John Lilburne, The Upright Mans Vindication (1 August 1653).

Note: This is part of the Leveller Collection of Tracts and Pamphlets.

Editor’s Introduction

(Placeholder: Text will be added later.)

Bibliographical Information

ID Number

T.238 [1653.08.01] John Lilburne, The Upright Mans Vindication (1 August 1653).

Full title

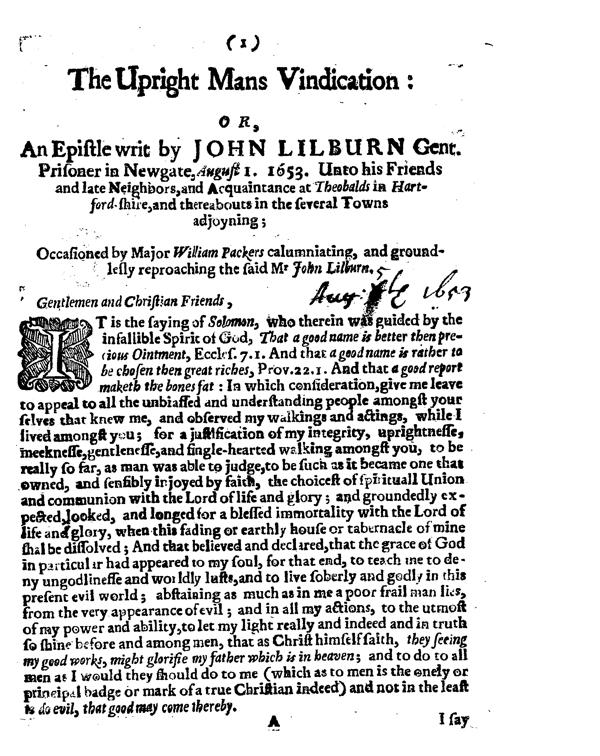

John Lilburne, The Upright Mans Vindication: or, An Epistle writ by John Lilburn Gent. Prisoner in Newgate, August 1. 1653. Unto his Friends and late Neighbors, and Acquaintance at Theobalds in Hartford-shire, and thereabouts in the several Towns adjoyning; Occasioned by Major William Packers calumniating, and groundlesly reproaching the said Mr John Lilburn.

This tract contains several parts:

- Address from Calis, 14 June 1653

- Statement from his trial held on 13-16 July 1652

- Letter to General Cromwell from Dunkirk, 2 June 1653

- A List of petitions made on his Behalf by others

- Postscript, 1 August 1653

- Lilburne's Answers

Estimated date of publication

1 August 1653.

Thomason Tracts Catalog information

TT2, p. 30; Thomason E.708 [22]

Text of Pamphlet

Occasioned by Major William Packers calumniating, and groundlesly reproaching the said Mr John Lilburn.

Gentlemen and Christian Friends,

IT is the saying of Solomon, who therein was guided by the infallible Spirit of God, That a good name is better then precious Ointment, Eccles. 7. 1. And that a good name is rather to be chosen then great riches, Prov. 22. 1. And that a good report maketh the bones fat: In which consideration, give me leave to appeal to all the unbiassed and understanding people amongst your selves that knew me, and observed my walkings and actings, while I lived amongst you; for a justification of my integrity, uprightnesse, meeknesse, gentlenesse, and single-hearted walking amongst you, to be really so far, as man was able to judge, to be such as it became one that owned, and sensibly injoyed by faith, the choicest of spirituall Union and communion with the Lord of life and glory; and groundedly expected, looked, and longed for a blessed immortality with the Lord of life and glory, when this fading or earthly house or tabernacle of mine shal be dissolved; And that believed and declared, that the grace of God in particular had appeared to my soul, for that end, to teach me to deny ungodlinesse and worldly lusts, and to live soberly and godly in this present evil world; abstaining as much as in me a poor frail man lies, from the very appearance of evil; and in all my actions, to the utmost of my power and ability, to let my light really and indeed and in truth so shine before and among men, that as Christ himself saith, they seeing my good works, might glorifie my father which is in heaven; and to do to all men as I would they should do to me (which as to men is the onely or principal badge or mark of a true Christian indeed) and not in the least to do evil, that good may come thereby.

I say you know my walking while I was with you to be in sincerity, peace, meekness, and uprightness, and in the demonstrations of true love and friendship, as became a Christian; which made me willing many times in publike in prayer amongst you, largely to spend some time, effectually to declare unto you, that infinitness of fulness, faithfulness, truth, and loving kindness, that I had found in the Lord of Hosts the Lord Jehovah; my long enjoyed, and long experienced enjoyed Rock of Salvation; who I often truly told you is and was long since, largely become my sensible lot, portion, joy and rejoycing; and was the onely single good that the soul of a Beleever could glory and rejoyce in; all earthly delights of riches, honour, greatness, pleasure, and all relations whatsoever in comparison of him, were but fading vanities, fly-blown, cobweb, moth-eaten contents and delights.

And yet in the midst of all these Declarations of mine amongst you, of the goodness and kindness of the Lord Almighty manifested unto my soul, nothing at the same time was more frequent and common amongst my great, potent, and seeming religious adversaries, then with confidence to brand me for an Athiest, a denyer of God and the Scripture. Just as Major William Packer, a great seeming-religious man amongst you now, doth (both to several of you and others, as my certain intelligence from some amongst your selves by Letters, &c. inform me) brand for an hypocrite, an apostate, and a great combining enemy with the Nations enemies beyond the seas against its welfare, peace and freedom; which although they be things my soul detests and abhors as I do the divel, and although I am confident no honest man in the world that really and experimentally knows me, can really in the least beleeve these things spoke against me to be true; or that there is any other ground or reason to report them, then the Machiavilian devises, of guilded pretended religious men, by craft, cunning, deceit, cruelty, policy and shedding of bloud, got into great places and power, which they would keep in their own hands arbitrarily by will and pleasure, to destroy all the lives liberties and properties of all the honestest and quick-sighted people of England at their pleasure. Yet notwithstanding, I judge my self obliged in duty and conscience to my self and the Nations welfare, to make an Apology unto you to open your eyes to see clearly through those foggy dark mists, that the said Major Packer would cunningly cast before your eys, for the keeping of his rich and great place and interest up, that hath raised him from the Dunghil, or a mean condition, to be one of the arbitrary and cruel Lords or unjust Taskmasters of the people of England. And I shal begin the said Apology with the inserting here my honest Addres from Calis, which the world for the reason declared in the 38 P. of my late printed Trial, never saw; the true Copy of which said Address, thus followeth.

For the Honourable the Councel of State sitting at White Hall in London, these present.

MAy it please you to vouchsafe me liberty to acquaint you, that being at Calis, by the means of our last Tuesday Post, I saw and read printed address unto you, made by some honest and well-minded people of Colster, as I have cause to judge them, by those honest (though somewhat too general) things that they desire of you in their said address, by which I perceive you are a kinde of a setled power in Engl. unto whom by that as the very first paper I have seen of that nature, I apprehend, the honest and rational people of England expect great matters from you, in reference to your assisting in the setling in a rational security of their laws, liberties and freedoms; the dear purchased and true price of all the late bloud and mony shed and spent in the late wars: In which regard, I am imboldened my self by these lines, to make this address unto you, although I must truly acquaint you, that upon my wifes comming to Bridges in Flanders to me, and fully informing me, that General Cromwel, and Major General Harrison with other Marshal men, had by force and violence dissolved the Parliament for their wicked, unrighteous and unjust actions, and being very confident that they never did an action (nor could) of more injustice, and unrighteousness, then their voting to banishment of me without ground or cause, and thereby also robbing me of my estate, and of all the comforts of this life, in which tyrannical Votes or sentence, I dare avow it (and upon my life in particulars maintain it) they have dealt more cruelly, more unjustly, more illegally, more unrighteously, and more harshly with me, then ever they dealt with the most professed enemy, that they have had in England, Scotland, or Ireland in arms against them, or any that they have supposed did aid, assist, or abet those that were in arms against them; Besides their destroying of the fundamental lawes and liberties of England contained in that most excellent Law the Petition of Right thereby, and so overthrowing all the ends that we pretended to fight for against the King, and thereby making us guilty of murdering all the people destroyed in the late Wars.

