Etienne de ia Boétie, Discourse of Voluntary Servitude (c. 1550)

|

|

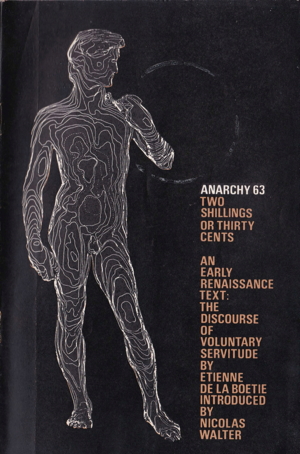

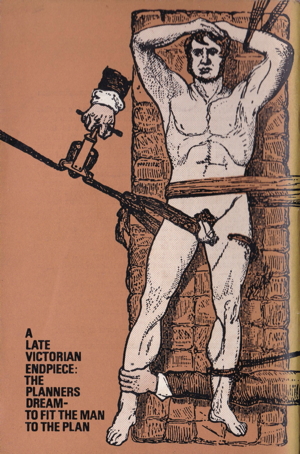

| Title page of Anarchy 63 (1966) | Back cover of Anarchy 63 (1966) |

Note: This is part of a collection of material on and by La Boétie.

Source

ANARCHY 63 (Vol 6 No 5) MAY 1966. Introduction and revised and edited translation by Nicolas Walter. "Introduction," pp. 129-37; a revised version of the 1735 translation by "T. Smith", pp. 137-52.

See the facs. PDF of the complete issue of the magazine.

Numbers in square brackets refer to the original page numbers in the magazine.

See also the original 1735 edition of the work which was used in this edition of the translation: Discourse of Voluntary Servitude. Wrote in French by Stephen de la Boetie (London: Printed for T. Smith, 1735).[facs. PDF].

About Nicolas Walter

The Wikipedia entry on him states:

"Nicolas Hardy Walter (22 November 1934 – 7 March 2000) was a British anarchist and atheist writer, speaker and activist. He was a member of the Committee of 100 and Spies for Peace, and wrote on topics of anarchism and humanism."

And the magazine ANARCHY for which he wrote:

"Anarchy was an anarchist monthly magazine produced in London from March 1961 until December 1970. It was published by Freedom Press and edited by its founder, Colin Ward with cover art on many issues by Rufus Segar. The magazine included articles on anarchism and reflections on current events from an anarchist perspective, e.g. workers control, criminology, squatting.

The magazine had irregular contributions from writers such as Marie Louise Berneri,Paul Goodman,George Woodcock, Murray Bookchin, and Nicholas Walter."

Introduction by Nicolas Walter

This is the first translation of the Discours de la Servitude Volontaire to be published in this country for more than two hundred years, so it is necessary to discuss the problems it raises in some detail.

The first problem is that the author, title and date of the essay are all uncertain. The author is generally believed to be Etienne de La Boétie (three syllables, pronounced Boh-eh-tee). He was born on 1st November, 1530, at Sarlat in the Périgord district of Guyenne in south-west France (what is now the Dordogne département ), and died of dysentery on 18th August, 1563, at Germignan, just outside Bordeaux. His father died when he was a child, and he was brought up by an uncle. He studied law at the University of Orleans, and at the early age of 23 he became a councillor in the Bordeaux parlement (assembly of lawyers). He was well-known in his lifetime, but he died very young, before his promise was fulfilled, and soon disappeared into obscurity. Very little is known about him, and when he is remembered it is usually only for two things—his close friendship with the great writer Michel de Montaigne, which was commemorated in one of Montaigne's best-known essays, De l'Amitié ;[1] and his own essay, the Discours de la Servitude Volontaire, which is one of the least-known classics of political thought. It isn't even certain that this essay was actually written by La Boétie at all; everything that is known about it comes from Montaigne, and there are some reasons to believe that Montaigne himself wrote or re-wrote it, or at least part of it.

The traditional title of the essay— Le Discours de la Servitude Volontaire —has been found cumbersome by the French, and from the time it was written it has also been known as Le Contr'un. The usual English title is a literal translation of the traditional one— The Discourse of Voluntary Servitude —but this is even more cumbersome in English than in French, and we cannot easily call the essay The Anti-One (though the most recent translator did call it Anti-Dictator). The best thing would really be to put the traditional title into plain English, and call the essay Willing Slavery, which is what it is about, but the usage [130] is too well established to change now.

The date of the essay will probably never be known. Montaigne said in his essay that he had read La Boétie's essay a "long time" before he met the author in 1557, and that La Boétie had written it "in his first youth". But when he became more specific, he gave different dates at different times. When he first wrote his essay, some time between 1571 and 1573, he said that La Boétie had written his essay when he was 18, which would make the date 1548-49; but when he revised his essay for the last time, some time between 1588 and 1592, he said that La Boétie had written his essay when he was 16, which would put the date back to 1546-47. Internal evidence, however, shows that the essay must have been composed, or at least completed, some time after 1551—it mentions the poets Du Bellay and Baif, who wrote nothing important until 1549 and 1550 respectively, and it also mentions Ronsard's poem La Franciade , which wasn't begun until 1551 (and wasn't published until 1572). But there is no direct evidence for the actual date of the essay, or for Montaigne's motives in exaggerating the youth of the author. What evidence there is suggests that La Boétie wrote it before he left university in 1550, and that it was later revised either by La Boétie himself before his death, or by Montaigne afterwards.

The second problem is the fate of the essay. It wasn't printed during the author's lifetime. Montaigne said that La Boétie "never saw it since it first escaped his hands", and that it had "long since been dispersed amongst men of understanding"—that is, circulated in manuscript among his friends, as was common in those days. When Montaigne published La Boétie's mature works in 1571, he left out this essay because, he said in the preface, it was "too dainty and delicate" for the "rough and heavy air of such an unfavourable season" —that is, too controversial for the troubled condition of France at that time.[2] Nevertheless, when Montaigne began writing his own essays, also in 1571, he did for a time propose to include his friend's essay among them. But the Massacre of St. Bartholomew, in 1572, began the final furious stage in the French religious wars, and the Protestant rebels (usually called Huguenots) began to use La Boétie's essay as propaganda against the Catholic regime. Thus part of it was published in Scotland in 1574,[3] and the whole essay was published in Holland in 1576.[4]

Montaigne was so much put out by the appearance of these pirated editions that he took fright again, and when he eventually published his own essays, in 1580, he decided that discretion was the better part of loyalty after all, and included 29 sonnets that La Boétie had written to his wife instead of the now even more dangerous essay. He explained that it had already been published "by such as seek to trouble and subvert the state", and that, although La Boétie "believed what he wrote and wrote as he thought", he had also been determined "carefully to obey and religiously to submit himself to the laws under which he was born". Montaigne's behaviour was so ambiguous and his [131] explanation so disingenuous that it has been suggested he was the author of the essay himself and attributed it to his dead friend to escape the possible consequences.[5]

Whoever wrote it, the essay was first published as a Huguenot tract and became known as such, though it remained little read. When Cardinal Richelieu wanted a copy, nearly a century after it was written, he had difficulty in finding one. But in 1727, after another century, it was at last published among Montaigne's essays by Pierre Coste,[6] though it still wasn't published in France until the time of the Revolution.[7] After that it was frequently published—as part of Montaigne's essays,[8] as a revolutionary tract,[9] or as part of La Boétie's works.[10] For a long time the only known texts of the essay were the slightly imperfect ones published in the 1570s, but a better text based on a contemporary manuscript was found and published in the nineteenth century,[11] and this is the basis of all recent editions.[12]

The first English translation of the essay was published in 1735, soon after the essay had first been included among Montaigne's essays, but for some reason it was never included in the English translations of Montaigne. [13] No English translation of the essay has been published in this country since 1735, though one was published in the United States in 1942.[14] Unfortunately the American translation, which is based on the better text, is rather bad, while the original English translation, which is based on the previous text, is very good—indeed Pierre Coste said it was "more lucid, more fluent, and more elegant" than the original French.[15] Both translations are unobtainable outside good libraries. The translation published here follows the original one, which is in the British Museum. [16] The wording hasn't been changed, but the spelling and punctuation have been brought up to date, and the text has been shortened by the omission of a dozen passages consisting of long illustrations from classical mythology and ancient and medieval history, which certainly don't make the argument any clearer and probably obscure it for most readers. (The omissions are indicated by omission points, thus . . . .)

