Yves Guyot, Socialistic Fallacies (1910)

|

|

| Yves Guyot (1843-1928) |

This is part of a collection of works by Yves Guyot.

Source

Yves Guyot, Socialistic Fallacies (London: Cope and Fenwick, 1910).

See also the facs. PDF.

And the French original in HTML and facs. PDF. Its original title was Sophismes socialistes et faits économiques the translation of which is "Socialist Sophisms and Economic Facts".

Table of Contents

Preface to the English Edition

BOOK I. UTOPIAS AND COMMUNISTIC EXPERIMENTS.

CHAPTER

- Plato's Romance

- The Kingdom of the Incas

- Sir Thomas More's Utopia and Its Applications

- Andreæ and Campanella

- Paraguay

- Morelly and the "Code de la Nature"

- Robert Owen and "New Harmony"

- Fourier and the American Phalanx

- The Oneida Community

- Cabet and the American Icarians

- American Experiments

BOOK II. SOCIALISTIC THEORIES.

CHAPTER

- Saint Simon

- Pierre Leroux and the "Circulus"

- Louis Blanc and the Organisation of Labour

- The Labour Conferences at the Luxembourg and the National Workshops

- The Right to Work

- Proudhon's Theories

- Proudhon's Proposed Decrees and the Bank of Exchange

BOOK III. THE POSTULATES OF GERMAN SOCIALISM.

CHAPTER

- "True" Socialism

- The Claims of Marx and Engels

- The Sources of German Socialism

- Formula B and the "Iron Law of Wages"

- Formula A, Work the Measure of Value

- Karl Marx and Formulæ A, B, and C

- The Discoveries of Karl Marx and the Facts

- The Two Classes

BOOK IV. THE DISTRIBUTION OF CAPITAL.

CHAPTER

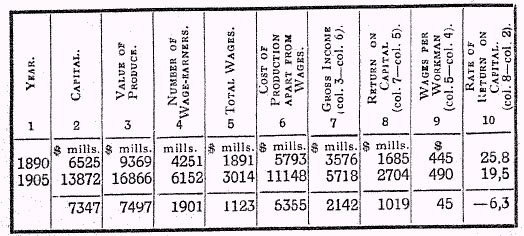

- Bernstein and the Concentration of Capital and of Industry

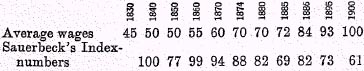

- The Poor become Poorer

- Financial Feudalism

- Real and Apparent Income

- The Distribution of Inheritances in France

- The Distribution of Landed Property in France

- Marx's Principles and Small Properties

- Limited Liability Companies

- Cartels and Trusts

BOOK V. THE DISTRIBUTION OF INDUSTRIES.

CHAPTER

- Marx's Theory and the Concentration of Industries

- The Distribution of Industries in the United States

- The Distribution of Industries in France

- The Distribution of Industries in Belgium

BOOK VI. THE INCONSISTENCIES OF SCIENTIFIC SOCIALISM.

CHAPTER

BOOK VII. COLLECTIVIST ORGANISATION.

CHAPTER

- Collective Organisation and its Economic Conditions

- The Class War and Political Conditions

- The Deflections of Administrative Organs

- The Impossibility of Collectivism

BOOK VIII. THE ACTUAL CLASS WAR.

CHAPTER

- Strikes and Trade Unions

- The Sovereignty of the Strikers

- The Nation at the Service of the Strikers

- The Electricians' Strike

- The Tyranny of Minorities

- Destruction of Property and Plant and the General Strike

- Labour Exchanges in France

- The American "Labour Unions"

- The Exploitation of Intimidation

- Compulsory Arbitration

- Conclusions

BOOK IX. SOCIALISM AND DEMOCRACY.

CHAPTER

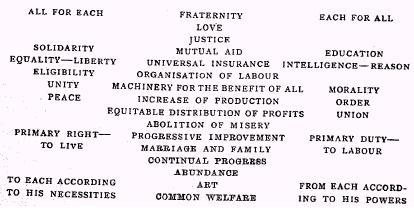

- The Programme of the International Association

- Socialism versus Democracy

- How Many Are There?

- The Havre Programme and M. Jaurès' Solutions. M. Deslinières' Provisional Laws

- Social and National Policy

- Positive and Negative Policy

- Tactics of the Social War

- Against the Law

- Depressing Effect upon Wealth

- The Impotence of Socialism

SOCIALISTIC FALLACIES

YVES GUYOT

COPE AND FENWICK

16 Clifford's Inn K.C.

PORTSMOUTH

PREFACE TO THE ENGLISH EDITION↩

I take the word "fallacy" in the sense in which it is employed by Bentham1:—"By the name of fallacy, it is common to designate any argument employed, or topic suggested, for the purpose, or with a probability, of producing the effect of deception—of causing some erroneous opinion to be entertained by any person to whose mind such argument may have been presented."

In the following pages my object has been to reduce to their true value the socialistic fallacies with which a number of able, but frequently unscrupulous, men, amuse the idle and attract the multitude. They do not even possess the merit of having originated either their arguments or their systems. They are plagiarists, with some variations, of all the communist romances inspired by Plato. Their greatest pundits, Marx and Engels, have built up their theories upon a sentence of Saint Simon and three phrases of Ricardo.2

What has become of the Utopias of Fourier and of Cabet, of Louis Blanc's organisation of labour, of Proudhon's bank of exchange, of Lassalle's question of the right to work and of the iron law of wages, and of Karl Marx' and Engels' Communistic Manifesto? As soon as you attempt a discussion with Socialists, they tell you that "the Socialism which you are criticising is not the true one." If you ask them to give you the true one, they are at a loss, thereby proving that, if they are agreed upon the destruction of capitalist society, they do not know what they would substitute for individual property, exchange and wages. In June, 1906, M. Jaurès promised to bring forward within four or five months propositions for legislation which should supply a basis for collectivist society. He takes good care not to formulate them because he foresees the risk to which he would be exposing himself, despite the incomplete development in him of a sense of the ridiculous.

No Socialist has succeeded in explaining the conditions for the production, remuneration and distribution of capital in a collectivist system. No Socialist has succeeded in determining the motives for action which individuals would obey. When pressed for an answer, they allege that human nature will have been transformed.

This introduces a difficulty; for, if I am hungry or thirsty, can someone else, in a collectivist society, give me relief? When Denys the Tyrant had a stomach-ache, he never succeeded in handing it on to a slave. Torquemada, by torturing and burning heretics and Jews, was able to prevent the expression of ideas; he never succeeded in changing one. The individual remains a constant quantity.

While leaving out of account the fact that the more the individual develops, the stronger will be the resistance he offers to every kind of repression, collectivists end in a government by police on the model of those of the Incas in Peru or the Jesuits in Paraguay.3 "The proletarian class will govern," says Karl Marx, but he does not explain how. Mr. Carl Pearson, one of the "intellectuals" of Socialism who has the courage of his convictions, recently said: "Socialists have to inculcate that spirit which would give offenders against the State short shrift and the nearest lamp-post."4 The reader will be referred hereafter to another quotation which proves that, in a slightly modified form, this is also the opinion of M. Deslinières.5

While awaiting this happy consummation, the Stuttgart Congress has reaffirmed, on August 20th, 1907, that he only can be recognised as a true Socialist who adheres to the struggle of classes. According to this conception, the wish of one class constitutes law; audacious minorities will oppress intimidated majorities, and the social war is to rage permanently. These Socialists transfer all the conceptions of a warlike civilisation to economic society; the individual who is enrolled among their troops owes passive obedience to his leaders, and the independents are enemies to be received with the classic option of "your money or your life!" Socialism is a hierarchy on a military basis, imported from Germany, as M. Charles Andler proclaims.6 When they reserve all their energies against their fellow-citizens, the supporters of the struggle of classes are logical; for it is not worth troubling to take from a neighbour who would defend himself that which will be within reach of their hands on the day when they attain to power. The French Socialists show how they will employ their power, by celebrating the anniversary of the Commune; and those of them—such as the leaders of the General Confederation of Labour—who claim to be practical, put before their levies as an ideal, a general strike, accompanied by the destruction of industrial property and plant, short circuits, explosions of gas and of dynamite, and the derailment and holding up of trains.

