JAMES MILL,

Commerce Defended. An answer to the arguments ... that commerce is not a source of national wealth (1808)

|

|

| James Mill (1773-1836) |

[Created: 12 May, 2023]

[Updated: April 19, 2024 ] |

The Guillaumin Collection

|

This title is part of “The Guillaumin Collection” within “The Digital Library of Liberty and Power”. It has been more richly coded and has some features which other titles in the library do not have, such as the original page numbers, formatting which makes it look as much like the original text as possible, and a citation tool which makes it possible for scholars to link to an individual paragraph which is of interest to them. These titles are also available in a variety of eBook formats for reading on portable devices. |

Source

, Commerce Defended. An answer to the arguments by which Mr. Spence, Mr. Cobbett, and others, have attempted to prove that commerce is not a source of national wealth (London: Baldwin, 1808).http://davidmhart.com/liberty/EnglishClassicalLiberals/MillJames/1808-CommerceDefended/index.html

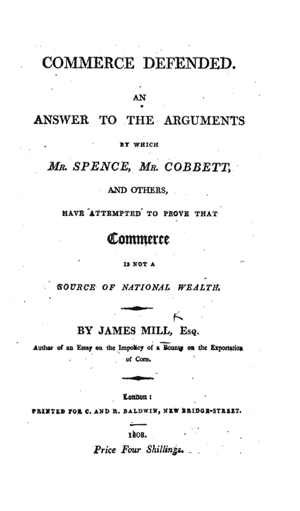

James Mill, Commerce Defended. An answer to the arguments by which Mr. Spence, Mr. Cobbett, and others, have attempted to prove that commerce is not a source of national wealth. By James Mill, Esq. Author of an Essay on the Impolicy of a Bounty on the Exportation of Corn. (London: Printed for C. and R. Baldwin, New Bridge-street. 1808). Price four shillings.

This title is also available in a facsimile PDF of the original and various eBook formats - HTML, PDF, and ePub.

This book is part of a collection of works by James Mill (1773-1836).

Table of Contents

- Introduction, p. 1

- CHAP. I. On the Security or Insecurity of the British Commerce, p. 7

- CHAP. II. On Land as a Source of Whealth, p. 13

- CHAP. III. Of the Definition of the Terms Wealth and Prosperity, p. 17

- CHAP. IV. Of Manufactures, p. 23

- CHAP. V. Commerce, p. 31

- Article I. Commerce of Import, p. 32

- Article II. Commerce of Export, p. 39

- CHAP, VI. Consumption, p. 65

- CHAP. VII. Of the National Debt, p. 89

- General Reflections, p. 104

- Endnotes

COMMERCE DEFENDED,

&c. &c.

[1]

INTRODUCTION.↩

Rousseau confessed to Mr. Hume, and Mr. Hume repeated the conversation to Mr. Burke, that the secret of which he availed himself in his writings to excite the attention of mankind, was the employment of paradoxes. When a proposition is so expressed as to bear the appearance of absurdity, but by certain reasonings and explanations is made to assume the semblance of truth, the inexperienced hearers are, in general, wonderfully delighted, give credit to the author for the highest ingenuity, and congratulate themselves on a surprising discovery.

When these paradoxes are so contrived as to harmonize with any prevailing sentiment or passion of the times, their reception is so much the more eager and general. Thus, had the paradox, that commerce is absolutely unproductive of wealth, been recommended to the people of this country some years ago, when they were taught to triumph in the increase of their commerce, and to look to it as the means of humbling the revolutionary pride of France, it would have been the object either of neglect or of ridicule. At present, [2] when difficulties and dangers have encreased around this commerce, and fears are abroad that it may even be cut off, the new doctrine that we shall not suffer by its loss, falls in so conveniently with our apprehensions, that it appears extremely agreeable and consolatory. Being a doctrine at once paradoxical and flattering, no more is wanting to render it popular.

It is to be suspected, however, that this would not afford a very safe principle on which to regulate the great interests of the nation. Our navy, for example, weighty as its ascendancy must be deemed, may now, when the whole continent of civilized Europe is at the disposal of its determined enemy, be regarded as exposed to dangers, greater, perhaps than ever threatened it before. Could we, in a moment of despondency, permit ourselves to think, that, like our commerce, it might be ruined by this enemy, should our wisdom consist in trying to persuade ourselves that it was of no value, and that we ought to part from it without regret? Ireland⁁ too, considering the power of the enemy who desires to attack it, and the commotions by which it is agitated within, is unquestionably in greater danger of being wrested from us at this moment, than at any late period of our history. What then? Should we consider any man as acting a patriotic or prudent part, who should labour to persuade us that Ireland is of little or no value, and should it fall into the hands of Bonaparte, that the loss we should sustain would be of little avail? We should, on the other hand, join in [3] condemning his misguided and preposterous zeal; for however we might rest assured that neither Ireland nor our navy would be voluntarily, any more than our commerce, resigned to Bonaparte, yet we might fear that such a doctrine becoming popular would induce our Cabinets and Parliaments, which are not always led by the wisest men in the nation, to neglect those essential interests more than they otherwise would have done.

This is precisely the danger which threatens commerce at the present moment, and which is the more alarming, the greater the difficulties by which it is surrounded, and the more delicate and easily affected the interests which it involves. Agriculture is hardy and independent. The powers of the earth, and the first necessities of man, insure to this a certain prosperity, proportionate to the state of industry in the nation, in spite of the neglect, and even the discouragement of the public rulers. But should the legislature become influenced by a theory hostile to commerce, at a time when other circumstances conspire against it, the affairs of the nation might easily receive a turn, which would soon terminate her grandeur as the mistress of trade.

The propagators of this doctrine, which has met with a more favourable reception in this commercial country than beforehand one could have easily imagined, are, as yet, but two, Mr. Spence and Mr. Cobbett.

Mr. Spence has written a pamphlet, in which, after exhibiting in as high colours as he possibly [4] can the value which is vulgarly set upon commerce in this country, he endeavours to shew that it will certainly, or at least very probably, be torn from us by Bonaparte; that it is however altogether destitute of value; and that our wealth and prosperity are intrinsic. To establish these conclusions Mr. Spence attempts to revive the system of the Economistes, a sect of political philosophers who arose in France about the middle of the last century, and who, in opposition to the mercantile doctrine, that all wealth is derived from commerce, or rather a favourable balance of commerce, taught that all wealth is derived from land. He proposes indeed a limitation upon the ideas of that sect, in one particular instance, from which however he seems to waver in other parts of his discourse; but the main object of the pamphlet, as he expressly states, is to apply the doctrine of the Economistes to the present circumstances of this country. Mr. Spence appears from his pamphlet to have a considerable turn for abstract thinking, and to be a man of pretty extensive reading in political economy. But his mind has not been trained in the logic of enlarged and comprehensive views. He does not judge of an extensive and complicated subject from an exact knowledge of all its parts, of their various connections, and relative importance. It is enough for him to seize some leading object, or some striking relation, and from these to draw conclusions with ingenuity to the whole.

