William Shakespeare, Measure For Measure (1604-05)

|

|

| William Shakespeare (1564-1616) |

This is a part of a collection of works by William Shakespeare.

Source

The Complete Works of William Shakespeare, ed. with a glossary by W.J. Craig M.A. (London: Oxford University Press, 1916).

See the complete volume in HTML and facs. PDF.

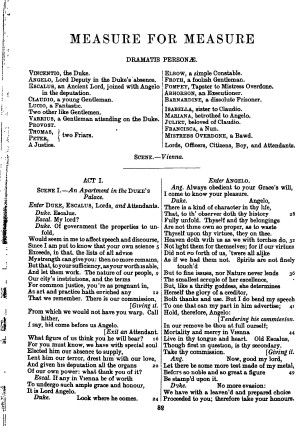

MEASURE FOR MEASURE

DRAMATIS PERSONÆ.

| Vincentio, | the Duke. |

| Angelo, | Lord Deputy in the Duke’s absence. |

| Escalus, | an Ancient Lord, joined with Angelo in the deputation. |

| Claudio, | a young Gentleman. |

| Lucio, | a Fantastic. |

| Two other like Gentlemen. | |

| Varrius, | a Gentleman attending on the Duke. |

| Provost. | |

| Thomas, } | two Friars. |

| Peter, } | |

| A Justice. | |

| Elbow, | a simple Constable. |

| Froth, | a foolish Gentleman. |

| Pompey, | Tapster to Mistress Overdone. |

| Abhorson, | an Executioner. |

| Barnardine, | a dissolute Prisoner. |

| Isabella, | sister to Claudio. |

| Mariana, | betrothed to Angelo. |

| Juliet, | beloved of Claudio. |

| Francisca, | a Nun. |

| Mistress Overdone, | a Bawd. |

| Lords, Officers, Citizens, Boy, and Attendants. | |

Scene.—Vienna.

ACT I.

Scene I.— An Apartment in the Duke’s Palace.

Enter Duke, Escalus, Lords, and Attendants.

Duke.

Escalus.

Escal.

My lord?

Duke.

Of government the properties to unfold,

Would seem in me to affect speech and discourse,

Since I am put to know that your own science 5

Exceeds, in that, the lists of all advice

My strength can give you: then no more remains,

But that, to your sufficiency, as your worth is able,

And let them work. The nature of our people, 9

Our city’s institutions, and the terms

For common justice, you’re as pregnant in,

As art and practice hath enriched any 12

That we remember. There is our commission,

[Giving it.

From which we would not have you warp. Call hither,

I say, bid come before us Angelo.

[Exit an Attendant.

What figure of us think you he will bear? 16

For you must know, we have with special soul

Elected him our absence to supply,

Lent him our terror, drest him with our love,

And given his deputation all the organs 20

Of our own power: what think you of it?

Escal.

If any in Vienna be of worth

To undergo such ample grace and honour,

It is Lord Angelo.

Duke.

Look where he comes. 24

Enter Angelo.

Ang.

Always obedient to your Grace’s will,

I come to know your pleasure.

Duke.

Angelo,

There is a kind of character in thy life,

That, to th’ observer doth thy history 28

Fully unfold. Thyself and thy belongings

Are not thine own so proper, as to waste

Thyself upon thy virtues, they on thee.

Heaven doth with us as we with torches do, 32

Not light them for themselves; for if our virtues

Did not go forth of us, ’twere all alike

As if we had them not. Spirits are not finely touch’d

But to fine issues, nor Nature never lends 36

The smallest scruple of her excellence,

But, like a thrifty goddess, she determines

Herself the glory of a creditor,

Both thanks and use. But I do bend my speech

To one that can my part in him advertise; 41

Hold, therefore, Angelo:

[Tendering his commission.

In our remove be thou at full ourself;

Mortality and mercy in Vienna 44

Live in thy tongue and heart. Old Escalus,

Though first in question, is thy secondary.

Take thy commission.

[Giving it.

Ang.

Now, good my lord,

Let there be some more test made of my metal,

Before so noble and so great a figure 49

Be stamp’d upon it.

Duke.

No more evasion:

We have with a leaven’d and prepared choice

Proceeded to you; therefore take your honours.

Our haste from hence is of so quick condition 53

That it prefers itself, and leaves unquestion’d

Matters of needful value. We shall write to you,

As time and our concernings shall importune, 56

How it goes with us; and do look to know

What doth befall you here. So, fare you well:

To the hopeful execution do I leave you

Of your commissions.

Ang.

Yet, give leave, my lord, 60

That we may bring you something on the way.

Duke.

My haste may not admit it;

Nor need you, on mine honour, have to do

With any scruple: your scope is as mine own, 64

So to enforce or qualify the laws

As to your soul seems good. Give me your hand;

I’ll privily away: I love the people,

But do not like to stage me to their eyes. 68

Though it do well, I do not relish well

Their loud applause and Aves vehement,

Nor do I think the man of safe discretion

That does affect it. Once more, fare you well. 72

Ang.

The heavens give safety to your purposes!

Escal.

Lead forth and bring you back in happiness!

Duke.

I thank you. Fare you well.

[Exit.

Escal.

I shall desire you, sir, to give me leave

To have free speech with you; and it concerns me

To look into the bottom of my place:

A power I have, but of what strength and nature

I am not yet instructed. 80

Ang.

’Tis so with me. Let us withdraw together,

And we may soon our satisfaction have

Touching that point.

Escal.

I’ll wait upon your honour.

[Exeunt.

Scene II.— A Street.

Enter Lucio and two Gentlemen.

Lucio.

If the Duke with the other dukes come not to composition with the King of Hungary, why then, all the dukes fall upon the king.

First Gent.

Heaven grant us its peace, but not the King of Hungary’s! 5

Second Gent.

Amen.

Lucio.

Thou concludest like the sanctimonious pirate, that went to sea with the Ten Commandments, but scraped one out of the table.

Second Gent.

‘Thou shalt not steal?’ 10

Lucio.

Ay, that he razed.

First Gent.

Why, ’twas a commandment to command the captain and all the rest from their functions: they put forth to steal. There’s not a soldier of us all, that, in the thanksgiving before meat, doth relish the petition well that prays for peace. 17

Second Gent.

I never heard any soldier dislike it.

Lucio.

I believe thee, for I think thou never wast where grace was said. 21

Second Gent.

No? a dozen times at least.

First Gent.

What, in metre?

Lucio.

In any proportion or in any language.

First Gent.

I think, or in any religion. 25

Lucio.

Ay; why not? Grace is grace, despite of all controversy: as, for example, thou thyself art a wicked villain, despite of all grace. 28

First Gent.

Well, there went but a pair of shears between us.

Lucio.

I grant; as there may between the lists and the velvet: thou art the list. 32

First Gent.

And thou the velvet: thou art good velvet; thou art a three-piled piece, I warrant thee. I had as lief be a list of an English kersey as be piled, as thou art piled, for a French velvet. Do I speak feelingly now? 37

Lucio.

I think thou dost; and, indeed, with most painful feeling of thy speech: I will, out of thine own confession, learn to begin thy health; but, whilst I live, forget to drink after thee.

First Gent.

I think I have done myself wrong, have I not? 44

Second Gent.

Yes, that thou hast, whether thou art tainted or free.

Lucio.

Behold, behold, where Madam Mitigation comes! I have purchased as many diseases under her roof as come to— 49

Second Gent.

To what, I pray?

Lucio.

Judge.

Second Gent.

To three thousand dolours a year. 53

First Gent.

Ay, and more.

Lucio.

A French crown more.

First Gent.

Thou art always figuring diseases in me; but thou art full of error: I am sound. 57

Lucio.

Nay, not as one would say, healthy; but so sound as things that are hollow: thy bones are hollow; impiety has made a feast of thee. 61

Enter Mistress Overdone.

First Gent.

How now! which of your hips has the most profound sciatica?

Mrs. Ov.

Well, well; there’s one yonder arrested and carried to prison was worth five thousand of you all. 66

Second Gent.

Who’s that, I pray thee?

Mrs. Ov.

Marry, sir, that’s Claudio, Signior Claudio.

First Gent.

Claudio to prison! ’tis not so. 70

Mrs. Ov.

Nay, but I know ’tis so: I saw him arrested; saw him carried away; and, which is more, within these three days his head to be chopped off.

Lucio.

But, after all this fooling, I would not have it so. Art thou sure of this? 76

Mrs. Ov.

I am too sure of it; and it is for getting Madam Julietta with child.

Lucio.

Believe me, this may be: he promised to meet me two hours since, and he was ever precise in promise-keeping. 81

Second Gent.

