GUSTAVE DE MOLINARI

Revolutions and Despotism considered from the Perspective of Material Interests (1852)

Gustave de Molinari (1819-1912) |

i |

[Created: 16 March, 2025]

[Updated: 16 March, 2025] |

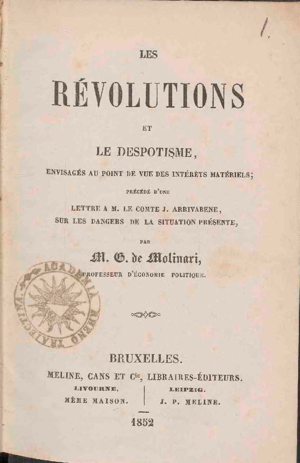

Source

, Les Révolutions et le despotisme envisagés au point de vue des intérêts matériels; précédé d'une lettre à M. le Comte J. Arrivabene, sur les dangers de la situation présente, par M. G. de Molinari, professeur d'économie politique (Brussels: Meline, Cans et Cie, 1852). Deuxième Partie, pp. 81-152. Edited and translated by David M. Hart.http://davidmhart.com/liberty/FrenchClassicalLiberals/Molinari/Books/1852_RevolutionsDespotisme/index-English.html

Gustave de Molinari, Les Révolutions et le despotisme envisagés au point de vue des intérêts matériels; précédé d'une lettre à M. le Comte J. Arrivabene, sur les dangers de la situation présente, par M. G. de Molinari, professeur d'économie politique (Brussels: Meline, Cans et Cie, 1852). Deuxième Partie, pp. 81-152. Edited and translated by David M. Hart.

This title is also available in the original French in facsimile PDF of the original and in enhanced HTML.

This book is part of a collection of works by Gustave de Molinari (1819-1912).

Table of Contents

Second Part: Revolutions and Despotism considered from the Perspective of Material Interests. [1]

[83]

| Les changements brusques ne se font jamais sans une certaine perte de forces vives; d'après ce principe, les révolutions politiques sont toujours funestes, à moins que l'on ne donne aux forces une direction plus utile, en consentant à une partie. | Sudden changes never occur without a certain loss of vital forces; based on this principle, political revolutions are always harmful unless those forces are directed toward a more useful purpose, by consenting to sacrifice a part. |

— QUETELET, Du système social et des lois qui le régissent (On the Social System and the Laws that Govern It)

I

Political economy has two irreconcilable enemies: the spirit of revolution and the spirit of reaction. Do you know why? Because one leads to anarchy and the other to despotism, and from the perspective of the general interests of [84] society, anarchy and despotism are almost equally harmful. That is why, and this is a fact worthy of attention, in times when society has been at the mercy of extreme factions, when the necessary and legitimate guarantees of property or the freedom of citizens have been trampled upon, one would search in vain for an economist among the defenders and flatterers of power. In the 18th century, economists, with the illustrious Turgot at their head, directed all their efforts toward reforming the abuses that feudalism and despotism had accumulated in France. For a brief period, Turgot was a minister, and during that time, he worked to free industry from the old constraints weighing upon it: he abolished guilds and corporations, established freedom in the grain trade, and sought to reform court expenditures. But those who profited from these abuses and were content with them united against Turgot, and the reformist minister was forced to leave power. When I say that Turgot was forced to leave power, I am mistaken. He could have [85] remained in office if he had wished. It would have sufficed for him to silence his convictions and turn a blind eye to abuses. Nothing else was required of him. But Turgot was an intelligent man and an honest man. By studying society, by assessing its needs, by tracing the roots of its ailments, he became convinced of the necessity of reforming the existing regime, and he refused to become an accomplice to that regime. He preferred an honorable retirement to a dishonorable power. A few years later, the French Revolution proved Turgot right. The reforms he had seen as necessary but had wished to implement gradually and peacefully were suddenly imposed by the Revolution with irresistible violence. Very soon, following the sudden movement given to the masses, that had until then had remained in an age-old passivity, the intended goal was exceeded. From constitutional liberty, the country fell into demagogic anarchy. What did the economists do then? [86] They remained what they had been before: liberals. Just as they had sought, in the name of liberty, to reform the abuses of the old regime, they resisted, in the name of liberty once again, the bloody tyranny of the new regime. On the fateful day of August 10, an economist who had played a significant role in the Constituent Assembly, Dupont de Nemours, was at the forefront of the National Guard volunteers who rushed to defend the unfortunate Louis XVI. Outlawed during the Reign of Terror, he owed his survival to the day of 9 Thermidor. A short time later, he was once again pleading the cause of constitutional liberties and was exiled a second time by the Directory. Under the Empire, economists were caught in the same wave of condemnation that Bonaparte directed against the "ideologues"—that is, men who dared to believe that the rule of the sword was not the most perfect of all possible regimes. At that time, the police even prohibited the reprinting of J.-B. Say’s Treatise on Political Economy. Under the Restoration, [87] two economists, Messrs. Comte and Dunoyer, distinguished themselves by their energetic resistance to the ultra-reactionary doctrines of the ghosts who returned from the old regime. Finally, in more recent times, we have seen economists defend liberty against the successors of Robespierre and Babeuf, against the remnants of 1795, just as they had defended it under the Restoration against the remnants of the émigrés. And if the misfortunes of the time were to once again condemn society to languish in the limbo of despotism, the example of Dupont de Nemours, J.-B. Say, Comte, and Dunoyer would undoubtedly find imitators, you may be sure of that.

How is it, then, that not a single economist has ever been found among the trouble-makers of anarchy or among the flatterers of despotism? How is it that all the men who have cultivated economic science over the past century have consistently remained between these two extremes? How is it that none of them has been carried away by the spirit of [88] revolution into demagogy, nor by the spirit of reaction into despotism? What accounts for this?

It is because, in studying the organization of society, in investigating the causes of national prosperity or decline, one inevitably acquires a deep and irresistible conviction: that the two extreme conditions I have just mentioned are almost equally harmful to the well-being and health of the social body.

That revolutions, considered from the perspective of prosperity and progress of societies, are generally disastrous events, veritable catastrophes, can hardly be doubted anymore, I believe. One may debate the causes that lead to revolutions. One may place the blame on one faction or another. One may ask, for example, whether the arrogance, stubbornness, and greed of those who benefited from the old abuses, or the impatient fervor and presumptuous inexperience of the reformers, have [89] contributed more to unleashing the storm. Opinions may differ on this point. But when one observes society caught in this terrible clash of human passions, when one later counts the lives uprooted by the revolution, the interests shattered, the savings squandered, one cannot but recognize that revolution is an evil. One then pities those people who failed to govern themselves wisely, who failed to contain their passions effectively enough to prevent them from colliding like the gusts of wind in a storm. One pities them, but sometimes too, when one has been a victim of their recklessness, when one finds oneself unfortunately caught up in events, compelled to bear an undeserved share of their punishment, one ends up cursing them.

I am aware that this way of judging revolutions does not align with the generally accepted opinion. Our generation, for instance, has been raised to admire and venerate the Revolution of 1789. From childhood, we were trained to repeat, like parrots, [90] those ready made phrases: that the French Revolution emancipated the world; that revolutionary France pioneered progress for the benefit of all peoples; that the armies of the Revolution were the glorious messengers of revolutionary ideas, of revolutionary principles; that they carried liberty, equality, and fraternity on the tips of their bayonets, etc. These are the empty platitudes with which we were nourished and which, in turn, we would have undoubtedly passed on to our children had we not had the unfortunate opportunity to recognize their falsehood. It is not that I wish to deny the utility and grandeur of some of the principles that the French Revolution sought to establish. No! I will not say of the Revolution, as M. de Maistre did, that it was "pure impurity." I admire the generous impulse that gave birth to it; I bow before the noble principles of tolerance and liberty that it proclaimed to the world. But this impulse, these principles—they existed [91] before the Revolution, and I firmly believe that the Revolution compromised them rather than served them. I believe that revolutionary methods—the guillotine at home, bayonets abroad—were tools of barbarism, not vehicles of progress.

