attribuer la supériorité des peuples civilisés sur les peuples sauvages. Nous avons vu que cette supériorité doit être évidemment attribuée à la faculté que possède l'homme de faire concourir, à la-confection des produits, et les capitaux et les agents naturels.

La séparation des occupations n'est qu'un moyen, une manière bien entendue et très favorable de se servir des agents de la production auxquels nous devons essentiellement tous les produits qui forment nos richesses; mais après l'avoir réduite à ce qu'elle est réellement, il nous sera utile d'apprécier la totalité de son influence ; or, je ne pourrai mieux faire pour cela que de suivre Adam Smith, qui l'a analysée avec une étonnante sagacité et l'a observée jusque dans ses dernières conséquences.

Sans revenir sur l'exemple qu'il a donné de la division du travail dans la fabrication des épingles, observons-la dans une fabrication moins importante peut-être, et où cependant elle semble poussée plus loin, dans la fabrication des cartes à jouer. Ce ne sont point les mêmes ouvriers qui préparent le papier dont on fait les cartes, ni les couleurs dont on les empreint ; et en ne faisant attention qu'au seul emploi de ces matières, nous trouverons qu'un jeu de cartes est le résultat de plusieurs opérations, dont chacune occupe une série distincte d'ouvriers ou d'ouvrières qui s'appliquent toujours à la même opération. Ce sont des personnes différentes, et toujours les mêmes, qui épluchent les bouchons et grosseurs qui se trouvent dans le papier et nuiraient à l'égalité d'épaisseur; les mêmes qui collent ensemble les trois feuilles de papier dont se compose le carton et qui le mettent en presse ; les mêmes qui colorent le côté destiné à former le dos des cartes ; les mêmes qui impriment en noir le dessin des figures; d'autres ouvriers impriment les couleurs des mêmes figures; d'autres font sécher au réchaud les cartons une fois qu'ils sont imprimés ; d'autres s'occupent à les lisser dessus et dessous. C'est une occupation particulière que de les couper d'égale dimension ; c'en est une autre de les assembler pour en former des jeux; une autre encore d'imprimer les enveloppes des jeux, et une autre encore de les envelopper; sans compter les fonctions des personnes chargées des ventes et des achats, de payer les ouvriers et de tenir les écritures. Enfin, à en croire les gens du métier, chaque carte, c'est-à-dire un petit morceau de carton de la grandeur de la main, avant d'être en état de vente, ne subit pas moins de 70 opérations différentes, qui toutes pourraient être l'objet du travail d'une espèce différente d'ouvriers. Et s'il n'y a pas 70 séries d'ouvriers dans chaque manufacture de cartes, c'est parce que la division du travail n'y est pas poussée aussi loin qu'elle pourrait l'être, et parce que le même ouvrier est chargé de deux, trois ou quatre opérations distinctes.

L'influence de ce partage des occupations est immense. J'ai vu une fabrique de cartes à jouer ou trente ouvriers produisaient journellement 15,500 cartes, c'est-à-dire au delà de 500 cartes par chaque ouvrier; et l'on peut présumer que, si chacun de ces ouvriers se trouvait obligé de faire à lui seul toutes les opérations, et en le supposant même exercé dans son art, il ne terminerait peut-être pas deux cartes dans un jour; et par conséquent les 30 ouvriers, au lieu de 15,500 cartes, n'en feraient que 60.

William J. Fox, "I, Foreigner" (1844)↩

Source

W.J. Fox, speech given at the Covent Garden Theatre on January 25, 1844, Collected Works, vol. IV: Anti-Corn Law Speeches, pp. 62-63.

Introduction

William Johnson Fox (1786-1864) was a Member of Parliament, a journalist and renowned orator, and one of the founders of the Westminster Review. He became one of the most popular speakers of the Anti-Corn Law League and delivered courses to the workers on Sunday evenings. He served in Parliament from 1847 to 1863. The friend and editor of Bastiat's Collected Works, Prosper Paillottet translated one of his works on religion into French. [7] .

