The Second General Peace Congress

Paris, August 22-24, 1849

Updated: October 9, 2011

|

|

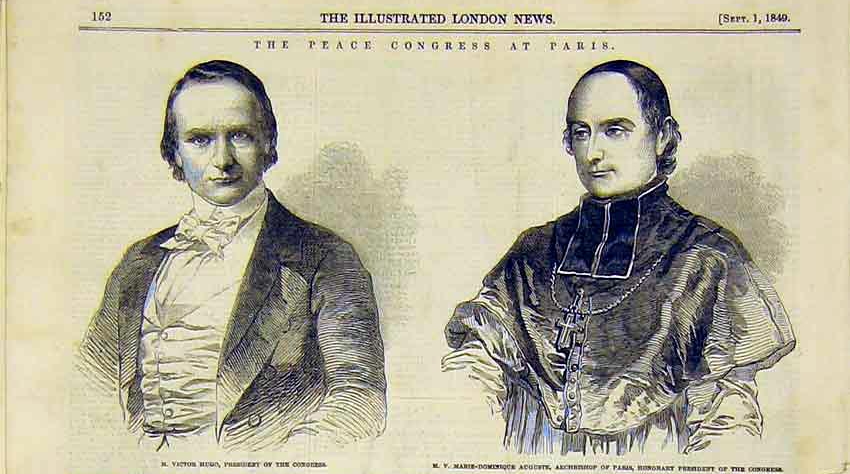

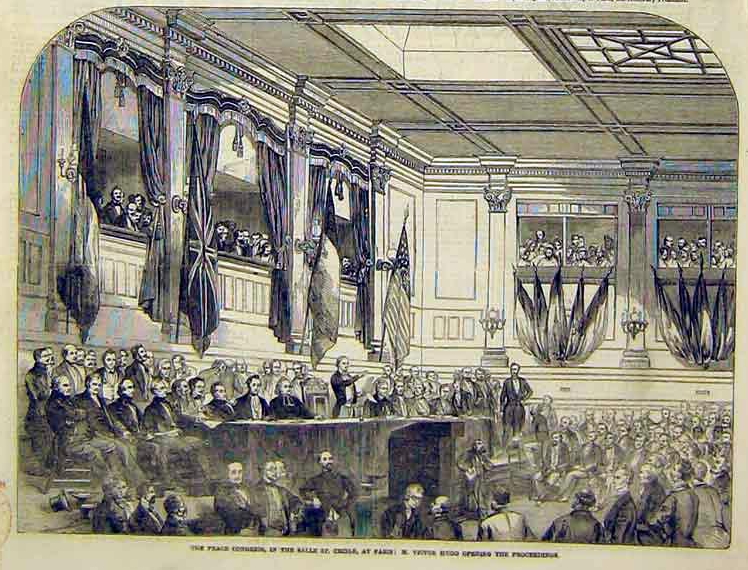

Illustrations from the Illustrated

London News, September 1, 1849 showing the President of the Congress, Victor Hugo and Marie-Dominique Auguste, the Arch-Bishop of Paris (above) and the meeting hall (below) [One could image the figure at the rostrum is Frédéric Bastiat or Richard Cobden] [See a larger version of these images JPG] |

Source: Report of the Proceedings of the Second General Peace Congress, held in Paris, on the 22nd, 23rd and 24th of August, 1849. Compiled from Authentic Documents, under the Superintendence of the Peace Congress Committee. (London: Charles Gilpin, 5, Bishopsgate Street Without, 1849). [PDF 3.4 MB]

- the report concludes with an interview with the President of the Second Republic, Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte, the nephew of Napoléon Bonaparte, who was elected for 4 years on 10 December 1848.

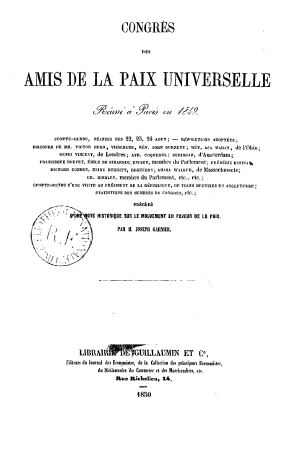

There is a French version of this book with the added bouns of a short essay on the history of the peace movement by Joseph Garnier, the editor of the Journal des Économistes:

- Congrès des amis de la paix universelle réuni à Paris en 1849 : compte-rendu, séances des 22, 23, 24 Aout; - Résolutions adoptées; discours de Mm. Victor Hugo, Visschers, Rév. John Burnett; Rév. Asa Mahan, de l'Ohio; Henri Vincent, de Londres; Ath. Coquerel; Suringar, d'Amsterdam; Francisque Bouvet, Émile de Girardin; Ewart, membre du Parlement; Frédéric Bastiat; Richard Cobden, Elihu Burritt, Deguerry; Amasa Walker, de Massachussets; Ch. Hindley, membre du Parlement, etc., etc.; Compte-rendu d'une visite au Président de la République, de trois meetings en Angleterre; statisique des membres du congrès, etc.; précédé d'une Note historique sur le mouvement en faveur de la paix, par M. Joseph Garnier [PDF 3.1 MB]

|

|

|

Frédéric Bastiat (1801-1850) |

Richard Cobden (1804-1865) |

|

|

Joseph Garnier (1813-1881) |

Table of Contents:

- Preface

- Contents

- The Peace Congress at Paris, 1849

- Proceedings

PREFACE.

Having been entrusted by the Peace Congress Committee with the task of preparing a Report of the proceedings of the Peace Congress, held in Paris in August last, we have endeavoured, whilst presenting a full and accurate record of the speeches delivered, and the most important documents laid before the Congress, to avoid unnecessarily extending the Report by lengthened narrative or comment.

The speeches, in nearly all cases, have been translated or copied from the manuscripts furnished by the speakers themselves; the remainder have been collated from the reports which appeared in the various French and English newspapers. The Essays are printed without any abbreviation, and the Letters nearly so.

The lists of American, Belgian, and British Delegates and Visitors, are as full and correct as it was possible to make them, but we regret that we have been unable to obtain a list of the French, German, and Italian members of the Congress.

The question as to the most suitable place for holding the next Congress having been fully discussed, both in the English and French Committees, Frankfort has been unanimously fixed upon as combining the greatest advantages, both from its central situation, and the sympathy felt in the movement by many of the leading minds of Germany.

It is hoped that the Congress of 1850 will demonstrate equally, if not in a still higher degree, the growing interest felt in this important effort to promote and consolidate the permanent peace of nations.

Edmund Fry,

A. R. Scoble.

15, New Broad Street, London,

October 25th, 1849.

CONTENTS.

Introduction. Preliminary Observations—Formation of a Peace Society in Paris—Visit of Messrs. Pmrritt and Richard to Paris—Circular issued by the Peace Congress Committee—Letter from M. Dufaure— Preparations in England—Meeting at Radley's Hotel—Journey to Paris 1—8

First Session Of The Congress. Constitution of the Bureau—M. Victor Hugo's Inaugural Address—Adoption of Rules—Letter from the Archbishop of Paris—Resolution thereon—Speech of M. Visschers—Award of prizes for essays on Peace—Dr. Godwin's treatise on International Arbitration—Speeches of Messrs. Bonnelier, Burnet, De Gueroult, Peut, Mahan, Journet, Vincent, Guyard, and Cobden—Adoption of the first resolution ............ 9—32

Second Session. Preliminary Business — Speeches of Messrs. Coqnerel, Suringar, Bouvet, Vincent, Avigdor, Girardin, Ewart, Bastiat and Cobden —Adoption of the second, fifth, sixth and seventh resolutions . . 33 54

Third Session. Preliminary Business—Letters from Messrs. B6ranger and Barbier—Mr. Burritt's Essay on a Congress of Nations—Speeches of Messrs. Deguerry, Walker, Bodenstedt, Billecoq, Hindley, Miall, and Brown—Adoption of the third resolution—Speeches of Messrs. Cobden, Feline, Girardin, Sturge, D'Eichthal, and Pyne—Adoption of the fourth and eighth resolutions—Proposition of M. Visschers—Resolution thereon —Speeches of Messrs. Durkee and Pennington—Proposition and adoption of Votes of Thanks—M. Victor Hugo's closing address . . . 55—88

Conclusion. Soiree at M. de Tocqueville's—Religious services on Sunday —Visit to Versailles—Meeting there—Speeches of Messrs Cobden, Bowly, Godwin, Allen, Clark, Davis, Cordner, Clappand Burritt—Poem by Rev. E. Davis—Speech of M. Aries Dufour—Visit to Saint Cloud— Return to London .......... 89—97

Appendix A. List of the American, Belgian and British Delegates and Visitors 99—100

Appendix B. Letters and Addresses received by the Congress . 107—119

Appendix C.— Interview with the President of the French Republic . 120

THE PEACE CONGRESS AT PARIS, 1849.

