James Mill, The Political Writings of James Mill: Essays and Reviews on Politics and Society, 1815-1836

Edited by David M. Hart

Date: 15 October, 2020

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- The Political Writings of James Mill (1815-1836)

- [1.1] "Dugald Stewart's “Elements of the Philosophy of Mind”," The British Review, Aug. 1815.

- [2.1] "Banks for Saving", Encyclopaedia Britannica, 1824.

- [2.2] "Beggar", Encyclopaedia Britannica, 1824.

- [2.3] "Benefit Societies", Encyclopaedia Britannica, 1824.

- [2.4] "Caste", Encyclopaedia Britannica, 1824.

- [2.5] "Colony", Encyclopaedia Britannica, 1824.

- [2.6] "Economists", Encyclopaedia Britannica, 1824.

- [2.7] "Education", Encyclopaedia Britannica, 1824.

- [2.8] "Government", Encyclopaedia Britannica, 1824.

- [2.9] "Jurisprudence", Encyclopaedia Britannica, 1824.

- [2.10] "Liberty of the Press", Encyclopaedia Britannica, 1824.

- [2.11] "Nations, Law of", Encyclopaedia Britannica, 1824.

- [2.12] "Prisons and Prison Discipline", Encyclopaedia Britannica, 1824.

- [3.1] "Summary Review of the Conduct and Measures of the Seventh Imperial Parliament," Parliamentary History and Review, 1826.

- [4.1] "Periodical Literature 1 (Edinburgh Review and Quarterly Review)," The Westminster Review, Jan. 1824.

- [4.2] "Periodical Literature 2 (Quarterly Review and Edinburgh Review)," The Westminster Review, Oct. 1824.

- [4.3] "Robert Southey's Book of the Church," The Westminster Review, Jan. 1825.

- [4.4] "Ecclesiastical Establishments," The Westminster Review, Apr. 1826.

- [4.5] "Formation of Opinions," The Westminster Review, July 1826.

- [4.6] "State of the Nation," The Westminster Review, Oct. 1826.

- [4.7] "The Ballot," The Westminster Review, July 1830.

- [5.1] "State of the Nation," The London Review, Apr. 1835.

- [5.2] "The Ballot—A Dialogue," The London Review, Apr. 1835.

- [5.3] "The Church and its Reform," The London Review, Jul. 1835.

- [5.4] "Law Reform," The London Review, Oct. 1835.

- [5.5] "Aristocracy," The London Review, Jan. 1836.

- [5.6] "Whether Political Economy is Useful?," The London Review, Jan. 1836.

- [5.7] "Theory and Practice," The London and Westminster Review, Apr. 1836.

Introduction↩

Why this Anthology?

This is an anthology of James Mill’s writings compiled from The British Review, and London Critical Journal [1815], the Supplement to the 4th, 5th and 6th editions of the Encyclopaedia Britannica [1815-1824], Parliamentary History and Review [1826], The Westminster Review [1824-1836], The London Review [1835-36], and The London and Westminster Review [1836].

The writings on politics and society by James Mill (1773-1836) have been somewhat neglected by historians and political theorists. A collection of his writings on "economics" was published by Donald Winch in 1966 and it included a couple of articles and extracts from his books:

- An Essay of the Impolicy of a Bounty On the Exportation of Grain

- Commerce Defended

- "Smith On Money and Exchange" (Ed. Rev. 1808)

- Elements of Political Economy,

- "Whether Political Economy Is Useful" (London Review, 1836)

- History of India

Another anthology was published in 1992 by Cambridge University Press in their "Cambridge Texts in the History of Political Thought" series. This is a remarkably dull selection as it leaves out much of Mill's writing on social theory, the class structure of British society, religious institutions, free trade,the strategy for achieving social and political change, charities and self-help, and the nature of public opinion. The selection is mainly his articles from the Encyclopaedia Britannica which were republished separately during the 1820s and ignores his long-forgotten articles on class and self help organizations for the poor. The full list is as follows:

- Encyclopaedia Britannica:

- Government

- Jurisprudence

- Liberty of the press

- Edcuation

- Prisons and Prison Discipline

- The Ballot

- Appendix: Macaulay vs. Mill

- T.B. Macaulay, Mill on Government

- James Mill [Reply to Macaulay] From a Fragment on Mackintosh (1835).

Since James Mill was a "political economist" the distinction between his writings on "politics" and "economics" is a mute one in any case as Winch implies by including in his anthology of economic writings material on the Hindus in India. This anthology of his writings on "politics" and "society" tries to fill the gap by focusing less on his technical work on economic theory and policy and more on his essays and reviews written over a 20 year period on various aspects of British politics and society. There is a special emphasis on his social theory of class and exploitation which seemed to become more important to him during the struggle to reform the British system of government in the years leading up to the First Reform Act of 1832.

This anthology focuses on the period between the end of the war against Napoleon and Mill's death at the age of 63 on 23 June, 1836. His writings can usefully be divided into two periods. The first covers the period between 1802 and 1815/1817 when he wrote for the following publications [see the main bibliography for an incomplete list of the pieces he wrote]:

- Anti-Jacobin Review and Magazine [1802]

- The Literary Journal or Universal Review of Literature Domestic and Foreign [1803-1806]

- The Eclectic Review [1807-14]

- Annual Review and History of Literature for 1808 [1809]

- The Edinburgh Review [1807-1814]

- The Monthly Review [1810-1815]

- The Philanthropist [1811-1817]

The second period, the topic of this anthology, covers his more mature writings for the following publications:

- The British Review, and London Critical Journal [1815]

- Supplement to the 4th, 5th and 6th editions of the Encyclopaedia Britannica [1815-1824]

- Parliamentary History and Review [1826]

- The Westminster Review [1824-1836]

- The London Review [1835-36]

- The London and Westminster Review [1836]

See a brief bio and a bibliography of his works here.

Publishing and Biographical Information

We have used the following works to identify what articles were written by James Mill:

- Alexander Bain, James Mill. A Biography (London: Longmans, Green, and Co., 1882).

- James Mill, Selected Economic Writings, ed. Donald Winch (Edinburgh: Oliver Boyd for the Scottish Economic Society, 1966).

James Mill’s periodical writings can usefully be divided into two periods. The first covers the period between 1802 and 1815-1817 when he wrote for the following publications:

- Anti-Jacobin Review and Magazine (1802)

- The Literary Journal or Universal Review of Literature Domestic and Foreign (1803-1806)

- The Eclectic Review (1807-14)

- Annual Review and History of Literature for 1808 (1809)

- The Edinburgh Review (1807-1814)

- The Monthly Review (1810-1815)

- The Philanthropist (1811-1817)

The second period, from which we have taken the material for this anthology, covers his more mature writings in the period between the end of the war against Napoleon and Mill’s death at the age of 63 on 23 June, 1836 which he wrote for the following publications:

- The British Review, and London Critical Journal (1815)

- Supplement to the 4th, 5th and 6th editions of the Encyclopaedia Britannica (1815-1824)

- Parliamentary History and Review (1826)

- The Westminster Review (1824-1836)

- The London Review (1835-36)

- The London and Westminster Review (1836)

The essays are presented in chronological order of date of publication and consist of the following. They are also available in facsimile PDF by sections and all together in one file:

1. The British Review [1815] [PDF]

- 1.1 "Dugald Stewart's “Elements of the Philosophy of Mind”," Aug. 1815, vol. VI. pp. 170–200, in The British Review, and London Critical Journal. Vol. VI. (London: Baldwin, Cradock, and Joy, 1815).

2. Supplement to the 4th, 5th and 6th editions of the Encyclopaedia Britannica, Edinburgh, 1824, 6 volumes. [1815-1824] [PDF]

Supplement to the Fourth, Fifth, and Sixth Editions of the Encyclopaedia Britannica. With Preliminary Dissertations on the History of the Science. Illustrated by Engravings. (Edinburgh, Archibald Constable and Company, 1824). The following articles were written by Mill (which were signed “F.F.”):

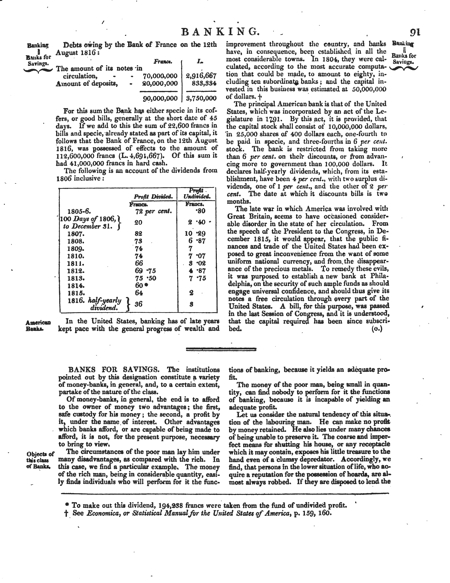

- 2.1 "Banks for Saving," vol. 2, pp. 91-101.