The third problem is the purpose of the essay. It is probable that La Boétie was writing as an enthusiastic admirer of the writers who had defended liberty in ancient Greece and Rome. Such an attitude was common enough during the literary renaissance of the sixteenth century, when medieval writers were being overshadowed by classical writers such as Seneca and Plutarch and modern writers such as Rabelais and Erasmus. La Boétie was certainly familiar with contemporary literary fashions—he made translations from Greek, wrote poems in Latin and French, and knew such contemporary poets as Baif, Dorat, Du Bellay, and Ronsard. as well as being the closest friend of Montaigne. It is possible that La Boétie was also writing as an interested observer of current events in France. Such an attitude was also common enough during the religious and political conflicts of the sixteenth century, when every crisis released a fresh flood of written comment, in both manuscript and print. La Boétie was [132] certainly active in local and national politics—he was a member of the Bordeaux parlement for nine years (representing it on a mission to the Royal Court in Paris in 1560), and was involved in the efforts to prevent the growth of the religious struggle in Guyenne.

But there is a more complex question to consider. Montaigne said that La Boétie wrote his essay "in honour of liberty against tyrants''— but did he write for liberty in the abstract against tyrants in general, or for concrete liberty against a particular tyrant? Montaigne's answer was that La Boétie wrote "only by way of exercise", but many attempts have been made to show that he had some more definite purpose in mind. It was suggested at the time that he wrote to protest against Montmorency's savage suppression of the Guyenne rebellion in 1548. The greatest contemporary historian, De Thou, commented that "never after so fierce a rebellion was there a more general disposition to obey, so that from this instance the observation appears to be very true, that princes have long arms and that by the subordination of powers, linked together one under another, the body of a people in general are held fast by the secret bonds of necessity", and he added that La Boétie "took occasion from hence to pursue this thought very elegantly in a book entitled Voluntary Servitude".[17] La Boétie presumably avoided actually mentioning either the rebellion or Montmorency because the latter was the Constable of France. It has also been suggested that La Boétie wrote to contradict Machiavelli's book The Prince , which had been written in 1513 but not published until 1532.[18] Again, he presumably avoided actually mentioning either the book or the author because Catherine de Medicis—the daughter of Lorenzo dei Medici, whom The Prince had been dedicated to—was the wife of Henri II, who became king of France in 1547, and she was a well-known admirer of Machiavelli. In each case the suggestion seems plausible enough, if rather far-fetched, but in neither case is there any direct evidence.

The following facts should surely be remembered. The essay was never published by La Boétie; his name was not given to any edition of it before 1727; the version of the essay which was published mentions no contemporary person apart from three poets and one friend, no political person later than Clovis (who was king of the Franks from 481 to 511), and no contemporary event at all; La Boétie spent his whole life as a loyal member of the Catholic Church, a loyal subject of the French king, and a pillar of the establishment; a year before his death he wrote a tract about the Saint-Germain Edict of 1562 (which represented the French government's first attempt to tolerate the Huguenots), commenting that religious uniformity was necessary to the safety of the state;[19] and, according to Montaigne, "there was never a better citizen, nor more affected to the welfare and quietness of his country, nor a sharper enemy of the changes, innovations, newfangles, and hurly-burlies of his time". All this suggests that the essay, whether the author was La Boétie or Montaigne, or both, was indeed written "only by way of exercise", and that it was meant to be read only by educated men and for its literary style rather than its political [133] ideas.

The fourth problem is the importance of the essay. It is typical of the irony of history that it has in fact been read for its ideas rather than its style. As literature it has never had much importance. The great French critic, Sainte-Beuve, dismissed it as "only a classical declamation, the masterpiece of a student of rhetoric",[20] and lesser critics have seldom disputed this judgement, though it is recognised as a fine example of sixteenth-century French prose. But it has had some importance as a contribution to political thought, though this has varied and has never been large.

If the essay had been published by Montaigne in 1571, or even in 1580, it might have been important for its own sake in its own age. But before 1574 it had no importance at all, because hardly anyone read it, and after 1574 it became important only because it had been published as a tract for the time. Although La Boétie himself would probably have supported the politiques (the moderate politicians who worked for a pragmatic settlement against the religious extremists on both sides), he was posthumously enlisted on the Huguenot side as one of the monarchomachi (the sectarian writers who argued for the right of subjects to resist unjust rulers), and his essay was read as a text alongside tendentious extracts from classical works and new polemics, all to the glory of a revolution to replace the Catholic regime by a Huguenot one which he would have hated as much, if not more.

In this guise the essay had little lasting importance. It isn't mentioned at all in the standard histories of political thought in English—not, for example, by Bowles, Catlin, Doyle, Harmon, Murray, or Sabine—and it gets little more attention in the specialist studies. Professor Figgis said that it "was a mere exercise, and had no practical influence," adding that it was only "interesting as showing the influence of the classical spirit apart from religion" and "how feeble is the mere political argument for liberty".[21] Professor Allen said that it was an "exercise in rhetoric by a gifted young student" and also "an essay on the natural liberty, equality and fraternity of men", that as such it "served no Huguenot purpose", and that "it served, in truth, no purpose at all at the time, though, one day, it might come to do so".[22] Professor Gooch said that, although it "was printed in the company of Huguenot pamphlets and was eagerly read by Huguenots, it cannot fairly be taken as a specimen of their opinions at any time", and that it "pleaded not so much for republicanism as for an individualism almost amounting to anarchy".[23] The point is that La Boétie wasn't writing for his own time. In the sixteenth century, political thought was a matter above all of theology and jurisprudence, but he wasn't interested in either; he was interested in what we now call psychology and sociology. In this he resembled Machiavelli—they disagreed about the facts of political behaviour, but they agreed that facts were the thing, and this was partly why neither of them was taken seriously at the time.

Then what time did La Boétie write for? In the seventeenth [134] century, his essay was a literary curiosity, to be hunted out for the dictator of France. In the early eighteenth century, it was a footnote to Montaigne, though still dangerous enough to appear only in editions of Montaigne which were published outside France. In the late eighteenth century and early nineteenth century, it became a tract for the time once more, and was read as a text by French-speaking republicans, this time to the glory of a revolution to replace the ancien regime by a bourgeois regime which La Boétie would have hated as much as ever. In the late nineteenth century, it became a literary curiosity once more, to be hunted out this time by scholars of French literature. In the twentieth century, it has been at the same time a footnote to Montaigne, a rare curiosity, and a tract for the time—thus it is mentioned in every edition and translation of Montaigne's essays, it is occasionally published in learned editions, and it had some importance during the Second World War when editions were published in the United States (in 1942) and in Switzerland (in 1943) as a counterblast to Fascism. But its main function during the last sixty or seventy years has been as a text for anarchists and other libertarians, and for pacifists and other anti-militarists, and this is its function here.

