Herbert Spencer, The Principles of Sociology (1898)

Three volumes in One

|

|

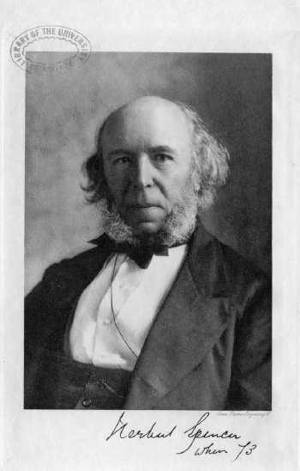

| Herbert Spencer (1820–1903) |

[Created: 31 Aug. 2022]

[Updated: May 1, 2023 ] |

The Guillaumin Collection

|

This title is part of “The Guillaumin Collection” within “The Digital Library of Liberty and Power”. It has been more richly coded and has some features which other titles in the library do not have, such as the original page numbers, formatting which makes it look as much like the original text as possible, and a citation tool which makes it possible for scholars to link to an individual paragraph which is of interest to them. These titles are also available in a variety of eBook formats for reading on portable devices. |

Source

, The Principles of Sociology, in Three Volumes (New York: D. Appleton and Company, 1898). Authorized third edition. http://davidmhart.com/liberty/davidmhart.com/liberty/EnglishClassicalLiberals/Spencer/1898-PrinciplesSociology/Spencer-Principles-3vols-in1.html

This title is also available in a facsimile PDF of the original and various eBook formats - HTML, PDF, and ePub.

The Principles of Sociology appeared in three volumes which were published between 1874 and 1896. The edition used here is the “authorized” 3rd edition of 1898.

- Volume I (1874–75; enlarged 1876, 1885) – pp. 3-773; Sections 1-342 [see the facs . PDF; and eBook formats - HTML, PDF, and ePub]

- Part I: Data of Sociology;

- Part II: Inductions of Sociology;

- Part III: Domestic Institutions -

- Volume II (1879-1885) – pp. 3-667; Sections 343-582 [see the facs . PDF; and eBook formats - HTML, PDF, and ePub]

- Part IV: Ceremonial Institutions (1879);

- Part V: Political Institutions (1882);

- Part VI Ecclesiastical Institutions (1885) -

- Volume III (1885-1896) – pp. 3-611; Sections 583-853 [see the facs . PDF; and eBook formats - HTML, PDF, and ePub]

- Part VI Ecclesiastical Institutions (1885);

- Part VII: Professional Institutions (1896);

- Part VIII: Industrial Institutions (1896)

This book is part of a collection of works by Herbert Spencer (1820–1903).

The Tables of Contents

[I-xi]

CONTENTS OF VOL I.

- Prefaces

- Preface to the Third Edition. p. v

- Preface to Vol. I. p. ix

- Part I.—THE DATA OF SOCIOLOGY.

- CHAP. I. SUPER ORGANIC EVOLUTION page 3

- II. THE FACTORS OF SOCIAL PHENOMENA p. 8

- III. ORIGINAL EXTERNAL FACTORS p. 16

- IV. ORIGINAL INTERNAL FACTORS p. 38

- V. THE PRIMITIVE MAN—PHYSICAL p. 41

- VI. THE PRIMITIVE MAN—EMOTIONAL p. 54

- VII. THE PRIMITIVE MAN—INTELLECTUAL p. 75

- VIII. PRIMITIVE IDEAS p. 94

- IX. THE IDEA OF THE ANIMATE AND INANIMATE p. 125

- X. THE IDEAS OF SLEEP AND DREAMS p. 134

- XI. THE IDEAS OF SWOON, APOPLEXY, CATALEPSY, ECSTASY, AND OTHER FORMS OF INSENSIBILITY p. 145

- XII. THE IDEAS OF DEATH AND RESURRECTION p. 153

- XIII. THE IDEAS OF SOULS, GHOSTS, SPIRITS, DEMONS, ETC. p. 171

- XIV. THE IDEAS OF ANOTHER LIFE p. 184

- XV. THE IDEAS OF ANOTHER WORLD p. 201

- XVI. THE IDEAS OF SUPERNATURAL AGENTS p. 218

- XVII. SUPERNATURAL AGENTS AS CAUSING EPILEPSY AND CONVULSIVE ACTIONS, DELIRIUM AND INSANITY, DISEASE AND DEATH p. 226

- XVIII. INSPIRATION, DIVINATION, EXORCISM, AND SORCERY p. 236

- XIX. SACRED PLACES, TEMPLES, AND ALTARS; SACRIFICE, FASTING, AND PROPITIATION; PRAISE, PRAYER, ETC. p. 253

- XX. ANCESTOR-WORSHIP IN GENERAL p. 285

- XXI. IDOL-WORSHIP AND FETICH-WORSHIP p. 306

- XXII. ANIMAL-WORSHIP p. 329

- XXIII. PLANT-WORSHIP p. 355

- XXIV. NATURE-WORSHIP p. 369

- XXV. DEITIES p. 395

- XXVI. THE PRIMITIVE THEORY OF THINGS p. 423

- XXVII. THE SCOPE OF SOCIOLOGY p. 435

- Part II.—THE INDUCTIONS OF SOCIOLOGY.

- I. WHAT IS A SOCIETY? p. 447

- II. A SOCIETY IS AN ORGANISM p. 449

- III. SOCIAL GROWTH p. 463

- IV. SOCIAL STRUCTURES p. 471

- V. SOCIAL FUNCTIONS p. 485

- VI. SYSTEMS OF ORGANS p. 491

- VII. THE SUSTAINING SYSTEM p. 498

- VIII. THE DISTRIBUTING SYSTEM p. 505

- IX. THE REGULATING SYSTEM p. 519

- X. SOCIAL TYPES AND CONSTITUTIONS p. 549

- XI. SOCIAL METAMORPHOSES p. 576

- XII. QUALIFICATIONS AND SUMMARY p. 588

- Part III.—DOMESTIC INSTITUTIONS.

- I. THE MAINTENANCE OF SPECIES p. 603

- II. THE DIVERSE INTERESTS OF THE SPECIES, OF THE PARENTS, AND OF THE OFFSPRING p. 606

- III. PRIMITIVE RELATIONS OF THE SEXES p. 613

- IV. EXOGAMY AND ENDOGAMY p. 623

- V. PROMISCUITY p. 643

- VI. POLYANDRY p. 654

- VII. POLYGYNY p. 664

- VIII. MONOGAMY p. 679

- IX. THE FAMILY p. 686

- X. THE STATUS OF WOMEN p. 725

- XI. THE STATUS OF CHILDREN p. 745

- XII. DOMESTIC RETROSPECT AND PROSPECT p. 757

- Appendices

- Endnotes

- References p. 851

- Titles of Works Referred to. p. 865

- Subject Index. p. 881

[II-ix]

CONTENTS OF VOL. II.

- Prefaces

- Preface to Part IV. p. v

- Preface to Part V. p. vii

- Preface to Part VI. p. ix

- Preface to the Second Edition. p. ix

- Part IV.—CEREMONIAL INSTITUTIONS

- chap. I.—CEREMONY IN GENERAL pages 3

- II.—TROPHIES p. 36

- III.—MUTILATIONS p. 52

- IV.—PRESENTS p. 83

- V.—VISITS p. 108

- VI.—OBEISANCES p. 116

- VII.—FORMS OF ADDRESS p. 144

- VIII.—TITLES p. 159

- IX.—BADGES AND COSTUMES p. 179

- X.—FURTHER CLASS-DISTINCTIONS p. 198

- XI.—FASHION p. 210

- XII.—CEREMONIAL RETROSPECT AND PROSPECT p. 216

- Part V.—POLITICAL INSTITUTIONS.

