William Godwin (Aesop), Fables Ancient and Modern (2nd ed. 1805)

|

|

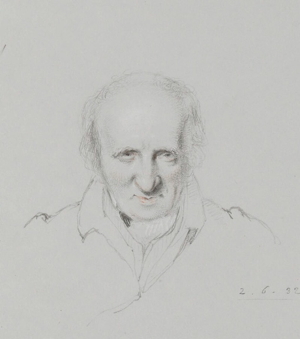

| William Godwin (1756-1836) |

Source

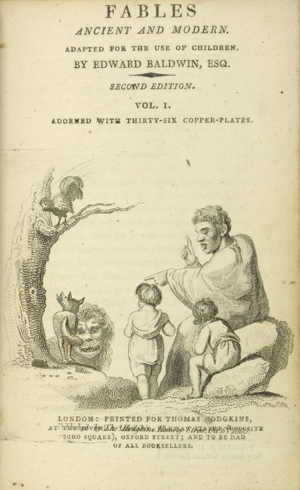

Fables Ancient and Modern. Adapted for the Use of Children from Three to Eight Years of Age. By Edward Baldwin, Esq. Published by Tho.s Hodgkins. Hanway Street, Oct.r 6. th 1805. London: Printed for Thomas Hodgkins, At the JUVENILE LIBRARY, Hanway Street (Opposite Soho Square), Oxford Street; and to be had of all Booksellers. [Second Edition.] Vol. I. Adorned with Thirty-six Copper-Plates. Vol. II Adorned with Thirty-seven Copper-Plates. [by William Mulready]. Printed by B. McMillan, Bow Street, Covent Garden

Editor's Note: The HTML and images come from “Romantic Circles” at the University of Colorado, Boulder, eds. Paul Youngquist and Orrin N.C. Wang. I have not been able to find a facs. PDF version of this edition but I have checked it against the one volume 4th edition of 1808. [facs. PDF]

Table of Contents

CONTENTS OF VOL. I.

- [Godwin's] Preface

- The Dog in the Manger

- The Shepherd's Boy and the Wolf

- The Grasshopper and the Ant

- The Hermit and the Bear

- The Fox and the Raven

- The Fox and the Stork

- The Stag Drinking

- The Travellers and the Money-Bag

- The Miller, his Son, and his Ass

- The Town Mouse and the Country Mouse

- The Miser and his Treasure

- The Fox and Grapes

- The Lion and the Mouse

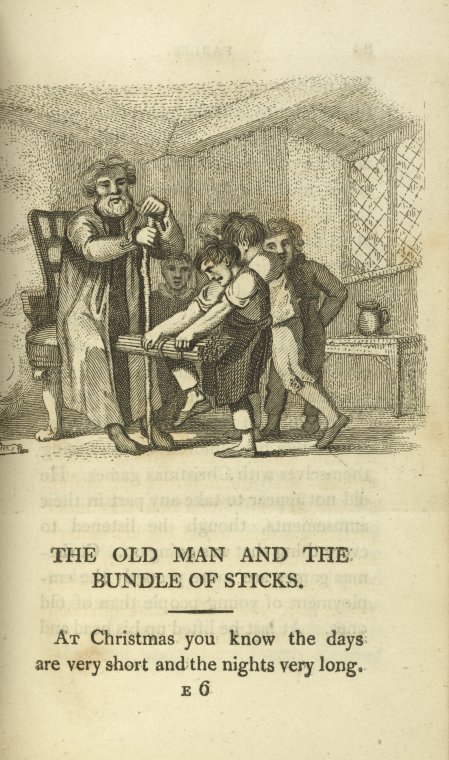

- The Old Man and the Bundle of Sticks

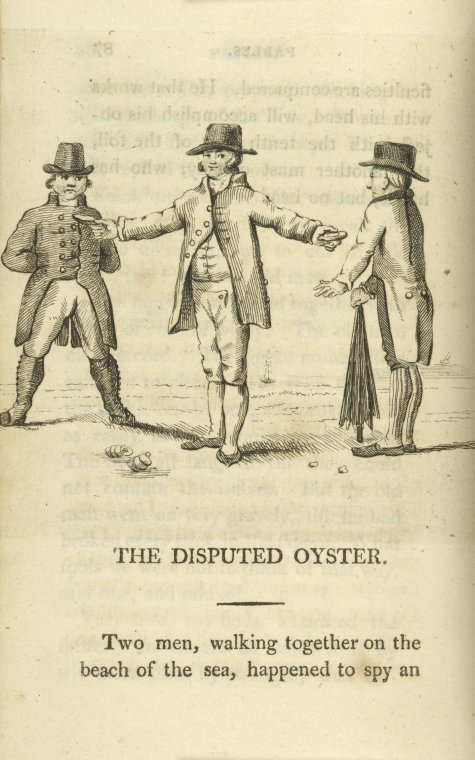

- The Disputed Oyster

- The Goose with Golden Eggs

- The Boys and the Frogs

- The Mice in Council

- The Country Maid and her Milk-Pail

- The Poor Farmer and the Justice

- The Ass in the Lion's Skin

- The Daw and Borrowed Feathers

- The Dog and the Shadow

- The Wolf and the Mastiff

- The Wolf and the Lamb

- The Mouse, the Cock, and the Cat

- The Fly in the Mail Coach

- The Belly and the Members

- The Sun and the Wind

- The Frog and the Ox

- The Horse and the Stag

- The Good-Natured Man and the Adder

- The Bear and the Bees

- The Horse-Dung and the Apples

- The Lion and other Beasts Hunting

CONTENTS OF VOL. II.

