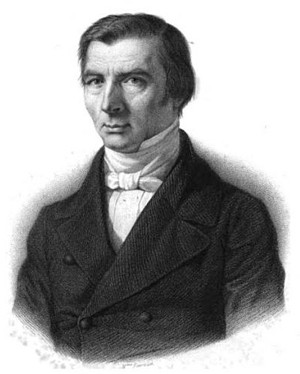

FRÉDÉRIC BASTIAT,

A Comparative Edition of his essay on "The State" (1848-49)

Frédéric Bastiat (1801-1850) |

|

[Created: 18 March, 2025]

[Updated: 29 March, 2025] |

Source

, A Comparative Edition of Frédéric Bastiat's essay on "The State" (1848-49). Translated, edited, and with an Introduction by David M. Hart (The Pittwater Free Press, 2025).http://davidmhart.com/liberty/FrenchClassicalLiberals/Bastiat/Books/1848-49-Etat/ComparativeEdition.html

A Comparative Edition of Frédéric Bastiat's essay on "The State" (1848-49). Translated, edited, and with an Introduction by David M. Hart (The Pittwater Free Press, 2025).

This work contains an analysis of the three editions of L'État which appeared between June 1848 and April 1849, and copies of them in French and English. They are:

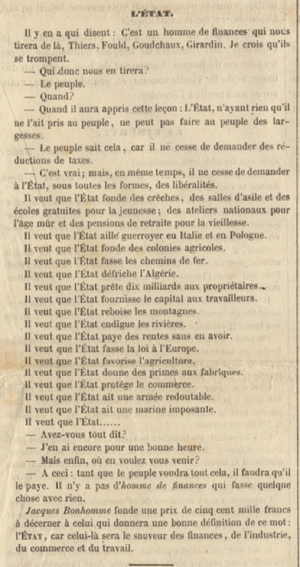

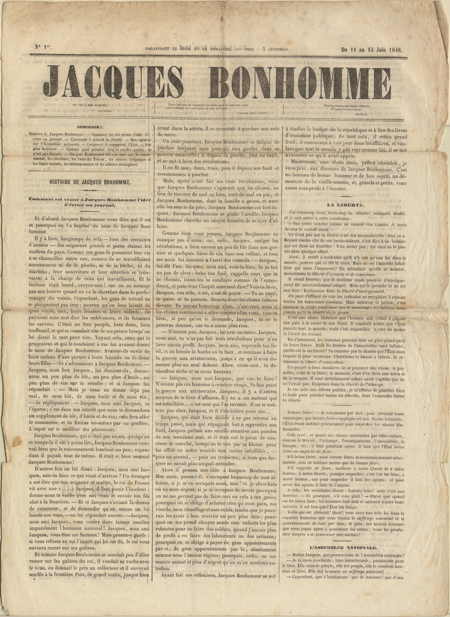

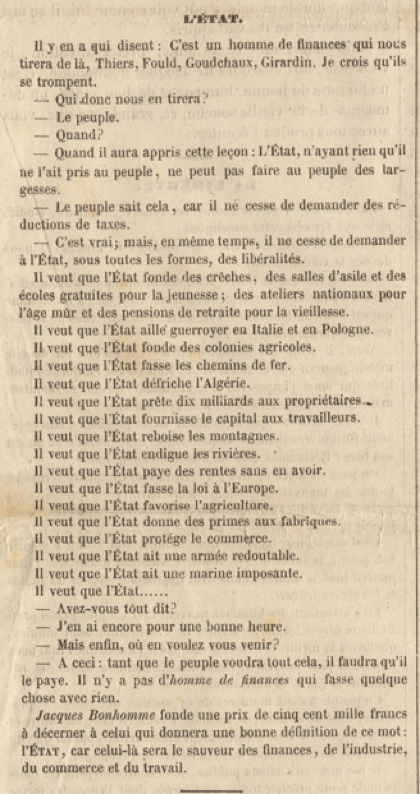

- T.212 “L’État” (The State), Jacques Bonhomme, no. 1, 11-15 June 1848, p. 2. OC, vol. 7, 59. pp. 238-40; CW2, pp. 105-6. First version has 376 words. The Institut Coppet has reprinted this essay in Jacques Bonhomme: L’éphémère journal de Frédéric Bastiat et Gustave de Molinari (11 juin – 13 juillet 1848). Recueil de tous les articles, augmenté d’une introduction. Ed. Benoît Malbranque (Paris: Institut Coppet, 2014), pp. 23-25. Page images and transcript in HTML.

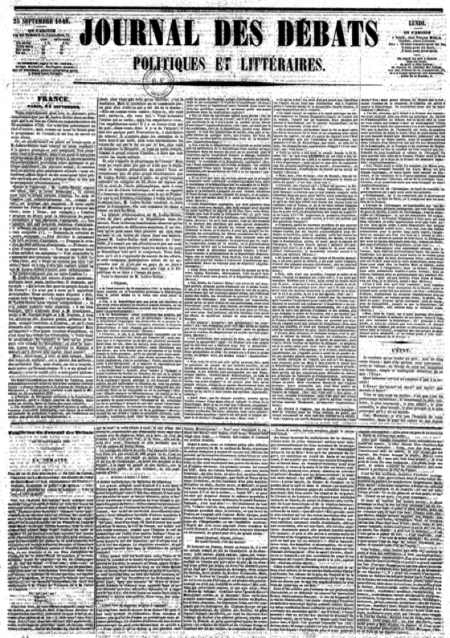

- T.222 “L’État,” Le Journal des débats politiques et littéraires (25 September 1848), pp. 1-2. Second revised and enlarged version has 2,400 words. [facs. PDF]

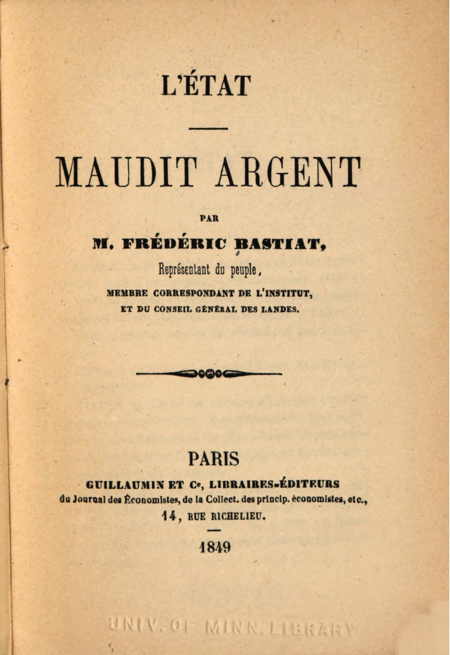

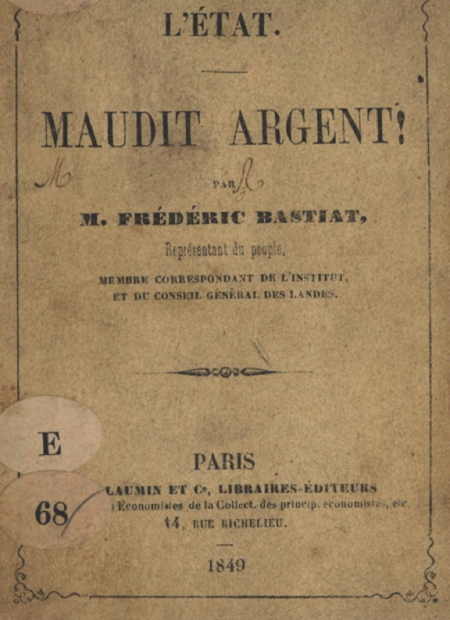

- T.320 A third revised and enlarged version with a new section on the Montagnards’ economic policies was published twice in 1849: as an article in Annuaire de l’économie politique et de la statistique pour 1849, par MM. Joseph Garnier et Guillaumin et al. Sixième année (Paris: Guillaumin, 1849), pp. 356-68; and in a pamphlet L’État. Maudit Argent (Paris: Guillaumin, 1849), pp. 5-23. The third version has 3,900 words. OC4, pp. 327-41; CW2, pp. 93-104. [facs. PDF]

This book is part of a collection of works by Frédéric Bastiat (1801-1850).

Table of Contents

A Comparative Edition of Frédéric Bastiat's essay on "The State" (1848-49)

Editor’s Introduction↩

The famous essay by Frédéric Bastiat on “The State” went through three extensive revisions and expansions between its first appearance as a very short article of about 400 words in a street magazine in June 1848 shortly before the June Days uprising, a second enlarged version of 2,000 words published in the up-market and prestigious Journal des débats in September 1848, [1]and its final version as a longer essay of 3,900 words in a pamphlet published sometime in April 1849 during the campaigns for the 13-14 May elections for the new National Assembly. [2]This third version is the one which is best known today.

