[Richard Overton], A Defiance against all Arbitrary Usurpations (9 September 1646).

Note: This is part of the Leveller Collection of Tracts and Pamphlets.

Bibliographical Information

ID Number

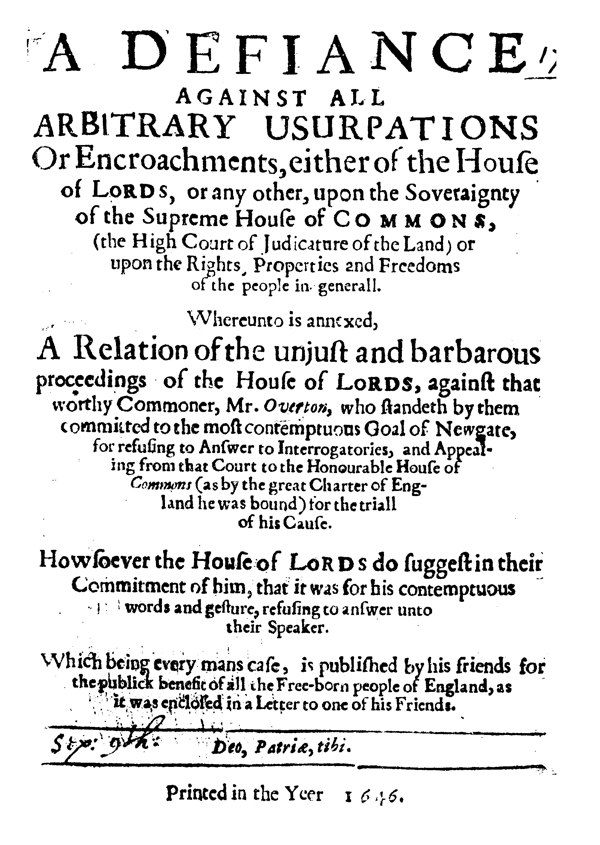

T.75 [1646.09.09] [Richard Overton], A Defiance against all Arbitrary Usurpations Or Encroachments (9 September 1646).

Full title

[Richard Overton], A Defiance against all Arbitrary Usurpations Or Encroachments, either of the House of Lords, or any other, upon the Soveraignty of the Supreme House of Commons, (the High Court of Judicature of the Land) or upon the Rights, Properties and Freedoms of the people in generall. Whereunto is annexed, A Relation of the unjust and barbarous proceedings of the House of Lords, against that worthy Commoner, Mr. Overton, who standeth by them committed to the most contemptuous Goal of Newgate, for refusing to Answer to Interrogatories, and Appealing from that Court to the Honourable House of Commons (as by the great Charter of England he was bound) for the triall of his cause. Howsoever the House of Lords do suggest in their Commitment of him, that it was for his contemptuous words and gesture, refusing to answer unto their Speaker. Which being every mans case, is published by his friends for the publick benefit of all the Free-born people of England, as it was enclosed in a Letter to one of his friends.

Deo, Partiae, tibi.

Printed in the yeer 1646.

Estimated date of publication

9 September 1646.

Thomason Tracts Catalog information

TT1, p. 462; E. 353. (17.)

Editor’s Introduction

(Placeholder: Text will be added later.)

Text of Pamphlet

The great and continued experience of your endeared affections towards me, of your uprightnesse, valour, and fidelity through manifold afflictions both ancient and present, for the publick weal, and safety of all men in generall, and of the honest and godley in speciall, hath so emboldned me with you, as not to count it presumption to single you out from the rest of my friends in this time of my bonds to unbosome my imprisoned thoughts unto you, as knowing you to be a man much sensible and grieved at the oppressions, miseries, and calamities of the people; which if not narrowly and wisely observed, and discovered by the more conscienscious and knowing, will prove for ever incorrigible, and helplesse. But for me to undertake the cure of this Nationall Disease, were justly to incur the censure of ignorant presumption, by reason of my own known insufficiency; yet into the Treasure of your private consideration I shall be so bold as to cast in my mite, not doubting of your friendly construction, presenting you for your better information and satisfaction, with a narrative of the illegall and barbarous proceedings of the House of Lords against me, concerning this their most unjust Commitment of my person to the Goal of Newgate, the which you may communicate to whom you shall have occasion.

But first be pleased with me to consider, that such and so long hath been the Arbitrary encroachments, usurpations, and invasions of the naturall Rights, properties, and freedoms of the people of this Nation, through the abused power, and machivilian policy of the Kings, Lords, and Clergy-men thereof, that the spirits of this people (naturally of themselves noble and free) are even vassalaged, and drawn into an inconsiderate dislike of their own primitive, naturall, and Nationall Rights, Freedoms, & Immunities, insomuch that they persecute, and condemne all such amongst them (as Traytors, Rebels, and Enemies to all Government) that are more conscious, and carefull of their own naturall properties, and shall but endeavour to pluck off the Clergy-scales of insinuation, flattery, and adulation, from their darkned eyes, endeavour to discover & break the Norman yoke of cruelty, oppression, and tyranny from off their necks, and set their heels at liberty from the Prerogative fetters of the House of Lords, (by opening the Cabinet of their machivilian policy, against the peoples Liberties, that those Usurpers might be discovered in their deceit, as their Masters were in their King-craft, and the peoples deluded understandings be undeceived) these instead of gratitude, shall be rewarded with hatred, and the malefactors portions for their faithfull endeavours, and good intentions.

Yea, such hath been the misterious mischievous subtilty from generation to generation of those cunning Usurpers, whereby they have driven on their wicked designes of tyranny and Arbitrary domination, under the fair, specious, and deceitfull pretences of Liberty and Freedom, that the poore deceived people are even (in a manner) bestiallized in their understandings, become so stupid, and grosly ignorant of themselves, and of their own naturall immunities, and strength too, wherewith God by nature hath inrich’d them, that they are even degenerated from being men, and (as it were) unman’d, not able to define themselves by birth or nature, more then what they have by wealth, stature, or shape, and as bruits they’l live and die for want of knowledge, being void of the use of Reason for want of capacitie to discerne, whereof, and how far God by nature hath made them free, if none have so much magnanimity as to ingage betwixt them and their deceivers, as not onely Religion, and Reason, but even Nature it self doth bind every man to do according to his power, whom God hath inabled, and honoured with any talent or measure of abilities to that end, whatever perill or danger shall ensue, though of liberty, estate, or life, Quia nemo sibi nascitur, Because no man is born for himself.

But the task will be no lesse difficult to effect, then perillous to attempt, for through this long continued flattery under those Prerogative Task-masters, the usurping Lords, they are now so besotted therewith, that they even esteeme sowre sweet, and sweet sowre; usurpation, and tyranny, better then naturall freedom and property; and so are become contented slaves to those insolent, Arbitrary, tyrannicall Usurpers; accounting it their honour to rob themselves, and their posterities, of their just Birth-rights and Freedoms, to make those domineering Insulters magnificent and mighty, and themselves and posterities miserable. So that he whosoever he is, or shall be their Informer, must not look to conquer all where he may at first seem to prevail, yet that may not excuse his endeavours, which are the discharge of his duty: feeling the blessing comes in the use of the means, and it is impossible that so great stupiditie should be either removed from this generation, or prevented in the next, except there be diligent, faithfull, continued, and powerfull endeavours used.

