JOHN MILTON,

The Readie and Easie Way to establish a Free Commonwealth (1660)

|

|

| John Milton (1608-1674) |

[Created: 21 May, 2023]

[Updated: May 21, 2023 ] |

The Guillaumin Collection

|

This title is part of “The Guillaumin Collection” within “The Digital Library of Liberty and Power”. It has been more richly coded and has some features which other titles in the library do not have, such as the original page numbers, formatting which makes it look as much like the original text as possible, and a citation tool which makes it possible for scholars to link to an individual paragraph which is of interest to them. These titles are also available in a variety of eBook formats for reading on portable devices. |

Source

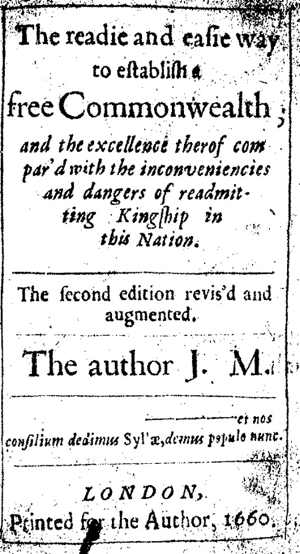

, The readie and easie way to establish a free Commonwealth; and the excellence therof com par'd with the inconveniencies and dangers of readmitting Kingship in this Nation. The second edition revis'd and augmented. The author J. M. (London: Printed for the Author, 1660).http://davidmhart.com/liberty/Levellers/Milton/1660-FreeCommonwealth/index.html

John Milton, The readie and easie way to establish a free Commonwealth; and the excellence therof com par'd with the inconveniencies and dangers of readmitting Kingship in this Nation. The second edition revis'd and augmented. The author J. M. (London: Printed for the Author, 1660).

This title is also available in a facsimile PDF of the original and various eBook formats - HTML, PDF, and ePub.

This book is part of a collection of works by John Milton (1608-1674).

The Readie and Easie Way to establish a Free Commonwealth.

———et nos

consilium dedimus Syl'ae, demus populo nunc.

We have advised

Sulla himself, advise we now the People.

ALthough since the writing of this treatise, the face of things hath had som change, writs for new elections have bin recall'd, and the members at first chosen, readmitted from exclusion, yet not a little rejoicing to hear declar'd the resolution of those who are in power, tending to the establishment of a free Commonwealth, and to remove, if it be possible, this [4] noxious humor of returning to bondage, instilld of late by som deceivers, and nourishd from bad principles and fals apprehensions among too many of the people, I thought best not to suppress what I had written, hoping that it may now be of much more use and concernment to be freely publishd, in the midst of our Elections to a free Parlament, or their sitting to consider freely of the Government; whom it behoves to have all things represented to them that may direct thir judgment therin; and I never read of any State, scarce of any tyrant grown so incurable as to refuse counsel from [5] any in a time of public deliberation; much less to be offended. If thir absolute determination be to enthrall us, before so long a Lent of Servitude, they may permitt us a little Shroving-time first, wherin to speak freely, and take our leaves of Libertie. And because in the former edition through haste, many faults escap'd, and many books were suddenly dispersd, ere the note to mend them could be sent, I took the opportunitie from this occasion to revise and somwhat to enlarge the whole discourse, especially that part which argues for a perpetual Senat. The treatise thus revis'd and enlarg'd, is as follows.

[6]

