The COPY of a PAPER Deliver'd to the SHERIFFS, Upon the Scaffold on Tower-hill, On Friday Decemb. 7. 1683. BY Algernon Sidney Esq Immediately before his Death.

|

|

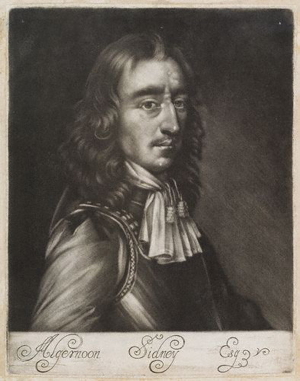

This is part of a collection of works by Algernon Sidney.

Source

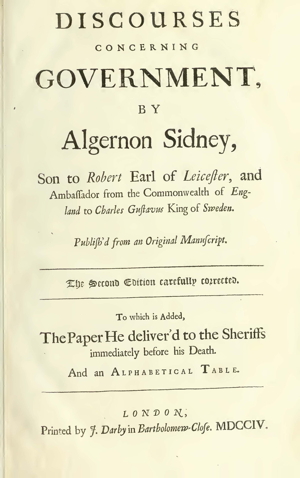

Discourses Concerning Government, by Algernon Sidney, Son to Robert Earl of Leicester, and Ambassador from the Commonwealth of England to Charles Gustavus King of Sweden. Published from an Original Manuscript. The Second Edition carefully corrected. To which is Added. The Paper He deliver's to the Sheriffs immediately before his Death. And an Alphabetical Table. Dulce et decorum est pro Patria mori. Hor. (London,

Printed by J. Darby in Batholomew Close, 1704). "The COPY of a PAPER Deliver'd to the SHERIFFS, Upon the Scaffold on Tower-hill, On Friday Decemb. 7. 1683. BY Algernon Sidney Esq Immediately before his Death," pp. 421-24. Whole book facs. PDF. "Copy of a Paper" facs. PDF.

Introduction

This short piece was added to the second edition of the Discourses which was published six years after the first edition (1698). It contains a very nice sumamry of what he thinks the "Old Cause" of republcanism stands for (p. 422):

If he might publish to the World his Opinion, That all Men are born under a necessity deriv'd from the Laws of God and Nature, to submit to an Absolute Kingly Government, which could be restrain'd by no Law, or Oath; and that he that has the Power, whether he came to it by Creation, Election, Inheritance, Usurpation, or any other way, had the Right; and none must oppose his Will, but the Persons and Estates of his Subjects must be indispensably subject unto it; I know not why I might not have publish'd my Opinion to the contrary, without the breach of any Law I have yet known.

I might as freely as he, publickly have declar'd my Thought, and the reasons upon which they were grounded, and I persuaded to believe, That God had left Nations to the Liberty of setting up such Governments as best pleas'd themselves.

That Magistrates were set up for the good of Nations, not Nations for the honour or glory of Magistrates.

That the Right and Power of Magistrates in every Country, was that which the Laws of that Country made it to be.

That those Laws were to be observ'd, and the Oaths taken by them, having the force of a Contract between Magistrate and People, could not be violated without danger of dissolving the whole Fabrick.

That Usurpation could give no Right, and the most dangerous of all Enemys to Kings were they, who raising their Power to an exorbitant height, allow'd to Usurpers all the Rights belonging unto it.

That such Usurpations being seldom compass'd without the Slaughter of the Reigning Person, or Family, the worst of all Villanys was thereby rewarded with the most glorious Privileges.

That if such Doctrines were receiv'd, they would stir up Men to the Destruction of Princes with more Violence than all the Passions that have hitherto rag'd in the Hearts of the most Unruly.

That none could be safe, if such a Reward were propos'd to any that could destroy them.

That few would be so gentle as to spare even the Best, if by their destruction a wild Usurper could become God's Anointed, and by the most execrable Wickedness invest himself with that Divine Character.

This is the scope of the whole Treatise; the Writer gives such Reasons as at present did occur unto him, to prove it.

Text

[421]

Men, Brethren, and Fathers; Friends, Countrymen, and Strangers:

IT May be expected that I should now say some great matters unto you; but the Rigor of the Season, and the Infirmitys of my Age, increas'd by a close Imprisonment of above five Months, do not permit me.

Moreover, we live in an Age that makes Truth pass for Treason: I dare not say any thing contrary unto it, and the Ears of those that are about me will probably be found too tender to hear it. My Trial and Condemnation doth sufficiently evidence this.

West, Rumsey, and Keyling, who were brought to prove the Plot, said no more of me, than that they knew me not; and some others equally unknown to me, had us'd my Name, and that of some others, to give a little Reputation to their Designs. The Lord Howard is too infamous by his Life, and the many Perjurys not to be deny'd, or rather sworn by himself, [422] to deserve mention; and being a single Witness would be of no value, tho he had been of unblemish'd Credit, or had not seen and confess'd that the Crimes committed by him would be pardon'd only for committing more; and even the Pardon promis'd could not be obtain'd till the drudgery of Swearing was over.

This being laid aside, the whole matter is reduc'd to the Papers said to be found in my Closet by the King's Officers, without any other Proof of their being written by me, than what is taken from suppositions upon the similitude of an Hand that is easily counterfeited, and which hath been lately declar'd in the Lady Car's Case to be no lawful Evidence in Criminal Causes.

But if I had been seen to write them, the matter would not be much alter'd. They plainly appear to relate to a large Treatise written long since in Answer to Filmer's Book, which by all Intelligent Men is thought to be grounded upon wicked Principles, equally pernicious to Magistrates and People.

