ERASMUS

Against War (1917)

(Dulce Bellum Inexpertis) (1517)

|

|

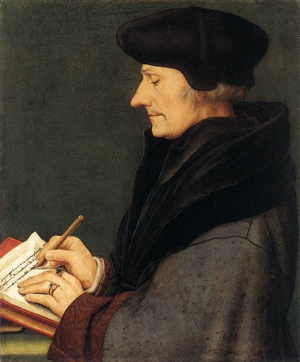

| Desiderius Erasmus (1466-1536) |

[Created: 17 March, 2022]

[Updated: 13 July, 2023 ] |

The Guillaumin Collection

|

This title is part of “The Guillaumin Collection” within “The Digital Library of Liberty and Power”. It has been more richly coded and has some features which other titles in the library do not have, such as the original page numbers, formatting which makes it look as much like the original text as possible, and a citation tool which makes it possible for scholars to link to an individual paragraph which is of interest to them. These titles are also available in a variety of eBook formats for reading on portable devices. |

Source

, The Humanists’ Library. Edited by Lewis Einstein. II. Erasmus against War with an Introduction by J. W. Mackail (Boston: The Merrymount Press, MDCCCCVII (1917)).http://davidmhart.com/liberty/OtherLiberals/Erasmus/DulceBellumInexpertis/1907-edition/index.html

The Humanists’ Library. Edited by Lewis Einstein. II. Erasmus against War with an Introduction by J. W. Mackail (Boston: The Merrymount Press, MDCCCCVII (1917)).

This is a modernized version of an English translation of Erasmus’s Dulce Bellum Inexpertis (war is sweet to those who have not experienced it) (1517) which was published in 1534 as Bellum Erasmi (Erasmus on War). A transcription of the original English version can be found at the Oxford Text Archive. I have not been able to find a version in facs. PDF. Note that this 1917 edition was published 400 years after its first appearance and when the First World War was underway and with a new title “Erasmus Against War”.

This title is also available in a facsimile PDF of the original and various eBook formats - HTML, PDF, and ePub.

This book is part of a collection of works by Desiderius Erasmus (1466-1536).

CONTENTS

- Introduction, p. ix

- Against War, p. 3

[ix]

INTRODUCTION↩

he Treatise on War, of which the earliest English translation is here reprinted, was among the most famous writings of the most illustrious writer of his age. Few people now read Erasmus; he has become for the world in general a somewhat vague name. Only by some effort of the historical imagination is it possible for those who are not professed scholars and students to realize the enormous force which he was at a critical period in the history of civilization. The free institutions and the material progress of the modern world have alike their roots in humanism. Humanism as a movement of the human mind culminated in the age, and even in a sense in the person, of Erasmus. Its brilliant flower was of an earlier period; its fruits developed and matured later; but it was in his time, and in him, that the fruit set! The earlier sixteenth century is not so romantic as its predecessors, nor so rich in solid achievement as others that have followed it. As in some orchard when spring is over, the blossom lies withered on the grass, and the fruit has long to wait before [x] it can ripen on the boughs. Yet here, in the dull, hot midsummer days, is the central and critical period of the year’s growth.

he Treatise on War, of which the earliest English translation is here reprinted, was among the most famous writings of the most illustrious writer of his age. Few people now read Erasmus; he has become for the world in general a somewhat vague name. Only by some effort of the historical imagination is it possible for those who are not professed scholars and students to realize the enormous force which he was at a critical period in the history of civilization. The free institutions and the material progress of the modern world have alike their roots in humanism. Humanism as a movement of the human mind culminated in the age, and even in a sense in the person, of Erasmus. Its brilliant flower was of an earlier period; its fruits developed and matured later; but it was in his time, and in him, that the fruit set! The earlier sixteenth century is not so romantic as its predecessors, nor so rich in solid achievement as others that have followed it. As in some orchard when spring is over, the blossom lies withered on the grass, and the fruit has long to wait before [x] it can ripen on the boughs. Yet here, in the dull, hot midsummer days, is the central and critical period of the year’s growth.

The life of Erasmus is accessible in many popular forms as well as in more learned and formal works. To recapitulate it here would fall beyond the scope of a preface. But in order to appreciate this treatise fully it is necessary to realize the time and circumstances in which it appeared, and to recall some of the main features of its author’s life and work up to the date of its composition.

That date can be fixed with certainty, from a combination of external and internal evidence, between the years 1513 and 1515; in all probability it was the winter of 1514-15. It was printed in the latter year, in the “editio princeps” of the enlarged and rewritten Adagia then issued from Froben’s great printing-works at Basel. The stormy decennate of Pope Julius II had ended in February, 1513. To his successor, Giovanni de’ Medici, who succeeded to the papal throne under the name of Leo X, the treatise is particularly addressed. The years which ensued were a time singularly momentous in the history of religion, of letters, and of the whole life of the civilized world. The eulogy of Leo with which Erasmus ends indicates the hopes then entertained of a new Augustan age of peace and reconciliation. The Reformation was still capable of being regarded as [xi] an internal and constructive force, within the framework of the society built up by the Middle Ages. The final divorce between humanism and the Church had not yet been made. The long and disastrous epoch of the wars of religion was still only a dark cloud on the horizon. The Renaissance was really dead, but few yet realized the fact. The new head of the Church was a lover of peace, a friend of scholars, a munificent patron of the arts. This treatise shows that Erasmus, to a certain extent, shared or strove to share in an illusion widely spread among the educated classes of Europe. With a far keener instinct for that which the souls of men required, an Augustinian monk from Wittenberg, who had visited Rome two years earlier, had turned away from the temple where a corpse lay swathed in gold and half hid in the steam of incense. With a far keener insight into the real state of things, Machiavelli was, at just this time, composing The Prince.

In one form or another, the subject of his impassioned pleading for peace among beings human, civilized, and Christian, had been long in Erasmus’s mind. In his most celebrated single work, the Praise of Folly, he had bitterly attacked the attitude towards war habitual, and evilly consecrated by usage, among kings and popes. The same argument had formed the substance of a document addressed by him, under the title of Anti-Polemus, to Pope Julius in 1507. Much of the substance, much even of the phraseology of that [xii] earlier work is doubtless repeated here. Beyond the specific reference to Pope Leo, the other notes of time in the treatise now before us are few and faint. Allusions to Louis XII of France (1498-1515), to Ferdinand the Catholic (1479-1516), to Philip, king of Aragon (1504-1516), and Sigismund, king of Poland (1506-1548), are all consistent with the composition of the treatise some years earlier. At the end of it he promises to treat of the matter more largely when he publishes the Anti-Polemus. But this intention was never carried into effect. Perhaps Erasmus had become convinced of its futility; for the events of the years which followed soon showed that the new Augustan age was but a false dawn over which night settled more stormily and profoundly than before.

For ten or a dozen years Erasmus had stood at the head of European scholarship. His name was as famous in France and England as in the Low Countries and Germany. The age was indeed one of those in which the much-abused term of the republic of letters had a real and vital meaning. The nationalities of modern Europe had already formed themselves; the notion of the Empire had become obsolete, and if the imperial title was still coveted by princes, it was under no illusion as to the amount of effective supremacy which it carried with it, or as to any life yet remaining in the mediaeval doctrine of the unity of Christendom whether as a church or as a state. [xiii] The discovery of the new world near the end of the previous century precipitated a revolution in European politics towards which events had long been moving, and finally broke up the political framework of the Middle Ages. But the other great event of the same period, the invention and diffusion of the art of printing, had created a new European commonwealth of the mind. The history of the century which followed it is a history in which the landmarks are found less in battles and treaties than in books.

