John Lilburne, Thomas Prince, Richard Overton, The Picture of the Councel of State (4 April, 1649).

Note: This is part of the Leveller Collection of Tracts and Pamphlets.

Editor’s Introduction

(Placeholder: Text will be added later.)

Bibliographical Information

ID Number

T.187 [1649.04.04] John Lilburne, Thomas Prince, Richard Overton, The Picture of the Councel of State (4 April, 1649).

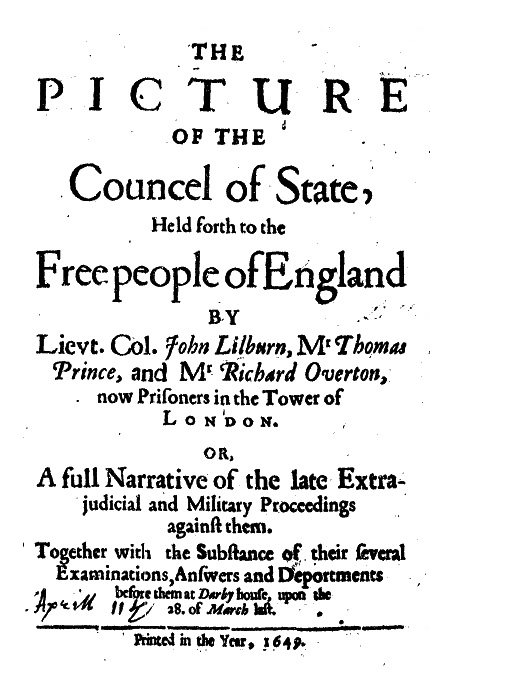

Full title

John Lilburne, Thomas Prince, Richard Overton, The Picture of the Councel

of State, Held forth to the Free people of England by Lieut. John Lilburn,

Mr. Thomas Prince, and Mr. Richard Overton, now Prisoners in the Tower of London,

Or, A full Narrative of the late Extra-judicial and Military Proceedings against

them. Together with the Substance of their several Examinations, Answers and

Deportments before them at Darby house, upon the 28. of March last.

Printed in the Year, 1649.

The Tract contains the following parts:

- John Bradshaw, The Narrative of the proceedings against Lieut. Coll. John Lilburn

- Lilburn, To the Lieut. of the Tower of London.

- Lilburn, Postscript

- Overton, The Proceedings of the Councel of State against Richard Overton, now prisoner in the Tower of London

- Postscript

- Prince, The Narrative of the Proceedings against Mr Thomas Prince

Estimated date of publication

4 April, 1649.

Thomason Tracts Catalog information

TT1, p. 735; Thomason E. 550. (14.)

Text of Pamphlet

The Picture of the Councel of State, Held forth to the Free People of England, By Lieutenant Coll. John Lilburn, M. Thomas Prince, and M. Richard Overton. The Narrative of the proceedings against Lieut. Coll. John Lilburn, thus followeth.

ON WEDNESDAY the 28. of March 1649 about foure or five a clock in the morning, my Lodging at Winchester-house was beset with about a hundred or two hundred armed men, Horse and Foot, one of which knocking at my chamber doore, I rise and opened him the doore, and asked him who he would speak with, and what he would have? He replyed, he was come to take me Prisoner, where upon I demanded of him to see his Warrant, he told me he had one, but had it not here, but as soon as I came to Pauls I should see it; I told him if he walked by the rules of Justice, he ought to have brought his Warrant with him, and to have shewed it me, and given me leave to have coppied it out, if I had desired it; but divers of the foot Soldiers rushing into my roome at his heeles, I desired him to demeane himself like a Gentleman, and not with any incivilities affright my children & family, for if it were nothing but my person he would have, I would but make me ready and go along with him without any more a doe, whither he would carry me, for his power of armed men was beyond my present resisting, or power to dispute, so I desired him and another Gentleman with him to sit down, which they did, and when I was almost ready to go, I demanded of him whether it would not fully satisfie his end, in my going along with him and one or two more of his company in a boate, and I would ingage unto him as I was an Englishman, there should be no disturbance to him by me, or any in my behalf, but I would quietly and peaceably go with him, wherever he would have me; but he told me no, I must march through the streets with the same Guard that came for me, I told him I could not now dispute, but it would be no great conquest to lead a single captive through the streets in the head of so many armed men, who neither had made resistance, nor was in any capacity to do it, and coming down staires into the great yard, I was commanded to stand till the men were marshalled in Rank and File, and two other Prisoners were brought unto me, viz. my Land-lord, Mr. Devennish’s two sons, but for what they knew not, nor could imagine; So away through the streets the armed Victors carry us, like three conquered Slaves, making us often halt by the way, that so their men might draw up in good order, to incounter with an Army of Butter-flies, in case they should meet them in the way to rescue us their Captives from them; so coming to Pauls Church, I there meet with my Comrade Mr. Prince, and after imbraces each of other, and a little discourse, we see our acquaintance M. William Walwin marching at the head of another Partie as a captive, and having understood that our being seised as Prisoners was about a new addresse by way of Petition to the Parliament, intituled the second part of Englands new chains discovered. We could not but wonder at the apprehending of M. Walwin about that, he having for some moneths by past (that ever I could see, or hear of) never bin at any of our meetings, where any such things were managed; But Adjutant General Stubber that was the Commander of the Party coming then to view, I repaired to him, and desired to see his Warrant by vertue of which his men forced me out of my bed and habitation, from my wife and children, and his Warrant he produced, which I read, he denying me a coppy of it, though both there and at White-Hall I earnestly demanded it as my right, the substance of which so neere as I can remember, is from the Committee, commonly stiled the Councel of State, to Authorise Sir Hardresse Waller, and Collonel Edward Whalely, or whom they shall appoint, to repaire to any place whatsoever, where they shal heare Lieut. Coll. John Lilburn, and M. Prince, M. Walwin, and M. Overton are, them to apprehend and bring before the Councel of State, for suspition of high Treason, for compiling &c. a seditious and scandalous Pamphlet &c. And for so doing, that shal be their Warrant.

And in the same paper is contained Sir Hardress Wallers, and Col. Whaley’s Commission or Deputation to Adjustant General Stubber, to apprehend M. Walwin, and my self; who with his Officers, dealt abundantly more fairly with us, then I understand Lieut. Col. Axestell dealt with M. Prince and M. Overton, From which Lieut. Col. if there had bin any harmony in his spirit to his profession, abundance more in point of civility, might have bin expected, than from the other, though he fell much short.

But when we were in Pauls Church-yard, I was very earnest with the Adjutant General, and his Ensigne that apprehended me (as I understood by the Adjutant he was) that we might go to some place to drink our mornings draughts, and accordingly we went to the next dore to the School-house, where we had a large discourse with the Officers, especially about M. Divinish sons, we understanding they had no warrant at all to meddle with them in the least, nor nothing to lay to their charge, but a private information of one Bull their fathers tenant, between which parties there is a private difference, we told them, we could not but stand amazed, that any Officer of an Army durst in such a case apprehend the persons of any Free-man of England, and of his own head and authority, drag him or them out of his house and habitation, like a Traytor, a Thief, or a Rogue, and they being ashamed of what they had done to them, at our importunity, let both the yong men go free. So away by water we three went to White-hall, with the Adjutant General, where we met with our friend M. Overton. And after we had staid at White-hall till about 4. or 5. of the clock in the afternoon, we were by the foresaid Adjutant carried to Darby house, where after about an hours stay, there were called in Lieu. Col. Goldegne, a Coalyard keeper in Southwark, and as some of good quality of his neighbours do report him to have bin no small Personal Treaty man, and also Capt. Williams, and M. Saul Shoe-maker, both of Southwark, who are said to be the Divels 3. deputies, or informers against us; and after they were turned out, I was called in next, and the dore being opened, I marched into the Room with my hat on, and looking about me, I saw divers Members of the House of Commons present, and so I put it off; and by Sergeant Dendy I was directed to go neer M. Bradshaw, that sate as if he had bin Chairman to the Gentlemen that were there present; between whom, and my self, past to this following effect.