Mr, Cobbett is an author who deals more in [5] assertion than proof; and therefore a writer who gives reasons for what Mr. Cobbett affirms, is a very convenient coadjutor. He seems, accordingly, to have been charmed with the appearance of Mr, Spence's pamphlet; and has republished the principal part of that gentleman's reasonings, in his Political Register. Even the assertions of Mr. Cobbett, I am by no means disposed to treat with neglect. He seems to form his opinions more frequently from a sort of intuition, than from argument. His mind is but little accustomed to spread out, as it were, before itself, the intermediate ideas on which its conclusions are founded; and the nature of the education which it has received, from its own unaided progress and exertions, sufficiently accounts for this peculiarity. It does not follow that his opinions are not founded on evidence, and that they do not frequently exhibit much sagacity. It is often the form, rather than the matter, in which he is deficient. Even on some pretty difficult questions of political economy, (those, for example, respecting the corn-trade,) he has discovered a clearness and justness of thought, which but few of our scientific reasoners have, reached. On a subject, more perverted at least by passion, the structure of society, his mind, untainted by theory, or rather emancipated by its own vigour and honesty from a pernicious theory which it had imbibed, has seized the doctrines of wisdom and prosperity, without the aid of many examples. He has assumed the patronage of the poor, at a time when they are [6] depressed below the place which they have fortunately held in this country for a century, and when the current of our policy runs to depress them still farther. At a lime, too, when every tongue and every pen seem formed to adulation, when nothing is popular but praises of men in power, and whatever tendency to corruption may exist receives in this manner double encouragement, he has the courage boldly to arraign the abuses of government and the vices of the great. This is a distinction which, with all his defects, ranks him among the most eminent of his countrymen.

Such are the two authors whose doctrines, respecting the value of commerce, have at present attained no little celebrity; and whose reasonings it will be a principal part of our business, in the following pages, to examine.

[7]

CHAPTER I.

On the Security or Insecurity of the British Commerce.↩

Both of these Authors preface their inquiries into the value of commerce, by an attempt to persuade us that the commerce of this country has become extremely insecure. This is not exactly the most philosophical course, as it is taking aid from our fears in support of their argument. Mr. Spence informs us, [*] that

‘the idea which a few years ago would have been laughed at, that any man could acquire the power of shutting the whole continent against our trade, seems now not unlikely to be realized.’

And Mr. Cobbett assures us, that the soldier is abroad, and will not return home till he hath acquired a share of the good things of the world. On this point, those two champions appear to be at variance. The soldier will certainly not get possession of any of our good things, by shutting them out from the Continent; and if he [8] comes and takes them, we shall be in danger of losing our land as well as our commerce.

A calm and rational view of our circumstances, will probably soon convince us that neither the one bugbear of these authors, nor the other, ought in the highest degree to alarm us; and that it will be only by our own egregious misconduct, if we suffer any considerable disaster, from the efforts of our enemy either to invade us or to destroy our commerce. In regard to invasion, the experiment may be said to have been fairly tried, and to have failed; in the vast preparations made by Bonaparte, and the abandonment of the attempt to employ them. This danger then, especially as it seems to have little influence at present on the public feelings, we may pass without further notice. The experiment of excluding our commerce is now to be tried, and it may be regarded as a fortunate circumstance, that it can be tried so completely. When our enemy is thoroughly convinced, that neither his invading nor his excluding scheme, can be made the instrument of any serious injury to us; and when we ourselves are convinced that we have nothing either in peace or war to fear from him, the minds of both parties may decidedly incline to peace.

Let us only contemplate for one moment the vast extent of the habitable globe, and consider how small in comparison is that portion of coast over which the sway of Bonaparte extends; and we shall probably conclude with considerable confidence, that in the wide world channels will be found for all the commerce, to which this little [9] island can administer. Let us look first at the United States of America. To these, we have for years sent more goods of British manufacture than to the whole continent of Europe. The vast commerce of the West India Islands, next comes naturally in view. The immense extent of Portuguese and Spanish America, whose communication with manufacturing countries, may in a great measure be confined to ourselves, will, notwithstanding the disadvantages under which they labour, furnish a growing demand for the produce of our industry. Even the coasts of Africa, miserable as their condition is, might present to the careful explorer something better for the commodities which he may offer, than their wretched population. The Cape of Good Hope itself, improved by British wisdom and British capital, opens a field of boundless extent. The vast shores of the Indian ocean, both continental and insular, with their unrivalled productions, are all our own. Whatever the ingenuity of the Indian, the Malay, and the Chinese can produce, or their various and productive soils can yield, is ready to be exchanged for the commodities which we can supply to the wants of that immense population.

This superficial review can hardly fail to satisfy the man, who knows hut the outline of geography, that, while Britain is mistress of the sea, she might have scope for a boundless commerce, though the whole continent of Europe were swallowed up by an earthquake. But in regard to Europe itself, it is only to the superficial eye, [10] that the power of Bonaparte over our commerce can appear important. Not to mention the probability that the Baltic, the channel by which a great part of our commerce has for a number of years found its way into Europe, will not long be shut against us; the very notion of guarding the whole extent of European coast, from the mouth of the Elbe to the gulph of Venice, must appear ridiculous to all men of information and reflection. Let any man but consider the well known fact, that under the very eye of the most vigilant Custom House in the world, and where an actual army of Custom House officers is concentrated, contraband East India goods are regularly contracted for by the smugglers, to be delivered in any house in London, for 25 per cent. Even Hollands and brandy, which are not the most handy commodities, are currently landed in the Downs, in the presence of a British fleet. With a knowledge of these facts, can it be supposed, that any British goods which the Continent wants, will not find their way into it in spite of any regulations which Bonaparte can adopt? A line of soldiers regularly planted from one extremity of the coast to another, from the point of Jutland to the bottom of the Adriatic gulph, would not suffice to exclude our commerce.

An important fact is to be considered. The population of Great Britain take no interest in the success of the smugglers. The greater or at least the superior part condemn the traffic, and rather wish to obstruct it. The case is very different on the Continent. Even in France, the [11] great mass of the people wish for British commodities, and condemn the policy which excludes them. But in what may be called the conquered countries, in Holland for example, and Portugal, the interests and the ancient habits of the people of all ranks, give them the strongest propensity to elude, by every possible contrivance, the restrictive policy of Bonaparte. Where a whole people have the strongest interest in deceiving the government, in a case in which it can be so easily deceived as in the exclusion of British commerce from the Continent, we may confidently conclude that the public decrees will be very indifferently executed. If 25 per cent. can cover the expence of smuggling in the Downs, we may be certain that one half of that sum will be sufficient to cover the expence of smuggling British goods on the coasts of Europe. Even from this expence are to be deducted the Custom House duties which must have been paid in the course of regular entry; so that in many cases, British goods will reach the continental consumer, loaded with an expence of probably not more than 5 per cent, above what they would have cost in the way of regular trade. But allowing their price to be enhanced at a rate of 10 or 12 per cent, the deduction which this can occasion from the quantity which would otherwise be sold, cannot bear a very great proportion to the general amount of the extensive, various, and unrivalled traffic of Great Britain.

The fact is, the British commerce has much snore to fear from the injudicious regulations of [12] the British government, than from the decrees of Bonaparte. The great instrument of that species of traffic, which must now be carried on with the Continent, are neutral bottoms. It will not be very difficult, however, for our ministers to put it out of the power of the neutrals to serve us in this important capacity. The late orders of council are of a nature to give effect to the ‘decrees of Bonaparte, beyond any thing which the plenitude of his power could achieve. Instead of thwarting and restricting the intercourse of neutrals, Britain ought studiously to afford it every facility and accommodation. Wherever a neutral vessel obtains admittance into a continental port; means are afforded for introducing British goods. If the orders of the British council however serve to unveil the disguises, under which the neutrals might be enabled to cover our goods, this important resource may be in a great measure cut off, and the ingenuity of the merchants, so fertile in expedients for eluding the restrictions on trade, may be defeated.—We may perceive then, in the wide extent of the world, and its innumerable productions and wants, in our dominion of the seas, and in the impotence of all exclusive efforts, sufficient security for our commerce, if we exercise but common prudence, in spite of all external hostilities that can be waged against it.