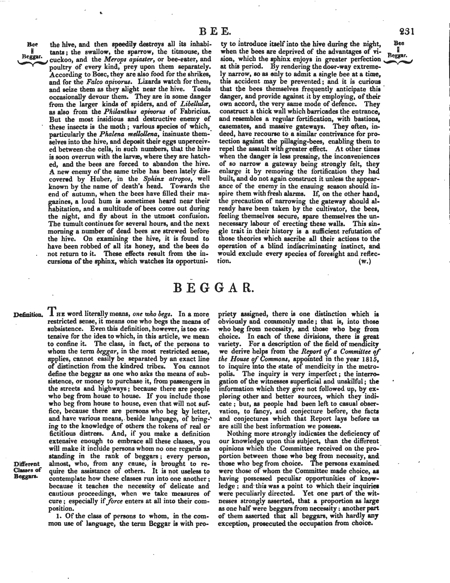

- 2.2 "Beggar," vol. 2, pp. 231-48.

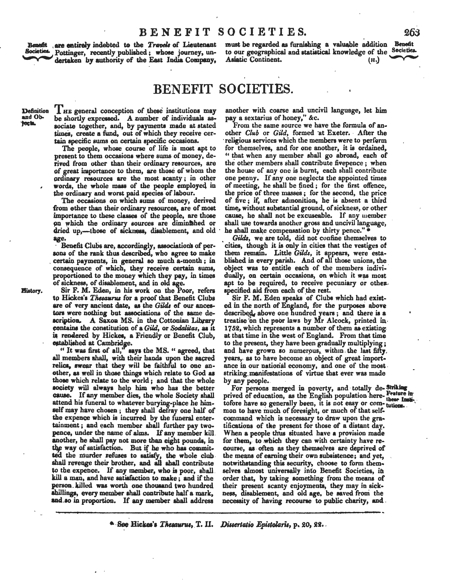

- 2.3 "Benefit Societies," vol. 2, pp. 263-69.

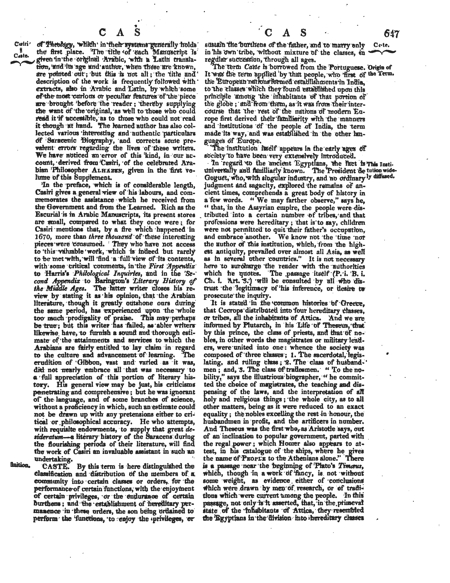

- 2.4 "Caste," vol. 2, pp. 674-54.

- 2.5 "Colony," vol. 3, pp. 257-73.

- 2.6 "Economists," vol. 3, pp. 708-24.

- 2.7 "Education," vol. 4, pp. 11-33.

- 2.8 "Government," vol. 4, pp. 491-505.

- 2.9 "Jurisprudence," vol. 5, pp. 143-161.

- 2.10 "Liberty of the Press," vol. 5, pp. 258-72.

- 2.11 "Nations, Law of," vol. 6, pp. 6-23.

- 2.12 "Prisons and Prison Discipline," vol. 6, pp. 385-95.

3. Parliamentary History and Review [London, 1826] [PDF]

- 3.1 "Summary Review of the Conduct and Measures of the Seventh Imperial Parliament" pp. 772-802, in Parliamentary History and Review; containing Reports of the Proceedings of the Two Houses of Parliament during the Session of 1826: - 7 Geo. IV. With Critical Remarks on the Principal Measures of the Session. (London: Longman, Rees, Orme, Brown, and Green, 1826).

4. The Westminster Review [1824-1836] [PDF]

The Westminster Review. (London: Baldwin, Cradock, and Joy, 1824-1836).

- 4.1 "Periodical Literature 1 (Edinburgh Review and Quarterly Review)," Jan. 1824, vol. I, no. I, pp. 206–68.

- 4.2 "Periodical Literature 2 (Quarterly Review and Edinburgh Review)," Oct. 1824, vol. II,no. IV, pp. 463–553.

- 4.3 "Robert Southey's Book of the Church," Jan. 1825, vol. III, no. V, pp. 167–213.

- 4.4 "Ecclesiastical Establishments," Apr. 1826, vol. V, no. X, pp. 504–48.

- 4.5 "Formation of Opinions," Jul. 1826, vol. VI, no. XI, pp. 1–23.

- 4.6 "State of the Nation," Oct. 1826, vol. VI, no. XII, pp. 249–78.

- 4.7 "The Ballot," Jul. 1830, vol. XIII, no. XXV, pp. 1–37.

5. The London Review [1835-36] [PDF]

The London Review (London: Simpkin, Marshall, & Company, 1835). 2 vols. James Mill signed the articles "P.Q."

Volume 1: April-July 1835

- 5.1 "State of the Nation," Apr. 1835, vol. I, no. 1, pp. 1–24

- 5.2 "The Ballot—A Dialogue," Apr. 1835, vol. I, no. 1, pp. 201–53

- 5.3 "The Church and its Reform," Jul. 1835, vol. I, no. 2, pp. 257–95

Volume 2: July-January, 1835-6

- 5.4 "Law Reform," Oct. 1835, vol. II, no. 3, pp. 1–51

- 5.5 "Aristocracy," Jan. 1836, vol. II, no. 4, pp. 283–306.

- 5.6 "Whether Political Economy is Useful?," Jan. 1836, vol. II, no. 4, pp. 553–72.

5.7 "Theory and Practice (signed with his usual "P.Q.") appeared in the first issue of the merged journal The London and Westminster Review in the issue of Apr. 1836, vol. XXV, pp. 223–34. James Mill died on 23 June, 1836. That year The London Review merged with its rival The Westminster Review to become the The London and Westminster Review. His last essay "Theory and Practice (signed with his usual "P.Q.") appeared in the first issue of the merged journal in the issue of Apr. 1836, vol. XXV, pp. 223–34.

James Mill and the Philosophic Radicals

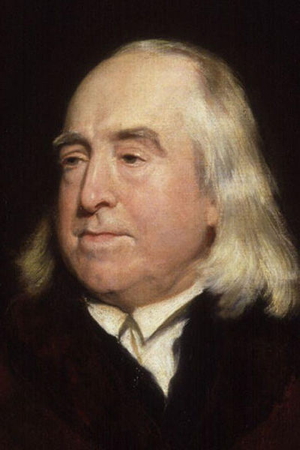

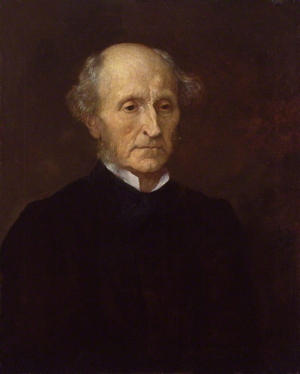

James Mill (1773-1836) was an early 19th century Philosophic Radical, journalist,

and editor from Scotland. He was very influenced by Jeremy Bentham’s ideas

about utilitarianism which he applied to the study of British India, political

economy, and electoral reform. Mill wrote on the British corn laws, free trade,

comparative advantage, the history of India, and electoral reform. His son,

John Stuart, after a rigorous home education, became one of the leading English

classical liberals in the 19th century.

The Philosophic Radicals

The Philosophic Radicals were a group of British reformers in the early and mid-19th century who were inspired by the ideas of Jeremy Bentham. Their group included James Mill, Francis Place, George Grote, John Stuart Mill, and William Molesworth. Some of them entered Parliament to lobby for legislative reforms. Their main journal was The Westminster Review.