In all which considerations, &c. I was prevailed with the 14 of May last (new or Dutch stile) to write an address to the General and his Officers of the Army for my Pass, to return from my destroying compeld remaining beyond the seas, and pend it in rational, moderate, and respective phrases and terms, as by the Copy of it here enclosed in print doth appear: It being impossible in reason to imagine, that the Officers of the Army should deal so severely with the Parliament, their Lords, Masters, Creators and plentiful Providors for, and who were fenced about with several laws to make it treason in all or any of those that should but attempt or endeavour without their own free and voluntary consents to dissolve them, upon which very declared and printed statutes I my self was most severely prosecuted and arraigned two days together for my life as a Traitor, at Guild Hall in London in Octob. 1649. with the greatest and earnestest persuit, that ever was exercised upon a man; upon a bare pretence of my endeavouring to dissolve them, but by pening and printing (as was pretended, and if it could have been proved I had died as a Traitor for it) arguments and reasons, grounded upon the declared, printed, and published laws of England, and the received, acknowledged, printed and published Rules of reason, declared both in the late Parliament, and the Armies declarations: I say considering which, it was impossible in reason to imagine, that the General, &c. should as they have done, deal so severely with the Parliament for their wickedness, and oppression, and deny me a Pass upon my bare desire to them, being one of all men in the world, that the Parliament it self had dealt most wickedly and oppressive with, and banished in that barbarous and tyranical manner that they had done: And also considering that I am a man, that even in field have adventured my life with as much hazardousness, gallantry, and bravery, as any man whatsoever in the whole Army for those very principles, that they constantly in all their Declarations have declared, the undoubted birth right and inheritance of all the people of England, as well the poorest as the richest; And considering that for this 15 or 16 years together, I have been more then the General himself, and all the Officers in the Army put together in one, emptied from vessel to vessel, winnowed, sifted, and tried, gagged, whipt, pillored, ironed, arraigned for my life several times, imprisoned, close imprisoned, attempted to be starved, poysoned, violently murthered, pistolled, daggered, often divorced from enjoyment or sight of wife, children, servants, kindred, friends or any other relations; and have had my friends and acquaintance bribed, hired, and corrupted with large sums of money, and vast proffers besides, to lay snares, traps and gins, (to counterfeit my hand, to swear falsely against me) to take away my life. And all this hath been done unto me, for no other cause, ground, nor pretence of crime in the whole world, but onely and alone for standing for the foresaid laws, liberties, declared freedoms and birthrights of the people of England, that the Officers themselves in all their declarations, have declared themselves to be Patrons of, and standers for; as things of so much excellency and worth, as that they prized them above their lives and all other enjoyments that this world could afford unto them. The substance of all which they have centured in that excellent piece of theirs, as the sum of all their desires and endeavours, called, The Agreement of the People, which they themselves presented to the Parliament about 4 years ago, as containing the onely principles, mood and way, to establish in security for the future, the full and safe enjoyment of the liberties and freedomes of the commonly called, the free-born people of England.

Yea a man that by all provocation whatsoever, or courtings whatsoever (which hath been in both kindes many and great) could never be provoked nor induced to turn his back upon the said declared principles of liberty and freedom; nor in the day of the many straits of those, that stood for them, although he hath been never so injuriously dealt with even by divers of the chief pretenders to them. And to conclude, a man as to men for the worst of all his outward actions ever since he came to mans estate or knowledge (the frailties of provoked passion, or humane infirmity excepted, which the righteousest of meer men are not totally exempted from) that never to this day could justly be taxed or blemished with any the least outward baseness in any kinde whatsoever, that could in the least spot or stain his outward reputation; being confident according to the true fundamenaal laws of England for any thing whatsoever from his childehood to this very day acted by him, that justly can be laid to his charg, he may at the strictest legal bar of Justice in England, with clear and confident assurance of the safety of his life, limbs, liberty or property, bid defiance to all his adversaries though never so great) that he hath in the whole world. I say again upon all these considerations it could not rationally be imagined, but upon the Generals and his Officers first knowledge of my addresse to them, they would after they had by force dissolved the Parliament, immediately have given me a Passe to return from my causelesse and ruining banishment, and my poor credulous wife took her journey from me into England, with as much confidence immediately to obtain my longed for Passe, upon my foresaid Addresse, as she did believe, she should live after that to eat or drink.

But after a tedious delay, and a longing expectation, she with several of my friends, the last Dunkirk Post, sent me several Letters thither, dated the 27 of your May or old stile, which is the sixth of our Flemish present June, or new stile, in reading of all which at Dunkirk the last Sunday, by all which, I expresly find the General gives my wife good words, (which makes her believe him infinitely to be her friend) and that in the midst of the debate of my addresse, by the Councel of Officers, he was sent for by the Councel of State to come from the Councel of Officers to them, and that immediately after they rise, viz. the Officers or some of them, gave my wife, &c. this answer, viz. That they were not willing to break an Act of Parliament in a private case, but there would speedily be a power or a new Parliament, as they called it, that would do it, and some of great power, inquired or demanded, Whether if I came home I would be quiet or no, and others said mine was but a private businesse, and the Councel were so full of the publick affairs of the Nation, that they had scarce time to eat or sleep, and therefore I must be patient, quiet, and wait with contentednesse till a new Parliament.

At the reading of which I was even confounded and amazed in my understanding, and looked upon my wife and her stories of the Officers intended honesty and publick good to the Nation, as the perfectest artificial cheats, that ever was put upon me in the world, to deceive and cozen me, and that you that now sit as a Councel of State, with your Masters and Creators, viz. the General and his Officers, never hated nor disolved the Parliament, for any real hatred or disgust at them for any mischief, injustice, or Tyranny that they exercised upon the people of England (free (never since they were about 4 years ago declared a free people) in nothing else but bare name) but onely because they grew something stubborn and surly and would not be ruled meerly as school boyes, to act as the General and his great Officers (and you, now his and their substitutes) would have them, in which regard, great and glorious things was meerly pretended, but never intended for the peoples good, to break the Parliament in pieces, and totally dissolve them, that so you alone might get the power into your own hands, to do withall the lives, liberties, and estates of the people of England what you pleased, giving the people onely good words, untill you had rivited your selves fast in your power, by securing your selves so with force, that Julius Cæsar like, the General might stile and declare himself by a new name, but with a power in reality far above a King, as perpetual Dictator, or Lord Conservator of the peace of England, Scotland, and Ireland, and I confesse that the Generals words to my wife, and some of yours, together with the Officers, were so far from pleasing me, as they did her, that I clearly see by them I had ground to believe, that it is resolved privately by the General, I shall never so long as he lives, or at least so long as his power lasteth come into England again, because it was resolved by him (who I clearly then judged so rules and over aws you, that you nor the Officers durst not conclude to give me a Pass without fully and plainly knowing his will and pleasure) to drive on another intrest then in the least the peoples welfare, peace, safety, liberty, or freedome; all which to my utmost power, and the often apparent hazard of my life for many years together, I have been a constant and resolute patron too, and asserter of and never could be threatned there-from, nor in the least by Gold, Silver, or promotion (which hath times often enough sufficiently been proffered me) courted to forsake them, this being the onely and alone crime or true cause I have been hated, and almost often to death persecuted, by all great powerfull intrests, that have been great, and up in the government of England for many years together, and therefore now, and for this onely reason and none else, did I judge I must now be kept out from coming into England: the Generals good words to my wife, and yet denying my Pass (for so I absolutely judged the delay of it) made me immediately think of the 18 chapter of Nicholas Machiveli’s Prince, who is a man, (though through the grand corruptions of the age and place in which he lived, and the safety of his own life, was forced as may rationally in charity be judged to write in some kind of unhandsome disguises.) I must call for the excellency and usefulnes in corrupt times & places for his works sake, one of the most wisest, judicious, & true lovers of his country of Italies liberties and freedomes, and generally of the good of all mankind that ever I read of in my daies (of a meer man) who though he be commonly condemned with his Maximes and Tenents by all great state polititians, as pernicious to all Christian States, and hurtfull to all humane societies, yet by me his books are esteemed for real usefullnesse in my streits to help me clearly to see through all the disguised deceits of my potent, politick, and powerfull adversaries, above any one of all the human Authors in the world, that ever I read (which yet are very many) the reading and studying of which in the day of my great streights in contesting with the great Arbitrary powers in England, hath every way been as usefull, advantagious, necessary, and requisite to me, as a Compasse or Prospective glasse, can be to a master of a rich laden ship fallen into dangerous and unknown seas, where he is every hour in fear to be cast away and destroyed by dangerous sands, Rocks, or Pyrats: or as a pair of spectacles can be to a weak or decayed pair of eyes, in writing or reading that is compelled thereunto, and must do it and can get none to help him or do it for him, his book called his Prince (especially) if it were scarce to be got, being reputed by me of more worth than its weight in beaten Gold; for by my serious observing of his sayings, and the practise of most of those great men that in England I have been necessitated for the safety of my life to struggle with, I clearly find him, and the worst of his Maximes and Tenents, most practised by those great men in England, that most condemns him, and seems outwardly most to abhor and abhominate him, and yet would willingly (as the translator of his Prince, in his Epistle to the Reader saith) walk as Thieves do with close Lanthorns in the night, that so they being undescried, and yet seeing all, might surprize the unwary in the dark, and having him by me in my present travels, I immediately turned to his 18 chapter, which is contained in page 135, 136, 137, &c. where he speaks in these very words of Pope Alexander the sixth, in whose time himself lived, and who was the man or Pope that quarrelled with Henry the eight K. of England; Alexander the sixth saith he, never did any thing else then deceive men, and never meant otherwise, and alwaies found whom to work upon, yet never was there man would protest more effectually, nor aver any thing with more solemn Oaths, and observe them lesse then he; neverthelesse his cozenages all thrived well with him, for he knew how to play his part cunningly.

