“HOW AUSTRIAN WERE THE FRENCH: AN AUSTRO-AUSTRALIAN PERSPECTIVE”

By Dr. David M. Hart

MISES SEMINAR, SYDNEY, 26 NOVEMBER 2011

[Created: Niovember 15, 2011]

[Updated: April 22, 2012 ] |

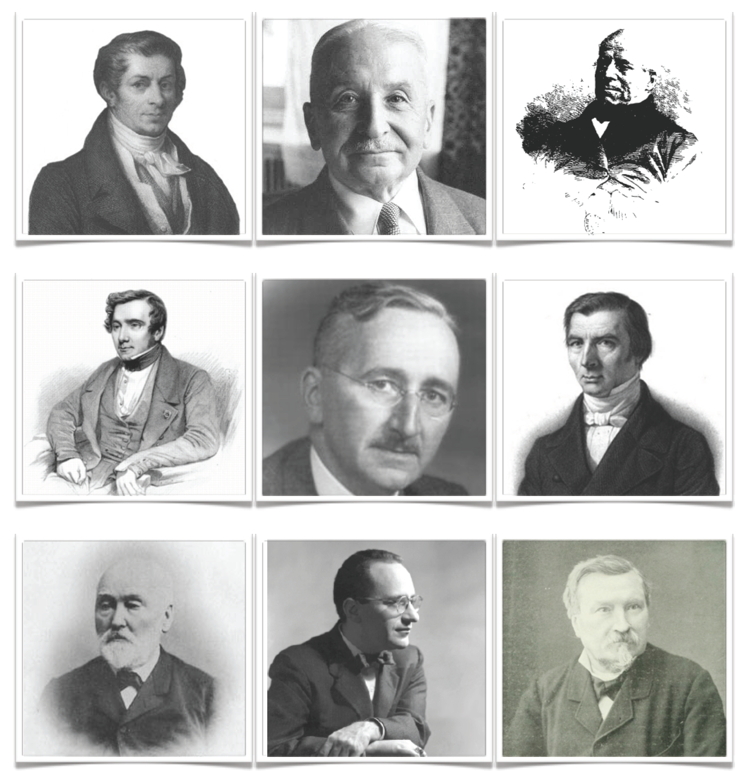

Images above (left to right, top to bottom):

- Jean-Baptiste Say (1767-1832); Ludwig von Mises (1881-1973); Charles Dunoyer (1786-1862)

- Augustin Thierry (1795-1856); Friedrich Hayek (1899-1992); Frédéric Bastiat (1801-1850)

- Jean-Gustave Courcelle-Seneuil (1813-1892); Murray Rothbard (1926-1995); Gustave de Molinari (1819-1912)

There is an overhead that was used for this talk [PDF 6.7 MB] and a video [MP4, 316 MB, 34 mins].

Introduction

French or Austrian? Austrian or French? The Chicken and the Egg Problem

The 19thC French classical liberals (CL) have been overshadowed by their better known (but not better) 19thC English cousins. Problem compounded by fact that leading Austrian theorists like Hayek completely misunderstand the French classical liberal tradition [See his essay “Individualism: True and False” (1945)]. Under the influence of Leonard Liggio and Murray Rothbard there has been some recognition of the important contributions made by the French classical liberal tradition, but unfortunately still not a full recognition. Problem further compounded by the fact that American scholars give far too much attention to the thought of the conservative (liberal?) writer Alexis de Tocqueville at the expence of his much more radically liberal and consistent contemporaries such as Bastiat. [Example of contrasting views: (1) Tocqueville in favour of French colonization of Algeria (civilizing mission) vs. Bastiat’s total condemnation; (2) AdT’s reaction to June Days uprising in Paris. He supported the use of troops in shooting the protesters - FB was out in the streets trying to rescue and aid the injured and persuading the troops to stop firing].

We have a “chicken and the egg” problem here. I might just as properly have asked the question “How French are the Austrians?” instead of asking “How Austrian were the French?”

- “How Austrian were the French?” - this question comes about because a number of Austrian economists (Rothbard and the Mises Institute) have seen many glimmerings of Austrian economic insights in the writings of the French CL school (Say, Bastiat). They ask themselves whether or not the RFCL were precursors or “proto-Austrians” before the full flowering of Austrian economics after the marginal revolution of 1870s? How many ideas concerning economic and social theory (history, sociology) were shared by the two schools of thought?