[13]

CHAP. II.

On Land, as a Source of Wealth.↩

In the praises which the Economistes, together with Mr. Spence and Mr. Cobbett, bestow upon land as a source of wealth, absolutely considered, the intelligent reader will not hesitate to join, Of all species of labour, that which is bestowed upon the soil, is in general rewarded by the most abundant product. In the present circumstances of the greater part of Europe, the cultivation of the soil not only pays the wages of labour, and the profit of stock employed in it, the sole return of other species of industry, but over and above this affords a share of the produce payable as rent to the landlord. On this point, therefore, no controversy strictly exists; and when the patrons of the agricultural theory lament that the cabinets and legislatures of Europe, influenced by the ideas of the mercantile system, have so often thrown obstructions in the way of rural industry in favour of manufactures and trade, we acknowledge the justness of their accusations. One of the main objects which the immortal Smith proposed to himself, was to unfold the delusions of the mercantile system, by which the policy of almost all the governments of Europe was turned to the encouragement of trade rather [14] than of agriculture, and a greater share of the industry and capital of every nation than consisted with its interests, was thus forcibly diverted into the commercial channel. Even to this hour the sound inquirer has most frequently occasion for his efforts in exposing the errors into which both governments and individuals fall by the remaining influence of the same theory. The firm hold indeed which this doctrine yet maintains on the minds of men, forms the principal obstacle to the diffusion, among mankind, of juster principles of political economy and of government. When a system, therefore, is propagated, diametrically opposite to the Mercantile, we might quietly allow the two theories to combat one another; and trust that the exposure of errors, if not the establishment of truths, would be the consequence. Unfortunately, however, it is much more the propensity of mankind to run from one extreme into another, than to rest in the wise and salutary middle; and a bias to the errors of the agricultural system would be not a whit less pernicious than a bias to the system which it would supplant. Of this indeed we have experimental proof; as some of the worst regulations which the new legislators of France adopted, were entirely founded upon the system of the Economistes.

There is one consequence of the doctrine which Messrs. Spence and Cobbett have embraced, which they seem rather unfairly to have kept out of sight They address themselves with great industry to the self-interest of the landholders, and [15] study to win their support by representing the landed interest as deeply affected by the opinions which they wish to subvert. They abstain, however, from informing this class of their readers, that land, according to their doctrine, is the one and only proper subject of taxation. This the Economistes taught. It is a logical conclusion from their principles. If land be the one and only source of wealth, the absurdity is evident of seeking in any other quarter that portion of the national produce which is required for the necessities of the state; nor can one single argument be used against the exclusive taxation of land, which is not an argument, equally pointed, against the doctrine which the agricultural theorists espouse. It is shrewdly to be suspected that the landholders would deem themselves but little indebted to those gentlemen for the establishment of their system, if it was to be followed by this practical consequence. The fact is, that land in this country bears infinitely less than its due proportion of taxes, while commerce is loaded with them. At the beginning of the last century, and previous to that period, the land-tax equalled, or rather, exceeded, the whole amount of a!! the other taxes taken together. How insignificant a proportion does the land-tax now bear to the taxes on consumable commodities? The land-tax has remained without augmentation, while the permanent taxes have risen from little more than two millions to upwards of two and forty millions a year, and while the value of land has risen from [16] fourteen or fifteen years purchase to thirty years purchase and upwards. The landholders, therefore, have little foundation for complaining, though the policy of the country has frequently appeared to favour mercantile rather than agricultural industry. By their superior influence in the legislature, they have taken care to repay themselves, as far as their personal interests were concerned, by throwing the burthen of the taxes upon the growing produce of commerce, while the increasing value of land stood exempt. The interests, however, of the country at large, the interests of the middling and industrious classes, have thus suffered in two ways. They have suffered by sustaining an undue proportion of the taxes; and they have suffered by the diminution of the annual produce of the land and labour of the country. [*]

[17]

CHAP. III.

Of the Definition of the Terms Wealth and Prosperity.↩

Mr. Spence, with a view to introduce accuracy into his inquiry, presents us near the commencement of his pamphlet with a definition of the terms Wealth and Prosperity. This was indeed highly necessary, for while our ideas waver on this point, all our reasonings, respecting the wealth and prosperity of nations, must by consequence be uncertain and deceitful. It is of the utmost importance, therefore, in the examination of Mr. Spence's doctrines, to ascertain the precision or inaccuracy of his definition of wealth. The following passage contains not only the definition but its illustration:

[*] ‘In investigating the present subject, it will be necessary previously to inquire into the opinions which have been held relative to the real sources of wealth and prosperity to a nation, and we shall then be able to apply the results deduced from such an examination to our own case. And [18] in the first place, the meaning of the terms, wealth and prosperity, must he settled; for, if the reader were to take these words in their usual acceptation, if he were to conclude, that by the first is meant gold and silver merely, and by the latter extensive dominion, powerful armies, &c. he would be affixing to these terms meanings very different from those which are here meant to be annexed to them, and ideas, which, however common, are founded in error. Spain has plenty of gold and silver, yet she has no wealth; whilst Britain is wealthy with scarcely a guinea: and France, with her numerous conquests, her extended influence, and her vast armies, is probably not enjoying much prosperity; certainly not nearly so much as we enjoy, though we have far less influence, and much smaller armies than she has. Wealth, then, is defined to consist in abundance of capital, of cultivated and productive land, and of those things which man usually esteems valuable. Thus, a country where a large proportion of inhabitants have accumulated fortunes; where much of the soil is productively cultivated, and yields a considerable revenue to the land-owner, may be said to be wealthy; and on the contrary, a nation where few of the inhabitants are possessed of property, and where the land is badly cultivated, and yields but little revenue to the proprietor, may be truly said to be poor. Britain is an example of the first state, Spain and Italy of the last. A nation may be said to be in prosperity, which is progressively advancing in wealth, where the [19] checks to population are few, and where employment and subsistence are readily found for all classes of its inhabitants, It does not follow, that a prosperous nation must be wealthy; thus America, though enjoying great prosperity, has not accumulated wealth. Nor does it follow, that because a nation possesses wealth, it is therein a state of prosperity. All those symptoms of wealth which have been enumerated, may exist, and yet a nation may in prosperity be going retrograde, its wealth may be stationary, its population kept at a stand, and the difficulty of getting employment for those who seek it, may be becoming greater and greater every day.’

First, here, Mr. Spence warns us against supposing that wealth consists in gold and silver merely, and that prosperity consists in extensive dominion, powerful armies, and the like; and assuredly if any one entertains this idea of wealth and prosperity, he is in a woeful delusion. Having learned from Mr. Spence what wealth and prosperity are not, let us next learn what they are. ‘Wealth,’ he says, ‘is defined to consist in abundance of capital, of cultivated and productive land, and of those things which man usually esteems valuable.’ Here three things are enumerated as the constituents of wealth. The first is capital. Now it is an established and indispensible rule in definition, that the words themselves in which the definition is conceived should be of the most precise and determinate signification; because, otherwise, the definition is of no use. But here the term ‘capital’ stands as much in need of definition as the [20] term wealth, which it is brought to define. What is capital, or wherein does it consist? There are as many difficulties in these questions, as in the questions. What is wealth, and wherein does it consist? To define one vague and ambiguous word by another which is equally vague and ambiguous, is to pay us with mere words instead of ideas. The second constituent of wealth, according to Mr. Spence's definition, is cultivated and productive land. But would not Mr. Spence allow that uncultivated land, if it might be very easily cultivated and rendered productive, ought also to be accounted wealth? In a definition where every thing ought to be in the highest degree accurate, an exception even of this sort is important. Let us, however, attend particularly to what Mr. Spence states as the third constituent of wealth; ‘Those things which man usually esteems valuable.’ This is a sweeping clause. In the first place this third constituent includes both the other two, for undoubtedly capital and productive land are among the things which man esteems valuable. The third constituent, therefore, is not only the third, but the first, second, and third all in one. [*] It would have been much better without enumerating the first two, which are undoubtedly but parts of the last, to have said at once that wealth consisted in those things which man usually esteems valuable. Still, however, [21] the expression would have been so vague as to be entirely useless as a definition. Man usually esteems air and light as very valuable, but in what sense can they be regarded as national wealth? It is very evident from this explanation that Mr. Spence neither understands what is requisite to a definition, nor has formed to himself any distinct idea of the meaning of the term wealth.

