SAMUEL PUFENDORF,

The Whole Duty of Man according to the Law of Nature (1691)

|

|

| Samuel von Pufendorf (1632-1694) |

[Created: 4 October, 2023]

[Updated: 4 October, 2023 ] |

The Guillaumin Collection

|

This title is part of “The Guillaumin Collection” within “The Digital Library of Liberty and Power”. It has been more richly coded and has some features which other titles in the library do not have, such as the original page numbers, formatting which makes it look as much like the original text as possible, and a citation tool which makes it possible for scholars to link to an individual paragraph which is of interest to them. These titles are also available in a variety of eBook formats for reading on portable devices. |

Source

, The Whole Duty of Man According to the Law of Nature (London: Benjamin Motte, 1691).http://davidmhart.com/liberty/GermanClassicalLiberals/Pufendorf/1691-WholeDutyMan/index.html

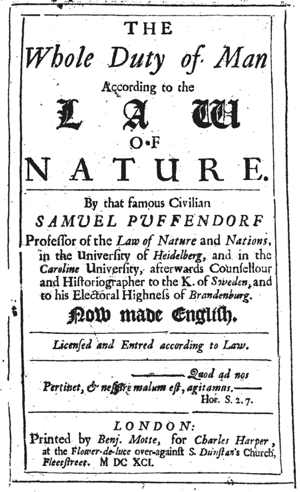

Samuel Pufendorf, The Whole Duty of Man According to the Law of Nature. By that famous Civilian Samuel Puffendorf Professor of the Law of Nature and Nations, in the University of Heidelberg, and in the Caroline University, afterwards Counsellour and Historiographer to the K. of Sweden, and to his Electoral Highness of Brandenburg. Now made English. Licensed and Entred according to Law. London: Printed by Benj. Motte, for Charles Harper, at the Flower-de-luce over-against S. Dunstan's Church, Fleetstreet. MDCXCI (1691). Anonymous translator.

This title is also available in a facsimile PDF of the original and various eBook formats - HTML, PDF, and ePub.

CONTENTS.

- To his Honour'd Friend Mr. GEORGE WHITE Of London, MERCHANT;

- TO THE READER.

- The AUTHOR'S PREFACE.

- Written by the same AUTHOR, and Translated by J. C.

- BOOK I.

- Chap. I. OF Human Actions. Pag. 1.

- II. Of the Rule of Human Actions, or of Laws in general. p. 25

- III. Of the Law of Nature. 33

- IV. Of the Duty of Man towards God, or, concerning Natural Religion. p. 50

- V. Of the Duty of Man towards himself. p. 64

- VI. Of the Duty of one Man towards another, and first of doing no Injury to any Man. p. 88

- VII. The Natural Equality of Men to be acknowledged. p. 98

- VIII. Of the mutual Duties of Humanity. p. 105

- IX. The Duty of Men in making Contract. p. 112

- X. The Duty of Men in Discourse. p. 131

- XI. The Duty of those that take an Oath. p. 138

- XII. Duties to be observed in acquiring Possession of Things. p. 145

- XIII. The Duties which naturally result from Man's Property in Things. p. 160

- XIV. Of the Price and Value of Things. p. 164

- XV. Of those Contracts in which the Value of things is presupposed, and of the Duties thence arising. p. 174

- XVI. The several Methods by which the Obligations arising from Contracts are dissolv'd. p. 191.

- XVII. Of Meaning or Interpretation. p. 196

- BOOK II.

- Chap. I. OF the Natural State of Men. p. 207

- II. Of the Duties of the married State. p. 220

- III. The Duty of Parents and Children. p. 228

- IV. The Duties of Masters and Servants. p. 237

- V. The impulsive Cause of Constituting Communities. p. 241

- VI. Of the internal Frame and Constitution of any State or Government. p. 249

- VII. Of the several Parts of Government. p. 259

- VIII. Of the several Forms of Government. p. 265

- IX. The Qualifications of Civil Government. p. 273

- X. How Government, especially Monarchical, is acquired. p. 276

- XI. The Duty of supreme Governours. p. 283

- XII. Of the special Laws of a Community. p. 293

- XIII. Of the Power of Life and Death. p. 299

- XIV. Of Reputation. p. 310

- XV. Of the Power of Governours over the Goods of their Subjects. p. 316

- XVI. Of War and Peace. p. 319

- XVII. Of Alliances. p. 329

- XVIII. The Duty of Subjects. p. 333

[Page]

[Page]

To his Honour'd Friend Mr. GEORGE WHITE Of London, MERCHANT;

This TRACTATE Concerning the Law of Nature IS Offer'd, Dedicated, Presented

BY His humblest and most obliged Servant, The Translator.

[Page]

TO THE READER.↩

THE Translator having observ'd, in most of the Disputes wherewith the present Age is disquieted, frequent Appeals made, and that very properly, from Laws and Ordinances of a meaner Rank to the everlasting Law of Nature, gave himself the Pains, to turn over several Writers on that Subject. He chanc'd, he thinks with great Reason, to entertain an Opinion that this Author was the clearest, the fullest and the most unprejudic'd of any he met with: and hereupon that he might the better possess himself of his Reasonings, he attempted to render the Work into Mother-Tongue, after he had first endeavoured to set several better hands upon the Undertaking, [Page] who all for one Reason or other declin'd the Toil. He thought when 'twas done, it might be as acceptable to one or other to read it, as it had been to himself to translate it. If he have not done right to the Author, as he hopes he has not miss'd in any material Point, he is very willing to be corrected.

The Work, 'tis true, is as it were, an Epitome of the Author's large Volume; but having been extracted and publisht by Himself, the Reader cannot be under any doubt, but that he has the Quintessence of what is there deliver'd. What is par'd off, being mostly Cases in the Civil Law, Refutations of other Authors, and some Notions too fine and unnecessary for a Manual.

Concerning the Author 'tis enough to say, that he has surely had as great regard paid him from Personages of the highest degree, as perhaps ever was given to the most learned of men; being invited from his Native Country, first by the Elector Palatine to be Professor of the Law of Nature and Nations [Page] in the University of Heidelberg; then by the King of Sweden to honour his new-raised Academy by accepting the same Charge therein, and afterwards being admitted of the Council and made Historiographer both to the same King, and to his Electoral Highness of Brandenburgh: Where, except he be very lately dead, he lives at this time in the greatest respect of all men of Sense and Understanding.

[Page]

The AUTHOR'S PREFACE.↩

HAD not the Custom which has so generally obtain'd among Learned men almost procur'd to itself the force of a Law, it might seem altogether superfluous to premise a Word concerning the Reason of the present Undertaking; the Thing itself plainly declaring my whole Design to be the giving as short and yet, if I mistake not, as plain and perspicuous a Compendium of the most material Articles of the Law of Nature, as was possible; and this, lest if those who betake themselves to this sort of Study should enter the vast Fields of Knowledge without [Page] having fully imbib'd the Rudiments thereof, should at first sight be terrified and confounded by the Copiousness and Difficulty of the Matters occurring therein. And at the same time it seems plainly a very expedient Work for the Publick that the minds of Youth especially should be early imbued with that Moral Learning, for which they will have such manifest occasion and so frequent use through the whole Course of the Lives. And although I have always look'd upon it as a Work deserving no great Honour, to Epitomize the larger Writings of others, and more especially ones own; yet having thus done out of Submission to the commanding Authority of my Superiors, I hope no honest man will blame me for having endeavour'd hereby the improvement of the Understandings of young Men more particularly; to whom so great regard is to be had, that whatsoever Work is undertaken for [Page] their sakes, though it may not be capable of great Acuteness or splendid Eloquence, yet it is not to be accounted unworthy of any mans Pains. Beside that no Man in his Wits will deny that these Principles thus laid down are more conducive to the understanding of all Law in general, than any Elements of the Law Civil can be.

And this might have suffic'd for the present, but I am minded by some, that it would not be improper to lay down some few Particulars, which will conduce much to a right Understanding of the Constitution of the Law of Nature, and for the better ascertaining its just Bounds and Limits. And this I have been the more ready to do, that I might on this occasion obviate the Pretences of some over-nice Gentlemen who are apt to pass their squeamish Censures on this sort of Learning, which in many Instances is wholly separate from their Province.

