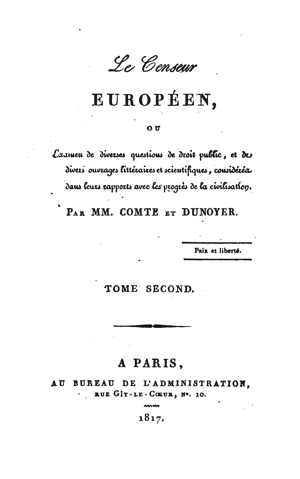

CHARLES DUNOYER,

"Considerations on the Present State of Europe",

Le Censeur européen (March 1817)

Charles Dunoyer (1786-1862) |

|

[Created: 9 April, 2025]

[Updated: 9 April, 2025] |

Source

, "Considerations on the Present State of Europe, on the Dangers of this State, and on the Means of escaping them", Le Censeur européen, T.2, (March 1817), pp. 67-106.http://davidmhart.com/liberty/FrenchClassicalLiberals/Comte/CenseurAnthology/EnglishTranslation/CE05-Dunoyer_ConsiderationsPresentState_T2_1817.html

Charles Dunoyer, "Considerations on the Present State of Europe, on the Dangers of this State, and on the Means of escaping them", Le Censeur européen, T.2, (March 1817), pp. 67-106.

A translation of (D…..r), "Considérations sur l'état présent de l'Europe, sur les dangers de cet état, et sur les moyens d'en sortir", Le Censeur européen, T.2, (March 1817), pp. 67-106.

See the French version of the essay in enhanced HTML and facs. PDF.

This book is part of a collection of works by Charles Dunoyer (1786-1862).

[67]

Considerations on the Present State of Europe, on the Dangers of this State, and on the Means of escaping them↩

We previously explained how, under the system of the political balance of power, Europe came to be constituted. [1] We said that in this system, the European powers were divided into two armed confederations of roughly equal strength, and that the supposed aim of this division was either to maintain peace among them or to ensure their mutual independence. We established that this purely military organization was incapable of achieving either objective; we said that, having its source in the spirit of war, it could produce nothing but war, and that, precisely because it tended to perpetuate war, it placed the independence and tranquility of all states in constant jeopardy. We said that the only means capable of securing peace for the [68] people, and independence for governments, lay in the destruction of the errors and passions that favor war, in the spread of ideas favorable to peace; that general wars in Europe could end only through the same causes that brought an end to private wars; that they would cease only when a new Nation had arisen in Europe, to whom wars between sovereigns would appear as despicable and intolerable as the private brigandage of feudal lords once appeared to their subjects, and when this Nation had acquired sufficient coherence and strength to suppress, wherever they might arise, the passions that favor war. Finally, we said that the ideas suited to forming such a Nation already existed, that these ideas were circulating throughout Europe, that they had already united the majority of enlightened individuals in every country, and that they were more or less felt by that portion of the European population which demands reforms and the establishment of a sound representative system.

There is therefore, at the heart of Europe, already a strong enough nucleus of this new Nation, this European Nation, this Nation hostile to [69] war and despotism, whose progressive rise must simultaneously liberate and pacify Europe. Let us examine what the consequences of this fact have been so far.

The first that strikes us is that, by the mere fact of the existence of this Nation and the growth it has already achieved, the constitution of Europe has been altered; the system of the balance of power is more or less destroyed, or at the very least, the foundations of this system have been displaced, and balance is no longer maintained, as before, between one half of the powers and the other half, but between one half of the population and the other: from the old people to the new people, [2] that is, from that part of the European population which appears determined to preserve arbitrary power, the spirit of war, monopoly, etc., to that part which demands peace and liberty.

The system of the balance of power as it was established, the balance of one group of powers against another group ofpowers, could subsist only so long as the old group of people exercised unchecked absolute power in each state, so long as they could impart their passions to the masses and fully command their resources. When the Nation we are concerned with, the Nation of the industrious, [3] [70] began to resist the old group within each state, the latter's external influence had to diminish; the system of the balance of power began to weaken. As this Nation grew and the resistance spread, the system weakened more and more. Finally, the moment came when this Nation became strong enough, and raised enough internal resistance, to force the leaders of the old group of people to renounce any action of one against the others, and to unite instead in self-defense. This is what occurred at the beginning of the French Revolution. For the first time, the European powers forgot their old rivalries; and instead of remaining divided into rival confederations, they formed a single confederation, meant to contain the movement of the new Nation, one that sought to elevate its own interests above the passions of the old, and to give precedence in Europe to the spirit of peace, industry, and liberty, over the spirit of war, monopoly, and despotism that had previously dominated. Unfortunately, this Nation, misled by false doctrines and embittered by the resistance it encountered, lost sight of its aim. The entire party directing the movement veered off the path of civilization; it became conquering [71] and warlike, and the very spirit it was meant to destroy prevailed more than ever. At that point, the balance once again took the form of one power against another power; it became a war of new kinds of oppressions against old kinds of oppressions. In that struggle, the old oppressions were defeated after a long fight; but (even though) (the supporters of the new oppressions) had originally joined forces with the Nation of the industrious to oppose the friends of peace and liberty, eventually the latter prevailed and the new oppressions were destroyed. What happened then? The Nation of the industrious, rising again, more numerous and stronger than ever, frightened the old group of people with its power; and so now, as in the early years of the Revolution, the balance is still maintained not between one group of powers and another, but between the old Nation to the new Nation, and that is what concerns us here.