- “How French are the Austrians?” - one might also ask would Rothbard and his school within the Austrian tradition have turned down the anarcho-capitalist road if it were not for the seminal writings by Molinari in the late 1840s and mid-1850s? Did Leonard Liggio introduce Rothbard to these French writers? From this perspective one might ask “how French are the Austrians?” I would say they are considerably French [Hayek not at all French; Mises somewhat; and Rothbard (via Liggio) very French].

Some Personal Reflections

[On how an Australian Student was Introduced to Austrian Economics and the

French Radical Liberal School of Political Economy.]

I have spent most of my academic life reading about the the French school of

CL writing an honours thesis on Gustave de Molinari, a PhD on Charles Comte

and Charles Dunoyer, editing the collected works of Frédéric Bastiat for Liberty

Fund, and editing an anthology of 19th French CL for Routledge.

I was first made aware of the French CL by Leonard Liggio whom I met at a Cato Summer Seminar at Stanford University in August 1978 (lectures by Rothbard, Roy Childs, Leonard Liggio, Ralph Raico). LL had written but never submitted a PhD on Comte and Dunoyer and had introduced them to Rothbard who thought very highly of them as his remarks in his history of economic thought indicate. LL acted as a mentor to me when I expressed interest in doing research on the French CL school.

I decided to write my honours thesis on Molinari’s anarcho-capitalist thought in 1979, having been an intern at Cato (then in San Francisco) December-February 1978-79 working with LL when I photocopied nearly all of Molinari’s works held at the UC Berkeley Library.

Upon my return to Sydney (I was at Macquarie) I found there was an impressive collection of French free market material held by the Mitchell Library [Journal des Économistes, books published by the Guillaumin firm, Dictionnaire d’économie politique]. My theory is that before Federation NSW was a free trade state and that the librarians at the state library had it fully stocked with free market literature as that was state policy. Of course the free traders lost out to the protectionist Victorians when the Commonwealth of Australia was formed in January 1901, but I enjoyed the benefit of the free trade heritage of NSW when I came to write my thesis.

Greg Lindsay’s Centre for Independent Studies also played a role in furthering my research into the radical French CL. He allowed me to photocopy on his office machines the entire, very large, 2 volume Dictionnaire d’économie politique which was the summation of the radical French CL body of knowledge in the mid-19thC. I subsequently had them bound in an expensive thesis binding and have them with me to this day.

I would describe myself as an Australian Franco-Austro-anarcho-capitalist.

The Radical Liberal French School of Political Economy

Key Members of the 1st & 2nd Generations

Who were the main members of the radical French CL school?

- Founders (1st Generation) (key period 1814-1820):

- Jean-Baptiste Say (1767-1832)

- Traité d'économie politique (1803)

- Cours complet d'économie politique pratique (1828-33)

- Charles Comte (1782-1837)

- Traité de législation (1826)

- Traité de la propriété (1834)

- Charles Dunoyer (1786-1862)

- L'Industrie et la morale considérées dans leurs rapports avec la liberté (1825)

- Nouveau traité d'économie sociale (1830)

- De la liberté du travail (1845)

- Augustin Thierry (1795-1856)

- Dix ans d’études historiques (1834)

- Histoire de la conquête de l’Angleterre par les Normands (1825)

- Essai sur l’histoire de la formation et des progrès du Tiers état (1850)

- Jean-Baptiste Say (1767-1832)

The Radical French Classical Liberals (2nd Generation) (key period 1846-1856)

- Frédéric Bastiat (1801-1850)

- Economic Sophisms (1846, 1848)

- Property and Plunder (1848), The State (1848), Damn Money! (1849), What is Seen and What is Not Seen (1850), The Law (1850)

- Economic Harmonies (1850)

- Charles Coquelin (1802-1852)

- Du crédit et des banques (1848, 1859)

- Dictionnaire de l’Économie politique (1852)

- Jean-Gustave Courcelle-Seneuil (1813-1892)

- Traité théorique et practique d’économie politique (1856),

- Études sur la science sociale (1862)

- Gustave de Molinari (1819-1912)

- “The Production of Security” (1849)

- Les Soirées de la rue Saint-Lazare (1849)

- Cours d'Économie politique (1855)

- L'Évolution économique du dix-neuvième siècle: Théorie du progrès (1880)

- L'Évolution politique et la révolution (1884)

Chronological List of Key Works

Napoleonic & Restoration Periods (1800-1830)

- Say, Traité d'économie politique (1803)

- Dunoyer, L'Industrie et la morale considérées dans leurs rapports avec la liberté (1825)

- Thierry, Histoire de la conquête de l’Angleterre par les Normands (1825)