[Page]

Now 'tis very manifest, that Men derive the Knowledge of their Duty, and what is fit to be done, or to be avoided in this Life, as it were from three Springs or Fountain-Heads; to wit, from the Light of Nature, from the Laws and Constitutions of Countries, and from the special Revelation of Almighty God. From the first of these proceed all those most common and ordinary Duties of a man, more particularly those that constitute him a sociable Creature with the rest of Mankind; from the second are derived all the Duties of a Man, as he is a Member of any particular City or Common-wealth; from the third result all the Duties of a Christian Man. And from hence proceed three distinct Sciences; the first of which is of the Law of Nature, common to all Nations; the second is of the Civil or Municipal Law peculiar to each Country, which is or may be as manifold and various as there [Page] are different States and Governments in the World: the third is Moral Divinity, as it is contra-distinct to that Part of Divinity, which explains the Articles of our Faith.

Each of these Sciences have a peculiar way of proving their Maxims, according to their own Principles. The Law of Nature asserts that this or that thing ought to be done, because from right Reason it is concluded that the same is necessary for the Preservation of Society amongst men.

Of Civil Laws and Constitutions, the supreme Reason is the Will of the Lawgiver.

The Obligation of Moral Divinity lies wholly in this, because God in the sacred Scripture has so commanded.

Now as the Civil Law presupposes the Law of Nature, as the more general Science; so if there be any thing contained in the Civil Law, wherein the Law of Nature is altogether silent, we must not [Page] therefore conclude that the one is any ways repugnant to the other. In like manner if in Moral Divinity some things are delivered as from Divine Revelation, which by our Reason we are not able to comprehend, and which upon that score are above the reach of the Law of Nature; it would be very absurd from hence to set the one against the other, or to imagine that there is any real Inconsistency between these Sciences. On the other hand, in the Doctrin of the Law of Nature, if any things are to be presupposed, because so much may be inferr'd from Reason, they are not to be put in Opposition to those things which the holy Scripture on that Subject delivers with greater Clearness, but they are only to be taken in an abstracted Sense. Thus, for Example, from the Law of Nature, abstracted from the Account we receive thereof in holy Writ, there may be formed an Idea of the Condition [Page] and State of the first Man as he came into the World, only so far as is within the Comprehension of Humane Reason. Now to set those things in opposition to what is deliver'd in Sacred Writ concerning the same State, would be the greatest Folly and Madness in the World.

But as it is an easie matter to reconcile the Civil Law with the Law of Nature; so it seems a little more difficult to set certain Bounds between the same Law of Nature and Moral Divinity, and to define in what Particulars chiefly they differ one from the other.

And upon this Subject I shall deliver my Opinion briefly, not with any Papal Authority, as if I was exempted from all Error by any Peculiar Right or Priviledge, neither as one who pretends to any Enthusiastick Revelation; but only as being desirous to discharge that Province which I have undertaken, according to the best of my Ability. And, as [Page] I am willing to hear all Candid and Ingenuous Persons, who can inform me better, and am very ready to retract what I have said amiss; so I do not value those Pragmatical and Positive Censurers and Busie-bodies, who boldly concern themselves with things which no ways belong to them; of these Persons we have a very Ingenious Character given by Phaedrus: They run about, says he, as mightily concern'd, they are very busie even when they have nothing to do, they puff and blow without any occasion, they are uneasie to themselves, and troublesome to every body else.

Now the Chief Distinction, whereby these Sciences are separated from one another, proceeds from the different Source or Spring, whence each derives its Principles; and of which I have already discours'd. From whence it follows; if there be some things, which we are enjoyn'd in Holy Writ either to do or forbear, [Page] the Necessity whereof cannot be discover'd by Reason alone, they are to be look'd upon as out of the Cognizance of the Law of Nature, and properly to appertain to Moral Divinity.

Moreover in Divinity the Law is consider'd as it has the Divine Promise annex'd to it, and with relation to the Covenant between God and Man; from which consideration the Law of Nature abstracts, because the other derives it self from a particular Revelation of God Almighty, and which Reason alone could not have found out. Besides too there is this Great Difference, in that the main End and Design of the Law of Nature is included within the Compass of this Life only, and so thereby a Man is inform'd how he is to live in Society with the rest of Mankind: But Moral Divinity instructs a Man how to live as a Christian, who is not oblig'd to live honesty and vertuously in this World; [Page] but is besides in earnest expectation of the Reward of his Piety after this Life, and therefore he has his Conversation in Heaven, but is here only as a Stranger and a Pilgrim. For altho the Mind of Man does with very great ardency pursue after Immortality, and is extremely averse to its own Destruction, and thence it was that most of the Heathens had a strong perswasion of the separate State of the Soul from the Body, and that then Good Men should be rewarded, and Evil Men punish'd: yet notwithstanding such a strong Assurance of the certainty hereof, upon which the Mind of Man can firmly and entirely depend, is to be deriv'd only from the Word of God. Hence it is that the Dictates of the Law of Nature are adapted only to Humane Judicature, which does not extend it self beyond this Life; and it would be absurd in many respects to apply them to the Divine Forum, which [Page] concerns itself only about Theology. From whence this also follows, that, because Humane Judicature regards only the external Actions of Man, but can no ways reach the Inward Thoughts of the Mind, which do not discover themselves by any outward Sign or Effect; therefore the Law of Nature is for the most part exercised in forming the outward Actions of Men. But Moral Divinity does not content itself in regulating only the Exterior Actions; but is more peculiarly intent in forming the Mind, and its internal Motions agreeable to the good Pleasure of the Divine Being; disallowing those very Actions, which outwardly look well enough, but proceed from an impure and corrupted Mind. And this seems to be the Reason why the sacred Scripture doth not so frequently treat of those Actions, that are enjoyned under certain Penalties by Humane Laws, as it doth of those, which, as Seneca expresses it, [Page] are out of the reach of any such Constitutions. And this will manifestly appear to those, who shall carefully consider the Precepts and Virtues that are therein inculcated; although even those Christian Virtues do very much dispose the Minds of Men, towards the maintaining of Mutual Society; so likewise Moral Divinity does mightily promote the Practice of all the main Duties, that are enjoyned us in our Civil Deportment: So that if you should observe any one behave himself like a restless and troublesome Member in the Common-wealth, you may fairly conclude that the Christian Religion has made but a very slight impression on that Person, and that it has taken no Root in his Heart. And from these Particulars I suppose may be easily discovered not only the certain Bounds and Limits which distinguish the Law of Nature, as we have defin'd it, from Moral Divinity; but it may likewise [Page] be concluded that the Law of Nature is no ways repugnant to the Maxims of sound Divinity; but is only to be abstracted from some particular Doctrines thereof, which cannot be fathom'd by the help of Reason alone. From whence also it necessarily follows, that in the Science of the Law of Nature, a Man should be now considered, as being depraved in his very Nature, and upon that Account, as a Creature subject to many vile Inclinations: For although none can be so stupid, as not to discover in himself many Evil and Inordinate Affections, nevertheless, unless we were inform'd so much by Sacred Writ, it would not appear that this Rebellion of the Will, was occasioned by the first Mans Transgression; and consequently since the Law of Nature does not reach those Things which are above Reason, it would be very preposterous to derive it from the State of Man, as it was uncorrupt [Page] before the Fall; especially since even the greatest part of the Precepts of the Decalogue, as they are delivered in Negative Terms, do manifestly presuppose the depraved State of Man. Thus for Example, in the First and Second Commandment it seems to be supposed that Mankind was naturally prone to the belief of Polytheism and Idolatry. For if you should consider Man as in his Primitive State, wherein he had a clear and distinct Knowledg of the Deity, as it were by a peculiar Revelation; I do not see how it could ever enter into the Thoughts of such a one, to frame any thing to himself, to which he could pay Reverence instead of or together with the true God, or to believe any Divinity to reside in that which his own Hands had form'd; therefore there was no necessity of laying an Injunction upon him in Negative Terms, that he should not worship other Gods; but this Plain, [Page] Affirmative Precept would have been sufficient; Thou shalt love, honor and adore God, whom you know to have created both yourself and the whole Universe. And the same may be said of the Third Commandment, for why should it be forbidden in a Negative Precept, to blaspheme God, to such a one who had at the same time a clear and perfect Understanding of his Bounty and Majesty, and who was actuated by no inordinate Affections, and whose Mind did chearfully acquiesce in that Condition, wherein he was placed by Almighty God? How could such a one be Guilty of so great Madness? But he needed only to have been admonished by this Affirmative Precept, That he should glorifie the Name of God. But it seems otherwise of the Fourth and Fifth Commandments, which as they are Affirmative Precepts, neither do they necessarily presuppose the depraved State of [Page] Man, they may be admitted, Mankind being considered as under either Condition. But the thing is very manifest in relation to the other Commandments, which concern our Neighbour; for it would suffice plainly to have enjoyned Man, considered as he was at first created by God, that he should love his Neighbour, whereto he was beforehand enclined by his own Nature. But how could the same Person be commanded, that he should not kill, when Death had not as yet faln on Mankind, which entred into the World upon the account of Sin? But now there is very great need of such a Negative Command, when instead of loving one another, there are stir'd up so great Feuds and Animosities among Men, that even a great Part of them is owing purely to Envy, or an inordinate Desire of invading what belongs to another; so that they make no scruple not only of destroying [Page] those that are innocent, but even their Friends, and such as have done them signal Favors, and all this forsooth they are not ashamed to disguise under the specious pretence of Religion and Conscience. In like manner what need was there expresly to forbid Adultery among those married Persons, whose mutual Love was so ardent and sincere? Or what occasion was there to forbid Theft when as yet Covetousness and Poverty were not known, nor did any Man think that properly his own, which might be useful or profitable to another? Or to what purpose was it to forbid the bearing False Witness, when as yet there were not any to be found, who sought after Honor and Reputation to themselves, by Slandering and aspersing others with false and groundless Calumnies? So that not unfitly you may here apply the Saying of Tacitus, Vetustissimi Mortalium, nulla adhuc prava libidine, [Page] sine probro, scelere, eoque sine poena aut coercitionibus agebant; & ubi nihil contra morem cuperent, nihil per metum vetabantur. Whilst no corrupt Desires deprav'd Mankind, the first Men lived without Sin and Wickedness, and therefore free from Restraint and Punishment, and whereas they coveted nothing but what was their due, they were barr'd from nothing by Fear.