Jeremy Bentham (1748-1832) trained as a lawyer and founded the early 19th century school of political thought known as “Benthamism” later called utilitarianism - based on the idea that governments should act so as to promote “the greatest good of the greatest number” of people. He spent much of his life attempting to drawn up an ideal Constitutional Code, but he was also active in parliamentary reform, education, and prison reform. He influenced the thinking of James Mill and his son John Stuart Mill.

John Stuart Mill (1806-1873) was the precocious child of the Philosophic Radical and Benthamite James Mill. Taught Greek, Latin, and political economy at an early age, He spent his youth in the company of the Philosophic Radicals, Benthamites and utilitarians who gathered around his father James. J.S. Mill went on to become a journalist, Member of Parliament, and philosopher and is regarded as one of the most significant English classical liberals of the 19th century.

The Political Writings of James Mill (1815-1836)

1. [1.1] "Dugald Stewart's “Elements of the Philosophy of Mind”," The British Review, Aug. 1815.↩

Bibliographical Information

"Dugald Stewart's “Elements of the Philosophy of Mind”," Aug. 1815, vol. VI. pp. 170–200, in The British Review, and London Critical Journal. Vol. VI. (London: Baldwin, Cradock, and Joy, 1815).

Text of Pamphlet

Art. IX.—: Elements of the Philosophy of the Human Mind.

By Dugald Stewart, Esq. F. R. S. Edinburgh; Honorary Member of the Imperial Academy of Sciences at St. Petersburgh; Member of the Royal Academy of Berlin, and of the American Philosophical Society, held at Philadelphia; formerly Professor of Moral Philosophy in the University of Edinburgh. Volume second, 4to. pp. 568. Edinburgh 1814. Constable and Co.; Cadell and Davies, London.

In giving an account of this volume, a task is imposed upon the critic of no ordinary magnitude, and to which the limits of a Review are very imperfectly adapted. It forms the second part of a great work, intended to exhibit a complete view of the intellectual operations of the human mind. Mr. Stewart is well known to be a faithful and distinguished disciple of that philosophy to which in this country, where philosophical pursuits have never excited much enthusiasm, the distinction has been almost exclusively confined, of rising to the reputation of a system, and being regarded as the foundation of a particular school. It is not alone to the volume before us that our attention must, therefore, be directed. This volume is but a continuation of the speculations commenced in the work which preceded it; and both are but emanations of that system of doctrines, and that plan of inquiry, which were recommended by Doctor Reid, and which have enjoyed a fortune almost new in this island.

The earliest of the works of Dr. Reid, his “Inquiry into the Human Mind, on the Principles of Common Sense,” appeared, at rather a remarkable era in the history of British philosophy. Two illustrious followers, Bishop Berkeley and Mr. Hume, had succeeded Mr. Locke. Reflecting upon the sensations or feelings, communicated by the organs of sense, Bishop Berkeley was led to put to himself the question, What is their cause? The usual answer to this question is obvious; that matter and its qualities are their cause. Colour is the cause of the feeling in [171] the mind called sight, hardness is the cause of a particular modification of the feeling in the mind called touch. To the penetrating and inquisitive mind of Berkeley, this answer did not prove quite satisfactory. The feeling in the mind was totally unlike any quality in matter. What reason was there for the belief that the one depended upon the other? Upon inquiry, it appeared that the only reason was, the existence of the mental feelings. The feelings are produced in the mind, therefore they are produced by something: they are produced in a certain order, therefore they are produced by the qualities of matter.

Led to penetrate further and further into this mystery, the question was at last suggested to the Bishop, what evidence he had for the existence of those qualities of matter, to which he was taught to look as the cause of his sensations. It immediately appeared, that for the existence of the qualities of matter the had no evidence whatsoever, but the existence of these sensations themselves. With this discovery, and the conclusions which flowed from it, he was deeply impressed. With regard to these sensations, all that man really knows, is, that they come into his mind, according to a certain order, which he learns by experience. That order has two forms. The sensations come into his mind, either one after another; or several of them come into it all at once. Those which come into the mind successively have given rise to no particular mystery. The case is different with those of which the entrance into the mind is synchronous. Suppose that the mind has the feeling, which has the name sight of a yellow colour; the colour of a golden ball, for example. If a man had no other sense but that of sight, he would have no other feeling associated with this sight of yellow. He moves and applies his hand in a particular manner; that is to say, certain feelings, one after another, take place in his mind, the last of which is, that he has the ball in his hand. At the same time that the sensation called sight of a yellow colour is in the mind, the sensations called a feeling of hardness, of roundness, and of weight, are now in the mind, along with a sensation of sameness in place with respect to them all. Now this cluster of sensations is all that is in the mind of a man, when he is said to perceive a ball of gold; and the conception of these sensations is all that is in his mind when he is said to think of the ball of gold. But what, then? is nothing ever in the mind but its own feelings? * No, certainly; nothing whatsoever. But what evidence do the feelings of the mind afford of matter or its properties? [172] Bishop Berkeley answered the question without hesitation. They afford no evidence at all. Nothing can be like a feeling in the mind, but a correspondent feeling of the same or another mind. When we suppose external objects, we do nothing but suppose certain unknown causes of our sensations; of which we can conceive nothing but that they are an unknown something, to which our sensations are owing. This supposition Bishop Berkeley declared to be an arbitrary hypothesis, unsupported by even the shadow of a reason. He also affirmed it to be absolutely insignificant, answering no one good purpose, either of utility, or of curiosity. Nay he proceeded still further, and produced a variety of curious reasons, to prove that the supposition really involves absurdity and contradiction, and cannot be held by any man who will obey the dictates of his reason.

If feelings afford no inference to the existence of any material cause of them, another question arises, what inference do they afford to that of a mind in which they may inhere? Berkeley scruples not to start the difficulty; and appears to allow, that, if in this case there was nothing more than in that of the cause of our sensations, we should never be entitled to draw a conclusion from the existence of our feelings to the existence of any thing beyond themselves; nor could regard the mind as any thing else than a system of floating ideas, connected together in a certain order, but without any ascertainable subject in which they inhere. He asserted, however, that the existence of the mind was proved by a different process; and by a palpable inaccuracy remarkable in so acute a metaphysician, declared that he was conscious of his mind, and of its personal identity.

Of this position it was easy for Mr. Hume to show the absurdity. We are conscious of the feelings of perceiving, of remembering, of willing, of approving and disapproving, loving, hating, and such like; but we are not conscious of any thing else; we are not conscious of any substance in which these feelings inhere. If not, and if we have no knowledge of mind beyond these modifications of consciousness, by what inference do we affirm, that mind is any thing beside themselves? As the external world is an arbitrary hypothesis, assumed to aid in accounting for the existence of our sensations, the mind, in the same manner, is an arbitrary hypothesis, an unknown something, assumed to aid in accounting for all the modifications of consciousness. But it is an hypothesis which really explains nothing; for we as little understand how feelings should exist in an unknown something, as how they should exist by themselves.

Such was the state of philosophical inquiry in this country, when Reid appeared. He declares that he was satisfied at first with the reasonings of Berkeley; and might fairly be ranked [173] among the believers in the non-existence of matter. But when Mr. Hume arrived, and demonstrated to him that upon the same principles mind was not more entitled to belief than matter, he confesses that he was startled. It appears, that he was alarmed for the evidence of religion, which seemed to him to vanish, if these conclusions were just. If no evidence remained for the existence either of mind, or of matter, no evidence appeared to remain for the existence of a God; and if that article of belief was lost, along with it, of course, disappeared all that system of anticipations respecting a future life, which rested upon it as their foundation. With this loss of the prospect of a future life, Dr. Reid, who was a pious man, appears to have been much more deeply affected, then with any revolution in his ideas respecting the present life, to which the progress of his reasonings had conducted him; and he tells us that he immediately began to exert himself to discover, if possible, a flaw in the chain of reasoning which produced so unhappy a result.

He soon convinced himself that he had made the discovery of which he was in quest. It was a doctrine of the ancient philosophers that the mind perceived not external objects immediately, but by means of certain representations, or images of them, called ideas, which they sent off, and which entered the mind by the inlets of the senses. The language of this theory had become the language in which all discourse relating to the mind was carried on. Upon it the language of Mr. Locke’s Essay was in a great measure founded: and that of Dr. Berkeley and Mr. Hume followed the universal example.

