GUSTAVE DE BEAUMONT,

Ireland: Social, Political, and Religious (1839)

Volume 1

|

|

[Created: 17 December, 2024]

[Updated: 17 December, 2024] |

The Guillaumin Collection

|

This title is part of “The Guillaumin Collection” within “The Digital Library of Liberty and Power”. It has been more richly coded and has some features which other titles in the library do not have, such as the original page numbers, formatting which makes it look as much like the original text as possible, and a citation tool which makes it possible for scholars to link to an individual paragraph which is of interest to them. These titles are also available in a variety of eBook formats for reading on portable devices. |

Source

, Ireland: Social, Political, and Religious. Edited by W.C. Taylor (London: Richard Bentley, 1839).http://davidmhart.com/liberty/FrenchClassicalLiberals/Beaumont/1839-Ireland/index1.html

Gustave de Beaumont, Ireland: Social, Political, and Religious. Edited by W.C. Taylor (London: Richard Bentley, 1839). 2 vols.

This title is also available in a facs. PDF of the original [vol1 and vol2] and various eBook formats - HTML, PDF, and ePub.

See also the HTML version for vol. 1 and vol. 2 and 2-vols-1.

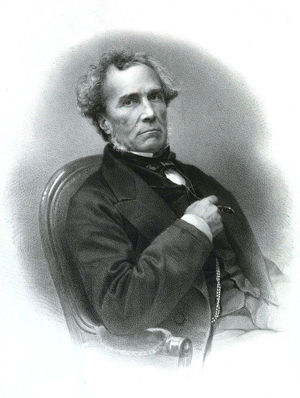

This book is part of a collection of works by Gustave de Beaumont (1802-1866).

CONTENTS OF THE FIRST VOLUME.

- Preface

- Historical Introduction. . . . . Page1

- First Epoch—From 1169 to 1535 . . . . 3

- Chap. I . . . . . . . ib.

- Sect. I. Political Condition of Ireland in the twelfth century . . . . . 8

- 2. The still recent invasion of the Danes . 11

- 3. Influence of the Court of Rome . . 13

- Chap. II.

- Sect. 1. Political condition of the Irish an obstacle to the Conquest . . . . 16

- 2. Second obstacle to the completion of the Conquest: the relation of the Anglo-Norman conquerors to England, and of England to them . . . . . 20

- 3. Third obstacle to the Conquest: the condition imposed on the natives by the conquerors 34

- Chap. I . . . . . . . ib.

- Second Epoch—From 1535 to 1690.

- Chap. I. Religious wars . . . . 41

- Sect. 1. How, when England became Protestant, it must have desired that Ireland should become so likewise . . . . 43

- 2. Of the causes that prevented Ireland from becoming Protestant . . . 46

- 3. How England rendered Ireland Protestant—Protestant Colonisation—Elizabeth and James I. . . . . 55

- 4. Protestant Colonisation—Charles I. . 61

- 5. Civil War—the Republic—Cromwell . 66

- 6. The Restoration of Charles II. . . 85

- Sect. 1. How, when England became Protestant, it must have desired that Ireland should become so likewise . . . . 43

- Chap. I. Religious wars . . . . 41

- Third Epoch—From 1688 to 1755.

- Chap. I. Legal Persecution . . . 100

- Chap. II. The Penal Laws . . . 115

- Special character of the penal laws . 121

- Another special character of the penal laws . 135

- Legal persecution beyond the limits of law . 137

- Persecutions continued when passions ceased 142

- Which of the penal laws were executed, which not 145

- The Whiteboys . . . 149

- Fourth Epoch —From 1776 to 1829.

- Chap. I. Effects of American Independence on Ireland 169

- Sect. 1. First Reform of the Penal Laws, 1778 . 174

- 2. Second Effect of American Independence on Ireland, (1778 to 1779.) The Irish Volunteers . . . . 175

- 3. Independence of the Irish Parliament . 181

- 4. Legal Consequences of the Declaration of Irish Independence . . . 183

- 5. Abolition of certain Penal Laws. Consequences of the Declaration of Parliamentary Independence . . . 194

- 6. Continuation of the Volunteer Movement. Convention of 1783 . . . 197

- 7. Corruption of the Irish Parliament . 200

- 8. Is a servile Parliament of any use? . 209

- Chap. II. The French Revolution—Its Effects in Ireland 217

- Sect. 1. 1789 . . . . ib.

- 2. —Other Effects of the French Revolution. Abolition of Penal Laws . . 227

- 3. —Other consequences of the French Revolution.—Reaction . . . 228

- 4. French Invasion of Ireland. Insurrection of 1798 . . . . 232

- Consequences of the Insurrection of 1798. The Union . . . . 240

- Constitutional and Political Effect of the Union 243

- Chap. III. Catholic Emancipation in 1829 . . 245

- IRELAND, SOCIAL, POLITICAL, AND RELIGIOUS. PART I.

- Chap. I. External appearance of Ireland. Misery of its Inhabitants . . . . . 249

- Chap. II. A bad Aristocracy is the primary cause of all the evils of Ireland.—The faults of this Aristocracy are, that it is English and Protestant . 276

- Sect. 1. Civil Consequences . . . 287

- Subsect. 1. Extreme misery of the farmers—Accumulation of the population on the soil—Absenteeism—Middlemen—Rack-rents—Want of sympathy between land and tenant ib.

- Subsect. 2. Competition for land—Whiteboyism—Social evils—Inutility of coercive measures—Terror in the country—Disappearance of landlords and capital . . 297

- Sect. 2. Political consequences . . 313

- Subsect. 1. The State . . . 317

- Hatred of the people to the Laws . 329

- A public accuser wanting in Ireland 330

- Unanimity of the jury in Ireland . 333

- Legal functionaries peculiar to Ireland 335

- Subsect. 2. The county . . . 338

- 3. Municipal corporations . . 345

- 4. The parish . . . 350

- Judicial authority . . 359

- Subsect. 1. The State . . . 317

- Sect. 1. Civil Consequences . . . 287

- Endnotes

- Notes

[I-i]

IRELAND: SOCIAL, POLITICAL, AND RELIGIOUS.

VOLUME I.

[I-iii]

PREFACE.↩

The opinions of an enlightened foreigner, unconnected with the political parties that divide the nation, are always replete with valuable instruction to a people. “To see ourselves as others see us,” is as difficult, and at the same time as useful, for societies as for individuals; but to no country is such an aspect of its condition so likely to be of service as Ireland, for in no other part of the world have all circumstances, small and great, connected with the moral, social, and political condition of the country, been so studiously and so grossly misrepresented. The Translator need only mention M. de Beaumont’s works on the United States to prove his competency as a political observer; and the extraordinary success which the present work has already had on the Continent, is evidence that his testimony respecting Ireland will guide the opinions of a great part of Europe.

There are some who affect to disregard the opinions which foreigners form of the domestic economy of our empire; “the snail,” says the Gentoo proverb, “sees [I-iv] nothing beyond its shell, and believes it the finest palace in the universe;” but though such recklessness may be felt or affected by ardent partisans in Ireland, it is not likely that a similar course will be pursued in England. The political supremacy of the British Empire rests so much on public opinion for its support, that nothing by which that opinion may be changed or modified can be neglected with impunity.

M. de Beaumont designed his work exclusively for continental readers, and therefore, on many points, entered into long and minute explanations respecting the details of British law and administration, which are unnecessary for English readers, and have therefore been omitted. This is the only liberty which the translator has taken with the text, unless the consequent modifications of the division of the matter be deemed changes that ought to be acknowledged.

It was originally designed to add notes and illustrations to the body of the work on the same scale as those appended to the Introduction, but this design has been relinquished to prevent the work from being identified with any of the parties to which the discussions have given rise, and to keep intact its most characteristic and important feature,—its being the record of opinions formed by an enlightened statesman, whose views are obviously beyond all suspicion of being warped by prejudice or passion.