And these things being rightly understood may clear the way for removing this Doubt; whether the Law was different or the same in the Primitive State of Nature before the Fall? Where it may be briefly answer'd, that the most material Heads of the Law were the same in each State; but that many particular Precepts did vary according to the diversity of the Condition of Mankind; or rather that the same Summary of the Law was explain'd by divers, but not contrary, Precepts; according to the [Page] different State of Man, by whom that Law was to be observ'd. Our Saviour reduc'd the Substance of the Law to two Heads: Love God, and Love thy Neighbour: To these the whole Law of Nature may be referr'd, as well in the Primitive, as in the deprav'd State of Man; (unless that in the Primitive State there seems not any or a very small difference between the Law of Nature, and Moral Divinity.) For that Mutual Society, which we laid down as a Foundation to the Law of Nature, may very well be resolv'd into the Love of our Neighbour. But when we descend to particular Precepts, there is indeed a very great difference both in relation to the Commands and Prohibitions. And as to what concerns the Commands, there are many which have place in this State of Mankind, which seem not to have been necessary in the Primitive State: And that partly because they presuppose such a [Page] Condition, as, 'tis not certain, could happen to that most happy State of Mankind; partly because there can be no Notion of them, without admitting Misery and Death, which were unknown there: As for Instance, we are now enjoyn'd by the Precepts of the Law of Nature, not to deceive one another in buying or selling, not to make use of false Weights or Measures, to repay Money that is lent, at the appointed time. But it is not yet evident, whether if Mankind had continued without sin, there would have been driven any Trade and Commerce, as there is now in the World, or whether there would then have been any Occasion for the Use of Mony. In like manner if such kind of Communities, as are now adays, were not to be found in the State of Innocence, there would be then likewise no Occasion for those Laws, which are presupposed as requisite for the well ordering and Government [Page] of such Societies. We are also now commanded by the Law of Nature to succour those that are in want, to relieve those that are oppressed, to take care of Widows and Orphans. But it would be to no purpose to have inculcated these Precepts to those who were no ways subject to Misery, Poverty or Death. The Law of Nature now enjoyns us to forgive Injuries, and to use our utmost Endeavours towards the promoting of Peace amongst Mankind; which would be unnecessary among those who never offended against the Laws of Mutual Society. And this too is very evident in the Prohibitory Precepts which relate to the Natural not Positive Law. For altho every Command does virtually contain in itself a Prohibition of the opposite Vice; (as for instance, he that is commanded to love his Neighbour, is at the same time forbidden to do such Actions, as may any [Page] ways thwart or contradict this Duty of Love:) yet it seems superfluous that these things should be ordain'd by express Commands, where there are no disorderly Inclinations to excite Men to the committing such Wrongs. For the Illustration of which, this may be taken notice of, that Solon would by no Publick Law enact any Punishment for Parricides, because he thought that no Child could be guilty of so horrid an Impiety. The like whereof we may find in what is reported by Francis Lopez, in his History of the West-Indies, Chap. 207. concernning the People of Nicaragua; he tells us, that they had not appointed any Punishment for those who should kill their Prince; because, say they, there can be no Subject, who would contrive or perpetrate so base an Action. I am afraid it may savour too much of Affectation to enlarge any farther in the Proof of what is in itself so clear and evident. [Page] Yet I shall add this one Example fitted to the meanest Capacity. Suppose there are two Children, but of different Dispositions, committed to the Care of a certain Person; One whereof is Modest and Bashful, taking great Delight in his Studies; the other proves Unruly, Surly, giving himself over more to loose Pleasures, than to Learning. Now the Duty of both of these is the same, to follow their Studies; but the particular Precepts proper to each, are different; for it is sufficient to advise the former to what kind of Studies he must apply himself, at what time and after what manner they are to be followed: But as for the other, he must be enjoyned under severe Penalties, not to wander abroad, not to Game, not to sell his Books, not to get others to make his Exercises, not to play the good Fellow, not to run after Harlots. Now if any one should undertake in a set Discourse [Page] to declaim against these things to him of the contrary Temper, the Child may very well enjoyn him Silence, and bid him inculcate them to any Body else, rather than to him, who takes no Delight or Pleasure in such Practices. From whence I look upon it as manifest, that the Law of Nature would have a quite different Face, if we were to consider Man, as he was in his Primitive State of Innocence. And now since the Bounds and Limits of this Science, whereby it is distinguished from Moral Divinity, are so clearly set down, it ought at least to have the same Priviledges with other Sciences, as the Civil Law, Physick, Natural Philosophy and the Mathematicks; wherein if any Unskilful Person presum'd to meddle, assuming to himself the Quality of a Censor, without any Authority, he may fairly have that objected to him, which was formerly done by Apelles to Megabyzus who undertook to talk at random [Page] about the Art of Painting; Pray, said he, be silent, lest the Boys laugh at you, who pretend to talk of Matters you do not understand.

Now upon the whole, I am contented to submit my self to the Judgment of Discreet and Intelligent Persons; but as for Ignorant, and Spiteful Detracters, 'tis better to leave them to themselves, to be punished by their own Folly and Malice; since, according to the Ancient Proverb, The Ethiopian cannot change his Skin.

[Page]

Written by the same AUTHOR, and Translated by J. C.↩

THE History of Popedom, containing an Account of the Rise, Progress, and Decay thereof. Sold by C. Harper at the Flower-de-luce over against S. Dunstan's Church in Fleetstreet, and J. Hindmarsh at the Golden Ball over against the Royal Exchange, Cornhill.

[1]

THE Whole Duty of Man, According to the LAW of NATURE.

BOOK I.

CHAP. I.