Another particularity in this definition is worthy of a little attention. Mr. Spence says that wealth is defined to consist in abundance of capital, &c. When Mr. Spence, or any other political philosopher, inquires whether land, or manufactures, or commerce be the source of wealth, the question is not respecting quantity. We say that land is productive of wealth, without considering whether the quantity be one bushel or a million. But when Mr. Spence defines wealth as consisting in abundance of capital, land, and valuable things, he evidently confounds the philosophical meaning of the word with the vulgar, in which wealth signifies a great quantity of riches. So much for Mr. Spence's definition of wealth.

Let us next consider what he says in regard to prosperity. He does not indeed attempt to define prosperity; but he gives us a description of a nation which may be said to be in prosperity.

It is a nation which is progressively advancing in wealth, where the checks to population are few, and where employment and subsistence are readily found for all classes of its inhabitants.

It would be tedious here to enter into the same [22] minute analysis which we applied to the definition of wealth. We may barely remark, that of the three clauses of which the description consists, the last two are included in the first; as it is in the nation which is progressively advancing in wealth where the checks to population are fewest, and where employment and subsistence are most readily found for all classes of the inhabitants. This indeed is neither more nor less than the circumstance which is so well illustrated by Dr. Smith in the Wealth of Nations, e. i. c. 8.

Having seen how little useful are the definitions with which Mr. Spence has favoured us, it will be necessary for our subsequent inquiries to explain accurately in what sense the term wealth will there be used; and as this is the subject on which we are at present engaged, no other place can be more proper for the explanation. Wealth is relative to the term value; it is necessary therefore first to affix a meaning to the latter. The term value has in common acceptation two meanings. It signifies either value in use, or value in exchange. Thus water has great value in use but commonly has no value in exchange, that is to say, nothing can be obtained for it in purchase. On the other hand, a diamond or a ruby has little or no value in use, but great value in exchange. Now the term wealth will always be employed in the following pages as denoting objects which have a value in exchange, or at least notice will be given if we have ever occasion to use it in another sense.

[23]

CHAP. IV.

Of Manufactures.↩

It is at this point that our controversy with Messrs. Spence and Cobbett properly begins. They assert that manufactures are no source of wealth. [*] We say that they are. It is the reader's part to compare our reasons. Mr. Spence, who seems to supply the arguments of the party, says that manufactures are productive of no wealth, because the manufacturer in the preparation of [24] any commodity consumes a quantity of corn equal to the value which he has added to the raw materials of which the article is composed. It is to be observed, before we proceed farther, that this is the only reason which they adduce in favour of this fundamental part of their hypothesis. In this one assertion is contained the sum and substance of the evidence which they exhibit against manufactures. If this assertion is unequal to the conclusion which it is brought to support, the wonderful discoveries of the Economistes are on a tottering basis. I have called this fundamental proposition an assertion, because it is assumed entirely without proof, and what is more, I am afraid, in opposition to proof. When the manufacturer prepares a commodity, the prepared com-modify is worth more than the food which the workmen consumed in preparing it. Do you ask my reasons? Carry it, I say, to market; you will that it will fetch more; because it must not only repay the wages of the labour, but the profit of the stock which has been employed in its preparation. Set the goods on one side, and an equal quantity of raw materials and food with what has been consumed in their preparation on the other, and every body will give yon more for the goods. The country is therefore the richer by having the goods.

Let us hear what Mr. Spence has to say in objection to this reasoning. An examination of his plea will still more clearly exhibit to us the erroneousness of his position. The superiority of price which the manufactured commodity obtains [25] in the market, adds nothing he says to the wealth of the country; because whatever the manufacturer obtains above the value of the raw produce is taken from the landholder, the original owner of that produce.

‘An example,’ he adds, [*] ‘will demonstrate this: If a coach-maker were to employ so many men for half a year in the building of a coach, as that for their subsistence during that time, he had advanced fifty quarters of corn, and if we suppose he sold this coach to a land proprietor for sixty quarters of corn, it is evident, that the coach-maker would be ten quarters of corn richer than if he had sold it for fifty quarters, its original cost. But it is equally clear, that the land proprietor would be ten quarters of corn poorer, than if he had bought his coach at its prime cost. A transfer, then not a creation of wealth, has taken place, whatever one gains the other loses, and the national wealth is just the same.’

There is a great appearance of ingenuity and force in this reasoning; and on the greater part of mankind it is well calculated to impose. I am rather surprized, however, that a man of Mr. Spence's acuteness did not perceive that it is in reality a mere vulgar sophism. But when hypothesis has taken firm hold of a man, his acuteness is unluckily confined to one function.

Mr. Spence has here confounded two things which are remarkably different. He mistakes the sale of a coach for the manufacture of a coach. It is surely bad reasoning however to conclude [26] that because the sale of a coach is not productive of wealth, therefore the manufacture of a coach is not productive. The sale of the coach produces nothing; the manufacture of it however produces the coach. It is very true that when a landholder has sixty quarters of corn and the coach-manufacturer a coach, if the coach is transferred to the landowner and the corn to the coach-maker, the country is not the richer. But it is certainly not less true that if the coach-maker has in the month of October fifty quarters of corn, which in the month of March he has transformed into a coach worth sixty quarters, the country is the richer in consequence of the manufacture of the coach, to the amount of ten bushels of corn.

Important, however, as is the addition which it thus clearly appears is made to national wealth by means of manufacturing industry, we should still have a very imperfect idea of its wonderful powers, should we confine ourselves to this observation. In a state of agriculture but moderately improved, the labourers employed in it may be regarded as raising a produce not less than five times what they themselves can consume. Were there no manufacturers, the whole of this surplus produce would be absolutely useless. Where could it find a purchaser? It is the manufacturers who convert this surplus produce into the various articles useful or agreeable to man, and who thus add the whole value it obtains to four parts at least in five of the produce of the soil. [*]

[27]

There is but one supposition, as far as I am able to perceive, by which this argument can be eluded. If our antagonists suppose a state of society in which the population has become so great that it requires the utmost efforts of the whole employed upon the land to produce food for the society; in that case they may insist that the whole produce of the soil is employed and obtains a value without the aid of manufacturers. In this state of things, however, it is unfortunate that the argument of Mr. Spence will prove not manufactures only, but land to be unproductive. The cultivators of the soil, during the time in which they raise a certain produce, have here consumed a quantity of produce of an equal value. But this is the very reason which he adduces to prove that manufactures are not a source of wealth. Manufactures then never cease to produce wealth, except in one case, in which land itself ceases to produce it; so that when manufactures cease to produce wealth, every thing ceases to produce it; wealth cannot be produced at all.—So much for Mr. Spence's reasoning against manufactures.

