John Lilburne, The Just Defence of John Lilburn (25 August 1653).

Note: This is part of the Leveller Collection of Tracts and Pamphlets.

Editor’s Introduction

(Placeholder: Text will be added later.)

Bibliographical Information

ID Number

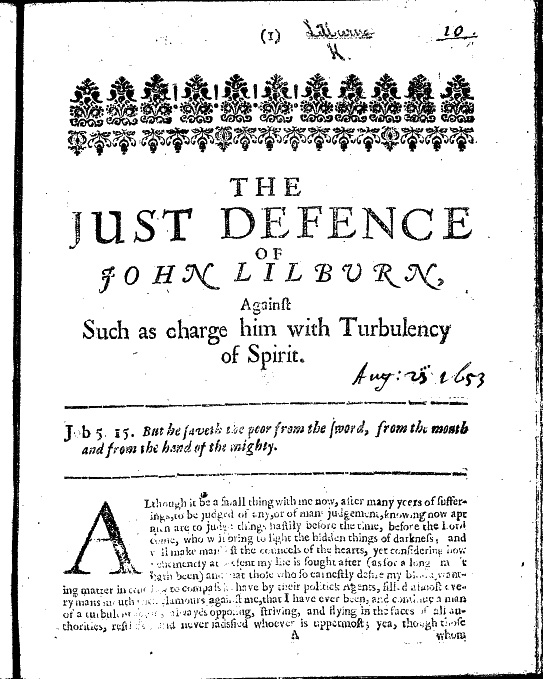

T.239 [1653.08.25] John Lilburne, The Just Defence of John Lilburn (25 August 1653).

Full title

John Lilburne, The Just Defence of John Lilburn, Against Such as charge him with Turbulency of Spirit.

Job 5.15. But he saveth the poor from the sword, from the mouth and from the hand of the mighty.

Estimated date of publication

25 August 1653.

Thomason Tracts Catalog information

TT2, p. 34; Thomas E. 711. (16.)

Text of Pamphlet

ALthough it be a shall thing with me now, after many yeers of sufferings, to be judged of any, or of mans judgement, knowing now apt men are to judge things hastily before the time, before the Lord come, who will bring to light the hidden things of darkness, and will make manifest the councels of the hearts, yet considering how vehemently at prsent my life is sought after (as for a long time it hath been) and that those who so earnestly desire my blood wanting matter in true law to compass it, have by their politick Agents, filled almost every mans mouth with clamours against me, that I have ever been, and continue a man of a turbulent spirit, alwayes opposing, striving, and flying in the faces of all authorities, restless, and never satisfied whoever is uppermost; yea, though those whom I my self have labored by might and maine to advance and bring into power: and that therefore it is very requisite I be taken off, and that otherwise England must never look to rest long in peace; yea, so turbulent, that if there were none in the world but John Lilburne, rather then want one to strive withall, forsooth, John would certainly quarrel with Lilburne. Finding that this, how slight and unjust soever, hoth prevailed more then true Christianity would admit, and threatens my life more then any matter that is against me, most men of judgement evidently seeing that nothing is laid to my charge, worthy either of death or bonds; I take my self obliged to vindicate my conversation from all such wicked & causless aspersions left by my silence I should seem guilty, and to have nothing to plead in my defence.

All therefore who have any of the true fear of God in them, may please to take notice, that as they ought to judge nothing before the time, so are they to be careful not to judge according to appearance, but to judge righteous judgement: the reason is, because the appearance of things, the gloss and outside is usually made by politicians, the Arts-men and Crafts-men of the world, for maintenance of their corrupt interests; these will be the sole interpreters of men and things, raising, by art and sophistry, such mists before mens eyes, as what therewith, and by changing themselves into the shape of Angels of light, deceive (were it possible) the very elect: but whosoever judgeth according to their Vote, is certaine to judge amiss, may soon be a slanderer, and soon after a murtherer; and if he stop not quickly, go to hell with them, which is the end of all such as love and make a lye, especially such lyes as whereby mens lives are put in danger.