Therefore (saith he) is there no necessity for a Prince (or great man) to be indued withall those above written qualities, of pitty, faith, integrity, humanity and religion, but it behoves well that he seems to be so; or rather I will boldly say this, that having these qualities, and alwaies regulating himself by them, they are hurtfull, but seeming to have them they are advantagious, as to seem pitifull, faithfull, mild, religious, and of integrity, and to be so indeed provided withall thou beest of such a composition, that if need require thee to use the contrary, thou canst, and knowest how to apply thy self thereto; And therefore for a great man, but especially for one newly attained to his greatnesse; it beboves him (saith he) to have a mind so disposed, as to turn and take the advantage of all winds and fortunes, and as formerly I said, not for sake the good while he can, but to know how to make use of the evil upon necessity; And therefore let him (saith he) seem to him that sees and hears him, all pitty, all faith, all integrity, all religion, but there is not any thing more necessary for him to seem to have (saith he) then this last quality, (viz. to seem to be religious) because all men in generall judge thereof rather by the sight, then by the touch, for every man can come to see what thou seemest to be, but few men come to perceive and understand what thou art indeed and reality. For (saith he) if great men can feign and dissemble throughly, other men are so simple and yeeld so much to the present necessities, that he that hath a mind to deceive, shall alwaies find another that will be deceived, it being natural & common to the vulgar to be over-taken, with the apprehension and event of a thing, seldome or never rightly and truly weighing and examining the righteousnesse and Justice of the way and means, that great men use to attain to their ends.

And at the same time when I seriously considered the high pretences of the Major Generals Lambert and Harrison, to Justice and Righteousnesse in its purity and height, and the seeming contrariety of intrests betwixt them and their General: it made me seriously to think of what I have with a great deal of observation read (in those most excellent and famous Roman and Greek Historians Titus Livius and Plutark) of the Triumvery of Rome, consisting of Lepidus, Anthony and Augustus Cæsar, whose intrests the said Authors plentifully shews, in many things were as inconsistent with each other, as light is with darknesse, yet they all could agree in the main, viz. to make a sacrifice of each others choicest and dearest friends, that each other of them hated, or that they knew were or had bin great lovers of the liberties & freedoms of Rome, wch some 100 of years before then, had been one of the most famousest, most splendidist, and gloriousest Common-wealths in the whole world, by means of which; they not onely brought into their native Country and City most horrible and bloudy massacres and wars, but also totally subdued the liberties of their famous Common wealth, the people whereof could never regain them again to this day, although it be above 1600 years ago; and in conclusion the two eldest Triumveries, viz. Lepidus, and Anthony, were cheated and outed of their Government, and one or both of them of their lives, and the youngest, viz. Augustus Cæsar carried the bell away of the whole, and thereby made himself Emperour of the world, then in subjection to Rome, and the grounds and reasons of all these and many more considerations of my then perplexed conceptions, arise from your foresaid answer and speeches to my wife, &c. for can there be any difficulty or danger, or dishonour in it (if you were willing at all to let me come into England) to break a particular Act of Parliament in my particular case, of so high and palpable injustice, when you have accounted it no difficulty, danger, nor dishonour unto your to break, or at least all of you to approve of the breaking and dissolving, of that Parliament by force of arms, that made the said particular unjust and unrighteous Act, that were setled in their power, and secured in the continuance of it, by so many Acts of Parliament, divers of which made it Treason for any English man or men, so much as to go about, or but attempt, or indeavour to dissolve them without their own free consents, and which some of your very selves had been formerly active upon most strict penalties, even of losing the benefit of all Law, and being esteemed no Englishmen, to force the people to take an oath or ingagement to be true to them & to maintain & preserve them; so that I confess this piece of your answer was then such a riddle to me, as I could then no otherwise unfold it, then as is already before declared.

In the second place, as for that part of your Answer that tels her, there will speedily be a new Parliament that will relieve me, which very thing is a greater mystery to me then the former; because that in all the readings that ever I read in my life in divine or humane Authors, I reade but of three wayes of governing the world or the people thereof; the

First is, immediately by inspiration, and visible or evident command from God himself, and such was Moses Government, and the Judges of Israel; But I beleeve all of you nor none of you, will so much as pretend to so immediate and evident conversing with God as Moses and several of the Judges of Israel did, in your governing the people of England: if you do I hope you will shew the people of England (at least those that you judge honest, and have no more upon your own declared principles forfeited their hereditary birth rights, of injoyment of their fundamental lawes, liberties, and freedoms, then any one of you have done) your commission; And also carry them where they shall evidently hear the voyce of God speaking unto you, thereby infallibly guiding and directing you; after which, if then they will not beleeve your special assignation from God to be Englands Law givers, and Rulers, you will shew them your signes and wonders, that by the power of God therein, and thereby, you will confound and destroy as Moses did grand unbeleevers and rebellers; For without all these things, all your pretences to walk in Moses and the Judges arbitrary steps, in giving a law unto, and by will and pleasure governing the people of England, will be but meer impostorisms, for which you can expect from God and the people of England, no other recompence but what Impostors received in Moses time.

