[Note: This post is part of a series on the History of the Classical Liberal Tradition]

Introduction

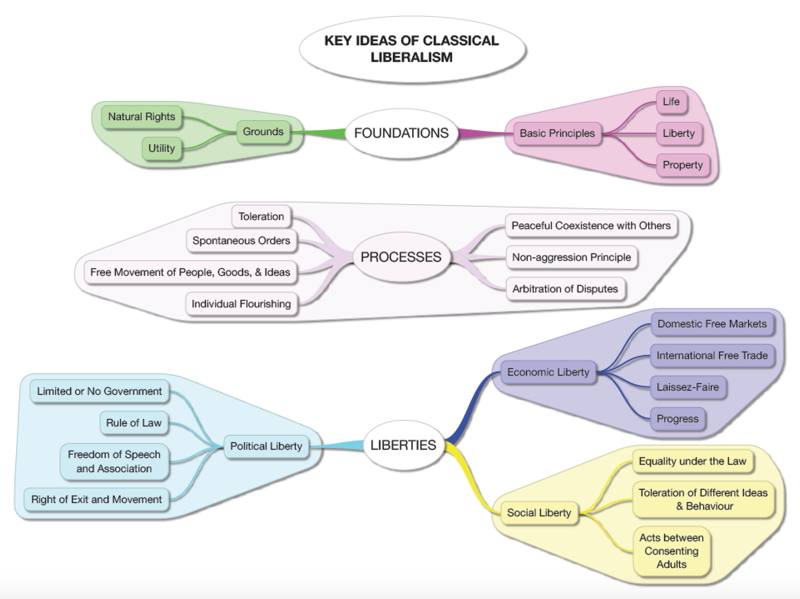

When it comes to identifying what Classical Liberals were FOR, as opposed to what they were AGAINST (see the previous post), I have divided them into three main categories: foundations (or grounds for belief), processes (or actions which people take when they live in a society), and specific liberties (or freedoms) which I have depicted in this “concept map”.

It is designed to provide an overview of what I think are the essential features of the classical liberal tradition as it has evolved over the past 400 years. It is what I think has been common to both the radical and moderate branches of classical liberalism. The “new liberals” of the late 19thC and the LINOs of the late 20th and early 21st centuries are a different kettle of fish and would require their own concept map to do justice to their political philosophy.

The Foundations of CL Ideas

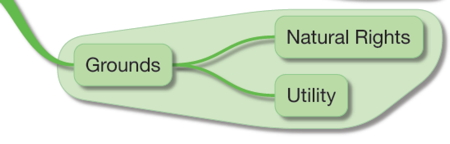

The foundations or grounds for these beliefs are based upon the following:

a set of basic principles or “rights” which all individuals have or should have, to

– life

– liberty

– property

which are based upon certain philosophical grounds, either

– natural law (God’s Law) and natural rights, or

– utility

During the 19thC the split between the classical liberals who argued for liberty on the grounds of natural law and natural rights and those who grounded it on the principle of utility (“the greatest happiness of the greatest number”) grew wider until the utilitarian position became the dominant version. It would be safe to say that most of the radical liberals were in the “natural rights” camp, while most of the moderates were in the utilitarian camp. The radical liberals thought that the utilitarians were prepared to sacrifice individual liberty if it could be shown that a utilitarian “happiness calculation” justified this (usually by politicians and bureaucrats who worked for the government). The radicals thought on the contrary that individual liberty was non-negotiable, and that once one began doing these calculations one had entered onto a slippery slope which would ultimately lead to complete socialism, which is what many of them thought the “new liberalism” had done.

The Processes or Actions Needed to Build and Sustain a Free Society

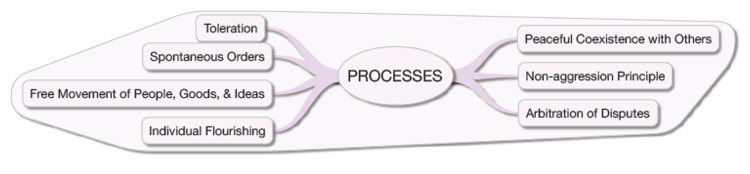

By “processes” I mean the actions people take or the ways in which people interact with each other in a social setting which will protect these rights from being violated (by other individuals and by states) and thereby allow societies, s well as individuals, to prosper and flourish.

For most radical liberals and modern-day libertarians the “non-aggression principle” (NAP) is the most important one and is “foundational”. According to Roderick Long in the EoL:

The non‐ aggression axiom is an ethical principle often appealed to as a basis for libertarian rights theory. The principle forbids “aggression,” which is understood to be any and all forcible interference with any individual’s person or property except in response to the initiation (including, for most proponents of the principle, the *threatening* of initiation) of similar forcible interference on the part of that individual.

The axiom has various formulations, but two especially influential 20th‐ century formulations are those of Ayn Rand and Murray Rothbard, who appear to have originated the term. Ayn Rand maintained that “no man may *initiate* the use of physical force against others.… Men have the right to use physical force *only* in retaliation and *only* against those who initiate its use.” This quote is similar to Murray Rothbard’s thesis that “no man or group of men may aggress against the person or property of anyone else.”