According to the theory, said Dr. Reid, that the mind perceives the qualities of matter, not immediately, but by means of certain floating images, it has no evidence of matter, which it never perceives. But what if this theory be without foundation? Then it will follow that the mind perceives matter immediately, and the evidence for its existence returns. The theory was so perfectly gratuitous, that the moment it occurred to any one to inquire for its evidence, it was overthrown. Dr. Reid refuted it with scorn; and declared, that as the arguments for the non-existence of matter rested upon this foundation, they fell with it, of course, to the ground.

When Dr. Reid, however, made the declaration, that the arguments for the non-existence of matter were altogether founded upon the theory of ideas, he advanced a great deal too far. Of this he himself was aware. He perceived that immediately we really are acquainted with nothing but our own feelings. It is from these feelings that every thing else, both matter and mind, is to be inferred. But from them how is any thing to be inferred? Not by experience, because we have experience of [174] nothing but the feelings themselves; not by reasoning, because there is no medium of proof which unites the premises with the conclusion. He says expressly, “our sensations have no resemblance to external objects, nor can we discover by our reason any necessary connexion between the existence of the former, and that of the latter.” In another passage he declares, “No man can show by any good argument, that all our sensations might not have been as they are, though no body, or quality of body, had ever existed.”

To lay a foundation then for a belief in the existence of matter and mind, Dr. Reid was under the necessity of looking out for another resource. It was the doctrine of all philosophy, that some things were not to be proved. In all reasoning we at last arrive at first principles, which are assumed. To this quarter Dr. Reid betook himself for the means of establishing a belief in the existence of mind and matter. These points, he said, were not to be proved, they were to be taken for granted.

In the next place, therefore, it was incumbent upon him to show, that such a mode of determining this most important controversy was by no means unreasonable. He attempted to show, that there was a variety of cases in which belief, the most absolute, took place in the human mind, without a possibility of assigning any reason for such belief; or of giving any other account of it, than that such is the constitution of our nature.

With respect to the marks by which a belief of this sort may be known and distinguished, the most remarkable of them is the common assent of mankind. A belief which, in this manner, is common to mankind, but which can be traced to no acknowledged principle of thought, he regarded as instinctive; and he gave to it the name of common sense.

The desire to augment and strengthen his proofs naturally drew Dr. Reid into a multiplication of the instances of instinctive belief; as well as into an exaggeration of the importance of the mark by which they were made known and recommended. He seemed to be eager to collect as many propositions as possible; of which he could at one and at the same time affirm, both that they were fit to be believed, and that no reason could be given why they should be believed. He lavished also his praises upon common sense, which he endeavoured to represent as a guide far superior to philosophy, and of which the decisions, when any diversity occurred, were always to be implicitly followed. He even availed himself of an ambiguity, which he himself had created in the meaning of the term, to cast ridicule very plentifully upon every man who did not agree with him. According to the usual meaning of the word common sense, it denotes a belief founded upon some very obvious and incontrovertible [175] reasons which it requires folly either to overlook, or to question. Dr. Reid applied it to a new case, which he himself was the first to point out, the case of belief not founded upon reasons at all. Did any man call in question any proposition which he was pleased to represent as not an object of reasoning, but of instinctive belief, Dr. Reid was very apt to laugh at him, as ranking with those contemptible men who are not under the guidance of common sense; that is, men whose belief is not governed by those obvious and incontrovertible reasons, which it is folly either to overlook or controvert. This, however, was not the case. The dissent was not from any proposition supported by obvious and incontrovertible reasons, but from a poposition which according to Dr. Reid ought to be believed without any reason at all.

This doctrine had not been long before the world, when it met with a very unreserved and forward controversialist, in Dr. Priestley. Any blemish which might lie upon its surface was not very likely to escape the keen though busy eye of this critic; but he was neither sufficiently acquainted with the science, nor sufficiently capable of patient, close, and subtle thinking, to go to the bottom of the principles which he attacked; nor could he avoid such displays of ignorance and self-delusion, as afforded a colour to Dr. Reid and his followers for treating the book with contempt, and holding themselves exempt from the obligation of answering its objections.

This was a misfortune to the science. Had the philosophy of Reid been controverted at an early period, with such a degree of knowledge and skill as would have commanded the respect and attention of the public, he would have been compelled to reconsider the foundation of his belief; and, either by obviating ill founded opinions, or by abandoning untenable ground, would have left the science in a better state, and more likely to invite a succession of cultivators.

It is a remarkable proof of the little taste there still is for profound and accurate thinking in England; in other words, a remarkable proof of the coarse and vulgar footing on which the business of education in this country remains—that, from the date of Dr. Priestley’s volume in 1774, to the present day, not a single work, the object of which is to controvert the philosophy of Reid, has been presented to the public. That such has been the case is not owing to the general acceptance with which, in the southern part of the island, his doctrines have been favoured; for they are spoken of with disapprobation by all but a few. Nor yet is it owing to their want of celebrity; for scarcely any doctrines, fabricated in this country, and related to the class to which they belong, can equal them in brilliancy of reputation. [176] No! the effect is solely to be ascribed to the indifference of the people to what may be either thought or said upon a subject of so much importance.

Dr. Reid’s list of what he calls “simple, original, and therefore inexplicable” cases of belief; in other words, belief altogether independent both of reason and of experience, first engages the castigating hand of Dr. Priestley. He exhibits them in a table, which certainly swells to a formidable size; but from which a considerable deduction might be made, by throwing out cases which he has inserted as distinct, though included under other titles. Among the things which we believe by an instinctive impulse, independently both of reason and experience, one is, that every sensation of which we are conscious is caused by a material object; another is, that every thing of which we are conscious, call it feeling, call it act, or call it idea, inheres in a mind; another is, that each of us is the same person that he was yesterday, or any other day since his birth; a fourth is, that similar effects will always flow from similar causes; a fifth is, that every body will speak truth; to which another instinctive propensity is added by Dr. Reid, and that is, a propensity to speak the truth.

Upon this mode of philosophising, the following strictures were easily made. If every speculator may lay down propositions at his pleasure, which have no dependence either upon reason or experience, but which he says our nature instinctively compells us to believe, there is an end to all reasoning and of all philosophy. I lay down, says Dr. Reid, such and such a proposition. I ask your reason for it, says Dr. Priestley. Reason, says Dr. Reid, is not applicable to this proposition; it is believed by instinct. Who says so, cries Dr. Priestley? I say so, replies Dr. Reid. This much being said, it is evident the dispute is at an end. Dr. Reid assumes that the proposition is to be believed merely because he calls it an original principle, that is became he says it is to believed. The ipse dixit of Dr. Reid is the standard of reason and philosophy. He solves every thing by the infallible method of declaring that it is just as he pleases, and because he so pleases; and in the true stile of Lord Peter, he finishes, by calling every body fool and rogue that dissents from him.

No, says Dr. Reid, it is not upon the ground of my ipse dixit alone that I say you ought to believe; but upon the ground of my ipse dixit, along with the general opinion of mankind. But Dr. Priestly found no difficulty in replying, that if the ipse dixit of Dr. Reid be a very insufficient ground for the establishment of any fundamental article of belief, the ordinary opinion of mankind is, if possible, still less a criterion of truth. Surely [177] if we have no reason for believing in the existence either of matter or of mind, but the vulgar impression of the mass of mankind, joined to the ipse dixit of Dr. Reid, it is a belief which no rational mind will entertain with great confidence. The mass of mankind believe with perfect assurance, that what is in the mind when they see a ball of gold is a perfect image of the ball itself. Dr. Reid will tell them it is only a feeling; which has no more resemblance to a ball of gold, than the pain of the colic to the sound of a trumpet. The mass of mankind believe that extension is essentially coloured; and no man will pretend that he can think of extension without colour, yet Dr. Reid will allow that no necessary connexion exists between them. Of such illusions, to which mankind are subject, and which universally prevail till philosophy slowly disentangles one groundless association after another, it were superfluous to multiply instances. In the same manner the supposition of some external cause resembling the feelings communicated by our senses, and the supposition of some feeling substance to which all our feelings belong, is so naturally suggested by those feelings, that if we could be ever so completely assured that those feelings offered no ground of inference either to matter as a cause, or to mind as a subject, we can conceive how it might have been even traced a priori that man would form the very conclusions respecting those points which hitherto have exhibited a prevalence so nearly universal.

