Thomas Hill Green, Lecture “On the Different Senses of ‘Freedom’ as Applied to Will and the Moral Progress of Man” (1879)

|

|

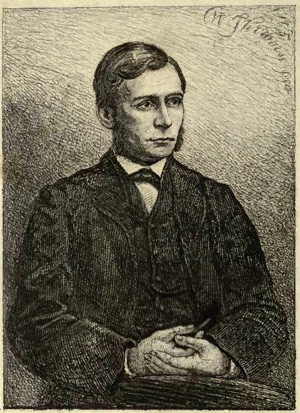

| Thomas Hill Green (1836-1882) |

Source

Thomas Hill Green, Lecture “On the Different Senses of ‘Freedom’ as Applied to Will and the Moral Progress of Man” (1879), in

Lectures On The Principles Of Political Obligation. Reprinted From Green's Philosophical Works, Vol II. With Preface By Bernard Bosanquet. New Impression (London: Longmans, Green And Co., 1911), pp. 2-27.

See the facs. PDF of the entire volume of Works, Vol. II or just the Lecture.

Table of Contents

ON THE DIFFERENT SENSES OF 'FREEDOM' AS APPLIED TO WILL AND TO THE MORAL PROGRESS OF MAN.

- 1. In one sense (as being search for self-satisfaction) all will is free; in another (as the satisfaction sought is or is not real) it may or may not be free

- 2. As applied to the inner life 'freedom' always implies a metaphor. Senses of this metaphor in Plato, the Stoics, St. Paul

- 3. St. Paul and Kant. It would seem that with Kant 'freedom' means merely consciousness of the possibility of it, ('knowledge of sin')

- 4. Hegel's conception of freedom as objectively realised in the state

- 5. It is true in so far as society does supply to the individual concrete interests which tend to satisfy the desire for perfection

- 6. Though (like the corresponding conception in St. Paul) it is not and could not be realised in any actual human society

- 7. In all these uses 'freedom' means, not mere self-determination or acting on preference, but a particular kind of this

- 8. The extension of the term from the outer to the inner relations of life, though a natural result of reflection, is apt to be misleading

- 9. Thus the question, Is a man free? which may be properly asked in regard to his actions, cannot be asked in the same sense in regard to his will

- 10. The failure to see this has led to the errors (1) of regarding motive as something apart from and acting on will, (2) of regarding will as independent of motive

- 11. Thus the fact that a man, being what he is, must act in a certain way, is construed into the negation of freedom

- 12. And to escape this negation recourse is had to the notion of an unmotived will, which is really no will at all

- 13. The truth is that the will is the man, and that the will cannot be rightly spoken of as 'acting on' its objects or vice versa, because they are neither anything without the other

- 14. If however the question be persisted in, Has a man power over his will? the answer must be both 'yes' and 'no'

- 15. 'Freedom' has been taken above (as by English psychologists generally) as applying to will, whatever the character of the object willed

- 16. If taken (as by the Stoics, St. Paul, Kant (generally), and Hegel) as applying only to good will, it must still be recognised that this particular sense implies the generic

- 17. Whatever the propriety of the term in the particular sense, both 'juristic' and 'spiritual' freedom spring from the same self-asserting principle in man

- 18. And though the former is only the beginning of full freedom, this identity of source will always justify the use of the word in the latter sense

- 19. But does not the conception of 'freedom' as = the moral ideal imply an untenable distinction like that of Kant between the 'pure' and 'empirical' ego?

- 20. The 'pure' and 'empirical' ego are one ego, regarded (1) in its possibility, (2) as at any given time it actually is

- 21. In man the self-realising principle is never realised; i.e. the objects of reason and will only tend to coincide

- 22. So far as they do coincide, man may be said to be 'free' and his will to be 'autonomous'

- 23. The growing organisation of human life provides a medium for the embodiment, and disciplines the natural impulses for the reception, of the idea of perfection

- 24. The reconciliation of reason and will takes place as the individual more and more finds his own self-satisfaction in meeting the requirements of established morality

- 25. Until these come to be entirely superseded by the desire of perfection for its own sake, and his will becomes really free.

ON THE DIFFERENT SENSES OF 'FREEDOM' AS APPLIED TO WILL AND TO THE MORAL PROGRESS OF MAN.

Note of the Editor,↩

The lectures from which the following extract is taken were delivered in the beginning of 1879, in continuation of the course in which the discussion of Kant's moral theory occurred. The portions here printed are those which were not embodied, at any rate in the same form, in the Prolegomena to Ethics. See Prolegomena to Ethics, Book ii. ch. i. sec. 100, Editor's note.

ON THE DIFFERENT SENSES OF 'FREEDOM' AS APPLIED TO WILL AND TO THE MORAL PROGRESS OF MAN.↩

1. Since in all willing a man is his own object, the will is always free. Or, more properly, a man in willing is necessarily free, since willing constitutes freedom, [1] and 'free will' is the pleonasm 'free freedom.' But while it is important to insist upon this, it is also to be remembered that the nature of the freedom really differs—the freedom means quite different things—according to the nature of the object which the man makes his own, or with which he identifies himself. It is one thing when the object in which self-satisfaction is sought is such as to prevent that self-satisfaction being found, because interfering with the realisation of the seeker's possibilities or his progress towards perfection: it is another thing when it contributes to this end. In the former case the man is a free agent in the act, because through his identification of himself with a certain desired object—through his adoption of it as his good—he makes the motive which determines the act, and is accordingly conscious of himself as its author. But in another sense he is not free, because the objects to which his actions are directed are objects in which, according to the law of his being, satisfaction of himself is not to be found. His will to arrive at self-satisfaction not being adjusted to the law which determines where this self-satisfaction is to be found, he may be considered in the condition of a bondsman who is carrying out the will of another, not his own. From this bondage he emerges into real freedom, not by overcoming the law of his being, not by getting the better of its necessity,—every fancied effort to do so is but a new exhibition of its necessity,—but by making its fulfilment the object of his will; by seeking the satisfaction of himself in objects in which he believes it should be found, and seeking it in them because he believes it should be found in them. For the objects so sought, however various otherwise, have the common characteristic that, because they are sought in such a spirit, in them self-satisfaction is to be found; not the satisfaction of this or that desire, or of each particular desire, but that satisfaction, otherwise called peace or blessedness, which consists in the whole man having found his object; which indeed we never experience in its fulness, which we only approach to fall away from it again, but of which we know enough to be sure that we only fail to attain it because we fail to seek it in the fulfilment of the law of our being, because we have not brought ourselves to 'gladly do and suffer what we must.'

