When the Revolution comes, on what side of the Chamber/House should the Libertarians sit?

“Young Americans for Liberty” National Convention

July 26–29, 2017

Washington, D.C.

Introduction

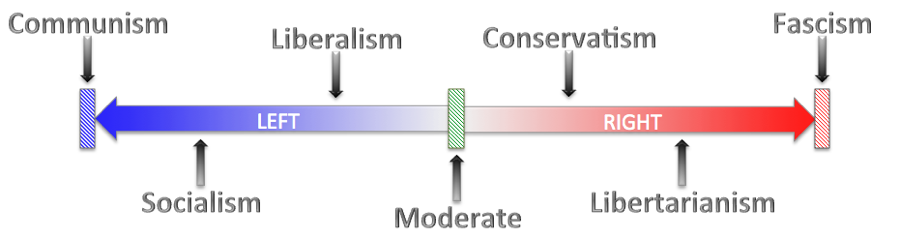

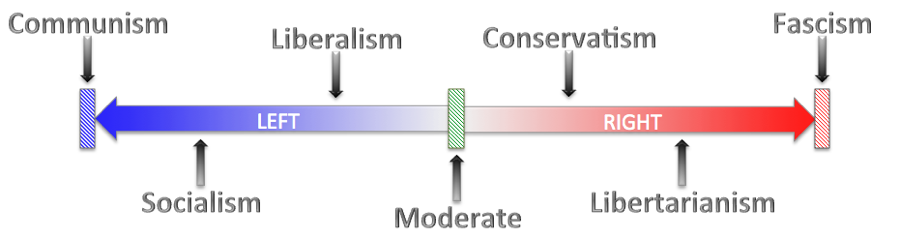

What is wrong with this picture?

Problems:

- Libertarianism associated with “Fascism”

- extreme forms of state power at both ends of spectrum; implies freedom is somewhere in “centre”

- colours wrong (red traditionally has been associated with socialism)

A few questions to begin with:

- how many of you consider yourselves to be “right wing”? (and why?)

- how many of you consider yourselves to be “left wing”? (and why?)

- what ideas define somebody from “the left”?

- what ideas define somebody from “the right”?

Recommended Reading:

Murray N. Rothbard, "Left and Right: The Prospects for Liberty," Left and Right, Spring 1965, republished in Egalitarianism as a Revolt against Nature and Other Essays (Washington, D.C.: Libertarian Review Press, 1974), pp. 14-33. [HTML]

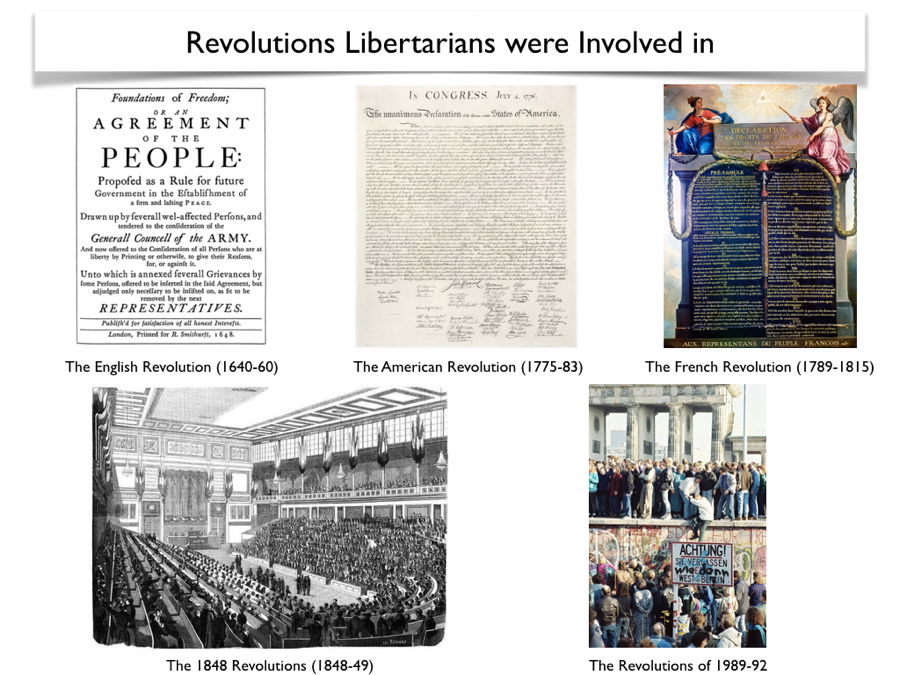

Revolutions Classical Liberals/Libertarians were involved in

- The English Revolution (1640–60)

- The American Revolution (1775–83)

- The French Revolution (1789–1815)

- The 1848 Revolutions (1848–49)

- The Revolutions of 1989–92

The Origin of the “Left” and the “Right”

I have often asked myself this question: When the Revolution comes, on what side of the Chamber/House should the Libertarians sit? On the Left or the Right, or somewhere in between, or should they refuse to take a seat entirely? (for those of you who are anarchists or “voluntaryists”) Of course, part of the answer depends on who is already sitting in the Chamber and who controls the government and for whose benefit.

