John Lilburne, The resolved mans Resolution, to maintain with the last drop of his heart blood, his civill Liberties and freedomes (30 April 1647).

Note: This is part of the Leveller Collection of Tracts and Pamphlets.

Editor’s Introduction

(Placeholder: Text will be added later.)

Bibliographical Information

ID Number

T.95 [1647.04.30] John Lilburne, The resolved mans Resolution, to maintain with the last drop of his heart blood, his civill Liberties and freedomes (30 April 1647)

Full title

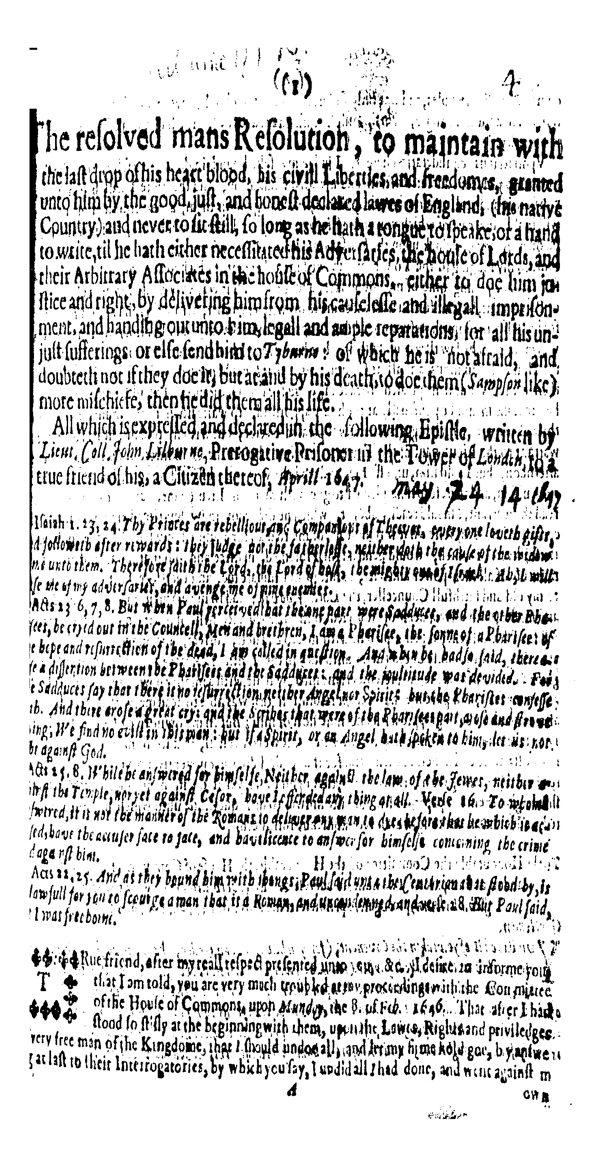

John Lilburne, The resolved mans Resolution, to maintain with the last drop of his heart blood, his civill Liberties and freedomes, granted unto him by the good, just, and honest declared lawes of England, (his native Country) and never to sit still, so long as he hath a tongue to speake, or a hand to write, til he hath either necessitated his Adversaries, the house of Lords, and their Arbitrary Associates in the house of Commons, either to doe him justice and right, by delivering him from his causelesse and illegall imprisonment, and out unto him, legall and ample reparations, for all his unjust sufferings or else send him to Tyburne: of which he is not afraid, and doubteth not if they doe it, but at and by his death, to doe them (Sampson like) more mischief, then he did them all his life. All which is expressed and declared in the following Epistle, written by Lieut. Coll. John Lilburne, Prerogative Prisoner in the Tower of London, to a true friend of his, a Citizen thereof, Aprill 1647.

Isaiah 1.23, 24. Thy Princes are rebellious and Companions of Thieves, every one loveth gifts, and followeth after rewards: they Judge not the fatherlesse, neither doth the cause of the widow come unto them. Therefore saith the Lord, the Lord of host, the mighty one of Israel, Abel will use me of my adversaries, and avenge me of mine enemies.

Acts 13 6, 7, 8. But when Paul perceived that the one part were Sadduces, and the other Pharasees, be cryed out in the Councell, Men and brethren, I am a Pharisee, the sonne of a Pharisee: of [...]e hope and resurrection of the dead, I am called in question. And when be had so said, there arosee a dissertion between the Pharisees and the Sadducees: and the multitude was devided. For the Sadduces say that there is no resurrection neither Angel nor Spirit: but, the Pharisees confesse both. And there arose a great cry: and the Scribes that were of the Pharisees part, arose and [...] saying; We find no evill in this man: but if a Spirit, or an Angel hath spoken to him, let us not [...] against God.

Acts 15.8. While he answered for himselfe, Neither against the law of the Jewes, neither against the Temple, nor yet against Caesor, have I offended any thing at all. Verse 16. To whom [...] answered, it is not the manner of the Romans to deliver any man to die before that he which is accused, have the accuser face to face, and have licence to answer for himselfe concerning the crime against him.

Acts 22.25. And as they bound him with things, Paul said unto the Centurion that stood by, is it lawfull for you to scourge a man that is a Roman, and be condemned, and verse 28. But Paul said, [...] was free borne.

This tract contains the following parts:

- The resolved mans Resolution

- To the Honourable Committee of the Honourable House of Commons, for suppressing of scandalous Pamphlets. The humble Addresses of Lieut. Col. John Lilburne, Prerogative Prisoner in the Tower of London. Feb. 8. 1646.

- The proceedings of Mrs. Walter in the Parliament with the House of LORDS

- A note of all the Swords, Belts, and Holsters for Pistols, and Bandeliers That Major Liburne caused to be brought into the Magazine at Boston.

Estimated date of publication

30 April 1647.

Thomason Tracts Catalog information

TT1, p. 506; Thomason E. 387. (4.)

Text of Pamphlet

Isaiah 1. 23, 24. Thy Princes are rebellious, and Companions of Thieves, every one loveth gifts, and followith after rewards: they Judge not the fatherlesse, neither doth the cause of the widow come unto them. Therefore saith the Lord, the Lord of hast, the mighty one of Israel, Abel will use me of my adversaries, and avenge me of nine enemies.

Acts 13 6, 7, 8. But when Paul rerceived that the one part were Sadduces, and the other Pharasees he cryed out in the Councell, Men and brethren, I am a Pharisee, the sonne of a Pharisee: of little hope and resurrection of the dead, I am called in question. And when he had so said, there arose a dissertion between the Pharisees and the Sadduces: and the multitude was devided.For the Sadduces say that there it no resurrection neither Angel nor Spirite but the Pharisees confesse both. And there arose a great cry: and the Scribes that were of the Pharisees part, arose and strove saying; We find no evill in this man: but if a Spirit, or an Angel hath spoken to him, let us not fight against God.

Acts 15. 8. While he answered for himselfe, Neither against the law of the Jewes, neither against the Temple, nor yet against Caesar, have I offerded any thing at all. Verse 16. To whom it was answered, it is not the manner of the Romans to deliver any man to dye before that he which is accused, have the accuser face to face, and have licence to answer for himselfe concerning the crime against him.

Acts 22, 25. And as they bound him with thongs, Paul said unto the the Centurian that stood by, is it lawfull for you to scourge a man that is a Roman, and be condemned, and verse 28. But Paul said, that I was freebome.

TRue friend, after my reall respect presented unto [Editor: illegible word] &c. I desire to informe you that I am told, you are very much troubled at the proceedings with the Committee of the House of Commons, upon Munday, the 8. of Feb. 1646. That after I had stood so stifly at the beginning with them, upon the Lawes, Rights and priviledges every free man of the Kingdome, that I should undoe all, and let my firme hold goe, by answering at last to their Interrogatories, by which you say, I undid all I had done, and went against my owne declared principles, and not only so but by owning my book, have exposed my selfe to a great deale of hazard and danger, which I might easily have avoyded, if I had not answered their Interogatory.