The Parliament of England, assisted by a great number of the people who appeerd and stuck to them faithfullest in defence of religion and thir civil liberties, judging kingship by long experience a government unnecessarie, burdensom and dangerous, justly and magnanimously abolishd it; turning regal bondage into a free Commonwealth, to the admiration and terrour of our emulous neighbours. They took themselves not bound by the light of nature or religion, to any former covnant, from which the King himself by many forfeitures of a latter date or discoverie, and our [7] own longer consideration theron had more & more unbound us, both to himself and his posteritie; as hath bin ever the justice and the prudence of all wise nations that have ejected tyrannie. They covnanted to preserve the Kings person and autoritie in the preservation of the true religion and our liberties; not in his endeavoring to bring in upon our consciences a Popish religion, upon our liberties thraldom, upon our lives destruction, by his occasioning, if not complotting, as was after discoverd, the Irish massacre, his fomenting and arming the rebellion, his covert leaguing with the rebels against us, his refusing more [8] then seaven times, propositions most just and necessarie to the true religion and our liberties, tenderd him by the Parlament both of England and Scotland. They made not thir covnant concerning him with no difference between a king and a god, or promisd him as Job did to the Almightie, to trust in him, though he slay us: they understood that the solemn ingagement, wherin we all forswore kingship, was no more a breach of the covant, then the covnant was of the protestation before, but a faithful and prudent going on both in the words, well weighd, and in the true sense of the covnant, without respect [9] of persons, when we could not serve two contrary maisters, God and the king, or the king and that more supreme law, sworn in the first place to maintain, our safetie and our libertie. They knew the people of England to be a free people, themselves the representers of that freedom; & although many were excluded, & as many fled (so they pretended) from tumults to Oxford, yet they were left a sufficient number to act in Parlament; therefor not bound by any statute of preceding Parlaments; but by the law of nature only, which is the only law of laws truly and properly to all mankinde fundamental; the beginning and [10] the end of all Government; to which no Parlament or people that will throughly reforme, but may and must have recourse; as they had and must yet have in church reformation (if they throughly intend it) to evangelic rules; not to ecclesiastical canons, though never so ancient, so ratifi'd and establishd in the land by Statutes, which for the most part are meer positive laws, neither natural nor moral, & so by any Parlament for just and serious considerations, without scruple to be at any time repeal'd. If others of thir number, in these things were under force, they were not, but under free conscience; if others were [11] excluded by a power which they could not resist, they were not therefore to leave the helm of government in no hands, to discontinue thir care of the public peace and safetie, to desert the people in anarchie and confusion; no more then when so many of thir members left them, as made up in outward formalitie a more legal Parlament of three estates against them. The best affected also and best principl'd of the people, stood not numbring or computing on which side were most voices in Parlament, but on which side appeerd to them most reason, most safetie, when the house divided upon [12] main matters: what was well motiond and advis'd, they examind not whether fear or perswasion carried it in the vote; neither did they measure votes and counsels by the intentions of them that voted; knowing that intentions either are but guessd at, or not soon anough known; and although good, can neither make the deed such, nor prevent the consequence from being bad: suppose bad intentions in things otherwise welldon; what was welldon, was by them who so thought, not the less obey'd or followd in the state; since in the church, who had not rather follow Iscariot or Simon the magician, [13] though to covetous ends, preaching, then Saul, though in the uprightness of his heart persecuting the gospell? Safer they therefor judgd what they thought the better counsels, though carried on by some perhaps to bad ends, then the wors, by others, though endevord with best intentions: and yet they were not to learn that a greater number might be corrupt within the walls of a Parlament as well as of a citie; wherof in matters of neerest concernment all men will be judges; nor easily permitt, that the odds of voices in thir greatest councel, shall more endanger them by corrupt or credulous votes, then [14] the odds of enemies by open assaults; judging that most voices ought not alwaies to prevail where main matters are in question; if others hence will pretend to disturb all counsels, what is that to them who pretend not, but are in real danger; not they only so judging, but a great though not the greatest, number of thir chosen Patriots, who might be more in waight, then the others in number; there being in number little vertue, but by weight and measure wisdom working all things: and the dangers on either side they seriously thus waighd: from the treatie, short fruits of long labours and seaven [15] years warr; securitie for twenty years, if we can hold it; reformation in the church for three years: then put to shift again with our vanquishd maister. His justice, his honour, his conscience declar'd quite contrarie to ours; which would have furnishd him with many such evasions, as in a book entitl'd an inquisition for blood, soon after were not conceald: bishops not totally remov'd, but left as it were in ambush, a reserve, with ordination in thir sole power; thir lands alreadie sold, not to be alienated, but rented, and the sale of them call'd sacrilege; delinquents few of many brought to condigne punishment; [16] accessories punishd; the chief author, above pardon, though after utmost resistance, vanquish'd; not to give, but to receive laws; yet besought, treated with, and to be thankd for his gratious concessions, to be honourd, worshipd, glorifi'd. If this we swore to do, with what righteousness in the sight of God, with what assurance that we bring not by such an oath the whole sea of bloodguiltiness upon our own heads? If on the other side we preferr a free government, though for the present not obtaind, yet all those suggested fears and difficulties, as the event will prove, easily [17] overcome, we remain finally secure from the exasperated regal power, and out of snares; shall retain the best part of our libertie, which is our religion, and the civil part will be from these who deferr us, much more easily recoverd, being neither so suttle nor so awefull as a King reinthron'd. Nor were thir actions less both at home and abroad then might become the hopes of a glorious rising Commonwealth: nor were the expressions both of armie and people, whether in thir publick declarations or several writings other then such as testifi'd a spirit in this nation no less noble and well fitted to the liberty of a Commonwealth, [18] then in the ancient Greeks or Romans. Nor was the heroic cause unsuccesfully defended to all Christendom against the tongue of a famous and thought invincible adversarie; nor the constancie and fortitude that so nobly vindicated our liberty, our victory at once against two the most prevailing usurpers over mankinde, superstition and tyrannie unpraisd or uncelebrated in a written monument, likely to outlive detraction, as it hath hitherto covinc'd or silenc'd not a few of our detractors, especially in parts abroad. After our liberty and religion thus prosperously fought for, gaind [19] and many years possessd, except in those unhappie interruptions, which God hath remov'd, now that nothing remains, but in all reason the certain hopes of a speedie and immediat settlement for ever in a firm and free Commonwealth, for this extolld and magnifi'd nation, regardless both of honour wonn or deliverances voutsaf't from heaven, to fall back or rather to creep back so poorly as it seems the multitude would to thir once abjur'd and detested thraldom of Kingship, to be our selves the slanderers of our own just and religious deeds, though don by som to covetous and ambitious ends, [20] yet not therefor to be staind with their infamie, or they to asperse the integritie of others, and yet these now by revolting from the conscience of deeds welldon both in church and state, to throw away and forsake, or rather to betray a just and noble cause for the mixture of bad men who have ill manag'd and abus'd it (which had our fathers don heretofore, and on the same pretence deserted true religion, what had long ere this become of our gospel and all protestant reformation so much intermixt with the avarice and ambition of som reformers?) and by thus relapsing, to verifie all the [21] bitter predictions of our triumphing enemies, who will now think they wisely discernd and justly censur'd both us and all our actions as rash, rebellious, hypocritical and impious, not only argues a strange degenerate contagion suddenly spread among us fitted and prepar'd for new slaverie, but will render us a scorn and derision to all our neighbours. And what will they at best say of us and of the whole English name, but scoffingly as of that foolish builder, mentiond by our Saviour, who began to build a tower, and was not able to finish it. Where is this goodly tower of a Commonwealth, which the English boasted [22] they would build to overshaddow kings, and be another Rome in the west? The foundation indeed they laid gallantly; but fell into a wors confusion, not of tongues, but of factions, then those at the tower of Babel; and have left no memorial of thir work behinde them remaining, but in the common laughter of Europ. Which must needs redound the more to our shame, if we but look on our neighbours the United Provinces, to us inferior in all outward advantages; who notwithstanding, in the midst of greater difficulties, courageously, wisely, constantly went through with the same work, [23] and are setl'd in all the happie enjoiments of a potent and flourishing Republic to this day.