Marvelling at the bounty of goods imported from all over the world was a common rhetorical device used by free traders at this time. It was made very popular by an orator of the Anti-Corn Law League, William J. Fox (1786-1864). Fox first gave a version of this speech at Rochdale on November 25, 1843 (Collected Works, vol. IV: Anti-Corn Law Speeches, pp. 42-43) and it proved so popular they he gave a slightly longer version of it at the Covent Garden Theatre on January 25, 1844, where it was picked up by the press and later translated into several European languages (Collected Works, vol. IV: Anti-Corn Law Speeches, pp. 62-63). He highlighted how the English, even the anti-free trade landowners, were already heavily dependent on goods made by foreigners, even before free trade had become government policy in 1846.

Text

... It is a favourite theme, this independence of foreigners. One would imagine that the patriotism of the landlord’s breast must be most intense. Yet he seems to forget that he is employing guano to manure his fields; that he is spreading a foreign surface over his English soil, through which every atom of corn is to grow; becoming thereby polluted with the dependence upon foreigners which he professes to abjure.

To what is he left, this disclaimer against foreigners and advocate of dependence upon home? Trace him through his career. This was very admirably done by an honourable gentleman, who just now addressed you, at the Salisbury contest. His opponent urged this plea, and Mr. Bouverie stripped him, as it were, from head to foot, that he had not an article of dress upon him which did not render him in some degree dependent upon foreigners. We will pursue this subject, and trace his whole life. What is the career of the man whose possessions are in broad acres? Why, a French cook dresses his dinner for him, and a Swiss valet dresses him for dinner; he hands down his lady, decked with pearls that never grew in the shell of a British oyster; and her waving plume of ostrich-feathers certainly never formed the tail of a barn-door fowl. The viands of his table are from all the countries of the world; his wines are from the banks of the Rhine and the Rhone. In his conservatory, he regales his sight with the blossoms of South-American flowers. In his smoking room, he gratifies his scent with the weed of North America. His favourite horse is of Arabian blood; his pet dog of the St. Bernard’s breed. His gallery is rich with pictures from the Flemish school, and his statues from Greece. For his amusements, he goes to hear Italian singers warble German music, followed by a French ballet. If he rises to judicial honours, the ermine which decorates his shoulders is a production that was never before on the back of a British beast. His very mind is not English in its attainments; it is a mere pic-nic of foreign contributions. His poems and philosophy are from Greece and Rome; his geometry is from Alexandria; his arithmetic is from Arabia; and his religion from Palestine. In his cradle, in his infancy, he rubbed his gums with coral from Oriental oceans; and when he dies, his monument will be sculptured in marble from the quarries of Carrara.

And yet this is the man who says: “Oh! let us be independent of foreigners! Let us submit to taxation; let there be privation and want; let there be struggles and disappointments; let there be starvation itself; only let us be independent of foreigners!” I quarrel not with him for enjoying the luxuries of other lands, the results of arts which make it life to live. I wish that not only he and his order may have all the good that any climate or region can bear for them - it is their right, if they have wherewithal to exchange for it; what I complain of is, the sophistry, the hypocrisy, and the iniquity of talking of independence of foreigners in the article of food, while there is dependence in all these materials of daily enjoyment and recreation. Food is the article the foreigner most wants to sell; food is that which thousands of our operatives most want to buy; and it is not for him - the mere creature of foreign agency from head to foot - to interpose and say: “You shall be independent; I alone will be the very essence and quintessence of dependence.” We compromise not this question with parties such as these; no, nor with the legislature.

Bastiat, "I, Carpenter" (1848) ↩

Source

T.176 (1848.01.15) "Natural and Artificial Organisation" (Organisation naturelle Organisation artificielle), Journal des Économistes, T. XIX, No. 74, Jan 1848, pp. 113-26; also EH1, 1st ed. Jan. 1850, pp. 25-51.

In the FEE translation they call him a "cabinet maker": Frédéric Bastiat, Economic Harmonies, trans by W. Hayden Boyers, ed. George B. de Huszar, introduction by Dean Russell (Irvington-on-Hudson: Foundation for Economic Education, 1996).