Vpon serious consideration hereof, I judge my selfe bound in duty to my selfe, to write these lines unto you, for your satisfaction, and my own vindication, and therefore J shall begin to give you so true and reall a Narrative of my whole proceedings with them, as the utmost of my memory will inable me, part of which you your selfe were an eye and eare witnesse unto, and it was in this manner. About 9. o clock upon the foresaid Munday, Lewis a servant to the Sergeant at Armes came to my lodging in the Tower, and shewed me a Warrant he had to take my wife into safe custody, for dispersing some of my last bookes, and I told him it was very hard, for any Committee of Parliament, to send forth a warrant to make my wife a Prisoner, before they had heard her speake for her selfe, or so much as summoned her to appeare before them, and I plainly told him it was more then by law they could justifie, but however, I bore so much honourable respect unto the House of Commons, and all its Committees, that I would not perswade my wife to contempt their warrants, but if he pleased to take my word for her appearance, I would ingage my life for her, that she should be punctually at the houre appointed, to waite upon the Committee to know their pleasure: which ingagement he was pleased to take, but with all told me, he had brought a warrant to the Lieutenant of the Tower, to carrie me before the Committee at two a clock in the afternoon, but I told him, unlesse I see and read the warrant, I should not goe, but by force and compulsion, and therefore if he pleased to goe with me to the Lieutenant, and get him to let me read the warrant, I should readily obey it, which he did accordingly, but time being very short, I considered with my selfe what was most fit for me to doe, for I assured my selfe I was to goe before those, divers of which, would bend all their insensed mallice and indignation against me, and make use of all their power and wits, to intrap and insnare me, and therefore, I lifted up my soule to my old and faithfull Counceller, the Lord Jehovah and in my ejaculations, pressed my Lord and master, with a great deale of grounded confidence and cleernesse of spirit, to declare and manifest his faithfullnesse, in being present with me, to counsell, direct, incourage and stand by me, according to his promise of old (made unto me) in the tenth of Matthew, and to his praise and glory I desire to speake it, he presently came into my soule with a mighty power, and raised me high above my selfe, and gave me that present resolution that was able to lead me, with a great deale of assured confidence to grapple with an whole host of men; But in my owne spirit I was led presently to take care, to doe something for my wife as the weaker vessell, that so she might not be to seek in case she were called before them, and for that end, I drew her presently up a few lines, which I read unto her, and gave her instructions, that upon the very first question they should aske her, she should give them her paper, as her absolute answer to their question: unto which she readily assented and set her name to it, which verbatum thus followeth.

To the Honourable the Committee of the Honourable, the House of Commons, for suppressing of scandalous Pamphlets. The humble addresses of Elizabeth Lilburne, wife to Lieut. Col. John Lilburn, prerogative prisoner in the tower of London. Feb. 8. 1646.

YOu have all of you taken the Covenant, (for you have made an Order, that no man shall sit in your House, that will not take it) where you have sworn to maintain the fundamentall Lawes of the Kingdome, and for you to examine me upon Interrogatories, is contrary to the fundamentall Law of the Kingdome, (and for me to answer to them, is to be traiterous to my owne liberty) or for you to proceed by any other rules to punish me, for any reall or pretended crime, but what is declared by the Law, is unjust and unrighteous, and therefore I humbly intreat this honourable Committee, seriously to read and consider the Statute of the 42. of Edward the third, Chapter 3. which thus followeth. “Item, At the request of the Commons by their Petitions put forth in this Parliament, to eschew the mischiefes and dammage done to divers of his Commons, by false accusers which often times have made their accusation more for revenge, and for the benefit and for the profit of the King, or of his people, which accused persons, some have been taken[Editor: illegible word] which the Parliament is. and sometime caused to come before the Kings Counsell, by writ otherwise upon grievious paine against the Law: It is assented and accorded, for the good governance of the Commons, that no man be put to answer without presentment before Iustices, or matter of record, or by due processe and writ originall according to the old Law of the land, and if any thing from henceforth be done to the contrary, it shall be void in the Law, and holden for errour. And sutable to this is the 29. chap of Magna Charta, and the 5. E. 3. 9. and 25. E. 3. 4. and 18. E. 3. 3. 37. E. 3. 18. which are all and every of them confirmed by the Petition of Right, made in the third yeare of the present King, which expresly saith. “No man ought to be adjudged, but by the lawes established in the Realm, and not otherwise, which Petition of Right, you your selves have in every point confirmed, as appeares by the Statute that abolisheth the Star Chamber, and by the Statute that abolisheth Ship money, and you your selves with your hands lifted up to the most high God, have often sworne, vowed, protested and declared, you will maintaine preserve and defend, the fundamentall lawes of the land, and square your actions accordingly, and imprecate the wrath and vengeance of the great God of Heaven and Earth to fall upon you, when you [Editor: illegible word] to performe what there you sweare to, and declare, and therefore Gentlemen, what thoughts soever of displeasure you have towards me, I hope you will be so tender of your own honours and reputations, that you will not in the least indeavour to deale with me contrary to the true intent and meaning of the forementioned lawes, but if you should, I cannot stoop unto any tryal that is contrary to the pattern of the forementioned honest, just and good lawes, and if you please to let me [Editor: illegible word] the benefit of them, I shall be ready to joyne issue with you, whensoever you please, and legally to answer whatsoever I have said and done and so I humbly take my leave of your honours, and rest.

And having finished hers, and taken care to get a copy of it, I begun to thinke what to doe for my selfe, and being very confidently perswaded, that they would shew me my book, and aske me if I would owne it for mine, because this was their method the last yeare with me, as you may fully read in a printed Epistle I writ to you last yeare, when I was a prisoner under the sergeant at Arms of the house of Commons, which Epistle is dated July 14. 1645.

And in my answer to William Prinns notorious lyes and falshoods, *called Innocency and truth justified, pag. 6. 13, 14. 15. 16.

And therefore it fell to my pen and ink, but before I had writ a quarter of that I intended, my selfe to give into the Committee, my keeper came, and told me it was past one a clock, and therefore full time for us to be gone, being we were to be there by two, and in regard it was so very cold, we marched all the way by land, and comming to the outward Court of wards before the Committee sate I fell to perfect what I had begun, and as I was at worke, out came to me a Citizen and told me there was a young Gentleman in a fur jacket who looked something a squire, pressed with a great deale of choler and indignation, that I might be imediately called in to answer for my notorious crime, for writing the Oppressed mans appressions declared, which I say is a book of truth and honesty, and just as I had done, I was called in before the Committee, where I found (as I conceived them) a great many of the little better then theevish catch-poule Stationers, whose trade it is for divers of them illegally and little better then felloniously, to breake open honest mens houses and the Theeves and Rogues, carry away their true and proper goods,* and a very large company of Parliament men, as ever I see at a Committee to my remembrance before, and looking well about me, the most of them were to me men of new faces, and one of them appeared to me, to be one of Pryns infants or Minors, not above 18. yeares old as I conceived, but amongst them all I see not the face of one of my old acquaintance. And after I had rendered my respects to Mr. Corbet, the Chair-man thereof, he took a little book and read the title of it, The Oppressed mans Oppressions declared, &c. and also turned to the last end of it, and read the conclusion, which was subscribed Iohn Lilburn semper idem, and told me he was commanded by the Committee, to ask me this question, whether I would own that book for mine or no? unto which I answered. Sir, with the favour of this honourable Committee, I shall humbly desire to speake a few words, well said Mr. Corbet, answer to the question.

Sir, said I, if you please to give me leave to speak, well and good, if not, if you please to command me silence I shall obey you. Saith he the question is but short therefore answer to it, either I or no, Sir said I, I am now past a schole boy, and have long since learned to say my A, B, C, after my master, but have now attained to a more ripe understanding, so that I am now able to speak without being dictated unto what I should say, and therefore if you please to give me leave to speak my own words in my owne manner and forme, well and good, if not, I have no more to say unto you: Sir saith he, the question is but short, therefore you are commanded to give a possitive answer to it, unto which I replyed, Sir if you will not let me speak my owne words, in my owne way, I will neither tell you, whether I will owne it or disavow it, and with that he took his pen and writ part of what I said, and read it to me. Sir said I, what you have writ, is not full what I said, and therefore if you please to give me pen, inke and paper, I shall write what I said my selfe, and set my hand unto it, which he refused, but divers of the Parliament men, pressed him to keep me to the question. Vnto which I said, Gentlemen, if you please to give me leave to speak, well and good, if not lets come to an issue and command me out of doores, for I will not answer you till I have free liberty to speak, upon which one or two of the Committee said, let him speak, but saith Mr. Corbet, if after you have liberty for to speake, will you returne a possitive answer to the question? yea, Sir said I, that I will, well then speak said he speak. Sir said I what I have to say, is in the first place; in reference to the house of Commons, for apprehending with my selfe, that my carriage and speeches this day before the Committee, may be represented to the honourable House of Commons, to my detriment and dammage, I therefore judge it convenient for me to fortifie my self as wel as I can, and therfore I desire humbly to declare, that I own the constitution of the honorable house of Commons, as the greatest, best, and legallest interest, that the Commons of England have for the preservation of their Rights and Liberties, and I doe not only owne their constitution but also I honour their authority and power, and the power and authority of all Committees, legally deriving their power therefrom, and shall readily and cheerfully, yeeld obedience to all their commands, provided they act according to the rules of justice, and to the good knowne lawes of the hand, but not otherwise.