Lieut. Col. Lilburn (said he) here are some Votes of Parliament that I am commanded by this Councel to acquaint you with; which were accordingly read, and which did contain the late published and printed Proclamation or Declaration, against the second Part of Englands New Chains discovered, with divers instructions, and an unlimitted power given unto the Councel of State, to find out the Authors and Promoters thereof. After the reading of which, M. Bradshaw said unto me, Sir, You have heard what hath bin read unto you, and this Councel having information that you have a principal hand in compiling and promoting this Book, (shewing me the Book it self,) therefore they have sent for you, and are willing to hear you speak for your self.

Well then M. Bradshaw, said I, If it please you and these Gentlemen to afford me the same liberty and priviledge that the Cavaliers did at Oxford, when I was arraigned before them for my life, for levying War in the quarrel of the Common-wealth, against the late King and his Party (which was liberty of speech, to speak my mind freely without interruption) I shall speak, and go on; but without the Grant of liberty of speech, I shall not say a word more to you.

To which he replyed, That is already granted you, and therefore you may go on to speak what you can or will say for your self, if you please; or if you will not, you may hold your peace, and with draw.

Well then (said I) M. Bradshaw, with your favour, thus. I am an Englishman born, bred, and brought up, and England is a Nation Governed, Bounded, and Limitted by Laws and Liberties: and for the Liberties of England, I have both fought and suffered much: but truly Sir, I judge it now infinitely below me, and the glory and excellency of my late actions, now to plead merit or desert unto you, as though I were forced to fly to the merit of my former actions, to lay in a counter-scale, to weigh down your indignation against me, for my pretended late offences: No, Sir, I scorn it, I abhor it: And therefore Sir, I now stand before you, upon the bare, naked, and single account of an Englishman, as though I had never said, done, or acted any thing, that tended to the preservation of the Liberties thereof, but yet, have never done any act that did put me out of a Legal capacity to claim the utmost punctilio, benefit, and priviledge that the Laws and Liberties of England will afford to any of you here present, or any other man in the whole Nation: And the Laws and Liberties of England are my inheritance and birth-right. And in your late Declaration, published about four or five daies ago, wherein you lay down the grounds and reasons (as I remember) of your doing Justice upon the late King, and why you have abolished Kingly Government, and the House of Lords, you declare in effect the same, and promise to maintain the Laws of England, in reference to the Peoples Liberties and Freedoms: And amongst other things therein contained, you highly commend and extol the Petition of Right, made in the third yeer of the late King, as one of the most excellent and gloriest Laws in reference to the Peoples Liberties that ever was made in this Nation, and you there very much blame, and cry out upon the King, for robing and denying the people of England the benefit of that Law, and sure I am (for I have read and studied it) there is one clause in it that saith expresly, That no Free-man of England ought to be adjudged for life, limb, liberty, or estate, but by the Laws already in being established and declared: And truly Sir, if this be good and sound Legal Doctrine (as undoubtedly it is, or else your own Declarations are false, and lyes) I wonder what you Gentlemen are, For the declared and known Laws of England knows you not, neither by names, nor qualifications, as persons endowed with any power either to imprison or try me, or the meanest Free-man of England, And truly, were it not that I know the faces of divers of you, and honour the persons of some of you, as Members of the House of Commons that have stood pretty firm in shaking times to the Interest of the Nation, I should wonder what you are, or before whom I am, and should not in the least honor or reverence you so much as with Civil Respect, especially considering the manner of my being brought before you, with armed men, and the manner of your close sitting, contrary to all Courts of Justice. M. Bradshaw, it may be the House of Commons hath past some Votes or Orders, to authorise you to sit here for such and such ends as in their Orders may be declared: But that they have made any such Votes or Orders, is legally unknown to me, I never saw them. Its true, by common Fame you are bruted abroad and stiled a Councel of State, but its possible common Fame in this narticular may as well tell me a ly as a truth: But admit common Fame do in this tell me a truth, and no ly, but that the House of Commons in good earnest have made you a Councel of State, yet I know not what that is, because the Law of England tells me nothing of such a thing, and surely if a Councel of State were a Court of Justice, the Law would speak somthing of it: But I have read both old and new Laws, yea all of late that it was possible to buy or hear of, and they tell me not one word of you, and therefore I scarce know what to make of you, or what to think of you, but as Gentlemen that I know, I give you civil respect, and out of no other consideration: But if you judge your selves to be a Councel of State, and by vertue thereof think you have any power over me, I pray you shew me your Commission, that I may know the better how to behave my self before you. M. Bradshaw, I will not now question or dispute the Votes or Orders of the present single House of Commons, in reference to their power, as binding Laws to the people; yet admit them to be valid, legal, and good, their due circumstances accompanying them: yet Sir, by the Law of England let me tell you, what the House Votes, Orders, and Enacts within their walls, is nothing to me, I am not at all bound by them, nor in Law can take any cognisance of them as Laws, although 20. Members come out of the House, and tell me such things are done, till they be published and declared by sound of Trumpet, Proclamation, or the like, by a publike Officer or Magistrate, in the publike and open places of the Nation; But truly Sir, I never saw any Law in Print or writing, that declares your power so proclaimed or published, and therefore Sir, I know not what more to make of you, then a company of private men, being neither able to own you as a Court of Justice, because the Law speaks nothing of you; nor as a Councel of State, till I see, and read, or hear your Commission, which I desire (if you please) to be acquainted with.

But Sir, give me leave further to aver unto you, and upon this Principle or Averment I will venture my life and being, and all I have in the world; That if the House had by a Proclaimed and Declared Law, Vote, or Order, made this Councel (as you call your selves) a Court of Justice, yet that proclaimed or declared Law, Vote, or Order, had bin unjust, and null, and void in it self; And my reason is, because the House it self was never (neither now, nor in any age before) betrusted with a Law executing power, but only with a Law making power.

And truly Sir, I should have lookt upon the people of this Nation as very fooles, if ever they had betrusted the Parliament with a law executing power, and my reason is, because, if they had so done, they had then chosen and impowred a Parliament to have destroyed them, but not to have preserved them, (which is against the very nature and end of the very being of Parliaments, they being (by your own declared doctrin) chosen to provide for the peoples weale, but not for their wo) And Sir, the reason of that reason is, because its possible if a Parliament should execute the Law they might doe palpable injustice, and male administer it, and so the people would be robd of their intended extraordinary benefit of appeales, for in such cases they must appeale to the Parliament, either against it self, or part of it self, and can it ever be imagined they will ever condemne themselves, or punish themselves, nay, will they not rather judge themselves bound in honour and safety to themselves, to vote that man a Traytor and destroy him that shall so much as question their actions, although formerly they have dealt never so unjustly with him; For this Sir I am sure is very commonly practised now a dayes, and therefore the honesty of former Parliaments in the discharge of their trust and duty in this particular was such, that they have declared, the power is not in them to judge or punish me, or the meanest free-man in England, being no Member of their House, although I should beat or wound one of their Members nigh unto their dore, going to the House to discharge his duty, but I am to be sent in all such cases to the Judge of the upper Bench, [Margin note: See 5. H. 4.6. II H. 6. Ch. II see also my plea against the Lords jurisdiction, before the Judges of the Kings Bench called the Laws Funeral. Pag. 8, 9. and my grand Plea against the Lords jurisdiction, made before M. Maynard of the house of Commons; and the foure imprisoned Aldermen of Londons plea against the Lords jurisdiction, published by M. Lionel Hurbin 1648.] unto whom by Law they have given declared rules, and direction in that particular how to behave himself, which are as evident for me to know as himself, now Sir, if reason and justice doe not judge it convenient that the Parliament shal not be Judges in such particular cases, that is of so neere concernment to themselves, but yet hath others that are not of their House that are as well concerned as themselves, much lesse will reason or justice admit them to be judges in particular cases, that are farther remote from their particular selves, and doth meerly concern the common wealth, and sure I am Sir, this is the declared Statute Law of England, and doth stand in ful force at this houre, there being I am sure of it no law to repeale it, no not since the House of Commons set up their new Common-wealth. Now Sir from all this I argue thus, that which is not inherent in the whole, cannot by the whole be derived, or assigned to a part.

But it is not inherent, neither in the power nor authority of the whole House of Commons, primarily and originally to execute the Law, and therefore they cannot derive it to a part of themselves.