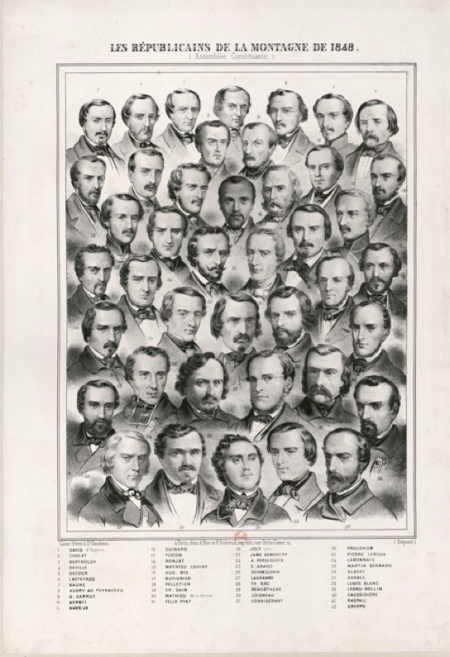

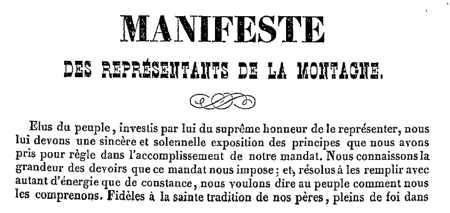

The two most most significant changes were a discussion of the new Constitution for the Second Republic which was being drawn up over the summer of 1848 and which Bastiat added to the JDD version; and then the inclusion in the 1849 pamphlet version of a new 900 word section in which Bastiat directly attacked the electoral program of the radical republican and socialist “Mountain” faction (“Les Montagnards”, and also referred to as the “Démocs-socs” (democratic socialists)) named after the radical Jacobin and Robespierre-ist group of the 1790s. [3]In the 1848 and 1849 elections the Montagnards were led by Alexandre Ledru-Rollin [4]who had been Minister of the Interior and a member of the Executive Commission in the Provisional Government until he was ousted by General Cavaignac during the period of martial law which was imposed after the June Days riots if 1848. Ledru-Rollin stood in the Presidential election on 10 December 1848 for the Montagnard socialist party, coming third with 5% of the vote behind General Cavaignac with 20% (the candidate Bastiat supported), and Louis Napoléon with 74%. In the elections for the Constituent Assembly (April 1848) and the Legislative Assembly (May 1849) the radical republicans and socialists went from 6% to 26% of the vote respectively. [5]It was in order to counter this expected increase in votes for the Montagnards in the May 1849 election that lead Bastiat to rewrite his pamphlet in the form we know today. Thus, this third version should be seen as part of Bastiat’s and the Guillaumin publishing firm’s anti-socialist campaign for which Bastiat would eventually write 12 pamphlets between June 1848 and July 1850. (See below for details.)

Although Bastiat was talking to three different audiences with each of his versions of the essay, they all were written in his very distinctive conversational and witty style which he had perfected in his series of “economic sophisms.” He talks directly to the reader in a very familiar style (using “tu” when he is talking to workers in the street using the voice of “Jacques Bonhomme”) [6]and half jokingly offers the reader a prize for the best definition of the state, the value of which ranged from 500,000 fr. to the working class readers of Jacques Bonhomme to 1,000,000 fr. to the more upmarket readers of the JDD (an amount which he continued to offer to the more mixed group of voters in April 1849) along with assorted “bells and whistles” to make it even more attractive. Frustratingly for his working class readers in June he does not provide his own definition of the state and leaves the matter hanging. However, in both the JDD and the 1849 pamphlet versions he offers his own definition in the meantime, until all the entries are in and a winner declared. This is his famous definition of the state and what it should NOT do:

| L’ÉTAT, c’est la grande fiction à travers laquelle TOUT LE MONDE s’efforce de vivre aux dépens de TOUT LE MONDE. | The state is the great fiction by which everyone endeavors to live at the expense of everyone else. | FEE translated this as: “The state is the great fictitious entity by which everyone seeks to live at the expense of everyone else.” (Selected Essays, p. 144.) | David Wells: “Government is the great fiction through which everybody endeavors to live at the expence of everybody else.” p. 160. |

He would also conclude both the JDD and the 1849 pamphlet versions with a brief statement of what he thought the State SHOULD do, which he modified only slightly between the two versions. In the 1849 version he adds the phrases “spoliation réciproque” (reciprocal plunder) and “garantir à chacun le sien” (guaranteeing each person what is theirs). The JDD version is on the left; the 1849 version on the right:

| “l’Etat (est) la force commune instituée, non pour être entre les citoyens un instrument d’oppression réciproque, mais au contraire pour faire régner entre eux la justice et la sécurité.” | “l’État (est) la force commune instituée, non pour être entre tous les citoyens un instrument d’oppression et de spoliation réciproque, mais, au contraire, pour garantir à chacun le sien, et faire régner la justice et la sécurité.” |

| “the state (is) the coercive power of the community, (which is) instituted not to be an instrument of reciprocal oppression of all of its citizens, but on the contrary to ensure the reign of justice and security among them.” | “the state (is) the coercive power of the community, (which is) instituted not to be an instrument of reciprocal oppression and plunder between all of its citizens, but on the contrary to guarantee to each person what is his and ensure the reign of justice and security.” |

In all three versions he draws up a list of the things the voters are demanding the state should do. These differ slightly as one can see from the comparative table below.

Comparative Table Listing the Things the People are asking the State to do

| JB version | JDD version | 1849 Pamphlet version |

|---|---|---|

| They want the state to found crèches, homes for abandoned children, and free schools for our youth, national workshops for those that are older, and retirement pensions for the elderly. | Set up harmonious workshops.Provide children with milk.Educate the young.Assist the elderly. | Set up harmonious workshops.Provide children with milk.Educate the young.Assist the elderly. |

| Organize work and the workers. | Organize work and the workers. | |

| They want the state to go to war in Italy and Poland.They want the state to lay down the law in Europe. | Liberate Italy | Liberate Italy |

| They want the state to have a formidable army.They want the state to have an impressive navy. | ||

| They want the state to support agriculture.They want the state to found farming colonies. | Carry out research into fertiliser and egg production.Set up model farms.Send the inhabitants of towns to the country. | Carry out research into fertiliser and egg production.Set up model farms.Send the inhabitants of towns to the country. |

| Repress the arrogance and tyranny of capital. | Repress the arrogance and tyranny of capital. | |

| They want the state to build railways. | Criss-cross the country with railways. | |

| They want the state to establish farming in Algeria. | Colonize Algeria. | Colonize Algeria. |

| They want the state to build embankments along the rivers. | Irrigate the plains. | |

| They want the state to replant the forests on mountains. | Re-forest the mountains. | |

| Regulate the profits of all industries. | Regulate the profits of all industries. | |

| They want the state to lend ten billion to land owners. They want the state to supply capital to workers.They want the state to pay interest on loans with money it doesn’t have. | Lend money | Lend money |

| They want the state to give subsidies to industry. | ||

| Encourage art and train musicians and dancers (for our entertainment). | Encourage art and train musicians and dancers (for our entertainment). | |

| Breed and improve riding horses. | Breed and improve riding horses. | |

| They want the state to protect trade. | Prohibit trade and at the same time create a merchant navy. | Prohibit trade and at the same time create a merchant navy. |

| Root out selfishness. | Root out selfishness. | |

| Discover truth and knock a bit of sense into our heads. The state has set itself the mission of enlightening, developing, enlarging, fortifying, spiritualizing, and sanctifying the souls of the people. |

Endnotes to the Introduction (1-6)

[1] Le Journal des débats (1789–1944) was founded in 1789 by the Bertin family and managed for almost forty years by Louis-François Bertin. The journal went through several title changes and after 1814 became Le Journal des débats politiques et littéraires. The journal likewise underwent several changes of political positions: it was against Napoléon during the First Empire; under the second restoration it became conservative rather than reactionary; and under Charles X it supported the liberal stance espoused by the Doctrinaires. Bastiat wrote 5 articles which appeared in the Journal: 2 letters to the editor in May 1846, a series of letters to Considerant which were late published as a separate pamphlet Property and Plunder (July 1848), a longer version of his essay on “The State” (25 Sept. 1848), and an essay on cutting the tax on salt in Jan. 1849. Gustave de Molinari was an editor of the journal in the 1870s. It ceased publication in 1944.

[2] Throughout this Introduction we will refer to these versions as the “JB version,” the “JDD version,” and the “1849 pamphlet version.”

[3] The Montagnards in 1848 were radical socialists and republicans who modelled themselves on “the Mountain” faction during the first French Revolution, the leader of which had been the lawyer Maximilien de Robespierre (1758-94). They were called “the Mountain” because they sat as a group in the highest seats at the side or the back of the Chamber. During 1848-49 the Montagnard group were also known as the “démoc-socs” (democratic socialists) and were led by Alexandre Ledru-Rollin. See also the glossary entry “Montagnards.”

[4] Alexandre Ledru-Rollin (1790-1874) was a lawyer, deputy (1841-49), owner of the newspaper La Réforme, Minister of the Interior of the Provisional Government of February 1848, and then member of the Executive Commission of the Provisional Government. He was removed from office by General Cavaignac during the period of martial law which was imposed after the June Days riots. On 12 June 1849 he organized a demonstration against President Louis-Napoléon’s decision to send French troops to Rome to assist the Pope Pius IX in his struggle agains the Italian republicans led by Mazzini. Following the military crackdown after the demonstration in order to escape arrest he fled to London where he spent the next 20 years in exile. He was able to return to France only in 1870.

[5] See “The Chamber of Deputies and Elections,” in Appendix 2: The French State and Politics, CW3, pp. 486-88.

[6] “Jacques Bonhomme” (literally Jack Goodfellow) is the name used by the French to refer to “everyman,” sometimes with the connotation that he is the archetype of the wise French peasant. Bastiat uses the character of Jacques Bonhomme frequently in his constructed dialogues in the Economic Sophisms as a foil to criticise protectionists and advocates of government regulation.

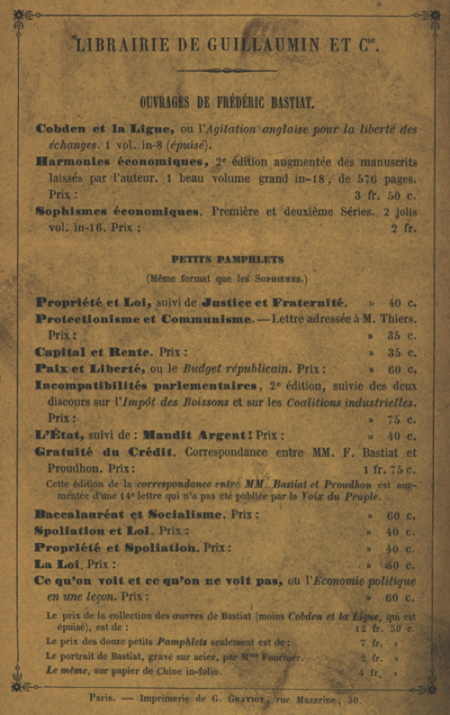

Bastiat’s anti-socialist “Petits Pamphlets”↩

The Guillaumin publishing firm would eventually publish Bastiat’s essay on “The State” (c. April, 1849) [7]along with a dozen or so similar anti-socialist pamphlets he wrote between the summer of 1848 and the summer of 1850. They marketed them as a collection they called “Petits pamphlets de M. Bastiat” (Mister Bastiat’s Little Pamphlets). [8]The titles, date of publication, and person or group being criticized in these essays is as follows:

- “Propriété et loi” (Property and Law), JDE, 15 May 1848, in CW2, pp. 43-59. Directed at Louis Blanc and critiques of property in general.