- The Lion and the Man

- The Fox and the Mask

- The Leap in Rhodes

- The Cock and the Precious Stone

- The Mountain in Labour

- The Oak and the Reed

- The Fox without a Tail

- The Waggoner and Hercules

- The Grass-Green Cat

- The Weasel in the Granary

- Washing the Blackamoor White

- Industry and Sloth

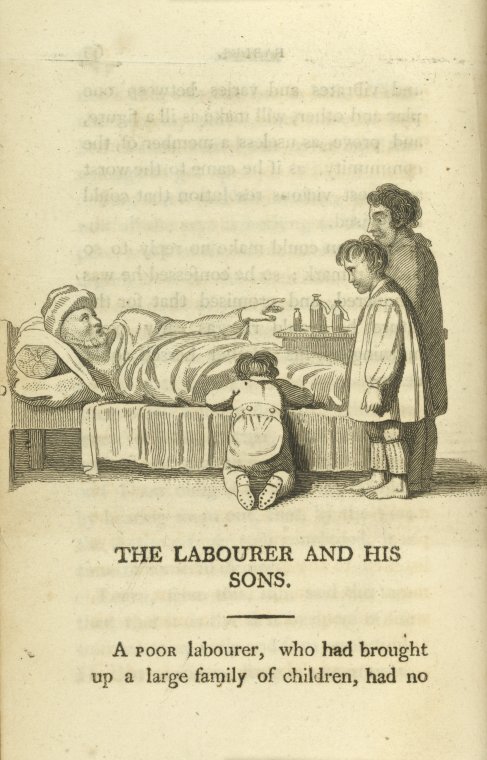

- The Labourer and his Sons

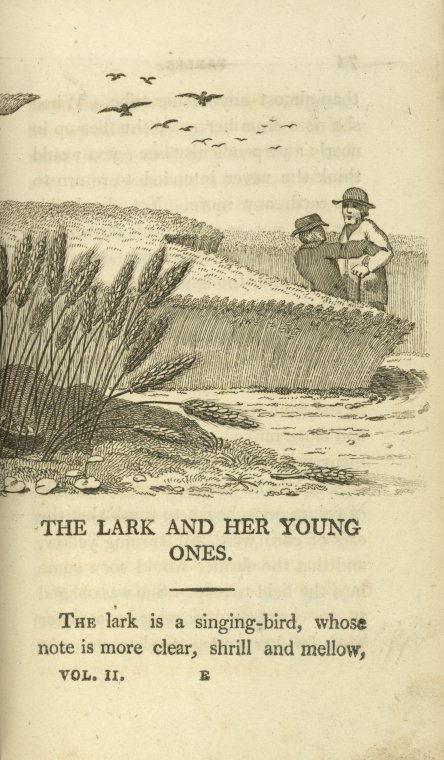

- The Lark and her Young Ones

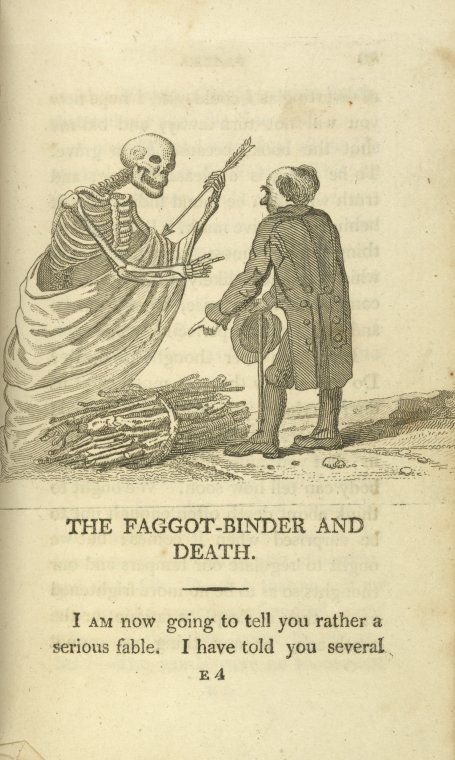

- The Faggot-Binder and Death

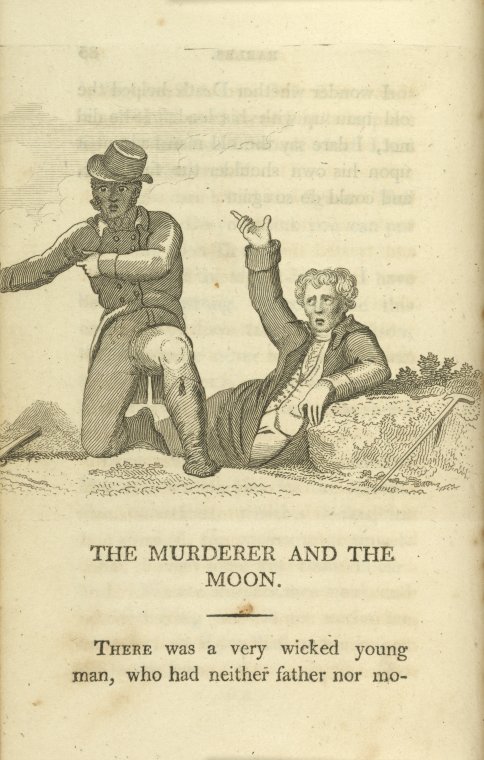

- The Murderer and the Moon

- The Ass and the Lap-dog

- The Satyr and the Traveller

- The Ape and her Cubs

- The Two Jars

- The Crab and her Daughter

- The Travellers and the Bear

- Ignoramus and the Student

- The Young Man and the Lion

- The Eagle and the Crow

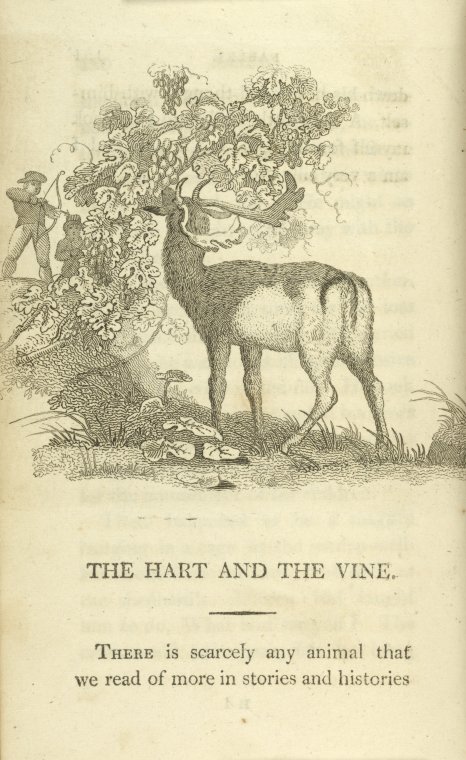

- The Hart and the Vine

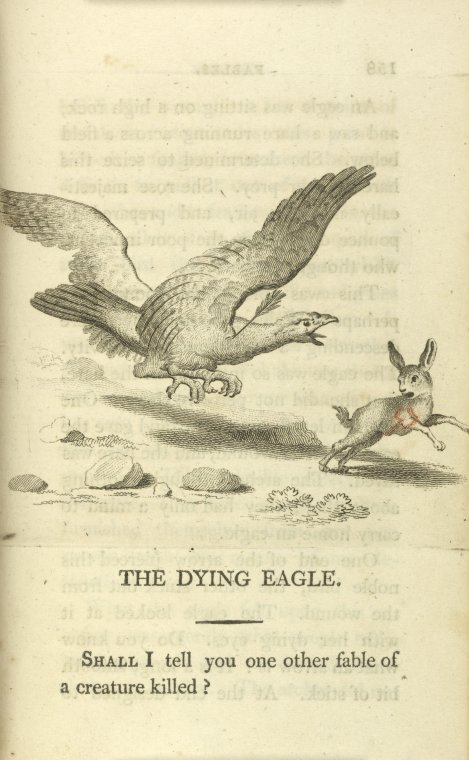

- The Dying Eagle

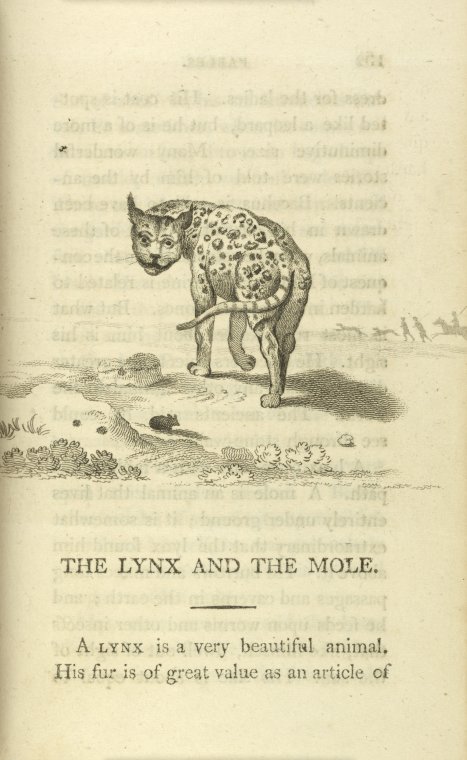

- The Lynx and the Mole

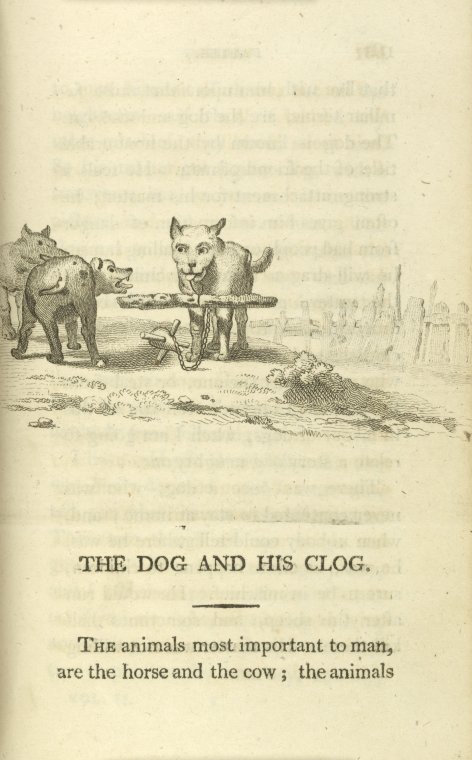

- The Dog and his Clog

- The Lion and the Gad-fly

- The Astrologer in a Pit

- The Herdsman and Jupiter

- The Old Woman and her Maids

- The Cock and the Fox

- The Lion, the Cock, and the Ass

- The Contractor and the Cobbler

Preface.↩

There are two or three features that I have aimed to bestow upon these fables, by which they might be distinguished from the generality of fables I have seen; and, as every author has not the skill to make his intention visible, and every reader is not a reader of penetration, I will briefly mention what these features are.

I have long thought that fables were the happiest vehicle which could be devised for the instruction of children in the first period of their education. The stories are short; a simple and familiar turn of incident runs through them; and the mediums of instruction they employ are animals, some of the first objects with which the eyes and the curiosity of children are conversant. Yet these advantages are too often defeated by the manner in which fables are written, and in which they are read.

They are written in too simple a form. Too simple in language and sentiments they cannot be. But many fables in the commonest books of this sort are dismissed in five or six lines. This is wrong; it is not thus that children are instructed. If we would benefit a child, we must become in part a child ourselves. We must prattle to him; we must expatiate upon some points; we must introduce quick, unexpected turns, which, if they are not wit, have the effect of wit to children. Above all, we must make our narrations pictures, and render the objects we discourse about, visible to the fancy of the learner. A tale which is compressed, dry, and told in as few words as a problem in Euclid, will never prove interesting to the mind of a child.

In the present volumes I have uniformly represented myself to my own thoughts as relating the several stories to a child. I have fancied myself taking the child upon my knee, and have expressed them in such language as I should have been likely to employ, when I wished to amuse the child, and make what I was talking of take hold upon his attention.

Half the fables which are to be found in the ordinary books end unhappily, or end in an abrupt and unsatisfactory manner. This is what a child does not like. The first question he asks, when he has finished his reading, if he is at all interested in the tale, is, What became of the poor dog, the fox, or the wolf? While the stories were told with the customary dryness, this was not of much importance; but, the moment a character of reality was given to the narrative, it cried aloud for correction. I have accordingly endeavoured to make almost all my narratives end in a happy and forgiving tone, in that tone of mind which I would wish to cultivate in my child.

Lastly, in the ordinary fable-books every object, be it a wolf, a stag, a country-fair, a Heathen God, or the grim spectre of Death, is introduced abruptly: and, as few parents, and fewer governesses, are inclined to interrupt their lessons with dialogue, and enter into explanations, the child is early taught to receive and repeat words which convey no specific idea to his mind. I have endeavoured never to forget, that the book I was writing, was to be the first, or nearly the first, book offered to the child's attention. I have introduced no leading object without a clear and distinct explanation. By this means the little reader will be accustomed to form clear and distinct ideas. By this means my book is made a compendium of the most familiar points of natural history and the knowledge of life, without being subjected to the discouraging arrangements of a book of science. I have intended, as far as I was able, that these volumes should surpass most others in forming the mind of the learner to habits of meditation and reflection.