The historians who have recounted the events of the French Revolution possessed, for the most part, only incomplete or superficial knowledge of economics. As a result, they have refrained from judging it from an economic perspective. No one has thought to assess the balance sheet of the Revolution. [2] No one has even attempted, even approximately, to determine what it cost and what it yielded.

Allow me to offer you a simple sketch of this horrendous balance sheet. Allow me to cast a brief glance at the liabilities and assets [3] of the Revolution of 1789. This overview will help you understand, better than any other argument, why economists are not revolutionaries.

[92]

In the liabilities of the Revolution of 1789, one must first account for the lives lost to the guillotine and to the revolutionary wars—wars that were a thousand times more murderous than the guillotine itself. One must count the loss of so many men who were torn away from peaceful and productive occupations only to perish under the blade of the guillotine or in the hail of cannon fire on the battlefield. I am aware that human life is often regarded as of little consequence. It is commonly said that the gaps left by proscriptions, war, plague, or any other destructive calamity are soon filled, as if nothing had happened. This reminds me of a phrase, often repeated, attributed to Frederick the Great as he surveyed the battlefield of Rossbach: "One night in Berlin will make up for all this." Well, that phrase was not only inhuman; it was also economically false. A man, in fact, is a kind of capital. When a plague cuts down a man in his prime, all the expenses [93] made in raising this man and getting him ready to take part in production are lost. Undoubtedly, the void is eventually filled, but in the meantime, society is deprived of the services of a educated, trained, and skilled worker, and it must spend additional capital to educate and train a new worker who is able to replace the one who perished. Therefore, when people say that the loss of men due to war costs nothing to society, forgive me for the unrefined comparison, but one that is rigorously accurate—it is as if one were to say that the loss of horses due to glanders costs nothing to agriculture. Do you know how many people perished by violent death as a result of the French Revolution and the wars that were its consequence? Sir Francis d’Ivernois, one of the few writers who studied this regrettable period from an economic perspective, estimated the number at no fewer than two and a half million between 1789 and 1799. And I am [94] convinced that his estimate is quite conservative. It should also be noted that the human massacres which the Revolution sacrificed on the scaffolds and the fields of battle were generally drawn from the most useful classes of society; they consisted of individuals whose intelligence and industry had previously been devoted to production. [4]

The elite of the intelligent and energetic men of the strong generation of 1789 were sacrificed on the guillotine. As for the armies, they ceased to be composed, as before, of the dregs of society—troublemakers and idlers, the refuse of the population. The Revolution could no longer rely solely on these harmful elements, whose violent passions had previously been both indulged and restrained in military service. These troublemakers no longer sufficed. The Revolution invented that terrible machine, conscription, by means of which it reaped men from every class [95] of society. It tore the plowman from his field, the artisan from his workshop, the merchant from his counter, the scholar or the man of letters from his study, to send them all, indiscriminately, to the slaughterhouse of its battlefields.

The men whom conscription delivered by the hundreds of thousands and whom revolutionary generals sacrificed with a prodigality hitherto unknown in the annals of war had a far different value from those who perished in the wars of the old regime. This, in large part, explains the sterility, the absence of talent and vigor in the arts, literature, and industry that is so noticeable after the great revolutionary explosion. The elite of the nation had been decimated, and the new generations had not been able to develop for productive work amidst the turmoil and disasters of civil and foreign wars.

But the loss that the Revolution inflicted on society was not limited to the destruction of useful men. Not only were these men [96] removed from productive employment; they ceased contributing to the creation of wealth and the advancement of civilization. Moreover, they were supported at the expense of the producers and were, for the most part, employed in the destruction of wealth.

The Revolution destroyed men in two ways: by the hand of the executioner and by the sword of battle.

And these two methods of destruction were almost equally costly. Certainly, revolutionary terrorism did not go to great expense to support its victims. Besides, it did not keep them for long. But what was horrendously expensive was the apparatus used to arrest and execute them—the multitude of informers, jailers, judges, and executioners who had to be fed and bribed to keep the hideous machinery of the Terror in motion. At the same time, vast armies had to be supported to meet the ever-growing demands of civil [97] and foreign wars. How did the Revolution manage to cover such enormous expenses? It invented assignats, it carried out confiscations, requisitions, and war taxes on an immense scale, and it made bankruptcy the order of the day. In ten years, it issued 45 billion assignats. This was, of course, a nominal value, since this flood of paper money never represented more than one and a half to two billion in real value. But it was nonetheless a forced loan, levied in the most disastrous of forms, and one that was never repaid. As for confiscations, requisitions, and war taxes, it would be impossible to estimate their total amount even approximately. Nothing escaped confiscation and requisition. Once a poor farmer had his sons taken away to serve in the army, his horse and cart were seized for military transport, his livestock was taken to feed [98] the troops, and even the blade of his plow was melted down to forge weapons of war.

To feed the armies or the cities, the wheat that he had stored in his granaries was requisitioned and was paid for in depreciated assignats at a fixed maximum price. If he dared to resist such extortionate demands, he was branded an aristocrat or a hoarder and sent to the guillotine. And even if the requisitioned food and goods had reached their intended destination, that would have been something! But most of the time, they remained stored in the storehouses of the Republic, where weevils and corrupt officials reaped the profits.

For the armies were lacking in everything and survived through looting. When, unable to feed them from domestic supplies, they were unleashed upon Europe, they lived off war taxes. People forget quickly, and the memory of the war levies of the first Revolution is beginning to fade. Yet it [99] was a significant and instructive chapter in our story! Certain countries had prospered during the relatively long period of peace before the Revolution—Belgium and Italy, for example. The Revolution took it upon itself to strip them bare. Its generals and proconsuls were highly skilled at this task. Danton took charge of Belgium, and Danton never did things by halves. Being a bit stout was no longer a problem for us after the visit of Danton and the patriots of ’92.

In Italy, as in Belgium, the revolutionaries arrived as liberators, yet the city of Milan alone was subjected to a single war tax of twenty million. Until the great disasters of the Empire, war taxes and fines imposed on the conquered people—what were then called external revenues—were largely sufficient to support the French armies. And note well that these people not only had to support the armies of the Revolution but also [100] the armies that fought against them. They were bled dry both to secure the Revolution’s triumph and to resist it. In twenty years, England spent approximately twenty billion to hold back the Revolution, and Austria, Prussia, Russia, and Spain supported this effort as much as their strength and resources allowed.

That is not all. Not only were the immense armies raised and set against each other across Europe by the Revolution, not only were these armies, composed of so many millions of strong arms, lost to production, not only did they absorb billions in the form of taxes, loans, requisitions, and war taxes, but they were also used to destroy, by fire and sword, the means of subsistence of the populations.