Besides this, if we returne to Kingship, and soon repent, as undoubtedly we shall, when we begin to finde the old encroachments coming on by little and little upon our consciences, which must necessarily proceed from king and bishop united inseparably in one interest, we may be forc'd perhaps to fight over again all that we have fought, and spend over again all that we have spent, but are never like to attain thus far as we are now advanc'd to the recoverie of our freedom, never to have [24] it in possession as we now have it, never to be voutsaf't heerafter the like mercies and signal assistances from heaven in our cause, if by our ingratefull backsliding we make these fruitless; flying now to regal concessions from his divine condescensions and gratious answers to our once importuning praiers against the tyrannie which we then groand under: making vain and viler then dirt the blood of so many thousand faithfull and valiant English men, who left us in this libertie, bought with thir lives; losing by a strange after game of folly, all the battels we have wonn, together with all Scotland as to our conquest, [25] hereby lost, which never any of our kings could conquer, all the treasure we have spent, not that corruptible treasure only, but that far more precious of all our late miraculous deliverances; treading back again with lost labour all our happie steps in the progress of reformation; and most pittifully depriving our selves the instant fruition of that free government which we have so dearly purchasd, a free Commonwealth, not only held by wisest men in all ages the noblest, the manliest, the equallest, the justest government, the most agreeable to all due libertie and proportiond equalitie, both human, civil, and [26] Christian, most cherishing to vertue and true religion, but also (I may say it with greatest probabilitie) planely commended, or rather enjoind by our Saviour himself, to all Christians, not without remarkable disallowance, and the brand of gentilism upon kingship. God in much displeasure gave a king to the Israelites, and imputed it a sin to them that they sought one: but Christ apparently forbids his disciples to admitt of any such heathenish government: the kings of the gentiles, saith he, exercise lordship over them; and they that exercise authoritie upon them, are call'd benefactors: but ye shall not be so; but he that [27] is greatest among you, let him be as the younger; and he that is chief, as he that serveth. The occasion of these his words was the ambitious desire of Zebede's two sons, to be exalted above thir brethren in his kingdom, which they thought was to be ere long upon earth. That he speaks of civil government, is manifest by the former part of the comparison, which inferrs the other part to be alwaies in the same kinde. And what government coms neerer to this precept of Christ, then a free Commonwealth; wherin they who are greatest, are perpetual servants and drudges to the public at thir own cost and [28] charges, neglect thir own affairs; yet are not elevated above thir brethren; live soberly in thir families, walk the streets as other men, may be spoken to freely, familiarly, friendly, without adoration. Wheras a king must be ador'd like a Demigod, with a dissolute and haughtie court about him, of vast expence and luxurie, masks and revels, to the debaushing of our prime gentry both male and female; not in thir passetimes only, but in earnest, by the loos imploiments of court service, which will be then thought honorable. There will be a queen also of no less charge; in most likelihood outlandish [29] and a Papist; besides a queen mother such alreadie; together with both thir courts and numerous train: then a royal issue, and ere long severally thir sumptuous courts; to the multiplying of a servile crew, not of servants only, but of nobility and gentry, bred up then to the hopes not of public, but of court offices; to be stewards, chamberlains, ushers, grooms, even of the close-stool; and the lower thir mindes debas'd with court opinions, contrarie to all vertue and reformation, the haughtier will be thir pride and profuseness: we may well remember this not long since at home; or need but [30] look at present into the French court, where enticements and preferments daily draw away and pervert the Protestant Nobilitie. As to the burden of expence, to our cost we shall soon know it; for any good to us, deserving to be termd no better then the vast and lavish price of our subjection and their debausherie; which we are now so greedily cheapning, and would so fain be paying most inconsideratly to a single person; who for any thing wherin the public really needs him, will have little els to do, but to bestow the eating and drinking of excessive dainties, to set a pompous [31] face upon the superficial actings of State, to pageant himself up and down in progress among the perpetual bowings and cringings of an abject people, on either side deifying and adoring him for nothing don that can deserve it. For what can hee more then another man? who even in the expression of a late courtpoet, sits only like a great cypher set to no purpose before a long row of other significant figures. Nay it is well and happy for the people if thir King be but a cypher, being oft times a mischief, a pest, a scourge of the nation, and which is wors, not to be remov'd, not [32] to be controul'd, much less accus'd or brought to punishment, without the danger of a common ruin, without the shaking and almost subversion of the whole land. Wheras in a free Commonwealth, any governor or chief counselor offending, may be remov'd and punishd without the least commotion. Certainly then that people must needs be madd or strangely infatuated, that build the chief hope of thir common happiness or safetie on a single person: who if he happen to be good, can do no more then another man, if to be bad, hath in his hands to do more evil without check, then millions of other [33] men. The happiness of a nation must needs be firmest and certainest in a full and free Councel of thir own electing, where no single person, but reason only swaies. And what madness is it, for them who might manage nobly thir own affairs themselves, sluggishly and weakly to devolve all on a single person; and more like boyes under age then men, to committ all to his patronage and disposal, who neither can performe what he undertakes, and yet for undertaking it, though royally paid, will not be thir servant, but thir lord? how unmanly must it needs be, to count such [34] a one the breath of our nostrils, to hang all our felicity on him, all our safetie, our well-being, for which it we were aught els but sluggards or babies, we need depend on none but God and our own counsels, our own active vertue and industrie; Go to the Ant, thou sluggard, saith Solomon; consider her waies, and be wise; which having no prince, ruler, or lord, provides her meat in the summer, and gathers her food in the harvest. which evidenly shews us, that they who think the nation undon without a king, though they look grave or haughtie, have not so much true spirit and understanding in them [35] as a pismire: neither are these diligent creatures hence concluded to live in lawless anarchie, or that commended, but are set the examples to imprudent and ungovernd men, of a frugal and selfgoverning democratie or Commonwealth; safer and more thriving in the joint providence and counsel of many industrious equals, then under the single domination of one imperious Lord. It may be well wonderd that any Nation styling themselves free, can suffer any man to pretend hereditarie right over them as thir lord; when as by acknowledging that right, they conclude themselves his [36] servants and his vassals, and so renounce thir own freedom. Which how a people and thir leaders especially can do, who have fought so gloriously for liberty, how they can change thir noble words and actions, heretofore so becoming the majesty of a free people, into the base necessitie of court flatteries and prostrations, is not only strange and admirable, but lamentable to think on. That a nation should be so valorous and courageous to winn thir liberty in the field, and when they have wonn it, should be so heartless and unwise in thir counsels, as not to know how to use it, value it, what to do withit [37] or with themselves; but after ten or twelve years prosperous warr and contestation with tyrannie, basely and besottedly to run their necks again into the yoke which they have broken, and prostrate all the fruits of thir victorie for naught at the feet of the vanquishd, besides our loss of glorie, and such an example as kings or tyrants never yet had the like to boast of, will be an ignomine if it befall us, that never yet befell any nation possessd of thir libertie; worthie indeed themselves, whatsoever they be, to be for ever slaves: but that part of the nation which consents not with them, as I perswade me [38] of a great number, far worthier then by their means to be brought into the same bondage. Considering these things so plane, so rational, I cannot but yet furder admire on the other side, how any man who hath the true principles of justice and religion in him, can presume or take upon him to be a king and lord over his brethren, whom he cannot but know whether as men or Christians, to be for the most part every way equal or superior to himself: how he can display with such vanitie and ostentation his regal splendor so supereminently above other mortal men; or being a Christian, can assume [39] such extraordinarie honour and worship to himself, while the kingdom of Christ our common King and Lord, is hid to this world, and such gentilish imitation forbid in express words by himself to all his disciples. All Protestants hold that Christ in his church hath left no vicegerent of his power, but himself without deputie, is the only head therof, governing it from heaven: how then can any Christianman derive his kingship from Christ, but with wors usurpation then the Pope his headship over the church, since Christ not only hath not left the least shaddow of a command for any such vicegerence [40] from him in the State, as the Pope pretends for his in the Church, but hath expressly declar'd, that such regal dominion is from the gentiles, not from him, and hath strictly charg'd us, not to imitate them therin.

