John Streater, A Glympse of that Jewel Libertie (31 March, 1653).

Note: This is part of the Leveller Collection of Tracts and Pamphlets.

Editor’s Introduction

John Streater (birth?? - 1687) was a radical republican who was a printer and bookseller before joining the Parliamentary army in 1642. He was a fierce opponent of Cromwell and was imprisoned several times for his views, the most radical of which suggested that those who were oppressed had the right to assassinate a tyrant, as he suggested in his pamphlet on Julius Caesar, Politick Commentary upon the Life of Caius July Caesar (1654) and his republication of Edward Sexby’s Killing No Murder (1659).

This pamphlet “That Jewel Liberty” (1653) was published the month before Cromwell dissolved the Long Parliament and it laid out his fears that something like this would happen unless the English people were prepared to defend their liberties from unscrupulous, corrupt, and power hungry politicians. He was not hopeful that the people would do this as they were “slavish” towards all authority.

The pamphlet is full of warnings about the dangers of “party” and “faction”, and that powerful men would use their political office to become more powerful. Hence there was a need for a system of checks and balances to make this more difficult, such as annual elections (even for judges); laws against politicians and bureaucrats taking bribes; the simplification of the laws so that ordinary people could understand what their rights and duties were; the duty of lower magistrates to challenge the rulings of their superiors if they thought the liberties and rights of the people were being harmed; and the duty of Parliament to control the army by strictly limiting its funding.

Streater’s political thought was based on the primacy of “natural law” and the consent of the governed. If this consent was ignored or violated, if their lives, liberties and “estates” (property) were harmed, then the people had the right to take up arms to resist a tyrannical government or monarch. As he concluded the pamphlet “if all lawful means fail, arms may be made use of” in order to “preserv(e) just and equal Freedom.”

Bibliographical Information

ID Number

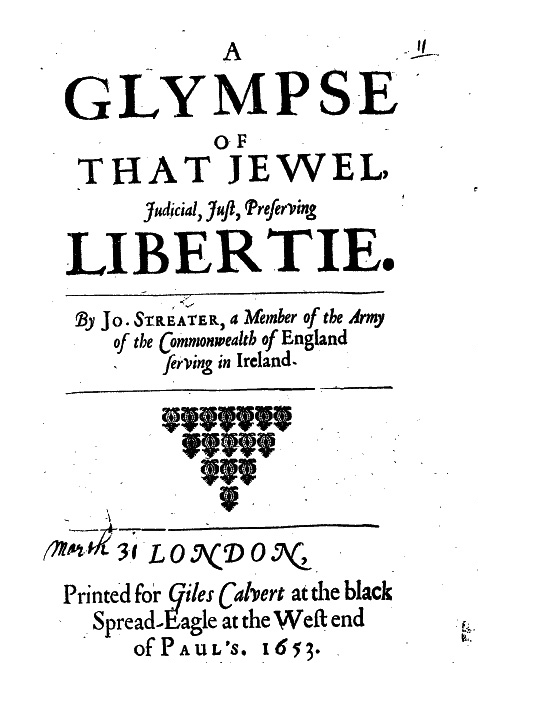

T.236 [1653.03.31] John Streater, A Glympse of that Jewel Libertie (31 March, 1653).

Full title

John Streater, A Glympse of that Jevvel, Judicial, Just, Preserving libertie. By Jo. Streater, a member of the Army of the Commonwealth of England serving in Ireland.

London, Printed for Giles Calvert at the black Spread-Eagle at the West end

of Paul’s. 1653.

Estimated date of publication

31 March, 1653.

Thomason Tracts Catalog information

TT2, p. 9; Thomason E.690 [11]

Text of Pamphlet

To the READER.

IT is the general temper of People, to slight the looking after matters of publick concernment, they conceiving, that they are matters too high for common capacities, and more becoming States-men. That that I shall urge, is, that every Member of the Common-wealth, of right and in duty, ought to watch to their Liberty, and prevent Absoluteness in persons of great Trust. True, thou art to be obedient to Higher Powers, but that command or exhortation obligeth thee no farther then the Higher Powers act for the general good.