The second kinde of Government, or way of administration of Government, is by Conquest (and such was Nimrods the mighty Hunter) which is so mightily condemned, even by the declarations of your own selves for a beastly, inhumane and unnatural government, as nothing can be more; and therefore although at present I have not your printed papers or declarations at Calis by me, yet by the strength of my memory I dare avow, that in one of your printed papers, published by you to justifie your late proceedings against the late executed King. Conquest is called a title or government fit to be amongst Bears and Woolves, but not amongst men, and say I much less Christians, but much less of all other, amongst the pretended refined’st of Christians, as you would have men judge you to be. Reade but your late Acts, Declarations and printed papers about the Trial of the late King upon this very subject, to make you now abominate of governing by Conquest or any other way like it; especially that of the Officers of the Army of the 16 of Novemb. 1648 dated at St. Albons, and John Cook your Soliciter Generals stated Case of the King. And as to the nature and extent of implied and tacid trusts, read in the first part of the Parliaments book of Declarations pag. 150, 151. And the Armies Declaration of the 14 of June 1647. made immediately after their League, Covenant, and Contract made and signed at New market and Triplo heaths, and printed in their Book of Declarations, about pag. 44, 45. And can any man be so irrationally brutish as to imagine and think, that those that you account honest people in England, whom I am sure with my individual self, have adhered with lives and estates to this very day to their fundamental laws and liberties, and to the primitivest and best of the Parliaments and Armies Declarations, that ever they will be so fellonious to themselves, as to assist and enable you with their own power, with their own estates, with their own lives and blouds to enable you to set up that, that shall destroy them and all thats near and dear unto them if you please, and when you please; but such a thing for any thing I can apprehend, is that Parliament that you tell my Wife you intend speedily to set up, which I cannot in the least discern is to be chosen and entrusted by the people, or any part even of those, that have in all things as firmly as any of your selves adhered unto this very day, and ventured their lives and fortunes to maintain their fundamental laws and liberties, published and declared in the best of the Parliament and Armies declaration. But a Parliament picked and culled by your selves, that have not with all the Officers of the Army (the honest people of Englands payed and hired servants, who therefore ought not by your owne principles, and for quoted Declarations to act for their wo in the least, but onely and alone for their weal and good) any other pretence to set up such a Parl. but the right of Conquest (which yet will be one of the most vildest assertions in the world for you to maintain, against my self and thousands and ten thousands more, that have assisted you, and never acted against your declared and honest principles by which you ingaged to maintain our fundamental laws and liberties, in reference to the free and secure injoyment of our lives liberties and properties) which by your foresaid declared principles and declarations can be no other, but a Parliament of force, will, and pleasure, and thereby the perfect badge of Conquest, and by consequence by your own acknowledgment, onely fit to make lawes amongst Bears and Wolves, but not amongst men, and what justice or relief I may expect from such a Parliament is beyond my apprehension.

The third way of governing or way of administration of Government, is by a Nation, or company of peoples mutual agreement, or contract, or long setled, well approved of, and received customs (there being not in the least in either of the Old or New Testament, any prescript form of Civil or earthly politick Government left by God, to be binding and observed, by all Nations and people in all ages and times: men being born rational creatures, are therefore left by God in or to the choice of their Civil Government to the principles of reason (all which centers in general in these two, viz. do as you would be done to; and ye shall not do evil that good may come thereby) and to chuse such a government as themselves or their chosen trustees please to impose upon themselves, under which they may in a rational security live happily, and comfortably, which the very Charter of Nature doth intayl, or intitles all men under all Civil government unto, and such was our Government in England in a great measure under the establishment of Kings, who as in your Declarations and the late Kings own confession it is justly avowed, and truly acknowledged, was to govern the people of England, according to the known and declared fundamental laws (and no otherwise) made by common consent in Parliament, or national, common or supreme Councels, and to grant such laws for the future, as the folk or people (for the good and benefit) in National common Councels or Parliaments should chuse; which I dare avow was with all its imperfections, in the constitution of it, the best, rationalest, and for the people of England most securest of declared and setled Governments now extant in the whole world (our change for onely a nominal free State, or Commonwealth hither toward, I will maintain it upon my life in aboundance of particulars against the ablest man or men in England, being as yet onely for the worse, but not in the least to the generality of the people for the better) the late Parliament of Lords and Commons, being according to the declared law of England called and summoned by the Kings Writ, in whose power by law, it was at his pleasure to dissolve them, till such time as in the year 1640. he past an Act of Parliament in full and free Parliament, That they should sit during their own pleasure, and not be dissolved but by their own consents, all which ancient, legal, much approved of, long setled government, being absolutely and totally dissolved by you, there can now (according to your foresaid principles, and the principles of nature and reason) by no power or persons whatsoever in England be summoned, called, or chosen a new Parliament, but by a new and rational contract and agreement of the people of England; especially (and at least upon your own foresaid principles) made amongst those that have adhered with their lives and fortunes to their own fundamental declared laws and liberties, according to the rational and just principles of the Parliament and Armies best of Declarations. And therefore a Parliament called by you in any other way as you pretend, now to be in a Commonwealth, in my shallow apprehension can be no other, but the perfect demonstration of absolute Conquest, which is a title or government fit onely for Beares and Wolves, but not for men (much less for Englishmen) by your own forementioned printed Confession and averment. The constant effects of which, can in reason and experience be nothing els but murther, shedding of bloud, war, misery, poverty, famine, pestilence, and utter desolation (to now more then ever divided poor England;) from which good Lord deliver poor England, my dear and entirely beloved Native Country (for whose welfare and freedom as for many years by past (to the best of my poor understanding) I have been ready (and I hope whilest I breath shall never cease to continue willing) to become a sacrifice.) And I also beseech God to cause the eyes of the wise and judicious ordinary people and common souldiers thereof, seriously and constantly to be fixed in their thoughts upon the miseries of those unexpressible murthers, devastations and desolations that were occasioned and brought upon poor England, by the Conquest of the Romans (and Julius Cæsar as their first Captain) and some hundreds of years after by the conquest of the Saxons, and several yeares after that by the Conquest of the Danes, and some hundreds of years after that by the conquest of the Normans under the leading of William the Conquerour, afterwards admitted King of England about 600 years ago; to the people or inhabitants of which he three several times took formal or solemn oaths inviolably to maintain their laws and liberties, all which the said people and private souldiers may particularly reade in our English Chronicles, but especially in that excellent History or Chronicle of famous and laborious John Speed) that so their souls may for ever loath the exposing of themselves and their poor Native Countrey, with their fundamental laws, and rational and just liberties, to the conquest and unlimited will of any forreign or domestique power in the world, though never so specious in their religious pretences of godliness and piety. All men by reason of Adams fall and his own corruption thereby, being naturally if left to their own wils and pleasures, more brutish, bloudy, and barbarous, then the brutishest or savagest of wilde Beasts (that seldom or never prey upon and devour their own kinde) may plentifully be seen, even in the civil, moralised, and much refined Commonwealth of Rome, in the bloudy proscriptions, massacres and barbarisines of savage Marius and Sylla; when they got absolute and uncontroulable sword-power into their own hands, and the bloudy and most unmatchable Plot and Conspiracy of Catiline and his accomplices. Therefore I have read amongst the wisest and rationallest speeches, of the high esteemed for reason and justice, Parliament men at the beginning of the late Parliament, that they do avow in their long since printed Speeches for constant successive Parliaments; that all rational, just, imperial, and wise Law-givers, or Law-makers in the making of Laws, must proceed with a sinister opinion of all Mankinde, as supposing it impossible for a just man to be born, either to have them to be executed upon, or to be an executer of them, and therefore should proceed to make them so rational, just and exactly strickt, as that as little as possible in reason, should be left to the discretion, will or pleasure of the Administrator, or he upon whom they are to be administred; so that as much as rationally may be, they should become a rational and equitable bridle and curb upon them both, to keep them off (for their own safety and well being sake) from incroaching upon one anothers rights, or destroying of one anothers brings.

