Aesop's "Political Fables" (Croxall ed.)

|

|

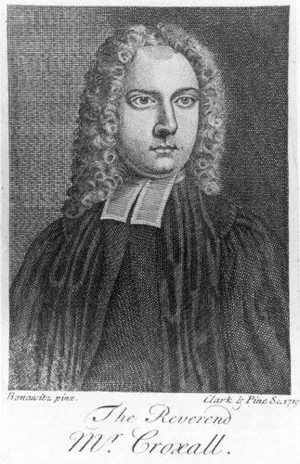

| Samuel Croxall (c. 1690 – 1752) | Top: Fable 2 "The Wolf and the Lamb" Bottom: Fable 19: The Dog and the Wolf" |

Source

Editor's Note: This is my selection of Croxall's more explicit political "Applications" to his collection of Aesop's Fables. The most relevant sections are in bold.

I also include the section from Croxall's Preface where he takes issue with the interpretation of the Fables made by the monarchist Lestrange, whose edition of Aesop's Fables competed with that of Croxall's for many decades.

The edition used is an American one from 1863.

See the complete collection of Fables and Croxall's moral "Application" in HTML and facs. PDF.

Table of Contents

The "Political Fables":

- FAB. II. The Wolf and the Lamb.

- FAB. III. The Frogs desiring a King

- FAB. V. The Dog and the Shadow.

- FAB. VI. The Lion and other Beasts.

- FAB. XIII. The Eagle and the Fox.

- FAB. XV. The Frogs and the fighting Bulls.

- FAB. XVI. The Kite and the Pigeons.

- FAB. XIX. The Dog and the Wolf.

- FAB. XXVI. The Mountains in Labour.

- FAB. XXXIII. The Wood and the Clown.

- FAB. XXXIV. The Horse and the Stag.

- FAB. XXXVII. The Belly and the Members.

- FAB. LIV. The Forester and the Lion.

- FAB. LXXIII. The Sensible Ass.

- FAB. LXXXIII. The Fir-tree and the Bramble.

- FAB. LXXXV. The Fowler and the Black-bird.

- FAB. XCVII. The Fowler and the Lark.

- FAB. CXV. The Judicious Lion.

- FAB. CXXVII. The Fox and the Cock.

- FAB. CXXVIII. The Cat and the Cock.

- FAB. CXXX. The Dog and the Sheep.

- FAB. CXXXI. The Hawk and the Farmer.

- FAB. CXLI. The Lion, the Bear, and the Fox.

- FAB. CXLIII. The Mice in Council.

- FAB. CXLIV. The Lion, the Ass, and the Fox.

- FAB. CXLVl. The Old Man and his Sons.

- FAB. CXLVIII. The Falconer and the Partridge.

- FAB. CL. The Peacock and the Magpie.

- FAB. CLVIII. The Trumpeter taken Prisoner.

- FAB. CLXI. The Wolves and the Sheep.

- FAB. CLXIV. The Horse and the loaded Ass.

- FAB. CLXV. The Bees, the Drones, and the Wasp.

- FAB. CLXVIII. The Frog and the Mouse

- FAB. CLXIX. The Man and the Weasel.

- FAB. CLXXV. The Fisherman.

- FAB. CLXXVII. The Thieves and the Cock.

- FAB. CXCV. The Fox and the Hedge-hog.

PREFACE.↩

[v]

So much has been already said concerning Æsop and his writings, both by ancient and modern authors, that the subject seems to be quite exhausted. The different conjectures, opinions, traditions and forgeries, which from time to time we have had given us of him, would fill a large volume; but they are, for the most part, so absurd and inconsistent, that it would be but a dull amusement for the reader, to be led into such a maze of uncertainty: since Herodotus, the most ancient Greek historian did not flourish till near a hundred years after Æsop. ...

[xvi]

Having given my reader the opinion of this great man who has spoken so much and so well in favour of the subject I am concerned in, there is no room for me to enlarge farther upon that head. His argument demonstrates the usefulness and advantage of this kind of writing, beyond contradiction; it therefore only remains, that I make some apology for troubling the public with a new edition, of what it has had so often, and in so many different forms already.

Nothing of this nature has been done since Lestrange's time, worth mentioning; and we had nothing before, but what (as he observes)[FN: Pref. to Part. 1.] was so insipid and flat in the moral, and so coarse and uncouth in the style and diction, that they were rather dangerous than profitable as to the purpose for which they were principally intended, and likely to do forty times more harm than good. I shall therefore only observe to my reader, the insufficiency of Lestrange's own performance, as to the purpose for which he professes to have principally intended it; with some other circumstances, which will help to excuse, if not justify, what I have enterprised upon the same subject.

Now the purpose for which he principally intended his book, as in his preface he spends a great many words to inform us, was for the use and instruction of children; who being, as it were, mere blank paper, are ready indifferently for any opinion, good or bad, taking all upon credit; and that it is in the power of the first comer to write saint or devil upon them, which he pleases. This [xvii] being truly and certainly the case, what poor devils would Lestrange make of those children, who should be so unfortunate as to read his book, and imbibe his pernicious principles! Principles coined and suited to promote the growth, and serve the ends of popery and arbitrary power. Though we had never been told he was a pensioner to a popish prince, and that he himself professed the same religion, yet his reflections upon Æsop would discover it to us: in every political touch, he shows himself to be the tool and hireling of the popish faction, since, even a slave, without some mercenary view, would not bring arguments to justify slavery, nor endeavour to establish arbitrary power upon the basis of right reason. What sort of children, therefore, are the blank paper, upon which such morality as this ought to be written? Not the children of America, I hope; for they are born with free blood in their veins, and suck in liberty with their very milk. This they should be taught to love and cherish above all things, and, upon occasion, to defend and vindicate it; as it is the glory of their country, the greatest blessing of their lives, and the peculiar happy privilege in which they excel all the world besides. Let therefore the children of Italy, France, Spain, and the rest of the popish countries, furnish him with blank paper, for principles, of which free-born Columbians are not capable. The earlier such notions are instilled into such minds as theirs indeed, the better it will be for them, as it will keep them from thinking of any other than the abject servile condition to which they are born. But let the minds [xviii] of our charming youth be for ever educated and improved in that spirit of truth and liberty, for the support of which their ancestors have bravely exhausted so much blood and treasure.

Had any thing tending to debase and enslave the minds of men been implied, either in the Fables or morals of Æsop, upon which Lestrange was to make just and fair reflections, he might have pleaded that for an excuse. But Æsop, though it was his own incidental misfortune to be a slave, yet passed the time of his servitude among the free states of Greece, where he saw the high esteem in which liberty was held, and possibly learned to value it accordingly. He has not one Fable, or so much as a hint, to favour Lestrange's insinuations; but, on the contrary, takes all occasions to recommend a love of liberty, and an abhorrence of tyranny, and all arbitrary proceedings. Yet Lestrange (though in the preface to his second part, he uses these words, I have consulted the best authorities J could meet withal, in the choice of the collection, without straining any thing, all this while, beyond the strictest equity of a fair and innocent meaning) notoriously perverts both the sense and meaning of several Fables; particularly when any political instruction is couched in the application. For example, in the famous fable of the Dog and the Wolf. After a long, tedious, amusing reflection, without one word to the purpose, he tells us at last, that the freedom which Æsop is so tender of here, is to be understood the freedom of the mind. Nobody ever understood it so I dare say, that knew what the other freedom [xix] was. As for what be mentions, it is not in the power of the greatest tyrant that lives to deprive us of it. If the Wolf was only sensible bow sweet the freedom of mind was, and had no concern for the liberty of his person, he might have ventured to have gone with the Dog well enough: but then he would have saved Lestrange the spoiling of one of the best fables in the whole collection. However this may serve as a pattern to that gentleman's candour and ingenuity in the manner of drawing his reflection. Æsop breathed liberty in a political sense, whenever he thought fit to hint any thing about that unhappy state. And Phaedrus, whose hard lot it once was to have been a domestic slave, had yet so great a veneration for the liberty I am speaking of, that he made no scruple to write in favour of it, even under the usurpation of a tyrant, and at a time when the once glorious free people of Rome had nothing but the form and shadow of their ancient constitution left. This he did particularly in the Fable of The Frogs desiring a king: as I have observed in the application[FN: Fab. III.] to it. After which, I leave it to the decision of any indifferent person, whether Lestrange, in the tenor of his reflections, has proceeded without straining most things, in point of politics, beyond the strictest equity of a fair and an honest meaning.