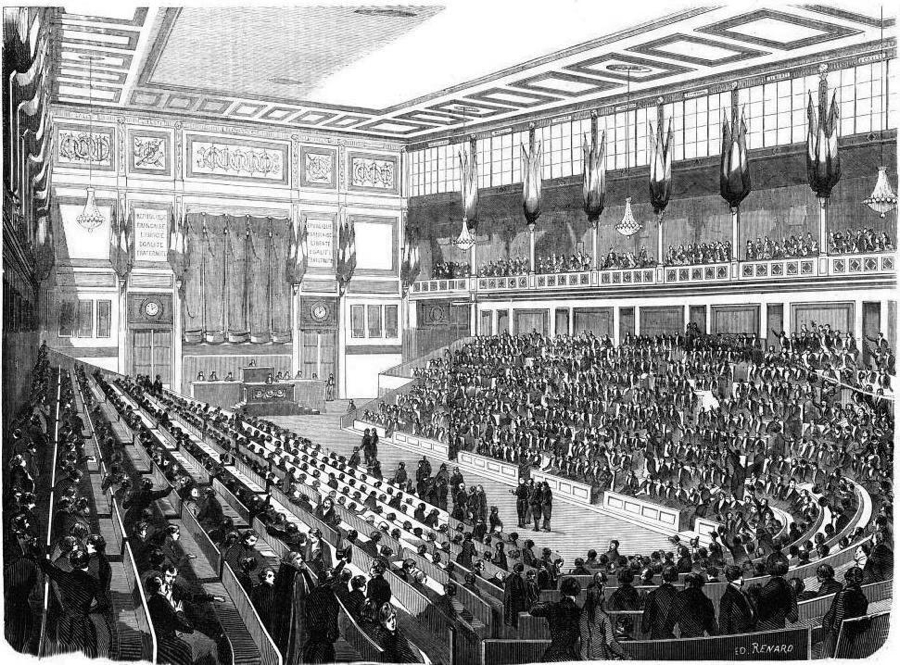

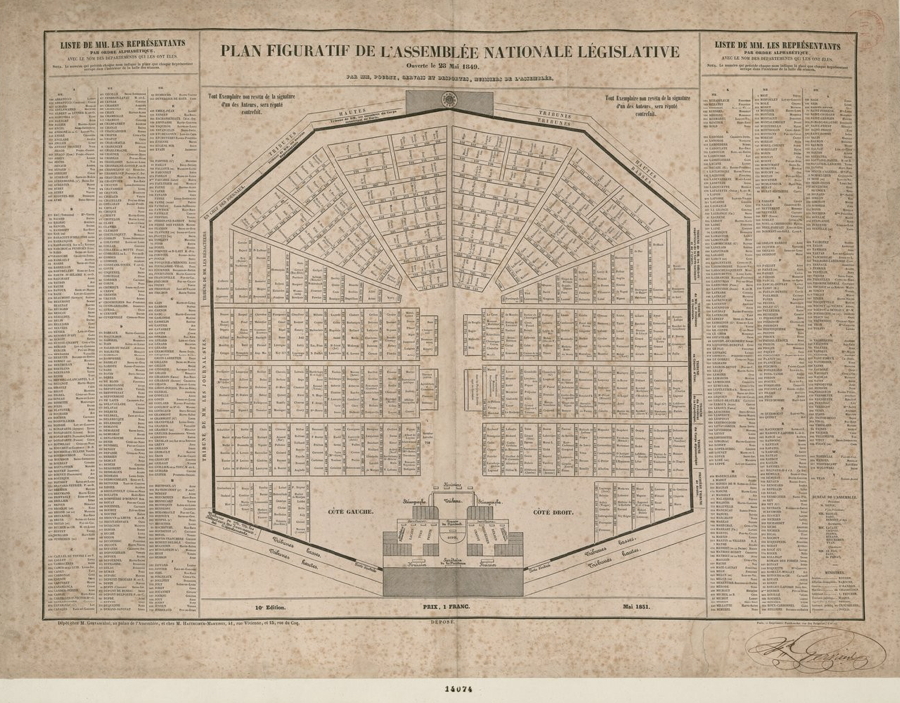

The terminology we use today to distinguish “left” and “right” along a political spectrum has its origins in the French Revolution (as many things do). Those who sat on the Left side of the Speaker in the Chamber opposed the status quo of “throne and altar”, the monarchy (plus the aristocracy and the military) and the established Catholic Church, who sat on the “Right” of the Speaker. Those on the Left supported a range of alternative ideas ranging from crackpot socialism and Rousseau-ianism, to English-style constitutional monarchism, to moderate American style republicanism, and advocates of laissez-faire and the free market. There was a complication to this practice which introduced a vertical component to the seating arrangement. The most radical of the socialists sat as a group high up on the back benches on the Left and so were naturally called “The Mountain” or the “Montagnards” (or Mountain People). Hence my new term of “up-wing” to add to “left-wing” and “right-wing”.

Frédéric Bastiat didn’t know where to sit in the Chamber in 1848

Here is another example of the problematical seating arrangements libertarians face when they get elected. When classical liberalism became a more potent force in the 1840s in England and France and yet another revolution broke in February 1848 the radical classical liberal economist Frédéric Bastiat had