Another consequence of the existence of this new Nation is that, at the same time as it led the members of the old one to unite and form a confederation, it also stimulated them to increase their strength, to concentrate it further; and the more the new Nation has progressed, the more the authority of the old one has expanded. We have [72] noted elsewhere how, in France since the beginning of the Revolution, the latter has augmented its means of action. [4] This observation, unquestionably true in France, holds just as true in the other states of Europe. The old group of people now possess, without a doubt, more nominal power and material resources than they did before the Revolution; they generally maintain larger standing armies, they collect more in taxes, they have in their pay a vastly greater number of men, all branches of administration are more firmly in their grip; in countries where their authority appears limited by fundamental laws, it is in fact much more extensive; and finally, while in each particular state they are equipped with greater means of action, they have also established, in the midst of Europe, a kind of central government [5] supported by considerable forces, whose mission seems to be the surveillance of the new Nation and the suppression of its movements wherever they might erupt with too much force, especially in France, where such movements would be more dangerous than elsewhere.

[73]

What, then, is the current state of Europe? What is its true constitution? It is this: Europe, as under the old system of the balance of power, is still divided into two great confederations; but the difference now is that each of these confederations is composed not of distinct states, as under the old system, but of men with differing opinions and opposing interests. It is old Europe struggling against the new; it is barbarism wrestling with civilization. In one of these two confederations, one sees farmers, merchants, manufacturers, scholars, industrious individuals of every class and from every country; in the other, the majority of the old and new aristocracy of Europe, office-holders, professional soldiers, idle and ambitious men of all ranks and from all nations, who seek to enrich and elevate themselves at the expense of working people. The goal of the first is to root out three great scourges from Europe: war, arbitrary political power, and monopoly; to ensure that everywhere, in every country, one may freely engage in any useful industry and be assured of enjoying its products; finally, to introduce forms of government most capable of securing these benefits and of securing them [74] at the lowest possible cost. The aim of the second is solely to exercise power, as safely and profitably as possible, and to that end, to maintain war, arbitrary power, trade prohibitions, and so forth. The first is not organized; its members, scattered and unevenly distributed across the various regions of Europe, have only weak and uncertain connections with one another; they possess no center of action, neither particular nor general; their strength lies entirely in their number and in the evident justice of their demands. The second, on the contrary, is strongly and skillfully organized; it has nearly as many centers of action as there are different states in Europe, and, at the heart of Europe, a general center of action; there exist regular and frequent connections among its members; it possesses immense means of government, etc. Finally, the more the first expands, the more it acquires moral influence through the spread of its ideas on the aims and forms of government, the more the second increases its material means of resistance, and appears to be exerting itself to divert the other from the goal it seeks to attain.

Such, in truth, is the state of Europe. Is this state more secure than the one that preceded it? Is this [75] kind of balance of power better suited than the old one to establishing public peace in Europe and the security of its governments? We cannot believe so. Every balance of power is a state of struggle, and from this one, as from the other, many revolutions and wars may arise. That would even be inevitable if, as the new Nation grows, becomes more enlightened, and strengthens, the other continually seeks to increase its own means of action and becomes all the more formidable as it faces greater resistance. Let us recall why the Revolution began. There were complaints about the excessive spending of rulers, the excess of their powers, and the abuse of those powers. Well then! It cannot be denied that their spending has since become far greater, their powers more exorbitant, their arbitrary actions more glaring and more numerous, that is to say, the evils that provoked the complaints have grown extreme. Suppose things continue in the same direction: what will result? That people will stop complaining? That they will be more patient, because they suffer more, understand better the cause of their ills, and are more capable of remedying them? It would be quite unreasonable to believe so. It is clear that if people could not endure a better condition when they were more ignorant and weaker, they [76] will not endure a worse one as they become more informed and stronger.