The Congress which was held at Brussels in 1848, did much to shake the incredulity of those who regarded the Peace Movement as an impracticable utopia. Many who had looked with contempt or indifference upon the educational efforts of committees at home, were startled into something like respectful attention to an international deliberation of such a character as that presented by the Peace Congress at Brussels. It dispelled one of the supposed necessities of the war-system—namely, the want of a guarantee that other nations would reciprocate our efforts to establish permanent and universal peace. The reception which the friends of peace met with, both from the Government and people of Belgium, was such as to refute most decisively the idea that no reliance could be placed upon our continental neighbours for sympathy and support in efforts to overthrow the war-system, and to place our international relations upon such a footing, that any disputes arising between governments might be adjusted by peaceful arbitrement, without any appeal to the sword. The public character of this demonstration, and the marked success with which it was conducted, brought the Peace Movement prominently into notice. It was discussed extensively in the newspapers, not only in this country, but throughout the Continent, and with a much larger measure of approval than could have been anticipated. Doubts and objections were still advanced by some, but in almost every case, the motives and objects of those who conducted the movement were approved and applauded.

Encouraged by the success of the 'first attempt to erect a continental platform for the discussion of this great question, it was resolved, at a conference of the friends of peace, held in London, immediately after the Brussels Congress, to prepare for a second Congress, to be held in Paris, in the month of August, 1849. The winter of 1848 was spent by the friends of Peace in this country in active operations to sustain Richard Cobden's motion in the House of Commons, for International Arbitration as a substitute for War. Upwards of 150 public meetings were held in different parts of the kingdom in support of this movement, and at most of these meetings allusion was made to the proposed Peace demonstration in the City of Paris. Everywhere the proposition was received with approbation so cordial and enthusiastic, that it was evident the popular sympathy went entirely with it; and although doubts and fears were occasionally expressed as to the obstacles which might be presented from the political condition of France, yet no opposition was offered calculated to retard for a moment the preliminary operations which it was resolved to institute.

Communications were opened with M. Francisque Bouvet, Member of the French National Assembly, and Ernest Lacan, both of whom had attended the Congress at Brussels, and who warmly approved of the object contemplated in the proposed Congress at Paris. Through their influence, the subject was brought under the notice of several men of high standing in Paris, and their interest excited in this effort to promote permanent international peace. Early in January, Ernest Lacan had an interview with Lamartine, who expressed his entire approval and sympathy in the Peace Movement.

The question of Peace was brought under the notice of the House of Assembly, on the 12th of January, by M. Bouvet, in a motion proposing the establishment of a Congress of Nations as a substitute for War. A Committee of the House was appointed to consider M. Bouvet's proposition, which deliberately recorded its conviction that "war was a violation of the laws of morality and charity, and that the suggestion of Arbitration, mutually agreed upon by all Governments, and their simultaneous disarmament, were only in accordance with the dictates of common sense." At the same time, the committee decided that in the then disturbed state of the Continent, it would not be expedient for France to attempt to carry out M. Bouvet's proposition.

The interchange of friendly excursion visits between large parties of the French National Guards and of individuals from this country, tended much to predispose the French people in favour of the Peace Movement, one result of which was the formation of a Society in Paris, which first assumed the title of " The Society of the Union of the Peoples," but shortly exchanged that name for the more expressive one, of "The Society for the Promotion of Universal Peace," the following being one of its regulations :—

"This Society shall have for its object the peace, conciliation, and brotherhood of all peoples. Among the means to be employed, one is, to promote great international Congresses, at which shall be laid down, at some future time, the definitive basis of permanent and universal peace."

Of this Society, M. Bouvet was elected the president.

On the 18th of April, the Secretaries of the Peace Congress Committee (the Pvev. Henry Richard and Elihu Burritt) proceeded to Paris to make the necessary arrangements for the formation of a Committee of Organization, to whose care should be confided the preparations required in France for the proposed Congress, in August, and they were joined by M. Auguste Visschers, who, as President of the Brussels Congress, had most cordially identified himself with this movement. The first object to be attained was to secure the confidence and co-operation of some of the most influential men in Paris—and for this purpose, interviews were had with Lamartine, Victor Hugo, Emile de Girardin, Horace Say, P. Bastiat, the Abbe Deguerry, M. Coquerel, and many other of the leading minds of France.

These gentlemen having been fully informed of the purposes and character of the proposed Congress, gave in their adhesion with great cordiality, consented to act upon the committee, and rendered very valuable assistance in giving weight and character to the demonstration.

At this time, public attention was so entirely absorbed in France in the approaching elections, that it was found necessary to suspend active operations in that country for a time; the secretaries, therefore, returned to London on the 8 th of May, and an extensive correspondence was immediately opened with friends in various parts of America, urging upon them the importance of using every effort to send a large and influential Delegation from the United States to attend the Congress in Paris.

In the month of June, there was a renewal of violent political excitement in Paris, occasioned by the French attack upon Rome. An insurrectionary movement was attempted on the 14th, which was, however, speedily suppressed by military force, and Paris was declared in a state of siege. At the same time, the cholera made its appearance, and prevailed fearfully in the city, the deaths amounting, at one period, to six hundred a-day. This combination of circumstances created much anxiety in the minds of the committee and friends of the movement in this country, lest it should present insuperable barriers to the holding of the Congress in Paris; and it was found, from correspondence with the friends there, that in the then excited state of public feeling, there would be no hope of retaining the active co-operation of those gentlemen who had engaged to act upon the Committee of Organization. In this country, however, the feeling was strong that much of the moral influence of the Congress would be lost, if it were held in any other locality than Paris; and although for a time the prospect seemed clouded and discouraging, the committee resolved to prosecute their high enterprise with renewed vigour, and to allow no obstacles to interfere for the removal of the Congress elsewhere, provided the authorization of the French Government were not withheld. Happily there was a speedy restoration of order in the capital, and the cholera so far abated in its violence, that confidence became quickly renewed, and the preparations proceeded without any further serious obstacle.

The committee at this time derived much important aid from their valuable coadjutor, George Sumner, Esq., an American gentleman residing in Paris, who came over from Paris purposely to assist in the deliberations of the committee, and to unite in opening an extensive correspondence with persons whom it was thought desirable to interest in the movement in Germany, Holland, and other European states, explaining to them the character and objects of the Congress, and soliciting their co-operation in securing the attendance of a good delegation from their respective countries.

On the 23rd of June, the following circular was issued by the committee, and sent to a very large number of the friends of peace throughout Great Britain.

"Peace Congress Committee,

"15, New Broad Street, June 26th, 1849.