Whether I have the faults I mention finding with him, in this or any other respect, I must leave to [xx] the judgment of the reader: professing (according to the principle upon which the following applications are built) that I am a lover of liberty and truth; an enemy to tyranny, either in church or state; and one who detests party animosities and factious divisions, as much as I wish the peace and prosperity of my country.

FAB. II. The Wolf and the Lamb.

|

One hot, sultry day, a Wolf and a Lamb happened to come just at the same time, to quench their thirst in the stream of a clear silver brook, that ran tumbling down the side of a rocky mountain. The Wolf stood upon the higher ground, and the Lamb at some distance from him down the current. However, the Wolf, having a mind to pick a quarrel with him, asked him what he meant by disturbing the water, and making it so muddy that he could not drink ; and, at the same time, demanded satisfaction. The Lamb, frightened at this threatening charge, told him, in a tone as mild as possible, that with humble submission, he could not conceive how that could be ; since the water, which he drank, ran down from the Wolf to him, and therefore could not be disturbed so far up the stream. Be that as it will, replies the Wolf, you are a rascal, and I have been told that you treated me with ill language behind my back, about half a year [28] ago. Upon my word, says the Lamb, the time you mention was before I was born. The Wolf, finding it to no purpose to argue any longer against truth, fell into a great passion, snarling and foaming at the mouth as if he had been mad ; and, drawing nearer to the Lamb, Sirrah, says he, if it was not you, it was your father, and that is all one. So he seized the poor, innocent, helpless thing, tore it to pieces, and made a meal of it.

THE APPLICATION.

The thing which is pointed at in this Fable is so obvious, that it will be impertinent to multiply words about it. When a cruel ill-natured man has a mind to abuse one inferior to himself, either in power or courage, though he has not given the least occasion for it, how does he resemble the Wolf! whose envious, rapacious temper could not bear to see innocence live quietly in its neighbourhood. In short, whenever ill people are in power, innocence and integrity are sure to be persecuted ; the more vicious the community is, the better countenance they have for their own villainous measures : to practice honesty in bad times, is being liable to suspicion enough ; but if any one should dare to prescribe it, it is ten to one but he would be impeached of high crimes and misdemeanors : for to stand up for justice in a degenerate corrupt state, is tacitly to upbraid the government, and seldom fails of pulling down vengeance upon the head of him that offers to stir in its defence. Where cruelty and malice are in combination with power, nothing is as easy as for them to find a pretence to tyrannize over innocence and exercise all manner of injustice.

FAB. III. The Frogs desiring a King.↩

|

The Frogs, living an easy free life every where among the lakes and ponds, assembled together one day in a very tumultuous manner, and petitioned Jupiter to let them have a king, who might inspect their morals, and make them live a little honester. Jupiter being at that time in pretty good humour, was pleased to laugh heartily at their ridiculous request ; and throwing a little log down into the pool, cried, there is a king for you. The sudden splash which this made by its fall into the water, at first terrified them so exceedingly, that they were afraid to come near it. But in a little time, seeing it lay without moving, they ventured, by degrees, to approach it ; and at last, finding there was no danger, they leaped upon it ; and, in short, treated it as familiarly as they pleased. But, not content with so insipid a king as this was, they sent their deputies to petition again for another sort [30] of one ; for this they neither did nor could like. Upon that, he sent them a Stork, who, without any ceremony, fell a devouring and eating them up, one after another, as fast as he could. Then they applied themselves privately to Mercury, and got him to speak to Jupiter in their behalf, that he would be so good as to bless them again with another king, or restore them to their former state. No, says he, since it was their own choice, let the obstinate wretches suffer the punishment due to their folly.

THE APPLICATION.

It is pretty extraordinary to find a Fable of this kind, finished with so bold, and yet polite a turn by Phaedrus : one who attained his freedom by the favour of Augustus, and wrote in the time of Tiberius ; who were, successively, tyrannical usurpers of tbe Roman government. If we may take his word for it, Æsop spoke it upon this occasion : When the commonwealth of Athens flourished under good wholesome laws of its own enacting, they relied so much on the security of their liberty, that they negligently suffered it to run out into licentiousness. And factions happening to be fomented among them by designing people, much about the same time, Pisistratus took that opportunity to make himself master of their citadel and liberties both together. The Athenians, finding themselves in a state of slavery, though their tyrant happened to be a very merciful one, yet could not bear the thoughts of it ; so that Æsop, where there was no remedy, prescribes them patience, by the example of the foregoing fable ; and adds, at last, Wherefore, my dear countrymen, be contented with your present condition, had as it is, for fear a change would he for the worse.

FAB. V. The Dog and the Shadow.↩

|

A DOG, crossing a little rivulet with a piece of flesh in his mouth, saw his shadow represented in the clear mirror of the limpid stream ; and believing it to be another dog, who was carrying another piece of flesh, he could not forbear catching at it ; but was so far from getting any thing by his greedy design, that he dropt the piece he had in his mouth, which immediately sunk to the bottom, and was irrecoverably lost.

[33]

THE APPLICATION.

He that catches at more than belongs to him, justly deserves to lose wliat he has. Yet nothing is more common, and at the same time more pernicious, than this selfish principle. It prevails from the king to the peasant; and all orders and degrees of men are, more or less, infected with it. Great monarchs have been drawn in by this greedy humour, to grasp at the dominions of their neighbours; not that they wanted any thing more to feed their luxury, but to gratify their insatiable appetite with vain-glory. If the kings of Persia could have been contented with their own vast territories, they had not lost all Asia for the sake of a little petty state of Greece. And France, with all its glory, has, ere now, been reduced to the last extremity by the same unjust encroachments.

He that thinks he sees another estate in a pack of cards, or a box and dice, and ventures his own in the pursuit of it, should not repine if he finds himself a beggar in the end.

FAB. VI. The Lion and other Beasts.↩

|

The Lion and several other beasts, entered into an alliance offensive and defensive, and were to live very sociable together in the forest. One day, having [34] made a sort of excursion, by way of hunting, they took a very fine, large fat deer, which was divided into four parts ; there happening to be then present, his majesty the Lion, and only three others. After the division was made, and the parts were set out, his majesty advancing forward some steps, and pointing to one of the shares, was pleased to declare himself after the following manner : — This I seize and take possession of as my right, which devolves to me, as I am descended by a true, lineal, hereditary succession from the royal family of the Lion ; that (pointing to the second) I claim by, I think, no unreasonable demand ; considering that all the engagements you have with the enemy turn chiefly upon my courage and conduct, and you very well know that wars are too expensive to be carried on without proper supplies. Then (nodding his head towards the third) that I shall take by virtue of my prerogative ; to which I make no question but so dutiful and loyal a people will pay all tiie deference and regard that I can desire. Now, as for the remaining part, the necessity of our present affairs is so very urgent, our stocks so low, and our credit so impaired and weakened, that I must insist upon your granting that without any hesitation or demur ; and hereof fail not at your peril.

THE APPLICATION.

No alliance is safe which is made with those who are superior to us in power. Though they lay themselves under the most strict and solemn ties at the opening of the congress, yet the first advantageous opportunity will tempt them to break the treaty; and they will never want specious pretences to furnish out their declarations of war. It is not easy to determine, whether it is more stupid and ridiculous for a community, to trust itself in the hands of those that are more powerful than themselves, or to wonder afterwards that their confidence and credulity are abused, and their properties invaded.