What part has La Boétie's essay actually played in anarchist and pacifist thought? Not much. It doesn't seem to have been known to early anarchist thinkers such as Godwin, Proudhon and Bakunin, or to early pacifist thinkers such as Dymond, Garrison and Ballou. It is certain that Emerson knew it, for he wrote a poem to La Boétie;[24] it is not certain that Thoreau did, despite the frequent assertion of its influence on his essay on civil disobedience.[25] La Boétie seems to have come within the anarchist horizon during the 1890s, when Ernst Zenker, one of the earliest historians of the anarchist movement, named him as one of the precursors of anarchism,[26] and Max Nettlau, the anarchist historian, named his essay as one of the earliest anarchist texts.[27]] He still wasn't known to such anarchist scholars as Sebastien Faure and Kropotkin—thus he wasn't mentioned in the Encyclopedic anarchiste or in the famous article in the eleventh edition of the Encyclopedia Britannica.

The first important anarchist—and pacifist—who took serious notice of La Boétie was Tolstoy, who translated the essay into Russian, published long extracts from it, and quoted it in support of his assertion that subjects are implicated in the violence of their rulers.[28] After this La Boétie became more generally known among anarchists and pacifists. Gustav Landauer, the German anarchist socialist, made the essay the centre of his historical survey of revolutionary thought.[29] Rudolf Rocker, the German anarcho-syndicalist, mentioned the essay in his historical survey of the growth of and resistance to the state.[30] Bart de Ligt, the Dutch anarchist pacifist, translated it into Dutch and referred to it in support of his assertion that mass non-co-operation could prevent the Second World War[31] Hem Day, the Belgian anarchist pacifist, wrote a book about La Boétie before the Second World War[32] and published a new edition of the essay after it.[33] More recently, it has been referred to in support of non-violent [135] resistance to the Warfare State.[34]

Nowadays most but not all accounts of anarchist or pacifist thought refer to La Boétie. He doesn't appear in Joan Bondurant's study of Gandhism, but he is included among the precursors of Gandhi in the book by Gopinath Dhawan.[35] He doesn't appear in James Joll's history of anarchism, but he is included among the supposed precursors of anarchism in the book by George Woodcock.[36] His essay doesn't appear in Peter Mayer's anthology of non-violence, but it is included in the anthology by Mulford Sibley.[37] It doesn't appear in David Hoggett's bibliography of non-violence, but it is included in the new bibliography by April Carter, David Hoggett and Adam Roberts.[38] One of the difficulties has been that it has not been easily available, and one of the purposes of this edition is to make it more generally available.

The fifth problem is the meaning of the essay. The best way to discover this is of course to read it, but this has been so difficult for so long that it is worth giving a brief summary of its main argument.

The essay is rhetorical and emotional, but it is basically a study of political obedience. It is unsystematic and repetitive, but it falls roughly into three parts. A brief introduction poses the traditional question of the comparative merits of monarchic and democratic government, and then puts it aside in favour of the more important question of obedience to any government. The first part shows that government exists because people let themselves be governed, and ends when disobedience begins—or rather, when obedience ends. "You thought until today that there were tyrants?" said Anselme Bellegarrigue. "Well, you were mistaken—there are only slaves. Where no one obeys, no one commands." The second part shows that liberty is natural, not as a possession or a right, but as an instinct and a goal, and that slavery is general, not by a law of nature, but by force of habit. "Man is born free," said Rousseau, "but everywhere he is in chains." The third part shows that government is maintained from day to day because of the network of people who have an interest in its maintenance. "The authority that commands and the authority that executes," said Tolstoy, "are joined like the ends of a chain."

The essay is an individual and original contribution to the well-known theory of the "social contract"—the theory that people obey their rulers because they have made a contract to do so. Of course La Boétie did not take up either of the extreme positions—that there was an "original contract" at the beginning of the history of society, or that there was a legal or moral contract in force in any particular society. His first point was that people behave as if there were a contract—that is, they obey because in the end they would rather do so than not, and their servitude is therefore voluntary. His second point was that, since the people have made a quasi-contract, they can unmake it—if they would rather not obey, they can disobey instead. Power comes from the people, not in a theoretical but in a practical sense. The people give power to their rulers, and the people can take it away again—indeed, if the rulers are bad, they should do so.

[136]

La Boétie said how political obedience works. What he did not say—and what we have not yet learnt—is how political disobedience works.

NOTES

[1] Essais (Book 1, Chapter 27). 1 have used the earliest English translation, by John Florio, published in 1603.

[2] La Ménagre de Xénophon, les Règles de mariage de Plutarque, Lettre de consolation de Plutarque à sa femme, et vers français et latins.

[3] Included as a speech in the Second Dialogue of the Reveille-matin des Français et leurs voisins, compose par Eusèbe Philadelphe Cosmopolite en forme de dialogues and the Dialogi ab Eusebio Philadelpho Cosmopolita in Gallorum et caeterarum nationum gratiam compositi —French and Latin versions of the same work, probably written by Nicolas Barnaud, printed in Edinburgh. (The extract consists of almost all the first part of the essay.)

[4] Included in the Mémoires de l'état de France sous Charles IX —a collection produced by Simon Goulart, printed in Middleburg.

[5] See La Boétie, Montaigne, et le Contr'un (1906), and Montaigne pamphletaire, on l'énigme du Contr'un (1910), both by Arthur Annaingaud.

[6] As an Appendix to his third edition of the Essais, published in Geneva and The Hague; reprinted in the editions of 1739, 1740 (supplement to the first edition of 1724), 1745, 1754, and 1771, all published in London; text from the Mémoires de l'etat de France sous Charles IX .

[7] By "L'Ingénu" in 1789 (with Sallust's Discourse of Marius ), and by "L'Ami de la Révolution" in 1790 (as an Appendix to the eighth Philippique); both editions in modern French.

[8] In 1801 and 1802, for example.

[9] By J. B. Mesnard in 1835, by Félicité de Lamennais in 1835, and by Auguste Poupart in 1852 (with Vittorio Alfieri's Tyranny and Benjamin Constant's Usurpation).

[10] By Léon Feugère in 1846, and by Paul Bonneton in 1892.

[11] By Jean François Payen in 1853, and by Damase Jouaust in 1872.

[12] By Paul Bonnefon in 1892 and 1922, and by Maurice Rat in 1963. (The latter is still available, published by Armand Colin in Paris.)

[13] A Discourse of Voluntary Servitude, "printed for T. Smith" in London. (This T. Smith may have been the translator as well as the publisher, and may have been the Thomas Smith named as one of the subscribers to Coste's first edition of the Essais.)

[14] Anti-Dictator, "rendered into English by Harry Kurz", published by the Columbia University Press in New York.

[15] ln the Introduction to his fourth edition of the Essais, published in London in 1739.

[16] Catalogue numbers 527.b.2/2 and T. 1048(1). There is also a copy in the London Library.

[17] Book 5 of Historia sui temporis (1604). I have used the earliest English translation, by Bernard Wilson, published in 1729.

[18] See Etienne de La Boétie contre Nicolas Machiavcl (1908), by Josephe Barrère.

[19] Mémoires sur l'Edit de Janvier, first published by Paul Bonnefon in 1917, never translated into English.

[20] Causeries de Lundi (14 November, 1853), reprinted in Vol. 9 of collected edition (1854).

[21] Political Thought from Garson to Grotius (1907).

[22] A History of Political Thought in the Sixteenth Century (1928).

[23] English Democratic Ideas in the Seventeenth Century (1898).

[24] Title: "Etienne de la Boéce". First line: "I serve you not, if you I follow". Reprinted in Poems (1847).

[25] Resistance to Civil Government (1848). usually called Civil Disobedience or On the Duty of Civil Disobedience. For a typical assertion of La Boétie's influence, see Gene Sharp's Introduction to the edition published by Peace News in 1963.

[137]

[26] Der Anarchismus (1895), translated into English as Anarchism (1898).