to sit in the middle of the Chamber, voting sometimes with the Right to oppose high taxation, government funded make work schemes for the unemployed, and redistribution proposed by the socialist Left, and sometimes with the Left to oppose restrictions of free speech, association (trade unions), and high taxation on basic food suopported by the conservative Right. Thus, it would appear Bastiat’s ideas were neither completely of the “Right” nor of the “Left” and this left him in a rather lonely position in a Chamber of 900 elected representatives.

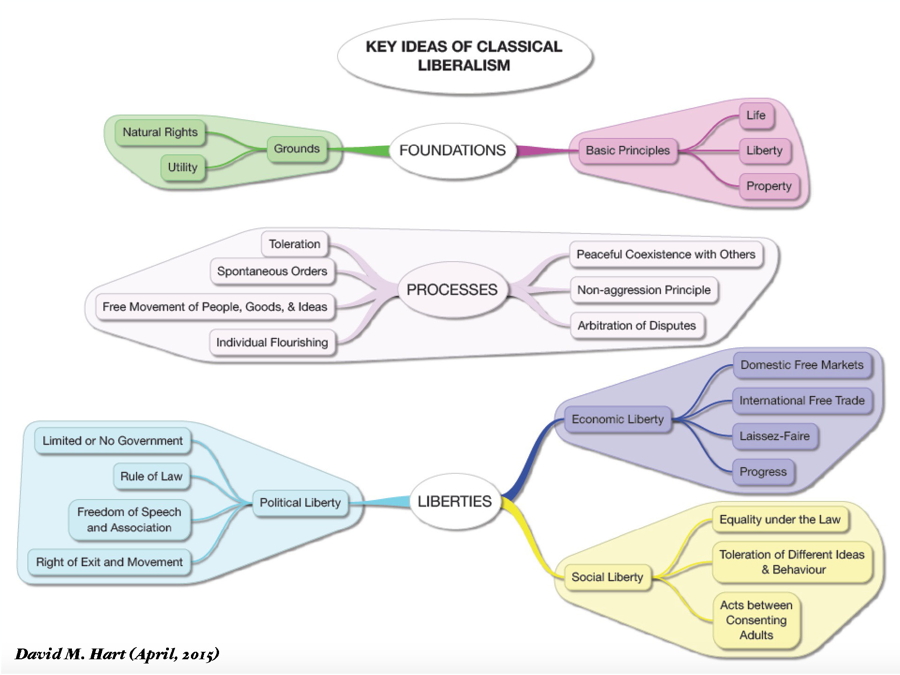

This problem of the etiquette of the proper seating arrangements in the Chamber speaks to a broader issue of what exactly is “libertarianism” or “radical classical liberalism” (I use the terms interchangeably)?

- Is it a leftwing political position (radical in the sense of challenging the status quo) or a rightwing one (in the sense of wanting to “conserve” some or all of the status quo)?

- What are libertarians trying to change and what are they trying to conserve?

- What happens if some of their views are considered to be “leftwing” while others are considered to be “rightwing”?

- Have the ideas of these liberals/libertarians changed over time (or have societies changed)?

- Is the tradition “leftwing-rightwing” political spectrum broad enough to include libertarians, or do we need another “wing” (“up-wing” or “up-mountain” for example)?