This new balance of power can thus give rise to many wars and upheavals, and it is greatly to be desired that Europe may soon emerge from a condition that seems to invite revolutions. Still, if it would be unwise to try to remain in it, it would be no less dangerous to try to leave it too hastily. There is as much peril in precipitating the course of events as in trying to stop their progress. The new state of Europe is a stage through which we must necessarily pass to reach the goal toward which civilization leads us, and it cannot be either avoided or skipped over. The Nation of the industrious had to become much stronger than the old aristocracy of Europe in order to be able to overthrow feudal tyranny; it is not enough that it merely counterbalances the forces of absolute governments [6] and of all the interests that support them, to be able to undertake [77] to disarm them and strip them of what is violent and oppressive in them. We must not lose sight of the fact that its members are still scattered and, in a way, unconnected; that they lack communication; and that they are not yet organized, while in general their enemies are. This puts them at a great disadvantage and compels them to act with the utmost prudence.

But what should this conduct be? By what means can the Nation of the industrious lead Europe out of the state of crisis in which we now see it, and guide it without upheaval toward the goal to which it aspires? How will it manage to disarm barbarism and secure the triumph of civilization? What should its policy be, both within each individual state and toward each specific government, and in Europe more broadly, in relation to all governments taken together and considered in their external relations? Let us first consider what its conduct should be within the interior of each state.

The numerous and rapid upheavals that have occurred in Europe over the past quarter-century have instilled in many minds, especially in France, where these upheavals have been more frequent and more numerous [78] than elsewhere, a most dangerous disposition: that of wanting to remedy the ills caused by bad governments through revolutions. As soon as a government disappoints the expectations formed of it or the hopes it had inspired, the first idea that comes to many people is to overthrow it and put another in its place; from that moment, they place all their hopes in a revolution. Such a blind impulse must not guide the Nation of the industrious; none could be more fatal to its aims, more contrary to the goal it seeks to attain.

We have already pointed out elsewhere how changes in government are an insufficient remedy for the ills that a flawed administration inflicts upon the people. [7] We believe it necessary to return to this fundamental idea and to show that such a remedy serves only to worsen the evil to which it is applied, that a violent revolution only delays the progress of liberty.

A single consideration will suffice to make the Nation of the industrious realize just how [79] vain, for the goal it seeks, are any attempts aimed directly against governments: such efforts would add nothing to its real strength, and if it did not already have enough strength to compel the existing government to move in a good direction, it is hard to see how it could, on its own, have enough to overthrow that government, establish a better one, and keep it on the right path. When a political upheaval has taken place, there is, as a result of that upheaval, neither one more idea nor one more virtue in the state where it occurred. The Nation in question thus gains absolutely nothing from it; and if the new government wishes to abuse its power, the Nation has no more means of restraining it than it had to compel the one that fell to use its power well.

A revolution, then, does not increase the Nation’s strength; we could go further, it actually diminishes it, because it increases the strength of its enemies. In times of revolution, despotism always finds around itself a greater abundance of vice and folly to put to use, and thus greater means to resist the advance of civilization. The effect of any revolution is to draw into the channels of power a multitude of new recruits, and to draw in, [80] especially, auxiliaries of despotism. When revolutions break out, who are the men we see rushing forward to take part in the movement? Are they farmers, merchants, manufacturers, enlightened and well-off industrious citizens, those who are genuinely interested in resisting the excesses of power? No, they are almost always idlers, the ambitious, men with fortunes yet to make, and who by their position are ready to serve any tyranny that will enrich them. These are the men revolutions place on the stage, the men they call to gather around power: they always bring together a new caste of willing actors. [8]

And that’s not all: while placing these willing actors within reach of power, revolutions also incite them to use it; they give it impetus and terrifying scope. Despotism is reinvigorated by civil wars; it trains itself in arbitrary power and violence, and it always emerges armed with new instruments of oppression. As soon as a government is attacked, it hastens to provide for its security through extraordinary measures, it arms itself with new powers, surrounds itself with new forces. If it emerges victorious from the assault, it keeps in its [81] hands the weapons it had seized to defend itself, and the danger is never far enough off for it to be willing to lay them down. If, on the contrary, it is overthrown, whoever rises in its place keeps the forces he had mustered to topple it, and he never finds himself secure enough to do without them. So that, no matter the outcome of the struggle, the power that emerges from it is always stronger and more oppressive than the one that was meant to be destroyed. This was clearly observable throughout the course of France’s upheavals: with each new revolution, power made new conquests, and it is through the accumulation of revolutions that it has reached the level of expansion which now seems to render any further progress impossible.

And it is not only where they break out that revolutions tend to reinforce power; their effect is felt wherever their influence reaches. A revolution that were to break out in Germany would unfailingly prompt new security measures in France. A revolution that broke out in France would produce the same effect in Germany. At the point things have reached today, it is impossible for one government to be attacked without all the others immediately taking alarm and [82] working to increase and concentrate their own means of action. This was clearly seen during the French Revolution. That revolution brought about, almost everywhere, gains for power similar to those it achieved in France. It weakened the guarantees of liberty in every place: in England, it suspended for seven years the laws protecting individual security; it placed in the hands of several German princes enough force to overthrow all limits placed on their authority and to govern their subjects despotically; finally, it prompted such prodigious increases in the military and financial systems of all the powers of Europe that it is difficult to understand how the Nation of the industrious does not collapse under the double burden of the armies and taxes that weigh upon it.