Mr. James Leatham, in a pamphlet entitled "The Class War,"7 says that "the Independent Labour Party is the only Socialist party in Europe, probably in the world, which does not accept, but explicitly repudiates, the principle of the class war." But the Social Democratic Federation, founded by Mr. William Hyndman, which in 1907 became the Social Democratic party, "proclaims and preaches the class war."8 The Independent Labour Party is unable to adhere to this totidem verbis. By the force of circumstances, its programme confines it to practical matters, since it admits of the power of confiscation of private property. The Labour Party, which from 1900 to 1906 was known as the Labour Representation Committee and now forms the Parliamentary Labour Party, does not dissemble as to its programme. At the eighth annual conference at Hull in January, 1908, the following resolution was endorsed by 514,000 votes to 469,000:—

That in the opinion of the Conference the time has arrived when the Labour Party should have a definite object, the socialisation of the means of production, distribution and exchange, to be controlled by a democratic state in the interests of the entire Community; and the complete emancipation of Labour from the domination of capitalism and landlordism with the establishment of social and economic equality between the sexes."

Even if a large majority be not associated with this declaration, the Labour Party has absorbed the Trade Union group in the House of Commons, which numbered twenty-one members after the General Election of 1906. The Labour Party put forward fifty candidates, of whom thirty were elected. But the Miners' Federation decided in June, 1908, by a majority on the ballot of 44,843 votes, definitely to join the Labour Party. The result of this is that at the next General Election the fifteen miners' members of the Trade Union group will have to sign the Labour Party constitution. At the end of 1908 there were remaining only three members of the Trade Union group.9

The Social Democratic Party carries the Independent Labour Party along with it: the two combined in the Labour Party carry the Trade Union group, and although the Labour Party numbers less than fifty votes in the House, it is sweeping towards Socialism the majority of 380 members of the Liberal Party elected in 1906. These latter refuse to listen to the warnings of their colleague Mr. Harold Cox, who was informed by the representative of the Preston Liberal Association that it was intended to contest his seat at the General Election.10

The programme of the Labour Party includes:— (a) The collective regulation of industry; (b) the gradual direct transference of land and industrial capital from individual to collective ownership and control; (c) absorption by the State of unearned income and unearned increment; (d) provision for needs of particular sections of the community.

The Socialists may claim with pride that the advance has already begun along each of these lines.

Since the coming into office of the present Government they have obtained the Trade Disputes Act, which formally recognises the right of picketing, that is the right to intimidate as against non-strikers, and relieves the Trade Unions of all legal responsibility with regard to their agents. A Coal Mines Bill (1909) provides that no miner shall work underground for more than eight hours a day. Using the sweating system as a pretext, they have obtained the constitution of Wages Boards, with power to fix a minimum wage. Despite the French experience of "Bourses du Travail," Mr. Winston Churchill has introduced a Bill for the establishment of Labour Exchanges which has scarcely met with any opposition. In 1908, the Old Age Pensions Act provided that as from the 1st of January, 1909, old age pensions may be claimed by all persons of 70 years or over who fulfil the statutory conditions.

Until 1906 the Liberal and Democratic party in Great Britain placed in the forefront of its programme the relief of the taxpayer by the reduction of the National Debt and the decrease of taxation. It prided itself on its sound finance. From the time when the Socialists try to make the State provide for the livelihood and the happiness of all, the Liberal Government bases its existence upon the increase of expenditure. The Budget shews a deficit. So much the better! Taxation is no longer imposed solely for the purpose of meeting expenditure incurred in the general interest. It is looked upon as an instrument for the confiscation of the rents paid to landlords and of the interest paid to holders of stocks and shares, as a means of absorption by the State of unearned income and unearned increment. The Budget for 1909-1910 introduced by Mr. Lloyd George is an application of this portion of the Socialist programme. No doubt he states that the scale of taxation proposed by him is a modest one, but he is placing the instrument in the hands of the Socialists. When they have once grasped it, they will know how to use it. Mr. Shackleton, M.P., in opening the Trade Union Congress on September 6th, 1909, referred to it as "a Budget which will rank as the greatest financial reform of modern times."

The Socialists may well be proud of their success in Great Britain. Although they number less than nine per cent. of the members of the House of Commons, they have succeeded in conferring the privilege of irresponsibility upon the Trade Unions, in laying the foundation in the Budget for the socialisation of land and of industrial capital and in converting financial legislation into an instrument for the struggle of classes. And Mr. Keir Hardie was able, on September 1st, 1909, at Ipswich, to say without covering himself with ridicule, that the present generation will see the establishment of Socialism in England! The question of the unemployed is an excellent means of agitation, and Mr. Thorne, M.P., has not hesitated to advise them to plunder the baker's shops. If his advice had been followed, where would bread have been found on the following day?

Socialistic policy can only be a policy of ruin and of misery: the question which it involves is that of free labour actuated by the motive of profit as against servile labour induced by coercion. The Socialist ideal is that of slave labour, convict labour, pauper labour and forced labour—a singular conception of the dignity of the labourer. As regards its economic results, Mr. St. Leo Strachey cites the following, among other examples, in his excellent little book, Problems and Perils of Socialism. In 1893, Mr. Shaw Lefevre, as Commissioner of Public Works, arranged to pull down a part of Millbank Prison by means of the unemployed. When these men worked with the knowledge that their pay would vary according to the work done, they did twice as much as when they knew that whether they worked or idled their pay would be 6½d. an hour.

The prospect of gain does not exercise its influence only upon the wage-earner, it reacts upon all men, financiers, employers of labour, and investors, because it admits of an immediate and certain sanction, that of gain or loss.

A private employer will make profits where the State suffers loss. While individuals make profits and save, governments are wasteful and run into debt. Statesmen and local officials are free from direct responsibility, and know that they will not go bankrupt and that the taxpayers will foot the bill.

A fakir no doubt will torture himself in order to attain to superhuman felicity. Millions of men have submitted to the cruel necessities of war and have given their lives for their family, their caste, their tribe or their country. Others have braved persecution and suffered the most atrocious tortures for their faith. It may be said that man is ready for every form of sacrifice, except one. Nowhere and at no time has man been found to labour voluntarily and constantly from a disinterested love for others. Man is only compelled to productive labour by necessity, by the fear of punishment, or by suitable remuneration.

The Socialists of to-day, like those of former times, constantly denounce the waste of competition. Competition involves losses, but biological evolution, as well as that of humanity, proves that they are largely compensated by gain. Furthermore, there is no question of abolishing competition, in Socialist conceptions; the question is merely one of the substitution of political for economic competition. If economic competition leads to waste and claims its victims, it is none the less productive. Political competition has secured enormous plunder to great conquerors such as Alexander, Cæsar, Tamerlane and Napoleon; it always destroys more wealth than it confers upon the victor.

We have seen the operation of political competition in the internal economy of States. In the Greek Republics, and in those of Rome and Florence, in which the possession of power and of wealth was combined, it was impossible for parties to co-exist; the struggle of factions could only end in the annihilation of one and the relentless triumph of the other. This is the policy represented by Socialism.

The first result is to frighten capital, and capital defines the limits of industry. If it withdraws, industry decays and activity diminishes; and no trade union, strike or artificial combination can raise wages when the supply of labour exceeds the demand.

Mr. J. St. Loe Strachey entitles one of his chapters, "The richer the State, the poorer the People." He says: "People sometimes talk as if the poor could be benefited by making the State richer." Mr. St. Loe Strachey's answer is: "There is a certain amount of wealth in any particular country. Hence, whatever you place in the hands of the State you must take away from Brown, Jones and Robinson. You do not increase the total wealth." The entire Socialist policy consists in taking away from individuals for oneself and one's friends. When this policy is practised by the highwayman in a story with a blunderbuss in his hand, it is called robbery, and the highway-man is pursued, captured, tried and hanged.