[I-viii]

[I-1]

HISTORICAL INTRODUCTION.↩

The dominion of the English in Ireland, from their invasion of the country in 1169, to the close of the last century, has been nothing but a tyranny.

During the three first centuries they covered Ireland with deeds of violence, the object of which was the completion of the conquest.

The wars of conquest had not ended when those of religion began. England having, in the sixteenth century, renounced the Catholic for the Protestant faith, wished to convert Ireland to the new creed she had adopted, and finding the Irish rebels to her wishes undertook to constrain them; hence the obstinate struggles, the sanguinary collisions, and the terrible catastrophes which lasted more than a century.

When the wars which the Irish maintained for [I-2] the defence of their religion and country terminated, English oppression did not cease. Seeing that the Irish preserved their religious faith in spite of the violence employed to make them abandon it, England attempted to attain the same end by other means. She had discovered the inutility of force, and she tried corruption. Hence a persecution less barbarous, but not less cruel, more immoral, perhaps, because it assumed the semblance and supported itself by law, which continued nearly a hundred years.

This persecution ceased, not because England brought it to a close, but because Ireland would endure it no longer. One day Ireland undertook to shake off the English yoke, and commenced a struggle for independence, sometimes fatal, more frequently prosperous, which has lasted to our days.

The history of the English dominion in Ireland may be regarded under four principal points of view.

The first embraces the long convulsions of the conquest, from the reign of Henry II. to that of Henry VIII.

The second comprehends the religious drama of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries; it begins with the Reformation, or Henry VIII., and ends with the Revolution, or William III.

[I-3]

The third comprises the period of legal persecution, extending from the battle of the Boyne, in 1690, to the early part of the reign of George III.

The fourth, which may be considered as the new era of Ireland, because it is that from which the awakening of the country to liberty dates, has for its starting point the independence of the American colonies, and for its most remarkable feature in cotemporary history, Catholic Emancipation, in 1829.

The author is about to cast a rapid glance over those four epochs. These pictures of the past are absolutely necessary for the right understanding of the present.

FIRST EPOCH. From 1169 to 1535.

CHAPTER I.↩

In 1156, a bull of Pope Adrian IV. bestowed the kingdom of Ireland on Henry II., King of England. [2]

[I-4]

This bull proves, that even at this epoch Henry II. had extended his views to Ireland, whose sovereignty he obtained from the power which then disposed of empires. Adrian IV. was an Englishman by birth, and, doubtless, he felt sympathies for his native land, of which Henry knew how to take advantage.

We read in Hanmer’s Chronicle, “Anno 1160, the king (Henry II.) cast in his minde to conquer Ireland; he sawe that it was commodious for him, considered that they were but a rude and savage people.” [3]

It was not until twelve years after that the Anglo-Normans invaded Ireland, and the Chronicles give us the following account of the occasion.

“Dermot, king of Leinster, having carried off the wife of O’Rourke, king of Meath, the latter complained to O’Connor, titular monarch of all Ireland, who instantly embraced the cause of the outraged monarch, and expelled the author of the wrong from his kingdom. Dermot, in his despair, went to seek aid from the English king. Henry II., gladly embracing the opportunity of accomplishing a design which he had long projected, promised to do Dermot justice.

“In a short time, Fitz-Stephen, and afterwards [I-5] Strongbow Earl of Pembroke, landed in Ireland with a numerous suite of Norman knights.

“Nevertheless, scarcely had Dermot introduced the strangers into his country, when, perceiving that he would not be restored to the possession of his states, he endeavoured to persuade Fitz-Stephen to return. But Fitz-Stephen replied, ‘What is it you ask? We have abandoned our dear friends and our beloved country; we have burned our ships, we have no notion of flight; we have already periled our lives in fight, and, come what may, we are destined to live or die with you.’ ” [4]

Dermot did not recover his crown, and the English remained in Ireland.

They remained there, but not without encountering endless opposition; for if their invasion was singularly easy, the completion of the conquest was a work of extraordinary difficulty.

The first invasion took place in 1169, and, according to the most authentic accounts, we must go down to the reign of James I., in 1603, to find the completion of the conquest. Thus, during more than four centuries, the English only exercised disputed dominion over Ireland.

The spectacle afforded by the native Irish and the Anglo-Normans, struggling to preserve their [I-6] country, the others to subdue it, must be interesting to all, but especially to Frenchmen.

These native Irish assailed, in their savage but haughty independence, all belonging to the same Celtic race, from which the Gauls, our ancestors, are descended.

And those Normans who invaded them left France in the preceding century. Their names are sufficient to reveal their origin—Raymond le Gros, Walter de Lacy, John de Courcy, Richard de Netterville, and a thousand others of the same sound. [5]

But the history of such distant times would exceed the limits of this introduction.

The author’s design, in the sketch he offers of this first epoch, (from 1169 to 1535,) is merely to give the reader some notions of the people invaded by the Normans; he is also anxious to point out the causes which rendered the invasion easy, and the conquest difficult.

It is not rare to find it alleged by English writers, that at the epoch of the conquest, Ireland contained a wretched, vile, and degraded population; an allegation probably inspired by the desire of imputing the misfortunes and corruption of this people to causes anterior to the English conquest. It is, [I-7] however, certain that nothing in the cotemporary records justifies such an assertion.

“Such,” says Campion, “is the character of the Irish; they are religious, sincere, violent in love and anger, compassionate and full of energy in misfortune, vain and superstitious to excess; good horsemen, passionately fond of war, charitable and hospitable beyond expression . . . They have acute minds, are desirous of instruction, and learn easily what they wish to study; they are persevering in labour,” [6] &c.

“When Robert Fitz-Stephen and the brave knights of Britain invaded Ireland,” says Hanmer, “they did not find cowards, but valiant men, brave both as horse and foot.” [7]

“The bodies and minds of the people,” says Sir John Davis, at a late period, “are endowed with extraordinary abilities of nature.” [8]

Now, how has it happened that this noble population has been surprised by a handful of adventurers? And how, thus invaded, has it for centuries resisted conquest,—too feeble to repulse its enemy, sufficiently strong in its reverses never to submit—equally incapable of enduring or shaking off the yoke—enduring the stranger in its territory [I-8] without ever losing the hope of his expulsion? How did it happen that these two populations, the one conquering and the other conquered,—the latter sometimes subdued, sometimes in rebellion,—the former always superior without being master—have lived together in a state of warfare for centuries,—either in a state of fierce warfare without one annihilating the other, or in a state of peace without mutual union.

Three principal causes facilitated the Anglo-Norman invasion of Ireland; first, the social and political condition of Ireland in the twelfth century; second, the still recent fact of the Danish invasion; and third, the influence of the court of Rome.

Sect. I.— Political Condition of Ireland in the twelfth century.

In the twelfth century the political organisation of Ireland was such that its social forces, infinitely divided, could be held together by no common bond. The four provinces, Leinster, Ulster, Munster, and Connaught, had each a separate king. [9] In truth, these four kings recognised one of their number as monarch of all Ireland, but his [I-9] supremacy was more nominal than real; besides, none of the four provinces having the privilege of conferring on its monarch the power of ruling over the rest, violent quarrels arose at the death of every sovereign, each of the four equal kings claiming the vacant monarchy. [10] The same elements of discord and anarchy which incessantly divided the four provinces externally, were also to be found in their internal condition.