The results of the revolution of March 20th are particularly revealing in showing how a revolution carried out in one state can, in others, increase the strength of power and diminish that of liberty. This revolution augmented the machinery of despotism [9] not only in France, but throughout Europe. While in France it gave rise to the creation of a new army, composed partly of foreigners [83] and partly of Frenchmen, to the establishment of provost courts, to the suspension of constitutional guarantees for personal safety and freedom of the press; in England, it enabled the ministry to surround itself with an armed force of 150,000 men, to suspend the habeas corpus act, to forbid public assemblies, and thereby, in effect, to annul the right of petition, in short, to overthrow nearly the entire constitutional structure of the country. In Germany, it gave new solidity to standing armies, allowed for the postponement of several particular constitutions and the formation of the German Confederation, enabled the abolition of secret societies, the removal from public affairs of most men known for their commitment to liberty, the suppression of several popular newspapers, and the obstruction of liberal ideas moving from one state to another. Finally, it allowed the coalition to impose enormous war taxes on France and to install that army of occupation which weighs on all the free men of Europe. Such were the services rendered to power by the revolutionaries of March 20th, never have men, it must be said, done greater service to despotism.

[84]

And take note that the activity of these men could only have had an outcome fatal to liberty. For let us assume the most favorable circumstances for their cause: suppose that Bonaparte had been victorious at Waterloo; suppose, against all likelihood, that in a war which was not a national one from the perspective France but which was from the perspective of all the other people, and which was waged with particular fervor by the entire population of Germany; suppose, we say, that in such an unequal struggle Bonaparte and his partisans had won enough victories to reopen the question of everything decided in Paris and in Vienna, do you believe that the revolution of March 20th would then have taken a turn more favorable to liberty? Do you believe that, in the new round of wars that would have begun, governments would have lacked pretexts for increasing the size of their armies, raising taxes, expanding their powers, delaying the establishment of promised constitutions, or suspending the execution of those already in place? … Ah! The revolution of March 20th undoubtedly had very harmful consequences for liberty, but how much more fatal it might have become if Bonaparte had [85] won victories and the war had dragged on!

It is therefore certain that revolutions, uprisings, and acts of sedition serve only the interests of power. Would you like one last proof? We would say that bad governments have often called them to their aid, that despotism has always regarded them as its last resort. Is a new tyranny struggling to establish itself? Is an old tyranny feeling seriously shaken? Here is what they are often found to do: they anticipate the danger that threatens them; they incite the people to insurrection. Simple souls, fools, fall into the trap; then power steps in, seizes a great number of culprits, orders executions, adopts extraordinary measures of self-preservation, and the crime into which it has lured part of its subjects often suffices for it to bind the rest in chains.

In early 1804, Bonaparte, already consul for life, was contemplating his rise to become head of an empire. The step seemed difficult and dangerous; he feared that public opinion might strongly resist him. What did he do? He tried to subdue it through terror; he organized a grand conspiracy. He knew that the British government [86] had agents in Paris tasked with attempting his assassination. He conceived the idea of expanding the plot, of involving many individuals in it to give it greater impact and to draw greater power from it. Accordingly, he lured into France and into Paris, by promising to restore the Bourbons, a large number of prominent émigrés who had remained abroad. These men soon realized they had been tricked; some of them then joined Georges' conspiracy. Pichegru, who led them, attempted to bring Moreau into the plot. When things seemed far enough along, the consul began to have them quietly exposed by his police; soon after, he raised the alarm. A report from his Minister of Justice informed France that a dreadful conspiracy against the state and its leader was in progress. Moreau, Pichegru, Georges, and a large number of their alleged accomplices were arrested with great fanfare. Pichegru was strangled in his cell; the Duke of Enghien, seized in a foreign country as a suspect in directing the plot, was assassinated in the dungeon of Vincennes; the trial of Georges and Moreau began amid terrifying scenes, and in the midst of the fear provoked by these events, the scoundrel who had orchestrated them had himself declared emperor.