The Socialists formulate a theory of robbery and call it restitution to the disinherited. Disinherited by whom? Disinherited of what? Let them produce their title deeds! They call it expropriation, but that is a misnomer, what they set out to practice is confiscation. Under cover of the laws and in virtue of them, they get themselves elected as members of municipal bodies and legislative assemblies. In France, Belgium, Germany, Italy and the United States they seize upon the constitutional and legal means which are at the disposal of every citizen as they would take a rifle or a revolver at a gunsmith's. Once they have them in their hands they use them to put their system of spoliation into practice, this being the name given to legalised robbery. Instead of leading to the gallows, it leads to power, honours, position and wealth. The British Socialists adopt the ideal and carry out the policy of the Socialists of other countries with remarkable superiority. They rule the Liberal Party and, by annually introducing one of their postulates into legislation, gain a stage at each attempt.

In a remarkable volume published shortly before his death in 1908, entitled "English Socialism To-day," Mr. H. O. Arnold-Foster put this question: "Ought we to fight Socialism?" And he began by saying, "It is a question which it is necessary to ask." Can this be so? Is there then a number of those who desire liberty for the employment of their faculties, their energy, their capacity for work, and their capital in accordance with their wishes and in such manner as they consider most convenient to their interests, who are not convinced that they ought to defend their liberty of action against Socialist tyranny? Does a number of those who wish to reap the benefit of their labour, their efforts and of the risks they have incurred admit that the Socialists have a right to deprive them of it? How can people entertain doubts as to their right to work and their right to own property? They have suffered themselves to be hypnotised by Socialistic fallacies and verbiage until they are ready to obey injunctions which will forbid them to act without the sanction of the Socialist authority, and command them to surrender to that authority their property, their inheritances, their savings and the capital which they have acquired.

Mr. Arnold-Foster replies, "It is necessary that we should fight Socialism," and we should do so not only from the point of view of our material interests, but also from that of politics and of morals. The triumph of Socialism would involve a step backward: for the competition of parties existing side by side, it would substitute the social war; it would arrest the evolutionary process which substitutes contract for statute, as set forth by Sir Henry Maine, and it would subordinate all actions to the dispositions of authority.11 The result would be a reign of slavery among the ruins.

There are people who resign themselves to the Socialist invasion, as some Romans in the period of the decline of the Empire resigned themselves to those of the barbarians. They say that the Socialists, being the more numerous (which is not the fact) and the stronger (which is open to doubt) are possessed of the enthusiasm of conquerors and must prevail. Wise and prudent folks therefore prepare to accommodate themselves to their tyranny, and are ready to pay court to them. They are already seeking to conciliate the Socialist leaders, salute them politely, and assure them of their readiness to make every sacrifice to carry a sound Socialism into effect. By such cowardice they think that they are taking good security for their own advantage. When their backs are turned they wink their eyes and nod their heads, as much as to say : "See what sly fellows we are. The Socialists think that they are conquering us, whereas it is we who are the conquerors. The best way to annihilate them is to give in to them."

This haphazard policy was followed by a man with a reputation for vigour and perspicacity. Bismarck attempted to switch off Marxist Socialism into a bureaucratic Socialism—result, 3,200,000 Socialist votes in the elections to the Reichstag in 1907!

All those who make concessions to the Socialists weaken themselves for the Socialists' advantage. The Socialists cannot form a portion of a government majority because, their programme being one of conflict and of pillage, they impose it as a condition of their co-operation, while the essential attribute of the State is the maintenance for all of internal and external security.

It has been said that a Socialist minister is not a minister who is a Socialist. How indeed could he be? As minister of justice, instead of protecting property and persons, he would have to recognise no right other than the pretensions of the "class" which he represents; as minister of finance, he would have to proclaim the bankruptcy of the State, a simple and practical means of nationalising debt and abolishing investors. A party, the primary obligation of whose representatives on attaining to power is to disown their programme, can destroy, but can construct nothing. They do not strengthen the administration to which they are admitted, but they are forthwith excommunicated by the Socialist party. We have seen instances in the case of M.M. Millerand, Briand and Viviani.

Even in England the Labour Representation Committee refused to continue to pay Mr. John Burns the allowance paid to Labour Members of Parliament, more than a year before he attained to office. Inasmuch as members of the House of Commons are unpaid, the committee wanted to force him to accept assistance from the Liberal party in order that they might be able to denounce him as a Liberal hack.12 In opening the Stuttgart Congress, Herr Bebel observed that the inclusion of John Burns in the British Cabinet had not modified the fighting tactics of the Labour Party.

It is a mistake to temporise with Socialist fallacies; it is necessary to expose their falsity and their consequences instead of humbly saying to those who propagate them, "Perhaps you are right, only possibly you are going rather far."

M. Léon Say has repeatedly said that to refuse to give battle for fear of being beaten is to accept defeat. In France, governments and majorities in the Chamber of Deputies have acquired the habit of yielding to the commands of the General Confederation of Labour and to the threats of strikers. It will be seen hereafter13 that this weak policy has reduced the policy of violence to a system. At the time of writing, the masons are demanding kennels at the Labour Exchange for the dogs that are trained to track and hunt down non-strikers!

I trust that the failure of the general strike in Sweden, where the Labour Party claims to be the best organised in the world,14 will have the effect of reassuring the faint-hearted. The leaders of the Labour Federation ordered a general strike for the morning of August 4th, 1909, and their order was obeyed with docility by 250,000 workmen. The butchers, grocers and bakers found themselves without clerks or workmen. If the railway employees refused to run the risk of losing their pensions by breaking their contracts of labour, the tramway employees, who were bound by a collective contract, did not hesitate to tear it up. The "Social Demokrat" attempted to prove that they were entitled, and that it was their duty, to do so under conditions which created a case of moral force majeure. M. Jaurès on being consulted replied, according to M. Branting, the leader of the Swedish Socialists, that it was the undoubted duty of the workmen to keep their engagements, but that "this obligation could not deprive them of their legitimate means of defence."15 This line of argument, borrowed from Escobar,16 did not captivate public opinion. Various groups were organised for purposes of defence. Noblemen, bourgeois, officers, students and clerks went to work as they would have done in the case of a besieged city; there was no lack of food, the roads were swept, the hospitals kept open and order secured against the efforts of the strikers by the public security brigade. The Labour Federation had expected to turn over society like an omelette. It encountered a formidable resistance. The population of Sweden numbers 5,377,000. The 250,000 strikers who had declared war upon their fellow citizens learned that this majority had no intention of submitting to their good pleasure.

The government refused the part of mediator which some counsellors, full of good intentions, but wanting in perspicacity, advised them to assume. It did not tell the nation at large that it ought to give way, or advise the strikers not to be too exacting. It contented itself with its proper part—that of maintaining order.

The lesson is complete. M. G. Sorel, the doctrinaire member of the French General Confederation of Labour, without indulging in any illusions as to the possibility of a general strike, advised the Socialists to employ it as a myth, destined to seduce the ignorant and credulous masses. In order that they might continue to exploit it, they should have kept it alive in people's imaginations, and should not have attempted to introduce it into real life. The bogey became ridiculous when its inventors tried to materalise it. They have had an opportunity of seeing that the bourgeoisie does not allow itself to be plundered as easily as they imagined.17

Economic ignorance is a far more powerful factor in Socialism than cowardice. "It is much about the same from top to bottom of the social ladder," said M. Louis Strauss recently, the distinguished president of the Belgian Conseil Supérieur du Commerce et de l'Industrie. By reason of this ignorance a number of grown-up children, who fancy themselves to be mature citizens, believe that the State can fix wages and the hours of labour, turn the employer out of his undertaking and replace him by inspectors, and secure markets for commodities, while raising their net cost according to the whims of parliamentary majorities.