And in the second place, I desire to speake a few words of my thoughts of this Committee, but I was exceedingly interrupted, not only by the Chairman, but also by other Members of the House, and very much pressed to give an answer to the question, which made me say, Mr. Corbet, if you please to let me goe on in my own way, well and good, if not I have no more to say to you, for I came not hither of my owne head, to make a complaint unto you of my own, but I was sent for by you, (as I conceive) in a criminall way, to answer something before you, in which regard, it behoves me to stand upon the best guard that either law, reason, or judgement can furnish me with, and being that I apprehend, I am so much concerned in my present appearance before you, it exceeding much concernes me, to be very considerate and wise, in managing my business before you, therefore if you please, let me goe on to speak out what I have to say, and I thinke in conclusion, I shall give you as possitive an answer to the question as you desire.

So up stepped a welth Gentleman, one Mr. Harbert, as I remember his name, & desired Mr. Corbet to let me speak on, for saith he, you hear him promise to give you a possitive answer to your question.

Well then saith Mr Corbet, but will you as soone as you have spoken give a possitive answer to the question? Yea, Sir said I, (and clapt my hand upon my breast) upon my credit and reputation will I, then goe one saith he.

Well then Sir said I, two words concerning this Committee, and that at present I have to say is this, that I looke upon this Committee, as a branch deriving its power from the House of Commons, and therefore honour it, and I looke upon you in the capacitie you sit here, as a Court of justice, and I conceive you look upon your selves in the very selfe same capacity, but in case you do not, I have no more to say unto you, neither if ye be not a Court of Justice, doe I conceive have you in law, any power at all to examine me. But none of them replying upon me, made me take it for granted, they took themselves for a Court of justice, and therefore I went one and said, if you so doe, that is own your selves for a Court of justice, then I desire you to deale with me as it doth become a Court of Justice, and as by law you are bound, which is to let me have a free, open, and publique hearing. For Gentlemen, you have all of you taken the Covenant, in which you have lifted up your hands to the most high God, and sworne to maintaine the lawes of the Land. And it is the law of the land, that all Courts of Justice ever have been, are, and ought to be held openly and publiquely, (not close like a Cabinet Counsell) from whence no Auditers are, or ought to be excluded,* and therefore as you would not give cause to me to Judge you a company of forswarne men, I desire you to command your doore to be opened that so all the people, that have a mind to heare and see you, and beare witnesse, that you proceed with justice and righteousnesse, may without check or comptrole, have free accesse to behold you, they behaving themselves like civill men. But here arose a mighty stir by some Parliament men, who declared, fiery indignation in their very countenances against me, but especially, a Gentleman that sate on the left hand of the forementioned Gentleman in the fur jacket, who pressed vehemently to hold me close to the question, and keep to their Committee proceedings, but truly I conceived the Gentleman to be but a very young Parliament man, and one that neither had read, nor understood the lawes of England, and therefore Sir said I to him, to stop your mouth, I tell you, I blesse God, I am not now before a Spanish Inquisition, but a Committee of an English Parliament, that have sworne to maintaine and preserve the lawes of the Kingdome, and therefore Mr. Corbet, I know you are a Lawyer, and know and understand the lawes of the Kingdome, and I appeale to your very conscience, whether my desire of an open and publique hearing, be any otherwise then according to Law, sure I am Sir, it was the constant practise of this very Parliament at the beginning thereof that in all their Committees whatever, where they sat to heare and examine criminall causes, that they alwayes sate open, and I speake it out of my own knowledge, that you were then angry with any man amongst your selves, that did presse or move that you might sit in a cabinit and clandestine way, and truly Mr. Corbet, I thinke this Committee would take it very ill at my hands, if I should affirm you are more unjust & unrighteous now, then you were at the beginning for I my self, had about halfe a score publique hearings at a Committee about my Star-Chamber businesse, and therefore being now before you, upon a businesse in my thoughts, of as much concernment to me as that was: I beseech you, let me have the same fare and just play now, that then I had, and give not [Editor: illegible word] just cause to me and others, to say your actions and proceedings are unrighteous and unjust and therefore you sit in holes and corners, and dare not abide the publique view of your actions which will be too clear a demonstration to all the world, that your deeds are evill, Iohn 3. 10, 21. Well Sir said Mr. Corbet here is company enough to heare you, therefore you may goe on, true it is Sir, here is enough of my enemies but I see never a one of my friends: therefore if you please to command the doore to be not wide open, well and good, if not I will not say one word more unto you, so I was commanded to withdraw, which I did. And being called in againe, Mr. Corbet told me, he was commanded by the Committee to aske me the question againe, whether I would owne the book or no? But I told him I was the same man now, that I was when I withdrew, and therefore I said unlesse they would command and order the doore to be openned, that every man that had a mind to come in, might come in without let or molestation, I would returne as answer it all.

With that one of the Gentlemen said, the doore is open, and so it was, and whether they had given a private Order to the doore keeper so to doe I know not. Well Mr. Corbet said I, it is not an accidentall or casuall openning of the doore will serve my turn, but an orderly and legall openning of it, as that which ought to be done of right and justice, and therefore Mr. Corbet, it you please as you are Chair-man of this Committee, to command the doore to be set and stand wide open, I shall goe on, if not, I shall be silent.