For thus dealt the false prophets with the true, and by their craft and policy led many people to destroy them; and so likewise dealt the Scribes and Pharisees with the Lord Jesus himself, giving out he was a wine-bibber, a friend of Publicans and sinners, that he cast out devils by Beelzebub the prince of devils: and that for no other cause, but that he published doctrines destructive to their interest of glory and domination.

And just so dealt they with the Apostles and Disciples of our Lord, as may be seen Acts 4. and throughout the whole body of the Scriptures: and as Heb. 11. 37. were stoned, were sawn asunder, were tempted, were slaine with the sword, wandered about in sheep-skins and goats-skins, being destitute, afflicted, tormented, of whom the world was not worthy; they wandered in desarts, and in mountaines, and in dens, and caves of the earth. And all these in their several times were reviled and reproached as turbulent persons, as Paul and Silas were in Acts 17. 6. And when they found them not, they drew out Jason and divers brethren unto the rulers of the City, crying, These that have turned the world upside down, are come hither also, whom Jason hath received, and these do all contrary to the decrees of Cæsar, saying, There is another King, one Jesus.

And thus in every age ever since hath it been, as witness all the volumes of the books of Martyrs, and the Chronicles of almost every nation; and thus sometimes upon a religious, and sometimes upon a civil account, and very often upon both in one and the same persons: the most faithful servants of Christ in every country where they lived, being ever the greatest enemies to tyranny and oppression, and the most zealous maintainers of the known laws and liberties of their Country, as was John Hus in Bohemia, Jerom of Prague, John Wickliff in England, the Martyrs in Queen Maryes dayes, the Hugonots or Protestants in France, the Gues in the Low-Countryes; all not only esteemed Hereticks by the Church, but rebels and traytors to their several States and Princes.

And to come home to our selves, and to our own knowledge, none have in the least opposed the illegal practices of those that for the time being have been uppermost, but as they have been given out to be Hereticks and Schismaticks; so also to be factious and seditious, men of contentious and turbulent spirits: and this for no other cause, but for standing for the truth, and contending for the known laws of the land; the prosecutors and cryers out of turbulency, proving ever unjust persons and oppressors; and the oppressed and sufferers, though through the policies of wicked men they have been supposed to suffer as evil doers, yet a short time hath proved they have suffered for truth and right, and were both faithful to God, to their consciences, and truest friends to their native countries, and to the laws and liberties thereof, which rightly understood, give check to all such unjust and evil practices: So that if men would but consider whence the cry ariseth, and that it cometh ever from those that do the injury, and is done purposely to fit and prepare such for destruction as oppose their unjust designs, that whom by law they cannot destroy, first to kill their reputation, and to render them odious; that so what violence or bloody injustice is done unto them, may be digested, if not fully approved. I say, were these truths considered, well-meaning people would not be so easily deluded and drawn in to cry, as these politicians cry; nor so easily under the notion of turbulent spirits give up in sacrifice the lives and bloods of their dearest and best friends, to the lawless lusts and wills of ambitious men, untill none are left that dare utter one word in defence of known rights, or once open their mouths in opposition of arbitrary and illegal proceedings.

For wherein can it be made appear that I ever have been, or am of a turbulent spirit? true it is, since I have had any understanding, I have been under affliction, and spent most of my time in one prison or other; but if those that afflicted me did it unjustly, and that every of my imprisonments were unlawful, and that in all my sufferings I have not suffered as an evil doer, but for righteousness sake; then were they turbulent that afflicted and imprisoned me, and not I that have cryed out against their oppressions; nor should my many imprisonments be more a blemish unto me, then unto the Apostle Paul, who thought it no dishonour to remember those that somewhat despised him, that he had been in labours more abundant, in stripes above measure, in prisons more frequent, in deaths oft.