Suppose that the Higher Powers should command thee to slay thy fellow Member of the Commonwealth, wouldst thou obey them therein? but if they command thee to preserve and defend thy fellow Member, his Liberty, Life, Estate, thou art in pursuance thereof bound to hazard thine; That that thou obeyest them in, thou oughtest to be able to judg whether he doth right therein or not.

Be not mistaken in higher Powers, they ought to be bound up by a law of mutuall consent of the Generality. Alexander grew a cruel Tyrant after his flatterers told him he was a God. ’Tis the onely way to give the advantage into the hands of those thou chusest to execute thy Laws of consent, to make themselves Masters of the common Liberty, to set too high an estimation on them, or think it is theirs of right: Yet the Authoritie that should preserve equity between man and man, should not bee slighted, for by that means Authority will be weakned.

Make good thy claim to Equity, and to thy right in election of persons in trust; Indeavour to understand thy Liberty; since Monarchy is destroyed, thou hast a perfect equalitie, in respect of thy Rights and Priviledges. Fear not any, be they never so powerfull, if thou hast Equitie on thy side. Do not seek and scrape for favours, nor make parties to obtain thy desires; thou knowest not what thou doest; therein thou betrayest thy Self, thy Libertie, and thy Countrie. Do not endeavour to prejudicate. If thou suest for Right, let thy Judges stand in fear of doing thee wrong. Is Equitie and Justice theirs to give? No, it is their dutie; it is not their dutie to tire thee with delayes. Endeavour to know the Power of thy Judges, thy right, the Lawes; so that though it be not fit or safe for thee to be a Judg in thy own Cause; yet that thou mayest judg him that judgeth thee. And to the end that thou mayest know the position of Affaires, converse often with knowing men: and let knowing men endeavour to inform the lesse knowing.

Lycurgus accounted this an eminent prop or pillar to the State of Lacedemon, that his Citizens should converse and confer often of their Liberties, of Government, of Laws, of Peace, of War; and every one to be as able to rule, as those that are chosen to rule: It is hard to rob such a people of their Liberties. Likewise, one Rule would be wel to be observed, That if places of Government were made lesse profitable, they would be lesse desired: when it must be undergone for conscience sake, esteem of none but such as are truly virtuous. Those that endeavour to enrich themselves, children, or kindred, are not persons fit for trust. It is thy duty to watch to thy Liberty; so it is also thy duty to watch to the Execution of the Lawes that are for thy Preservation. It is not onely thy duty to watch to thy owne Liberty, but to thy neighbours Libertie; nay thy poor neighbours Libertie, that the rich and mighty oppresse him not. Hercules was deified for imploying his strength in delivering the oppressed out of the hands of the oppressors.

The way that the Nimrods of this world grow mighty and powerful by, is to oblige such as may be hurtfull to them, so that they may dis-ingage them from joyning with the generality in defence of their Libertie; so that the Generalitie having their Captains taken away, become a prey to their Absolutenesse; as Æsop’s sheep having their dogs delivered to the Wolves, became at length a prey unto the Wolves.

Flatter none of thy fellow-members of the Commonwealth with Titles, as, High and Mighty, or Excellent; The Title of Honor, or Honorable, is the highest mark of desert that a Member of a Commonwealth is fit to attain unto or bear.

Reader, Here thou art guided to know thy self, to know others; Their Power and thy Liberty. There is no one thing under Heaven the cause of misery by the assumed Lording of Usurpers, but Thy not knowing thy Liberties and Rights.

Confusedly have I presented thee with a Glympse of that, which I doubt not, if thou wilt cast thine eye to behold, thou wilt discover a greater light herein, then is discerned by him that is a wel-wisher to Publick Preserving Libertie.

J. S.

A glimpse of that Jewel; Judicial, just preserving Libertie.

FOrasmuch as Monarchie is destroyed amongst us, it is convenient, and much in order to the preservation of the just rights of every member of the Common-wealth, that they should understand their Rights, Priviledges and Liberties. It was observable, that when Rome grow to that greatnesse, that by its Vertues and Arms it not onely preserved it self, but gave Lawes to other Cities, Common-wealths and Princes, it was when every member of that Common-wealth perfectly understood the mysteries of State, and were competent Judges in all matters and causes arising in the Common-wealth, as also of the disadvantage or advantage of either Peace or Warr.