Text

Let us take a man who belongs to a modest class in society, a village carpenter, for example, and let us observe all the services he provides to society and all those he receives from it; it will not take us long to be struck by the enormous apparent disproportion.

This man spends his day sanding planks and making tables and wardrobes; he complains about his situation and yet what does he receive from this same society in return for his work?

First of all, each day when he gets up he dresses, and he has not personally made any of the many items of his outfit. However, for these garments, however simple, to be at his disposal, an enormous amount of work, industry, transport, and ingenious invention needs to have been accomplished. Americans need to have produced cotton, Indians indigo, Frenchmen wool and linen and Brazilians leather. All these materials need to have been transported to a variety of towns, worked, spun, woven, dyed, etc.

He then has breakfast. In order for the bread he eats to arrive each morning, land had to be cleared, fenced, ploughed, fertilized, and sown. Harvests had to be stored and protected from pillage. A degree of security had to reign in the context of an immense multitude of people. Wheat had to be harvested, ground, kneaded, and prepared. Iron, steel, wood, and stone had to be changed by human labor into tools. Some men had to make use of the strength of animals, others the weight of a waterfall, etc.; all things each of which, taken singly, implies an incalculable mass of labor put to work , not only in space but also in time.

This man will not spend his day without using a little sugar, a little oil, or a few utensils.

He will send his son to school to receive instruction, which although limited, nonetheless implies research, previous studies, and knowledge which would startle the imagination.

He goes out and finds a road that is paved and lit.

His ownership of a piece of property is contested; he will find lawyers to defend his rights, judges to maintain them, officers of the court to carry out the judgment, all of which once again imply acquired knowledge, and consequently understanding and a certain standard of living.

He goes to church; it is a prodigious monument and the book he carries is a monument to human intelligence perhaps more prodigious still. He is taught morality, his mind is enlightened, his soul elevated, and in order for all this to happen, another man had to be able to go to libraries and seminaries and draw on all the sources of human tradition; he had to have been able to live without taking direct care of his bodily needs.

If our craftsman sets out on a journey, he finds that, to save him time and increase his comfort, other men have flattened and leveled the ground, filled in the valleys, lowered the mountains, joined the banks of rivers, increased the smooth passage on the route, set wheeled vehicles on paving stones or iron rails, and mastered the use of horses, steam, etc.

It is impossible not to be struck by the truly immeasurable disproportion that exists between the satisfactions drawn by this man from society and those he would be able to provide for himself if he were to be limited to his own resources.I am bold enough to say that in a single day, he consumes things he would not be able to produce by himself in ten centuries.

What makes the phenomenon stranger still is that all other men are in the same situation as he. Each one of those who make up society has absorbed a million times more than he would have been able to produce; nevertheless they have not robbed each other of anything. And if we examine things more closely, we see that this carpenter has paid in services for all the services he has been rendered. If he kept his accounts with rigorous accuracy we would be convinced that he has received nothing that he has not paid for by means of his modest industry, and that whoever has been employed in his service either at any time or in a given period has received or will receive his remuneration.

For this reason, the social mechanism needs to be either very ingenious or very powerful since it leads to this strange result, that each man, even he whom fate has placed in the humblest of conditions, receives more satisfaction in a single day than he could produce in several centuries.

Bastiat, "I, Broken Window" (1850)↩

Source

Frédéric Bastiat, Ce qu’on voit et ce qu’on ne voit pas, ou l’Économie politique en une leçon. Par M. F. Bastiat. Représentant du Peuple à l’Assemblée Nationale, Membre correspondant de l’Institut (Paris: Guillaumin, 1850). [online]. Chapter I "La vitre casée", pp. 5-8.

Text

Have you ever witnessed the fury of the good bourgeois Jacques Bonhomme when his dreadful son succeeded in breaking a window? If you have witnessed this sight, you will certainly have noted that all the onlookers, even if they were thirty in number, appeared to have agreed mutually to offer the unfortunate owner this uniform piece of consolation: “Good comes out of everything. Accidents like this keep production moving. Everyone has to live. What would happen to glaziers if no window panes were ever broken?”