[27] Bibliographie de l'anarchie (1897), never translated into English.

[28] Two extracts published in 1906—one in the first part of Krug Chteniya (The Reading Circle), the other with an edition of Patriotizm i Pravitelstvo (Patriotism & Government). A typical quotation appears in Zakon Lyubvi i Zakon Nasiliya (1908), translated into English by Ludvig Perno as The Law of Violence & the Law of Love (1959). Tolstoy used the edition of the essay published by the Bibliotheque Nationale in Paris in 1901. (A full account of his interest in La Boétie appears in Rassuzhdeniye o Dobrovolnom Rabstve — the Russian edition of the essay, translated by F. A. Kogan-Bernshtein, published by the Academy of Sciences in Moscow in 1952 and again in 1962.)

[29] Die Revolution (1907), never translated into English, but some extracts were published in ANARCHY 54 (August 1965).

[30] Der Nazionalismus und die Kultur, written before 1933, but first published in the English translation by Roy Chase as Nationalism & Culture (1937).

[31] La Paix Créatrice (1934) never translated into English; Pour vaincre sans violence, translated into English by Honor Tracy as The Conquest of Violence (1937).

[32] Etienne de La Boétie (1939), never translated into English.

[33] First published in 1947, reissued in 1954 with an Introduction by Hem Day (as No. 3 of Cahiers "Pensée et Action"); in modern French. (The latter is still available, published by Hem Day in Brussels.)

[34] See, for example, my Non-Violent Resistance : Men Against War (1963) based on articles in ANARCHY 13 and 14 (March and April, 1962).

[35] The Political Philosophy of Mahatma Gandhi (1946).

[36] Anarchism (1962).

[37] The Quiet Battle (1963). The contribution consists of extracts from the American translation (see Note 14).

[38] Non-Violent Action : a Selected Bibliography (1966). The edition mentioned is the American translation (see Note 14).

Etienne de la Boétie, "The Discourse of Voluntary Servitude"

Be silent, wretch, and think not here allowed

That worst of tyrants, an usurping crowd.

To one sole monarch Jove commits the sway,

His are the laws, and him let all obey .Ulysses says this in Homer, speaking in public.[39] If only he had said:

Be silent, wretch, and think not here allowed

That worst of tyrants, an usurping crowd .Nothing could have been better. But to have talked according to reason, he ought to have said that the rule of many cannot be good, since the power of a single person, from the time that he assumes the title of master, is hard and unreasonable. Yet he preposterously adds: [138]

To one sole monarch Jove commits the sway,

His are the laws, and him let all obey.But perhaps Ulysses ought to be excused, who possibly then was under a necessity of using that language and to employ it as the means to calm the mutiny of the army, conforming his discourse more, I think, to the circumstance of time than to truth.

But to speak in good earnest, it is a great misfortune to be subject to a master of whom you can never be assured that he will be good, since it is always in his power to be bad when he pleases. To have many masters, that is the same as to be so many times extremely unfortunate. At present I will not enter into the debate of that question so much canvassed, whether the other sorts of republics are better than monarchy—which, if I should consider, I would first know before I put it as a question what rank monarchy ought to have amongst republics, if it ought to have any at all, since it is very difficult to believe that there is anything public in that government where all depends on one person. But this question is reserved for another time, and may well deserve a treatise apart, or rather may indeed include all political disputes.

* * * * *

For the present, I would only understand how it is possible and how it can be that so many men, so many cities, so many nations, tolerate sometimes a single tyrant, who has no power but what they give him, who has no power to hurt them but only so far as they have the will to suffer him, who can do them no harm except when they choose rather to bear him than contradict him. A wonderful thing, certainly, and nevertheless so common that we ought to have more grief and less astonishment to see a million of millions of men serve miserably, their necks under the yoke, not constrained by a greater force but, as it were, enchanted and charmed by the single name of one whose power they ought not to be afraid of, since he is alone, nor love his qualities, since he is with regard to them inhuman and savage. Such is the weakness of mankind.

It often happens that we are obliged to obey by force. There is a necessity then of temporising; one cannot always be the strongest. If then a nation be constrained by the fate of war to become the slaves of one person, as the city of Athens was to Thirty Tyrants,[40] we ought not to be surprised at their servitude but to bewail the accident— or rather, neither to be surprised nor bewail, but to bear the evil patiently, and reserve ourselves for a future and better fortune.

Our nature is such that the common duties of friendship engross a great part of the course of our lives. It is reasonable to love virtue, to esteem good actions, to acknowledge the good we receive, and often to diminish our own ease to augment the honour and advantage of those we love when they deserve it. If therefore the inhabitants of a country have met with some great personage who has shown by proof great foresight in preserving, great courage in defending, and great care in governing them—if from thenceforward they accustom themselves to obey him and to confide so much in him as to give him [139] some prerogatives, I do not know whether it ought to be called an act of wisdom, insomuch that he is taken from that station in which he did good to be advanced to a dignity in which he may do harm; but certainly it may be called honesty and sincerity in not being afraid of receiving ill from him from whom they had received only good.

But good God!—what can this be?—what shall we call this?— what misfortune is this?—what sort of unhappy vice is it, to see an infinite number not only obey but serve, not governed but tyrannised, having neither goods, parents, children, nor life itself which can be called theirs; to bear the robberies, the debaucheries, the cruelties, not of an army, not of a barbarous camp against which we ought to spend blood, nay even our lives, but of one man—not a Hercules or Samson, but a little creature, and very often the most cowardly and effeminate of the whole nation, one not accustomed to the smoke of battles, but scarcely to the dust of tilts and tournaments—not one who can by force command men, but wholly employed in poorly serving the meanest woman?

Shall we call this cowardice? Shall we say that they who so abjectly serve are cowards and faint-hearted? If two, three, or four do not defend themselves from one, it is strange, but nevertheless possible; we may safely say that it is want of courage. But if a hundred, a thousand bear with one, it cannot be said that they dare not attack him, for it is not cowardice, but rather contempt and disdain. If we see not a hundred, not a thousand men, but a hundred provinces, a thousand cities, a million of men not attack one man, whose greatest favourite has yet the misfortune to be made his slave and vassal, what can we call this? Can it be cowardice? But there is in all vices naturally some boundary and degree beyond which they cannot pass. Two and perhaps ten may be afraid of one, but if a thousand, a million of men, if a thousand of cities do not defend themselves from one man, that is not cowardice. Cowardice cannot extend so far, no more than any valour can be so great that one alone should scale a fortress, attack an army, or conquer a kingdom.

Then what monster of vices is this that does not deserve the name of cowardice, which cannot find a name bad enough for it, which nature disowns and the tongue refuses to pronounce? Let fifty thousand men in arms be placed on one side and as many on the other, let them be ranged in order, let the battle begin, one side fighting for their liberties, the other to take them away—to which side shall we by conjecture promise the victory? Which can we think will go with most courage to battle, whether they who as a reward of their danger hope for the preservation of their liberty, or those who can expect no other recompense for the blows they give or receive but the enslaving of others? One side has always before their eyes the happiness of their past life and the expectation of like ease for the time to come; they do not so much consider what they endure, the short time the battle lasts, as that which must for ever be borne by them, their children, and all their posterity. The others have nothing which emboldens them but a degree of covetousness, which recoils when [140] danger approaches, and cannot be so ardent but that it ought and must be extinguished by the least drop of blood which issues from their wounds.