The truth is, that to give even tolerable plausibility to the theory of the Economises we must [28] allow that nothing is useful or valuable to man but the bare necessaries of life, or rather the raw produce of the soil. If any thing else is valuable to him, whatever creates that value must add to his riches. The reasonings of the Economistes indeed proceed upon a most contracted and imperfect view of the operations and nature of man. How limited would be his enjoyments were he confined to the raw produce of the soil! How much are those enjoyments, how much is his wellbeing, promoted by the various productions of art which he has found the means of providing! The simple, bat at the same time the great and wonderful contrivance by which has been produced the profusion of accommodations with which the civilized life of man abounds, is the division of labour. Wherever a society can be supposed to consist of one class of labourers only, the cultivators of the soil, it must be poor and wretched. Even if each individual, or each family, may be supposed so far to vary their labour as to provide themselves with some species of coarse garment, or some rude hut to shelter them from the weather, the affairs of the society must still be miserable. Let us next consider the simplest division of labour which we can well imagine. Let us suppose that the society becomes divided into husbandmen, and into the manufacturers merely of their agricultural tools, of their garments and houses. How much more completely would the community almost immediately, or at least as soon as the manufacturers acquired any dexterity in their trades, be provided with the accommodations [29] which we have just enumerated? Their riches would be augmented. The labour of the same men would now yield a much larger produce. It is to the manufacturers however, it is to that division of labour which set them apart as a distinct class, that this superiority of produce, that this augmentation of riches, is entirely owing.

‘The greatest improvement,’ says Dr. Smith, ‘in the productive powers of labour, and the greater part of the skill, dexterity, and judgment, with which it is any where directed or applied, seem to have been the effects of the division of labor. ****. It is the great multiplication of the productions of all the different arts, in consequence of the division of labour, which occasions in a well governed society that universal opulence, which extends itself to the lowest ranks of the people,’

The effects indeed of the division of labour, are surprising and almost miraculous. But as the division of labour commenced with the first formation of a class of manufacturers, and as it is in manufactures that the division of labour has been carried to the greatest height, the business of agriculture being much less susceptible of this improvement, the whole or the greater part of the opulence, which is diffused in society by the division of labour, is to be ascribed to manufactures. The same is the case with machinery. How much the production of commodities is accelerated and increased by the invention and improvement of machines, requires no illustration. It is chiefly in manufactures, that this great advantage too has been [30] reaped. In agriculture, the use of machinery is much more limited.

Every view of the subject affords an argument against the intricate but flimsy reasonings of the Economistes. In the infancy of manufactures, when the distaff alone, and other simple and tedious instruments are known, let us suppose that a piece of cloth is prepared. Mr. Spence informs us, that nothing is added to the wealth of the society, by the preparation of this piece of cloth, because a quantity of corn equal to it in value, has during the preparation been consumed by the manufacturers. Let us suppose, however, that, suddenly, spinning and other machines are invented, by which the same labourers, are enabled to prepare six similar piece*, in the same time, and while they are consuming the same quantity of corn. If their manufacture in the former case replaced the corn which they consumed; in this case it replaces it six times. Will Mr. Spence deny that in such instances manufactures are productive of wealth? But how many more than six times have the productive powers of labour in the arts and manufactures been multiplied since the first division and distribution of occupations?

Without any further accumulation of arguments, I may take it I believe for granted, that the insufficiency of Mr. Spence's reasonings, to prove that manufactures are not a source of wealth, sufficiently appears. Let us now therefore proceed to another of his topics.

[31]

CHAP. V.

Commerce.↩

By commerce, in the language of Mr, Spence's pamphlet, is meant trade with foreign nations; and we have no objection, on the present occasion at least, to follow his example. Mr. Spence begins his investigation of this subject with the following paragraph:

‘As all commerce naturally divides itself into commerce of import and export, I shall in the first place, endeavour to prove, that no riches, no increase of national wealth, can in any case be derived from commerce of import; and, in the next place, that, although national wealth may, in some cases, be derived from commerce of export, yet, that Britain in consequence of particular circumstances, has not derived, nor does derive, from this branch of commerce, any portion of her national wealth; and, consequently, that her riches, her prosperity, and her power are intrinsic, derived from her own resources, independent of commerce, and might and will exist, even though her trade should be annihilated. These positions, untenable as at first glance they may seem, I do not fear being [*] able to establish to the satisfaction of those, who will dismiss from their mind the deep rooted [32] prejudices, with which, on this subject, they are warped; and who, no longer contented with examining the mere surface of things, shall determine to penetrate through every stratum of the mine which conceals the grand truths of political economy.’

Let us begin then with the most earnest endeavour, according to the recommendation of Mr. Spence, to purge our minds from ‘prejudices,’ attending solely to the reasons in favor of those positions, ‘which seem untenable at first glance.’ Let us summon up courage to follow his deep and adventurous example, and not contented with remaining ingloriously ‘at the surface,’ let us clap on the miner's jacket and trowsers, and descend in the bucket with Mr. Spence; that, as truth, according to the ancient philosopher, lay at the bottom of a well, we may find ‘the grand truths of political economy,’ at the bottom of a coal pit.

As trade with foreign nations consists of two distinct branches, commerce of import, and commerce of export, it will be convenient for us to consider each of these divisions separately. This circumstance will divide the present chapter into two articles.

Article First, Commerce of Import.

The reason which Mr. Spence adduces to prove to those, who dismiss their deep rooted prejudices, and penetrate into the mine of political economy, that commerce of import can never [33] produce wealth, he states in the following terms;

‘Every one must allow, that for whatever a nation purchases in a foreign market, it gives an adequate value, either in money or in other goods; so far then, certainly, it gains no profit nor addition to its wealth. It has changed one sort of wealth for another, but it has not increased the amount, it was before possessed of [*] .’

We have had already occasion to wonder at the oversights or mistakes, which so acute a man as Mr. Spence has committed, and we are here again brought into the same predicament. Might he not, without any great depth, without descending far below the ‘surface,’ have reflected that a commodity may be of one value in one place, and of another value in another place. A ton of hemp for example, which in Russia is worth £50, is in Great Britain worth £65. When we have exported therefore a quantity of British, goods, which in Britain is worth £50. and have imported in lieu of them a ton of hemp, which is worth £65, the riches of the country are by this exchange increased fifteen pounds [†] . We might illustrate this observation by a variety of examples. The meaning and force of it however are already sufficiently apparent. Whenever a cargo [34] of goods of any sort is exported, and a cargo of other goods, bought with the proceeds of the former, is imported, whatever the goods imported exceed in value the goods exported, beyond the expence of importation, is so much clear gain to the country; and to this amount are the riches of the country increased by the transaction.

Mr. Spence, however, has an argument to shew, that this reasoning is inconclusive. He allows, that the merchant, by whom the goods have been imported, makes a profit to the above amount. But this he says is no gain to the country. The additional sum, which the merchant obtains for the goods imported, is derived from the British consumer. Whatever the one gains therefore the other loses, and the country is nothing the richer. It is curious that this argument would prove the country to be not a farthing the richer, if all the goods imported were got by the merchants for nothing, or were even created by a miracle in their warehouses. In this case too, whatever the merchants obtained for their miraculous goods, would be drawn from the British consumer, and whatever the one gained the other would lose; consequently the country would be not a pin the richer for this extraordinary augmentation of goods. The reader will probably conclude, that an argument of this sort proves top much. We may recollect too, that this is neither more nor less than the argument which Mr. Spence produced, to prove, that manufactures were productive of no wealth. Whatever the manufactured commodity brought, beyond the [35] value of the raw produce consumed in the manufacture, was drawn, he said, from the purchaser, who lost whatever the seller gained. On this account he concluded, that the country was not the richer for manufactures. This argument we found to be so weak, that it implied the mistake of the sale of a commodity for its manufacture. In the present case too, the confusion and misapprehension are nearly the same. The transfer of the imported goods from one British subject to another, is mistaken for the exchange of a quantity of goods between Great Britain and a foreign country. The sale of the goods at home renders not the country richer, it is the purchase of them abroad, with a quantity of British goods of less value.