The earlier life of the man who occupies the central place in the literary and spiritual movement of his time in no important way differs from the youth of many contemporary scholars and writers. Even the illegitimacy of his birth was an accident shared with so many others that it does not mark him out in any way from his fellows. His early education at Utrecht, at Deventer, at Herzogenbosch; his enforced and unhappy novitiate in a house of Augustinian canons near Gouda; his secretaryship to the bishop of Cambray, the grudging patron who allowed rather than assisted him to complete his training at the University of Paris—all this was at the time mere matter of common form. It is with his arrival in England in 1497, at the age of thirty-one, that his effective life really begins.

For the next twenty years that life was one of restless movement and incessant production. In [xiv] England, France, the Low Countries, on the upper Rhine, and in Italy, he flitted about gathering up the whole intellectual movement of the age, and pouring forth the results in that admirable Latin which was not only the common language of scholars in every country, but the single language in which he himself thought instinctively and wrote freely. Between the Adagia of 1500 and the Colloquia of 1516 comes a mass of writings equivalent to the total product of many fertile and industrious pens. He worked in the cause of humanism with a sacred fury, striving with all his might to connect it with all that was living in the old and all that was developing in the newer world. In his travels no less than in his studies the aspect of war must have perpetually met him as at once the cause and the effect of barbarism; it was the symbol of everything to which humanism in its broader as well as in its narrower aspect was utterly opposed and repugnant. He was a student at Paris in the ominous year of the first French invasion of Italy, in which the death of Pico della Mirandola and Politian came like a symbol of the death of the Italian Renaissance itself. Charles VIII, as has often been said, brought back the Renaissance to France from that expedition; but he brought her back a captive chained to the wheels of his cannon. The epoch of the Italian wars began. A little later (1500) Sandro Botticelli painted that amazing Nativity which is one [xv] of the chief treasures of the London National Gallery. Over it in mystical Greek may still be read the painter’s own words: “This picture was painted by me Alexander amid the confusions of Italy at the time prophesied in the Second Woe of the Apocalypse, when Satan shall be loosed upon the earth.” In November, 1506, Erasmus was at Bologna, and saw the triumphal entry of Pope Julius into the city at the head of a great mercenary army. Two years later the league of Cambray, a combination of folly, treachery and shame which filled even hardened politicians with horror, plunged half Europe into a war in which no one was a gainer and which finally ruined Italy: “bellum quo nullum,” says the historian, “vel atrocius vel diuturnius in Italia post exactos Gothos majores nostri meminerunt.” In England Erasmus found, on his first visit, a country exhausted by the long and desperate struggle of the Wars of the Roses, out of which she had emerged with half her ruling class killed in battle or on the scaffold, and the whole fabric of society to reconstruct. The Empire was in a state of confusion and turmoil no less deplorable and much more extensive. The Diet of 1495 had indeed, by an expiring effort towards the suppression of absolute anarchy, decreed the abolition of private war. But in a society where every owner of a castle, every lord of a few square miles of territory, could conduct public war on his own [xvi] account, the prohibition was of little more than formal value. Humanism had been introduced by the end of the fifteenth century in some of the German universities, but too late to have much effect on the rising fury of religious controversy. The very year in which this treatise against war was published gave to the world another work of even wider circulation and more profound consequences. The famous Epistolae Obscurorum Virorum, first published in 1515, and circulated rapidly among all the educated readers of Europe, made an open breach between the humanists and the Church. That breach was never closed; nor on the other hand could the efforts of well-intentioned reformers like Melancthon bring humanism into any organic relation with the reformed movement. When mutual exhaustion concluded the European struggle, civilization had to start afresh; it took a century more to recover the lost ground. The very idea of humanism had long before then disappeared.

War, pestilence, the theologians: these were the three great enemies with which Erasmus says he had throughout life to contend. It was during the years he spent in England that he was perhaps least harassed by them. His three periods of residence there—a fourth, in 1517, appears to have been of short duration and not marked by any very notable incident—were of the utmost importance in his life. During the first, in his [xvii] residence between the years 1497 and 1499 at London and Oxford, the English Renaissance, if the name be fully applicable to so partial and inconclusive a movement, was in the promise and ardour of its brief spring. It was then that Erasmus made the acquaintance of those great Englishmen whose names cannot be mentioned with too much reverence: Colet, Grocyn, Latimer, Linacre. These men were the makers of modern England to a degree hardly realized. They carried the future in their hands. Peace had descended upon a weary country; and the younger generation was full of new hopes. The Enchiridion Militis Christiani, written soon after Erasmus returned to France, breathes the spirit of one who had not lost hope in the reconciliation of the Church and the world, of the old and new. When Erasmus made his second visit to England, in 1506, that fair promise had grown and spread. Colet had become dean of Saint Paul’s; and through him, as it would appear, Erasmus now made the acquaintance of another great man with whom he soon formed as close an intimacy, Thomas More.

His Italian journey followed: he was in Italy nearly three years, at Turin, Bologna, Venice, Padua, Siena, Rome. It was in the first of these years that Albert Dürer was also in Italy, where he met Bellini and was recognized by the Italian masters as the head of a new transalpine art in no way inferior to their own. The year after Erasmus left [xviii] Italy, Botticelli, the last survivor of the ancient world, died at Florence.

Meanwhile, Henry VIII, a prince, young, handsome, generous, pious, had succeeded to the throne of England. A golden age was thought to have dawned. Lord Mountjoy, who had been the pupil of Erasmus at Paris, and with whom he had first come to England, lost no time in urging Henry to send for the most brilliant and famous of European scholars, and attach him to his court. The king, who had already met and admired him, needed no pressing. In the letter which Henry himself wrote to Erasmus entreating him to take up his residence in England, the language employed was that of sincere admiration; nor was there any conscious insincerity in the main motive which he urged. “It is my earnest wish,” wrote the king, “to restore Christ’s religion to its primitive purity.” The history of the English Reformation supplies a strange commentary on these words.

But the first few years of the new reign (1509-1513), which coincide with the third and longest sojourn of Erasmus in England, were a time in which high hopes might not seem unreasonable. While Italy was ravaged by war and the rest of Europe was in uneasy ferment, England remained peaceful and prosperous. The lust of the eyes and the pride of life were indeed the motive forces of the court; but alongside of these was a real desire for reform, and a real if very imperfect attempt [xix] to cultivate the nobler arts of peace, to establish learning, and to purify religion. Colet’s great foundation of Saint Paul’s School in 1510 is one of the landmarks of English history. Erasmus joined the founder and the first high master, Colet and Lily, in composing the schoolbooks to be used in it. He had already written, in More’s house at Chelsea, where pure religion reigned alongside of high culture, the Encomium Moriae, in which all his immense gifts of eloquence and wit were lavished on the cause of humanism and the larger cause of humanity. That war was at once a sin, a scandal, and a folly was one of the central doctrines of the group of eminent Englishmen with whom he was now associated. It was a doctrine held by them with some ambiguity and in varying degrees. In the Utopia (1516) More condemns wars of aggression, while taking the common view as to wars of so-called self-defence. In 1513, when Henry, swept into the seductive scheme for a partition of France by a European confederacy, was preparing for the first of his many useless and inglorious continental campaigns, Colet spoke out more freely. He preached before the court against war itself as barbarous and unchristian, and did not spare either kings or popes who dealt otherwise. Henry was disturbed; he sent for Colet, and pressed him hard on the point whether he meant that all wars were unjustifiable. Colet was in advance of his age, but not so far in advance of it as this. He gave [xx] some kind of answer which satisfied the king. The preparations for war went forward; the Battle of Spurs plunged the court and all the nation into the intoxication of victory; while at Flodden-edge, in the same autumn, the ancestral allies of France sustained the most crushing defeat recorded in Scottish history. When both sides in a war have invoked God’s favour, the successful side is ready enough to believe that its prayers have been answered and its action accepted by God.

Erasmus was now reader in Greek and professor of divinity at Cambridge; but Cambridge was far away from the centre of European thought and of literary activities. He left England before the end of the year for Basel, where the greater part of his life thenceforth was passed. Froben had made Basel the chief literary centre of production for the whole of Europe. Through Froben’s printing-presses Erasmus could reach a wider audience than was allowed him at any court, however favourable to pure religion and the new learning. It was at this juncture that he made an eloquent and far-reaching appeal, on a matter which lay very near his heart, to the conscience of Christendom.