Besides, you know, it draws something near to the speech we had to such a purpose. 84

First Gent.

But most of all, agreeing with the proclamation.

Lucio.

Away! let’s go learn the truth of it.

[Exeunt Lucio and Gentlemen.

Mrs. Ov.

Thus, what with the war, what with the sweat, what with the gallows and what with poverty, I am custom-shrunk.

Enter Pompey.

How now! what’s the news with you?

Pom.

Yonder man is carried to prison. 92

Mrs. Ov.

Well: what has he done?

Pom.

A woman.

Mrs. Ov.

But what’s his offence?

Pom.

Groping for trouts in a peculiar river.

Mrs. Ov.

What, is there a maid with child by him?

Pom.

No; but there’s a woman with maid by him. You have not heard of the proclamation, have you? 101

Mrs. Ov.

What proclamation, man?

Pom.

All houses of resort in the suburbs of Vienna must be plucked down 104

Mrs. Ov.

And what shall become of those in the city?

Pom.

They shall stand for seed: they had gone down too, but that a wise burgher put in for them. 109

Mrs. Ov.

But shall all our houses of resort in the suburbs be pulled down?

Pom.

To the ground, mistress. 112

Mrs. Ov.

Why, here’s a change indeed in the commonwealth! What shall become of me?

Pom.

Come; fear not you: good counsellors lack no clients: though you change your place, you need not change your trade; I’ll be your tapster still. Courage! there will be pity taken on you; you that have worn your eyes almost out in the service, you will be considered. 120

Mrs. Ov.

What’s to do here, Thomas tapster?

Let’s withdraw.

Pom.

Here comes Signior Claudio, led by the provost to prison; and there’s Madam Juliet.

[Exeunt.

Enter Provost, Claudio, Juliet, and Officers.

Claud.

Fellow, why dost thou show me thus to the world?

Bear me to prison, where I am committed.

Prov.

I do it not in evil disposition,

But from Lord Angelo by special charge. 128

Claud.

Thus can the demi-god Authority

Make us pay down for our offence’ by weight.

The words of heaven; on whom it will, it will;

On whom it will not, so: yet still ’tis just. 132

Re-enter Lucio and two Gentlemen.

Lucio.

Why, how now, Claudio! whence comes this restraint?

Claud.

From too much liberty, my Lucio, liberty:

As surfeit is the father of much fast,

So every scope by the immoderate use 136

Turns to restraint. Our natures do pursue—

Like rats that ravin down their proper bane,—

A thirsty evil, and when we drink we die.

Lucio.

If I could speak so wisely under an arrest, I would send for certain of my creditors. And yet, to say the truth, I had as lief have the foppery of freedom as the morality of imprisonment. What’s thy offence, Claudio? 144

Claud.

What but to speak of would offend again.

Lucio.

What, is’t murder?

Claud.

No. 148

Lucio.

Lechery?

Claud.

Call it so.

Prov.

Away, sir! you must go.

Claud.

One word, good friend. Lucio, a word with you.

[Takes him aside.

Lucio.

A hundred, if they’ll do you any good.

Is lechery so looked after?

Claud.

Thus stands it with me: upon a true contract

I got possession of Julietta’s bed: 156

You know the lady; she is fast my wife,

Save that we do the denunciation lack

Of outward order: this we came not to,

Only for propagation of a dower 160

Remaining in the coffer of her friends,

From whom we thought it meet to hide our love

Till time had made them for us. But it chances

The stealth of our most mutual entertainment

With character too gross is writ on Juliet. 165

Lucio.

With child, perhaps?

Claud.

Unhappily, even so.

And the new deputy now for the duke,—

Whether it be the fault and glimpse of newness, 168

Or whether that the body public be

A horse whereon the governor doth ride,

Who, newly in the seat, that it may know

He can command, lets it straight feel the spur;

Whether the tyranny be in his place, 173

Or in his eminence that fills it up,

I stagger in:—but this new governor

Awakes me all the enrolled penalties 176

Which have, like unscour’d armour, hung by the wall

So long that nineteen zodiacs have gone round,

And none of them been worn; and, for a name,

Now puts the drowsy and neglected act 180

Freshly on me: ’tis surely for a name.

Lucio.

I warrant it is: and thy head stands so tickle on thy shoulders that a milkmaid, if she be in love, may sigh it off. Send after the duke and appeal to him. 185

Claud.

I have done so, but he’s not to be found.

I prithee, Lucio, do me this kind service.

This day my sister should the cloister enter, 188

And there receive her approbation:

Acquaint her with the danger of my state;

Implore her, in my voice, that she make friends

To the strict deputy; bid herself assay him: 192

I have great hope in that; for in her youth

There is a prone and speechless dialect,

Such as move men; beside, she hath prosperous art

When she will play with reason and discourse,

And well she can persuade. 197

Lucio.

I pray she may: as well for the encouragement of the like, which else would stand under grievous imposition, as for the enjoying of thy life, who I would be sorry should be thus foolishly lost at a game of tick-tack. I’ll to her.

Claud.

I thank you, good friend Lucio.

Lucio.

Within two hours.

Claud.

Come, officer, away!

[Exeunt.

Scene III.— A Monastery.

Enter Duke and Friar Thomas.

Duke.

No, holy father; throw away that thought:

Believe not that the dribbling dart of love

Can pierce a complete bosom. Why I desire thee

To give me secret harbour, hath a purpose 4

More grave and wrinkled than the aims and ends

Of burning youth.

Fri. T.

May your Grace speak of it?

Duke.

My holy sir, none better knows than you

How I have ever lov’d the life remov’d, 8

And held in idle price to haunt assemblies

Where youth, and cost, and witless bravery keeps.

I have deliver’d to Lord Angelo—

A man of stricture and firm abstinence— 12

My absolute power and place here in Vienna,

And he supposes me travell’d to Poland;

For so I have strew’d it in the common ear,

And so it is receiv’d. Now, pious sir, 16

You will demand of me why I do this?

Fri. T.

Gladly, my lord.

Duke.

We have strict statutes and most biting laws,—

The needful bits and curbs to headstrong steeds,— 20

Which for this fourteen years we have let sleep;

Even like an o’ergrown lion in a cave,

That goes not out to prey. Now, as fond fathers,

Having bound up the threat’ning twigs of birch,

Only to stick it in their children’s sight 25

For terror, not to use, in time the rod

Becomes more mock’d than fear’d; so our decrees,

Dead to infliction, to themselves are dead, 28

And liberty plucks justice by the nose;

The baby beats the nurse, and quite athwart

Goes all decorum.

Fri. T.

It rested in your Grace

T’ unloose this tied-up justice when you pleas’d;

And it in you more dreadful would have seem’d

Than in Lord Angelo.

Duke.

I do fear, too dreadful:

Sith ’twas my fault to give the people scope, 35

’Twould be my tyranny to strike and gall them

For what I bid them do: for we bid this be done,

When evil deeds have their permissive pass

And not the punishment. Therefore, indeed, my father,

I have on Angelo impos’d the office, 40

Who may, in the ambush of my name, strike home,

And yet my nature never in the sight

To do it slander. And to behold his sway,

I will, as ’twere a brother of your order, 44

Visit both prince and people: therefore, I prithee,

Supply me with the habit, and instruct me

How I may formally in person bear me

Like a true friar. Moe reasons for this action

At our more leisure shall I render you; 49

Only, this one: Lord Angelo is precise;

Stands at a guard with envy; scarce confesses

That his blood flows, or that his appetite 52

Is more to bread than stone: hence shall we see,

If power change purpose, what our seemers be.

[Exeunt.

Scene IV.— A Nunnery.

Enter Isabella and Francisca.

Isab.

And have you nuns no further privileges?

Fran.

Are not these large enough?

Isab.

Yes, truly: I speak not as desiring more,

But rather wishing a more strict restraint 4

Upon the sisterhood, the votarists of Saint Clare.

Lucto.

[Within.] Ho! Peace be in this place!

Isab.

Who’s that which calls?

Fran.

It is a man’s voice. Gentle Isabella,

Turn you the key, and know his business of him:

You may, I may not; you are yet unsworn. 9

When you have vow’d, you must not speak with men

But in the presence of the prioress:

Then, if you speak, you must not show your face,

Or, if you show your face, you must not speak.

He calls again; I pray you, answer him.

[Exit.

Isab.

Peace and prosperity! Who is’t that calls?

Enter Lucio.

Lucio.

Hail, virgin, if you be, as those cheek-roses 16

Proclaim you are no less! Can you so stead me

As bring me to the sight of Isabella,

A novice of this place, and the fair sister

To her unhappy brother Claudio? 20

Isab.