For, as beneath the same monarch were placed kings who were his equals, though subordinate to him, so beneath the king of each province was an infinity of secondary kings and princes, who were also as equal, as independent, and as divided as their immediate superiors. [11] This fractional division of the social forces did not stop there. After the petty principalities came a multitude of clans, tribes, and families, all separated from each other, not only independent among themselves, but held by the feeblest ties to the sovereignty within whose sphere they were comprised. [12] Besides the inherent weakness arising from this indefinite subdivision [I-10] of public powers, there was in such a political state another source of exhaustion and ruin; to wit, the perpetual struggles which arose from this great number of equivocal sovereignties, of rights destitute of sanction, of authorities, rivals in fact, though nominally subordinate one to the other, and which incessantly produced opposing pretensions which could only be decided by war. [13] The chiefs of clans presented, within the narrow limits of their authority, the same spectacle of discord and anarchy as the petty princes above them, in less restricted bounds, and as the kings of the provinces in the wider circle of their power.

It may be easily conceived, that a country where the social forces were thus mutilated, and had no point of contact, save for mutual destruction, was of all countries the most favourable for the invasion of a conqueror. However powerful those forces might have been, collected in a mass, each of them was annihilated in isolation. Such was the state of Ireland at the epoch of the Anglo-Norman conquest.

[I-11]

Sect. II.— The still recent Invasion of the Danes.

Ireland, which has suffered so cruelly from conquest, was the last of the European countries conquered. At the time when the savage nations of the north sought countries to invade, Ireland, separated from them by two seas and one large island, long escaped their notice; the Romans disdained it, the barbarians knew it not. Gaul and England had been each stained by three invasions, while the soil of Ireland remained intact. Still, about the middle of the ninth century, the Danes, a people issuing from the forests of Scandinavia, landed in Ireland; they occupied a part of it without much difficulty; but the opposition to them became vigorous and obstinate. After a series of sanguinary combats, and alternations of victory and defeat, these stern conquerors abandoned the hope of founding an empire in the heart of the country, and limited themselves to the occupation of some points on the south and east coast of Ireland. [14] Dublin, formerly Dyvelin, Wexford, and Waterford, are Danish cities. [15] Thus, the [I-12] Irish, who had been sufficiently strong to check the Danes in their invasion, were too feeble to expel them completely; and at the moment when the Anglo-Normans came into Ireland, the Danes remained masters of all the east coast of Ireland, lived in a sort of tacit peace with the Irish, who were contented to see their conquerors confined to a narrow space, with the understood condition that they would not pass its limits.

However this may be, these struggles, maintained for three centuries, had exhausted the country, and increased the weakness of the body politic, already so great. [16]

The presence of the Danes on the Irish soil at this epoch diminished, for another reason, the strength of Ireland. The Anglo-Normans landed precisely in that portion of the country which was occupied by the Danes; consequently the Danes had to sustain the first shock of the Norman invasion. Now, it is impossible to imagine a more unfortunate circumstance for a country menaced by invaders. On one side the Danes, defending against the Normans a precarious and contested possession, could not display the zeal and devotion of a people summoned to the defence of their [I-13] country. [17] On the other side, the Irish, seeing the Anglo-Normans engaged with the Danes, their first assailants, fluctuated between the terror which the new conquerors inspired, and the satisfaction with which they beheld the destruction of an enemy established in their territory.

All these circumstances united, sufficiently show how Ireland, both social and political, must have been weak in resisting the Anglo-Norman invasion.

Sect. III.— Influence of the Court of Rome.

The third cause favourable to the invasion was, the influence, then all-powerful, of the court of Rome, which gave Ireland to the conquerors.

It was the time of the temporal and spiritual supremacy of the popes, the rivals of kings, the tribunes of the people in the middle ages; it was the time in which, when the most powerful prince resisted the court of Rome, the successor of St. Peter deposed him from his throne, and found the people submit to his decrees. At this time Ireland was eminent for its piety and sanctity amongst [I-14] the most Christian nations. Its priests were at the head of political as well as religious society. [18] In this country, where the social powers were feeble, uncertain, and ill defined, there was no fixed and invariable rule but that of religion,—no undisputed authority common to all but that of the priest. [19. $$] I find, in 1160, ten years before the Conquest, the Archbishop of Armagh regulating, as supreme arbiter, the quarrels of several Irish kings, between whom he alone could restore harmony. [20] Now, this clergy, supreme in Ireland, had for a quarter of a century been subject to the church of Rome. [21]

It was under such circumstances that Henry II. came to Ireland. He offered himself as a prince, the friend of peace and justice, who came not to strip the Irish of their rights, but to ensure their tranquil enjoyment of them; when he departs, he will leave their political power to the great, their domains to the proprietors, their spiritual authority to the priests, their country, their laws, and their institutions, to all. He only wants one thing, the title of Lord of Ireland, and he will [I-15] only avail himself of it to promote religion and morality; [22] and he claims not this great mission as his own; he has received it from Pope Adrian IV. and Pope Alexander III.; he seizes Ireland, not to satisfy ambition, but to obey the papal bulls. Religious Ireland, which at this period recognised the authority of the Romish church, could not receive harshly a monarch who presented himself to her with so solemn a mandate as that of the sovereign pontiff. Thus, all the great dignitaries of the Catholic church in Ireland were seen to proclaim the rights of the king of England. [23] It may well be conceived how this moral assistance of the clergy, the most powerful that could be directed against Ireland, must have protected an invasion already favoured by so many other causes.

Thus the social and political condition of the Irish,—the presence of the Danes in the midst of them,—their very religion,—all these causes combine to explain the facility with which the Anglo-Normans gained a footing in Ireland.

[I-16]

CHAPTER II.↩

We are now to inquire how, when the invasion was made without difficulty, the conquest could not be completed without perils continually renewed for centuries.

This fact is also explained by three principal reasons; the first equally derived from the political condition of the Irish; the second, from the relations between the Anglo-Normans and England; the third, from the condition to which the natives were reduced by the conquerors.

Sect. I.— Political condition of the Irish an obstacle to the Conquest.

I have just said that the indefinite division of the social forces in a country singularly facilitate an invasion; I shall add, that nothing is more adverse than this fractional partition to the permanent establishment of the victor in the conquered country. That which is, in the first instance, a source of weakness for the invaded country, becomes, in the second, the principal cause of its strength. In the same proportion as [I-17] it is difficult for the people resisting the invasion to unite suddenly all its divided elements of action; in the same proportion it is difficult for the conqueror to subdue, after invasion, this multitude of partial forces, spread here and there over a wide extent of territory, all of which bring to the struggle the same tribute of resistance, from the very fact of their being independent of each other.

It may be reasonably said, that a country in which the central power is strong, is at once the most difficult to invade, and that which after invasion presents the fewest difficulties to the conqueror. All the forces of the nation being assembled on a single point, offer a powerful condition of success, which once having failed, leaves the country without defence. It is just the contrary in a country where the national force is not concentrated; it is easy to invade, and difficult to conquer. This is distinctly seen in the first ages of our (French) history. The conquests of the men of the north, which so terribly succeeded each other, were only terminated when a power, feeble in its centre, but strong in its parts, was constituted in the land. Since the establishment of feudality in Europe, there have been several invasions, but there have been no conquests.

The Irish possessed very imperfect notions of the feudal system; but the division and dispersion [I-18] of the public power over the country, which is one of the characters of that system, belonged equally to their social state. This is the reason why the Danes so easily landed in Ireland, and yet could never establish themselves in the heart of the country. On the arrival of the Anglo-Normans, the same cause produced the same effects.

I believe that this social condition of the Irish injured the Anglo-Normans in the conquest of the country more than it served them in the invasion. For reasons already explained, they easily conquered a part of Ireland, but for several centuries they made vain efforts to complete their conquest. Down to Elizabeth’s reign, the conquered part never exceeded a third of all Ireland, and was often less. It was called the Pale, on account of the palisades or fortifications with which its borders were sometimes surrounded. The Pale was composed of part of Leinster and the south of Munster: sometimes a victory gained over the Irish tribes, sometimes a clever treaty concluded with one of their princes, extended the bounds of the Pale, which, on the other hand, were narrowed after every reverse of the Anglo-Normans. The conquerors often endeavoured to aggrandize the Pale by invasions in Ulster and Connaught, but they were regularly repulsed during four centuries. Even in that part of the island which we call the [I-19] Pale, their power did not cease to be contested during these four centuries, and history displays to us an uninterrupted series of Irish rebellions, bursting out sometimes at one point and sometimes at another, leaving to the conquerors not a single moment of repose or security. [24]

The Anglo-Normans were thus stopped short in their progress; the great interest of the Irish was to expel them from the space they occupied. But we shall soon see that the same cause which, after having aided the invasion of the Normans, checked their conquests, must have assisted them to preserve what they had acquired.