Before the Revolution, respect for private property during war had gradually become a rule of the law of nations. When a power failed to observe this protective rule, [5] [101] the opinion of the civilized world rigorously condemned its conduct. Thus, the burning of the Palatinate was criticised as a crime to Louis XIV. This respect for property during war was something the Revolution never knew. Internally, confiscation and destruction of property were its usual methods. After two years of civil war, the Vendée was nothing more than a horrifying heap of ruins. About 900,000 individuals—men, women, children, and the elderly—had perished, and the few who survived the massacre could barely find enough to eat or shelter themselves. The fields were devastated, the enclosures destroyed, the houses burned. A former administrator of the Republican armies, who left behind curious memoirs about this war of extermination, described the spectacle he encountered during one of his inspections as follows:

"I did not see," he said, "a single man in the parishes of Saint-Harmand, Chantonnay, and Les Herbiers. Only a few women [102] had escaped the sword. Country houses, cottages, any kind of habitation—everything was burned. The herds wandered as if struck with terror around their smoking sheds. Night fell upon me, but the flames of the fire illuminated the entire countryside. The lowing and bleating of the cattle were joined by the hoarse cries of birds of prey and carnivorous animals, which, from the depths of the woods, rushed toward the corpses. Finally, a column of fire, which I saw growing as I approached, served as my beacon. It was the burning of the town of Mortagne. When I arrived, I found no other living beings than wretched women, who were trying to save a few belongings from the general blaze."

Such was the civil war. Such was the Revolution. And this system of destruction was not used solely in the civil wars of the Revolution. Later, it extended to foreign wars. In Spain, the invaders used it to terrify the populations they [103] sought to subjugate; in Russia, the people, threatened in their independence, used it to starve the invaders. Everywhere, ruins were piled upon ruins, and the European continent became nothing more than a vast field of desolation and carnage.

Thus, between two and three million men sacrificed in civil conflicts or foreign wars; at least twenty to thirty billion taken in the form of taxes, loans, confiscations, requisitions, and war taxes to cover the costs of this gigantic slaughter of men, not to mention the capital consumed or destroyed by fire, the sword, and looting, nor yet the capital consumed in idleness as a result of the revolutionary crisis—this, from the sole perspective of material interests, is the liabilities of the French Revolution.

Now, let us examine its assets.

The Revolution abolished guilds and trade corporations in France, eliminated internal customs duties [104] and old feudal servitudes, and put into economic circulation the properties of the nobility and the clergy. These are the main items in its assets. The defenders of the Revolution have the habit of loudly proclaiming these achievements, but upon closer examination, one realizes that much must be deducted from the praise they bestow upon them. When one studies the old regime as it existed in 1789, one sees that its old machines of servitude had been significantly weakened, rusted by the action of time; one also sees that each day, new ideas, new discoveries, and new needs arose like real engines of war to reduce to dust the obstacles that this regime still posed to the development of wealth and the expansion of civilization.

Turgot had already made a first attempt to abolish guilds and trade corporations as well as internal customs duties. This attempt had failed. But such were the necessities of the time [105] that a second attempt would inevitably have succeeded a little later. Moreover, what were the final consequences of the Revolution regarding the freedom of labor and commerce? These consequences were disastrous: the Revolution was fatal to the freedom of transactions, as it was to many other liberties, for it either engendered or at least reinforced and universalized the protectionist system. [6]

Before the Revolution, the school of Quesnay and Turgot in France, as well as that of Adam Smith in England, had successfully advocated for the cause of commercial freedom, and a treaty based on the new economic doctrine had been concluded in 1786 between France and England. But then the Revolution occurred, and immediately the liberal treaty of 1786 was replaced by prohibitive measures of an unprecedented severity. In one of its feverish decrees, the Convention had ordered its armies to take no more English prisoners, which was nothing less than a return to the customs of primitive barbarism. Well, this system of ruthless [106] destruction was not limited by the Convention to England’s soldiers; it was also applied to its goods.

English merchandise was prohibited, and whenever it was seized, it was burned in public squares. Napoleon continued this barbaric system, even expanding it to colossal proportions and imposing it on all the allied nations of France. Under the Continental Blockade, the greater part of the continent was closed to English goods, and the public burnings of these proscribed wares multiplied in town squares. (b) [7]

Finally, after the fall of the Empire, English industry, which had been spared from confiscations, requisitions, paper money, pillaging, and fire, was so far superior to that of the regions of Western Europe where the Revolution had spread its ravages that governments everywhere were forced—by the [107] outcries of landowners and industrialists—to maintain the prohibitive régime that the Revolution had inaugurated. I am personally convinced that the French Revolution delayed the advent of commercial freedom by at least a century, and in my opinion, this is by no means one of the least grievances that can be raised against it in the name of civilization.

As for the reform of taxation under the old regime, it was a mere masquerade. At first, the old taxes were indeed abolished, but since the revolutionary government had not thought to reduce public expenditures, it was necessary to fill the void left by the abolition of these former taxes. This void was initially filled by paper money, confiscations, and requisitions; but these revolutionary resources came to an end, and one day, the public treasury found itself completely empty. What was done then? The abolished taxes were simply reinstated. Only their [108] names were changed to avoid alarming taxpayers too much. Thus, the taille and the vingtièmes were renamed the land tax (contribution foncière); the tax on guilds and trade corporations (*la taxe des maîtrises et jurandes), as well as the gold-mark duty (le droit de marc d'or) that had to be paid to engage in commerce or an industrial profession, were replaced by the licensing tax (les patentes); the control duty (le droit de contrôle) became known as the stamp duty (le droit de timbre); the aides were renamed indirect contributions (contributions indirectes) or unified duties (droits réunis); the hated gabelle was given the innocuous name of salt tax (impôt du sel); the octrois were initially abolished but were soon reinstated under the philanthropic designation of charitable octrois (octrois de bienfaisance); the corvées were abolished, but peasants were subjected to mandatory labor contributions in kind. In short, the entire old tax system reappeared, merely baptized under some new names.

Regarding the feudal rights sacrificed on the famous night of August 4th, they had already lost nearly all their importance due to successive buyouts. Had they [109] still retained any real value, rest assured they would not have been relinquished so lightly! As for the confiscation and division of the lands belonging to the nobility and the clergy, this is an operation whose benefits are widely contested today, even from a purely economic standpoint. The proceeds from the sale of these properties (estimated by the former minister Ramel at about 2.5 billion francs) were quickly swallowed up by the wars of the Revolution, and later, the country had to go into debt to compensate the émigrés; it also had to provide salaries to the clergy to make amends for the unjust plunder to which they had fallen victim. What, then, was the actual benefit of this operation?

Moreover, note that the old regime, which the Revolution overturned in France, survived in England. The English did not set out to wipe away their ancient institutions; they merely reformed them when they deemed it useful. Well, compare the growth of [110] public wealth in England over the past half-century to that in France; compare as well, if you wish, the civil and political liberties acquired by the two nations in the same period, and then judge for yourself the value of the two systems!

From the perspective of material interests, the assets of the French Revolution are not substantial. If one were to consider this same Revolution from the perspective of morality —if one examined the influence that paper money, confiscations, war, despotism, and the other scourges it produced had on the morality of the people—oh! then the deficit would rise far higher, and the loss would seem irreparable. It is often claimed that the French Revolution sowed the world with admirable seeds of liberty, equality, and fraternity, and one hears again and again the grandiose phrase about ideas carried on the tips of bayonets. But does it not seem that these so-called seeds of liberty, equality, and [111] fraternity that the Revolution spread across the world have taken a very long time to bear fruit, even in France? And does it not also seem that revolutionary bayonets made rather poor supports for liberal and progressive ideas?

I am personally convinced that the Revolution, with its funeral procession of civil struggles and wars of invasion, was disastrous for the spread of French ideas, far from serving their cause. In the eighteenth century, France was the great intellectual center of Europe. Its reform-minded Philosophes were listened to as oracles. The Poles sought constitutions from Mably and Rousseau; a French economist, Mercier de la Rivière, was invited to Russia to give his opinion on the legislative changes to be introduced in the empire. Finally, Voltaire, the great apostle of the spirit of tolerance and liberty—Voltaire was the idol of Europe, and the reading of his books were both the recreation of sovereigns and the hope of the people.