The Adagia, that vast work which was, at least to his own generation, Erasmus’s foremost title to fame, has long ago passed into the rank of those monuments of literature “dont la reputation s’affermira toujours parce qu’on ne les lit guère.” So [xxi] far as Erasmus is more than a name for most modern readers, it is on slighter and more popular works that any direct knowledge of him is grounded on the Colloquies, which only ceased to be a schoolbook within living memory, on the Praise of Folly, and on selections from the enormous masses of his letters. An Oxford scholar of the last generation, whose profound knowledge of humanistic literature was accompanied by a gift of terse and pointed expression, describes the Adagia in a single sentence, as “a manual of the wit and wisdom of the ancient world for the use of the modern, enlivened by commentary in Erasmus’s finest vein.” In its first form, the Adagiorum Collectanea, it was published by him at Paris in 1500, just after his return from England. In the author’s epistle dedicatory to Mountjoy he ascribes to him and to Richard Charnock, the prior of Saint Mary’s College in Oxford, the inspiration of the work. It consists of a series of between eight and nine hundred comments in brief essays, each suggested by some terse or proverbial phrase from an ancient Latin author. The work gave full scope for the display, not only of the immense treasures of his learning, but of those other qualities, the combination of which raised their author far above all other contemporary writers, his keen wit, his copiousness and facility, his complete control of Latin as a living language. It met with an enthusiastic reception, and placed [xxii] him at once at the head of European men of letters. Edition after edition poured from the press. It was ten times reissued at Paris within a generation. Eleven editions were published at Strasburg between 1509 and 1521. Within the same years it was reprinted at Erfurt, The Hague, Cologne, Mayence, Leyden, and elsewhere. The Rhine valley was the great nursery of letters north of the Alps, and along the Rhine from source to sea the book spread and was multiplied.

This success induced Erasmus to enlarge and complete his labours. The Adagiorum Chiliades, the title of the work in its new form, was part of the work of his residence in Italy in the years 1506-9, and was published at Venice by Aldus in September, 1508. The enlarged collection, to all intents and purposes a new work, consists of no less than three thousand two hundred and sixty heads. In a preface, Erasmus speaks slightingly of the Adagiorum Collectanea, with that affectation from which few authors are free, as a little collection carelessly made. “Some people got hold of it,” he adds, (and here the affectation becomes absolute untruth,) “and had it printed very incorrectly.” In the new work, however, much of the old disappears, much more is partially or wholly recast; and such of the old matter as is retained is dispersed at random among the new. In the Collectanea the commentaries had all been brief: here many are expanded into [xxiii] substantial treatises covering four or five pages of closely printed folio.

The Aldine edition had been reprinted at Basel by Froben in 1513. Shortly afterwards Erasmus himself took up his permanent residence there. Under his immediate supervision there presently appeared what was to all intents and purposes the definitive edition of 1515. It is a book of nearly seven hundred folio pages, and contains, besides the introductory matter, three thousand four hundred and eleven headings. In his preface Erasmus gives some details with regard to its composition. Of the original Paris work he now says, no doubt with truth, that it was undertaken by him hastily and without enough method. When preparing the Venice edition he had better realized the magnitude of the enterprise, and was better fitted for it by reading and learning, more especially by the mass of Greek manuscripts, and of newly printed Greek first editions, to which he had access at Venice and in other parts of Italy. In England also, owing very largely to the kindness of Archbishop Warham, more leisure and an ampler library had been available.

Among several important additions made in the edition of 1515, this essay, the text of which is the proverbial phrase “Dulce bellum inexpertis,” is at once the longest and the most remarkable. The adage itself, with a few lines of commentary, had indeed been in the original collection; but the [xxiv] treatise, in itself a substantial work, now appeared for the first time. It occupied a conspicuous place as the first heading in the fourth Chiliad of the complete work; and it was at once singled out from the rest as of special note and profound import. Froben was soon called upon for a separate edition. This appeared in April, 1517, in a quarto of twenty pages. This little book, the Bellum Erasmi as it was called for the sake of brevity, ran like wildfire from reader to reader. Half the scholarly presses of Europe were soon employed in reprinting it. Within ten years it had been reissued at Louvain, twice at Strasburg, twice at Mayence, at Leipsic, twice at Paris, twice at Cologne, at Antwerp, and at Venice. German translations of it were published at Basel and at Strasburg in 1519 and 1520. It soon made its way to England, and the translation here utilized was issued by Berthelet, the king’s printer, in the winter of 1533-4.

Whether the translation be by Richard Taverner, the translator and editor, a few years later, of an epitome or selection of the Chiliades, or by some other hand, there are no direct means of ascertaining; nor except for purposes of curiosity is the question an important one. The version wholly lacks distinction. It is a work of adequate scholarship but of no independent literary merit. English prose was then hardly formed. The revival of letters had reached the country, but for political and social reasons which are readily to [xxv] be found in any handbook of English history, it had found a soil, fertile indeed, but not yet broken up. Since Chaucer, English poetry had practically stood still, and except where poetry has cleared the way, prose does not in ordinary circumstances advance. A few adventurers in setting forth had appeared. More’s Utopia, one of the earliest of English prose classics, is a classic in virtue of its style as well as of its matter. Berners’s translation of Froissart, published in 1523, was the first and one of the finest of that magnificent series of translations which from this time onwards for about a century were produced in an almost continuous stream, and through which the secret of prose was slowly wrung from older and more accomplished languages. Latimer, about the same time, showed his countrymen how a vernacular prose, flexible, well knit, and nervous, might be written without its lines being traced on any ancient or foreign model. Coverdale, the greatest master of English prose whom the century produced, whose name has just missed the immortality that is secure for his work, must have substantially completed that magnificent version of the Bible which appeared in 1535, and to which the authorized version of the seventeenth century owes all that one work of genius can owe to another. It is not with these great men that the translator of this treatise can be compared. But he wrought, after his measure, on the same structure as they.

[xxvi]

It is then to the original Latin, not to this rude and stammering version, that scholars must turn now, as still more certainly they turned then, for the mind of Erasmus; for with him, even more eminently than with other authors, the style is the man, and his Latin is the substance, not merely the dress, of his thought. When he wrote it he was about forty-eight years of age. He was still in the fullness of his power. If he was often crippled by delicate health, that was no more than he had habitually been from boyhood. In this treatise we come very near the real man, with his strange mixture of liberalism and orthodoxy, of clear-sighted courage and a delicacy which nearly always might be mistaken for timidity.