But yet Sir with your favour, for all this I would not be mistaken as though I maintained the Parliament had no power to make a Court of justice, for I do grant they may errect a Court of justice to administer the Law, provided that the Judges consist of persons that are not Members of their House, and provided that the power they give them be universal, that is to say, to administer the law to all the people of England indefinitely, and not to two or three particular persons solely, the last of which for them to do is unjust, and altogether out of their power: And therefore Sir, to conclude this point, It being not in the power of the whole Parliament to execute the Law, they can give no power to you their Members to meddle with me in the case before you; For an ordinary Court of Justice (the proper Administrator of the Law) is the onely and sole Judge in this particular; and not you Gentlemen, no nor your whole House it self.

For with your favour M. Bradshaw, the fact that you suppose I have committed (for till it be judicially proved, (and that must be before a legal Judge that hath cognisance of the fact) or confessed by my self before the Judge; it is but a bare supposition) is either a crime, or no crime; A crime it cannot be, unless it be a Transgression of a Law in being, before it was committed, acted, or done; For where there is no Law, there is no Transgression. [Margin note: 2. Rom. 4.15. See the 4. part of the L. Cooks Institutes, Ch. I high Courts of Parl. fol. 14. 35. 37. See also my printed Epistle to the Speaker. of the 4. April, 1648. called The prisoners plea for a Habeas Corpus, p. 5, 6. and Englands Birth-right, p. 1, 2, 3, 4. and the second edition of my Epistle to Judge Reeves, p. 11, 12, 13, 14, 15. and M. John Wildmans Truths Tryumph, p. 11, 12, 13, 14. and Sir John Maynards Case truly stated, called The Laws Subversion, p. 9, 13, 14, 15, 16. 38.] And if it be a Transgression of a Law, that Law provides a punishment for it, and by the Rules and method of that Law am I to be tryed, and by no other whatsoever, made ex post facto.

And therefore Sir, If this be true, as undoubtedly it is; then I am sure you Gentlemen have no power in Law to convene me before you, for the pretended crime laid unto my charge; much less to fetch me by force out of my habitation by the power of armed men: For Sir, let me tell you, The Law of England never made Colonels, Lieut. Colonels, Captains, or Souldiers, either Bayliffs, Constables, [Margin note: 3. See the Petition of Right, in the 1. C. R. and my book called the Peoples Prerogative, p. 67, 68, 69, 70.] or Justices of the Peace: And I cannot but wonder that you should attach me in such a manner as you have done, considering that I have all along adhered to the Interest of the Nation against the common enemy (as you call them) and never disputed, nor contemned any Order of Summons from Parliament, or the most irregularest of their Committees, but alwaies came to them when they sent for me, although their warrant of summons was never so illegal in the form of it, and I have of late in a manner de die in diem, waited at the House dore, and was there that day the Votes you have read, past, till almost twelve a clock, and I am sure there are some here present (whose conscience I believe tells them, they are very much concerned in the Book now before you) that saw me at the dore, and stared wishfully upon me as they went into the House, and I cannot but wonder there could be no Civil Officer found to summon me to appear, but that now, when there is no visible hostile enemy in the Nation, and all the Courts of Justice open, that you (that have no power at all over me) must send for me by an hundred or two hundred armed Horse and Foot, as though I were some monstrous man, that with the breath of my mouth were able to destroy all the Civil Officers that should come to apprehend me, Surely I had not endeavoured to fortifie my, house against you, neither had I betaken my self to a Castle, or a defenced Garison in hostility against you, that you need to send an hundred or two hundred armed men to force me out of my house, from my wife and children, by four or five a clock in the morning, to the distracting and frighting of my wife and children: Surely, I cannot but look upon this irregular, unjust, and illegal hostile action of yours, as one of the fruits and issues of your new created Tyranny, to amuse and debase my spirit, and the spirits of the People of this Free Nation, to fit me and them for bondage and slavery. And Sir, give me leave further to tell you, that for divers hundreds of men that have often bin in the field with their swords in their hands, to encounter with hostile enemies, and in their engagements have acquitted themselves like men of valour, and come out of the field conquerors, for these very men to put themselves in Martial Array against four Mise or Butterflyes, and take them captives, and as captives lead them through the streets, me-thinks is no great victory and conquest for them, but rather a diminution to their former Martial Atchievements and Trophies: And therefore to condude this, I do here before you all, protest against your Power and Jurisdiction over me, in the case in controversie, And do also protest against your Warrant you issued out to apprehend me; And against all your martial and hostile acts committed towards me, as illegal, unjust, and tyrannical, and no way in Law to be justified: Further telling you, that I saw most of the Lord of Straffords arraignment, and (if my memory fail me not) as little things as you have already done to me, were by your selves laid to his charge, as acts of Treason; For which I saw him lose his head upon Towerhill as a Traytor: And I doubt not for all this that is done unto me, but I shall live to see the Laws and Liberties of England firmly setled, in despite of the present great opposers thereof, and to their shame and confusion: and so M. Bradshaw I have done with what I have now to say.

Upon which M. Bradshaw replyed, Lieut. Col. Lilburn, you need not to have bin so earnest, and have spent so much time in making an Apologetical defence, for this Councel doth not go about to try you, or challenge any jurisdiction to try you, neither do we so much as ask you a question in order to your tryal, and therefore you may correct your mistake in that particular. Unto which I said, Sir, by your favour, if you challenge no Jurisdiction over me, no not so much as in order to a tryal, what do I here before you? or what do you in speaking to me? But Sir, seing I am now here, give me leave to say one word more, and that is this, I am not onely in time of peace (the Courts of Justice being all open) fetcht & forc’t out of my house by multitudes of armed men, in an hostile manner, & carried as a captive up and down the streets, contrary to all Law and Justice, but I am by force of Arms still kept in their custody, and it may be, may be intended to be sent to them again, who are no Guardians of the Laws of England, no nor so much as the meanest Administrators or Executors of it, but ought to be subject to it themselves, and to the Administrators of it: And truly Sir, I had rather dy, than basely betray my liberties into their Martial fingers, (who after fighting for our Freedoms, would now destroy them, and tread them under their feet) that have nothing at all to do with me, nor any pretended or real civil offender in England: I know not what you intend to do with me, neither do I much care; having learned long since to dy, and rather for my Liberties, than in my bed: Its true, I am at present in no capacity effectually to dispute your power, because I am under Guards of armed muskettiers, but I entreat you, If you will continue me a prisoner, that you will free me from the military Sword, and send me to some Civil Goal; and I will at present in peace and quietness obey your command, and go. And so I concluded, and was commanded to with-draw, which I did, and then M. William Wallin was called in, and while he was within, I gave unto my comrades M. Prince, and M. Overton, and the rest of the people, a summary account of what had past between me and them: and within a little time after, M. Walwin came out again, and M. Overton was called in next: and at M. Walwins coming out, he acquainted us what they said to him, which was in a manner the same they said to me, and all that he said to them was but this, That he did not know why he was suspected. To which M. Bradshaw replyed, Is that all you have to say? And M. Walwin answered, yes. So he was commanded to withdraw.

And after M. Overton was come out, M. Prince was called in, and after he had withdrawn, they spent some time of debate among themselves, and then I was called in again, So I marched in sutable to my first posture, and went close to M. Bradshaw, who said unto me to this effect: Lieut. Colonel Lilburn, This Councel hath considered what you have said, and what they have bin informed of concerning you, and also of that duty that lies upon them by the command of the House, which enjoyns them to improve their utmost ability to find out the Author of this Book, and therefore to effect that end, they judge themselves bound to demand of you this question: Whether you made not this Book, or were privie to the making of it or no?

