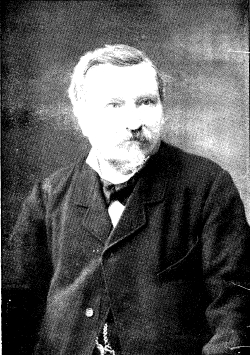

Gustave de Molinari (1819-1912)

A Brief Biography of Molinari

|

|

More Information

- see the main Molinari page

Biography

Gustave de Molinari was born in Liège on March 3, 1819 and died in Adinkerque on January 28, 1912. He was the leading representative of the laissez-faire school of classical liberalism in France in the second half of the 19th century and was still campaigning against protectionism, statism, militarism, colonialism, and socialism into his 90s on the eve of the First World War. As he said shortly before his death, his classical liberal views had remained the same throughout his long life but the world around him had managed to turn full circle in the meantime.

Molinari became active in liberal circles when he moved to Paris from his native Belgium in the 1840s to pursue a career as a journalist and political economist and was active in promoting free trade, peace, and the abolition of slavery. His liberalism was based upon the theory of natural rights (especially the right to property and individual liberty) and he advocated complete laissez-faire in economic policy and the ultra-minimal state in politics. During the 1840s he joined the Society for Political Economy and was active in the Association for Free Trade (inspired by Richard Cobden and supported by Frédéric Bastiat). During the 1848 revolution he vigorously opposed the rise of socialism and published shortly thereafter two rigorous defenses of individual liberty in which he pushed to its ultimate limits his opposition to all state intervention in the economy, including the state's monopoly of security. He published a small book called Les Soirées de la rue Saint-Lazare (1849) in which he defended the free market and private property in the form of a dialogue between a free market political economist, a conservative and a socialist. He extended the radical anti-statist ideas first presented in the "Eleventh Soirée" in an even more controversial article "De la Production de la Sécurité" in the Journal des Économistes (October 1849) where he argued that private companies (such as insurance companies) could provide police and even national security more cheaply, more efficiently and more morally than could the state.

During the 1850s he contributed a number of significant articles on free trade, peace, colonization, and slavery to the Dictionnaire de l'économie politique (1852-53) before going into exile in his native Belgium to escape the authoritarian regime of Napoleon III. He became a professor of political economy at the Musée royale de l'industrie belge and published a significant treatise on political economy (the Cours d'economie politique, 2nd edition 1863) and a number of articles opposing state education. In the 1860s Molinari returned to Paris to work on the Journal des Debats, becoming editor from 1871 to 1876. Between 1878-1883 Molinari published two of his most significant historical works in the Journal des Economistes in serial and then in book form. L'Évolution économique du dix-neuvième siècle: Théorie du progres (1880) and L'Évolution politique et la révolution (1884) were works of historical synthesis which attempted to show how modern free market "industrial" society emerged from societies in which class exploitation and economic privilege predominated, and what role the French Revolution had played in this process.

Towards the end of his long life Molinari was appointed editor of the leading journal of political economy in France, the Journal des Économistes (1881-1909). Here he continued his crusade against all forms of economic interventionism, publishing numerous articles on natural law, moral theory, religion and current economic policy. At the end of the century he published his prognosis of the direction in which society was heading. In The Society of the Future (1899) he still defended the free market in all its forms, with the only concession to his critics the admission that the private protection companies he had advocated 50 years previously might not be viable. Nevertheless, the old defender of laissez-faire still maintained that privatised, local geographic monopolies might still be preferable to nation-wide, state-run monopolies. Fortunately perhaps, he died just before the First World War broke out thus sparing himself from seeing just how destructive such national monopolies of coercion could be.

In the twenty or so years before his death (1893-1912) Molinari published numerous works attacking the resurgence of protectionism, imperialism, militarism and socialism which he believed would hamper economic development, severely restrict individual liberty and ultimately would lead to war and revolution. The key works from this period of his life are Grandeur et decadence de la guerre (1898), Esquisse de l'organisation politique et économique de la Société future (1899), Les Problèmes du XXe siècle (1901), Théorie de l'évolution: Économie de l'histoire (1908), and his aptly entitled last work Ultima Verba: Mon dernier ouvrage (1911) which appeared when he was 92 years of age.

Molinari's death in 1912 severely weakened the classical liberal movement in France. Only a few members of the "old school" remained to teach and write - the economist Yves Guyot, and the anti-war campaigner Frédéric Passy survived into the 1920s. The academic posts and editorships of the major journals were held by "new liberals" or by socialists who spurned the laissez-faire liberalism of the 19th century.