His text is that (in the translator’s words) “nothing is either more wicked or more wretched, nothing doth worse become a man (I will not say a Christian man) than war.” War was shocking to Erasmus alike on every side of his remarkably complex and sensitive nature. It was impious; it was inhuman; it was ugly; it was in every sense of the word barbarous, to one who before all things and in the full sense of the word was civilized and a lover of civilization. All these varied aspects of the case, seen by others singly and partially, were to him facets of one truth, rays of one light. His argument circles and flickers among them, hardly pausing to enforce one before passing insensibly to another. In the splendid [xxvii] vindication of the nature of man with which the treatise opens, the tone is rather that of Cicero than of the New Testament. The majesty of man resides above all in his capacity to “behold the very pure strength and nature of things;” in essence he is no fallen and corrupt creature, but a piece of workmanship such as Shakespeare describes him through the mouth of Hamlet. He was shaped to this heroic mould “by Nature, or rather god,” so the Tudor translation reads, and the use of capital letters, though only a freak of the printer, brings out with a singular suggestiveness the latent pantheism which underlies the thought of all the humanists. To this wonderful creature strife and warfare are naturally repugnant. Not only is his frame “weak and tender,” but he is “born to love and amity.” His chief end, the object to which all his highest and most distinctively human powers are directed, is coöperant labour in the pursuit of knowledge. War comes out of ignorance, and into ignorance it leads; of war comes contempt of virtue and of godly living. In the age of Machiavelli the word “virtue” had a double and sinister meaning; but here it is taken in its nobler sense. Yet, the argument continues, for “virtue,” even in the Florentine statesman’s sense, war gives but little room. It is waged mainly for “vain titles or childish wrath;” it does not foster, in those responsible for it, any one of the nobler excellences. The argument throughout [xxviii] this part of the treatise is, both in its substance and in its ornament, wholly apart from the dogmas of religion. The furies of war are described as rising out of a very pagan hell. The apostrophe of Nature to mankind immediately suggests the spirit as well as the language of Lucretius. Erasmus had clearly been reading the De Rerum Natura, and borrows some of his finest touches from that miraculous description of the growth of civilization in the fifth book, which is one of the noblest contributions of antiquity towards a real conception of the nature of the world and of man. The progressive degeneration of morality, because, as its scope becomes higher, practice falls further and further short of it, is insisted upon by both these great thinkers in much the same spirit and with much the same illustrations. The rise of empires, “of which there was never none yet in any nation, but it was gotten with the great shedding of man’s blood,” is seen by both in the same light. But Erasmus passes on to the more expressly religious aspect of the whole matter in the great double climax with which he crowns his argument, the wickedness of a Christian fighting against another man, the horror of a Christian fighting against another Christian. “Yea, and with a thing so devilish,” he breaks out in a mingling of intense scorn and profound pity, “we mingle Christ.”

From this passionate appeal he passes to the praises of peace. Why should men add the horrors [xxix] of war to all the other miseries and dangers of life? Why should one man’s gain be sought only through another’s loss? All victories in war are Cadmean; not only from their cost in blood and treasure, but because we are in very truth “the members of one body,” “redeemed with Christ’s blood.” Such was the clear, unmistakable teaching of our Lord himself, such of his apostles. But the doctrine of Christ has been “plied to worldly opinion.” Worldly men, philosophers following “the sophistries of Aristotle,” worst of all, divines and theologians themselves, have corrupted the Gospel to the heathenish doctrine that “every man must first provide for himself.” The very words of Scripture are wrested to this abuse. Self-defence is held to excuse any violence. “Peter fought,” they say, “in the garden,”—yes, and that same night he denied his Master! “But punishment of wrong is a divine ordinance.” In war the punishment falls on the innocent. “But the law of nature bids us repel violence by violence.” What is the law of Christ? “But may not a prince go to war justly for his right?” Did any war ever lack a title? “But what of wars against the Turk?” Such wars are of Turk against Turk; let us overcome evil with good, let us spread the Gospel by doing what the Gospel commands: did Christ say, Hate them that hate you?

Then, with the tact of an accomplished orator, he lets the tension relax, and drops to a lower [xxx] tone. Even apart from all that has been urged, even if war were ever justifiable, think of the price that has to be paid for it. On this ground alone an unjust peace is far preferable to a just war. (These had been the very words of Colet to the king of England.) Men go to war under fine pretexts, but really to get riches, to satisfy hatred, or to win the poor glory of destroying. The hatred is but exasperated; the glory is won by and for the dregs of mankind; the riches are in the most prosperous event swallowed up ten times over. Yet if it be impossible but war should be, if there may be sometimes a “colour of equity” in it, and if the tyrant’s plea, necessity, be ever well-founded, at least, so Erasmus ends, let it be conducted mercifully. Let us live in fervent desire of the peace that we may not fully attain. Let princes restrain their peoples; let churchmen above all be peacemakers. So the treatise passes to its conclusion with that eulogy of the Medicean pope already mentioned, which perhaps was not wholly undeserved. To the modern world the name of Leo X has come down marked with a note of censure or even of ignominy. It is fair to remember that it did not bear quite the same aspect to its contemporaries, nor to the ages which immediately followed. Under Rodrigo Borgia it might well seem to others than to the Florentine mystic that antichrist was enthroned, and Satan let loose upon earth. The [xxxi] eight years of Leo’s pontificate (1513-21) were at least a period of outward splendour and of a refinement hitherto unknown. The corruption, half veiled by that refinement and splendour, was deep and mortal, but the collapse did not come till later. By comparison with the disastrous reign of Clement VII, his bastard cousin, that of Giovanni de’ Medici seemed a last gleam of light before blackness descended on the world. Even the licence of a dissolute age was contrasted to its favour with the gloom, “tristitia,” that settled down over Europe with the great Catholic reaction. The age of Leo X has descended to history as the age of Bembo, Sannazaro, Lascaris, of the Stanze of the Vatican, of Raphael’s Sistine Madonna and Titian’s Assumption; of the conquest of Mexico and the circumnavigation of Magellan; of Magdalen Tower and King’s College Chapel. It was an interval of comparative peace before a long epoch of wars more cruel and more devastating than any within the memory of men. The general European conflagration did not break out until ten years after Erasmus’s death; though it had then long been foreseen as inevitable. But he lived to see the conquest of Rhodes by Soliman, the sack of Rome, the breach between England and the papacy, the ill-omened marriage of Catherine de’ Medici to the heir of the French throne. Humanism had done all that it could, and failed. In the sanguinary era of one hundred years [xxxii] between the outbreak of the civil war in the Empire and the Peace of Westphalia, the Renaissance followed the Middle Ages to the grave, and the modern world was born.

The mere fact of this treatise having been translated into English and published by the king’s printer shows, in an age when the literary product of England was as yet scanty, that it had some vogue and exercised some influence. But only a few copies of the work are known to exist; and it was never reprinted. It was not until nearly three centuries later, amid the throes of an European revolution equally vast, that the work was again presented in an English dress. Vicesimus Knox, a whig essayist, compiler, and publicist of some reputation at the time, was the author of a book which was published anonymously in 1794 and found some readers in a year filled with great events in both the history and the literature of England. It was entitled “Anti-Polemus: or the Plea of Reason, Religion, and Humanity against War: a Fragment translated from Erasmus and addressed to Aggressors.” That was the year when the final breach took place in the whig party, and when Pitt initiated his brief and ill-fated policy of conciliation in Ireland. It was also the year of two works of enormous influence over thought, Paley’s Evidences and Paine’s Age of Reason. Among these great movements Knox’s work had but little chance of appealing to a wide audience. [xxxiii] “Sed quid ad nos?” the bitter motto on the title-page, probably expressed the feelings with which it was generally regarded. A version of the treatise against war, made from the Latin text of the Adagia with some omissions, is the main substance of the volume; and Knox added a few extracts from other writings of Erasmus on the same subject. It does not appear to have been reprinted in England, except in a collected edition of Knox’s works which may be found on the dustiest shelves of old-fashioned libraries, until, after the close of the Napoleonic wars, it was again published as a tract by the Society for the Promotion of Permanent and Universal Peace. Some half dozen impressions of this tract appeared at intervals up to the middle of the century; its publication passed into the hands of the Society of Friends, and the last issue of which any record can be found was made just before the outbreak of the Crimean war. But in 1813 an abridged edition was printed at New York, and was one of the books which influenced the great movement towards humanity then stirring in the young Republic.

At the present day, the reactionary wave which has overspread the world has led, both in England and America, to a new glorification of war. Peace is on the lips of governments and of individuals, but beneath the smooth surface the same passions, draped as they always have been [xxxiv] under fine names, are a menace to progress and to the higher life of mankind. The increase of armaments, the glorification of the military life, the fanaticism which regards organized robbery and murder as a sacred imperial mission, are the fruits of a spirit which has fallen as far below the standard of humanism as it has left behind it the precepts of a still outwardly acknowledged religion. At such a time the noble pleading of Erasmus has more than a merely literary or antiquarian interest. For the appeal of humanism still is, as it was then, to the dignity of human nature itself.