Well then doore keeper (saith he) set open the doore, now Sir said I, with your favour, I shall expresse my selfe a little further to this Committee, whereupon I openned a written paper I had in my hand, and began to looke upon it, but Mr. Corbet told me, the question was so short that it needed no long answer to it, and therefore I might spare the labour of using my paper. Good Sir [Editor: illegible word] I beseech you, afford me but so much priviledge as you doe every mercenary Lawyer, that pleads his Clients cause for a fee before you, to whom you never deny the benefit of pleading by also help of his notes or papers, and I know no reason why I should be denyed the same priviledge in my own case, and therefore I humbly intreat you, to afford me the benefit of looking upon my own paper, but said Mr. Corbet, how came you to write these paper? did you know before hand what we would say to you? O Sir said I, you may remember I was severall times before you in this manner the last year, and I very well remember the method of your illegall proceedings with me then,* and being by you summoned now again to come before you, I did very strongly conjecture, that you would tread in the method of your old steps of Interrogatories, and therefore I judged it but wisedome and foresight in me, to fit my selfe for you, and accordingly I have writ down the substance of what I haue to say to you in this paper, saith Mr. Corbet, give me the paper and we will consider of it, no Sir said I, I beseech you excuse me, for you have been so hasty with me, that I had no time to copy it over, and I doe not love to part with my papers in this nature, without keeping copies of them, but if you please to let me goe on, either to read it to you, or to say it by heart to you, now and then looking upon it I shall very willingly give you a true copy of it under my hand. I pray you Mr. Corbet, said the aforementioned, Mr. Harbert let him goe on, which he assented unto, and I purposely past over the preamble of it, having already as I told them touched upon it, and begun in that place, where mention is made of the Star-Chamber. With which Sir William Strickland interrupted me, and said Mr. Corbet, I doe not like nor approve of raiking up these things, much lesse in comparing us to the Star Chamber, therefore I wish Mr. Lilburne would be perswaded to for beare these dishonourable expressions, for they are not handsome. Good Mr. Corbet I beseech you heare me a little, for under Sir Williams favour, I doe not compare you to the Star Chamber, but if you would not be compared unto it, then you must not walk in its unjust, and illegall ways, but Sir said I, for Sir Williams further satisfaction, I desire to let him know, I doe honour the true and just power of the House of Commons, as much as himselfe, and have adventured my life and blood, for the preservation thereof, as cordially, really and heartily, in the singlenesse and uprightnesse of my soule, as any man that at this day sits within the Walls of that house, whatever he be, and I have still the same love and affections, to the just interest of that house, and the same zeale to maintaine it that ever I had, and it doth not in the least repent me of what J have formerly done or suffered for it, though I thinke by their late dealings with me, I have as true and grounded cause administred unto me by them, to repent as any man in England either hath or ever will & therefore Sir, under your favour, although I be very unwilling like a simple man, to part with my just & legal rights to this Committee, a branch of the Honourable House of Commons, it doth not in the least therefore follow, that I am disaffected or disrespective of the just interest & power of the House of Commons, but rather it doth follow, that I am the same man now that ever I was before & Sir under your favour I tell you, it is neither for the honour, interest nor benefit of the house of Commons, for any of its Committees, to swallow down or destroy, the publique interest and liberties of the people, the preservation of which, (by their owne Declarations*) being the principall end wherefore the people chuse and trusted them to sit where they doe, and therefore Sir, I pray you, let me goe on, which was granted, but before I could get through my paper, there was a great hurly burly amongst the Parliament men, being extreamly nettled at my paper which many of them expressed in their speeches to Mr. Corbet, and desired him to silence me in the way I then was in, and hold me to the question-Gentlemen said I this is very strange proceedings, that you will neither let let alone, nor let me speake. Be it knowne unto you, that I conceive J stand in need neither of mercy nor favour from you, but only what reason, Law and justice affords me, neither doe I crave any other priviledge at your hands, but what the Earle of Strafford injoyed from you, (although you your selves judged him the greatest of offenders) which was a free and uninterrupted liberty to speak for himselfe, in the best manner he could, and to make the best defence for himselfe, that possible all the wit and parts he had, would inable him to doe, and sure I am this is a priviledge due by law to every Mutherer, Rogue, & Theefe,* which I am sure the arrantest Villaine that is arraigned at Newgate Sessions (for the notorioust of crimes) injoyes this priviledge as his right by law, to speake his owne words, in his owne manner, for the best advantage of himselfe, to his own understanding, and it is very strange to me, that I who am a free man of England, and am not conscious to the committing of a crime against the Law, shall not be suffered by a committee of Parlament, that have solemnly sworne to maintaine the lawes, to injoy that legall priviledge to speak my owne word; in my owne manner, for my most advantage and best defence, that is [Editor: illegible word] nor legally, nor cannot be denyed, at any Assizes or Sessions, to the most capitall, bloody, and arrantist Rogue in England. Truly Gentlemen, I must plainly tell you, I never was convicted of any crime at all that did in the least disfranchise me of my hereditary and legall Rights and Liberties, nor ever was legally in the least made uncapable of injoying the utmost benefit and priviledge that the law of England will afford or hand out to any legall man of England, But have at your command, many times and often adventured my life and all that I had in the world, for the maintenance and preservation of the lawes and liberties of England, with as much uprightnesse of heart and as much man love, courage and resolution, as any member of the House of Commons what ever he be, and therefore I tell you before this Committee, or any power in England, what ever it be, shall rob me of my just exacted recompence of reward for all my labours, travels and hazards (which recompence of reward is the injoyment of the just priviledges and benefits of the good lawes of the Kingdome, I will spend my heart blood against you, yea, if I had a million of lives, I would sacrifice them all against you, and therefore seeing you have all of you solemnly lifted up your hands to the most high God: and sworne to maintaine the Lawes of the Kingdome, I desire you for your owne credits sake to deale with me so, as not to give me to just cause, to avouch it to your faces, you are a company of forsworne men, and so to publish & declare you to the whole Kingdome. VVith this Mr Wever, Burgesse for Stamford spoke, “Mr Corbet, I conceive such reproachfull and dishonourable expressions as Mr. Lilburn gives us to our faces, is not to be induced or suffered, and therefore I beseech you, let us be sensible of the honour due to our Authority, and the house whereof we are Members.

Good Mr. Corbet, I intreat you heare me, for J desire to let that Gentleman know; J am very confident I have not you said any thing that is dishonourable to the legall and just interest and power either of this Committee, or the house of Commons whereof you are Members, and Sir if I should, I conceive you are enough to beare witnesse against me, and I thinke you judge your selves sufficiently indowed with power to punish me if I should doe as that Gentleman pretends, I have done, and truly Mr. Corbet, J must againe aver it before you, that I am no contemner nor despiser of the just and legall authority of the house of Commons, neither doe I desire to affront or reproach this Committee, but I pray consider, I am but a man, and a prisoner under many provocations, and to be so rufly falne upon as I am, by halfe a dozen of you at a time, and interrupted in making my legall defence, and not suffered to speake my own words, is very hard and it is possible hereby, I may be provoked to heat, and in heat say that that is not convenient and fitting, the which if J should doe I hope you Mr. Corbet, have understanding enough to iudge, and to reprove me for it, and truly Sir upon your reproofe, if I can possibly apprehend and see I have done amisse I shall presently cry you peccavic.

But here abouts, my wise seeing Mr. Wever so furious upon me as he was, burst out with aloud voice & said, “I told thee often enough long since, that thou would serve the Parliament, and venter thy life so long for them, till they would hang thee for thy paines, and give thee Tyburn for thy recompence and I told thee besides, thou shouldst in conclusion find them a company of unjust, and untighteous judge’s, that more sought themselves, and their owne ends, then the publique good of the Kingdome, or any of those that faithfully adventured their lives therefore.

But J desired Mr. Corbet, to passe by what in the bitternesse of her heart being a woman she had said unto them, and desired him to let me conclude my paper, and then J would give him a possitive answer to their question, which was granted, and I read out my paper, the true copy of which at large thus followeth.

To the Honourable Committee of the Honourable House of Commons, for suppressing of scandalous Pamphlets.

The humble Addresses of Lieut. Col. John Lilburne, Prerogative Prisoner in the Tower of London. Feb. 8. 1646.

MAy it please this honourable Committee, this any I see and read a warrant under the hand of Mr. Miles Corbet, directed to the Lieutenant of the Tower, to bring me before your honours, sitting in the inner Courts of wards, at two a clock this present afternoon, but no cause wherefore is expressed in the warrant therefore in the first place, I desire and humbly entreat this honourable Committee, to take [Editor: illegible word] [Editor: illegible word] [Editor: illegible word] [Editor: illegible word] and [Editor: illegible word] the constitution, authority and power of the honourable house of commons, and looke upon it in its constitution, at the greatest and legall, best interest that the Commons of England both, and of all the Committees thereof, that legally and justly derive their power therefrom, and act according to the Law and just customes of Parliament, within their bounds, unto all whose commands so farre as the established law of England requires me, I shall yield all cheerfull and ready obedience, but having the last yeer very large experience of the arbitratry and illegall proceedings of some Committee or Committees of the House of Commons, and the Chair-man or Chair-men thereof, and fearing to meet with the like now againe, by way of prevention I am necessitated humbly to declare unto this honourable Committee, that in the dayes of the Star-Chamber, I was there sentenced for no other cause, but for refusing to answer to their interrogateries or questions, and upon the 4. of May, 1641. the honourable house of Commons, whereof you are Members upon the report of Mr. Francis Rouse made these ensuing Votes.

Resolved upon the question.

That the sentence of the Star Chamber given against John Lilburn is illegall and against the the liberty of the Subject, and also bloody, wicked, cruell, barberous and tyrannicall.

Resolved upon the question, that reparations ought to be given to Mr. Lilburn for his imprisonment, sufferings and losses, sustained by that illegall sentence.

Here is your own iust and legall Votes in my own case, to condemne as illegall and uniust; all inquisition proceedings upon selfe accusing interrogatories, and your Votes are sutable to the ancient and fundamentall lawes of this land, as appeares by the 29. chap. of Magna Charta, and the 5. E. 3. 9. and 25. E. 3. 4. and 28, E. 3. 3. and 37. E. 3. 18. and 42. E. 3. 3. the words of which last cited Statute thus followeth.