What we have already said appears to be perfectly sufficient to expose the fallacy of Mr. Spence's arguments to prove the inutility of commerce of import [*] . We may add, however, a few observations, to explain to the reader somewhat more distinctly in what manner commerce of import does contribute to national wealth. On the subject of political economy, it seems best to recur as often as possible to particular [36] instances; it being so very common for authors, who indulge, like Mr. Spence, in very general terms, to bewilder both themselves and their readers. We import iron for example from the Baltic, though in certain favourable situations, where coal and the ore are found in the same vicinity, we make it at home. How does it appear, that this importation is advantageous? For this reason, that in all other cases but those specified, we can buy it cheaper abroad, than we can make it at home. We send forth a hundred pounds worth of goods, and we purchase with those goods a quantity of iron, which is worth more than one hundred pounds. Whatever this superiority of value exceeds the charges of importation is gain to the country.

To render this observation still more applicable to Mr. Spence's principles, we may show how the instance resolves itself even into the rude produce of the soil. On making a ton of iron in Great Britain, let us suppose, that the labourers, &c. employed in providing the ore and the coals, and in smelting and preparing the metal, have consumed ten quarters of corn. Every ton of iron therefore prepared in Great Britain costs ten quarters of corn. Let us suppose, that in the preparation of a certain quantity of British manufactures, nine quarters of corn have been consumed; and let us suppose, that this quantity of goods will purchase in the Baltic a ton of iron, and afford, besides, the expence requisite for importing the iron into Britain. Is there not an evident saving of a quarter of corn, in the acquisition [37] of this ton of iron? Is not the country one quarter of corn the richer, by means of its importation? In the importation of a thousand such tons, is it not a thousand quarters richer?

It is curious, that Mr, Spence, whether by chance or design, I know not, has chosen all his examples of importation among invidious instances. He always illustrates his arguments by the importation of luxuries, of articles of immediate consumption, as tea for example, which being speedily used, seem not to add to the stock of the country, or to form part of its riches. This, however, if it is intended to have any effect, is only an argument to the ignorance of his readers; for the nature of the case is in no respect different. Why should Mr. Spence object to the commerce in articles of immediate consumption, when the produce of the land itself consists chiefly of articles of immediate consumption? Is the land not a source of wealth, because its chief produce is corn, which is generally all consumed within less than eighteen months from the time of its production?

To make indeed any distinction in this argument between articles of necessity, and articles of luxury, is absolutely nugatory. Whenever a country advances a considerable way beyond the infancy of society, it is a small portion of the members of the community who are employed in providing the mere necessaries of life. By far the greater proportion of them are employed in providing supply to other wants of man. Now in this case, as well as in the former, the sole question [38] is, whether a particular description of wants can be most cheaply supplied at home or abroad. If a certain number of manufacturers employed at home can, while they are consuming 100 quarters of corn, fabricate a quantity of goods, which goods will purchase abroad a portion of supply to some of the luxurious wants of the community which it would have required the consumption of 150 quarters at home to produce; in this case too the country is 50 quarters the richer for the importation. It has the same supply of luxuries for 50 quarters of corn less, than if that supply had been prepared at home.

The commerce of one country with another, is in fact merely an extension of that division of labour by which so many benefits are conferred upon the human race. As the same country is rendered the richer by the trade of one province with another; as its labour becomes thus infinitely more divided, and more productive than it could otherwise have been; and as the mutual supply to each other of all the accommodations which one province has and another wants, multiplies the accommodations of the whole, and the country becomes thus in a wonderful degree more opulent and happy; the same beautiful train of consequences is observable in the world at large, that great empire, of which the different kingdoms and tribes of men may be regarded as the provinces. In this magnificent empire too one province is favourable to the production of one species of accommodation and another province to another, by their mutual intercourse they arc enabled to [39] sort and to distribute their labour as most peculiarly suits the genius of each particular spot. The labour of the human race thus becomes much more productive, and every species of accommodation is afforded in much greater abundance. The same number of labourers whose efforts might have been expended in producing a very insignificant quantity of home-made luxuries, may thus in Great-Britain produce a quantity of articles for exportation, accommodated to the wants of other places, and peculiarly suited to the genius of Britain to furnish, which will purchase for her an accumulation of the luxuries of every quarter of the globe. There is not a greater proportion of her population employed in administering to her luxuries, in consequence of her commerce, there is probably a good deal less; but their labour is infinitely more productive; the portion of commodities which the people of Great-Britain acquire by means of the same labour, is vastly greater.

Article Second; Commerce of Export.

Mr. Spence's reasoning concerning commerce of export is rather more complicated than that concerning commerce of import.

‘It is plain,’ he says, [*] ‘that in some cases an increase of national wealth may be drawn from commerce of export. The value obtained in foreign markets for the manufactures which a nation exports, resolves itself into the value of the food which [40] has heen expended in manufacturing them, and the profit of the master manufacturer and the exporting merchant. These profits are undoubtedly national profit. Thus, when a lace-manufacturer has been so long employed in the manufacturing a pound of flax, into lace, that his subsistence during that period has cost £30; this sum is the real worth of the lace; and if it be sold at home, whether for £30 or £60, the nation is, as has been shewn, no richer for this manufacture. But if this lace be exported to another country, and there sold for £60, it is undeniable that the exporting nation has added £30 to its wealth by its sale, since the cost to it was only £30.’

Allowing, however, that this advantage, without any abatement, was drawn by Great-Britain from her export commerce, its utmost amount, he says, would still be trifling, and our exaggerated notions of the value of our trade, ridiculous.

‘Great-Britain,’ he informs us, [*] ‘in the most prosperous years of her commerce, has exported t6 the amount of about fifty millions sterling. If we estimate the profit of the master manufacturer, and the exporting merchant, at 20 per cent. on this, it will probably be not far from the truth; certainly it will be fully as much as in these times of competition is likely to be gained, Great-Britain then gains annually by her commerce of export ten millions,’ This sum, he tells us, is a mere trifle in the amount of our annual produce. ‘More than twice this sum,’ [41] he says, [*] ‘is paid for the interest of the national debt! More than four times this sum is paid to the government in taxes!’ [†]

This sum, however, insufficient as it is to justify our lofty conceptions of the value of our commerce, is in reality, he at last assures us, not gained by Great-Britain. The reason which he brings in proof of this assertion; is the point to the examination of which we now proceed.

Great-Britain, he says, and in proof of this he enters into a long dissertation, imports regularly to as great an amount as she exports, and for that reason she gains nothing by her export trade. But how then? What else would Mr. Spence have [42] us to do? Would he have us export our goods for nothing? And is that the plan which he would propose to make the country gain by her commerce? Ought we to carry our commodities to foreigners, and beg them only to accept of the articles; but above all things not to insist upon making us take any thing in payment; as this would be the certain way to prevent us from gaining by the trade?