Why ‘her unhappy brother?’ let me ask;

The rather for I now must make you know

I am that Isabella and his sister.

Lucio.

Gentle and fair, your brother kindly greets you: 24

Not to be weary with you, he’s in prison.

Isab.

Woe me! for what?

Lucio.

For that which, if myself might be his judge,

He should receive his punishment in thanks: 28

He hath got his friend with child.

Isab.

Sir, make me not your story.

Lucio.

It is true.

I would not, though ’tis my familiar sin

With maids to seem the lapwing and to jest, 32

Tongue far from heart, play with all virgins so:

I hold you as a thing ensky’d and sainted;

By your renouncement an immortal spirit,

And to be talk’d with in sincerity, 36

As with a saint.

Isab.

You do blaspheme the good in mocking me.

Lucio.

Do not believe it. Fewness and truth, ’tis thus:

Your brother and his lover have embrac’d: 40

As those that feed grow full, as blossoming time

That from the seedness the bare fallow brings

To teeming foison, even so her plenteous womb

Expresseth his full tilth and husbandry. 44

Isab.

Some one with child by him? My cousin Juliet?

Lucio.

Is she your cousin?

Isab.

Adoptedly; asschool-maids change their names

By vain, though apt affection.

Lucio.

She it is. 48

Isab.

O! let him marry her.

Lucio.

This is the point.

The duke is very strangely gone from hence;

Bore many gentlemen, myself being one,

In hand and hope of action; but we do learn 52

By those that know the very nerves of state,

His givings out were of an infinite distance

From his true-meant design. Upon his place,

And with full line of his authority, 56

Governs Lord Angelo; a man whose blood

Is very snow-broth; one who never feels

The wanton stings and motions of the sense,

But doth rebate and blunt his natural edge 60

With profits of the mind, study and fast.

He,—to give fear to use and liberty,

Which have for long run by the hideous law,

As mice by lions, hath pick’d out an act, 64

Under whose heavy sense your brother’s life

Falls into forfeit: he arrests him on it,

And follows close the rigour of the statute,

To make him an example. All hope is gone, 68

Unless you have the grace by your fair prayer

To soften Angelo; and that’s my pith of business

Twixt you and your poor brother.

Isab.

Doth he so seek his life?

Lucio.

He’s censur’d him 72

Already; and, as I hear, the provost hath

A warrant for his execution.

Isab.

Alas! what poor ability’s in me

To do him good?

Lucio.

Assay the power you have. 76

Isab.

My power? alas! I doubt—

Lucio.

Our doubts are traitors,

And make us lose the good we oft might win,

By fearing to attempt. Go to Lord Angelo,

And let him learn to know, when maidens sue, 80

Men give like gods; but when they weep and kneel,

All their petitions are as freely theirs

As they themselves would owe them.

Isab.

I’ll see what I can do.

Lucio.

But speedily. 84

Isab.

I will about it straight;

No longer staying but to give the Mother

Notice of my affair. I humbly thank you:

Commend me to my brother; soon at night 88

I’ll send him certain word of my success.

Lucio.

I take my leave of you.

Isab.

Good sir, adieu.

[Exeunt.

ACT II.

Scene I.— A Hall in Angelo’s House.

Enter Angelo, Escalus, a Justice, Provost, Officers, and other Attendants.

Ang.

We must not make a scarecrow of the law,

Setting it up to fear the birds of prey,

And let it keep one shape, till custom make it

Their perch and not their terror.

Escal.

Ay, but yet 4

Let us be keen and rather cut a little,

Than fall, and bruise to death. Alas! this gentleman,

Whom I would save, had a most noble father.

Let but your honour know,— 8

Whom I believe to be most strait in virtue,—

That, in the working of your own affections,

Had time coher’d with place or place with wishing,

Or that the resolute acting of your blood 12

Could have attain’d the effect of your own purpose,

Whether you had not, some time in your life,

Err’d in this point which now you censure him,

And pull’d the law upon you. 16

Ang.

’Tis one thing to be tempted, Escalus,

Another thing to fall. I not deny,

The jury, passing on the prisoner’s life,

May in the sworn twelve have a thief or two 20

Guiltier than him they try; what’s open made to justice,

That justice seizes: what know the laws

That thieves do pass on thieves? ’Tis very pregnant,

The jewel that we find, we stoop and take it 24

Because we see it; but what we do not see

We tread upon, and never think of it.

You may not so extenuate his offence

For I have had such faults; but rather tell me,

When I, that censure him, do so offend, 29

Let mine own judgment pattern out my death,

And nothing come in partial. Sir, he must die.

Escal.

Be it as your wisdom will.

Ang.

Where is the provost?

Prov.

Here, if it like your honour.

Ang.

See that Claudio

Be executed by nine to-morrow morning:

Bring him his confessor, let him be prepar’d;

For that’s the utmost of his pilgrimage. 36

[Exit Provost.

Escal.

Well, heaven forgive him, and forgive us all!

Some rise by sin, and some by virtue fall:

Some run from brakes of ice, and answer none,

And some condemned for a fault alone. 40

Enter Elbow and Officers, with Froth and Pompey.

Elb.

Come, bring them away: if these be good people in a common-weal that do nothing but use their abuses in common houses, I know no law: bring them away. 44

Ang.

How now, sir! What’s your name, and what’s the matter?

Elb.

If it please your honour, I am the poor duke’s constable, and my name is Elbow: I do lean upon justice, sir; and do bring in here before your good honour two notorious benefactors. 51

Ang.

Benefactors! Well; what benefactors are they? are they not malefactors?

Elb.

If it please your honour, I know not well what they are; but precise villains they are, that I am sure of, and void of all profanation in the world that good Christians ought to have. 57

Escal.

This comes off well: here’s a wise officer.

Ang.

Go to: what quality are they of? Elbow is your name? why dost thou not speak, Elbow?

Pom.

He cannot, sir: he’s out at elbow. 62

Ang.

What are you, sir?

Elb.

He, sir! a tapster, sir; parcel-bawd; one that serves a bad woman, whose house, sir, was, as they say, plucked down in the suburbs; and now she professes a hot-house, which, I think, is a very ill house too. 68

Escal.

How know you that?

Elb.

My wife, sir, whom I detest before heaven and your honour,—

Escal.

How! thy wife? 72

Elb.

Ay, sir; whom, I thank heaven, is an honest woman,—

Escal.

Dost thou detest her therefore?

Elb.

I say, sir, I will detest myself also, as well as she, that this house, if it be not a bawd’s house, it is pity of her life, for it is a naughty house. 79

Escal.

How dost thou know that, constable?

Elb.

Marry, sir, by my wife; who, if she had been a woman cardinally given, might have been accused in fornication, adultery, and all uncleanliness there. 84

Escal.

By the woman’s means?

Elb.

Ay, sir, by Mistress Overdone’s means; but as she spit in his face, so she defied him.

Pom.

Sir, if it please your honour, this is not so. 89

Elb.

Prove it before these varlets here, thou honourable man, prove it.

Escal.

[To Angelo.] Do you hear how he misplaces? 93

Pom.

Sir, she came in, great with child, and longing,—saving your honour’s reverence,—for stewed prunes. Sir, we had but two in the house, which at that very distant time stood, as it were, in a fruit-dish, a dish of some three-pence; your honours have seen such dishes; they are not China dishes, but very good dishes.

Escal.

Go to, go to: no matter for the dish, sir.

Pom.

No, indeed, sir, not of a pin; you are therein in the right: but to the point. As I say, this Mistress Elbow, being, as I say, with child, and being great-bellied, and longing, as I said, for prunes, and having but two in the dish, as I said, Master Froth here, this very man, having eaten the rest, as I said, and, as I say, paying for them very honestly; for, as you know, Master Froth, I could not give you three-pence again.

Froth.

No, indeed. 112

Pom.

Very well: you being then, if you be remembered, cracking the stones of the foresaid prunes,—

Froth.

Ay, so I did, indeed. 116

Pom.

Why, very well: I telling you then, if you be remembered, that such a one and such a one were past cure of the thing you wot of, unless they kept very good diet, as I told you,— 120

Froth.

All this is true.

Pom.

Why, very well then.—

Escal.

Come, you are a tedious fool: to the purpose. What was done to Elbow’s wife, that he hath cause to complain of? Come me to what was done to her.

Pom.

Sir, your honour cannot come to that yet. 128

Escal.

No, sir, nor I mean it not.

Pom.

Sir, but you shall come to it, by your honour’s leave. And, I beseech you, look into Master Froth here, sir; a man of fourscore pound a year, whose father died at Hallowmas. Was’t not at Hallowmas, Master Froth? 134

Froth.