Of Human Actions.↩

WHAT we mean here by I. What is Duty. the word Duty, is, that Action of a Man, which is regularly ordered according to some prescribed Law, so far as he is thereto obliged. To the understanding whereof it is necessary to premise somewhat, as well touching the nature of a Human Action, as concerning Laws in general.

[2]

BY a Human Action we mean not II. What a Human Action. every motion that proceeds from the faculties of a Man; but such only as have their Original and Direction from those faculties which God Almighty has endow'd Mankind withal, distinct from Brutes; that is, such as are undertaken by the Light of the Ʋnderstanding, and the Choice of the Will.

FOR it is not only put in the power III. Human Capacity. of Man to know the various things which appear in the World, to compare them one with another, and from thence to form to himself new Notions; but he is able to look forwards, and to consider what he is to do, and to carry himself to the performance of it, and this to do after some certain Manner, and to some certain End; and then he can collect what will be the Consequence thereof. Beside, he can make a Judgment upon things already done, whether they are done agreeably to their Rule. Not that all a mans Faculties do exert themselves continually, or after the same manner, but some of them are stir'd up in him by an internal Impulse; and when raised, are by the same regulated and guided. Neither beside hath a Man the same Inclinations [3] to every Object, but some he desires and for others he has an aversion: and often, though an Object of Action be before him, yet he suspends any motion towards it; and when many Objects offer themselves, he chuses one and refuses the rest.

AS for that Faculty therefore of comprehending IV. Human Ʋnderstanding. and judging of things, which is called the Ʋnderstanding, it must be taken for granted, first of all, That every Man of a mature Age, and entire Sense has so much Natural Light in him, as that, with necessary care and due consideration, he may rightly comprehend at least those general Precepts and Principles which are requisite in order to pass our lives here honestly and quietly; and be able to judge that these are congruous to the Nature of Man. For if this at least be not admitted within the bounds of our Humane Forum, men might pretend an invincible Ignorance for all their Miscarriages; because no man in Civil Judicature. foro humano can be condemned for having violated a Law which it was above his Capacity to comprehend.

[4]

THE Ʋnderstanding of Man, when V. Conscience rightly inform'd and probable. it is rightly inform'd concerning that which is to be done or omitted, and this so, as that he is able to give certain and undoubted Reasons for his Opinion, is wont to be call'd Conscience truly guided. But when a Man has indeed entertain'd the true Opinion about what is to be done or not to be done, the truth whereof yet he is not able to make good by reasoning; but he either drew such his Notion from his Education, way of living, Custom, or from the Authority of persons wiser or better than himself; and yet no reason appears to him that can persuade the contrary, this uses to be called Conscientia probabilis, Conscience grounded upon Probability. And by this the greatest part of Mankind are govern'd, it being the good fortune of few to be able to enquire into and to know the Causes of things.

AND yet it chances often, to some VI. Conscience doubting. Men especially in singular Cases, that Arguments may be brought on both sides, and they not be Masters of sufficient Judgment to discern clearly which are the strongest and most weighty. And this is call'd a doubting Conscience. In [5] which Case this is the Rule; as long as the Understanding is unsatisfied and in doubt, whether the thing to be done be good or evil, the doing of it is to be deferred. For to set about doing it before the Doubt is answered, implies a sinful design or at least a neglect of the Law.

MEN also oftentimes have wrong apprehensions VII. Error. of the matter, and take that to be true which is false; and then they are said to be in an Error; and this is called Vincible Error, when a man by applying due Attention and Diligence might have prevented his falling thereinto; and it's said to be Invincible Error, when the person with the utmost Diligence and Care that is consistent with the common Rules of Life, could not have avoided it. But this sort of Error, at least among those who give their Minds to improve the Light of Reason and to lead their Lives regularly, happens not in the common Rules of living, but only in peculiar matters. For the Precepts of the Law of Nature are plain; and that Legislator who makes positive Laws, both does and ought to take all possible Care, that they may be understood by those [6] who are to give obedience to them. So that this sort of Error proceeds only from a supine Negligence. But in particular Affairs 'tis easie for some Error to be admitted, against the will and without any fault of the person, concerning the Object and other Circumstances of the Action.

BUT where Knowledge simply is VIII. Ignorance. wanting it is called Ignorance. Which is two ways to be consider'd; first, as it contributes somewhat to the Action; and next, as it was in the person either against his will or not without his own fault. In the first respect Ignorance uses to be divided into efficacious and concomitant. That, is such as if it had not been, the present Action had not been undertaken: This, tho it had not been, it had not hindred the Undertaking. In the latter respect the Ignorance is either Voluntary or Involuntary. The first is, when it was chosen by the person, he rejecting the means of knowing the Truth, or suffering it to come upon him by not using such diligence as was necessary. The latter is, when a Man is ignorant of that, which he could not nor was obliged to know: And this again is twofold; for [7] either a man may indeed not be able to help his Ignorance for the present, and yet may be to blame because he continues in such a state; or else he may not only be for the present unable to conquer his Ignorance, but may also be blameless that he is fallen into such a Condition.

THE other Faculty which does peculiarly IX. The Will. distinguish Men from Brutes is called the Will, by which as with an internal Impulse Man moves himself to Action, and chuses that which best pleases him; and rejects that which seems unfit for him. Man therefore has thus much from his Will; first, that he has a power to act willingly, that is, he is not determin'd by any intrinsick Necessity to do this or that, but is Himself the Author of his own Actions; next, that he has a power to act freely, that is, upon the Proposal of one Object, he may act or not act, and either entertain or reject: or if divers Objects are proposed, he may chuse one and refuse the rest. Now whereas among human Actions some are undertaken for their own sakes, others because they subserve to the attaining of somewhat farther; that is, some are as [8] the End, and others as Means; as for the End, the Will is thus far concern'd, That being once known, this first approves it, and then moves vigorously towards the atchieving thereof, as it were driving at it with more or less earnestness; and this End once obtain'd it sits down quietly and enjoys its acquist with pleasure. For the Means, they are first to be approv'd, then such as are most fit for the purpose are chosen, and at last are applied to use.

BUT as Man is accounted to be the X. The Will unforc'd. Author of his own Actions, because they are voluntarily undertaken by himself; so this is chiefly to be observed concerning the Will, to wit, that its Spontaneity or natural Freedom is at least to be asserted in those Actions, concerning which a man is wont to give an Account before any human Tribunal. For where an absolute Freedom of choice is wholly taken away, there not the man who acts, but he that imposed upon him the Necessity of so doing, is to be reputed the Author of that Action, to which the other unwillingly ministred with his strength and Limbs.

[9]

FURTHERMORE, though the Will XI. The Will variously affected. do always desire good in general, and has continually an Aversion for Evil also in general; yet a great variety of Desires and Actions may be found among men. And this arises from hence, that all things that are good and evil do not appear purely so to Man, but mixt together, the good with the bad and the bad with the good; and because different Objects do particularly affect divers parts, as it were, of a Man; for instance, some regard that good Opinion and Respect that a Man has for himself; some affect the outward Senses; and some that Love of himself, from which he desires his own Preservation. From whence it is, that those of the first sort appear to him as decorous; of the second as pleasant; and of the last as profitable: And accordingly as each of these have made a powerful Impression upon a Man, it brings upon him a peculiar propensity that way-ward; whereto may be added the particular Inclinations and Aversions that are in most Men to some certain things. From all which it comes to pass, that upon any Action several sorts of Good and Evil offer themselves, which either are true or appear [10] so; which some have more, some less sagacity to distinguish with solidity of Judgment. So that 'tis no wonder that one man should be carried eagerly on to that, which another perfectly abhors.