And truly, though I have not wherewith to compare with those glorious witnesses of God, that in the Apostles times sealed the restimony of Jesus with their bloods, nor with those that in the ages since, down to these times, who have with the loss of their own lives brought us out of the gross darkness of Popery, into a possibility of discerning the clear truths of the Gospel; yet as I have the assurance of God in my own conscience, that in the day of the Lord I shall be found to have been faithful, so though the policies of the adversaries of those truths I have suffered for, do blinde many mens understandings for a season concerning me, yet a time will come when those that now are apt to censure me of rashness and turbulency of spirit, will dearly repent that ever they admitted such a thought, confess they have done me wrong, and wish with all their hearts they had been all of my judgement and resolution.

There being not one particular I have contended for, or for which I have suffered, but the right, freedome, safety, and well-being of every particular man, woman, and child in England hath been so highly concerned therein, that their freedome or bondage hath depended thereupon, insomuch that had they not been misled in their judgements, and corrupted in their understandings by such as sought their bondage, they would have seen themselves as much bound to have assisted me, as they judge themselves obliged to deliver their neighbour out of the hands of theevs & robbers, it being impossible for any man, woman, or child in England, to be free from the arbitrary and tyrannical wills of men, except those ancient laws and ancient rights of England, for which I have contended even unto blood, be preserved and maintained; the justness and goodness whereof I no sooner understood, and how great a check they were to tyranny and oppression, but my conscience enforced me to stand firme in their defence against all innovation and contrary practices in whomsoever.

For I bless God I have been never partial unto men, neither malicing any, nor having any mans person in admiration, nor bearing with that in one sort of men, which I condemned in others.

As for instance, the first fundamental right I contended for in the late Kings and Bishops times, was for the freedom of mens persons, against arbitrary and illegal imprisonments, it being a thing expresly contrary to the law of the land, which requireth, That no man he attached, imprisoned; &c. (as in Magna Charta, cap. 29.) but by lawful judgement of a Jury, a law so just and preservative, as without which intirely observed, every mans person is continually liable to be imprisoned at pleasure, and either to be kept there for moneths or yeers, or to be starved there, at the wills of those that is any time are in power, as hath since been seen and felt abundantly, and had been more, had not some men strove against it; but it being my lot so to be imprisoned in those times, I conceive I did but my duty to manifest the injustice thereof, and claime and cry out for my right, and in so doing was serviceable to the liberties of my country, and no wayes deserved to be accounted turbulent in so doing.

Another fundamental right I then contended for, was, that no mans conscience ought to be racked by oaths imposed, to answer to questions concerning himself in matters criminal, or pretended to be so.

The ancient known right and law of England being, that no man be put to his defence at law, upon any mans bare saying, or upon his own oath, but by presentment of lawful men, and by faithful witnesses brought for the same same face to face; a law and known right, without which any that are in power may at pleasure rake into the brests of every man for matter to destroy life, liberty, or estate, when according to true law and due proceedings, there is nought against them; now it being my lot to be drawn out and required to take an oath, and to be required to answer to questions against my self and others whom I honoured, and whom I knew no evil by, though I might know such things by them as the oppossors and persecutors would have punished them for, in that I stood firm to our true English liberty, as resolvedly persisted therein, enduring a most cruel whipping, pilloring, gagging, and barbarous imprisonment, rather then betray the rights and liberties of every man; did I deserve for so doing to be accounted turbulent? certainly none will so judge, but such as are very weak, or very wicked; the first of which are inexcusable at this day, this ancient right having new for many yeers been known to all men; and the latter ought rather to be punished then be countenanced, being still ready to do the like to me or any man. I then contended also against close imprisonment, as most illegal, being contrary to the known laws of the land; and by which tyrants and oppossors in all ages have broken the spirits of the English, and sometimes broken their very hearts, a cruelty few are sensible of, but such as have been sensible by suffering; but yet it concerns all men to oppose in whomsoever; for what is done to any one, may be done to every one: besides, being all members of one body, that is, of the English Commonwealth, one man should not suffer wrongfully, but all should be sensible, and endeavour his preservation; otherwise they give way to an inlet of the sea of will and power upon their laws and liberties, which are the boundaries to keep out tyrany and oppression; and who assists not in such cases, betrayes his own rights, and is over-run, and of a free man made a slave when he thinks not of it, or regards it not, and so shunning the censure of turbulency, incurs the guilt of treachery to the present and future generations. Nor did I thrust my self upon these contests for my native rights, and the rights of every Englishman, but was forced thereupon in my own defence, which I urge not, but that I judge it lawful, praise-worthy, and expedient for every man, continually to watch over the rights and liberties of his country, and to see that they are violated upon none, though the most vile and dissolute of men; or if they be, speedily to indeavour redresse; otherwise such violations, breaches, and incroachments will eat like a Gangrene upon the common Liberty, and become past remedy: but I urge it, that it may appear I was so far from what would in me have been interpreted turbulency, that I contended not till in my own particular I was assaulted and violated.