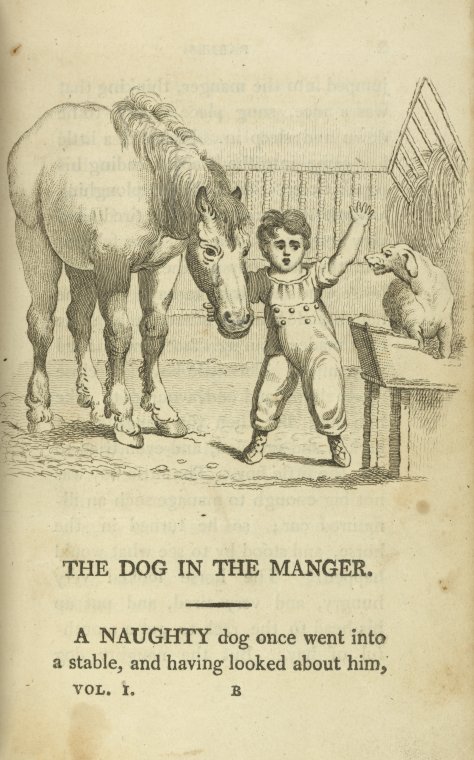

THE DOG IN THE MANGER. ↩

A naughty dog once went into a stable, and having looked about him, jumped into the manger, thinking that was a nice, snug place for him to lie down and sleep in. Presently a little boy came into the stable, leading his papa's horse, that had been ploughing a whole field, and was very tired, and very hungry. Come out, poor fellow! said the little boy to the dog, papa's horse wants to eat some hay. But the naughty dog never stirred a bit; he only made up an ugly face, and snarled very much. The little boy went close up to him, and endeavoured to take him out; but then the naughty dog barked and growled, and even tried to bite the little boy. The little boy was not big enough to manage such an ill-natured cur; so he turned in the horse, and stood by to see what would happen. The horse looked very hungry, and very tired, and put up his head to the rack to get a mouthful of hay. But the naughty dog snapped at the poor horse's mouth. The horse was very sorry, and would have said, Pray dog, let me eat! if he had been able. But the naughty dog did not care. You silly dog, said the little boy, hay is of no use to you, dogs do not eat hay, though horses do; and if you stay there, you will soon be as hungry as papa's horse. So the dog staid a long while, and by and by he grew hungry, and came to the little boy, and begged for meat. Silly dog, says the little boy, if I were as naughty as you, I should give you nothing to eat, as you prevented papa's horse from eating. There is a plate of meat for you; and remember another time, that only naughty dogs, and naughty boys and girls, keep away from others what they cannot use themselves.

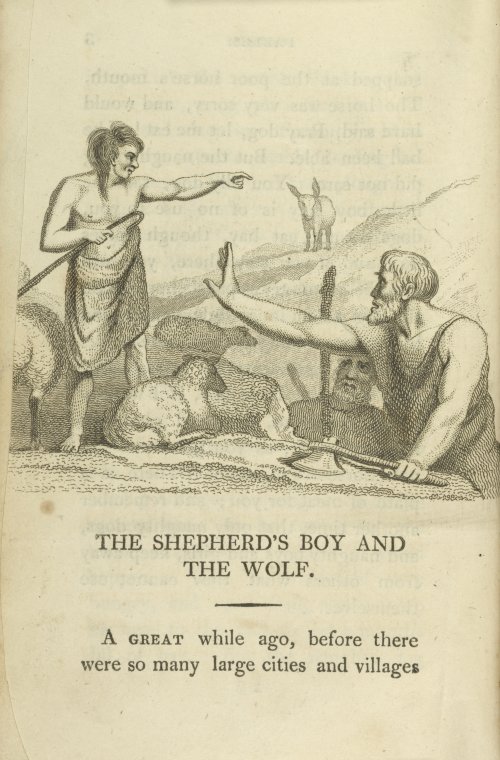

THE SHEPHERD'S BOY AND THE WOLF.↩

A Great while ago, before there were so many large cities and villages as there are now, all the countries in the world abounded with wild beasts. England in particular was full of wolves; and little boys and girls dared not walk abroad without somebody to take care of them, for fear the wolf should come and eat them up. In the times I am thinking of, nobody had invented a plough; so there was no corn. The wild men then kept sheep; they had mutton for their dinner, but neither turnips nor bread to eat with it. Men staid all day with the flocks, to take care that they did not lose themselves, and that the wolves did not come to eat them; for wolves were always very fond of mutton, and, when they were hungry, would come and kill a sheep or a little lamb for their dinner. A wolf had at any time rather have a lamb than a child. Sometimes when the men were very busy, mending the thatch, or cutting down fire-wood (for there were no coals and no tiles), they would send their children, boys of ten or twelve years old, like Charles, to take care of the flocks of sheep.

The boy I am going to tell you about, was a very naughty boy, and his father and mother could never make him do as he was bid. He was always laughing when he should have been minding his lesson; and he often did mischief and thought it a very good joke. Says his father to him one day, Winter will soon be here, and I must go to the forest and cut some fire-wood: you are hardly big enough yet to take care of the sheep, but I must trust you to look after them. That I will, father! says the boy, for he was proud to be of some importance. I and three or four of my neighbours, said the father, shall be within call, and if you want any help, you must bawl to us as lustily as you can.

Away went the boy, and took the sheep-dog with him, and drove the flock to pasture. He sat down upon a hillock to look at them; he patted his dog, and when any of the lambs straggled from the rest, he sent the dog to bark at them, and make them come back.

This was all very well; but presently he thought, Now I will have a joke. Every thing was quiet about him, when he set up a great scream, Father, father, the wolf, the wolf is coming. Away ran the father and the neighbours, leaving their work, some with sticks, and some with hatchets, to help the poor boy and drive away the wolf. When they came, all was quiet, and the boy burst into a great laugh, to think he had made a fool of his father. His father was very angry, and said, Child, how could you call us away from our work, and tell us a lie? I could not have thought it of you. But the naughty boy did not mind.

The next day the father went again to the forest, and sent his son to mind the sheep. Presently he began to cry, The wolf, the wolf! and every thing happened as before, except that his father was this time more angry, and told him he should go to bed without his supper. But the silly boy was still pleased with himself, that he had once more, as he called it, made a fool of his father.

It was now almost evening, and the sun began to set, when the naughty boy saw two great, fierce wolves running toward him as fast as they could. He was terribly frightened; and by ill luck the dog had gone after a rabbit or a bird, and could no where be seen. The boy screamed dismally: The wolf, the wolf, Oh father, the wolf! Then he ran to beat the wild beasts with his crook; but they scared him, and he ran back again. Then he screamed more and more. His father and the wood-cutters heard him plain enough, but they said, It is only that mischievous boy; he shall make fools of us no more. So the wolves ate up so many of the flock, that the father was ruined, and obliged to part with the rest, and go a-begging: and, when the boy grew up to be a man, people still pointed at him, and said, That is the son, that told lies, and ruined his father.

THE GRASSHOPPER AND THE ANT.↩

I have one thing to mention to you for fear of mistakes. Beasts and birds do not talk English; but they have a way of talking that they understand among one another, better than we understand them; and you, if you attend to your dog, or your cat, or your horse, may generally make out what he wants from his voice or his look. I am going sometimes to tell you what an animal says; that is, I am going to put his meaning into English words.

But let me say one thing more. It is not always necessary that a story should be true. Some stories are true, and some are invented; and, if they are very prettily invented, we are much obliged to the people that made them. A lie is what naughty folks say, that they may deceive; like the boy and the wolf. But, if I tell a pretty story of a dog and a fox, or any other animals, I do not mean to deceive, I only mean to tell a pretty story. Now then I begin.

An ant is a very wise, though a very little animal, and lays up food in the summer when there is plenty, against the winter when there is none. He is thoughtful and serious. A grasshopper is the merriest creature in the world; he sings all the summer long; but, when the winter comes, he dies of hunger and cold.

A grasshopper, as the story says, at the beginning of a hard winter, happened to meet an ant. The grasshopper was very hungry. He looked at the ant, as much as to say, You are a very wise animal, and have got a store-house full of corn. He then plucked up a spirit, and cried in a melancholy tone, Pray, Mr. Ant, give me a grain of your corn! That I will, said the ant, and fetched him a little. But do not come to me any more; perhaps you may find other charitable ants not far off another day. I have only enough to last my own family, who all helped in collecting it. Ants are very sorry to see other animals starve, but animals that can work for themselves, and will not, and, as the saying is, do not make hay while the sun shines, cannot always expect to have their idleness maintained by our industry. People will think much better of a creature that is sober and pains-taking in time, than of one that, for want of taking pains, is obliged to go a-begging.

THE HERMIT AND THE BEAR.↩

A very old man, who had lost his wife and all his children, took it into his head that he would go and live by himself in a cave, surrounded on all sides by a vast, desolate forest. He was a very good man, doing kindness to every body when he was able, and every body loved him. If a traveller lost his way in the forest, and was hungry, and weary, and benighted, the old man would give him part of his supper, and invite him to lodge in his cave. This good creature was kind even to animals; he would not hurt a spider; and in the winter the little robins came, and fed upon the crumbs of bread that he scattered for them at the mouth of his cave. They saw that he never hurt or frightened them, and they would pick out of his hand the biscuit he crumbled for their breakfast.

One day as this good hermit was taking a pleasant walk, he heard the groans of an animal in pain. He looked through the bushes, and saw a vast, overgrown bear stretched at the foot of a tree. At first he was rather alarmed; but, when he looked a little longer, he saw the bear was very ill. He then came round and showed himself; and the bear looked at him in a pitiful manner, and held up his foot. The hermit saw that it was very sore, and very much swelled. The poor creature had somehow got a hurt in it a week before, and it had grown worse and worse, till the bear could not walk. The bear could not go for victuals, and victuals did not come to the bear, so that he was in danger of being starved. The hermit took compassion on the animal; he ran and got water and washed his foot; he put a little balsam to it that he had in his pocket, and then fetched him something to eat. He now visited the bear every day, till he was well enough to walk.

The first walk the bear took, he would go home with the hermit. The old man did not much like it; he would have been better pleased with a dog for his companion; but the bear did it all out of love. When they came home, the bear would stay and live with the hermit. Bears are clever animals, and can do many tricks; though naughty people use them very cruelly, pretending to teach them to dance. Particularly they can climb trees. The hermit was feeble and stiff of his limbs, and could not do that; so this bear climbed trees for him, and shook the boughs, and made the apples and chestnuts fall for the old man's supper.