And now, what people today [112] would think to request constitutions from France? What nation would concern itself with experimenting with French ideas? People avoid them as they would the plague, and they indiscriminately reject both the good and the bad in the same universal condemnation. Before the Revolution, all liberal minds, all progressive intellects, all hearts that beat with love for humanity, turned their eyes toward France. Today, they turn away, and it is toward England that their wishes and hopes are directed. England has become the support and the hope of liberty in Europe.

Thus, when one balances the account of the French Revolution—when one considers, on the one hand, the immense devastation it caused, the sacrifices of human lives and capital it demanded of the world; and when, on the other hand, one examines the acquisitions it yielded, almost all of them illusory or precarious; when one weighs its assets against its liabilities—one realizes, beyond a shadow of a doubt, that the affair was bad for France, and bad for humanity.

[113]

If the same methods of economic analysis are applied to the Revolution of 1848, if one balances the account of the February Revolution, it will be even easier to see that the affair was a bad one. On the liabilities side, we must first account for the increase in military expenditures that this revolution occasioned across Europe, the costs of the internal wars that broke out in France, Italy, and Germany, not to mention potential future consequences. War, after all, is the only industry that has not become cheaper in modern times. To cite just one example, the cost of suppressing the June insurrection alone is estimated at over 70 million. And yet, this painful chapter of the Revolution’s direct expenses is insignificant compared to the losses and indirect costs it caused.

From February 24, 1848, European industry suffered a terrifying depression caused by the revolutionary crisis, and its losses must not be counted [114] in millions but in billions. A survey conducted under the supervision of the Chamber of Commerce, directed by Horace Say—a worthy heir to his illustrious father—states that industrial production in Paris, which amounted to 1,463 million in 1847, fell to 677 million in 1848. This represents a loss of more than 700 million in a single year and in a single city. From this, one can estimate what France lost, what Italy, Austria, and Germany lost. Even nations that had the wisdom to shield themselves from the revolutionary contagion felt the aftershocks of the crisis. For instance, Belgium’s foreign trade, which in 1847 totaled 732 million in imports and exports, fell to 631 million in 1848. Finally, England—so unjustly accused of sowing disorder in Europe to expand its production at the expense of its rivals—saw its exports drop from 78 million pounds sterling in 1847 to 71 million [115] in 1848. In short, it was a universal disaster. This is the liabilities side of the February Revolution. As for its assets, you already know what additional liberties this disastrous revolution granted to the world, and perhaps the account is not yet fully settled. Its assets are not even zero; they are negative. It was a political bankruptcy, perhaps unparalleled in history.

Now you should understand why economists are not supporters of revolutions—why, after 24 February, 1848, just as after 10 August, 1792, they struggled against the revolutionary spirit. It is because economists do not content themselves with empty phrases and meaningless formulas; they get to the heart of the matter; they take the trouble to balance the accounts of revolutions—something that the enthusiastic minds who push the cart of revolution forward rarely think to do, and who, in the end, are invariably crushed when the wheel rolls back against them. For [116] revolutions do not withstand the test of double-entry bookkeeping; [8] revolutions are huge eaters, [9] reckless spenders who devour in a few days the savings accumulated over centuries. And since, more often than not, all they have to offer the people in exchange for their savings and the lives of their children are nothing but inflammatory speeches and unhealthy utopias, economists—who are the bookkeepers of politics—have sounded the alarm against revolutions and declared an unrelenting war [10] on revolutionaries.

II

It remains for me now to explain why political economy is hostile to despotism—why economists have no more fondness for despots than they do for revolutionaries.

What is the purpose of a government? What is its principal function in society? A government, as you know, has as its primary function the guarantee of public security. Security is an essential commodity for society. When it is lacking, when the lives and property of citizens cease to be adequately protected, production and savings [118] slow down, and society regresses toward barbarism.

Now, from the perspective of the security necessary for all interests, which is preferable in the current state of civilization—a representative government or a despotic government? Which of these two forms of government offers civilized nations the best guarantees of security? This is what must be examined.

For some time now, despotism has been much praised. Despotism is in fashion. It is extolled as having infallible virtues for repairing the damage caused by anarchy, for stabilizing a society shaken to its foundations, and so on. This has become the standard rhetoric.

And, sadly, this rhetoric has found as much success among a certain backward, ignorant, and shortsighted portion of the upper classes as revolutionary rhetoric once did among a certain backward, ignorant, and shortsighted portion of the lower classes. Despotism now [119] makes converts among the educated classes, just as socialism did some time ago among the uneducated classes. [11] This is understandable, for despotism and socialism ultimately rely on the same passions and exploit the same illusions. Why did the lower classes throw themselves into the arms of socialism? Because they had been led to believe that socialism had a miraculous recipe for improving their social condition; because they were convinced that socialism had the power to make them wealthy overnight. Why does despotism now find panegyrists among the educated classes? Because it is attributed with the miraculous property of being able to safeguard the interests that the Revolution has threatened; because it is believed to be a vehicle for the preservation of an in irresistible force.

The illusions of the classes that placed their faith in socialism—these illusions have been cruelly shattered. A no less [120] cruel disappointment awaits those men who are shortsighted, blind, and reckless enough to entrust their lives and fortunes to despotism.

If we wish to convince ourselves of this, let us examine the security guarantees provided by the parliamentary system on the one hand, and despotism on the other, and compare them.

In countries that still enjoy the benefits of the parliamentary system, such as England and Belgium, upon what does the government rest?It rests directly upon an electorate drawn from the upper layers of the nation [12] —an electorate that possesses the greater part of the productive capital of the country and that also comprises, if not the majority of the nation's intelligence, then at least the majority of its knowledge.

This electorate, composed of landowners, industrialists, large and small merchants, and members of the liberal professions—this electorate, which includes most [121] of the capitalists who provide the essential elements of production and the intelligent, industrious, and diligent men who direct it—this electorate appoints representatives charged with providing the government with the resources it needs and overseeing its actions. Nothing can be done without their approval, for they hold the purse strings of the nation. What this electorate, represented by its delegates, desires, the government must carry out, under penalty not only of becoming unpopular and odious but of endangering its very existence.

The will of the electorate—this is the supreme regulator of a representative government. Expressed through the national representation, this will is enlightened and reinforced by the press.

The press is, no less than Parliament itself, an essential element of the representative system. Considered even from the simple perspective of material interests, you will see what an admirable role it plays and what a protective function it fulfills.

[122]

There have often been complaints that the press misleads or tyrannizes public opinion. These complaints may have some merit in a country where the press is monopolized, where political and fiscal barriers make it difficult, if not impossible, to increase the number of newspapers. But when the press is entirely free, as it is—thank heaven!—in Belgium, [13] the press appears only as a tool through which the opinion of a country is formulated and expressed in all its thousands of nuances, and through which this opinion can also be measured, weighed, and evaluated with almost mathematical precision.

At first glance, I admit that the press has something rather unsettling about it. It is an outrageously noisy machine, whose movements appear chaotic and anarchic. One is bewildered and alarmed by it. The surprise and alarm only increase when one [123] considers into whose hands this formidable lever may fall. For the press is an industry in which anyone can engage. No guarantee of knowledge or morality is required of a journalist; access to the press is denied neither to the ignorant nor even to those disgraced by justice or condemned by public opinion.

This, one might say, is a regrettable mess and a terrible danger. How can society survive, exposed daily to the provocations of a class of men who offer it no guarantees? Is this not an intolerable situation? However, if one takes the trouble to examine more closely the mechanisms of the press, the danger disappears. One then perceives a hidden power, of which the press is merely an tool, and which directs or regulates all its movements. I am speaking of public opinion and the interests of the classes to which newspapers are addressed.