If he might publish to the World his Opinion, That all Men are born under a necessity deriv'd from the Laws of God and Nature, to submit to an Absolute Kingly Government, which could be restrain'd by no Law, or Oath; and that he that has the Power, whether he came to it by Creation, Election, Inheritance, Usurpation, or any other way, had the Right; and none must oppose his Will, but the Persons and Estates of his Subjects must be indispensably subject unto it; I know not why I might not have publish'd my Opinion to the contrary, without the breach of any Law I have yet known.

I might as freely as he, publickly have declar'd my Thought, and the reasons upon which they were grounded, and I persuaded to believe, That God had left Nations to the Liberty of setting up such Governments as best pleas'd themselves.

That Magistrates were set up for the good of Nations, not Nations for the honour or glory of Magistrates.

That the Right and Power of Magistrates in every Country, was that which the Laws of that Country made it to be.

That those Laws were to be observ'd, and the Oaths taken by them, having the force of a Contract between Magistrate and People, could not be violated without danger of dissolving the whole Fabrick.

That Usurpation could give no Right, and the most dangerous of all Enemys to Kings were they, who raising their Power to an exorbitant height, allow'd to Usurpers all the Rights belonging unto it.

That such Usurpations being seldom compass'd without the Slaughter of the Reigning Person, or Family, the worst of all Villanys was thereby rewarded with the most glorious Privileges.

That if such Doctrines were receiv'd, they would stir up Men to the Destruction of Princes with more Violence than all the Passions that have hitherto rag'd in the Hearts of the most Unruly.

That none could be safe, if such a Reward were propos'd to any that could destroy them.

That few would be so gentle as to spare even the Best, if by their destruction a wild Usurper could become God's Anointed, and by the most execrable Wickedness invest himself with that Divine Character.

This is the scope of the whole Treatise; the Writer gives such Reasons as at present did occur unto him, to prove it. This seems to agree [423] with the Doctrines of the most Reverenc'd Authors of all Times, Nations and Religions. The best and wisest of Kings have ever acknowledg'd it. The present King of France has declar'd that Kings have that happy want of Power, that they can do nothing contrary to the Laws of their Country, and grounds his Quarrel with the King of Spain, Anno 1667. upon that Principle. King James in his Speech to the Parliament Anno 1603. doth in the highest degree assert it: The Scripture seems to declare it. If nevertheless the Writer was mistaken, he might have been refuted by Law, Reason and Scripture; and no Man for such matters was ever otherwise punish'd, than by being made to see his Error; and it has not (as I think) been ever known that they had been refer'd to the Judgment of a Jury, compos'd of Men utterly unable to comprehend them.

But there was little of this in my Case; the extravagance of my Prosecutors goes higher: the above-mention'd Treatise was never finish'd, nor could be in many years, and most probably would never have been. So much as is of it was written long since, never review'd nor shewn to any Man; and the fiftieth part of it was not produc'd, and not the tenth of that offer'd to be read. That which was never known to those who are said to have conspir'd with me, was said to be intended to stir up the People in Prosecution of the Designs of those Conspirators.

When nothing of particular Application to Time, Place, or Person, could be found in it, (as has ever been done by those who endeavour'd to raise Insurrections) all was supply'd by Innuendo's.

Whatsoever is said of the Expulsion of Tarquin; the Insurrection against Nero; the Slaughter of Caligula, or Domitian; the Translation of the Crown of France from Meroveus his Race to Pepin, and from his Descendents to Hugh Capet, and the like, was apply'd by Innuendo to the King.

They have not consider'd, that if such Acts of State be not good, there is not a King in the World that has any Title to the Crown he wears; nor can have any, unless he could deduce his Pedegree from the eldest Son of Noah, and shew that the Succession had still continu'd in the eldest of the eldest Line, and been so deduc'd to him.

Every one may see what advantage this would be to all the Kings of the World; and whether that failing, it were not better for them to acknowledg they had receiv'd their Crowns by the Consent of willing Nations, or to have no better Title to them than Usurpation and Violence, which by the same ways may be taken from them.

But I was long since told that I must die, or the Plot must die.

Lest the means of destroying the best Protestants in England should fail, the Bench must be fill'd with such as had been Blemishes to the Bar.

None but such as these would have advis'd with the King's Council of the means of bringing a Man to death; suffer'd a Jury to be pack'd by the King's Solicitors, and the Under-Sheriff; admit of Jury men who are not Freeholders; receive such Evidence as is above mention d; refuse a Copy of an Indictment, or suffer the Statute of 46 Edw. 3. to be read, that doth expresly Enact, It should in no case be deny'd to any Man upon any occasion whatsoever; over-rule the most important Points of Law without hearing. And whereas the Statute, 25 Ed. 3. [424] upon which they said I should be try'd, doth reserve to the Parliament all Constructions to be made in Points of Treason, they could assume to themselves not only a Power to make Constructions, but such Constructions as neither agree with Law, Reason, or common Sense.

By these means I am brought to this Place. The Lord forgive these Practices, and avert the Evils that threaten the Nation from them. The Lord sanctify these my Sufferings unto me; and tho I fall as a Sacrifice to Idols, suffer not Idolatry to be establish'd in this Land. Bless thy People, and save them. Defend thy own Cause, and defend those that defend it. Stir up such as are faint; direct those that are willing; confirm those that waver; give Wisdom and Integrity unto all. Order all things so as may most redound to thine own Glory. Grant that I may die glorifying Thee for all thy Mercys, and that at the last Thou hast permitted me to be singl'd out as a Witness of thy Truth, and even by the Confession of my Opposers, for that OLD CAUSE in which I was srom my Youth engag'd, and for which Thou hast often and wonderfully declar'd thy Self.