"Dear Sir,—We are instructed by the Peace Congress Committee to inform you, that the deputation which recently visited Paris for the purpose of making arrangements for the great Congress to be held there in the month of August next, was received with the utmost cordiality. A number of very influential gentlemen, including several leading members of the National Assembly, and eminent writers and philanthropists, fully approving of the proposed measure, have heartily responded to the invitation to unite in a committee, for the purpose of making the approaching demonstration in favour of International Peace as effective as possible. From communications recently received from the United States, we learn that our American friends are exerting themselves with great zeal and success in securing a large delegation to represent them on this important occasion. The committee, therefore, deem it indispensable, that the attention of the friends of Peace throughout the United Kingdom should be immediately directed to the selection and appointment of proper persons as their representatives in the Paris Congress.

"As it is of great importance that the principle affirmed at the Brussels Congress should be the basis of the one to be held in Paris, it is to be taken for granted, that every gentleman elected as a delegate holds that principle, which is thus embodied in the first resolution adopted as the foundation of the proceedings on that occasion:

"' That an appeal to arms for the purpose of effecting the settlement of differences between nations, is a custom condemned alike by religion, reason, justice, humanity, and the interest of peoples; and that it is therefore the duty of the civilized world to adopt measures calculated to bring about the entire abolition of war.'

"The committee respectfully suggest that, other qualifications being equal, it would be desirable to appoint gentlemen of local influence, whose character, abilities, and position, may give weight to the delegation.

"It is also suggested that the following parties would be peculiarly eligible :—

"Officers or representatives of Auxiliary Peace Societies, or branches of the League of Universal Brotherhood, who may be appointed by their respective societies.

"Ministers of religion, or members of christian churches, who may be deputed by the congregations with which they are connected.

"Delegates chosen and appointed at public meetings called for that purpose, in any city, town, or district.

"Representatives of religious and philanthropic associations, whether for local, national, or foreign operations.

"Persons specially nominated by the vote of the Peace Congress Committee.

"The representatives of civic, municipal, and literary bodies, agreeing in the principles and objects of the Congress.

"As there may be gentlemen, however, in every way suitable, and who are prepared also, to take part in the Congress, but who may not be appointed by any public body, the committee will be happy to receive proposals from such parties, in order to arrange for their admission into the general delegation.

"Tickets of admission as visitors will be provided for the ladies and gentlemen who may be disposed to accompany the delegation, and to be present at the Congress.

"The committee hope soon to be able to announce the precise time of holding the Congress, the arrangements for the journey, and the expense to each delegate, dec, &c. In the mean time they would be happy to receive suggestions from, or to give information to, their friends in the country, in reference to the visit to Paris, as it is their anxious desire to consult the personal convenience and comfort of the delegation, as far as it may be compatible with the great object in view.

"In conclusion, the committee cannot refrain from expressing the hope, that all those who may visit Paris on this great occasion, will bear in mind that their deportment will very materially influence the opinion formed of the cause of peace by the French, and other inhabitants of the Continent. The importance, at this juncture, of a right impression is too evident to require a single comment; and the fervent desire of the committee is, that the delegation may be so conducted, that the visit to Paris, shall, under the Divine blessing, stimulate the French to vie with us in spreading ' Peace on earth, and good-will towards men.'

"We remain, Dear Sir,

"For the Committee,

"Yours truly,

"Henry Richard, "Elihu Burritt."

On the 5th of July the secretaries again repaired to Paris, and in concert with the members of the Paris committee, entered vigorously upon the arrangements necessary to prepare for the Congress: interviews were sought and obtained with M. de Tocqueville, the Minister for Foreign Affairs, and M. Dufaure, the Minister of the Interior,—they were fully informed of the nature and purposes of the proposed Congress, of which they very warmly expressed their approval, and promised to render every facility that the Government could afford, to enable the friends of peace to carry out the intended demonstration. The following official letter of authorization on the part of the French Government, was received by the committee.

"Gentlemen,—Conformably with the verbal explanations which you have done me the honour of making to me, and with the written request which you addressed to me on the 21st of July. I authorize the assembling of the Peace Congress in Paris, during the month of August.

"The object which this Congress has in view, is too philanthropic for me to refuse to give my consent;—besides the names of the members who form part of the Committee of Organization, give me an additional guarantee that the Congress will confine itself within the limits of its programme, and will not permit any infraction of order or of the laws.

"Receive gentlemen, the assurance of my most distinguished consideration.

"The Minister of the Interior,

"J. Dufaure."

The choice of a suitable room in which to hold the Congress was felt to be a subject of considerable importance, and the committee, after careful examination, selected the Hall of St. Cecilia, (Salle de St. Cecile,) situated in the Rue de la Chaussee d'Antin, a spacious and elegant concert-room, capable of accommodating nearly 2000 persons.

As soon as these preliminary proceedings were complete in Paris, the most active measures were instituted by the committee in London, through the metropolitan and provincial press, and by correspondence, to excite an interest in this country, and to secure a large and influential attendance of delegates; a circular was issued, announcing that arrangements had been made for conveying the party from England by railway and steamer, vid Folkestone and Boulogne, at a charge of £6. 10s. first class, and £5. 10s. second class, for each person, from London to Paris and back, including good hotel accommodation in Paris for one week. Arrangements were made to provide accommodation on the same terms for friends who might desire to attend the Congress as visitors, without any official character as delegates, and this privilege was also extended to ladies. The delegates and visitors were requested to assemble in London, on Monday, the 20th of August, and to meet at Radley's Hotel, at seven o'clock that evening, to receive final instructions respecting the journey, and the arrangements for the Congress. As the day drew near, names began to pour rapidly in to the committee, from various parts of the country. In many of the larger towns and cities, public meetings were held for the appointment of delegates: several of which were presided over by the Mayors, and were attended by a large number of the most respectable and influential inhabitants of the respective towns. Very gratifying accounts were also received from America, of the interest which the subject had excited in that country; and although the notice had been too short to conduct an effective agitation for delegates, yet it was expected that many earnest and enlightened men would come over to represent the United States.

Special invitations were sent from the London Committee, accompanied by a similar invitation in French, issued by the Committee of Organization in Paris, to all the members of parliament who voted in favour of Mr. Cobden's motion for arbitration, and to some other of the leading liberal members of the House of Commons, many of whom, though unable to attend the Congress, wrote to express their high approval of the movement, and their desire for its success.

On the evening of the 20th, the number of tickets issued and paid for, amounted to 670; and at seven o'clock, a very crowded meeting of the delegates and visitors assembled at Radley's Hotel, in Bridge Street, Blackfriars. The chair was taken by Joseph Sturge, Esq., and full information was afforded as to the regulations for the journey, and the preparations made for the reception and accommodation of the parties at Paris. It was also announced, that arrangements had been made for those who might wish to breakfast together before starting, at Burrell's Bridge House Hotel, opposite the London Bridge Station. Accordingly, about 200 friends assembled soon after seven o'clock, on the morning of the 21st, and partook of a substantial meal. At eight o'clock the whole party assembled at the station, and were conveyed by two special trains of great length to Folkestone, which town was reached about twelve o'clock; and the Queen of the Belgians and Princess Clementine steamers being ready, with their steam up, the party at once embarked, and had a very pleasant run across to Boulogne. The sea being smooth, and the day beautifully fine, few suffered from sea-sickness.

On drawing near to the French coast, the quays and shore at Boulogne were observed to be crowded with the inhabitants, who greeted the English party with loud cheers, and gave them a cordial welcome to the country— these greetings, it is needless to say, were responded to with hearty goodwill by the English. On landing, the party were received officially by the authorities of the town assembled in an adjoining building, the mayor

stating that he had received instructions from the French Government to render every facility to the delegation in landing and proceeding to Paris: for this purpose the Government had dispensed with the ordinary regulation, requiring a passport, and had also exempted the baggage of the travellers from any custom-house examination—a mark of confidence unexampled in the intercourse between the two countries. A brief acknowledgment having being tendered on the part of the delegation—the friends dispersed to the various hotels, where dinners were prepared, and at five o'clock the journey was resumed by railway in two trains, via Amiens. The party did not reach Paris until about one o'clock in the morning, and the arrival of a much larger number than had been anticipated, caused some delay in procuring sufficient omnibus accommodation, but by degrees the whole party were drafted off to the various hotels, where accommodation had been secured, and by day-break all were settled in their respective quarters.