BUT neither is the Will of Man always XII. The Will byass'd by Natural Inclinations. found to stand equally poised with regard to every Action, that so the Inclination thereof to this or that side should come only from an internal Impulse, after a due consideration had of all its circumstances; but it is very often pusht on one way rather than another by some outward Movements. For, that we may pass by that universal Propensity to Evil, which is in all Mortals, the Original and Nature of which belong to the Examination of another The Judgment of the Divines. Forum; first, a peculiar disposition of Nature puts a particular kind of byass upon the Will, by which some are strongly inclin'd to certain sorts of Actions; and this is not only to be found in single Men, but in whole Nations. This seems to proceed from the Temperature of the Air that surrounds us, and of the Soil; and from that Constitution of our Bodies which either was deriv'd to us in the Seed of our Parents, or was occasion'd in us by our Age, Diet, the [11] want or enjoyment of Health, the Method of our Studies or way of Living and Causes of that sort, beside the various formations of the Organs, which the Mind makes use of in the performance of its several Offices, and the like. And here, beside that a man may with due eare very much alter the temperament of his body and repress the exorbitances of his natural Inclination, it is to be noted, that how much power soever we attribute hereto, yet it is not to be understood to be of that force as to hurry a man into such a violation of the Law of Nature as shall render him obnoxious to the Civil Judicature, where evil Desires are not animadverted on, provided they break not forth into external Actions. So that after all the pains that can be taken to repel Nature, if it take its full swinge, yet it may so far be restrain'd as not to produce open Acts of Wickedness; and the Difficulty which happens in vanquishing those Propensities is abundantly recompensed in the Glory of the Conquest. But if these Impulses are so strong upon the mind, that they cannot be contained from breaking forth, yet there may be found a way, as it [12] were to draw them off, without Sin.

THE frequent Repetition of Actions of XIII. By Custom. the same kind does also incline the Will to do certain things; and the Propensity which proceeds from hence is called Habit or Custom, for it is by this that any thing is undertaken readily and willingly, so that the Object being presented, the Mind seems to be forced thitherward, or if it be absent, the same is earnestly desirous of it. Concerning which this is to be observed, that as there appears to be no Custom, but what a Man may by applying a due Care, break and leave off; so neither can any so far put a force upon the Will, but that a Man may be able at any time to restrain himself from any external Acts at least, to which by that he is urged. And because it was in the persons own Power to have contracted this Habit or no, whatsoever easiness it brings to any Action, yet if that Action be good, it loses nothing of its value therefore, as neither doth an evil thing abate ought of its Pravity. But as a good Habit brings Praise to a man, so an ill one shews his Shame.

IT is also of great consideration, whether XIV. By Passion. the mind be in a quiet and placid [13] state, or whether it be affected with those peculiar Motions we call the Passions. Of these it is to be known, that how violent soever they are, a man with the right use of his Reason may yet conquer them, or at least contain them without the bounds of Action. But whereas of the Passions some are raised from the appearance of Good, and others of Evil; and do urge either to the procuring of somewhat that is acceptable, or to the avoiding of what is mischievous, it is agreeable to Human Nature, that these should meet among men more favour and pardon, than those; and that according to such degrees, as the Mischief that excited them was more hurtful and intolerable. For to want a Good not altogether necessary to the preservation of Nature is accounted more easie, than to endure an Evil which tends to Natures destruction.

FURTHERMORE, as there are certain XV. By Intoxication. Maladies, which take away all use of the Reason either perpetually or for a time, so 'tis customary in many Countries, for men on purpose to procure to themselves a certain kind of Disease which goes off in a short time, but which very much confounds the Reasoning Faculty. [14] By this we mean Drunkenness; proceeding from certain kinds of Drink and Fumes, which incense and disturb the Blood and Spirits, thereby rendring men very prone to Lust, Anger, Rashness and immoderate Mirth; so that many by Drunkenness are set as it were beside themselves, and seem to have put on another Nature than that which they were of, when sober. But as this does not always take away the whole use of Reason; so as far as the person does willingly put himself in this state, it is apt to procure an Abhorrence rather than a favourable Interpretation of what is done by its Impulse.

NOW of Human Actions as those are XVI. Actions Involuntary. called Voluntary, which proceed from and are directed by the Will; so if any thing be done wittingly altogether against the Will, these are call'd Involuntary, taking the word in the narrowest sense; for taking it in the largest, it comprehends even those which are done through Ignorance. But Involuntary in this place is to signifie the same as forc'd; that is, when by an external Power which is stronger, a man is compell'd to use his Members in any Action, to which he yet signifies his [15] Dissent and Aversion by Signs, and particularly by counterstriving with his Body. Less properly those Actions are also called Involuntary, which by the Imposition of a great Necessity are chosen to be done, as the lesser Evil; and for the Acting whereof the person had the greatest abomination, had he not been set under such Necessity. These Actions therefore are called mixt. With Voluntary Actions they have this in common, that in the present State of things the Will chuses them as the lesser Evil. With the Involuntary they are after a sort the same, as to the Effect, because they render the Agent either not at all, or not so heinously blameable, as if they had been done spontaneously.

THOSE Human Actions then which XVII. Voluntary Actions imputable proceed from, and are directed by the Ʋnderstanding and the Will, have particularly this natural Propriety, that they may be imputed to the Doer; that is, that a Man may justly be said to be the Author of them, and be obliged to render an Account of such his Doing; and the Consequences thereof, whether good or bad are chargeable upon him. For there can be no truer reason why any Action [16] should be imputable to a Man, than that, he did it either mediately or immediately, knowingly and willingly; or that it was in his power to have done the same or to have let it alone. Hence it obtains as the prime Axiom in matters of Morality which are liable to the Human Forum; That every man is accountable for all such Actions, the performance or omission of which were in his own Choice. Or, which is tantamount, That every Action, capable of human direction, is chargeable upon him who might or might not have done it. So on the contrary, no man can be reputed the Author of that Action, which neither in itself nor in its cause, was in his Power.

FROM these Premises we shall deduce XVIII. Conclusions from the Premises. some particular Propositions, by which shall be ascertain'd, What every man ought to be accountable for; or, in other words, which are those Actions and Consequences of which any one is to be charged as Author.

NONE of those Actions which are The first Conclusion. done by another man, nor any operation of whatsoever other things, neither any Accident, can be imputable to another person, but so far forth as it was in his [17] Power, or as he was obliged to guide such Action. For nothing is more common in the world, than to subject the Doings of one Man to the Manage and Direction of another. Here then, if any thing be perpetrated by one, which had not been done, if the other had performed his Duty and exerted his Power; this Action shall not only be chargeable upon him who immediately did the fact, but upon the other also who neglected to make use of his Authority and Power. And yet this is to be understood with some restriction; so as that Possibility may be taken morally, and in a large sense. For no Subjection can be so strict, as to extinguish all manner of liberty in the person subjected, but so that 'twill be in his Power to resist and act quite contrary to the direction of his Superior; neither will the state of Human Nature bear, that any one should be perpetually affix'd to the side of another, so as to observe all his motions. Therefore when a Superiour has done every thing that was required by the Rules of his Director-ship, and yet somewhat is acted amiss, this shall be laid only to the charge of him that did it. Thus whereas Man exercises dominion over other Animals, [18] what is done by them to the detriment of another, shall be charg'd upon the Owner, as supposing him to have been wanting of due Care and Circumspection. So also all those Mischiefs which are brought upon another, may be imputed to that person, who when he could and ought, yet did not take out of the way the Cause and Occasion thereof. Accordingly it being in the power of Men to promote or suspend the Operations of many Natural Agents, whatsoever Advantage or Damage is wrought by these, they shall be accountable for, by whose application or neglect the same was occasion'd. Beside, sometimes there are extraordinary Cases, when a man shall be charg'd with such Events as are above human Direction, as when God shall do particular Works with regard to some single person. These and the like Cases being excepted, for all the rest it suffices, if a Man can give an Account of his own doings.

WHATSOEVER Qualifications a XIX. The second Conclusion. Man hath or hath not, which it is not in his power to exert or not to exert, must not be imputed to him, unless so far as he is wanting in Industry to supply such Natural [19] Defect, or does not rowse up his native Faculties. So because no man can give himself an Acuteness of Judgment and Strength of Body, therefore no one is to be blamed for want of either, or commended for having them, except so far as he improv'd, or neglected the cultivating thereof. Thus Clownishness is not blameable in a Rustic, but in a Courtier or Citizen. And hence it is, that those Reproaches are to be judg'd extremely absurd, which are grounded upon Qualities, the Causes of which are not in our power, as, Short Stature, a deform'd Countenance and the like.