And after some pause, and wondering at the strangeness of the question, I answered and said, M. Bradshaw, I cannot but stand amazed that you should ask me such a question as this, at this time of the day, considering what you said unto me at my firsfabeing before you, and considering it is now about eight yeers ago since this very Parliament annihilated the Court of Star-Chamber, Councel bord, and High Commission, and that for such proceedings as these. [Margin note: 4. See the Acts that abolished them, made in the 16. C.R. printed in my Book, called The peoples Prerogative, p. [Editor: missing word].] And truly Sir, I have bin a contestor and sufferer for the Liberties of England these twelve yeers together, and I should now look upon my self as the basest fellow in the world, if now in one moment I should undo all that I have bin doing all this while, which I must of necessity do, if I should answer you to questions against my self, For in the first place, by answering this question against my self, I should betray the Liberties of England, in acknowledging you to have a Legal Jurisdiction over me, to try and adjudge me, which I have already proved to your faces you have not in the least: and if you have forgot what you said to me thereupon, yet I have not forgot what I said to you. And secondly Sir, if I should answer to questions against my self, and to betray my self, I should do that which not onely Law, but Nature abhors: And therefore I cannot but wonder that you your selves are not ashamed to demand so illegal and unworthy a thing of me as this is. [Margin note: 5. And well might I, for M. John Cook, and M. Bradshaw himself were my Counsel at the Lords Bar, against the Star-Chamber, the 13. Feb. 1645. where M. Bradsahw did most excellently open the Star-chamber injustice towards me; and at the reading of their first sentence, he observed to the Lords, that that sentence was felo da fe, guilty of its own death; the ground whereof, being because M. Lilburn refused to take an oath to answer all such questions as should be demanded of him, it being contrary to the Laws of God, Nature, and the Kingdom, for any man to be his own Accuser : Whose words may more at large read in the Printed relation thereof, drawn up by M. John Cook, and my self, p. 3.] And therefore in short, were it that I owned your power (which I do not in the least) I would be hanged, before I would do so base, and un-Englishman-like an Action, to betray my Liberty, which I must of necessity do, in answering questions to accuse my self: But Sir, This I will say to you, my late Actions have not bin done in a hole, or a corner, but on the house top, in the face of the Sun, before hundreds and some thousands of people, and therefore why ask you me any questions? Go to those that have heard me, and seen me, and it is possible you may find some hundreds of witnesses to tell you what I have said and done; for I hate holes and corners: My late Actions need no covers nor hidings, they have bin more honest than so, and I am not sorry for what I have done, for I did look well about me before I did what I did, and I am ready to lay down my life to justifie what I have done, and so much in answer to your question.

But now Sir, with your favour one word more, to mind you again of what I said before, in reference to my Martial imprisonment, and truly Sir, I must tell you, Circumstantials of my Liberty, at this time I shall not much dispute, but for the Essentials of them I shall dy: I am now in the Souldiers custody, where to continue in silence and patience, is absolutely to betray my Liberty; for they have nothing to do with me, nor the meanest Free-man of England in this case; and besides Sir, they have no rules to walk by, but their wills and their swords, which are two dangerous things; it may be I may be of an hasty cholerick temper, and not able nor willing to bear their affronts; and peradventure they may be as willing to put them upon me, as I am unwilling to bear them; and for you in this case to put fire and tinder together, to burn up one an other, will not be much commendable, nor tend much to the accomplishment of your ends, But if for all this, you shall send me back to the Military sword again, either to White-hall, or any other such like garison’d place in England, I do solemnly protest before the Eternal God of Heaven and Earth, I will fire it, and burn it down to the ground, if possibly I can, although I be burnt to ashes with the flames thereof, for Sir, I say again, the souldiers have nothing to do to be my Goalers; and besides, it is a maxime among the souldiers, That they must obey (without dispute) all the Commands of their Officers, be they right or wrong, and it is also the maxime amongst the Officers, That if they do not do it, they must hang for it: therefore if the Officers command them to cut my throat, they must either do it, or hang for it. And truly Sir, (looking wishfully upon Cromwell, that sate just against me) I must be plain with you, I have not found so much Honour, Honesty, Justice, or Conscience, in any of the principal Officers of the Army, as to trust my life under their protection, or to think it can be safe under their immediate fingers, [Margin note: 6. And truly I am more afraid honest Capt. Bray hath too much experience of this at Windsor Castle, who though he be but barely committed thither into safge custody, yet (as I from very good hands am informed) the Tryrannical Governour Whichcock, Cromwels creature, doth keep him close prisoner, denying him the benefit of the castle Ayre, keeping not onely pen and inke from him, but also his friends and necessaries with which cruelty &c. he hath already almost murdered and destroyed the honest man; in whose place were I, and so illegally and unjustly used, a flame (if possibly I could, should be the portion of my chamber, although I perished in it.] and therefore not knowing, nor very much caring what you will do with me, I earnestly intreat you, if you will again imprison me, send me to a Civil Goal that the Law knows, as Newgate, the Fleet, or the Gatehouse, and although you send me to a Dungeon, thither I will go in Peace and quietness, without any further dispute of your authority, For when I come there, I know those Goalers have their bounds and limits set them by the Law, and I know how to carry my self towards them, and what to expect from them; and if they do abuse me, I know how in law to help my self. And so Sir, I have said what at present I have to say. Whereupon M. Bradshaw commanded the Sergeant to put me out at an other dore, that so I should no more go amongst the people, and immediatly M. Walwin was put out to me, and asking him what they said to him, I found it to be the same in effect they said to me, demanding the same fore-going question of him, that they did of me: to which question, (after some kind of pause) he answered to this effect, That he could not but very much wonder to be asked such a question, however that it was very much against his Judgement and Conscience to answer to questions of that nature, which concerned himself; that if he should answer to it, he should not onely betray his own Liberty, but the Liberties of all Englishmen, which he could not do with a good Conscience, And he could not but exceedingly grieve at the dealing he had found that day; That being one who had alwaies bin so faithful to the Parliament, and so well known to most of the Gentlemen there present, that nevertheless he should be sent for with a party of Horse and Foot, to the affrighting of his Family, and ruine of his credit; And that he could not be satisfied, but that it was very hard measure, to be used thus upon suspition onely; And that if they did hold him under restraint from following his business and occasions, it might be his undoing, which he conceived they ought seriously to consider of.

Then M. Bradshaw said, he was to answer the question, and that they did not ask it as in way of Tryal, so as to proceed in Judgement thereupon, but to report it to the House. To which M. Walwin said, That he had answered it so as he could with a good Conscience, and could make no other Answer, and so with-drew.

And after he came out to me, M. Overton was next called in againe, and then M. Prince, so after we were all come out, and all foure in a roome close by them, all alone, I laid my care to their dore, and heard Lieutenant General Cromwel (I am sure of it) very loud, thumping his fist upon the Councel Table, til it rang againe, and heard him speak in these very words, or to this effect; I tel you Sir, you have no other way to deale with these men, but to break them in pieces; and thumping upon the Councel Table againe, he said Sir, let me tel you that which is true, if you do not breake them, they will break you; yea, and bring all the guilt of the blood and treasure shed and spent in this Kingdom upon your heads and shoulders; and frustrate and make voide all that worke, that with so many yeares industry, toile and paines you have done, and so render you to all rationall men in the world, as the most contemptiblest generation, of silly, low spirited men in the earth, to be broken and routed by such a despicabic contemptible generation of men as they are; and therfore Sir I tel you againe, you are necessitated to break them. But being a little disturbed by the supposition of one of their Messengers coming into the roome, I could not so well heare the answer to him, which I think was Col. Ludlows voyce, who pressed to baile us, for I could very well heare him say, what would you have more than security for them? Upon which discourse of Cromwels, the blood run up and down my veines, and I heartily wisht my self in againe amongst them (being scarse able to contain my self) that so I might have gone five, or six stories higher than I did before, yea, as high as I intended when I came to their dore, and to have particularly paid Cromwel and Hasleridge to the purpose, for their late venome not only against me in the House, but my whole family, Hasleridge saying (as I am informed) in the open House, there was never an one of the Lilburns family fit or worthy to be a Constable in England, though I am confident there is not the worst of us alive that have served the Parliament, but he is a hundred times more just honest and unspoted than he himself, as in due time I shal make it appeare by Gods assistance (I hope) to his shame: But the faire carriage of the Gentlemen of the supposed Councel to me at the first, tooke off the height of the edge of my spirit, and intended resolution, which it may be they shal have the next time to this effect. You your selves have already voted the People under God, the Fountain and Original of all just power, And if so, then, none can make them Laws, but those that are chosen, impowred, and betrusted by them for that end, and if that be true, as undoubtedly it is, I desire to know how the present Gentlemen at Westminster can make it appeare they are the peoples Representatives, being rather chosen by the wil of him, whose head as a Tyrant and Traytor, they have by their wills chopt off (I mean the King) then by the people: whose Will made the Borough Townes to chuse Parliament men, and there by rob’d above nineteen people of this Nation, of their undubitable and inherent right, to give to a single man in twenty for number (in reference to the whole Nation) a Monopoly to chuse Parliament men; disfranchising thereby the other nineteen, and if so in any measure than this, upon their own declared principles they are no Representative of the people, no nor was not at the first, Again, the King summoned them by his Writ, the issue of his will and pleasure, and by vertue of that they sit to this houre, Again, the King by his Will and pleasure combines with them by an Act to make them a perpetual Parliament (one of the worst and tyranicallest actions that ever he did in his life) to sit as long as they pleased, which he nor they had no power to do in the least, the very constitution of Parliaments in England, being to be once every yeare, or oftner if need require, Quere, Whether this act of perpetuating this Parliament by the Parliament men themselves beyond their Commission, was not an act in them of the highest Treason in the world against the People and their liberties, by setting up themselves an arbitrary power over them for ever? Yea, and thereby razing the foundation and constitution of Parliament it self: And if so, then this is nul, if at the first it had bin any thing.