- “Justice et fraternité” (Justice and Fraternity) JDE, 15 June 1848, in CW2, pp. 60-81. Directed against Pierre Leroux.

- “Individualisme et fraternité” (Individualism and Fraternity) (c. June 1848), in CW2, pp. 82-92. Directed against Louis Blanc.

- “Propriété et spoliation” (Property and Plunder), (Journal des débats, 24 July 1848), in CW2, pp. 147-184. Directed against Victor Considérant and against critics of ownership of land and the charging of rent.

- “Le capital” (Capital), Almanach Républicain pour 1849 (1849). Written to appeal to ordinary people who were influenced by the ideas of Proudhon and Blanc concerning capital and the charging of interest on loans.

- Protectionisme et Communisme. Lettre à M. Thiers (Protectionism and Communism. A Letter to M. Thiers) (Jan. 1849), in CW2, pp. 235-65. Directed against the conservative and protectionist Mimerel committee whom Bastiat accused of adopting communist ideas.

- Capital et Rente (Capital and Rent) (Feb. 1849). Directed at Proudhon.

- “Madit argent!” (Damn Money!), JDE, 15 April 1849. Directed at general misperceptions about the nature of money.

- “L’État” (The State), (c. April, 1849), in CW2, pp. 93-104. Directed against the Ledru-Rollin and the radical “Montagnard” socialist faction in the Assembly.

- Gratuité du Crédit. Correspondence entrer MM. F. Bastiat et Proudhon (Free Credit. Correspondence between Bastiat and Proudhon) (Oct. 1849 - Feb. 1850). Directed against Proudhon.

- Baccalauréat et Socialisme (“Baccalaureate and Socialism”) (early 1850), in CW2, pp. 185-234. Written to oppose a bill before the Chamber in early 1850 on education reform which was supported by the conservative Adolphe Thiers.

- “Spoliation et loi” (Plunder and Law), JDE, 15 May 1850, in CW2, pp. 266-76. Directed against Louis Blanc and the Luxembourg Commission.

- La Loi (The Law) (Mugron, July 1850), in CW2, pp. 107-46. Against Louis Blanc and his 18th century predecessors including most notably Rousseau.

- Ce qu’on voit et ce qu’on ne voit pas, ou l’Économie politique en une leçon (What is Seen and What is Not Seen, or Political Economy in One Lesson) (July 1850), in CW3, pp. 401-52. Directed against all those who misunderstood the operation of the free market.

Bastiat wrote the last two pamphlets on “The Law” and “What is Seen and What is Not Seen” over the summer of 1850 when he probably knew he did not have long to live (he would die on Christmas Eve, 1850). Those two essays and his one on “The State” have become the essays for which Bastiat is perhaps fittingly best remembered.

Publishing and Translation History of “The State”↩

Publishing History

T.212 “L’État” (The State), Jacques Bonhomme, no. 1, 11-15 June 1848, p. 2. OC, vol. 7, 59. pp. 238-40; CW2, pp. 105-6. First version 376 words. The Institut Coppet has reprinted this essay in Jacques Bonhomme: L’éphémère journal de Frédéric Bastiat et Gustave de Molinari (11 juin – 13 juillet 1848). Recueil de tous les articles, augmenté d’une introduction. Ed. Benoît Malbranque (Paris: Institut Coppet, 2014), pp. 23-25.

T.222 “L’État,” Le Journal des débats politiques et littéraires (25 September 1848), pp. 1-2. Second revised and enlarged version 2,400 words.

T.320 A third revised and enlarged version with a new section on the Montagnards’ economic policies was published twice in 1849: as an article in Annuaire de l’économie politique et de la statistique pour 1849, par MM. Joseph Garnier et Guillaumin et al. Sixième année (Paris: Guillaumin, 1849), pp. 356-68; and in a pamphlet L’État. Maudit Argent (Paris: Guillaumin, 1849), pp. 5-23. The third version is 3,900 words. OC4, pp. 327-41; CW2, pp. 93-104.

Translation History

The first English translation (of the third version) appeared under the title “Government” in an anonymous translation published in 1853: Essays on Political Economy. By the Late M. Frederic Bastiat, Member of the Institute of France (London: W. & F.G. Cash, 1853). It contained “Capital and Interest,” “That Which is Seen, and That Which is Not Seen,” “Government” (Part III, pp. 3-19), “What is Money?, and “The Law. This was republished as a special “People’s Edition” (“expressly for the use of our British workmen”) by Provost & Co. in 1872.

An American edition by David Wells appeared in 1877: Essays on political economy. English translation Revised, with Notes by David A. Wells (G.P. Putnam Sons, 1880). First ed. 1877. It contains “Capital and Interest,” pp. 1-69; “That Which is Seen, and That Which is Not Seen,” pp. 70-153; “Government” (The State), pp. 154-73; “What is Money?” (Damned Money), pp. 174-220; “The Law,” pp. 221-91. Wells states that he revised the earlier anonymous English translation which he described as “exceedingly imperfect, and in some cases absolutely without meaning” (p. x).

The Foundation for Economic Education made a new translation by Seymour Cain in 1965: “The State,” in Selected Essays on Political Economy, translated from the French by Seymour Cain. Edited by George B. de Huszar (Irvington-on-Hudson, New York: The Foundation for Economic Education, 1968) (1st edition D. Van Nostrand Company, Inc. 1964. Copyright William Volker Fund), pp. 140-51.

The first and third versions of “The State” appeared in Liberty Fund’s 2012 translation: Frédéric Bastiat, CW2. “The State (draft)” (JB, 11 June 1848), in CW2, pp.105-6; and “The State”, in CW2, pp. 93-104 (this incorrectly cited the JDD as the source, which was in fact the 3rd Guillaumin pamphlet edition).

The JB version (11-15 June 1848)↩

Source

T.212 “L’État” (The State), Jacques Bonhomme, no. 1, 11-15 June 1848, p. 2. OC, vol. 7, 59. pp. 238-40; CW, vol. 2, pp. 105-6. First version 376 words.

The Institut Coppet has reprinted this essay in Jacques Bonhomme: L’éphémère journal de Frédéric Bastiat et Gustave de Molinari (11 juin – 13 juillet 1848). Recueil de tous les articles, augmenté d’une introduction. Ed. Benoît Malbranque (Paris: Institut Coppet, 2014), pp. 23-25.

Editor’s Note

During 1848 Bastiat and some of his more radical friends started two newspapers which they handed out on the streets of Paris in March and June. [9]They were written in the hope they could appeal to ordinary working people not to be seduced by the promises the socialists like Lous Blanc, [10]Victor Considerant, [11]Ledru-Rollin, and Proudhon [12]were making. The first was a daily, La République française, which first appeared the day after the February revolution began, and was edited by F. Bastiat, Hippolyte Castille, and Gustave de Molinari. It appeared from 26 February to 28 March in 30 issues. The second was a weekly called Jacques Bonhomme, which was founded by Bastiat, Gustave de Molinari, Charles Coquelin, Alcide Fonteyraud, and Joseph Garnier. It appeared approximately weekly with 4 issues between 11 June to 13 July; with a break between 24 June and 9 July because of the rioting during the June Days uprising.

The authorial voice in the journal Jacques Bonhomme was Jacques Bonhomme himself, the French everyman to whom Bastiat and the other economists were appealing. [13]The first issue (in which the first version of “L’État” appeared) begins with a brief history of Jacques and his role in French history. It then turns to commentary on current events by Jacques who sometimes speaks in the first person and at other times it is merely reported what he is thinking as he goes about Paris observing what is going on. In the first article on “Liberty” [14]Jacques begins by saying that “I have lived a long time, seen a great deal, observed much, compared and examined many things, and I have reached the following conclusion …”. He then proceeds to list the different kinds of liberty he believes in - freedom of belief and conscience, freedom of education, freedom of the press, the freedom of working (la liberté du travail), [15]freedom of association, and free trade. In the second article Jacques defends the idea of “laissez-faire.” [16]In the third article he talks about the many problems facing the National Assembly, especially the great financial difficulties France faced following the February Revolution when an economic recession occurred, unemployment rose, and tax receipts fell. [17]

The fourth article on “L’État” has to be seen as a response to the widespread popular belief that, if only a “financial expert” (un homme de finances) like ex-Prime Minister Adolphe Thiers, [18]the banker Achille Fould, [19]the new Minister of Finance in the Second Republic Michel Goudchaux, [20]or the successful press baron Émile de Girardin [21]were put in charge, they could solve France’s economic problems. Jacques believes that those who argue this are deceiving themselves. In his view, only the people themselves can solve France’s problems but only on the condition that they stop asking the state to do more things for them. They have to understand that the state cannot create wealth but only take from those who have created it. He then lists 16 things the people are currently demanding the state should do and concludes by saying that even financial experts cannot create something from nothing. Thus, in order to get people to truly understand what the State is, and what it can and cannot do, the magazine Jacques Bonhomme promises to offer a prize of 500,000 francs to the person who comes up with the best definition of “the State.” Jacques concludes that only with a correct understanding of this organisation can France’s financial and economic problems be solved, and thus the person who can do this will be “the savior of finance, industry, trade, and work.” This offer of a prize of course was not meant to be taken seriously as it was a huge amount of money at the time. [22]It was just part of Bastiat’s amusing rhetorical style. Unlike the two later versions of this essay Jacques does not offer his own definition of the state but leaves the issue hanging.