Neither did I appear to the Parliament in their prime estate as a turbulent person, though under as great suffering as ever since, but as one grievously injured, contrary to the Laws and Rights of England; and as one deserving their protection and deliverance out of that thraldom wherein I was, and of large and ample reparation, as they did of Mr. Burton, Mr. Pryn, and Dr. Bastwick; and which their favourable and tender regard to persons in our condition, gained them multitudes of faithful friends, who from so just and charitable a disposition appearing in them, concluded they were fully resolved to restore the Nation to its long lost liberty without delay.

Being delivered by them, and understanding their cause to be just, the differences between them and the late King daily increasing, I frequently adventured my self in their defence; and at length, the controversie advancing to a war, I left my Trade and all I had, and engaged with them, and did what service I was able; at Edge-hill, and afterwards at Branford, where after a sharp resistence, I was taken prisoner; and refusing large offers if I would renounce them, and serve the King, I was cariyed a pinioned prisoner to Oxford, where I endured sorrows and affections inexpressible: yet neither by enemy nor friend, was ever to that time accounted turbulent, though I there insisted for my Rights as earnestly and importunately as ever, and as highly disdained all their threats or allurements; and again found so much respect from the Parliament, as when my life was most in danger, to be once more preserved by them; though then not so freely as at first, but upon the earnest and almost distracted solicitation of my dear wife, violently rushing into the House, and casting her self down before them at their Bar: for now their hearts were not so soft and tender as at first: but so far was I then from this new imputation of turbulency, either in City, Country, Parliament, or Army, that I had every ones welcom at my return; and my Lord General Essex to express his joy and affection to me, though he knew me a noted Sectary (a people he was so unhappy to disaffect) that he gave me no less then betwixt 200 and 300 l. in mony, and offers of any kindness; which I shall ever thankfully remember to his just honour.

But Col. Homsteed, and all non-conformists, Puritans, and Sectaries being daily discouraged and wearied out of that Army; and the Earl of Manchester Major General of the associate Counties, giving countenance unto them, I put my self under his Command, my then most dear friend, as much honored by me, as any man in the world, the now Lord General Cromwel, being then his Lieut. General: what services I performed whilst I continued under their command, will not become me to report; I shall onely say this, that I was not then accounted either a coward, or unfaithful; nor yet of a turbulent or contentious spirit, though I received so much cause of dislike at some carriages of the said Earl, as made me leave the service, and soon after coming for London, discovered so great a defection in the Parliament from their first Principles, as made me resolve never to engage further with them, until they repented and returned, and did their first works: from which they were so far, as that there had not been any corrupt practice formerly complained of, either in the High-Commission, Star-Chamber, or Councel-Table, or any exorbitancies elsewhere, but began afresh to be practised both by the House of Lords, and House of Commons, without any regard to those Antient fundamental Laws and Rights, for the violation of which, they had denounced a war against the King.