J. W. Mackail

[1]

AGAINST WAR

DULCE BELLUM INEXPERTIS↩

t is both an elegant proverb, and among all others, by the writings of many excellent authors, full often and solemnly used, Dulce bellum inexpertis, that is to say, War is sweet to them that know it not. There be some things among mortal men’s businesses, in the which how great danger and hurt there is, a man cannot perceive till he make a proof. The love and friendship of a great man is sweet to them that be not expert: he that hath had thereof experience, is afraid. It seemeth to be a gay and a glorious thing, to strut up and down among the nobles of the court, and to be occupied in the king’s business; but old men, to whom that thing by long experience is well known, do gladly abstain themselves from such felicity. It seemeth a pleasant thing to be in love with a young damsel; but that is unto them that have not yet perceived how much grief and bitterness is in such love. So after this manner of fashion, this proverb may be applied to every business that is adjoined with great peril and with many evils: the which no man will take on hand, but he that is young and wanteth experience of things.

t is both an elegant proverb, and among all others, by the writings of many excellent authors, full often and solemnly used, Dulce bellum inexpertis, that is to say, War is sweet to them that know it not. There be some things among mortal men’s businesses, in the which how great danger and hurt there is, a man cannot perceive till he make a proof. The love and friendship of a great man is sweet to them that be not expert: he that hath had thereof experience, is afraid. It seemeth to be a gay and a glorious thing, to strut up and down among the nobles of the court, and to be occupied in the king’s business; but old men, to whom that thing by long experience is well known, do gladly abstain themselves from such felicity. It seemeth a pleasant thing to be in love with a young damsel; but that is unto them that have not yet perceived how much grief and bitterness is in such love. So after this manner of fashion, this proverb may be applied to every business that is adjoined with great peril and with many evils: the which no man will take on hand, but he that is young and wanteth experience of things.

[4]

Aristotle, in his book of Rhetoric, showeth the cause why youth is more bold, and contrariwise old age more fearful: for unto young men lack of experience is cause of great boldness, and to the other, experience of many griefs engendereth fear and doubting. Then if there be anything in the world that should be taken in hand with fear and doubting, yea, that ought by all manner of means to be fled, to be withstood with prayer, and to be clean avoided, verily it is war; than which nothing is either more wicked, or more wretched, or that more farther destroyeth, or that never hand cleaveth sorer to, or doth more hurt, or is more horrible, and briefly to speak, nothing doth worse become a man (I will not say a Christian man) than war. And yet it is a wonder to speak of, how nowadays in every place, how lightly, and how for every trifling matter, it is taken in hand, how outrageously and barbarously it is gested and done, not only of heathen people, but also of Christian men; not only of secular men, but also of priests and bishops; not only of young men and of them that have no experience, but also of old men and of those that so often have had experience; not only of the common and movable vulgar people, but most specially of the princes, whose duty had been, by wisdom and reason, to set in a good order and to pacify the light and hasty movings of the foolish multitude. Nor there lack neither lawyers, nor yet divines, the [5] which are ready with their firebrands to kindle these things so abominable, and they encourage them that else were cold, and they privily provoke those to it that were weary thereof. And by these means it is come to that pass that war is a thing now so well accepted, that men wonder at him that is not pleased therewith. It is so much approved, that it is counted a wicked thing (and I had almost said heresy) to reprove this one thing, the which as it is above all other things most mischievous, so it is most wretched. But how more justly should this be wondered at, what evil spirit, what pestilence, what mischief, and what madness put first in man’s mind a thing so beyond measure beastly, that this most pleasant and reasonable creature Man, the which Nature hath brought forth to peace and benevolence, which one alone she hath brought forth to the help and succour of all other, should with so wild wilfulness, with so mad rages, run headlong one to destroy another? At the which thing he shall also much more marvel, whosoever would withdraw his mind from the opinions of the common people, and will turn it to behold the very pure strength and nature of things; and will apart behold with philosophical eyes the image of man on the one side, and the picture of war on the other side.

Then first of all if one would consider well but the behaviour and shape of man’s body shall he [6] not forthwith perceive that Nature, or rather God, hath shaped this creature, not to war, but to friendship, not to destruction, but to health, not to wrong, but to kindness and benevolence? For whereas Nature hath armed all other beasts with their own armour, as the violence of the bulls she hath armed with horns, the ramping lion with claws; to the boar she hath given the gnashing tusks; she hath armed the elephant with a long trump snout, besides his great huge body and hardness of the skin; she hath fenced the crocodile with a skin as hard as a plate; to the dolphin fish she hath given fins instead of a dart; the porcupine she defendeth with thorns; the ray and thornback with sharp prickles; to the cock she hath given strong spurs; some she fenceth with a shell, some with a hard hide, as it were thick leather, or bark of a tree; some she provideth to save by swiftness of flight, as doves; and to some she hath given venom instead of a weapon; to some she hath given a much horrible and ugly look, she hath given terrible eyes and grunting voice; and she hath also set among some of them continual dissension and debate—man alone she hath brought forth all naked, weak, tender, and without any armour, with most soft flesh and smooth skin. There is nothing at all in all his members that may seem to be ordained to war, or to any violence. I will not say at this time, that where all other beasts, anon as they are brought forth, [7] they are able of themselves to get their food. Man alone cometh so forth, that a long season after he is born, he dependeth altogether on the help of others. He can neither speak nor go, nor yet take meat; he desireth help only by his infant crying: so that a man may, at the least way, by this conject, that this creature alone was born all to love and amity, which specially increaseth and is fast knit together by good turns done eftsoons of one to another. And for this cause Nature would, that a man should not so much thank her, for the gift of life, which she hath given unto him, as he should thank kindness and benevolence, whereby he might evidently understand himself, that he was altogether dedicate and bounden to the gods of graces, that is to say, to kindness, benevolence, and amity. And besides this Nature hath given unto man a countenance not terrible and loathly, as unto other brute beasts; but meek and demure, representing the very tokens of love and benevolence. She hath given him amiable eyes, and in them assured marks of the inward mind. She hath ordained him arms to clip and embrace. She hath given him the wit and understanding to kiss: whereby the very minds and hearts of men should be coupled together, even as though they touched each other. Unto man alone she hath given laughing, a token of good cheer and gladness. To man alone she hath given weeping tears, as it were a pledge or token of meekness and mercy. Yea, and [8] she hath given him a voice not threatening and horrible, as unto other brute beasts, but amiable and pleasant. Nature not yet content with all this, she hath given unto man alone the commodity of speech and reasoning: the which things verily may specially both get and nourish benevolence, so that nothing at all should be done among men by violence.

She hath endued man with hatred of solitariness, and with love of company. She hath utterly sown in man the very seeds of benevolence. She hath so done, that the selfsame thing, that is most wholesome, should be most sweet and delectable. For what is more delectable than a friend? And again, what thing is more necessary? Moreover, if a man might lead all his life most profitably without any meddling with other men, yet nothing would seem pleasant without a fellow: except a man would cast off all humanity, and forsaking his own kind would become a beast.

Besides all this, Nature hath endued man with knowledge of liberal sciences and a fervent desire of knowledge: which thing as it doth most specially withdraw man’s wit from all beastly wildness, so hath it a special grace to get and knit together love and friendship. For I dare boldly say, that neither affinity nor yet kindred doth bind the minds of men together with straiter and surer bands of amity, than doth the fellowship of them that be learned in good letters and honest studies. [9] And above all this, Nature hath divided among men by a marvellous variety the gifts, as well of the soul as of the body, to the intent truly that every man might find in every singular person one thing or other, which they should either love or praise for the excellency thereof; or else greatly desire and make much of it, for the need and profit that cometh thereof. Finally she hath endowed man with a spark of a godly mind: so that though he see no reward, yet of his own courage he delighteth to do every man good: for unto God it is most proper and natural, by his benefit, to do everybody good. Else what meaneth it, that we rejoice and conceive in our minds no little pleasure when we perceive that any creature is by our means preserved.

