The Digital Library of Liberty and Power

"The Guillaumin Collection"

Introduction | Coding | Formats | Sources | A Note

[Visit the Collection to download the Books]

|

[Created: 23 Feb. 2023]

[Updated: February 23, 2023 ] |

Introduction to "The Guillaumin Collection"

I have named my collection of classic works about liberty and power the "Guillaumin Collection" in honour of the French publishing firm run by Gilbert-Urbain Guillaumin (1801-64) and his two daughters Félicité and Pauline, which published some 2,359 books, journals, dictionaries, and encyclopedias between 1837 and 1910 (see full list), and thus played a central role in the emergence of the “Paris School” of political economy (my paper and a list of key texts).

The books in the "Guillaumin Collection" are some of the most important works in the development of the classical liberal / libertarian tradition (see my list of “The Great Books of Liberty”). They are in their original language (English, French, or German), and are based upon either the first edition (such as Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations (1776) ) or the last edition published in the author's lifetime (such as Adam Smith’s Theory of Moral Sentiments (the 1st ed. appeared in 1759; the final revised edition appeared in 1790)).

These books have been more richly coded and have some features which other titles in the “Digital Library of Liberty and Power” do not have, in particular the original page numbers of the text, and a “citation tool” to help scholars cite a particular passage. For more information about this see the "Guide to Using the Citation Tool".

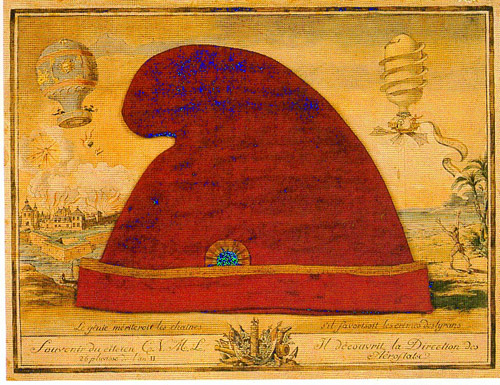

The Paris street where the Guillaumin firm was located |

|

| Right: An image of "Les Lois" (The Laws), a crown, and symbols of state power and justice,sitting on top of a collection of books. I found this in one of Guillaumin's books but can't recall where. | |

Details about the Coding and Formatting of the Texts

In order to make the texts more readable and more useful to scholars I have done the following:

- used formatting (“cascading style sheets”) which makes the texts look as much like the original as possible (within reason, given the vagaries of the period)

- inserted and highlighted the page numbers of the original edition (this is one way scholars might cite this work in their papers and articles)

- not split a word if it has been hyphenated across a new line or page (this will assist in making word searches)

- added unique paragraph IDs which make it possible for the citation tool to function (this is another way scholars can cite key passages / paragraphs in the text). The “citation tool” uses a Java script (“Wombat JS” at GitHub) to pluck out the unique paragraph ID number and create a direct link to that paragraph for citation purposes.

- retained the original spacing used by the author to separate sections of the text. In some particularly dense texts I have increased the space between paragraphs to make them more readable.

- created an indented “blocktext” for large quotations to help make the text more readable

- moved the Table of Contents to the beginning of the text, and inserted links to and back links from the major headings in the text (in order to assist navigation through long texts)

- placed the footnotes at the end of the book

- formatted margin notes to sit to the right (outside the main body of the text when viewing it on a large screen), or to “float right” within the text in the eBook formats which are only 600 pixels wide

- some quotes in foreign languages (Greek and Hebrew) have been replaced by screen snapshots

- produced the texts in a variety of formats

|

|

The Various Formats of the Texts

The texts in the collection are in a variety of formats:

- a facsimile PDF of the original edition down loaded from Google Books, Gallica, and other sources (see below for a fuller list). I believe it is important to be able to see what the original text looked like both for its own sake (I love old books) and because coding to HTML can sometimes be faulty, or badly done, and so the reader needs to be able to go “back to the source” to verify the accuracy of the coding

- an HTML version of the text. In many cases this is done by OCR (optical character recognition) which can introduce large numbers of errors which need to be corrected. The advantages is that the text is word-searchable and can be formatted in various ways to enhance readability on various electronic devices. In my collection there are three versions of the HTML texts:

- a basic HTML with few frills - this is the “standard HTML” format I used when I began the collection in 2010

- what I call an “enhanced HTML” with additional features which are described above. Most important are the original pages numbers and the citation tool. This version of the text is 750 pixels wide. Because the citation tool uses a Java script to work, the file needs to be read online for this feature to function.

- and what I call an “eBook HTML”. This version uses a special CSS (cascading style sheet) to improve the layout of the page, some style sheets are custom designed to suit unusual or more difficult texts. The eBook HTML does not have the citation tool so it can be downloaded and read as a self-contained file. These eBook HTMLs are 600 px wide and have justified text so they can be read more easily on portable devices.

- a variety of eBook versions of the text. From the “eBook HTML” version of the text a “text-based PDF” version is created (formatted for A4 size paper (sorry to my American friends!), as is an ePub version. Because these three versions (HTML, PDF, and ePub) are self-contained they are available for download either singly or bundled together (along with a copy of the facsimile PDF) in a zipped file for reading elsewhere.

|

|

The Sources used for the Texts

I began downloading facsimile PDFs of key keys from the Gallica digital books project of the Bibliothèque Nationale de France (BNF) and Google Books back in the late 1990s. The quality of these early scans were often very poor, as was the raw text which they produced using OCR (optical character recognition). They are better today but still require considerable and careful editing to be put into an acceptable form. Here is a list of some of the organisations which which I get the texts:

- Deutsche Digitale Bibliothek

- Deutsches Textarchiv (DTA)

- Gallica Bibliothèque Numérique

- Google Books

- Hathi Trust Digital Library

- Internet Archive

- McMaster University Archive for the History of Economic Thought

- Online Books Page (University of Pennsylvania)

- Oxford Text Archive (Boldlean Library)

- Wikisource: English - French - German

- University of Michigan - Text Creation Partnership

- Eighteenth Century Collections Online (ECCO)

- Early English Books Online (EEBO)

- Evans Early American Imprints (Evans)

|

|

A Note about Some Titles in the Collection

I should mention that a couple of texts in the collection are not strictly “classical liberal” or “libertarian” but are included here because of their influence on both these traditions of political thought. For example,

- the works of William Shakespeare - because of his insights into the nature of political and military power, and its effects on those who wield it and those who suffer from it. Shakespeare’s own political views are hard to determine exactly. It would be anachronistic to describe him as a “(classical) liberal” but he might be best describe as a “humanist” or at least a “sceptic”.

- The Federalist Papers written by Hamilton, Jay, and Madison (1788) - because they helped shape one of the great experiments to limit the power of the state by means of a written constitution and the division of power, but which in my view ultimately failed. Again, they are not classical liberal or libertarian, but they were part of the American ”conservative” tradition which has (or once had) some classical liberal and libertarian tendencies.