PROCEEDINGS OF THE SECOND GENERAL PEACE CONGRESS

FIRST SESSION OF THE CONGRESS.

WEDNESDAY AUGUST 22ND, 1849.

Shortly after ten o'clock, on the morning of the 22nd, the friends repaired in large numbers to the Salle Sainte-Cecile, where the meetings of the Congress were to be held. The hall had been tastefully decorated for the occasion with faisceaux of the flags of various nations, intertwined with the tri-colour of France. The doors were opened at a little after eleven o'clock, and shortly after twelve, the whole of the vast hall was completely filled. About half the body of the hall was reserved for the delegates : the remainder, together with the galleries, was allotted to the visitors, of whom there was a very large number, both French and English. At a quarter to one o'clock, the members of the Committee of Organization, with some other gentlemen, mounted the platform, and were received with loud cheers by the audience.

M. Joseph Garnier, the secretary of the committee, then ascended the tribune, and was proceeding to read the list of the names of the French members of the Congress, when

A Member rose and said : Begin by the names of the foreign members ; it is a duty of hospitality.

The Rev. Henry Richard, Secretary of the London Peace Society, then read the list of the British delegates.* [* These lists will be found in the Appendix. We need not say that the names of many of the principal members were greeted with loud applause.]

M. Garnier then read the French list.

Mr. Elihu Bubritt read the names of the American members.

M. Garnier read the list of the Belgian members. He then stated that the Bureau would be thus constituted :—

President, M. Victor Hugo, Member of the French National Assembly.

Vice-Presidents: For France, M. l'Abbe Deguerry, cure of the Madeleine, and M. Athanase Coquerel, protestant minister, and member of the French National Assembly.

For England: Richard Cobden, Esq., M.p., and Charles Hindley, Esq., M.p., President of the London Peace Society. For the United States: the Hon. 0. Durkee, member of the American Congress, and Mr. Amasa Walker, member of the Massachusetts Legislature. For Belgium: M. Auguste Visschers, President of the Peace Congress held in Brussels last year. For Holland: Mr. W. H. Suringar, of Amsterdam. For Germany: Dr. Carove of Heidelberg.

Secretaries: The Rev. Henry Richard, and Messrs. Joseph Garnier, Elihu Burritt, and J. Ziegler.

The announcement of these names was received with loud and prolonged applause.

M. Victor Hugo, the President of the Congress then rose and delivered the following inaugural address :—

Gentlemen: Many of you have come from the most distant points of the globe, your hearts full of holy and religious feelings. You count in your ranks men of letters, philosophers, ministers of the Christian religion, writers of eminence, and public men justly popular for their talents. You, gentlemen, have wished to adopt Paris as the centre of this meeting, whose sympathies, full of gravity and conviction, do not merely apply to one nation, but to the whole world. You come to add another principle of a still superior—of a more august kind—to those that now direct statesmen, rulers, and legislators. You turn over, as it were, the last page of the Gospel—that page which imposes peace on the children of the same God ; and in this capital, which has as yet only decreed fraternity amongst citizens, you are about to proclaim the brotherhood of mankind.

Gentlemen, we bid you a hearty welcome! In the presence of such a thought and such an act, there can be no room for the expression of personal thanks. Permit me, then, in the first words which I pronounce in your hearing, to raise my thoughts higher than myself, and, as it were, to omit all mention of the great honour which you have just conferred upon me, in order that I may think of nothing else than the great thing which we have met to do.

Gentlemen, this sacred idea, universal peace, all nations bound together in a common bond, the Gospel for their supreme law, mediation substituted for war—this holy sentiment, I ask you, is it practicable? Can it be realized? Many practical men, many public men grown old in the management of affairs, answer in the negative. But I answer with you, and I answer without hesitation, Yes! and I shall shortly try to prove it to you. I go still further. I do not merely say it is capable of being put into practice, but I add that it is inevitable, and that its execution is only a question of time, and may be hastened or retarded. The law which rules the world is not, cannot be different from the law of God. But the divine law is not one of war—it is peace. Men commenced by conflict, as the creation did by chaos. Whence are they coming? From wars—that is evident. But whither are they going? To peace—that is equally evident. When you enunciate those sublime truths, it is not to be wondered at that your assertion should be met by a negative ; it is easy to understand that your faith will be encountered by incredulity ; it is evident that in this period of trouble and of dissension the idea of universal peace must surprise and shock, almost like the apparition of something impossible and ideal ; it is quite clear that all will call it utopian ; but for me, who am but an obscure labourer in this great work of the nineteenth century, I accept this opposition without being astonished or discouraged by it. Is it possible that you can do otherwise than turn aside your head and shut your eyes, as if in bewilderment, when in the midst of the darkness which still envelopes you, you suddenly open the door that lets in the light of the future?

Gentlemen, if four centuries ago, at the period when war was made by one district against the other, between cities, and between provinces—if, I say, some one had dared to predict to Lorraine, to Picardy, to Normandy, to Brittany, to Auvergne, to Provence, to Dauphiny, to Burgundy,—" A day shall come when you will no longer make wars—a day shall come when you will no longer arm men one against the other—a day shall come when it will no longer be said that the Normans are attacking the Picards, or that the people of Lorraine are repulsing the Burgundians :—you will still have many disputes to settle, interests to contend for, difficulties to resolve ; but do you know what you will substitute instead of armed men, instead of cavalry and infantry, of cannon, of falconets, lances, pikes and swords:— you will select, instead of all this destructive array, a small box of wood, which you will term a ballot-box, and from which shall issue—what ?—an assembly—an assembly in which you shall all live—an assembly which shall be, as it were, the soul of all—a supreme and popular council, which shall decide, judge, resolve everything—which shall make the sword fall from every hand, and excite the love of justice in every heart—which shall say to each,' Here terminates your right, there commences your duty: lay down your arms! Live in peace!' And in that day you will all have one common thought, common interests, a common destiny ; you will embrace each other, and recognise each other as children of the same blood, and of the same race ; that day you will no longer be hostile tribes,—you will be a people ; you will no longer be Burgundy, Normandy, Brittany, or Provence,—you will be France! You will no longer make appeals to war—you will do so to civilization." If, at the period I speak of, some one had uttered these words, all men of a serious and positive character, all prudent and cautious men, all the great politicians of the period, would have cried out, "What a dreamer! what a fantastic dream! How little this pretended prophet is acquainted with the human heart! What ridiculous folly! what an absurd chimera!" Yet, gentlemen, time has gone on and on, and we find that this dream, this folly, this absurdity, has been realized! And I insist upon this, that the man who would have dared to utter so sublime a prophecy, would have been pronounced a madman for having dared to pry into the designs of the Deity. Well, then, you at this moment say—and I say it with you—we who are assembled here, say to France, to England, to Prussia, to Austria, to Spain, to Italy, to Russia—we say to them, "A day will come when from your hands also the arms you have grasped will fall. A day will come when war will appear as absurd, and be as impossible, between Paris and London, between St. Petersburg and Berlin, between Vienna and Turin, as it would he now between Rouen and Amiens, between Boston and Philadelphia. A day will come when you, France—you, Russia—you, Italy—you, England—you, Germany—all of you, nations of the Continent, will, without losing your distinctive qualities and your glorious individuality, be blended into a superior unity, and constitute an European fraternity, just as Normandy, Britanny, Burgundy, Lorraine, Alsace, have been blended into France. A day will come when the only battle-field will be the market open to commerce and the mind opening to new ideas. A day will come when bullets and bomb-shells will be replaced by votes, by the universal suffrage of nations, by the venerable arbitration of a great Sovereign Senate, which will be to Europe what the Parliament is to England, what the Diet is to Germany, what the Legislative Assembly is to France. A day will come when a cannon will be exhibited in public museums, just as an instrument of torture is now, and people will be astonished how such a thing could have been. A day will come when those two immense groups, the United States of America and the United States of Europe shall be seen placed in presence of each other, extending the hand of fellowship across the ocean, exchanging their produce, their commerce, their industry, their arts, their genius, clearing the earth, peopling the deserts, improving creation under the eye of the Creator, and uniting, for the good of all, these two irresistible and infinite powers, the fraternity of men and the power of God." Nor is it necessary that four hundred years should pass away for that day to come. We live in a rapid period, in the most impetuous current of events and ideas which has ever borne away humanity ; and at the period in which we live, a year suffices to do the work of a century.