Secondly, The great preservation and cause of the growth of the Common-wealth of Rome, after their shaking off that yoak, Monarchie, was the yearly election of all Officers in greatest trust, both Military and Civil; for by this means they were prevented of obtaining to those advantages of making themselves Masters of the common Liberty.

Thirdly, By this means also every one of the Commonwealth that affected Government, had hope of having share of the Government; therefore they endeavoured to improve themselves so, as to become capable of such and such trusts in Government: So that almost every one was an able defendant of their Libertie and Countrie: Therefore the greatnesse of that Empire is not to be admired; for it is hard to oppose such a composed Bodie, by such a Body or power as is acted or supported by the Counsels or Interests of few. Romes power began to decline, when the power and secret reasons of State were assumed by few, or one person. They never received such a stroak at their Libertie, as when Cæsar was made perpetual Dictator: Therefore since we finde Rome strip’d of her liberty and glory, let England watch to hers: and to that end let us take notice of the wayes how persons that affect absolute Government endeavour the accomplishment thereof; the which may be found by knowing what should be on the contrary to preserve it from that danger.

1. A Government should or ought to be for the conservation of mankinde: for as government and Law is nothing else but a rational restraint of absolute Libertie - so it is also a rational restraint of absolutenesse in commanding: And natural equity teacheth us, 1. That no one should desire profit or honour by the prejudicing of another. 2. That no one should do or wish that to another, which he would not should be done unto himself. Now seeing in Government that every persons interest and good in that bodie is concerned, ’tis cleer that the power is essentially in the people. But forasmuch as the Common-wealth of England is so large, that it cannot meet as Rome, Athens, Sparta, or Corinth, in a Market place, or in a Theater, in Councel, Judgment, or matters of State; therefore it hath been the consent of the Commonwealth of England, for many hundred years, to contract their Authority in a Representative or Parliament: Indeed, their Kings never had any other power, then as their chiefest Minister of State and was no other then a member of the Common-wealth, bound up by the same Law and Rules of government; witness the Oath of Coronation, as also the Oath administred to all Justices, both of the peace, and the several Benches, An. 18. Ed. 3. St. 3. in these words, You shall swear well and truly to serve your Lord the King; and the People. Likewise the King often appeared by his Atturney at the Bar of the Common-wealth, sometimes as Plaintiff, sometimes as Defendant, in several cases at Law; nay, when the late King was at the height of his Supremacy, Hambden and Chambers brought their Action against him at common Law, in the case of Ship-money; they knowing that the power to impose Laws and Taxes, consisted in the Consent of the people represented in Parliament.

It was notably observed by Plutarch, of Solon; being chosen chief in Government of the Common-wealth of Athens, the people being assembled in the Market place, he coming to sit in Councel with them, when he drew nigh the Assembly of the people, he caused the Rod that was born before him (which was a mark or ensigne of Government) the head to be turned downward, to signifie, that essentially the Government was in the People.

2. Therefore seeing that Power and Government is essentially the right of the People, for the good of the generality, or the greatest number, it is to be presumed, it must be in opposition to some, namely the vicious and foolish; A rod for the fools back, as Solomon sayes. Plato saith. That true Government is when men govern by Vertue and Wisdome; which is in opposition to vice and folly, as afore mentioned.