In fact, scarcely had they reached Ireland, when the Anglo-Normans established themselves as feudal lords in all the places of which they were masters. [25] The native Irish and the Anglo-Norman colony were then nearly balanced both in strength and weakness. When the Anglo-Normans wished to extend their conquests, they found scattered here and there among the native Irish an infinity of obstacles arising from their political condition; when, after having repulsed and discouraged their enemies, the Irish undertook to expel them from the countries forming the Pale, the weakness attached to the fractional character of their forces re-appeared; and [I-20] having become in their turn invaders of their conquerors, they failed before the Anglo-Normans, who, besides the advantage of resisting aggression, feeble, because they were divided, opposed to the Irish the same dispersion of social strength which is so powerful to resist an invasion. Each of the parties was strong when it defended its own territories, and weak when it attacked those of its adversary.

Sect. II.— Second obstacle to the completion of the Conquest: the relation of the Anglo-Norman conquerors to England, and of England to them.

The conquering population contained two very distinct elements; one party was composed of Norman lords, occupying a secondary situation in England, and who, arms in hand, came to seek in Ireland estates and higher rank; this was the feudal portion of the conquerors; it occupied the rural districts. In the train of the army came a crowd of adventurers of the lowest class, belonging to the British, Saxon, and Danish races, of which the latter had conquered the former, but all had been subdued by the Normans. These came to trade in Ireland, and settled in the cities. The first seized the ground, to live by the toils of the [I-21] natives reduced to vassalage; the second hoped to enrich themselves in the cities by industrial pursuits. Now, there was one fact which, though favourable to the country of the colonists, was eternally adverse to their establishment in Ireland—I mean the vicinity of England.

For colonists, whether they possess land or ships, it is a great element of success that they should be sufficiently distant from their native soil as to adopt the conquered land for their new country; that they should not have the wish nor the means of leaving it to return to their birthplace; that it should be as difficult to leave it as to reach it; and that, on setting their foot on the invaded soil, they should feel it necessary to become its masters for the future, or to lose their lives in the struggle. Unluckily, such was not the situation of the Anglo-Normans who came from England to Ireland. These emigrants never quitted home without a design of returning. Ireland was never their adopted country: they have always taken it in some sort on trial, and on the condition of separating from it if they were dissatisfied; to them the experiment, if unlucky, was not fatal; they escaped to return to England, where they always had their main interest. Nearly all the Norman lords who obtained land in Ireland [I-22] did not cease to be proprietors in England, [26] and with most of the merchants in the cities their Irish trade was only a branch of their commercial establishment in some English city. To the Norman lord, Ireland was a farm; to the British merchant merely an office; if both failed, they returned home without much loss. From this state of things it resulted, that a great number of the new inhabitants of Ireland had, at their arrival, an interest more or less great to quit it; and even when they remained, it was always with a resolution not to stay permanently; it was not an honest, definitive residence; when they gave themselves to Ireland, they did not cease to belong to England; hence the perpetual arrivals and departures from one country to another, which gave Ireland, not the appearance of an English colony, but of a place of pilgrimage; hence the absence of the proprietors of Irish lands, so often lamented, and against which the interests of the country and the English government struggled in vain; [27] hence came the passing population of colonists, succeeding each other with frightful rapidity, all bearing in their [I-23] breasts the same dislike for the new country, the same sympathies for the country they abandoned.

It is a portentous starting point for a new colony, when those who take possession of the land are not bound to it by strong ties, and, as I may say, rooted to the soil. The absolute necessity of living on the conquered land gives the conqueror greater energy to subdue it, and gives birth to more prudence, more justice, and more humanity, in his relations to the vanquished.

If the Anglo-Normans never completely subdued the Irish, if they were unjust and cruel in their government, is it not especially because they did not look upon themselves as linked, without hope of return, to the destiny of the conquered country, and that, seeing England always near as a friendly land, a refuge in case of shipwreck, they were never excited nor restrained in their actions by feeling that success was necessary, and failure without remedy?

The starting point of the Anglo-Norman population established in Ireland has had a marked influence on the destiny of the country.

When the Normans had conquered England, all the great vassals, having to struggle against the authority of the crown, adopted two principal means of increasing their strength; they formed a strict union amongst themselves, and they mingled [I-24] with the vanquished populations, in whom they found external support.

The Norman conquerors of Ireland had not a like interest to adopt the same course, because their king resided in England. Scarcely were they masters of a part of Ireland, when they divided amongst themselves, and commenced those deplorable struggles in which the interests of the country were absolutely sacrificed, and into which each of them merely carried views of personal aggrandisement. The strong castles which they constructed, both as residences and fortresses, became the theatre of private quarrels, in which the Normans exhausted against each other the forces which they should have reserved for the common enemy. Some possessed immense domains and great power; they lived almost like kings in the midst of their vassals; their fiefs were erected into palatinates; they created knights at their pleasure; and no authority had access to their domains, not even the officers of the king. [28] These great barons subdivided each of their possessions into an infinite number of sub-tenancies, making grants of land on the condition of military service, [I-25] just as the king had done to them. [29] Placed at a distance from the only supreme power which could control them, the great vassals, jealous of each other, because they were nearly equal, aspired mutually to destroy each other, and during three centuries Ireland was covered with blood, shed in support of these sad rivalries. The history of the conquest is entirely filled with the quarrels of the Butlers and the Fitzgeralds, who during four hundred years divided the colony. [30] Thus Ireland had scarcely escaped the first violence of the conquest when she fell into all the evils of feudal anarchy; [31] and feudal anarchy was more disastrous in Ireland than anywhere else, because the Norman vassals, far from their sovereign lord, gave [I-26] themselves up without restraint or reserve to all sorts of disorders and excesses. [32] It was a feudality without a king. Thus abandoned to the counsels of their own selfishness, the conquerors lost sight of the common interest; each consoled himself for seeing the power of all weakened, provided his own was augmented; and he who had extended his own domain cared little if the circle of English possession in Ireland was restricted. There was not a cause of increase for individuals which was not a cause of ruin for the mass. Strange situation! the vassals of the king of England were too distant to be restrained by his authority, and yet they were sufficiently near to demand assistance when it was required. Hence a sad consequence resulted; their tyranny, unrestricted by superior power, could be exercised with impunity over all the inhabitants of Ireland. They had a very feeble interest in rendering the population happy, whose aid against the king they did not absolutely require; and they could oppress that population without reserve, sure of royal aid to suppress any insurrection.

It may be easily seen how many obstacles to the [I-27] subjugation of Ireland arose from the situation of the conquerors relative to the native Irish. Other difficulties not less grave arose from their relation to England.

From the very first day of the invasion a violent collision was manifested between two interests widely distinct—the interest of the conquering Norman lords, and that of the king of England.

In order to attain their object, the complete subjugation of the invaded country, the Normans ought to occupy the land, reduce the natives to vassalage, and when once masters of the population, govern it with equity, mingle with it by slow degrees, and, in one word, preserve by peace and justice what had been obtained by all the violence and iniquity of war. It is only at this price that conquest, always founded on usurpation, can render itself legitimate in the course of time.