In this book I have set forth economic facts which everyone is in a position to verify for himself. It is a manual for the use of all who are desirous of calling themselves familiar with the question, including Socialists who hold their opinions in good faith.

September, 1909.

1 "The Book of Fallacies." Introduction. Sect. I.

2 See infra, Book III., chap. 3.

3 See infra, Book I., chaps. ii. and v.

4 Carl Pearson, "Ethics of Free Thought," p. 324 (quoted by Robert Flint, "Socialism," p. 334).

5 See infra, Book IX., chap. iv. M. Deslinières is the author of the Code Socialiste.

6 Communist Manifesto, vol. ii., p. 178.

7 1907.

8 "The Social Democratic Federation: its objects, its principles, and its works," 1907.

9 "The Reformer's Year Book," 1909, p. 27.

10 See the article by Mr. Cox ("Socialism in the House of Commons") in the "Edinburgh Review" for 1907.

11 Yves Guyot. "La Démocratie individualiste." Sir Henry Maine, "Ancient Law."

12 "The Star," February 10th, 1905.

13 Infra, Book VIII.

14 Lindley, The Trade Union Congress.

15 "The Times," September 1st, 1909.

16 A Spanish casuist who advanced the proposition that "good intentions justify crimes."

17 See infra, Book VIII., chap. ix.

BOOK I. UTOPIAS AND COMMUNISTIC EXPERIMENTS

CHAPTER I

PLATO'S ROMANCE↩

Politico-economic romances—Common features—Government by the wisest: abolition of private interest—Castes—Plato and the warrior caste—Conception realised by the Mamelukes in Egypt—Police—Xenophon — Plotinus — Monasteries, their principles: separation of the sexes, contributions of the faithful.

VON KIRCHENHEIM, in his book "Die ewige Utopie," has traced the history of politico-economic romances after Sudre, Reybaud, Moll and others. These works all present a family likeness and are founded on the ancient conception of a golden age, an Eden, an ideal existing in a far distant past—a conception which survives in such writers as Karl Marx, Engels and Paul Lafargue, who would have all the ills of humanity date from the moment when the communism of primitive societies came to an end. All these conceptions seek to confer the governing power upon the wisest: Plato gives it to the philosophers, and the same idea reappears in Auguste Comte. They are all founded upon the suppression of private interest as the motive of human actions, and the substitution of altruism (to use the word coined by Auguste Comte), to attain which their authors abolish private property, and those among them who are logical set up the community of women.

Nearly all these writers constitute castes. Plato proclaims the necessity of slavery and declares that the occupations of a shoemaker and a blacksmith degrade those who follow them. Labourers, artisans, and traders form a caste whose duty it is to produce for warriors and philosophers and to obey them. In the "Republic" the caste of warriors only possesses property collectively, the abolition of private property being in Plato's opinion the best means of preventing the abuse of power. The annual unions between men and women are to be decided by lot, controlled by expert magistrates, careful to ensure the most favourable conditions for the reproduction of the species, the army being treated like a stud.

We saw a caste organisation of this kind for three centuries in Egypt, a college of Ulemas and a corps of Mamelukes recruited from among children with no family ties, all exploiting the miserable fellahs until they were completely exhausted.

In his "Laws," in which he attempts to work out his conception in detail, Plato fixes the number of citizens at 5,040, each with a share in the public lands, the equal produce of which is sufficient to support one family. These lands are indivisible and inalienable, and are transmitted by hereditary succession to the son who is appointed to receive them. The State is divided, in honour of the twelve months of the year, into twelve districts, in which numerous officials, as well as the councils, reside. The police enter into the minutest details of the life of every individual; until the age of forty travelling is forbidden. The police must see to it that the number of citizens shall neither increase nor diminish. The industrial occupations are followed by slaves controlled by a class of free labourers without political rights; commerce is left to strangers. A citizen of the Platonic city may not possess precious metals or lend out money at interest. Moreover, if Plato, in order to put his conceptions of the State into practice, reverts to individual property, he continues to proclaim that "the community of women and children and of property in which the private and the individual is altogether banished from life"1 is the highest form of the State and of virtue.

Plato's speculations exercised no influence upon the legislation and the politics of antiquity.

Xenophon, on the contrary, set forth the conception of an ideal monarchy in the Cyropaedia, everything being conceived upon a utilitarian basis.

Three centuries after Christ, Plotinus, who was ashamed of having a body, and desired to free the divine element which was in him, dreamed of founding in Campania a State upon the model conceived by Plato—this desire remained in the region of dreams.

Communism was only carried out in monasteries, whose existence was based upon the two principles of separation of the sexes and contributions of the faithful.

(1) Plato, Laws v. 739 (Jowett's translation).

CHAPTER II

THE KINGDOM OF THE INCAS↩

The Incas, children and priests of the sun—A military theocracy.—Administrative organisation—Police—Marriage—Common labour—The Kingdom in dissolution after the landing of Pizarro.

IN South America an organisation existed for several centuries to which true Socialists still point as an ideal. In the sixteenth century Garcilaso de la Vega, a Spaniard, wrote a history of the Incas, so full of admiration for them that he made their power extend back for thousands of years, whereas at the time of the landing of the Spaniards their empire only dated back for five hundred years. They are looked upon as a clan of the race of Aymara,1 which has left the great ruins of Tiahuanaco on the shores of Lake Titicaca.2 They created the legend of Inti, the sun-god, who, out of pity for the savage denizens of the mountains of Peru sent them his son Manco Capak and his sister and wife, Mama Ocllo. These taught men to build houses and women and girls to weave. At first their power did not extend beyond the kingdom of Cuzco, confined within narrow limits. The fourth of the Inca kings, Maita Capak, was the conqueror of Alcaziva, a descendant of the vassal-chiefs of Cuzco. His three successors extended their dominions by conquest. They constituted a warrior caste with the combatants from the conquered peoples whom they dispossessed, and in order to employ it their successors added to their conquests. They did not fall upon their enemies: they demanded their submission, and frequently on obtaining it they made a vassal of a conquered chief. They secured their authority by means of garrisons, and established large victualling depots for their soldiers. The rule of the Incas was not preserved from trouble; in spite of all their efforts their power met with resistance and provoked revolt.

One of its characteristics was that it was a military theocracy. The Inca, son and priest of the sun, was the absolute master of person and of property, of act and of will. He was the sole holder of property, but he had divided the soil into three portions between sun, Inca and subjects. He was also the sole owner of the flocks of llamas. Officials collected the wool and distributed it among those who were charged with stapling it; they slaughtered sufficient llamas to support the Inca. The mines of gold and silver were developed for the benefit of the Inca, but, inasmuch as there was no commerce, the precious metals were used only for ornament.

There were no taxes, the entire labour of each individual being due to the State. A piece of land was allotted to each family, which consisted of ten persons. The original portion was increased by one half at the birth of each son and by a quarter at the birth of a daughter. It constituted the administrative unit, and an official was told off for the purpose of taking care of it and of supervision. Ten families formed a group of one hundred occupiers and of ten officials under the supervision of a chief. Next came ten times a hundred families and ten times a hundred officials, and ten thousand families, with a like number of officials, constituted a province. The governors of a province, who were, as far as possible, members of the family of the Incas, and the principal overseers of the smaller groups were bound to appear at the court of the Inca from time to time and to transmit reports regularly. They were under the constant supervision of inspectors, and when a family was in default, it was punished, as were also its overseers of different degrees who had failed to exact its obedience.