3. To prevent the having the Power wrested out of the hands of the People by an assumed absolutenesse of persons in trust; Suffer not great power to continue longer then one year in the hands of any one member of the Common-wealth. Doubtless, it was upon the same reason of State that that Act of Parliament was pass’d An. 4. Ed. 3. cap. 14. wherein it was ordained, that Parliaments should be chosen once a yeer, or oftner, if need be. One reason why it is not for the good of the Publick for long continuance of persons in trust, is because that continuance in any one action or undertaking whatsoever, burdeneth the spirits; for the spirits that give life to all action, most usually spend vigorously upon noveltie; but being spent, are no other then as tired jades, that leave one half of their work undone. A second reason why a prefixt time for the continuance of persons in Publick trusts (at one year, not more, rather less) would be much to the advantage of the publick, is, when they see one year is the time of their continuance, they will be desirous to do something in that time worthie of themselves, to preserve their memory, and to obtain a good opinion of the Publick; they will account it unworthy of themselves to leave any thing undone that should be for the good of the Publick, or that they should not relieve distressed persons that have made their applications to them for redresse: by this means Petitions wil not lie dormant three, four, or five years. Thirdly, It will oblige them to do that which shall indeed be for the good of the Publick, they knowing, that at the determination of the prefixt time of their Trust, they are in no other condition then the rest of the members of the Common-wealth, and so shall have an equal benefit of those good Laws and Provisions of publick safety which they have been instrumental in for publick good. It will not be safe in new Elections to chuse any that have served in a Representative again untill five yeers be expired or more.

4. In your choice have regard to this rule, to chuse men fearing God, and hating covetousness; for undeniably covetousness is the in-let to all manner of corruption, oppression, in-justice and Tyranny: Covetousness in a person of great trust, is evil in these two respects: either first, he is covetous from a base worldly mind, and therefore unfit for Government; or secondly, being desirous of greatness, is covetous to obtain wherewith to support his greatness, or defend him in his greatness; and therefore in a Common-wealth dangerous.

5. The manner of the choice of Members representative in a Parliament, should be so, as to prevent making of parties; for the party, or number of men that prevaileth in their Election of any one, obligeth him that is elected; and on the contrary, those that oppose that Election, him that is elected will conceive himself disobliged to them: therefore to prevent those inconveniencies. A more equality of choice will be safe (as when for Knights of the Shire, and Burgesses, there are to be two pitch’d upon by the consent of the County or Burrough) that the County or Burrough should chuse ten wise and honest men, and out of them ten, elect two by lot; by this means, making of parties will be prevented, also many will be prompt to improve their parts, so as they may be fit for so great a trust; likewise it will oblige more to the owning of that Government, wherein they see a possibility of having share of.

6. That the persons chusing, as well as those chosen or elected, should not be persons disaffected to the publick Interest.

7. That no one member of the Commonwealth have too much power committed into his hands, lest he make himself Lord of the common Liberty, or at least become thereby too powerful to be dealt with; to call such persons to an account may prove dangerous, for they to secure themselves, usually make use of their power in defending themselves, as Cæsar when he made himself Lord of the Empire. Alcibiades (being told Pericles was making up his accounts to the Commonwealth) said, That he rather should study that he might not give the Commonwealth an account, the which Pericles had done, had not the Commonwealth of Athens watched him the better.

8. That the Lawes of the Commonwealth should be explained and abbreviated, fit for the understanding of every one of capacity. Vespasian when he received the power of the Empire, he, to oblige the people, caused the Lawes to be written in brass; for if people understand their Liberty and Lawes, they are not so subject to be oppressed; and therefore ’tis the policy of him that would invade the liberty of a people, to keep them ignorant.

9. Those in power should be sparing of the publick Treasury, for oft times they dispose of it in favour to oblige many, whereby to strengthen their interest; which is dangerous; for that which is given by a Commonwealth, or promised, it must be real, for they have not that advantage, to bestow empty titles of honour, as Princes have (when their coffers are empty) to satisfie the ambitious or covetous.

10. That if a Commonwealth be necessitated to keep arms to justifie their interest, it will be safe that Discipline be strictly observed. otherwise they will become inconsiderable, and therefore in the Summer, their Forces should rather be encamped in the field: by this means Discipline would be preserved, Factions prevented, they would not be fastned to those relations, they would be more entire in bodies, consequently more ready to answer the necessities of the publick, in case of invasion or insurrection. It was observable, the Romans were more strict of Discipline in peace then in time of War.

11. That no priviledges be taken away from any Corporations or Societies (provided that every member of these Corporations or Societies have an equal benefit in those priviledges) but rather new granted: by this means Philip the wise made sure his estate: The Emperor Otho did the like. Lawes, Priviledges and Customes, and the like, have been the only Pales and Defences against Tyranny and Absoluteness; they have been as meers between common right and absoluteness; and those that attempt the taking away of these Defences, may be justly suspected of making preparation to absoluteness.