One day the hermit had taken a longer walk than usual in a very hot sun, and after dinner he laid him down near his cave and fell asleep. The bear, as usual, watched close by him to take care of him. As the weather was sultry, the flies came about the hermit, and lighted on his face, and tickled him. The old man shook his head, but did not awake: the bear growled, but the hermit was in a sound sleep, and the flies did not care for his growlings. At last one saucy fly pitched upon the old man's nose. Now, thought the bear, I shall have you; and with that he took up his paw to give the fly a good knock. The fly was killed; but the poor hermit's nose was terribly bruised, and after a time turned quite black. Immediately the hermit awoke, and began to be very angry; but he put up his hand to his nose, and the dead fly fell upon it: he then knew what the bear had been doing. Go, go, said he to the bear, shaking his head with the pain; I will always do you all the good I can, but we will not live together any more. He that admits into his company an awkward and ill-matched favourite, will sometime or other have reason to grieve, even for things that were intended in kindness.

THE FOX AND THE RAVEN.↩

There are a great many fables about foxes. A fox is a little animal, hardly so big as a middle-sized dog. He lives in the woods, and is never tamed. He is very fond of fowls and geese, and steals them, whenever he can, for his dinner. The farmers therefore are his great enemies; for they do not like, when they have been at the trouble and expense of breeding the poultry, that the fox should come and eat them up. The fox however is a cunning little fellow; he is full of stratagems and wiles; and when we speak of any body that is very sly, it is usual to say, He is as cunning as a fox.

A fox, as Esop says, happened one day to be very hungry. He was walking along quite serious, for people are apt to be serious when they are hungry. He spied a raven perched in a tree, with a delicate cheese in his beak. I suppose this cheese must have been about the size of a baked apple; I believe they make such in some countries.

The fox thought with himself, I dare say that is a very nice cheese; I wish I could taste it. But what could he do? The raven sat upon a high branch; the fox did not know how to climb to him. If the raven would consent to fight for the cheese, the fox perhaps could have beaten him. But, suppose the raven had been upon the ground, he had fine large wings and could have flown away with the cheese.

While the fox was thinking thus, he fixed his eyes on the raven. What a beautiful bird you are! says he. I never saw any thing so glossy as your shining, black feathers. What a twist you have with your neck! And what a noble beak! I dare say it holds that cheese as tight as if it was a pair of pincers. Do you know that I think you the finest bird I ever saw; and, if your singing is but equal to the manner in which you hold yourself, the nightingale must be nothing to you.

Now you must know that the only noise a raven can make is as frightful a scream as you every heard. Whenever he begins, I am always disposed to put my fingers to my ears. But this silly bird was delighted with the fine speeches of the fox; he knew that his feathers were as black as the cunning creature said, and that he had a good, handsome beak of his own; and he began to think that perhaps he might be a fine singer too. So he tuned his pipes to try; the cheese dropt out of his beak; this was all the fox wanted; he caught it up, and ran away with it, and left the raven to sing to the crows.

Foxes are never taught what is good and what is naughty. But, if I were a little boy or a little girl, I would rather go without cheese all the days of my life, than gain it by such cheating and wicked speeches as this fox is said to have made.

THE FOX AND THE STORK.↩

A fox one day invited a stork to dinner. The good-natured stork was pleased with the civility, and had no doubt that the invitation was meant in kindness. But the fox intended no such thing; he had nothing in his head but the hope to make game of an animal, who, though of a remarkably sweet temper, he thought was not so wise as himself.

The dinner consisted of a fine, rich soup; for foxes and storks never want but one dish to a meal. The fox set it before his guest in a very broad platter, so that, though there was enough of it, it was hardly more than half an inch deep.

To understand the fox's joke, you must consider the different ways that beasts and birds have of taking their food, and particularly what is liquid. Beasts have a long tongue; look at the cat when she is drinking her milk; she puts out her tongue, and laps it up in a minute. It is very droll; you could not drink your milk as she does. Birds on the contrary have a long bill that they put into the cup, and suck up as much as they want. Neither beasts nor birds drink as little boys and girls do.

The soup was set smoking before them; it had a fine savoury smell; and, if the stork was sharp-set before, the smell now gave strength to his appetite. He put in his bill, and the fox put in his tongue; but the soup was so shallow, that the stork could scarcely suck up any thing. The fox however found himself very well off, and swallowed it all in less than a minute. Then they parted with many civilities, and the fox said, he hoped he should soon have the pleasure to see the stork again.

The stork did not care much about the dinner; his home was not far off; he had plenty there; and, spreading his wings, he soon got to a place where he could fully make up his disappointment. But he was sorry to see any animal capable of so ill-natured a joke. In spite of all his good temper, he was a little angry; and he determined to show his inviter, that foxes are not more cunning than other animals, if they would condescend to play such pitiful tricks.

The next day the stork met the fox. Come, my friend, said the stork, yesterday I dined with you; you must do me the pleasure to eat your mutton with me to-day. The fox consented; he apprehended no trick; he said to himself, Such a good-natured creature as the stork would not ask me, if he had not something nice to treat me with.

The stork's dinner was meat, minced very fine, and put into a long narrow-necked bottle. I beg, friend, says the stork, you will stand upon no ceremony with me; I hope you will make as free as if you were at home. Saying this, he put his long beak into the bottle, and quietly began his dinner. The fox did not know what to make of it; at first he licked the gravy and the little morsels that ran down the side of the bottle; at last he began to grow angry. He said, this was not usage for a gentleman, and he would take care to remember it another time.

I hope then, said the stork, you will remember also the dinner you gave me yesterday; I would not punish you too severely; you may go without your dinner for one day, and never be starved. Remember too this maxim, which you will find has a great deal of good sense in it, He that cannot take a joke, should never have the assurance to make one.

THE STAG DRINKING.↩

You have heard, I dare say, how fond some gentlemen are of riding a hunting, and what a fine sport they think it is. For my part, I could never quite reconcile myself to the idea of such sport. There is hare-hunting, and fox-hunting, and deer-hunting, beside the hunting of lions and tigers and other ferocious animals. I think more has been said about deer-hunting, than any of the rest; and there is a fine old song upon that subject, called Chevy-Chase. The way is for the gentlemen, very early in the morning, to mount upon a number of fine horses, which for their fleetness are called hunters, and to call out a pack of dogs bred for the purpose, that are to run after the deer, and that will, when they have caught it, tear it almost to pieces, if the gentlemen do not interfere. As soon as the gentlemen have all got on their horses, the huntsman, or groom, blows his horn, and away they ride. When they come to a field, or a proper place, the huntsman makes the hounds smell all about, till they find the smell of the deer. At this time of the morning, the grass is covered with dew, which the hounds brush away, as they run. When they have roused the deer, the poor creature is terribly frightened, and sets off as hard as he can, and the dogs after him, and the gentlemen after the dogs. The deer sometimes runs forward, and sometimes almost back again, that he may get rid of his pursuers; but the dogs follow him by the smell he leaves on the grass, and wind backward and forward just as he does. Sometimes he takes a great jump to break the line of the smell, and sometimes he swims across a river. After some hours running he is generally caught at last. Poor deer! The flesh of deer is called venison, and is thought to be much better than beef and mutton.

For my part, I do not quite like this hunting the deer. Do not you think it very cruel, to call the frightening a poor creature, and at last perhaps killing him, fine sport? The deer is a beautiful animal. The male is called a stag, and has grand, branching horns. The female is called a hind; she has no horns, but is a very handsome, innocent-looking creature. The young deer is called a fawn, and is so pretty and good-natured, that ladies formerly would call the fawns to come and lie down in their chambers. The coat of the deer is of a beautiful brown, sometimes a little reddish, sometimes speckled and mottled with white, and, when the animal is in health, is as smooth as velvet.

A stag once, who had lived free and happy in the forest where he was born, after having frisked about, and eaten his dinner of grass, wanted to drink. There was a pretty running stream not far off, as smooth and as clear as glass. The stag knew this stream very well, and had often tasted its sweet, cool waters. While he was drinking, he could not help seeing himself in the stream; and, when he had done, he stopped a little longer, to admire his own face, just as I have seen little girls admire themselves in a glass. He nodded his head. I declare, said the stag to himself, I think I am very pretty: my eyes are so bright, and my nose is so small and slender! But above all, these fine branching horns, what a grace they have! I do not wonder that all the young hinds should fall in love with me, and wish me for a husband. Yet I am surprised they dare to be so familiar with so noble a creature, and lick my neck with their tongues, as they do sometimes.

The stag then began to look a little further. And yet, thought he, I do not half like these legs. They are so slender and insignificant! They look like four spindles. What a creature should I have been, if these pitiful shanks of mine had been answerable to the majesty of my horns!

The stag staid so long, considering and commenting upon his different parts and members, that at last he heard the cry of the hounds. I do not know whether he had ever heard it before; but animals seem from the first to know who are their enemies. The little mouse ran away the very first time she saw a cat.

Away started the stag, and most gloriously he scampered. He ran faster than the dogs. After all, thought he, these legs are not such bad things. If they are thin and light, they seem on that account only to carry me the faster. Thinking thus, he still ran as hard as he could, up hill and down dale, across the high road, then into a turnip-field, and next over a meadow. At last he came to a wood; and, trying to force his way through it, he entangled his horns so among the bushes, that he could not get free. The hounds came up: but the gentlemen were close by, and generously saved him from being mangled and killed, as he otherwise would have been.