It should be noted that in the third issue of the magazine dated 20-23 June Bastiat published a direct appeal [23]to the Minister of Foreign Affairs, Alphonse de Lamartine, [24][25] and the Minister of the Interior and Montagnard socialist, Ledru-Rollin, to dissolve the National Workshops [26]which were being run out of the Luxembourg Palace by the socialist Louis Blanc, before they bankrupted the French nation. When they were finally closed down thousands of people took to the streets of Paris to protest the decision, thus starting the bloody June Days uprising of 23-26 June which was put down by the Army under General Cavaignac and lead to the imposition of martial law for the next four months. In his own election manifesto which he produced during the campaign for the May 1849 election Bastiat tells us that he took the dangerous step of plastering this article defending the closing of the National Workshops all over the walls of Paris and then was an eyewitness to the events that followed. In a letter to Julie Marsan dated 29 June 1848 (so just a fews later) he states that: [27]

| (I do not have the French version) | My only role was to enter the Faubourg Saint-Antoine after the fall of the first barricade, in order to disarm the fighters. As we went on, we managed to save several insurgents whom the militia wanted to kill. One of my colleagues displayed a truly admirable energy in this situation, which he did not boast about from the rostrum. |

Ten months later, in his “Profession de foi électorale d’avril 1849” (Statement of Electoral Principles) which he distributed in his electorate in Les Landes in April 1849 he explains in more detail that: [28]

| Convaincu qu’il ne suffisait pas de voter, mais qu’il fallait éclairer les masses, je fondai un autre journal qui aspirait à parler le simple langage du bon sens, et que, par ce motif, j’intitulai Jacques Bonhomme, Il ne cessait de réclamer la dissolution, à tout prix, des forces insurrectionnelles. La veille même des Journées de Juin, il contenait un article de moi sur les ateliers nationaux. Cet article, placardé sur tous les murs de Paris, fit quelque sensation. Pour répondre à certaines imputations, je le fis reproduire dans les journaux du Département. | Convinced that voting was not enough—the masses needed to be enlightened—I founded another newspaper which aimed to speak the simple language of good sense and which, for this reason, I entitled Jacques Bonhomme. It never stopped calling for the disbanding of the forces of insurrection, whatever the cost. On the eve of the June Days, it contained an article by me on the national workshops. This article, plastered over all the walls of Paris, was something of a sensation. To reply to certain charges, I had it reproduced in the newspapers in the département. |

| La tempête éclata le 24 juin. Entré des premiers dans le faubourg Saint-Antoine, après l’enlèvement des formidables barricades qui en défendaient l’accès, j’y accomplis une double et pénible tâche : Sauver des malheureux qu’on allait fusiller sur des indices incertains ; pénétrer dans les quartiers les plus écartés pour y concourir au désarmement. Cette dernière partie de ma mission volontaire, accomplie au bruit de la fusillade, n’était pas sans danger. Chaque chambre pouvait cacher un piège ; chaque fenêtre, chaque soupirail pouvait masquer un fusil. | The storm broke on 24 June. One of the first to enter the Faubourg Saint Antoine following the removal of the formidable barricades which protected access to it, I accomplished a twin and difficult task, to save those unfortunate people who were going to be shot on unreliable evidence and to penetrate into the most far-flung districts to help in the disarmament. This latter part of my voluntary mission, accomplished under gunfire, was not without danger. Each room might have hidden a trap, each window or basement window a rifle. |

One of the men addressed in his appeal of June 1848, Ledru-Rollin, will surface again in both the second and third versions of Bastiat’s essay as will be discussed below.

Endnotes to the Introduction to the JB version (9-28)

[9] See, “Bastiat’s Revolutionary Magazines,” in Appendix 6, in CW3, pp. 520-22, and the glossary entries on “La République française” and “Jacques Bonhomme (the journal).”

[10] Louis Blanc (1811-1882) was a journalist and historian who was active in the socialist movement. Blanc founded the journal Revue du progrès and published therein articles that later became the influential pamphlet L’Organisation du travail (1839). During the 1848 revolution he became a member of the provisional government, headed the National Workshops, and debated Adolphe Thiers on the merits of the right to work in Le socialisme; droit au travail, réponse à M. Thiers (1848). When his supporters invaded the Chamber of Deputies in May 1848 to begin a coup d’état in order to save the National Workshops from closing, they carried him around the room on their shoulders. He was arrested, lost his parliamentary immunity, and was forced into exile in England. Bastiat was one of the few Deputies to oppose the Chamber's treatment of Blanc.

[11] Victor Prosper Considerant (1808-93) was a follower of the socialist Charles Fourier and edited the most successful Fourierist magazine La Démocratie pacifiste (1843-1851). He was elected Deputy to represent Loiret in April 1848 and Paris in May 1849. The Fourierists advocated a utopian, communistic system for the reorganization of society. He was also an advocate of the “right to work” (the right to a job), an idea which Bastiat opposed.

[12] Pierre Joseph Proudhon (1809–65) was a political theorist whom many people consider to be the father of anarchism. He was elected to the Constituent Assembly in 1848 representing La Seine and tried to set up a “Peoples Bank” which would provide workers with low or zero interest loans. He is best known for his book Qu’est-ce que la propriété? (What is Property?) (1841), the answer to which he thought was“property is theft.” Proudhon and Bastiat engaged in a several month long debate on the morality of property, interest, and rent in late 1849.

[13] See the glossary entries on “Jacques Bonhomme (the person)” and “Jacques Bonhomme (the journal)”.

[14] "Freedom" (JB, 11-15 June 1848), in CW1, pp. 433-34.

[15] Economists like Bastiat believed in “la liberté du travail” (the liberty of working) in contrast to the socialists like Louis Blanc who advocated “le droit au travail” (the right to a job). See the glossary entry on “The Right to Work.”

[16] "Laissez-faire" (JB, 11-15 June 1848), in CW1, pp. 434-35.

[17] "National Assembly" (JB, 11-15 June 1848), in CW1, p. 451.

[18] Adolphe Thiers (1797-1877) was a conservative liberal lawyer, historian, politician, and journalist. During the July Monarchy he was briefly Minister for Public Works (1832-34), Minister of the Interior (1832, 1834-36), and Prime Minister and Minister for Foreign Affairs (1840). In 1840 he was instrumental in planning the construction of “Thiers’ Wall” around Paris between 1841-44. During the Revolution he wrote a book on property, De la propriété (1848) which Molinari critically reviewed in the JDE in January 1849. See the glossary entries on “Thiers” and “The Fortifications of Paris.”

[19] Achille Fould (1800–1867) was a banker and a deputy who represented the département of Les Hautes-Pyrénées in 1842 and La Seine in 1849. He was close to Louis-Napoléon, lending him money before he became emperor, and then served as Minister of Finance, first during the Second Republic and then under the Second Empire (1849–67). Fould was an important part of the imperial household, serving as an adviser to the emperor, especially on economic matters. He was an ardent free trader but was close to the Saint–Simonians on matters of banking.

[20] Michel Goudchaux (1797-1862) was the Minister of Finance 28 June to 25 October 1848. He supported a progressive tax on inheritance, a tax on capital invested in land, and the unpopular 45% increase in direct taxes in order to balance the budget. On the other hand he supported one of Bastiat’s favourite reforms, the uniform stamp for sending letters. He lost his position in a ministerial reshuffle on the eve of the Presidential election in November 1848 (which was won by Louis Napoléon).

[21] Émile de Girardin (1806-1881) was the first successful press baron of the mid-19th century in France. He began in 1836 with the popular mass circulation La Presse which had sales of over 20,000 by 1845. One reason for his success was the introduction of serial novels which proved very popular with readers. Girardin gradually turned against the July Monarchy on the grounds it was corrupt. In the 1848 Revolution he played a significant role in advising Louis Philippe to abdicate in February and then opposing General Cavaignac's repressive actions during the June Days riots. For the latter Girardin was imprisoned and his journal shut down. During the election campaign for the presidency he supported Louis Napoleon but ran afoul of him soon afterwards, selling his shares in La Presse in 1856. In his book, Le socialisme et l’impôt (1849) he argued that the state should be regarded as one big insurance company which insured the security and the property of the taxpayers and charged them a “premium” based on their wealth.

[22] This prize money was a huge amount as the average wage of a worker in Paris at the time 3 fr. 80 c. per day (or about 1,200 francs per annum). By contrast a professor in the Faculty of Medicine at the University of Paris earned between 2,000 and 10,000 francs per annum. See,[horace say], Statistique de l’Industrie a Paris résultant de l’enquête. Faite par la Chambre de commerce pour les années 1847-1848 (Paris: Guillaumin, 1851). “Chap. XXII. 13e Groupe - Imprimerie, Gravure, Papeterie” pp. 187-94, and Galignani’s New Paris Guide (Paris: A. and W. Galignani and Co., 1848), p. 76.

[23] "To Citizens Lamartine and Ledru-Rollin" (JB, 20-23 June 1848), in CW1, pp. 444-45.

[24] Alphonse de Lamartine (1790–1869) was a poet and statesman and as an immensely popular romantic poet, he used his talent to promote liberal ideas. Lamartine was elected Deputy representing Nord (1833-37), Saône et Loire (1837-Feb. 1848), Bouches-du-Rhône (April 1848-May 1849), and Saône et Loire (July 1849- Dec. 1851). During the campaign for free trade organised by the French Free Trade Association between 1846 and 1847 Lamartine often spoke at their large public meetings and was a big draw card. He was a member of the Provisional Government in February 1848 (offering Bastiat a position in the government, which he declined) and Minister of Foreign Affairs in June 1848. After he lost the presidential elections of December 1848 against Louis-Napoléon, he gradually retired from political life and went back to writing.