And how dangerous and perillous the cure is to the Physitian of this Disease, may easily be imagined, when Free-men by Nature are even so unnaturall, and inhumane to themselves and their own posterities, that they are so ready with hazard of their lives and estates to purchase power even for their Usurpers, to be trampled under foot like mire in the street: and if they be thus unnaturall and inhumane to themselves, much more to others whom they ignorantly and fondly not onely suppose to be, but persecute them as their enemies, when as indeed they are their best and most reall friends. And this disposition and temper I have observed to be common, especially where the dregs of Regality, Peerage, Episcopacy, or Presbytery remain, for there, there appeareth nothing but wrath, anger, and revenge against the opposers of usurpation, tyranny, and cruelty; if they be but guilded and furbish’d over with those formall titles of honour obtained through their great policie, craft, and deceit.

Thus the people being cast into this temper of ignorance and vassalage (the one by them esteemed, and fancied for wisdom, the other for freedom) they are even fitted for their Arbitrary designes, by and through whose strength and power, those Machavilians do act, and without which they could not move or ever prosecute or accomplish their politick designes of oppression and cruelty upon them: never could the Arbitrary domination of Kings, Lords, Bishops, or of our new upstart Presbyters (newly re-royalliz’d) have win to such an exorbitant height in this Nation, it would never have been thus puft up, thus exalted with their Arbitrary venome, to have burst asunder in wars, emulations, and divisions, had it not been for the sottish and fond ignorance wherewith they have thus bestially besotted the people of this Nation, for the spirit of emulation (striving who should be greatest) being cast in amongst those usurpers, the people are by those fore-mentioned means fitted on both sides, pro or con, for their purpose to fight, and destroy one an other for the advancement of these Arbitrary Lords and usurpers, if they do but tell them of Reformation in Religion, the Liberty and property of the people, when as indeed and in truth nothing lesse is intended.

Yet do those ignorant deceived souls run on, and, like horses, furiously rush into the battell whether right or wrong, though all (God knows) under a fond imagination of their own weal, the publick property, safety, liberty, and tranquillity, but how for the publick-weal, and safety, the removall of oppressions, and tyrannies, oppressors and tyrants old or new, either Royall, Lordly, or Clericall in this Nation, the late great miraculous conversion (of the King, the Lords, Presbyters, and others) shew clearly, whatever was, and is still, intended for the people, even meer oppression, tyranny, slavery, that’s their doom, except they look better about them, and stick closer to their own representative Body the Commons assembled in Parliament; yea, and they to them too, for love cannot stand on one side.

And the occurrences of these heavie times do clearly prognosticate, that except the people of this Nation with their hearts, hands, lives, and estates, stand close to their own House of Commons, yea, and they to them, and do justice, and relieve prisoners, and all that are oppressed, especially by the Lords, with resolution and fidelity, in despight of the malice, power, policy, and force of Kings, Lords, and Presbyters, they themselves will be reduced to their old bondage, slavery, and oppression, if not to far worse; even more cruell, Lordly, and tyrannicall then ever before: yea, and this very House of Commons (the most supream Court of Judicature in the Land) will be swallowed up, consum’d, and confounded, and the severall Members thereof proceeded against as Traytors, and Rebels to the King his Crown, and Dignity: yea and that cruell late Proclamation renewed, that a Parliament shall be no more mentioned, as we have both dolefull experience at the untimely breaking up of former Parliaments, and dreadfull prognosticks in this already, to wit, the Inditement of his victorious Excellency Sir Thomas Fairfax, with other gallant Patriots and Contestors for their Countrys Liberties and freedoms, at the Assizes of Chester, as also Mr. Crab, and severall others though of meaner rank and quality, yet men of approved honesty, valour and fidelity to the State; who have notwithstanding (or rather for their reality and fidelity, been Indited, arraigned, condemned, and fined 500 l. a piece, and imprisonment till it be paid, for nothing but for uttering their indignation and anguish of mind against the cruelties, blood-shed, and oppressions of the King nefariously perpetrated upon the people) in form or phrase of words which was unpleasing to their Caveleerships: these are but the beginnings of wo, which portend and threaten a generall and irrecoverable destruction, if the Scotch Miracle of the Kings Conversion take but its proper effect, as God forbid, for nothing is betwixt it and them, but a readvancement on the Royal Throne, and then farewell Parliaments, Laws, Priviledges, Freedoms, Liberties, and all.

Therefore, see Englishmen, that have true hearts, and love to the House of Commons, ye that desire the safety and preservation thereof, the peace, weal, rights, liberties and freedoms of this Nation, ye that would do as you would be done unto, that would have your neighbour injoy the fruit of his own labour, industry, and sweat of his brow, the freedom of his Conscience and estate, his own naturall right, and property, and have none to invade or intrench upon the same, more then you would have upon your own.

Ye in speciall be encouraged against all opposition and encroachment of Kings, Lords, or others upon the House of Commons their rights and properties derived from the people, and save them, or else ye will all speedily fall. Keep up their names, titles, honours, and priviledges above all usurpations whatsoever, either of Lords, or others. And acknowledge none other to be the Supreme Court of Judicature of this Land but the House of Commons, and in this gallant resolution live and die, and acquit your selves like men: for my part I’le tread upon the hottest coals of fire and vengeance that, that parcell of men, intitled, The House of Lords, can blow upon me for it.

And though I be in their Prerogative clutches, and by them unjustly cast into the prison of Newgate for standing for my own, and my Countrys rights and freedoms, I care not who lets them know that I acknowledge none other to be the supream Court of Judicature of this Land, but the House of Commons, the Knights and Burgesses assembled in Parliament by the voluntary choice, and free election of the people thereof; with whom, and in whose just defence I’le live and die, maugre the malice of the House of Lords. For I acknowledge that I was not born for my self alone, but for my neighbour as well as for my self; and I am resolv’d to discharge the trust which God hath repos’d in me for the good of others, with all diligence and fidelity, as I will answer it at Gods great Tribunall, though for my pains I forfeit the life and earthly being of this my little thimble full of mortality.

And these are further to let them know, that I bid defiance to their injustice, usurpation and tyranny, and scorn even the least connivance, glimpse, jot, or tittle of their favour: let them do as much against me by the Rule of Equity, Reason, and Justice for my Testimony and Protestation against them in this thing as possibly they can, and I shall be content and rest: for, Nihil quod est contra rationem est licitum; Nothing which is against reason is lawfull, it is a sure maxime in Law, for Reason is the life of the Law. But if they transgresse, and go beyond the bounds of rationality, justice, and equity, I shall to the utmost of my power make opposition and contestation to the last gaspe of vitall breath; and I will not beg their favour, nor lie at their feet for mercy; let me have justice, or let me perish. I’le not sell my birth-right for a mess of pottage, for Justice is my naturall right, my heirdome, my inheritance by lineall descent from the loins of Adam, and so to all the sons of men as their proper right without respect of persons. The crooked course of Favour, greatnesse, or the like, is not the proper channell of Justice; it is pure, and individuall, equally and alike proper unto all, descending and running in that pure line streaming and issuing out unto all, though grievously corrupted, vitiated, and adulterated from generation to generation.