Again, if it should be granted this Parliament at the beginning had a legal constitution from the people (the original and fountaine of all just power) yet the Faction of a trayterous party of Officers of the Army, hath twice rebelled against the Parliament, and broke them to pieces, and by force of Armes culled out whom they please, and imprisoned divers of them and laid nothing to their charge, and have left only in a manner a few men, besides eleven of themselves, viz. the General, Cromwel, Ireton, Harrison, Fleetwood, Rich, Ingolsby, Hasleridge, Constable, Fennick, Walton and Allen, Treasurer, of their own Faction behind them that will like Spaniel-doggs serve their lusts and wills, yea some of the chiefest of them, viz. Ireton, Harrison, &c. yea, M. Holland himself, stiling them a mocke Parliament a mocke power at Windsor, yea, it is yet their expressions at London; And if this be true that they are a mocke power and a mocke Parliament, then,

Quere, Whether in Law or Justice, especially considering they have fallen from al their many glorious promises, & have not done any one action that tends to the universal good of the People? Can those Gentlemen siting at Westminster in the House, called the House of Commons, be any other than a Factious company of men trayterously combined together with Crom. Ireton, and Harrison, to subdue the Laws, Liberties, and Freedomes of England; (for no one of them protest against the rest) and to set up an absolute and perfect Tyranny of the Sword, Will and pleasure, and absolutely intend the destroying the Trade of the Nation, and the absolute impoverishing the people thereof, to fit them to be their Vassals and Slaves; And if so, then,

Quere, Whether the Free People of England, as well Soldiers as others, ought not to contemne all these mens commands, as invalid and illegal in themselves, and as one man to rise up against them as so many professed traytors, theives, robbers and high way men, and apprehend and bring them to justice in a new Representative, chosen by vertue of a just Agreement among the People, there being no other way in the world to preserve the Nation but that alone; the three forementioned men, viz. Cromwel, Ireton, and Harrison, (the Generall being but their Stalking horse, and a Cifer) and there trayterous faction, [Margin note: 7. For the greatest Traytors they are that ever were in this nation, as upon the losse of my head I John Lilburn will by law undertake to prove and make good, before the next free parliament, to whom I hereby appeale.] having by their wills and Swords, got all the Swords of England under their command, and the disposing of all the great places in England by Sea and Land, and also the pretended Law making power, and the pretended law executing power, by making among themselves (contrary to the Laws and Liberties of England) all Judges, Justices of peace, Sherifes, Balifes, Committee men &c. to execute their wills and Tyranny, walking by no limits or bounds but their own wills and pleasures, And traytorously assume unto themselves a power to levy upon the people what money they please, and dispose of it as they please, yea even to buy knifes to cut the peoples throats that pay the mony to them, and to give no account for it til Doomes Day in the afternoone, they having already in their wills and power to dispose of the Kings, Queens, Princes, Dukes, and the rest of the childrens Revenue, Deans and Chapters lands, Bishops lands, sequestered Delinquents lands, sequestred Papists lands, Compositions of all sorts, amounting to millions of money, besides Excise, and Customes, yet this is not enough, although if rightly husbanded it would constantly pay above one hundred thousand men, and furnish an answerable Navy there unto: But the people must now after their trades are lost, and their estates spent to procure their liberties and freedoms, be cessed about 100000. pound a moneth, that so they may be able like so many cheaters and State theeves, to give 6. 8. 10. 12. 14. 16, thousand pounds a peice over again to one another, as they have done already to divers of themselves to buy the Common wealths lands one of another, (contrary to the duty of Trustees, who by law nor equity can neither give nor sel to one another) at two or three years purchase the true and valuable rate considered, as they have already done, and to give 4 or 5000 l per annum over again to King Cromwel, as they have done already out of the Earle of Worcesters estate, &c. Besides about four or five pounds a day he hath by his places of Lieut. General, and Collonel of Horse in the Army, although he were at the beginning of this Parliament but a poore man, yea, little better than a begger (to what he is now) as well as other of his neighbours.

But to return, those gentlemen that would have had us bailed lost the day, by one vote as we understood, and then about 12. at night they broke up, & we went into their pretended Secretary, & found our commitments made in these words, our names changed, viz.

These are to will and require you, to receive herewith into your custody, the person of Lieut. Col. John Lilburn, and him safely to keep in your Prison of the Tower of London, until you receive farther order, he being committed to you upon suspition of high Treason, of which you are not to faile, and for which this shal be your sufficient Warrant, Given at the Councel of State at Darbyhouse this 28. day of March, 1649.

Order of the Councel of State,

appointed by authority of

Parliament. JO. BRADSHAW.

President.

of London.

Note that we were committed upon Wednesday their fast day, being the best fruits that ever any of their fasts brought out amongst them, viz. To smite with the fist of wickedness. For the illegality of this Warrant, I shall not say much, because it is like all the rest of the Warrants of the present House of Commons, and their unjust Committees, whose Warrants are so sufficiently anatomised by my quondam Comrade, M. John Wildman, in his books, called Truths Tryumph, and The Laws subversion, being Sir John Maynards case truly stated, and by my self, in my late Plea before the Judges of the Kings Bench, now in print, and intituled The Laws Funeral, that it is needless to say any more of that particular, and therefore to them I refer the Reader. But to go on, when we had read our Warrants we told M. Frost we would not dispute the legality of them, because we were under the force of Guards of Armed musquettiers: So some time was spent to find a man that would go with us to prison, Capt. Jenkins (as I remember his name) being Capt. of the Guard, and my old and familiar acquaintance, was prevailed with by us, to take the charge upon him, who used us very Civilly, and gave us leave that night (it being so late) to go home to our wives, and took our words with some other of our friends then present, to meet him in the morning at the Angel Tavern neer the Tower, which we did accordingly, and so marched with him into the Tower, where coming up to the Lieut. house, and after salutes each of other with very much civility, the Lieut. read his Warrants: and M. Walwin as our appointed mouth, acquainted him that we were Englishmen, who had hazarded all we had for our Liberties & Freedoms for many yeers together, and were resolved (though Prisoners) not to part with an inch of our Freedoms, that with strugling for we could keep, and therefore we should neither pay fees nor chamber rent, but what the Law did exactly require us, neither should we eate or drink of our own cost and charges so long as we could fast, telling him it was our unquestionable right by Law, and the custom of this place, to be provided for out of the publike Treasure, although we had never so much mony in our pockets of our own, which he granted to be true, and after some more debate I told him, we were not so irrational as to expect that he out of his own money should provide for us: but the principal end of our discourse with him was, to put words in his mouth from our selves, (he being now our Guardian) to move the Parliament or Councel of State about us, which he hath acquainted us he did to the Councel of State, who he saith granted the King in former times used to provide for the Prisoners, but I say, they will not be so just as he was in that particular, although they have taken off his head for tyranny, yet they must and will be greater Tyrants than he, yea, and they have resolved upon the Question, that he shall be a Traytor that shall but tell them of their tyranny, although it be never so visible.