FAB. XIII. The Eagle and the Fox.↩

|

An Eagle that had young ones, looking out for something to feed them with, happened to spy a Fox's cub, that lay basking itself abroad in the sun. She made a stoop, and trussed it immediately; but before [45] she had carried it quite off, the old Fox coming home, implored her, with tears in her eyes, to spare her cub, and pity the distress of a poor fond mother, who should think no affliction so great as that of losing her child. The Eagle, whose nest was up in a very high tree, thought herself secure enough from all projects of revenge, and so bore away the cub to her young ones, without showing any regard to the supplications of the Fox. But that subtle creature, highly incensed at this outrageous barbarity, ran to an altar, where some country people had been sacrificing a kid in the open fields, and catching up a fire-brand in her mouth, ran towards the tree where the Eagle's nest was, with a resolution of revenge. She had scarce ascended the first branches, when the Eagle, terrified with the approaching ruin of herself and family, begged of the Fox to desist, and, with much submission, returned her the cub again safe and sound.

THE APPLICATION.

This Fable is a warning to us, not to deal hardly or injuriously by any body. The consideration of our being in a high condition of life, and those we hurt, below us, will plead little or no excuse for us, in this case. For there is scarce a creature of so despicable a rank, but is capable of avenging itself some way, and at some time or other. When great men happen to be wicked, how little scruple do they make of oppressing their poor neighbours! they are perched upon a lofty station, and have built their nest on high; and, having outgrown all feelings of humanity, are insensible of any pangs of remorse. The widow's tears, the orphan's cries, and the curses of the miserable, like javelins thrown by the hand of a feeble old man, fall by the way, and never reach their heart. But let such a one, in the midst of his flagrant injustice, remember, how easy a matter it is, notwithstanding his superior distance, for the meanest vassal to be revenged of him. The bitterness of affliction, even where cunning is wanting, may animate the poorest spirit with resolutions of vengeance, and when once that fury is thoroughly awakened, we know not what she will require before she is lulled to rest again. The mosf powerful tyrants: cannot prevent a resolved assassination ; there are a thousand different ways for any private man to do the business, [46] who is heartily disposed to it, and willing to satisfy his appetite for revenge, at the expense of his life. An old woman may clap a fire-brand to the palace of a prince, and it is in the power of a poor weak fool to destroy the children of the mighty.

FAB. XV. The Frogs and the fighting Bulls.↩

|

A Frog one day peepins: out of the lake, and looking about him, saw two Bulls fighting at some [48] distance off, in the meadow; and calling to one of his acquaintances, Look, says he, what dreadful work there is yonder! Dear Sir, what will become of us? Why, pr'ythee, says the other, do not frighten yourself so about nothing; how can their quarrels affect us? They are of a different kind and way of living, and are at present only contending which shall be master of the herd. That is true, replies the first; their quality and station in life is, to all appearance, different enough from ours: but as one of them will certainly get the better, he that is worsted, being beat out of the meadow, will take refuge here in the marshes, and may possibly tread out the guts of some of us; so you see we are more nearly concerned in this dispute of theirs than at first you were aware of.

THE APPLICATION.

This poor timorous frog had just reason for its fears and suspicions: it being hardly possible for great people to fall out, without involving many below them in the same fate. Nay, whatever becomes of the former, the latter are sure to suffer; those may be only playing the fool, while these really smart for it.

It is of no small importance to the honest, quiet part of mankind, who desire nothing so much as to see peace and virtue flourish, to enter seriously and impartially into the consideration of this point; for, as significant as the quarrels of the great may sometimes be, yet they are nothing without their espousing and supporting them one way or other. What is it that occasions parties, but the ambitious or avaricious spirit of men in eminent stations, who want to engross all power in their own hands? upon this they foment divisions, and form factions, and excite animosities between well meaning, but undeserving people, who little think that the great aim of their leaders is no more than the advancement of their own private self-interest. The good of the public is always pretended upon such occasions, and may sometimes happen to be tacked to their own; but then it is purely accidental, and was never originally intended. One knows not what remedy to prescribe against so epidemical and frequent a malady, but only, that every man who has sense enough to discern the pitiful private views that attend most of the differences between the great ones, instead of aiding or abetting either party, would with an honest courage, heartily and openly oppose both.

FAB. XVI. The Kite and the Pigeons.↩

|

A Kite, who had kept sailing in the air for many days near a dove house, and made a stoop at several Pigeons, but all to no purpose, (for they were too nimble for him,) at last had recourse to stratagem; and took his opportunity one day, to make a declaration to them, in which he set forth his own just and good intentions, who had nothing more at heart, than the defence and protection of the Pigeons in their ancient, rights and liberties, and how concerned he was at their fears and jealousies of a foreign invasion; especially their unjust and unreasonable suspicions of himself, as if he intended, by force of arms, to break in upon their constitution, and erect a tyrannical government over them. To prevent all which, and thoroughly to quiet their minds, he thought proper to propose to them such terms of alliance and articles of peace, as might for ever cement a good understanding betwixt them; the principal of which was, that they [60] should accept of him for their king, and invest him with all kingly privilege and prerogative over them. The poor simple Pigeons consented; the Kite took the coronation oath after a very solemn manner, on his part, and the doves the oaths of allegiance and fidelity on theirs. But much time had not passed over their heads, before the good Kite pretended that it was part of his prerogative to devour a Pigeon whenever he pleased. And this, he was not contented to do himself only, but instructed the rest of the royal family in the same kingly arts of government. The Pigeons, reduced to this miserable condition, said one to the other, Ah! we deserve no better! Why did we let him come in?

THE APPLICATION.

What can this Fable be applied to, but the exceeding blindness and stupidity of that part of mankind, who wantonly and foolishly trust their native rights of liberty, without good security; who often choose for guardians of their lives and fortunes, persons abandoned to the most unsociable vices; and seldom have any better excuse for such an error in politics, than, that they were deceived in their expectation; or never thoroughly knew the manners of their king, till he had got them entirely into his power; which, however, is notoriously false, for many, with the doves in the Fable, are so silly, that they would admit of a Kite, rather than be without a king. The truth is, we ought not to incur the possibility of being deceived in so important a matter as this; an unlimited power should not be trusted in the hands of any one, who is not endowed with a perfection more than human.

FAB. XIX. The Dog and the Wolf.↩

|

A lean, hungry, half-starved Wolf, happened one rnoonshiny night, to meet with a jolly, plump, well-fed Mastiff: and after the first compliments were passed, says the Wolf, you look extremely well; I profess, I think I never saw a more graceful, comely person; but how comes it about, I beseech you, that you should live so much better than I? I may say, without vanity, that I venture fifty times more than you do; and yet, I am almost ready to perish with hunger. The Dog answered very bluntly. Why you may live as well, if you will do the same for it that I do. Indeed! What is that says he: Why, says the Dog, only to guard the house at night, and keep it from thieves. With all my heart, replies the Wolf: for at present I have but a sorry time of it; and I think, to change my hard lodging in the woods, where I endure rain, frost and snow, for a warm roof over my head, and a belly full of good victuals, will be no bad [56] bargain. True, says the Dog, therefore you have nothing more to do but to follow me. Now as they were jogging on together, the Wolf spied a crease in the Dog's neck, and having a strange curiosity, could not forbear asking him what it meant? Puh! nothing says the Dog. Nay, but pray, says the Wolf. Why, says the Dog, if you must know, I am tied up in the day time, because I am a little fierce, for fear I should bite people, and am only let loose a-nights. But this is done with a design to make me sleep a-days more than any thing else, and that I may watch the better in the night time; for as soon as ever the twilight appears, out I am turned, and may go where I please. Then, my master brings me plates of bones from the table with his own hands; and whatever scraps are left by any of the family, they fall to my share; for you must know I am a favourite with every body. So you see how you are to live — Come, come along, what is the matter with you? No, replied the Wolf, I beg your pardon; keep your happiness all to yourself. Liberty is the word with me; and I would not be a king upon the terms you mention.