I doubt not but all ingenuous and knowing men will easily agree with me, that a free Commonwealth without single person or house of lords, is by far the best government, if it can be had; but we have all this while say they bin expecting it, and cannot yet attain it. Tis true indeed, when monarchie was dissolvd, the form of a Commonwealth should have forthwith bin fram'd; and the [41] practice therof immediatly begun; that the people might have soon bin satisfi'd and delighted with the decent order, ease and benefit therof: we had bin then by this time firmly rooted, past fear of commotions or mutations, & now flourishing: this care of timely setling a new government instead of ye old, too much neglected, hath bin our mischief. Yet the cause therof may be ascrib'd with most reason to the frequent disturbances, interruptions and dissolutions which the Parlament hath had partly from the impatient or disaffected people, partly from som ambitious leaders in the Armie; much contrarie, I beleeve, to the mind and [42] approbation of the Armie it self and thir other Commanders, once undeceivd, or in thir own power. Now is the opportunitie, now the very season wherein we may obtain a free Commonwealth and establish it for ever in the land, without difficulty or much delay. Writs are sent out for elections, and which is worth observing in the name, not of any king, but of the keepers of our libertie, to summon a free Parlament: which then only will indeed be free, and deserve the true honor of that supreme title, if they preserve us a free people. Which never Parlament was more free to do; being now call'd, not as heretofore, [43] by the summons of a king, but by the voice of libertie: and if the people, laying afide prejudice and impatience, will seriously and calmly now consider thir own good both religious and civil, thir own libertie and the only means thereof, as shall be heer laid before them, and will elect thir Knights and Burgesses able men, and according to the just and necessarie qualifications (which for aught I hear, remain yet in force unrepeald, as they were formerly decreed in Parlament) men not addicted to a single person or house of lords, the work is don; at least the foundation firmly laid of a free Commonwealth, [44] and good part also erected of the main structure. For the ground and basis of every just and free government (since men have smarted so oft for commiting all to one person) is a general councel of ablest men, chosen by the people to consult of public affairs from time to time for the common good. In this Grand Councel must the sovrantie, not transferrd, but delegated only, and as it were deposited, reside; with this caution they must have the forces by sea and land committed to them for preservation of the common peace and libertie; must raise and manage the public revenue, at least with som inspectors [45] deputed for satisfaction of the people, how it is imploid; must make or propose, as more expressly shall be said anon, civil laws; treat of commerce, peace, or warr with forein nations, and for the carrying on som particular affairs with more secrecie and expedition, must elect, as they have alreadie out of thir own number and others, a Councel of State.