“Item at the request of the Commons by their Petitions, put forth in this Parliament, to escew the mischiefes and dammages done to divers of his Commons by false accusers, which often times have made their accusations more for revenge and singular benefit, then for the profit of the King or of his people, which accused persons, some have been taken, & sometime caused to come before the Kings Counsel by writ or otherwise, upon grievous paine against the law. It is assented and accorded, for the good governance of the Commons, that no man be put to answer without presentment before Iustices or matter of record, or by due processe and writ originall, according to the old Law of the land, and if any thing from henceforth be done to the contrary, it shall be void in the Law, and holden for errour.*

All which forementioned good Lawes are all and every of them confirmed by the Petition of right made in the third year of the present King Charles, which expresly saith, no man ought to be adjudged but by the lawes established in the Realme, and not otherwise, which Petition of right, you your selves in this present Parliament have in every point confirmed, as appeares by the statute that abolisheth the Star-Chamber, and by the Statute that abolisheth Ship-money and you your selves with your hands lifted up to the most high God, have often sworne, vowed, protested and declared, you will maintaine, preserve and defend the fundamentall lawes of the land, and square your actions accordingly, and imprecate the wrath and vengeance of the great God of Heaven and Earth to fall upon you, when you cease to performe what there you sweare to and declare. And therefore honourable Gentlemen, what thoughts soever of indignation and displeasure you have towards me, I hope you will be so tender of your owne honours and reputations that you will not in the least endeavour, to deale with me contrary to the pattern and meaning of the formentioned honest, just and good lawes, and if you please to let me enjoy the benefit of them, I shall be ready to ioyne issue with you, whomsoever you please, without craving any mercy, pity or compossion at your hands, and legally to answer whatsoever J have said or done.

But under the favour of this honourable Committee, I doe humblie conceive it will neither be just nor honourable for the house of Commons to punish me either for a pretended or reall crime committed by me in a hard, tedious, provoking and uniust imprisonment, while my case is depending before themselves, and I by themselves extreamly delayed in receiving iustice and right, therefore I make it my humble suite unto this honourable committee, to represent my iust desire to the honourable house of commons, that they would first adiudge my cause betwixt the house of Lords and me, which hath been dependant before them about this 8, moneths, and either according to the lawes and constitutions of the land, iustifie me or condemn me, and then in the second place, when they have done righteous and true iudgement in this, then I desire them if they have any reall or pretended crime or crimes to lay to my charge, committed by me in my present, hard, unjust and extraordinary provoking imprisonment, whilst J am managing my businesse before them, that then they would proceed according to law with me, and according thereunto to punish me without mercy or compassion, which proposition I hope is so rationall, that in iustiece it cannot be denied me. So humbly taking leave of your honours, I subscribe my selfe.

honourable House of Commons,

to be commanded

by them according

to law and justice

but no further.

And having concluded my paper, now Mr. Corbet said I, if you please lets goe to the question, well then said he will you renounce this booke or no? Sir said I, I had rather give you leave to heugh me in ten thousand peeces, then renounce any act of mine, done by me upon grounded, mature and deliberate consideration, and therefore Sir, somethings before hand premised, J shall give you a possitive and satisfactory answer to the question.

And therefore in the first place, I desire you and all here present to take notice, that I doe not return you an answer to your question out of any opinion that J am bound in duty or conscience unto your Authority to doe it, because you command me to doe it, for I know J am (actively) only to obey you in lawfull things, which this is not in the least, for by law no man what ever is bound to betray himselfe.

Nor secondly, J doe not return you an answer to it, as though I were bound by any law in England there to; for I have before punctually proved it to your faces out of my paper, that it is altogether unlawfull by the law of the land, to presse or force me to answer to interrogatories. Neither lastly, doe I answer your interrogation, out of any base tymerousnesse to betray the liberties & priveledges of the lawes of England, or to save my from selfe your insenced indignation, and therefore protesting that my answering your question, neither is, shall or justly can be drawn into president in future time, to compell me or any other free men of England, to answer to interrogatories, and therefore having (premised these things) affirmatively, I return you an answer to your question out of this consideration, that when I pend that book, I was inwardly exceedingly pricked forward to it, and framed it, with a resolution to lay down my life in the justification of it. And secondly, J return you an answer to the question out of this consideration, that upon your summons, I came before you with an absolute resolution to owne and avow that booke, (though I have been much by some of my friends perswaded to the contrary) alwayes provided I could get somethings effected before I did owne it, which I have already done, (that so I might set it in a way to come to a legall justification.) For first J have got the doore openned, that so I might have a publique hearing as my right by law. And secondly, J have obtained liberty (though with much a doe) to declare before you, in the presence and hearing of all these people, the illegallity of all yours, and all other Committees proceedings, inforcing the free men of England, (against the known and fundamentall lawes, of the land, and your own oathes,) to answer to selfe accusing interrogatories, and now having fully effected what I desired and thirsted after, I come now with as much willingnesse and readinesse to answer to your question, as you are to have me answer to it, and avowedly I tell you, I invented, compiled and writ that booke, and caused it to be printed and dispersed, and every word in it I will own and avouch to the death, saving the Printers Erratas, which if you please to give me the booke, and liberty of pen and inke. I will correct and amend them under my own hand, and return you the booke again, with my name annexed, under my own hand at the conclusion of it. Well then said Mr. Corbet, take the book and pen and inke, and goe mend it, truly Sir, said I, I have but one good eye to see with, and yet for that, I am forced to use the helpe of spectacles, and I have very much this day wrained the strength of my eyes, with reading and writing, and besides the booke is five sheets of paper, so that it is almost impossible for me seriously and carefully (with my weak eyes) to read it over this night, but if you please to give me but any reasonable time, I will be very punctuall in returning it to you againe; so I had tell Wednesday in the afternoone given me, and accordingly I amended the faults under my own hand, which principally were litterall and verball faults, and at the conclusion of the booke. I writ, examined and avowed by me John Lilburn, 10. Feb. 1646.

And upon Wednesday, I inclosed the book with a copy of my forecited paper that I read at the Committee) in a letter sealed to Mr. Corbet the Chairman of the foresaid Committee, the true copy of which letter thus followeth.

ACcording to my promise, I have corrected the Printers Erratas, and subscribed my hand thereto, and sent you back inclosed the very book you delivered to me with a true copy of my paper I read before you at the Committee, which is all I have at present to trouble you with, but to subscribe myselfe.

illegall and tyrannicall

imprisonment, in the tower of London

this

Common wealth of England, and

your reall servant, if you will be

true to the publique trust reposed in you,

and act for the preservation of the fundamentall lawes

of the land, Iohn Lilburn.

But after this little digression, J return to the rest of that which followed at the Committee, which was to this effect, as soone as I had ownd the book, and received the book from Mr. Corbet, I said Gentlemen, you having as I perceive done with me, I shall humbly crave liberty to make one motion to this Committee, for the discharge of my wife, for by vertue of your warrant she is a prisoner, for dispersing some of my bookes, and truly gentlemen she is my wife, and set at worke to doe what she did at the earnest desire of me her (unjust imprisoned) husband, and truly I appeale to every one of your own consciences, whether you would not have taken it very ill at the hands of any of your wives? if you were in my case, and she should refuse, at your earnest desire to doe that for you that she by my perswasions hath done for me, therefore I intreat you to set her at liberty, and set the punishment of that her action upon my score, so with one consent she was discharged, for which I thanked them. Now Gentlemen with your favour and patience I humbly intreat you to heare me but one word more, which is this, I was the other day robd or at least plundered, and had my house violently, forceably, & without any colour of law or conscience entred, & an Iron latch drawn, as I am informed by one Whittaker a book-seller, who dwels in Pauls Church-yard, who with others like high contemners and violaters of the law, loaded away, as I am informed three porters with my true and proper goods, that I bought with my owne proper monie, and he pretended he did it by vertue of a warrant from this Committee, therefore I humbly desire to know, whether this Committee will avow his action, and heare him out in what he hath so done? No saith Mr. Corbet, he had no such power from this Committee, as forceably to enter your house, nor to meddle with any of your goods or bookes, but only at randome to seize upon all of this booke where he could find them. Well gentlemen, then here is a high act of violence and contempt of the law committed, for here is my house by violence entered, and so many of my goods as they pleased to seize upon carried away, none belonging to me being present to see what they did, and my doores by them left wide open, for any that had a mind to goe in and take away, and rob me of all the rest of my goods that they left, for which actions I hope I shall obtaine justice in time, but in regard you say your warrant did not authorize him to take any of my bookes, but The Oppressed mans Oppressions declared, and yet he tooke away abundance of severall other bookes besides that, which I bought with my monie I hope this honourable Committee will be so just as to command him faithfully to restore me them all again, or at least all but the hundred of the present bookes in controversie, and I was fairely promised I should have them, but as yet I have found no performance at all, though truly I doe conceive there was as many books carried away by him as stood me in about twenty or thirty pounds, for there was the greatest part of a thousand of my bookes, called London Charters, the printing of which with the paying for the copies of the originall Charters, &c. (which I had out of the Record office in the Tower) cost me almost twenty pounds, besides a great many of severall other sorts. And at my withdrawing, the people cryed out, they never would answer to close Committees any more, being the doores by law ought to be open, which they never knew before. Now friend, I know you are acquainted very well with some able and honest Lawyers, and therefore I pray doe me the favour as inquire of them, whether all these things laid together, it be not an act of Fellony in the forementioned Whittaker, &c. thus forceably to enter my house, and without any reall or pretended warrant to take away my goods; but if it be not fellony, I desire to know of them, what effectuall course, I may take in law, to obtaine my just and legall satisfaction for this illegall wrong, and making these catch-poule Knaves (who are as bad if not worse then the Bishops Rookes and Catch-poules) examples to all their fellow Knaves and Catch-poules.