THE APPLICATION.

The lowest condition of life, with freedom attending it, is better than the most exalted station under restraint. Æsop and Phaedrus who had both felt the bitter effects of slavery, though the latter of them had the good fortune to have one of the mildest princes that ever was, for his master, cannot forbear taking all opportunities to express their great abhorrence of servitude, and their passion for liberty, upon any terms whatsoever. Indeed, a state of slavery, with whatever seeming grandeur and happiness it may be attended, is yet so precarious a thing, that he must want sense, honour, courage, and all manner of virtue, who can endure to prefer it in his choice. A man who has so little honour as to bear to be a slave, when it is in his power to prevent or redress it, would make no scruple to cut the throats of his fellow-creatures, or do any wickedness that the wanton unbridled will of his tyrannical master could suggest.

FAB. XXVI. The Mountains in Labour.↩

|

The Mountains were said to be in labour, and uttered most dreadful groans. The people came together, far and near, to see what birth would be produced: and after they had waited a considerable time in expectation, out crept a mouse.

THE APPLICATION.

Great cry and little wool, is the English proverb; the scene of which bears an exact proportion to this Fable. By which are exposed, all those who promise something exceeding great, but come off with a production ridiculously little. Projectors of all kinds who endeavour by artificial rumours to raise the expectations of mankind, and then by their mean performances defeat and disappoint them, have, time out of mind, been lashed with the recital of this fable. How agreeably surprising it is to see an unpromising favourite, whom the caprice of fortune has placed at the helm of state, serving the Commonwealth with justice and integrity, instead of smothering and embezziling the public treasure to his own private and wicked ends! and on the contrary, how melancholy, how dreadfull or rather, how exasperating and provoking a sight is it, to behold one, whose constant declaration for liberty and the public good, have raised [67] people's expectations of him to the highest pitch, as soon as he is got into power exerting his whole art and cunning to ruin and enslave his country! the sanguine hopes of all those that wish well to virtue, and flattered themselves with a reformation of every thing that opposed the well-being of the community, vanish away in smoke, and are lost in the dark, gloomy, uncomfortable prospect.

FAB. XXXIII. The Wood and the Clown.↩

|

A Country fellow came one day into the wood, and looked about him with some concern; upon which the trees, with a curiosity natural to some other creatures, asked him what he wanted? He replied, that he wanted only a piece of wood to make a handle to his hatchet. Since that was all, it was voted unanimously that he should have a piece of good, sound, tough ash. But he had no sooner received and fitted it for his purpose, than he began to lay about him unmercifully, and to hack and hew without distinction, felling the noblest trees in all the forest. Then the oak is said to have spoken thus to the beech, in a low whisper. Brother, we must take it for our pains.

THE APPLICATION.

No people are more justly liable to suffer than those who furnish their enemies with any kind of assistanee. It is generous to forgive, it is enjoined on us by religion to love our enemies; but he that trusts, much more contributes to the strengthening [79] and arming of an enemy, may almost depend upon repenting him of his inadvertent benevolence: and his moreover this to add to his distress; that when he might have prevented it he brought his misfortunes upon himself, by his own credulity.

Any person in a community, by what name or title soever distinguished, who affects a power which may possibly hurt the people, is an enemy to that people, and therefore they ought not to trust him: for though he were ever so fully determined not to abuse such a power, yet he is so far a bad man, as he disturbs the people's quiet, and makes them jealous and uneasy, by desiring to have it, or even retaining it, when it may prove mischievous. If we consult history, we shall find that the thing called Prerogative, has been claimed and contended for chiefly by those who never intended to make a good use of it; and as readily resigned and thrown up by just and wise princes, who had the true interest of their people at heart. How like senseless stocks do they act, who, by complimenting some capricious mortal, from time to time, with parcels of prerogative, at last put it out of their power to defend and maintain themselves in their just and natural liberty.

FAB. XXXIV. The Horse and the Stag.↩

|

The Stag with his sharp horns, got the better of [80] the horse, and drove him clear out of the pasture where they used to feed together. So the latter craved the assistance of man; and, in order to receive the benefit of it, suffered him to put a bridle into his mouth, and a saddle upon his back. By this way of proceeding, he entirely defeated his enemy: but was mightily disappointed, when, upon returning thanks, and desiring to be dismissed, he received this answer: No. I never knew before how useful a drudge you were; now I have found what you are good for, you may depend upon it I will keep you to it.

THE APPLICATION.

As the foregoingfable was intended to caution us against consenting to any thing that might prejudice public liberty, this may serve to keep us upon our guard in the preservation of that which is of a private nature. This is the use and interpretation given of it by Horace, the best and most polite philosopher that wrote. After reciting the fable, he applies it thus: this, says he, is the case of him, who, dreading poverty, parts with that invaluabie jewel, liberty: like a wretch as he is, he will always be subject to a tyrant of some sort or other, and be a slave for ever; because his avaricious spirit knew not how to be contented with that, moderate competency, which he might have possessed independent of the world.

FAB. XXXVII. The Belly and the Members.↩

|

In former days, when the Belly and the other parts of the body enjoyed the faculty of speech, they had separate views and designs of their own: each part it seems in particular for himself, and in the name of the whole, took exceptions at the conduct of the Belly, and were resolved to grant him supplies no longer. They said they thought it very hard, that he should lead an idle good-for-nothing life, spending and squandering away, upon his own ungodly guts, all the fruits of their labour; and that, in short, they were resolved for the future, to strike off his allowance, and let him shift for himself as well as he could. The hands protested they would not lift up a finger to keep him from starving; and the mouth wished he might never speak again, if he took in the least bit of nourishment for him as long as he lived; and, say the teeth, may we be rotted, if ever we chew a morsel for him for the [87] future. This solemn league and covenant was kept as long as any thing of that kind can be kept, which was, until each of the rebel members pined away to skin and bone, and could hold out no longer. Then they found there was no doing without the belly, and that, as idle and insignificant as he seemed, he contributed as much to the maintenance and welfare of all the other parts, as they did to his.

THE APPLICATION.

This fable was spoken by Meninius Agrippa, a famous Roman Consul and General, when he was deputed by the Senate to appease a dangerous tumult and insurrection of the people. The many wars that nation was engaged in, and the frequent supplies they were obliged to raise, had so soured and inflamed the minds of the populace, that they were resolved to endure it no longer, and obstinately refused to pay the taxes which were levied upon them. It is easy to discern how the great man applied this fable. For if the branches and members of a community refuse the government that aid which its necessaries require, the whole must perish together. The rulers of a state, as idle and insignificant as they may sometimes seem, are yet as necessary to be kept up and maintained in a proper and decent grandeur, as the family of each private person is, in a condition suitable to itself. Every man's enjoyment of that little which he gains by his daily labour, depends upon the government's being maintained in a condition to defend and secure him in it.

FAB. LIV. The Forester and the Lion.↩

|

The Forester meeting with a Lion, one day, they discoursed together for a while, without differing much in opinion. At last, a dispute happening to arise about the point of superiority between a Man and a Lion, the Man wanting a better argument, showed the Lion a marble monument, on which was placed the statue of a man striding over a vanquished lion. If this, says the Lion, is all you have to say for it, let us be the carvers, and we will make the lion striding over the man.

THE APPLICATION.