Had Dr. Priestley confined himself to the task of enforcing these strictures, and of fixing the attention of mankind upon the conclusion to which they lead; that the philosophy of Dr. Reid completely fails in providing that antidote which it pretends to provide, to the scepticism of Bishop Berkeley and Mr. Hume; he would have performed an essential service to the progress of this species of philosophy, because he would have stimulated Dr. Reid himself, as well as others, to a more vigorous prosecution of the inquiry; and so important a branch of science would not have been left in the disgraceful condition in which it has so long been treated, presenting conclusions of the utmost moment which nobody is willing to believe, supported by a chain of reasoning which we feel to be wrong, but which nobody has answered.

But Dr. Priestley was ambitious of providing the antidote himself, and by the impotence of his attempt discredited the criticism by which he had disclosed the failure of his predecessor. As, for instance, so ignorant was he of the reasonings of Berkeley and Hume; reasonings which Dr. Reid declares to be demonstrative, and in which, after repeated examinations he had not discovered a flaw, as to give it as his opinion, that even according to the theory of ideas, the existence of matter may be [178] inferred. “Mr. Locke, and other advocates for ideas, supposed that they were the immediate objects of our thoughts, the things of which we are properly speaking conscious, or that we know in the first instance. From them, however, we think we can infer the real existence of other things, from which those ideas are derived.”*

If the soul be immaterial, Dr. Priestley affirms, we have in that case the strongest reason to conclude that a material world has no existence. Dr. Reid had said, “I take it for granted upon the testimony of common sense, that my mind is a substance, that is, a permanent subject of thought, and my reason convinces me, that it is an unextended and invisible substance: and hence I infer that there cannot be in it any thing that resembles extension.” Upon this Dr. Priestley affirms, “he might with equal appearance of truth infer, that the mind cannot be affected by any thing that has extension; for how can any thing act upon another but by means of some common property? Though, therefore, the Divine Being has thought proper to create an external world, it can be of no proper use to give us sensations or ideas. It must be he himself that impresses our minds with the notices of external things, without any real instrumentality of their own; so that the external world is quite a superfluity in the creation. If, therefore, the author of all things be a wise being, and have made nothing in vain, we may conclude that this external world, which has been the subject of so much controversy, can have no existence.”†

The following is as remarkable an instance of the ignoratio elenchi, as the history of weak reasoning probably affords. Dr. Reid had said, that when we have a certain sensation, as for example, when we hear a certain sound, we conclude immediately without reasoning, that there is some particular object by which it is produced, as for example, that a coach passes by. “There are no premises,” he adds, “by which this conclusion is inferred by any rules of logic. It is the effect of a principle of our nature common to us with the brutes.” Dr. Priestley says, “In this very mental operation or process, I think I see every part of a complete argument; and even that facility and readiness in passing from the premises to the conclusion, which argues the very perfection of intellect in the case. The process when properly unfolded, is as follows. The sound I now hear is, in all respects, such as I have formerly heard, which appeared to be occasioned by a coach passing by; ergo, this is also occasioned by a coach. Into this syllogism it appears to me that the mental process that Dr. Reid mentions may fairly be resolved.”‡ Dr. [179] Priestley is inadvertent enough to forget that the question is not whether a man can know the second time, after he has known the first, that it is an outward object which produces the sensation within him: but how he can know this from the beginning? Dr. Priestley’s syllogism resolves itself into an argument from the past to the present, which in no respect whatever touches the point in dispute.

But though Dr. Priestley is thus unsuccessful in his attempt to erect a barrier to the scepticism of Berkeley and Hume, his attacks bear dangerously upon that which was provided for us by the zeal and ingenuity of Dr. Reid. We have already contemplated the reasoning by which he shews, that the first argument of that philosopher, against Bishop Berkeley, namely, that we believe in the existence of matter, by “a principle of our nature common to us with the brutes,” resolves itself into the ipse dixit of its author. He also shows, that all his other arguments resolve themselves into misrepresentation. They all resolve themselves into attempts to turn the doctrine of Berkeley into ridicule, by ascribing to it the absurdities which would flow from a resolution not to believe in the testimony of our senses. That these absurdities do not, in the least degree result from the doctrine of Berkeley, is most certain. That they are ostentatiously ascribed to it by Dr. Reid is no less certain. And we are sorry to add, that after what he admits in a variety of places, it is impossible not to conclude, that he ascribed them, under a perfect knowledge that the imputation was undeserved. This is one of those disingenuous artifices in which zeal will sometimes not scruple to indulge itself; but from which it is painful to find that a man of the intellectual and moral eminence of Dr. Reid was not entirely exempt “I resolve,” says he, in a strain of mockery very usual with him, “not to believe in my senses. I break my nose against a post that comes in my way; I step into a dirty kennel; and after twenty such wise and rational actions, I am taken up and clapt into a mad-house.” No misrepresentation, it is very certain, can be more gross than language of the description applied to the conclusions of Berkeley. The order in which the feelings or ideas of the mind, some agreeable, some disagreeable, succeed one another, said Berkeley, is known to us. It is in our power to a certain degree, to pursue the one, and avoid the other. If the feeling or idea of putting my finger to the flame of the candle takes place, I know that the painful feeling of burning will follow. I therefore avoid whatever may produce the feeling of putting my finger in the flame of the candle, knowing that it will be followed by a feeling acutely painful. In like manner, the train of ideas ludicrously expressed by the terms running my nose against a post, I know will be followed [180] by a feeling of pain. I therefore do what I can to avoid that train of ideas. Upon the supposition that matter, that is, an unknown cause of our sensations, exists; it is still clear, that it is only the knowledge which an individual possesses of the order among his feelings, a knowledge that such of them are followed by such, that guides him in all his actions. When a man is said to do something, call it running his nose against a post, or any thing else, what is the real state of the facts with regard to his mind? Is it any thing else than that there passes in it a certain train of feelings? With regard to the mind, is it not this train of feelings which really constitutes the act? But if this train of feelings, which you may call an act, if you please, is followed by pain, the man will endeavour to avoid this act, or this train of feelings. The state of the mind, therefore, and its determinations, will be exactly the same, and for exactly the same reasons, whether the material world be, or be not, supposed to exist.

We have now accomplished an object of no inconsiderable importance to the end which we have in view, a clear and succinct account of the speculations of Mr. Stewart; for we have exhibited, we trust, a pretty complete view of the state of the science, at the moment when he began to exert himself for its cultivation. As a pupil of Dr. Reid, he appears to have imbibed with fondness the doctrines of his illustrious teacher; and in his different capacities of professor and author, has employed uncommon talents of persuasion, both as a speaker and as a writer, to clothe the ideas of his master in a seducing garb; to obviate objections; to clear away imperfections; and to add to the weight of evidence by new proofs and discoveries.

The first volume of the work, to which our attention has now been called by the appearance of the second, was published so long ago as the year 1792, and has passed through several editions. In that publication, after a long introductory discourse on the nature, object, and utility of the philosophy of the human mind, the author treats of his subject under the following heads:—the powers of external perception, or the operations of sense; attention; conception, which is only distinguished from memory by not having a reference to anterior time; abstraction; the association of ideas; memory; and imagination.

On the greater part of this elegant volume, we shall have no occasion to offer any remarks; because the greater part of it is employed not in the disclosure of new ideas, nor in elucidating and enforcing the peculiar principles of the philosophy of Reid: but in training the youthful mind to reflect upon the different classes of mental phenomena, by exhibiting to view the principal facts, by warning his pupil of the more seducing errors, and putting him in possession of the most useful practical rules. On the [181] subject of the memory and the imagination, this is in a peculiar manner the case. On the subject of abstraction, the author departs from the track of his master, Dr. Reid; and illustrates in a very happy and most instructive manner in the first place, the doctrine that abstraction consists in nothing but the assignment of general names,—that nothing in reality is abstract or general but the term, conceptions as well as objects being all particular; and in the next place, the purposes to which the powers of abstraction and generalization are subservient, the difference in the intellectual character of individuals arising from their different habits of abstraction and generalization, and the errors to which we are liable in speculation and the conduct of affairs, in consequence of a rash application of general principles. In the chapters on conception and attention, some curious mental phenomena are more accurately described than by any preceding author; and in speaking of those phenomena, a more accurate use of language is at once recommended and illustrated. Nothing, however, under these heads, is so connected with any of the leading doctrines of the system which he espouses, as in this place to require any particular remark. It is when he examines what he calls the powers of external perception, or the phenomena of sense, that he comes, in a more especial manner, upon the ground occupied by the characteristic principles of Reid. Even on this topic, however, though he adopts the principles, he waves all controversy in their defence; and declares that his only purpose is “to offer a few general remarks on such of the common mistakes concerning this part of our constitution, as may be most likely to mislead him and his readers in their inquiries.” For more ample satisfaction, he refers to the writings of Dr. Reid. It is not a little remarkable to find him ever declaring, “I have studiously avoided the consideration of those questions which have been agitated in the present age, between the patrons of the sceptical philosophy, and their opponents. These controversies have, in truth, no peculiar connexion with the inquiries on which I am to enter. It is indeed only by an examination of the principles of our nature, that they can be brought to a satisfactory conclusion; but supposing them to remain undecided, our sceptical doubts concerning the certainty of human knowledge would no more affect the philosophy of the mind, than they would affect any of the branches of physics; nor would our doubts concerning even the existence of mind affect this branch of science, any more than the doubts of the Berkeleian, concerning the existence of matter, affect his opinions in natural philosophy.”