Nor did they thus themselves, but countenanced and encouraged the same throughout the Land, illegal imprisonments, & close-imprisonments, & examinations of men against themselves, everywhere common; and upon Petitions to Parliament, in stead of relief, new Ordinances made further to intangle them, and all still pointed against the most Conscientious peaceable people, such as could not conform to Parliament-Religion, but desired to worship God according to their own Judgements and Consciences; a just freedom to my understanding, and the most just and reasonable, and most conducing to publick peace that could be; and in the use whereof, I had in some yeers before, enjoyed the comfortable fruition of a gracious God and loving Saviour; and which occasioned me, so soon as the Controversie about liberty of Conscience began, to appear with my pen in its just defence, against my quondam fellow-sufferer Mr. Pryn, as a liberty due not onely according to the word of God, which I effectually proved, but due also by the fundamental Laws of the Land, which provide that no man be questioned, or molested, or put to answer for any thing, but wherein he materially violates the person, goods, or good name of another: and however strange the defence thereof then appeared, time hath proved that it is a liberty which no conscientious man or woman can spare, being such, as without which every one is lyable to molestation and persecution, though he live never so honestly, peaceably, and agreeable to the Laws of the Land; and which every man must allow, that will keep to that golden rule, to do as he would be done unto.

And though my ready appearing also for this my native Right, and the Right of every man in England, gained me many adversaries (for men will be adverse to the best and justest things that ever were, till through time and sound consideration, the understanding be informed) yet neither for this was I accounted turbulent, or of a contentious spirit.

My next engagement was as a witness against the Earl of Manchester, upon Articles exhibited by his Lieutenant-General Cromwel; wherein I being serious, as knowing matters to be foul, opened my self at large, as thinking the same was intended to have been thorowly prosecuted: but the great men drew stakes, and I was left to wrestle with my Lord, who, what by craft, as setting his mischievous Agent Col. King upon my back, and the Judges of the Common Pleas, and upon that the power of the House of Lords, as got me first an imprisonment in New-gate, and after that in the Tower. Against which oppression, for urging the fundamental Laws of England against their usurped and innovated powers, I then began to be termed a factious, seditious, and turbulent fellow, not fit to live upon earth. For now by this time, both House of Lords and House of Commons were engaged in all kindes of arbitrary and tyrannical practices, even to extremity. So that I must pray the judicious Reader well to mark the cause for which I was first accounted turbulent, viz. for urging the fundamental Law of the land against those that thought themselves uppermost in power, and above the power of Law, as their practices manifested; and he shall finde, that for no other cause have I been reputed so ever since to this very day; and that it shall be any mans portion that doth so.

About this time, the Army began to dispute the command of Parliament; and that as they largely declared, because the Parliament had forsaken their rule, the fundamental Laws of England, and exercised an arbitrary and tyrannical power over the consciences, lives, liberties, and estates; and instanced in me and others, who had been long illegally imprisoned. These now espousing the publike Cause, and that their onely end was, that the ancient Rights and Liberties of the people of England might be cleared and secured, not onely prevailed with me, but thousands others in London, Southwork, and most places thorowout the Land, so to adhere unto them, as notwithstanding great preparations against them both by Parliament and City of London, yet they prevailed without bloodshed. A friendship they should not have forgotten.

Obstacles being thus removed, I who with many others, had adhered to them, daily solicited the performance of the end of this great undertaking and engagement, viz. the re-establishment of the fundamental laws: but as it appeared then in part, and more plainly since, there being no such real intention, whatever had been pretended upon this our solicitation, the countanances of the great ones of the Army began to change towards us, and we found we were but troublesome to them, and accounted men of turbulent and restless spirits; but at that time the Agitators being in some power, these aspersions were but secretly dispersed.

