AKIRA KUROSAWA, RASHOMON (1950) 1HR 27 (LD)

Note: This film guide is part of a collection of film guides on history, politics, and war.

THE DIRECTOR: AKIRA KUROSAWA (1910 - )

One of the greatest and certainly the best known (in the West) Japanese filmmakers. Born 1910 in Tokyo. Studied at Doshusha School of Western Painting. His popularity in the West can be attributed to the way he is able to combine traditional Japanese and Western elements (due to his study of Western painting, literature and political philosophy) in his filmmaking. His early films were made under the militaristic dictatorship which controlled Japan during WW2. The degree to which such films as The Men who tread on the Tiger's Tail (1945) or Judo Saga (1943) were propaganda for the military regime or examples of stylistic experimentation is debated. Before he enjoyed creative freedom in his filmmaking AK had to endure the controls and censorship of the post-war American occupation. Films like No Regrets for Our Youth (1946) might be regarded as just another form of political propaganda (this time pro-democracy). Yet themes which were to recurr in his later work appeared at this time as well as his distinctive style which incorporated elements of the silent cinema, Soviet cinema and the Golden Age of Hollywood filmmaking.

One critic has argued that:

Above all, Kurosawa is a modern filmmaker, portraying the ethical and metaphysical dilemmas characteristic of postwar culture, the world of the atomic bomb, which has rendered certainty and dogma absurd. The consistency at the heart of Kurosawa's work is his exploration of the concept of heroism. Whether portraying the world of the wandering swordsman, the intrepid policeman or the civil servant, Kurosawa focuses on men faced with ethical and moral choices. The choice of action suggests that Kurosawa's heroes share the same dilemma as Camus's existential protagonists, but for Kurosawa the choice is to act morally, to work for the betterment of one's fellow humans. Perhaps because Kurosawa experienced the twin devastations of the great Kanto earthquake of 1923 and WWII, his cinema focuses on times of chaos. From the destruction of the glorious Heian court society that surrounds the world of RASHOMON (1950), to the neverending destruction of the civil war era of the 16th century that gives THE SEVEN SAMURAI (1954) its dramatic impetus, to the savaged Tokyo in the wake of US bombing raids in DRUNKEN ANGEL (1948), to the ravages of the modern bureaucratic mind-set that pervade IKIRU (1952) and THE BAD SLEEP WELL (1960), Kurosawa's characters are situated in periods of metaphysical eruption, threatened equally by moral destruction and physical annihilation in a world in which God is dead and nothing is certain. But it is his hero who, living in a world of moral chaos, in a vacuum of ethical and behavorial standards, nevertheless chooses to act for the public good. (Cinemania95).

AK is appreciated in the West also for his adaptations of Western literary classics, especially Shakespeare whose work seems well suited to being relocated with minimal distortion to medieval Japan: Throne of Blood (1957) (from Macbeth) and Ran (1985) (from King Lear, about a warlord who hands over his estates to his sons and triggers a power struggle). He is also willing to adapt Western popular culture, like the Western, as in The Seven Samurai (which in turn was remade by Sturges as a 'real" Western as The Magnificnet Seven (1960), thus completing the circle). In his more recent films AK has dealt with the issue of the destruction of nature in Akira Kurosawa's Dreams (1990) and the memories of the atomic bombing of Kagasaki through the eyes of an old woman who survived it in Rhapsody in August (1991).

Other films of note: Kagemusha (1980) about a 16thC thief who is spared execution if he agrees to act as a dead warlord's double in order to prevent a power struggle (Image from film of charging horsemen (272K)); The Hidden Fortress (1958) an adventure comedy which was the inspiration for George Lucas' Star Wars; Yojimbo (1961) (film poster 179K) and Sanjuro (1962) tongue-in-cheek Samurai "Westerns" in which a Samurai for hire plays off two warring factions who vie for control of a town (inspiration for the spaghetti western A Fist Full of Dollars which started Clint Eastwood's career in westerns.)

LITERARY SOURCE

2 short stories which were the inspiration for Kurosawa's film:

- Ryunosuke Akutagawa, Rashomon and Other Stories, trans. Takashi Kojima (New York: Liveright, 1952). "In a Grove," pp. 19-33; "Rashomon" pp. 34-44.