Everyone, both male and female, was compelled to work. At the age of twenty-five it became the duty of the young Peruvian to marry, a day in each year being consecrated to this ceremony. The officials pointed out to each youth the maiden whom they decided to bestow upon him; a piece of land with a house was allotted to them, and when the province was already too populous, they were sent to new territories. The young men were liable to military service, while a number of young girls were selected to work in monasteries in which they were bound over to chastity under penalty of death. The lands of the sun and of the Inca were cultivated in common as State lands. The overseers conducted those over whom they had jurisdiction to labour as though to a festival, but they first flogged and afterwards hanged them if they refused to perform their share of the work. The same punishment was inflicted upon anyone who ventured to cease work without permission; old men and children were obliged to supply their contingent. Yet the Incas made no attempt to introduce this system in all the provinces which they had conquered.

The Spaniards landed in America during the period when Huacna Capak was occupied in reducing Quito, where he forgot his wife and his son Thrascar and violated the law of the Incas by taking to wife a woman who was not of their race. By her he had a son, Atahualpa, who became his favourite, and to whom he bequeathed the Kingdom of Quito, the Kingdom of Cuzco falling to Thrascar. A quarrel broke out: Atahualpa descended upon Cuzco with his warriors, gained a victory and put the Incas to the sword. When Pizarro landed in Peru he found the country in a state of anarchy, which explains the ease with which he succeeded.

1 In my book, "La Propriété," I reproduced the hypothesis that the Incas were of an alien race.

2 "The World's History," edited by Dr. H. F. Helmolt. Vol. i. The Prehistoric World: America, p. 315.

CHAPTER III

SIR THOMAS MORE'S "UTOPIA" AND ITS APPLICATIONS↩

- Sir Thomas More—Sources of his Utopia—its symmetry—Propaganda by university and clergy.

- Influence of More's book upon Thomas Munzer—Rising of Mulhouse.

- The Anabaptists—Mathias—John of Leyden—Common characteristics—Absolute supremacy of a prophet and of the mob—Internal dissensions.

I.

THOMAS MORE, Chancellor of England, published his Utopia at Louvain in 1516. The book consists of a critical part dealing with the government of England and contemporary politics, and of a part setting forth the organisation of a communistic society. More was familiar with the humanists from whom he drew his inspiration as well as with the travels of Columbus, of Peter Martyr and of Amerigo Vespucci. Columbus had spoken of peoples who held everything in common, living under the unlimited authority of a cacique, who spoke in the name of a divinity. Amerigo Vespucci had seen peoples living in a more or less anarchical state of communism, huddled in large barns containing some hundreds of persons.

More proceeded to trace the ideal of what Paul Lafargue calls the return of communism. There are too many poor people in Europe. To abolish property is to abolish the difference between poor and rich. The Utopians conclude that this will be for the benefit of the poor. The inference does not follow, for the abolition of property cannot be a factor in the accumulation of wealth.

More sets out in his comfortable fashion the geography of the Isle of Utopia. He places therein fifty-four cities, all built upon the same plan and with identical institutions; a territory of not less than twenty miles square in extent, the duty of cultivating which is apportioned between a certain number of families, is attached to each town: each family consists of no fewer than forty men and women and of two bondmen. Every year twenty citizens who have spent two years in cultivating the land return to the town and are replaced by twenty others. All the inhabitants of Utopia, both men and women, labour, but only for six hours a day. They have few wants, their clothing is made of leather and skins which will last for seven years. Their meals are taken in common, the women being seated opposite to the men. Travelling is rendered almost impossible. Every town is to contain six thousand families: when a particular family is too rich in children, it bestows some of them upon those which have not enough. Marriage is surrounded with formalities; the community of women is unknown, and adultery involves slavery.

The form of government consists of a prince elected for life and of a body of magistrates and officers elected for one year. The Utopians are men of peace, but they make war at need and employ mercenaries to carry it on. Religious liberty is established, but whosoever does not believe in the existence of Providence and in the immortality of the soul is incapable of receiving employment.

These visions have been translated, re-edited and propagated. When I was seven years old, just after the revolution of 1848, I was given as a prize a book approved by the Archbishop of Tours, a Life of Sir Thomas More, with the description of Utopia in an appendix. Yet the university and clergy who circulated this work must have known that it had translated itself into acts of fury within a very few years of its publication.

II.

In 1525 Thomas Münzer, a Protestant pastor in Saxony, at the suggestion of his master, Storch, who was inspired by the Bible and by More, attempted to put the "Utopia" into practice. After having attempted to cause a rising in Suabia, Franconia and Alsace, he succeeded in driving out the town council of Mühlhausen and in installing himself in the Johannisterhof on March 17th, 1525. The rich were commanded to feed and clothe the poor and to provide them with seeds and with land upon which they might work: the majority of them fled, as is usual with them at times of crisis. Thomas Münzer spoke as a prophet and dealt out justice with the freedom of a delegate of Heaven. He sought to raise the miners of the Erzgebirge by telling them to rise and fight the battle of the Lord. "If you do not slay, you will be slain. It is impossible to speak to you of God so long as a noble or a priest remains upon earth." Münzer sallied forth from Mühlhausen at the head of a kind of army. He mounted a black charger and was preceded by a white banner, upon which shone a rainbow. His bands laid waste and massacred throughout their career: after an initial defeat at Fulda, they were destroyed at a place which has since been known as the Schlachtberg (Battle Mountain), despite the invocations of Münzer to the Lord. Münzer himself was taken, tortured and beheaded.

III.

Münzer left behind him Anabaptists, who scattered themselves over Switzerland, Moravia, the Low Countries, and North-West Germany. A baker of Haarlem, called Mathias, in a book entitled "La Restauration," declared that every human individual must be regenerated by means of a new baptism, that princes, taxes and the administration of justice must be suppressed, and polygamy and the community of goods established. The Anabaptists inaugurated their rule at Munster on February 1st, 1534. They commenced by demolishing the church towers, for greatness must be laid low, and in burning the holy images. They commanded everyone under pain of death to come and deposit their money and articles of value at a given house. The doors of the houses were to be left open day and night, but they might be protected by a small railing in order to preserve them from invasion by the pigs which swarmed in the streets.

Mathias having been killed in an attack upon the troops of the Duke of Gueldres, a former inn-keeper of Leyden, known as John of Leyden, affirmed that his death was a sign of the grace conferred by God upon his prophet, claimed to be inspired by the Bible, entered into communion with the Spirit of God, and in the first instance nominated twelve judges of the people, following the example of the judges of Israel; but on encountering some opposition among them he declared that God in a fresh revelation had commanded him to assume absolute power and to become the king of the New Zion. A comrade called Tuschocheirer, perhaps in good faith, declared that God Himself had confirmed to him His command given to John of Leyden to ascend the throne of David, to draw the holy sword against kings, to extend His kingdom throughout the world, giving bread to those who submitted and death to those who resisted. In order to contend with the kings he anointed himself as King of the New Zion, arrayed himself in a robe made out of the silver embroideries of the churches, and a coat picked out with pieces of purple and decorated with shoulder knots of gold, put on a golden crown and a cap studded with precious stones, and displayed upon his breast a magnificent chain supporting a symbolic globe which bore the inscription, "King of justice on earth." He never appeared without an escort with richly-caparisoned horses, and installed himself on a throne set up in the public square, where he combined the functions of legislator and of judge.

He married fifteen wives. For had not Solomon many wives? And is not the first commandment of God crescite et multiplicamini? How could a monogamist observe this commandment during the pregnancy of his wife? Upon one of his wives failing in respect, he tried, condemned and executed her himself, and danced before her corpse with his other wives in imitation of David, while the rabble followed suit to the cry of "Gloria in excelsis!"

The Anabaptists were defeated and massacred at Amsterdam: Famine raged at Munster; on June 25th, 1535, the troops of the Bishop of Munster entered the town and the orgies of the Anabaptists were succeeded by those of the forces of order. John of Leyden was put to the torture, exhibited in an iron cage, which may still be seen, and was finally executed on January 22nd, 1536. At the end of ten years the Anabaptists, who had proposed to conquer the world, were crushed, massacred and scattered abroad. These communists had found at Mühlhausen and at Munster but one form of government—the absolute rule of a prophet and under him nothing but a mob and a rabble.