Well, thought the stag, when he saw himself safe, I have learned a lesson to day, that I shall remember as long as I live. Another time, when I undertake the decide upon the value of a thing, I will consider, not merely whether it looks beautiful, but what use is to be got from it. I now know that swift legs are more worth having, than the most magnificent horns that ever were seen.

THE TRAVELLERS AND THE MONEY-BAG.↩

Two poor men set off at the same time from Scotland to come to London. They found little employment at home, and they had heard that their trade met with better encouragement in the capital. They had very, very little money, and were obliged to go all the way on foot. As they were both going to the same place, they thought they might as well be company for each other.

These poor men knew very little of each other before their journey. But they said, we are men, and men ought to lend a helping hand to one another. If we have nothing but bread and cheese to eat, it will be pleasant to sit together and eat it under the same hedge. If we sleep upon straw, it will be delightful to say, Good-night, Good-night, before we close our eyes, and, Up, fellow-traveller, and be stirring, when we wake in the morning. One said, I can whistle a number of good songs; and the other answered, Though I cannot whistle, I know many pretty stories, some that will make you laugh heartily, and some that will almost make you cry. This was all the bargain they made, and then they set out.

Nothing very particular happened the two first days, except that, as it is almost impossible to travel without money, the little they had at first, was now grown less. On the third day they were almost come to York. It was quite dark, when one of them stumbled over something in the road, and taking it up, found it was a canvas money-bag, or farmer's purse. It was heavy with money. The one who took it up was an ill-natured, selfish fellow, that always wanted to keep every thing that was good to himself. Aha! said he, I am in luck to-day; I have found a purse of money. Just then they passed a cottage with a light in the window. Let me see, said the finder, going close to the window, and looking at the money—four, five, six guineas, and nineteen shillings, and I dare say a matter of five-shillings-worth of half-pence. I declare I have a great mind to buy a little horse, and ride the rest of the way by myself.

Friend, said his companion, you ought not to have said, I have found a purse of money, but We have found it. I am sure you know it is a rule among poor people when they travel together, to call any thing they find in the road a God-send, and share it equally between them.

You may think as you please, said the other; but I shall not part with a farthing of it. I will buy a horse as soon as we get into York; and shall mount my nag to-morrow morning, and wish you a very pleasant walk from York to London.

He that did not find the purse was now ready to cry, not so much on account of the money, though that would have been very acceptable to him,—as for vexation to think that a fellow-countryman and fellow-traveller could be so selfish and ill-natured. He had not time to cry however, when they heard three or four horsemen coming along the road, riding pretty fast, and yet talking very earnestly. They listened to the talk, and found the horsemen were speaking of a farmer who had been robbed by highwaymen as he went home from York-market, and had lost his purse, containing six guineas, and nineteen shillings in silver, and five-shillings-worth of half-pence.

Come along, said the selfish traveller, all in a sweat, to his companion, let us turn into this wood, and hide ourselves. If they find us with the purse in our possession, they will think we are the thieves, and we shall be hanged.

I shall do no such thing, said the other; these people want to return it to the right owner, and the right owner must have it. Besides, you are no longer a fit fellow-traveller for me. You would not allow me to say, We have found a purse, when you thought nobody would claim it, and I do not understand your saying, We shall be hanged, when pursuit is made after the thief.

The horsemen, though they could not see the travellers, heard their voices, and called to them to stop. They did so, and were questioned, and obliged to deliver up the purse. It would have gone still harder with the selfish traveller, who trembled and stammered so much, that they thought he was the thief; but his generous companion, who had intended no harm, told a plain, honest story, that convinced the horsemen, who in consequence dismissed them both. I am glad, said he, to have done you this service: we are now almost at the gates of York; I shall therefore only bid you good night, and wish you to-morrow, as you intended to do by me, a very pleasant walk from York to London.

THE MILLER, HIS SON, AND HIS ASS.↩

What a pretty thing is a village fair! It happens but once a year, and the young lads and lasses all come there in their best clothes. There are two or three streets of booths, slightly put together of boards for the occasion, that are taken down and carried away, as soon as the fair is over. It lasts sometimes one day; sometimes two: two is quite enough. These booths are hung with ribbands, and cloaks, and silk-handkerchiefs for sale. Upon the table of the booth are laid knives, and scissars, and snuff-boxes, and boxes of Tunbridge-ware, and dolls, and drums, and fifes, and flutes, and fiddles, and Jew-harps, and rattles, and pretty pictures, and children's books, and sugar-plums, and ginger-bread, and oranges, and nuts, and apples. Johnny buys Betty a fine taudry ribband to tie round her cap. Whatever one person buys, and gives to another, is called a fairing. Then the fair is crowded with pretty clean boys and girls. They beat the drums, and squeak with the flutes; and there is such a noise, you cannot think how much. Every body is in a hurry, and busy, and happy. When I was a little boy, I remember I thought I never saw so charming and happy a place as a village-fair.

But every body does not come to the fair for amusement; some people have very serious business. The buyers are amused with their purchases; but the sellers are very grave, thinking how much money they shall carry home to buy beef and mutton for their wives and children. The serving-men and serving-maids come to hire themselves: servants in the country always hire themselves for a year, till next fair-time, at the least; and a very good servant loves his master as much as if he were his father, and is as unwilling to go away from him. Then there is a field, not far from the booths, where horses are bought and sold, and sometimes cows, and asses, and sheep.

A miller once set off for a village-fair, about four miles from his mill, to sell his ass. I am afraid this miller had grown poor, else I do not think he would have sold his ass. The miller was an old man with white hairs, that walked along leaning on a stick. He took with him his son, a pretty little boy, about seven years old, who had a great desire to see the fair, and his father told him that, if he sold his ass well, the little boy should bring home a drum.

Away they went; the miller very thoughtful and very serious, for he was a seller; the boy, as merry as a cricket, kissed his father's hand, and thanked him a thousand times for being so good as to take him to the fair. But, Charley, my boy, said the miller, you must walk all the way: I am an old man, and cannot get along without a stick, and yet I shall walk: You were seven years old last birth-day. If we fatigue our ass with riding upon him, he will not look handsome, and people will not believe he is so good an ass as we have found him to be. We will rest for an hour or two on the grass, and have a little bread and cheese and ale, before we set off to come home again.

Oh, father, says the little boy, I am sure I can walk very well; and, if I find myself a little tired in coming home, I will beat upon my new drum, and the sound of that will make me as fresh as if I had not moved a step.

So they went along to the fair. Many people were going the same road to the same place, some on horses, some in carts, and even those on foot, most of them, walked faster than the old miller and his little son. These people were very merry; and some of them, as merry people are apt to be, a little impertinent.

What fools are that old man and his son, said one, to walk on foot, when they have an ass so well able to carry one or the other!

The miller was very good-natured, and not willing that any body should be displeased with what he did. He was a little afraid before, poor man, whether Charley would be able to hold out. So he took up the little boy in his hand, and set him on the ass; and Charley was not at bottom displeased with the change, though he was a very good boy, and cheerfully walked a-foot, when his father bid him.

By and by three jolly farmers rode by. They stopped to look at the travellers. Why, you lazy little urchin, said one of them, are not you ashamed to be riding at your ease, while your poor old father trudges by your side?

This speech made poor Charley feel very uncomfortable. He had always been a dutiful child, and could not bear to have it thought otherwise. He began almost to cry. He slid down from the ass as fast as he could, and said, Pray, pray, father, do you ride, and let me walk. The miller did not like that any body should form an ill opinion of Charley, and consented.

The next party that came up was three farmers' wives. What a pretty boy! said one of them. A little weakly or so, but that only makes him look more delicate and interesting. I am afraid one of his feet is hurt with walking; look if he does not go a little lame! What a brute of a man must his father be, to jog on at his ease, and make this sweet child limp after him as well as he can! The miller heard, and changed his plan. Come, Charley, said he, we will both ride; I hope ever body will think that right.

The next man that came meant I believe to play the rogue. He had heard what the others had said, and smiled to see the good-natured pains the miller took to please every body. Pray, friend, said he to the father, is that ass your own? One would think not by the unmerciful way in which you load him. But, I suppose, you expect to kill him by the journey, and to sell his skin at the fair to make pocket-books.

The miller had tried almost all the schemes he could think of, and had not been able to pass along without being jeered at. At last he thought of one more. He pulled a large stake out of the hedge; he got a rope, and tied the ass's feet, two and two, together, and made them fast to the stake. Now, Charley, said he, as the ass must not carry us, let us try to carry the ass. I confess this was a very silly scheme; but what could the poor miller do? Charley could hardly lift his end of the pole. Ha! ha! ha! Hoh! hoh! hoh! said the people, this is the strangest sight we ever saw.

All this passed just by a bridge. Before they had got two steps upon the bridge, the ass was frightened with the noise, and struggled very much; Charley lost his hold; and the ass fell into the water. It was well for the poor creature that they had not got to the middle of the bridge; otherwise, with his legs tied together, he could not have helped himself, and must infallibly have been drowned.

Come, Charley, said the old man, I see what a foolish mistake I have made. We ought to listen to the opinions of such as have a great deal of kindness and a great deal of sense to advise us, but not to the gabble of people who perhaps make their silly remarks only in hopes to vex the passers-by.

So they went on to the fair in the same manner that they had set out. If people laughed or jeered, the miller took no notice, but quietly kept on his way. Conducting himself thus, he speedily sold his ass; and Charley came home with his father after dinner, beating his drum, and laughing within himself at the people that had laughed at him in the morning. He was however sometimes sorry at heart, when he recollected that he should perhaps never see his dear ass again.

THE TOWN MOUSE AND THE COUNTRY MOUSE.↩

Perhaps you may think that fables are only an amusement for children. But, without mentioning to you how highly Esop and the other famous makers of fables have been thought of all over the world, I am going now to tell you a thing which will convince you how much you are mistaken.