Toward the end of 1812, after the retreat from [87] Moscow, agents of this man, in a conquered country near France, were deeply worried that the disaster suffered by their master might appear to the population as a sign of weakened authority, and that the people might be tempted to take advantage of the moment to rise up and break free. Here is what they did to calm themselves: they tasked a wretch with fabricating a conspiracy. This man drew up a plan; he proposed its execution to a friend, an officer on half-pay, and to an innkeeper. These unfortunate men fell into the trap; others were ensnared as well. When the officials who had instigated the crime judged that enough individuals were compromised and that enough evidence had been gathered against those they wanted to destroy, they began quietly spreading rumors that an insurrection was imminent; then they loudly announced that they had just uncovered the proof of a terrible plot. They seized the victims they had marked, pronounced sentence upon them, handed them over to the executioners, spread terror everywhere, and thus managed to soothe their own fears.

“The factories of England,” says General Pillet, “were completely idle in 1811: the workers were dying of hunger; [88] bread had risen to an excessive price; misery was widespread; discontent was universal. The ministry took advantage of this opportunity to recruit heavily for its armies, which were suffering immense losses in Spain; but part of the men employed in the factories were unfit for military service. There remained a great number of married men, children, and the elderly, who threatened, in the major manufacturing cities, an imminent insurrection. The ministry acted preemptively. The most threatening cities received relief, while the provinces of Lancashire, Nottinghamshire, and Derbyshire were given nothing but provocations toward insurrection.

“In these provinces, hosiery entirely done on looms and some cotton cloth was produced in small quantity; a great agitation was stirred up; the pretext used was that of the new looms. They had been invented to save labor, but they reduced the number of workers, and therefore, for the moment, they had to be destroyed. Such was the rhetoric of the emissaries of a ministry that counted on the credulity of the people; for it was absurd to claim to provide more work to manufacturers when those manufacturers were unable to sell their [89] goods or pay their workers. Agents sent by the ministers, claiming to be enlisted under the banner of Captain Ludd, from whom came the name Luddites, went about in small groups smashing looms; two large factories were set on fire; a leading manufacturer and factory owner was assassinated; several people died.

“The ministry then appeared to take measures to stop the unrest and prevent major disorder. Cavalry regiments were dispatched to those counties; some victims were sacrificed, executed, or condemned to deportation. Such measures easily put an end to seditions to which the people had turned with a kind of reluctance.” [10]

We could easily cite further facts similar to those just reported. But these are surely sufficient to establish the truth that these facts aim to demonstrate.

Let us summarize our ideas. Revolutions, we have said, accomplish nothing; they do not increase the strength of the true friends of liberty; they add nothing to the stock of [90] knowledge and moral qualities necessary to resist despotism; they subtract nothing from the sum of vice and folly necessary to sustain it. Far from weakening despotism, they always furnish it with new supports; they place at its disposal a multitude of new auxiliaries; they invite it to make use of them, they incite it to strengthen itself, and no matter whose hands it ends up in, power always emerges from the storms stirred up by revolution stronger than it was before. Despots are so convinced of these truths that they have often provoked revolutions in the interest of their own power. Finally, revolutions tend to increase the material strength of power not only where they occur but wherever their shock is felt, this is made glaringly evident by the consequences of the French Revolution.

The first law that the Nation of the industrious must lay down for itself in every state, then, is to combat with all its strength that blind tendency toward revolution into which the French revolutions have cast so many. This tendency would be for it an endless source of disappointment; it would only drive it ever [91] further from the goal to which it aspires, and make its enemies increasingly formidable. It is not by struggling directly against despotism that it (the Nation of the industrious) will succeed in destroying it (despotism), but by (taking steps) to make itself more effective and (to appeal to) the deluded men who defend it, by gaining a clear understanding of its true interests, by gradually spreading enlightenment among the masses under despotism’s sway, and by working to recruit allies among them. When it has spent a long time recruiting on behalf of civilization, when it has managed to make a very large number of people understand and desire what is truly in everyone’s interest, then it will put itself without effort into a position which aligns with its goals. It will not need revolutions to do so, or rather, it will have accomplished the only revolution capable of placing it in such a position: that is, it will have disarmed despotism, stripped it of its auxiliaries, and reduced power to what it ought to be, a simple and inexpensive means of providing security. Until then, no matter how often it is made to change hands, power can always be tyrannical; for it will always find around it the means to become so. No matter how many barriers are placed around it, it will, in a sense, [92] only gain new supports; for it will always be able to create those barriers out of men who are inclined to support it. Representative forms of government, so well-suited to moderating its action in places advanced enough to have good public assemblies, usually serve only to make it more violent and oppressive in countries where the only men available for representation are ignorant or corrupt. Therefore, the aim should not be to overthrow governments, but rather to become enlightened enough, and to spread sound ideas widely enough, that it becomes more and more difficult for bad governments to do harm.