- Say, Cours complet d'économie politique pratique (1828-33)

- Comte, Traité de législation (1826)

The July Monarchy (1830-1848)

- Dunoyer, Nouveau traité d'économie sociale (1830)

- Comte, Traité de la propriété (1834)

- Thierry, Dix ans d’études historiques (1834)

- Dunoyer, De la liberté du travail (1845)Bastiat, Economic Sophisms (1846, 1848)

The Second Republic (1848-1852)

- Coquelin, Du crédit et des banques (1848, 1859)

- Bastiat, The State (1848)

- Molinari, “The Production of Security” (1849)

- Molinari, Les Soirées de la rue Saint-Lazare (1849)

- Thierry, Essai sur l’histoire de la formation et des progrès du Tiers état (1850)

- Bastiat, The Law (1850)

- Bastiat, Economic Harmonies (1850)

The Third Empire (1852-1870)

- Coquelin, Dictionnaire de l’Économie politique (1852)

- Molinari, Cours d'Économie politique (1855)

- Courcelle-Seneuil, Traité théorique et practique d’économie politique (1856),

- Courcelle-Seneuil, Études sur la science sociale (1862)

Assessment of their Contribution: The “Anti-Statist Moment” (1846-1855)

The Founders, or the First Generation, took political economy into new directions just after the turn of the century (Say); had a strong legal and historical perspective (CC and CD trained as lawyers, discovered Say’s economic thought in 1817; developed theory of history based upon class analysis and “industrialism”); Thierry history of rise of Third Estate and conquest theory.

Second Generation emerged in 1840s around Bastiat and Molinari. Radicalised by growth of socialism and outbreak of 1848 Revolution. Developed new ideas about interpersonal exchange of services, rent (Bastiat), production of security as just another economic activity governed by economic laws (Molinari), free banking (Coquelin, Courcelle-Senueil), social theory based upon idea of legal plunder (Bastiat); theory of human action (Courcelle-Seneuil, Études sur la science sociale (1862)).

There was something special about the revolutionary years of 1848-1850 within the French classical liberal movement. The outbreak of revolution in February 1848 led to a group of liberal radicals around Frédéric Bastiat (including the 29 year old Molinari) taking to the streets of Paris to distribute their pamphlets, wall posters, and magazine urging the citizens not to support the socialists and to support their radical free trade and free market ideas. Bastiat went on to take up a position within the Constituent Assembly and National Assembly of the new Second Republic. From his pen poured dozens of articles and pamphlets including his influential essays on "The State" (1848) and "The Law" (1850) until an early death from throat cancer struck him down on Christmas Eve 1850 in Rome. "The State" began as a one page article in his second revolutionary magazine Jacques Bonhomme in June 1848 and then as a revolutionary street poster. He left half-finished his magnum opus Economic Harmonies and a book never really started on A History of Plunder in which he planned to outline the historical emergence of the modern state over the previous 3 or 4 centuries and the liberal economic theory which explained it. Bastiat's ideas on "spoliation" (plunder) were taken up in more detail by Ambroise Clément in "De la spoliation légale' [Legal Plunder] in the JDE (July, 1848)

Meanwhile, the radical Belgian-French political economist Gustave de Molinari also turned to a new analysis of the state prompted no doubt by the extraordinary events of 1848. In the second half of 1848 Molinari began a revolutionary re-examination of the nature of the state and what might replace it in a fully free society. Given the recent history of the free trade movement in England and France (Richard Cobden's Anti-Corn Law League achieving its goal of eliminating protection in England in 1846; while Bastiat's Free Trade Association lost the crucial vote in France in 1847 to achieve the same thing) Molinari began to think that the same arguments which led the liberal political economists ("les économistes" in French) to argue for "free trade" led logically to the notion that they should also advocate "free government", i.e. a system in which the provision of security would not be monopolized by any body (whether it called itself "the state" or any other group) and where free competition would enable competing suppliers to enter the market to serve the needs of consumers.

There were two separate but related key insights in the evolution of Molinari's theory: firstly, that the first use of violence or coercion (or the threat of its use) were morally wrong under all circumstances (in other words the prohibition of violence was universal), and secondly that government's actions could only be described as a form of "legal" plunder and hence proscribed under any liberal moral or legal system. These were ideas developed by Bastiat in several of his writings but the full implications of them had not been drawn out fully until Molinari began his work in late 1848. The result was an essay called "De la production de la sécurité" [The Production of Security] which appeared in the Économistes' journal the Journal des Économistes in February 1849. His concluding sentences sums up his arguments nicely:

(A)t the risk of being considered utopian, we affirm that this is not disputable, that a careful examination of the facts will decide the problem of government more and more in favor of liberty, just as it does all other economic problems. We are convinced, so far as we are concerned, that one day groups will be established to agitate for free government, as they have already been established on behalf of free trade.