You have heard of Rome, a fine old city of Italy. The consuls and emperors of Rome once governed the world, that is, as much of the world as they knew almost any thing about, for America and Botany-Bay had then never been heard of. In the time of these consuls and emperors there were a great many clever men, that wrote a great many wise and learned books. They are called the Latin authors. Now of all these Latin authors it is agreed that Virgil and Horace are the finest. I will tell you a fable that was written by Horace; and, if ever you learn Latin, you shall then read it in Horace's own words.

There was a mouse that lived in the country; I dare say at Horace's farm that he was so fond of; for Horace lived at a pretty white house with green window-shutters; he had a large garden of vegetables and flowers; with a fine fish-pond in front; and behind, a beautiful serpentine walk through a wood.

This mouse had a cousin that lived in town. I believe his home was at the palace of Mæcenas, the emperor's prime minister of state, that was built with pillars of marble, and ceilings of stucco-work.

Now, though the house where the country-mouse lived was only a sort of a cottage, a little better than the ordinary cottages round it, yet he loved his relations and friends, as much as the best mouse that wore a head; and he begged and prayed his town-cousin to come some day and take a dinner with him. The town-mouse consented.

When the visitor came, the country mouse showed him all he had to show, the fish-pond, and the garden, and the wood, and how prettily the white house looked with the green window-shutters. They sat down to dinner. The host had ranged all the provisions in a hollow tree, that they might be sure not to be disturbed. He placed a nice soft cushion of moss for his guest, and set before him a little piece of bacon, and a morsel of beef that had been boiled for soup, and a bit of cheese, and a golden pippin. The country-mouse sat in a lower place, and ate nothing but a crust of bread, and a piece of the hard rind of cheese, leaving all the rest for his cousin. He was as polite to his visitor as a mouse could be, and hoped he would be able to make a dinner, and assured him that the cheese was made of the finest cream, and the pippin was fresh gathered. The city-mouse however made a miserable meal; he could not relish such country-fare. After dinner he asked his entertainer very gravely, how he could be content to waste his life in such a wretched hole? Consider, said the town-mouse, you are now young, and should enjoy yourself. You should see men and cities. When once you know the world, you will despise this rustic life as much as I do. The town-mouse gave the country-mouse such an account of what a fine thing it was to go to court, that at last he consented to go back with him to the palace of Macenas on the Esquiline hill.

A long and weary journey they had of it; and, though a man could have walked it in three or four hours, a mouse was obliged to sleep one night on the road. They got to Rome the next night, and crept silently and softly to the town-mouse's home. The country-mouse was out of his senses to see what a fine home it was. The rooms were almost as large and lofty as a church; the walls were adorned with looking-glasses and gilding; and immense chandeliers of silver hung from the ceiling.

I confess, says he, I begin to think Horace's farm was but a miserable hole.

I thought, answered the town-mouse, I should bring you to your senses.

He then led his visitor into the room where Maecenas and his friends had dined. The mice climbed up upon the table. There was nothing left but the dessert; but such a dessert! There were pine-apples, and ice-creams, and melons, and grapes, and preserves, and perfumes, and sugar in abundance. The town-mouse felt himself at home. The country-mouse frisked about as if he had been mad. He had never seen such a sight in his life. Why, here, said he, are provisions enough to last Horace for a month!

He was so long smelling and examining the different plates, that he had not tasted a bit, when the door burst open. It was the butler and five or six footmen, who were come to clear away the dessert, and prepare every thing for their master's supper. With them pranced in a couple of fine Italian grey-hounds. But, what was worst of all, at the heels of the grey-hounds came, jumping along, the largest tom-cat you ever saw. The mice were terribly frightened, and scampered away as fast as they could. But the walls of the marble dining hall were so well fitted, that there was not a chink for so much as a spider to hide himself. It was almost a miracle that the mice escaped, and at last got to a dark, dirty hole in some wainscot, where the town-mouse was accustomed to sleep.

Come, he said to his guest, I dare say you are tired; you will stay snug here to-night.

Not in a minute, said the country-mouse, that I can help! As soon as every thing is once more quiet, I will take my leave of cities and ministers of state for ever. I dare say I shall not recover the fright I have been in for a fortnight. Give me a temperate life and a safe one. I shall thank you, the longest day I have to live, for the lesson you have taught me. I shall go home now, and know, better than ever I did before, the blessings of a hollow tree and a crust of bread.

THE MISER AND HIS TREASURE.↩

A poor man once scraped together by little and little a sum of fifty guineas. It was all got by the labour of his own hands, and I believe it was some years before he had made it so much. In the village where he lived they had known him from a boy, and a smart, merry boy he was. He was always laughing from morning till night. This was certainly laughing too much; but the boy meant no harm, and every body laughed with him. Poor fellow, he had never learned to read or write; he thought he had no chance to be wise; he had heard something about merry and wise; and, as he could not be wise, he determined to be merry, that he might be sure to be something.

Well, when he was about twenty or thirty years old, the fancy took him, that he would save a penny or two-pence a day, till he had got fifty guineas. If he saved only two-pence a day, he must have been fifteen years about it; but I believe he got some presents, and a little matter that his father and uncle left him when they died, which made him not quite so long. I wonder what he intended to do with his fifty guineas when he had got it? Did he mean to buy a horse? or a pleasure-boat? or a fine gold watch with a gold seal to it? What could he do with fifty guineas? You shall hear: but do not be in a hurry now!

It was very hard for him always to lay by two-pence out of the wages of his day's work. He never bought any oranges or cherries. When other people went to the fair, he staid at home. When other people got a little bit of meat or of cheese, he had nothing but dry bread for his dinner; and, instead of beer, he drank only water. I assure you, when people work all day ploughing or digging, they ought to drink beer, and some strong beer too.

But what people thought the strangest of all was, that this fellow who had been so merry and good-natured a boy, grew very serious, and, what was worse, very ill-tempered too. He hardly ever spoke, and when people asked him a question, he answered them as roughly as possible. The fact was, he was always thinking of his money, and the thought of it would not even let him sleep of nights. Then he was so much troubled what to do with it, and how to keep it safe. When he lived in a house, it was a poor sort of a house, with a door that a man could almost burst open with his foot: and, when he lived in a lodging, he had but one room, and other people sometimes came into the room. So he went to the schoolmaster of the village, and begged the favour of him to take care of it. The schoolmaster was a very good man, and kept it quite safe. But the poor man was not a bit the easier: he thought the schoolmaster might lose it, might have his house robbed, or might die and the people who came after him might not believe that so great a heap of money belonged to so poor a man. As he could neither write nor read, he did not understand much about receipts and promisory notes.

At last, when he had made it up full fifty guineas, he went to the schoolmaster, and begged he might have it in his own possession. And now we come to see what he did with it. He thought about horses and pleasure boats and watches. But none of these things pleased him. When he got home, he crept into the darkest corner of his room, and began to count his money. He thought fifty guineas in gold looked prettier than all the horses and pleasure-boats in the world. But where should be put them? He thought of twenty people to take care of them, and twenty places to hide them. At last he collected a solitary field a great way from any path, and he determined to bury them there. He went to the field, and walked round the field, and looked in every corner. By and by he spied a large stone which stuck so deep in the ground that nothing but the top of it could be seen. With a good deal of trouble he pulled it up. There was then a deep hollow place. The miser now took out his hedging-knife, and made a round mark in the middle of this place, and shoveled out the mould, till he had got a hole big enough to hold his fifty guineas. He then put down the stone again, and it lay as close and as snug as if it had never been moved.

It was a good while before he could prevail upon himself to go away. Once or twice he raised the stone gently by one corner, and peeped in: there were the guineas! He had not gone the length of two fields, before he came back. He looked all round to see if there was any body near: he then raised the stone as before: there were the guineas! He came twice again before night, and the last time, he took out his money and counted it.

Unluckily Wicked Will happened to be all the while at work on the other side of the hedge. Wicked Will was a good-for-nothing, drunken fellow, and had neither truth nor honesty in him. If the miser had come but once, Will would have thought nothing of the matter; but he was surprised to see him come so often. He recollected what a scraping, saving man the miser was, and began to guess the truth. Night was no sooner completely come, than Will went to the spot, took away the money, and walked and ran twenty miles before day-light, that he might never be found.

The next morning, as soon as it was light, the miser set out again to look at his money. I firmly believe he would never have been able to do a day's work as long as it staid there, he would have wanted to look at it so often. You may think then how sorry he was, when he raised the stone, and found it gone. He cried and screamed, and acted like a madman. He staid there so long, that at last the farmer to whom the field belonged, opened the gate and rode in, to consider whether he should lay the field down for grass, or plough it for corn. He presently saw the miser and his distress.

What is the matter with you, my good fellow? said the farmer.

Oh, my money, my money! said the miser.

What money?

Oh, my money! my fifty guineas!

Where are they?

I buried them yesterday under this stone, and they are gone.

Buried them! said the farmer, that is a strange way to treat money. Why did not you keep it at home, and then it would have been always ready for use.

Use! said the miser. I would not have spent a penny of it, to save myself from starving. For all the world I would not have made it a farthing less than fifty guineas.

Oh, if that is the case, said the farmer, there is a number of pebbles in yon corner; fetch fifty of them, and put them in the hole, and they will do every bit as well as guineas for every thing but use. If you had saved a little against you were sick or lame, I should have thought you a wise man; but if you had determined never to change one of your guineas, take my word for it you have lost nothing at all.

Now what do you think happened after this poor miser? He never got his money again. For some days he was so sorry, that he could hardly go to work. But by degrees he forgot his loss: and then, I cannot tell how it happened, when he was no richer than his neighbours, he ate better, and whistled better, than when he had fifty guineas that he had resolved never to change.