Contending parties are very apt to appeal for the truth to records written by their own side; but nothing is more unfair, and at the same time insignificant and unconvincing. Such is the partiality of mankind in favour of themselves and their own actions, that it is almost impossible to come at any certainty by reading the accounts which are written on one side only. We have few or no memoirs come down to us of what was transacted in the world during the sovereignty of ancient Rome, but what were written by those who had a dependency upon it; [114] therefore it is no wonder that they appear, upon most occasions, lo have been so great and glorious a nation. What their contemporaries of other countries thought of them we cannot tell, otherwise than from their own writers; it is not impossible but that they might have described them as a barbarous, rapacious, treacherous, impolite people; who upon their conquest of Greece, for some time, made a great havoc and destruction of the arts and sciences, as their fellow plunderers the Goths and Vandals did, afterwards, in Italy. What monsters would our own party-zealots make of each other, if the transactions of the times were to be handed down to posterity, by a warm-hearted man on either side? and were such records to survive two or three centuries, with what perplexities and difficulties must they embarrass a young historian, as by turns he consulted them for the characters of his great forefathers! if it should so happen, it were to be wished this application might be living at the same time; that young readers instead of doubting to which they should give their credit, would not fail to remember, that this was the work of a man, that of a lion.

FAB. LXXIII. The Sensible Ass.↩

|

An old fellow was feeding an Ass in a fine green meadow; and being alarmed with the sudden approach of the enemy, was impatient with the Ass to put himself [145] forward, and fly with all the speed that he was able. The Ass asked him, whether or no he thought the enemy would clap two pair of panniers upon his back? the man said no, there was no fear of that. Why then, says the Ass, I'll not stir an inch for what is it to me who my master is, since I shall but carry my panniers, as usual.

THE APPLICATION.

This Fable shows us, how much in the wrong the poorer sort of people most commonly are, when they are under any concern about the revolutions of government. All the alterations which they can feel is, in the name of their sovereign, or some such important trifle; but they cannot well be poorer, or made to work harder than they did before. And yet how are they sometimes imposed upon, and drawn in, by the artifices of a few mistaken or designing men, to foment factions, and raise rebellions in cases where they can get nothing by the success: but, if they miscarry, are in danger of suffering an ignominious, untimely death.

FAB. LXXXIII. The Fir-tree and the Bramble.↩

|

A tall straight Fir-tree, that stood towering up in the middle of the forest, was so proud of his dignity and high station, that he overlooked the little shrubs which grew beneath him. A bramble, being one of the inferior throng, could by no means brook this haughty carriage, and therefore took him to task, and desired to know what he meant by it? Because, says the Fir-tree, I look upon myself as the first tree for beauty and rank, of any in the forest; my spiring top shoots up into the clouds, and my branches display themselves with a perpetual beauty and verdure; while you lie grovelling upon the ground, liable to be crushed by every foot that comes near you, and impoverished by the luxurious drippings which fall from my leaves. All this may be true, replied the bramble; but when the woodman has marked you out for public use, and the sounding axe comes to be applied to [161] your root, I am mistaken if you would not be glad to change conditions with the very worst of us.

THE APPLICATION

If the great were to reckon upon the mischiefs to which they are exposed, and poor private men consider the dangers which they many times escape, purely by being so, notwithstanding the seeming difference there appears to be between them, it would be no such easy matter, as most people think it, to determine which condition is the more preferable. A reasonable man would declare in favour of the latter, without the least hesitation, as knowing upon what a steady and safe security it is established. For the higher a man is exalted, the fairer mark he gives, and the more unlikely he is to escape a storm.

What little foundation therefore has the greatest favourite to fortune, to behave himself with insolence to those below him; whose circumstances, though he is so elated with pride, as to despise them, are, in the eye of every prudent man, more eligible than his own, and such as he himself, when the day of account comes, will wish he had never exceeded. For, as the riches which many over-grown great ones call the goods of fortune, are seldom any other than the goods of the public, which they have impudently, and feloniously taken, so public justice generally overtakes them in the end; and whatever their life may have been, their death is as ignominious and unpitied as that of the meanest and most obscure thief.

FAB. LXXXV. The Fowler and the Black-bird.↩

|

A Fowler was placing his nets, and putting his tackles in order, by the side of a copse, when a Blackbird, who saw him, had the curiosity to inquire what he was doing. Says he, I am building a city for you birds to live in; and providing it with meat, and all manner of conveniences for you. Having said this, he departed and hid himself; and the black-bird, believing his words, came into the nets and was taken. But when the man came up to take hold of him, if this, says he, be your faith and honesty, and these the [164] cities you build, I am of opinion, you will have but few inhabitants.

THE APPLICATION

Methinks this fowler acted a part very like that which some kings and rulers of the people do, when they tell them, that the projects which they have contrived with a separate view, and for their own private interests, are laid for the benefit of all that will come to them. And to such the black-bird truly speaks, when he affirms, that erectors of such schemes will find but few to stick by them at the long run.

We exclaim against it, as something very base and dishonest, when those of a different nation, and even our enemies, break the faith which they have publicly plighted, and tricked us out of our properties. But what must we call it, when governors themselves circumvent their own people, and contrary to the forms upon which they are admitted to govern, contrive traps and gins to catch and ensnare them in? Such governors may succeed in their plots the first time; but must not be surprised, if those who have once escaped their clutches, never have opinion enough of them to trust them for the future.

FAB. XCVII. The Fowler and the Lark.↩

|

A Fowler sat snares to catch larks in the open field. A Lark was caught, and finding herself entangled, could not forbear lamenting her hard fate. Ah! wo is me, says she, what crime have I committed? I have taken neither silver nor gold, nor any thing of value; but must die for only eating a poor grain of wheat.

THE APPLICATION

The irregular administration of justice in the world, is indeed a very melancholy subject to think of. A poor fellow shall be hanged for stealing a rotten sheep, perhaps to keep his family from starving, while one, who is already great and opulent, shall, for that very reason, think himself privileged to commit almost any enormities. But it is necessary that a show and form of justice should be kept up; otherwise, were people to be ever so great and successful rogues, they would not be able to keep possession of, and enjoy their plunder. One of our poets, in his description of a court of justice, calls it a place

Where little villains must submit to fate,

That great ones may enjoy the world in state.[183]

What a sad thing is it to reflect (and the more sad, because not to be remedied) that a man may rob the public of millions, and escape at last, when he that is taken picking a pocket of five shillings, unless he knows how to make a friend, is sure to owing for it.

FAB. CXV. The Judicious Lion.↩

|

A Lion having taken a young Bullock, stood over, and was just going to devour it, when a thief stept in, and cried halves with him. No, friend, says the lion, you are too apt to take what is not your due, and therefore I shall have nothing to say to you. By chance a poor honest traveller happened to come that way, and seeing the lion, modestly and timorously withdrew, intending to go another way. Upon which, the generous beast, with a courteous, affable behaviour, [211] desired him to come forward, and partake with him in that, to which his modesty and humility had given him so good a title. Then dividing the prey into two equal parts, and feasting himself upon one of them, he retired into the woods, and left the place clear for the honest man to come in and take his share.

THE APPLICATION.

There is no one but will readily allow this behaviour of the Lion to have been commendable and just; notwithstanding which, greediness and importunity never fail to thrive and attain their ends, while modesty starves, and is for ever poor. Nothing is more disagreeable to quiet reasonable men, than those that are petulant, forward and craving, in soliciting for their favours; and yet favours are seldom bestowed, but upon such as have extorted them by these teasing offensive means. Every patron, when he speaks his real thoughts, is ready to acknowledge that the modest man has the best title to his esteem; yet he suffers himself too often to be prevailed upon, merely by outrageous noise, to give that to a shameless assuming fellow, which he knows to be justly due to the silent, unapplying modest man.

It would be a laudable thing in a man in power, to make a resolution not to confer any advantageous post upon the person that asks him for it; as it would free him from importunity, and afford him a quiet leisure, upon any vacancy, either to consider with himself who had deserved best of their country, or to inquire and be informed by those whom he could trust. But as this is seldom or never practised, no wonder that we often find the names of men of little merit, mentioned in public prints, as advanced to considerable stations, who are capable of being known to the public in no other way.