But, French, English, Germans, Russians, Sclaves, Europeans, Americans, what have we to do in order to hasten the advent of that great day? We must love each other! To love each other is, in this immense labour of pacification, the best manner of aiding God! God desires that this sublime object should be accomplished. And to arrive at it you are yourselves witnesses of what the Deity is doing on all sides. See what discoveries are every day issuing from human genius—discoveries which all tend to the same object—Peace! What immense progress! What simplification! How Nature is allowing herself to be more and more subjugated by man! How matter every day becomes still more the handmaid of intellect, and the auxiliary of civilization! How the causes of war vanish with the causes of suffering! How people far separated from each other so lately, now almost touch! How distances become less and less; and this rapid approach, what is it but the commencement of fraternity? Thanks to railroads, Europe will soon be no larger than France was in the middle ages. Thanks to steam-ships, we now traverse the mighty ocean more easily than the Mediterranean was formerly crossed. Before long, men will traverse the earth, as the gods of Homer did the sky, in three paces! But yet a little time, and the electric wire of concord shall encircle the globe and embrace the world. And here, gentlemen, when I contemplate this vast amount of efforts and of events, all of them marked by the finger of God—when I regard this sublime object, the well-being of mankind—peace,—when I reflect on all that Providence has done in favour of it, and human policy against it, a sad and bitter thought presents itself to my mind. It results, from a comparison of statistical accounts, that the nations of Europe expend each year for the maintenance of armies a sum amounting to two thousand millions of francs, and which, by adding the expense of maintaining establishments of war, amounts to three thousand millions. .Add to this the lost produce of the days of work of more than 2,000,000 men—the healthiest, the most vigorous, the youngest, the elite of our population—a produce which you will not estimate at less than one thousand millions, and you will be convinced that the standing armies of Europe cost annually more than four thousand millions.

Gentlemen, peace has now lasted thirty-two years, and yet in thirty-two years the enormous sum of one hundred and twenty-eight millions has been expended during a time of peace on account of war! Suppose that the people of Europe, in place of mistrusting each other, entertaining jealousy of each other, hating each other, had become fast friends—suppose they had said, that before they were French, or English, or German, they were men, and that if nations form countries, the human race forms a family; and that enormous sum of 128,000,000, so madly and so vainly spent in consequence of such mistrust, let it be spent in acts of mutual confidence—these 128,000,000 that have been lavished on hatred, let them be bestowed on love —let them be given to peace, instead of war—give them to labour, to intelligence, to industry, to commerce, to navigation, to agriculture, to science, to art ; and then draw your conclusions. If for the last thirty-two years this enormous sum had been expended in this manner, America in the meantime aiding Europe, know you what would have happened? The face of the world would have been changed. Isthmuses would be cut through, channels formed for rivers, tunnels bored through mountains. Railroads would cover the two continents; the merchant navy of the globe would have increased a hundred-fold. There would be nowhere barren plains, nor moors, nor marshes. Cities would be found where there are now only deserts. Ports would be sunk where there are now only rocks. Asia would be rescued to civilization; Africa would be rescued to man ; abundance would gush forth on every side, from every vein of the earth, at the touch of man, like the living stream from the rock beneath the rod of Moses. Misery would be no longer found ; and with misery, what do you think would disappear? Revolutions. Yes, the face of the world would be changed! In place of mutually destroying each other, men would pacifically extend themselves over the earth. In place of conspiring for revolution, men would combine to establish colonies! In place of introducing barbarism into civilization, civilization would replace barbarism.

You see, gentlemen, in what a state of blindness war has placed nations and rulers. If the 128,000,000 given for the last thirty-two years by Europe to the war which was not waged had been given to the peace which existed, we positively declare that nothing of what is now passing in Europe would have occurred. The continent in place of being a battlefield would have become an universal workshop, and in place of this sad and terrible spectacle of Piedmont prostrated, of the Eternal City given up to the miserable oscillations of human policy, of Venice and noble Hungary struggling heroically, France uneasy, impoverished, and gloomy ; misery, mourning, civil war, gloom in the future—in place, I say, of so sad a spectacle, we should have before our eyes, hope, joy, benevolence, the efforts of all towards the common good, and we should everywhere behold the majestic ray of universal concord issue forth from civilization. And this fact is worthy of meditation—that revolutions have been owing to those very precautions against war. All has been done—all this expenditure has been incurred, against an imaginary danger. Misery, which was the only real danger, has by these very means been augmented. We have been fortifying ourselves against a chimerical peril; our eyes have been turned to all sides except to the one where the black spot was visible. We have been looking out for wars when there were none, and we have not seen the revolutions that were coming on. Yet, gentlemen, let us not despair. Let us, on the contrary, hope more enthusiastically than ever. Let us not allow ourselves to be daunted by momentary commotions—convulsions which, peradventure, are necessary for so mighty a production. Let us not be unjust to the time in which we live—let us not look upon it otherwise than as it is. It is a prodigious and admirable epoch after all; and the 19th century will be, I do not hesitate to say, the greatest in the page of history. As I stated a few minutes since, all kinds of progress are being revealed and manifested almost simultaneously, the one producing the other—the cessation of international animosities, the effacing of frontiers on the maps, and of prejudices from the heart — the tendency towards unity, the softening of manners, the advancement of education, the diminution of penalties, the domination of the most literary languages—all are at work at the same time—political economy, science, industry, philosophy, legislation ; and all tend to the same object—the creation of happiness and of goodwill, that is to say—and for my own part, it is the object to which I shall always direct myself—the extinction of misery at home, and the extinction of war abroad. Yes, the period of revolutions is drawing to a close—the era of improvements is beginning. The education of people is no longer of the violent kind ; it is now assuming a peaceful nature. The time has come when Providence is about to substitute for the disorderly action of the agitator the religious and quiet energy of the peace-maker. Henceforth the object of all great and true policy will be this—to cause all nationalities to be recognised, to restore the historic unity of nations, and enlist this unity in the cause of civilization by means of peace—to enlarge the sphere of civilization, to set a good example to people who are still in a state of barbarism—to substitute the system of arbitration for that of battles—and, in a word—and all is comprised in this—to make justice pronounce the last word that the old world used to pronounce by force.

Gentlemen, I say in conclusion, and let us be encouraged by this thought, mankind has not entered on this providential course to-day for the first time. In our ancient Europe, England took the first step, and by her example declared to the people " You are free!" France took the second step, and announced to the people "You are sovereigns!" Let us now take the third step, and all simultaneously, France, England, Germany, Italy, Europe, America—let us proclaim to all nations " You are brethren!"

At the close of this address, which was frequently interrupted by outbursts of applause, the whole assembly rose and greeted the speaker with three cheers given after the English fashion.

M. Jean Journet then rose and said: I request to be allowed to make an important communication.

The President. Our first business will be to adopt a series of rules for the government of our proceedings.

The following rules were then read in French by M. Coquerel, and in English by the Rev. H. Richard :—

"I. The committee shall be composed of the president, vice-presidents, and secretaries of the Congress, with power to add to their number.

"II. The secretaries to propose the business for each day, to receive communications relative to the business of the Congress, to keep full minutes of its proceedings in French and English, and to have the care of all documents properly belonging to it.