Moreover God hath ordained man in this world, as it were the very image of himself, to the intent, that he, as it were a god on earth, should provide for the wealth of all creatures. And this thing the very brute beasts do also perceive, for we may see, that not only the tame beasts, but also the leopards, lions, and other more fierce and wild, when they be in any great jeopardy, they flee to man for succour. So man is, when all things fail, the last refuge to all manner of creatures. He is unto them all the very assured altar and sanctuary.

I have here painted out to you the image of man as well as I can. On the other side (if it like [10] you) against the figure of Man, let us portray the fashion and shape of War.

Now, then, imagine in thy mind, that thou dost behold two hosts of barbarous people, of whom the look is fierce and cruel, and the voice horrible; the terrible and fearful rustling and glistering of their harness and weapons; the unlovely murmur of so huge a multitude; the eyes sternly menacing; the bloody blasts and terrible sounds of trumpets and clarions; the thundering of the guns, no less fearful than thunder indeed, but much more hurtful; the frenzied cry and clamour, the furious and mad running together, the outrageous slaughter, the cruel chances of them that flee and of those that are stricken down and slain, the heaps of slaughters, the fields overflowed with blood, the rivers dyed red with man’s blood. And it chanceth oftentimes, that the brother fighteth with the brother, one kinsman with another, friend against friend; and in that common furious desire ofttimes one thrusteth his weapon quite through the body of another that never gave him so much as a foul word. Verily, this tragedy containeth so many mischiefs, that it would abhor any man’s heart to speak thereof. I will let pass to speak of the hurts which are in comparison of the other but light and common, as the treading down and destroying of the corn all about, the burning of towns, the villages fired, the driving away of cattle, the ravishing of maidens, the old men led [11] forth in captivity, the robbing of churches, and all things confounded and full of thefts, pillages, and violence. Neither I will not speak now of those things which are wont to follow the most happy and most just war of all.

The poor commons pillaged, the nobles overcharged; so many old men of their children bereaved, yea, and slain also in the slaughter of their children; so many old women destitute, whom sorrow more cruelly slayeth than the weapon itself; so many honest wives become widows, so many children fatherless, so many lamentable houses, so many rich men brought to extreme poverty. And what needeth it here to speak of the destruction of good manners, since there is no man but knoweth right well that the universal pestilence of all mischievous living proceedeth at once from war. Thereof cometh despising of virtue and godly living; thereof cometh, that the laws are neglected and not regarded; thereof cometh a prompt and a ready stomach, boldly to do every mischievous deed. Out of this fountain spring so huge great companies of thieves, robbers, sacrilegers, and murderers. And what is most grievous of all, this mischievous pestilence cannot keep herself within her bounds; but after it is begun in some one corner, it doth not only (as a contagious disease) spread abroad and infect the countries near adjoining to it, but also it draweth into that common tumult and troublous business [12] the countries that be very far off, either for need, or by reason of affinity, or else by occasion of some league made. Yea and moreover, one war springeth of another: of a dissembled war there cometh war indeed, and of a very small, a right great war hath risen. Nor it chanceth oftentimes none otherwise in these things than it is feigned of the monster, which lay in the lake or pond called Lerna.

For these causes, I trow, the old poets, the which most sagely perceived the power and nature of things, and with most meet feignings covertly shadowed the same, have left in writing, that war was sent out of hell: nor every one of the Furies was not meet and convenient to bring about this business, but the most pestilent and mischievous of them all was chosen out for the nonce, which hath a thousand names, and a thousand crafts to do hurt. She being armed with a thousand serpents, bloweth before her her fiendish trumpet. Pan with furious ruffling encumbereth every place. Bellona shaketh her furious flail. And then the wicked furiousness himself, when he hath undone all knots and broken all bonds, rusheth out with bloody mouth horrible to behold.

The grammarians perceived right well these things, of the which some will, that war have his name by contrary meaning of the word Bellum, that is to say fair, because it hath nothing good nor fair. Nor bellum, that is for to say war, is none [13] otherwise called Bellum, that is to say fair, than the furies are called Eumenides, that is to say meek, because they are wilful and contrary to all meekness. And some grammarians think rather, that bellum, war, should be derived out of this word Belva, that is for to say, a brute beast: forasmuch as it belongeth to brute beasts, and not unto men, to run together, each to destroy each other. But it seemeth to me far to pass all wild and all brute beastliness, to fight together with weapons.

First, for there are many of the brute beasts, each in his kind, that agree and live in a gentle fashion together, and they go together in herds and flocks, and each helpeth to defend the other. Nor is it the nature of all wild beasts to fight, for some are harmless, as does and hares. But they that are the most fierce of all, as lions, wolves, and tigers, do not make war among themselves as we do. One dog eateth not another. The lions, though they be fierce and cruel, yet they fight not among themselves. One dragon is in peace with another. And there is agreement among poisonous serpents. But unto man there is no wild or cruel beast more hurtful than man.

Again, when the brute beasts fight, they fight with their own natural armour: we men, above nature, to the destruction of men, arm ourselves with armour, invented by craft of the devil. Nor the wild beasts are not cruel for every cause; but either when hunger maketh them fierce, or else [14] when they perceive themselves to be hunted and pursued to the death, or else when they fear lest their younglings should take any harm or be stolen from them. But (O good Lord) for what trifling causes what tragedies of war do we stir up? For most vain titles, for childish wrath, for a wench, yea, and for causes much more scornful than these, we be inflamed to fight.

Moreover, when the brute beasts fight, then war is one for one, yea, and that is very short. And when the battle is sorest fought, yet is there not past one or two, that goeth away sore wounded. When was it ever heard that an hundred thousand brute beasts were slain at one time fighting and tearing one another: which thing men do full oft and in many places? And besides this, whereas some wild beasts have natural debate with some other that be of a contrary kind, so again there be some with which they lovingly agree in a sure amity. But man with man, and each with other, have among them continual war; nor is there league sure enough among any men. So that whatsoever it be, that hath gone out of kind, it hath gone out of kind into a worse fashion, than if Nature herself had engendered therein a malice at the beginning.

Will ye see how beastly, how foul, and how unworthy a thing war is for man? Did ye never behold a lion let loose unto a bear? What gapings, what roarings, what grisly gnashing, what tearing [15] of their flesh, is there? He trembleth that beholdeth them, yea, though he stand sure and safe enough from them. But how much more grisly a sight is it, how much more outrageous and cruel, to behold man to fight with man, arrayed with so much armour, and with so many weapons? I beseech you, who would believe that they were men, if it were not because war is a thing so much in custom that no man marvelleth at it? Their eyes glow like fire, their faces be pale, their marching forth is like men in a fury, their voice screeching and grunting, their cry and frenzied clamour; all is iron, their harness and weapons jingling and clattering, and the guns thundering. It might have been better suffered, if man, for lack of meat and drink, should have fought with man, to the intent he might devour his flesh and drink his blood: albeit, it is come also now to that pass, that some there be that do it more of hatred than either for hunger or for thirst. But now this same thing is done more cruelly, with weapons envenomed, and with devilish engines. So that nowhere may be perceived any token of man. Trow ye that Nature could here know it was the same thing, that she sometime had wrought with her own hands? And if any man would inform her, that it were man that she beheld in such array, might she not well, with great wondering, say these words?