Certainly, those who hold the lever of the press in their hands are [124] free to use it as they wish, just as cloth manufacturers are free to produce coarse or fine cloth and to dye it red, yellow, blue, or green according to their preference. A journalist is free to give his newspaper whatever color he pleases—the color red, for example—just as a manufacturer is free to dye his fabric scarlet or canary yellow. In this respect, society appears to have no influence over either, at least in appearance. I say "in appearance" because, in reality, society can be perfectly certain that it will never be forced to read only red newspapers or to wear only scarlet or canary-yellow clothing. And do you know why this certainty is absolute in both cases? Because both journalists and cloth manufacturers are compelled to cater not to their own preferences but to those of their customers; because the freedom of the press forces the journalist to conform to the opinions of his readership, just as [125] the freedom of industry forces the manufacturer to conform to the tastes of his consumers.

Suppose that two or three major manufacturers in Verviers decide to dye all their fabrics scarlet or canary yellow. Would their customers not immediately turn away from them? And thanks to industrial freedom, would these customers, whose modest and subdued tastes had been recklessly ignored, not easily find enough black, blue, green, or brown cloth elsewhere to dress themselves? Suppose, likewise, that our monarchist and constitutional newspapers suddenly decide to preach the doctrines of radical republicanism—to glorify Robespierre, Marat, and Babeuf. Would their bewildered and offended readership not immediately abandon them en masse in search of alternatives? And, since we enjoy freedom of the press, would not new newspapers spring up overnight to welcome this loyal monarchist and constitutional readership?

The press, at least in countries where [126] governments have not committed the folly of restricting its development and limiting its freedom, is compelled to conform precisely and scrupulously to public opinion. Under the penalty of losing their readers and subscribers—in other words, under the penalty of death—newspapers must tailor their language to the sentiments of their audience. Journalists are far less the governors or directors of opinion than its heralds or trumpets.

In free countries, every shade of opinion finds expression and representation in the press, and each is reflected precisely in proportion to its importance. The most widespread views are those with the most newspapers or the largest readerships and subscriber bases. Thus, merely by tallying the newspapers and their audiences, one can ascertain, with almost mathematical accuracy, the state of public opinion. In free countries, the press is nothing other than a veritable"gauge of opinion." [14]

[127]

What is the consequence of this? It is that, in free countries, governments never proceed blindly; they are never at risk of crashing against hidden obstacles—unless they deliberately shut their eyes to the light. They can monitor the state of public sentiment daily, and by aligning themselves with the dominant opinion, they ensure their stability and resilience.

No doubt, public opinion can go astray. But when one closely examines the interests that opinion represents—that it is the direct expression of—it becomes evident that its missteps cannot be truly dangerous. Suppose, for example, that public opinion takes a false and harmful direction, and the government follows along that path; soon enough, the nation’s interests will begin to suffer. Immediately, public opinion will shift under the irresistible pressure of these interests; the language of the press, on one side, and the electoral choices of the electorate, on the other, will adjust accordingly, and the direction of government will be corrected.

Thus, for instance, the representative [128] system has preserved world peace for over thirty years with hardly any interruption. Peace has become the normal state of society—whereas it once appeared exceptional and transient, a rare phenomenon even as it was universally desired. Why has this beneficial transformation occurred? Why has the reign of peace succeeded that of war? Because the industrious and enlightened classes that make up the electorate and the readership of newspapers—these leading classes in representative countries—understand what war costs and what it yields. Because they have no interest in embarking on ventures they know to be ruinous for themselves and for their nations. And since the will of these industrious and intelligent classes is the supreme regulator of representative governments, these governments today avoid war as carefully as those of the past sought to provoke and perpetuate it.

[129]

III

Now, suppose that the parliamentary tribune [15] is dismantled and the press is gagged—suppose that despotism replaces the representative system—and observe what follows. This great class of property owners, capitalists, industrialists, and merchants, whose opinions, expressed through the tribune and the press, were once sovereign—this great class, so deeply invested in social preservation—suddenly finds itself deprived of all power and influence. It is no longer the base on which society rests; it is no longer [130] consulted. It no longer counts; it no longer exists.

How, indeed, could it retain any political influence? Has the despot not destroyed or corrupted the very tools through which the voice of this intelligent and free class could be made public? Has he not silenced the so-called ideologues and chatterers? Has he not commanded that silence be maintained around him?

From then on, it is the Administration that is tasked with declaring what the country thinks and wants. It is the Administration that is responsible for informing the sovereign about the state of public opinion. But can one expect this assessment of opinion, conducted through bureaucratic means, to always be truthful? Can one further expect that the interests of the industrious and enlightened classes will find a faithful advocate in the Administration? This deserves closer examination.

Under a despotic regime, opposition to the will of the sovereign is a thing so unheard of, so excessive, so contrary to all notions of common sense that, in [131] the monarchies of the good old days, only one person had the privilege of speaking unpleasant truths to the ruler: the court jester. And it does not seem that this particular kind of folly was ever contagious This is easily understood. Is not the despot the supreme dispenser of favors, honors, and wealth? Since he draws freely from the nation’s treasury, is his favor not an inexhaustible Pactolus? Can he not, with a single word, lavish riches upon his favorites? And what, then, is the surest way to obtain this golden favor? Is it not to flatter the tastes and inclinations of the master and to say “Amen” to all his wishes? For human nature is such that—whether a person is at the highest peak or the lowest rung of the social ladder, on the throne or in the gutter—he loves those who approve of him and detests those who criticize him. This is simply his nature Throughout history, as humanity has endured the harsh experience of despotism, how many examples could be cited of rewards granted to those who opposed the [132] views of a sovereign and criticized his actions? In contrast, are not the favors heaped upon the detestable rabble of flatterers more numerous than the sands of the sea? It is therefore entirely understandable that opposition is rare under a despotic regime: nowhere else is opposition so fruitless or so ruinous, and nowhere else is flattery so profitable.

When a despotic sovereign expresses his will, no one debates it—they obey. And if, by chance, he wishes to consult the opinion of the nation, how do his trusted advisors satisfy this desire? Is it not always by ensuring that the nation has no opinion other than that of the sovereign? If they naïvely allowed the country to speak as it truly thinks, would they not risk jeopardizing their own positions? Would they not be held responsible for what would inevitably be called the "excesses of public opinion"? Such is the inherent flaw of despotism: under this system, the true opinion [133] of the country can never be made known to the sovereign.

This is not the case, as everyone knows, under a representative system. Certainly, even under this system, there is still a monarch naturally inclined to follow his own instincts and impose his will; there are still administrators, both high and low, who are equally inclined to flatter the monarch’s preferences and passively execute his wishes whenever it benefits them Unfortunately for them, however, the situation is no longer the same: the monarch is no longer the supreme dispenser of honors and wealth, nor the inexhaustible fountain of favors, for the so-called ideologues and chatterers have strictly limited his authority and his finances—they have placed a tap on the fountain. If the monarch wishes to display his munificence, it is no longer at the nation’s expense, but at his own. Under this new order, the profession of courtier becomes almost unprofitable, and since this profession, after all, has little inherent appeal, [134] people quickly tire of it. Flattering princes is no longer as lucrative because it is no longer as profitable. It is a lost industry On the other hand, the prince no longer needs to rely on his administration to know what the nation thinks and wants; there is a tribune and a press that undertake to inform him.

Under a despotic regime, the administration, by the very nature of the system, is driven to sacrifice the country’s opinion to the sovereign’s inclinations. Worse still, its immediate interests push it to advise the sovereign to act against the best interests of the nation.