THE FOX AND GRAPES.↩

I do not know of my own knowledge that foxes are fond of grapes. But Esop says they are, and that is enough for us.

A fox once found his way into a very fine garden. I suppose he had missed his road, for the favourite walk of the fox is into the poultry-yard, that he may pick up a chicken or two for his dinner. Here there were a great many fine flowers; but the fox did not care for that. Men are very fond of flowers, and so are bees and other insects; but birds and beasts think nothing about them; you never saw either smell at a rose. There was also a great deal of fine fruit: and, as Esop's fox was fond of grapes, I dare say he was delighted to see the apples and pears and nectarines and peaches. He walked up and down the garden, and was so pleased with every thing, that for the life of him he did not know what to chuse.

At last he came to a wall that was all covered with the finest grapes you ever saw. They were full of juice almost ready to burst; the purple ones were turned black, and the green were so ripe, that they looked as if you could see through them. I said, the wall was covered with grapes; but that is not quite exact. The ladies and gentlemen had gathered all the clusters that hung within their reach; but higher up the vines were still full. The moment the fox saw them, his choice was fixed: he resolved to make his dinner here without seeking any further.

The fox is a very little animal, though he is very nimble. His ambition was greater than his strength. He jumped and jumped, you never saw such jumps in your life. First he could not jump high enough; but afterward he mended his jumps, and I believe jumped quite as high as the clusters. But, I do not know how it was, not a single grape he could catch. At last he was quite tired and almost lamed with the efforts he had made. The fox was extremely mortified. He looked up; there hung the grapes, but not one for him! He determined then to carry off his disappointment with a spirit. What a fool have I been! said he. I can see now plain enough that the grapes are sour, and not fit to be eaten.

From this fable it has come to be a proverb, when a man pretends not to wish for what he cannot have, to say to him, The grapes are sour. If you ask a poor haymaker, whether he would not like that the parsonage-house were his? perhaps he will answer, No, indeed, he likes his mud-cottage as well. The fox was not wrong to endeavour contentedly to go without what he could not get, but he need not have told an un-truth.

THE LION AND THE MOUSE.↩

The lion you know is the king of animals. He is a fine creature; and the proofs he gives of his strength are such as we hardly know how to believe. He is said to be very generous. He is so formed that he must have meat to eat, and there are no butchers' shops in the forests; so he is obliged to kill his meat himself. But they say he never kills any creature for sport or cruelty; and that he will not touch a man, but when he is almost starving with hunger. He is very proud, and will never eat of a dead body that any other animal has killed.

A lion was once sleeping in a forest. A poor little mouse, that thought no harm, was playing about, and in one of his frisks ran against the lion, and awaked him. The lion, angry with being disturbed, and not knowing who had done it, put out his paw, and took up the mouse. The mouse was terribly frightened, and thought he was going to be killed in a moment. The life of a mouse is of quite as much value to him, as the life of a rhinoceros. But, when the lion looked at his victim, he could not find in his heart to hurt such a poor little fellow. He set him down very gently. The mouse scampered away as fast as he could, and was so overjoyed with his escape, that he had not time to say, Thank you! to the king of beasts.

A few days afterward, as the lion was prancing away, and amusing himself in the forest, he happened unawares to entangle himself in a large net that some sailors had spread, who wanted to catch a lion for king George, to be put into the Tower of London. When he felt his situation, he was full as much frightened as the mouse had been the other day. He struggled, and sprang, and tossed himself about, but all to no manner of purpose; he only made the business worse. He roared with terror, till all the forest rung with the sound.

The poor mouse, who was not far off, heard the noise, and knew the voice of the animal that had treated him so generously. He ran to examine what was the matter, and whether he could give any assistance. He presently saw how it was. A mouse, though so very little, is an extraordinary animal, and can gnaw through brick-walls. He set himself to gnaw the meshes of the net, and he was never tired till he had done his work. In two or three hours he had gnawed through so many threads, that the lion rose up, as free a beast as ever. The lion was inexpressibly astonished at his deliverance and his deliverer; and you may think how glad he was that he had behaved generously, when the mouse offended him, and woke him out of his sleep.

THE OLD MAN AND THE BUNDLE OF STICKS.↩

At Christmas you know the days are very short and the nights very long. Yet neither young people nor old want to sleep more at Christmas, than they do at Midsummer. Therefore they are obliged to employ and amuse themselves more in the house and less in the fields at Christmas than they do at Midsummer. This is the original reason of Christmas games, of puzzles, and riddles, and Do you know how to do what I can do? One of these games is, I can put the candle where every body in the room can see it, and you cannot: can you do that?

An old man was sitting by his fireside, while his children were amusing themselves with Christmas games. He did not appear to take any part in their amusements, though he listened to every thing that was going on. Christmas games are more properly the employment of young people than of old ones. At last he lifted up his head and said, One of you, bring me faggot of sticks from the woodhouse! Sam ran away, and fetched it in a moment. What do you want it for, father? said he. I am sure there is a very good fire.

You have all been telling your puzzles, said the father; now I will tell you one. Which of you can break this bundle of sticks? I can, said Sam; and I can, said Bob. For young people almost always think they can do every thing, before they have tried, or considered how it is to be done.

Put the bundle down, said the father, and let the youngest try first. William is too young; but I dare say Charles thinks he can manage it. They all tried from the youngest to the eldest. One lifted it up, and clapped it to his knee. Another put it on the ground, and put his knee to it; a third sat upon it; a fourth stamped upon it; a fifth proposed pinching it with the hinge of the door. We cannot do it, father, said they. Then I will, replied the old man.

Fetch me a knife! Oh, father, said Charles, you asked us to break the bundle of sticks, not to cut it. Be quiet, boy! said the old man.

The faggot was bound together with a sort of cord of withy. The old man cut this cord. The faggot immediately tumbled to pieces. He then took up the sticks, one by one, and broke them, as easily as you would crack a nut. The boys all laughed till they could not contain themselves. But the old man went on very gravely, till he had broken every stick in the faggot. What fools we were not to think of that way, said one, and said all.

Very true, my boys, answered the father. In almost all cases it is by wit more than by strength, that difficulties are conquered. He that works with his head, will accomplish his object with the tenth part of the toil, that another must employ, who has hands, but no head.

THE DISPUTED OYSTER. ↩

Two men, walking together on the beach of the sea, happened to spy an oyster. Aha! said one of them, look here, my friend! what a fine oyster! Both of them happened to be very fond of oysters; but your oyster-eaters say, an oyster is spoiled, if it is cut; and they had neither of them a knife. What was to be done? I cannot tell what two generous men would have done in such a case, but each of these men loved an oyster better than his friend. They both ran to take up the poor fish; they knocked their heads against each other, and were almost going to fight.

Come, come, said one, we will not go to blows about an oyster neither! That would be too foolish. The rule is, He that sees a God-send first, he is the man. In that case, said the first, the oyster is mine, for I showed it you. Do not pretend I am near-sighted neither, said the second; I have as good eyes as my neighbour. A long while before you spoke, I saw something lying on the beach, and was almost sure it was an oyster. They could not settle who saw it first.

They might have drawn lots, or tossed up a halfpenny, to see who should have the oyster. But they were grave gentlemen, and thought that was too childish a way to settle an affair of this importance.

As they were in the height of their dispute, a droll fellow happened to be coming along the beach, who lived in the same village. We will take Tom Smith to be judge, said one. Agreed, said the other. Tom came up, and they told him the story.

So you are determined to go to law before me for the oyster?

We are.

Silence the court! Who has got an oyster-knife?

They had neither got a knife. In their great hurry to eat the oyster, they forgot that they could not open it. Tom had got one.

Now, gentlemen, let me hear the pleadings on both sides: what have you to say for yourselves?

I spoke first! I saw it first! I have the best right! I have a better!

Tom opened the oyster. He looked at one of the claimants, and then at the other, and then at the oyster. It was a fine fat fellow as ever you saw. Nothing could be more tempting. Tom put it to his mouth, and swallowed it in a moment. He then with great gravity gave the two disputants each of them a shell. They stared.

You agreed to go to law for the oyster, said Tom. Did you never hear that people who go to law for something they dispute about, are often obliged to pay as much as it is worth in expences, and at last get nothing better than an oyster-shell for their pains?

So both the men laughed heartily at Tom's wit, and owned that he could not have decided better. He had got a fine oyster, and they had got a lessons at least as good as an oyster, by the bargain.

THE GOOSE WITH GOLDEN EGGS.↩

A boy had once a goose that laid him every day a golden egg. This must be one of Esop's geese; there are no such geese in our days.

I wonder what a golden egg would be worth. If it were all solid gold, it would be worth at least fifty pounds. Fifty pounds a day, is eighteen thousand two hundred and fifty pounds a year; so that this boy was tolerably rich.

Rich men are sometimes apt to be whimsical; it is no wonder therefore that a rich boy should have been so. What could he want to buy, that fifty pounds a day would not purchase? I suppose he wanted to buy a gold watch, and a gold-lace coat, and a gilded coach with six long-tailed horses; and was unhappy because he could not buy them all in one day.

If I had been the possessor of this extraordinary goose, I think I should have loved her very much. I never had a dog, or a cat, or any living creature, that I called my own, and that depended on me for its food, that I did not love, and take a great deal of care of. For this goose I would have inclosed a beautiful field with iron palisades for the goose to walk in, and have made a clear fish-pond in the middle of it for her to swim in. I would have made a nice warm shed for her to sleep in, with a fresh bed of clean straw every day. I would have fed her with the finest barley, and have given her plenty of geese, and ducks, and swans, if she liked it, to keep her company. I could have done no less, for the most profitable friend I had.

