David Hume, Essays, Moral and Political (1741)

|

|

| David Hume (1711-1776) |

[Created: 23 March, 2023]

[Updated: April 30, 2023 ] |

The Guillaumin Collection

|

This title is part of “The Guillaumin Collection” within “The Digital Library of Liberty and Power”. It has been more richly coded and has some features which other titles in the library do not have, such as the original page numbers, formatting which makes it look as much like the original text as possible, and a citation tool which makes it possible for scholars to link to an individual paragraph which is of interest to them. These titles are also available in a variety of eBook formats for reading on portable devices. |

Source

, Essays, Moral and Political (Edinburgh: R. FLEMING and A. ALISON, 1741).http://davidmhart.com/liberty/EnglishClassicalLiberals/Hume/1741-EssaysMoralPolitical/index.html

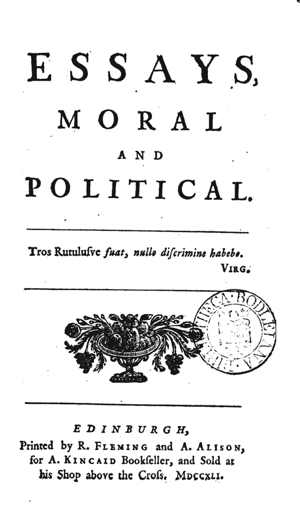

David Hume, Essays, Moral and Political (Edinburgh: Printed by R. FLEMING and A. ALISON, for A. KINCAID Bookseller, and Sold at his Shop above the Cross. MDCCXLI (1741)).

This title is also available in a facsimile PDF of the original and various eBook formats - HTML, PDF, and ePub.

This book is part of a collection of works by David Hume (1711-1776).

[Page]

CONTENTS.

- I. Of the Delicacy of Taste and Passion, 1

- II. Of the Liberty of the Press, 9

- III. Of Impudence and Modesty, 19

- IV. That Politicks may be reduc'd to a Science, 27

- V. Of the first Principles of Government, 49

- VI. Of Love and Marriage, 59

- VII. Of the Study of History, 69

- VIII. Of the Independency of Parliament, 79

- IX. Whether the British Government inclines more to absolute Monarchy, or to a Republick, 93

- X. Of Parties in general, 105

- XI. Of the Parties of Great Britain, 119

- XII. Of Superstition and Enthusiasm, 141

- XIII. Of Avarice, 153

- XIV. Of the Dignity of Human Nature, 161

- XV. Of Liberty and Despotism, 173

- Endnotes

[iii]

Advertisement.↩

MOST of these ESSAYS were wrote with a View of being publish'd as WEEKLY-PAPERS, and were intended to comprehend the Designs both of the SPECTATORS and CRAFTSMEN. But having dropt that Undertaking, partly from LAZINESS, partly from WANT of LEISURE, and being willing to make Trial of my Talents for Writing, before I ventur'd upon any more serious Compositions, I was induced to commit these Trifles to the [iv] Judgment of the Public. Like most new Authors, I must confess, I feel some Anxiety concerning the Success of my Work: But one Thing makes me more secure; That the READER may condemn my Abilities, but must approve of my Moderation and Impartiality in my Method of handling POLITICAL SUBJECTS: And as long as my Moral Character is in Safety, I can, with less Anxiety, abandon my Learning and Capacity to the most severe Censure and Examination. Public Spirit, methinks, shou'd engage us to love the Public, and to bear an equal Affection to all our Country-Men; not to hate one Half of them, under Pretext of loving the Whole. [v] This PARTY-RAGE I have endeavour'd to repress, as far as possible; and I hope this Design will be acceptable to the moderate of both Parties; at the same Time, that, perhaps, it may displease the Bigots of both.

THE READER must not look for any Connexion among these ESSAYS, but must consider each of them as a Work apart. This is an Indulgence that is given to all ESSAY-WRITERS, and is an equal Ease both to WRITER and READER, by freeing them from any tiresome Stretch of Attention or Application.

[1]

ESSAY I.