12. That no member of the Commonwealth ought to have guards for his person. Numa Pomphilia being chosen King, he told his Citizens of Rome (upon the discharging of the 300 men at armes) that forasmuch as he was intrusted in that Government by them, it was as reasonable for him to trust them with his person. So Timolian being by the Commonwealth of Corinth sent to aid Syracuse, being Victor, and having obtained the Castle of Dionysius, caused it to be demolished, and rather chose to oblige the Syracusians by Justice and Liberty, then to fasten obedience to them by arms.

13. That it may be made Criminal for any person in publick trust to receive any Bribes, Fees, or Gifts, that shall have Causes or Petitions depending before them; for by this means creepeth in all manner of corruption, injustice, partiality; by which means also the judgment is over-ruled and corrupted. It was to prevent the like inconveniencies in administration of publick Justice, That that Statute was enacted. Ann. 18. of Edw. 3. You shall not suffer your self, or any other for you, to take gift of Gold or Silver, or any other thing, that may turn to your profit.

14. It will be of great advantage to appoint twelve Counsellors of State, that should be qualified with abilities and judgment in Moral, Civil, and Common Law, as also the Law of Nations, and Military policy, the interest of forreign Princes and States, that at all times the Supreme Authority may demand their advice in cases of difficulty: but it is not fit they should be imployed in any thing but in advice; it is not fit nor safe, they should be qualified with the least power, not so much as to summon any person before them, nor decide or put in execution any matter Political or Judicial; it is fit they should continue in this trust, that they may be the better acquainted with matters of State, and constitutions of Government.

15. That Judges doing Justice in the name of the people, should be honoured with robes of Honour, which upon the arraying of them, it should de done in the name of the people: and that they continue no longer wearing those Robes, then sitting in the Judgment Seat doing Justice: also that Judges should be elected once a year out of the Learned of the Law.

16. That the better to prevent confusion, that the Authority of the Commonwealth may be preserved in a lively and eminent manner: to that end all Courts of Justice should depend one upon another, and all should be governed by the self same Law: So in all matters of State, all particular Councels should depend upon one Superior. As all Cities and Corporations, though by the joint consent of that Society, may ordain or enact any thing for the good of that Society, yet it should not be Law, until it be confirmed by the approbation of the Superior Authority, unless it be in some special cases, wherein they have a clear right by equity in Law to do or cause to be put in execution, such things as are for the good of that Coporation or Society, so that the execution do not extend to any others then the members of the same body. Care ought to be had to unite all bodies in a Commonwealth, so as to depend one upon another, for the good of the whole; by this means they become powerful, and as a drop of water being united to the Ocean, becometh part of that infinite body. Tacitus telleth us that the English did consult and make War against Cæsar apart, by Cities, or Counties, and therefore were overcome apart: a union of bodies, so as to depend one upon another, and jointly to support an Authoritie over the generality, there is no strength like unto this: onely have care that that Authority have sufficient checks upon them, that they may be tied up to rules to act for the general good, and not be swayed to interest.