And although it may seem strange at first hearing, by reason that mens mindes are prepossed with the notion of successive Parlaments, I affirme that the Grand or General Councel being well chosen, should be perpetual: for so [46] thir business is or may be, and oft times urgent; the opportunitie of affairs gaind or lost in a moment. The day of counsel cannot be set as the day of a festival; but must be readie alwaies to prevent or answer all occasions. By this continuance they will become everie way skilfullest, best provided of intelligence from abroad, best acquainted with the people at home, and the people with them. The ship of the Commonwealth is alwaies under sail; they sit at the stern; and if they stear well, what need is ther to change them; it being rather dangerous? And to this, that the Grand Councel is both [47] foundation and main pillar of the whole State; and to move pillars and foundations, not faultie, cannot be safe for the building. I see not therefor, how we can be advantag'd by successive and transitorie Parlaments; but that they are much likelier continually to unsettle rather then to settle a free government; to breed commotions, changes, novelties and uncertainties; to bring neglect upon present affairs and opportunities, while all mindes are suspense with expectation of a new assemblie, and the assemblie for a good space taken up with the new setling of it self. After which, if they finde no great work to do, [48] they will make it, by altering or repealing former acts, or making and multiplying new; that they may seem to see what thir predecessors saw not, and not to have assembld for nothing: till all law be lost in the multitude of clashing statutes. But if the ambition of such as think themselves injur'd that they also partake not of the government, and are impatient till they be chosen, cannot brook the perpetuitie of others chosen before them, or if it be feard that long continuance of power may corrupt sincerest men, the known expedient is, and by som lately propounded, that annually (or if the space be longer, [49] so much perhaps the better) the third part of Senators may go out according to the precedence of thir election, and the like number be chosen in thir places, to prevent the setling of too absolute a power, if it should be perpetual: and this they call partial rotation. But I could wish that this wheel or partial wheel in State, if it be possible, might be avoided; as having too much affinitie with the wheel of fortune. For it appeers not how this can be don, without danger and mischance of putting out a great number of the best and ablest: in whose stead new elections may bring in [50] as many raw, unexperienc'd and otherwise affected, to the weakning and much altering for the wors of public transactions▪ Neither do I think a perpetual Senat, especially chosen and entrusted by the people, much in this land to be feard, where the well-affected either in a standing armie, or in a setled militia have thir arms in thir own hands. Safest therefor to me it seems and of least hazard or interruption to affairs, that none of the Grand Councel be mov'd, unless by death or just conviction of som crime: for what can be expected firm or stedfast from a floating foundation? however, I forejudge [51] not any probable expedient, any temperament that can be found in things of this nature so disputable on either side. Yet least this which I affirme, be thought my single opinion, I shall add sufficient testimonie. Kingship it self is therefor counted the more safe and durable, because the king and, for the most part, his councel, is not chang'd during life: but a Commonwealth is held immortal; and therin firmest, safest and most above fortune: for the death of a king, causeth ofttimes many dangerous alterations; but the death now and then of a Senator is not felt; the main bodie of them still continuing permanent [52] in greatest and noblest Commonwealths, and as it were eternal. Therefor among the Jews, the supreme councel of seaventie, call'd the Sanhedrim, founded by Moses, in Athens, that of Areopagus, in Sparta, that of the Ancients, in Rome, the Senat, consisted of members chosen for term of life; and by that means remaind as it were still the same to generations. In Venice they change indeed ofter then every year som particular councels of State, as that of six, or such other; but the true Senat, which upholds and sustains the government, is the whole aristocracie immovable. So in the United Provinces, the [53] States General, which are indeed but a councel of st te deputed by the whole union, are not usually the same persons for above three or six years; but the States of every citie, in whom the sovrantie hath bin plac'd time out of minde, are a standing Senat, without succession, and accounted chiefly in that regard the main prop of thir liberty. And why they should be so in every well orderd Commonwealth, they who write of policie, give these reasons; "That to make the Senat successive, not only impairs the dignitie and lustre of the Senat, but weakens the whole Commonwealth, and [54] brings it into manifest danger; while by this means the secrets of State are frequently divulgd, and matters of greatest consequence committed to inexpert and novice counselors, utterly to seek in the full and intimate knowledge of affairs past." I know not therefor what should be peculiar in England to make successive Parlaments thought safest, or convenient here more then in other nations, unless it be the fickl'ness which is attributed to us as we are Ilanders: but good education and acquisit wisdom ought to correct the fluxible fault, if any such be, of our watry situation. It [55] will be objected, that in those places where they had perpetual Senats, they had also popular remedies against thir growing too imperious: as in Athens, besides Areopagus, another Senat of four or five hunderd; in Sparta, the Ephors; in Rome, the Tribunes of the people. But the event tels us, that these remedies either little availd the people, or brought them to such a licentious and unbridl'd democratie, as in fine ruind themselves with thir own excessive power. So that the main reason urg'd why popular assemblies are to be trusted with the peoples libertie, rather then a Senat of principal men, because [56] great men will be still endeavoring to inlarge thir power, but the common sort will be contented to maintain thir own libertie, is by experience found false; none being more immoderat and ambitious to amplifie thir power, then such popularities; which was seen in the people of Rome; who at first contented to have thir Tribunes, at length contended with the Senat that one Consul, then both; soon after, that the Censors and Praetors also should be created Plebeian, and the whole empire put into their hands; adoring lastly those, who most were advers to the Senat, till Marius by fulfilling thir inordinat [57] desires, quite lost them all the power for which they had so long bin striving, and left them under the tyrannie of Sylla: the ballance therefor must be exactly so set, as to preserve and keep up due autoritie on either side, as well in the Senat as in the people. And this annual rotation of a Senat to consist of three hunderd, as is lately propounded, requires also another popular assembly upward of a thousand, with an answerable rotation. Which besides that it will be liable to all those inconveniencies found in the foresaid remedies, cannot but be troublesom and chargeable, both in thir motion and thir session, to the whole land; unweildie with [58] thir own bulk, unable in so great a number to mature thir consultations as they ought, if any be allotted them, and that they meet not from so many parts remote to sit a whole year lieger in one place, only now and then to hold up a forrest of fingers, or to convey each man his bean or ballot into the box, without reason shewn or common deliberation; incontinent of secrets, if any be imparted to them, emulous and always jarring with the other Senat. The much better way doubtless will be in this wavering condition of our affairs, to deferr the changing or circumscribing of our Senat, more then may be done with ease, [59] till the Commonwealth be throughly setl'd in peace and safetie, and they themselves give us the occasion. Militarie men hold it dangerous to change the form of battel in view of an enemie: neither did the people of Rome bandie with thir Senat while any of the Tarquins livd, the enemies of thir libertie, nor sought by creating Tribunes to defend themselves against the fear of thir Patricians, till sixteen years after the expulsion of thir kings, and in full securitie of thir state, they had or thought they had just cause given them by the Senat. Another way will be, to welqualifie and refine elections: [60] not committing all to the noise and shouting of a rude multitude, but permitting only those of them who are rightly qualifi'd, to nominat as many as they will; and out of that number others of a better breeding, to chuse a less number more judiciously, till after a third or fourth sifting and refining of exactest choice, they only be left chosen who are the due number, and seem by most voices the worthiest. To make the people fittest to chuse, and the chosen fittest to govern, will be to mend our corrupt and faulty education, to teach the people faith not without vertue, temperance, modestie, sobrietie, parsimonie, [61] justice; not to admire wealth or honour; to hate turbulence and ambition; to place every one his privat welfare and happiness in the public peace, libertie and safetie. They shall not then need to be much mistrustfull of thir chosen Patriots in the Grand Councel; who will be then rightly call'd the true keepers of our libertie, though the most of thir business will be in forein affairs. But to prevent all mistrust, the people then will have thir several ordinarie assemblies (which will henceforth quite annihilate the odious power and name of Committies) in the chief towns of every countie, without the [62] trouble, charge, or time lost of summoning and assembling from far in so great a number, and so long residing from thir own houses, or removing of thir families, to do as much at home in thir several shires, entire or subdivided, toward the securing of thir libertie, as a numerous assembly of them all formd and conven'd on purpose with the wariest rotation. Wher of I shall speak more ere the end of this discourse: for it may be referrd to time, so we be still going on by degrees to perfection. The people well weighing and performing these things, I suppose would have no cause to fear, though the Parlament, [63] abolishing that name, as originally signifying but the parlie of our Lords and Commons with thir Norman king when he pleasd to call them, should, with certain limitations of thir power, sit perpetual, if thir ends be faithfull and for a free Commonwealth, under the name of a Grand or General Councel. Till this be don, I am in doubt whether our State will be ever certainly and throughly setl'd; never likely till then to see an end of our troubles and continual changes or at least never the true settlement and assurance of our libertie. The Grand Councel being thus firmly constituted to perpetuitie, and still, upon [64] the death or default of any member, suppli'd and kept in full number, ther can be no cause alleag'd why peace, justice, plentifull trade and all prosperitie should not thereupon ensue throughout the whole land; with as much assurance as can be of human things, that they shall so continue (if God favour us, and our wilfull sins provoke him not) even to the coming of our true and rightfull and only to be expected King, only worthie as he is our only Saviour, the Messiah, the Christ, the only heir of his eternal father, the only by him anointed and ordaind since the work of our redemption finishd, [65] Vniversal Lord of all mankinde. The way propounded is plane, easie and open before us; without intricacies, without the introducement of new or obsolete forms, or terms, or exotic models; idea's that would effect nothing, but with a number of new injunctions to manacle the native liberty of mankinde; turning all vertue into prescription, servitude, and necessitie, to the great impairing and frustrating of Christian libertie: I say again, this way lies free and smooth before us; is not tangl'd with inconveniencies; invents no new incumbrances; requires no perilous, no injurious alteration or circumscription [66] of mens lands and proprieties; secure, that in this Commonwealth, temporal and spiritual lords remov'd, no man or number of men can attain to such wealth or vast possession, as will need the hedge of an Agrarian law (never succesful, but the cause rather of sedition, save only where it began seasonably with first possession) to confine them from endangering our public libertie; to conclude, it can have no considerable objection made against it, that it is not practicable: least it be said hereafter, that we gave up our libertie for want of a readie way or distinct form propos'd of a free [67] Commonwealth. And this facilitie we shall have above our next neighbouring Commonwealth (if we can keep us from the fond conceit of somthing like a duke of Venice, put lately into many mens heads, by som one or other sutly driving on under that notion his own ambitious ends to lurch a crown) that our liberty shall not be hamperd or hoverd over by any ingagement to such a potent familie as the house of Nassaw of whom to stand in perpetual doubt and suspicion, but we shall live the cleerest and absolutest free nation in the world.