"III. Every proposition which either one or more members of the Congress wish to bring before it, must, in the first instance, be submitted in writing to the committee, who are empowered to decide upon its relevancy, and to fix the time when it may be brought on.

"IV. The members of the Congress who wish to speak on any proposition before the chair, must send up their names to the president to be inscribed on his list, and will be heard in the order in which they stand on such list.

"V. No speaker will be allowed more than fifteen minutes, except by special leave of the Congress ; when that period is past, the president will intimate the same to the speaker.

"VI. No speaker will be allowed to speak more than once on any proposition, unless in the way of explanation. The opener of the discussion will, however, have the right of reply.

"VII. The object of the Congress being one of general and permanent interest, no speaker can be allowed to make any direct allusion to the political events of the day, or to discuss any questions of local interest. In case of any infraction of this rule, the speaker will be called to order, and should he persist, the president will withdraw from him the right to speak.

"VIII. At the close of each session, the committee will meet for consultation on all matters that may require their attention.

"IX. The resolutions proposed for the adoption of the Congress shall be decided by a majority of votes.

"X. The resolutions adopted shall be signed by the president and secretaries of the Congress.

"XI. The several resolutions adopted shall form the basis of an address or addresses that may be agreed to by the Congress, such address or addresses to be signed on behalf of the Congress, by the president, vice-presidents and secretaries.

"Note.—The members of the Congress are respectfully and urgently requested to be in their places at the commencement of the proceedings of each session ; and in case any question on a point of order should arise during the proceedings, to keep perfect silence, leaving it to the president and committee to take the necessary steps for disposing of the same."

The President: I beg the assembly to vote the adoption of the rules without any unnecessary discussion, as we have no time to lose.

The rules were thereupon adopted unanimously.

M. Jean Journet: I request to be allowed to speak upon the rules.

The President: No discussion of the rules can now be permitted: they have just been unanimously adopted. M. Gamier, one of the secretaries of the Congress, will read several important adhesions to the Congress.

M. Joseph Q-arnier then read the following letter from the Archbishop of Paris, who had been invited to act as president of the Congress :—

"Paris, August 17th.

"To The Members Of The Congress Op Universal Peace.

"Gentlemen,—I have been profoundly touched by the visit which Messrs. de la Kochefoucald Liancourt, Victor Hugo, Coquerel, and Elihu Burritt were good enough to pay me, and by the letter you have just written to me, to offer me the Presidency of the Congress of Universal Peace. This, gentlemen, is an honour, the full value of which I feel, and for which I should never be able adequately to express my gratitude. I think with you gentlemen, that war is a remnant of ancient barbarism ; that it is accordant with the spirit of Christianity to desire the disappearance of this formidable scourge from the face of the earth, and to make strenuous efforts to attain this noble and generous end. Perhaps, alas! the time has not yet come when it will be completely possible for the nations to enter upon this path. Perhaps war will continue for many years to be a cruel necessity. But it is proper, it is praiseworthy, it is excellent to labour to make the people understand that they, like individuals, ought to endeavour with the least possible delay to terminate their differences by pacific means, and that humanity and civilization will have made immense progress on the day when an end shall have been put to these fratricidal contests. I beg you therefore, gentlemen, to inscribe my name amongst the friends of the Congress of Peace ; but it is to me a source of deep regret that I cannot, on account of my health, accept the honour which you have so generously offered me of presiding over you. If my physician, who urges me to go on a journey to avoid a dangerous state of health, would nevertheless consent to let me put it off for some days, and if my neuralgic pains are not too violent, it will afford me real pleasure to be present at one of your sessions. Receive, gentlemen, together with the expression of these sentiments, the assurance of my most distinguished consideration.

"Marie Dominique Auguste

"Archbishop of Paris."

The President: I propose that the thanks of the Congress be presented to the Archbishop, and that he be nominated honorary president of the Congress.

M. Charles Duvetrier desired that the Archbishop's letter might be translated into English, for the benefit of the English and American delegates.

Mr. Cobden rose and said: The request just made appears to me to be a reasonable one, and I will myself read the letter which we have received from the Archbishop of Canterbury—I mean the Archbishop of Paris. The honourable gentleman then read the letter, and finished by proposing the nomination of the Archbishop of Paris as honorary president of the Congress.

This proposition was carried by acclamation.

Joseph Stubge, Esq., of Birmingham, then rose and said, he hoped the English friends present would not insist on having the various speeches and papers translated, as such a course would involve a needless waste of time. This proposition was received with loud cheers by the English and American delegates.

M. Joseph Garnier then proceeded to read letters from MM. Tissot and Augustin Thierry, members of the French Academy, declaring their adhesion to the principles and objects of the Congress.* [* Translations of these and many other important letters will be found in the Appendix.]

M. Visschers, president of the Brussels Peace Congress, then made the following statement of the progress of the Peace cause during the past year :—

Gentlemen, the year which has just elapsed has been marked by important labours on the part of the friends of Universal Peace, notwithstanding that Europe has been convulsed by political revolutions. In my capacity of President of the Congress which met at Brussels last year, I have to submit to you a report of the steps which have been taken to carry into effect the various measures determined on by that assembly ; and then, as some of my audience are imperfectly acquainted with the objects of peace societies, I shall give a brief account of tjjeir purpose, and of the results which have crowned their efforts. After having improved, and carried to a high degree of perfection, their various charitable and benevolent institutions, it was worthy the friends of humanity in England and the United States to extend the circle of their religious and philanthropic sentiments. Already all civilised nations have united in efforts to suppress the slave trade ; already has slavery been abolished in many countries. But other evils have awakened their solicitude, invoking the divine law and the interest of nations, they come to our homes and hearths, to shake us by the hand as friends, and to propose to us to draw closer the bonds which should unite together all the creatures of God. The Brussels Congress, held in September, 1848, was the first movement of the apostles of peace on the European continent. Four resolutions were there discussed and agreed on, for the condemnation of war, the establishment of an international jurisdiction, the adoption of an universal code of laws, and finally a general disarmament. Conformably with the wishes of the Congress, the president and the vice-presidents of the Congress repaired to London, and had the honour of presenting to the Prime Minister of England an address embodying the resolutions. The reception given to the Bureau of the Congress by Lord John Russell displayed the sentiments of sympathy which the English cabinet entertains with regard to the cause of universal peace. A few months' afterwards the doctrines of the friends of peace, introduced, in some sort, into the official sphere, made another step forward—they passed the threshold of the British Parliament. A man of persevering and active genius, the victor in a struggle in which were involved the most important interests of England, Richard Cobden, whom we number with pride amongst our vice-presidents, appeared in parliament as the promoter of a system of international arbitration. Already, on a previous occasion, in the United States of America, the committee of Congress on foreign affairs, whose spokesman was the Honourable M. Legar£, whom we have known both at Paris and Brussels, had proclaimed that the idea of an universal peace, existing under the aegis of the laws, was the ideal perfection of the social state, and that the aspiration of all minds and of all institutions already presaged its future accomplishment.