Why therefore shall I crave my own, or beg my right? to turn supplicant in such a case is a disfranchising of my self, and an acknowledgement that the thing is not my own, but at another mans pleasure; so that I forsake and cast off my property, and am inslav’d to his arbitrary pleasure: if the other will, I may have possession, otherwise not. Which indignity to my own, or to my Countreys rights, their Lordships shall never enforce me; for it is no better then a branch of tyranny to force a man to turn supplicant for his own, and of self-robbery to submit thereto. Though this inslaved Nation be most deeply and miserably involved in that intolerable condition, so that indeed we cannot have our own naturall rights and immunities, but we must be either patient sufferers, or actuall Petitioners, as if our own were not our own of right, but of favour.

What is this other but an utter disfranchisement of the people, and a meer vassalage of this Nation, as if the Nation could have nothing by right, but all by favour, this cannot hold with the rule of Mine and thine, one to have all, and another nothing: one’s a gentleman, th’other a begger; so that the birth-rights, freedoms, and properties of this Nation are thereby made these great Mens Alms; and we must come with hat in hand, with good your worships, May it please your Honors my Lords, and with such like terms of vassalage and slavery for our own rights, as if we ought them Villein-Service, and held all the rights and properties we have, but by Tenure in Villonage, and so were their slaves for ever.

Indeed, if this Petitionary way be lawfull and expedient, onely in testimony of respect, loyalty and obedience unto that Soveraigne power which all of us the Commons have chosen out from among us, and set up for the mutuall good both of us and themselves (wherunto out of a good conscience we are bound in duty to submit in all things just, lawfull, honest and reasonable) and not out of any Arbitrary respect, homage, or reverence which is not due; as if the Commoners just liberties and freedoms were not their own of right, but of favour and grace. I shall freely and willingly walk in that petitionary way, and make presentation of my just suits, as I shall have occasion. And I hope the Honourable House of Commons (to whom that Power is convey’d, and in whom it onely and truly resideth) doth require it from their fellow Commoners (the free people of England) in no other respect, but in testimony of loyalty to them.

But those Lords do challenge the Supremacy to themselves, which I shall make appear by this ensuing Relation to you as one of my dearest friends, of their illegall practises, and unjust proceedings against me a Free Commoner of England.

Sir, it is not unknown to me how various and different the reports haue been about this businesse, especially concerning my words and gesture when I was brought before the House of Lords: But though divers will account it to be vain-glory, pride, ambition, folly, and what not, for me to make a narration of mine own speech and behaviour; yet of you, and the better sort, with whom I may be bold, it is presumed that even my own recapitulation or rehearsall thereof, will be taken in the best sense, especially now when necessity hath no Law, both my just cause lying (as it were) at the stake and my self being in prison, and therefore as if I were presently to suffer, what those unjust troublers of my peace, and infringers of my liberty would inflict, if their power were as large as their will, I will present you with a full relation of the very truth of all that hath yet past between them and me, both that you may be rightly informed thereof, and others also by your means; if it can no otherwise be conveniently divulged to the whole Commons of England for their information and satisfaction, as a businesse no lesse belonging unto them, alwayes to weigh and consider, then it is troublesome at this time for me to undergo.

Upon Tuesday, August 11, 1646 one Robert Eeles, a Journeyman Printer, commonly known by the name of Robin the Divell, and one Abraham Eveling (dweller at the Green Dragon in the Strand) entred into my house betwixt 5. and 6. a clock in the morning, and this Eeles at his first entrance into my house, said with a loud menacing voice, W—w—w— we will have him in his bed; then forthwith the said Eeles ran up the stairs into my Bed-chamber with his drawn sword brandashed in his hand, and after him hurries the said Eveling with a Pistoll in his hand ready cock’d, to the great affrightment, terrour and amazement of my wife lying sick in Child-bed; and as soon as they had made this forceable entrie into my Chamber in this Hostile manner, the said Eeles with bended brows, and irefull look with his naked sword against me, said to me lying in my bed, Tut, tut, tut, rise up and put on your clothes: whereupon I arose out of my bed, (espying my wife as I came near her ready to swound at that sudden affright) and taking my garments to put on, this Eeles pick’d my pockets, taking what he pleased out of them, for which, and for the rest of his barbarous, tyrannicall, and illegall dealings with me he may expect Justice; and then he ransaked a Trunk, and taking out a pair of Britches felloniously pick’d the pockets thereof. In the mean time I slipt on my clothes, and went down the stairs, and looking out at my doore, I espied certain Musketeers at my Gate; then those Armed men above cried, Stop him, stop him: whereat I withdrew my self. And behind my house were other Musketeers, who presently ran with violence towards me, threatning to knock me down with their Muskets, and to shoot me; one saying, if I had been so near him as I was others, he would have run me through with his sword: and from this Hostile pursuit I fled, but was surprised by them; and I was no sooner captivated, but these men also nimbly slipt their fingers into my pockets.

Thus in this hostile manner my person being surprised, these armed men drag’d me away violently; And as they went, I demanded of them, What they were that thus by violence and force of Arms did assault me? and what was their intent? and whether they had any Authority for what they did? Not one of them all this while in the least mentioning or producing any Authority or Warrant for what they did, but all of them (when I was in my own yard) encompassing me round in that armed posture, did vilifie and abuse me with divers scurrulous and scandalous reproaches; divers of them griping me in their clutches, and threatening to lay me neck and heels together, which was a most insufferable affront, and invasion upon the rights, properties, and immunities of the free-born Commoners of England.

For by the great Charter of the Laws, freedoms, and properties of the people thereof in such cases no mans property, person, house, &c. may be assaulted, entred, much lesse by force of Arms in warlike posture invaded, or seized upon, without Warrant first shewed or declared; and no violence, especially by force of Arms, may be offered or committed against any of the free Dennisons thereof, but in cases of violence, opposition, and contempt of Authority truly Magisteriall: for the Law brings none under penalty, deprives no man of his liberty, person, or estate, looks upon none as its captive, before its Authority first shewed or declared to the party intended, and that by proper denomination or name, or else no man could be safe at home or abroad, or have any certainty of his own liberty or property, either in person, goods, or estate; but daily subject to the robberies and murthers of rebellious and wicked men.