On the contrarie, if ther be a king, which the inconsiderate [68] multitude are now so madd upon, mark how far short we are like to com of all those happinesses, which in a free state we shall immediatly be possessd of. First, the Grand Councel, which, as I shewd before, should sit perpetually (unless thir leisure give them now and then som intermissions or vacations, easilie manageable by the Councel of State left sitting) shall be call'd, by the kings good will and utmost endeavor, as seldom as may be. For it is only the king's right, he will say, to call a parlament; and this he will do most commonly about his own affairs rather then the kingdom's, as will [69] appeer planely so soon as they are call'd. For what will thir business then be and the chief expence of thir time, but an endless tugging between petition of right and and royal prerogative, especially about the negative voice, militia, or subsidies, demanded and oft times extorted without reasonable cause appeering to the Commons, who are the only true representatives of the people, and thir libertie, but will be then mingl'd with a court-faction; besides which within thir own walls, the sincere part of them who stand faithfull to the people, will again have to deal with two troublesom counter-working [70] adversaries from without, meer creatures of the king, spiritual, and the greater part, as is likeliest, of temporal lords, nothing concernd with the peoples libertie. If these prevail not in what they please, though never so much against the peoples interest, the Parlament shall be soon dissolvd, or sit and do nothing; not sufferd to remedie the least greevance, or enact aught advantageous to the people. Next, the Councel of State shall not be chosen by the Parlament, but by the king, still his own creatures, courtiers and favorites; who will be sure in all thir counsels to set thir maister's grandure and absolute [71] power, in what they are able, far above the peoples libertie. I denie not but that ther may be such a king, who may regard the common good before his own, may have no vitious favorite, may hearken only to the wisest and incorruptest of his Parlament: but this rarely happens in a monarchie not elective; and it behoves not a wise nation to committ the summ of thir welbeing, the whole state of thir safetie to fortune. What need they; and how absurd would it be, when as they themselves to whom his chief vertue will be but to hearken, may with much better management and dispatch, with much more [72] commendation of thir own worth and magnanimitie govern without a maister. Can the folly be paralleld, to adore and be the slaves of a single person for doing that which it is ten thousand to one whether he can or will do, and we without him might do more easily, more effectually, more laudably our selves? Shall we never grow old anough to be wise to make seasonable use of gravest autorities, experiences, examples? Is it such an unspeakable joy to serve, such felicitie to wear a yoke? to clink our shackles, lockt on by pretended law of subjection more intolerable and hopeless to be ever shaken off, then [73] those which are knockt on by illegal injurie and violence? Aristotle, our chief instructer in the Universities, least this doctrine be thought Sectarian, as the royalist would have it thought, tels us in the third of his Politics, that certain men at first, for the matchless excellence of thir vertue above others, or som great public benifit, were created kings by the people; in small cities and territories, and in the scarcitie of others to be found like them: but when they abus'd thir power and governments grew larger, and the number of prudent men increasd, that then the people soon deposing thir tyrants, betook them, in [74] all civilest places, to the form of a free Commonwealth. And why should we thus disparage and prejudicate our own nation, as to fear a scarcitie of able and worthie men united in counsel to govern us, if we will but use diligence and impartiality to finde them out and chuse them, rather yoking our selves to a single person, the natural adversarie and oppressor of libertie, though good, yet far easier corruptible by the excess of his singular power and exaltation, or at best, not comparably sufficient to bear the weight of government, nor equally dispos'd to make us happie in the enjoyment of our libertie under him.

[75]

But admitt, that monarchie of it self may be convenient to som nations; yet to us who have thrown it out, receivd back again, it cannot but prove pernicious. For kings to com, never forgetting thir former ejection, will be sure to fortifie and arm themselves sufficiently for the future against all such attempts hereafter from the people: who shall be then so narrowly watchd and kep so low, that though they would never so fain and at the same rate of thir blood and treasure, they never shall be able to regain what they now have purchasd and may enjoy, or to free themselves from any yoke impos'd [76] upon them: nor will they dare to go about it; utterly disheartn'd for the future, if these thir highest attempts prove unsuccesfull; which will be the triumph of all tyrants heerafter over any people that shall resist oppression; and thir song will then be, to others, how sped the rebellious English? to our posteritie, how sped the rebells your fathers? This is not my conjecture, but drawn from God's known denouncement against the gentilizing Israelites; who though they were governd in a Commouwealth of God's own ordaining, he only thir king, they his peculiar people, yet affecting rather to [77] resemble heathen, but pretending the misgovernment of Samuel's sons, no more a reason to dislike thir Commonwealth, then the violence of Eli's sons was imputable to that priesthood or religion, clamourd for a king. They had thir longing; but with this testimonie of God's wrath; ye shall cry out in that day because of your king whom ye shall have chosen, and the Lord will not hear you in that day. Us if he shall hear now, how much less will he hear when we cry heerafter, who once deliverd by him from a king, and not without wondrous acts of his providence, insensible and unworthie of those high mercies, [78] are returning precipitantly, if he withold us not, back to the captivitie from whence he freed us. Yet neither shall we obtain or buy at an easie rate this new guilded yoke which thus transports us: a new royal-revenue must be found, a new episcopal; for those are individual: both which being wholy dissipated or bought by privat persons or assign'd for service don, and especially to the Armie, cannot be recoverd without a general detriment and confusion to mens estates, or a heavie imposition on all mens purses; benifit to none, but to the worst and ignoblest sort of men, whose hope is to be either the ministers [79] of court riot and excess, or the gainers by it: But not to speak more of losses and extraordinarie levies on our estates, what will then be the revenges and offences rememberd and returnd, not only by the chief person, but by all his adherents; accounts and reparations that will be requir'd, suites, incitements, inquities, discoveries, complaints, informations, who knows against whom or how many, though perhaps neuters, if not to utmost infliction, yet to imprisonment, fines, banishment, or molestation; if not these, yet disfavor, discountnance, disregard and contempt on all but [80] the known royalist or whom he favors, will be plenteous: nor let the new royaliz'd presbyterians perswade themselves that thir old doings, though now recanted, will be forgotten; what ever conditions be contriv'd or trusted on. Will they not beleeve this; nor remember the pacification, how it was kept to the Scots; how other solemn promises many a time to us? Let them but now read the diabolical forerunning libells, the faces, the gestures that now appeer foremost and briskest in all public places; as the harbingers of those that are in expectation to raign over us; let them but hear the insolencies, the menaces, [81] the insultings of our newly animated common enemies crept lately out of thir holes, thir hell, I might say, by the language of thir infernal pamphlets, the spue of every drunkard, every ribald; nameless, yet not for want of licence, but for very shame of thir own vile persons, not daring to name themselves, while they traduce others by name; and give us to foresee that they intend to second thir wicked words, if ever they have power, with more wicked deeds. Let our zealous backsliders forethink now with themselves, show thir necks yok'd with these tigers of Bacchus, these new [82] fanatics of not the preaching but the sweating-tub, inspir'd with nothing holier then the Venereal pox, can draw one way under monarchie to the establishing of church discipline with these new-disgorg'd atheismes: yet shall they not have the honor to yoke with these, but shall be yok'd under them; these shall plow on their backs. And do they among them who are so forward to bring in the single person, think to be by him trusted or long regarded? So trusted they shall be and so regarded, as by kings are wont reconcil'd enemies; neglected and soon after discarded, if not prosecuted for [83] old traytors; the first inciters, beginners, and more then to the third part actors of all that followd; it will be found also, that there must be then as necessarily as now (for the contrarie part will be still feard) a standing armie; which for certain shall not be this, but of the fiercest Cavaliers, of no less expence, and perhaps again under Rupert: but let this armie be sure they shall be soon disbanded, and likeliest without arrear or pay; and being disbanded, not be sure but they may as soon be questiond for being in arms against thir king: the same let them fear, who have contributed monie; [84] which will amount to no small number that must then take thir turn to be made delinquents and compounders. They who past reason and recoverie are devoted to kingship, perhaps will answer, that a greater part by far of the Nation will have it so; the rest therefor must yield. Not so much to convince these, which I little hope, as to confirm them who yield not, I reply; that this greatest part have both in reason and the trial of just battel, lost the right of their election what the government shall be: of them who have not lost that right, whether they for kingship be the greater number, [85] who can certainly determin? Suppose they be; yet of freedom they partake all alike, one main end of government: which if the greater part value, not, but will degeneratly forgoe, is it just or reasonable, that most voices against the the main end of government should enslave the less number that would be free? More just it is doubtless, if it com to force, that a less number compell a greater to retain, which can be no wrong to them, thir libertie, then that a greater number for the pleasure of thir baseness, compell a less most injuriously to be thir fellow slaves. They who seek nothing but thir own just libertie, have [86] alwaies right to winn it and to keep it, when ever they have power, be the voices never so numerous that oppose it. And how much we above others are concernd to defend it from kingship, and from them who in pursuance therof so perniciously would betray us and themselves to most certain miserie and thraldom, will be needless to repeat.