So now I have brought the Reader to my old and contented Lodging in the Tower, where within two, or three dayes of our arrival there, came one M. Richardson a Preacher amongst those unnatural, un-English-like men, that would now help to destroy the innocent, and the first promoters in England (as Cromwels beagles to do his pleasure) of the first Petition for a Personal Treaty almost 2. yeers ago, and commonly stile themselves the Preachers to the 7. Churches of Anabaptists, which Richardson pretending a great deal of affection to the Common wealth to Cromwel, & to us, prest very hard for union and peace, (and yet by his petition since this, endeavors to hang us) teling us, men cryed mightily out upon us abroad for grand disturbers, that sought Crom. bloud for al his good service to the Nation, and that would center no where, but meerly laboured to pul down those in power, to set up our selves: And after a little discourse with him, being all 4. present, and retorting all he said back upon those he seemed to plead for, before several witnesses, we appeale to his own conscience, whether those could intend any hurt or tyrannie to the people, that desires, and earnestly endeavours for many yeers together, that all Magistrates hands might be bound and limited by a just law and rule, with a penalty annexed unto it, that in case they outstrip their rule, they might forfet life & estate, and that al Magistrates might be chosen by the free people of this Nation by common consent, according to their undubitable right, & often removed, that so they might not be like standing waters, subject to corruption; and that the people might have a plain, easie, short, and known Rule amongst themselves to walk by; but such men were all we; and therefore justly could not be stiled disturbers of any, but onely such as sought to rule over the people by their absolute Wills and pleasures, and would have no bounds or limits but their lusts, and so sought to set up a perfect tyranny, which we absolutely did, and stil do charge upon the great men in the Army, and are ready before indifferent Judges to make it good. And as for seeking our selves, we need no other witnesses but some of our present adversaries in the House, whose great proffered places, and courtship by themselves and their Agents some of us have from time to time slighted, scorned, and contemned, till they would conclude to come to a declared and resolved center, by a just Agreement of the People; there being no other way now in the World to make this Nation free, happy, or safe, but that alone. And as for Cromwels bloud, although he had dealt basely enough with some of us in times by-past, by thirsting after ours, without cause, of whom (if revenge had bin our desire) we could have had it the last yeer to the purpose, especially when his quondam Darling, Maj. Huntington, (Maj. to his own Regiment) impeached him of Treason to both Houses: yet so deer was the good of our native Country to us, to whom we judged him then a serviceable Instrument to ballance the Scots, that we laid all revenge aside, hoping his often dissembled Repentances was real indeed; and M. Holland himself (now his favorite) if his 1000. or 1500. l. per annum of the Kings Lands, that now he enjoys, did not make him forget himself, can sufficiently testifie and witness our unwearied and hazardous Activity for Cromwels particular preservation the last yeer, when his great friends in the House durst not publikely speak for him.

And whereas it is said we will Center no where, we have too just cause to charge that upon them; the whole stream of all our Actions (as we told Richardson) being a continued Declaration of our earnest Desires to come to a determinate and fixed center: one of us making sufficient propositions to that purpose to the Councel of State at our last being there and all our many and late proffers as to that particular, they have hitherto rejected, as no waies consistent with their tyranical and selfish ends and designs: and have given us no other answer in effect, but the sending our bodies prisoners to the Tower: and therefore we judged it infinitely below us (as we told him) and that glorious cause (the Peoples Liberties and Freedoms, that we are now in bonds for) & for which we suffer, to send any message but a defiance by him or any other to them. Yet to let him know (as one we judged honest, and our friend) we were men of reason, moderation, and justice, and sought nothing particularly for our selves, more than our common share in the common freedom, tranquility, and peace of the land of our Nativity: We would let him know, we had a two fold Center, and if he pleased of and from himself to let our Adversaries know, we were willing our adversaries should have their choise to which of the two they would hold us to.

And therefore said we in the first place, The Officers of the Army have already compiled, and published to the view of the Nation, an Agreement of the people, which they have presented to the present Parliament, against which we make some exceptions, which exceptions are contained in our Addresses: Now let them but mend their Agreement according to our exceptions, and so far as all our interest extends in the whole Nation, we wil acquiesce and rest there, and be at peace with them, & live and dy with them in the pursuance of those ends, and be content for Cromwel and Iretons security, &c. for the bloud of war shed in time of peace at Ware, or any thing else, and to free our selves that we thirst after none of their bloud, but onely our just Liberties (without which we can never sit down in peace) That there shall be a clause, to bury all things in oblivion, as to life and liberty, excepting onely estate; that so the Common-wealth may have an account of their monies in Treasurers hands, &c.

Or secondly, if they judge our exceptions against their Agreement (or any one of them) irrational, let them chuse any 4. men in England, and let Cromwel and Ireton be 2. of them, and take the other 2. where they please, in the whole nation, and we 4. now in prison, will argue the case in reason with them, and if we can agree, there is an end, as to us, and all our interest, but in case we cannot, let them (said we all) chuse any 2. members of the House of Commons, and we will chuse 2. more, viz. Col. Alex. Rigby, and Col. Henry Martin, to be final umpires betwixt us, and what they, or the major part of them determine, as to us (in relation to an Agreement) and all our interest in the whole land, we will acquiesce in, be content with, and stand to without wavering: and this we conceive to be as rational, just, and fair, as can be offered by any men upon earth: and I for my part, say and protest before the Almighty, I will yet stand to this, and if this will content them, I have done, if not, fall back, fal edge, let them do their worst, I for my part bid defiance to them, assuredly knowing, they can do no more to me, than the divel did to Job: for resolved by Gods assistance I am, to spend my heart bloud against them, if they will not condescend to a just Agreement that may be good for the whole Nation, that so we may have a new and as equal a Representative as may be, chosen by those that have not fought against their freedoms, although I am as desirous the Cavaliers should enjoy the benefit of the Law, for the protection of their persons and estates, as well as my self. I know they have an Army at command, but if every hair on the head of that Officer or Souldier they have at their command, were a legion of men, I would fear them no more than so many straws, for the Lord Jehovah is my rock and defence, under the assured shelter of whose wings, I am safe and secure, and therefore will sing and be merry, and do hereby sound an eternal trumpet of defiance to all the men and divels in earth and hell, but only those men that have the image of God in them, and demonstrate it among men, by their just, honest, merciful, and righteous actions. And as for all those vile Actions their saint-like Agents have fixed upon me of late, I know before God none is righteous no not one, but only he that is clothed with the glorious righteousness of Jesus Christ, which I assuredly know my soul hath bin, and now is clothed with, in the strength of which I have walked for above 12 yeers together, and through the strength of which, I have bin able at any time in al that time, to lay down my life in a quarter of an hours warning. But as to man, I bid defiance to all my Adversaries upon earth, to search my waies and goings with a candle, and to lay any one base Action to my charge in any kind whatsoever, since the first day that I visible made profession of the fear of God, which is now above twelve yeares, yea, I bid defiance to him or them, to proclaim it upon the house tops, provided he will set his hand to it, and proclaim a publique place, where before indifferent men, in the face of the Sun, his accusation may be scand; yea, I here declare, that if any man or woman in England, either in reference to my publique actions, to the States money, or in reference to my private dealings in the world shal come in and prove against me, that ever I defrauded him, or her of twelve pence, and for every twelve pence that I have so done, I will make him or her twenty shillings worth of amends, so far as all the estate I have in the world will extend.

Curteous Reader, and deer Countryman, excuse I beseech thee my boasting and glorying, for I am necessitated to it, my adversaries base and lying calumniations puting me upon it, and Paul and Samuel did it before me: and so I am thine, if thou art for the just Freedoms and Liberties of the land of thy Nativity.

Postscript.