FAB. CXXVII. The Fox and the Cock.↩

|

A Cock being perched among the branches of a lofty tree, crowed aloud, so that the shrillness of his voice echoed through the wood, and invited a Fox to the place, who was prowling in that neighbourhood in quest of his prey. But Reynard, finding the Cock was inaccessible, by reason of the height of his situation, had recourse to stratagem, in order to decoy him down; so approaching the tree. Cousin, says he, I am heartily glad to see you; but at the same time, I cannot forbear expressing my uneasiness at the inconvenience of the place, which would not let me pay my respects to you in a handsomer manner; though I suppose you will come down presently, and so that difficulty is easily removed. Indeed, Cousin, says the Cock, to tell you the truth, I do not think it safe to venture myself upon the ground; for though I am convinced how much you are my friend, yet I may have the misfortune to fall into the clutches of some other [233] beast, and what will become of me then? O dear, says Reynard, is it possible that you can be so ignorant, as not to know of the peace that has lately been proclaimed between all kinds of birds and beasts, and that we are, for the future, to forbear hostilities on all sides, and to live in the utmost love and harmony, and that under the penalty of suffering the severest punishment that can be inflicted? All this while the Cock seemed to give but little attention to what was said, but stretched out his neck as if he saw something at a distance. Cousin, says the Fox, what is that you look at so earnestly? Why, says the Cock, I think I see a pack of hounds yonder, a little way off. Oh then, says the Fox, your humble servant, I must be gone. Nay, pray. Cousin, do not go, says the Cock; I am just a coming down; sure you are not afraid of dogs in these peaceable times. No, no, says he; but ten to one whether they have heard of the proclamation yet.

THE APPLICATION.

It is a very agreeable thing to see craft repelled by cunning, more especially to behold the snares of the wicked broken and defeated by the discreet management of the innocent. The moral of this fable principally puts us in mind, not to be too credulous towards the insinuations of those, who are already distinguished by their want of faith and honesty. It is the nature of a wicked minister of state to plunder and devour the people, as much as it is the quality of a Fox to prey upon poultry. When therefore any such would draw us into a compliance with their destructive measures, by a pretended civility, and extraordinary concern for our interest, we should consider such proposals in their true light, as a bait artfully placed to conceal the fatal hook which is intended to draw us into captivity and thraldom. An honest man, with a little plain sense, may do a thousand advantageous things for the public good, and without being master of much address or rhetoric, as easily convince people that his designs are intended for their welfare; but a wicked designing politician, though he has a tongue as eloquent as ever spoke, may sometimes be disappointed in his projects and foiled in his schemes; especially when their destructive texture is so [234] coarsely spun, and the threads of mischief are so large in them, as to be felt even by those whose senses are scarce perfect enough to see and understand them.

FAB. CXXVIII. The Cat and the Cock. ↩

|

The Cat having a mind to make a meal of the Cock, seized him one morning by surprise, and asked him what he could say for himself, why slaughter should not pass upon him? The Cock replied, that he was serviceable to mankind, by crowing in the morning, and calling them up to their daily labour. That is true, says the cat, and is the very objection that I have against you; for you make such a shrill impertinent noise, that people cannot sleep for you. Besides, you are an incestuous rascal, and make no scruple of laying with your mother and sisters. Well, says the Cock, this I do not deny; but I do it to procure eggs and chickens for my master. Ah! villain, says the Cat, hold your wicked tongue; such impieties as these declare that you are no longer fit to live.

[235]

THE APPLICATION.

When a wicked man in power, has a mind to glut his appetite, in any respect, innocence or even merit, is no protection against him. The cries of justice and the voice of reason, are of no effect upon a conscience hardened in iniquity, and a mind versed in a long practice of wrong and robbery; remonstrances, however reasonably urged, or movingly couched, have no more influence upon the heart of such a one, than the gentle breeze has upon the oak, when it whispers among its branches; or the rising surges upon the deaf rock, when they dash and break against its sides.

Power should never be trusted in the hands of an impious selfish man, and one that has more regard to the gratification of his own unbounded avarice, and to public peace and justice. Were it not for that tacit consent and heartless compliance of a great majority of fools, mankind would not be rode, as oftentimes they are, by a little majority of knaves, to their misfortune; for whatever people may think of the times, if they were ten times worse than they are, it is principally owing to their own stupidity: why do they trust the man a moment longer who has once injured and betrayed them?

FAB. CXXX. The Dog and the Sheep.↩

|

The Dog sued the Sheep for a debt, of which the [238] Kite and the Wolf were to be judges. They, without debating long upon the matter, or making any scruple for want of evidence, gave sentence for the plaintiff, who immediately tore the poor sheep in pieces, and divided the spoil with the unjust judges.

THE APPLICATION.

Deplorable are the times, when open barefaced villany is protected and encouraged, when innocence is obnoxious, honesty contemptible, and it is reckoned criminal to espouse the cause of virtue. Men originally entered into covenants and civil compacts with each other for the promotion of their happiness and well being, for the establishment of justice and public peace. How comes it then that they look stupidly on, and tamely acquiesce when wicked men prevent this end, and establish an arbitrary tyranny of their own, upon the foundation of fraud and oppression? Among beasts, who are incapable of being civilized by social laws, it is no strange thing to see innocent helpless sheep fall a prey to dogs, wolves, and kites; but it is amazing how mankind could ever sink to such a low degree of cowardice, as to suffer some of the worst of the species to usurp a power over them, to supersede the righteous laws of good government, and to exercise all kinds of injustice and hardship, in gratifying their own vicious lusts. Wherever such enormities are practised, it is when a few rapacious statesmen combine together to get and secure the power in their own hands, and agree to divide the spoil among themselves. For as long as the cause is to be tried only among themselves, no question but they will always vouch for each other. But, at the same time, it is hard to determine which resemble brutes most, they in acting, or the people in suffering them to act their vile selfish schemes .

FAB. CXXXI. The Hawk and the Farmer.↩

|

A Hawk, pursuing a Pigeon over a corn-field, with great eagerness and force, threw himself into a net, which a husbandman had planted there to take the crows; who being employed not far off, and seeing the hawk fluttering in the net, came and took him ; but just as he was going to kill him, the hawk besought him to let him go, assuring him that he was only following a pigeon, and neither intended nor had done any harm to him. To whom the farmer replied and what harm has the poor pigeon done to you ? upon which, he wrung his head off immediately.

THE APPLICATION.

Passion, prejudice, or power, may so far blind a man, as not to suffer him justly to distinguish whether he is not acting injuriously, at the same time that he fancies he is only doing his duty. Now, the best way of being convinced, whether what we do is reasonable and fit, is to put ourselves in the place of the persons with whom we are concerned, and then consult our conscience about the rectitude of our behaviour. For this we [240] may be assured of, that we are acting wrong, or are doing any thing to another, which we should think unjust if it were done to us. Nothing but a habitual inadvertency, as to this particular, can be the occasion that so many ingenious noble spirits are often engaged in courses so opposite to virtue and honour. He that would startle, if a little attorney should tamper with him to forswear himself, to bring off some small offender, some ordinary trespasser, will, without scruple, infringe the constitution of his country, for the precarious prospect of a place or a pension. Which is most corrupt, he that lies like a knight of the post, for half a crown and dinner, or he that does it for the more substantial consideration of a thousand pounds a year? Which would be doing most service to the public; giving true testimony in a case between two private men, and against one little common thief who has stole a gold watch, or voting honestly or courageously against a rogue of state, who has gagged and bound the laws, and stripped the nation? Let those who intend to act justly, but view things in this light, and all would be well. There would be no danger of their oppressing others, or fear of being oppressed themselves.