Well, there is an entire theory in this consoling formula, which it is good to surprise in flagrante delicto in this very simple example, since it is exactly the same as the one that unfortunately governs the majority of our economic institutions.

If you suppose that it is necessary to spend six francs to repair the damage, if you mean that the accident provides six francs to the glazing industry and stimulates the said industry to the tune of six francs, I agree and I do not query in any way that the reasoning is accurate. The glazier will come, do his job, be paid six francs, rub his hands and in his heart bless the dreadful child. This is what is seen.

But if, by way of deduction, as is often the case, the conclusion is reached that it is a good thing to break windows, that this causes money to circulate and therefore industry in general is stimulated, I am obliged to cry: “Stop!” Your theory has stopped at what is seen and takes no account of what is not seen.

What is not seen is that since our bourgeois has spent six francs on one thing, he can no longer spend them on another What is not seen is that if he had not had a window to replace, he might have replaced his down-at-heel shoes or added a book to his library. In short, he would have used his six francs for a purpose that he will no longer be able to.

Let us therefore draw up the accounts of industry in general.

As the window was broken, the glazing industry is stimulated to the tune of six francs; this is what is seen.

If the window had not been broken, the shoemaking industry (or any other) would have been stimulated to the tune of six francs; this is what is not seen.

And if we took into consideration what is not seen, because it is a negative fact, as well as what is seen, because it is a positive fact, we would understand that it makes no difference to national output and employment, taken as a whole, whether window panes are broken or not.

Let us now draw up Jacques Bonhomme’s account.

In the first case, that of the broken window, he spends six francs and enjoys the benefit of a window neither more nor less than he did before. In the second, in which the accident had not happened, he would have spent six francs on shoes and would have had the benefit of both a pair of shoes and a window.

Well, since Jacques Bonhomme is a member of society, it has to be concluded that, taken as a whole and comparing what he has to do with his benefits, society has lost the value of the broken window.

From which, as a generalization, we reach the unexpected conclusion: “Society loses the value of objects destroyed to no purpose”, and the aphorism that will raise the hackles of protectionists: “Breaking, shattering and dissipating does not stimulate the national employment”, or more succinctly: “Destruction is not profitable”.

What will Le Moniteur industriel say, and what will the opinion be of the followers of the worthy Mr. de Saint-Chamans, who has so accurately calculated what productive activity would gain from the burning of Paris because of the houses that would have to be rebuilt?

It grieves me to upset his ingenious calculations, especially since he has introduced their spirit into our legislation. But I beg him to redo them, introducing into the account what is not seen next to what is seen.

The reader must take care to note clearly that there are not just two characters, but three, in the little drama that I have put before him. One, Jacques Bonhomme, represents the Consumer, reduced by the breakage to enjoy one good instead of two. The second is the Glazier, who shows us the Producer whose activity is stimulated by the accident. The third is the Shoemaker (or any other producer) whose output is reduced to the same extent for the same reason. It is this third character that is always kept in the background and who, by personifying what is not seen, is an essential element of the problem. He is the one who makes us understand how absurd it is to see profit in destruction. He is the one who will be teaching us shortly that it is no less absurd to see profit in a policy of trade restriction, which is after all, nothing other than partial destruction. Therefore, go into the detail of all the arguments brought out to support it and you will merely find a paraphrase of that common saying: “What would happen to glaziers if window were never broken?”

Leonard Read, “I, Pencil” (1958)↩

Source

Leonard E. Read, I Pencil: My Family Tree as told to Leonard E. Reed (Irvington-on-Hudson, New York: Foundation for Economic Education, Inc., 1999).

Introduction

Leonard E. Read (1898–1983) founded FEE in 1946 and served as its president until his death. “I, Pencil,” his most famous essay, was first published in the December 1958 issue of The Freeman. Although a few of the manufacturing details and place names have changed over the past forty years, the principles are unchanged.

A charming story which explains how something as apparently simple as a pencil is in fact the product of a very complex economic process based upon the division of labor, international trade, and comparative advantage.