Two things here are worthy of attention. The last is, that all our speculations relating to the phenomena both of sense and of consciousness, are precisely the same, whether we believe in the [182] existence or non-existence both of matter and of mind; and if our speculations, so also our actions, which have all a reference to one and the same end. The next thing in this passage worthy of observation is, that he professes to abstain from the discussion of the questions, whether we have, or have not, evidence that matter or mind exists. In this declaration seems to be implied an admission, that the questions are by no means determined; because, if determined, it belonged to him to declare, and to make it appear that they were so. But if they are not determined, the principles of Reid are unfit to be depended upon; for, surely, if the principles of Reid are worthy of our confidence, a doubt cannot be entertained about the answer which these questions ought to receive. If we really have an instinctive propensity to believe in the existence of matter and mind; and if such an instinctive propensity is a proper ground of belief, which two propositions constitute the fundamental principles of his system of philosophy, the question as to the existence of body and mind is for ever closed. If, however, an author who says he will abstain from a controversy, proceeds to take for granted all the propositions by means of which, if true, the controvery is determined on a particular side, he does by no means abstain from the controversy, he only abstains from all the difficulties of it. Now, this error is very observable in the conduct of Mr. Stewart, by whom the truth of the above-mentioned principles of Dr. Reid is uniformly assumed. Indeed, it is an art of Mr. Stewart, not rarely exemplified, to get rid of difficulties by slipping away from them.

It is, however, to the volume which has but recently appeared, and to which our attention is more particularly summoned, that he appears to have reserved the greater part of the observations which he had to make, upon the fundamental principles of that system of philosophy which he has espoused.

The subject of this volume is, “Reason, or the Understanding, properly so called; and the various faculties and operations more immediately connected with it.”

In a preliminary dissertation, he explains the meaning to which, in the course of his speculations, he proposes to restrict the term, reason. On some occasions, he remarks, it is used in a very extensive signification, to denote the exercise of all those faculties, intellectual and moral, which distinguish us from the brutes. At other times, it is confined to a very limited acceptation, to express no more than the power of ratiocination, or reasoning. Mr. Stewart proposes to use it in a sense less extensive than the former, and less restricted than the latter; to denote “the power by which we distinguish truth from falsehood, and combine means for the attainment of our ends.” Under the [183] same title of Reason, he informs us, it is also his intention to consider “whatever faculties and operations appear to be more immediately and essentially connected with the discovery of truth, or, the attainment of the objects of our pursuit.” All the powers, then, by which we recognize and discover truth, and by which we combine means for the attainment of our ends, are the appropriated subject of the present volume.

For a man who on many occasions displays no ordinary proofs of metaphysical acumen, there is here a wonderful defect of logical distinctness. When Mr. Stewart speaks of the power of distinguishing truth from falsehood, does he mean the power of distinguishing it immediately, or the power of distinguishing it by the invention and application of media of proof? We may conjecture that he means the former, by his stating immediately afterwards, that in addition to the power of distinguishing truth from falsehood, he means to consider the faculties and operations which are connected with the discovery of truth, “more particularly the power of reasoning or deduction.” But if this really be his meaning, which may well be doubted, why did he not speak the common intelligible language, by saying that he would illustrate first, the power of distinguishing truth intuitively, next the power of discovering it by the intervention of proof. Again, when he tells us, that he is to consider the power by which we distinguish truth from falsehood, and combine means for the attainment of our ends; are we to understand that the power by which we distinguish truth from falsehood, and the power by which we combine means for the attainment of our ends, is one and the same power; or, in other words, that these are operations perfectly homogeneous? It is hardly possible to conceive that this should be his meaning: yet if it be not, how gross is the impropriety of uniting them under one title, and giving no where any indication of the diversities by which they are to be distinguished? The power of combining means for our ends, is, we must say, after so formal an introduction, very disrespectfully treated; for not another word is said to her while she remains in company:—in plainer language, till the volume is closed. In point, then, of real fact, two particulars exhaust the subject of the book; and the author, if he had spoken the best and simplest language, would have said, that his object was to consider, what happens in the mind when it distinguishes truth from falsehood without any medium; and what happens in the mind when it discovers truth by means of a medium.

There is another remark, however, which we deem it of great importance to make. It might have been expected, after what Mr. Stewart has so instructively written about the nature of abstract, general terms, in the chapter on abstraction in his [184] former volume, that he should have understood something more about the nature of the general term truth, than to imagine that there could be any useful meaning in a proposition, indicative of an intention to inquire into the nature of the faculty which distinguishes truth. We ask him what sorts of truth? Truths of smell? The faculty by which they are distinguished is the sense of smelling. Truths of light or colour? They are distinguished by the faculty of sight. Truth of what happened yesterday? That is distinguished by memory: and so we might proceed.

In thus plainly expressing our criticisms on the work of an author, of whom the reputation is deservedly so high as that of Mr. Stewart, and toward whom we are conscious of unfeigned respect, it might perhaps, be a sufficient apology to state, that in a work produced under the spur of the occasion, it would be unreasonable to expect that guarded phraseology which time and frequent revisal alone can ensure. It may, however, be proper still farther to declare, that, in our opinion, it is calculated to be of great benefit to the science, to which we are well assured that Mr. Stewart would gladly sacrifice any personal feelings of his own, and of great benefit even to Mr. Stewart himself, that unfavourable criticisms, if just, should be unsparingly expressed; because the praises which Mr. Stewart has so much been accustomed to hear have led him to employ his great talents rather in adorning the conclusions to which he had already conducted himself, than examining them with that jealous and persevering severity, which alone, in such difficult inquiries, can ensure the detection of mistakes.

On the subject of truths, if we must speak of them in the mass, it is surely obvious to remark, that they may be distinguished into two great classes. Of these, the one is the class of particular truths; truths relating to all the individual existences, corporeal or mental, in the universe. The second is the class of general truths. Now all truths relating to particular corporeal existences, are made known to us by the senses. All truths relating to particular mental existences, are made known to us by consciousness, or the interpretation of sensible signs. But particular existences are the only real existences in the universe. General existences there are none. Generalities are nothing but fictions, arbitrarily created by the human mind. Particular truths, then, are the only real truths. All general truths are merely fictions, of no use whatever, but to enable us to classify particular truths, to remember them, and to speak about them.