For as upon this ground the Kings appearing in hostility, and leavying of war against the Parliament and people is adjudged unnatural, barbarous and illegall, being, he never yet hath produced any Legall Authority or true Magisteriall Warrant for what he did; so that during his time of the none appearance or inspection thereof, the Parliament and people have stood in their own defence, and the same both in point of Law and Conscience is truly adjudged both reasonable, equall and just. Therefore by the same rule, that the whole State may oppose the King their Generall Man in this his hostility for their necessary defence and their Action justifyable by Law, as equall, reasonable and just and the King condemned as illegall, unnaturall and barbarous. Even so upon the same ground, and by the same rule, that opposition which is made by a particular man in his own necessary defence, against the assault or sudden hostility of certain other particular men upon his person, or house, without any Warrant or Magisteriall Authority for that their hostilitie, is by the Law of the Land lawfull, justifyable and equall; and the others condemned, as illegall, unjust, unnaturall and barbarous. So that my case (for that time being) is of the same nature with that of the Parliament against the King. If I must be condemned for denying to subject my self to that their hostile assault, and proffering to stand in the just and necessary defence of my self, my wife and family, till these men had produced a Magisteriall Warrant for that their hostility; the so must the Parlaments practises against the King.

Thus it will necessarily follow, that as my half houres resistance of those men is as justifiable as the Parliaments four yeers resistance of the King, and of these who have leavied these wars against the Parliament, and must be proceeded against as Delinquents, traytors, and Enemies to the State: then those which made this violent hostile invasion upon me deserve little lesse. For though that be not of the same degree, yet is it of the same kind and nature. So till their production and discovery of a Magisteriall Warrant, these Armed men thus assaulting my person, and invading my house by force of Arms, appeared not to me for that time being in any magisteriall capacity, neither indeed could they be so accepted, by reason they made no appearance of distinction of themselves from common men; so that I could not in the least take them for Magisteriall persons (no Magisteriall Authority appearing) but for Murtherers, Theeves, and Robbers. For if assaulting of mens persons, invading and entring their houses, and taking what of their goods such men please, and that all by force of Arms, be simply a Magisteriall Act, then All theeves and murtherers are justified thereby; for their violence is without any Magisteriall Authority appearing: but by the Law it is therefore adjudged theft, murther, &c.

Wherefore I hope the free Commoners of England, as they tender themselves and their posterities, their severall weals, safeties, and well-being, will now seek for the suppression and future prevention of such outrages, and incursions upon their rights, freedoms and liberties, though such insolent usurpations and tyrannies should be driven on by the men of the highest Arbitrary titles in the Land; against whose injustice, tyrannies, usurpations, and encroachments upon the Commoners of England their rights and properties, I have engagd my life for the delivery and freedom thereof: for better is it that one or some few should perish, then a multitude.

But to proceed with our former Relation. After I was in this hostile manner surprised, some of them did vilifie me for flying from them, to whom I replyed:

Gentlemen, I did not flie from Authority, but from violence, hostile invasion, and pursuit, for my house being in this hostile manner invaded, and looking out of my doores, and espying Musketeers at my gate, I was struck into a sudden fear of my life: and hearing of no Magisteriall Authority, nor seeing the least appearance thereof from them, but of hostile invasion and assault, menacing nothing but death in my appearance: I therefore (as by nature I was bound) attempted to make an escape for the present preservation of my life. And this I repeated divers times over to them, with some circumstantiall variations in phrase, but not in matter. Then in most promiscuous manner they uttered many reproachfull and menacing words and speeches which I cannot well remember, by reason of the great confusion thereof, and mine own distemper with my wife and childrens lamentable case, and therefore I shall omit them, untill I can better recapitulate my thoughts. Wherupon I bade them take notice how they had invaded and assaulted my person with Muskets, sword and Pistols: and how with drawn Sword and Pistol ready cock’d, by force of Arms had entred my house, and therefore if they had no Magisteriall Warrant to shew for their Authority, I would not submit unto them, but would stand in the legall defence of my self, my own right and property, which thus by drawn sword and force of Arms they had assaulted and invaded: Adding this as a Reason; That my House is my Castle, my right and property, over which none hath power but my self, excepting lawfull Authority.

And espying my neighbours gazing upon me, I desired them to take notice how those men had assaulted my person in this hostile manner, contrary to the rights, freedoms and immunities of the free-born people of this Nation; and how they had beset and surrounded my house with divers men armed in warlike manner. And further, I desired them to take notice, how those armed men had entred and invaded my house in this hostile manner (which is my Castle, my own present right and freedom) by force of Arms, even with drawn swords, and pistols ready cock’d, to surprise or kill me in my bed, and all without any Magisteriall Authority, none of them producing, mentioning, or so much as confessing hitherto any Magisteriall Warrant for such kinde of practises and proceedings.

Then after some confusion and reiteration of their words, and austere gesture towards me, I applyed my self unto them in this wise.

Gentlemen, if you have any legall Authority, or Magisteriall Warrant for what you do, then produce it, and I shall freely submit, otherwise I will not obey you: for so far as you have Authority, and no farther will I yeeld my self. At which time they began to tell me they had a Warrant: And the foresaid Eveling pluck’d a paper out of his pocket, and began to read; whereupon I desired, that I might see what was read, lest they should cheat me; but they grapl’d me so violently, that I could not: but by the sound of it I understood, that it was an Order from a Committee of Lords, to apprehend suspitious persons for Printing of seditious and scandalous books, and to bring them before the said Committee of Lords; Subscribed by the Earl of Essex, and the Lord Hunsden.

To which I answered; Gentlemen, this is no Warrant Magisteriall for the apprehension of me, for my name is not so much as mentioned therein to be a suspitious or seditious person, or to be apprehended at such an one. And therefore I not being taken notice of by the Law as a seditious or suspitious person, or by it nominated for such an one, I would not obey them: And therefore (said I) that was no Authority for me, and I would not obey it.

Then attempting to go into my house, they held me by force, and would not suffer me, but assayed forthwith to drag me away, threatening to lay me neck and heels together: Whereat I answered; Gentlemen, you may drag me away by violence, but I will not voluntarily submit; which if you do, my going with you is not my own Act, but yours; not the Act of my submission, but of your violence; for I for my part am resolved by my own proper Act to stand for my own Rights, that is, as much as in me lies to defend my person, house, property, and freedom against all hostile and violent opposition that is not by Magisteriall Authority, and so consequently the rights, properties, and freedoms of this Nation in generall.

Then with a File of Musketeers they drag’d me away, and by force of Arms brought me to the Bull-Tavern at St. Margarets Hill in Southwarke, where they kept me prisoner. And when I was there, I demanded so much my liberty as that I might send for a friend; But the said Eveling denyed me of that benefit, which is my due by birth. Then I demanded of him, If he had any Authority to inhibite me of that liberty? And he told me he had no Order to permit it: To whom I replyed, Sir, you can not authoritatively infringe me of any of my Liberty without a Magisteriall Inhibition, and no more may you deprive me of any thing more then you have Authority or Warrant to do. Yet notwithstanding he still denied me of that my just liberty: whereupon I knock’d for the Drawer, and told him that I would try what I could do, for I would not voluntarily suffer them to take from me so much as any breadth of my liberty, that I would not onely stand for my own rights, the common rights and immunities of this Nation; but even for the naturall Rights of themselves in particular, and of their posterities, though themselves had dealt so unfriendly and barbarously with me as mortall enemies, thus not onely pleading, but working, yea and fighting for their own bondage.