In the third place, As to that demand, whether if I come home I will be quiet or no? I answer;

First, I am as free born as any man breathing in England (and therefore should have no more fetters then all other men put upon me) And I have actually done as much in my poor contemptible sphere for the real preservation of the FUNDAMENTAL LAWS, liberties, and freedoms of England (held out in the best and choisest of the Parliaments and Armies Declarations) as any man breathing in England, I dare with confidence and truth avow it, what ever he be, excepting never a one; nor never coveted nor desired either gain or riches therefore, but onely my bare common share in the enjoyment of the felicity and happiness that would redound to the universality of the people in general, by a rational setling and for the future securing to them the free enjoyment of their lives, liberties, and estates; and that so I might truly and solidly upon good grounds, call that my own, which with the sweat of my browes, the labour of my hands, or industry or honesty of my brains or tongue, I had justly got: And that it might not be taken in the least from me, but onely in a common equal just way, for a common end, and good; or for a transgression of a rational and just declared law, reaching the universality as wel as me, and that I might truly and upon rational grounds call my wife (that great and chiefest earthly delight of many men) my own, and the children that I got by her (or at least confidently beleeve so) my own, and not have me taken from them nor them from me by will and pleasure as often hath been practised upon me already, which give me leave truly to aver and avow, is more the propper issue of the Government of Bears and Wolves then of rational and just men.

Secondly, I answer, it is ridiculous and foolish to ask me such a question; if honesty, justice, righteousness, and the true freedom and liberty of the Nation be in the least your real intentions: for if I come home, and finde you, as before is expressed, it is my interest (which is that great thing that swayes and rules the world, and all the men therein) not onely to be quiet with you, but bazardously venter my life, and all that ever in this world I have, in common with you, for the good of the whole Nation; And give me leave with confidence, and as much modesty as I can to aver it, my interest is none of the meanest in England; but even amongst the hobnails, clouted shooes, the private souldiers, the leather and woollen Aprons, and the laborious and industrious people in England, is as formidable as numerous, and as considerable as any one amongst your whole selves not excepting your very General; (let him but lay down his sword and become disarmed as I am) a cleerer proof, for the manifestation of which, cannot be given in the world, then was given at my fore-mentioned late Tryal at Guild-Hall London, in Octob. 1649. where the Officers of the Army, and in manner the whole Parliament, and Councel of State, and Magistrates of London, were universally my bitter enemies; yet at my deliverance from death by the Verdict of my honest Jury, the private Troopers of the very Guard there upon the very place made their Trumpeters (as from good hands I have been informed) in spight of their Officers sound Victoria; themselves shouting and discharging of their pistols for joy of my deliverance from complotted death: yea, and some of their Comrades begun to build bone-fires at Fleet bridge, which all my then bloody Judges, nor their Officers of the Army, that to their Lodgings guarded them for fear of the peoples rage and fury, with many Troopes and Companies of Horse and Foot, could not prevail with the souldiers, either of Horse or Foot, to put out the said bone-fires: may, nor none of the Parliament, nor Councel of State, nor Lord Major, nor Court of Aldermen of London, durst none of them appear to hinder the people from filling the streets of London in a wonderful manner with bone-fires that very night of my deliverance, thousands and ten thousands of the people of London (and the Countries of England) openly by there redoubled shoutings, feastings, drinkings, and other open and apparent rejoycings, manifesting as much visible joy and gladness at my then deliverance, as ever the famous old Grecians did at the free restauration of their ancient laws, liberties, and freedoms, by the famous General Titus Flaminius (that delight and desire of Mankind, as in History he is stiled) after he had beaten Philip King of Macedon in pitcht battel, with a great slaughter, who held the said Grecians in bondage, under the nation of friendship, and being their Protector; which rejoycing was wonderful great, as Plutarch in his famous History declares: the Epitomy of which is expressed in my late printed Letter to Col. Henry Martin, entituled, John Lilburn revived.

Yea, abundance of the middle sort of the people of London, openly avowed and appointed a day of Thanksgiving, where, as I remember, six or seven persons spake, and prayed, and praised God publikely for my deliverance from death; as being one of their stout Champions for their Liberties and Freedomes: And from the place where it was performed, we marched in great Troops and Companies to a great Feast to the Kings Head Tavern in Fish street; which was so considerable a Dinner or Feast, as that the Master of the House, (as from some of the Stewards themselves I have been informed) demanded of the Stewards about 12 or 14 li. for bare fouling of his Table-linning; besides the charges of Wine, and other Necessaries; and forced them to pay him, as I remember, above 6 l. for the use of his Linning: so that if you intend honesty to the Nation, and seriously consider what is before truly expressed, its no way in he world for your interest and benefit (especially, being at bloody wars with forreign people) so to contemn and despise me, by keeping me out of England, and thereby endeavouring as much as in you lies, to make me from a present friend that now counts you, to become your open and professed enemy to defie you, and to do you all the mischief, that an inraged and greatly provoked metled and nimble Spirit can invent or devise, which may in short ime be fatal to some, or all of your particulars, though not to the whole Nation.

Besides, in keeping me out of England, and thereby continuing my unjust banishment, you justifie and take the guilt upon your own shoulders of all the Parliaments wickedness and unrighteousness acted upon me, in passing for nothing, and without all Law (as in my fore-mentioned printed Address to the General, &c. of the 14th of May last, I have punctually evinced) that most wicked Sentence, which they say concerns me. And so you ill honour the beginning of your Government, and give small hopes to any understanding impartial man in England, to expect any real good from your future Government.

Thirdly, I answer, in case I come home and will not be quiet, if you intend to be just and honest, what need you fear me; for I am sure my unquietness in such a case can do you no hurt at all; but mischief, ruine, and destroy sufficiently my self. Besides, I was never in my life so ridiculously mad, and so foolish, as ever in my life to go about such a thing, all the sufferings or unquietness that ever I was ingaged in, in my life, against any sort or kind of your Predecessors in power (yea even the unjustest of them) was never so much as once acted by me, until I was forcibly compel’d by their high injustice exercised upon me thereunto, and even through meer necessity and force from them, being absolutely necessitated to do it or perish And Machiavil that wise and shrewd man, most truly shews, that to be a just ground for a publique War; for in his notable Exhortation to free Italy, his Native Countrey, from the Government of the Barbarians (or tyrannical Usurpers) in the latter end of the Prince, pag. 215. saith, That War is just, that is necessary; and those Arms are religious, when there is no hope left other where but in them. And I do avow, I cannot remember, that ever in all my dayes, since I was a man, I begun a Quarrel with either great or little man in my life; or that either in any quarrel, ingagement, or contestation that I was in, that ever I refused any just, rational, moderate, or legal wayes and meanes, to come to a speedy and final end of it; but have always been an earnest and constant pursuer of a fair & just accomodation, in all the contests I was ingaged in in my self. And therefore must here with the greatest of confidence avow it, for the greatest falshood, and scandal in the world, laid constantly upon me by my malicious and great enemies, when they avow me to be a man of an unquiet, unstable, and troublesome spirit; that man not being in the whole world, I am confident of it, that can justly instance in one thing, that ever I begun a quarrel or contest in my life; or that ever I took up the Buckler against any great man or interest in England till I was compel’d by necessity; which before both God and Man justifies an open War betwixt Nation and Nation; and therefore much more justifies me in all the contests that ever I had in my life; or hereafter may have with you (which from my very soul I desire to avoid by all means possible) if you continue in your denial to let me come home, and breath in the ayr of the land of my Nativity, (unto which I have as great, as true, and as legal a right as any one of your selves, or any other man whatsoever now breathing in it) which to do, is the earnest desire of my heart.

The fourth thing I have to answer, is, that it is said mine is but a private business, and the Publique takes up all your time: To which I answer: Can there be a more publike businesse in the world, then the doing of justice, and relieving the Oppressed; and redeeming the captive, or unjustly banished: I am sure the Parliament at the very first beginning of their filling on the 3d of Novemb. 1640. made it their work at the very first desire, and relieved me and my fellow captives, then even at the very first knowledge of our address to them, and got their honour and glory amongst the people by it; which in the day of their great distress, became more then a shield and buckler unto them for their preservation.

In the second place I answer, that the injustice done to me in my banishment, is so evident and palpable to all men whatever that have eys in their heads to see, that the debate of my business needs take up no longer time then the bare reading of my Addresse, and granting an Order upon it.