Text

I, Pencil My Family Tree as told to Leonard E. Read

I am a lead pencil—the ordinary wooden pencil familiar to all boys and girls and adults who can read and write.

Writing is both my vocation and my avocation; that's all I do.

You may wonder why I should write a genealogy. Well, to begin with, my story is interesting. And, next, I am a mystery—more so than a tree or a sunset or even a flash of lightning. But, sadly, I am taken for granted by those who use me, as if I were a mere incident and without background. This supercilious attitude relegates me to the level of the commonplace. This is a species of the grievous error in which mankind cannot too long persist without peril. For, the wise G. K. Chesterton observed, “We are perishing for want of wonder, not for want of wonders.”

I, Pencil, simple though I appear to be, merit your wonder and awe, a claim I shall attempt to prove. In fact, if you can understand me—no, that's too much to ask of anyone—if you can become aware of the miraculousness which I symbolize, you can help save the freedom mankind is so unhappily losing. I have a profound lesson to teach. And I can teach this lesson better than can an automobile or an airplane or a mechanical dishwasher because—well, because I am seemingly so simple.

Simple? Yet, not a single person on the face of this earth knows how to make me. This sounds fantastic, doesn't it? Especially when it is realized that there are about one and one-half billion of my kind produced in the U.S.A. each year.

Pick me up and look me over. What do you see? Not much meets the eye—there's some wood, lacquer, the printed labeling, graphite lead, a bit of metal, and an eraser.

Innumerable Antecedents

Just as you cannot trace your family tree back very far, so is it impossible for me to name and explain all my antecedents. But I would like to suggest enough of them to impress upon you the richness and complexity of my background.

My family tree begins with what in fact is a tree, a cedar of straight grain that grows in Northern California and Oregon. Now contemplate all the saws and trucks and rope and the countless other gear used in harvesting and carting the cedar logs to the railroad siding. Think of all the persons and the numberless skills that went into their fabrication: the mining of ore, the making of steel and its refinement into saws, axes, motors; the growing of hemp and bringing it through all the stages to heavy and strong rope; the logging camps with their beds and mess halls, the cookery and the raising of all the foods. Why, untold thousands of persons had a hand in every cup of coffee the loggers drink!

The logs are shipped to a mill in San Leandro, California. Can you imagine the individuals who make flat cars and rails and railroad engines and who construct and install the communication systems incidental thereto? These legions are among my antecedents.

Consider the millwork in San Leandro. The cedar logs are cut into small, pencil-length slats less than one-fourth of an inch in thickness. These are kiln dried and then tinted for the same reason women put rouge on their faces. People prefer that I look pretty, not a pallid white. The slats are waxed and kiln dried again. How many skills went into the making of the tint and the kilns, into supplying the heat, the light and power, the belts, motors, and all the other things a mill requires? Sweepers in the mill among my ancestors? Yes, and included are the men who poured the concrete for the dam of a Pacific Gas & Electric Company hydroplant which supplies the mill's power!

Don't overlook the ancestors present and distant who have a hand in transporting sixty carloads of slats across the nation.

Once in the pencil factory—$4,000,000 in machinery and building, all capital accumulated by thrifty and saving parents of mine—each slat is given eight grooves by a complex machine, after which another machine lays leads in every other slat, applies glue, and places another slat atop—a lead sandwich, so to speak. Seven brothers and I are mechanically carved from this “wood-clinched” sandwich.

My “lead” itself—it contains no lead at all—is complex. The graphite is mined in Ceylon. Consider these miners and those who make their many tools and the makers of the paper sacks in which the graphite is shipped and those who make the string that ties the sacks and those who put them aboard ships and those who make the ships. Even the lighthouse keepers along the way assisted in my birth—and the harbor pilots.

The graphite is mixed with clay from Mississippi in which ammonium hydroxide is used in the refining process. Then wetting agents are added such as sulfonated tallow—animal fats chemically reacted with sulfuric acid. After passing through numerous machines, the mixture finally appears as endless extrusions—as from a sausage grinder-cut to size, dried, and baked for several hours at 1,850 degrees Fahrenheit. To increase their strength and smoothness the leads are then treated with a hot mixture which includes candelilla wax from Mexico, paraffin wax, and hydrogenated natural fats.