- I.—PRELIMINARY p. 229

- II.—POLITICAL ORGANIZATION IN GENERAL p. 244

- III.—POLITICAL INTEGRATION p. 265

- IV.—POLITICAL DIFFERENTIATION p. 288

- V.—POLITICAL FORMS AND FORCES p. 311

- VI.—POLITICAL HEADS—CHIEFS, KINGS, ETC. p. 331

- VII.—COMPOUND POLITICAL HEADS p. 366

- VIII.—CONSULTATIVE BODIES p. 397

- IX.—REPRESENTATIVE BODIES p. 415

- X.—MINISTRIES p. 442

- XI.—LOCAL GOVERNING AGENCIES p. 451

- XII.—MILITARY SYSTEMS p. 473

- XIII.—JUDICIAL AND EXECUTIVE SYSTEMS p. 492

- XIV.—LAWS p. 513

- XV.—PROPERTY p. 538

- XVI.—REVENUE p. 557

- XVII.—THE MILITANT TYPE OF SOCIETY p. 568

- XVIII.—THE INDUSTRIAL TYPE OF SOCIETY p. 603

- XIX.—POLITICAL RETROSPECT AND PROSPECT p. 643

- Endnotes

- References

- Titles of Works Referred to

- References

- Titles of Works Referred to

[III-ix]

CONTENTS OF VOL. III.

- Prefaces

- Preface. p. v

- Preface to Part VI. p. vii

- Preface to the Second Edition. p. vii

- PART VI.— ECCLESIASTICAL INSTITUTIONS.

- chap. I.—THE RELIGIOUS IDEA ... page 3

- II.—MEDICINE-MEN AND PRIESTS p. 37

- III.—PRIESTLY DUTIES OF DESCENDANTS p. 44

- IV.—ELDEST MALE DESCENDANTS AS QUASI-PRIESTS p. 47

- V.—THE RULER AS PRIEST p. 54

- VI.—THE RISE OF A PRIESTHOOD p. 61

- VII.—POLYTHEISTIC AND MONOTHEISTIC PRIESTHOODS p. 69

- VIII.—ECCLESIASTICAL HIERARCHIES p. 81

- IX.—AN ECCLESIASTICAL SYSTEM AS A SOCIAL BOND p. 95

- X.—THE MILITARY FUNCTIONS OF PRIESTS p. 107

- XI.—THE CIVIL FUNCTIONS OF PRIESTS p. 118

- XII.—CHURCH AND STATE p. 125

- XIII.—NONCONFORMITY p. 134

- XIV.—THE MORAL INFLUENCES OF PRIESTHOODS p. 140

- XV.—ECCLESIASTICAL RETROSPECT AND PROSPECT p. 150

- XVI.—RELIGIOUS RETROSPECT AND PROSPECT p. 159

- PART VII.— PROFESSIONAL INSTITUTIONS.

- I.—PROFESSIONS IN GENERAL p. 179

- II.—PHYSICIAN AND SURGEON p. 185

- III.—DANCER AND MUSICIAN p. 201

- IV.—ORATOR AND POET, ACTOR AND DRAMATIST p. 217

- V.—BIOGRAPHER, HISTORIAN, AND MAN OF LETTERS p. 235

- VI.—MAN OF SCIENCE AND PHILOSOPHER p. 247

- VII.—JUDGE AND LAWYER p. 261

- VIII.—TEACHER p. 274

- IX.—ARCHITECT p. 281

- X.—SCULPTOR p. 294

- XI.—PAINTER p. 304

- XII.—EVOLUTION OF THE PROFESSIONS p. 315

- PART VIII.— INDUSTRIAL INSTITUTIONS.

- I.—INTRODUCTORY p. 327

- II.—SPECIALIZATION OF FUNCTIONS AND DIVISION OF LABOUR p. 340

- III.—ACQUISITION AND PRODUCTION p. 362

- IV.—AUXILIARY PRODUCTION p. 369

- V.—DISTRIBUTION p. 373

- VI.—AUXILIARY DISTRIBUTION p. 378

- VII.—EXCHANGE p. 387

- VIII.—AUXILIARY EXCHANGE p. 392

- IX.—INTER-DEPENDENCE AND INTEGRATION p. 404

- X.—THE REGULATION OF LABOUR p. 412

- XI.—PATERNAL REGULATION p. 422

- XII.—PATRIARCHAL REGULATION p. 431

- XIII.—COMMUNAL REGULATION p. 436

- XIV.—GILD REGULATION p. 448

- XV.—SLAVERY p. 464

- XVI.—SERFDOM p. 479

- XVII.—FREE LABOUR AND CONTRACT p. 493

- XVIII.—COMPOUND FREE LABOUR p. 513

- XIX.—COMPOUND CAPITAL p. 526

- XX.—TRADE-UNIONISM p. 535

- XXI.—COOPERATION p. 553

- XXII.—SOCIALISM p. 575

- XXIII.—THE NEAR FUTURE p. 590

- XXIV.—CONCLUSION p. 608

- Endnotes

- REFERENCES p. 612

- TITLES OF WORKS REFERRED TO p. 620

Volume I

[I-v]

PREFACE TO THE THIRD EDITION.↩

In this third edition of the Principles of Sociology, Vol. I, several improvements of importance have been made. The text has been revised; references to the works quoted and cited have been supplied; the appendices have been enlarged; and the work has now an index.

Each chapter has been carefully gone through for the purpose of removing defects of expression and with a view to condensation. By erasing superfluous words and phrases, I have reduced the text to the extent of forty pages, notwithstanding the incorporation here and there of a further illustration. This abridgment, however, has not diminished the bulk of the volume; since the additions above named occupy much more space than has been gained.

In the preface to the first edition, I explained how it happened that the reader was provided with no adequate means of verifying any of the multitudinous statements quoted; and with the explanation I joined the expression of a hope that I might eventually remove the defect. By great labour the defect has now been removed—almost though not absolutely. Some years ago I engaged a gentleman who had been with me as secretary, Mr. P. R. Smith, since deceased, to furnish references; and with the aid of the Descriptive Sociology where this availed, and where it did not by going to the works of the authors quoted, he succeeded in finding the great majority of the passages. Still, however, there remained numerous gaps. Two years since I arranged with a skilled bibliographer, Mr. Tedder, the librarian of the Athenæum Club, to go through afresh all [I-vi] the quotations, and to supply the missing references while checking the references Mr. Smith had given. By an unwearied labour which surprised me, Mr. Tedder discovered the greater part of the passages to which references had not been supplied. The number of those which continued undiscovered was reduced by a third search, aided by clues contained in the original MS., and by information I was able to give. There now remain less than 2 per cent. of unreferenced statements.

The supplying of references was not, however, the sole purpose to be achieved. Removal of inaccuracies was a further purpose. The Descriptive Sociology from which numerous quotations were made, had passed through stages each of which gave occasion for errors. In the extracts as copied by the compilers, mistakes, literal and verbal, were certain to be not uncommon. Proper names of persons, peoples, and places, not written with due care, were likely to be in many cases mis-spelled by the printers. Thus, believing that there were many defects which, though not diminishing the values of the extracts as pieces of evidence, rendered them inexact, I desired that while the references to them were furnished, comparisons of them with the originals should be made. This task has been executed by Mr. Tedder with scrupulous care; so that his corrections have extended even to additions and omissions of commas. Concerning the results of his examination, he has written me the following letter:—

July, 1885.

Dear Mr. Spencer,

In the second edition (1877) of the Principles of Sociology, Vol. I, placed in my hands, there were 2,192 references to the 379 works quoted. In the new edition there are about 2,500 references to 455 works. All of these references, with the exception of about 45, have been compared with the originals.

In the course of verification I have corrected numerous trifling errors. They were chiefly literal, and included [I-vii] paraphrases made by the compilers of the Descriptive Sociology which had been wrongly inserted within quotation marks. There was a small proportion of verbal errors, among which were instances of facts quoted with respect to particular tribes which the original authority had asserted generally of the whole cluster of tribes—facts, therefore, more widely true than you had alleged.

The only instances I can recall of changes affecting the value of the statements as evidence were (1) in a passage from the Iliad, originally taken from an inferior translation; (2) the deletion of the reference (on p. 298 of second edition) as to an avoidance by the Hindus of uttering the sacred name Om.

Among the 455 works quoted there are only six which are of questionable authority; but the citations from these are but few in number, and I see no reason to doubt the accuracy of the information for which they are specially responsible.

I am,

Faithfully yours,

Henry R. Tedder.

The statement above named as one withdrawn, was commented on by Prof. Max Müller in his Hibbert Lectures; in which he also alleged that I had erred in asserting that the Egyptians abstained from using the sacred name Osiris. This second alleged error I have dealt with in a note on page 274, where I think it is made manifest that Prof. Max Müller would have done well to examine the evidence more carefully before committing himself.