17. Every one is to understand he is equally interessed with any member in respect of the common Libertie, and that there is no difference but in point of Trust: and therefore to clear this point, ’tis fit to consider what the nature of Law and Government is in general. Plato tels us, that Law and Government is to preserve the undigested and huge lump of a Multitude, and to bring all discord into proportion, so as to become an harmony. Aristotle saith, that all rectitude hath a being, and floweth from the fountain of being; whereas obliquitie and irregularities are meer privations and non-entities. Plato also saith, that every thing that is profitable hath a being, but no fruit can be gathered from privation: There is no sweetnesse in obliquitie; and therefore Government and Law is an wholesome mixture of that that is just and profitable to all. Such Lawes the Ancients imagined were chained in a golden chain to the Chair of Jupiter: and sure it is, that equall and impartiall Government doth derive from God himself, when it doth continue and constitute Lawes and Constitutions agreeable to the welfare and happinesse of those that are to be conformable to them, and that the consent of the whole Bodie be obtained. Aquinas saith, that Law and Government is a rationall Ordinance for the advancing of the Publick good: That is Law and Government that the necessity of the Publick standeth in need of, either to preserve it, or to make it happy. All Law and Government originally ariseth from the Law of Nature, to preserve all in being and propertie. The life and power is most eminently seen in rational being, as Chrysostome hath very rehtorically enlarged himself in the 12 & 13 Oration of his, thus; That all rationall beings have a radicall and fundamentall knowledg planted in them, budding and blossoming in first Principles bringing forth fruit, spreading it self to fair and goodly branches of Morality, under the shadow of which mankinde may sit with much complacency and delight: Therefore for the governing of so glorious beings, ’tis fit that Government should be an abstract from the consent, and for the good of the generality of those that a Law or Government is to regulute or binde. But as it hath been formerly said, such as are of greatest power, (though not of right) have laid the greatest claim to Government, and imposing Laws. Much like was that Sophisme affirmed by that Sophister disputing with Socrates, when he affirmed that Law was an Antipathy to Nature, and that the most eminent justice of Nature was to rule according to Power: But Socrates (after he had stung the same Callicles with a few quick interrogations) affirms. That there was no such harmony as between Law and Nature, that there is nothing preserveth Nature more then Law; but it must be as Aristotle affirmeth, when it is attended with Reason and Equitie. Though Rome had no Politicall Laws to check the tyrannicall pride of Tarquin, yet they had a virgin-Law of Nature which beamed out of an eternall Law, which was of strength and force to revenge a modest Lucretia, and expel so licentious a Prince from his Dominions. Likewise a late contemptible Marcionella by putting the Neopolitans in minde of their Laws granted by Charles the Fifth, did shake the very interest of the King of Spain in Naples, and nothing could appease them, but by assuring them that they might be governed by such Lawes as should be a preservation to them and their posterity. This is manifested in every Being, they use to fly from such things as are destructive to their own Species, and incline to all neighbourly and friendly beings that comply for preservation. All preservative Government and Law floweth from the law of Nature, but it is to the end Morall. Now since it appeareth, that there is an undeniable right in all rationall Being, and that they stand constituted with this right from the Original, which is the law of Nature, it being the fountain from whence all other Laws flow: and if natural, then equall; so that hence may be concluded, that no person or persons hath right to Government, or power in giving Lawes, but when they stand constituted by vertue of an immediate election, or derivatively from such persons as are to stand bound up by such Governors, or Government, unto which they are to be conformable; and it is as clear, that there is no way to preserve a peoples Rights and Liberties, from such as would make themselves Lords thereof, as often or annual elections; for if the people keep the right of often elections in their hands, it will make such as affect Government desire to be alwayes in the peoples favour; to that end, they will endeavour to oblige the people by acts of Honour and Justice; the people here must take heed they lend not such persons too much of their favour: to prevent this kind of evil, the Athenians banished such as had obtained, or did endeavour to grow too great in the peoples favor, they looking upon them as dangerous persons.

18. One of the principallest reasons of Romes declining in its glory, was when that persons in greatest trust insinuating into the peoples favour, by that means enlarged their power, and consequently became unquestionable. You may discover them treading these steps: 1. They insinuate into favour by pretending to be publickly affected: 2. They hedge in advantages to enlarge their power. 3. They find some necessary undertaking or other; thereby to possess the publick with an opinion of a necessity of imploying of them, by this means daily obtaining new advantages. But the safest way for a people in this case, is not to heap too much favor or Honour upon any one member of the Commonwealth, but keep such a mean as may not turn to the detriment of the publick, and alwayes provide means to curb their overgrown Members, lest a subversion of their Liberties ensue.