[See Rothbard and Roderick Long Non-aggression Principle: A Libertarianism.org Guide.]

Interestingly, in the Workers Party Platform (1975) the statement of this “fundamental principle” was included at the foot of every page, that:

“No man or group of men has the right to initiate the use of force, fraud or coercion against another man or group of men”. Online.

It should be noted that it is not a “non-coercion principle” as radical liberals believe that coercion may sometimes be used to prevent someone from violating a person’s rights to life, liberty, and property. What it forbids is the “initiation” of force or coercion against someone who is rightfully going about their business.

It should also be noted that radical liberals believe that this principle is universal and should apply to everyone equally, including (especially) the government and those who work for the government or are its agents. This is what makes “radical liberalism” truly “radical” as it in one stroke forbids most government activity as it has evolved over the past 400 years.

If aggression or the initiation of the use of coercion is forbidden by this principle, the kinds of activity which are permitted in a liberal society are only those that are voluntary and which are undertaken with the consent of the parties involved. Thus this includes all market activities where people voluntarily cooperate with each other, by means of the division of labour, the exchange of goods and services, and the non-violent “haggling” over prices and the terms of exchange.

It also means that if you do not wish to cooperate with other people because you might disagree with their views, the way they live their lives, or even just how they look, then the very least you must do is tolerate them by acknowledging their (equal) right to go about their peaceful business as they see fit. In other words, in a society of individuals with equal rights to enjoy their life, liberty, and property there must be “peaceful coexistence” between different groups so all might benefit from the prosperity made possible by the free market. When disputes do arise about infringement of rights they need to be arbitrated by trusted legal authorities and experts.

Classical liberals have come to realise that not all “orders”, whether economic, legal, or social, have been created by the use of (government) coercion and command. Rather these orders have arisen “spontaneously” over centuries in order to satisfy the needs of those involved and not the preconceived plans of those who rule. Once this important social fact is recognised, the rule for liberals is to allow as much voluntary cooperation as possible and to let freedom take its own course.

To summarise, the processes or actions liberals believe will allow people to interact with each other in a social setting to make both individual and social flourishing and prosperity possible are:

- adherence to the non-aggression principle

- voluntary cooperation between people

- toleration of other’s beliefs and non-violent behaviour

- the free movement of people, goods, & ideas

- peaceful coexistence with others both domestically and internationally

- the arbitration of disputes

- allowing spontaneous orders to emerge and flourish

Liberty as “the sum of all freedoms”

[The Bundles of Freedoms which make up Liberty]

Liberty should be seen as a “bundle” or “cluster” of freedoms which together make up what is “Liberty”. The following quote comes from Frédéric Bastiat’s essay “The Law” (June 1850) online of the OLL. It should be noted that English has two word for “freedom” – a Germanic one “freedom” and a Latin one (via the French) “liberty”. I have used both to make the point I think Bastiat is trying to make clearer:

> And what is liberty, this word that has the power of making all hearts beat faster and causing agitation around the world, if it is not the sum of all freedoms: freedom of conscience, teaching, and association; freedom of the press; freedom to travel, work, and trade; in other words, the free exercise of all inoffensive faculties by all men and, in still other terms, the destruction of all despotic regimes, even legal despotism, and the reduction of the law to its sole rational attribution, which is to regulate the individual law of legitimate defense or to punish injustice.

And what is “Liberty,” this word that has the power of making all hearts beat faster and of moving the (entire) world, if it is not the sum of all freedoms? — freedom of conscience, teaching, and association, freedom of the press, freedom to travel, work, and trade, in other words, the free exercise by all people of all their non-aggressive abilities (les facultés inoffensives). And, in still other terms, isn’t (freedom) the destruction of all despotic regimes, even legal despotism, and the limiting of the law (la réduction de la Loi) to its sole rational function which is to regulate the individual’s right of legitimate (self) defense and to prevent (réprimer) injustice?

Et qu’est-ce que la Liberté, ce mot qui a la puissance de faire battre tous les cœurs et d’agiter le monde, si ce n’est l’ensemble de toutes les libertés, liberté de conscience, d’enseignement, d’association, de presse, de locomotion, de travail, d’échange ; d’autres termes, le franc exercice, pour tous, de toutes les facultés inoffensives ; en d’autres termes encore, la destruction de tous les despotismes, même le despotisme légal, et la réduction de la Loi à sa seule attribution rationnelle, qui est de régulariser le Droit individuel de légitime défense ou de réprimer l’injustice.

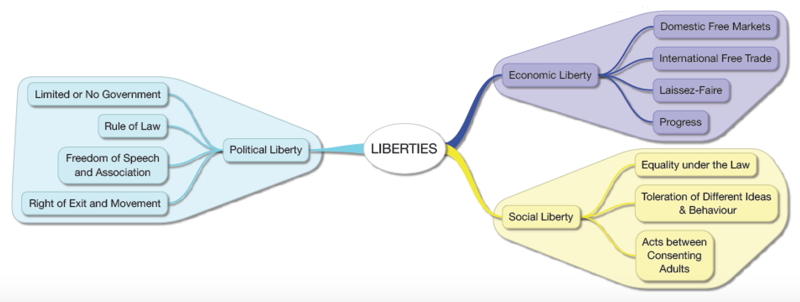

Traditionally for classical liberals, LIBERTY is made up of three main “bundles of freedoms” – political, economic, and social freedoms.