The mention of Prof. Max Müller reminds me of another matter concerning which a few words are called for. In an article on this volume in its first edition, published in the Pall Mall Gazette for February 21st, 1877, it was said that the doctrine propounded in Part I, in opposition to that of the comparative mythologists, “will shortly be taken up, as we understand, by persons specially competent in that department.” When there were at length, in 1878, announced Prof. Max Müller’s Lectures on the Origin and Growth of Religion, etc., etc., I concluded that my curiosity [I-viii] to see a reply would at last be gratified. But on turning over the published report of his lectures, I discovered no attempt to deal with the hypothesis that religion is evolved from the ghost-theory: the sole reference to it being, as Mr. Andrew Lang remarks, some thirteen lines describing “psycholatry” as exhibited in Africa. The work proved to be a superfluous polemic against the hypothesis that fetishism is the primitive form of religion—superfluous, I say, because this hypothesis had been, I think, effectually disposed of by me in the first edition of this volume. Why Prof. Max Müller should have expended so much labour in disproving a doctrine already disproved, is not clear. Still less clear is it why, having before him the volume, and adversely criticizing certain statements in it referred to above, he entirely ignored the chapter in which was already done that which his lectures proposed to do.

What was the indirect purpose of his lectures I do not understand. He could not himself have supposed that a refutation of the fetish-theory was a refutation of the theory now standing opposed to his own; though it is not improbable that many of his hearers and readers, supposed that it was.

Concerning the new matter, little needs to be said. To Appendix A, entitled “Further Illustrations of Primitive Thought,” the additions are such as practically to constitute it a second demonstration of the thesis demonstrated in Part I. To Appendix B, on “The Mythological Theory,” a section has been prefixed. And Appendix C, on “The Linguistic Method of the Mythologists,” is new.

Bayswater, July, 1885.

[I-ix]

PREFACE TO VOL. I.↩

For the Science of Society, the name “Sociology” was introduced by M. Comte. Partly because it was in possession of the field, and partly because no other name sufficiently comprehensive existed, I adopted it. Though repeatedly blamed by those who condemn the word as “a barbarism,” I do not regret having done so. To use, as some have suggested, the word “Politics,” too narrow in its meaning as well as misleading in its connotations, would be deliberately to create confusion for the sake of avoiding a defect of no practical moment. The heterogeneity of our speech is already so great that nearly every thought is expressed in words taken from two or three languages. Already, too, it has many words formed in irregular ways from heterogeneous roots. Seeing this, I accept without much reluctance another such word: believing that the convenience and suggestiveness of our symbols are of more importance than the legitimacy of their derivation.

Probably some surprise will be felt that, containing as this work does multitudinous quotations from numerous authors, there are no references at the bottoms of pages. Some words of explanation seem needful. If foot-notes are referred to, the thread of the argument is completely broken; and even if they are not referred to, attention is disturbed by the consciousness that they are there to be looked at. Hence a loss of effect and a loss of time. As I intended to use as data for the conclusions set forth in this work, the compiled and classified facts forming the Descriptive Sociology, it occurred to me that since the arrangement of those [I-x] facts is such that the author’s name and the race referred to being given, the extract may in each case be found, and with it the reference, it was needless to waste space and hinder thought with these distracting foot-notes. I therefore decided to omit them. In so far as evidence furnished by the uncivilized races is concerned (which forms the greater part of the evidence contained in this volume), there exists this means of verification in nearly all cases. I found, however, that many facts from other sources had to be sought out and incorporated; and not liking to change the system I had commenced with, I left them in an unverifiable state. I recognize the defect, and hope hereafter to remedy it. In succeeding volumes I propose to adopt a method of reference which will give the reader the opportunity of consulting the authorities cited, while his attention to them will not be solicited.

The instalments of which this volume consists were issued to the subscribers at the following dates:—No. 35 (pp. 1—80) in June, 1874; No. 36 (pp. 81—160) in November, 1874; No. 37 (pp. 161—240) in February, 1875; No. 38 (pp. 241—320) in May, 1875; No. 39 (pp. 321—400) in September, 1875; No. 40 (pp. 401—462, with Appendices A & B) in December, 1875; No. 41 (pp. 465—544) in April, 1876; No. 42 (pp. 545—624) in July, 1876; and No. 43 (pp. 625—704) in December, 1876; an extra No. (44) issued in June, 1877, completing the volume.

With this No. 44, the issue of the System of Synthetic Philosophy to subscribers, ceases: the intention being to publish the remainder of it in volumes only. The next volume will, I hope, be completed in 1880.

London, December, 1876.

The Principles of Sociology, Vol. I

PART I.

THE DATA OF SOCIOLOGY.

[I-3]

CHAPTER I.

SUPER-ORGANIC EVOLUTION.↩

§ 1. Of the three broadly-distinguished kinds of Evolution outlined in First Principles, we come now to the third. The first kind, Inorganic Evolution, which, had it been dealt with, would have occupied two volumes, one dealing with Astrogeny and the other with Geogeny, was passed over because it seemed undesirable to postpone the more important applications of the doctrine for the purpose of elaborating those less important applications which logically precede them. The four volumes succeeding First Principles, have dealt with Organic Evolution: two of them with those physical phenomena presented by living aggregates, vegetal and animal, of all classes; and the other two with those more special phenomena distinguished as psychical, which the most evolved organic aggregates display. We now enter on the remaining division—Super-organic Evolution.

Although this word is descriptive, and although in First Principles, § 111, I used it with an explanatory sentence, it will be well here to exhibit its meaning more fully.

§ 2. While we are occupied with the facts displayed by an individual organism during its growth, maturity, and decay, we are studying Organic Evolution. If we take into account, as we must, the actions and reactions going on between this organism and organisms of other kinds which [I-4] its life puts it in relations with, we still do not go beyond the limits of Organic Evolution. Nor need we consider that we exceed these limits on passing to the phenomena that accompany the rearing of offspring; though here, we see the germ of a new order of phenomena. While recognizing the fact that parental co-operation foreshadows processes of a class beyond the simply organic; and while recognizing the fact that some of the products of parental co-operation, such as nests, foreshadow products of the super-organic class; we may fitly regard Super-organic Evolution as commencing only when there arises something more than the combined efforts of parents. Of course no absolute separation exists. If there has been Evolution, that form of it here distinguished as super-organic must have come by insensible steps out of the organic. But we may conveniently mark it off as including all those processes and products which imply the co-ordinated actions of many individuals.

There are various groups of super-organic phenomena, of which certain minor ones may be briefly noticed here by way of illustration.

§ 3. Of such the most familiar, and in some respects the most instructive, are furnished by the social insects.

All know that bees and wasps form communities such that the units and the aggregates stand in very definite relations. Between the individual organization of the hive-bee and the organization of the hive as an orderly aggregate of individuals with a regularly-formed habitation, there exists a fixed connexion. Just as the germ of a wasp evolves into a complete individual; so does the adult queen-wasp, the germ of a wasp-society, evolve into a multitude of individuals with definitely-adjusted arrangements and activities. As evidence that Evolution of this order has here arisen after the same manner as the simpler orders of Evolution, it may be added that, among both bees and wasps, different genera exhibit it in different degrees. From kinds [I-5] that are solitary in their habits, we pass through kinds that are social in small degrees to kinds that are social in great degrees.

Among some species of ants, Super-organic Evolution is carried much further—some species, I say; for here, also, we find that unlike stages have been reached by unlike species. The most advanced show us division of labour carried so far that different classes of individuals are structurally adapted to different functions. White ants, or termites (which, however, belong to a different order of insects), have, in addition to males and females, soldiers and workers; and there are in some cases two kinds of males and females, winged and unwinged: making six unlike forms. Of Saüba ants are found, besides the two developed sexual forms, three forms sexually undeveloped—one class of indoor workers and two classes of out-door workers. And then by some species, a further division of labour is achieved by making slaves of other ants. There is also a tending of alien insects, sometimes for the sake of their secretions, and sometimes for unknown purposes; so that, as Sir John Lubbock points out, some ants keep more domestic animals than are kept by mankind. Moreover, among members of these communities, there is a system of signalling equivalent to a rude language, and there are elaborate processes of mining, road-making, and building. In Congo, Tuckey “found a complete banza [village] of ant-hills, placed with more regularity than the native banzas”; and Schweinfurth says a volume would be required to describe the magazines, chambers, passages, bridges, contained in a termites-mound.