All-hallownd eve.

Pom.

Why, very well: I hope here be truths. He, sir, sitting, as I say, in a lower chair, sir; ’twas in the Bunch of Grapes, where indeed, you have a delight to sit, have you not? 139

Froth.

I have so, because it is an open room and good for winter.

Pom.

Why, very well then: I hope here be truths.

Ang.

This will last out a night in Russia, 144

When nights are longest there: I’ll take my leave,

And leave you to the hearing of the cause,

Hoping you’ll find good cause to whip them all.

Escal.

I think no less. Good morrow to your lordship.

[Exit Angelo.

Now, sir, come on: what was done to Elbow’s wife, once more?

Pom.

Once, sir? there was nothing done to her once. 152

Elb.

I beseech you, sir, ask him what this man did to my wife.

Pom.

I beseech your honour, ask me.

Escal.

Well, sir, what did this gentleman to her? 157

Pom.

I beseech you, sir, look in this gentleman’s face. Good Master Froth, look upon his honour; ’tis for a good purpose. Doth your honour mark his face? 161

Escal.

Ay, sir, very well.

Pom.

Nay, I beseech you, mark it well.

Escal.

Well, I do so. 164

Pom.

Doth your honour see any harm in his face?

Escal.

Why, no.

Pom.

I’ll be supposed upon a book, his face is the worst thing about him. Good, then; if his face be the worst thing about him, how could Master Froth do the constable’s wife any harm? I would know that of your honour. 172

Escal.

He’s in the right. Constable, what say you to it?

Elb.

First, an’ it like you, the house is a respected house; next, this is a respected fellow, and his mistress is a respected woman. 177

Pom.

By this hand, sir, his wife is a more respected person than any of us all.

Elb.

Varlet, thou liest: thou liest, wicked varlet. The time is yet to come that she was ever respected with man, woman, or child. 182

Pom.

Sir, she was respected with him before he married with her.

Escal.

Which is the wiser here? Justice, or Iniquity? Is this true? 186

Elb.

O thou caitiff! O thou varlet! O thou wicked Hannibal! I respected with her before I was married to her? If ever I was respected with her, or she with me, let not your worship think me the poor duke’s officer. Prove this, thou wicked Hannibal, or I’ll have mine action of battery on thee. 193

Escal.

If he took you a box o’ th’ ear, you might have your action of slander too.

Elb.

Marry, I thank your good worship for it. What is’t your worship’s pleasure I shall do with this wicked caitiff? 198

Escal.

Truly, officer, because he hath some offences in him that thou wouldest discover if thou couldst, let him continue in his courses till thou knowest what they are. 202

Elb.

Marry, I thank your worship for it. Thou seest, thou wicked varlet, now, what’s come upon thee: thou art to continue now, thou varlet, thou art to continue.

Escal.

Where were you born, friend?

Froth.

Here in Vienna, sir. 208

Escal.

Are you of fourscore pounds a year?

Froth.

Yes, an’t please you, sir.

Escal.

So. [To Pompey.] What trade are you of, sir? 212

Pom.

A tapster; a poor widow’s tapster.

Escal.

Your mistress’ name?

Pom.

Mistress Overdone.

Escal.

Hath she had any more than one husband?

Pom.

Nine, sir; Overdone by the last. 218

Escal.

Nine!—Come hither to me, Master Froth. Master Froth, I would not have you acquainted with tapsters; they will draw you, Master Froth, and you will hang them. Get you gone, and let me hear no more of you.

Froth.

I thank your worship. For mine own part, I never come into any room in a taphouse, but I am drawn in. 226

Escal.

Well: no more of it, Master Froth: farewell. [Exit Froth.]—Come you hither to me, Master tapster. What’s your name, Master tapster?

Pom.

Pompey.

Escal.

What else? 232

Pom.

Bum, sir.

Escal.

Troth, and your bum is the greatest thing about you, so that, in the beastliest sense, you are Pompey the Great. Pompey, you are partly a bawd, Pompey, howsoever you colour it in being a tapster, are you not? come, tell me true: it shall be the better for you. 239

Pom.

Truly, sir, I am a poor fellow that would live.

Escal.

How would you live, Pompey? by being a bawd? What do you think of the trade, Pompey? is it a lawful trade? 244

Pom.

If the law would allow it, sir.

Escal.

But the law will not allow it, Pompey; nor it shall not be allowed in Vienna.

Pom.

Does your worship mean to geld and splay all the youth of the city?

Escal.

No, Pompey. 250

Pom.

Truly, sir, in my humble opinion, they will to’t then. If your worship will take order for the drabs and the knaves, you need not to fear the bawds.

Escal.

There are pretty orders beginning, I can tell you: it is but heading and hanging. 256

Pom.

If you head and hang all that offend that way but for ten year together, you’ll be glad to give out a commission for more heads. If this law hold in Vienna ten year, I’ll rent the fairest house in it after threepence a bay. If you live to see this come to pass, say, Pompey told you so. 263

Escal.

Thank you, good Pompey; and, in requital of your prophecy, hark you: I advise you, let me not find you before me again upon any complaint whatsoever; no, not for dwelling where you do: if I do, Pompey, I shall beat you to your tent, and prove a shrewd Cæsar to you. In plain dealing, Pompey, I shall have you whipt. So, for this time, Pompey, fare you well. 272

Pom.

I thank your worship for your good counsel;—[Aside.] but I shall follow it as the flesh and fortune shall better determine.

Whip me! No, no; let carman whip his jade;

The valiant heart’s not whipt out of his trade.

[Exit.

Escal.

Come hither to me, Master Elbow; come hither, Master constable. How long have you been in this place of constable? 280

Elb.

Seven year and a half, sir.

Escal.

I thought, by your readiness in the office, you had continued in it some time. You say, seven years together? 284

Elb.

And a half, sir.

Escal.

Alas! it hath been great pains to you! They do you wrong to put you so oft upon ’t. Are there not men in your ward sufficient to serve it? 289

Elb.

Faith, sir, few of any wit in such matters. As they are chosen, they are glad to choose me for them: I do it for some piece of money, and go through with all. 293

Escal.

Look you bring me in the names of some six or seven, the most sufficient of your parish. 296

Elb.

To your worship’s house, sir?

Escal.

To my house. Fare you well.

[Exit Elbow.

What’s o’clock, think you?

Just.

Eleven, sir. 300

Escal.

I pray you home to dinner with me.

Just.

I humbly thank you.

Escal.

It grieves me for the death of Claudio;

But there is no remedy. 304

Just.

Lord Angelo is severe.

Escal.

It is but needful:

Mercy is not itself, that oft looks so;

Pardon is still the nurse of second woe.

But yet, poor Claudio! There’s no remedy. 308

Come, sir.

[Exeunt.

Scene II.— Another Room in the Same.

Enter Provost and a Servant.

Serv.

He’s hearing of a cause: he will come straight:

I’ll tell him of you.

Prov.

Pray you, do. [Exit Serv.] I’ll know

His pleasure; may be he will relent. Alas!

He hath but as offended in a dream: 4

All sects, all ages smack of this vice, and he

To die for it!

Enter Angelo.

Ang.

Now, what’s the matter, provost?

Prov.

Is it your will Claudio shall die to-morrow?

Ang.

Did I not tell thee, yea? hadst thou not order? 8

Why dost thou ask again?

Prov.

Lest I might be too rash.

Under your good correction, I have seen,

When, after execution, Judgment hath

Repented o’er his doom.

Ang

Go to; let that be mine: 12

Do you your office, or give up your place,

And you shall well be spar’d.

Prov.

I crave your honour’s pardon.

What shall be done, sir, with the groaning Juliet?

She’s very near her hour.

Ang.

Dispose of her 16

To some more fitter place; and that with speed.

Re-enter Servant.

Serv.

Here is the sister of the man condemn’d

Desires access to you.

Ang.

Hath he a sister?

Prov.

Ay, my good lord; a very virtuous maid, 20

And to be shortly of a sisterhood,

If not already.

Ang.

Well, let her be admitted.

[Exit Servant.

See you the fornicatress be remov’d:

Let her have needful, but not lavish, means; 24

There shall be order for’t.

Enter Isabella and Lucio.

Prov.

God save your honour!

[Offering to retire.

Ang.

Stay a little while.—[To Isab.] You’re welcome: what’s your will?

Isab.

I am a woful suitor to your honour,

Please but your honour hear me.

Ang.

Well; what’s your suit? 28

Isab.