FAB. CXLI. The Lion, the Bear, and the Fox.↩

|

A Lion and a Bear fell together by the ears over the carcase of a Fawn, which they found in the forest; their title to it being to be decided by force of arms. The battle was severe and tough on both sides; and they held it out, tearing and worrying one another so long, that, with wounds and fatigues, they were so faint and weary, that they were not able to strike another stroke. Thus, while they lay upon the ground, panting and lolling out their tongues, a Fox chanced to pass by that way, who, perceiving how the case stood, very impudently stepped in between them, seized the booty which they had all this while been contending for, and carried it off. The two combatants, who lay and beheld all this, without having strength enough to stir and prevent it, were only wise enough to make this reflection; behold the fruits of our strife and contention! that villain, the Fox, bears away the prize, and we ourselves have deprived each other of the power to recover it from him.

[257]

THE APPLICATION.

When people go to law about an uncertain title, and have spent their whole estates in the contest, nothing is more common than for some little pettifogging attorney to step in, and secure it to himself. The very name of law seems to imply equity and justice, and that is the bait which has drawn in many to their ruin. — Others are excited by their passions, and care not if they destroy themselves, so that they do but see their enemy perish with them. But if we lay aside prejudice and folly, and think calmly of the matter, we shall find, that going to law is not the best way of deciding differences about property, it being, generally speaking, much safer to trust to the arbitration of two or three honest sensible neighbours, than at vast expence of money, time and trouble, to run through the tedious, frivolous forms, with which, by the artifice of greedy lawyers, a court of judicature is contrived to be attended. It has been said, that if mankind would but lead virtuous, moral lives, there would be no occasion for divines; if they would live temperately and soberly, that they would never want physicians; both which assertions, though true in the main, are yet expressed in too great a latitude. But one may venture to affirm, that if men preserved a strict regard to justice and honesty in their dealings with each other, and upon any mistake or misapprehension, were always ready to refer the matter to disinterested umpires of acknowledged judgment and integrity, they never could have the least occasion for lawyers. When people have gone to law, it is rarely to be found but one or both parties was either stupidly obstinate, or rashly inconsiderate. For, if the case should happen to be so intricate, that a man of common sense could not distinguish who had the best title, how easy would it be to have the opinion of the best counsel in the land, and agree to determine it by that? If it should appear dubious even after that, how much better would it be to divide the thing in dispute, rather than go to law, and hazard the losing, not only the whole, but costs and damages into the bargain? In short, if people were but really as well bred, as sensible and honest as they would be thought to be, nobody would go to law.

FAB. CXLIII. The Mice in Council.↩

|

The Mice called a general council, and having met, after the doors were locked, entered into a free consultation about ways and means, how to render their fortunes and estates more secure from the dangers of the cat. Many things were offered, and much was debated pro and con, upon the matter. At last a young mouse, in a fine florid speech, concluded upon an expedient, and that the only one which was to put them in future entirely out of the power of the enemy; and this was, that the cat should wear a bell about his neck, which, upon the least motion, would give the alarm, and be a signal for them to retire into their holes. This speech was received with great applause, and it was even proposed by some, that the mouse who made it should have the thanks of the assembly. Upon which, an old gray mouse, who had sat silent all the while, stood up, and in another [261] speech, owned that the contrivance was admirable, and the author of it without doubt an ingenious mouse; but, he said, he thought it would not be so proper to vote him thanks, till he should farther inform them how this bell was to be fastened about the cat's neck, and what mouse would undertake to do it.

THE APPLICATION.

Many things appear sensible in speculation, which are afterwards found to be impracticable. And since the execution of any thing, is that which is to complete and finish its very existence, what raw counsellors are those who advise, what precipitate politicians those who proceed to the management of things in their nature incapable of answering their own expectations, or their promises to others.

At the same time the fable teaches us not to expose ourselves in any of our little politic Coffee-house committees, by determining what should be done upon every occurrence of mal-administration, when we have neither commission nor power to execute it. He that upon such an occasion adjudges, as a preservative for the state, that this or that should be applied to the neck of those who have been enemies to it, will appear full as ridiculous as the mouse in the fable, when the question is asked, who shall put it there? In reality, we do but expose our selves to the hatred of some, and the contempt of others, when we inadvertently utter our impracticable speculations in respect of the public, either in private company, or authorized assemblies.

FAB. CXLIV. The Lion, the Ass, and the Fox.↩

|

The Lion, the Ass, and the Fox, went a hunting together in the forest; and it was agreed that whatever was taken, should be divided amongst them. — They happened to have very good sport, and caught a large fat stag, which the Lion ordered the Ass to divide. The Ass, according to the best of his capacity, did so, and made three pretty equal shares. But such levelling doings not suiting at all with the craving temper of the greedy Lion, without further delay he flew upon the Ass, and tore him into pieces; and then bid the Fox divide it into two parts. Reynard, who seldom wanted a prompter, however, had his cue given him sufficiently upon this occasion; and so nibling at one little bit for himself, he laid forth all the rest for the Lion's portion. The royal brute was so delighted at this dutiful and handsome proof of his respect, that he could not forbear expressing the satisfaction it gave him: and asked him withal, where [263] he could possibly have learnt so proper, and so courtly a behaviour? Why, replies Reynard, to tell your majesty the truth, I was taught it by the Ass that lies dead there.

THE APPLICATION.

We may learn a great deal of useful experience from the example of other people, if we will but take the pains to observe them. And besides the profit of the instruction, there is no small pleasure in being taught any proper science, at the expense of somebody else. To this purpose, the history of former times, as well as the transactions of the present, are very well adapted ; and so copious, as to be able to furnish us with precedents upon almost every occasion. The rock upon which another has split, is a kind of light-house or beacon, to warn us from the like calamity ; and by taking such an advantage, how easily may we steer a safe course.

He that in any negotiation with his betters, does not well and wisely consider how to behave himself so as not to give offence, may very likely come off as the ass did ; but the cool thinking man, though he should despair of ever making friends of people in power, will be cautious and prudent enough, to do nothing which may provoke them to be his enemies.

FAB. CXLVI. The Old Man and his Sons.↩

|

Ax old man had many sons, who were often falling out with one another. When the father had exerted his authority, and used other means in order to reconcile them, and all to no purpose, at last had recourse to this expedient; he ordered his sons to be called before him, and a short bundle of rods to be brought; and then commanded them, one by one, to try if, with all their might and strength, they could any of them break [266] it: they all tried, but to no purpose; for the rods being closely and compactly bound up together, it was impossible for the force of man to do it. After this, the father ordered the bundle to be untied, and gave a single rod to each of his sons, at the same time bidding them to try and break it; which when each did with all imaginable ease, the father addressed them to this effect. O my sons, behold the power of unity: for if you in like manner, would but keep yourselves strictly conjoined in the bonds of friendship, it could not be in the power of any mortal to hurt you; but when once the ties of brotherly affection are dissolved, how soon do you fall to pieces, and are liable to be violated by every injurious hand that assaults you!

THE APPLICATION.

Nothing is more necessary towards completing and continuing the well-being of mankind, than their entering into and preserving friendships and alliances. The safety of government depends chiefly upon this; and therefore it is weakened and exposed to its enemies in proportion as it is divided by parties. A kingdom divided against itself is brought to desolation. And the same holds good among all societies and corporations of men, from the great constitution of the nation down to every little parochial vestry. But the necessity of friendship extends itself to all sorts of resolutions in life; as it conduces mightily to the advantage of particular clans and families. Those of the same blood and lineage have a natural disposition to unite together, which they ought, by all means, to cultivate and improve. It must be a great comfort to people, when they fall under any calamity, to know that there are many others who sympathise with them; a great load of grief is mightily lessened when it is parcelled out into many shares. And then joy, in all our passions, loves to be communicative, and generally increases in proportion to the number of those who partake of it with us. We defy the threats and malice of an enemy, when we are assured that he cannot attack us single, but must encounter a bundle of allies at the same time. But they that behave themselves so, as to have few or no friends in the world, live in a perpetual fear and jealousy of mankind, because they are sensible of their own weakness, and know themselves liable to be crushed or broken to pieces by the first aggressor.