19. That the Publick ought to be preferred before the private: the contrary have been the overthrow of the liberty of many flourishing Commonwealths; for whilst men have been bundling up of private advantages, rather then they will run the hazard of losing of a few inferior and base contentments, (which may be called quiet, and not liberty) in contending, or at least, they seeing that such with whom they must contend are more powerful, they dispair; never considering, that it is more honourable to rescue their Liberty from the powerful: Such a slavish spirit in men to suffer themselves to be trampled upon by their fellow Members, gives encouragement to many to attempt the making themselves absolute: therefore a people that will keep their Liberty from being infringed, must not fear to oppose the most powerful: ’Tis not to be understood an opposition by arms, but a legal opposition; but if all lawful means fail, arms may be made use of.

20. That neither Princes nor Parliaments are, or ought to be absolute in their power; neither the one nor the other, ought to act any thing that should be inconsistent with, or prejudicial to the common good of all men. That the people of England had an undeniable right to contend against absoluteness in case of injustice or detriment, appeareth by the second of Henry the IV. Ch. 22. wherein ’twas enacted. That no person should be grieved for suing to break or alter any thing, although in Parliament enacted: So that it doth not only appear to be the right of every Member of the Commonwealth, but also their duty, to oppose all absoluteness or illegal power that shal be assumed by any that shal get the start of them in Authority or Greatness. But on the contrary, those that shall conspire to break, or alter the position of Government, are no other then Traitors to the common interest.

21. That all persons upon the resigning his or their Office, be required to give a publick account; for in private accounts there may be connivance.

22. When Magistrates do not answer the end reposed in them, providing for publick peace and Justice: a people in this case may constitute a Power to question them for their actings: provided also, that they still have regard to keep life and strengthen their Authority in such persons as shall act to that end that their trust was reposed in them for.

23. That a people stand not, by the Law of God, or the Law of Nature, bound to obey a Magistracy in any thing that shall be destructive to the general good, or that shall be unjust to a particular; but it is the duty of every one, so prejudiced, to oppose it and declare against it, in testimony that a people do not stand bound to obey or submit to any thing that shall be destructive to the general, or unjust prejudice to a particular; as may appear, Anno 2. Edw. 3. Ch. 8. expresly in these words: That it shall not be commanded by the Great Seal or little Seal, to disturb or delay common right; although such commands do come, the Justices shal not therefore cease to do right in any point. Likewise, Ann. 20. Edw. 3. Ch. 1. ’Tis commanded, That all Justices shall do right to all people, not having regard to either rich or poor, without being let or hindred by any commandment which may come to them from Us, or from any other, or by any other cause: and if any such do come, either Letter or Writs, the Justices shal proceed according to Law and Right notwithstanding, as is the usage of the Realm. So that it is clear, that none stand bound to submit to a Magistracy or Authority, but wherin the good of the Publick is concerned: so also it may be from hence concluded, that subordinate Officers should rather endeavour the knowing their duty in relation to the publick good, then to conform themselves to the will of their Superiours: for him that obeyeth, should be able to judg whether that which is commanded be in the power of him that commandeth, else he that obeyeth may execute (in stead of the Law of the Common-wealth) the absolute will of his Superior, which error reduceth him to slavery:

24. The judgments of the people are not so subject to be corrupted as great persons, for the people have no other end in what they desire, but common equity; whereas otherwise great persons are swayed by several ends and interests; and therefore often elections are more safe: for by this means the people keep the power in their own hands. Election is to be understood a qualifying of those which are to be elected with Authority to execute Law, that is extracted by mutual consent of the generality for their good.