The silly boy I am telling you of did none of these things. I believe he took care that nobody should steal her. She had lived with him several years, and never failed of her egg a day; so that the ungrateful boy did not think himself at all obliged to her for what she brought him, and would have been very much out of temper with her, if she had once missed of her egg.

Well, this boy, as I was telling you, did not think fifty pounds a day enough, and was very unhappy that he had not got more. He wanted to have every thing at once. With such a quantity of money he was never used to be disappointed; and, when he had spent his fifty pounds in the morning, he was sure to see several things before night, that he wanted to buy, but he was so poor that he could not.

I am ashamed to tell you what this wicked boy did. I have already mentioned that he did not love his goose at all; and, though she did so much for him, he did not feel thankful to her. Would you believe, that he got a great knife, and he killed her?

You perverse ill-natured goose! said he, Why then did not you lay me two eggs a day? Why did you always keep me so poor?

As she brought him an egg every day, he thought he should find a great many eggs in her belly. There was not one. He found nothing but a little barley in her crop, which in time would have enabled her to lay more eggs.

The boy now was as poor as any of the poor beggar-boys you see in the streets. They were obliged to take him into the parish-workhouse that he might not be starved; and I cannot say that I greatly pity such an ungrateful, wicked boy.

THE BOYS AND THE FROGS.↩

Some school-boys were just come out of school. You cannot think what a noise they made. They seemed to be all talking at once. One snatched off another's hat, and ran away with it. A second jumped over his comrade's back. Some wrestled; some ran, and almost pushed one another down. They were all in high glee.

They presently came into a field. Some had bats and balls; some had marbles; and a few came to fly their paper-kites. In one corner of the field there was a pond, and by the side of the pond there was a number of frogs that were basking and amusing themselves. Poor harmless frogs! Why should not a frog be happy as well as a boy?

One inconsiderate boy caught up two or three stones, and began to throw them at the frogs. When one boy does a naughty thing, others are very apt to do the same. I will lay you a halfpenny, said one, that I can hit that large old one. I will hit that little skinny one in a corner, said a second, which is harder to do than yours.

Esop says, one of the frogs, seeing the cruel mischief that was going to happen, spoke to the boys. I rather think it was one good and humane boy that spoke to the rest. I will tell you however what was said.

Stop a minute, I beg of you, and consider what you are going to do. If you had one of the frogs in your hand, which I would not advise you to take, because I should be afraid you would hurt him, you would feel how his heart beats. What bright shining eyes he has got! What a vast way he jumps! How nimble he must be! God gave him his eyes, and his legs, and his joints, and his heart, and all his motions. If you threw a stone at me you might hurt me very much. But to throw it at a poor little frog! You might break one of his legs, or two, or dash out his brains. If you killed him, he could never take his pretty jumps any more, but would lay as still as the stone you have in your hand. If you broke his legs, he could not help himself, but would pine a day or two in misery, and then die. When you are laughing, always consider whether the same thing that makes you laugh, makes some other creature cry, or be miserable. None but a brute of a boy, who deserves to have every bone in his skin broken, would knowingly laugh at another's misery.

These boys were convinced, and all of them agreed that they would never more run the risk of breaking a frog's legs, or knocking out one of his eyes.

I am sorry to say, that boys are too apt to be cruel. They will sometimes throw stones at the pretty birds as they hop along in the hedge. But what I think is worst of all, is taking away the birds' nests, and thus making a mother miserable for the loss of all her young ones. A bird's nest is her home and all her happiness: what good can it do to you to disturb her? I hope, my dear Charles, I may depend upon you, that you will never do such things.

THE MICE IN COUNCIL.↩

There is no living creature so small, not even the mites that live in a cheese, as not to be capable of feeling both pleasure and pain. It is a great pity that we cannot live without hurting any thing; but we cannot. The great fish eat the little ones; the great birds and beasts prey upon the small; even the little birds eat worms and flies; and we eat oxen and sheep and calves. When they are dead, we call them beef and mutton and veal, and are glad to forget that they were once alive.

It is very right to kill some creatures because they hurt us. It is not at all necessary that we should have our clothes full of fleas, or our houses full of rats and mice. Nobody but a fool would submit to these inconveniences, and have his house and every thing about him spoiled, because he would not consent that these creatures should be killed. If we did not kill the rats and mice, we should presently be in the situation of the king and queen in the story of Dick Whittington, who, as soon as their diner was set on the table, saw it devoured by these creatures, before they had time to touch a bit. Our rule therefore should be, never to kill any creature but in case of necessity, and never to be wicked enough to make sport to ourselves of other creatures' pain.

I day say you know why it happens that you can scarcely go into a house where you will not find a cat. The reason is because cats are very clever at catching the rats and mice. The greatest praise you can give to a cat, is to say that she is a good mouser.

There was once an old house that from the cellar to the garret abounded with mice. It had been a good, handsome house once, but now it was so old that nobody lived in it, and it was hired by some one for a store-house. In one part of it he put books, in another part blankets and drapery, and in another sacks full of corn. No part of this store was spared by the mice. They nibbled and tore the books, and gnawed the blankets, for their sport; and they dined every day plentifully on the gentleman's corn. He presently saw that he had better have no store, than have it all spoiled and devoured by the mice. He therefore brought a fine cat, that loved him very much, and that he had taken great care of ever since she was a kitten; and left her to catch the mice. The cat understood her business very well; the mice had no apprehension of an enemy; and an immense number of them were killed.

Those that were left alive began to perceive their situation, and kept close in their holes, where the cat could not follow them. They wished now that they had let alone the gentleman's books and blankets, and had fed more sparingly on the corn. Perhaps then he would not have brought his cat into the house. They dared not stir, night or day. They thought the cat was always awake. They sleep of a cat is very light, and the smell of a mouse will make her jump up and run at any time. They were almost starved to death.

At length they got all together in some corner, out of the cat's reach, with the intention to consult what they should do. This meeting was nothing like what their meetings had been before the cat came. Then they had all of them their bellies full, and were merry, and capered and frisked about like mad things. Now every one was hungry and melancholy. Half their numbers were missing; fathers and mothers and children had all fallen a prey to the terrible cat. Some remedy was grievously wanting against the attacks of the furious wild beast. But the wisest mouse among them could not tell what remedy to recommend.

While the old ones sat mute with doubt and alarm, a pert young mouse said he had thought of an expedient that would exactly do. Perhaps, said he, none of you have considered the case so closely as I have. If you do but recollect, you will find that even a cat can be in only one room of this large house at a time, and that all the difficulty is to know which room that shall happen to be. A mouse has as many legs as a cat; and we could presently get out of her reach, if we did but know when she was coming. But the misfortune is, that she creeps along slily, and is upon us in a minute, when we are thinking nothing of the matter. Now my advice is, that we should get one of those little hollow bells, that children sometimes hang to the neck of a kitten, and fasten it upon this cat, and then I defy her to creep so slowly, but that this bell shall go tingle, tingle, every step she takes.

All the young mice were in admiration at the wise speech of their play-fellow. They agreed that he was a mouse of genius, and a great benefactor to the whole community of mice. What happy days they should pass, when the bell was once hung about the cat's neck! They should laugh at their old enemy, and might peep out, and then scamper away, before she could catch them.

As soon as silence was made, the oldest mouse of the company begged to be heard. He said that the speech of his pert young friend was a very wise speech indeed! The expedient he had hit upon was excellent, and it was impossible to make more than one objection to it. That was, who should hang the bell upon the cat's neck? But, as they had the happiness to have one mouse among them of so great wisdom, perhaps they might have another not inferior in courage, who would do the feat that the young gentleman had recommended.

The young mice saw that the old one was laughing at them, and he that had made the speech, was so ashamed, that he slunk away to his hole. At last I believe they agreed that the best thing they could do, was for all of them to go away, and look out for some other house, that was not guarded by so ferocious a cat.

THE COUNTRY-MAID AND HER MILK-PAIL.↩

In the pictures in your book of London Cries, you will see that some of the hawkers carry their wares in baskets upon their heads. There is the fruit-man, Buy my strawberries! fine, scarlet strawberries! and the fish-man, Buy my lobsters! buy my pickled salmon! I have often wondered that, as they walk careless and merry along the streets, their baskets do not topple off upon the pavement. The milk-maids sometimes carry their pails of milk in the same manner; and this I am told is much more common in France than it is in England.

A country-girl was once walking with her pail-full of milk upon her head: I suppose she was a French girl. She was generally as merry as a cricket; you never saw a creature with such life and spirits. She was always chattering, and her chatter was extremely diverting to almost every body that heard it, because she was very good-natured. The only person that sometimes was not diverted with it was her mother, because this merry disposition of the girl continually made her forget something that her mother had told her to do. The mother was a very good, but a very poor woman; with a great deal of care she saved enough in the week to buy them a Sunday's dinner, and with a great deal of hard work she made their little room as clean as a penny to eat it in. The girl very cheerfully helped her mother in all this; she rubbed and scrubbed as well as the best. But then, as I told you, she was so thoughtless; she lost one thing, she broke another, she tore her shift, and forgot to buy capers to the mutton. You will be surprised when I tell you that this faulty girl was as tall as a woman: her mother was quite ashamed of her. You are sometimes thoughtless now; but I am sure you will cure yourself soon, and when you are sixteen or twenty, will be the most considerate creature in the world.

The mother had tried a hundred ways to cure her. Sometimes she scolded the girl, and then the girl cried bitterly, for she could not bear that her mother should be angry with her. Sometimes the mother cried too, and said gently, Now, Phillis, you have broken the dish that should hold our Sunday's dinner: indeed you will ruin me by your carelessness! They had nothing to live upon but the profits of the milk of one pretty cow, which they carried every day and sold at the market-town.