Soon after the appearance of this article Molinari produced a book later in 1849, Les Soirées de la rue Saint-Lazare; entretiens sur les lois économiques et défense de la propriété [Evenings on the Rue Saint-Lazare: Dicussions on Economic Laws and the Defence of Property], in which he developed his ideas further. It caused a sensation at one of the monthly meetings of the Société d'économie politique when Molinari's ideas where discussed. Equally upsetting to the other members of the Society apparently were Molinari's arguments against eminent domain, such was the rigour of his belief in individual property rights. After the coming to power of Louis Napléon and his coup d'état in December 1851 (he annointed himself emperor Napoléon III the following year), Molinari left Paris in disgust (and perhaps also as a precaution) and took up a position in Brussells teaching political economy. In 1855 he published his textbook based upon those lectures, Cours d'économie politique, professé au Musée royal de l'industrie belge, 2 vols. (Bruxelles: Librairie polytechnique d'Aug. Ecq, 1855), in which he elaborated further on his ideas on "la liberté de gouvernement" (free government), or in other words, his theory of anarcho-capitalism.

The late 1840s produced other very important books and articles which dramatically pushed the classical liberal movement in a more radical direction. Pocock once spoke of the "Machiavellian Moment" in the late renaissance period. I think we can confidently speak here of an "Anti-Statist Moment" in Paris between 1846 and 1855 which produced Charles Coquelin's book advocating free banking (1846), Molinari's essay on "The Production of Security" (1849), Bastiat's essay on "The State" (1848) and his book on Economic Harmonies (1850), Ambroise Clément's essay on "Legal Plunder" in the JDE (1848), and Molinari's treatise on political economy (1855) in which he further developed his ideas on the private provision of security services.

The Radicalism of the French Classical Liberals

What made them so “radical” (and in my view better than the English CL school)?

- strong believers in natural rights (individual liberty & property)

- strict laissez-faire advocates (free trade externally and total deregulation internally)

- very anti-statist

- anti-war and anti-empire

- notion of the important role played by the entrepreneur (Say’s invention)

- explored the idea of free banking - competitive note issue by private, competing banks (Coquelin)

- the idea of exploitation through the use of force (usually by governments) - the idea of “legal plunder” (Bastiat)

- class analysis view of history

- idea that value of goods and services are subjective to particular individuals and that there is no objective “thing” that gives something “value” (Bastiat’s idea that all exchanges are exchanges of “service for service”)

- the idea that all things are subject to market forces of supply and demand (pricing) and that competitive free markets are the best way to satisfy consumer demand - extended even to “production of security” (Molinari)

Thus, the radical French CL school are libertarian, but are they “Austrian”?

What makes the Austrian School “Austrian”?

The Austrian School as an Economic Theory

I believe that the “Austrian School” can be characterized as both an “economic” theory as well as a “social” theory which has important things to say about history and political/social structures (class).

Useful summary and definition of Austrian school understood strictly as an “economic theory” is provided by Pete Boettke. [Peter J. Boettke, "Austrian School of Economics" in the Concise Encyclopedia of Economics, Econlib <http://www.econlib.org/library/Enc/AustrianSchoolofEconomics.html>.]

The Science of Economics

- Proposition 1: Only individuals choose.

- Proposition 2: The study of the market order is fundamentally about exchange behavior and the institutions within which exchanges take place.

- Proposition 3: The “facts” of the social sciences are what people believe and think.

Microeconomics

- Proposition 4: Utility and costs are subjective.

- Proposition 5: The price system economizes on the information that people need to process in making their decisions.

- Proposition 6: Private property in the means of production is a necessary condition for rational economic calculation.

- Proposition 7: The competitive market is a process of entrepreneurial discovery.

Macroeconomics

- Proposition 8: Money is non-neutral.

- Proposition 9: The capital structure consists of heterogeneous goods that have multi-specific uses that must be aligned.

- Proposition 10: Social institutions often are the result of human action, but not of human design.