How greatly it is to be regretted that such a tendency has not always been followed! How much further along we would be today! How many fewer obstacles would remain to be overcome, and how much better equipped we would be to overcome them! How many efforts have been made in vain! How much blood shed needlessly! Suppose that all the energy of our hearts and minds which were expended over the past quarter-century in making and unmaking governments had instead been employed in preparing the people and themselves to be capable of having better ones 9governments), how much closer would we now be to the moment when we actually have them? Suppose [93] that such a direction had been taken in 1814 and 1815 alone; that the men who made the revolution of March 20th had used just half the energy they spent defending Bonaparte to instead holding political authority within its limits, that they had rejected Bonaparte while also refusing to obey the arbitrary measures of the agents of political authority, how much would liberty have gained from such conduct? How much further ahead would all of Europe now be? Finally, suppose that from today forward, the men inclined to revolution would abandon the false path on which they have set themselves, and instead of placing hope for a better future in changes of power that lead nowhere, they would begin at once to work toward the only truly beneficial change, namely, the advancement of sound ideas, how much strength would the cause of liberty gain immediately? …

But a powerful cause has until now, and no doubt will continue for a long time, to stand in the way of any departure from the path of revolutions: it is that, in general, people aspire much less to improving governments than to rising to positions of power. It is important to clearly characterize this tendency and to show how much, in the struggle [94] in which the Nation of the industrious is engaged, it serves to diminish their strength and increase that of their enemies.

At all times and at every stage of civilization, political power has been a highly productive means for those who exercise it. Among completely barbarous hordes, power, exercised collectively, brings the horde cattle to divide, captives to slaughter and devour. Among slightly more advanced people, it yields lands to seize, men to enslave and tie to the soil as laborers. For the Greeks of the heroic age, political power yielded flocks, women, and other goods which they had joined forces to plunder. Among the Romans, who were organized for conquest, pillage, and global enslavement, power yielded land, booty, slaves, of which each citizen received a share based on his rank in the army or in the people, according to the part he played in wielding power. In other times and among other nations, power has been no less productive. We know what it brought to the people of the North when they invaded and subjugated the South. We also know what it provided to their descendants for a long time, to those valiant noblemen [95] who, on their lands and in their fortified castles, were so well organized for plundering the countryside and committing high-way robbery. In modern times, power has become even more lucrative than it was in the Middle Ages. It has profited from every advance of civilization, and the more that labor and industry have created wealth, the more political power has become a excellent means of enriching oneself. Its tools of plunder have multiplied, expanded, and been refined; and today they are perfected to such a degree that there are countries in Europe where, through the aid of a machine called national representation, and a few other tools called soldiers, customs officers, tax agents, etc., political power provides, without combat, without noise, without scandal, to the small number of men who wield it, one-fifth, one-quarter, one-third, even up to one-half of all the revenue of a great nation. So far, we have spoken only of the material profits of power. How much more we could say if we were to detail the moral satisfactions it offers! It produces the pleasures of action, vanity, and security. It grants genius, celebrity, esteem, glory. It is the source of all the [96] goods that the human heart most ardently desires.

Power is therefore a good thing, an excellent thing. One might say that, until now, it has been the most profitable of all professions, at least for those who have exercised it. And what has come of this? That the entire world has wanted to wield it. Power has been the great object of humanity. In all countries, in all eras, nearly all individual and collective effort and activity have been directed toward that end, as though it were man’s true purpose. In every society, each member has aspired to dominate others; and in the great society of humankind, each particular society has aspired to dominate other societies. The movement of the species as a whole has been to rise gradually toward power. In fact, this is what the “progress” of society has often consisted of; and civilization, whose effect should have been to gradually draw humanity away from this savage tendency, and to encourage people to exert themselves collectively against things rather than against one another, seems to have done nothing more than bring an ever-growing [97]number of men into power. It is a phenomenon whose development is curious to trace throughout the progress of civilization.

In the barbarism of the Middle Ages, political power in Europe was the exclusive privilege of the men who had overthrown the Roman Empire. These men, accustomed to living by plunder, were the scourge of the industrious class. [11] As this class rose, the interest of civilization, at whose forefront it stood, should have been to draw gradually to itself the barbarians who had once kept it under the yoke; to lead them to abandon their trade of war and pillage, and to transform them, little by little, into industrious men. [12] That was the direction things ought to have taken if they were to align with the progress of society. Instead, they took exactly the opposite course. The industrious class did not recruit from the idle and predatory class; [13] rather, the idle and predatory class continually recruited from among the industrious men. Civilization has done nothing but send it reinforcements, and its fate seems to have been to elevate men from the laboring classes only to watch them betray its cause and pass over into the ranks of its enemies. Observe, indeed, the path followed by these men [98] since civilization began to make progress in Europe, and especially since the emancipation of the communes. Their tendency has always been to rush into power. As they rose, they were seen abandoning industry, the very source of their wealth, and devoting themselves to the unproductive exercise of public functions or so-called liberal professions. In France, as soon as a farmer, a manufacturer, or a merchant had acquired some wealth, nothing seemed more urgent to him than to take it to government to be devoured,and to ask in return to be admitted to the ranks of those with the exclusive privilege of exploiting the public wealth. This was called ennobling oneself. That desire to ennoble oneselfwas universal in France; and even before the Revolution, it had brought a considerable portion of the population into the idle class. [14]