25. That all actions in favour of parties be laid aside: this will be a means to keep all at an even poyze, so that one side should not out-weigh in power, riches or honour: this is, for the preservation of the State of Venice, duly observed at this day, as may appear by the custome of the Senators to put off in Saint Marks Church, all affection, malice and quarrels, so that when they deliver their opinions in Senate, it is clearly for the good of the publick, without having regard of private interest. There is an inscription in Marble, in letters of Gold, at the entring in of the Councel Chamber of Reinsburgh, Whosoever thou be, Councellour or other, that in regard of thy Office goest into the Councel Chamber, out off, and leave before this door, all private affections, anger, violence, hatred, friendship or flattery; submit thy person and care to the Commonwealth; for as thou shalt do right or wrong in this, so expect from God who will judge thee in this thing. The Senate of Rome, when Rome flourished, were enjoined by an Oath, the substance thus: You shall swear by Jupiter Olympian, and Counseller, and by Vestal the Consultress, and by Jupiter the Marrier, and June the Married, and Minerva the Provident, and Victor, and Venus, and Amity, and Concord, and Right, and Equity, and good Fortune, and all other Gods and Goddesses, that I resolve to speak my opinion according to the Lawes and Ordinances approved by the City, according to the Decrees and Edicts of the Romans, by the which our Commonwealth is govern’d, having respect to the profit of my Country with all my power; I shal not suffer that my judgment or counsel shall be subject to favour, hatred, gifts or presents; I shall not frame my Sentence to the will of any particular, nor join my self to any man or party, but only to the common benefit, that I may to the utmost of my power increase the Commonwealth. So that it appeareth, that the Commonwealth of Rome had a necessity to provide against partiallity, and promoting of private interest: you shall not find one amongst the Romans, during its glorious freedom (until corruptions gained footing in the Commonwealth) that was ever preferred for being Cozen, Uncle, Father, Son, or otherwise related, but their tryals were their qualifications and abilities to undertake in peace or war for the good of the publick. In the forementioned Oath, you may mind one clause, which is, That they shall deliver their opinions according to the Laws and Ordinances approved by the City or Commonwealth; so that people that are free from being Lorded over by the claim of any one person as Monarch, are not bound to observe or obey any Laws but such as they shall consent to by a general approbation. Caius first directed his voice in his Orations to the people, and not minded the Senate; (whereas other Orators that deceived the people, and flattered the Senate, directed their voice to the Senate) He restored the Authority of the people, and minded them that Government was provided for their good, to deliver them from serving the more powerful: and therefore it should behove them to watch to their Liberty, that they should not look upon any circumstances in Religion to be qualifications for publick Trusts.

26. When a Government is contracted into the hands of one or more, that they come to pretend any thing of right to Government, that Commonwealth is seldome free from War, both Civil and Forraign: so that that bloud and treasure that should be spent in enlarging the Dominions of the Commonwealth, are spent in quarrels of such persons as lay claim to the Government: as an instance, the Warr between the House of Lancaster and the House of York, wherein so much of our English bloud was spilt. That indeed should be an inducement to caution England never to let any of their members grow too great, nor continue too long in great Trusts: Many claim a right by no other Title then long Continuance or Possession. What miserable Wars, Murders, Burnings, Depopulations, Cruelties of all kindes were committed in the times of Nero, Galba, Otho and Vitellius? which were personal quarrels of those, to grasp at the Empire, and to hold it when possessed. Likewise the Civil War between Cæsar and Pompey was the cause of he Roman Commonwealths losing of footing, by suffering two of their Members to grow to that greatnesse, to be able to wage such considerable Wars one against the other, by which means the Victor became able to give a Law to the Commonwealth, and could no longer relish receiving a Law from them, after he had tasted what large Command, and long continuance therein was &c.

27. If the Common-wealth hath many Warrs, they should not put the Conduct on one Members shoulders; but rather chuse severall Members for several Undertakings; so that by this means there wil be several or many of equal credit, and therefore lesse dangerous.

28. That those that have the charge of the conduct of Armies, may not have the power of disposing the Treasurie, not the levying thereof; but the Civil Power to act in that particular, that the Military power may know they are Servants, and not Masters.

29. Care to increase Manufacturie ought to be had, for that enricheth and civillizeth the people. Likewise care in Commerce, to poize the exchange with Forreigners, left they eat you out of the Principal.

30. Not onely to be careful to provide good Laws, but also to provide a due execution, and that penalties may be inflicted against those Magistrates that are remiss in the due executions of those Laws and Constitutions as are provided for the conservation and good of the Publick.

31. That private motions or making of friends to obtain any thing whatsoever, may not be allowed of under great penalties.

32. That all persons in trust should be limited to act according to the Laws, Customs and Usages of the Commonwealth, and not otherwise then to the preserving of just and equall Freedom. It is not to be understood of just and equal Freedom or common libertie, to be any other thing then to distinguish and preserve Proprietie.

FINIS.