The Austrian School as a Social Theory

The modern Austrian School has been developed by the writings of Friedrich Hayek (1899-1992), Ludwig von Mises (1881-1973), and Murray Rothbard (1926-1995). Each of these thinkers developed alongside their economic theory a broader social theory which included history of ideas, economic history, political theory, and social analysis (including notions of class and exploitation). The latter was explicitly part of Mises’ social theory (“The Clash of Group Interests”) and most especially in the work of Rothbard. The “weak link” here is the political theory of Hayek who admitted many exceptions to the policy of laissez-faire that one might better classify him as a liberal-minded social democrat rather than as a hard-core laissez-faire classical liberal like Mises let alone an explicit anarcho-capitalist like Rothbard (see especially The Constitution of Liberty (1960)).

Here is my list of ideas and theories which constitute the Austrian School of Social Theory:

- methodology of radical individualism

- a theory of history based upon idea of exploitation by ruling elites (class)

- the notion that one’s property rights are violated when a person or group of persons uses force or the threat of force to acquire another person’s property (in other words “exploitation” occurs); and the related the idea that exploitation by one class of another class drives much of history

- laissez-faire in government policy

- anti-war and anti-empire

- a policy of free banking and hard money (gold backed currency)

- the importance of ideas in achieving radical social change (Hayek’s “Intellectuals

and Socialism”)

What makes the French School “Austrian”?

Is the radical French CL School Austrian in terms of Economic Theory?

Returning to Boettke’s definition of Austrian school understood strictly as an “economic theory” (I have put in bold those aspects of Boettke’s list which members of the radical French school (RFS) also believed to a large extent; in italic those aspects which the French partly believed.)

The Science of Economics

- Proposition 1: Only individuals choose. [Very strongly yes]

- Proposition 2: The study of the market order is fundamentally about exchange behavior and the institutions within which exchanges take place. [Very strongly yes]

- Proposition 3: The “facts” of the social sciences are what people believe and think. [This aspect of radical subjectivism is missing from RFS]

Microeconomics

- Proposition 4: Utility and costs are subjective. [Quite strongly yes - Bastiat was moving increasingly in this direction]

- Proposition 5: The price system economizes on the information that people need to process in making their decisions. [Half yes. French school recognized role of prices but not as transmitters of information à la Hayek]

- Proposition 6: Private property in the means of production is a necessary condition for rational economic calculation. [Half yes. French school recognized role of private property but not as part of rational economic calculation à la Hayek]

- Proposition 7: The competitive market is a process of entrepreneurial discovery. [Half yes. French school recognized importance of entrepreneur but not as process of discovery]

Macroeconomics

- Proposition 8: Money is non-neutral. [Half yes. Coquelin and other advocates of free banking recognized that banking had become politicized by being monopolized by the state]

- Proposition 9: The capital structure consists of heterogeneous goods that have multi-specific uses that must be aligned. [RFS had no theory of structure of production]

- Proposition 10: Social institutions often are the result of human action, but not of human design. [Very strongly yes. Bastiat’s idea of the “harmony of the market” is very much similar to this idea]

Area of agreement or shared ideas: 4/10 largely agreed/shared; 4/10 partly agreed/shared. Thus I would grade them about 6/10 or “half an Austrian” (if “an Austrian” was our unit of measurement - compare “utils” as unit of measurement for utility).

Is the radical French CL School Austrian in terms of Social Theory?

Since we have three important founders of the modern Austrian School (Hayek, Mises, Rothbard) another way we might ask this question is how Hayekian, how Misesian, or how Rothbardian, was the radical French CL school? My quick answer would be not very Hayekian, fairly Misesian, and very Rothbardian. To return to list above:

- methodology of radical individualism - individuals have natural rights

to liberty and property and are the basic foundation of society and the economy

a theory of exploitation - the violation of individual rights when an organized group uses violence to acquire property - a theory of history based upon idea of exploitation by ruling elites (class) - “legal plunder” - especially regarding the outbreak of the French Revolution and coming to power of Napoleon, rise of the Third Estate

- strict laissez-faire in government policy (free trade externally and total deregulation internally)

- anti-state, anti-war and anti-empire - many RFS satisfy Rothbard’s key question: “Do you hate the state?”

- a policy of free banking and hard money (gold backed currency) - competitive note issue by private, competing banks (Coquelin). No theory of inflation as no experience of fiat paper money (exception French assignats during revolution)

- the idea that all things are subject to market forces of supply and demand (pricing) and that competitive free markets are the best way to satisfy consumer demand - extended even to “production of security” (Molinari)

- the importance of ideas in achieving radical social change (Hayek’s “Intellectuals and Socialism”) - not articulated but practiced with key individual Guillaumin and his book selling, book publishing activities, headquarters meeting place for SEP, JDE, monthly dinners. Guillaumin like LF of the 19thC.