Finally, one day, the entire people wanted to become noble; it was the very day when, through the voice of its representatives, it decreed the abolition of the nobility and proclaimed itself sovereign people. On that day, the French people truly made itself noble, for it hurled itself headlong into political power. In vain did those who had until then enjoyed it exclusively try to bar the people’s entry; their resistance [99] only intensified the people’s desire to ennoble itself and made it aspire to power with even greater violence. The farmer left his fields, the artisan his workshop, the merchant his shop, the scholar his books, and an entire population of men once devoted to the practice of the arts, commerce, and all forms of production threw themselves into the clubs, the administrations, the armies, every branch of power. The people began to govern the people, to exploit the people, and they did not seem to realize they were devouring themselves. Since then, this disposition to govern has not only persisted but grown stronger. Under Bonaparte, it became a true frenzy; there was not a family in the Nation that did not want a government job, nor an employee in government who did not aspire to govern as much as possible. After Bonaparte’s fall, the same disposition may have taken on an even greater intensity, and it was especially reinforced by the claim made by former holders of power that they intended once more to monopolize it. [15] That claim outraged the mass [100] of citizens more than most attacks on the security of their fortunes or their persons. It provoked the revolution of March 20th; it led to that of September 5th; and who knows what more it may yet bring. Finally, it is not only in France that the people are afflicted by the mania for governing, it is the case in England, in Germany, everywhere. In England, the people demand to take part en masse in elections and to form a new Parliament every year. In Germany, people no doubt love liberty sincerely, but they perhaps love equality even more; and while the people wish to shelter themselves from arbitrary rule, they especially aspire to take part in the exercise of public functions. In both countries, it seems that the goal is less to draw the government into the Nation than to get the Nation to enter into the government: [16] that is the universal tendency in Europe.

This is where we are; this has been the march of civilization. As we [101] have said, it has done nothing but bring a continually increasing number of men into power. It first multiplied the number of nobles; then it incited whole people to ennoble themselves, to proclaim themselves sovereign: the French people proclaimed itself sovereign, the English people proclaimed itself sovereign, the German people is proclaiming itself sovereign; only the Spaniards, Austrians, and Russians have not yet risen to that dignity, but they, too, will surely wish to reach it in turn. And once all the people of Europe have thus declared themselves sovereign in right, there will remain for them only one step to achieve complete perfection: to become sovereign in fact, that is, to abandon the care of agriculture, commerce, and the arts in order to rule themselves.

If the people of Europe ever come to that, one could say that the effect of civilization will have been to lead them to the highest degree of barbarism; for the pinnacle of barbarism, for man, is to make government his goal. It is because they made government their goal that the ancient people had slaves; that the Romans ravaged the world; that the Germanic tribes bound [102] the people of southern Europe to the soil; that their descendants exploited them for fourteen centuries; that the French, for the past twenty-five years, have committed so many horrors and follies, etc. We have said it twenty times already; we will repeat it a thousand more: the goal of man is not government; government ought to be, in his eyes, only a very secondary thing, we would even say a very subordinate one. His true goal is industry, labor, the production of all things necessary to his happiness.

In a well-ordered state, government should be only a subsidiary [17] of production, a commission paid by the producers which is tasked with ensuring the safety of their persons and their property while they work. In such a state, the goal must be for the greatest number of individuals to work, and the smallest number possible to govern. The pinnacle of perfection would be for everyone to work and for no one to govern. Instead, the result is that no one wants to work, and everyone wants to govern.

If this were strictly true, if it were true that instead of making production their goal, the whole world wanted to make [103] political power its object; that instead of wishing to be industrious, everyone wanted to be noble; that instead of wanting to work, everyone wanted to govern, the world would perish instantly. For if production ceased entirely, and since nature supplies free of charge only a very small portion of the things we need, it is evident that mankind would no longer have the means to survive. Fortunately, though a people proclaim themselves sovereign in theory, a good portion of the individuals they comprise remain industrious in practice. In their current state, one could compare these people to swarms made up half of wasps and half of bees, swarms in which the bees agree to produce torrents of honey for the wasps, in the hope of preserving at least a few combs for themselves. Unfortunately, they are not always left even that small portion. As a result, many bees, weary of working without enjoying the fruits, aspire to cross over to the side of the wasps, who enjoy without working; in other words, many industrious people, seeing how rewarding the business of government is, and how ungrateful and burdensome that of production, are drawn to abandon their useful labors in order to swell the ranks of the crowd of devouring or useless men.