After their fall the Anabaptists founded communities in Moravia in true monastic form, although marriage was permitted. They were obliged to labour even on Sundays, and to preserve perpetual silence. These people, surrounded as they were by enemies, found occasion to dispute among themselves: they excommunicated one another, and when they were not disputing they gave way to intoxication, all of them striving to escape from the terrible oppression resulting from their communism.1

1 F. Catron, "Histoire du fanatisme des réligions protestantes, et de l'Anabaptisme"—Henri Olten, "Le Tumulte des Anabaptistes"—Guy de Bres, "La Racine, source et fondement des Anabaptistes."

CHAPTER IV

ANDREÆ AND CAMPANELLA↩

I

- Andreæ and the Universal Christian Republic.

- Campanella, the Dominican, and the Civitas Solis—Powers and duties of ministers—The minister of eugenics—A convent with sexual promiscuity.

JEAN VALENTIN ANDREÆ, a Protestant pastor, published in 1620 a "Description of the Universal Christian Republic," in which he re-models More's "Utopia" from the Protestant point of view. The authority of government is in the hands of a pontiff, a judge and a minister of science. He reasserts in all the appropriate accents the return to God and the absorption in the grace of Christ.

In the same year a Dominican born in Calabria who, being accused of conspiring against Spanish sovereignty and of other crimes, had passed more than twenty-five years in the prisons of Naples, and had three times suffered torture, published the "Civitas Solis." In this work the government is entrusted to a prince-priest named Hob, with three ministers under him: Pan, Sin and Mor, charged respectively with war, with science, and with everything that concerns generation and the maintenance of life. Von Kirchenheim remarks with astonishment that these are the first ministers of special departments known in the history of politics.

II

Campanella boldly accepts communism—living in common and community of women and of children. The minister Mor, with the assistance of subordinates of either sex, selects the parties to every marriage, and after taking the opinions of astrologers, directs the day and the hour at which they are to procreate their offspring. From the time when they are weaned, children are brought up in common. Campanella has them instructed in a particular manner. The work of adults is reduced to four hours a day and is directed by officials with the right to inflict punishment. Jurisdiction is solely of a criminal nature, as there cannot be civil disputes. Once a year everyone must confess. Meals are taken in common, the use of wine being forbidden.

Campanella commenced by putting forward the feelings of honour and of duty as sufficient motives for right conduct; he ends with penal sanctions. His conception of society is that of a monastic institution which permits of sexual promiscuity.

In his "De Monarchia Hispanica" he sets out a scheme of universal monarchy under the suzerainty of the Pope, supported by the military power of Spain. All the peoples of Europe will be one, heretics will be exterminated, peace will prevail on earth and the community of property will entirely suppress poverty.

CHAPTER V

PARAGUAY↩

Paraguay—Jesuit recruiting—Absence of civil and criminal legislation—Private property—Religious worship—Common meals—Clothes and lodging—Corregidors as police—Confusion of moral and civil order—Absence of commerce—Misery and idleness.

AT the time when Campanella's book appeared, the Jesuits were putting its principles into practice in Paraguay. They had obtained certain privileges from Philip III., but Diego Martin Neyroni, the Governor of the Spanish possessions from 1601 to 1615, drove them back into the countries of Guaycuru and Guarani, where they succeeded in becoming independent of the Spanish viceroys and in refusing to tolerate the presence of any Spaniard. They found there a population accommodating enough to submit to a discipline under which a few hundred Jesuits were enabled to govern a territory extending from the Andes to the Portuguese possessions in Brazil, comprising the valley of Paraguay and part of the valleys of Parana and of Uruguay, and covering an area of four or five times the size of France.

In addition to their central establishment they had thirty-one others, which they called "Reductions."

According to Alexander von Humboldt, the Jesuits proceeded to the conquest of souls by flinging themselves upon the tribe they selected, setting fire to their huts and taking away as prisoners men, women and children. They then distributed them among their missions, taking care to separate them in order to prevent them from combining.1 These prisoners were slaves, of whom the house of Cordova possessed three thousand five hundred at the time of the suppression of the Order.

Conversions were effected with great despatch by touching the converts with damp linen. The baptism being then complete, they sent the certificates to Rome. Each tribe had two rulers, a senior who was concerned with the temporal administration, and a vicar who carried out the spiritual functions.2

They did not establish any system of municipal laws, for which there was no necessity, either to regulate the condition of families (for there was no right of succession and all children were supported at the charges of the Society) or to determine the nature and the division of property, all of which was held in common. Neither was there any criminal legislation, the Jesuit fathers correcting the Indians under no rules other than their own wills, tempered by custom.

Although labour in common was the rule, the Jesuits were obliged to make some concession to the desire for private property and to the need for personal service. They therefore granted a small piece of land to each family with liberty to cultivate it on two days in each week. They also gave occasional permission to the men to go hunting or fishing on condition of their making the heads of the mission presents of game or of fish.

Two hours of every day were set apart for prayers and seven for work, except on Sundays, when prayers occupied four or five hours. Every morning before daybreak the entire population, including infants who were hardly weaned, assembled at church for hymns and prayers, and the roll was called, after which everyone kissed the hands of the missionary. Some were then taken by native chiefs to labour in the fields and others to the workshops. The women had to roast sufficient corn for the needs of the day and to spin an ounce of cotton.

Every morning during mass broth was made of barley meal, without fat or salt, in large cauldrons placed in the middle of the public square. Rations were taken to the dwellers in each hut in vessels made of bark, and the scrapings were divided among the children who had acquitted themselves best in their catechism. At midday more broth was distributed, a little thicker than that which was supplied in the morning, containing a mixture of flour, maize, peas and beans. The Indians then resumed their work, and on their return kissed the hand of the priest and received a further ration of broth similar to that of which they had partaken in the morning. Although cattle were plentiful, according to some accounts, meat was only distributed in exceptional cases or to men who were at work; according to others it was distributed daily. Probably each "Reduction" followed its own particular system according to the amount of its resources. Salt was scarce, a small bowl being served out to each family on Sundays.

Regulations fixed the amount of cloth, which was given annually, to men at six "varas" (five yards) and to women at five "varas." This they made into a kind of shirt which covered them very indifferently. They had neither drawers, shoes, nor hats. Children of either sex went naked until they attained the age of nine.

Their huts, which were very small and low, were round. The framework consisted of posts driven into the ground and joined at the tops, trusses of straw being spread upon them to protect the inside. The inhabitants were crowded into them to the number of fifteen for each hut, of which an accumulation formed a town. There were no dwellers in the open country, owing to the difficulties of supervision. In the centre of a town stood the church, and beside it were the college of the fathers, the stores and the workshops. The streets were regularly laid out and planted with trees, and each town was encircled by an impenetrable hedge of cactus. The church was built with the sham elaboration and filled with the tinsel which are the characteristics of Jesuit art. Music was performed in them, choirs organised, and religious exercises practised, among which self-flagellations, to which women and girls submitted themselves, crowns of thorns, and positions representing crucifixions were to strike the imaginations of the natives.

The Jesuits selected from among their own members corregidors to watch over conduct, to supervise the regular performance of the religious ceremonies and to direct and control labour. These held office for two years. A native was never elevated to the dignity of a priest. The Jesuits solemnised marriages twice a year, but the community of goods had a sinister influence in encouraging the community of women.

The fathers were the guardians of virtue as of everything else. Of their manner of exercising their functions I will only quote from Bougainville, who was at Buenos Ayres at the time of the expulsion of the Jesuits, this passage: "My pen refuses to record the details of what the people allege. The passions aroused are still too recent to allow of the possibility of distinguishing the false charges from the true."3 Clearly it was not respect for the native women and girls that could restrain the fathers, and we perceive once again the danger of confounding moral order with that which is imposed by legal institutions. The former had put an end to the latter, and there was no security either for person or for property. Every Jesuit was at one and the same time confessor, legislator and judge, and if he despised the office of executioner he nevertheless superintended the process of execution.