Of the DELICACY of TASTE and PASSION.↩

THERE is a certain Delicacy of Passion, to which some People are subject, that makes them extremely sensible to all the Accidents of Life, and gives them a lively Joy upon every prosperous Event, as well as a piercing Grief, when they meet with Crosses and Adversity. Favours and Good-offices easily engage their Friendship; while the smallest Injury provokes their Resentment. Any Honour or Mark of Distinction elevates them above Measure; but they are as sensibly touch'd with Contempt. People of this Character have, no doubt, much more lively Enjoyments, as well as more pungent Sorrows, than Men of [2] more cool and sedate Tempers: But, I believe, when every Thing is balanc'd, there is no one, that wou'd not rather chuse to be of the latter Character, were he entirely Master of his own Disposition. Good or ill Fortune is very little at our own Disposal: And when a Person, that has this Sensibility of Temper, meets with any Misfortune, his Sorrow or Resentment takes intire Possession of him, and deprives him of all Relish in the common Occurrences of Life, the right Enjoyment of which forms the greatest Part of our Happiness. Great Pleasures are much less frequent than great Pains; so that a sensible Temper must meet with fewer Trials in the former Way than in the latter. Not to mention, that Men of such lively passions are apt to be transported beyond all Bounds of Prudence and Discretion, and take false Steps in the Conduct of Life, which are often irretrievable.

THERE is a Delicacy of Taste observable in some Men, which very much resembles this Delicacy of Passion, and produces the same Sensibility to Beauty and Deformity of every Kind, as that does to Prosperity and Adversity, Obligations and Injuries. When you [3] present a Poem or a Picture to a Man possest of this Talent, the Delicacy of his Feeling or Sentiments makes him be touched very sensibly by every Part of it; nor are the masterly Strokes perceived with a more exquisite Relish and Satisfaction, than the Negligences or Absurdities with Disgust and Uneasiness. A polite and judicious Conversation affords him the highest Entertainment. Rudeness or Impertinence is as great a Punishment to him. In short, Delicacy of Taste has the same Effect as Delicacy of Passion: It enlarges the Sphere both of our Happiness and Misery, and makes us sensible of Pains, as well as Pleasures, that escape the rest of Mankind.

I BELIEVE, however, there is no one, who will not agree with me, that notwithstanding this Resemblance, a Delicacy of Taste is as much to be desir'd and cultivated as a Delicacy of Passion is to be lamented, and to be remedied, if possible. The good or ill Accidents of Life are very little at our Disposal: But we are pretty much Masters what Books we shall read, what Diversions we shall partake of, and what Company we shall keep. The ancient Philosophers endeavour'd to render [4] Happiness intirely independent of every Thing external. That is impossible to be attain'd: But every wise Man will endeavour to place his Happiness on such Objects as depend most upon himself: And that is not to be attain'd so much by any other Means as by this Delicacy of Sentiment. When a Man is possest of that Talent, he is more happy by what pleases his Taste than by what gratifies his Appetites, and receives more Enjoyment from a Poem or a Piece of Reasoning than the most expensive Luxury can afford.

HOW far the Delicacy of Taste and that of Passion are connected together in the original Frame of the Mind, it is hard to determine. To me there appears to be a very considerable Connexion betwixt them. For we may observe, that Women, who have more delicate Passions than Men, have also a more delicate Taste of the Ornaments of Life, of Dress, Equipage, and the ordinary Decencies of Behaviour. Any Excellency in these hits their Taste much sooner than Ours; and when you please their Taste, you soon engage their Affections.

[5]

BUT whatever Connexion there may be originally betwixt these Dispositions, I am persuaded, that nothing is so proper to cure us of this Delicacy of Passion as the cultivating of that higher and more refined Taste, which enables us to judge of the Characters of Men, of Compositions of Genius, and of the Productions of the nobler Arts. A greater or less Relish of those obvious Beauties, that strike the Senses, depends intirely upon the greater or less Sensibility of the Temper: But with regard to the Liberal Arts, a fine Taste is really nothing but strong Sense, or at least depends so much upon it, that they are inseparable. To judge aright of a Composition of Genius, there are so many Views to be taken in, so many Circumstances to be compared, and such a Knowledge of human Nature requisite, that no Man, who is not possest of the soundest Judgment, will ever make a tolerable Critic in such Performances. And this is a new Reason for cultivating a Relish in the Liberal Arts. Our Judgment will strengthen by this Exercise: We shall form truer Notions of Life: Many Things, which rejoice or afflict others, will appear to us too frivolous to engage our Attention: And we [6] shall lose by Degrees that Sensibility and Delicacy of Passion, which is so incommodious.

BUT perhaps I have gone too far in saying, that a cultivated Taste for the Liberal Arts extinguishes the Passions, and renders us indifferent to those Objects, which are so fondly pursued by the rest of Mankind. When I reflect a little more, I find, that it rather improves our Sensibility for all the tender and agreeable Passions; at the same Time, that it renders the Mind incapable of the rougher and more boist'rous Emotions.