On the other hand, the English monarchs feared that if their Norman vassals formed too close a union with the Irish population, and were fused with them, a new people might arise from the mixture, sufficiently strong to assert its independence, and too close not to be formidable; they thought, on the contrary, that if the conquerors never ceased to be English, if they never united with the natives, but remained as intermediates between them and England,—if, in a word, they [I-28] remained simple colonists under the protection of the mother-country, then conquered Ireland would cause no alarm to England, but would become a valuable possession.

The entire evil has originally risen from this opposition of interests; the result was, that Ireland had a mixed government, half feudal and half colonial; the king was too distant to have the feudality well regulated,—the vassals were too powerful to have the royal colony obedient. This conflict between the English kings and their vassals continued during four centuries with various fortunes: in consequence of these vicissitudes, Ireland was sometimes led by the Anglo-Norman feudality, which, in the midst of all its evil passions, often yielded to the interest of all conquerors—that is, to mingle with the conquerors,—sometimes by the royal power, which feared that its supremacy could not be retained, except by preventing the union of the victorious and the vanquished.

Scarcely did Henry II. learn the prosperous issue of the invasion of Fitz-Stephen, and subsequently of Strongbow, than in his quality of king he claimed the advantages; and wishing to ensure his rights, he recalled his victorious vassals to England, forbade them to pursue the conquest, and, in order to complete it himself, went in person to Ireland.

[I-29]

We may well be surprised that Henry II., so jealous of maintaining his royal superiority over his conquering subjects in Ireland, should first have founded for their profit that feudal power which at a later period became the rival of his own. All the power of the barons, in fact, arose from the large grants of land which he made, or permitted them to make; but Henry acted thus because he could not act otherwise. [33]

A conquest was not effected in the middle ages as in the present. In our days, the prince who subdues a country garrisons it with a paid and permanent army; and whether he aids his subjects to become colonists, or leaves the possession of the soil to the natives, he remains, by means of his soldiers, master of the conquered country.

Nothing like this could occur at a time when a king possessed neither a permanent army nor soldiers properly so called. His military forces did not belong to him personally, but were furnished by his vassals, who, in return for grants of land, paid a military service restricted within [I-30] narrow limits. The feudal army could not be required by the king, save in determined cases. Compelled to support a defensive, it was not bound to an offensive, war. When a conquest was undertaken, all who accompanied the king submitted without doubt to feudal rule, but no one was bound to follow him; and when his vassals, in such a case, joined him, it was under the condition, expressed or understood, that the conquered country should be divided between all, according to the rank of each. Henry II. could not have conquered Ireland without his vassals; without them he could not preserve his conquests, and he could not pay their past services, nor ensure their future devotion, without bestowing lands; he granted them in all Ireland, with the exception of some royal reserves, [34] and on this condition he had an army. [35]

The difficulty was, to give them a power which he could not refuse, and at the same time preserve his own. Here we must repeat a fact which constantly presents itself in the history of Ireland, and which, however viewed, is always a misfortune or an embarrassment,—I mean the geographical position of Ireland with respect to England. [I-31] When we examined the condition of the Anglo-Normans in Ireland, whether as land-owners or merchants, we found nothing more adverse to them than the extreme vicinity of England. If we now consider it in another point, that of the royal interest, we shall find that Ireland, instead of being too near, was too distant. In truth, from the mere absence of the king, the vassals found themselves independent, and beyond the reach of royal authority; and it was commonly said that the king’s subjects in Ireland were more Irish than the Irish themselves. (Ipsis Hybernis Hyberniores.) 36] We have seen above what a sad use they made of this independence, and how they pursued their selfish designs in despite of the royal power. They had only one common interest in which they could agree with the king; that was, when the existence of the English colony was so menaced, that the vassals ran the risk of losing their estates, and the king his lordship. But when the Anglo-Norman possession was secured, the quarrel was renewed between the Normans, who, no longer having need of the king, evaded his power, [I-32] and the king, who, seeing the conquest secure, did not fear to weaken the conquerors.

Doubtless the king would have triumphed in the struggle, if he had been able, if not to reside permanently in Ireland, at least often visit it, to show his power. But we must remark, that from the time of the conquest to Elizabeth, that is to say, during the whole period embraced by our first epoch, the kings of England had not a single moment of political leisure, domestic or foreign. The domestic feuds of the Plantagenets, the wars with Scotland, France, and the barons, and, finally, the murderous contests of the houses of York and Lancaster, spent the blood and wasted the strength of England. None of the monarchs who succeeded each other during this terrible drama could, for the sake of his power in Ireland, leave England, where his life was not less menaced than his crown. [37]

Placed in the absolute impossibility of governing the Anglo-Irish colony themselves, the kings of England were forced to delegate their power to a deputy; but it was a further misfortune that they could never procure good delegates. Their representative, called sometimes viceroy, sometimes lord deputy, lord justice, or lord lieutenant, was, [I-33] in general, either too weak or too strong. If they selected one of the great vassals in Ireland, they did not find in him a willing instrument for the repression of the Norman lords. A great feudatory himself, he made common cause with his fellows, and turned against the king the arms with which he had been supplied to combat feudality. [38] If, to escape such a peril, the king chose a less considerable personage for his lieutenant, such as a simple knight, whose worth was merely personal, then this deputy, possessing only the royal confidence and his own merit, had no influence over the great vassals with whose government he was charged. [39]

Henry II., John, (when a prince,) and Richard II., are the only kings of England, who, during the four centuries succeeding the invasion, showed themselves in Ireland; and they only appeared there, being always called home by some interest superior to the peace of Ireland. “In 1395,” says an Irish historian, with great candour, “Ireland would have been assuredly conquered by [I-34] Richard II., had he not been called home to resist the Duke of Lancaster.” [40]

It is now evident that numberless obstacles, arising both from the relations of the Anglo-Normans to England, and from those of the English kings to the feudality established in Ireland, impeded the conquest of that country.

Sect. III. — Third obstacle to the Conquest; the condition imposed on the natives by the conquerors.

The great interest of the Anglo-Normans was, as I have already said, to unite as rapidly as possible with the natives, and to form with them a single community, completed by sentiments, ideas, and interests. Victory physically unites the conquerors and the conquered, but a moral alliance between them can alone give permanence to the conquest.

Now the first means that presents itself to conquerors for sowing among the vanquished the seeds of union and mutual sympathy, is to give the latter a share in the social and political advantages of the established government, and at once place them under the rule of a common equity. [I-35] But, whether through pride, selfishness, or weakness, the Anglo-Normans, during four centuries, adopted a contrary course of proceeding towards the native Irish.

No sooner were the Anglo-Normans established in Ireland, than they at once came into possession of the privileges and liberties peculiar to feudal society, which the kings of England had probably no inclination to dispute, even if they possessed the power. They had recognised rights, guarantees formally stipulated, and institutions as free in principles as those of England. Trial by jury was established in Ireland; laws were made in Irish parliaments, composed of Lords and Commons; and shortly after Magna Charta was proclaimed in England, its empire was recognised in Ireland. But when the Anglo-Normans received such liberties, they kept them to themselves, and did not extend their benefits to the Irish population subject to their sway.

The vanquished population, amongst whom the national spirit was deeply rooted, naturally felt no disposition to take the new law of the conqueror; it clung to its ancient traditions and old customs, and perhaps it would have taxed the utmost efforts of the conquerors to obtain the adoption of their laws. But instead of labouring to give such laws, the Anglo-Normans, or rather the kings of England, [I-36] whom they were forced to obey, were absolutely opposed to the introduction of English law. [41]

We have seen already the interest which the English king had in preventing the union of the Anglo-Normans with the native Irish, which he feared to see become too strong, and the division of whom was weakness.

The Norman barons, on their side, who committed the greatest disorders, and severely oppressed the native population, were interested in preventing the sufferers from appealing to English law for protection against their outrages. [42]

[I-37]

Thus, after the first chaos of invasion, the Anglo-Norman population and the native Irish, instead of displaying a tendency to unite, ceased not to form two separate communities, having each its distinct government and its own laws. [43]

This separation established by law in political society was introduced into the cities by municipal regulations.