To recognize general truths is neither more nor less, if the doctrine of Mr. Stewart himself, concerning abstraction, be true, than to recognize the coincidence between one fiction of the human mind and another; or in other words, to recognize an [185] agreement in meaning between one form of expression and another. Into the illustration of this most important proposition, it must be seen to be impossible for us here to proceed. We cannot direct our readers to a better source of instruction than Mr. Stewart himself, in the chapter on abstraction, to which we have so repeatedly referred. “If the subjects of our resoning,” says Mr. Stewart, “be general (under which description I include all our reasonings, whether more or less comprehensive, which do not relate merely to individuals,) words are the sole objects about which our thoughts are employed.” It is impossible more explicitly to admit, that all general propositions, and all general reasonings are merely verbal; in other words, assert or deduce the sameness in point of meaning, in some one or more respects, between two general expressions. Even in the volume more immediately before us, he expressly says, “In the sciences of arithmetic and algebra, all our investigations amount to nothing more than to a comparison of different expressions of the same thing. Our common language, indeed, frequently supposes the case to be otherwise; as when an equation is defined to be, ‘A proposition asserting the equality of two quantities.’ It would, however, be much more correct to define it, ‘A proposition asserting the equivalence of two expressions of the same quantity.” It would imply an incapacity for consistent reasoning, of which we are far from suspecting Mr. Stewart, to suppose that he places any essential distinction between arithmetical or algebraical deductions, and other species of general reasoning at large; only because these sciences are possessed of more commodious signs than ordinary language affords. Indeed, upon turning to the chapter on abstraction, we find that Mr. Stewart himself expressly says; “The analogy of the algebraical act may be of use in illustrating these observations. The difference, in fact, between the investigations we carry on by its assistance, and other processes of reasoning, is more inconsiderable than is commonly imagined; and, if I am not mistaken, amounts only to this, that the former are expressed in an appropriate language, with which we are not accustomed to associate particular notions. Hence they exhibit the efficacy of signs as an instrument of thought, in a more distinct and palpable manner, than the speculations we carry on by words, which are continually awakening the power of conception.” It is, indeed, not a little remarkable, that an anthor who denies the existence of abstract ideas, and so completely recognizes the nature of general terms, should lose sight of this doctrine so frequently as Mr. Stewart, in all his remaining inquiries. In truth we are led to suspect, that Mr. Stewart arrived at his present opinions concerning abstraction, at a period pretty late in life, when his conclusions on the other parts of his subject [186] were already formed, and were committed to writing; and that the strength of his original associations permitted him not to discover the changes which an alteration in so fundamental a point required in the rest of his speculations.

We may now, then, draw together the conclusions at which which we seem to have arrived. If all truths are either particular or general, the powers by which we recognize and discover truth—about which Mr. Stewart writes with such an air of mystery, and which, after many pages of high sounding disquisition, he leaves unexplained—are tolerably obvious and familiar. With regard to all individual, that is, all real existences, the faculties by which we discover what in this case we mean by truth, are the senses and consciousness. With regard to all general propositions, the faculty of discovering what in this case is meant by truth is merely the faculty by which we trace the meaning of words.

Having thus seen by what course Mr. Stewart might very easily have arrived at the goal at which he professedly aimed, let us next contemplate as briefly as our limits constrain us, the course which he has actually pursued.

In this first chapter, he treats of what he calls, “The fundamental laws of human belief; or the primary elements of human reason.” This seems to be intended for the account of what he also calls, “The power by which we distinguish truth from falsehood,” adding, “and combine means for the attainment of our ends.” In the second chapter, he treats of “Reasoning and Deductive evidence,” that is, ratiocination, in the common acceptation of the term. The third chapter treats of the Aristotelian logic, that is, a more instrument of ratiocination; in propriety of arrangement, therefore, this chapter ought to have formed only a section of the former. The fourth and last chapter treats of the inductive logic, or the method of inquiry, pursued in the experimental philosophy. Attending to the nature of the subject, we shall perceive, that he thus treats in the first chapter, of what has been called the intuitive, or immediate recognition of truth; and in the three last, of its discovery by the intervention of proof, in which there are distinguishable two modes, the ratiocinative and inductive. It is to be observed that it is general, in other words, verbal propositions and reasonings, what the author has in view thoughout almost the whole of this voluminous inquiry; and that he endeavours to explain what takes place in the mind, without adverting (except casually, and in such a manner as by no means to give a turn to the current of his thoughts) to his own doctrine, that all affirmation and all reasoning in general terms, are only recognizing, or tracing the connection between, different expressions of the same thing.

[187]In the first chapter, he treats of two things; first, of mathematical axioms; secondly, of what he calls, “Certain laws of belief, inseparably connected with the exercise of consciousness, memory, perception, and reasoning.” Mathematical axioms are here introduced, only for the purpose of stating certain opinions which help to lay the foundation of that account of the nature of mathematical evidence, which Mr. Stewart endeavours to establish in the second chapter. To this account, we fear, it will not be in our power to advert, however desirous we may be to develope some fundamental error which it appears to us to involve. We shall therefore postpone any remarks which we may have to offer on what Mr. Stewart advances on the subject of axioms, till we see whether we can find room for any of our criticisms on the subsequent disquisition, to which his observations on axioms more immediately refer.

In the two sections in which he treats of “certain laws of belief,” &c. we are peculiarly interested; because, by these laws of belief, he means the instinctive principles of Dr. Reid. We are anxious, therefore, to discover, whether he has brought any new lights to aid in showing that they are entitled to govern our belief; or whether he has left that important point as destitute of proof as he received it from Reid; and hence the scepticism of Berkeley and Hume as little provided, even at this day, with an antidote, as it was at the time of its first publication.

He begins with mind—belief in the existence of mind. He allows that mind is not an object of consciousness. “We are conscious,” he says, “of sensation, thought, desire, volition; but we are not conscious of the existence of mind itself.” He proceeds next, to the belief of personal ideality. “That we cannot, without a very blameable latitude in the use of words, be said to be conscious of our personal identity, is a proposition,” he affirms, “still more indisputable.”

Whence then is this belief—belief in the existence of mind, and belief in our personal identity, derived? “This belief,” says Mr. Stewart, “is involved in every thought and every action of the mind, and may be justly regarded as one of the simplest and most essential elements of the understanding. Indeed it is impossible to conceive either an intellectual or active being to exist without it.”

From belief in the existence of mind, and belief of personal identity, where Mr. Stewart passes to the material world, he only says, “The belief which all men entertain of the existence of the material world, and their expectation of the continued uniformity of the laws of nature, belong to the same class of ultimate or elemental laws of thought, with those which have just been mentioned.” “These different truths,” he says, “all agree [188] in this, that they are essentially involved in the exercise of our rational powers.”

If Mr. Stewart has adduced any evidence to establish the belief of these truths, we may venture to affirm without dreading contradiction, that it is all included, to the last item, in the quotations which the last two paragraphs present. “This belief,” says he, “is involved in every thought and every action of the mind.” But what does he mean by this metaphorical, mysterious, and hence, we venture to add, unphilosophical use of the word “involved?” Every act of consciousness appears to us to be simple, one, and individual. To talk of one act of consciousness as involved, that is, wrapt up in another, having another rolled round it, we cannot help regarding as that sort of jargon which an ingenious man uses only when he is placed in that unhappy situation in which he still clings to a favourite notion, without having any thing plausible to adduce in its defence. If he had affirmed that the belief of the existence of mind and of personal identity is conjoined with every act of consciousness, that is, immediately precedes, or immediately follows it, we should at least have conceived what he meant. And all which then would have remained for us to do, would have been to ask him for the proof of his assertion.

We may suppose that this is the meaning of the ill-timed metaphor; because, as far as we are able to discover, it is the only intelligible meaning which can be assigned to it, and we do ask, what evidence of the assertion Mr. Stewart has adduced? The answer is, that he has adduced none whatsoever. He has added his ipse dixit to that of Dr. Reid; and upon that foundation, as far as they are concerned, the matter rests. In truth, the language of Mr. Stewart is far more unguarded and exceptionable, than that of Dr. Reid. That philosopher only affirmed that we had the belief, without affirming that it accompanied every mental operation, which we apprehend is by no means the fact. If we interpret justly what we are conscious of in ourselves, the operations of the mind, in their ordinary and habitual train, have no such accompaniment; and we never think of the existence of our mind and our personal identity, but when some particular occasion suggests it as an object of reflection.

He calls it “an essential element of the understanding;” in another place, he gives what he calls “this class of truths,” the distinctive name of “primary elements of human reason;” in a succeeding passage he says, “they enter as essential elements into the composition of reason itself.”

Mr. Stewart defines reason, in the sense in which he professes exclusively to use it, to be “the power by which we distinguish truth from falsehood.” Now, not to speak of the difficulty we [189] find in conceiving a compound power of the mind, a power made up of parts or ingredients, we may venture to assert, that if there be such a thing as a compound power of the mind, it must be a power made up of a union of several simple powers: into the composition of a power, nothing can enter that is essentially not a power. What then shall we say of the belief in the existence of body and mind? Is that a power? Or is it any thing more than one particular act of power, the power of believing? But what kind of a proposition is that which affirms, that a particular act of one power enters into the composition of another power?