To the above statement several objections may be made. They will chiefly turn on two points; (a) the use made of the term 'freedom'; (b) the view that a man is subject to a law of his being, in virtue of which he at once seeks self-satisfaction, and is prevented from finding it in the objects which he actually desires, and in which he ordinarily seeks it.

[1] In that sense in which 'freedom' expresses a state of the soul, as distinct from a civil relation.

2. As to the sense given to 'freedom,' it must of course be admitted that every usage of the term to express anything but a social and political relation of one man to others involves a metaphor. Even in the original application its sense is by no means fixed. It always implies indeed some exemption from compulsion by others, but the extent and conditions of this exemption, as enjoyed by the 'freeman' in different states of society, are very various. As soon as the term 'freedom' comes to be applied to anything else than an established relation between a man and other men, its sense fluctuates much more. Reflecting on their consciousness, on their 'inner life' (i.e. their life as viewed from within), men apply to it the terms with which they are familiar as expressing their relations to each other. In virtue of that power of self-distinction and self-objectification, which he expresses whenever he says 'I,' a man can set over against himself his whole nature or any of its elements, and apply to the relation thus established in thought a term borrowed from relations of outward life. Hence, as in Plato, the terms 'freedom' and 'bondage' may be used to express a relation between the man on the one side, as distinguishing himself from all impulses that do not tend to his true good, and those impulses on the other. He is a 'slave' when they are masters of him, 'free' when master of them. The metaphor in this form was made further use of by the Stoics, and carried on into the doctrines of the Christian Church. Since there is no kind of impulse or interest which a man cannot so distinguish from himself as to present it as an alien power, of which the influence on him is bondage, the particular application of the metaphor is quite arbitrary. It may come to be thought that the only freedom is to be found in a life of absolute detachment from all interests; a life in which the pure ego converses solely with itself or with a God, who is the same abstraction under another name. This is a view into which both saints and philosophers have been apt to fall. It means practically, so far as it means anything, absorption in some one interest with which the man identifies himself in exclusion of all other interests, which he sets over against himself as an influence to be kept aloof.

With St. Paul the application of the metaphor has a special character of its own. With him 'freedom' is specially freedom from the law, from ordinances, from the fear which these inspire,—a freedom which is attained through the communication of what he calls the 'spirit of adoption' or 'son-ship.' The law, merely as law or as an external command, is a source of bondage in a double sense. Presenting to man a command which yet it does not give him power to obey, it destroys the freedom of the life in which he does what he likes without recognising any reason why he should not (the state of which St. Paul says 'I was alive without the law once'); it thus puts him in bondage to fear, and at the same time, exciting a wish for obedience to itself which other desires (φρόνημα σαρκός) [1] prevent from being accomplished, it makes the man feel the bondage of the flesh. 'What I will, that I do not'; there is a power, the flesh, of which I am the slave, and which prevents me from performing my will to obey the law. Freedom (also called 'peace,' and 'reconciliation') comes when the spirit expressed in the law (for the law is itself 'spiritual' according to St. Paul; the 'flesh' through which it is weak is mine, not the law's) becomes the principle of action in the man. To the man thus delivered, as St. Paul conceives him, we might almost apply phraseology like Kant's. 'He is free because conscious of himself as the author of the law which he obeys.' He is no longer a servant, but a son. He is conscious of union with God, whose will as an external law he before sought in vain to obey, but whose 'righteousness is fulfilled' in him now that he 'walks after the spirit.' What was before 'a law of sin and death' is now a 'law of the spirit of life.' (See Epistle to the Romans, viii.)

[1] [Greek φρόνημα σαρκός (phronima sarkos) = carnal mind (KJV) Tr]

3. But though there is a point of connection between St. Paul's conception of freedom and bondage and that of Kant, which renders the above phrase applicable in a certain sense to the 'spiritual man' of St. Paul, yet the two conceptions are very different. Moral bondage with Kant, as with Plato and the Stoics, is bondage to the flesh. The heteronomy of the will is its submission to the impulse of pleasure-seeking, as that of which man is not in respect of his reason the author, but which belongs to him as a merely natural being. A state of bondage to law, as such, he does not contemplate. It might even be urged that Kant's 'freedom' or 'autonomy' of the will, in the only sense in which he supposed it attainable by man, is very much like the state described by St. Paul as that from which the communication of the spirit brings deliverance,—the state in which 'I delight in the law of God after the inward man, but find another law in my members warring with the law of my reason and bringing me into captivity to the law of sin in my members.' For Kant seems to hold that the will is actually 'autonomous,' i.e. determined by pure consciousness of what should be, only in rare acts of the best man. He argues rather for our being conscious of the possibility of such determination, as evidence of an ideal of what the good will is, than for the fact that anyone is actually so determined. And every determination of the will that does not proceed from pure consciousness of what should be he ascribes to the pleasure-seeking which belongs to man merely as a 'Natur-wesen,' or as St. Paul might say 'to the law of sin in his members.' What, it may be asked, is such 'freedom,' or rather such consciousness of the possibility of freedom, worth? May we not apply to it St. Paul's words, 'By the law is the knowledge of sin'? The practical result to the individual of that consciousness of the possibility of freedom which is all that the autonomy of will, as really attainable by man, according to Kant's view, amounts to, is to make him aware of the heteronomy of his will, of its bondage to motives of which reason is not the author.

4. This is an objection which many of Kant's statements of his doctrine, at any rate, fairly challenge. It was chiefly because he seemed to make freedom [1] an unrealised and unrealisable state, that his moral doctrine was found unsatisfactory by Hegel. Hegel holds that freedom, as the condition in which the will is determined by an object adequate to itself, or by an object which itself as reason constitutes, is realised in the state. He thinks of the state in a way not familiar to Englishmen, a way not unlike that in which Greek philosophers thought of the πόλις, [2] as a society governed by laws and institutions and established customs which secure the common good of the members of the society—enable them to make the best of themselves—and are recognised as doing so. Such a state is 'objective freedom'; freedom is realised in it because in it the reason, the self-determining principle operating in man as his will, has found a perfect expression for itself (as an artist may be considered to express himself in a perfect work of art); and the man who is determined by the objects which the well-ordered state presents to him is determined by that which is the perfect expression of his reason, and is thus free.