Having thus far shewn with what ease we may now obtain a free Commonwealth, and by it with as much ease all the freedom, peace, justice, plentie that we can desire, on the other side the difficulties, troubles, uncertainties, nay rather impossibilities to enjoy these [87] things constantly under a monarch, I will now proceed to shew more particularly wherin our freedom and flourishing condition will be more ample and secure to us under a free Commonwealth then under kingship.

The whole freedom of man consists either in spiritual or civil libertie. As for spiritual, who can be at rest, who can enjoy any thing in this world with contentment, who hath not libertie to serve God and to save his own soul, according to the best light which God hath planted in him to that purpose, by the reading of his reveal'd will and the guidance of his [88] holy spirit? That this is best pleasing to God, and that the whole Protestant Church allows no supream judge or rule in matters of religion, but the scriptures, and these to be interpreted by the the scriptures themselves, which necessarily inferrs liberty of conscience, I have heretofore prov'd at large in another treatise, and might, yet furder by the public declarations, confessions and admonitions of whole churches and states, obvious in all historie since the Reformation.

This liberty of conscience which above all other things ought to be to all men dearest and most precious, no government more inclinable [89] not to favor only but to protect, then a free Commonwealth; as being most magnanimous, most fearless and confident of its own fair proceedings. Wheras kingship, though looking big, yet indeed most pusillanimous, full of fears, full of jealousies, startl'd at every ombrage, as it hath bin observd of old to have ever suspected most and mistrusted them who were in most esteem for vertue and generositie of minde, so it is now known to have most in doubt and suspicion them who are most reputed to be religious. Queen Elizabeth though her self accounted so good a Protestant, so moderate, so [90] confident of her Subjects love would never give way so much as to Presbyterian rereformation in this land, though once and again besought, as Camden relates, but imprisond and persecuted the very proposers therof; alleaging it as her minde & maxim unalterable, that such reformation would diminish regal autoritie. What liberty of conscience can we then expect of others, far wors principl'd from the cradle, traind up and governd by Popish and Spanish counsels, and on such depending hitherto for subsistence? Especially what can this last Parlament expect, who having reviv'd lately and [91] publishd the covnant, have reingag'd themselves, never to readmitt Episcopacie: which no son of Charls returning, but will most certainly bring back with him, if he regard the last and strictest charge of his father, to persevere in not the doctrin only, but government of the church of England; not to neglect the speedie and effectual suppressing of errors and schisms; among which he accounted Presbyterie one of the chief: or if notwithstanding that charge of his father, he submitt to the covnant, how will he keep faith to us with disobedience to him; or regard that faith given, which must [92] be founded on the breach of that last and solemnest paternal charge, and the reluctance, I may say the antipathie which is in all kings against Presbyterian and Independent discipline? for they hear the gospel speaking much of libertie; a word which monarchie and her bishops both fear and hate, but a free Commonwealth both favors and promotes; and not the word only, but the thing it self. But let our governors beware in time▪ least thir hard measure to libertie of conscience be found the rock wheron they ship wrack themselves as others have now don before them in the cours wherin God was directing [93] thir stearage to a free Commonwealth, and the abandoning of all those whom they call sectaries, for the detected falshood and ambition of som, be a wilfull rejection of thir own chief strength and interest in the freedom of all Protestant religion, under what abusive name soever calumniated.