There is a vice that most I do abhor,

And most desire should meet the blow of justice,

For which I would not plead, but that I must;

For which I must not plead, but that I am 32

At war ’twixt will and will not.

Ang.

Well; the matter?

Isab.

I have a brother is condemn’d to die:

I do beseech you, let it be his fault,

And not my brother.

Prov.

[Aside.] Heaven give thee moving graces! 36

Ang.

Condemn the fault, and not the actor of it?

Why, every fault’s condemn’d ere it be done.

Mine were the very cipher of a function,

To fine the faults whose fine stands in record, 40

And let go by the actor.

Isab.

O just, but severe law!

I had a brother, then.—Heaven keep your honour!

[Retiring.

Lucio.

[Aside to Isab.] Give’t not o’er so: to him again, entreat him;

Kneel down before him, hang upon his gown;

You are too cold; if you should need a pin, 45

You could not with more tame a tongue desire it.

To him. I say!

Isab.

Must he needs die?

Ang.

Maiden, no remedy.

Isab.

Yes; I do think that you might pardon him, 49

And neither heaven nor man grieve at the mercy.

Ang.

I will not do’t.

Isab.

But can you, if you would?

Ang.

Look, what I will not, that I cannot do.

Isab.

But might you do’t, and do the world no wrong, 53

If so your heart were touch’d with that remorse

As mine is to him?

Ang.

He’s sentenc’d: ’tis too late.

Lucio.

[Aside to Isab.] You are too cold. 56

Isab.

Too late? why, no; I, that do speak a word,

May call it back again. Well, believe this,

No ceremony that to great ones ’longs,

Not the king’s crown, nor the deputed sword, 60

The marshal’s truncheon, nor the judge’s robe,

Become them with one half so good a grace

As mercy does.

If he had been as you, and you as he, 64

You would have slipt like him; but he, like you,

Would not have been so stern.

Ang.

Pray you, be gone.

Isab.

I would to heaven I had your potency,

And you were Isabel! should it then be thus? 68

No; I would tell what ’twere to be a judge,

And what a prisoner.

Lucio.

[Aside to Isab.] Ay, touch him; there’s the vein.

Ang.

Your brother is a forfeit of the law,

And you but waste your words.

Isab.

Alas! alas! 72

Why, all the souls that were were forfeit once;

And He that might the vantage best have took,

Found out the remedy. How would you be,

If He, which is the top of judgment, should 76

But judge you as you are? O! think on that,

And mercy then will breathe within your lips,

Like man new made.

Ang.

Be you content, fair maid;

It is the law, not I, condemn your brother: 80

Were he my kinsman, brother, or my son,

It should be thus with him: he must die to-morrow.

Isab.

To-morrow! O! that’s sudden! Spare him, spare him!

He’s not prepar’d for death. Even for our kitchens 84

We kill the fowl of season: shall we serve heaven

With less respect than we do minister

To our gross selves? Good, good my lord, bethink you:

Who is it that hath died for this offence? 88

There’s many have committed it.

Lucio.

[Aside to Isab.] Ay, well said.

Ang.

The law hath not been dead, though it hath slept:

Those many had not dar’d to do that evil,

If that the first that did th’ edict infringe 92

Had answer’d for his deed: now ’tis awake,

Takes note of what is done, and, like a prophet,

Looks in a glass, that shows what future evils,

Either new, or by remissness new-conceiv’d, 96

And so in progress to be hatch’d and born,

Are now to have no successive degrees,

But, ere they live, to end.

Isab.

Yet show some pity.

Ang.

I show it most of all when I show justice;

For then I pity those I do not know, 101

Which a dismiss’d offence would after gall,

And do him right, that, answering one foul wrong,

Lives not to act another. Be satisfied: 104

Your brother dies to-morrow: be content.

Isab.

So you must be the first that gives this sentence,

And he that suffers. O! it is excellent

To have a giant’s strength, but it is tyrannous

To use it like a giant.

Lucio.

[Aside to Isab.] That’s well said. 109

Isab.

Could great men thunder

As Jove himself does, Jove would ne’er be quiet,

For every pelting, petty officer 112

Would use his heaven for thunder; nothing but thunder.

Merciful heaven!

Thou rather with thy sharp and sulphurous bolt

Split’st the unwedgeable and gnarled oak 116

Than the soft myrtle; but man, proud man,

Drest in a little brief authority,

Most ignorant of what he’s most assur’d,

His glassy essence, like an angry ape, 120

Plays such fantastic tricks before high heaven

As make the angels weep; who, with our spleens,

Would all themselves laugh mortal.

Lucio.

[Aside to Isab.] O, to him, to him, wench! He will relent: 124

He’s coming: I perceive’t.

Prov.

[Aside.] Pray heaven she win him!

Isab.

We cannot weigh our brother with ourself:

Great men may jest with saints; ’tis wit in them,

But, in the less foul profanation. 128

Lucio.

[Aside to Isab.] Thou’rt in the right, girl: more o’ that.

Isab.

That in the captain’s but a choleric word,

Which in the soldier is flat blasphemy.

Lucio.

[Aside to Isab.] Art advis’d o’ that? more on ’t. 132

Ang.

Why do you put these sayings upon me?

Isab.

Because authority, though it err like others,

Hath yet a kind of medicine in itself,

That skins the vice o’ the top. Go to your bosom;

Knock there, and ask your heart what it doth know 137

That’s like my brother’s fault: if it confess

A natural guiltiness such as is his,

Let it not sound a thought upon your tongue 140

Against my brother’s life.

Ang.

She speaks, and ’tis

Such sense that my sense breeds with it. Fare you well.

Isab.

Gentle my lord, turn back.

Ang.

I will bethink me. Come again to-morrow. 144

Isab.

Hark how I’ll bribe you. Good my lord, turn back.

Ang.

How! bribe me?

Isab.

Ay, with such gifts that heaven shall share with you.

Lucio.

[Aside to Isab.] You had marr’d all else. 148

Isab.

Not with fond sicles of the tested gold,

Or stones whose rates are either rich or poor

As fancy values them; but with true prayers

That shall be up at heaven and enter there 152

Ere sun-rise: prayers from preserved souls,

From fasting maids whose minds are dedicate

To nothing temporal.

Ang.

Well; come to me to-morrow.

Lucio.

[Aside to Isab.] Go to; ’tis well: away!

Isab.

Heaven keep your honour safe!

Ang.

[Aside.] Amen:

For I am that way going to temptation,

Where prayers cross.

Isab.

At what hour to-morrow

Shall I attend your lordship?

Ang.

At any time ’fore noon. 160

Isab.

Save your honour!

[Exeunt Isabella, Lucio, and Provost.

Ang.

From thee; even from thy virtue!

What’s this? what’s this? Is this her fault or mine?

The tempter or the tempted, who sins most?

Ha! 164

Not she; nor doth she tempt: but it is I,

That, lying by the violet in the sun,

Do as the carrion does, not as the flower,

Corrupt with virtuous season. Can it be 168

That modesty may more betray our sense

Than woman’s lightness? Having waste ground enough,

Shall we desire to raze the sanctuary,

And pitch our evils there? O, fie, fie, fie! 172

What dost thou, or what art thou, Angelo?

Dost thou desire her foully for those things

That make her good? O, let her brother live!

Thieves for their robbery have authority 176

When judges steal themselves. What! do I love her,

That I desire to hear her speak again,

And feast upon her eyes? What is’t I dream on?

O cunning enemy, that, to catch a saint, 180

With saints dost bait thy hook! Most dangerous

Is that temptation that doth goad us on

To sin in loving virtue: never could the strumpet,

With all her double vigour, art and nature, 184

Once stir my temper; but this virtuous maid

Subdues me quite. Ever till now,

When men were fond, I smil’d and wonder’d how.

[Exit.

Scene III.— A Room in a Prison.

Enter Duke, disguised as a friar, and Provost.

Duke.

Hail to you, provost! so I think you are.

Prov.

I am the provost. What’s your will, good friar?

Duke.

Bound by my charity and my bless’d order,

I come to visit the afflicted spirits 4

Here in the prison: do me the common right

To let me see them and to make me know

The nature of their crimes, that I may minister

To them accordingly. 8

Prov.

I would do more than that, if more were needful.

Look, here comes one: a gentlewoman of mine,

Who, falling in the flaws of her own youth,

Hath blister’d her report. She is with child, 12

And he that got it, sentenc’d; a young man

More fit to do another such offence,

Than die for this.

Enter Juliet.

Duke.

When must he die?

Prov.

As I do think, to-morrow.

[To Juliet.] I have provided for you: stay a while, 17

And you shall be conducted.

Duke.

Repent you, fair one, of the sin you carry?