Thirdly, I desire to know, whether by law, any free mans house in England can be broken open, or forceably entered under any pretence whatever? unlesse if be for fellony and treason, or a strong and grounded suspition of fellony or treason, or to serve an execution after judgement for the King?

Fourthly, if any person or persons whatever, shall indeavour to break open, or forceably enter my house, or any other free mens of England, upon any pretence what ever, but the forementioned, or some other that is expresly warrantable by the known law, whether according to Law or no, I may not stand upon my owne defence in my owne house being my Castle and Sanctuary, and kill any or all of those that so illegally (though under specious authoritive pretences) shall assault me.

Fiftly, whether in law it be not as great a crime in the foresaid Whittaker, &c. forceably to enter my house, and carrie away my own goods lawfully come by, under a pretence of a warrant signed by a single Member of the House of Commons, commonly called a Chair-man of a Committee. As for Sir William Beacher Clark of his Majesties Privie Counsell, Old Sir Henry Vaine a Privie Counceller, and (if I mistake not then) Secretary of State, and Mr. Laurance Whittaker that old corrupt Monopolizer, now Member of the House of Commons; by vertue of Regall, or Councell-Board authoritie, to search the pockets, or break open the study doors of the Earle of Warwick, the Lord Say, Mr. Hambden, Mr. Pym, Mr. [Editor: illegible word] or any other of those that was so served after the breaking up of the short Parliament, for which by this present Parliament (as I am credibly informed from knowing and good hands) Sir William Beacher was committed to the Fleet, Mr. Laurance Whittaker to the Tower, and old Sir Henry Vaine, who as it is credibly said was this principall actor in this businesse, and was in this present House of Commons, strongly moved against, againe, and againe, and in all probability had sparred soundly for it, if it had not been for the interest that his Son young Sir Henry had in Mr. John Pym, and the rest of his bosome associates, who as it plainly (now appeares, for ends besides the publique, had use to make of him against the Earle of Strafford, who was one of the chiefe men that stood in their way, and hindred them from possessing themselves of those high and mighty places of honour and profit that is now too much apparent they then aspired unto, and therefore truly when I seriously cast my eye upon their continued serious of actions, (especially of late) my conscience is overcome, and J am forced to thinke that there is a great deale of more truth in many of the charges fixed upon them, in those two notable Declarations of the Kings, (then at the first reading of them, I conceive there was) the first of which is the 12. of August, 1642. and begins book Decl. 1. part pag. 514. some notable passages of which Mr. Richard Overton and my selfe have published in the 6 pag. of out late discourse, called The out-Cry of Oppressed Commons unto which I shall desire to ad one more, and that is of their partiallity in judgement, which the King chargeth them with (ibim) page 516 “That they threw out of their house some Monopolizers, as unfit to be Law-makers, because their principles was not fit for the present turns of the powerfull party there, and kept in other as great Monopolizers as those they threw out, because they did comply with them in their ends, and the King instances Sir Henry Mildmer, and Mr. Laurance Whittaker, both of whom, for all their transgressions, still sit in the House. And if it be an act of treason to exercise an Arbitrary and tyrannicall power (for so it was charged upon the Earle of Strafford, &c.) then I will maintain it, Mr. Laurance Whittaker is guilty of it, for he hath severall times done it unto the free men of England, yea upon me in particular, as at large you may read in my book called Innocency and Truth, justified, to the apparent hazard of my life and being, for which I will never forgive him, tell he hath acknowledged his fault, and made me legalland just satisfaction, the which if he do not the speedier, seeing by his unreasonable priviledge, as he is a Parliament man, that by law I cannot meddle either with his body or goods, I will by Gods assistance (seeing I have no other remedy) pay him with my pen, as well as ever he was paid since his eyes was open, cost it what it will and therefore I now advise him, if he love his owne reputation, without any more adoe to acknowledge his fault by giving me legall satisfaction.

The King second Declaration, is an answer to the two Houses Declaration of the proceeding of the Treaty at Oxford 1643. and in the second part book Decl. pag. 100 printed Anno 1646. where in pag. 101. he chargeth them possitively, “that the maintenance and advancement of Religion, justice, liberty, propriety and peace, are really but their stalking horses and neither the ground of their warre nor of their demands, and I for my part must ingeniously protest and declare unto you, that the dealings of both houses with me, and others of the Kingdomes best friends is such, that as sure as the Lord lives, I should sin against my own soule, if I should not really beleeve this particular charge of his Majesties to be most undeniable true and just, and to my understanding he there gives notable demonstrations to evince and cleare the forementioned charge, I shall only instance that in pag. 112. 113. VVhere his Majestie framing an answer to something they say in their Declaration about the Iudges, and Members of Parliament, he saith. “That by never having appeared at all in the favour, excuse or extenuation, of the fault of those Iudges (who are to answer for any unjust judgement, in all which his Majesty left them wholly to their consciences, and whensoever they offended against that, they wronged his Majesty no lesse then his people.) And by his being yet so carefull of those Lords and Gentlemen, it may appeare that his Majestie conceives, that those only adhere to him, who adhere to him according to law. And whether the remaining part of the Houses be not more apt to repeale their own impeachments and proceedings against those Iudges, (if they conceive they may be made use of and brought to adhere to them) then his Majestie is to require they should, may appear by their requiring in their 14 propositions, that Sir John Bramston (impeacht by them selves of so great misdemeanors) may be made chiefe Iustice, and by their freeing and returning Iustice Barkly, (accused by themselves of high Treason) to sit upon the bench, rather then free and imploy Iustice Mallet, who was not legally committed at first, but fecht from the bench to prison by a troop of Horse, and who after so many moneths imiprisonment, remaines not truly impeacht, but wholly without any knowledge of what crime he is suspected.

And indeed their partiallity in doing justice and judgement, appeares in no one man in England (I thinke more, then in old Sir Henry Vaine, who by all men that I can talke with that knowes him and his practises, renders him a man as full of guilt (in the highest nature) and court basenesse, as any man what ever that was there. For I have credably been told by one that sate in the short Parliament, “that he was the maine and principall man, that instrumentally brok up that Parliament, for in the House in the Kings name he strongly moved for twelve Subsidies, when he had no such Commission from his Majestie, but did it of purpose to set the Parliament in a heat, and make them fly high against the King, of which heat he took advantage, and then went to the King, and incensed him against them, and thereby provoked him to break it up, on set purpose to save himselfe from being questioned about his dangerous and desparate Monopoly of Gun-powder, and other of his illegall Knaveries, in which he was deep enough even over both boots and shooes. For Sir Iohn Eveling was the old powder master, and then Sir Henry Vaine stept in, and justled him out, and got in one Mr. Samuel Cordwell one of his own servants that waited upon him in his Chamber, who had the sole Monopoly of making all the powder in England, and furnished power for [Editor: illegible word] into the Tower, which powder was sold out commonly for 18. per. l. at the first hand, besides the charge of getting first a warrant from the Counsell board, to the Lord Newport, then master of the Ordinance, to sell such and such so much powder, which warrant besides the losse of time and trouble, cost deare enough, then there was a second warrant from the Lord Newport, to be obtained to the officers of the Ordnance to deliver the powder out, according to the warrant of the Counsell board, and then there was a third warrant to be got from the officers of the Ordnance to the particular Clarke that kept the powder, all which besides trouble, cost, money, besides a fee of a mark which was paid by the buyer to the officers of the Ordnance, for every last of powder they delivered, and the forementioned Cordwell, Sir Henry Vaines Gun-powder Agent, constantly ingaged to bring in every moneth to the Tower 20. last, there being 24. barrells in every last, and 100.l in every barrell, and besides he (as the principall instrument of setting this dangerous Monopoly on foot) forced the Marchants, and sea men, many times for divers dayes together, to stop their viages to their great and extraordinary detriment, till they would give large bribes, or were forced to use some other indirect means, to obtaine his warrant, &c. to get powder out of his unjust Monopolizing hands to furnish their ships, for which notwithstanding they were forced to pay above double the price for it, (nay almost trible) according to the rate it was sold at before his Monopoly.