The other part of our freedom consists in the civil rights and advancements of every person according to his merit: the enjoyment of those never more certain, and the access to these never more open, then in a free Commonwealth. Both which in my opinion may be best and soonest obtaind, if [94] every countie in the land were made a kinde of subordinate Commonaltie or Commonwealth, and one chief town or more, according as the shire is in circuit, made cities, if they be not so call'd alreadie; where the nobilitie and chief gentry from a proportionable compas of territorie annexd to each citie, may build, houses or palaces, befitting thir qualitie, may bear part in the government, make thir own judicial laws, or use these that are, and execute them by thir own elected judicatures and judges without appeal, in all things of civil government between man and man. so they shall have justice in thir own [95] hands, law executed fully and finally in thir own counties and precincts, long wishd, and spoken of, but never yet obtaind; they shall have none then to blame but themselves, if it be not well administerd; and fewer laws to expect or fear from the supreme autoritie; or to those that shall be made, of any great concernment to public libertie, they may without much trouble in these commonalties or in more general assemblies call'd to thir cities from the whole territorie on such occasion, declare and publish thir assent or dissent by deputies within a time limited sent to the Grand Councel: yet so as this thir [96] judgment declar'd shal submitt to the greater number of other counties or commonalties, and not avail them to any exemption of themselves, or refusal of agreement with the rest, as it may in any of the United Provinces, being sovran within it self, oft times to the great disadvantage of that union. In these imploiments they may much better then they do now, exercise and fit themselves, till thir lot fall to be chosen into the Grand Councel, according as thir worth and merit shall be taken notice of by the people. As for controversies that shall happen between men of several counties, they may repair, [97] as they do now, to the capital citie, or any other more commodious, indifferent place and equal judges. And this I finde to have bin practisd in the old Athenian Commonwealth, reputed the first and ancientest place of civilitie in all Greece; that they had in thir several cities, a peculiar; in Athens, a common government; and thir right, as it befell them, to the administration of both. They should have heer also schools and academies at thir own choice, wherin thir children may be bred up in thir own sight to all learning and noble education not in grammar only, but in all liberal ars and exercises. [98] This would soon spread much more knowledge and civilitie, yea religion through all parts of the land, by communicating the natural heat of government and culture more distributively to all extreme parts, which now lie numm and neglected, would soon make the whole nation more industrious, more ingenuous at home, more potent, more honorable abroad. To this a free Commonwealth will easily assent; (nay the Parlament hath had alreadie som such thing in designe) for of all governments a Commonwealth aims most to make the people flourishing, vertuous, noble and high spirited. [99] Monarchs will never permitt: whose aim is to make the people, wealthie indeed perhaps and well fleec't, for thir own shearing and the supplie of regal prodigalitie; but otherwise softest, basest, vitiousest, servilest, easiest to be kept under; and not only in fleece, but in minde also sheepishest; and will have all the benches of judicature annexd to the throne, as a gift of royal grace that we have justice don us; when as nothing can be more essential to the freedom of a people, then to have the administration of justice and all public ornaments in thir own election and within thir own bounds, without [100] long travelling or depending on remote places to obtain thir right or any civil accomplishment; so it be not supreme, but subordinate to the general power and union of the whole Republic. In which happy firmness as in the particular above mentiond, we shall also far exceed the United Provinces, by having, not as they (to the retarding and distracting oft times of thir counsels or urgentest occasions) many Sovranties united in one Commonwealth, but many Commonwealths under one united and entrusted Sovrantie. And when we have our forces by sea and land, either of a faithful Armie [101] or a setl'd Militia, in our own hands to the firm establishing of a free Commonwealth, publick accounts under our own inspection, general laws and taxes with thir causes in our own domestic suffrages, judicial laws, offices and ornaments at home in our own ordering and administration, all distinction of lords and commoners, that may any way divide or sever the publick interest, remov'd, what can a perpetual senat have then wherin to grow corrupt, wherin to encroach upon us or usurp; or if they do, wherin to be formidable? Yet if all this avail not to remove the fear or envie of a perpetual [102] sitting, it may be easilie provided, to change a third part of them yearly or every two or three years, as was above mentiond; or that it be at those times in the peoples choice, whether they will change them, or renew thir power, as they shall finde cause.

I have no more to say at present: few words will save us, well considerd; few and easie things, now seasonably don. But if the people be so affected, as to prostitute religion and libertie to the vain and groundless apprehension, that nothing but kingship can restore trade, not remembring the frequent plagues and pestilences [103] that then wasted this citie, such as through God's mercie we never have felt since, and that trade flourishes no where more then in the free Commonwealths of Italie, Germanie, and the Low-Countries before thir eyes at this day, yet if trade be grown so craving and importunate through the profuse living of tradesmen, that nothing can support it, but the luxurious expences of a nation upon trifles or superfluities, so as if the people generally should betake themselves to frugalitie, it might prove a dangerous matter, least tradesmen should mutinie for want of trading, and that therefor we must forgoe & set [104] to sale religion, libertie, honor, safetie, all concernments Divine or human to keep up trading, if lastly, after all this light among us, the same reason shall pass for current to put our necks again under kingship, as was made use of by the Jews to returne back to Egypt and to the worship of thir idol queen, because they falsly imagind that they then livd in more plentie and prosperitie, our condition is not sound but rotten, both in religion and all civil prudence; and will bring us soon, the way we are marching, to those calamities which attend alwaies and unavoidably on luxurie, all national judgments [105] under forein or domestic slaverie: so far we shall be from mending our condition by monarchizing our government, whatever new conceit now possesses us. However with all hazard I have ventur'd what I thought my duty to speak in season, and to forewarne my countrey in time: wherin I doubt not but ther be many wise men in all places and degrees, but am sorrie the effects of wisdom are so little seen among us. Many circumstances and particulars I could have added in those things wherof I have spoken; but a few main matters now put speedily in execution, will suffice to recover us, and set all right: and ther [106] will want at no time who are good at circumstances; but men who set thir mindes on main matters and sufficiently urge them, in these most difficult times I finde not many. What I have spoken, is the language of that which is not call'd amiss the good Old Cause: if it seem strange to any, it will not seem more strange, I hope, then convincing to backsliders. Thus much I should perhaps have said though I were sure I should have spoken only to trees and stones; and had none to cry to, but with the Prophet, O earth, earth, earth! to tell the very soil it self, what her perverse inhabitants are deaf [107] to. Nay though what I have spoke, should happ'n (which Thou suffer not, who didst create mankinde free; nor Thou next, who didst redeem us from being servants of men!) to be the last words of our expiring libertie. But I trust I shall have spoken perswasion to abundance of sensible and ingenuous men: to som perhaps whom God may raise of these stones to become children of reviving libertie; and may reclaim, though they seem now chusing them a captain back for Egypt, to bethink themselves a little and consider whether they are rushing; to exhort this torrent also of the people, not to be [108] so impetuos, but to keep thir due channell; and at length recovering and uniting thir better resolutions, now that they see alreadie how open and unbounded the insolence and rage is of our common enemies, to stay these ruinous proceedings; justly and timely fearing to what a precipice of destruction the deluge of this epidemic madness would hurrie us through the general defection of a misguided and abus'd multitude.