We seeing the dangerous consequence of so suddain a defection, from all those zealous promises and protestations made as in the presence of God: and having been instrumental in their opposition of the Parliamentary authority, and knowing that in our consciences, not in the sight of God, we could not be justified, except we persevered to the fulfilling of the end, The restauration of the Fundamental Laws and Rights of the Nation; and I especially, who had spilt both my own and other mens bloods in open fight, for the attainment thereof, look’d upon my self as no other or better then a murtherer of my brethren and Country-men, if I should onely by my so doing make way for raising another sort of men into power, and so enable them to trample our Laws and Liberties more under foot then ever. Upon these grounds, I ceased not day nor night to reduce those in chiefest power into a better temper of spirit, and to perswade them to place their happiness not in Absoluteness of domination, but in performance of their many zealous Promises and Declarations made with such vehemencie of expression, as in the presence of God, and published in print to all the world; urging what a dishonour it would be to the whole Army, to have their faith so broken and violated, that though they might succeed in making out power and domination to some few of them, yet God could not be satisfied, nor their consciences be at peace. This was my way to most of them for a long time: but I may truely say, with David, They plentifully payd me hatred for my good will; and for my good counsel, (for so I believe time will prove it, though now they seem to ride on the wings of prosperity with their ill-gotten wealth and power) they layd snares to take away my life.

And in order thereunto, I with others being at the prosecuting of a Petition, one of their officious Spyes lays an accusation against me at the House of Commons bar; where clayming a Tryal at Law for any thing could be alleadged against me, and denying their Authority as to be my Judges, and for maintaining that I ought not to be tryed in any case but by a Jury of my Neighbourhood; For this doing, I was sent again prisoner to the Tower, where I continued for many months; and then again accounted a factious, seditious, and turbulent fellow, that owned no Authority, and that would have no Government; the cause being still the same, for that I would not renounce the Law my birthright, and submit to the wills of men in power, which as an English man I am bound to oppose.

But new Troubles appearing, and the great ones being in supposition they might once more need their unsatisfied friends, after a sore imprisonment, I obtained my liberty, and so much show of respects, as to have the damages (alotted for my sufferings under the Star-chamber sentence) ascertained: but not the least motion towards the performance of publike engagements, but only as troubles come, as about that time they did appear, upon the general rising & coming in of Hamilton, Goring, and the like, then indeed promises were renewed, and tears shed in token of repentance, and then all again embraced as Friends, all names of reproach cease, turbulent, and leveller, and all; and welcome every one that will now but help; and this trouble being but over, all that ever was promised should be faithfully and amply performed: but no sooner over, then all again forgotten; and every one afresh reproached, that durst but put them in minde of what they so lately had promised: yea, all such of the Army, under one pretence or other, excluded the Army, and so nothing appearing but a making way for Absoluteness, and to render the Army a meer mercenary servile thing, sutable to that end, that might make no conscience of promises, or have any sense of the Cause for which they were raised.

Perceiving this, I with others having proved all their pretences of joyning in an Agreement of the People to be but delusion, and that they neither broke the Parliament in pieces, nor put the King to death, in order to the restauration of the Fundamental Laws of the Nation whatever was pretended, but to advance themselves; I having been in the North about my own business while those things were done, and coming to London soon after, and finding (as to the Common Freedom) all things in a worse condition, and more endangered then ever, made an application to the Councel of the Army by a Paper, wherein were good grounds of prevention: but some there making a worse use thereof, interpreted the same a disturbance of the Army, earnestly moving they might get a Law to hang such as so disturbed them; affirming they could hang twenty for one the old Law could do.

Whereupon, we applyed our selves to the new purged Parliament, with a Paper called The Serious Apprehensions: unto which obtaining no answer, I endeavoured to have gotten hands to another Paper to be presented to the House, which was printed under the title of The second Part of Englands new Chains discovered wherein was laid open much of what since hath been brought upon the Nation of will and power; which at this day deserveth to be read by all that conceive me to be of a turbulent spirit, wherein they will finde the cause still the same, viz. my constant adherence to the known rights of the nation, and no other.

Upon this, I was searched out of bed and house by a party of horse and foot, in such a dreadful manner, as if I had been the greatest traitor to the laws and liberties of England there ever was; the souldiers being raised onely against such traitors, and not to seize upon men that strove for their restoration; but now the case was altered, and I must be no less then a traitor, and so taken, and so declared all over England, with my other fellow-sufferers, and all clapt up prisoners in the Tower, and after a while close prisoners, and then not only aspersed to be factious and turbulent, but Atheists, and Infidels, of purpose to fit us for destruction.