Then being urged by some of their frivolous speeches, that my carriage would make worse both for me, and others: I affirmed on the contrary, my carriage was such that it would go well with me so long as I stood to the Law, and such like discourse; and thus I addressed my self unto them.

Gentlemen, I am resolved by the grace of God, that whatsoever either you, or any man, or men shall do against me, I will not let go (by my own or proper consent) the [Editor: illegible word], jot, title, or bare-breadth of the just Rights, freedoms, or liberties either of my self, or of any other individuall, or of this Nation in generall: stand or fall, live or die, come what come will, on this I am resolved, hoping so to deport my self according to the Rule of Reason, equity and justice, that if I suffer, it shall not be for evill, but for well-doing, and righteousnesse sake, for which is promised a blessing. And adding this further, that in case, through the tyranny and injustice of some, I should suffer, that notwithstanding that I did not doubt, but in my sufferings it should appear unto them, that it was a friend of theirs, and of this Common-wealth, which by them was thus violently and illegally assaulted, and kept by force of Arms.

Now during a great part of this time, the said Eeles with some Musketeers went out of the Tavern, and staying a great while, at length they returned, and as soon as they came in, they would have needs perswaded me that they had taken a Printing Presse, and Printing Materials of mine. But I answered, their bare affirmation was no sufficient proof, and it was necessarie first to prove before they did affirm it: Then this Eeles commanded me to go along with them; But I told him I was resolved not to stir a foot with them, except it were by violence; and if by violence, then it were not mine (as I said before) but their own act. Then the said Eeles took me by the hand, and drew me along out of the house, and so led me through the streets in that contemptuous and disgracefull manner amongst my neighbours, being strongly guarded with armed men, as if I had been a Traytor, or a Fellon, so that the streets were fild with people, of whom I was abused in a most scandalous, scurrulous manner, by base and evill language.

Whereas for my own reputation, I was forced to declare unto the people as I went along the streets, that I was not apprehended by any Magisteriall Authority or Warrant, but by violence, and force of Arms. Then the said Eeles call’d me Tub-preacher, and told me that I preached in the streets; and did this on purpose to raise a mutiny: and if I would not be ruled, he would tye me neck and heels together. Then I bade him do his worst, for I defyed his cruelty, and scorn’d his mercy. Then coming to St Mary Overies stairs, they forc’d me into a Boat, and brought me to Westminster-stairs; and when we were landed, this Eeles took me by the hand, and the said Eveling with his Pistoll ready cock’d on the other side, with the Musketeers for their guard, I was by them contemptuously led through Westminster Hall, and so unto the Lords House. And coming to a private Chamber, where (as it seems) sate a Committee of Lords, as they so styled themselves, whereof the Earl of Essex, and Lord Hunsden, and others were.

Then the Earl of Essex demanded of me whether I were a Printer, or no? To whom I answered, Sir, I will not Answer to any Questions or Interrogatories whatsoever, which may infringe either my own liberty, or the properties, rights and freedoms of this Nation. Whereat this Eeles standing by, said in a most scornfull deriding manner, that I was one of Lilburns Bastards. To whom I replyed, that I was free-born; and demanded of him wherefore he call’d me Bastard? But the Earl of Essex commanded his silence; and askt me the second time if I were a Printer? To whom I answered again, that I was resolved to stand to the rights, and properties of the people of this Nation, and therefore I would not Answer to Interrogatories. Then they speaking nothing to me, I desired of them to know where, or before whom I was. Then the Lord Hunsden said thus, You are before a Committee of Lords which is the most Supream Court of Judicature in the Land. Then I answered, What! is a Committee of Lords the most Supream Court of Judicature in the Land? Then the Lord Hunsden said, You’l make what you list of it; I say not so. To whom I retorted thus: You say that I am before a Committee of Lords, which (Committee of Lords) is the most Supream Court of Judicature in the Land. Then the Lord Hunsden answered again, that he did not say that, that Committee of Lords was the most Supreme Court of Judicature in the Land; but that the House of Lords was the most Supreme Court of Judicature in the Land.

Here by the way may be observed, the most insufferable encroachment, and usurpation of those Lords over the priviledge, supremacy, and soveraignty of the House of Commons. For be it granted that the Lord Hunsden did not intend in his minde, that the Committee of Lords was the highest Court of Judicature of the Land; yet he both said it, and meant it of the House of Lords. Now then whether the House of Lords be the Supreme Court of Judicature in the Land, may be easily known, if it be but considered by whom they were chosen to sit in Parliament: and if not by the Cities, Counties and Burroughs of the Land, then are these Lords neither Lords, nor Representers of the people. And if they be neither Lords, or Representers, then at most they cannot be Representers of so much as their own Tenants, but rather Presenters of themselves in the Land, and therefore must of necessitie be subordinate to those who represent the whole Nation; for by the rule of right reason, the lesser must needs be subject to the GREATER.

And therefore it was wisely and rationally provided by our predecessors, in the Great Charter of England, that the represented should be tried by the Representers, the Commons by the Commons in criminall cases. For indeed the peoples soveraignty and power is onely in that their great and Supreme Court resident and forceable onely, whereunto it is conveyed by their election, consent, and approbation: so that these Lords are not Lords of the Commons, nor so much as of their own Tenants, save onely in exacting of their Rents (though thus unjustly they do usurp it) but are Lords onely in or among the Commons, and so is every man Lord of his own property, how little or great soever it be; And therefore these Lords and the whole people must all be subordinate and subject to the Great Representors of the Land: But it is strongly reported, and much suspected by some, that these Lords (as their late exorbitant Actions and sayings give too great cause of surmise) would if they could paramont the House of Commons in an absolute soveraigntie of power, and so subject both them and the whole Commons of England, whom they represent, to their own Lordly, as well as to their Master the Kings DOMINATION.

For indeed were they the supreme Court of Judicature in the Land, then by vertue of that Judicative power, they might (in cases of the Commons non-concurrence) act and move alone by themselves, make Laws, Edicts, Statutes, &c. without the House of Commons, at their own Arbitrary pleasures [which usurpation would prove most desperate, and dangerous, and destructive: and therfore it behoves us to be wary and wise, for such men have ever been too subject to be puffed up with ambition and pride.] But the Power Legislative is onely resident in the House of Commons, originally derived, and legitimately issued to them from the Commoners; so that the King himself, and Lords together, cannot devise, make or establish, abolish or reverse any Law without the Commons But in cases of their non-appearance or departure, the Commons ever might do all those things. In probation whereof, I will annex the Reasons of Master John Vomel, printed Cum Privilegio, and made use of by Mr: Pryn in his Soveraigne Power of Parliaments, pag 43

When Parliaments were first begun, and ordained, there were no Prelates or Barons of the Parliament; and the Temporal Lords were very few or none: and then the King and his Commons did make a full Parliament, which Authority was never hitherto abridged: [else how could the Commons have cast the Lords Spirituall from the House?]