[25] Bastiat had earlier criticised Lamartine for being soft on socialism, especially the idea that people had “a right to a job.” See his “Letter from an Economist to M. de Lamartine. On the occasion of his article entitled: The Right to a Job” (Feb. 1845, JDE) and “Second Letter to M. de Lamartine (on price controls on food)” (Oct. 1846, JDE).

[26] See the glossary entry on the “National Workshops.”

[27] “Letter 104. Paris, 29 June 1848. To Julie Marsan,” CW1, pp. 156-57. See also,“Bastiat the Revolutionary Journalist and Politician,” in the Introduction to CW3, pp. lxviii-lxxiii.

[28] “Political Manifestos of April 1849,” CW1, p. 392.

JB version in French

L’État. 70. Il y en a qui disent : C’est un homme de finances qui nous tirera de là, Thiers, Fould, Goudchaux, Girardin. Je crois qu’ils se trompent.

— Qui donc nous en tirera ?

— Le peuple.

— Quand ?

— Quand il aura appris cette leçon : L’État, n’ayant rien qu’il ne l’ait pris au peuple, ne peut pas faire au peuple des largesses.

— Le peuple sait cela, car il ne cesse de demander des réductions de taxes.

— C’est vrai ; mais, en même temps, il ne cesse de demander à l’État, sous toutes les formes, des libéralités.

Il veut que l’État fonde des crèches, des salles d’asile et des écoles gratuites pour la jeunesse ; des ateliers nationaux pour l’âge mûr et de pensions de retraite pour la vieillesse.

Il veut que l’État aille guerroyer en Italie et en Pologne.

Il veut que l’État fonde des colonies agricoles.

Il veut que l’État fasse les chemins de fer.

Il veut que l’État défriche l’Algérie.

Il veut que l’État prête dix milliards aux propriétaires.

Il veut que l’État fournisse le capital aux travailleurs.

Il veut que l’État reboise les montagnes.

Il veut que l’État endigue les rivières.

Il veut que l’État paye des rentes sans en avoir.

Il veut que l’État fasse la loi à l’Europe.

Il veut que l’État favorise l’agriculture.

Il veut que l’État donne des primes à l’industrie.

Il veut que l’État protège le commerce.

Il veut que l’État ait une armée redoutable.

Il veut que l’État ait une marine imposante.

Il veut que l’État…

— Avez-vous tout dit ?

— J’en ai encore pour une bonne heure.

— Mais enfin, où en voulez-vous venir ?

— À ceci : tant que le peuple voudra tout cela, il faudra qu’il le paye. Il n’y a pas d’homme de finances qui fasse quelque chose avec rien.

Jacques Bonhomme fonde un prix de cinquante mille francs à décerner à celui qui donnera une bonne définition de ce mot, l’ÉTAT ; car celui-là sera le sauveur des finances, de l’industrie, du commerce et du travail.

JB version in English

The State

There are those who say: A financier will get us out of this—Thiers, Fould, Goudchaux, Girardin. I believe they are mistaken.

— Who then will get us out?

— The people.

— When?

— When they have learned this lesson: The State, having nothing except what it takes from the people, cannot bestow gifts upon the people.

— The people know this, for they constantly demand tax reductions.

— That is true; but at the same time, they constantly demand all sorts of benefits from the State.

They want the State to establish nurseries, daycare centers, and free schools for the youth; national workshops for working-age adults and retirement pensions for the elderly.

They want the State to wage war in Italy and Poland.

They want the State to establish agricultural colonies.

They want the State to build railways.

They want the State to clear land in Algeria.

They want the State to lend ten billion francs to property owners.

They want the State to provide capital to workers.

They want the State to reforest the mountains.

They want the State to dam the rivers.

They want the State to pay rent without having any revenue.

They want the State to impose its law upon Europe.

They want the State to support agriculture.

They want the State to grant subsidies to industry.

They want the State to protect commerce.

They want the State to maintain a formidable army.

They want the State to have an imposing navy.

They want the State to …

— Have you listed everything?

— I could go on for another hour.

— But where are you going with this?

— To this: As long as the people want all these things, they must pay for them. No financier can create something out of nothing.

Jacques Bonhomme establishes a prize of fifty thousand francs to be awarded to whomever can provide a good definition of the word THE STATE—for that person will be the savior of public finance, industry, commerce, and labor.

The JDD version (25 Sept. 1848)↩

Source

T.222 “L’État,” Le Journal des débats politiques et littéraires (25 September 1848), pp. 1-2.

Editor’s Note

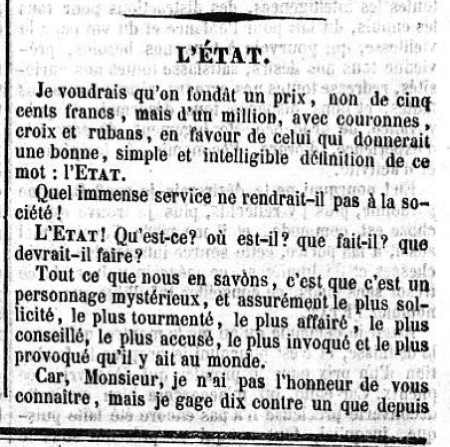

Three months after the first version of “LÉtat” appeared in print Bastiat’s expanded second version appeared in the prestigious JDD which was read by the intellectual and political elites. Here, Bastiat stops using the voice of Jacques Bonhomme but still uses his conversational style of writing, this time addressing his readers as “You, Sir” and “You, Madame.” He begins the essay with his offer of a prize instead of concluding with this as he did in the JB version, and the prize money has been doubled from 500,000 to the quite exorbitant figure of one million francs. Bastiat inserts some literary references, as was his want in the Economic Sophisms, [29]with quotes from Figaro, from Rossini’s opera “The Barber of Seville,” (one of which would be cut from the 3rd version of the essay). He then provides a slightly larger list of demands (now 18) the people are making of the State, and about half way through the essay he offers his own definition of the State for the first time.

This is followed by a comparison of the new constitution of the Second Republic which had been under discussion throughout the summer of 1848, and the American Constitution. The sticking point was the attempt by some socialist Deputies to have a clause in the constitution guaranteeing every French citizen the “right to work” (le droit au travail, which one might translate in English as the “right to a job” using “travail” as a noun). This had been a catch phrase of the socialists throughout the 1840s. What they meant by this term was that the state had the duty to provide work for all men who demanded it. In contrast, the classical liberal economists called for the “right of working,” or the “freedom to work” (la liberté du travail, or le droit de travailler using “travail” as a verb), by which they meant the right of any individual to pursue an occupation or activity without any restraints imposed upon him by the state. The latter point of view was articulated by Charles Dunoyer in his De la liberté du travail (1845) and by Bastiat in many of his writings. The socialist perspective was provided by Louis Blanc in L’Organisation du travail (1839) and Le Socialisme, droit au travail (1848) and by Victor Considérant in La Théorie du droit de propriété et du droit au travail (1848).

The socialists claimed that it was the duty of the government to provide every able-bodied Frenchman with a job and the job creation program initiated by the Constituent Assembly in the first days of the revolution, called the National Workshops, was designed to carry this out. Bastiat and the other Economists fiercely opposed this scheme and Bastiat used his position in the Chamber's Finance Committee to argue strenuously against it. Matters came to a head in May 1848, when a committee of the Constituent Assembly was formed to discuss the issue of “the right to work” just prior to the closing of the state-run National Workshops, which prompted widespread rioting in Paris. In a veritable “who’s who” of the socialist and liberal movements of the day, a debate took place in the Assembly and was duly published by the classical liberal publishing firm of Guillaumin later in the year along with suitable commentary by such leading liberal economists as Léon Faucher, Louis Wolowski, Joseph Garnier, and, of course, Bastiat. [30]Here is the beginning of the “opinion” Bastiat wrote for the volume, in which he distinguished between the right to work (droit au travail, where “work” is used as a noun and thus might be rendered as the “right to a job”) and the “right to work” (droit de travailler, where “work” is used as a verb): [31]

| Si l’on entendait par droit au travail le droit de travailler (qui implique le droit de jouir du fruit de son travail), il ne saurait y avoir de doute. Quant à moi, je ne crois pas avoir jamais écrit deux lignes qui n’ait eu pour but de le défendre. | If one understands by the phrase “right to a job” (droit au travail) the right to work (droit de travailler) (which implies the right to enjoy the fruit of one’s labor), then one can have no doubt on the matter. As far as I’m concerned, I have never written two lines that did not have as their purpose the defense of this notion. |

| Mais par droit au travail on entend le droit qu’aurait l’individu d’exiger de l’État, et par force, au besoin, de l’ouvrage et un salaire. Sous aucun rapport cette thèse bizarre ne me semble pouvoir supporter l’examen. | But if one means by the “right to a job” that an individual has the right to demand of the state that it take care of him, provide him with a job and a wage by force, then under no circumstances does this bizarre thesis bear close inspection. |

In spite of his and the Economists’ opposition Chapter 2, Article 13, of the Constitution of November 4, 1848 explicitly stated that: [32]

| La Constitution garantit aux citoyens la liberté du travail et de l’industrie. La société favorise et encourage le développement du travail par l’enseignement primaire gratuit, l’éducation professionnelle, l’égalité de rapports, entre le patron et l’ouvrier, les institutions de prévoyance et de crédit, les institutions agricoles, les associations volontaires, et l’établissement, par l’État, les départements et les communes, de travaux publics propres à employer les bras inoccupés ; elle fournit l’assistance aux enfants abandonnés, aux infirmes et aux vieillards sans ressources, et que leurs familles ne peuvent secourir. | “The Constitution guarantees citizens the liberty of work and industry. Society favours and encourages the development of work by means of free primary education, professional education, equality of relations between employers and workers, institutions of insurance and credit, agricultural institutions, voluntary associations, and the establishment by the state, the departments and the communes of public works suitable for employing idle hands; it provides assistance to abandoned children, to the sick and the old without means, which their families cannot help.” |