In those so renowned battles of Miltiades,[41] Leonidas,[42] and Themistocles,[43] which were fought two thousand years ago and live as fresh in the memory of books and men as if they had been but of yesterday, which were fought in Greece, for the good of Greece, and for the example of the world—what, think we, was it which gave to such a handful as the Greeks were, not the power but the courage to sustain the shock of so many ships that the sea itself seemed to labour under them, to defeat so many nations and so numerous that the squadron of Greeks could not have furnished, if there had been occasion, captains for their fleet—but that in those glorious days it was not so much a battle of Greeks against Persians as the victory of liberty over tyranny and immunity over avarice?

The valour which liberty inspires in the breasts of those who defend her is worthy of admiration. But that which is done in all countries and every day, that one man alone should lord it over a hundred cities and deprive them of their liberty—who would believe it if it were only hearsay that he did not see it? And if it were only seen in foreign and distant countries and reported here, who would not think that it were rather a fiction and imaginary than real?

But yet there is no need of attacking this single tyrant, there is no necessity of defending oneself against him. He is defeated of himself, provided only the country does not submit to servitude. There is no need of taking anything from him; only give him nothing. There is no occasion that the country should put itself to the trouble of doing anything for itself, if it do nothing against itself. It is the people themselves who suffer, or rather give themselves up to be devoured, since in ceasing to obey him they would be free. It is the people who enslave themselves, who cut their own throats, who, having the choice of being vassals or freemen, reject their liberty and submit to the yoke, who consent to their own evil, or rather procure it.

If the recovery of their liberty were to cost them anything, I would not press it, although the replacing himself in his natural right and, as I may say of a beast, to become a man, is what everyone ought to hold most dear. But still I do not require so much courage in him. I do not allow indeed that he should prefer an uncertain precarious security of living at his ease. What! —if to obtain his liberty he need only desire it, if there be only wanting a bare volition, can there be found a nation in the world who would think it too dear, being able to gain it by a single wish? Who would grudge the will of recovering a good, which we ought to purchase at the price of our blood, and which lost, every man of honour ought to look upon life itself as a burden, and death a deliverance?

Certainly, just as the fire of a little spark becomes great and always increases, and the more fuel it finds the readier it is to burn, but if no fuel be added to it it consumes itself and is extinguished— even so tyrants, the more they plunder, the more they require; the [141] more they ruin and destroy, the more is given them; the more they are obeyed, so much the more do they fortify themselves, become stronger and more able to annihilate and destroy all. If nothing be given them, if they be not obeyed—without fighting, without striking a blow—they remain naked, disarmed, and are nothing; like as the root of a tree, receiving no moisture or nourishment, becomes dry and dead.

The bold to acquire the good fought for fear no danger, the prudent no labour. The cowardly and stupid can neither support the evil nor recover the good. They content themselves with the bare desire of it, and the virtue of endeavouring to procure it is lost by their cowardice, although the desire of having it remains with them by nature. This desire, this will to obtain all things the possession of which would make them happy, is common to the wise and to the foolish, to the brave and to the pusillanimous. I know not how it is, but nature seems to have been wanting in one thing alone to mankind—in not giving them the desire of liberty. And yet liberty is so great a good and so lovely that where it is lost all evils follow one upon another, and even the good which may remain entirely loses its gust and flavour, being spoiled by servitude. Liberty alone men do not desire, for no other reason, it seems to me, than that if they should desire it they might have it—as if they refused to make this great acquisition only because it is too easy.

Poor and miserable creatures, people infatuated, nations obstinate in your own evil and blind to your own good! You permit the finest and clearest of your revenues to be carried off before your eyes, your fields to be pillaged, your houses to be robbed and despoiled of your ancient and paternal furniture. You live in such a manner that you cannot say anything is your own. Does it seem so great a happiness henceforward to possess by halves only your goods, your families, and your lives? And all this destruction, havoc and ruin came upon you not from enemies, but certainly from the enemy—from a man whom you yourselves make so great as he is, for whom you go so courageously to war, and for whose grandeur you do not refuse to lose your lives.

He who so domineers over you has only two eyes, two hands, and one body, and has nothing but what the least man of the infinite number of your own cities has as well as he, except it be the power you yourselves give him for your own destruction. From whence has he so many eyes to watch you, if you do not give them? How has he so many hands to strike you, if he does not take them from you? The feet with which he tramples upon your cities, whence hath he them if they be not yours? How can he have any power over you but from yourselves? How would he dare so furiously to invade you, if he had not intelligence with you? What could he do to you, if you did not protect the robber that pillages you? You are accomplices of the murderer who kills you, and traitors to yourselves. You sow and plant that he may destroy. You furnish your houses to be a supply for his robberies. You bring up your daughters that he may have wherewithal to satiate his lust. You educate your sons that he [142] may train them to his wars, that he may send them to slaughter and make them the instruments of his rapine and executors of his vengeance. You wear out your own bodies that he may soothe himself in his enjoyments and wallow in his filthy and beastly pleasures. You weaken yourselves to make him stronger and more able to bridle and keep you under.

You might deliver yourselves from so many indignities, which the beasts themselves if they felt them would not endure, if you had but the will to attempt it. Resolve not to obey, and you are free. I do not advise you to shake or overturn him—forbear only to support him, and you will see him, like a great colossus from which the base is taken away, fall with his own weight and be broken in pieces.

* * * * *

But certainly physicians advise well not to tamper with incurable wounds, and I do not act wisely in giving advice to people concerning theirs who have lost long ago all knowledge of it, and whose insensibility alone shows it to be mortal. Let us then endeavour to conjecture, if we can, how this obstinate desire of slavery has so far taken root that it would seem at present the love itself of liberty were not so natural.

First, then, I believe it is past doubt that, if we lived in possession of the rights nature has given us and followed her dictates, we would naturally be obedient to our parents, subject to reason, and slaves only in so far as nature without any other advertisement points out to us obedience to our father or mother. All men are witnesses, every one in himself and for himself, if reason be born with us or not— which is a question thoroughly discussed by the academics and touched by every different school of the philosophers. At present I shall take it for granted that there is in our souls some natural seed of reason which, being nourished by good advice and custom, in time flourishes in virtue, and which, on the contrary, being often not able to resist vices that surround it, is choked up and perishes.

But, surely, if there be anything clear and certain in nature and of which there is no excuse for ignorance, it is this—that nature, the minister of God and governor of Man, has made us all of the same form and, as it would seem, in the same mould, to the end we should all know each other for companions, or rather brothers. And if, in distributing the presents she has made, she has bestowed some advantages either in mind or body to some more than others, she did not therefore intend to send us into this world as it were into a place for combat, and has not sent down here below the strongest and most able as robbers armed into a forest to spoil the weakest; but rather we ought to believe that by thus assigning to some the greater parts, to others the lesser, she would thereby make way for brotherly affection to exercise itself, some having ability to give aid, and others need of receiving it.

Since then this good mother has given all of us this earth for a habitation, has lodged all of us in some manner or other in the same house, has made us all of the same paste, that everyone might behold [143] himself and, as it were, see his own image in his neighbour—if she have given to all of us in common that great present of voice and speech to unite us in brotherly affection and to make by the common and mutual declaration of our thoughts a communication of wills, and if she have endeavoured by all means to bind and tie closer the knot of our alliance and society—if she have shown in all things that she did not mean to make us all united as to make us all one—we ought not to doubt but that we are all naturally free, since we are all companions, and it cannot enter into the thought of anyone that nature has placed us in servitude, having made us all equal.

But, in truth, it is idle to dispute whether liberty be natural, since no one can be held in slavery without having injustice done him, and there is nothing in the world so contrary to nature, she being altogether reasonable, as injustice. We may then truly affirm that liberty is natural, and for the same reason, in my opinion, that we are not only born in possession of our freedom but with an affection to defend it. But if it so happen that we make any doubt of this and are so degenerated that we are not able to know our own good, nor likewise our true affections, it is fitting that I show mankind the dignity of their nature and made the brute beasts themselves teach them their true condition.