THOSE things which are done XX. The third Conclusion. through invincible Ignorance are not imputable. Because we cannot properly direct our Action, unless by the Light of the Understanding; (and 'tis here supposed Man is unable to procure such Light) neither are we to blame that we cannot. Now in the common affairs of Life, the word Possible is to be morally understood, and by Ability is meant that Faculty, Diligence and Circumspection which is commonly judg'd to suffice, and which is well supported with probable reasons.

[20]

Ignorance of, or Error concerning the XXI. The fourth Conclusion. Laws and that Duty, which is incumbent upon every man, does not excuse from blame. For whosoever imposes Laws and Services, is wont and ought to take care that the Subject have notice thereof. And these Laws and Rules of Duty generally are and should be ordered to the Capacity of such Subject, if they are such as he is oblig'd to know and remember. Hence, he who is the Cause of the Ignorance shall be bound to answer for those Actions which are the effects thereof.

HE who, not by his own fault, wants XXII. The fifth Conclusion. an opportunity of doing his Duty, shall not be accountable, because he has not done it. Now to a fair occasion these four things are requisite; 1. That an Object of Action be ready: 2. That a proper Place be had, where we may not be hindred by others, or receive some Mischief: 3. That we have a fit Time, when business of greater Necessity is not to be done, and which may be seasonable for other matters which concur to the Action: and 4. lastly, That we have natural Force sufficient for the performance. For since an Action cannot be atchiev'd without these, 'twould be absurd to blame a man for [21] not acting, when he had not an opportunity so to do. Thus a Physician cannot be accused of Sloth, when no body is sick to employ him. Thus no man can be liberal, who wants it himself. Thus he cannot be reproved for burying his talent, who having taken a due care to set himself in a useful Station, has yet miss'd of it: though it be said, To whom much is given, from him much shall be required. Thus we cannot blow and suck all at once.

NO man is accountable for not doing XXIII. The sixth Conclusion. that which exceeded his Power, and which he had not strength sufficient to hinder or accomplish. Hence that Maxim, To Impossibilities there lies no Obligation. But this Exception must be added, Provided, that by the persons own fault he has not impair'd, or lost that strength which was necessary to the Performance; for if so, he is to be treated after the same manner, as if he had all that power which he might have had: For otherwise it would be easie to elude the performance of any difficult Obligation, by weakening ones self on purpose. XXIV. The seventh Conclusion.

NEITHER can those things be imputable, which one acts or suffers by Compulsion. [22] For it is supposed, that 'twas above his power to decline or avoid such doing or suffering. But we are said after a twofold manner to be compell'd; one way is, when another that's stronger than us violently forces our Members to do or endure somewhat: the other, when one more powerful shall threaten some grievous Mischief (which he is immediately able to bring upon us) unless we will, as of our own accord, apply our selves to the doing of this, or abstain from doing that. For then, unless we are expresly oblig'd to take the Mischief to our selves which was to be done to another, he that sets us under this Necessity, is to be reputed the Author of the Fact; and the same is no more chargeable upon us, than a Murder is upon the Sword or Ax which was the Instrument.

THE Actions of those who want the XXV. The eighth Conclusion. use of their Reason are not imputable; Because they cannot distinguish clearly what they do, and bring it to the Rule. Hitherto appertain the Actions of Children, before their reasoning Faculties begin to exert themselves. For though they are now and then chid or whipt for what they do; yet this is not as if they had [23] deserv'd Punishment, properly so called in the Human Forum; but barely by way of Discipline and in order to their Amendment; lest by their tricks they become troublesome to others, or get ill habits themselves. So also the doings of Franticks, Crackbrains and Dotards are not accounted Human Actions, nor imputable to those who contracted such incapacitating Disease, without any fault of their own.

LASTLY, A man is not chargeable XXVI. The ninth Conclusion. with what he seems to do in his Dreams; unless by indulging himself in the day time with such Thoughts, he has deeply impress'd the Ideas of such things in his mind; (though matters of this sort can rarely be within the cognizance of the Human Forum.) Otherwise the Phansie in sleep is like a Boat adrift without a Guide, so that 'tis impossible for any man to order what Ideas it shall form.

BUT concerning the Imputation of another XXVII. Imputation of anothers Actions. mans Actions it is somewhat more distinctly to be observed, that sometimes it may so happen, that an Action ought not at all to be charged upon him that immediately did it, but upon another who made use of this only as an Instrument. But it is more frequent, that it should [24] be imputed both to him who perpetrated the thing, and to the other, who by doing or omitting something shew'd his concurrence to the Action. And this is chiefly done after a threefold manner; either, 1. As the other was the principal Cause of the Action, and this less principal, or, 2. As they were both equally concern'd; or, 3. As the other was less principal, and he that did the act was principal. To the first sort belong those who shall instigate another to any thing by their Authority; those who shall give their necessary Approbation, without which the other could not have acted; those who could and ought to have hindred it, but did not. To the second Class appertain, those who order such a thing to be done or hire a man to do it; those who assist; those who afford harbour and protection; those who had it in their Power, and whose Duty it was to have succoured the wronged person, but refused it. To the third sort are referred such as are of counsel to the Design; those that encourage and commend the Fact before it be done; and such as incite men to sinning by their Example, and the like.

[25]

CHAP. II.

Of the Rule of Human Actions, or of Laws in general.↩

BECAUSE all Human Actions depend I. The necessity of a Rule. upon the Will, and have their estimate according to the concurrence thereof; but the Wills of single men are not always the same, and those of other men run divers ways; therefore to preserve Decency and Order among Mankind, it was necessary there should be some Rule, by which they should be regulated. For otherwise, if where there is so great a Liberty of the Will, and such variety of Inclinations and Desires, any man might do whatsoever he had a mind to, without any regard to some stated Rule, it could not but give occasion to vast Confusions among Mankind.

THIS Rule is called Law; which is II. Law. a Decree by which the Superior obliges one that is subject to him, to accommodate his Actions to the directions prescribed therein.

[26]

THAT this Definition may the better III. Obligation. be understood, it must first be enquired, What is an Obligation? whence is its Original? who is capable of lying under an Obligation? and who it is that can impose it? Obligation then is usually said to be that rightful Bond, by which a man is necessitated to do somewhat. That is, hereby a Bridle, as it were is put upon our Liberty; so that though the Will does actually drive another way, yet we find our selves hereby struck as it were with an internal Sense, that if our Action be not perform'd according to the prescript Rule we cannot but confess we have not done right; and if any mischief happen to us upon that account, we may fairly charge our selves with the same; because it might have been avoided, if the Rule had been follow'd as it ought.

AND there are two reasons why Man IV. Man subject to Obligation. should be subject to an Obligation; one is, because he is endow'd with a Will, which may be divers ways directed, and so be conform'd to a Rule; the other, because Man is not exempt from the power of a Superior. For where the Faculties of any Agent are by Nature form'd only for one way of acting, there 'tis to no [27] purpose to expect any thing to be done of choice: and to such a Creature 'tis in vain to prescribe any Rule; because 'tis uncapable of understanding the same or conforming its actions thereto. Now if there be any one who has no Superior, then there is no power that can of right impose a Necessity upon him; and if he perpetually observes a certain Rule in what he does, and constantly abstains from doing many things, he is not to be understood to act thus from any Obligation that lay upon him, but from his own good pleasure. It will follow then, that He should be capable of Obligation, who has a Superior, and is able to understand the Rule prescribed, and is endued with a Will which may be directed several ways; and yet which (when the Law is promulg'd by his Superior) knows he cannot rightly depart therefrom. And with all these Faculties 'tis plain Mankind is furnish'd.