For what on the other hand is it that Mr. Spence would recommend to us to get for our goods? If we receive not other goods, the only return we can receive seems to be money. Would Mr. Spence then tell us that we should get rich by receiving every year gold and silver for our fifty millions of exports? Not to insist upon the inherent absurdity of such a notion, let us only observe how inconsistent it would be with his own declared opinions? He warned us, in a passage already quoted, [*] against conceiving that wealth consists in gold and silver merely. He assured us that [†]

‘Spain has plenty of gold and silver, yet she has no wealth, whilst Britain is wealthy with scarcely a guinea.’ He informs us farther, [‡] that a nation which has abundance of gold and silver; is in fact not richer than if it had none. It has paid an equal value of some other wealth for them, and there is no good reason why it should be desirous of having this rather than [43] any other species of wealth; for the only superiority in value which the precious metals possess over other products of the labour of man, is their fitness for being the instruments of circulation and exchange. But in this point of view the necessity of having gold and silver no longer exists; experience has in modern times evinced that paper, or the promissory notes of men of undoubted property, form a circulating medium fully as useful and much less expensive.’

He here informs us expressly that gold and silver are in no respect more to be desired than any other imported commodity. But the importing of other commodities he assured us was the cause which prevented our commerce of export from being a source of wealth. We now see that by his own confession gold and silver are in the same predicament with other imported commodities. But, if in order to gain by our commerce of export, we must receive in return neither goods nor money, we see no alternative that is left, except, as we said before, giving our goods away for nothing.

It may serve to render the subject still more clear, if I add a few words in the farther explanation of money. The true idea of money is neither more nor less than that of a commodity which is bought and sold like other commodities. In dealings with foreign nations, that class of transactions which we are now considering, this will very easily appear. When British goods, sold abroad, are paid for in money, it is not the denomination of the foreign coin which the merchant [44] regards, it is the quantity of gold and silver which it contains. It is its value as bullion merely that he estimates in the exchange; and it is in the form of bullion, not of foreign coin, that the gold and silver, when it is in sold and silver that he receives his payment, is imported. The importation of gold and silver, therefore, differs in no respect from the importation of platinum, zinc, copper, or any other metal. A certain part of it being taken occasionally to be stamped as money, makes not an atom of difference between the cases. It appears, therefore, with additional evidence, that if the importation of other commodities in exchange for the British goods which we export, annihilates the advantage of the exportation; so likewise does the importation of gold and silver. Again, therefore, we ask in what possible way are we to derive wealth from our commerce of export, but by the generous disposal of our goods for nothing to the kind and friendly nations who will please to receive them.

If we trace this subject a little farther, we shall perceive how the importation of money would disorder the policy of Mr. Spence. It is very evident that the gold and silver which can be of any use in a nation, does not exceed a certain quantity. In Great-Britain, where it is almost banished from the medium of exchange, the annual supply which is wanted, cannot be very large. To render what we receive, above this trifling supply, of any utility, it must again travel abroad to purchase something for which we may have occasion. But in this case again it administers to the traffic [45] of importation; and thus, by the very act of its becoming useful, produces the effect which Mr. Spence says cuts off the advantage to be derived from commerce of export.

We have yet, however, to examine an important resource of Mr. Spence's theory. He makes a distinction between commodities, which are of a durable, and commodities winch are of a perishable nature. The commodities he says, which are of a durable nature, are much more valuable as articles of wealth, than articles which are of a perishable nature; and the country which produces or purchases the one, contributes much more to the augmentation of its wealth, than the country which acquires the latter. It sometimes happens to more accurate reasoners than Mr. Spence, that one part of their theory clashes with another. But we think it does not very often happen, that a man of Mr. Spence's powers of mind, (for it is rather in the want of practice in speculation, than in want of capacity for it, that his defect seems to lie) so obviously becomes the antagonist of his own doctrine. In the whole train of commodities, are any of a more perishable nature than all the most important productions of the land? Of many of the manufactures, on the other hand, the productions are of a very durable sort, as the manufactures for example of tooth-picks, and of glass beads for the ladies. According to this ingenious distinction, therefore, could we increase the manufacture of tooth-picks, and glass beads, by diminishing the production of [46] corn, we should contribute to the riches of the country.

The use which Mr. Spence makes of this distinction, is notable. The greater part of the articles of British importation, he says, are of a perishable nature; whereas her articles of exportation are of a durable nature; for this reason she ought to be considered as losing by her foreign trade.

‘We do,’ says he [*] , ‘gain annually a few millions by our export trade, and if we received these profits in the precious metals, or even in durable articles of wealth, we might be said to increase our riches by commerce; but we spend at least twice the amount of what we gain, in luxuries, which deserve the name of wealth but for an instant, which are here to day, and to morrow are annihilated. How then can our wealth be augmented by such a trade?’

We may here remark another instance, in which the ideas of Mr. Spence wage hostilities with one another. We shall hereafter find, that he recommends consumption and luxury, as favorable to the prosperity of the state. Yet here we perceive, that all his reasons against the utility of commerce, terminate in a quarrel with the importation of articles of luxury [†] .

[47]

Nothing was ever more unfortunate than this distinction of Mr. Spence. We have seen before, in the article on commerce of import, that no distinction in the question of wealth exists between the commerce in articles of luxury, and any other. Whatever arguments therefore are drawn from this distinction, are addressed to the ignorance of those, who, as Mr. Spence says, ‘skim the surface.’ The only distinction of importance, which can be made between one sort of commodities and another, is that between the commodities which are destined to serve for immediate and unproductive consumption, and the commodities which are destined to operate as the instruments or means of production. Of the first sort, are all articles of luxury; and even the necessaries of life of all those, who are not employed in productive labour. Of the latter sort, are the materials of our manufactures, as wool, iron, cotton, &c., whatever forms the machinery and tools of productive labour, and even the [48] food and clothes of the labourer. Of the commodities which administer to productive labour, it is evidently absurd to make any distinction between those which are durable, and those, which, to use a phrase of Mr. Spence, are, ‘evanescent;’ as the most evanescent of them all has performed its part, before it vanishes, and replaced itself with a profit. Thus, the drugs of the dyer, even the coals which are consumed in his, furnace, the corn which feeds his workmen, or the milk, one of the most perishable of all commodities, which they may use in their diet, have performed their part as completely, and to the amount of their value as usefully as the iron lever, with which he drives his press. On the other hand, when articles are destined for immediate and unproductive consumption, it seems a consideration of very trifling importance, whether they are articles which are likely to be all used in the course of one year, or in the course of several years. When a rouge for the ladies cheeks, which may be kept for any time, and hoarded up to any quantity, is imported, we surely cannot regard the interests of the country as much more consulted, than when the most evanescent luxury which Mr. Spence can conceive is introduced into it, When it is on a distinction without a difference, that Mr. Spence's argument against commerce ultimately depends, his doctrine must rest on a sandy foundation [*] .

[49]

Mr. Spence's opinions, however, on this subject are very wonderful.

‘Of two nations,’ he says [*] , ‘if one employed a part of its population in manufacturing articles of hardware, another in manufacturing wine, both destined for home consumption; though the nominal value of both products should be the same, and the hardware should be sold in one country for £10,000, and the wine in the other for the same sum, yet it is evident, that the wealth of the two countries would, in the course of a few years, be very different. If this system were continued for five years, in the one country, the manufacturers of hardware would have drawn from the consumers of this article, £50,000; and, at the same time, this manufacture being of so unperishable a nature, the purchasers of it would still have in existence the greater part of the wealth they had bought; whereas, in the other nation, though the wine manufacturers would have also drawn to themselves £50,000 from the consumers of wine, yet these last would have no vestige remaining of the luxury they had consumed. It is evident, therefore, that at the [50] end of five years, the wealth of the former nation would be much greater than that of the latter, though both had annually brought into existence wealth to an equal nominal amount.’