[104]

It is this abundance in which the men who govern live, at the expense of those who work, that has always provoked in the ranks of industry these numerous defections, these frequent desertions to the enemy, and, within the population at large, that universal inclination to rush into power which we have just described. It is enough to have clearly characterized this tendency to immediately feel how ruinous it is to the Nation of the industrious, how much it serves to reduce its strength and to increase that of its enemies.

Power grows stronger with every loss suffered by the Nation of the industrious; the more its auxiliaries multiply, the more violently it can act upon it (the Nation of the industrious). And that’s not all: when the number of claimants to power grows too large and Industry can no longer produce enough to satisfy all their appetites, there always comes a point when they begin to quarrel over who shall have the right to extract taxes from it, and their discord proves even more fatal to it than their unity. After each revolution, as we have shown, it (the Nation of the industrious) finds itself more weakened and more enslaved than it was before. Every violent measure each faction takes against [105] its rivals rebounds to the injury of it (the Nation of the industrious); and what's more, since the triumphant faction is never certain of holding on to power for long, this very uncertainty drives it to exploit its position to the fullest extent, and this, too, brings ruin upon it (the Nation of the industrious). One could go on endlessly detailing all the harmful consequences that stem from the tendency of people to thrust themselves into government. It (the Nation of the industrious) must therefore devote all its energy to changing this blind tendency: this must be its chief task. Until now, the people of Europe have made their glory consist in securing dominion over one another; it (the Nation of the industrious) must strive to redirect their ambition toward a higher and more profitable goal, that of exercising, together, a great collective influence over things. Whereas the movement of civilization has gradually turned every gaze toward political power, it must now work to redirect those gazes back toward itself, striving to strip power of the means to seize its treasures, and to deprive it of the ability to influence men through the lure of wealth or the seductions of vanity.

Thus, to call men back to labor and industry, to turn them away from the pursuit of power, to reduce the strength of the tyrants who [106] abuse it, or of the factions who contest it, to prevent war from breaking out between those factions, and to stop power from growing stronger through their discord: this must be, within each state and with respect to each government, the course of action for the Nation of the industrious. In another article, we will examine what its policy should be with respect to all governments taken together, and we will consider in particular what national independence means for it (the Nation of the industrious), and to what extent it should concern itself with the independence of each state, as that word is commonly understood.

D…..R.

Endnotes↩

[1] See Vol. I, On the System of the Balance of European Powers. (Editor: Charles Dunoyer, “Du système de l'équilibre des puissances européennes”, CE T.1 (Jan. 1817), pp. 93-142.)

[2] DMH: CD says "l'ancien peuple" (the old people) and "le peuple nouveau" (the new people). We have translated the pairing as "the old group of people" and "the new group of people".

[3] DMH: CD says "la Nation des industrieux" (the nation which is made up of the industrious people) which he uses 13 times in this essay. (Not sure what the best trans for this is - the "industrious Nation" or "the Nation of the Industrious). The term "industrieux" refers more generally to those who are 'industrious" and hard working in their activities, as well to a particular "class" - "la classe industrieuse" (the industrious class).

[4] See Vol. I, p. 339 and following. (Editor: Possibly CE vol. 1, (D….R), "De la loi qui suspend provisoirement la liberté individuelle," pp. 339-71.)

[5] DMH: CD says "une espèce de gouvernement central".

[6] We must call absolute not only those governments that are not parliamentary, but also the so-called representative governments in which the executive power controls the public assemblies according to its own will. It is even evident that the latter are much more absolute than the former; for they are infinitely more difficult to resist.

[7] See Vol. I, Considerations on the Moral State of the French Nation, etc. (Editor: (CC?), "Considerations sur l’état moral de la nation française, et sur les causes de l’instabilité de ses institutions", CE T.1 (Jan. 1817), pp. 1-92.)

[8] DMH: CC says "une nouvelle masse d'instrumens" (a new mass or heap of tools). Since he said previously these power seekers were "mettre en scène" (put on stage) "actors" seemed an appropriate translation of "instruments".

[9] DMH: CC says "le matériel du despotisme".

[10] England Seen in London and in Its Provinces, p. 138 and following.

[11] DMH: This is CD's first explicit reference to "la classe industrieuse" in this essay.

[12] DMH: CD says "des hommes industrieux".

[13] DMH: CD says "la classe oisive et dévorante".

[14] DMH: CD says "la classe oisive".

[15] Such a pretension was necessarily bound to have this effect. It is enough that one class of men should wish to govern alone, for all the others immediately to aspire to govern as well. If there had never been any nobles, there never would have been any sovereign people.

[16] DMH: CD says "moins d'attirer le gouvernement dans la Nation, que de faire entrer la Nation dans le gouvernement".

[17] DMH: CD says "une dépendance".