Curteous Reader, I have much wondered with my self, what should make most of the Preachers in the Anabaptist Congregations so mad at us foure, as this day to deliver so base a Petition, in the intention of it against us all four; (who have bin as hazardous Sticklers for their particular liberties, as any be in England) and never put a provocation upon them that I know of, especially, considering the most, if not all their Congregations (as from divers of their own members I am informed) protested against their intentions openly in their Congregations, upon the Lords day last, and I am further certainly informed that the aforsaid Petition the Preachers delivered, is not that which was read by themselves amongst the people, but another of their own framing since, which I cannot hear was ever read in any one of their Congregations: So that for the Preachers viz. M. Kiffin, M. Spilsbury, M. Patience, M. Draps, M. Richardson, M. Constant, M. Wayd, the Schoolemaster, &c. to deliver it to the Parliament in the name of their Congregations, they have delivered it a lye and a falshood, and are, a pack of fauning daubing knaves for so doing, but as I understand from one of M. Kiffins members, Kiffin himself did ingenuously confesse upon Lords day last, in his open Congregation, that he was put upon the doing of what he did by some Parliament men, who he perceived were willing and desirous to be rid of us four, so they might come off handsomely without too much losse of credit to themselves: and therefore intended to take a rise from their Petition to free us, and for that end it was, that in their Petition read in the Congregations, after they had sufficiently bespattered us, yet in the conclusion they beg mercy for us, because we had bin formerly active for the Publique. Secondly, I have bin lately told, some of the Congregationall Preachers are very mad, at a late published and licensed booke sold in Popes head Alley and Comhill, intituled, The vanity of the present Churches, supposing it to be the Pen of some of our friends, and therefore out of revenge might Petition against us; I confesse I have within a few houres seen and read the booke, and not before, and must ingenuously confesse, it is one of the shrewdest bookes that ever I read in my life, and do believe it may be possible they may be netled to the purpose at it, but I wish every honest unbyased man in England would seriously read it over.

The Proceedings of the Councel of State against Richard Overton, now prisoner in the Tower of London.

Upon the twenty eighth of March 1649) a partie of Horse and Foot commanded by Lieut. Colonel Axtel (a man highly pretending to religion,) came betwixt five and six of the morning to the house where I then lodged, in that hostile manner to apprehend me, as by the sequel appeared.

But now, to give an account of the particular circumstances attending that action, may seem frivolous, as to the Publick, but in regard the Lieutenant Colonel was pleased so far to out-strip the capacity of a Saint, as to betake himself to the venomed Arrows of lying calumnies and reproaches, to wound (through my sides) the too much forsaken cause of the poor oppressed people of this long wasted Common-wealth: like as it hath been the practice of all perfidious Tyrants in all ages. I shall therefore trouble the Reader with the rehearsall of all the occurrant circumstances which attended his apprehension of me, that the world may cleerly judge betwixt us. And what I here deliver from my pen as touching this matter, I do deliver it to be set upon the Record of my account, as I will answer it at the dreadfull day of judgment, when the secrets of all hearts shall be opened, and every one receive according to his deeds done in the flesh: and God so deal with me at that day, as in this thing I speak the truth: And if the rankorous spirits of men will not be satisfied therewith, I have no more to say but this, to commit my self to God in the joyful rest of a good conscience, and not value what insatiable envie can suggest against me. Thus then to the businesse it self.

In the House where I then lodged that night there lived three families, one of the Gentlemen being my very good friend, with whom all that night hee and I onely lay in bed together, and his Wife and childe lay in another bed by themselves: and when they knocked at the door, the Gentleman was up and ready, and his Wife also, for she rose before him, and was suckling her childe: and I was also up, but was not completely drest, And of this the Gentleman himself (her Husband) hath taken his oath before one of the Masters of the Chancery. And we three were together in a Chamber discoursing, he and I intending about our businesse immediately to go abroad, and hearing them knock, I said, Yonder they are come for me. Whereupon, some books that lay upon the table in the room, were thrown into the beds betwixt the sheets (and the books were all the persons he found there in the beds, except he took us for printed papers, and then there were many,) and the Gentleman went down to go to the door; and as soon as the books were cast a toside, I went to put on my boots, and before the Gentleman could get down the stairs, a girl of the house had opened the door, and let them in, and so meeting the Gentleman upon the stairs, Axtel commanded some of the souldiers to seize upon him, and take him into custodie, and not suffer him to come up: And I hearing a voice from below, that one would speak with me, I went to the chamber door (it being open) and immediatly appeared a Musketier (Corporal Neaves, as I take it) and he asked me if my name were not Mr. Overton: I answered, it was Overton, and so I sat me down upon the bed side to pull on my other boot, as if I had but new risen, the better to shelter the books, and that Corporal was the first man that entered into the chamber, and after him one or two more, and then followed the Lieutenant Colonel, and the Corporal told me, I was the man they were come for, and bade me make me ready: and the Lieutenant Colonel when he came in, asked me how I did, and told me, they would use me civilly, and bid me put on my boots, and I should have time enough to make me ready: And immediately upon this the Lieutenant Colonel began to abuse me with scandalous language, and asked me, if the Gentlewoman who then sate suckling her childe, were not one of my wives, and averred that she and I lay together that night. Then the Gentleman hearing his Wife call’d Whore, and abused so shamefully, got from the souldiers, and ran up stairs; and coming into the room where we were, he taxed the Lieutenant Colonel for abusing of his Wife and me, and told him, that he and I lay together that night: But the Lieutenant Colonel, out of that little discretion he had about him, took the Gentleman by the hand, saying, How dost thou, brother Cuckcold? using other shamefull ignorant and abusive language, not worthy repeating. Well, upon this his attempt thus to make me his prisoner, I demanded his Warrant; and he shewed me a Warrant from the Councell of State, with Mr. Bradshaw’s hand to it, and with the Broad Seal of England to it, (as he call’d it) to apprehend Lieutenant Colonel Lilburn, Mr. Walwine, Mr. Prince, and my self, where-ever they could finde us. And as soon as I was drest, he commanded the Musketiers to take me away, and as soon as I was down stairs, he remanded me back again into the chamber where he took me, and then told me, he must search the house, and commanded the trunks to be opened, or they should be broken open: and commanded one of the souldiers to search my pockets. I demanded his Warrant for that: He told me, he had a Warrant, I had seen it. I answered, That was for the apprehension of my person, and bid him shew his Warrant for searching my pockets, and the house: and according to my best remembrance, he replyed, He should have a Warrant. So little respect had he to Law, Justice, and Reason; and vi & armis, right or wrong, they fell to work, (inconsiderately devolving all law, right, and freedom betwixt man and man into their Sword; for the consequence of it extends from one to all, and his party of armed Horse and Foot (joyned to his over-hasty exorbitant will) was his irresistible Warrant: And so they searched my pockets, and took all they found in them, my mony excepted, and searched the trunks, chests, beds, &c. And the Lieutenant Colonel went into the next chamber, where lived an honest Souldier (one of the Lieutenant Generals Regiment) and his wife, and took away his sword, and vilified the Gentleman and his wife, as if she had been his whore, and took him prisoner for lying with a woman, as he said. He also went up to the Gentleman who lets out the rooms, and cast the like imputations upon his wife, as also upon a Maid that lives in the house, and gave it out in the Court and Street, amongst the souldiers and neighbours that it was a Bawdy-house, and that all the women that lived in it were whores, and that he had taken me in bed with another mans Wife. Well, he having ransack’d the house, found many books in the beds, and taken away all such writings, papers, and books, of what sort or kind soever, that he could finde, and given them to the souldiers, (amongst which he took away certain papers which were my former Meditations upon the works of the Creation, intituled, Gods Word confirmed by his Works; wherein I endeavoured the probation of a God, a Creation, a State of Innocencie, a Fall, a Resurrection, a Restorer, a Day of Judgment, &c. barely from the consideration of things visible and created: and these papers I reserved to perfect and publish as soon as I could have any rest from the turmoils of this troubled Common-wealth: and for the loss of those papers I am only troubled: all that I desire of my enemies hands, is but the restitution of those papers, that what-ever becomes of me, they may not be buried in oblivion, for they may prove usefull to many.) Well, when the Lieutenant Colonel had thus far mistaken himself, his Religion and Reason thus unworthily to abuse me and the houshold in that scandalous nature, unbeseeming the part of a Gentleman, a Souldier, or a Christian (all which titles he claimeth) and had transgressed the limits of his Authority, by searching, ransacking, plundering, and taking away what he pleased, he march’d me in the head of his party to Pauls Church-yard, and by the way commanded the souldiers to lead me by the arm, and from thence, with a guard of three Companies of Foot, and a party of Horse, they forced me to Whitehall; and the souldiers carried the books some upon their Muskets, some under their arms: but by the way (upon our march) the Corporall that first entred the room (whose word in that respect is more valuable then Axtels) confess’d unto me (in the audience of the Souldier they took also with them from the place of my lodging) that the Lieutenant Colonel had dealt uncivilly and unworthily with me, and that there was no such matter of taking me in bed with an other woman, &c. And this the said souldier will depose upon his oath.