[1] In the sense of 'autonomy of rational will,' or determination by an object which reason constitutes, as distinct from determination by an object which the man makes his own; this latter determination Kant would have recognised as characteristic of every human act, properly so called.

[2] [Greek πόλις (polis) = city-state Tr.]

5. There is, no doubt, truth in this view. I have already tried to show [1] how the self-distinguishing and self-seeking consciousness of man, acting in and upon those human wants and ties and affections which in their proper human character have as little reality apart from it as it apart from them, gives rise to a system of social relations, with laws, customs, and institutions corresponding; and how in this system the individual's consciousness of the absolutely desirable, of something that should be, of an ideal to be realised in his life, finds a content or object which has been constituted or brought into being by that consciousness itself as working through generations of men; how interests are thus supplied to the man of a more concrete kind than the interest in fulfilment of a universally binding law because universally binding, but which yet are the product of reason, and in satisfying which he is conscious of attaining a true good, a good contributory to the perfection of himself and his kind. There is thus something in all forms of society that tends to the freedom [2] at least of some favoured individuals, because it tends to actualise in them the possibility of that determination by objects conceived as desirable in distinction from objects momentarily desired, which is determination by reason. [3] To put it otherwise, the effect of his social relations on a man thus favoured is that, whereas in all willing the individual seeks to satisfy himself, this man seeks to satisfy himself, not as one who feels this or that desire, but as one who conceives, whose nature demands, a permanent good. So far as it is thus in respect of his rational nature that he makes himself an object to himself, his will is autonomous. This was the good which the ideal πόλις, as conceived by the Greek philosophers, secured for the true πολίτης, the man who, entering into the idea of the πόλις, was equally qualified ἄρχειν καὶ ἄρχεσθαι. [4] No doubt in the actual Greek πόλις there was some tendency in this direction, some tendency to rationalise and moralise the citizen. Without the real tendency the ideal possibility would not have suggested itself. And in more primitive forms of society, so far as they were based on family or tribal relations, we can see that the same tendency must have been at work, just as in modern life the consciousness of his position as member or head of a family, wherever it exists, necessarily does something to moralise a man. In modern Christendom, with the extension of citizenship, the security of family life to all men (so far as law and police can secure it), the establishment in various forms of Christian fellowship of which the moralising functions grow as those of the magistrate diminish, the number of individuals whom society awakens to interests in objects contributory to human perfection tends to increase. So far the modern state, in that full sense in which Hegel uses the term (as including all the agencies for common good of a law-abiding people), does contribute to the realisation of freedom, if by freedom we understand the autonomy of the will or its determination by rational objects, objects which help to satisfy the demand of reason, the effort after self-perfection.

[1] [In a previous course of lectures. See Prolegomena to Ethics, III. iii. RLN]

[2] In the sense of 'autonomy of will.'

[3] [This last clause is queried in the MS. RLN]

[4] [Greek πόλις (polis) = city-state, πολίτης (polites) = citizen, ἄρχειν καὶ ἄρχεσθαι (archein kai archesthai) = to rule and to be ruled Tr]

6. On the other hand, it would seem that we cannot significantly speak of freedom except with reference to individual persons; that only in them can freedom be realised; that therefore the realisation of freedom in the state can only mean the attainment of freedom by individuals through influences which the state (in the wide sense spoken of) supplies,—'freedom' here, as before, meaning not the mere self-determination which renders us responsible, but determination by reason, 'autonomy of the will'; and that under the best conditions of any society that has ever been such realisation of freedom is most imperfect. To an Athenian slave, who might be used to gratify a master's lust, it would have been a mockery to speak of the state as a realisation of freedom; and perhaps it would not be much less so to speak of it as such to an untaught and under-fed denizen of a London yard with gin-shops on the right hand and on the left. What Hegel says of the state in this respect seems as hard to square with facts as what St. Paul says of the Christian whom the manifestation of Christ has transferred from bondage into 'the glorious liberty of the sons of God.' In both cases the difference between the ideal and the actual seems to be ignored, and tendencies seem to be spoken of as if they were accomplished facts. It is noticeable that by uncritical readers of St. Paul the account of himself as under the law (in Romans vii.), with the 'law of sin in his members warring against the law of his reason,' is taken as applicable to the regenerate Christian, though evidently St. Paul meant it as a description of the state from which the Gospel, the 'manifestation of the Son of God in the likeness of sinful flesh,' set him free. They are driven to this interpretation because, though they can understand St. Paul's account of his deliverance as an account of a deliverance achieved for them but not in them, or as an assurance of what is to be, they cannot adjust it to the actual experience of the Christian life. In the same way Hegel's account of freedom as realised in the state does not seem to correspond to the facts of society as it is, or even as, under the unalterable conditions of human nature, it ever could be; though undoubtedly there is a work of moral liberation, which society, through its various agencies, is constantly carrying on for the individual.

7. Meanwhile it must be borne in mind that in all these different views as to the manner and degree in which freedom is to be attained, 'freedom' does not mean that the man or will is undetermined, nor yet does it mean mere self-determination, which (unless denied altogether, as by those who take the strictly naturalistic view of human action) must be ascribed equally to the man whose will is heteronomous or vicious, and to him whose will is autonomous; equally to the man who recognises the authority of law in what St. Paul would count the condition of a bondman, and to him who fulfils the righteousness of the law in the spirit of adoption. It means a particular kind of self-determination; the state of the man who lives indeed for himself, but for the fulfilment of himself as a 'giver of law universal' (Kant); who lives for himself, but only according to the true idea of himself, according to the law of his being, 'according to nature' (the Stoics); who is so taken up into God, to whom God so gives the spirit, that there is no constraint in his obedience to the divine will (St. Paul); whose interests, as a loyal citizen, are those of a well-ordered state in which practical reason expresses itself (Hegel). Now none of these modes of self-determination is at all implied in 'freedom' according to the primary meaning of the term, as expressing that relation between one man and others in which he is secured from compulsion. All that is so implied is that a man should have power to do what he wills or prefers. No reference is made to the nature of the will or preference, of the object willed or preferred; whereas according to the usage of 'freedom' in the doctrines we have just been considering, it is not constituted by the mere fact of acting upon preference, but depends wholly on the nature of the preference, upon the kind of object willed or preferred.