The last thing I have to answer is, that in regard of the fore-mentioned parts of your Answer, I must be quiet and patient.

To which I answer, it is impossible I should: First, because my banishment, and Sir Arthur Haslerigs cruelty, hath rob’d me of all my Estate, and rich Employment besides; so that I protest as in the presence of the Almighty, in a land of strangers, I have not one peny to buy me bread, but what I am forced to borrow. Secondly, I am already in divers of hundred of pounds debt; and how long in reason considering thereof, I shall be able to subsist, I leave it to a rational and impartial man to judge; and to be beholden to the charity or benevolence of friends, is a thing so ugly in my estimation; a thing so subject to be hit in future time in a mans teeth, and brings with it so much slavery and captivity of a mans Reason and Understanding to the wils and pleasures of those that a man in such a case is beholden to, that I loath and abhor the very thoughts of it more then death: And having in all my banishment to this day not been beholden, to the best of my remembrance, for the gift of a farthing, or its worth, to all the kindred or friends I have in England, Scotland, and Ireland (saving for two pieces of Gold, as two tokens, that my wife at her last being with me brought me from two friends, and for a little Rundlet of Sack sent me in Winter by another, with some Ribbonds for shooe-strings by another, and some friendly entertainments at Amsterdam by some friends now in England) and I am resolved to keep from being in that kind beholden to my friends, till absolute, and pure, and unavoidable necessity compels me to cry out openly, bitterly, mournfully, and publikely, in printed Briefs, both to God and Man, of all Nations and Conditions for aid, help, and relief. Thirdly, I answer: How can patience and quietnesse be expected by you from me, in my condition, when my life hath been, and yet is (for any thing I know to the contrary) in continual danger, even by the hired and pentioned Agents of some of those that were very zealous in my unjust and tyrannical banishment; one of which, an Irish-man, or Rebel, and named Hugh Rily, I hear is now in England, who in the face of the main Court of Guard at Dunkirk, without the least provocation or affront, presented several times his pocket pistol to me, and sware most bitter Oaths. (in the presence of several honest Englishmen as Witnesses) God dam and sink him if he did not immediatly pistol me: Upon which, I complaining to some of the Magistrates of Dunkirk, their chief Bayliff, in his own person, and by divers of his Officers, searched for him to punish him, for the breach of their Law, for offering to disturb the quiet of their Garrison. But he knowing his own notorious guilt, fled and hid himself: whereupon the chief Bayliff himself seized upon the said Rily’s Portmantle, and all other things belonging to him, that he could lay his hands of: Which Rily I am able sufficiently to prove is one of the bloodiest, falsest, cowardest, and villainous Rogues in the world: of whose tyrannical carriage at his late being in Rebellion in Colchester against you, you by Mr Beacon (a man as I am informed of good repute in Colchester) at whose house the said Rily was quartered, may be sufficiently informed. And yet he was one of Mr Scots pentioned and hired Agents, as by some of his letters which I have intercepted, I certainly know, and have too much cause to think he hired him in Flanders, either to murther me himself, or get it done by others. And yet this wicked Villain, as my Wife writes me word, hath that impudence to petition against me, which she looks upon as one of the greatest Reasons to hinder my desired Pass.

These, and the like considerations, noble Gentlemen, perplexing my head, my heart, and my spirit, at the reading of my Letters the last Sunday at Dunkirk, compelled me in that condition to write severall private letters the last Post ever into England; One of which its possible may come to your knowledge, and thereby very much displease you: In which consideration upon my coming to Calis, and finding and reading the said Colchester Address unto you, I was thereby incouraged and imboldened notwithstanding that to pen this Addresse unto you.

By which I do most heartily and earnestly intreat you to do your selves that right and honour, and me that justice, as to grant me my speedy Pass, in security, to return into England; for which I shall really and truly be obliged to subscribe my self,

Your obliged friend, in all just things

to serve you,

From my present Lodging

at Callis, Saturday June

14. 1653. Dutch stile.

JOHN LILBURN.

And along with this Address I sent several Instructions; the last part of which being most pertinent to evince the thing I drive at, viz. That my affection to my Native Countrey, all the time I was beyond sea, was one and the same in truth and reality, without staggering or wavering in the least) that ever it was in any time in my abode in England; and that my love, and the manifestation of it to my Native Countrey, hath been great while I was in England, at least sometimes; I think Major Packer, nor none of his great Masters, my greatest Enemies, will deny in the least: And that it was the same to the height all the time I was beyond the seas, I shall in part appeal to the latter end of my said Instructions; which I am confident hath such Propositions in them for Englands good, as never was made in England by a private man; nor I believe cannot be immagined which way to be brought or made practick, by any private man in England besides my self; And although they are in print in the 38 and 39 pages of my late printed Tryal at the late Sessions, upon the 13, 14, 15, 16. of July last; yet shall I judge it very proper and pertinent to the purpose in hand, to insert the copy here, which thus followeth.

FIfthly, I beseech you have a special care of spies, false Brethren, Neuters, Dissemblers, Ambo-dexters, and sneaking quench-coals, any of which in the least, as soon as you apprehend to be among you, take special notice of them, and at least desire them to depart out of your meeting. And this with confidence, if your resolute and unwearied endeavours bring me home, upon my reputation and life I will make it evident and apparent to your chosen Commissioners you shall authorize to discourse with me about what I have to say to you, that my time, brains and interest, in my compulsive being beyond the seas, hath been spent to as much advantage, for the good in general of my Native Country, and the people thereof, as ever man in the worlds was, that was forced from his Native Soil, and particularly, if I can be permitted to come home in peace and quietness, I do hereby engage and binde my self, at my utmost peril, demonstratively, rationally and evidently, to lay down such Rules, wayes and means, as if speedily and effectually persued, shall undoubtedly make England to be either honoured, courted, and respected by all neighbouring Princes and Commonwealths round about her (even Holland it self) or else undoubtedly shall make her to be feared and dreaded of all those that refuse to do the former, and that this shall be done by honourable and just ways in every particular.

2. I will lay down such honest, just, rational and feasible grounds, as if speedily and effectually persued in the eye of reason, shall undoubtedly make England in Trade and Traffick in one year, or two at the most, more to flourish in Trade and Traffick, then ever it did before the late Wars; yea, even to equallize and go beyond Amsterdam and Holland in its greatest glory, which in their true and natural effects shall much increase the people and inhabitants of England (and in particular shall make thousand and ten thousands of Watermen more then now they have) which are and must be, now the Bulworks of England) shall raise the price of Land, and by consequence of all commodities produced by it, the Loans of which at the present is like to break the poor Husband-man, and in a very short time shall ease the people of three quarters at least of their present charges in Taxes and Excize; and for the future, the middle sort of people shall not bear half so much as they do now in proportion; nor the richest be opprest at all, nor compelled to pay above their proportion, which with Gods blessing in a very few moneths shall produce to whole England such peace and plenty, as shall evidently yielde an unoppressive way and means to give to every Souldier now in Arms in England, &c. and settle upon him and his heirs for ever, without alienation, so many Acres of Land as shall be worth ten pound, or fifteen pound sterling a year; and upon every poor decayed house keeper (like the Law Agraria amongst the Romans) shall settle for ever so many Acres of Lands, as shall be worth after the first years husbandry, to him and his heirs for ever, five pound or sixe pound sterling per year: and shall also provide for all the old and lame people in England, that are past their work, and for all Orphans and Children that have no estate nor parents, that so in a very short time there shall not be a Beggar in England, nor any idle person that hath hands or eyes, by meanes of all which, the whole Nation shall really and truly in its Militia, be ten times stronger, formidabler and powerfuller then now it is: all which if you get me home in safety, and thereby free me from the murtherous dealings of Mr Thomas Scot, and his cursed and blood thirsty Associates, if by evident reason and demonstration I do not make all the abovesaid things apparent to your Commissioners chosen by you to discourse with me upon the premises, let me dye, and be esteemed for ever by you all, the veriest Cheat and Rogue that ever in your lives you had to deal withall: Therefore, as you love your own welfare, and the welfare and happinesse of the Land of your Nativity, act vigorously, stoutly, industriously, and unweariedly night and day, for the preservation of your own interest, liberties, and welfare, very much concerned in your speedy getting me a Pass: for which I shall account my self as much obliged to you all that are vigorous actors in it, as ever man did to a generation of men in the world: so with my honest and truest love to you all, I rest,

Yours faithfully, if his own,

From my present Lodging at the

Silver Lyon in Calis, this

present Saturday, June 4th

1653.