The beasts, if men are not too deaf to hear, cry aloud to them Liberty ! There are many amongst them who die as soon as they are taken. As the fish lose their life as soon as they are taken out of the water, so likewise those leave the light and will not survive their natural freedom. If the animals had amongst them orders and degrees they would make, in my opinion, their nobility consist in freedom. Others, from the greatest to the smallest, when they are taken make so great a resistance with their nails, claws, hooves, feet, and bills, that they sufficiently show how dearly they prize what they lose. Then when they are taken they give so many apparent signs of the sense they have of their misfortune that it is a pleasure to observe they rather languish afterwards than live, and that they continue their life more to bewail their lost happiness than to please themselves in their bondage.

What does the elephant give us to understand, who when he has defended himself so long as he is able, seeing no remedy, and just upon the point of being taken, dashes his jaws and breaks his teeth against the trees, but that the great desire he has to remain free as he was born gives him the wit and the thought of merchandising with the hunters, and to try if at the expense of his teeth he may get free and if he may be allowed to truck his ivory and pay that ransom for his liberty? We train the horse from the time he is foaled to accustom him to servitude, and yet we cannot soothe him so much but that when we come to break him he will bite the bit and kick at the spur, to show as it were his nature and testify at least that if he do serve it is not willingly but by constraint. . , .

Since, then, all things that have sentiment, from the time they have it perceive the evil of subjection and run greedily after liberty, [144] since the beasts which are even made for the service of man cannot accustom themselves to serve but with reluctance, what fatality is it which has been able so far to unnaturalise man, alone born to live free, as to make him lose the very remembrance of his first state and the desire of recovering it?

There are three sorts of tyrants—some obtain the kingdom by election of the people, some by conquest, and others by succession. Those who have acquired it by right of war behave themselves in such manner that it is well known they are, as one may say, in a land won by conquest. Those who are born kings are commonly little better, but being nourished from the infancy with the milk of tyranny look upon the people as their hereditary slaves, and according to that complexion to which they are most inclined—avarice or prodigality, such as it is—use the kingdom as their patrimony. He to whom the people have given the sovereignty ought to be, I should think, more supportable and would be so, as I believe, were it not that from the time he sees himself elevated above the rest into that station, flattered by I know not what—they call it grandeur—he resolves not to suffer the least diminution of it. Commonly such a one makes account to transmit to his children the power which he himself had received from the people. From the time he entertains this notion, it is incredible how far he surpasses in all sorts of vices—and even cruelty—other tyrants. He sees no other way to secure this new tyranny but by spreading wide the yoke and alienating the subjects so much from liberty, although the memory of it be yet fresh, that at length he may make them entirely forget it.

Therefore, to say truth, I see there is some difference between them, as to the means by which they come to reign, but which to prefer I know not, their manner of reigning being still the same. Those that are elected treat the people as wild bulls which they would tame; the conquerors think they have a right as over their prey; those by succession use them as their slaves.

But to the purpose. If by chance some people should be born now, quite new, neither accustomed to subjection nor charmed with liberty, and that they knew not either the one or the other, and scarcely their names. If it were offered to them either to be subjects or to live free, which would they choose? We can make no doubt but they would love much better to obey only reason than serve any man —excepting perhaps the people of Israel, who without constraint, without any need, made themselves a tyrant (the history of which people I scarce ever read but I conceive such a rage against them as even to become inhuman enough to rejoice at the evils which befell them).

But certainly to all men, so long as they have anything of Man, before they suffer themselves to be enslaved, one of these two things must happen—either that they are forced or deceived. Forced by foreign arms, as Sparta and Athens were by the arms of Alexander[44] or by faction, as the government of Athens had some time before come into the hands of Pisistratus.[45] By deceit they often lose their [145] liberty, and in that they are not so often seduced by others as deceived by themselves. Thus the people of Syracuse, the capital of Sicily, being pressed by wars, inconsiderately reflecting only on the present danger, advanced Dionysius and made him general of the army, and took no heed until they had made him so great that this their general, returning victorious as if he had not vanquished his enemies but his citizens, from captain made himself king, and from king, tyrant.[46]

It is incredible how suddenly the people the moment they are enslaved fall into so profound a forgetfulness of their freedom that it is not possible for them to rouse themselves up to regain it, serving so easily and so willingly that one who sees them would be tempted to say that they had not lost their liberty but their servitude. It is true, at first they serve by constraint, subdued by force. But those who come afterwards, having never seen liberty and not knowing what it is, obey without regret and do willingly that which their forefathers did by constraint. So it is that when men are born under the yoke, and being afterwards brought up and educated in slavery, without looking forward, contenting themselves to live in the condition in which they were born, and thinking they have no other right or other good but what they found at first, they look upon the state of their birth as their natural state. Nevertheless, there is scarcely any heir so prodigal and careless, but sometimes he peruses his deeds to see if he enjoy all the rights of his succession, or whether any person has encroached upon him or his ancestors. But certainly custom, which has in everything great power over us, is in no point so prevalent as in this, of teaching us to serve and—as is reported of Mithridates, who accustomed himself to drink poison[47] —of learning us to swallow and not perceive the bitterness of the venom of servitude.

We cannot deny but that nature has a great share in us to draw us which way she pleases, and that we may be said to be either well or ill born. But it must be likewise confessed that she has less power over us than custom, since with regard to our natural disposition, how good soever it be, it is lost if it be not encouraged, and education forms us always after her own fashion, whatsoever it be, in spite of nature. The seeds of good which nature sows in us are so small and slippery that they do not resist the least shock of a contrary nurture. They are not so easily preserved as they degenerate, perish, and come to nothing, just as fruit trees, which all have their peculiar nature, which they keep if encouraged, but leave it immediately, to bear foreign fruits and not their own, according as they are engrafted. The herbs have each their property and nature—nevertheless, the frost, the weather, the soil, or the hand of the gardener, either improves or diminishes much of their virtue. The plant which is seen in one place can be scarce known in another. . . .

To what purpose is all this? Not certainly that I think the country and soil signify anything, for in all countries and in every climate servitude is disagreeable, and liberty sweet. But I am of the opinion that we should pity those who at their birth find the yoke about their necks, and that we ought either to excuse or pardon them if, [146] having never seen so much as the shadow of liberty and not being advertised of it, they are not sensible of the misfortune they labour under in being slaves. If there be some countries, as Homer relates of the Cimmerians,[48] where the sun appears otherwise than to us, and after having shone on them six months without intermission he leaves them sleeping in obscurity without coming to revisit them the other half year—-would one wonder that those who should be born during this long night and had never seen the day nor heard any mention of light should accustom themselves to the darkness in which they were bred without desiring the light? We never pine for what we never had, regret never comes but after pleasure, and the remembrance of past joy is ever accompanied with the knowledge of the good once possessed. The natural disposition of man is to be free and to desire to be so, but likewise his nature is such that he always retains the bias which education gives him.

Let us conclude, then, although all things may be said to be natural to man in which he has been brought up, and to which he has been accustomed, yet only that is truly so to which his pure and unchanged nature calls him. So the first reason of this voluntary servitude is custom-—like the generous steeds who at first bite the bit but afterwards play with it, and whereas not long ago they would not endure the saddle, they now patiently submit to the harness and full of pride march stately under their trappings. The people say they have always been subjects, that their fathers lived so. They think they are bound patiently to endure the curb, and make themselves believe it by examples, and ground their opinion upon the length of time and the possession of those who tyrannise over them. But certainly length of time gives no right to do ill but rather heightens the injury.