This article raised the problem which concerned Bastiat deeply of the difference between the free market idea of “the liberty of work and industry” (la liberté du travail et de l’industrie) and the socialist idea of the “right to a job” (la liberté au travail) which increasingly became an issue during the Revolution. The Constitution of November 1848 specifically refers to the former but also seems to advocate the latter with the phrase “public works suitable for reemploying the unemployed”. Other articles in the new Constitution which the economists opposed and tried to water down in the final version were Article VIII of the Preamble which asserted the duty of the French state to “to provide the means of existence to necessitous citizens” and Article 13 which promised “freedom of labor and of industry,” which was dear to the economists, but also promises of considerable financial assistance to the poor and the old, which was very dear to the socialists:

| VIII. - La République doit protéger le citoyen dans sa personne, sa famille, sa religion, sa propriété, son travail, et mettre à la portée de chacun l’instruction indispensable à tous les hommes ; elle doit, par une assistance fraternelle, assurer l’existence des citoyens nécessiteux, soit en leur procurant du travail dans les limites de ses ressources, soit en donnant, à défaut de la famille, des secours à ceux qui sont hors d’état de travailler. | Article VIII of the Preamble: “It is the duty of the republic to protect the citizen in his person, his family, his religion, his prosperity, and his labor, and to bring within the reach of all that education which is necessary to every man; it is also its duty, by fraternal assistance, to provide the means of existence to necessitous citizens, either by procuring employment for them, within the limits of its resources, or by giving relief to those who are unable to work and who have no relatives to help them.” |

| Article 13. - La Constitution garantit aux citoyens la liberté du travail et de l’industrie. La société favorise et encourage le développement du travail par l’enseignement primaire gratuit, l’éducation professionnelle, l’égalité de rapports, entre le patron et l’ouvrier, les institutions de prévoyance et de crédit, les institutions agricoles, les associations volontaires, et l’établissement, par l’Etat, les départements et les communes, de travaux publics propres à employer les bras inoccupés ; elle fournit l’assistance aux enfants abandonnés, aux infirmes et aux vieillards sans ressources, et que leurs familles ne peuvent secourir. | Chapter 1, Article 13: “The Constitution guarantees to citizens the freedom of labor and of industry. Society favors and encourages the development of labor by gratuitous primary instruction, by professional education, by the equality of rights between the employer and the workman, by institutions for the deposit of savings and those of credit, by agricultural institutions; by voluntary associations, and the establishment by the State, the departments and the communes, of public works proper for the employment of unoccupied laborers. Society also will give aid to deserted children, to the sick, and to the destitute aged who are without relatives to support them.” |

Bastiat refers to this debate in the JDD version of the essay by quoting the opening paragraph of the new French constitution which stated that: [33]

| “La France s’est constituée en République. En adoptant cette forme définitive de gouvernement, elle s’est proposée pour but de marcher plus librement dans la voie du progrès et de la civilisation, d’assurer une répartition de plus en plus équitable des charges et des avantages de la société, d’augmenter l’aisance de chacun par la réduction graduée des dépenses publiques et des impôts, et de faire parvenir tous les citoyens, sans nouvelle commotion, par l’action successive et constante des institutions et des lois, à un degré toujours plus élevé de moralité, de lumières et de bien-être.” | “France has been constituted as a Republic. By adopting this final form of government it has put forward the goal of advancing more freely down the path of progress and civilisation, to ensure a more and more just distribution of the burdens and advantages of society, to increase the comfort of each person by the gradual reduction of public expenditure and taxes, and to enable (faire parvenir) all citizens to achieve, without any new shocks, and by the steady and gradual action of (our) institutions and law, an ever increasing level of morality, enlightenment, and well-being.” |

Bastiat’s version of this which he quotes in the essay is:

| “La France s’est constituée en République pour… appeler tous les citoyens à un degré toujours plus élevé de moralité, de lumière et de bien-être.” | “France has been constituted as a Republic in order to call (upon) all the citizens to (achieve) an increasingly higher level of morality, enlightenment, and well-being.” |

What is interesting in Bastiat’s version is what he cut out (the clause dealing with cutting government expenditure and taxation - which he would have agreed with) and the verb he substituted for “faire parvenir” (to make or enable someone to reach or obtain something), namely “appeler” (to call or summon someone to do something). To use “faire parvenir” would have strengthened his argument against the socialists. Since the JDD version (Sept. 1848) was published before the promulgation of the new constitution on 4 November 1848 it is possible he was using a formulation used in an earlier draft.

In Bastiat’s view the French made the mistake of “personifying” the abstract notion of the state and believing that it could and should solve the people’s problems for them. By contrast, the Americans were under no such “illusion” as they stated in the opening lines of their constitution that “the people” established a state so they could have the liberty to go about solving their own problems as they saw fit.

Bastiat concludes by pointing out the contradiction this inevitably leads to:

| Il faut donc que le peuple de France apprenne cette grande leçon : Personnifier l’Etat, et attendre de lui qu’il prodigue les bienfaits en réduisant les taxes, c’est une véritable puérilité, mais une puérilité d’où sont sorties et d’où peuvent sortir encore bien des tempêtes. Le gouffre des révolutions ne se refermera pas tant que nous ne prendrons pas l’Etat pour ce qu’il est, la force commune instituée, non pour être entre les citoyens un instrument d’oppression réciproque, mais au contraire pour faire régner entre eux la justice et la sécurité. | Thus the people of France must learn this important lesson: to personify the State and to expect that it will dispense benefits while (at the same time) reducing taxes, is pure childishness, but it is a childishness from which have come and could well still come great turmoil. The abyss of revolutions will never be closed as long as we do not accept the state for what it is: the coercive power of the community, (which is) instituted not to be an instrument of reciprocal oppression of all of its citizens, but on the contrary to ensure the reign of justice and security among them. |

Perhaps unknown to Bastiat at the time he wrote the essay, his article would appear on the front page of the 25 September issue below a long article which reproduced the speech which the ex-Minister of the Interior and leader of the radical socialist Montagnard party, Alexandre Ledru-Rollin, had given the day before to commemorate the events of 22 September, 1792 when the Convention had proclaimed the First Republic. In it Ledru-Rollin talks about the historical connection between socialism and French republicanism and his hopes that socialism would again become an integral part of the policies of the Second Republic. In what might appear to be a direct response to Bastiat’s warnings about the limited funds of the French government and the growing demands being placed on it by the public, Ledru-Rollin argued there was a “river of money” available to the French state if only it would tap into it:

| Citoyens, que répond-on? “L’État est pauvre; la République ne saurait faire de telles fondations, car l’argent manque!” J’avoue que je n’ai jamais compris cette objection dans un pays aussi fertile, aussi puissant que la France! Je dis, moi, que les sources sont innombrables, et qu’il ne faut que savoir leur tracer des canaux pour les conduire vers le Trésor, et de là les faire refluer jusqu’au pauvre.” | Citizens! what do they say in response (to our demands)? “The State is poor; the Republic could not be built on such foundations because we lack the money.” I confess I have never understood this objection in a country as fertile, as powerful as France! As for me, I say that the sources (of wealth, or sources of this river of money) are uncountable, and that we only have to know how to lay out the canals which will lead (these waters) to the Treasury, and from there to make them flow to the poor. |

Although Bastiat also uses in his essay the metaphor of the State opening up “une source” (spring) in order to flood the country with benefits he does not seem to be aware of these remarks by Ledru-Rollin at this time. Ledru-Rollin was probably already campaigning for the Presidential election which would be held in 10 December 1848. He was the head of the socialist Montagnard party and would come third (5%) behind General Cavaignac (20%) and the winner Louis Napoléon Bonaparte (74%). Bastiat would have a chance to reply directly to Ledru-Rollin in April 1849 with his third expanded version of his essay when he too was campaigning for re-election as representative of his home district of Les Landes. [34]

Endnotes to the Introduction to the JDD version (29-34)

[29] See, “Bastiat’s Rhetoric of Liberty: Satire and the ‘Sting of Ridicule’,” in the Introduction to CW3, pp. lviii-lxiv.

[30] See Le Droit au travail à l’Assemblée Nationale. (Full ref) See also Faucher, “Droit au travail” in Coquelin, Dictionnaire de l’économie politique, vol. 1. pp. 605–19.

[31] Le Droit au travail à l’ Assemblée Nationale, pp. 373–74.

[32] See “Constitution de 1848. Assemblée nationale constituante (4 novembre 1848)” Online elsewhere.

[33] See Online elsewhere.

[34] Bastiat was elected to the Legislative Assembly in the election of 13 May 1849 to represent the département of Les Landes. He received 25,726 votes out of 49,762.

JDD version in French

L'État

[1-c5]

Je voudrais qu’on fondât un prix, non de cinq cents francs, mais d’un million, avec couronnes, croix et rubans, en faveur de celui qui donnerait une bonne, simple et intelligible définition de ce mot l'ETAT.

Quel immense service ne rendrait-il pas à la société!

L’ETAT! Qu'est-ce? où est-il? que fait-il ? que devrait-il faire?

Tout ce que nous en savons, c'est que c'est un personnage mystérieux, et assurément le plus sollicité, le plus tourmenté, le plus affairé le plus conseillé, le plus accusé, le plus invoqué et le plus provoqué qu'il y ait au monde.

Car Monsieur, je n'ai pas l'honneur de vous connaître mais je gage dix contre un que depuis [2-c1] six mois vous faites des utopies, et si vous en faites, je gage dix contre un que vous chargez l'ETAT de les réaliser.

Et vous, Madame, je suis sûr que vous désirez du fond du coeur guérir tous les maux de la triste humanité, et que vous n'y seriez nullement embarrassée, si l’ETAT voulait seulement s'y prêter.

Mais, hélas! le malheureux, comme Figaro, ne sait ni qui entendre, ni de quel côté se tourner. Les cent mille bouches de la presse et de la tribune lui crient à la fois:

Organisez le travail et les travailleurs.

Extirpez l'égotisme.

Réprimez l'insolence et la tyrannie du capital.