By “political freedoms” one also would include in this category “legal” freedoms. These freedoms were

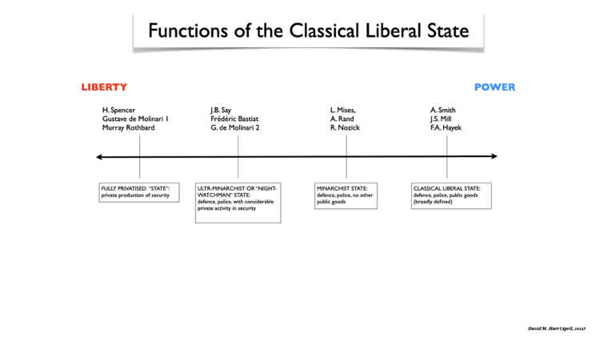

- governments which were very limited in their powers (usually limited by a written constitution and bill of rights); some radical liberals thought government should be so strictly “limited” that it virtually disappeared and would be replaced by purely voluntary, market-based private protection companies (Molinari, Rothbard); some moderate liberals like Bastiat advocated an “ultra-minimal” government, while the mainstream followed Adam Smith’s views on a “minimal government” (which permitted some provision of public goods)

- the rule of law administered by an independent judiciary;

- the right to own, sell/exchange, and gift/bequeath property

- strong protection for the contracts between individuals which regulated/or specified this transfer of property

- protection of the freedom of speech, print, and association, especially that of religion (a key issue for liberals in the 16th, 17th, and 18th centuries)

- the right to vote out a bad government and to vote in a new government in regularly held, free and open elections; liberals debated how extensive the franchise should be, with radicals calling for the broadest possible franchise (including women), while moderate liberals usually called for some property or wealth limitation; liberals were also divided on the form which a limited government might take; one division was between those liberals who favoured the English model of a constitutionally limited monarch, while others followed the American and French model of a republic

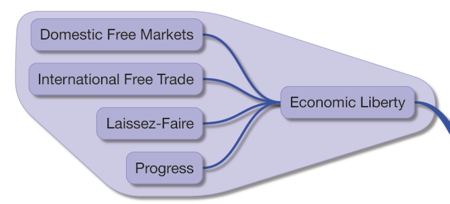

The “bundle” of economic freedoms which CLs have advocated include the following fairly standard and well known ones, such as

- free and open markets in the domestic or “home” market, where there is minimal or no regulation by governments (also known as “laissez faire”), no barriers to entry for new providers/sellers, no special privileges given to some some producers (subsidies, tariff protection), no price controls

- similarly for “foreign” or external markets, where there is so special protection for domestic producers, there are open borders for the import and export of all goods and services (i.e. “free trade”), and if there are tariffs imposed on imported goods they should be as low as possible and for “revenue purposes” only (before the introduction of income taxes, tariffs were the primary means of raising revenue for governments)

- the right to “make a profit” (and to keep this profit) made by individuals and corporations who engage in the voluntary and mutually consensual exchange of goods and services in the market

- the right to make loans to others and to charge interest on those those

- to right to choose one’s occupation or business without restriction and to enter the market to offer one’s services to others

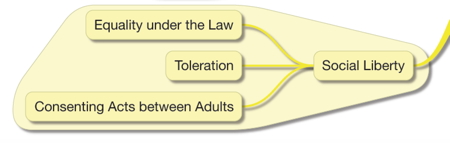

The “bundle” of freedoms known as “social freedoms” are more recent than the political and economic ones and possibly reflect the greater size, complexity, and diversity of modern societies. I think most of what are known as “social freedoms” are actually already covered by the standard political and economic freedoms listed above but many liberals thought that they needed to be emphasised and made explicit by having their own category. They include such things as:

- equality under the law – this freedom took on extra meaning as women, people of African descent (i.e. ex-slaves), gays, and drug producers, sellers, and users (whether alcoholic or other types) demanded the equal rights that others had to live their lives as they saw fit, engage in peaceful economic activity, and generally to be left alone by those with political power

- toleration of different ideas and behaviour – this was extended to include the different ways individuals wanted to organise their own “households”, i.e. to live with whomever they pleased, in whatever relationships were voluntarily entered into and mutually agreeable and beneficial, and to be free to dissolve these relationship when they were no longer so (mutually agreeable and beneficial)

- in other words, the legal and social recognition of the legitimacy of all “acts between consenting adults”

From this rather long list of “bundles” of freedoms I have selected 12 key concepts which I believe are most important for understanding what CLs have believed in over the past 400 odd years. A more detailed discussion of these “Twelve Key Concepts”, along with some recommended readings, will the subject of a future post.