And though after a long and tedious imprisonment, they could never finde whereof legally to accuse us for any thing they put us in prison, yet scrap’d they up new matter against me, from the time they gave me liberty to visit my sick and distressed family; a thing heathens would have been ashamed of (but who so wicked as dissembling Christians?) and upon this new matter, small as it was, what a Tryal for my life was I put upon? what an absolute resolution did there appeare to take away my life? but God and the good Consciences of twelve honest men preserved me, and delivered me of that their snare; which smote them to the heart, but not with true repentance; for then had they ceased to pursue me: but just before that my Tryal, it is not to be forgotten, how a Declaration was set forth by the then Councel of State, signifying my complyance with young Charles Stuart, just as now was published in print upon the very morning I was brought to the Sessions-house: yea, and the same papers brought into the new Parliament, of purpose to bespeak and prevent the effect of those Petitions then presented in my behalf, and to turn the spirits of the House against me: so that nothing is more evident, then that the same hand still stones me, and for the same cause; and that I may be murdered with some credit, first they kill me with slanders: but as they in wickedness, so God in righteousness, and the Consciences of good men in matter of Justice, is still the same; and I cannot doubt my deliverance.

God and the Consciences of men fearing him more then men, freeing me from this danger, I endeavoured to settle my self in some comfortable way of living, trying one thing and another; but being troubled with Excise, wherein I could not sherk like other men, I was soon tired; and being dayly applyed unto for Counsel by friends, I resolved to undertake mens honest causes, and to manage them either as Sollicitor or Pleader, as I saw cause; wherein I gave satisfaction. And amongst others, I was retained by one Master Jos. Primate in a cause concerning a Colliery, which I found, though just, to have many great opposers, and chiefly my ingaged adversarie, Sir Arthur Haselrige, one that did what he could to have starved me in prison, seizing on my moneys in the North, when I had nothing to maintaine my self, my wife and children; this cause had many traverses between the Committee in the North, and the Committee for sequestration at Heberdashers-Hall.

And so much injustice appeared unto me to have been manifestly done, that I set forth their unworthiness as fully as I was able, and at length the cause being to receive a final determination before that Committee, I with my Client and other his councel appeared daily for many dayes, proving by undeniable arguments, from point to point, the right to be in Master Primate: but Sir Arthur Haselrige a Member of Parliament and Councel of State, and a mighty man in the North and in the Army, so bestirred himself, That when Judgement came to be given, it was given by the major Vote against my Clyent, quite contrary to the opinions of most that heard it, and to my Clients and my understanding, against all equity and conscience.

Whereupon, my Client by his petition appealed to the Parliament, wherein he supposeth that Sir Arthur had over-awed the Committee to give a corrupt Judgement. And being questioned, avowed the petition to be his own, and cleared me from having any hand therein. The house were in a great heat, and quarrelled my giving out the petitions before they were received by them, though nothing was more common; but order a rehearing of the whole matter by a large Committee of Members of the house in the Exchequer-Chamber, where notwithstanding the right appeared as clear as the Sun when it shines at noon-day, to be in my Client, to all by-standers not preingaged, yet whilst it was in hearing, long before the report was made, I had divers assured me I should be banished; and when I demanded for what cause, I could get none, but that I was of a turbulent spirit. It was strange to me, nor could I believe a thing so grosly unjust could be done, and provided nothing against it.

But upon the report of Master Hill the lawyer, most false as it was, the House was said to have passed Votes upon me of seven thousand pound fine, and perpetual banishment.