8. If it were ever reasonable to wish that the usage of words had been other than it has been (any more than that the processes of nature were other than they are), one might be inclined to wish that the term 'freedom' had been confined to the juristic sense of the power to 'do what one wills': for the extension of its meaning seems to have caused much controversy and confusion. But, after all, this extension does but represent various stages of reflection upon the self-distinguishing, self-seeking, self-asserting principle, of which the establishment of freedom, as a relation between man and man, is the expression. The reflecting man is not content with the first announcement which analysis makes as to the inward condition of the free man, viz. that he can do what he likes, that he has the power of acting according to his will or preference. In virtue of the same principle which has led him to assert himself against others, and thus to cause there to be such a thing as (outward) freedom, he distinguishes himself from his preference, and asks how he is related to it, whether he determines it or how it is determined. Is he free to will, as he is free to act; or, as the act is determined by the preference, is the preference determined by something else? Thus Locke (Essay, II. 21) begins with deciding that freedom means power to do or forbear from doing any particular act upon preference, and that, since the will is merely the power of preference, the question whether the will is free is an unmeaning one (equivalent to the question whether one power has another power); that thus the only proper question is whether a man (not his will) is free, which must be answered affirmatively so far as he has the power to do or forbear, as above. But he recognises the propriety of the question whether a man is free to will as well as to act. He cannot refuse to carry back the analysis of what is involved in a man's action beyond the preference of one possible action to another, and to inquire what is implied in the preference. It is when this latter question is raised, that language which is appropriate enough in a definition of outward or juristic freedom becomes misleading. It having been decided that the man civilly free has power over his actions, to do or forbear according to preference, it is asked whether he has also power to prefer.

9. But while it is proper to ask whether in any particular case a man has power over his actions, because his nerves and limbs and muscles may be acted upon by another person or a force which is not he or his, there is no appropriateness in asking the question in regard to a preference or will, because this cannot be so acted on. If so acted on, it would not be a will or preference. There is no such thing as a will which a man is not conscious of as belonging to himself, no such thing as an act of will which he is not conscious of as issuing from himself. To ask whether he has power over it, or whether some other power than he determines it, is like asking whether he is other than himself. Thus the question whether a man, having power to act according to his will, or being free to act, has also power over his will, or is free to will, has just the same impropriety that Locke points out in the question whether the will is free. The latter question, on the supposition that there is power to enact the will,—a supposition which is necessarily made by those who raise the ulterior question whether there is power over the will,—is equivalent, as Locke sees, to a question whether freedom is free. For a will which there is power of enacting constitutes freedom, and therefore to ask whether it is free is like asking (to use Locke's instance) whether riches are rich ('rich' being a denomination from the possession of riches, just as 'free' is a denomination from the possession of freedom, in the sense of a will which there is power to enact). But if there is this impropriety in the question whether the will is free, there is an equal one in the question which Locke entertains, viz. whether man is free to will, or has power over his will. It amounts to asking whether a certain power is also a power over itself: or, more precisely, whether a man possessing a certain power—that which we call freedom—has also the same power over that power.

10. It may be said perhaps that we are here pressing words too closely; that it is of course understood, when it is asked whether a man has power over his will, that 'power' is used in a different sense from that which it bears when it is asked whether he has power to enact his will: that 'freedom,' in like manner, is understood to express a different kind of power or relation when we ask whether a man is free to will, and when we ask whether he is free to act. But granting that all this has been understood, the misleading effects of the question in the form under consideration ('Is a man free to will as well as to act?' 'Has he power over his will?') remain written in the history of the 'free-will controversy.' It has mainly to answer for two wrong ways of thinking on the subject; (a) for the way of thinking of the determining motive of an act of will, the object willed, as something apart from the will or the man willing, so that in being determined by it the man is supposed not to be self-determined, but to be determined as one natural event by another, or at best as a natural organism by the forces acting on it: (b), for the view that the only way of escaping this conclusion is to regard the will as independent of motives, as a power of deciding between motives without any motive to determine the decision, which must mean without reference to any object willed. A man, having (in virtue of his power of self-distinction and self-objectification) presented his will to himself as something to be thought about, and being asked whether he has power over it, whether he is free in regard to it as he is free against other persons and free to use his limbs and, through them, material things, this way or that, must very soon decide that he is not. His will is himself. His character necessarily shows itself in his will. We have already, in a previous lecture, [1] noticed the practical fallacy involved in a man's saying that he cannot help being what he is, as if he were controlled by external power; but he being what he is, and the circumstances being what they are at any particular conjuncture, the determination of the will is already given, just as an effect is given in the sum of its conditions. The determination of the will might be different, but only through the man's being different, But to ask whether a man has power over determinations of his will, or is free to will as he is to act, as the question is commonly understood and as Locke understood it, is to ask whether, the man being what at any time he is, it is still uncertain (1) whether he will choose or forbear choosing between certain possible courses of action, and (2) supposing him to choose one or other of them, which he will choose.

[1] [Prolegomena to Ethics, Sections 107, ff.—RLN]

11. Now we must admit that there is really no such uncertainty. The appearance of it is due to our ignorance of the man and the circumstances. If, however, because this is so, we answer the question whether a man has power over his will, or is free to will, in the negative, [1] we at once suggest the conclusion that something else has power over it, viz. the strongest motive. We ignore the truth that in being determined by a strongest motive, in the only sense in which he is really so determined, the man (as previously explained) [2] is determined by himself, by an object of his own making, and we come to think of the will as determined like any natural phenomenon by causes external to it. All this is the consequence of asking questions about the relation between a man and his will in terms only appropriate to the relation between the man and other men, or to that between the man and his bodily members or the materials on which he acts through them.

[1] Instead of saying (as we should) that it is one of those inappropriate questions to which there is no answer; since a man's will is himself, and 'freedom' and 'power' express relations between a man and something other than himself.