Faites des expériences sur le fumier et sur les oeufs.

Fondez des fermes-modèles.

Fondez des ateliers harmoniques.

Colonisez l'Algérie.

Allaitez les enfans.

Instruisez la jeunesse.

Secourez la vieillesse.

Envoyez dans les campagnes les habitans des villes.

Pondérez les profits de toutes les industries.

Prêtez de l'argent, et sans intérêt, à ceux qui en désirent.

Affranchissez l'Italie, la Pologne et la Hongrie.

Elevez et perfectionnez le cheval de selle.

Encouragez l'art, formez-nous des musiciens et des danseuses.

Prohibez le commerce et créez une marine marchande.

Découvrez la vérité et jetez dans nos têtes un grain de raison. L'Etat a pour mission d'éclairer, de développer, d'agrandir, de fortifier, de spiritualiser et de sanctifier l'âme des peuples.

Eh! Messieurs, un peu de patience, répond l'ETAT d'un air piteux.

Uno a la volta, per carità!

J'essaierai de vous satisfaire, mais pour cela il me faut quelques ressources. J'ai préparé des projets concernant cinq ou six impôts tout nouveaux et les plus bénins du monde. Vous verrez quel plaisir on a à les payer.

Mais alors un grand cri s'élève. Haro! haro! le beau mérite de faire quelque chose avec des ressources! Il ne vaudrait pas la peine de s'appeler l'État. Loin de nous frapper de nouvelles taxes, nous vous sommons de retirer les anciennes. Supprimez:

L'impôt du sel,

L'impôt des boissons,

L'impôt des lettres,

L'octroi, les patentes, les prestations.

Au milieu de ce tumulte, et après que le pays a changé deux ou trois fois son Etat pour n'avoir pas satisfait à toutes ces demandes, j'ai voulu faire observer qu'elles étaient contradictoires. De quoi me suis-je avisé, bon Dieu! ne pouvais-je garder pour moi cette malencontreuse remarque ? Me voilà discrédité à tout jamais, et il est maintenant reçu que je suis un homme sans coeur et sans entrailles, un philosophe sec, un individualiste, et, pour tout dire en un mot, un économiste de l'école anglaise ou américaine.

Oh pardonnez-moi, écrivains sublimes, que rien n'arrête, pas même les contradictions. J'ai tort, sans doute, et je me rétracie de grand coeur. Je ne demande pas mieux, soyez-en sûrs, que vous ayez vraiment découvert, en dehors de nous, un être bienfaisant et inépuisable, s'appelant l'ETAT, qui ait du pain pour toutes les bouches, du travail pour tous les bras, des capitaux pour toutes les entreprises, du crédit pour tous les projets, de l'huile pour toutes les plaies, du baume pour toutes les souffrances, des conseils pour toutes les perplexités, des solutions pour tous les doutes, des vérités pour toutes les intelligences, des distractions pour tous les ennuis, du lait pour l'enfance et du vin pour la vieillesse, qui pourvoie à tous; nos besoins, prévienne tous nos désirs, satisfasse toutes nos curiosités, redresse toutes nos erreurs, répare toutes nos fautes, et nous dispense tous désormais de prévoyance, de prudence, de jugement, de sagacité, d'expérience, d'ordre, d'économie, de tempérance et d'activité.

Eh! pourquoi ne le désirerais-je pas? Dieu me pardonne, plus j'y réfléchis, plus je trouve que la chose est commode et il me tarde d'avoir moi aussi, à ma portée, cette source intarissable de richesses et de lumières ce médecin universel, ce trésor sans fonds, ce conseiller infaillible que vous nommez I'ETAT.

Aussi je demande qu'on me le montre, qu'on me lé définisse, et c'est pourquoi je propose la fondation d'un prix pour le premier qui découvrira ce phénix. Car enfin, on m'accordera bien que cette découverte précieuse n'a pas encore été faite puisque, jusqu'ici, tout ce qui se présente sous le [2-c2]nom d'ETAT, le peuple le renverse aussitôt, précisément parce qu'il ne remplit pas aux conditions le quelque peu contradictoires du programme.

Faut-il le dire? je crains que nous ne soyons, à cet égard, dupes d'une des plus bizarres illusions qui se soient jamais emparées de l'esprit humain.

La plupart, la presque totalité des choses qui peuvent nous procurer une satisfaction, ou nous délivrer d'une souffrance, doivent être achetées par un effort, une peine. Or à toutes les époques, on a pu remarquer chez les hommes un triste penchant à séparer en deux ce lot complexe de la vie, gardant pour eux la satisfaction et rejetant la peine sur autrui. Ce fut l'objet de l'Esclavage; c'est encore l'objet de la Spoliation, quelque forme qu'elle prenne, abus monstrueux, mais conséquens, on ne peut le nier, avec le but qui leur a donné naissance.

L'Esclavage a disparu, grâce au ciel, et la Spoliation directe et naïve n'est pas facile. Une seule chose est restée, ce malheureux penchant primitif à faire deux parts des conditions de la vie. Il ne s'agissait plus que de trouver le bouc émissaire (scapegoat) sur qui en rejeter la portion fatigante et onéreuse. L'ETAT s'est présenté fort à propos.

Donc, en attendant une autre définition, voici la mienne : L'Etat, c'est la grande fiction à travers laquelle tout le monde s'efforce de vivre aux dépens de tout le monde.

Car, aujourd'hui comme autrefois, chacun un peu plus, un peu moins voudrait bien vivre du travail d'autrui. Ce sentiment, on n'ose l'afficher, on se le dissimule à soi-même; et alors que fait-on ? On imagine un intermédiaire, et chaque classe tour à tour vient dire à l'Etat : « Vous qui pouvez prendre légalement, honnêtement, prenez au public et nous partagerons. » L'Etat n'a que trop de pente à suivre ce diabolique conseil. C'est ainsi qu'il multiplie le nombre de ses agens, élargit le cercle de ses attributions et finit par acquérir des proportions écrasantes. Quand donc le public s'avisera-t-il enfin de comparer ce qu'on lui prend avec ce qu'on lui rend? Quand reconnaîtra-t-il que le pillage réciproque n'en est pas moins onéreux, parce qu'il s'exécute avec ordre par un intermédiaire dispendieux?

Remontons à la source de cette illusion.

Nous sommes trente-cinq millions d'individualités, et de même qu'on nomme blancheur cette qualité commune à tous les objets blancs, nous désignons la réunion de tous les Français par ces appellations collectives France, République, Etat.

Ensuite, nous nous plaisons à supposer dans celle abstraction de l'intelligence, de la prévoyance, des richesses, une volonté, une vie propre et distincte de la vie individuelle. C'est cette abstraction que nous voulons follement substituer à l'Esclavage antique. C'est sur elle que nous rejetons la peine, la fatigue, le fardeau et la responsabilité des existences réelles et comme s'il y avait une France en dehors des Français, une cité en dehors des citoyens, nous donnons au monde cet étrange spectacle de citoyens attendant tout de la cité, de réalités vivantes attendant tout d'une vaine abstraction.

Cette chimère apparaît au début mème de notre Constitution.

Voici les premières paroles du préambule :

« La France s'est constituée en République pour appeler tous les citoyens à un degré toujours plus élevé de moralité, de lumières et de bien-être. »

Ainsi les citoyens qui sont les réalités en qui réside le principe de vie et d'intelligence d'où jaillissent la moralité, les lumières et le bien-être les attendent de qui? De la France, qui est l'abstraction. Pour montrer l'inanité de la proposition, il suffit de la retourner. Certes, il eût été tout aussi exact de dire : « Les citoyens se sont constitués en République pour appeler la France à un degré toujours plus élevé, etc. »

Les Américains se faisaient une autre idée des relations des citoyens et de l'Etat, quand ils placèrent en tête de leur Constitution ces simples paroles:

« Nous, le peuple des Etats-Unis, pour former une union plus parfaite, établir la justice, assurer la tranquillité intérieure, pourvoir à la défense commune, accroître le bien-être général et assurer les bienfaits de la liberté à nous-mêmes et à notre postérité, décrétons, etc. »

Il ne s'agit pas ici, comme on pourrait le croire, d'une subtilité métaphysique. Je prétends que cette personnification de l'Etat a été dans le passé et sera dans l'avenir une source féconde de calamités et de révolutions.

Voilà donc le public d'un côté, l'Etat de l'autre, considérés comme deux êtres distincts; celui-ci chargé d'épandre sur celui-là le torrent des félicités humaines. Que doit-il arriver?

Au fait, l'Etat ne peut conférer aucun avantage [2-c3] particulier à une des individualités qui composent le public sans infliger un dommage supérieur à la communauté tout entière.

Il se trouve donc placé, sous les noms de pouvoir, gouvernement, ministère, dans un cercle vicieux manifeste.

S'il refuse le bien direct qu'on attend de lui, il est accusé d'impuissance, de mauvais vouloir, d'impéritie. S'il essaie de le réaliser, il est réduit à frapper le peuple de taxes redoublées, et attire sur lui la désaffection générale.

Ainsi, dans le public, deux espérances dans le gouvernement, deux promesses : Beaucoup de bienfaits, et peu d'impôts; espérances et promesses qui, étant contradictoires, ne se réalisent jamais.

N'est-ce pas là la cause de toutes nos révolutions? Car entre l'Etat qui, prodigue les promesses impossibles, et le public qui a conçu des espérances irréalisables, viennent s'interposer deux classes d'hommes : les ambitieux et les utopistes. Leur rôle est tout tracé par la situation. Il suffit à ces courtisans de popularité de crier aux oreilles du peuple : « Le pouvoir te trompe si nous étions à sa place, nous te comblerions de bienfaits et t'affranchirions de taxes. »

Et le peuple croit, et le peuple espère, et le peuple fait une révolution.