The Need for a New Left-Right Political Spectrum

What I want to argue is that the traditional 2 dimensional left-right political spectrum is completely inadequate both because

- it ignores the complexities of political views and policies in general, and

- in particular it leaves no place for the libertarian position since libertarians hold views which are regarded as “rightwing” or “conservative” (low taxes, small government, gun ownership, rule of law), as well as those that are better described as “leftwing” (freedom of speech, association, sexual preference), and those that don’t fit in at all (anti-war, drug laissez-faire, political orneriness).

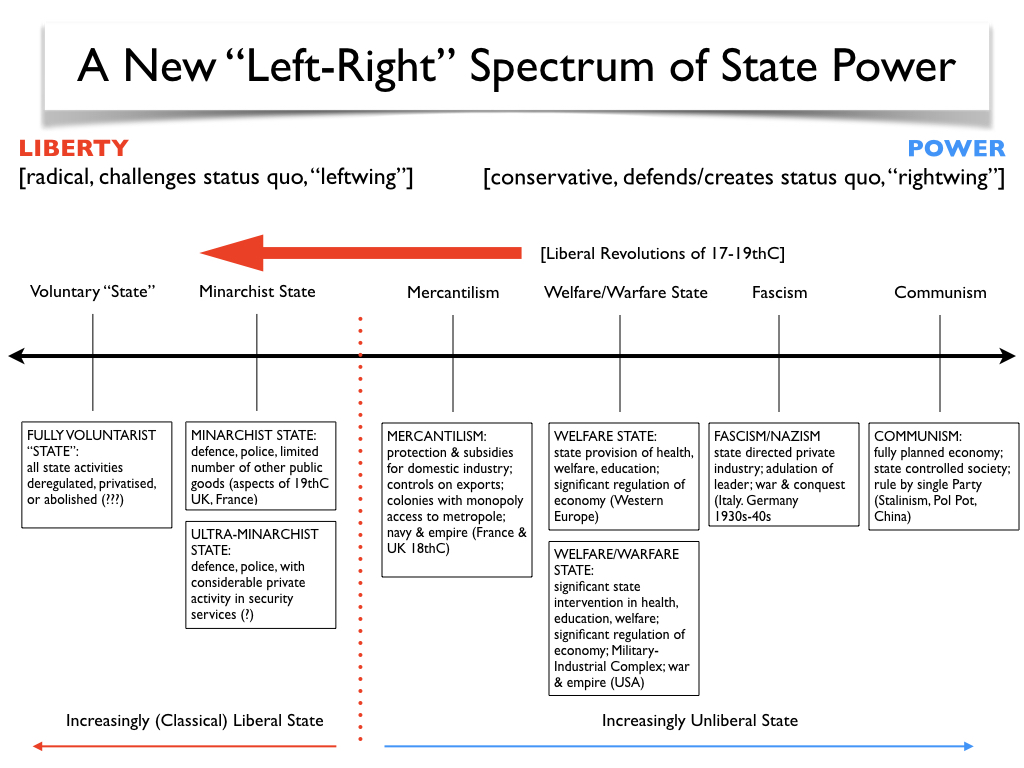

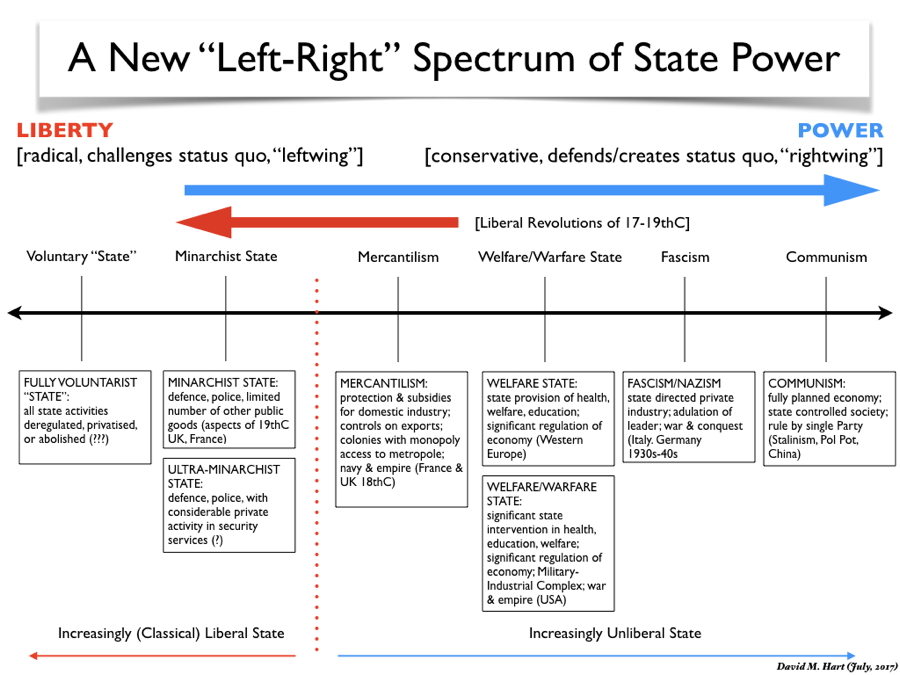

One solution is have a different 2-dimensional spectrum with complete “Liberty” on the left (as the position which challenges the status quo) and complete “Power” (or Statism) on the right (as the position which wants to defend the status quo or to create a new one).

I find this quite useful as a way of showing how societies have changed over time regarding how free or unfree they are. For example as a result of the “liberal revolutions” of the 18th and 19th centuries American and European societies moved from being less free to more free - thus moving from “right” (statist) to “left” (liberal) as the following graphs show:

Side note

Another solution is to use a 3-dimensional diagram (or more dimensions if you can understand the higher mathematics of multi-dimensional spaces), such as one dimension for economic liberties, another for political liberties, and a third for “personal” or some other kind of liberties.

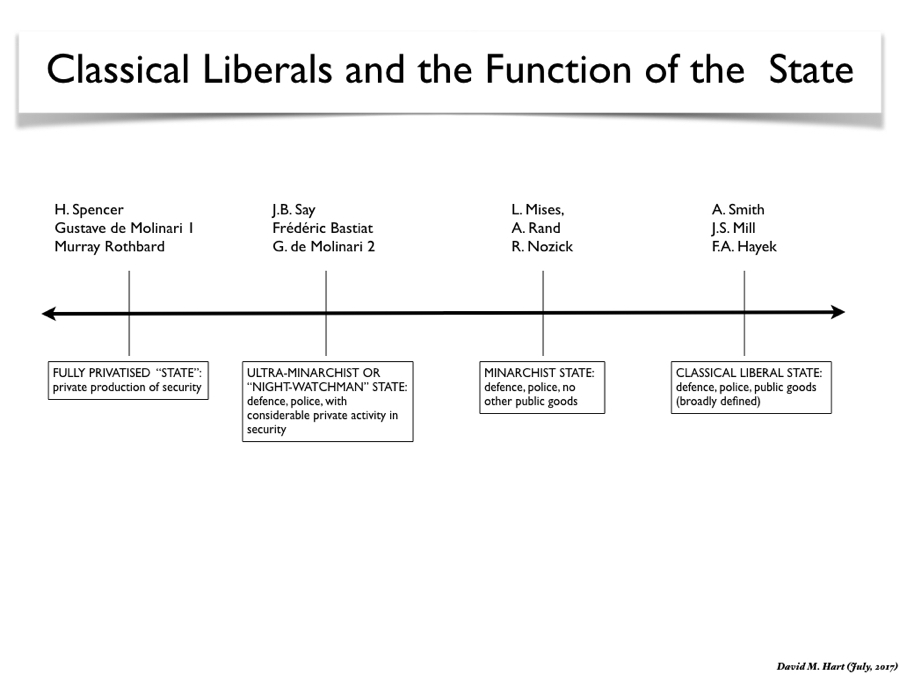

Liberals differ on what Functions the State should have

A further complication is that classical liberals/libertarians have differed and continue to do so on what they believe the proper functions of the state should be. Another version of my “New ‘Left-Right’ Spectrum of State Power” might make this clearer.

- on the “Left” are those that want to smallest possible (or even no) state, e.g. Rothbard, Molinari, Spencer

- on the “Right” are the older more traditional liberals like Adam Smith, JS Mill, and Hayek who want much more (but still limited compared to socialists) state activity.

The Consequences for Us

There are several consequences which follow from thinking about the political spectrum in this way:

- it helps us identify better who we are, what we believe, and we we came from

- it helps us see how we differ from other political groups and ideologies, what we have in common, and what we do not

- it shows us where there might be opportunities for alliances between libertarians and other groups who share one or two of our ideas but not all of them; there are opportunities to align with those on “the left” on some issues, and with “the right” on others

- it provides a strategy for arguing with friends and colleagues; if they come from “the left” begin talking to them about things we share with them and once you have won their trust it might be time to gently broach “right wing” issues which they reject but you beleive in (and vice versa for those on “the right”)

Until libertarian ideas are accepted by the majority (an unlikely event in my view anyway) this might be best we can hope for in the medium term if we want to spread out ideas to a broader audience.