[2] [See Prolegomena to Ethics, Section 105.—RLN]

12. On the other side the consciousness of self-determination resists this conclusion; but so long as we start from the question whether a man has power over his will, or is free to will as well as to act, it seems as if the objectionable conclusion could only be avoided by answering this question in the affirmative. But to say that a man has power over determinations of his will is naturally taken to mean that he can change his will while he himself remains the same; that given his character, motives, and circumstances as these at any time are, there is still something else required for the determination of his will; that behind and beyond the will as determined by some motive there is a will, itself undetermined by any motive, that determines what the determining motive shall be,—that 'has power over' his preference or choice, as this has over the motion of his bodily members. But an unmotived will is a will without an object, which is nothing. The power or possibility, beyond any actual determination of the will, of determining what that determination shall be is a mere negation of the actual determination. It is that determination as it becomes after an abstraction of the motive or object willed, which in fact leaves nothing at all. If those moral interests, which are undoubtedly involved in the recognition of the distinction between man and any natural phenomenon, are to be made dependent on belief in such a power or abstract possibility, the case is hopeless.

13. The right way out of the difficulty lies in the discernment that the question whether a man is free to will, or has power over the determinations of his will, is a question to which there is no answer, because it is asked in inappropriate terms; in terms that imply some agency beyond the will which determines what the will shall be (as the will itself is an agency beyond the motions of the muscles which determines what those motions shall be), and that as to this agency it may be asked whether it does or does not lie in the man himself. In truth there is no such agency beyond the will and determining how the will shall be determined; not in the man, for the will is the self-conscious man; not elsewhere than in the man, not outside him, for the self-conscious man has no outside. He is not a body in space with other bodies elsewhere in space acting upon it and determining its motions. The self-conscious man is determined by objects, which in order to be objects must already be in consciousness, and in order to be his objects, the objects which determine him, must already have been made his own. To say that they have power over him or his will, and that he or his will has power over them, is equally misleading. Such language is only applicable to the relation between an agent and patient, when the agent and the patient (or at any rate the agent) can exist separately. But self-consciousness and its object, will and its object, form a single individual unity. Without the constitutive action of man or his will the objects do not exist; apart from determination by some object neither he nor his will would be more than an unreal abstraction.

14. If, however, the question is persisted in, 'Has a man power over the determinations of his will?' we must answer both 'yes' and 'no.' 'No,' in the sense that he is not other than his will, with ability to direct it as the will directs the muscles. 'Yes,' in the sense that nothing external to him or his will or self-consciousness has power over them. 'No,' again, in the sense that, given the man and his object as he and it at any time are, there is no possibility of the will being determined except in one way, for the will is already determined, being nothing else than the man as directed to some object. 'Yes,' in the sense that the determining object is determined by the man or will just as much as the man or will by the object. The fact that the state of the man, on which the nature of his object at any time depends, is a result of previous states, does not affect the validity of this last assertion, since (as we have seen [1]) all these states are states of a self-consciousness from which all alien determination, all determination except through the medium of self-consciousness, is excluded.

[1] [Prolegomena to Ethics, Section 102. RLN]

15. In the above we have not supposed any account to be taken of the character of the objects willed in the application to the will itself of the question 'free or not free,' which is properly applied only to an action (motion of the bodily members) or to a relation between one man and other men. Those who unwisely consent to entertain the question whether a man is free to will or has power over determinations of his will, and answer it affirmatively or negatively, consider their answer, whether 'yes' or 'no,' to be equally applicable whatever the nature of the objects willed. If they decide that a man is 'free to will,' they mean that he is so in all cases of willing, whether the object willed be a satisfaction of animal appetite or an act of heroic self-sacrifice; and conversely, if they decide that he is not free to will, they mean that he is not so even in cases when the action is done upon cool calculation or upon a principle of duty, as much as when it is done on impulse or in passion. Throughout the controversy as to free will that has been carried on among English psychologists this is the way in which the question has been commonly dealt with. The freedom, claimed or denied for the will, has been claimed or denied for it irrespectively of those objects willed, on the nature of which the goodness or badness of the will depends.

16. On the other hand, with the Stoics, St. Paul, Kant, and Hegel, as we have seen, the attainment of freedom (at any rate of the reality of freedom, as distinct from some mere possibility of it which constitutes the distinctive human nature) depends on the character of the objects willed. In all these ways of thinking, however variously the proper object of will is conceived, it is only as directed to this object, and thus (in Hegelian language) corresponding to its idea, that the will is supposed to be free. The good will is free, not the bad will. Such a view of course implies some element of identity between good will and bad will, between will as not yet corresponding to its idea and will as so corresponding. St. Paul indeed, not being a systematic thinker and being absorbed in the idea of divine grace, is apt to speak as if there were nothing in common between the carnal or natural man (the will as in bondage to the flesh) and the spiritual man (the will as set free); just as Plato commonly ignores the unity of principle in all a man's actions, and represents virtuous actions as coming from the God in man, vicious actions from the beast. Kant and Hegel, however,— though they do not consider the will as it is in every man, good and bad, to be free; though Kant in his later ethical writings, and Hegel (I think) always, confine the term 'Wille' to the will as having attained freedom or come to correspond to its idea, and apply the term 'Willkür' to that self-determining principle of action which belongs to every man and is in their view the mere possibility, not actuality, of freedom,—yet quite recognise what has been above insisted on as the common characteristic of all willing, the fact that it is not a determination from without, like the determination of any natural event or agent, but the realisation of an object which the agent presents to himself or makes his own, the determination by an object of a subject which itself consciously determines that object; and they see that it is only for a subject free in this sense ('an sich' but not 'fur sich,' δυνάμει but not ενεργείᾳ) [1] that the reality of freedom can exist.