Again, every Baron in Parliament doth represent but his own person, & speaketh in the behalf of himself alone: But in the Knights Citizens and Burgesses are represented the Commons of the whole Realme, and every of these giveth not consent onely for himself, but for all those also for whom he is sent. And the King with the consent of the Commons had ever a sufficient and full Authority to make, ordain, and establish good and wholsome Laws for the Commonwealth. Wherefore the Lords, being lawfully summoned, and yet refusing to come, sit, or consent in Parliament, cannot by their folly abridge the King and Commons of their lawfull proceedings in Parliament: Nor yet the King in his absence abridge them, as Mr. Prin bath largely proved it in his Soveraigne Power of Parliaments. Which therefore is the Supreme or Upper, the House of Commons, or the House of Lords, I think may by this very easily be resolv’d. But to return to the Relation.

When the Lord Hunsden had call’d back his words, a Journeyman Printer began to prate against me. Then I askt him, whether he were a Lord or no? and who call’d him to speak? But the Earl of Essex commanded him to hold his peace. Then I told them, that in my proper place I would make my defence. Then the Earl askt me where was that? I answered, Gentlemen, if you be a Committee of Lords, then I appeal from you (and so consequently from the whole House of Lords) to the Commons, I mean the Knights and Burgesses assembled in Parliament, by the free Election of the people. Then the Lord Hunsden laughed at me, and in a most scornfull deriding manner (as if it were such a ridiculous thing to appeal to the Commons) he tauntingly said, What? will you Appeal to the House of Commons!) This is Lilburn-like, he must appeal to the House of Commons indeed; but when he came into Westminster-Hall, to whom then would be appeal?

Then I was commanded forthwith out of their presence into the next Roome; where standing till that most supreme Court of Judicature in the Kingdom was risen, and as the Earl of Essex passed by me, I gave him an humble salute; and that done, I put on my hat, the which the Earl espying, said, Look he stands with his hat on. Then I putting off my hat, and in a most courteous lowe manner gave him an other salute, saying, I would give unto him, as he was a Gentleman, all courteous and civill respect: that done, I put on my hat again. Then the Earl commanded my hat to be pluck’d off: whereat a Gentleman said to me, Sirra, pluck off your hat, and presently he snatch’d it off.

By this we may see what State those Lords (which in no wise doth personate or represent the Land) usurp over the Commons, as if by them they should be adorn’d as Gods; being not sufficient that persons should stand bare to them when they are in Court of Judicature, but at other times also: it is more then any one of the Upper House (to wit, of the Knights and Burgesses Assembled, both their Judges and mine) would have exacted or required.

Then some certain space after I was brought before the House of Lords; and coming to their Bar, I gave them most humble and lowe obeysance: which I mention by reason it was otherwise reported: Then the Speaker demanded of me, whether I were a Printer, or no? To whom I answered: Gentlemen, I am resolved not to make answer to any Interrogatories that shall infringe my own property, right or freedome in particular, or the rights, freedoms and properties of the Nation in generall. Whereat the whole House of Lords in a most scornfull deriding manner laughed at me, as I then conceived on purpose to dash me out of countenance, and so to hinder or weaken my just defence: but I replyed: Gentlemen, it doth not become you thus to deride me that am a prisoner at your Barre.

Whereat I was forthwith commanded out of their presence. Thus we may see to what a heavie case, and sad condition, all of us are come, that a free Commoners challenging of his own properties, rights and freedoms, must be had in derision thus openly amongst the House of Lords: and that whilest they even sit in their Supreme Court of Judicature, as they call it: as if the Seat of Justice were a place of derision, mockerie, laughter and sports; and not of Judgement, gravitie and justice: except it should be said, Such carriage, such Court. For indeed Comedies, Tragedies, Masks and Playes are far more fit for such idle kind of men. Besides it is not onely rude, uncivill, and dishonourable to those who hunt after honourable titles, and the highest places of Magistracie, but even to Magistracie it self, and therefore intolerable; for it is such an occasion of discouragement to the party arraigned, and so of disabling him in his legall and just defence against both those and other their illegall proceedings, as will scarce ever be obliterated or forgotten.

And therefore these Lords in this transcendent manner passing the bounds of that Magisteriall gravitie, discretion, modestie, and civilitie, which becometh Judges, I might well tell them that such behaviour did not become them, far lesse to me a free Commoner, with whom they had nothing to do. And being carried back to the place where I was first examined after the Superlative House arose, the Earl of Essex passing by asked me, If I had not been a Souldier, saying, it was no question which would infringe my liberty. To whom I answered: Sir, be pleased to forbear Questions, for I am resolved to answer to no Interrogatories at all. Then a little after they made my Mittimus, and sent me to Newgate Goal, a Copie whereof is as followeth.

Die Mortis 11. Augusti. 1646.

It is this day Ordered by the Lords in Parliament assembled, That Overton brought before a Committee of this House for Printing of scandalous things against this House, is hereby committed to the prison of Newgate for his high contempt offered to this House, and to the said Committee by his contemptuous words and gesture, and refusing to answer unto the Speaker. And that the said Overton shall be kept in safe custodie by the Keeper of Newgate, or his Deputie, untill the pleasure of this House be further signified.

Jo: Brown

| To the Gentleman Usher attending this House, or his Deputie, to be delivered to the Keeper of Newgate, or his Deputie | Cler: Parliam. |

| Examinat: per Ra: Brisco | |

| Clericum de Newgate. |

Thus (Sir) I have given you a full view of the most materiall proceedings, whereby you may perceive the illegality, injustice, and tyrannie of the House of Lords (vulgarly so styled) against me; the which were it simply against me in particular, it were of lesse moment; but insomuch as these Lords have intrenched actually upon the rights and properties of one Commoner in particular, they have done it virtually unto all, for by the same rule they have made this inroad upon mine, they may do it unto all: and indeed answerably they act, proceeding from one Commoner to an other, as the now depending case of these worthy and famous sufferers for their Countreys rights and freedoms in conscience, person, and estate. Liv: Coll: John Lilburne, and Mr. William Larner with his two Servants doth evidence to the world; so that if I should not have made opposition to this their violent progression and inroad upon us, I should not onely have betrayed my own Right, but (as much as in me lieth) my Countreys; with which infamy, basenesse, and infidelity I hope I shall never be stained.

But (Sir) if I may further trouble your patience, I desire you to observe the nature of this my Commitment; First, it pretends a Criminall Fact against me, to wit, the printing of scandalous things; but in case I were as criminall as is by them pretended, and it could legally be proved against me, yet they well know (however they presume) that they have no power of themselves over Commoners to passe upon them try, sentence, fine, or imprison any of them in criminall offences, and that this their presumption upon the Commoners is a Breach of the Priviledge of the House of Commons, to wit, as if the Soveraigne power were not in the Body Representative, but in themselves originall, and from them derivative, and not from the people. For the Soveraigne power to passe upon, try, sentence, fine or imprison, can extend no further then whereto it is conveyed, but from the Representers to the Represented, if the Soveraigne power is onely conveyed, and no further: Therefore these Lords being none of the peoples Vicegerents, Deputies, or Representors, cannot legally passe upon any of the Represented, to try, sentence, fine, or imprison; but such their actions (exceeding the Soveraigne compasse) must needs be illegall, and Anti-magisteriall.