AN Obligation is superinduc'd upon V. Who can oblige. the Wills of Men properly by a Superior, that is, not only by such a one as being greater or stronger, can punish Gainsayers; but by him who has just reasons to have a power to restrain the Liberty of our Will at his own pleasure. Now when [28] any man has either of these, as soon as he has signified what he would have, it necessarily stirs up in the mind of the party concern'd Fear mixt with Reverence; towards the first in contemplation of his Power; and toward the second for the sake of those other Reasons, which even without Fear, ought to allure any man to a compliance with his Will. For he that can give me no other reason for putting me under an Obligation against my Will, beside this, that he's too strong for me, he truly may so terrifie me, that I may think it better to obey him for a while than suffer a greater Evil; but when this Fear is over, nothing any longer hinders, but that I may act after my own choice and not his. On the contrary he that has nothing but Arguments to prove that I should obey him, but wants Power to do me any Mischief, if I deny. I may with Impunity slight his commands, except one more potent take upon him to make good his despised Authority, Now the Reasons upon which one man may justly exact Subjection from another, are; If he have been to the other the Original of some extraordinary Good; and if it be plain, that he designs [29] the others Welfare, and is able to provide better for him than 'tis possible for himelf to do; and on the same account does actually lay claim to the Government of him: and lastly if any one does voluntarily surrender his Liberty to another, and subject himself to his Direction.

FURTHERMORE, that a Law may VI. The Legislator and the true meaning of the Law to be known. exert its force in the minds of those to whom it is promulg'd, it is required, that both the Legislator and the Law also be known. For no man can pay obedience, if he know not whom he is to obey, and what he is to perform. Now the knowledge of the Legislator is very easie; because from the light of Reason 'tis certain the same must be the Author of all the Laws of Nature, who was the Creator of the Ʋniverse: Nor can any man in Civil Society be ignorant who it is that has power over him. Then for the Laws of Nature, it shall be hereafter declared how we come to the knowledge of them. And as to the Laws of a mans Country or City, the Subject has notice given of them by a Publication plainly and openly made. In which these two things ought to be ascertain'd, that the Author of the Law is he, who hath the supreme Authority [30] in the Community, and that this or that is the true meaning of the Law. The first of these is known, if he shall promulge the Law with his own Mouth, or deliver it under his own Hand; or else if the same be done by such as are delegated to that purpose by him: whose Authority 'tis in vain to call in question, if it be manifest, that such their acting belongs to that Office they bear in the Publick, and that they are regularly plac'd in the Administration thereof; if these Laws are to be put judicially in Execution, and if they contain nothing derogatory to the Sovereign Power. That the latter, that is, the true Sense of the Law be known, it is the Duty of those who promulge it, in so doing to use the greatest Perspicuity and Plainness; and if any thing obscure do occur therein, an Explanation is to be sought of the Legislator, or of those who are publickly constituted to give judgment according to Law.

OF every perfect Law there are two VII. Two parts of a perfect Law. parts: One, whereby it is directed what is to be done or omitted: the other, wherein is declared what punishment he shall incur, who neglects to do what is commanded, or attempts that which is [31] prohibited. For as, through the Pravity of Human Nature ever inclining to things forbidden, it is to no purpose to say, Do this, if no Punishment shall be undergone by him who disobeys; so it were absurd to say, You shall be punish'd, except some reason preceded, by which a Punishment was deserv'd. Thus then all the force of a Law consists in signifying what the Superior requires or forbids to be done, and what Punishment shall be inflicted upon the Violators. But the power of obliging, that is, of imposing an intrinsick Necessity; and the power of forcing, or by the proposal of Punishments compelling the Observation of Laws, is properly in the Legislator, and in him to whom the Guardianship and Execution of the Laws is committed.

WHATSOEVER is enjoyn'd by any VIII. Other Essentials. Law ought not only to be in the power of him to perform on whom the Injunction is laid, but it ought to contain somewhat advantageous either to him or others. For as it would be absurd and cruel to exact the doing of any thing from another, under a Penalty, which it is and always was beyond his power to perform; so it would be silly and to no [32] purpose to put a restraint upon the natural Liberty of the Will of any man, if no one shall receive any benefit therefrom.

BUT though a Law does strictly include IX. Power of Dispensing. all the Subjects of the Legislator who are concern'd in the matter of the same, and whom the said Legislator at first intended not to be exempted; yet sometimes it happens that particular persons may be clear'd of any obligation to such Law: and this is call'd Dispensing. But as he only may dispense in whose power it is to make and abrogate the Law; so great care is to be taken, lest by too frequent Dispensations and such as are granted without very weighty reasons, the Authority of the Law be shaken and occasion be given of Envy and Animosities among Subjects.

YET there is a great difference between X. Equity. Equity and Dispensing: Equity being a Correction of that in which the Law, by reason of its General Comprehension was deficient; or an apt Interpretation of the Law, by which it is demonstrated, that there may be some peculiar Case which is not comprized in the Ʋniversal Law, because if it were, some Absurdity would follow. For it being [33] impossible that all Cases, by reason of their infinite Variety, should be either foreseen or explicitely provided for; therefore the Judges, whose office it is to apply the general Rules of the Laws to special Cases, ought to except such from the Influence of them, as the Lawgiver himself would have excepted, if he were present, or had foreseen such Cases.

NOW the Actions of men obtain certain XI. Actions allowable good and bad. Qualities and Denominations from their relation to and agreement with the Law of Morality. And all those Actions, concerning which the Law has determin'd nothing on either side, are call'd allowable or permitted. Altho sometimes in ordinary Law-Cases, where all matters cannot be examin'd with the greatest accuracy, those things are said to be allowable, upon which the Law has not assign'd some Punishment, though they are in themselves repugnant to Natural Honesty. And then those Actions which are consonant to the Law are good, those that are contrary to it are call'd bad: But that any Action should be good, 'tis requisite, that it be exactly agreeable in every point to the Law; whereas it may be evil, if it be deficient in one point only.

[34]

As for Justice it is sometimes the Attribute XII. Justice of Persons. of Actions, sometimes of Persons. When it is attributed to Persons, 'tis usually defin'd to be, A constant and perpetual desire of giving every one their own. For he is call'd a just man, who is delighted in doing righteous things, who studies Justice, and in all his Actions endeavours to do that which is right. On the other side, the unjust man is he that neglects the giving every man his own, or, if he does, 'tis not because 'tis due, but from expectation of Advantage to himself. So that a just man may sometimes do unjust things, and an unjust man that which is just. But the just does that which is right, because he is so commanded by the Law; and acts the contrary only through Infirmity; whereas the wicked man does a just thing for fear of the Punishment which is the Sanction of the Command, but he acts wrongfully from the naughtiness of his heart.

BUT when Justice is attributed to XIII. Of Actions. Actions, then it is nothing else but a right application of the same to the Person. And a just Action done of choice, or knowingly and wittingly, is applied to the person to whom it is due. So that the [35] Justice of Actions differs from Goodness chiefly in this, that the latter simply denotes an agreement with the Law, whereas Justice also includes the regard they have to those persons upon whom they are exercised. Upon which account Justice is called a Relative Virtue.

MEN do not generally agree about XIV. Division of Justice. the Division of Justice. The most receiv'd Distinction is, into Ʋniversal and Particular. The first is, when every Duty is practised and all right done to others, even that which could not have been extorted by force, or by the rigor of Law. The latter is, when that Justice only is done a man, which in his own right he could have demanded; and this is wont to be again divided into Distributive and Commutative. The Distributive takes place in Contracts made between a Society and its Members concerning fair partition of Loss and Gain according to a rate. The Commutative is mostly in Bargains made upon even hand about things and doings relating to Traffick and Dealing.

KNOWING thus, what Justice is, XV. Injustice what. 'tis easie to collect what is Injustice. Where it is to be observ'd, that such an unjust Action is called Wrong-doing, which [36] is premeditately undertaken, and by which a violence is done upon somewhat which of absolute right was another mans due, or which by like right he one way or other stood possess'd of. And this Wrong may be done after a threefold manner, 1. if that be denied to another which in his own right he might demand (not accounting that which from Courtesie or the like Virtue may be anothers due); or 2. if that be taken away from another, of which by the same right then valid against the Invader, he was in full possession: or 3. if any damage be done to another, which we had not authority to do to him. Beside which, that a man may be charg'd with Injustice, it is requisite that there be a naughty mind and an evil design in him that acts it. For if there be nothing of these in it, then 'tis only call'd Misfortune or a Fault, and that is so much slighter or more grievous, as the Sloth and Negligence which occasion'd it was greater or less.