[1] [Greek δυνάμει (dynamei) = potential, ενεργείᾳ (energiea) = actuality Tr]

17. Now the propriety or impropriety of the use of 'freedom' to express the state of the will, not as directed to any and every object, but only to those to which, according to the law of nature or the will of God or its 'idea,' it should be directed, is a matter of secondary importance. This usage of the term is, at any rate, no more a departure from the primary or juristic sense than is its application to the will as distinct from action in any sense whatever. And certainly the unsophisticated man, as soon as the usage of 'freedom' to express exemption from control by other men and ability to do as he likes is departed from, can much more readily assimilate the notion of states of the inner man described as bondage to evil passions, to terrors of the law, or on the other hand as freedom from sin and law, freedom in the consciousness of union with God, or of harmony with the true law of one's being, freedom of true loyalty, freedom in devotion to self-imposed duties, than he can assimilate the notion of freedom as freedom to will anything and everything, or as exemption from determination by motives, or the constitution by himself of the motives which determine his will. And there is so far less to justify the extension of the usage of the term in these latter ways than in the former. It would seem indeed that there is a real community of meaning between 'freedom' as expressing the condition of a citizen of a civilised state, and 'freedom' as expressing the condition of a man who is inwardly 'master of himself.' That is to say, the practical conception by a man ('practical' in the sense of having a tendency to realise itself) of a self-satisfaction to be attained in his becoming what he should be, what he has it in him to be, in fulfilment of the law of his being,—or, to vary the words but not the meaning, in attainment of the righteousness of God, or in perfect obedience to self-imposed law,—this practical conception is the outcome of the same self-seeking principle which appears in a man's assertion of himself against other men and against nature ('against other men,' as claiming their recognition of him as being what they are; 'against nature,' as able to use it). This assertion of himself is the demand for freedom, freedom in the primary or juristic sense of power to act according to choice or preference. So far as such freedom is established for any man, this assertion of himself is made good; and such freedom is precious to him because it is an achievement of the self-seeking principle. It is a first satisfaction of its claims, which is the condition of all other satisfaction of them. The consciousness of it is the first form of self-enjoyment, of the joy of the self-conscious spirit in itself as in the one object of absolute value.

18. This form of self-enjoyment, however, is one which consists essentially in the feeling by the subject of a possibility rather than a reality, of what it has it in itself to become, not of what it actually is. To a captive on first winning his liberty, as to a child in the early experience of power over his limbs and through them over material things, this feeling of a boundless possibility of becoming may give real joy; but gradually the sense of what it is not, of the very little that it amounts to, must predominate over the sense of actual good as attained in it. Thus to the grown man, bred to civil liberty in a society which has learnt to make nature its instrument, there is no self-enjoyment in the mere consciousness of freedom as exemption from external control, no sense of an object in which he can satisfy himself having been obtained.

Still, just as the demand for and attainment of freedom from external control is the expression of that same self-seeking principle from which the quest for such an object proceeds, so 'freedom' is the natural term by which the man describes such an object to himself,—describes to himself the state in which he shall have realised his ideal of himself, shall be at one with the law which he recognises as that which he ought to obey, shall have become all that he has it in him to be, and so fulfil the law of his being or 'live according to nature.' Just as the consciousness of an unattainable ideal, of a law recognised as having authority but with which one's will conflicts, of wants and impulses which interfere with the fulfilment of one's possibilities, is a consciousness of impeded energy, a consciousness of oneself as for ever thwarted and held back, so the forecast of deliverance from these conditions is as naturally said to be a forecast of 'freedom' as of peace' or 'blessedness.' Nor is it merely to a select few, and as an expression for a deliverance really (as it would seem) unattainable under the conditions of any life that we know, but regarded by saints as secured for them in another world, and by philosophers as the completion of a process which is eternally complete in God, that 'freedom' commends itself. To any popular audience interested in any work of self-improvement (e.g. to a temperance-meeting seeking to break the bondage to liquor), it is as an effort to attain freedom that such work can be most effectively presented. It is easy to tell such people that the term is being misapplied; that they are quite 'free' as it is, because every one can do as he likes so long as he does not prevent another from doing so; that in any sense in which there is such a thing as 'free will,' to get drunk is as much an act of free will as anything else. Still the feeling of oppression, which always goes along with the consciousness of unfulfilled possibilities, will always give meaning to the representation of the effort after any kind of self-improvement as a demand for 'freedom.'

19. The variation in the meaning of 'freedom' having been thus recognised and accounted for, we come back to the more essential question as to the truth of the view which underlies all theories implying that freedom is in some sense the goal of moral endeavour; the view, namely, that there is some will in a man with which many or most of his voluntary actions do not accord, a higher self that is not satisfied by the objects which yet he deliberately pursues. Some such notion is common to those different theories about freedom which in the rough we have ascribed severally to the Stoics, St. Paul, Kant, and Hegel. It is the same notion which was previously [1] put in the form, 'that a man is subject to a law of his being, in virtue of which he at once seeks self-satisfaction, and is prevented from finding it in the objects which he actually desires, and in which he ordinarily seeks it.' 'What can this mean?' it maybe asked. 'Of course we know that there are weak people who never succeed in getting what they want, either in the sense that they have not ability answering to their will, or that they are always wishing for something which yet they do not will. But it would not be very appropriate to apply the above formula to such people, for the man's will to attain certain objects cannot be ascribed to the same law of his being as the lack of ability to attain them, nor his wish for certain objects to the same law of his being as those stronger desires which determine his will in a contrary direction. At any rate, if the proposition is remotely applicable to the man who is at once selfish and unsuccessful, how can it be true in any sense either of the man who is at once selfish and succeeds, who gets what he wants (as is unquestionably the case with many people who live for what a priori moralists count unworthy objects), or of the man who 'never thinks about himself at all'? So far as the proposition means anything, it would seem to represent Kant's notion, long ago found unthinkable and impossible, the notion of there being two wills or selves in a man, the 'pure' will or ego and the 'empirical' will or ego, the pure will being independent of a man's actual desires and directed to the fulfilment of a universal law of which it is itself the giver, the empirical will being determined by the strongest desire and directed to this or that pleasure. In this proposition the 'objects which the man actually desires and in which he ordinarily seeks satisfaction' are presumably objects of what Kant called the 'empirical will,' while the 'law of his being' corresponds to Kant's 'pure ego.' But just as Kant must be supposed to have believed in some identity between the pure and empirical will, as implied in the one term 'will,' though he does not explain in what this identity consists, so the proposition before us apparently ascribes man's quest for self-satisfaction as directed to certain objects, to the same law of his being which prevents it from finding it there. Is not this nonsense?'