The legislature of the State of Massachusetts solemnly declared, in 1844, that arbitration ought to take the place of war ; it invited, at the same time, the central government to recommend to all the governments of Christendom the formation of a General Convention, or Universal Congress, to lay down the principles of international laws, and to institute a supreme court invested with the necessary powers for settling those differences between nations which might be submitted to its decision. Last winter the Honourable Amos Tuck, whom we hoped to have seen amongst us on the present occasion, but whom a severe indisposition detained at Boston, brought a similar proposition before the American Congress, which was earnestly supported by public opinion in America. The Constituent Assembly of France has also heard, gentlemen, the noble and sympathetic words of one of our colleagues, M. Francisque Bouvet, demanding the formation of an Universal Congress, whose object should be to secure a proportional disarmament of the various European powers, to abolish the laws of war, and to substitute in their place an international jurisdiction. The equality of nations, respect of their laws, the triumph of justice—these are the objects contemplated by the friends of peace. The means they wish to employ are the creation of international institutions, the development of international law, the increase of friendly intercourse between nations. To secure these results, the friends of peace propagate their doctrines by means of Congresses—of numerous public meetings ; they propose prizes for essays, and favour by all means in their power popular education. I have been present, gentlemen, at large public meetings in London, in Birmingham, and in Manchester. Everywhere public opinion greets with ardour the approach of the English and American apostles of peace. Large public subscriptions have been raised in support of the work. To support the motion of Mr. Cobden the friends of peace held, during a few weeks, more than 150 public meetings in various towns of the United Kingdom. On the day on which this motion was brought forward, more than a thousand petitions, signed by about 200,000 names, were laid on the table of the House of Commons. The motion was supported by seventy-nine members of that house; whereas only fourteen supported the motion for the repeal of the Corn-laws when it was first brought before parliament. Shall I pronounce the names of the leaders of this great movement who are not members of the house? I will only name one gentleman, because he is the ring of that chain which will indissolubly unite the old and the new continents. I need hardly say, I refer to Elihu Burritt.

Why can I not, gentlemen, relate to you the history of these peace societies, the origin of which is distant only a third part of a century? You will see them originating in the United States and in England, in modest habitations—in simple cottages. I will not speak to you of the peace societies of Paris, of Geneva, and of Brussels. But I would wish to teach you to bless the names of the first founders of these societies, Worcester, Channing, William Ladd, William Allen, De Sellon, De Gerando, and some others who are living at the present day. Marvellous power of a great idea! To answer our appeal, hundreds of English citizens have crossed the channel. What do I say? Our friends of the United States have traversed the ocean ; and one of them travelled two thousand miles to reach a port whence he might sail for England. France has felt a generous inspiration; the whole tiniverse applauds it. It is everywhere felt that these ideas supply a want of civilization. To traverse Europe, as our President has so well remarked, we need at the present day less time and money than were necessary two centuries ago to visit the provinces of France. The facility of communication incessantly increases ; commercial relations and the reciprocal duties of man to man multiply. We know one another better, and esteem one another more. The interests of the people are everywhere consulted ; or rather, at least, governments will see themselves obliged to consult them. This augmentation of relations necessitates a corresponding progress and development of international and commercial law.'

This sketch, gentlemen, will show you that in opening the competition, the result of which, I shall have the honour to announce to you, we have not sought merely the improvement of the condition of humanity—the supply of the wants of modern societies. We wish to arrive at the abolition of war by means of a closer federation of the peoples, and of the amelioration of their moral, commercial, and industrial relations. The liberality of the representatives of the Anglo-American societies at the Congress of Brussels had proposed a prize of 1,000 francs for the best essay on the questions discussed in that assembly. They at the same time had offered a second sum of 1,000 francs for the second and third best essays. The permanent committees of the Peace Congress, at London and at Brussels, drew up a programme and fixed the object of the competition: "The exposition of rational and practical means for attaining the abolition of War." The term fixed for sending in the essays was June 1, 1849. Twentyfive essays were forthcoming; but three arrived too late. The class of Literature and Moral and Political Sciences of the Belgian Royal Academy kindly accepted the office of adjudicators of the prizes. The remarkable report of these adjudicators analyzes each of these twentytwo essays which were sent in. The class unanimously adopted the conclusions of its commissioners. You do not expect of me an analysis of the essays which more particularly engaged the attention of the academy. The distinguished rank of the adjudicators could not fail to inspire the competitors with entire confidence. Besides the shortest analysis would require some development, and would perhaps provoke a discussion which will immediately open in reality. The essay to which the first prize was adjudged has for its motto: "The success of an enterprise depends upon the manner in which a man sets about it." On opening the letter which accompanied it, it was found that the author was M. Louis Bara, advocate, born at Lille, and living at Mons, Belgium. The second rank belongs to the essay whose motto is: "Love one another." The author is M. Alexandre Henry Clochereux, student of law in the University of Liege. The third rank is assigned to an essay bearing as its motto a quotation from Lamartine: "The ideal is only the truth seen at a distance." The author is M. E. Morhange, of Brussels.

Other essays contain thoughts worthy of notice ; but many of the competitors did not confine themselves to the exact terms of the programme: the search of means for abolishing war. On the other hand, while rewarding the authors of the best essays, neither the Academy nor the permanent committees of London and of Brussels adopt as their own all the ideas which are therein expressed. The course was open without limit. The young victors boldly availed themselves of this license. In an arena where many have fallen, and where the greatest geniuses have hesitated to tread, we cannot expect that ideas scarcely conceived should have already attained maturity.'

If this saying of the amiable philosopher Montaigne be true, that it is better to put a little lead on the imagination than to give it wings, let us leave to the future to destroy the pleasing illusion produced by our golden dreams.

I conclude, gentlemen, with a thought which brings me back to my starting-point: our object, our labours are legitimate and serious. Wo do not aspire to add a new page to the Republic of Plato, to the Utopia of Thomas More. But for the honour as well as for the safety of humanity, we hope to see arise many other pastors such as Fenelon, many such friends of humanity as Benjamin Franklin and William Ladd ; and many such learned men as Bacon, Hugo Grotius, and Montesquieu, who will write in favour of an international code.

At the conclusion of M. Visschers' speech, the president presented to M. Bara, a case containing bank notes of the value of 1,000 francs. The other two gentlemen were absent. The president then announced that a prize of 500 francs would be awarded to the author of the best collection of extracts from ancient and modern authors upon the horrors and evils of war : and that the Societe de la Morale Chrétienne would give another prize of the same value, for the best collection of extracts upon the benefits of peace. These two prizes will be awarded at the Peace Congress, to be held next year.

The President then observed, that as all the preliminary business had been disposed of, it would be well to proceed at once to the discussion of the first of the resolutions to be proposed to the Congress. It is to the following effect :—" As peace alone can secure the moral and material interests of nations, it is the duty of all governments to submit to Arbitration all differences that arise between them, and to respect the decisions of the arbitrators whom they may choose."

Mr. L. A. Chamerovzow, Assistant Secretary of the Aborigines' Protection Society, then read a French translation of the following essay by the Rev. Dr. Godwin, of Bradford, on—

International Arbitration.

That war is attended with evils of a fearful magnitude, cannot be denied. That appeals have been made to the sword by all nations from the earliest ages, is one of the most lamentable facts which the annals of our race record. That which originated in barbarism, has been continued through every stage of civilization. The vast aggregate of the mischiefs produced by all the earthquakes, storms, floods, famines, plagues, pestilences, which have afflicted the world, are insignificant when compared with the tremendous results of war. Can any means be devised to obviate so great an evil, and to prevent its recurrence 1 The object of this paper is to shew, that long and general as the practice of war has been, it is not necessary and unavoidable; that there is a principle, long known, and often applied, in the ordinary concerns of life, on which differences have been adjusted and strife terminated, which nations may adopt with unspeakable advantage, whenever differences arise which endanger their friendly intercourse.

The limits assigned to this paper will not admit of elaborate discussion. It is, therefore, a favourable circumstance, that the subject is so completely within the range of common sense, that though it admits of ample illustration, a few words, we hope, may suffice to render our meaning clear, and to establish our position.

In all the relations which men sustain to each other, differences will arise, which, unless terminated by amicable adjustment, may lead to serious consequences. In judging of any question which comes before them, individuals, classes, and communities take different points of view. Their interests, whether really or seemingly, are often opposed. Misunderstandings ensue,—offence is taken,—estrangement is succeeded by strife,—and strife often leads to vindictive measures.

This is the general process with nations. War for the sake of conquest, or national aggrandisement, or the love of glory, is, by all civilized nations of modern times, denounced. No state now assigns such reasons for making war. But occasions of misunderstanding will still arise, respecting commercial regulations, territorial or maritime rights, the interpretation of treaties, or other interests, by which friendly relations are disturbed, and peace is endangered.