“What new manner of pageant is this that I behold? What devil of hell hath brought us forth [16] this monster. There be some that call me a stepmother, because that among so great heaps of things of my making I have brought forth some venomous things (and yet have I ordained the selfsame venomous things for man’s behoof); and because I have made some beasts very fierce and perilous: and yet is there no beast so wild nor so perilous, but that by craft and diligence he may be made tame and gentle. By man’s diligent labour the lions have been made tame, the dragons meek, and the bears obedient. But what is this, that worse is than any stepmother, which hath brought us forth this new unreasonable brute beast, the pestilence and mischief of all this world? One beast alone I brought forth wholly dedicate to be benevolent, pleasant, friendly, and wholesome to all other. What hath chanced, that this creature is changed into such a brute beast? I perceive nothing of the creature man, which I myself made. What evil spirit hath thus defiled my work? What witch hath bewitched the mind of man, and transformed it into such brutishness? What sorceress hath thus turned him out of his kindly shape? I command and would that the wretched creature should behold himself in a glass. But, alas, what shall the eyes see, where the mind is away? Yet behold thyself (if thou canst), thou furious warrior, and see if thou mayst by any means recover thyself again. From whence hast thou that threatening crest upon thy head? From whence hast thou [17] that shining helmet? From whence are those iron horns? Whence cometh it, that thine elbows are so sharp and piked? Where hadst thou those scales? Where hadst thou those brazen teeth? Of whence are those hard plates? Whence are those deadly weapons? From whence cometh to thee this voice more horrible than of a wild beast? What a look and countenance hast thou more terrible than of a brute beast? Where hast thou gotten this thunder and lightning, both more fearful and hurtful than is the very thunder and lightning itself? I formed thee a goodly creature; what came into thy mind, that thou wouldst thus transform thyself into so cruel and so beastly fashion, that there is no brute beast so unreasonable in comparison unto man?”

These words, and many other such like, I suppose, the Dame Nature, the worker of all things, would say. Then since man is such as is showed before that he is, and that war is such a thing, like as too oft we have felt and known, it seemeth to me no small wonder, what ill spirit, what disease, or what mishap, first put into man’s mind, that he would bathe his mortal weapon in the blood of man. It must needs be, that men mounted up to so great madness by divers degrees. For there was never man yet (as Juvenal saith) that was suddenly most graceless of all. And always things the worst have crept in among men’s manners of living, under the shadow and shape of [18] goodness. For some time those men that were in the beginning of the world led their lives in woods; they went naked, they had no walled towns, nor houses to put their heads in: it happened otherwhile that they were sore grieved and destroyed with wild beasts. Wherefore with them first of all, men made war, and he was esteemed a mighty strong man, and a captain, that could best defend mankind from the violence of wild beasts. Yea, and it seemed to them a thing most equable to strangle the stranglers, and to slay the slayers, namely, when the wild beast, not provoked by us for any hurt to them done, would wilfully set upon us. And so by reason that this was counted a thing most worthy of praise (for hereof it rose that Hercules was made a god), the lusty-stomached young men began all about to hunt and chase the wild beasts, and as a token of their valiant victory the skins of such beasts as they slew were set up in such places as the people might behold them. Besides this they were not contented to slay the wild beasts, but they used to wear their skins to keep them from the cold in winter. These were the first slaughters that men used: these were their spoils and robberies. After this, they went so farforth, that they were bold to do a thing which Pythagoras thought to be very wicked; and it might seem to us also a thing monstrous, if custom were not, which hath so great strength in every place: that by custom it was reputed in [19] some countries a much charitable deed if a man would, when his father was very old, first sore beat him, and after thrust him headlong into a pit, and so bereave him of his life, by whom it chanced him to have the gift of life. It was counted a holy thing for a man to feed on the flesh of his own kinsmen and friends. They thought it a goodly thing, that a virgin should be made common to the people in the temple of Venus. And many other things, more abominable than these: of which if a man should now but only speak, every man would abhor to hear him. Surely there is nothing so ungracious, nor nothing so cruel, but men will hold therewith, if it be once approved by custom. Then will ye hear, what a deed they durst at the last do? They were not abashed to eat the carcases of the wild beasts that were slain, to tear the unsavoury flesh with their teeth, to drink the blood, to suck out the matter of them, and (as Ovid saith) to hide the beasts’ bowels within their own. And although at that time it seemed to be an outrageous deed unto them that were of a more mild and gentle courage: yet was it generally allowed, and all by reason of custom and commodity. Yet were they not so content. For they went from the slaying of noisome wild beasts, to kill the harmless beasts, and such as did no hurt at all. They waxed cruel everywhere upon the poor sheep, a beast without fraud or guile. They slew the hare, for none other offence, but [20] because he was a good fat dish of meat to feed upon. Nor they forbare not to kill the tame ox, which had a long season, with his sore labour, nourished the unkind household. They spared no kind of beasts, of fowls, nor of fishes. Yea, and the tyranny of gluttony went so farforth that there was no beast anywhere that could be sure from the cruelty of man. Yea, and custom persuaded this also, that it seemed no cruelty at all to slay any manner of beast, whatsoever it was, so they abstained from manslaughter. Now peradventure it lieth in our power to keep out vices, that they enter not upon the manners of men, in like manner as it lieth in our power to keep out the sea, that it break not in upon us; but when the sea is once broken in, it passeth our power to restrain it within any bounds. So either of them both once let in, they will not be ruled, as we would, but run forth headlong whithersoever their own rage carrieth them. And so after that men had been exercised with such beginnings to slaughter, wrath anon enticed man to set upon man, either with staff, or with stone, or else with his fist. For as yet, I think they used no other weapons. And now had they learned by the killing of beasts, that man also might soon and easily be slain with little labour. But this cruelty remained betwixt singular persons, so that yet there was no great number of men that fought together, but as it chanced one man against another. And besides this, there [21] was no small colour of equity, if a man slew his enemy; yea, and shortly after, it was a great praise to a man to slay a violent and a mischievous man, and to rid him out of the world, such devilish and cruel caitiffs, as men say Cacus and Busiris were. For we see plainly, that for such causes, Hercules was greatly praised. And in process of time, many assembled to take part together, either as affinity, or as neighbourhood, or kindred bound them. And what is now robbery was then war. And they fought then with stones, or with stakes, a little burned at the ends. A little river, a rock, or such other like thing, chancing to be between them, made an end of their battle.

In the mean season, while fierceness by use increaseth, while wrath is grown great, and ambition hot and vehement, by ingenious craft they arm their furious violence. They devise harness, such as it is, to fence them with. They invent weapons to destroy their enemies with. Thus now by few and few, now with greater company, and now armed they begin to fight. Nor to this manifest madness they forget not to give honour. For they call it Bellum, that is to say, a fair thing; yea, and they repute it a virtuous deed, if a man, with the jeopardy of his own life, manly resist and defend from the violence of his enemies, his wife, children, beasts, and household. And by little and little, malice grew so great, with the high esteeming of other things, that one city began to send [22] defiance and make war to another, country against country, and realm against realm. And though the thing of itself was then most cruel, yet all this while there remained in them certain tokens, whereby they might be known for men: for such goods as by violence were taken away were asked and required again by an herald at arms; the gods were called to witness; yea, and when they were ranged in battle, they would reason the matter ere they fought. And in the battle they used but homely weapons, nor they used neither guile nor deceit, but only strength. It was not lawful for a man to strike his enemy till the sign of battle was given; nor was it not lawful to fight after the sounding of the retreat. And for conclusion, they fought more to show their manliness and for praise, than they coveted to slay. Nor all this while they armed them not, but against strangers, the which they called hostes, as they had been hospites, their guests. Of this rose empires, of the which there was never none yet in any nation, but it was gotten with the great shedding of man’s blood. And since that time there hath followed continual course of war, while one eftsoons laboureth to put another out of his empire, and to set himself in. After all this, when the empires came once into their hands that were most ungracious of all other, they made war upon whosoever pleased them; nor were they not in greatest peril and danger of war that had most deserved [23] to be punished, but they that by fortune had gotten great riches. And now they made not war to get praise and fame, but to get the vile muck of the world, or else some other thing far worse than that.

I think not the contrary, but that the great, wise man Pythagoras meant these things when he by a proper device of philosophy frightened the unlearned multitude of people from the slaying of silly beasts. For he perceived, it should at length come to pass, that he which (by no injury provoked) was accustomed to spill the blood of a harmless beast, would in his anger, being provoked by injury, not fear to slay a man.