But, as hinted above, though social insects exhibit a kind of evolution much higher than the merely organic—though the aggregates they form simulate social aggregates in sundry ways; yet they are not true social aggregates. For each of them is in reality a large family. It is not a union among like individuals independent of one another in parentage, [I-6] and approximately equal in the capacities; but it is a union among the offspring of one mother, carried on, in some cases for a single generation, and in some cases for more; and from this community of parentage arises the possibility of classes having unlike structures and consequent unlike functions. Instead of being allied to the specialization which arises in a society, properly so called, the specialization which arises in one of these large and complicated insect-families, is allied to that which arises between the sexes. Instead of two kinds of individuals descending from the same parents, there are several kinds of individuals descending from the same parents; and instead of a simple co-operation between two differentiated individuals in the rearing of offspring, there is an involved co-operation among sundry differentiated classes of individuals in the rearing of offspring.

§ 4. True rudimentary forms of Super-organic Evolution are displayed only by some of the higher vertebrata.

Certain birds form communities in which there is a small amount of co-ordination. Among rooks we see such integration as is implied by the keeping-together of the same families from generation to generation, and by the exclusion of strangers. There is some vague control, some recognition of proprietorship, some punishment of offenders, and occasionally expulsion of them. A slight specialization is shown in the stationing of sentinels while the flock feeds. And usually we see an orderly action of the whole community in respect of going and coming. There has been reached a co-operation comparable to that exhibited by those small assemblages of the lowest human beings, in which there exist no governments.

Gregarious mammals of most kinds display little more than the union of mere association. In the supremacy of the strongest male in the herd, we do, indeed, see a trace of governmental organization. Some co-operation is shown, [I-7] for offensive purposes, by animals that hunt in packs, and for defensive purposes by animals that are hunted; as, according to Ross, by the North American buffaloes, the bulls of which assemble to guard the cows during the calving-season against wolves and bears. Certain gregarious mammals, however, as the beavers, carry social co-operation to a considerable extent in building habitations. Finally, among sundry of the Primates, gregariousness is joined with some subordination, some combination, some display of the social sentiments. There is obedience to leaders; there is union of efforts; there are sentinels and signals; there is an idea of property; there is exchange of services; there is adoption of orphans; and the community makes efforts on behalf of endangered members.

§ 5. These classes of truths, which might be enlarged upon to much purpose, I have here indicated for several reasons. Partly, it seemed needful to show that above organic evolution there tends to arise in various directions a further evolution. Partly, my object has been to give a comprehensive idea of this Super-organic Evolution, as not of one kind but of various kinds, determined by the characters of the various species of organisms among which it shows itself. And partly, there has been the wish to suggest that Super-organic Evolution of the highest order, arises out of an order no higher than that variously displayed in the animal world at large.

Having observed this much, we may henceforth restrict ourselves to that form of Super-organic Evolution which so immensely transcends all others in extent, in complication, in importance, as to make them relatively insignificant. I refer to the form of it which human societies exhibit in their growths, structures, functions, products. To the phenomena comprised in these, and grouped under the general title of Sociology, we now pass.

[I-8]

CHAPTER II.

THE FACTORS OF SOCIAL PHENOMENA.↩

§ 6. The behaviour of a single inanimate object depends on the co-operation between its own forces and the forces to which it is exposed: instance a piece of metal, the molecules of which keep the solid state or assume the liquid state, according partly to their natures and partly to the heat-waves falling on them. Similarly with any group of inanimate objects. Be it a cart-load of bricks shot down, a barrowful of gravel turned over, or a boy’s bag of marbles emptied, the behaviour of the assembled masses—here standing in a heap with steep sides, here forming one with sides much less inclined, and here spreading out and rolling in all directions—is in each case determined partly by the properties of the individual members of the group, and partly by the forces of gravitation, impact, and friction, they are subjected to.

It is equally so when the discrete aggregate consists of organic bodies, such as the members of a species. For a species increases or decreases in numbers, widens or contracts its habitat, migrates or remains stationary, continues an old mode of life or falls into a new one, under the combined influences of its intrinsic nature and the environing actions, inorganic and organic.

It is thus, too, with aggregates of men. Be it rudimentary or be it advanced, every society displays phenomena that are ascribable to the characters of its units and to the [I-9] conditions under which they exist. Here, then, are the factors as primarily divided.

§ 7. These factors are re-divisible. Within each there are groups of factors that stand in marked contrasts.

Beginning with the extrinsic factors, we see that from the outset several kinds of them are variously operative. We have climate; hot, cold, or temperate, moist or dry, constant or variable. We have surface; much or little of which is available, and the available part of which is fertile in greater or less degree; and we have configuration of surface, as uniform or multiform. Next we have the vegetal productions; here abundant in quantities and kinds, and there deficient in one or both. And besides the Flora of the region we have its Fauna, which is influential in many ways; not only by the numbers of its species and individuals, but by the proportion between those that are useful and those that are injurious. On these sets of conditions, inorganic and organic, characterizing the environment, primarily depends the possibility of social evolution.

When we turn to the intrinsic factors we have to note first, that, considered as a social unit, the individual man has physical traits, such as degrees of strength, activity, endurance, which affect the growth and structure of the society. He is in every case distinguished by emotional traits which aid, or hinder, or modify, the activities of the society, and its developments. Always, too, his degree of intelligence and the tendencies of thought peculiar to him, become co-operating causes of social quiescence or social change.

Such being the original sets of factors, we have now to note the secondary or derived sets of factors, which social evolution itself brings into play.

§ 8. First may be set down the progressive modifications of the environment, inorganic and organic, which societies effect.

[I-10]

Among these are the alterations of climate caused by clearing and by drainage. Such alterations may be favourable to social growth, as where a rainy region is made less rainy by cutting down forests, or a swampy surface rendered more salubrious and fertile by carrying off water [*] ; or they may be unfavourable, as where, by destroying the forests, a region already dry is made arid: witness the seat of the old Semitic civilizations, and, in a less degree, Spain.

Next come the changes wrought in the kinds and quantities of plant-life over the surface occupied. These changes are three-fold. There is the increasing culture of plants conducive to social growth, replacing plants not conducive to it; there is the gradual production of better varieties of these useful plants, causing, in time, great divergences from their originals; and there is, eventually, the introduction of new useful plants.

Simultaneously go on the kindred changes which social progress works in the Fauna of the region. We have the diminution or destruction of some or many injurious species. We have the fostering of useful species, which has the double effect of increasing their numbers and making their qualities more advantageous to society. Further, we have the naturalization of desirable species brought from abroad.

It needs but to think of the immense contrast between a wolf-haunted forest or a boggy moor peopled with wild birds, and the fields covered with crops and flocks which [I-11] eventually occupy the same area, to be reminded that the environment, inorganic and organic, of a society, undergoes a continuous transformation during the progress of the society; and that this transformation becomes an all-important secondary factor in social evolution.

§ 9. Another secondary factor is the increasing size of the social aggregate, accompanied, generally, by increasing density.

Apart from social changes otherwise produced, there are social changes produced by simple growth. Mass is both a condition to, and a result of, organization. It is clear that heterogeneity of structure is made possible only by multiplicity of units. Division of labour cannot be carried far where there are but few to divide the labour among them. Complex co-operations, governmental and industrial, are impossible without a population large enough to supply many kinds and gradations of agents. And sundry developed forms of activity, both predatory and peaceful, are made practicable only by the power which large masses of men furnish.

Hence, then, a derivative factor which, like the rest, is at once a consequence and a cause of social progress, is social growth. Other factors co-operate to produce this; and this joins other factors in working further changes.

§ 10. Among derived factors we may next note the reciprocal influence of the society and its units—the influence of the whole on the parts, and of the parts on the whole.

As soon as a combination of men acquires permanence, there begin actions and reactions between the community and each member of it, such that either affects the other in nature. The control exercised by the aggregate over its units, tends ever to mould their activities and sentiments and ideas into congruity with social requirements; and these activities, sentiments, and ideas, in so far as they are [I-12] changed by changing circumstances, tend to re-mould the society into congruity with themselves.