The Jesuits converted every Indian into an informer at the moment when he made confession, and when one of those whose confession had previously been made approached him, the Jesuit found no difficulty in convicting him. Punishments were not of a spiritual nature; they consisted of lashes with leather thongs inflicted upon men in public and upon women in secret, a father or a husband being frequently charged with the office of executioner, the culprit being finally constrained to kiss the hand of the father who had caused him to be chastised. Offences were of two kinds, offences against doctrine, failure to attend a religious ceremony and the like, and offences against economic obligations, such as negligence in work or even losing seed or cattle, which the fathers would replace without objection, but with the addition of a thorough whipping.

Commerce was prohibited and money unknown. There was no trade except with the foreigner, and this was undertaken solely by the Jesuits. It is estimated that they were able to collect from one to two millions of écus annually, of which one half was remitted to the General of the Order. Naturally the natives had no share in it.

The natives were not allowed the use of horses for fear lest they should depart from their settlements; they were not permitted to go beyond fixed bounds, on pain of the lash if they disobeyed. They worked very badly and very little. Antonio de Ulloa4 says that seventy labourers were required where eight or ten Europeans of moderate capacity would have sufficed. They lived in a state of wretched and abject inertia. One fact alone proves their condition of stagnation. Although a bell called them nightly to the performance of their conjugal duties, the population failed to increase.5 When the Jesuits were expelled in 1768, they left a population in a miserable condition such as Bougainville and La Perouse have described. Such was the result of putting into practice the principles of Campanella's "Civitas Solis."

1 "Voyage aux régions Equinoxales," vol. vi., book vii., ch. 19.

2 Charles Comte, "Traite de la Législation," vol. iv., p. 464.

3 Bougainville, vol. i., pp. 196-197.

4 Cited by Charles Comte.

5 See Pfotenhauer, "Die Missionen der Jesuiten in Paraguay," 3 vols., 1891-1893.

CHAPTER VI

MORELLY AND THE "CODE DE LA NATURE"↩

The "Basiliad"—Sexual Morality—Principles of the "Code de la Nature"—Their application: Babeuf and Darthé—Property and the Revolution.

IN 1753 Morelly, an author of whom few details are known, published two volumes in duodecimo, entitled "An Heroic Poem," translated from the Indian, and "Wreck of the Floating Isles, or Basiliad of the Celebrated Pilpaï." I confess that I have not read them. Villegardelle has published extracts from them at the end of an edition of the "Code de la Nature," which were quite enough for me. But, judging by the passages cited by Von Kirchenheim, Morelly exhibits himself even more boldly in his prose poem as regards sexual morality than would appear in the pages of Villegardelle. "They knew not the infamous names of incest, adultery and prostitution: these peoples had no conception of these crimes: a sister received the tender embraces of a brother without any feeling of horror…." From the moment when these acts ceased to be denominated by ugly words all was for the best.

The "Code de la Nature" appeared in 1754, a year after Rousseau's essay, "L'Origine de l'inegalité parmi les hommes." The author starts with the same idea, "The earth belongs to no man." He sets up a model of legislation "in conformity with the designs of nature." His inspiration is derived from Moore and Campanella and he is entitled to be considered as having inspired all the communists and collectivists who have succeeded him, including our contemporaries. The essential conditions of his system are as follows:—

Essential unity of property and of living in common: establishing the common use of instruments of labour and of products: rendering education equally accessible to all: distribution of work according to capacity and of its produce according to needs: preservation round the city of land sufficient for those who dwell in it.

Association of at least one thousand persons in order that, while every one works in accordance with his power and capacity, and consumes according to his needs and his tastes, there may be set up for a sufficient number of individuals an average of consumption which does not exceed the common resources, and a total resultant of work which supplies them in sufficient abundance.

No privilege to be accorded to talent other than that of directing labour in the common interest and no regard to be had, in dividing the proceeds of labour, to capacity, but only to needs, which exist before capacity and survive it.

Pecuniary rewards to be excluded; first, because capital is an instrument of labour which must remain wholly at the disposal of those who administer it, and secondly because every grant in money is useless where labour, being freely and willingly adopted, would render the variety and abundance of its produce more extended than our wants, and injurious where inclination and taste failed to fulfil all useful functions, for this would be to enable individuals to avoid payment of the debt of labour and of obtaining exemption from the duties of society without renouncing the privileges which society ensures.

Morelly has codified this system, and I reproduce certain provisions of his code which it is desirable to compare with actual conceptions.

TITLE II.

ART. 5. Calculated upon tens, hundreds, etc., of citizens, there shall be for each calling a number of workmen in proportion to the degree of difficulty involved by their labour, and to the amount of its produce which it is necessary to supply to the people of each city without unduly exhausting the workmen.

ART. 6. In order to regulate the distribution of the products of nature and of art, it is necessary to recognise, in the first place, that these include articles of a durable nature, i.e., such as can, at all events, be preserved for a considerable time, and that all products of this nature include:—(1) daily and universal use; (2) use which, though universal, is not continuous; (3) some that are continuously necessary to some one person only, but occasionally to everyone; (4) others that are never for continuous or general use, such as articles produced for isolated gratification or for a particular taste. Now, all these products of a durable nature are to be collected in public store-houses in order that they may be distributed, some daily or at fixed times to all the citizens to serve for the ordinary necessities of life, and as material for the labours of different occupations; others to be supplied to such persons as use them.

ART. 11. Nothing is to be sold or exchanged between fellow citizens, so that a man who has need of particular herbs, vegetables, or fruit is to go and take what he requires for one day's use only in the public place to which these things have been brought by those who grow them. If a man has need of bread, he is to go and provide himself for a stated time from the man who makes it, who will find in the public granary sufficient flour for the quantity of bread which he has to bake, be it for one day or for several.

ART. 10. The surplus provisions of each city or province are to overflow into those which are in danger of falling short, or are to be preserved for future necessities.

TITLE III.

ART. 3. Every citizen, without exception, between the ages of twenty and twenty-five is to be compelled to follow the pursuit of agriculture unless relieved by reason of some infirmity.

TITLE IV.

ART.1. In every occupation the oldest and the most experienced are to take turns, according to seniority, and for five days at a time, in directing five or six of their companions, and are to fix the scale of work to be performed by them, moderately, on the basis of the amount which has been imposed upon themselves.

ART. 2. In every occupation there is to be one master for ten or twenty workmen.

ART. 7. The heads of every occupation are to appoint the hours of rest and of labour, and to prescribe what is to be done.

TITLE VI.

ART. 1. Every citizen of the age of thirty shall be clothed according to his taste, but without exceptional luxury, and similarly is to take his meals in the bosom of his family, without intemperance or profusion; this law enjoins senators and chiefs severely to repress those who exceed.

Babeuf drew his inspiration from Morelly. The manifesto of the "Conspiration des Egaux," written by Sylvani Maréchal, explains the difference between their conception and that of an agrarian law which permits the division of property. "Agrarian laws or a division of lands arose from the sudden desire of a body of unprincipled soldiers, or of a people united by their instinct rather than by their reason. We aspire to something more sublime and more equitable—the common good in a community of goods." No more private property in lands, "The land belongs to no one; we claim, we want the communal enjoyment of the fruits of the earth." The law of the 27th Germinal of the year IV. (April 16th, 1796), which punished with death "all who incite to pillage, or to the division of private property under the name of an agrarian law or in any other manner whatsoever," was applied to Babeuf and Darthé.

The Declaration of the Rights of Man of 1793 had asserted, with even greater energy than the Declaration of 1791, the right of property, which it defined in Article 16 as that which belongs to every citizen to enjoy, and to dispose at will of his income, the fruits of his labour and of his industry.

CHAPTER VII

ROBERT OWEN AND "NEW HARMONY"↩

- Robert Owen—His theories—Organisation of reflex action—Moral punishments—The right to direct—Used machinery and desired to return to the spade.