What, after all, are administrators? They are tax eaters. [16] They live off the taxes levied upon the nation. What, then, is in their immediate interest? It is to have ample taxes to eat; it is to manage a large budget. The more burdened the taxpayers are with taxes, the more the administration flourishes. It was an administrator who coined the now-famous maxim: "a tax is the best investment." [135] For the administration, certainly! Doesn't every public enterprise—whether it is burdensome or productive for the nation—inevitably benefit the administration? If the enterprise fails, what does it matter to the administrators? Have they not, in the meantime, managed the expenditures? And even when a nation suffers industrial and commercial setbacks due to its government’s misguided speculations, do administrative salaries ever decrease? If, on the other hand, the enterprise succeeds, does the administration not reap the clearest profit? Is it not a new market which has been permanently opened for its industry? [17]

How, then, could the administration be a truthful organ of public opinion? How could the tax eaters be faithful defenders of the tax payers?

To the influence of the administration is added the influence of the military in directing the primitive and crude machinery of despotism, and the latter is even worse than the former. For if [136] the administration pushes for more spending, the army pushes for more war—that is, the most burdensome of all expenditures. Is not war the source of glory, fortune, and honors for the army? Do military campaigns not count double in service records? How, then, could the army not push for war?

Those guarantees of sound economy and peace, which a nation possesses in the highest degree when it holds its own purse strings—when all enterprise, including all the expenses of government, are subjected to the free discussions of the press and the votes of the representatives of the "payers of taxes" —what becomes of these precious guarantees under a regime where the influence of the "eaters of taxes" in the administration and the army remains unchallenged? [18]

I am well aware that despotism claims it is under no obligation to any influence and to always follow its own impulses. But I know of no claim [137] less justified than this one. It has long been said that if the despot is a tyrant, he is also a slave. In Rome, the emperor was at the mercy of his praetorians; in Constantinople, the sultan was at the mercy of his janissaries. When the janissaries were displeased, they overturned their cooking pots, and the sultan trembled in his palace.

Whether he wills it or not, the despot is subject to the influence of the organized bodies on which he must rely to govern his people and maintain obedience. Emperor Napoleon I was certainly the most absolute despot the world has ever seen, yet without realizing it, he acted largely according to the combined impulses of his administration and his army. Do I need to add that they constantly pushed him toward war, even when the nation most ardently desired peace Thus, for example, when rumors of the Russian expedition began to circulate, public opinion was universally opposed to this mad enterprise. And yet, curiously enough! [138] from all corners, the established bodies sent addresses of congratulations to the emperor in the name of the nation. This was because the administrators, eager to flatter their master’s inclinations and interested in expanding their foreign markets, had reinterpreted public opinion in their own way. As for the army, it was, as always, filled with enthusiasm. The Russian campaign—was it not, for them, another harvest of laurels to be gathered? A harvest of laurels, which, in plain language, meant promotions, pensions, decorations, and pilfering Only one man dared to serve as the voice of public opinion on this occasion—former Minister of Police Fouché. Fouché sent the emperor a memorandum in which he expressed the true sentiments of the public regarding the proposed expedition. Napoleon I summoned the author of this impertinent memorandum and "gave him a good dressing down", [19] to use one of his own familiar expressions, demanding to know why he was interfering in matters that did not concern him:

[139]

"I have eight hundred thousand men," he said, "and for someone who possesses such an army, Europe is nothing but an old prostitute who must obey his will. Did you yourself not tell me that 'impossible' is not a French word? I shape my policies more according to the opinion of my armies than according to the sentiments of your grandees, who have grown too rich and who, while pretending to be anxious for my well-being, truly fear nothing but the general confusion that would follow my death. Do not trouble yourself; rather, consider the Russian war as a wise measure dictated by the true interests of France and the general stability of Europe. Am I to be blamed if the high degree of power I have already attained forces me to assume the dictatorship of the world? My destiny is not yet fulfilled; my current position is merely the rough sketch of a painting that I must complete," and so on, and so on.

The author of the memorandum attempted to defend his work. The master refused to listen, and Fouché fell completely into disgrace. A fine warning to those who might have wished to raise the firm voice of truth amidst the insipid chorus of administrative sycophants!

[140]

The following year, after the dreadful disasters of the Russian campaign, public opinion in France expressed itself even more forcefully in favor of peace. But once again, the administration intercepted and distorted it. After passing through the distillation apparatus of the bureaucracy, the nation's unanimous call for peace was suddenly transformed into support for the continuation of the war. In his Life of Napoleon, a work that, incidentally, has not been given the recognition it deserves, Sir Walter Scott insightfully observes how the destruction of all free organs of thought in the country proved disastrous not only for France but for the emperor himself: [20]

[141-142]

One of Buonaparte's most impolitic as well as unjustifiable measures had been, his total destruction of every mode by which the public opinion of the people of France could be manifested. His system of despotism, which had left no manner of expression whatever, either by public meetings, by means of the press, or through the representative bodies, by which the national sentiments on public affairs could be made known, became now a serious evil. The manifestation of public opinion was miserably supplied by the voices of hired functionaries, who, like artificial fountains, merely returned back with various flourishes the sentiments with which they had been supplied from the common reservoir at Paris. Had free agents of any kind been permitted to report upon the state of the public mind, Napoleon would have had before him a picture which would have quickly summoned him back to France. He would have heard that the nation, blind to the evils of war while dazzled with victory and military glory, had become acutely sensible of them so soon as these evils became associated with defeats, and the occasion of new draughts on the population of France. He would have learned that the fatal retreat of Moscow, and this precarious campaign of Saxony, had awakened parties and interests which had long been dormant-that the name of the Bourbons was again mentioned in the west that 50,000 recusant conscripts were wandering through France, forming themselves into bands, and ready to join any standard which was raised against the imperial authority; and that, in the Legislative Body, as well as the Senate, there was already organized a tacit opposition to his government, that wanted but a moment of weakness to show itself.

Moreover, and this is worth noting, the capitalists, industrialists, and merchants who had initially acclaimed the imperial regime gradually lost confidence in it. At first, they had embraced it enthusiastically, seeing it as a reliable guarantee against the return of anarchy. Their enthusiasm was further heightened by the solemn assurances of peace with which Bonaparte had skillfully inaugurated his sovereign rule (see Part One, p. 27). The confidence that had vanished in the revolutionary turmoil was revived as if by magic under the Consulate. At that time, all sectors of national activity experienced a remarkable revival, and a tremendous impulse was given to [143] every enterprise. Unfortunately, the harmful influence of the war interests that dominated the imperial constitution soon turned this prosperity into economic distress. The industrious and capitalist classes, left without serious representation or free institutions, and with only the civil and military governing bodies holding power, saw the promises of peace vanish like smoke, while Europe once again became a bloody battlefield. As experience made it increasingly clear to the industrious and capitalist classes that they lacked the necessary political institutions to assert their peace interests over the war interests of the administration and the army, [21] their confidence in the imperial regime steadily declined. Their illusions seem to have lasted until 1807, but from that time onward, even as the imperial establishment continued to consolidate and expand to colossal proportions, trust in it gradually eroded, and financial markets steadily [144] declined. [22] The reason was clear: those interest ed in peace had definitively realized that the imperial regime, by the very nature of its despotism, could not [145] provide them with the security they needed Finally, when the empire collapsed under the weight of a coalition of European powers, the consequences were well known. Those interested in peace were reassured, and financial markets rose across Europe—even in France. From the perspective of those interests, this great battle that brought an end to imperial despotism, by establishing the constitutional system on its ruins—this great battle that inaugurated and ensured general peace—was perhaps the best transaction the nations had ever made, for it eliminated a source of turmoil and insecurity that had hindered production and savings throughout the world.