In addition, therefore, to the original nature of the individuals and the original nature of the society they form, we have to take into account the induced natures of the two. Eventually, mutual modification becomes a potent cause of transformation in both.

§ 11. Yet a further derivative factor of extreme importance remains. I mean the influence of the super-organic environment—the action and reaction between a society and neighbouring societies.

While there exist only small, wandering, unorganized hordes, the conflicts of these with one another work no permanent changes of arrangement in them. But when there have arisen the definite chieftainships which frequent conflicts tend to initiate, and especially when the conflicts have ended in subjugations, there arise the rudiments of political organization; and, as at first, so afterwards, the wars of societies with one another have all-important effects in developing social structures, or rather, certain of them. For I may here, in passing, indicate the truth to be hereafter exhibited in full, that while the industrial organization of a society is mainly determined by its inorganic and organic environments, its governmental organization is mainly determined by its super-organic environment—by the actions of those adjacent societies with which it carries on the struggle for existence.

§ 12. There remains in the group of derived factors one more, the potency of which can scarcely be over-estimated. I mean that accumulation of super-organic products which we commonly distinguish as artificial, but which, philosophically considered, are no less natural than all other products of evolution. There are several orders of these.

First come the material appliances, which, beginning with roughly-chipped flints, end in the complex automatic [I-13] tools of an engine-factory driven by steam; which from boomerangs rise to eighty-ton guns; which from huts of branches and grass grow to cities with their palaces and cathedrals. Then we have language, able at first only to eke out gestures in communicating simple ideas, but eventually becoming capable of expressing involved conceptions with precision. While from that stage in which it conveys thoughts only by sounds to one or a few persons, we pass through picture-writing up to steam-printing: multiplying indefinitely the numbers communicated with, and making accessible in voluminous literatures the ideas and feelings of countless men in various places and times. Concomitantly there goes on the development of knowledge, ending in science. Numeration on the fingers grows into far-reaching mathematics; observation of the moon’s changes leads in time to a theory of the solar system; and there successively arise sciences of which not even the germs could at first be detected. Meanwhile the once few and simple customs, becoming more numerous, definite, and fixed, end in systems of laws. Rude superstitions initiate elaborate mythologies, theologies, cosmogonies. Opinion getting embodied in creeds, gets embodied, too, in accepted codes of ceremony and conduct, and in established social sentiments. And then there slowly evolve also the products we call æsthetic; which of themselves form a highly-complex group. From necklaces of fishbones we advance to dresses elaborate, gorgeous, and infinitely varied; out of discordant war-chants come symphonies and operas; cairns develop into magnificent temples; in place of caves with rude markings there arise at length galleries of paintings; and the recital of a chief’s deeds with mimetic accompaniment gives origin to epics, dramas, lyrics, and the vast mass of poetry, fiction, biography, and history.

These various orders of super-organic products, each developing within itself new genera and species while growing [I-14] into a larger whole, and each acting on the other orders while reacted on by them, constitute an immensely-voluminous, immensely-complicated, and immensely-powerful set of influences. During social evolution they are ever modifying individuals and modifying society, while being modified by both. They gradually form what we may consider either as a non-vital part of the society itself, or else as a secondary environment, which eventually becomes more important than the primary environments—so much more important that there arises the possibility of carrying on a high kind of social life under inorganic and organic conditions which originally would have prevented it.

§ 13. Such are the factors in outline. Even when presented under this most general form, the combination of them is seen to be of an involved kind.

Recognizing the primary truth that social phenomena depend in part on the natures of the individuals and in part on the forces the individuals are subject to, we see that these two fundamentally-distinct sets of factors, with which social changes commence, give origin to other sets as social changes advance. The pre-established environing influences, inorganic and organic, which are at first almost unalterable, become more and more altered by the actions of the evolving society. Simple growth of population brings into play fresh causes of transformation that are increasingly important. The influences which the society exerts on the natures of its units, and those which the units exert on the nature of the society, incessantly co-operate in creating new elements. As societies progress in size and structure, they work on one another, now by their war-struggles and now by their industrial intercourse, profound metamorphoses. And the ever-accumulating, ever-complicating super-organic products, material and mental, constitute a further set of factors which become more and more influential causes of change. So that, involved as the factors are at the beginning, each step [I-15] in advance increases the involution, by adding factors which themselves grow more complex while they grow more powerful.

But now having glanced at the factors of all orders, original and derived, we must neglect for the present those which are derived, and attend exclusively, or almost exclusively, to those which are original. The Data of Sociology, here to be dealt with, we must, as far as possible, restrict to those primary data common to social phenomena in general, and most readily distinguished in the simplest societies. Adhering to the broad division made at the outset between the extrinsic and intrinsic co-operating causes, we will consider first the extrinsic.

[I-16]

CHAPTER III.

ORIGINAL EXTERNAL FACTORS.↩

§ 14. A complete outline of the original external factors implies a knowledge of the past which we have not got, and are not likely to get. Now that geologists and archæologists are uniting to prove that human existence goes back to a time so remote that “pre-historic” scarcely expresses it, we are shown that the effects of external conditions on social evolution cannot be fully traced. Remembering that the 20,000 years, or so, during which man has lived in the Nile-valley, is made to seem a relatively-small period by the evidence that he coexisted with the extinct mammals of the drift—remembering that England had human inhabitants at an epoch which good judges think was glacial—remembering that in America, along with the bones of a Mastodon imbedded in the alluvium of the Bourbense, were found arrow-heads and other traces of the savages who had killed this member of an order no longer represented in that part of the world—remembering that, judging from the evidence as interpreted by Professor Huxley, those vast subsidences which changed a continent into the Eastern Archipelago, took place after the Negro-race was established as a distinct variety of man; we must infer that it is hopeless to trace back the external factors of social phenomena to anything like their first forms.

One important truth only, implied by the evidence thus glanced at, must be noted. Geological changes and meteorological changes, as well as the consequent changes of Floras [I-17] and Faunas, must have been causing, over all parts of the Earth, perpetual emigrations and immigrations. From each locality made less habitable by increasing inclemency, a wave of diffusion must have spread; into each locality made more favourable to human existence by amelioration of climate, or increase of indigenous food, or both, a wave of concentration must have been set up; and by great geological changes, here sinking areas of land and there raising areas, other redistributions of mankind must have been produced. Accumulating facts show that these enforced ebbings and flowings have, in some localities, and probably in most, taken place time after time. And such waves of emigration and immigration must have been ever bringing the dispersed groups of the race into contact with conditions more or less new.

Carrying with us this conception of the way in which the external factors, original in the widest sense, have co-operated throughout all past time, we must limit our attention to such effects of them as we have now before us.

§ 15. Life in general is possible only between certain limits of temperature; and life of the higher kinds is possible only within a comparatively-narrow range of temperature, maintained artificially if not naturally. Hence social life, pre-supposing as it does not only human life but that life vegetal and animal on which human life depends, is restricted by certain extremes of cold and heat.

Cold, though great, does not rigorously exclude warm-blooded creatures, if the locality supplies adequate means of generating heat. The arctic regions contain various marine and terrestrial mammals, large and small; but the existence of these depends, directly or indirectly, on the existence of the inferior marine creatures, vertebrate and invertebrate, which would cease to live there did not the warm currents from the tropics check the formation of ice. Hence such human life as we find in the far north, dependent as it is [I-18] mainly on the life of these mammals, is also remotely dependent on the same source of heat. But where, as in such places, the temperature which man’s vital functions require can be maintained with difficulty, social evolution is not possible. There can be neither a sufficient surplus-power in each individual nor a sufficient number of individuals. Not only are the energies of an Esquimaux expended mainly in guarding against loss of heat, but his bodily functions are greatly modified to the same end. Without fuel, and, indeed, unable to burn within his snow-hut anything more than an oil-lamp, lest the walls should melt, he has to keep up that warmth which even his thick fur-dress fails to retain, by devouring vast quantities of blubber and oil; and his digestive system, heavily taxed in providing the wherewith to meet excessive loss by radiation, supplies less material for other vital purposes. This great physiological cost of individual life, indirectly checking the multiplication of individuals, arrests social evolution. A kindred relation of cause and effect is shown us in the Southern hemisphere by the still-more-miserable Fuegians. Living nearly unclothed in a region of storms, which their wretched dwellings of sticks and grass do not exclude, and having little food but fish and mollusks, these beings, described as scarcely human in appearance, have such difficulty in preserving the vital balance in face of the rapid escape of heat, that the surplus for individual development is narrowly restricted, and, consequently, the surplus for producing and rearing new individuals. Hence the numbers remain too small for exhibiting anything beyond incipient social existence.