And therefore as by that Soveraigne power conferr’d from the people upon the House of Commons (as I was bound) I made my Appeal unto the said House, refuting altogether to submit unto that usurpation of the Lords over the peoples properties, and Soveraignty of the House of Commons, the Body Representative, to which all Appeals are finally to be made from all other Courts and Judges whatsoever; yea from the Kings own personall resolution, in or out of any other his Courts, yea such a transcendent Tribunall it is, as from thence there Is no Appeal to any other Court, person, or persons, no not to the King himself, but onely to another Parliament: and therefore much more may our Appeals be made thereunto from the Lords.

Secondly, it declares the reason of my Commitments, to wit, for contempt against the House of Lords, and Committee of the said House both in words and gesture: but how contemptuous I was in either, by this Relation you may judge; for my gesture both before the Committee, and the whole House, was with all humble, lowly, bended obeysance, standing bare-headed before them. And if this gesture were of a contemptuous nature, let the world judge: for the other gestures and motions of my body, indeed they were according to the ordinary course of nature, I went with my face forward, set one leg before another, and the like; and if that were contemptuous, it is more then ever I was taught. Their Lordships might do well to send me to Dr: Bastwicks School of Complements, that I might have a little more venerable Courtship against the next time I appear in their presence.

For my words either before that House, or the Committee thereof, I cannot see how they can be contemptuous, except the manifestation of fidelity and resolution for the property, freedome, and liberty of the people, or indeed the making of Appeal to the House of Commons is become a contemptuous thing amongst them.

For both the one and the other was made a derision amongst them. Which gesture of theirs, might there be one impartiall judgement without respect of persons, would justly incur the censure of a more dishonourable and contemptuous nature, even to the People in generall, and to their Soveraigne Court, their own House of Commons in particular: for in the judgement of equity, the Greatnesse of men doth rather adde then diminishe, aggravate then detract from their evill. But it may be they took it in foul scorn and contempt, in that I gave them the Appelation of, Gentlemen, and of, Sir, to the Earl of Essex; But how such titles or terms could be taken in contempt, except by the spirit of pride and ambition I know not, I am sure not by the spirit of meeknesse and humility, (with which I think their Honours are not very much acquainted) for after the use and culture of the Nation they are termes of reverence, civility, and respect; but it may be, they expected more lofty, arrogant, ambitious titles of Lordship over the people, the which I forbearing, must therefore be censured, a contemptuous fellow, and be answerably rewarded with a take him Gaoler: But first they must prove themselves Lords of the Commons, before the forbearance of such titles to them be accounted and condemned as contemptuous, and legally worthy of imprisonment: Indeed they are Lords over their estates, Lands, Goods, Servants, and the like; but blessed be God, as yet they are not such Lords over the Commons, and people in general; neither yet have they legally Lordship in matter of judging, to passe upon them, condemne them, fine, censure, or imprison them in criminall things. But if for their vertues, gravity, judgement, and fidelity for the common-good they will stand to the election of the people to their Parliamentory honour, then such of them (for their virtues so chosen) may have the Title thereto, as well as the rest of the House of Commons.

Sir, this might be sufficient for this matter, yet I shall trouble you with one consideration more about it.

All contempt, opposition, or disobedience of Magistrates can be no other but such as respecteth the Statutes, Laws, and Ordinances Magisteriall, for it is the Laws onely which dignifie and distinguish them from common men and indeed such disobedience or contempt is properly against the Law, and so such contempt can at the most be but by imputation from the Law to those that are the Ministers thereof, and where there is no Law, there is no transgression.

But there is no Law, Statute, or Ordinance to binde the people of this Nation to any certain and precise form of Titles to be given to these Lords, to this or that supplicatory phrase, as, Right Honourable, may it please your Honours, my Lords, and the like; but it is left to the disposition, discretion, choice and freedome of the people, to give them what titles and terms of civility, reverence, honour and respect as seemeth good unto them; and so answerably I did. So that wherein, or how I am guilty of any legall contempt, as yet I am ignorant: If they have any Law, Statute or Ordinance to binde us in this case, then let them produce it, and let me suffer the penalty thereof.

Indeed, it is confess’d, that all Acts, Statutes and Ordinances Parliamentory do run in the name of Lords Temporall, as well as of the Commons Assembled in Parliament. But I answer. So have they done in the name of the Lords Spirituall, and when these Lords Spirituall were in their full power and pomp, was it transgression of any Law to forbear them the Titles, of My Lords Grace, William Lord Archbishop of Canterbury his Grace, Primate, and Metrapolitane of all England, and the like; yea, we have manifold proofs, examples and instances that it was no transgression at all. And so the same I demand concerning these Temporall Lords; Is it any sin, any breach of the Law now, to forbear them their towring, lofty, high-flowne titles of illegitimate honour, which are like steeples above the Commons, and instead thereof to give them good honest titles, and terms of civility and respect when we have to do with them, more then of old to forbear the Lords Spirituall their forementioned titles; when as those Bishops were every wayes more potent and powerfull then these Lords Temporall are now, or ever were.

But for the seasonable reproof which I gave them, sure they will be ashamed to account that as contemptuous, for it is the highest degree of Infamy for any man high or low, rich or poore, King or beggar, to be so indulgent to vanity and folly, as to be scornfull of a deserved reproof, and account it as a contemptuous thing, for of such an one there is no hope. So that I suppose (in the judgement of equity) I shall no more deserve to be adjudged contemptuous, for telling these Lords, That it did not become them to mock and scorn a prisoner, whom they had unjustly at their Bar, then Samuel and Himani were for telling King Saul and Asa, that they had done foolishly. 1 Sam. 13.3. 2 Chron. 15.9.

Lastly, this Order of the Lords pretends yet an other reason or ground of their imprisonment of me, namely, For refusing to Answer unto the Speaker: which by interpretation is as much as to say, Because I would not be again intangled with the late High-Commission bondage of Interrogatories (from which the Act for the Abolishment of the Star-Chamber hath made us free) therefore I must go to prison. Surely these Lords are very rash and inconsiderate, or else extreamly forgetfull of their late Votes and concurrance (however they were in their hearts I know not) with the House of Commons, against the illegality, injustice and tyrannie of such Interrogatory proceedings, that still upon such illegall grounds they should imprison the free Commoners of the Land, who by the fundamentall Laws thereof, and by this present Parliament are all legally freed from that bondage forasmuch as it is extreamly opposite, and destructive to their Great Charter of Freedoms; and so of themselves severally, their persons, estates and liberties: For thereby the Innocent are made lyable to the circumventing querks, and subtle devises, gins and traps of the crafty, secretly and insensibly couch’d to destroy the Innocent with the guilty, even to make them a prey to the malice and tyranny of the wicked; for by such their winding, turning, over-reaching Interrogatories, the simple plain-hearted, and ignorant, bring unacquainted therewith, are unawares, enforced to some inconsiderate Answer, whereby such an one is made an Offender for a word, yea guilty of that whereof he is innocent, and so accordingly unjustly proceeded against: whereas Religion, Reason, yea Nature it self doth abhor, that a man should betray, spoyl or destroy himself either of life, limbe, or liberty; for it is a principle in Nature, implanted by the finger of God, for every living moving thing defend and preserve it self from all things hurtfull, destructive, or obnoxious thereto; and this we see by daily experience is [Editor: illegible word] bruit beasts of the field; and shall then be worse then beasts? Oh ineffable, unreasonable, and inhumane! It is against flesh and blood, it is against the kind, yea against the Law of God, for a man to destroy himself; one that so doth, is guilty of no lesse then murther; and if so, then what are those, which force him to it?