LAWS with respect to their Authors XVI. Laws distinguisht. are distinguish'd into Divine and Humane; that proceeds from God, and this from Men, But if Laws be considered, as they have a necessary and universal Congruity [73] with Mankind, they are then distinguisht into Natural and Positive. The former is that which is so agreeable with the rational and sociable Nature of Man, that honest and peaceable Society could not be kept up amongst Mankind without it. Hence it is, that this may be sought out and the knowledge of it acquir'd by the light of that Reason, which is born with every man, and by a consideration of Human Nature in general. The latter is that which takes not its rise from the common condition of Human Nature, but only from the good pleasure of the Legislator; not that this ought to be without its reason, but should carry with it advantage to those men or that Society, for which it is design'd. Now the Law Divine is either Natural or Positive; but all Human Laws, strictly taken, are Positive.

CHAP. III.

Of the Law of Nature.↩

THAT man who has throughly examin'd I. Law Natural obvious. the Nature and Disposition of Mankind, may plainly understand what the Law Natural is, the Necessity thereof, [38] and which are the Precepts it proposes and enjoyns to us Mortals. For as it much conduces to him who would know exactly the Polity of any Community, that he first well understand the condition thereof, and the manners and humours of the Members who constitute it: So to him who has well studied the common Nature and Condition of Men, it will be easie to find by what Laws the universal Safety must be preserv'd.

THIS then Man has in common with II. Self-Preservation. all other Animals, who have a Sense of their own Beings; that he accounts nothing dearer than Himself; that he studies all manner of ways his own Preservation; and that he endeavours to procure to himself such things as seem good for him, and to avoid and keep off those that are mischievous. And this desire of Self-Preservation regularly is so strong, that all our other Appetites and Passions give way to it. So that whensoever an Attempt is made upon the Life of any man, though he escape the danger threatned, yet he usually resents it so, as to retain a Hatred still and a desire of Revenge on the Aggressor.

BUT in one particular Man seems to III. Society absolutely necessary. be set in a worse condition than that of [39] Brutes, that hardly any other Animal comes into the world in so great Weakness; so that 'twould be a kind of miracle, if any man should arrive at a mature Age, without the aid of some body else. For even now after so many helps found out for the Necessities of Human Life; yet a many Years careful Study is requir'd before a man shall be able of himself to get Food and Raiment. Let us suppose a man come to his full strength without any over-sight or instruction from other men; suppose him to have no manner of knowledge but what springs of itself from his own natural wit; and thus to be plac'd in some Solitude destitute of any Help or Society of all Mankind beside. Certainly a more miserable Creature cannot be imagin'd. He is no better than dumb, naked, and has nothing left him but herbs and roots to pluck, and the wild fruits to gather; to quench his thirst at the next Spring, River or Ditch; and, to shelter himself from the injuries of the weather, by creeping into some Cave, or covering himself after any sort with Moss or Grass; to pass away his tedious life in Idleness; to start at every Noise, and be afraid at the sight of any other Animal; in a word, [40] at last to perish either by Hunger or Cold or some wild Beast. It must then follow, that whatsoever Advantages accompany Human Life, are all owing to that mutual help men afford one another. So that next to Divine Providence, there is nothing in the world more beneficial to Mankind than Men themselves.

AND yet, as useful as this Creature IV. Man to Man inclinable to do hurt. is or may be to others of its kind, it has many faults, and is capable of being equally noxious; which renders mutual Society between man and man not a little dangerous, and makes great caution necessary to be used therein, lest Mischief accrew from it instead of Good. In the first place, a stronger Proclivity to injure another is observ'd to be generally in Man, than in any of the Brutes; for they seldom grow outragious, but through Hunger or Lust, both which Appetites are satisfied without much pains; and that done, they are not apt to grow furious or to hurt their Fellow-Creatures without some Provocation. Whereas Man is an Animal always prone to Lust, by which he is much more frequently instigated than seems to be necessary to the Conservation of his Kind. His Stomach also is not only to be satisfied, but to be pleased; [41] and it often desires more than Nature can well digest. As for Raiment, Nature has taken care of the rest of the Creatures that they don't want any: but Men require not only such as will answer their Necessity, but their Pride and Ostentation. Beside these, there are many Passions and Appetites unknown to the Brutes, which yet are to be found in Mankind; as an unreasonable Desire of possessing much more than is necessary, an earnest pursuit after Glory and Preeminence; Envy, Emulation, and Outvyings of Wit. A proof hereof is, that most of the Wars with which Mankind is harrass'd, are raised for causes altogether unknown to the Brutes, Now all these are able to provoke men to hurt one another, and they frequently do so. Hereto may be added the great Arrogance that is in many men, and Desire of insulting over others, which cannot but exasperate even those who are naturally meek enough, and from a care of preserving themselves and their Liberty, excite them to make resistance. Sometimes also Want sets men together by the ears, or because that Store of necessaries which they have at present seems not sufficient either for their Needs or Appetites.

[42]

MOREOVER, Men are more able to V. And very capable. do one another harm than Brutes are. For tho they don't look formidable with Teeth, Claws or Horns, as many of them do; yet the Activity of their Hands renders them very effectual Instruments of Mischief; and then the quickness of their Wit gives them Craft and a Capacity of attempting that by Treachery which cannot be done by open force. So that 'tis very easie for one Man to bring upon another the greatest of all Natural Evils, to wit, Death it self.

BESIDE all this, it is to be considered VI. And likely so to do. that among Men there is a vast diversity of Dispositions, which is not to be found among Brutes; for of them all of the same kind have the like Inclinations, and are led by the same inward motions and appetites: Whereas among Men, there are so many Minds as there are Heads, and every one has his singular opinion; nor are they all acted with simple and uniform Desires, but with such as are manifold and variously mixt together. Nay, one, and the same man shall be often seen to differ from himself, and to desire that at one time which at another he extremely abhorred. Nor is the Variety less discernable, [43] which is now to be found in the almost infinite ways of living, of managing our Studies, our course of Life, and our methods of making use of our Wits. Now, that by occasion hereof Men may not dash against one another, there is need of wise Limitations and careful Management.

SO then Man is an Animal very desirous VII. The Sum of the foregoing Paragraphs. of his own Preservation; of himself liable to many wants; unable to support himself without the help of other of his kind; and yet wonderfully fit in Society to promote a common Good; but then he is malitious, insolent and easily provok'd, and not less prone to do mischief to his fellow than he is capable of effecting it. Whence this must be inferred, that in order to his Preservation, 'tis absolutely necessary, that he be sociable, that is, that he joyn with those of his kind, and that he so behave himself towards them, that they may have no justifiable cause to do him Harm, but rather to promote and secure to him all his Interests.

THE Rules then of this Fellowship, VII. Law Natural defin'd. which are the Laws of Human Society, whereby men are directed how to render themselves useful Members thereof, and [44] without which it falls to pieces, are called the Laws of Nature.

FROM what has been said it appears, IX. The Means design'd where the End is so. that this is a fundamental Law of Nature, That every man ought, as much as in him lies, to preserve and promote Society, that is, the Welfare of Mankind. And, since he that designs the End, cannot but be supposed to design those Means without which the End cannot be obtain'd, it follows that all such Actions as tend generally and are absolutely necessary to the preservation of this Society, are commanded by the Law of Nature; as on the contrary those that disturb and dissolve it are forbidden by the same. All other Precepts are to be accounted only Subsumptions, or Consequences upon this Universal Law, the Evidence whereof is made out by that Natural Light which is engrafted in Mankind.

NOW though these Rules do plainly X. A God and Providence. contain that which is for the general Good; yet that the same may obtain the force of Laws, it must necessarily be presupposed, that there is a God, who governs all things by his Providence, and that He has enjoyned us Mortals, to observe these Dictates of our Reason as Laws, promulg'd [45] by him to us by the powerful Mediation of that Light which is born with us. Otherwise we might perhaps pay some obedience to them in contemplation of their Ʋtility, so as we observe the Directions of Physicians in regard to our Health, but not as Laws, to the Constitution of which a Superior is necessary to be supposed, and that such a one as has actually undertaken the Government of the other.