Though, in some tropical regions, an opposite extreme of temperature so far impedes the vital actions as to impede social development, yet hindrance from this cause seems exceptional and relatively unimportant. Life in general, and mammalian life along with it, is great in quantity as well as individually high, in localities that are among the [I-19] hottest. The silence of the forests during the noontide glare in such localities, does, indeed, furnish evidence of enervation; but in cooler parts of the twenty-four hours there is a compensating energy. And if varieties of the human race adapted to these localities, show, in comparison with ourselves, some indolence, this does not seem greater than, or even equal to, the indolence of the primitive man in temperate climates. Contemplated in the mass, facts do not countenance the current idea that great heat hinders progress. All the earliest recorded civilizations belonged to regions which, if not tropical, almost equal the tropics in height of temperature. India and Southern China, as still existing, show us great social evolutions within the tropics. The vast architectural remains of Java and of Cambodia yield proofs of other tropical civilizations in the East; while the extinct societies of Central America, Mexico, and Peru, need but be named to make it manifest that in the New World also, there were in past times great advances in hot regions. It is thus, too, if we compare societies of ruder types that have developed in warm climates, with allied societies belonging to colder climates. Tahiti, the Tonga Islands, and the Sandwich Islands, are within the tropics; and in them, when first discovered, there had been reached stages of evolution which were remarkable considering the absence of metals.

I do not ignore the fact that in recent times societies have evolved most, both in size and complexity, in temperate regions. I simply join with this the fact that the first considerable societies arose, and the primary stages of social development were reached, in hot climates. The truth would seem to be that the earlier phases of progress had to be passed through where the resistances offered by inorganic conditions were least; that when the arts of life had been advanced, it became possible for societies to develop in regions where the resistances were greater; and that further developments in the arts of life, with the further discipline [I-20] in co-operation accompanying them, enabled subsequent societies to take root and grow in regions which, by climatic and other conditions, offered relatively-great resistances.

We must therefore say that solar radiation, being the source of those forces by which life, vegetal and animal, is carried on; and being, by implication, the source of the forces displayed in human life, and consequently in social life; it results that there can be no considerable social evolution on tracts of the Earth’s surface where solar radiation is very feeble. Though, contrariwise, there is on some tracts a solar radiation in excess of the degree most favourable to vital actions; yet the consequent hindrance to social evolution is relatively small. Further, we conclude that an abundant supply of light and heat is especially requisite during those first stages of progress in which social vitality is small.

§ 16. Passing over such traits of climate as variability and equability, whether diurnal, annual, or irregular, all of which have their effects on human activities, and therefore on social phenomena, I will name one other climatic trait that appears to be an important factor. I refer to the quality of the air in respect of dryness or moisture.

Either extreme brings indirect impediments to civilization, which we may note before observing the direct effects. That great dryness of the air, causing a parched surface and a scanty vegetation, negatives the multiplication needed for advanced social life, is a familar fact. And it is a fact, though not a familiar one, that extreme humidity, especially when joined with great heat, may raise unexpected obstacles to progress; as, for example, in parts of East Africa, where “the springs of powder-flasks exposed to the damp snap like toasted quills; . . . paper, becoming soft and soppy by the loss of glazing, acts as a blotter; . . . metals are ever rusty; . . . and gunpowder, if not kept from the air, refuses to ignite.”

[I-21]

But it is the direct effects of different hygrometric states, which are most noteworthy—the effects on the vital processes, and, therefore, on the individual activities, and, through them, on the social activities. Bodily functions are facilitated by atmospheric conditions which make evaporation from the skin and lungs rapid. That weak persons, whose variations of health furnish good tests, are worse when the air is surcharged with water, and are better when the weather is fine; and that commonly such persons are enervated by residence in moist localities but invigorated by residence in dry ones, are facts generally recognized. And this relation of cause and effect, manifest in individuals, doubtless holds in races. Throughout temperate regions, differences of constitutional activity due to differences of atmospheric humidity, are less traceable than in torrid regions: the reason being that all the inhabitants are subject to a tolerably quick escape of water from their surfaces; since the air, though well charged with water, will take up more when its temperature, previously low, is raised by contact with the body. But it is otherwise in tropical regions where the body and the air bathing it differ much less in temperature; and where, indeed, the air is sometimes higher in temperature than the body. Here the rate of evaporation depends almost wholly on the quantity of surrounding vapour. If the air is hot and moist, the escape of water through the skin and lungs is greatly hindered; while it is greatly facilitated if the air is hot and dry. Hence in the torrid zone, we may expect constitutional differences between the inhabitants of low steaming tracts and the inhabitants of tracts parched with heat. Needful as are cutaneous and pulmonary evaporation for maintaining the movement of fluids through the tissues and thus furthering molecular changes, it is to be inferred that, other things equal, there will be more bodily activity in the people of hot and dry localities than in the people of hot and humid localities.

[I-22]

The evidence justifies this inference. The earliest-recorded civilization grew up in a hot and dry region—Egypt; and in hot and dry regions also arose the Babylonian, Assyrian, and Phœnician civilizations. But the facts when stated in terms of nations are far less striking than when stated in terms of races. On glancing over a general rain-map, there will be seen an almost-continuous area marked “rainless district,” extending across North Africa, Arabia, Persia, and on through Thibet into Mongolia; and from within, or from the borders of, this district, have come all the conquering races of the Old World. We have the Tartar race, which, passing the Southern mountain-boundary of this rainless district, peopled China and the regions between it and India—thrusting the aborigines of these areas into the hilly tracts; and which has sent successive waves of invaders not into these regions only, but into the West. We have the Aryan race, overspreading India and making its way through Europe. We have the Semitic race, becoming dominant in North Africa, and, spurred on by Mahommedan fanaticism, subduing parts of Europe. That is to say, besides the Egyptian race, which became powerful in the hot and dry valley, of the Nile, we have three races widely unlike in type, which, from different parts of the rainless district have spread over regions relatively humid. Original superiority of type was not the common trait of these peoples: the Tartar type is inferior, as was the Egyptian. But the common trait, as proved by subjugation of other peoples, was energy. And when we see that this common trait in kinds of men otherwise unlike, had for its concomitant their long-continued subjection to these special climatic conditions—when we find, further, that from the region characterized by these conditions, the earlier waves of conquering emigrants, losing in moister countries their ancestral energy, were over-run by later waves of the same kind of men, or of other kinds, coming from this region; we get strong reason for inferring a relation [I-23] between constitutional vigour and the presence of an air which, by its warmth and dryness, facilitates the vital actions. A striking verification is at hand. The rain-map of the New World shows that the largest of the parts distinguished as almost rainless, is that Central-American and Mexican region in which indigenous civilizations developed; and that the only other rainless district is that part of the ancient Peruvian territory, in which the pre-Ynca civilization has left its most conspicuous traces. Inductively, then, the evidence justifies in a remarkable manner the physiological deduction. Nor are there wanting minor verifications. Speaking of the varieties of negroes, Livingstone says—“Heat alone does not produce blackness of skin, but heat with moisture seems to insure the deepest hue”; and Schweinfurth remarks on the relative blackness of the Denka and other tribes living on the alluvial plains, and contrasts them with “the less swarthy and more robust races who inhabit the rocky hills of the interior”: differences with which there go differences of energy. But I note this fact for the purpose of suggesting its probable connexion with the fact that the lighter-skinned races are habitually the dominant races. We see it to have been so in Egypt. It was so with the races spreading south from Central Asia. Traditions imply that it was so in Central America and Peru. Speke says:—“I have always found the lighter-coloured savages more boisterous and warlike than those of a dingier hue.” And if, heat being the same, darkness of skin accompanies humidity of the air, while lightness of skin accompanies dryness of the air, then, in this habitual predominance of the fair varieties of men, we find further evidence that constitutional activity, and in so far social development, is favoured by a climate conducing to rapid evaporation.