There are three modes in which these differences have been treated, whether existing between individuals, or collective bodies of men; recourse has been had to Force, to Law, or to Reason.

In a barbarous state of society, Force generally prevails. The question of right obtains but little attention. The offence received is speedily followed by violence, not according to the measure, but according to the power of the party provoked. In the progress towards civilization, personal hostilities become regulated by established usages; hence the single combat, and the wager of battle, of which the modern duel is a miserable relic. A similar progress may be observed in nations. At an early period of civilization, Force was the only, or the principal means, employed to settle a disputed point; in the use of which no sovereign or chief respected any law but his own will,—acknowledged any limit but his own power. As society advanced, general usage gradually introduced certain regulations, which, still recognizing the right of states to make war on each other, required that a casus belli should be established, and that certain forms should be observed.

In highly civilized communities, Law is the interposing power which decides differences. Appeals are made to the constituted tribunals, which have authority to decide, and means to enforce their decisions. Among nations, however, no such tribunal exists, no such authoritative interference is recognized.

Abjuring Force, and declining Law, as attended with serious inconveniences, men have often appealed with advantage to Reason. They have endeavoured to convince and explain; to remove mistakes, to obtain concessions, and have sometimes had recourse to mutual compromise; or the mediation of a friend has been effectively employed. By such means amicable relations have been restored, and friendship has been renewed, between individuals or nations. In many of the transactions of life, recourse has been had to another expedient. Men are bad judges in their own cause. Few are competent to form an impartial judgment when their own interests are concerned, or their passions excited. An umpire, or arbitrator has been selected; or, if necessary, several have been chosen, men of undoubted integrity, and fully competent to understand the subject, and fairly to pronounce on its merits; and both parties have entered into an engagement to abide by the decision. The principle of Arbitration was sanctioned by the Roman law, is recognized in modern jurisprudence, recommended in the Christian scriptures, and is often resorted to in private life. It has proved the means of terminating many an unhappy difference, and of preventing litigation, by which one, or both parties might have been ruined. Nor are there wanting cases in which nations have adopted this method, or something like it, with great advantage.

Now of all the modes to which nations have recourse to decide their disputes, war is certainly the worst. It is a practice as absurd as it is unchristian and barbarous. How can a question of right be decided by the employment of brute force 1 The only problem which war can solve is, which of the contending parties is the stronger. It would be quite as rational to determine a point in morals by a throw of the dice, or a fact of history by the "science" and bravery of two prize-fighters. After all the blood and treasure expended in a long war, the question of right remains just where it was. The justice of the case cannot be in the least affected by either a victory or a defeat. How often does it happen, that after myriads have perished on the battle-field, leaving bereaved parents, brokenhearted widows, and helpless orphans to bemoan their irreparable loss; after miseries, varied and manifold, have been entailed on both the contending parties, the quarrel has been terminated by a negociation, which, except the injuries mutually inflicted and suffered, has restored things to much the same position as that in which they stood at the commencement of the war, leaving, perhaps, the original dispute entirely unnoticed.

But still it may be said, all must deprecate the miseries of war; and none but those in whose breasts a fierce ambition has extinguished the feelings of humanity, can be pleased with its occurrence; but wars are unavoidable—they are among the evils which all must deplore but which none can prevent; as they necessarily arise from the conditions of man's nature and relations, every project to abolish war, or effectually to prevent its recurrence, is a mere utopian theory, which may be beautiful, but must be useless. Merciful Father of the human race, is it possible that such is the unalterable doom of thy children; that so tremendous a curse should ever, and necessarily lie on them! The idea is intolerable; religion and reason, justice and expediency, alike call on us utterly to repudiate it. Might we not as well say, that all the crime and misery which spring from the malevolent passions of our nature are inevitable, to which no antidote can be applied, for which no remedy can be found?

We ask then, with confidence, might not every national dispute which could not be adjusted satisfactorily by negociation, be referred to the judgment of an impartial umpire, or a court of arbitration, appointed by mutual consent 1 And might it not be a standing article in every international treaty, that, instead of having recourse to war on any account, every disputed point, which could not otherwise be settled, should be determined by such Arbitration?

That the adjustment of national differences in this peaceful way, on the principle of what is just and right, is infinitely preferable to all the risks and sacrifices of war, it would be a waste of words to attempt to prove; the only reasonable ground of inquiry is, Is it practicable?

Is it not, then, a strongly favourable presumption, that this mode of settling differences has been often so successfully adopted in private life; and that the employment of it, or any approximation to it, in international disputes, has, in several recent instances, been so conducive to the peace of the world? And what war might not have been prevented in this way 1 One of the most prominent statesmen in Europe recently and publicly declared, that "on looking at all the wars which had been carried on during the last century, and examining into the causes of them, he did not see one of those wars, in which, if there had been proper temper between the parties, the questions in dispute might not have been settled without recourse to arms."

That there are difficulties in the adoption of any plan for the effectual prevention of war, must be admitted. How could it be otherwise, since the practice has been so general—since, like a garnished sepulchre, its horrid realities have been covered with so much visible ornament and splendour—since poets, orators, historians, and statesmen have contributed to surround the destructive fiend with a halo of glory, which has attracted the ardent, the ambitious, and the aspiring, to seek fame and fortune in its train,—and since so many in various ways are interested in its continuance 1 But still, it is of such ineffable importance to the interests of humanity, that the tremendous mischiefs of war should be avoided, that no plan which gives a fair promise of accomplishing this end should be pronounced impracticable, unless attended with difficulties in themselves essentially and necessarily insurmountable. And this few, we imagine, would venture to affirm respecting international arbitration.

No insuperable difficulty would be encountered in the selection of suitable persons for the office of arbitrators. Sovereigns of the greatest power, and statesmen of the highest rank, would not, we imagine, deem a trust so honourable beneath their attention. But monarchs, or the chief ministers of state, may not, perhaps, on some accounts, be deemed the most eligible. They may, from their official station, from being bound to a certain line of politics, from reasons of state, be thought less free than private individuals from such a previous bias as might interfere with a completely impartial decision. But are there not men to be found in every station, not only of acknowledged competency to understand the merits of any question of dispute which might arise, but who are also so generally known and esteemed for their high honour, their sense of justice, and their unimpeachable integrity, that not the least apprehension need be entertained in leaving to their decision affairs of the highest moment? And, admitting their liability to mistake,—which must be the case in a far higher degree with the interested and excited disputants themselves, it is scarcely possible to imagine a mistake, which, after mature deliberation, judicious and honourable men may make, the mischievous results of which could be compared with the consequences of a war.

As to the number of such umpires—the manner in which they should be chosen—whether they should constitute a board of appeal for a given time, or whether the choice should be only pro tempore, as occasions might arise,—these, with many other questions of mere arrangement, might well be left to the consideration of the contracting powers. If the principle were fully recognised, the details would present no serious difficulty.

The objection on which the greatest stress is sometimes laid, is, the impracticability of enforcing the decision of an international arbitration. But is not this impracticability more imaginary than real t Nations, as well as individuals, have a character to maintain, and with its due maintenance is connected, not only the national honour, but also the national interests. Among all civilized nations such are the reciprocal relations and the mutual intercourse, that every state is, to a certain extent, dependent on others. What nation can afford to lose its character for good faith and fair dealing? The anxiety of every government to sustain its honour in the eyes of the civilised world, is apparent from the laboured manifestoes which are drawn up and circulated when it is about to enter on war, or to do anything which may be deemed contrary to the existence of a treaty, or the general usage of states. And if a regard for integrity were insufficient of itself to prevent a breach of faith, is not the known dependence of a nation's interests on the maintenance of an honourable character an additional guarantee 1 And does not this constitute the great security which nations have for all their treaties 1 What reason is there to suppose, that while the binding nature of all other engagements is practically acknowledged, the solemn contracts of an arbitration would be disregarded?