[1] [Above, section 1 RLN]

20. To such questions we answer as follows. The proposition before us, like all the theories of moral freedom which we have noticed, undoubtedly implies that the will of every man is a form of one consciously self-realising principle, which at the same time is not truly or fully expressed in any man's will. As a form of this self-realising principle it may be called, if we like, a 'pure ego' or 'the pure ego' of the particular person; as directed to this or that object in such a way that it does not truly express the self-realising principle of which it is a form, it may be called the 'empirical ego' of that person. But if we use such language, it must be borne in mind that the pure and empirical egos are still not two egos but one ego; the pure ego being the self-realising principle considered with reference either to its idea, its possibility, what it has in itself to become, the law of its being, or to some ultimate actualisation of this possibility; the empirical ego being the same principle as it appears in this or that state of character, which results from its action, but does not represent that which it has in itself to become, does not correspond to its idea or the law of its being. By a consciously self-realising principle is meant a principle that is determined to action by the conception of its own perfection, or by the idea of giving reality to possibilities which are involved in it and of which it is conscious as so involved; or, more precisely, a principle which at each stage of its existence is conscious of a more perfect form of existence as possible for itself, and is moved to action by that consciousness. We must now explain a little more fully how we understand the relation of the principle in question to what we call our wills and our reason,—the will and reason of this man and that,—and how we suppose its action to constitute the progress of morality.

21. By 'practical reason' we mean a consciousness of a possibility of perfection to be realised in and by the subject of the consciousness. By 'will' we mean the effort of a self-conscious subject to satisfy itself. In God, so far as we can ascribe reason and will to Him, we must suppose them to be absolutely united. In Him there can be no distinction between possibility and realisation, between the idea of perfection and the activity determined by it. But in men the self-realising principle, which is the manifestation of God in the world of becoming, in the form which it takes as will at best only tends to reconciliation with itself in the form which it takes as reason. Self-satisfaction, the pursuit of which is will, is sought elsewhere than in the realisation of that consciousness of possible perfection, which is reason. In this sense the object of will does not coincide with the object of reason. On the other hand, just because it is self-satisfaction that is sought in all willing, and because by a self-conscious and self-realising subject it is only in the attainment of its own perfection that such satisfaction can be found, the object of will is intrinsically or potentially, and tends to become actually, the same as that of reason. It is this that we express by saying that man is subject to a law of his being which prevents him from finding satisfaction in the objects in which under the pressure of his desires it is his natural impulse to seek it. This 'natural impulse' (not strictly 'natural') is itself the result of the operation of the self-realising principle upon what would otherwise be an animal system, and is modified, no doubt, with endless complexity in the case of any individual by the result of such operation through the ages of human history. But though the natural impulses of the will are thus the work of the self-realising principle in us, it is not in their gratification that this principle can find the satisfaction which is only to be found in the consciousness of becoming perfect, of realising what it has it in itself to be. In order to any approach to this satisfaction of itself the self-realising principle must carry its work farther. It must overcome the 'natural impulses,' not in the sense of either extinguishing them or denying them an object, but in the sense of fusing them with those higher interests, which have human perfection in some of its forms for their object. Some approach to this fusion we may notice in all good men; not merely in those in whom all natural passions, love, anger, pride, ambition, are enlisted in the service of some great public cause, but in those with whom such passions are all governed by some such commonplace idea as that of educating a family.

22. So far as this state is reached, the man may be said to be reconciled to 'the law of his being' which (as was said above) prevents him from finding satisfaction in the objects in which he ordinarily seeks it, or anywhere but in the realisation in himself of an idea of perfection. Since the law is, in fact, the action of that self-realising subject which is his self, and which exists in God as eternally self-realised, he may be said in this reconciliation to be at peace at once with himself and with God.

Again, he is 'free,' (1) in the sense that he is the author of the law which he obeys (for this law is the expression of that which is his self), and that he obeys it because conscious of himself as its author; in other words, obeys it from that impulse after self-perfection which is the source of the law or rather constitutes it. He is 'free' (2) in the sense that he not merely 'delights in the law after the inward man' (to use St. Paul's phrase), while his natural impulses are at once thwarted by it and thwart him in his effort to conform to it, but that these very impulses have been drawn into its service, so that he is in bondage neither to it nor to the flesh.

From the same point of view we may say that his will is 'autonomous,' conforms to the law which the will itself constitutes, because the law (which prevents him from finding satisfaction anywhere but in the realisation in himself of an idea of perfection) represents the action in him of that self-realising principle of which his will is itself a form. There is an appearance of equivocation, however, in this way of speaking, because the 'will' which is liable not to be autonomous, and which we suppose gradually to approach autonomy in the sense of conforming to the law above described, is not this self-realising principle in the form in which this principle involves or gives the law. On the contrary, it is the self-realising principle as constituting that effort after self-satisfaction in each of us which is liable to be and commonly is directed to objects which are not contributory to the realisation of the idea of perfection,—objects which the self-realising principle accordingly, in the fulfilment of its work, has to set aside. The equivocation is pointed out by saying, that the good will is 'autonomous' in the sense of conforming to a law which the will itself, as reason, constitutes; which is, in fact, a condensed way of saying, that the good will is the will of which the object coincides with that of practical reason; that will has its source in the same self-realising principle which yields that consciousness of a possible self-perfection which we call reason, and that it can only correspond to its idea, or become what it has the possibility of becoming, in being directed to the realisation of that consciousness.

23. According to the view here taken, then, reason and will, even as they exist in men, are one in the sense that they are alike expressions of one self-realising principle. In God, or rather in the ideal human person as he really exists in God, they are actually one; i.e. self-satisfaction is for ever sought and found in the realisation of a completely articulated or thoroughly filled idea of the perfection of the human person. In the historical man—in the men that have been and are coming to be—they tend to unite. In the experience of mankind, and again in the experience of the individual as determined by the experience of mankind, both the idea of a possible perfection of man, the idea of which reason is the faculty, and the impulse after self-satisfaction which belongs to the will, undergo modifications which render their reconciliation in the individual (and it is only in individuals that they can be reconciled, because it is only in them that they exist) more attainable. These modifications may be stated summarily as (1) an increasing concreteness in the idea of human perfection; its gradual development from the vague inarticulate feeling that there is such a thing into a conception of a complex organisation of life, with laws and institutions, with relationships, courtesies, and charities, with arts and graces through which the perfection is to be attained; and (2) a corresponding discipline, through inheritance and education, of those impulses which may be called 'natural' in the sense of being independent of any conscious direction to the fulfilment of an idea of perfection. Such discipline does not amount to the reconciliation of will and reason; it is not even, properly speaking, the beginning of it; for the reconciliation only begins with the direction of the impulse after self-satisfaction to the realisation of an idea of what should be, as such (because it should be); and no discipline through inheritance or education, just because it is only impulses that are natural (in the sense defined) which it can affect, can bring about this direction, which, in theological language, must be not of nature, but of grace. On the contrary, the most refined impulses may be selfishly indulged; i.e. their gratification may be made an object in place of that object which consists in the realisation of the idea of perfection. But unless a discipline and refinement of the natural impulses, through the operation of social institutions and arts, went on pari passu with the expression of the idea of perfection in such institutions and arts, the direction of the impulses of the individual by this idea, when in some form or other it has been consciously awakened in him, would be practically impossible. The moral progress of mankind has no reality except as resulting in the formation of more perfect individual characters; but on the other hand every progress towards perfection on the part of the individual character presupposes some embodiment or expression of itself by the self-realising principle in what may be called (to speak most generally) the organisation of life. It is in turn, however, only through the action of individuals that this organisation of life is achieved.