Juliet.

I do, and bear the shame most patiently. 20

Duke.

I’ll teach you how you shall arraign your conscience,

And try your penitence, if it be sound,

Or hollowly put on.

Juliet.

I’ll gladly learn.

Duke.

Love you the man that wrong’d you?

Juliet.

Yes, as I love the woman that wrong’d him.

Duke.

So then it seems your most offenceful act

Was mutually committed?

Juliet.

Mutually.

Duke.

Then was your sin of heavier kind than his. 28

Juliet.

I do confess it, and repent it, father.

Duke.

’Tis meet so, daughter: but lest you do repent,

As that the sin hath brought you to this shame,

Which sorrow is always toward ourselves, not heaven, 32

Showing we would not spare heaven as we love it,

But as we stand in fear,—

Juliet.

I do repent me, as it is an evil,

And take the shame with joy.

Duke.

There rest. 36

Your partner, as I hear, must die to-morrow,

And I am going with instruction to him.

God’s grace go with you! Benedicite!

[Exit.

Juliet.

Must die to-morrow! O injurious love,

That respites me a life, whose very comfort 41

Is still a dying horror!

Prov.

’Tis pity of him.

[Exeunt.

Scene IV.— A Room in Angelo’s House.

Enter Angelo.

Ang.

When I would pray and think, I think and pray

To several subjects: heaven hath my empty words,

Whilst my invention, hearing not my tongue,

Anchors on Isabel: heaven in my mouth, 4

As if I did but only chew his name,

And in my heart the strong and swelling evil

Of my conception. The state, whereon I studied,

Is like a good thing, being often read, 8

Grown fear’d and tedious; yea, my gravity,

Wherein, let no man hear me, I take pride,

Could I with boot change for an idle plume,

Which the air beats for vain. O place! O form!

How often dost thou with thy case, thy habit, 13

Wrench awe from fools, and tie the wiser souls

To thy false seeming! Blood, thou art blood:

Let’s write good angel on the devil’s horn, 16

’Tis not the devil’s crest.

Enter a Servant.

How now! who’s there?

Serv.

One Isabel, a sister,

Desires access to you.

Ang.

Teach her the way.

[Exit Servant.

O heavens! 20

Why does my blood thus muster to my heart,

Making both it unable for itself,

And dispossessing all my other parts

Of necessary fitness? 24

So play the foolish throngs with one that swounds;

Come all to help him, and so stop the air

By which he should revive: and even so

The general, subject to a well-wish’d king, 28

Quit their own part, and in obsequious fondness

Crowd to his presence, where their untaught love

Must needs appear offence.

Enter Isabella.

How now, fair maid!

Isab.

I am come to know your pleasure. 32

Ang.

That you might know it, would much better please me,

Than to demand what ’tis. Your brother cannot live.

Isab.

Even so. Heaven keep your honour!

Ang.

Yet may he live awhile; and, it may be,

As long as you or I: yet he must die. 37

Isab.

Under your sentence?

Ang.

Yea.

Isab.

When, I beseech you? that in his reprieve, 40

Longer or shorter, he may be so fitted

That his soul sicken not.

Ang.

Ha! fie, these filthy vices! It were as good

To pardon him that hath from nature stolen 44

A man already made, as to remit

Their saucy sweetness that do coin heaven’s image

In stamps that are forbid: ’tis all as easy

Falsely to take away a life true made, 48

As to put metal in restrained means

To make a false one.

Isab.

’Tis set down so in heaven, but not in earth.

Ang.

Say you so? then I shall pose you quickly. 52

Which had you rather, that the most just law

Now took your brother’s life; or, to redeem him,

Give up your body to such sweet uncleanness

As she that he hath stain’d?

Isab.

Sir, believe this, 56

I had rather give my body than my soul.

Ang.

I talk not of your soul. Our compell’d sins

Stand more for number than for accompt.

Isab.

How say you?

Ang.

Nay, I’ll not warrant that; for I can speak 60

Against the thing I say. Answer to this:

I, now the voice of the recorded law,

Pronounce a sentence on your brother’s life:

Might there not be a charity in sin 64

To save this brother’s life?

Isab.

Please you to do’t,

I’ll take it as a peril to my soul;

It is no sin at all, but charity.

Ang.

Pleas’d you to do’t, at peril of your soul,

Were equal poise of sin and charity.

Isab.

That I do beg his life, if it be sin,

Heaven let me bear it! you granting of my suit,

If that be sin, I’ll make it my morn prayer 72

To have it added to the faults of mine,

And nothing of your answer.

Ang.

Nay, but hear me.

Your sense pursues not mine: either you are ignorant,

Or seem so craftily; and that’s not good. 76

Isab.

Let me be ignorant, and in nothing good,

But graciously to know I am no better.

Ang.

Thus wisdom wishes to appear most bright

When it doth tax itself; as these black masks 80

Proclaim an enshield beauty ten times louder

Than beauty could, display’d. But mark me;

To be received plain, I’ll speak more gross:

Your brother is to die. 84

Isab.

So.

Ang.

And his offence is so, as it appears

Accountant to the law upon that pain.

Isab.

True. 88

Ang.

Admit no other way to save his life,—

As I subscribe not that, nor any other,

But in the loss of question,—that you, his sister,

Finding yourself desir’d of such a person, 92

Whose credit with the judge, or own great place,

Could fetch your brother from the manacles

Of the all-building law; and that there were

No earthly mean to save him, but that either 96

You must lay down the treasures of your body

To this suppos’d, or else to let him suffer;

What would you do?

Isab.

As much for my poor brother, as myself:

That is, were I under the terms of death, 101

Th’ impression of keen whips I’d wear as rubies,

And strip myself to death, as to a bed

That, longing, have been sick for, ere I’d yield

My body up to shame.

Ang.

Then must your brother die.

Isab.

And ’twere the cheaper way:

Better it were a brother died at once,

Than that a sister, by redeeming him, 108

Should die for ever.

Ang.

Were not you then as cruel as the sentence

That you have slander’d so?

Isab.

Ignomy in ransom and free pardon 112

Are of two houses: lawful mercy

Is nothing kin to foul redemption.

Ang.

You seem’d of late to make the law a tyrant;

And rather prov’d the sliding of your brother 116

A merriment than a vice.

Isab.

O, pardon me, my lord! it oft falls out,

To have what we would have, we speak not what we mean.

I something do excuse the thing I hate, 120

For his advantage that I dearly love.

Ang.

We are all frail.

Isab.

Else let my brother die,

If not a feodary, but only he

Owe and succeed thy weakness. 124

Ang.

Nay, women are frail too.

Isab.

Ay, as the glasses where they view themselves,

Which are as easy broke as they make forms.

Women! Help heaven! men their creation mar

In profiting by them. Nay, call us ten times frail,

For we are soft as our complexions are,

And credulous to false prints.

Ang.

I think it well:

And from this testimony of your own sex,— 132

Since I suppose we are made to be no stronger

Than faults may shake our frames,—let me be bold;

I do arrest your words. Be that you are,

That is, a woman; if you be more, you’re none;

If you be one, as you are well express’d 137

By all external warrants, show it now,

By putting on the destin’d livery.

Isab.

I have no tongue but one: gentle my lord, 140

Let me entreat you speak the former language.

Ang.

Plainly conceive, I love you.

Isab.

My brother did love Juliet; and you tell me

That he shall die for’t. 144

Ang.

He shall not, Isabel, if you give me love.

Isab.

I know your virtue hath a licence in’t.

Which seems a little fouler than it is,

To pluck on others.

Ang.

Believe me, on mine honour,

My words express my purpose. 149

Isab.

Ha! little honour to be much believ’d,

And most pernicious purpose! Seeming, seeming!

I will proclaim thee, Angelo; look for’t: 152

Sign me a present pardon for my brother,

Or with an outstretch’d throat I’ll tell the world aloud

What man thou art.

Ang.

Who will believe thee, Isabel?

My unsoil’d name, the austereness of my life, 156

My vouch against you, and my place i’ the state,

Will so your accusation overweigh,

That you shall stifle in your own report

And smell of calumny. I have begun; 160

And now I give my sensual race the rein:

Fit thy consent to my sharp appetite;

Lay by all nicety and prolixious blushes,

That banish what they sue for; redeem thy brother 164

By yielding up thy body to my will,

Or else he must not only die the death,

But thy unkindness shall his death draw out

To lingering sufferance. Answer me to-morrow,

Or, by the affection that now guides me most,

I’ll prove a tyrant to him. As for you, 170

Say what you can, my false o’erweighs your true.

[Exit.

Isab.