J. LILBURN.

And because in the latter end of my fore-going Address from Calis Pag. 19. there is mention made of one Letter being written from Dunkirk, which probably may come to the knowledge of the Councel of State, which will not please them, and seeing the said Letter is constantly hit in my friends teeth, as my information tels me by Major Packer himself, and other of his great Masters, as if it were fully fraught with treason, felony or the highest manifestation of malice and hatred to my native Country, that possible can be expressed; and though since my coming into England I have made it my studied work, rather to heal and close up breaches betwixt me and my potent adversaries, then to make them in the least wider, and therefore in my three first Addresses to the Councel of State, I did in sincerity and truth, proffer them what ever in my imagination, could be proffered by a rational, peaceable, just and honest man: but yet notwithstanding that, my life and innocent bloud ever since hath been with that eagerness persued; and stil is ordered to be persued, and no ear at all in the least will be given to any of those many Petitions of thousands and ten thousands well affected people, that hath constantly been endeavoured to be presented to the Parliament for me, that I am confident I may justly say, the persecution raised and persued against my innocent life, is farre beyond the persecution in bloudy Queen Maries time, that was raised and persued against the righteous and just Martyrs, or any of them: For in the first place, she dealt in that particular so justly with them, that she made them known and declared Laws to walk by, and to take heed of, before that ever she went about in any the least kinde to punish them, but no such thing in the least is there in my case; although our Governours pretend to be a thousand times more righteous and godly then she was, and yet in actions even in my present particular, are abundantly more abhominable in wickedness and thirsting after innocent bloud then she was; And besides, we have in England been fighting (pretendedly for the securing of our Lawes and Liberties) for this ten or eleven years together, and yet fall far short of bloudy and wicked Queen Mary in outward justice and righteousness.

Who secondly, would never have any of the righteous Martyrs condemned, but she would have them to have due process of Law, and fair hearings and trials, and their crimes and offences laid unto their charges, and either proved against them face to face, or confessed by them: But no such things at all in the least is there in my case; for I never had any due process of Law in my life about my banishment, nor no crime in the least laid unto my charge, nor never saw accuser, nor witness against me; nor never was asked the question what I could say for my self? nor never permitted to speak one word for my self, and yet Major William Packer and his great pretended Religious Masters, General CROMWEL, Major General HARRISON, and Major General DESBOROUGH, are the onely men that principally persue my life upon this score to have it taken away from me; which is a deliberated and a consulted action of higher tyranny I am confident of it, then ever was acted by the greatest Tyrannical King, that ever since the Creation of the World Ruled in England, that ever in the least pretended to govern by Law and Justice.

Nay I do hereby avow it, and will pawn my life in every circumstance to make it good, that the present dealing with me by the General and his Confederates aforesaid, is an action as full of injustice in it self, as it would be for the present Parliament to say;

Resolved upon the Question,

That all the Men, Women, and Children in England, besides our selves and our Wives and Children, beforthwith hanged, drawn and quartered:

And then when such a Vote is past, endeavour with all their might to put it in execution without mercy or compassion: For I am endeavoured to be destroyed and hanged as a Felon, without in the least having any action of Felony committed by me, laid unto my charge; or any other crime whatsoever, but that my name is John Lilburn, and that I am in the Land of my Nativitie, and continue as honest as ever I was in my dayes: in all which considerations premised, I am forced to insert a Copy of my Letter to the General from Dunkirk, which is rendred to be so strange a kinde of monstrous piece, and so unlike an Englishman, that hath the least spark of affection to his Native Countrey in him, and judge my self a thousand times more able to defend every line and clause in it now I am alive (which by all meanes the General intends shall not be long) then any other man whatsoever is, after my death; which is now so violently persued to be perfected and consummated: And therefore the Copy of the said Letter thus followeth.

For the Right Honorable Oliver Cromwel Esq; Gen. of the forces of England, these at Whitehall present.

My Lord,

THough I know it hath been your constant designe to pursue my life like a Partridge upon the Mountains, for these six or seven yeers together, with all the unhansome and unmanlike ways of ignobleness and unworthiness, that possible could be acted or invented, with any seeming pretence or colour. And though now and then in the midst thereof, you have seemed to carry an outward face of respect unto me, yet it hath always been with a double heart, and onely at those times, when your own wickedness and unrighteousness, and turning your back upon all your declared promises and principles, hath brought you into such streights, snares, and dangers, as that in the eye of Reason the Kings party and the Presbyterians have had you fast in their mouse-traps, your own life and safety, and nothing else, then forcing and compelling of you to houl and cry like the great hypocrites in the days of old, mentioned in the Old-Testament, to me or such sturdy fellows as I was, and also to acknowledge your own baseness, and for the future, promise the performance of honest and just things, on purpose to engage our helping hands, to be conjoyned (in the day of your great straights, brought upon you by your own constant unworthiness, and habituated falseness) to yours: either to help you through your present streights, or at least to sit still, without any prosecuting revenge of you in your streights: which by reason of your constant meeting with ingenuous spirits amongst those sturdy people, whom with my self you on set purpose (at Putney) reproachfully baptized, or maliciously nick-named Levellers, and men that minded in their own thoughts the publick interests more then their own particular concernments. And because the King and his party was never so wise for their own ends and advantages as to make that fair and rational use of those signal advantages that they often had by your folly and madness, to hold out publickly rational security to the body of the people of England of all interests, for their future enjoyment of their lives, liberties, and estates from the fear of arbitrary destruction at pleasure; but rather chose to act the contrary, by flights, contempts, scornes, and abuses: by means of which, you have enjoyed constant and valiant helps to free you from the dreadful fear of your many blots, even by those persons that you have formerly highly disobliged; from which you have been no sooner delivered, but you have immediately been like the dog that returns to his vomit again, and with the greatest detestation in the world, have immediately endeavoured the destruction of your very preservors; which I having so many known and certain experiments of, as I have, and of those bloody ways and means you have pursued the total destruction of me, my wife and children, (three of whom, as the chiefest earthly instrument, I dare aver rationally to evince you have murthered and been the death of) and of your activity and zeal (if I may believe the relation of an able and rational member of the late Parliament that heard you in the house) to appear openly in the late Parliament as the principal man to have me banished (in which unrighteous and unjust sentence, I do with confidence here avow it, no honest, nor just man, could have a hand or finger in approving of it, or acting in it) and thereby to be robbed of my estate, and not now lest worth a groat to buy me brend, and thereby to be deprived of the comfortable enjoyment of my wife, and tender babes: (the greatest delight formerly to me in the whole earth) and of all other comforts of this life, yea to breath in the ayr of the Land of my nativity, yea and by you causlesly exposed to an exilement amongst worse then barbarians for baseness, and most detestable falseness: even amongst my contriving, plotting, lying, and bloody enemies; set on, on purpose to destroy me, as I have too much grounded cause to believe, by large gifts and pensions, flowing originally by your instructions to your late vassal and slave Tho. Sto, late Secretary of State, one of the most basest, [Editor: illegibles words] and rotten whoremasterly villains in the whole world.