War, what other thing else is it than a common manslaughter of many men together, and a robbery, the which, the farther it sprawleth abroad, the more mischievous it is? But many gross gentlemen nowadays laugh merrily at these things, as though they were the dreams and dotings of schoolmen, the which, saving the shape, have no point of manhood, yet seem they in their own conceit to be gods. And yet of those beginnings, we see we be run so far in madness, that we do naught else all our life-days. We war continually, city with city, prince with prince, people with people, yea, and (it that the heathen people confess to be a wicked thing) cousin with cousin, alliance with alliance, brother with brother, the son with the father, yea, and that I esteem more cruel [24] than all these things, a Christian man against another man; and yet furthermore, I will say that I am very loath to do, which is a thing most cruel of all, one Christian man with another Christian man. Oh, blindness of man’s mind! at those things no man marvelleth, no man abhorreth them. There be some that rejoice at them, and praise them above the moon: and the thing which is more than devilish, they call a holy thing. Old men, crooked for age, make war, priests make war, monks go forth to war; yea, and with a thing so devilish we mingle Christ. The battles ranged, they encounter the one the other, bearing before them the sign of the Cross, which thing alone might at the leastwise admonish us by what means it should become Christian men to overcome.

But we run headlong each to destroy other, even from that heavenly sacrifice of the altar, whereby is represented that perfect and ineffable knitting together of all Christian men. And of so wicked a thing, we make Christ both author and witness. Where is the kingdom of the devil, if it be not in war? Why draw we Christ into war, with whom a brothel-house agreeth more than war? Saint Paul disdaineth, that there should be any so great discord among Christian men, that they should need any judge to discuss the matter between them. What if he should come and behold us now through all the world, warring for every light and trifling cause, striving more [25] cruelly than ever did any heathen people, and more cruelly than any barbarous people? Yea, and ye shall see it done by the authority, exhortations, and furtherings of those that represent Christ, the prince of peace and very bishop that all things knitteth together by peace and of those that salute the people with good luck of peace. Nor is it not unknown to me what these unlearned people say (a good while since) against me in this matter, whose winnings arise of the common evils. They say thus: We make war against our wills: for we be constrained by the ungracious deeds of other. We make war but for our right. And if there come any hurt thereof, thank them that be causers of it. But let these men hold their tongues awhile, and I shall after, in place convenient, avoid all their cavillations, and pluck off that false visor wherewith we hide all our malice.

But first as I have above compared man with war, that is to say, the creature most demure with a thing most outrageous, to the intent that cruelty might the better be perceived: so will I compare war and peace together, the thing most wretched, and most mischievous, with the best and most wealthy thing that is. And so at last shall appear, how great madness it is, with so great tumult, with so great labours, with such intolerable expenses, with so many calamities, affectionately to desire war: whereas agreement might be bought with a far less price.

[26]

First of all, what in all this world is more sweet or better than amity or love? Truly nothing. And I pray you, what other thing is peace than amity and love among men, like as war on the other side is naught else but dissension and debate of many men together? And surely the property of good things is such, that the broader they be spread, the more profit and commodity cometh of them. Farther, if the love of one singular person with another be so sweet and delectable, how great should the felicity be if realm with realm, and nation with nation, were coupled together, with the band of amity and love? On the other side, the nature of evil things is such, that the farther they sprawl abroad, the more worthy they are to be called evil, as they be indeed. Then if it be a wretched thing, if it be an ungracious thing, that one man armed should fight with another, how much more miserable, how much more mischievous is it, that the selfsame thing should be done with so many thousands together? By love and peace the small things increase and wax great, by discord and debate the great things decay and come to naught. Peace is the mother and nurse of all good things. War suddenly and at once overthroweth, destroyeth, and utterly fordoeth everything that is pleasant and fair, and bringeth in among men a monster of all mischievous things.

In the time of peace (none otherwise than as if [27] the lusty springtime should show and shine in men’s businesses) the fields are tilled, the gardens and orchards freshly flourish, the beasts pasture merrily; gay manours in the country are edified, the towns are builded, where as need is reparations are done, the buildings are heightened and augmented, riches increase, pleasures are nourished, the laws are executed, the common wealth flourisheth, religion is fervent, right reigneth, gentleness is used, craftsmen are busily exercised, the poor men’s gain is more plentiful, the wealthiness of the rich men is more gay and goodly, the studies of most honest learnings flourish, youth is well taught, the aged folks have quiet and rest, maidens are luckily married, mothers are praised for bringing forth of children like to their progenitors, the good men prosper and do well, and the evil men do less offence.

But as soon as the cruel tempest of war cometh on us, good Lord, how great a flood of mischiefs occupieth, overfloweth, and drowneth all together. The fair herds of beasts are driven away, the goodly corn is trodden down and destroyed, the good husbandmen are slain, the villages are burned up, the most wealthy cities, that have flourished so many winters, with that one storm are overthrown, destroyed, and brought to naught: so much readier and prompter men are to do hurt than good. The good citizens are robbed and spoiled of their goods by cursed [28] thieves and murderers. Every place is full of fear, of wailing, complaining, and lamenting. The craftsmen stand idle; the poor men must either die for hunger, or fall to stealing. The rich men either stand and sorrow for their goods, that be plucked and snatched from them, or else they stand in great doubt to lose such goods as they have left them: so that they be on every side woebegone. The maidens, either they be not married at all, or else if they be married, their marriages are sorrowful and lamentable. Wives, being destitute of their husbands, lie at home without any fruit of children, the laws are laid aside, gentleness is laughed to scorn, right is clean exiled, religion is set at naught, hallowed and unhallowed things all are one, youth is corrupted with all manner of vices, the old folk wail and weep, and wish themselves out of the world, there is no honour given unto the study of good letters. Finally, there is no tongue can tell the harm and mischief that we feel in war.

Perchance war might be the better suffered, if it made us but only wretched and needy; but it maketh us ungracious, and also full of unhappiness. And I think Peace likewise should be much made of, if it were but only because it maketh us more wealthy and better in our living. Alas, there be too many already, yea, and more than too many mischiefs and evils, with the which the wretched life of man (whether he will or no) is [29] continually vexed, tormented, and utterly consumed.

It is near hand two thousand years since the physicians had knowledge of three hundred divers notable sicknesses by name, besides other small sicknesses and new, as daily spring among us, and besides age also, which is of itself a sickness inevitable.

We read that in one place whole cities have been destroyed with earthquakes. We read, also, that in another place there have been cities altogether burnt with lightning; how in another place whole regions have been swallowed up with opening of the earth, towns by undermining have fallen to the ground; so that I need not here to remember what a great multitude of men are daily destroyed by divers chances, which be not regarded because they happen so often: as sudden breaking out of the sea and of great floods, falling down of hills and houses, poison, wild beasts, meat, drink, and sleep. One hath been strangled with drinking of a hair in a draught of milk, another hath been choked with a little grapestone, another with a fishbone sticking in his throat. There hath been, that sudden joy hath killed out of hand: for it is less wonder of them that die for vehement sorrow. Besides all this, what mortal pestilence see we in every place. There is no part of the world, that is not subject to peril and danger of man’s life, which life of itself also is most [30] fugitive. So manifold mischances and evils assail man on every side that not without cause Homer did say: Man was the most wretched of all creatures living.

But forasmuch these mischances cannot lightly be eschewed, nor they happen not through our fault, they make us but only wretched, and not ungracious withal. What pleasure is it then for them that be subject already to so many miserable chances, willingly to seek and procure themselves another mischief more than they had before, as though they yet wanted misery? Yea, they procure not a light evil, but such an evil that is worse than all the others, so mischievous, that it alone passeth all the others; so abundant, that in itself alone is comprehended all ungraciousness; so pestilent, that it maketh us all alike wicked as wretched, it maketh us full of all misery, and yet not worthy to be pitied.