Yea, and by this meanes, he wickedly and illegally disfurnished all the Countryes in the Kingdome, as is notoriously known to all the Deputy Lieutenants, by meanes of which he laid the King some open to the invasion and over-running of a forraign enemy, which did create, nourish and foment, strange and strong jealousies in the people, that there was some strange and desparate designe upon them to inslave and invasolize them, which was no little occasion of our present warres, by blowing of coales to the fomenting and increasing of devisions betwixt the King and the people.

Yea, and besides all this, he was not one of the least of Canterburies Creatures, being not a little active in the Star-Chamber, to serve his ends, the smart of which with a witnesse, I am sure my shoulders felt. For upon the 13. of Feb. 1645. in the 13. yeare of the present King, the Lord Coventry, Earle of Manchester, Lord Newburgh, old Sir Henry Vaine, Judge Bramstone, and Judge Jones, in the Star-Chamber sentenced me for refusing to take an illegall oath to answer to their Interrogatories to pay to the King 500.l to be bound to my good behaviour to be whipt through the street to Westminster, and there to be set upon the Pillory, and then to remaine in prison tell I conformd to their tyrannicall commands. Which decree or sentence you may at large read in the 1, 2, 3. pages of my printed relation of my Star-Chamber sufferings, as they were presented by my Counsell, Mr. Bradshare, and Mr. Iohn Cook, before the Lords at there Bar, and proved by witnesses, the 13. Feb. 1645. the barbarous execution of which you may read not only in that relation, but also in a large relation of it, made and printed by me, that yeare I suffered, called the Christian mans tryall, and lately reprinted by Mr. William Larnar in Bishops-gate street, and in my bookes also then made, called, Come out of her my people, the afflicted mans Complaint, A cry for justice, my Epistle to the Aprentizes of London, and my Epistle to the Wardens of the fleet, which foresaid sentence the House of Commons after a long and judicious examination and debaite, thus voted.

Die Martis, May 4. 1641.

Mr. Rouse this day reported Iohn Lilburn his cause, it was thereupon ordered and resolved upon the question as followeth.

Resolved upon the question,

That the sentence of the Star-Chamber given against Iohn Lilburn is illegall and against the liberty of the Subject, and also bloody, wicked, cruell, barbarous and tyrannicall.

Resolved upon the question.

That reparations ought to be given to Mr. Lilburne for his imprisonment, sufferings, and losses sustained by that illegall sentence.

Ordered that the Committee shall prepare this case of Mr. Lilburnes to be transmitted to the Lords, with those other of Doctor Bastwicks, Doctor Leighton, Master Burton, and Mr. Pryn.

Hon. Elsing Cler. Dom. Com.

And though it was a matter of foure yeares before I could get this my ease transmitted to the Lords, the obstructing of which I cannot attribute to any, but principally to that old crafty Fox, Sir Henry Vaine, (who I am confident of it hath long since deserved the Ax or Halter) and and his powerfull interest and influence, especially by his sonne, young Sir Henry, though (Mathiavel like) he faces and lookes another way, who for all his religious pretences, I for my part thinke to be as crafty (though not so guilty a) Colt as his Father, which I beleeve I could easily and visibly demonstrate, which I groundedly apprehend I have sufficient cause administred unto me to doe, especially for some suttle, cunning, but mischievous late underhand dealings by as guilded instruments as himselfe, but at present for my own interest sake I will spare him, though (my fingers itches,) yet I must tell him, I am very confident for all his disguises, he will shortly be known to consciencious, men, to be but at the best (if he be no more) then one of the prerogative quench coales, to keep the people in silence, from acting and striving to deliver themselves from slavery and bondage.

And when, came amongst the Lords, they the 13, Feb, 1645 decreed, that that sentence, and all proceedings thereupon shall forth with before ever totally vacuated, obliterated, and taken of the file in all Courts where they are yet remaining, as illegall, and most unjust, against the liberty of the Subject, and law of the land, and Magna Charta, and unfit to continue upon Record, and that the said Lilburn shall be forever absolutely freed, and totally discharged from the said sentence and all proceeding, thereupon, as fully and ample as though never any such thing had been, &c.

Which where you may at large read in the foresaid relation, yea, and by an other decree, ordered me to [Editor: illegible word]. And down into the House of Common, they send my Ordinance for their concurrance, which is there again blockt up, as I may too justly conceive by the powerfull and unjust interest of the forementioned old, tyrannicall Monopolizer, Sir Henry Vaine, for which by Gods assistance, seeing I have no other remedy, nor meanes left me, to obtain my right, and the Iustice of the Kingdome, I am resolved to pay him, (and all that I can groundedly know and heare joynes and concur, with him to destroy me, and hinder me of justice and my right which should preserve me and keep me and mine alive) cost it hanging, burning, drowning, strangling, poysoning, starving, cutting to peices, or whatever it will or can, yea, though it tooke me all the interest I have in the world, in any or all the great ones there of, put Lien. Gen. Cromwell into the number.

And therefore J desire not only your selfe, (but all impartiall Readers that reads these lines) to judge whether it be not the hight of partiallity and injustice in the House of Commons, to suffer him to sit and vote there, especially they having throwne out divers others, for ten times lesse faults then he is publiquely known to be guilty of, and I desire you to satisfie me, whether or no the people for their owne wellfare are not bound, and may not groundedly petition the House of Commons to throw out him, who is so great a transgressor and violater of the Lawes of England, and therefore altogether unfit to be one of those that maketh and gives lawes unto the free men of England, for in my apprehension if there were no more to be laid unto his Charge, but to have been so unjust and unrighteous a Iudge, as to have had a finger in inflicting a sentence that is voted by the house of Comons in the dayes of their verginity, purity and uncorruptnesse, (to what it is visibly now, yea, himselfe sitting as a Member there) to be not only illegall, and against the liberty of the Subject, but also bloody, wicked, cruell, barbarous, and tyrannicall, it alone were legally and justly cause enough for ever to eject him. O England, England! woe unto thee! when thy chosen preservers turne to be thy grand destroyers, and in stead of easing thee of thy grievances, with a high hand of violence protect from justice those that commit them, and thou seest it and knowest it, and yet art like a silly Dove without heart, and dares not open thy month wide to reprove it, and indeavour by petition or otherwise the amending of it, surely and undeniably that body, who, or what ever it be that is not able to evacuate its exerements, is nigh unto the giving up the Ghost, or bursting out into such botches and ulcers, that it shall be an eye sore to all that behold it, and stinke in the nostrels of all men, that have their senses.