There are always some better born than the rest, who are sensible of the weight of the yoke and cannot refrain from showing it off, who can never become tame in subjection, but always—like Ulysses, who by sea and by land was continually endeavouring to see the smoke of his own chimneys—cannot help reflecting on their natural privileges and remembering their predecessors and former condition. These are the men who, having clear understandings and sharp-sighted wits, are not satisfied with the bulk of the people in looking only where they step, but likewise take a view both of what is before and behind them, and recall the memory of things past to compare with the present and make a judgement of the future. These are they who, having good heads of their own, have besides that improved them by study and knowledge. These men, were liberty entirely lost and out of the world, conceiving it and finding it in their own minds and charmed with its lovely image, could never relish servitude, how finely soever it might be dressed up. The Great Turk[49] was well apprised of this, that books and literature give men occasion more than anything else of knowing themselves and hating tyranny, and, as I am informed, in his dominions he has not many more learned men than he would wish. But commonly the great zeal and affection of those who have preserved in spite of time a devotion for freedom, how large soever their number [147] may be, remain without effect, by their not knowing one another. The liberty either of doing or speaking, and almost of thinking, is taken away from them by the tyrant—they are all single in their opinions. . . .

Anyone who would run over the actions of times past and the ancient annals will find few or none of those who, seeing their country ill-treated and in bad hands, have attempted with a good intention its delivery, but have gained their point, and liberty in showing itself has itself brought aid. ... As they thought virtuously, so they achieved happily. In such a case, fortune was scarce ever wanting to a good will. Brutus the Younger and Cassius happily shook off slavery, but in restoring liberty they died, though not miserably—for how great a crime would it be to say there was anything miserable either in the life or death of such men?[50] But their fall was to the great loss, the perpetual misfortune and entire ruin of the commonwealth which, in my opinion, was buried with them. The enterprises against the other Roman emperors were only conspiracies of ambitious men who are not to be pitied for the inconveniences they fell under, it being easy to see their intention was not to take away but to usurp the crown, pretending to dethrone the tyrant and yet designing to retain the tyranny. To those I would not have wished success, and I am pleased that they have shown by their example the sacred name of liberty ought not to be abused to any sinister end.

But to return to the purpose from which I have digressed, the first reason why men serve willingly is that they are born slaves and bred up such. From this proceeds another, that the people easily become cowardly and effeminate under tyrants. . . . Courage is lost with liberty. An enslaved people have no spirit to fight. They meet danger like slaves tied together by a chain, dull and lifeless, and do not feel that ardour for freedom glowing in their breasts which inspires a contempt of danger and the ambition of purchasing by a noble death a glorious name amongst their companions. Free men contend who shall fight most valiantly, each one for the common good and each for himself—they expect to have all their share either in the disgrace of the defeat or in the glory of the victory. But the enslaved, besides the loss of this warlike courage, lose also their vivacity in everything else, have hearts low and effeminate, and are incapable of anything great. This tyrants know, and perceiving their bias do all they can to cherish this disposition and make them more weak and effeminate. . . .

All tyrants have not openly declared that they would make their people effeminate, but in truth what this one formally and expressly ordained they have underhand for the most part compassed. It is in truth the natural disposition of the meaner sort whose number is always greatest in cities. They are suspicious with regard to him who loves them and credulous towards him who deceives them. I do not think there is a bird more easily allured by a pipe nor a fish that more greedily swallows the bait than all the lower people are inveigled into servitude for the most childish trifle that is but shown them. It is [148] indeed a wonderful thing that they should suffer themselves to be caught so soon as the bait is offered. ... It moves pity to hear of how many things the tyrants of former times took advantage to establish their tyranny, of how many little means they made great use, having found the populace ready to be bubbled, for whom they could spread no net but what they were taken in, and in deceiving of whom they have always succeeded so well that they never more enslaved them than when they most made a jest of them. . . .

But to return from where I know not how I have turned the thread of my discourse. Has it ever been otherwise but that tyrants to secure themselves have always tried to inure the people not only to obedience and servitude but even to a kind of devotion towards them? Therefore, what I have said hitherto, which shows that the people serve voluntarily, is of no use to tyrants but with respect to the low and mean populace.

* * * * *

But now I come, in my opinion, to the point which is the true and perfect spring of sovereignty, the very bulwark and foundation of tyranny. Whoever thinks that the halberds of the guards and the arms of the sentinels are the security of tyrants in my judgement is much deceived. They make use of them, I believe, more for show and ostentation than for any confidence they place in them. The guards hinder from entering into the palace those who are inexpert, who have not concerted well their measures, not those who are armed and able to execute any enterprise. It would appear upon inquiry that there have not been so many Roman emperors who have been preserved by their guards as have perished by them.[51] Troops of horse, companies of foot, are not the arms by which tyrants are defended. At first one can scarcely believe it, nevertheless it is true.

There are always four or five who support the tyrant, four or five who keep all the country in bondage. It has always so happened that five or six have had the tyrant's ear, have made their way to him of themselves, or been called by him to be the accomplices of his cruelties, the companions of his pleasures, panders to his lust, and sharers of his plunders. These six manage their chief so well that by the bond of society he must be wicked, not only to gratify his own propensity but likewise theirs. These six have six hundred which spoil under them, and these six hundred are to them what the six are to the tyrant. These six hundred have under them six thousand whom they have raised to posts, to whom they have given either the government of provinces or the management of the public moneys, that they may be instruments of their avarice and cruelty, and execute their orders at a proper time. These subordinate officers do so much mischief to their fellow-citizens that they cannot live but under the shadow of their superiors, nor escape the punishment due to their crimes by the laws but through their connivance and protection. The consequence of this is fatal indeed.

Whoever will amuse himself in tracing this chain will see that not only the six thousand, but the one hundred thousand, the millions, are [149] fastened to the tyrant by it. . . . In short it comes to this, that what by favours, emoluments, and sharing of the plunder with tyrants, there are almost as many to whom tyranny is profitable as there are to whom liberty would be agreeable. Just as physicians say that if there be a gangrene in our bodies and a fermentation arises anywhere else, it immediately flows towards the corrupted part—even so from the instant a king commences tyrant, all the wicked, all the dregs of a kingdom (I do not say a gang of thieves and robbers, who can neither do harm nor good to the commonwealth, but those who are remarkable for unmeasurable ambition and insatiable avarice), crowd about him to have their share of the booty and be under the great tyrant, tyrants themselves. This is the way of the great robbers and of the famous pirates. Some take a view of the country, others pursue and rob the travellers, some lie in ambush, others are scouts, some murder, others pillage; and although there are amongst them different ranks, and some are only servants, others leaders and chiefs of the troop, there is not one of them who does not participate of the principal booty at least in the trouble of finding it out. . . .

Thus the tyrant enslaves his subjects by the means of one another, and is guarded by those of whom, if they had any spirit, he ought to be afraid—but, as we say, to cleave wood, wedges are made of the wood itself. These are his true guards and halberdiers. Not but that they themselves sometimes suffer by him, but then these wretches, abandoned of God and man, are content to bear the evil so that they may but return it, not upon him who does them the injury, but upon those who suffer as well as they and cannot retaliate.

And yet when I see these men thus flattering the tyrant to make their own use of his tyranny and the bondage of the people, I often wonder at their wickedness and sometimes pity their stupidity. For in truth what is it to be near the person of a tyrant, but to be the further from liberty and, as I may say, to grasp with both hands and embrace servitude? Let them only for a while lay aside their ambition and moderate a little their avarice, and then let them view and know themselves. They cannot but see that the farmers, the husbandmen whom they trample underfoot as much as possible and use worse than galley-slaves—they must see, I say, that these men, so ill-treated, are nevertheless in comparison of them happy and in some manner free. The labourer and artisan, notwithstanding they are servants to their masters, are quit by doing what they are bid. But the tyrant sees those that are about him begging and suing for his favour, and they must not only do what he commands, but they must think as he would have them, and must often to satisfy him even prevent his thoughts. It is not sufficient to obey him, they must also please him, they must harass, torment, nay kill themselves in his service, and— for they must be pleased with his pleasures—they must leave their own taste for his, force their inclination, and throw off their natural dispositions. They must carefully observe his words, his voice, his eyes, and even his nod. They must have neither eyes, feet, nor hands, but what must be all upon the watch to spy out his will and discover [150] his thoughts.