Moreover, the very Law of the Land, (which of it self is a Law of Mercy, and respect in those things) bindeth no man to betray himself, for it saith, Nemo tenetur prodere seipsum; no man is bound to betray himself. I by the witnesse of honest and lawfull men of his equals (not of infamous persons) he be found guilty, then the sentence and censure of the Law must passe upon him according to his guilt, otherwise he in the eye of the Law is free, and at liberty: And therefore this present Parliament hath abolished the Star-Chamber, and High-Commission Courts.

And for these considerations I would not subject my self to those exploded, abolished, illegall, High-Commission, Interrogatory practises, refusing to answer unto any Interrogatories whatsoever, whether with me or against me, putting my self upon the legall course of the Law, not because I could not have clear’d mine innocence before them, but because I would not let go my own right and property in the equity of the Law, or be an evill president or pattern unto others, whereby they might again be entangled with this old, barbarous, illegall, Episcopall bondage by my example; rather subjecting my self to imprisonment, or to what else may unjustly be inflicted upon me or mine for my so doing, then to save my self, and my own in particular, and betray my Countrey, and Countreys in generall.

And for this I must be thrown and lie in the most contemptuous Goal of Newgate, to the undoing of my self, my wife, and children, untill the pleasure of these Lords (not the equity of the Law) be further signified: And thus to their pleasures, not to the mercy and benefit of the Law, the Free Commoners of England must be made subject: So that who can judge otherwise, but that their Laws, lives, liberties and estates are hereby made a prey to their Arbitrary pleasures? But I hope the House of Commons will no longer sit still, and behold their Lordships thus to devour up the Commoners of the Land one after an other, as if it were a far off thing, and did not so neerly concern both themselves and the whole Commons of England, who are present, and are bound to defend; for you see these Lords have got Liu: Coll: John Lilburn, Mr. William Larner, and my self also into their Jaws; and for ought I see, such is their greedinesse, that we are all likely to be swallowed down quick, except the House of Commons step in with a present delivery: but however their Lordships may pray that Little Martin come not into the number, for he’l serve their Arbitrary pleasures, their Prerogatives, and all such other their toyes and trinkets which are not for the weal of the people, little better then the Presbyters Tyth-cocks, milk pails, bowls and cream pots, &c. See Mar. Eccho, and Arraignment of Persecution

Thus (Sir) I have presumed upon your patience to empty my self of those present conceptions, which (though tedious) I suppose of your self will be taken in good part, and therefore I have the more emboldned my self to open my mind freely unto you, being strongly assured of your good construction. But lest through some accidentall means these my papers should become publick, I would have the world know, that the premises, words or sentences therein contained, are not intended against any person, or persons, to wit, of Kings, Lords, or others therein mentioned, or for the Alteration of Government, by the fundamentall Laws of this Realm established, or for the depressing of any Magisteriall officers from their true Magisteriall Functions and Offices, as may unhappily by some evill minded men be concluded; but the whole matter both for word and circumstance of the premises aforesaid (to you directed) is simply and onely against illegality, injustice, oppression and tyranny over the free people of England, their rights, properties and freedoms; whether by Kings, Lords, or any other unjustly and illegally exercised upon them, and this and no other meaning, sense, or signification of the foresaid matter, words or sentences either in part, or in whole is intended or meant; and therefore in that sense onely, and no other whatsoever, I present them unto you, or to whomsoever they may come, to be accepted and construed: for indeed I do professe my self an absolute enemy to all injustice, tyranny and cruelty whatsoever, or in whomsoever, and no otherwise.

Thus, Sir, with the remembrance of my love, and kinde respects unto your wife and children, and to all other our Christian friends and brethren, I rest

| From the most infamous Goal of Newgate. | Mine own no longer, but yours, and my Countreys, till death separate us. |

| August, 17. 1646. | R. Overton. |

The Publishers to the Reader.

Courteous Reader, we have been demanded of many, whether or no this our worthy friend, be that reverend peece of sanctity, usually dignified or distinguished by the name of Young Martin Mar-Priest? Unto whom we have given the same answer, that was given by the parents of that blind man mentioned in the Gospel, when the Scribes and Pharisees asked them, by what means he received his sight? He is old enough (said they) ask him, he will answer for himself: But here’s the mischief, that this our honoured friend, will not answer to Interrogatories, as we our selves have refused to do in this matter, and so they not a whit the nearer to be resolved.

But howsoever, whether he be that young Martin, or some other bird of that feather or no, it is no disparagement to his worth; for although some neutrals (that are neither hot nor cold) are far readier with their railing words (then good deeds to any in distresse) to endeavour rather to blaze the infirmities, then expresse the vertues of all such as do surpasse themselves in any publick good, yet both this our loving friend, and some other worthies, chiefly those in bonds, have not onely laboured more abundantly, but stood more constantly then thousands of such self-lovers and temporizers; the one in truly informing the free Commons of England (both by word and writing) of their just freedoms as well spirituall as temporall; and the other so valiantly opposing all sorts of Arbitrary usurpers whosoever, whether Kings, Lords, Commons, or Clergie, without respect of persons, and that in defence of those freedoms, not onely in the behalf of themselves and posterities, but likewise of all the Commons of England in generall, whether friends or enemies.

In which doing & opposing, if this rare man, or such as he be either neglected or traduced, by those of whom they ought to be maintained, encouraged and advanced, chiefly now in their suffering condition, for the just common cause, as thus standing in the gap for them and all the free Commoners of England (even as well their mortall enemies as dearest friends) whereof too many are not indued with such fidelity, magnanimity nor ingenuity, if they were or had been so tried and winnowed as these, will it not be very just with God, that he permit such ingrate, double minded, time-serving, and self-seeking men to be intangled again with the yoke both of spirituall and temporall bondage, wherewith both God and man have made them free, that will not so much as speak a good word, far lesse do a good deed, to those that stand thus fast for them, who have not spirit nor courage to stand for themselves; and that now after the loosing of so many thousands of lives, and multitudes of estates, both in defence and recovery of these our just freedoms? Yea, and this persecuted means of unlicenced Printing hath done more good to the people, then all the bloodie wars, the one tending to rid us quite of all slavery; but the other onely to rid us of one, and involve us into another. Farewell.