Ses amis ne sont pas plutôt aux affaires, qu'ils sont sommés de s'exécuter. « Donnez-moi donc du travail, du pain, des secours, du crédit, de l'instruction, des colonies, dit le peuple, et cependant, selon vos promesses, délivrez-moi des serres du fisc. »

L'Etat nouveau n'est pas moins embarrassé que l'Etat ancien, car, en fait d'impossible, on peut bien promettre, mais non tenir. Il cherche à gagner du temps, il lui en faut pour mûrir ses vastes projets. D'abord il fait quelques timides essais d'un côté, il étend quelque peu l'instruction primaire; de l'autre, il modifie quelque peu l'impôt des boissons (1830). Mais la contradiction se dresse toujours devant lui : s'il veut être philanthrope, il est forcé de rester fiscal, et s'il renonce à la fiscalité, il faut qu'il renonce aussi à la philanthropie. De ces deux anciennes promesses, il y en a toujours une qui échoue nécessairement. Alors il prend bravement son parti, il réunit des forces pour se maintenir; il déclare qu'on ne peut administrer qu'à la condition d'être impopulaire, et que l'expérience l'a rendu gouvernemental.

Et c'est là que d'autres courtisans de popularité l'attendent. Ils exploitent la même illusion, passent par la même voie, obtiennent le même succès, et vont bientôt s'engloutir dans le même gouffre.

C'est ainsi que nous sommes arrivés en Février. A cette époque, l'illusion qui fait le sujet de cet article avait pénétré plus avant que jamais dans les idées du peuple, avec les doctrines socialistes. Plus que jamais, il s'attendait à ce que l'Etat, sous la forme républicaine, ouvrirait toute grande la source des bienfaits et fermerait celle de l'impôt.

« On m'a souvent trompé, disait le peuple, mais je veillerai moi-même à ce qu'on ne me trompe pas encore une fois. »

Que pouvait faire le gouvernement provisoire ? Hélas! ce qu'on fait toujours en pareille conjoncture promettre et gagner du temps. Il n'y manqua pas, et pour donner à ses promesses plus de-solennité il les fixa dans des décrets. « Augmentation de bien-être, diminution de travail, secours, crédits, instruction gratuite, colonies agricoles, défrichemens et en même temps réduction sur la taxe du sel, des boissons, des lettres, de la viande, tout te sera accordé, vienne l'Assemblée Nationale. »

L'Assemblée Nationale est venue, et comme on ne peut réaliser deux contradictions, sa tâche, sa triste tâche s'est bornée à retirer, le plus doucement possible, l'un après l'autre, tous les décrets du gouvernement provisoire.

Cependant, pour ne pas rendre la déception trop cruelle, il a bien fallu transiger quelque peu. Certains engagemens ont été maintenus, d'autres ont reçu un tout petit commencement d'exécution. Aussi l'administration actuelle s'efforce-t-elle d'imaginer de nouvelles taxes.

Maintenant je me transporte par la pensée à quelques mois dans l'avenir, et je me demande, la tristesse dans l'âme, ce qu'il adviendra quand des agens de nouvelle création iront dans nos campagnes prélever les nouveaux impôts sur les successions, sur les revenus, sur les profits de l'exploitation agricole. Que le ciel démente mes presentimens, mais je vois encore là un rôle à jouer pour les courtisans de popularité.

Il faut donc que le peuple de France apprenne cette grande leçon : Personnifier l'Etat, et attendre de lui qu'il prodigue les bienfaits en réduisant les taxes, c'est une véritable puérilité, mais une puérilité d'où sont sorties et d'où peuvent sortir encore bien des tempêtes. Le gouffre des révolutions ne [2-c4] se refermera pas tant que nous ne prendrons pas l'Etat pour ce qu'il est, la force commune instituée, non pour être entre les citoyens un instrument d'oppression réciproque, mais au contraire pour faire régner entre eux la justice et la sécurité.

FRÉDÉRIC BASTIAT.

JDD version in English

The State

[1-c5]

I wish that a prize would be established—not of five hundred francs, but of a million, adorned with crowns, crosses, and ribbons—for whomever can provide a good, simple, and intelligible definition of this word: THE STATE.

What an immense service such a person would render to society!

THE STATE! What is it? Where is it? What does it do? What should it do?

All we know is that it is a mysterious person—undoubtedly the most solicited, the most tormented, the busiest, the most advised, the most accused, the most invoked, and the most provoked being in the world.

For, sir, though I do not have the honor of knowing you, I would wager ten to one that for the past [2-c1] six months you have been devising utopias. And if you have, I would wager ten to one that you are relying on THE STATE to realize them.

And you, madam, I am certain that you deeply wish to cure all the ills of suffering humanity, and that you would have no trouble doing so—if only THE STATE would lend itself to the task.

But alas! Like Figaro, the poor creature does not know to whom to listen, nor which direction to turn. The hundred thousand mouths of the press and the tribune cry out to it all at once:

Organize labor and workers.

Eradicate selfishness.

Repress the insolence and tyranny of capital.

Conduct experiments on manure and eggs.

Establish model farms.

Create harmonious workshops.

Colonize Algeria.

Nurse infants.

Educate the youth.

Assist the elderly.

Send city dwellers to the countryside.

Regulate the profits of all industries.

Lend money—without interest—to all who desire it.

Liberate Italy, Poland, and Hungary.

Breed and improve saddle horses.

Encourage the arts, train musicians and dancers.

Prohibit commerce and create a merchant navy.

Discover the truth and instill a grain of reason into our minds. The State’s mission is to enlighten, develop, expand, strengthen, spiritualize, and sanctify the soul of the people.

"Ah! Gentlemen, a little patience," replies THE STATE with a pitiful air.

"Uno a la volta, per carità!"

"I will try to satisfy you, but for that, I need resources. I have prepared proposals for five or six entirely new taxes, the mildest in the world. You will see what a pleasure it is to pay them."

But then a great outcry arises: Haro! Haro! What merit is there in doing something with resources? It wouldn’t even be worth calling oneself the State! Far from imposing new taxes on us, we demand that you repeal the old ones. Abolish:

The salt tax,

The beverage tax,

The postage tax,

The city tolls, licenses, and labor dues.

Amid this tumult, and after the country has changed its State two or three times for failing to satisfy all these demands, I dared to point out that they were contradictory. What was I thinking, good heavens! Could I not have kept this unfortunate observation to myself? Now I am forever discredited, and it is widely accepted that I am a heartless man, devoid of compassion—a cold philosopher, an individualist, and, to sum it up in a single word, an economist of the English or American school.

Oh, forgive me, sublime writers, who are hindered by nothing—not even contradictions! I am surely in the wrong, and I retract my words wholeheartedly. Rest assured, I would love nothing more than to believe that you have truly discovered, apart from us, a benevolent and inexhaustible being called THE STATE—one that has bread for every mouth, work for every hand, capital for every enterprise, credit for every project, oil for every wound, balm for every suffering, advice for every perplexity, solutions for every doubt, truths for every mind, distractions for every boredom, milk for childhood, and wine for old age—one that provides for all our needs, anticipates all our desires, satisfies all our curiosities, corrects all our errors, repairs all our faults, and relieves us henceforth of all foresight, prudence, judgment, wisdom, experience, order, economy, temperance, and activity.

And why would I not wish for this? God forgive me, but the more I think about it, the more I find it convenient! I, too, am eager to have at my disposal this inexhaustible source of wealth and wisdom—this universal healer, this bottomless treasury, this infallible counselor that you call THE STATE.

Thus, I demand that it be shown to me, that it be defined for me, and that is why I propose establishing a prize for the first person who discovers this phoenix. For in the end, one must admit that this precious discovery has yet to be made—since, until now, every entity that presents itself under the [2-c2] name STATE is overthrown by the people as soon as it fails to fulfill the somewhat contradictory conditions of its mandate.

Should I say it? I fear that, in this regard, we have fallen victim to one of the strangest illusions that has ever possessed the human mind.

Most, if not nearly all, of the things that can bring us satisfaction or relieve our suffering must be obtained through effort and hardship. Throughout all ages, men have shown a lamentable tendency to divide this dual condition of life, keeping satisfaction for themselves and shifting the burden onto others. This was the origin of slavery; it remains the basis of plunder—in whatever form it takes—monstrous abuses, yet undeniably consistent with the selfish aim that gave rise to them.

Slavery has disappeared, thank heaven, and outright, primitive plunder is no longer easy. Only one thing remains: the primal tendency to divide the burdens of life in two. All that was left was to find a scapegoat onto which the burdensome and costly portion could be shifted. THE STATE presented itself most opportunely.

Thus, while awaiting another definition, here is mine: The State is the great fiction through which everyone endeavors to live at the expense of everyone else.

For, today as in the past, each person—more or less—wishes to live off the labor of others. This sentiment is not openly displayed; one even hides it from oneself. And so, what is done? An intermediary is imagined, and each class, in turn, comes to the State and says: "You, who can lawfully and honestly take from the public, take—and we shall share it." The State is only too inclined to follow this devilish advice. Thus, it multiplies the number of its agents, broadens the scope of its functions, and eventually grows to overwhelming proportions. When will the public finally think to compare what is taken from it with what is given back? When will it realize that reciprocal plunder is no less burdensome simply because it is carried out in an orderly fashion through an expensive intermediary?

Let us trace this illusion back to its source.

We are thirty-five million individuals, and just as we call whiteness the common quality of all white objects, we designate the sum of all French people with collective terms such as France, Republic, State.

Then, we indulge in the notion that this abstraction possesses intelligence, foresight, wealth, a will, a life of its own, distinct from individual life. It is this abstraction that we foolishly wish to substitute for ancient slavery. It is upon it that we seek to cast the burden, toil, hardship, and responsibility of real existence. And as if there were a France apart from the French, or a society apart from its citizens, we present to the world this strange spectacle: citizens expecting everything from the city—living realities waiting for sustenance from a mere abstraction.

This illusion appears at the very beginning of our Constitution.

Here are the first words of the preamble:

"France has constituted itself as a Republic to call all citizens to an ever higher degree of morality, enlightenment, and well-being."