Immediately after the conquest, Anglo-Norman populations were established in the Irish towns: these settlers came for the purposes of commerce and industry, and they failed not to procure for themselves the monopoly of both. These towns successively obtained charters which granted them certain [I-38] privileges, and constituted them municipal corporations.

As the exclusive interest of a town composed of merchants is a commercial interest, it may be easily understood that the municipal corporations of Ireland were commercial corporations. Now, these corporations followed the inclination natural to all privileged bodies, which is an exclusive tendency.

The Anglo-Norman towns had doubtless an interest in trading with the natives, but they had from the beginning a double interest to exclude the Irish from their walls; first, because this exclusion was ordained by statute, and they could not with impunity break the law; secondly, because to admit a new citizen within their precincts was generally to admit a new commercial rival. So that though they were compelled to form commercial relations with the natives, they took care that they should not share in their commercial privileges.

Still such is the irresistible sympathy which leads the best separated populations to unite, that in spite of all these obstacles, the Irish and the conquerors made several efforts to approximate; and as the English law did not permit the Irishman to become an Anglo-Norman, the Anglo-Norman became an Irishman: the vanquished being unable [I-39] to receive the laws of the victor, the conqueror took those of the conquered.

[44]It was attempted to check this tendency by the Statute of Kilkenny, ( &ad; 1366, Edward III.,) an act memorable in the dark annals of Irish legislation. This law provided that marriage, fosterage, [45] or gossipred [46] with the Irish, or submission to the Irish law, should be considered and punished as high treason. It declared that if any man of English descent should use an Irish name, speak the Irish language, or observe Irish customs, he should forfeit his estate, until security was given for his conformity to English manners! It was [I-40] also declared penal to present a mere Irishman (that is, one not of the five bloods, [47] or who had not purchased a charter of denization) to any benefice, or receive him into any monastery. And finally, it was strictly forbidden to entertain any native bard, minstrel, or story-teller; or to admit an Irish horse to graze on the pasture of a liege subject.

These proscriptions were not idle menaces; in the reign of Edward IV., Fitzgerald Earl of Desmond, one of the greatest of the Anglo-Norman barons, was condemned to death, and executed, for having married a wife of Irish blood. [48]

Thus the link destined to unite the conquerors and the vanquished was broken so soon as it was formed.

The policy of England opposed equally to the Irish becoming English, and to the English mingling with the Irish, compelled the vanquished to become enemies. They remained such, and after a thousand submissions, simulated or sincere, they [I-41] incessantly renewed their struggles, which, though inadequate to establishing their freedom, rendered the triumph of the conquerors singularly precarious and insecure.

Two facts prove, better than the most laboured reasoning, the sad effects of the plan adopted by the English for the government of Ireland.

In 1406, three hundred years after the invasion, the Irish made war at the gates of Dublin, and ravaged with impunity the suburbs of that city: in the middle of the reign of Henry VIII., when that prince was at the height of his power, the extent of the Pale was limited to a radius of about twenty miles. [49]

SECOND EPOCH. From 1535 to 1690.

CHAPTER I. RELIGIOUS WARS.↩

What four hundred years could not effect, we shall see accomplished in a century—the complete conquest of Ireland. Henry VIII. commenced the work, Elizabeth and Cromwell finished it. Three despots of such a stamp were not likely to wish [I-42] the same thing without effecting it, and each of them desired ardently, though for different reasons, the conquest of Ireland. It is not the achievement itself that deserves our attention, so much as the causes which produced it, and the consequences which followed. Until then, Ireland had only been to England an object of secondary consideration; how did it suddenly become the principal object of English policy? Elizabeth expended on its conquest all the treasures of England: Cromwell displayed in its reduction all the resources of his valour and intense will; and when the great reliligious and political drama, which, during the seventeenth century, so fearfully agitated England and the entire world, came to a close, Ireland was the theatre of the combat; the problem of English liberty or servitude was solved on the banks of the Boyne.

Ireland was conquered—all the Irish insurrections stifled; henceforth there is but a single law in Ireland, that of England; there is no more a Pale, no more Irish provinces distinct from the colony; all becomes English Ireland, and every inhabitant is equally subject to the English sovereign. How does it happen that this contest, instead of preparing a union between the conquerors and conquered, establishes between them a new and larger separation, renders hereafter a compact [I-43] union impossible, and plants in the breasts of both parties germs of mutual hatred, which have only been further developed by the course of years and ages!

The solution of these questions is found in a single fact, which is, as it were, the soul of this entire period, and the key of all Irish miseries; I mean the opposition which was then established between the religious creed of the conquerors and the vanquished.

Sect. I.— How, when England became Protestant, it must have desired that Ireland should become so likewise.

The philosophic and religious movement which, in the sixteenth century, terminated in the Reformation, and produced such an immense effect in England and Scotland, did not reach Ireland: whilst England and Scotland became protestant, Ireland remained catholic.

From the first moment of its appearance on the stage of the world, the doctrine of Luther had divided nations, and this separation was not accidental.

Although the theory of the innovators was very far from freedom, it had been forced, if not to give it birth, at least to invoke its name, and that was [I-44] sufficient to ensure the Reformation a natural sympathy among populations in possession of free institutions, whilst the countries subject to despotism naturally rejected a worship sprung from free examination, and attached themselves more closely than ever to the ancient faith, which was based on authority.

This, united with several other causes not connected with my subject, explains why France and Spain continued linked to the court of Rome, whilst England and Scotland separated from it. The religious dispute of the sixteenth century was not merely a dispute of ideas and creeds, struggling with each other in the arena of intelligence and faith; it was a political war of nations; it was a solemn contest between the principle of authority represented by the immovable power of the court of Rome, and the liberty of which the Reformation was the symbol.

I have already said that England took the side of the Reformation; hence the chief cause of the misfortunes of Ireland during the period which occupies our attention. England having become protestant, must have wished that Ireland should become so likewise, and this was to wish an impossibility.

England must have wished it; and, in fact, the spirit of proselytism which then animated the [I-45] christian world, was not less ardent with her than the other countries of Europe. Her reformers were as enthusiastic and intolerant as the Catholics whom they had conquered; and religious fanaticism by itself would have impelled the English to attempt the conversion of Ireland; but they had, in addition, an imperious political reason: if they did not impose the reformed faith on Ireland, they had reason to fear that Ireland would re-establish the Catholic church. Whilst they stigmatised the Romish creed with the names superstition and idolatry, the Catholics repulsed the reformed doctrine as heretical and impious. In this season of ardent faith, one church could only be preserved by the destruction of the other. In truth, Ireland in the sixteenth century was not formidable to England except on account of foreigners. Scarcely had the great quarrel between Protestantism and Catholicism burst forth in Europe, when Ireland became the aim of all the Catholic countries, eager to overthrow Protestantism in England. It was the hope of the court of Rome, and the centre to which the intrigues of the Papacy, Spain, and France, tended. From the very beginning of the Reformation, the sovereign pontiff indicated his reliance on Ireland, by circulating an old prophecy, intimating that the throne of St. [I-46] Peter would not be shaken so long as Ireland remained Catholic. [50]

Thus, though England had been led, by intolerant passions, to combat the Catholic religion in Ireland, it would have been compelled to the effort by care for its own defence, and interest in its own liberties.

But I have said, that in wishing to render Ireland Protestant, England desired an impossibility, and this is easily demonstrated. [51]

Sect. II.— Of the Causes that prevented Ireland from becoming Protestant.

After the long night of the middle ages, light had suddenly sprung up amongst all the nations of Europe, and society had made rapid progress everywhere, [I-47] except in Ireland, where the civil strife of the conquest having been perpetuated, everything remained stationary.