FAB. CXLVIII. The Falconer and the Partridge.↩

|

A Falconer having taken a Partridge in his nets, the bird begged hard for a reprieve, and promised the man, if he would let him go, to decoy other Partridges into his net. No, replies the Falconer, I was before determined not to spare you, but now you have condemned yourself by your own words; for he who is such a scoundrel, as to offer to betray his friends, to save himself, deserves, if possible, worse than death.

THE APPLICATION.

However convenient it may be for us to like the treason, yet we must be very destitute of honour, not to hate and abominate [269] the traitor. And accordingly, history furnishes us with many instances of kings and great men, who have punished the actors of treachery with death, though the part they acted has been so conducive to their interests, as to give them a victory or perhaps the quiet possession of a throne.

Nor can princes pursue a more just maxim than this; for a traitor is a villain of no principle, that sticks at nothing to promote his own selfish ends: he that betrays one cause for a great sum of money, will betray another upon the same account; and therefore it must be very impolitic in a state to suffer such wretches to live in it.

Since then this maxim is so good, and so likely at all times to be practised, what stupid rogues must they be, who undertake such precarious dirty work! If they miscarry, it generally proves fatal to them from one side or other; if they succeed, perhaps they may have the promised reward, but are sure to be detested, if suffered to live, by the very person that employs them.

FAB. CL. The Peacock and the Magpie.↩

|

The birds met together upon a time, to choose a king. And the Peacock standing candidate, displayed his gaudy plumes, and catched the eyes of the silly multitude with the richness of his feathers. The majority declared for him, and clapped their wings with great applause. But, just as they were going to proclaim him, the Magpie stepped forth in the midst of the assembly, and addressed himself thus to the new king: may it please your majesty elect, to permit one of your unworthy subjects to represent to you his suspicions and apprehensions, in the face of this whole congregation; we have chosen you for our king, we have put our lives and fortunes into your hands, and our whole hope and dependence is upon you: if therefore, the Eagle, the Vulture, or the Kite, should at any time make a descent upon us, as it is highly probable they will, may your majesty be so [273] gracious as to dispel our fears, and clear our doubts about that matter, by letting us know how you intend to defend us against them? This pithy unanswerable question, drew the whole audience into so just a reflection, that they soon resolved to proceed to a new choice. But, from that time, the Peacock has been looked upon as a vain insignificant pretender, and the Magpie esteemed as eminent a speaker as any among the whole community of birds.

THE APPLICATION.

Form and outside, in the choice of a ruler, should not be so much regarded, as the qualities and endowments of the mind. In choosing heads of corporations, from the king of the land, down to the master of a company, upon every new election, it should be inquired into, which of the candidates is most capable of advancing the good and welfare of the community; and upon him the choice should fall. But the eyes of the multitude are so dazzled with pomp and show, noise and ceremony, that they cannot see things really as they are; and from hence it comes to pass, that so many absurdities are committed and maintained in the world. People should examine and weigh the real worth and merit of the person, and not be imposed upon by false colours and pretences, of I know not what.

FAB. CLVIII. The Trumpeter taken Prisoner.↩

|

A Trumpeter being taken prisoner, in a battle, begged hard for quarters, declaring his innocence, and protesting, that he neither had, nor could kill any man, bearing no arms but only his trumpet, which he was obliged to sound at the word of command. For that reason, replied his enemies, are we determined not to spare you; for though you yourself never fight, yet with that wicked instrument of yours, you blow up animosity between other people, and so are the occasion of much bloodshed.

THE APPLICATION.

A man may be guilty of murder, who has never handled a sword, or pulled a trigger, or lifted up his arm with any mischievous weapon. There is a little incendiary, called the tongue, which is more venomous than a poisoned arrow, and more killing than a two-edged sword. The moral of the fable therefore is this, that if in any civil insurrection, the persons taken in arms against the government deserves to die, much [287] more do they, whose devilish tongues give birth to the sedition, and excited the tumult. When wicked priests, instead of preaching peace and charity, employ that engine of scandal, their tongues, to foment rebellions, whether they succeed in their designs or not, they ought to be severely punished; for they have done what in them lay, to set folks together by the ears; they have blown the trumpet, and sounded the alarm; and if thousands are not destroyed by the sword, it is none of their fault.

FAB. CLXI. The Wolves and the Sheep.↩

|

The Wolves and the Sheep had been a long time in a state of war together. At last a cessation of arms was proposed, in order to a treaty of peace, and hostages were to be delivered on both sides for security. The Wolves proposed that the Sheep should give up their dogs on the one side; and that they would deliver up their young ones on the other. This proposal was agreed to; but no sooner executed, than the young Wolves began to howl for want of their dams. The old ones took this opportunity to cry out, ' the treaty was broke;' and so falling upon the Sheep, who were destitute of their faithful guardians, the dogs, they worried and devoured them without control.

THE APPLICATION.

In all our transactions with mankind, even in the most private and low life, we should have a special regard how, and with whom we trust ourselves. Men, in this respect, ought to look [292] upon each other as wolves, and to keep themselves under a secure guard, and in a continual posture of defence. Particularly, upon any treaties of importance, the securities on both sides should be strictly considered; and each should act with so cautious a view to their own interest, as never to pledge or part with that which is the very essence and basis of their safety and well being.

And if this be a just and reasonable rule for men to govern themselves by, in their own private affairs, how much more fitting and necessary is it in any conjuncture wherein the public is concerned? If the enemy should demand our whole army for a hostage, the danger in our complying with it would be so gross and apparent, that we could not help observing it; but perhaps a country may equally expose itself by parting with a particular town or general, as its whole army; its safety not seldom depending as much upon one of the former, as upon the latter. In short, hostages and securities may be something very dear to us, but ought never to be given up, if our welfare and preservation have any dependence upon them.

FAB. CLXIV. The Horse and the loaded Ass.↩

|

An idle Horse, and an Ass labouring under a heavy burden, were travelling the road together: they both belonged to a country fellow, who trudged it on foot by them. The Ass, ready to faint under his heavy load, entreated the horse to assist him, and lighten his burden, by taking some of it upon his back. The horse was ill-natured, and refused to do it; upon which the poor Ass tumbled down in the midst of the high-way, and expired in an instant. The countryman ungirted his pack-saddle, and tried several ways to relieve him, but all to no purpose; which when he perceived, he took the whole burden and laid it upon the Horse, together with the skin of the dead Ass; so that the Horse, by his moroseness in refusing to do a small kindness, justly brought upon himself a great inconvenience.

[297]

THE APPLICATION.

Self-love is no such ill principle, if it were but well and truly directed; for it is impossible, that any man should love himself to any purpose, who withdraws his assistance from his friends, or the public. Every government is to be considered as a body politic; and every man who lives in it, as a member of that body. Now, to carry on the allegory, no member can thrive better, than when they all jointly unite their endeavours to assist and improve the whole. If the head was to refuse its assistance in procuring food for the mouth, they must both starve and perish together. And when those, who are parties concerned in the same community, deny such assistance to each other, as the preservation of that community necessarily requires, their self-interestedness in that case, is ill-directed, and will have a quite contrary effect from what they intended. How many people are so senseless, as to think it hard that there should be any taxes in the nation! whereas, were there to be none indeed, those very people would be undone immediately. That little property they have, would be presently plundered by foreign or domestic enemies; and then they would be glad to contribute their quota even without an act of parliament. — The charges of supporting a government are necessary things, and easily supplied by a due and well proportioned contribution.

But, in a narrower and more confined view, to be ready to assist our friends upon all occasions, is not only good, as it is an act of humanity, but highly discreet, as it strengthens our interests, and gives us an opportunity of lightening the burden of life.

FAB. CLXV, The Bees, the Drones, and the Wasp.↩

|