24. Thus the process of reconciliation between will and reason,—the process through which each alike comes actually to be or to do what it is and does in possibility, or according to its idea, or according to the law of its being,—so far as it comes within our experience may be described as follows. A certain action of the self-realising principle, of which individuals susceptible in various forms to the desire to better themselves have been the media, has resulted in conventional morality; in a system of recognised rules (whether in the shape of law or custom) as to what the good of society requires, which no people seem to be wholly without. The moral progress of the individual, born and bred under such a system of conventional morality, consists (1) in the adjustment of the self-seeking principle in him to the requirements of conventional morality, so that the modes in which he seeks self-satisfaction are regulated by the sense of what is expected of him. This adjustment (which it is the business of education to effect) is so far a determination of the will as in the individual by objects which the universal or national human will, of which the will of the individual is a partial expression, has brought into existence, and is thus a determination of the will by itself. It consists (2) in a process of reflection, by which this feeling in the individual of what is expected of him becomes a conception (under whatever name) of something that universally should be, of something absolutely desirable, of a single end or object of life. The content of this conception may be no more than what was already involved in the individual's feeling of what is expected of him; that is to say, if called upon to state in detail what it is that has to be done for the attainment of the absolute moral end or in obedience to the law of what universally should be, he might only be able to specify conduct which, apart from any such explicit conception, he felt was expected of him. For all that there is a great difference between feeling that a certain line of conduct is expected of me and conceiving it as a form of a universal duty. So long as the requirements of established morality are felt in the former way, they present themselves to the man as imposed from without. Hence, though they are an expression of practical reason, as operating in previous generations of men, yet, unless the individual conceives them as relative to an absolute end common to him with all men, they become antagonistic to the practical reason which operates in him, and which in him is the source at once of the demand for self-satisfaction and of the effort to find himself in, to carry his own unity into, all things presented to him. Unless the actions required of him by 'the divine law, the civil law, and the law of opinion or reputation' (to use Locke's classification) tend to realise his own idea of what should be or is good on the whole, they do not form an object which, as contemplated, he can harmonise with the other objects which he seeks to understand, nor, as a practical object, do they form one in the attainment of which he can satisfy himself. Hence before the completion of the process through which the individual comes to conceive the performance of the actions expected of him under the general form of a duty which in the freedom of his own reason he recognises as binding, there is apt to occur a revolt against conventional morality. The issue of this may either be an apparent suspension of the moral growth of the individual, or a clearer apprehension of the spirit underlying the letter of the obligations laid on him by society, which makes his rational recognition of duty, when arrived at, a much more valuable influence in promoting the moral growth of society.

25. Process (2), which may be called a reconciliation of reason with itself, because it is the appropriation by reason as a personal principle in the individual of the work which reason, acting through the media of other persons, has already achieved in the establishment of conventional morality, is the condition of the third stage in which the moral progress of the individual consists; viz. the growth of a personal interest in the realisation of an idea of what should be, in doing what is believed to contribute to the absolutely desirable, or to human perfection, because it is believed to do so. Just so far as this interest is formed, the reconciliation of the two modes in which the practical reason operates in the individual is effected. The demand for self-satisfaction (practical reason as the will of the individual) is directed to the realisation of an ideal object, the conceived 'should be,' which practical reason as our reason constitutes. The 'autonomy of the will' is thus attained in a higher sense than it is in the 'adjustment' described under (1), because the objects to which it is directed are not merely determined by customs and institutions which are due to the operation of practical reason in previous ages, but are embodiments or expressions of the conception of what absolutely should be as formed by the man who seeks to satisfy himself in their realisation. Indeed, unless in the stage of conformity to conventional morality the principle of obedience is some feeling (though not a clear conception) of what should be, of the desirable as distinct from the desired,—if it is merely fear of pain or hope of pleasure,—there is no approach to autonomy of the will or moral freedom in the conformity. We must not allow the doctrine that such freedom consists in a determination of the will by reason, and the recognition of the truth that the requirements of conventional morality are a product of reason as operating in individuals of the past, to mislead us into supposing that there is any moral freedom, or anything of intrinsic value, in the life of conventional morality as governed by 'interested motives,' by the desire, directly or indirectly, to obtain pleasure. There can be no real determination of the will by reason unless both reason and will are operating in one and the same person. A will is not really anything except as the will of a person, and, as we have seen, a will is not really determinable by anything foreign to itself: it is only determinable by an object which the person willing makes his own. As little is reason really anything apart from a self-conscious subject, or as other than an idea of perfection to be realised in and by such a subject. The determination of will by reason, then, which constitutes moral freedom or autonomy, must mean its determination by an object which a person willing, in virtue of his reason, presents to himself, that object consisting in the realisation of an idea of perfection in and by himself. Kant's view that the action which is merely 'pflichtmässig,' not done 'aus Pflicht,' [1] is of no moral value in itself, whatever may be its possible value as a means to the production of the will which does act 'aus Pflicht,' is once for all true, though he may have taken too narrow a view of the conditions of actions done 'aus Pflicht,' especially in supposing (as he seems to do) that it is necessary to them to be done painfully. There is no determination of will by reason, no moral freedom, in conformity of action to rules of which the establishment is due to the operation of reason or the idea of perfection in men, unless the principle of conformity in the persons conforming is that idea itself in some form or other.

[1] [German aus Pflicht = from duty, pflichtmässig = consistent with duty—Tr.]