In the midst of a political chaos and a moral anarchy, faith in the Catholic and Romish church had alone remained in the creed of the Irish people. This faith reigned in absolute sovereignty over their minds, without any other idea to divide its empire. [52] Whilst the successive efforts of a philosophical spirit prepared Europe for religious reform, Ireland, in a remote corner of the world, distant from every intellectual movement, was still safe from doubt; she had learned nothing of Wycliffe or Huss; she had not heard the mutterings that preceded the eruption of the volcano; she had seen none of the brilliant flashes which heralded the great conflagration of the sixteenth century.

Of all European countries, Ireland was consequently the most attached to its ancient creed, and the least capable of comprehending the new religion which the English wished to establish.

It must be added, that had these dispositions been different, the Reformation presented itself [I-48] under such circumstances that it could not be accepted.

Who, in fact, brought to Ireland a creed which the country neither desired nor comprehended? It was brought by a people with whom the country had been at war for four hundred years, by a people whom it hated as a mortal foe, and from whose yoke it still hoped to escape. It might be said with confidence, that if the Irish were inclined to reform their faith, this attempt of England would have prevented them; under existing circumstances, it would only be an additional motive to combat an adversary, who not only wished to conquer the country, but to impose upon it a religion.

Besides, when the monarchs of England invited the Irish to shake off the yoke of Rome, they found themselves in a dilemna, which must have invited the Irish to resistance, if they had not been impelled by more serious motives. It was from the pope that the English monarch had originally received his rights; how then could he contest the power from which he held his sovereignty? how throw doubt on the spiritual authority of the pope, whose temporal power had not been contested when it was exerted to bestow a kingdom?

The enterprise of England was clearly impossible. Thus the despotism of the Tudors, which established the Anglican church in England, only [I-49] revolted Ireland. Henry VIII. and Elizabeth seized all the monasteries, greedily confiscated all ecclesiastical wealth, commanded the use of the Anglican ritual in all the Catholic churches, [53] subjected [I-50] to severe penalties those who absented themselves from church, and made the oath of supremacy necessary for sharing in all acts of social and political life. They had acted the same way in England, but the two countries were in a different [I-51] position. After the sanguinary wars of the Roses, the English wished, at all hazards, to give their monarchs power, which indeed they were capable of taking by force. Religious supremacy could not be refused to Henry VIII. without diminishing his royal authority, of which it formed a part, and to this the English people had no inclination. It was quite the contrary with the Irish, who, far from seeking to strengthen the power of the English monarch, were eager to escape from it, and eagerly seized an additional reason for detesting it. Thus, while Henry VIII. and Elizabeth established the reformed faith in England, according to their will and pleasure, all their efforts to fix it in Ireland terminated in three or four insurrections against England, to which, without doubt, the national sentiment was no stranger, but which, nevertheless, were principally derived from the new source of hatred springing from religion. [54]

Ireland was, in truth, subdued by Elizabeth. [55] This princess, in less than ten years, spent three millions and a half of money, an immense sum for [I-52] the sixteenth century; and lost an incalculable number of her bravest soldiers in effecting this conquest. But the result of the submission of Ireland was the cessation of the war, not the adoption of the Anglican worship. Perhaps it might have been foreseen that the Irish, whilst submitting to civil and political laws, would retain their religious creed and worship; for it is the natural disposition of man, when he undergoes physical violence, to take refuge in his soul, and proclaim himself free there, while his body is loaded with chains.

The first efforts of despotism had been vain; the Irish retained only the recollection of the tyranny; they remembered that, to conquer them and change their worship, Elizabeth had waged a cruel war, followed by frightful famine and destructive plague. [56]

The Stuarts ascended the throne of England; [I-53] the English became more protestant, because they suspected that their rulers were not so. The Irish, on the contrary, believing the Stuarts Catholics, were encouraged to remain such. This is the reason why, after Charles I, the Irish, who hated the English, generally loved the king of England. The fear of fines, the dread of confiscation, the terror of imprisonment, often produced external conformity to the English worship in the towns; all those who executed any public, even a municipal office, were obliged under heavy penalties to comply with the English ritual; [57] finally, there was always a current of new comers from England, who were Protestants when they arrived, and remained what they were. Nevertheless, in consequence of political events, the English government which imposed this worship lost its power in Ireland; the English settlers, as well as the Irish natives, abandoned the Anglican church, and spontaneously returned to the Catholic religion. This happened after the death of Elizabeth, to whom James I. succeeded, a monarch believed in Ireland favourable to catholicism. [58] It [I-54] was the same under Charles I. in 1642, when the population believed it possible to take up arms against the English parliament, and at the same time remain faithful to the king. Even during the periods of tranquillity and submission, observance of the Anglican worship was with difficulty obtained from the English inhabitants of the towns themselves. During Elizabeth’s reign, the greatest persecution of the Catholics was the prohibition of their own ritual; no serious efforts were made to enforce the adoption of that of England. James I. was more enterprising without being more fortunate. During his reign it once happened that the town of Galway could not find a mayor willing to take the oath of supremacy; [59] and Chichester, viceroy of Ireland, [60] giving an account of the vain efforts he had made to bring over some leading personages to the Anglican church, whose conversion was eagerly desired, depicted very accurately the state of the country when he declared that the atmosphere and even “the soil of Ireland were tainted with popery.”

[I-55]

Such was the state of affairs in Ireland, that the reformed religion could not be supported by a regular and durable persecution. Circumstances necessarily and suddenly led to a general war. In England it was a struggle of parties so nearly balanced, that one was ultimately the master of the other; in Ireland it was an entire Catholic population driven to revolt when its religion was assailed.

Sect. III.— How England rendered Ireland Protestant—Protestant Colonisation—Elizabeth and James I.

It was impossible to convert Ireland to Protestantism, and yet it was necessary that Ireland should become Protestant.

This necessity was every day more imperious for England; for, besides its hatred against a religious and political principle hostile to its own, it feared Catholic Ireland, and the more, as its own liberties were disputed, and as the absolute governments of the continent formed many intrigues in Ireland to strike with the same blow the Protestant religion and the liberties of England.

The first means derived from persecution and war having failed, another was tried: wholesale confiscation; the expulsion of the Catholics from the Irish soil, and their immediate replacement [I-56] by Protestant colonists. This violent and odious means had nothing repugnant to the manners of the times; for confiscation and death had been at the bottom of all the political and religious quarrels from the time of Henry VIII.; it could only be said, that when tried on so vast a scale it was of difficult execution; for how could an entire population be driven from its natal soil? What was to be done with the people torn from their dwellings? How could all be massacred? If not massacred, how were they to live when plundered? And further, how could an entire people be found ready to take their place? It is not so easy as people think to practise injustice. Still the obstacles did not daunt the projectors.

The first attempt of this kind was made in the reign of Elizabeth. The genius of this queen discovered the object to be attained, and her tyranny easily adopted the means. Desmond’s revolt was the opportunity. [61] Near six thousand acres in the province of Munster having been confiscated, [I-57] proclamation was made in England, offering these lands to all who would take them on certain conditions, of which the first was, that not a single farmer or labourer of Irish birth should be employed on these lands. [62] About two hundred thousand acres were thus distributed to the new settlers of English descent. The old inhabitants of the soil, dispossessed of their domains, only found shelter in the depths of the forests, or on the uncultivated sides of the mountains.

The work begun by Elizabeth was continued by her successors.

In the reign of James I., the real or imaginary plot of the Earls of Tyrone and Tyrconnell, and Sir Cahir O’Dogherty, having been detected, the six northern counties which belonged to them, (as suzerains, [63]) Donegal, Tyrone, Derry, Fermanagh, [I-58] Cavan, and Armagh, were confiscated to the crown; rather more than half a million of acres were thus placed at James’s disposal. As, after Elizabeth’s first confiscation, several of the English on whom lands had been bestowed had not entered on the possession, James permitted the Scots on this occasion to share with the English in the division of the confiscated estates, under the pretence that they were nearer Ireland, but in reality through partiality for his countrymen.