Is this to live happily? Does it indeed deserve the name of life? Is there anything in the world so unsupportable—I do not say to a man well born, but to one that has common sense or, without more, the face of a man? What condition can be more miserable than to live in this manner, to have nothing that can be called their own, holding from another ease, liberty, body, and life? But they serve to get estates—as if they could get anything which properly may be said to belong to them when they cannot say of themselves that they are their own masters, and as if anyone could have anything his own under a tyrant! They flatter themselves that their estates are their own, and do not reflect that they give him the power to take all from all and leave nothing which can be said to belong to anybody. They see that nothing renders men objects of his cruelty but riches, and there is no crime worthy of death with him but the having an estate—that he loves nothing but riches, that he destroys only the rich who come to present themselves as it were before the executioner, to offer themselves fat and well fed as a fit sacrifice.

These favourites ought not so much to think of those who have gained great estates under tyrants as of those who having for some little time heaped up wealth have shortly after lost both their estates and their lives. They ought not to call to mind how many others have gained riches, but how little time they have kept them. Search all the ancient histories, reflect on those within our own times, and you will plainly see how great the number of those who, having gained the ear of their princes by bad means and having either found employment for their wickedness or abused their credulity, have at length been reduced to nothing by those very princes, who have been no less inconstant than profuse in their favours, and as forward to destroy as they were to raise their favourites. Certainly among so great a number who have been always about bad kings there are few, if any, who have not felt some time or other in their own persons that very cruelty which they had before excited against others, and, having for the most part enriched themselves under the shadow of his favour with the spoils of others, they themselves at last have enriched others with their own spoils. Even good men, if sometimes it happens that such are beloved by the tyrant, the more they are in his favour, so much the more their virtue and integrity shine in them and strike with awe and reverence the most wicked when they behold them so near. But the virtuous themselves cannot remain long before they partake of the common misfortune and feel to their cost the effects of tyranny. . . .

It is certain the tyrant never loves nor is beloved. Friendship is a sacred word, a holy thing. It never subsists but between good men, nor commences but by mutual esteem. It is kept up not so much by a benefit received or conferred as by a virtuous life. That which makes one friend assured of another is the knowledge he has of his integrity. The sureties he has for him are his good disposition, his truth and constancy. No friendship can subsist where there is cruelty, treachery, and injustice. When the wicked meet together, it is a conspiracy, not [151] a society of friends. They cannot mutually aid, but are afraid of one another. They are not friends, but confederates in guilt.

But if this were not the case, still it would be very difficult to find in a tyrant a love to be depended on. For being above all, and having no companion, he is already without the bounds of friendship, which are fixed in equity, never halting but always the same. For which reason there is, as we say, even among thieves some honesty in dividing the spoil, because they are companions and equals, and if they do not love one another they are afraid of each other, and are not willing by their disunion to make their cause less. But those who are favourites of the tyrant can never be secure, since he has learnt from them that he can do anything, and that there is neither any tie nor duty can bind him, looking upon his will for reason, and that he has no companion, but is master of all.

Is it not then great pity that, seeing so many evident examples and the danger so near, nobody will become wise at the expense of others—that of so many who willingly get about tyrants there is not one who has the prudence or courage to tell them that which the fox, as the fable[52] says, told the lion when he counterfeited himself sick: "I would go to visit you in your den with all my heart, but that I see many traces of beasts going into you but none returning"? These wretches behold the shining treasures of the tyrant and regard with astonishment the rays of his splendour, and enticed by this blindness they come near and do not perceive that they rush into the flame which cannot fail to consume them. So the unwary satyr in the fable, seeing the fire found by the wise Prometheus shine bright, thought it so pretty that he went to kiss it, and burnt himself.[53] So the butterfly, hoping to enjoy some pleasure, flies into the fire because it shines, but feels to its cost its other virtue, that of burning. . . .

Can it then be that anyone can be found who in so great peril, with so little security, will take this unfortunate place to serve with so great trouble such a dangerous master? Good God, what suffering, what martyrdom is this—to be night and day only intent to please one, and yet more afraid of him than of any man alive; to have the eye always in watch, the ear listening, to discover the snares and from what hand the blow may come; to observe carefully the countenance of one's companions to guess who may be the traitor; to smile upon everybody and yet be afraid of all; to have not one either an open enemy or an assured friend; to have a countenance always cheerful, and the heart half dead with fear; to be incapable of joy, yet not dare to show grief!

But it is a pleasure to consider what it is they gain by this vast torment, and what good they can expect for all this anxiety and this miserable life. The people generally for all the evils they suffer accuse not the tyrant but those who govern him. Their own countrymen, even the peasants and labourers, foreign nations—nay, all the world know the names of these men, and in emulation one of another proclaim their vices. They heap on them a thousand outrages, a thousand affronts, a thousand curses. All their prayers, all their vows [152] are made against these men. They reproach them with all their misfortunes, all their plagues, and all their wants. And if sometimes in appearance they do them honour, even then they curse them in their hearts and have them in greater horror than wild beasts. Behold the glory, behold the honour they receive for their services to the people -- who, were every one of them to have a piece of their mangled body, would not, I believe, be satisfied nor half content with their punishment ! But still, after they are dead those who come after them are never so indolent but that the names of these men-devourers[54] are blackened by the ink of a thousand pens, their reputations torn in a thousand books, and even their bones, as we may say, dragged by posterity punishing them even after their deaths for their wicked lives.

Let us then at length learn to do good. Let us lift up our eyes for our own honour or for the the love of virtue to God omnipotent, the infallible witness of our actions, and the just judge of our crimes. For my own part I am persuaded, and I think I have just grounds for it, that since nothing is so hateful to God, who is all bounty and goodness, as tyranny, he must must assuredly reserve some peculair punishment in hell for tyrants and their accomplices.

* * * * *

Endnotes

[39] Iliad 2: 204-5. Ulysses is preventing the Greek soldiers from abandoning Troy and returning home.

[40] The Thirty Tyrants seized power in Athens in 404 BC.

[41] The Battle of Marathon, in 492 BC.

[42] The Battle of Thermopylae in 480 BC.

[43] The Battle of Salamis, in 480 BC.

[44] Athens and Sparta submitted to Alexander the Great in 336 BC.

[45] Pisistratus seized power in Athens in 561, in 550, and again in 540 BC.

[46] Dionysius I seized power in Syracuse in 405 BC.

[47] Mithridates Eupator was King of Pontus (in Northern Asia Minor) from 113 to 67 Bc. The story comes from Pliny's Natural History 24:11.

[48] Odyssey 11: 14-19. The Cimmerians (also described in Herodotus's Histories) were a barbarian people who were active north of the Black Sea in the eighth and seventh centuries BC, and gave their name to Crimea.

[49] The Ottoman Sultan of Constantinople was often called the Great (or Grand) Turk.

[50] Brutus and Cassius helped to assassinate Julius Caesar in 44 BC, and committed suicide after being defeated by Marcus Antonius at the Battles of Philippi in 42 BC.

[51] In fact, about a third of the Roman Emperors were killed by their own soldiers.

[52] By Aesop.

[53] Aeschylus's Prometheus the Firebearer (fragment).

[54] The word usesd by Homer, Iliad 1: 341.