THE FILM

Images

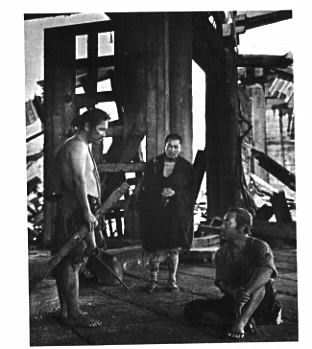

- See below: Participants and witnesses seeking shelter at the crumbling Rashomon Gate recount their very different recollections of the incident at the grove (Still from "Rashomon" (153K))

- Illustration from Akutagawa's short story "In a Grove" (43K) - the woman brandishing a short sword

- Illustration from Akutagawa's short story "Rashomon" (94K) - the discharged servant confronting an old woman looting the dead at the gate

|

| Participants and witnesses seeking shelter at the crumbling Rashomon Gate recount their very different recollections of the incident at the grove (Still from "Rashomon") |

Meaning of the Title

The editor of the above collection of short stories by Akutagawa observes in a note that:

The "Rashomon" was the largest gate in Kyoto, the ancient capital of Japan. It was 106 feet wide and 26 feet deep, and was topped with a ridge-pole; its stone wall rose 75 feet high. This gate was constructed in 789 when the then capital of Japan was transferred to Kyoto. Witht the decline of West Kyoto, the gate fell into bad repair, cracking and crumbling in many places, and became a hide-out for thieves and robbers and a place for abandoning unclaimed corpses. (p. 34)

Cast

- Tajomaru the bandit - Toshiro Mifune

- The Woman, Masago - Machiko Kyo

- The Man, samurai Kanazawa no Takehiko - Masayuki Mori

- Firewood Dealer - Takashi Shimura

- the Buddhist priest - Minoru Chiaki

- The Commoner - Kichijuro Ueda

- The Medium - Fumiko Homma

In a forest grove of cedars and bamboo a woman is raped and a man killed; some time later the bandit Tojamaru is caught riding the dead man's horse. Evidence is heard from the woodcutter who discovered the body; the monk who met the samurai and the woman on the road in the forest; the policeman who captured the bandit on the dead samurai's horse; the bandit who relates his own story of the events; the raped woman; and the dead man himself (via the Medium). After the court inquiry is over, 2 of the court witnesses seek shelter from the rain under the crumbling Rashomon Gate in Kyoto. To pass the time they relate their stories to a third man, a commoner. It unfolds that 3 of the participants claimed to have killed the husband (the woman, the bandit and the samurai); each tells a very different account of what happened. Things are further confused when the woodcutter claims, in spite of evidence to the contrary, that "I don't tell lies" and yet then gives a second account which contradicts his first. The events at the Rashomon Gate are interrupted by the discovery of an abandoned baby which the woodcutter reluctantly adopts.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Joan Mellon, The Waves at Genji's Door: Japan Through its Cinema (New York: Pantheon Books, 1976).

Donald Richie, The Films of Akira Kurosawa (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1984 revised edition), pp. 70-80.

THINGS TO NOTE

- The nature of truth and falsehood and how difficult it is to distinguish between the two. Hark: "Multiple perspectives do not necessarily add up to truth."

- The reasons why 3 people could have such differing recollections of the same event; motives for telling the truth, telling a story, telling lies; how the desire for revenge, honour, notoriety, jealousy, hatred, contempt, fame as a noted swordsman, greed, shame, sexual gratification alters or influences memory; how a third party (the court or the commoner under the gate) can distinguish between truth and falsehood and mixtures of the two (stories, history, legal evidence, memory).

- The different types of evidence presented: eyewitness accounts, reporting what transpired at the court (reporting what others said and what he himself said); the evidence presented by the camera. Assessing the reliability of witnesses and their stories - "eyes are not reliable"; "people are ultimately mysterious"

- The contrast between the scenes in the forest, under the gate, and at the police court.

- The monk who sees the samurai and his wife on the road in the forest: "I cannot find the words..."