But with your patience, I will trace this old Fox a little further, and see how he hath plaid his cards since this Parliament sate, and to let pass his unfaithfull dealings with his master the King, whose Secretary of State he was, and yet could not, or would not keep his secrets, (which is an act base enough in itselfe) although as J have been told by one very neare and deare unto him, his places he injoyed under the King, were worth to him, 8000 l. per annum, but having as before as truly observed, before this Parliament (by acts of basinesse done, as he was a Courtier and a Courtiers Counseller) ran himselfe over boots and shooes and seeing that it was impossible for him and all his confederates, to break of this Parliament, as they did the late short Parliament, therefore it behoved him for the safety of his own head, to lay his designes so, as that he might by the swaying party merit preservation to himselfe, which to doe, being as he was a Secretary, privie to all the King and Courts principall secrets, though he was under an Oath, and the strictest obligation of secrecie that could be, yet they must all out, and out they went, as in the case of the Earle of Strafford, of which I have, heard some great ones say, it was scrued to the highest pin, if it were not higher then in honestly and justice it should, but all this was done, that he might not only save himselfe, but gaine an esteeme in the present Parliament, and so be in a possibillity, by the interest of his son, Sir Henry, (although to men that were halfe blind, there was, and I thinke still is a seeming enmity betwixt him and his Father) in time to make himselfe amends, for his 8000.l a yeare by his places, which by differring of the King (to save himselfe) he was likely to loose, (and indeed it is commonly reported, that in his place as one of the Committee of the King revenue, he hath learned to lick his own fingers well) and the first or grand step of honour he attained to, by the Parliament, was to be made Lord Lieutenant of the County of Durham, and the wars comming one betwixt the King and Parliament, to indeare himselfe againe unto the King (knowing that the chance of warre was doubtful) he sent his second son, Sir George Vaine to waite upon and serve the King, who in person was actuallt at, and in the battell of Edge-Hill, with the rest of his fellow Courtiers, but to make up his case the more with the King, though himselfe stand with the Parliament, where as a seeming friend to them, he was able to doe the King truer service, yea, and did it then if he had been with him, for instead of protecting, preserving, securing and defending the County of Durham, (of which he was Lieutenant) according to the duty of his place, and those many importunare desires expressed unto him by the well affected Gentlemen of the Country, which were all in vaine, for in stead of preserving the Country, he sent his Magazine of Armes from his Castle at Raby, (by his two principall servants, Mr. William Conyers Steward of his land, and Mr. Henry Dingly his Soliciter at law) as a present for the King, to the Earle of New-Castle, then in Armes at New Castle against the Parliament, who might then have been easily supprest at his comming to New Castle, if old Sir Henry Vaine had been true to his trust the Parliament reposed in him.

And that he sent them is visible enough, for they carried them openly and avowedly in the day time through the Country, boasting of their act both in their going and comming, and at New Castle from the hand of one of the Earles servants or Officers, received, a note for the receipt of those armes, that so when time should serve, Sir Henry Vaine might have it to justifie his good service done for his Majestie in being the principall instrument of raising the Earle of New Castles Army, and giving the King so great a footing in the North as there he had, for his Armes being sent to the Kings Generall so openly, publiquely and avowedly as they were, though his person were with the Parliament, yet it made all people there to conclude that he was himselfe absolutely for the King against the Parliament, which presently (his influence in those parts being great) got the Earle of New Castle a mighty repute and credit, and made those that were really for him to be impudent and bold in their attempts, and made abundance of Newters then to declare, (all or most of whom might at the first have been made serviceable to the Parliament, if they had been lookt to betimes) and the most of those few of cordiall, well affected Gentlemen, were immediately forced to fly and leave all they had behind them, and the rest that stayed, were immediately taken prisoners and destroyed, (as well as the other) in their estates, for which Sir Henry Vaines land and estate, ought in justice and conscience to goe to the last penny of it, to make them satisfaction, being the true instrumentall cause of all their losses, woe and misery, and of all the woe and misery of the whole North, occasioned by the Earle of New-Castles forces, and those that were necessitated to be raised to destroy them, which if they had never had a being, there had never been no need of the Scots comming into this Kingdome to our deare bought ayde, the evill consequences of whose comming, I am afraid England this twise seaven yeares will not [Editor: illegible word] of without a great deale of blood shed and misery, the yoak of Presbyterian bondage alone, (besides then co-operations, if not co sharing in the Civill government of England, to the unspeakable prejudice to the freemen thereof) which they brought with them over Tweed to this Kingdome, which is likely to prove 100. times worse then the tyranny and Lordlinesse of the Bishops. One thing more about Sir Henry Vaine I desire you to take notice of, and that is further to demonstrate, that his servants carried the Armes, not of their owne heads, but by his command, or at least good liking, is this, that he never complained to the Parliament of it, nor never indeavoured to have them punished for it, but rather protected and defended them, so that those that complained of them, as well as of himselfe, by reason of his greatnesse, could never be heard nor obtaine justice, though it was with some zeale followed by my Father, & my Vnkle Mr. George Lilburn, with other Gentlemen of the same Country, as you may partly read in Englands Birth Right pag. 19. 20. 21.

All this while, if the King lost the day and the Parliament prevailed, here was himselfe and his son, young Sir Henry to make good his interest here, so that of which side soever the [Editor: illegible word] went, the old crafty Fox was sure in his owne thoughts co stand upon his leggs, and be no looser, but perceiving the King likely to goe down the weather, by the Scots comming in, he whistles away his son Sir George Vaine from the Kings Army. And though the Parliament had upon the 20 May 1642 voted. That when soever the King in both war upon the Parliament, it is a breach of the trust reposed in him by his people, contrary to his oath, and tendeth to the dissolution of this Government. And that whosoever shall serve or assist him in such warres, are Traitors by the fundamentall lawes of this Kingdome, and have been so adjudged by two Acts of Parliament, viz. 11. R. 2. and 1 ll. 4:

And yet notwithstanding, though Sir George Vaine did both serve and assist the King actually at the battell at Edge-Hill, yet as soone as any footing by the Parliament is gotten in the County of Durbam, he is by his Father, (and I thinke I might say brother too) for it is impossible if young Sir Henry were honest and true to the publique interest of his Country, according to what he seemingly professes, and would be thought to be, that his father and brother should doe such actions as they have done and dayly doe, and escape scot free, and no man to be heard that complains of them, but rather crushed and destroyed, which could not be, if he and his interest did not support them in all their basenesse) I say Sit George is by his Father sent down into the Country, as the only fit man to govern it, by deserving well at the hands of the Parliament for being with the King at the battell of Edge-hill, and therefore his made the receiver of the Kings sequestered revenue there, worth to his particular a great many hundreds pounds per annum, and is also made chiefe Deputy Lieutenant, yea, as it were Deputy Lord Lieutenant, Iustice of peace and quorum, Committee man and Chair-man of the Committee, and hath also the Posse commitatis of the whole County put into his hands, as being the fittest man to be High Sheriffe there, yea, and now in that County, whatever a King is in his Kingdome, that saying of Daniel chap. 5, 19. concerning the power of Nebuchadnezzar being too truly verified of him and his father, in reference to their acted and executed power in that poor County, that whom they will they set up, (yea, even as arch blades as Sir George himselfo) and whom they will they pull down, and all the people there in a manner tremble and feare before them.

But this is not all, for the Parliament upon the clearing of the Country, sent a Magazine of Ammunition and Armes downe, which was landed and laid up at Sunderland in the possession of my Vnkle, Mr. George Lilburn, one of the Deputy Lieutenants, and Iustices of Peace, &c. of the County, which Sir George Vaine by his supreame prerogative sent for away, and put into his Fathers Castle of Raby and laid in store of Provisions there, but I will not say he sent for some scores of Cavieliers from a Castle in Yorkshire to come and take possession of it so soone as he had so done, but this I will say, that they did come and take possession of it with a great deale of ease, and it cost the Country some thousands of pounds before they could take it againe. So here you have at present a briefe relation of the game that Sir Henry Vaine hath plaid this many yeares together, by meanes of which he hath got a great estate, but I may say an ill estate, to leave to his son Sir Henry principally, a man for all the experience I have had of him, (and I have had not a little) no whit inferior in my apprehension to his Father in Mathiavels principles, for all his guilded professions, and truly it is very strange to me what the Family of the Vaines hath deserved of this Kingdome, that they must have so many thousands pounds a yeare out of the Kingdomes Revenue, in its present great and extraordinary poverty, as they have, never any of which ever hazarded the shedding of one drop of blood for the Parliament or Kingdome. And besides the two sonnes before mentioned, there is a third lately come out of Holland that was a Captain there, and though he hath not one foot of Land in the County of Durham, yet he is as I am informed lately made a Iustice of peace, and hath besides profitable and gainefull Offices there. I pray Sir, what doe you thinke such doings as this (of which the Parliament is full, as I could easily declare) doth portend to the whole Kingdome, doe you thinke that it portends lesse then absolute vassolage and slavery to the whole Kingdome, by a company of base and unworthy men, setup by the people, whom they may if they please pull downe by calling them home, and chuse honester men in their places, in a new Parliament to call them to a strict accompt, without doing of which the lawes and liberties of England are destroyed, and our proprieties utterly overthrow, that doe and will tyrannise ten times worse over us, then ever our prerogative task-masters of old did.