My cedar receives six coats of lacquer. Do you know all the ingredients of lacquer? Who would think that the growers of castor beans and the refiners of castor oil are a part of it? They are. Why, even the processes by which the lacquer is made a beautiful yellow involve the skills of more persons than one can enumerate!

Observe the labeling. That's a film formed by applying heat to carbon black mixed with resins. How do you make resins and what, pray, is carbon black? My bit of metal—the ferrule—is brass. Think of all the persons who mine zinc and copper and those who have the skills to make shiny sheet brass from these products of nature. Those black rings on my ferrule are black nickel. What is black nickel and how is it applied? The complete story of why the center of my ferrule has no black nickel on it would take pages to explain.

Then there's my crowning glory, inelegantly referred to in the trade as “the plug,” the part man uses to erase the errors he makes with me. An ingredient called “factice” is what does the erasing. It is a rubber-like product made by reacting rape-seed oil from the Dutch East Indies with sulfur chloride. Rubber, contrary to the common notion, is only for binding purposes. Then, too, there are numerous vulcanizing and accelerating agents. The pumice comes from Italy; and the pigment which gives “the plug” its color is cadmium sulfide.

No One Knows

Does anyone wish to challenge my earlier assertion that no single person on the face of this earth knows how to make me?

Actually, millions of human beings have had a hand in my creation, no one of whom even knows more than a very few of the others. Now, you may say that I go too far in relating the picker of a coffee berry in far off Brazil and food growers elsewhere to my creation; that this is an extreme position. I shall stand by my claim. There isn't a single person in all these millions, including the president of the pencil company, who contributes more than a tiny, infinitesimal bit of know-how. From the standpoint of know-how the only difference between the miner of graphite in Ceylon and the logger in Oregon is in the type of know-how. Neither the miner nor the logger can be dispensed with, any more than can the chemist at the factory or the worker in the oil field—paraffin being a by-product of petroleum.

Here is an astounding fact: Neither the worker in the oil field nor the chemist nor the digger of graphite or clay nor any who mans or makes the ships or trains or trucks nor the one who runs the machine that does the knurling on my bit of metal nor the president of the company performs his singular task because he wants me. Each one wants me less, perhaps, than does a child in the first grade. Indeed, there are some among this vast multitude who never saw a pencil nor would they know how to use one. Their motivation is other than me. Perhaps it is something like this: Each of these millions sees that he can thus exchange his tiny know-how for the goods and services he needs or wants. I may or may not be among these items.

No Master Mind

There is a fact still more astounding: the absence of a master mind, of anyone dictating or forcibly directing these countless actions which bring me into being. No trace of such a person can be found. Instead, we find the Invisible Hand at work. This is the mystery to which I earlier referred. It has been said that “only God can make a tree.” Why do we agree with this? Isn't it because we realize that we ourselves could not make one? Indeed, can we even describe a tree? We cannot, except in superficial terms. We can say, for instance, that a certain molecular configuration manifests itself as a tree. But what mind is there among men that could even record, let alone direct, the constant changes in molecules that transpire in the life span of a tree? Such a feat is utterly unthinkable!

I, Pencil, am a complex combination of miracles: a tree, zinc, copper, graphite, and so on. But to these miracles which manifest themselves in Nature an even more extraordinary miracle has been added: the configuration of creative human energies—millions of tiny know-hows configurating naturally and spontaneously in response to human necessity and desire and in the absence of any human master-minding! Since only God can make a tree, I insist that only God could make me. Man can no more direct these millions of know-hows to bring me into being than he can put molecules together to create a tree.

The above is what I meant when writing, “If you can become aware of the miraculousness which I symbolize, you can help save the freedom mankind is so unhappily losing.” For, if one is aware that these know-hows will naturally, yes, automatically, arrange themselves into creative and productive patterns in response to human necessity and demand—that is, in the absence of governmental or any other coercive masterminding—then one will possess an absolutely essential ingredient for freedom: a faith in free people. Freedom is impossible without this faith.