When I came to White-hall, I was delivered into the hands of Adjutant General Stubber, where I found my worthy friends Lieutenant Collonel John Lilburn, Mr. Wallwin, and Mr. Prince in the same captivity under the Martiall usurpation: and after I had been there a while, upon the motion of Leiutenant Collonell Lilburne, that Leiutenant Collonell Axstell, and I might be brought face to face about the matter of scandall that was raised, he coming there unto us, and questioned about the report he had given out, there averd, that he took me a bed with an other mans wife; and being asked if he saw us actually in bed together, he answered, we were both in the Chamber together, and the woman had scarce got on her coates, (which was a notorious untruth) and she sate suckling of her child, and from these circumstances he did believe we did lie together, and that he spake according to his conscience what he beleeved: These were his words, or to the like effect, to which I replied, as aforementioned. But how short this was of a man pretending so much conscience and sanctity as he doth I leave to all unprejudiced people to judge: it is no point of Christian faith (to which is so great a pretender) to foment a lye for a wicked end, and then to plead it his beleif and conscience, for the easier credence of his malitious aspertion: but though the words belief and Conscience be too specious Evangelicall tearms, no truely consciencious person will say they are to be used, or rather abused to such evill ends. Well in that company I having taxed him for searching my pockets, and without warrant, he answered; that because I was so base a fellow, he did what he could to destroy me. And then the better to make up the measure of the reproach he had raised, he told us, it was now an opinion amongst us to have community of women; I desired him to name one of that opinion, he answered me, It may be I was of that opinion, and I told him, it may be he was of that opinion, and that my may be was as good as his May be: whereupon he replyed, that I was a sawsy fellow. Surely the Lieutenant Collonel at that instant had forgot the Bugget from whence he dropt, I presume when he was a pedler in Harfordshire he had not so lofty an esteem of himself, but now the case is altered, the Gentleman is become one of the Grandees of the Royall palace: one of the (mock-) Saints in season, now judgeing the Earth, inspired with providence and opportunities at pleasure of their own invention as quick and as nimble as an Hocas Spocas, or a Fiend in a Juglers Box) they are not flesh and bloud, as are the wicked, they are all spirituall, all heavenly, the pure Camelions of the time, they are this or that or what you please, in a trice, in a twinkling of an eye; there is no form, no shape that you can fancy among men, into which their Spirituallities are not changeable at pleasure; but for the most part, these holy men present themselves in the perfect figure of Angels of light, of so artificiall resemblance, enough to deceive the very Elect if possible, that when they are entered their Sanctum Sanctorum, their holy convocation at Whitehall, they then seem no other than a quire of Arch-Angels, of Cherubins and Seraphims, chanting their fals-holy Halelujaes of victory over the people, having put all principalities and powers under their feet, and the Kingdom and dominion and the greatness of the Kingdom is theirs, and all Dominions, even all the people shall serve and obey them, [excuse me, it is but their own Counterfeit Dialect, under which their pernitious hipocrisy is vailed that I retort into their bosoms, that you may know them within and without, not that I have any intention of reflection upon holy writ] and now these men of Jerusalem (as I may terme them) those painted Sepulchers of Sion after their long conjuring together of providences, opportunities and seasons one after another, drest out to the people in the sacred shape of Gods Time, (as after the language of their new fangled Saint-ships I may speak it) they have brought their seasons to perfection, even to the Season of Seasons, now to rest themselves in the large and full enjoyment of the creature for a time, two times and half a time, resolving now to ware out the true asserters of the peoples freedom, and to change the time and laws to their exorbitant ambition and will, while all their promises, declarations and engagements to the people must be null’d and made Cyphers, and cast aside as wast paper, as unworthy the fulfilment, or once the remembrance of those Gentlemen, those magnificent stems of our new upstart Nobillity, for now it is not with them as in the dayes of their engagement at Newmarket and Triploe heath, but as it was in the days of old with corrupt persons, so is it in ours, Tempora mutantur—.

But to proceed to the story: the Lieutenant Collonel did not only shew his weakness, (or rather his iniquity) in his dealing with me, but he convents the aforesaid Souldier of Leiutenant Generalls Regiment before divers of the Officers at White-hall, and there he renders the reason wherefore he made him a prisoner, because said he, he takes Overtons part, for he came and asked him how he did, and bid him be of good comfort, and he lay last night with a woman: To which he answered It is true, but the woman was my wife. Then they proceeded to ask, when they were married, and how they should know shee was his wife, and he told them where and when, but that was not enough, they told him, he must get a Certificate from his Captain that he was married to her and then he should have his liberty.

Friends and Country-men, where are you now? what shall you do that have no Captains to give you Certificates? sure you must have the banes of Matrimony re-asked at the Conventicle of Gallants at White-hall, or at least you must thence have a Congregationall Licence, (without offence be it spoken to true Churches) to lye with your wives, else how shall your wives be chast or the children Legitimate? they have now taken Cognizance over your wives and beds, whether will they next? Judgement is now come into the hand of the armed-fury Saints. My Masters have a care what you do, or how you look upon your wives, for the new Saints Millitant are paramount all Laws, King, Parliament, husbands, wives, beds, &c. But to let that passe.

Towards the evening we were sent for, to go before the Counsell of State at Darby-house, and after Lieutenant Collonel John Lilburne, and Mr. Wallwine had been before them, then I was called in, and Mr. Bradshaw spake to me, to this effect.

Master Overton, the Parliament hath seen a Book, Intituled, The Second Part of Englands New-Chains Discovered, and hath past several Votes thereupon, and hath given Order to this Councel to make inquiry after the Authors and Publishers thereof, and proceed upon them as they see Cause, and to make a return thereof unto the House: And thereupon he Commanded Mr. Frost their Secretary to read over the said Votes unto me, which were to this purpose, as hath since been publickly proclaimed:

Die Martis, 27 Martii, 1649.

The House being informed of a Scandalous and Seditius Book Printed, entituled, The Second Part of Englands New-Chains Discovered.

The said Book was this day read.

Resolved upon the Question by the Commons assembled in Parliament, That this printed Paper, entituled, The Second Part of Englands New-Chains Discovered &c. doth contain most false, scandalous, and reproachful matter, and is highly Seditious and Destructive to the present Government, as it is now Declared and setled by Parliament, tends to Division and Mutiny in the Army, and the raising of a New War in the Common-wealth, and to hinder the present Relief of Ireland, and to the continuing of Free-Quarter: And this House doth further Declare, That the Authors, Contrivers, and Framers of the said Papers, are guilty of High Treason, and shall be proceeded against as Traytors; And that all Persons whatsoever, that shall joyn with, or adhere unto, and hereafter voluntarily Ayd or Assist the Authors, Framers, and Contrivers of the aforesaid Paper, in the prosecution thereof, shall be esteemed as Traytors to the Common-wealth, and be proceeded against accordingly.

Then Mr. Bradshaw spake to me much after this effect;

Master Overton, this Councel having received Information, That you had a hand in the Contriving and Publishing of this Book, sent for you by their Warrant to come before them, Besides, they are informed of other Circumstances at your Apprehension against you, That there were divers of the Books found about you. Now Mr. Overton, if you will make any Answer thereunto, you have your Liberty.

To which I answered in these words, or to the like effect:

Sir, what Title to give you, or distinguish you by, I know not, Indeed, I confesse I have heard by common report, that you go under the name of a Councel of State, but for my part, what you are I cannot well tell; but this I know, that had you (as you pretend) a just authority from the Parliament, yet were not your Authority valuable or binding, till solemnly proclaimed to the people: so that for my part, in regard you were pleased thus violently to bring me before you, I shall humbly crave at your hands, the production of your Authority, that I may know what it is, for my better information how to demean my self.

Mr. Overton, We are satisfied in our Authority.