I do not mean that the energy thus resulting determines, of itself, higher social development: this is neither implied deductively nor shown inductively. But greater energy, [I-24] making easy the conquest of less active races and the usurpation of their richer and more varied habitats, also makes possible a better utilization of such habitats.

§ 17. On passing from climate to surface, we have to note, first, the effects of its configuration, as favouring or hindering social integration.

That the habits of hunters or nomads may be changed into those required for settled life, the surface occupied must be one within which coercion is easy, and beyond which the difficulties of existence are great. The unconquerableness of mountain tribes, difficult to get at, has been in many times and in many places exemplified. Instance the Illyrians, who remained independent of the adjacent Greeks, gave trouble to the Macedonians, and mostly recovered their independence after the death of Alexander; instance the Montenegrins; instance the Swiss; instance the people of the Caucasus. The inhabitants of desert-tracts, as well as those of mountain-tracts, are difficult to consolidate: facility of escape, joined with ability to live in sterile regions, greatly hinder social subordination. Within our own island, surfaces otherwise widely unlike have similarly hindered political integration, when their physical traits have made it difficult to reach their occupants. The history of Wales shows us how, within that mountainous district itself, subordination to one ruler was hard to establish; and still more how hard it was to bring the whole under the central power: from the Old-English period down to 1400, eight centuries of resistance passed before the subjugation was complete, and a further interval before the final incorporation with England. The Fens, in the earliest times a haunt of marauders and of those who escaped from established power, became, at the time of the Conquest, the last refuge of the still-resisting English; who, for many years, maintained their freedom in this tract, made almost inaccessible by morasses. The prolonged independence of the [I-25] Highland clans, who were subjugated only after General Wade’s roads put their refuges within reach, yields a later proof. Conversely, social integration is easy within a territory which, while able to support a large population, affords facilities for coercing the units of that population: especially if it is bounded by regions offering little sustenance, or peopled by enemies, or both. Egypt fulfilled these conditions in a high degree. Governmental force was unimpeded by physical obstacles within the occupied area; and escape from it into the adjacent desert involved either starvation or robbery and enslavement by wandering hordes. Then in small areas surrounded by the sea, such as the Sandwich Islands, Tahiti, Tonga, Samoa, where a barrier to flight is formed by a desert of water instead of a desert of sand, the requirements are equally well fulfilled. Thus we may figuratively say that social integration is a process of welding, which can be effected only when there are both pressure and difficulty in evading that pressure. And here, indeed, we are reminded how, in extreme cases, the nature of the surface permanently determines the type of social life it bears. From the earliest recorded times, arid tracts in the East have been peopled by Semitic tribes having an adapted social type. The description given by Herodotus of the Scythian’s mode of life and social organization, is substantially the same as that given of the Kalmucks by Pallas. Even were regions fitted for nomads to have their inhabitants exterminated, they would be re-peopled by refugees from neighbouring settled societies; who would similarly be compelled to wander, and would similarly acquire fit forms of union. There is, indeed, a modern instance in point: not exactly of a re-genesis of an adapted social type, but of a genesis de novo. Since the colonization of South America, some of the pampas have become the homes of robber-tribes like Bedouins.

Another trait of the inhabited area to be noted as influential, is its degree of heterogeneity. Other things equal, [I-26] localities that are uniform in structure are unfavourable to social progress. Leaving out for the present its effects on the Flora and Fauna, sameness of surface implies absence of varied inorganic materials, absence of varied experiences, absence of varied habits, and, therefore, puts obstacles to industrial development and the arts of life. Neither Central Asia, nor Central Africa, nor the central region of either American continent, has been the seat of an indigenous civilization of any height. Regions like the Russian steppes, however possible it may be to carry into them civilization elsewhere developed, are regions within which civilization is not likely to be initiated; because the differentiating agencies are insufficient. When quite otherwise caused, uniformity of habitat has still the like effect. As Professor Dana asks respecting a coral-island:—

“How many of the various arts of civilized life could exist in a land where shells are the only cutting instruments . . . fresh water barely enough for household purposes,—no streams, nor mountains, nor hills? How much of the poetry and literature of Europe would be intelligible to persons whose ideas had expanded only to the limits of a coral-island, who had never conceived of a surface of land above half a mile in breadth—of a slope higher than a beach, or of a change in seasons beyond a variation in the prevalence of rain?”

Contrariwise, the influences of geological and geographical heterogeneity in furthering social development, are conspicuous. Though, considered absolutely, the Nile-valley is not physically multiform, yet it is multiform in comparison with surrounding tracts; and it presents that which seems the most constant antecedent to civilization—the juxtaposition of land and water. Though the Babylonians and Assyrians had habitats that were not specially varied, yet they were more varied than the riverless regions lying East and West. The strip of territory in which the Phœnician society arose, had a relatively-extensive coast; many rivers furnishing at their mouths sites for the chief cities; plains and valleys running inland, with hills between them and [I-27] mountains beyond them. Still more does heterogeneity distinguish the area in which the Greek society evolved: it is varied in its multitudinous and complex distributions of land and sea, in its contour of surface, in its soil. “No part of Europe—perhaps it would not be too much to say no part of the world—presents so great a variety of natural features within the same area as Greece.” The Greeks themselves, indeed, observed the effects of local circumstances in so far as unlikeness between coast and interior goes. As says Mr. Grote:—

“The ancient philosophers and legislators were deeply impressed with the contrast between an inland and a maritime city: in the former simplicity and uniformity of life, tenacity of ancient habits and dislike of what is new and foreign, great force of exclusive sympathy and narrow range both of objects and ideas: in the latter, variety and novelty of sensations, expansive imagination, toleration and occasional preference for extraneous customs, greater activity of the individual and corresponding mutability of the state.”

Though the differences here described are mainly due to absence and presence of foreign intercourse; yet, since this itself is dependent on the local relations of land and sea, these relations must be recognized as primary causes of the differences. Just observing that in Italy likewise, civilization found a seat of considerable complexity, geological and geographical, we may pass to the New World, where we see the same thing. Central America, which was the source of its indigenous civilizations, is characterized by comparative multiformity. So, too, with Mexico and with Peru. The Mexican tableland, surrounded by mountains, contained many lakes: that of Tezcuco, with its islands and shores, being the seat of Government; and through Peru, varied in surface, the Ynca-power spread from the mountainous islands of the large, irregular, elevated lake, Titicaca.

How soil affects progress remains to be observed. The belief that easy obtainment of food is unfavourable to social evolution, while not without an element of truth, is by no [I-28] means true as currently accepted. The semi-civilized peoples of the Pacific—the Sandwich Islanders, Tahitians, Tongans, Samoans, Fijians—show us considerable advances made in places where great productiveness renders life unlaborious. In Sumatra, where rice yields 80 to 140 fold, and in Madagascar, where it yields 50 to 100 fold, social development has not been insignificant. Kaffirs, inhabiting a tract having rich and extensive pasturage, contrast favourably, both individually and socially, with neighbouring races occupying regions that are relatively unproductive; and those parts of Central Africa in which the indigenes have made most social progress, as Ashantee and Dahomey, have luxuriant vegetations. Indeed, if we call to mind the Nile-valley, and the exceptionally-fertilizing process it is subject to, we see that the most ancient social development known to us, began in a region which, fulfilling other requirements, was also characterized by great natural productiveness.

And here, with respect to fertility, we may recognize a truth allied to that which we recognized in respect to climate; namely, that the earlier stages of social evolution are possible only where the resistances to be overcome are small. As those arts of life by which loss of heat is prevented, must be considerably advanced before relatively-inclement regions can be well peopled; so, the agricultural arts must be considerably advanced before the less fertile tracts can support populations large enough for civilization. And since arts of every kind develop only as societies progress in size and structure, it follows that there must be societies having habitats where abundant food can be procured by inferior arts, before there can arise the arts required for dealing with less productive habitats. While yet low and feeble, societies can survive only where the circumstances are least trying. The ability to survive where circumstances are more trying can be possessed only by the higher and stronger societies descending from these; and inheriting [I-29] their acquired organization, appliances, and knowledge.

It should be added that variety of soil is a factor of importance; since this helps to cause that multiplicity of vegetal products which largely aids social progress. In sandy Damara-land, where four kinds of mimosas exclude nearly every other kind of tree or bush, it is clear that, apart from further obstacles to progress, paucity of materials must be a great one. But here we verge upon another order of factors.