Once government has had a monopoly of a creative activity such, for instance, as the delivery of the mails, most individuals will believe that the mails could not be efficiently delivered by men acting freely. And here is the reason: Each one acknowledges that he himself doesn't know how to do all the things incident to mail delivery. He also recognizes that no other individual could do it. These assumptions are correct. No individual possesses enough know-how to perform a nation's mail delivery any more than any individual possesses enough know-how to make a pencil. Now, in the absence of faith in free people—in the unawareness that millions of tiny know-hows would naturally and miraculously form and cooperate to satisfy this necessity—the individual cannot help but reach the erroneous conclusion that mail can be delivered only by governmental “master-minding.”

Testimony Galore

If I, Pencil, were the only item that could offer testimony on what men and women can accomplish when free to try, then those with little faith would have a fair case. However, there is testimony galore; it's all about us and on every hand. Mail delivery is exceedingly simple when compared, for instance, to the making of an automobile or a calculating machine or a grain combine or a milling machine or to tens of thousands of other things. Delivery? Why, in this area where men have been left free to try, they deliver the human voice around the world in less than one second; they deliver an event visually and in motion to any person's home when it is happening; they deliver 150 passengers from Seattle to Baltimore in less than four hours; they deliver gas from Texas to one's range or furnace in New York at unbelievably low rates and without subsidy; they deliver each four pounds of oil from the Persian Gulf to our Eastern Seaboard—halfway around the world—for less money than the government charges for delivering a one-ounce letter across the street!

The lesson I have to teach is this: Leave all creative energies uninhibited. Merely organize society to act in harmony with this lesson. Let society's legal apparatus remove all obstacles the best it can. Permit these creative know-hows freely to flow. Have faith that free men and women will respond to the Invisible Hand. This faith will be confirmed. I, Pencil, seemingly simple though I am, offer the miracle of my creation as testimony that this is a practical faith, as practical as the sun, the rain, a cedar tree, the good earth.

Endnotes↩

[1] Leonard E. Read, I Pencil: My Family Tree as told to Leonard E. Reed (Irvington-on-Hudson, New York: Foundation for Economic Education, Inc., 1999). [online elsewhere]. The 60th anniversary of "I, Pencil" was celebrated on the FEE website with a series of essays "10 Essays Celebrating 60 Years of “I, Pencil” [online elsewhere]

[2] Milton Friedman and Rose D. Friedman, Free to Choose: A Personal Statement (New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1980).

[3] Friedrich Hayek, "The Use of Knowledge in Society" American Economic Review (1945) XXXV, No. 4. pp. 519-30 . [online at Econlib].

[4] The lllustrated version of Bastiat's The Law: Samplings of Important Books No. 4: The Law by Frederic Bastiat (The Foundation for Economic Education, Incorporated, Irvington-on-Hudson, N.Y., n.d., circa late 1940s). Sampling and drawings by Constance Harris. [online at FEE]. The illustrations [online here].

[5] See my paper on how economists have attempted to popularize economic ideas in "Broken Windows and House owning Dogs: The French Connection and the Popularization of Economics from Bastiat to Jasay," The Independent Review: A Journal of Political Economy. Symposium on Anthony de Jasay (Summer 2015), vol. 20, no. 1, pp. 61-84. [online elsewhere]. This is a shorter version of a longer paper which went from "Say to Jasay": "Negative Railways, Turtle Soup, talking Pencils, and House owning Dogs: ‘The French Connection’ and the Popularization of Economics from Say to Jasay" (2014, 2024). This paper was originally written for a Symposium on Tony de Jasay following his death in 2014. [online here].

[6] See also my illustrated essay "The Division of Labour: Adam Smith and the Pin-Maker; J.B. Say and the Playing Card Manufacturer". [to come].

[7] Des Idées religieuses, par William Johnson Fox, 15 conférences. Traduit par P. Paillottet (Paris: G. Baillière, 1877).