Had Bonaparte granted a legitimate share of influence to the classes interested in peace within his constitution, instead of gagging public opinion with the hilt of his sword and relying solely on the war interests, would the fate of the nation—and his own—have not been vastly different? Allow me to cite, in this regard, another passage from [146] The Life ofNapoleon, a passage marked by both remarkable common sense and, unfortunately, prophetic wisdom: [23]

[147-48]

But, though we may acknowledge many excuses for the ambition which induced Buonaparte to assume the principal share of the new government, and although we were even to allow to his admirers that he became first consul purely because his doing so was necessary to the welfare of France, our candour can carry us no farther. We cannot for an instant sanction the monstrous accumulation of authority which engrossed into his own hands all the powers of the state, and deprived the French people, from that period, of the least pretence to liberty, or power of protecting themselves from tyranny. It is in vain to urge, that they had not yet learned to make a proper use of the invaluable privileges of which he deprived them equally in vain to say, that they consented to resign what it was not in their power to defend. It is a poor apology for theft, that the person plundered knew not the value of the gem taken from him; a worse excuse for robbery, that the party robbed was disarmed and prostrate, and submitted without resistance, where to resist would have been to die. In choosing to be the head of a well-regulated and limited monarchy, Buonaparte would have consulted even his own interest better, than by preferring, as he did, to become the sole animating spirit of a monstrous despotism. The communication of common privileges, while they united discordant factions, would have fixed the attention of all on the head of the government, as their mutual benefactor. The constitutional rights which he had reserved for the crown would have been respected, when it was remembered that the freedom of the people had been put in a rational form, and its privileges rendered available by his liberality.

Such checks upon his power would have been as beneficial to himself as to his subjects. If, in the course of his reign, he had met constitutional opposition to the then immense projects of conquest, which cost so much blood and devastation, to that opposition he would have been as much indebted, as a person subject to fits of lunacy is to the bonds by which, when under the influence of his malady, he is restrained from doing mischief. Buonaparte's active spirit, withheld from warlike pursuits, would have been exercised by the internal improvement of his kingdom. The mode in which he used his power would have gilded over, as in many other cases, the imperfect nature of his title, and if he was not, in every sense, the legitimate heir of the monarchy, he might have been one of the most meritorious princes that ever ascended the throne. Had he permitted the existence of a power expressive of the national opinion to exist, co-equal with and restrictive of his own, there would have been no occupation of Spain, no war with Russia, no imperial decrees against British commerce. The people who first felt the pressure of these violent and ruinous measures, would have declined to submit to them in the outset. The ultimate consequence-the overthrow, namely, of Napoleon himself, would not have taken place, and he might, for aught we can see, have died on the throne of France, and bequeathed it to his posterity, leaving a reputation which could only be surpassed in lustre by that of an individual who should render similar advantages to his country, yet decline the gratification, in any degree, of his personal ambition.

Thus, whether one considers the matter from the perspective of the interests of the governed or that of those who governed, one is struck by the immense superiority of the representative system over [149] despotism. One realizes that those who govern have just as much interest as the governed in ensuring that the nation has a say in managing its own affairs. One sees that it is at once more honorable, more dignified, and more secure to be a constitutional sovereign, supported by the industrious and enlightened classes of a nation, than to be a despot who relies solely on an administration and an army. No doubt, a constitutional government, which is necessarily bound to subordinate its own opinions and will to those of the nation, always finds itself somewhat reined in; it does not have complete free rein.

But does despotism have it? If a constitutional monarch must consult the electoral will of the national representation, is not the despot, on his side, under penalty of downfall and death, forced to keep his gaze fixed at all times on the pots of his janissaries? Which of these two positions is more honorable, more dignified, and more secure?

[150]

Now you understand why economists are not supporters of despotism. It is because they apply to the outcomes and consequences of despotism the same method of observation and analysis that they use to assess the results and consequences of revolutions. By employing this method—by examining governments as machines, as tools designed to ensure and safeguard the interests of society, to provide nations with the security they need to grow in population, wealth, and civilization—they become convinced that representative governments are infinitely superior machines compared to despotic governments.

Consequently, they are just as opposed to those who seek to destroy or corrupt representative governments as they are, for example, to machine-breakers—and for the same reasons. For the trouble-makers of despotism [24] [151] are, in our time, nothing less than machine-breakers; they are people who, blinded to both the interests of the masses and their own, strive to replace new machines, the improved tools of civilization, with the imperfect and crudetools of barbarism.

Unfortunately, hardly anyone listens to the economists. I have just spoken of machine-breakers. Despite the arguments and advice of economists, we have often seen workers, misled by ignorant or malevolent agitators, smashing new machines. In England, thirty years ago the machine-breakers gained formidable power. They roamed from town to town, from district to district, carrying out their furious work of destruction. For a moment, it seemed that the progress of industry and the development of civilization might be halted by these new barbarians.

But finally, these defending the interests of society were alarmed; [152] the forces of civilization were brought to bear against this surge of barbarism, and the machine-breakers were defeated. Well, the political machine-breakers, however much they may attempt to spread their destruction and glorify it, will ultimately meet the same fate. No matter what they do, they will inevitably be overcome, for their system is outdated, their mechanisms are worn out, and civilization no longer has any use for them. Civilization rejects despotism just as it rejects revolutions.

END OF PART TWO.

Endnotes to Despotism

[1] Speech delivered at the Museum of Industry in Brussels, on October 4, 1852. (Editor's note: Louis Napoléon proclaimed Emperor Napoléon III on December 2, 1852).

[2] (Editor's note.) Molinari says here "le bilan de la révolution".

[3] (Editor's note.) Molinari here uses the accounting terms "le passif" (liabilities) and "l'actif" (assets).

[4] See Appendix A. "On the losses of men caused by the French Revolution. On conscription under the Empire."

[5] (Editor's note.) "Cette règle tutélaire" (this protective rule). Molinari here uses here the word "tutélaire" (protective or tutelary). The idea of "la tutelle" (tutelage) would become an important one later as he believed some people were not yet ready for complete freedom and individual responsibility and thus needed to be under the "protection" of the state or some other body until such time as they were. Such groups included members of the poor working class, women, and colonized people.

[6] (Editor's note.) Molinari here uses the term "le régime prohihitif" (the regime of trade prohibitions). The other commonly used term was "le régime protectionniste" (the regime fo trade protection). The former referred to the outright prohibition of trade in certain goods. The latter referred to the imposition of tariffs which were used both too re=aise revenue for the state and to restrict the entry of foreign goods into the domestic market in order to "protect" domestic producers from competition. Sometimes the terms were used interchangeably by supporters of free trade like Molinari.

[7] See Appendix B. "On the Continental Blockade."

[8] (Editor's note.) Molinari here uses the term "la tenue des livres en partie double" (double entry bookkeeping).

[9] (Editor's note.) Molinari here uses the term "de grandes mangeuses" (huge or big eaters) which is another reference to his idea of there being "une classe bugévitoire" (a budget eating class).

[10] (Editor's note.) Molinari here uses the term "une guerre mortelle" (a war to the death).

[11] (Editor's note.) In the previous sentence Molinari contrasted "les classes supérieures" (the superior or higher classes) and "les classes inférieures" (the inferior or lower classes). In this sentence he contrasts "les classes élevées" (the higher or educated classes) and "les classes basses" (the classes at the very bottom, perhaps uneducated).

[12] (Editor's note.) Molinari here uses the term "des couches supérieures" (the upper layer or stratum) instead of upper class.

[13] This was written before the presentation of the new press law project.

[14] See Appendix C. "On the Freedom of the Press".

[15] (Editor's note.) Molinari here uses the term "la tribune" which could be translated as "Parliamentary tribune" to give it a French flavor, or perhaps "the floor of the House" to give it an English flavor.