In all which regards, it was below me, and inferior to me, and inconsistent with my interest and reputation in many respects, to write of late in any respectful way unto you, without a kinde of compulsive force and necessity; but in regard first for that enderedness of affection that I owe to her, whom I formerly entirely loved as my own life: though your late barbarous tyrannical dealing with me, hath exposed her to so much folly and lowness of spirit in my eys, in some of her late childish actions, as hath in some measure, produced an alienation of affection in me to her. Yet by reason of her perswasive and urgent importunity in the first place, and 2. many ways for my own politick ends, and 3. to leave you without all manner of excuse in the eys of rational men, was I induced and in a manner compelled, upon the 14 of May last, to write an Address into England in a respective way, particularly to your self, who (to deal plainly with you) I then did and still do believe, was so engaged in interests, wrath, and malice in your own heart, as rather sooner (as I have often told my poor simple wife) to hazard your life and well-being, then ever suffer me again to breath in Englands Ayr, in peace, security and quietness; In which regard, I told her, if she were wife, she would willingly permit me, according to my own well and rationally grounded genius, to scuffle neither with small nor great, but you alone, as the chief author of my banishment, and chief Patron and true earthly causer of all the grand mischiefs and Tyranny acted in poor England: yet though I could not draw her to that, I so penned my said Address, as that if upon the speedy delivery of it my Pass were denyed or delayed, I could in my own thoughts make sufficient use of the publishing and printing of it; and therefore confidently believing you would be like that grand Tyrant Pharoah hardened in heart to your own destruction, I got 1000 of them in these parts printed in Dutch and English, and immediately sent another copy to Paris to be printed in French and English there; and also sent another copy to Amsterdam, to be printed in Dutch and Latin there: which I hope if it be not already done, it will be speedily done; and another copy by another hand then my wife, to be printed, besides the original I sent to London; but my wife having heard of it, hath most irrationally hindered it, so that now I must take some other course to get it printed, whether she will or no; let the issue be good or bad I care not: and fully understanding by this Post, by six or seven several Letters, that my desired Pass is delayed; which I have cause by the length of time, to take for an absolute denyal, and also have too just cause to judge that you alone, are the principal cause of it; in which regard, not to complement with you, which now I scorn, but in my own imagination to leave you amongst all rational men the more without excuse, I send you these lines, upon which most particularly, I do most heartily and earnestly entreat you (who I know is able with the bare lifting up of your finger if you please) to send me speedily without any the least further delay, my Pass, to return into the Land of my nativity, from my causless, illegal, and unjust banishment: and if when I come into England, you have any thing to say to me, for any evil I have done you, either in word or action, or any way else, I do hereby engage to give you real satisfaction face to face, either first as a Christian, or secondly as a rational man, or thirdly as a sturdy (though very much wounded and cut) fellow, that dare yet subscribe himself,

From Dunkirk Monday the

2. of June, 1653. Dutch or

New stile.

Honest and stout JOHN LILBURNE,

that neither fears death nor hell,

men nor Devils.

A second piece that I intended when I begun this to have produced, to evince my strong and earnest affection to my native country, and its liberties and freedomes, and my constant study to indeavour its welfare, even while I was beyond the seas, whilst I was daily strugling with the complotted designes of my death, by the barbarous, wicked, and most vile agents of Master Thomas Sco, the Generals Secretary of State; and as I am informed is yet his bosome, cabinet, and darling friend, although in all manner of wickedness and baseness, he is so vile and putrified, that I am confident, honest Job would have scorned to have set so unworthy a man with the dogs of his flock. I say the second piece that I intended to produce, was an Epistle writ by me, from Bridges in Flanders, the last of October last English stile, unto Colonel Martin, which is printed beyond Sea, at the latter end of a book, Intituled John Lilburn revived; and which hath so many clear demonstrations in it of my true affection to my Native Country, and its welfare, and prosperity, and that in the way of a Commonwealth rightly constituted; that by no understanding man that shall read it, can I (I am confident of it) in the least be judged, a man in league with any manner of Royallist in the world, to do England or its liberties and freedoms the least hurt in the earth: but it would make this Epistle much too long, and take up too much of my precious time to look after, my second tryal drawing on so nigh at hand, as Wedensday come seven dayes is; and that with that fury and rage, that I understand the General, &c. drives it on with; and therefore I shall here earnestly desire some of the seriousest amongst you, for your further satisfaction in this point, to make a journey to London, to one very well known to the most, if not all of you, and that is Master William Kissin, one judged even by my great adversaries sufficiently well-affected to the present interest that now rules; and ask him but these two questions: First, whether since my abead in Flanders, &c. beyond the seas, he did not receive divers letters from me? Secondly, desire to know of him the particular contents of those letters; and particularly, whether divers of them were not fill’d with as clear demonstrations of my real affection to the welfare of England, as any letters possible could be filled, and whether they did not serve him often to use for the good of England or no.

But now my friends, should I put you upon a serious consideration of the publike wayes of Major William Packer, and his great masters; truly I think I might truly aver, that all the histories of the whole world, will not afford a generation of men, that in printed Declarations have promised more to a people of good, and in actions done less then they; there being not the least suitableness in the world, betwixt their publike Declarations and their Actions; for although it was onely Law and Liberty that declaredly we fought to secure for these eleven together against the King, yet I would now but ask any ingenious man in England this question, Whether there be any law in reality, liberty, or propriety left in England, but the Generals will and pleasure; who although he was but a mean man a while ago, and now at most but the peoples daily hired and paid mercenary servant; Doth he no pick and cull Parliaments at his pleasure? and when those that he hath left hath given him and his associates out of that that is none of their own many thousand pound lands of inheritance a yeer; doth he not at his pleasure pluck them up by the tools? although by his consent and seeking, they had hem’d themselves about with divers laws, to make it treason for any man or men of England, whatsoever, but to indeavor to raise force against them to dissolve them; and doth not he and his Officers when they have created necessities of their own making, without the least shaddow of Parliamentary authority, expresly against the tenour of the Petition of Right, and all our fundamental laws, most arbitarily, as if the people of England were the most absolute conquered, invassalized slaves upon the face of the whole earth, lay a tax of sixscore thousand pound a moneth upon the people, to fill his pockets and his fat associates? and doth he not do more then all the foregoing Kings and Tyrants of England durst do, in chusing by himself and such of his meer mercenary Officers joyned with him as he pleaseth, a Parliament or Legislators of whom he pleaseth, to make laws for the people without asking their consents in the least? Sure I am, the Chronicles and Records of England declare, that it was one of the Articles for which King Richard the second was discrowned, and lost his crown, That by himself and his own authority, he had displaced but some Burgesses of the Parliament, and had placed such other in their roomes, as would best fit and serve his own turn. See William Martins Chronicle of the last Edition, folio 128. Article 21.

And in Article, 22. He is accused for causing certain laws in Parliament to be made for his own gaine, and to serve his own turn.

And in Article the 20. He is accused for over-awing the Members of Parliament, that they durst not speak their minds freely.

And as for our lives, it was Master Peters averment to me long since in the Tower, we had no law left in England; and it was his averment yesterday, being Sunday the last of July, in the presence of the General, before some of my acquaintance, two of which aver to me, that he averred to them, we have now no law left or in being in England, so that it seems the Generals will must be our rule to walk by, and his pleasure the taker away of our lives, without any crime or charge in law laid unto our charges, or any defence or speaking for our selves permitted to us, or required of us; which is absolutely and perfectly my case, as appears by the Votes of Parliament of the 15. Jan. 1651. printed in my Trial: Therefore Judge seriously of your own, and consider impartially, whether now in your present condition, under your great high and mighty pretended Christian master and lawless Lords, You are not in a worse condition then ever any of our forefathers were, under their Heathen, Pagan, Papal, Episcopal, or Presbyterian governours; having now to deal with a company of mighty pretended Christians and Saints, who yet make it their trade to get their bread and livelihood, by shedding the blood, and butchering of their neighbours and country-men (they know not wherefore) whose tables are dayly richly spread and deckt with the price of the blood of the people of England, and their back and houses richly clothed and adorned with the same, whose laws and liberties they have destroyed and confounded, although they receive their daily wages and subsistence from them, and that for no other publikely owned and declared cause, but for the preserving of them.