- The experiment of "New Harmony"—Its constitution —Anarchy—The dream survives the experiment.

I

M. EDWARD DOLLEANS, Professor of Political Economy in the University of Lille, has published an interesting and learned volume on Robert Owen. Robert Owen lived from 1771 to 1858. The son of a village labourer, he passed as an apprentice through various trades and businesses, and was selected at the age of twenty to direct the important fine thread manufactory of Messrs. Drinkwater, at Manchester. He developed this, and after leaving it in 1794, he married the daughter of a Scotchman called Dale, the owner of a large spinning mill at New Lanark, which he purchased and of which he assumed the control on January 10th, 1800, at the age of twenty-nine.

Robert Owen had imbued himself more or less conscientiously with the ideas of certain eighteenth century philosophers. He believed with Rousseau that man is born virtuous and that society has corrupted him, and that evil is inherent in institutions and not in man. He thought with Helvetius that all men possess the same degree of receptivity, so that man is the product of his surroundings with neither liberty nor responsibility of his own. It is necessary, therefore, to prevent evil and not to repress it. In order to prevent it, it is necessary to organise a machine into which every individual shall fit and perform the function which he sought to perform without realising it.

This conception is not new. The organisers of every religion have subjected their followers to dogma and ritual; by faith they destroy individual thought, by ritual they subject men to fixed mechanical observances. The repetition of impressions stores up a particular sentiment in a particular group of cells in the brain, which cause the performance of a particular definite act. Creeds, education, and military discipline never were and are not anything but the more or less systematic organisation of the phenomenon which is termed reflex action in the science of physiology. Owen furnishes an example. He is desirous of having the best machinery and the best cottons, but it is necessary to extract the greatest possible amount of advantage from them by means of a well-trained staff which is not overworked and is well fed and healthy, and is not enfeebled by drunkenness and disorderly living. He devotes himself to the well-being and the discipline of his workmen and prepares recruits for the future by undertaking the education of their children; but he does not interfere directly, although kept informed of the personal condition of his employees.

While holding that man is irresponsible and consequently ought not to be punished, he has recourse to a form of moral correction. Over each loom there hangs a square of wood, each side of which is painted a different colour, black, blue, yellow, and white. If the workman has misconducted himself on the preceding day, the colour which is exposed to view is black, if he has conducted himself well it is white. Owen by walking through the workshops sees at a glance upon the "telegraph" the condition of each of his employees, but he never remarks upon it to them.

The measures taken by Robert Owen, and his commercial practices, marked as they were by a niceness which inspired all the more confidence by reason of their unexpectedness, assured the success of his undertakings. But not content with doing good business, his desire was to transform the world.

In 1800 children were largely employed who belonged to the parish by virtue of the Poor Laws, and were cruelly over-worked. Owen, by precept and practice, showed how to reform the system under which they were abused, and on his competitors failing to follow his example he appealed to the legislature and obtained the Act of 1802, which formed an addition to the Poor Laws. He persevered and obtained the Act of 1817. He also desired to find a solution to the question of unemployed workmen during the crisis which followed the revolutionary wars.

Owen was never at a loss. He considered that the masses should be led by superiors, without enquiring into the origin of the right of control which he possessed, taking those who were out of work and making them inmates of "nurseries of men," to use his own bold and characteristic expression.

Owen is an example of how a great captain of industry may thoroughly understand the conduct of his own business and may yet lose his footing when he meddles with politics. While himself employing the most highly perfected machinery, he looked upon machinery as the origin of the suffering of the workers, and in order to supply them with work he proposed to substitute the spade for the plough. This industrial worker dreamt bucolic dreams, and, considering agriculture to be the source of all riches and virtue, he desired to have the State organised as an agrarian community divided into communities of from 2,000 to 3,000 inhabitants, each of which should be self-contained and self-sufficient.

II

Owen was prepared to put his experiments to the proof, and did so at Motherwell, in Scotland, with a capital of £50,000. But M. Dolléans devotes himself to the study of a more important one of which full information is available—this was "New Harmony" in Indiana, U.S.A.

The point was to substitute a new organisation for an existing communistic organisation, namely, that of the Rappists. The Rappists had succeeded, but each of them desired to have his share of the capital of the Society instead of leaving it undistributed. This ending might have enlightened Owen as to the ultimate consequences of his experiment in admitting that everything there was for the best. He proceeded to the United States in 1825, and made a great to-do over his foundation. He enlisted Maclure, a rich American (who contributed 150,000 dollars), a number of philosophers, and eight hundred visionaries and persons of unsettled temperament, dreamers of either sex, each one of whom believed communism to be the ideal, provided that his system was accepted, as well as some adventurers and knights of industry.

On May 1st, 1825, the experimental or preliminary society was constituted. Every one is under a general duty to place his capacity at the service of the community, for each member of which an account is opened, the value of his services being carried to his credit and his various expenses to his debit. In the result this beautiful arrangement merely ended in the most complete anarchy. At the end of six months the industries left by the Rappists disappeared and there was neither labour nor control. Those who might feel disposed to work were unwilling to do so for the benefit of the idle. A large amount of discussion and disputation ensued, and a convention was nominated, which, on June 5th, 1826, adopted a constitution which confuses juridical and moral questions. It is preceded by a declaration of general principles, in the front rank of which there figure community of goods, equality of rights and of duties, sincerity and honesty in all acts, freedom from responsibility and the abolition of punishments and rewards.

The assembly, which consists of all the members of the community of either sex of more than twenty-one years of age, is possessed of legislative power; the executive power is vested in a council consisting of three ministers, elected by the assembly, and of a secretary, a treasurer, a commissary and six superintendents, each placed at the head of one of the six departments of the community. Who appoints these superintendents? Their subordinates of more than sixteen years of age, subject to ratification by the general assembly. This restriction was not sufficient to invest these departmental chiefs with authority, they were dependent for it upon those whom they employed, while at the same time it was their duty to furnish the executive council daily with their opinion upon the persons under their authority. It would be difficult to find an organization better adapted to promote impotence and dissensions.

When Owen returned after the lapse of a year, he found "New Harmony" in dissolution, but with remarkable optimism he did not despair. He accepted the dictatorship, but on April 15th, 1828, he was obliged to admit the failure of an experiment which had cost him personally 200,000 dollars. I will not exaggerate this negative result; it is obvious that the elements of which the population which came to make the experiment was composed were not the most suitable for ensuring its success. One is none the less entitled to enter it on the debit side of the communistic account.

These experiments failed to discourage this practical man from his visionary dreams. From 1834 until his death he published a weekly newspaper, the "New Moral World," in which he persisted in proclaiming his unsectarian millennium, a new moral world which was to abolish individualistic competition in the interests of communism.

CHAPTER VIII

FOURIER AND THE AMERICAN PHALANX↩

- A maniac's ravings—Attraction of the passions—The passions and the constant persistence of species—Series or groups of passions—The phalanstery—Division of profits — Experiments — Victor Considérant.

- Experiments in the United States—The North American Phalanx.

I

FOURIER, born in 1772, was the son of a draper at Besancon. A brilliant scholar, he found trade unworthy of himself, and conceived a hatred of business avocations, which was all the greater in proportion as they disturbed his maniac's ravings. His love of order was such that in his walks abroad he would take the measurements of a building or a public garden. In his passionate devotion to flowers, he desired to possess every variety of each species and to cultivate it. He adored music, and was full of enthusiasm for military displays.1 He was an ardent admirer of the universal harmony which enabled the stars to travel through an eclipse without colliding, and drew therefrom the conclusion that humanity must obey a principle of harmony as the planets obey the law of gravitation. It did not occur to him that Newton had merely ascertained the relations between these phenomena and that these phenomena existed before Newton's time, and he fancied that on the day when a genius analogous to that of the English philosopher should have discovered this principle, all the difficulties of social existence would be dissipated.