Mr. Stewart says, “It is impossible to conceive either an intellectual or an active being to exist without the belief of the existence of its own mind, and the belief of its personal identity.” When a man uses the expression, “it is impossible to conceive,” it never means, and never can mean, any thing else than that he disbelieves strongly that which is the object of the affirmation. It is, therefore, only one of the garbs in which ipse dixit enrobes itself. But when we are in the search of reasons, ipse dixit is far from an advantage; and the more ingenious the colours in which it clothes itself, the evil is still the greater. Mr. Stewart seems, also, not to be aware, that in the very terms, “an intellectual or active being,” there is an implied petitio principii. According to the terms of the question, the existence of such a being is the very point to be proved. Whether a being, the subject of sensation and consciousness, can be, or cannot be, without a belief of its own existence, is more than we can venture to affirm; but surely a train of sensations and reflections, which is Hume’s; hypothesis, may be conceived to exist, into which train the belief of matter and of mind does not enter as a part. The curious circumstance is, that on the preceding page, Mr. Stewart himself says, “We are conscious of sensation, thought, desire, volition; but we are not conscious of the existence of mind itself; nor would it be possible for us to arrive at the knowledge of it, (supposing us to be created in the full possession of all the intellectual capacities which belong to human nature,) if no impression were ever to be made on our external senses.”

Another of his favourite phrases is, that “the truths” in question “are fundamental laws of human belief.” We need hardly renew the remark, that this is only another bold assertion, in which that is assumed which ought to be proved; a species of conduct in which a man exerts an act, not of reason, but of despotism, commanding all men, on pain of his condemnation, to believe as he does. The phrase however is, on other grounds, highly objectionable. There is even a species of absurdity in calling a truth a law of belief. A truth is an object of belief. An object of belief cannot be a law. It may be agreeable [190] to a law of the human mind that such or such a truth should be an object of belief. If Mr. Stewart means that it is agreeable to any law of the human mind that the supposed truths in question should be objects of belief, let him point it out; and then he will have accomplished what we earnestly call upon him to accomplish; for what Mr. Hume pretends to have demonstrated is, that the belief of these truths can be referred to none of the acknowledged laws of the human mind; and Mr. Stewart and Dr. Reid by evading his challenge so palpably, while they have so ostentatiously pretended to a victory, instead of weakening, have rather contributed to strengthen the foundations of his scepticism. It does not follow that, because men have very generally, or even universally, believed any particular proposition, that therefore it is agreeable to any law of the human mind to believe it; for it is surely very incident to men to agree in believing errors. Yet this is the only medium of proof, to which these philosophers have so much as pretended to appeal. Because men have always believed in these propositions, it is agreeable, they affirm, to a law of the human mind to believe them; though all the acknowledged laws of the human mind relating to belief, have, one or the other, been examined before them; and though it has been proved to their avowed satisfaction, that the belief in question can be referred to none of them.

For one thing we may justly blame Mr. Stewart. Why has he not given us a list of the laws of the human mind? This, as the author of a work on the philosophy of the human mind, was his appropriate duty; the proper scope and aim of his undertaking. If the science be not yet far enough advanced to enable the speculator to produce a list which he can present as complete, it would still be of great importance to exhibit all those which may be regarded as ascertained; with respect to the rest leaving the field open for future inquiry. Had this been done, and had the belief of the propositions to which we allude, been referred to any particular item, in the list, the question would at any rate have been put in a clear and tangible shape; and there would have been no delusion practised in the case.

Upon the principles of Mr. Stewart, if he would only reason from them correctly, we think it would not be a very tedious or difficult process to arrive at a decision. There are only two classes of truths; one of particular truths; the other of general truths. With regard to particular truths, there is no dispute whatsoever. They are all referable to the senses and consciousness. But matter, as both Dr. Reid and Mr. Stewart allow, is not an object of sense, nor is mind an object of consciousness. Excepting sense and consciousness, however, which are occupied about particular truths, we have no intellectual faculties but those which [191] are occupied about general truths. But we have already seen, that the only real truths with which we are acquainted are particular truths. General truths are merely fictions of the human mind, contrived to assist us in remembering and speaking about particular truths. According to Mr. Stewart’s chapter on abstraction, it therefore appears, that matter and mind belong to the class of fictions.

It shows how little Mr. Stewart is in the habit of examining the foundations of any of his pre-conceived opinions, to find him still repeating the assertion of Dr. Reid, that the conclusions of Berkeley with regard to the evidence of the existence of matter rest entirely upon the ideal theory, and fall with that theory to the ground. This is completely erroneous. They do not rest upon the ideal theory in the smallest degree, nor upon any theory. They rest upon nothing but the acknowledged fact, that the mind is conscious of nothing but its own feelings, and that there is no legitimate inference, as he pretends, from any thing within the mind, to the existence of matter. Dr. Reid most explicitly allows that there is no inference, on the ground either of reason or experience. And we believe it, he says, only because we have an instinctive propensity to believe it.

Notwithstanding the importance to which the power of instinct has thus been raised, as an importance which places it not merely on a level with reason, which may err, but far above reason, because it cannot err; an importance in short, which constitutes it the master and despot over reason, whose suggestions must all bend to its magisterial decisions, while they themselves remain unquestionable, it is to be remarked as a curious circumstance, that this class of philosophers have avoided to give us any systematic and detailed account of this instinct, which, as they allow, in so many words, we have in common with the brutes. It would have been of admirable use toward the solution of the serious difficulties, which, notwithstanding their hold assumptions, still crowd about the subject, had they given us a description, logically exact, of the field of action of this extraordinary power, to which they ascribe such new and wonderful effects; or, to describe more exactly what we mean, had they presented a complete enumeration, skilfully arranged, of its acts, and endeavoured to point out their most important relations. As their doctrine stands at present, we desire to knew wherein the ascription of a mental phenomenon to instinct really differs from the old and exploded ascription of physical phenomena to occult qualities. This instinct, or, as they like better to call it, this law of the mind, or this element of the reason, is distinguished by all the characteristic properties of an occult quality, and answers all the [192] same purposes in their writings, which the occult qualities of the schoolmen answered in theirs.

We have willingly pursued our remarks to some extent upon this particular topic, both because the doctrines relating to it form the characteristic feature of what is called the Scottish school, and because it is, in fact, by far the most important point of view in which their speculations can be regarded. An alarming system of scepticism was raised. The sect of philosophers in question erect a fortification against it, of which they loudly boast, as if it were impregnable. Their lofty pretensions deceive mankind, and prevent the anxiety which would otherwise be felt not to have a danger without a remedy. In the mean time this fortification of theirs is so little calculated to answer its purpose, that it has not strength to resist the slightest attack. It is highly important that the learned world should begin to be aware of this; and that new attempts should be speedily made to provide a real, instead of an apparent antidote to the subtle and perplexing principles of modern scepticism. We may rest assured that, if not answered, the fashion of them will one day revive. The wonder would be, had not the world been in such a state, that they should have remained without notice, and without influence, so long.

On the other topics which furnish the subjects of Mr. Stewart’s discussions in the present work, we can hardly find room to offer any remarks.

From considering mathematical axioms, and instinctive principles, he proceeds to reasoning, by which, in fact, he means, the passing from one proposition to another, by means of intermediate steps; that species of discourse, which may be resolved into a series of syllogisms. On the peculiar distinctions, however, of this class of operations he does not long remain. He departs to the consideration of mathematical demonstration, on which he conceives that he had new light of great importance to throw. His deductions do not appear to us of the same value as they did to himself: and we are sorry at being obliged to throw out an unfavourable idea, where we are precluded in a great measure from giving the reasons by which it is supported. Mathematical reasoning, Mr. Stewart informs us, is altogether founded upon hypothesis, namely the definitions of the figures, the properties of which are deduced. This he represents as a highly important discovery which he has made. And it is a property, he thinks, by which mathematical is remarkably distinguished from all other reasoning. To this conclusion, it appears to us, that Mr. Stewart has been led, by a forgetfulness, to which he is very liable, of his own doctrine respecting abstraction and general [193] terms. According to that doctrine all general reasoning is hypothetical, that is, proceeds upon hypotheses or fictions of the mind, just as much as mathematical reasoning; and even the differences which he so ostentatiously displays between mathematical and other general reasoning all resolve themselves into the greater imperfections of ordinary language. We are sorry to be obliged, in this place, to content ourselves with assertion; but we do not conceive it would be difficult to prove what we have asserted, had we left ourselves room.

From the chapter on the Aristotelian logic we are reluctantly compelled entirely to abstain; not that the observations appear to us to be exempt from error; but as, even where just they are not very important, nor where they are mistaken can far mislead, the demand for criticism on them is the less urgent.