To whom should I complain? Did I tell this, 172

Who would believe me? O perilous mouths!

That bear in them one and the self-same tongue,

Either of condemnation or approof,

Bidding the law make curt’sy to their will; 176

Hooking both right and wrong to th’ appetite,

To follow as it draws. I’ll to my brother:

Though he hath fallen by prompture of the blood,

Yet hath he in him such a mind of honour, 180

That, had he twenty heads to tender down

On twenty bloody blocks, he’d yield them up,

Before his sister should her body stoop

To such abhorr’d pollution. 184

Then, Isabel, live chaste, and, brother, die:

More than our brother is our chastity.

I’ll tell him yet of Angelo’s request,

And fit his mind to death, for his soul’s rest. 188

[Exit.

ACT III.

Scene I.— A Room in the Prison.

Enter Duke, as a friar, Claudio, and Provost.

Duke.

So then you hope of pardon from Lord Angelo?

Claud.

The miserable have no other medicine

But only hope:

I have hope to live, and am prepar’d to die. 4

Duke.

Be absolute for death; either death or life

Shall thereby be the sweeter. Reason thus with life:

If I do lose thee, I do lose a thing

That none but fools would keep: a breath thou art, 8

Servile to all the skyey influences,

That dost this habitation, where thou keep’st,

Hourly afflict. Merely, thou art death’s fool;

For him thou labour’st by thy flight to shun, 12

And yet run’st toward him still. Thou art not noble:

For all th’ accommodations that thou bear’st

Are nurs’d by baseness. Thou art by no means valiant;

For thou dost fear the soft and tender fork 16

Of a poor worm. Thy best of rest is sleep,

And that thou oft provok’st; yet grossly fear’st

Thy death, which is no more. Thou art not thyself;

For thou exist’st on many a thousand grains 20

That issue out of dust. Happy thou art not;

For what thou hast not, still thou striv’st to get,

And what thou hast, forget’st. Thou art not certain;

For thy complexion shifts to strange effects, 24

After the moon. If thou art rich, thou’rt poor;

For, like an ass whose back with ingots bows,

Thou bear’st thy heavy riches but a journey,

And death unloads thee. Friend hast thou none;

For thine own bowels, which do call thee sire,

The mere effusion of thy proper loins,

Do curse the gout, serpigo, and the rheum,

For ending thee no sooner. Thou hast nor youth nor age; 32

But, as it were, an after-dinner’s sleep,

Dreaming on both; for all thy blessed youth

Becomes as aged, and doth beg the alms

Of palsied eld; and when thou art old and rich,

Thou hast neither heat, affection, limb, nor beauty, 37

To make thy riches pleasant. What’s yet in this

That bears the name of life? Yet in this life

Lie hid moe thousand deaths: yet death we fear,

That makes these odds all even.

Claud.

I humbly thank you.

To sue to live, I find I seek to die,

And, seeking death, find life: let it come on.

Isab.

[Within.] What ho! Peace here; grace and good company! 44

Prov.

Who’s there? come in: the wish deserves a welcome.

Duke.

Dear sir, ere long I’ll visit you again.

Claud.

Most holy sir, I thank you. 47

Enter Isabella.

Is.

My business is a word or two with Claudio.

Prov.

And very welcome. Look, signior; here’s your sister.

Duke.

Provost, a word with you.

Prov.

As many as you please.

Duke.

Bring me to hear them speak, where I may be conceal’d. 52

[Exeunt Duke and Provost.

Claud.

Now, sister, what’s the comfort?

Isab.

Why, as all comforts are; most good, most good indeed.

Lord Angelo, having affairs to heaven,

Intends you for his swift ambassador, 56

Where you shall be an everlasting leiger:

Therefore, your best appointment make with speed;

To-morrow you set on.

Claud.

Is there no remedy?

Isab.

None, but such remedy, as to save a head 60

To cleave a heart in twain.

Claud.

But is there any?

Isab.

Yes, brother, you may live:

There is a devilish mercy in the judge,

If you’ll implore it, that will free your life, 64

But fetter you till death.

Claud.

Perpetual durance?

Isab.

Ay, just; perpetual durance, a restraint,

Though all the world’s vastidity you had,

To a determin’d scope.

Claud.

But in what nature? 68

Isab.

In such a one as, you consenting to’t,

Would bark your honour from that trunk you bear,

And leave you naked.

Claud.

Let me know the point.

Isab.

O, I do fear thee, Claudio; and I quake,

Lest thou a feverous life shouldst entertain,

And six or seven winters more respect

Than a perpetual honour. Dar’st thou die?

The sense of death is most in apprehension, 76

And the poor beetle, that we tread upon,

In corporal sufferance finds a pang as great

As when a giant dies.

Claud.

Why give you me this shame?

Think you I can a resolution fetch 80

From flowery tenderness? If I must die,

I will encounter darkness as a bride,

And hug it in mine arms.

Isab.

There spake my brother: there my father’s grave 84

Did utter forth a voice. Yes, thou must die:

Thou art too noble to conserve a life

In base appliances. This outward-sainted deputy,

Whose settled visage and deliberate word 88

Nips youth i’ the head, and follies doth enmew

As falcon doth the fowl, is yet a devil;

His filth within being cast, he would appear

A pond as deep as hell.

Claud.

The prenzie Angelo? 92

Isab.

O, ’tis the cunning livery of hell,

The damned’st body to invest and cover

In prenzie guards! Dost thou think, Claudio?

If I would yield him my virginity, 96

Thou mightst be freed.

Claud.

O heavens! it cannot be.

Isab.

Yes, he would give’t thee, from this rank offence,

So to offend him still. This night’s the time

That I should do what I abhor to name, 100

Or else thou diest to-morrow.

Claud.

Thou shalt not do’t.

Isab.

O! were it but my life,

I’d throw it down for your deliverance

As frankly as a pin.

Claud.

Thanks, dear Isabel. 104

Isab.

Be ready, Claudio, for your death to-morrow.

Claud.

Yes. Has he affections in him,

That thus can make him bite the law by the nose,

When he would force it? Sure, it is no sin; 108

Or of the deadly seven it is the least.

Isab.

Which is the least?

Claud.

If it were damnable, he being so wise,

Why would he for the momentary trick 112

Be perdurably fin’d? O Isabel!

Isab.

What says my brother?

Claud.

Death is a fearful thing.

Isab.

And shamed life a hateful.

Claud.

Ay, but to die, and go we know not where; 116

To lie in cold obstruction and to rot;

This sensible warm motion to become

A kneaded clod; and the delighted spirit

To bathe in fiery floods, or to reside 120

In thrilling region of thick-ribbed ice;

To be imprison’d in the viewless winds,

And blown with restless violence round about

The pendant world; or to be worse than worst

Of those that lawless and incertain thoughts

Imagine howling: ’tis too horrible!

The weariest and most loathed worldly life

That age, ache, penury and imprisonment 128

Can lay on nature is a paradise

To what we fear of death.

Isab.

Alas! alas!

Claud.

Sweet sister, let me live:

What sin you do to save a brother’s life, 132

Nature dispenses with the deed so far

That it becomes a virtue.

Isab.

O you beast!

O faithless coward! O dishonest wretch!

Wilt thou be made a man out of my vice? 136

Is’t not a kind of incest, to take life

From thine own sister’s shame? What should I think?

Heaven shield my mother play’d my father fair;

For such a warped slip of wilderness 140

Ne’er issu’d from his blood. Take my defiance;

Die, perish! Might but my bending down

Reprieve thee from thy fate, it should proceed.

I’ll pray a thousand prayers for thy death, 144

No word to save thee.

Claud.

Nay, hear me, Isabel.

Isab.

O, fie, fie, fie!

Thy sin’s not accidental, but a trade.

Mercy to thee would prove itself a bawd: 148

’Tis best that thou diest quickly.

[Going.

Claud.

O hear me, Isabella.

Re-enter Duke.

Duke.

Vouchsafe a word, young sister, but one word.

Isab.

What is your will? 151

Duke.

Might you dispense with your leisure, I would by and by have some speech with you: the satisfaction I would require is likewise your own benefit.

Isab.

I have no superfluous leisure: my stay must be stolen out of other affairs; but I will attend you a while. 158

Duke.

[Aside to Claudio.] Son, I have overheard what hath past between you and your sister. Angelo had never the purpose to corrupt her; only he hath made an assay of her virtue to practise his judgment with the disposition of natures. She, having the truth of honour in her, hath made him that gracious denial which he is most glad to receive: I am confessor to Angelo, and I know this to be true; therefore prepare yourself to death. Do not satisfy your resolution with hopes that are fallible: to-morrow you must die; go to your knees and make ready. 170

Claud.