[16] (Editor's note.) Molinari here uses the colorful term "des mangeurs de taxes (tax eaters).

[17] (Editor's note.) Three years previously Molinari had talked about "security" being an "industry" which supplies a "product" to "consumers of security" under the direction of "entrepreneurs" who run "companies" (often "insurance companies"). See his essay on "De la production de la sécurité," in Journal des Economistes, Vol. XXII, no. 95, 15 February, 1849), pp. 277-90; and Les Soirées de la Rue Saint-Lazare; entretiens sur les lois économiques et defense de la propriété (Paris: Guillaumin, 1849), "Onzième Soirée," pp. 303-37.

[18] (Editor's note.) Molinari here carefully contrasts "les payeurs de taxes" (the payers of taxes) and"les mangeurs de taxes" (the eaters of taxes.

[19] (Editor's note.) Molinari here uses the expression "lui laver la tête" (washed his hair), which in English might be translated equally colorfully as "wiped the floor with him", or since this is in a military context "gave him a good dressing down".

[20] Vie de Napoléon, vol. VIII, p. 180. The Prose Works of Sir Walter Scott, Bart: Life of Napoleon Buonaparte. Volume 14 (Edinburgh: R.Cadell, 1835), pp. 324-25.

[21] (Editor's note.) Molinari here contrasts "les intérêts de paix" (the interests of peace, the peace interest, or the interest of those in favor of peace) of "les classes industrieuses et capitalistes" (the industrial and capitalist classes) to "les intérêts de guerre" (the interests of war, the war interests, or the interests of those in favor of war) of "l'administration et de l'armée" (the administration and the army).

[22] Course of the 5 p. 100 French, at the end of the Directory, under the Consulate, and the Empire.

| Year | Highest | Lowest |

| 1799 | 22.50 | 7.00 |

| 1800 | 44.00 | 17.38 |

| 1801 | 68.00 | 39.30 |

| 1802 | 59.00 | 50.15 |

| 1803 | 66.60 | 47.00 |

| 1804 | 39.75 | 52.20 |

| 1805 | 63.30 | 51.90 |

| 1806 | 77.00 | 61.60 |

| 1807 | 93.40 | 70.75 |

| 1808 | 88.15 | 78.10 |

| 1809 | 84.00 | 76.26 |

| 1810 | 84.50 | 78.40 |

| 1811 | 83.25 | 77.70 |

| 1812 | 83.60 | 76.50 |

| 1813 | 80.20 | 47.50 |

| 1814 | 57.50 | 45.00 |

| 1815 | 69.00 | 53.00 |

[23] The Prose Works of Sir Walter Scott, Bart: Life of Napoleon Buonaparte. Volume 4 (Edinburgh: R.Cadell, 1835), pp. 58-60.

[24] (Editor's note.) Molinari here uses the expression "les fauteurs du despotism" (the trouble-makers of despotism) which is the same he used earlier with respect to anarchists, "les fauteurs de l'anarchie" p. 87. There he likened "les fauteurs de l'anarchie" (the trouble-makers of anarchy) to"les courtisans du despotisme" (the flatterers of despotism). Here he is likening "les fauteurs du despotism" (the trouble-makers of despotism) to "les briseurs de machines" (the machine breakers, or Luddites)

Appendices

[155]

Appendix (A): On the Loss of Lives Caused by the French Revolution. The Conscription Under the Empire.

This is the basis on which Sir Francis d'Ivernois established his estimate of the number of lives sacrificed by the Revolution:

"Long before the war in the Vendée had ended," says the illustrious Genevan economist, "and by the end of 1794, an official register had been published which estimated the loss of the first campaigns at eight hundred thousand Republican soldiers, including those who had died in military hospitals, and seventy thousand prisoners. This register was supported by detailed calculations made in Germany, from which it followed that by October 1795, the war had already cost [156] France more than a million men. To this number, one must now add: first, the number of Republican soldiers who perished in the Western departments; second, the destruction that took place on the banks of the Rhine and the Danube, as well as in the one hundred and eleven battles fought in Italy; and finally, one must remember that the Swiss, in their final struggle, did not fail to sell their freedom dearly. The destruction from these last three campaigns must have been at least half as great as that of the previous four, and I believe I am striking a fair balance in estimating that the war had cost France, up to this point (1799), about a million and a half soldiers.

"I do not know whether the leaders of France will accuse me of exaggeration in this dreadful calculation, and I admit that they have taken measures to deny it by ensuring the destruction of all possible evidence. This can be judged by the speech of a deputy who criticised the war offices for 'not having preserved any record or documentation indicating in which regiment such and such a citizen had been incorporated.' This was, indeed, the most certain way to bury forever in oblivion the only register that could one day reveal the true losses of France.

"If someone accuses me of exaggerating these figures, perhaps it is because they are unaware of the ravages of epidemic diseases [157] in military hospitals, which not only claimed the lives of the sick and convalescent but also most of the experienced doctors and surgeons, thereby creating yet another cause of mortality. Since new students could no longer be trained, due to the destruction or desertion of the old medical and surgical schools, the vacant positions were filled by former monks and barbers, who, under the title of ‘health officers,’ killed more people than war and famine combined. At least, that is what the deputy Vitet recently stated, and his colleague Baraillon, who deserves some credibility since he is a physician, confirmed that 'in several military hospitals, these brazen ignoramuses prescribed corrosive sublimate and arsenic as emetics. Do not believe,' he added, 'that it was the enemy’s steel that reaped the majority of our brave defenders; it was disease, and I would frighten you if I were to describe its effects.'

"This last remark alludes to another circumstance that was particularly disastrous for the Republican armies: the immense number of young boys, or rather children, whom martial zeal led to enlist before they were old enough to endure the hardships of camp life. The number of those who perished must have been considerable, since when General Jourdan proposed his new plan [158] for military conscription to raise a million soldiers, he was forced to admit that Baraillon's concerns were well-founded and that it was a compelling reason to admit only men whose physical development was complete and who were in full possession of their strength.

"By combining all these extraordinary causes of mortality, I have estimated the total loss of the French armies, on land and at sea, at 1,500,000 men.

"It is infinitely more difficult to calculate the number of lives that the Revolution cut down within the country itself, yet I fear I am falling short of the truth in estimating them at one million. I am not speaking of the precious lives lost to the permanent or traveling guillotines: as numerous as these daily executions were, they made such a deep impression only because they included women among the victims, because funeral lists were published daily, and because they contained the names of some of the purest souls in France, such as Madame Élisabeth and M. de Malesherbes. But let us first consider the peasant uprisings in 1789, where hundreds were slaughtered as they were hunted down after burning châteaux. Then we turn to the reign of the dreadful street lanterns and the desolation that now [159] characterizes the four departments beyond the Loire. I look at the innumerable insurrections that erupted across the provinces, which were only suppressed in blood. I count all those massacred in the various upheavals in Paris, the drownings in Nantes, and the mass executions in the South—the alternating massacres in Avignon, Lyon, Orange, Arles, Toulon, and Marseille. I count the exterminations that successively claimed the Constitutionalists, the Federalists, the Jacobins of Robespierre, and even the Thermidorians. I consider the priests who were slaughtered, deported, or imprisoned, along with the immense number of French citizens who were jailed as ‘suspects’ and died prematurely from disease, deprivation, starvation, anguish, and grief in their overcrowded prisons. To this dreadful catalogue, we must add the emigration—both of the nobility and the well-to-do commoners—as well as the thirty thousand plebeian farmers who, in 1793, fled Alsace to escape death. We know that they were never allowed to return to their homes, despite the Council of Five Hundred having solemnly recognized, before the 18th of Fructidor, that they were fugitives rather than emigrants.