The regulation of this new colony was not precisely similar to that which had served as a base for the first.

In Elizabeth’s colony, the occupant of the soil should be an Englishman—in that of James I., it was necessary he should be a Protestant of the Anglican church. [64]

Experience had consequently shown a defect in the first colony, which an effort was made to avoid in the second.

“The original English adventurers,” says Leland, “on their first settlement in Ireland, were captivated by the fair appearance of the plain and open districts. Here they erected their castles [I-59] and habitations, and forced the old natives into the woods and mountains, their natural fortresses: thither they drove their preys—there they kept themselves unknown, living by the milk of their kine, without husbandry or tillage—there they increased to infinite numbers by promiscuous generation, and there they held their assemblies, and formed their conspiracies without discovery.” (Lel. vol. ii. p. 431.)

To escape this peril, quite a different plan was adopted for the second plantation; the confiscated lands were given to the new settlers, on condition of their residing in the woody and mountainous part of the country, whilst the dispossessed natives were left free in the plains, where they would be more easily watched. A still more important innovation was made—the Irish whose lands were confiscated, and the new English settlers who had been intermingled in Elizabeth’s plan, were settled in distinct and separate districts. [65] It is from this colonisation that the city of Londonderry, founded by the corporation of London, arose; from it also dates the Scotch and Presbyterian settlement in Ireland; and this starting point of puritanism in Ireland is too important not to be demonstrated. [66]

[I-60]

James I. had made great advances in his iniquitous work, and he was so proud of his success that he had nothing more at heart than its continuance. The difficulty in his view was not to dislodge the natives and replace them by new settlers, for his wisdom had solved all the difficulties of execution; the obstacle was, that there were no more lands to confiscate; and though nothing was easier than to expel the Irish from their houses and estates, it was necessary to assign a motive for such conduct. The subtle spirit of James was not long at fault. This monarch, who, according to Sully, was “the wisest fool in Europe,” this pedantic spirit waged war against Ireland like a pettifogging attorney.

After ages of civil war and anarchy, there necessarily existed great uncertainty and confusion in the titles to estates in Ireland; no doubt many usurpations had been committed, but the chief defect in the titles was irregularity. Taking advantage of this irregularity, a trick well worthy his limited understanding, James resolved to deprive of [I-61] their lands all whose titles were not strictly regular, and seize them for the crown. In consequence, a crowd of lawyers, interested in the plunder by the hope of sharing the booty, [67] pounced upon Ireland like a flock of harpies, shook the dust from old parchments; and by their chicanery, their ingenuity in discovering flaws and errors of form, and their diligence in hunting out defects, real or imaginary, succeeded so well, that there was not a proprietor who enjoyed the shadow of security; the king obtained a vast number of estates, and was able to stock them with Protestant colonists in place of the Catholic proprietors so cleverly ruined.

Sect. IV.— Protestant Colonisation—Charles I.

James had discovered a tyrannical expedient, of which his successor, Charles I., did not fail to take advantage.

There was in Ireland one province which had hitherto escaped every attempt at colonisation, that of Connaught. The viceroy, Wentworth, afterwards Earl of Strafford, resolved to dispossess all [I-62] the inhabitants of this vast country, and confiscate it to the king, who might afterwards dispose of it at his pleasure. To accomplish this enterprise, he took with him judges and soldiers, the first to falsify the law, [68] the second to violate it. [69] Both agents admirably answered his expectations. The lawyers suddenly discovered that all the grants made by preceding kings to the actual proprietors or their ancestors were null and void, and that Connaught had no lawful proprietors but the king. It was not sufficient to discover the defect of titles, it was further necessary that the proprietors should recognise it, and withdraw; if they did not go of their own accord, they should be constrained to abandon their estates by force, and this was the business of the soldiers. Preceded by an imposing army, Strafford traversed the country, spreading terror everywhere, and receiving everywhere the most servile submission. Still, when he reached the county of Galway, Strafford was stopped in his progress by the resistance of the inhabitants: in this county, though bent under severe despotism, [I-63] there were still certain legal forms inherent in the government and the manners of the conquerors. A jury was empannelled in Galway to decide between the crown and the occupants of the land. Strafford spared no pains to obtain a verdict for the king. [70] Still the jurors found for the defendants. [71] This fact alone would be sufficient to prove that there are guarantees and protection in a jury, which will triumph over the chicanery of fraud and the menaces of force. When Strafford heard the verdict he flew into a passion—on his own authority he fined Darcy the sheriff 1,000 l. for empannelling an improper jury—he arrested the jurors themselves, and brought them before the Court of Star-chamber in Dublin, where each of them was sentenced to pay a fine of 4,000 l., and to acknowledge himself guilty of perjury on his knees. All had the courage to refuse this humiliating proposition. Some time after, Strafford wrote to Wandesford, another servant of Charles, and Strafford’s successor in the government of Ireland—

“I hope that I shall not be refused the life of Sheriff Darcy; my arrows are cruel that wound so [I-64] mortally, but it is necessary that the king should keep his rights.”

Darcy was not executed, but he died of severe treatment in prison. A new jury was summoned, which, under the salutary influence of terror, found that in all time the county of Galway, like the rest of Connaught, belonged to the king; and this sentence placed all the proprietors at the mercy of the king. [72] Trial by jury, though one of the most vital institutions, does not save a country from the insolence of despotism, when despotism is established; still a jury defends the citizens better than any other tribunal. If it yields to corruption, it surprises the people, who believed it independent; if it resists, and fails in its resistance, it does not save those whom it wished to protect; but, associated with their misfortunes, it renders their cause more popular, and the oppression which weighs upon them more striking. In either case it sets tyranny in bolder relief.

If we consult the sentence pronounced against Strafford by the parliament of England, we are led [I-65] to believe that the violence offered to the Galway jury was not the only nor the worst outrage of the kind committed by Strafford in Ireland. One of the reasons assigned for his condemnation was, “Considering that juries who had given their verdict according to their consciences have been censured in the court of Star-chamber, severely fined, sometimes exposed in the pillory, have had their ears cut off, their tongues pierced, their foreheads branded,” &c. [73]

Too happy to be able to please his English parliament by exercising his royal prerogative, Charles I. would have gladly plundered all the Catholics of Ireland, and bestowed their estates upon English Protestants, but even his tyranny in Ireland could not procure him pardon for his arbitrary government of England. To such a degree was popular indignation excited, that the tyranny towards Ireland was actually made a ground of complaint against Strafford. The royal authority was already greatly shaken ( &ad; 1640); the king then suddenly ceased from oppressing the Irish, whose support he was anxious to secure in case of a reverse. The entire project of colonisation was abandoned; the Irish were assured that there never was a thought of plundering them. When you see a Stuart just [I-66] towards Ireland, be well assured that his authority is tottering in England.

Sect. V.— Civil War—The Republic—Cromwell.

It may be said that from the moment when Charles I. no longer persecuted Ireland, and abandoned the great project of the time, to make it protestant at all hazards, he was no longer king of England.

Thenceforward the true sovereign was the parliament; it was no longer an English king nor his delegate that was at war with Ireland,—it was England herself, puritan and protestant England, no longer restrained in its hatred by a prince less the enemy of the Catholics than of the Puritans. England henceforth enters into close contact with Ireland, which had become more free in its hostility to England, since the king, who favoured the Catholics in combating the Puritans, lost his power.

Two terrible cries of destruction were raised; one in England, “War against the Catholics of Ireland!” The other in Ireland, “War against the Protestants of England!” It is difficult to say which of these clamours was first raised, just as when two armies meet eager to engage, it is often impossible to decide which has begun the battle.

[I-67]