§ 18. The character of its Flora affects in a variety of ways the fitness of a habitat for supporting a society. At the chief of these we must glance.

Some of the Esquimaux have no wood at all; while others have only that which comes to them as ocean-drift. By using snow or ice to build their houses, and by the shifts they are put to in making cups of seal-skin, fishing-lines and nets of whalebone, and even bows of bone or horn, these people show us how greatly advance in the arts of life is hindered by lack of fit vegetal products. With this Arctic race, too, as also with the nearly Antarctic Fuegians, we see that the absence or extreme scarcity of useful plants is an insurmountable impediment to social progress. Evidence better than that furnished by these regions (where extreme cold is a coexisting hindrance) comes from Australia; where, in a climate that is on the whole favourable, the paucity of plants available for the purposes of life has been a part-cause of continued arrest at the lowest stage of barbarism. Large tracts of it, supporting but one inhabitant to sixty square miles, admit of no approach to that populousness which is a needful antecedent to civilization.

Conversely, after observing how growth of population, making social advance possible, is furthered by abundance of vegetal products, we may observe how variety of vegetal products conduces to the same effect. Not only in the cases [I-30] of the slightly-developed societies occupying regions covered by a heterogeneous Flora, do we see that dependence on many kinds of roots, fruits, cereals, etc., is a safeguard against the famines caused by failure of any single crop; but we see that the materials furnished by a heterogeneous Flora, make possible a multiplication of appliances, a consequent advance of the arts, and an accompanying development of skill and intelligence. The Tahitians have on their islands, fit woods for the frameworks and roofs of houses, with palm-leaves for thatch; there are plants yielding fibres out of which to twist cords, fishing-lines, matting, etc.; the tapa-bark, duly prepared, furnishes a cloth for their various articles of dress; they have cocoa-nuts for cups, etc., materials for baskets, sieves, and various domestic implements; they have plants giving them scents for their unguents, flowers for their wreaths and necklaces; they have dyes for stamping patterns on their dresses—all besides the various foods, bread-fruit, taro, yams, sweet-potatoes, arrow-root, fern-root, cocoa-nuts, plantains, bananas, jambo, ti-root, sugar-cane, etc.: enabling them to produce numerous made dishes. And the utilization of all these materials implies a culture which in various ways furthers social advance. Kindred results from like causes have arisen among an adjacent people, widely unlike in character and political organization. In a habitat characterized by a like variety of vegetal products, those ferocious cannibals the Fijians, have developed their arts to a degree comparable with that of the Tahitians, and have a division of labour and a commercial organization that are even superior. Among the thousand species of indigenous plants in the Fiji Islands, there are such as furnish materials for all purposes, from the building of war-canoes carrying 300 men down to the making of dyes and perfumes. It may, indeed, be urged that the New Zealanders, exhibiting a social development akin to that reached in Tahiti and Fiji, had a habitat of which the indigenous Flora was not varied. But the reply is that [I-31] both by their language and their mythology, the New Zealanders are shown to have separated from other Malayo-Polynesians after the arts of life had been considerably advanced; and that they brought these arts (as well as some cultivated plants) to a region which, though poor in edible plants, supplied in abundance plants otherwise useful.

As above hinted, mere luxuriance of vegetation is in some cases a hindrance to progress. Even that inclement region inhabited by the Fuegians, is, strange to say, made worse by the dense growth of useless underwood which clothes the rocky hills. Living though they do under conditions otherwise so different, the Andamanese, too, are restricted to the borders of the sea, by the impenetrable thickets which cover the land. Indeed various equatorial regions, made almost useless even to the semi-civilized by jungle and tangled forest, were utterly useless to the aborigines, who had no tools for clearing the ground. The primitive man, possessing rude stone implements only, found but few parts of the Earth’s surface which, neither too barren nor bearing too luxuriant a vegetation, were available: so again reminding us that rudimentary societies are at the mercy of environing conditions.

§ 19. There remains to be treated the Fauna of the region inhabited. Evidently this affects greatly both the degree of social growth and the type of that growth.

The presence or absence of wild animals fit for food, influential as it is in determining the kind of individual life, is therefore influential in determining the kind of social organization. Where, as in North America, there existed game enough to support the aboriginal races, hunting continued the dominant activity; and a partially-nomadic habit being entailed by migrations after game, there was a persistent impediment to agriculture, to increase of population, and to industrial development. We have but to consider the antithetical case of the various Polynesian races, and to [I-32] observe how, in the absence of a considerable land-Fauna, they have been forced into agriculture with its concomitant settled life, larger population, and advanced arts, to see how great an effect the kind and amount of utilizable animal-life has on civilization. When we glance at that pastoral type of society which, still existing, has played in past times an important part in human progress, we again see that over wide regions the indigenous Fauna has been chiefly influential in fixing the form of social union. On the one hand, in the absence of herbivores admitting of domestication—horses, camels, oxen, sheep, goats—the pastoral life followed by the three great conquering races in their original habitats, would have been impossible; and, on the other hand, this kind of life was inconsistent with that formation of larger settled unions which is needed for the higher social relations. On recalling the cases of the Laplanders with their reindeer and dogs, the Tartars with their horses and cattle, and the South Americans with their llamas and guinea-pigs, it becomes obvious, too, that in various cases this nature of the Fauna, joined with that of the surface, still continues to be a cause of arrest at a certain stage of evolution.

While the Fauna as containing an abundance or scarcity of creatures useful to man is an important factor, it is also an important factor as containing an abundance or scarcity of injurious creatures. The presence of the larger carnivores is, in some places, a serious impediment to social life; as in Sumatra, where villages are not uncommonly depopulated by tigers; as in India, where “a single tigress caused the destruction of 13 villages, and 250 square miles of country were thrown out of cultivation,” and where “in 1869 one tigress killed 127 people, and stopped a public road for many weeks.” Indeed we need but recall the evils once suffered in England from wolves, and those still suffered in some parts of Europe, to see that freedom to carry on out-door occupations and intercourse, which is among the conditions [I-33] to social advance, may be hindered by predatory animals. Nor must we forget how greatly agriculture is occasionally interfered with by reptiles; as, again, in India, where over 25,000 persons die of snake-bite annually. To which evils directly inflicted by the higher animals, must be added the indirect evils which they join insects in inflicting, by destroying crops. Sometimes injuries of this last kind considerably affect the mode of individual life and consequently of social life; as in Kaffirland, where crops are subject to great depredations from mammals, birds, and insects, and where the transformation of the pastoral state into a higher state is thus discouraged; or as in the Bechuana-country, which, while “peopled with countless herds of game, is sometimes devastated by swarms of locusts.” Clearly, where the industrial tendencies are feeble, uncertainty in getting a return for labour must hinder the development of them, and cause reversion to older modes of life, if these can still be pursued.

Many other mischiefs, caused especially by insects, seriously interfere with social progress. Even familiar experiences in Scotland, where the midges sometimes drive one indoors, show how greatly “the plague of flies” must, in tropical regions, impede outdoor labour. Where, as on the Orinoco, the morning salutation is—“How are we to-day for the mosquitos?” and where the torment is such that a priest could not believe Humboldt voluntarily submitted to it merely that he might see the country, the desire for relief must often out-balance the already-feeble motive to work. Even the effects of flies on cattle indirectly modify social life; as among the Kirghiz, who, in May, when the steppes are covered with rich pasture, are obliged by the swarms of flies to take their herds to the mountains; or as in Africa, where the tsetse negatives the pastoral occupation in some localities. And then, in other cases, great discouragement results from the termites, which, in parts of East Africa, consume dress, furniture, beds, etc. “A man may be rich to-day [I-34] and poor to-morrow, from the ravages of the white ants,” said a Portuguese merchant to Livingstone. Nor is this all. Humboldt remarks that where the termites destroy all documents, there can be no advanced civilization.

Thus there is a close relation between the type of social life indigenous in a locality, and the character of the indigenous Fauna. The presence or absence of useful species, and the presence or absence of injurious species, have their favouring and hindering effects. And there is not only so produced a furtherance or retardation of social progress, generally considered, but there is produced more or less speciality in the structures and activities of the community.