Let me ask my sister pardon. I am so out of love with life that I will sue to be rid of it.

Duke.

Hold you there: farewell. 174

[Exit Claudio.

Re-enter Provost.

Provost, a word with you.

Prov.

What’s your will, father?

Duke.

That now you are come, you will be gone. Leave me awhile with the maid: my mind promises with my habit no loss shall touch her by my company. 180

Prov.

In good time.

[Exit.

Duke.

The hand that hath made you fair hath made you good: the goodness that is cheap in beauty makes beauty brief in goodness; but grace, being the soul of your complexion, shall keep the body of it ever fair. The assault that Angelo hath made to you, fortune hath conveyed to my understanding; and, but that frailty hath examples for his falling, I should wonder at Angelo. How would you do to content this substitute, and to save your brother? 192

Isab.

I am now going to resolve him; I had rather my brother die by the law than my son should be unlawfully born. But O, how much is the good duke deceived in Angelo! If ever he return and I can speak to him. I will open my lips in vain, or discover his government. 198

Duke.

That shall not be much amiss: yet, as the matter now stands, he will avoid your accusation; ‘he made trial of you only.’ Therefore, fasten your ear on my advisings: to the love I have in doing good a remedy presents itself. I do make myself believe that you may most uprighteously do a poor wronged lady a merited benefit, redeem your brother from the angry law, do no stain to your own gracious person, and much please the absent duke, if peradventure he shall ever return to have hearing of this business. 210

Isab.

Let me hear you speak further. I have spirit to do anything that appears not foul in the truth of my spirit.

Duke.

Virtue is bold, and goodness never fearful. Have you not heard speak of Mariana, the sister of Frederick, the great soldier who miscarried at sea?

Isab.

I have heard of the lady, and good words went with her name. 219

Duke.

She should this Angelo have married; was affianced to her by oath, and the nuptial appointed: between which time of the contract, and limit of the solemnity, her brother Frederick was wracked at sea, having in that perished vessel the dowry of his sister. But mark how heavily this befell to the poor gentlewoman: there she lost a noble and renowned brother, in his love toward her ever most kind and natural; with him the portion and sinew of her fortune, her marriage-dowry with both, her combinate husband, this well-seeming Angelo. 231

Isab.

Can this be so? Did Angelo so leave her?

Duke.

Left her in her tears, and dried not one of them with his comfort; swallowed his vows whole, pretending in her discoveries of dishonour: in few, bestowed her on her own lamentation, which she yet wears for his sake; and he, a marble to her tears, is washed with them, but relents not. 239

Isab.

What a merit were it in death to take this poor maid from the world! What corruption in this life, that it will let this man live! But how out of this can she avail? 243

Duke.

It is a rupture that you may easily heal; and the cure of it not only saves your brother, but keeps you from dishonour in doing it.

Isab.

Show me how, good father. 248

Duke.

This forenamed maid hath yet in her the continuance of her first affection: his unjust unkindness, that in all reason should have quenched her love, hath, like an impediment in the current, made it more violent and unruly. Go you to Angelo: answer his requiring with a plausible obedience: agree with his demands to the point; only refer yourself to this advantage, first, that your stay with him may not be long, that the time may have all shadow and silence in it, and the place answer to convenience. This being granted in course, and now follows all, we shall advise this wronged maid to stead up your appointment, go in your place; if the encounter acknowledge itself hereafter, it may compel him to her recompense; and here by this is your brother saved, your honour untainted, the poor Mariana advantaged, and the corrupt deputy scaled. The maid will I frame and make fit for his attempt. If you think well to carry this, as you may, the doubleness of the benefit defends the deceit from reproof. What think you of it? 271

Isab.

The image of it gives me content already, and I trust it will grow to a most prosperous perfection.

Duke.

It lies much in your holding up. Haste you speedily to Angelo: if for this night he entreat you to his bed, give him promise of satisfaction. I will presently to St. Luke’s; there, at the moated grange, resides this dejected Mariana: at that place call upon me, and dispatch with Angelo, that it may be quickly. 281

Isab.

I thank you for this comfort. Fare you well, good father.

[Exeunt.

Scene II.— The Street before the Prison.

Enter Duke, as a friar; to him Elbow, Pompey, and Officers.

Elb.

Nay, if there be no remedy for it, but that you will needs buy and sell men and women like beasts, we shall have all the world drink brown and white bastard. 4

Duke.

O heavens! what stuff is here?

Pom.

’Twas never merry world, since, of two usuries, the merriest was put down, and the worser allowed by order of law a furred gown to keep him warm; and furred with fox and lamb skins too, to signify that craft, being richer than innocency, stands for the facing.

Elb.

Come your way, sir. Bless you, good father friar. 13

Duke.

And you, good brother father. What offence hath this man made you, sir?

Elb.

Marry, sir, he hath offended the law: and, sir, we take him to be a thief too, sir; for we have found upon him, sir, a strange picklock, which we have sent to the deputy.

Duke.

Fie, sirrah: a bawd, a wicked bawd! 20

The evil that thou causest to be done,

That is thy means to live. Do thou but think

What ’tis to cram a maw or clothe a back

From such a filthy vice: say to thyself, 24

From their abominable and beastly touches

I drink, I eat, array myself, and live.

Canst thou believe thy living is a life,

So stinkingly depending? Go mend, go mend. 28

Pom.

Indeed, it does stink in some sort, sir; but yet, sir, I would prove—

Duke.

Nay, if the devil have given thee proofs for sin,

Thou wilt prove his. Take him to prison, officer; 32

Correction and instruction must both work

Ere this rude beast will profit.

Elb.

He must before the deputy, sir; he has given him warning. The deputy cannot abide a whoremaster: if he be a whoremonger, and comes before him, he were as good go a mile on his errand.

Duke.

That we were all, as some would seem to be, 40

From our faults, as faults from seeming, free!

Elb.

His neck will come to your waist,—a cord, sir.

Pom.

I spy comfort: I cry, bail. Here’s a gentleman and a friend of mine. 45

Enter Lucio.

Lucio.

How now, noble Pompey! What, at the wheels of Cæsar? Art thou led in triumph? What, is there none of Pygmalion’s images, newly made woman, to he had now, for putting the hand in the pocket and extracting it clutched? What reply? ha? What say’st thou to this tune, matter and method? Is’t not drowned i’ the last rain, ha? What sayest thou Trot? Is the world as it was, man? Which is the way? Is it sad, and few words, or how? The trick of it? 56

Duke.

Still thus, and thus, still worse!

Lucio.

How doth my dear morsel, thy mistress? Procures she still, ha?

Pom.

Troth, sir, she hath eaten up all her beef, and she is herself in the tub. 61

Lucio.

Why, ’tis good; it is the right of it; it must be so: ever your fresh whore and your powdered bawd: an unshunned consequence; it must be so. Art going to prison, Pompey?

Pom.

Yes, faith, sir. 66

Lucio.

Why, ’tis not amiss, Pompey. Farewell. Go, say I sent thee thither. For debt, Pompey? or how?

Elb.

For being a bawd, for being a bawd. 70

Lucio.

Well, then, imprison him. If imprisonment be the due of a bawd, why, ’tis his right: bawd is he, doubtless, and of antiquity too; bawd-born. Farewell, good Pompey. Commend me to the prison, Pompey. You will turn good husband now, Pompey; you will keep the house. 77

Pom.

I hope, sir, your good worship will be my bail.

Lucio.

No, indeed will I not, Pompey; it is not the wear. I will pray, Pompey, to increase your bondage: if you take it not patiently, why, your mettle is the more. Adieu, trusty Pompey. Bless you, friar. 84

Duke.

And you.

Lucio.

Does Bridget paint still, Pompey, ha?

Elb.

Come your ways, sir; come.

Pom.

You will not bail me then, sir? 88

Lucio.

Then, Pompey, nor now. What news abroad, friar? What news?

Elb.

Come your ways, sir; come.

Lucio.

Go to kennel, Pompey; go. 92

[Exeunt Elbow, Pompey and Officers.

What news, friar, of the duke?

Duke.

I know none. Can you tell me of any?

Lucio.

Some say he is with the Emperor of Russia; other some, he is in Rome: but where is he, think you? 97

Duke.

I know not where; but wheresoever, I wish him well.

Lucio.

It was a mad fantastical trick of him to steal from the state, and usurp the beggary he was never born to. Lord Angelo dukes it well in his absence; he puts transgression to’t.

Duke.

He does well in’t. 104

Lucio.

A little more lenity to lechery would do no harm in him: something too crabbed that way, friar.

Duke.