Now what is the idea which seems to be involved in this explanation? It is, that the nation which imports articles of a durable nature grows rich by hoarding them up. It is curious, that the very idea, and in fact the very example, which Dr. Smith brings forward as so absurd that it might serve to cover with ridicule the mercantile system, is actually adduced by Mr. Spence, in the simplicity of his heart, as a solid reason to prove the inutility of commerce. Dr. Smith thus remarks:

‘Consumable commodities, it is said, are soon destroyed; whereas gold and silver are of a more durable nature, and were it not for their continual exportation, might be accumulated for ages together, to the incredible augmentation of the real wealth of the country. Nothing, therefore, it is pretended, can be more disadvantageous to any country, than the trade which consists in the exchange of such lasting for such perishable commodities. We do not, however, reckon that trade disadvantageous which consists in the exchange of the hardware of England for the wines of France; and yet hardware is a very durable commodity, and were it not for this continual exportation, might too be accumulated for ages together, to the incredible augmentation of the pots and pans of the country. But it readily occurs that the number of such utensils is in every country necessarily limited [51] by the use which there is for them; that it would be absurd to have more pots and pans than were necessary for cooking the victuals usually consumed there; and that, if the quantity of victuals was to increase, the number of pots and pans would readily increase along with it, a part of the increased quantity of the victuals being employed in purchasing them, or in maintaining: an additional number of workmen, whose business it was to make them.’

In fact nothing can well be more weak than to consider the augmentation of national riches, by the accumulation of durable articles of luxury, as a consideration of moment. The value of the whole amount of them in any country is never considerable, and it is evident that whatever they cost is as completely withdrawn from maintaining productive industry, as that which is paid for the most perishable articles. [*] Mr. Spence has an extremely indistinct and wavering notion of national wealth. He seems on the present occasion to regard it as consisting in the actual accumulation of the money and goods which at any time exists in the nation. But this is a most imperfect and erroneous conception. The wealth of a country consists in her powers of annual production, not in the mere collection of articles which may [52] at any instant of time be found in existence, How inadequate an idea would he have of the wealth of Great Britain who should fix his ideas merely upon the goods in the warehouses of her merchants, and upon the accommodations in the houses of individuals; and should not rather direct his attention to the prodigious amount of goods and accommodations which is called into existence annually by the miraculous powers of our industry? The only part, it is evident, of the existing collection of commodities which in any degree contributes to augment the annual produce, the permanent riches of the country, is that part which administers to productive labour; the machines, tools, and raw materials which are employed in the different species of manufacturing and agricultural industry. All other articles whether durable or perishable are lost to the annual produce, and the smaller the quantity of either so much the better.

To trace however these ideas as far as Mr. Spence pleases; let us suppose that our merchants instead of importing perfumes, for example, for the nose, should import ornaments for the hair and other similar trinkets of the greatest durability. When or how can these be supposed to be of any utility or value? The use of them, it is evident, is as frivolous and as little conducive to any valuable end as that of the perfumes. It is only in the idea of their sale therefore that they can be considered as more valuable than the perfumes. They might still be sold for something after the perfumes are consumed. In the first [53] place, the sale of half worn trinkets or hardware would not, it is likely, be very productive. But observe the nature of the sale itself. What a nation sells, it sells to some other nation. Should it then sell its accumulation of trinkets and hardware, it must import something in lieu of them. This must be either perishable articles, or such durable articles as the hardware which was exported; for money, even according to Mr. Spence, forms no distinction. But this fresh cargo of durable articles is in the same predicament with the former; useless while it remains, and only capable of augmenting the riches of the country when it is resold. But this course it is evident may be repeated to infinity, and still the augmentation of wealth be as little attained as before. It is seldom that a false argument in political economy admits of so complete a reduction to absurdity as this.

We have thus with some minuteness examined the validity of what Mr. Spence brings, in the shape of argument, to prove that the export commerce of Great Britain is productive of no wealth. [*] A very short and conclusive argument however was sufficient for the refutation of this boasted [54] doctrine. The imports of Great Britain are equal, he says, in amount to her exports, and they are chiefly of a perishable nature. What Great Britain therefore might gain by her exports she loses by her imports. But we have already proved, in the preceding article, that commerce of import is itself a source of gain, and that, whether the articles imported are of a perishable or a durable nature. Whatever therefore is gained by our commerce of export is so far from being diminished by our commerce of import, that this last affords a gain equal in amount to that of the former. The profits of commerce are doubled by the operation of import. [*]

There is another view of this subject exhibited by Mr. Spence, which it may yet be of some importance to consider. Though the grand axiom of the Economistes; that the only source of wealth is land, is undoubtedly, he says, founded in truth, yet an application which they make of this axiom to the present affairs of Europe is erroneous. Though it is [†]

‘the natural order of prosperity [55] in a state that agriculture produces manufactures, not manufactures agriculture; yet the case seems very different with Europe, and an attention to facts will prove, that in Britain agriculture has thriven only in consequence of the influence of manufactures; and that the increase of this influence is requisite to its farther extension.’

It is needless to state the proof which he adduces of these positions; for it is neither more nor less than a repetition, in Mr. Spence's own manner, of the view which Dr. Smith exhibits [*] of the progress of industry in the feudal governments of modern Europe; where the slow and imperceptible insinuation of commerce burst asunder the bands of feudal tyranny, and instead of the sloth and poverty of servitude introduced the industry and opulence of liberty. It is enough for us at present to advert attentively to the positions which Mr. Spence here so emphatically announces, that such have been, and such are, the actual circumstances of Europe, that agriculture neither could have thriven, nor can yet thrive, but by means of manufactures. On this single admission, me-thinks, one might conclude that it was rather a rash doctrine to promulgate that commerce is of no utility to Great Britain, and that she might contemplate the loss of it with little emotion.

But having seen that manufactures, by Mr. Spence's own admission, are absolutely necessary to the prosperity of Europe in her present circumstances, [56] particularly in the present arrangement of her landed property; let us next sec what is that state of things to which alone he admits that his doctrine respecting land and commerce is applicable. Having shewn that the conclusion which the Economistes drew, and drew very logically, from their principles, that till the whole land of every country be cultivated in the most complete manner, manufactures should receive little encouragement, will not apply to the circumstances of modern Europe, he next proceeds to describe that state of affairs to which the principles and conclusions of that sect do apply. Observe then what is that arrangement of the circumstances of Europe, what the changes from their present situation, which are requisite to adopt them for the practical operation of the doctrines of the Economistes.

‘If the question were,’ says Mr. Spence, [*] ‘on what system may the greatest prosperity be enjoyed by the bulk of society, there can be no doubt that the system recommended by the Economistes, which directs the attention of every member of society to be turned to agriculture, would be most effectual to this end. But such a system could be efficaciously established in Europe in no other way than by the overthrow of all the present laws of property, and by a revolution which would be as disasterous in its ultimate consequences as it would be unjust and impracticable in its institution. This system could be acted upon only by [57] the passing an Agrarian law; by the division of the whole soil of a country in equal portions amongst its inhabitants.’

—Let us here in treat Mr. Spence to pause for a moment, and to reflect upon the practical lessons which he is so eager to teach us. The present course of industry by manufactures and commerce he admits is adapted to the present circumstances of Europe, and that all the prosperity which she exhibits is owing to it; the application of the doctrine that all prosperity is owing to agriculture would require, he says,

‘the division of the whole soil of the country in equal portions amongst its inhabitants, a revolution which would be as disasterous in its ultimate consequences, as it would be unjust and impracticable in its institution;’

yet on the strength of this system he would have us believe that commerce is of no utility; he would have us conduct our affairs on a plan which is not applicable to the present situation of the world, and abandon the course by which we have attained our actual prosperity. [*]