And upon the Tusday after called me to their Bar, and commanded me to kneel once, twice, and again; which I refusing, and desiring to speak, they would not suffer me, but commanded me to withdraw; and the next news I heard, was, that upon paine of death, I must within twenty depart the land: which though altogether groundless, yet finding all rumors concurring in their desperate resolutions, thought it safest to withdraw for a season, into some parts beyond the seas; and so I did, where I had been but a very short time, but I saw a paper intituled An Act in execution of a Judgement given in Parliament, for the banishment of Lieut. Cal. John Lilburne, and to be taken as a felon upon his return, &c. at which I wondered, for I was certaine I had received no Charge, nor any form of trial, nor had any thing there laid to my Charge, not was never heard in my defence to any thing.

Nevertheless, there I continued in much danger and misery for above sixteen moneths, my estate being seized by Sir Arthur: at length understanding the dissolution of the Parliament, I concluded my danger not much if I should return; and having some incouragement by my wife, from what my Lord General Cromwell should say of the injustice of the Parliaments proceedings, and of their (pretended) Act, I cast my self upon my native country, with resolutions of all peaceable demeanor towards all men; but how I have been used thereupon, and since, the Lord of heaven be judge between those in power and me; It being a cruelty beyond example, that I should be so violently hurried to Newgate, and most unjustly put upon my trial for my life as a Felon, upon so groundless a meer supposed Act, notwithstanding so many petitions to the contrary.

And now, that all men see the grosness of their cruelty and bloody intentions towards me, and having not consciences to go back, they now fill all mens mouthes, whom they have power to deceive, that I am of so turbulent a spirit, that there will be no quietness in England except I be taken off.

But dear Country-men, friends, and Christians, aske them what evil I have done, and they can shew you none; no, my great and onely fault is, that (as they conceive) I will never brook whilst I live to see (and be silent) the laws and rights of the Nation trod under foot by themselves, who have all the obligations of men and Christians to revive and restore them. They imagine, whilst I have breath, the old law of the land will be pleaded and upheld against the new, against all innovated law or practice whatsoever. And because I am, and continue constant to my principles upon which I first engaged for the common liberty, and will no more bear in these the violation of them, then I did in the King, Bishops, Lords, or Commons, but cry aloud many times of their abominable unworthiness in their so doing; therefore to stop my mouth, and take away my life, they cry out I never will be quiet, I never will be content with any power; but the just God heareth in heaven, and those who are his true servants will hear and consider upon earth, and I trust will not judge according to the voice of self-seeking ambitious men, their creatures and relations, but will judge righteous judgement, and then I doubt not all their aspersions of me will appear most false and causless, when the worst I have said or written of them and their wayes, will prove less then they have deserved.

Another stratagem they have upon me, is, to possess all men, that all the souldiers in the Army are against me; but they know the contrary, otherwise why do they so carefully suppress all petitions which the souldiers have been handing in my behalf? indeed those of the souldiers that hear nothing but what they please of me, either by their scandalous tongues or books, may through misinformation be against me; but would they permit them to hear or read what is extant to my vindication, I would wish no better friends then the souldiers of the Army; for I am certaine I never wronged one of them, nor are they apt to wrong any man, except upon a misinformation.

But I hope this discourse will be satisfactory both to them and all other men, that I am no such Wolfe, Bear, or Lyon, that right or wrong deserves to be destroyed; and through the truth herein appearing, will strongly perswade for a more gentle construction of my intentions and conversation, and be an effectual Antidote against such poisonous asps who endeavour to kill me with the bitterness of their envenomed tongues, that they shall not be able to prevaile against me, to sway the consciences of any to my prejudice in the day of my trial.

Frailties and infirmities I have, and thick and threefold have been my provocations; he that hath not failed in his tongue, is perfect, so am not I. I dare not say, Lord I am not as other men; but, Lord be merciful to me a sinner; But I have been hunted like a Partridge upon the mountains: My words and actions in the times of my trials and deepest distress and danger have been scanned with the spirit of Jobs comforters; but yet I know I have to do with a gracious God, I know that my redeemer liveth, and that he will bring light out of this darkness, and cleer my innocency to all the world.

FINIS.