Ingenuas didicisse fideliter artes,

Emollit mores, nec sinit esse feros.

FOR this, I think there may be assigned two very natural Reasons. In the first Place, nothing is so improving to the Temper as the Study of the Beauties, either of Poetry, Eloquence, Musick, or Painting. They give a certain Elegance of Sentiment, which the rest of Mankind are intire Strangers to. The Emotions they excite are soft and tender. They draw the Mind off from the Hurry of Business and Interest; cherish Reflection; dispose to Tranquility; and produce an agreeable Melancholy, [7] which, of all Dispositions of the Mind, is the best suited to Love and Friendship.

IN the second Place, a Delicacy of Taste is favourable to Love and Friendship, by consining our Choice to few People, and making us indifferent to the Company and Conversation of the greatest Part of Men. You will very seldom find, that mere Men of the World, whatever strong Sense they may be endowed with, are very nice in distinguishing of Characters, or in marking those insensible Differences and Gradations, which make one Man preferable to another. Any one, that has competent Sense, is sufficient for their Entertainment. They talk to him of their Pleasures and Affairs, with the same Frankness as they would to any other: And finding many, that are fit to supply his Place, they never feel any Vacancy or Want in his Absence. But to make use of the Allusion of a famous [1] French Author: The Judgment may be compared to a Clock or Watch, where the most ordinary Machine is sufficient to tell the Hours; but [8] the most elaborate and artificial only can point out the Minutes and Seconds, and distinguish the smallest Differences of Time. One that has well digested his Knowledge both of Books and Men, has little Enjoyment but in the Company of a few select Companions. He feels too sensibly, how much all the rest of Mankind falls short of the Notions he has entertained. And his Affections being thus confined in a narrow Circle, no Wonder he carries them further, than if they were more general and undistinguished. The Gaiety and Frolick of a Bottle-Companion improves with him into a solid Friendship: And the Ardours of a youthful Appetite become an elegant Passion.

[9]

ESSAY II.

Of the LIBERTY of the PRESS.↩

THERE is nothing more apt to surprise a Foreigner, than the extreme Liberty we enjoy in this Country, of communicating whatever we please to the Publick, and of openly censuring every Measure which is enter'd into by the King or his Ministers. If the Administration resolve upon War, 'tis affirm'd, that either wilfully or ignorantly they mistake the Interest of the Nation, and that Peace, in the present Situation of Affairs, is infinitely preferable. If the Passion of the Ministers be for Peace, our Political Writers breathe nothing but War and Devastation, and represent the pacifick Conduct of the Government as mean and pusillanimous. As this Liberty is not indulg'd in any other Government, either Republican [10] or Monarchical; in Holland and Venice, no more than in France or Spain; it may very naturally give Occasion to these two Questions, How it happens that Great Britain enjoys such a peculiar Privilege? and, Whether the unlimited Exercise of this Liberty be advantageous or prejudicial to the Publick?

AS to the first Question, Why the Laws indulge us in such an extraordinary Liberty? I believe the Reason may be deriv'd from our mixt Form of Government, which is neither wholly Monarchical, nor wholly Republican. 'Twill be found, if I mistake not, to be a true Observation in Politicks, That the two Extremes in Government, of Liberty and Slavery, approach nearest to each other; and, that as you depart from the Extremes, and mix a little of Monarchy with Liberty, the Government becomes always the more free; and, on the other Hand, when you mix a little of Liberty with Monarchy, the Yoke becomes always the more grievous and intolerable. In a Government, such as that of France, which is entirely absolute, and where Laws, Custom, and Religion, all concur to make the People fully satisfi'd with their Condition, the [11] Monarch cannot entertain the least Jealousy against his Subjects, and therefore is apt to indulge them in great Liberties both of Speech and Action. In a Government altogether Republican, such as Holland, where there is no Magistrate so eminent as to give Jealousy to the State, there is also no Danger in intrusting the Magistrates with very large discretionary Powers; and tho' many Advantages result from such Powers, in the Preservation of Peace and Order; yet they lay a considerable Restraint on Mens Actions, and make every private Subject pay a great Respect to the Government. Thus it is evident, that the two Extremes, of absolute Monarchy and of a Republic, approach very near to each other in the most material Circumstances. In the first, the Magistrate has no Jealousy of the People: In the second, the People have no Jealousy of the Magistrate: Which want of Jealousy begets a mutual Confidence and Trust in both Cases, and produces a Species of Liberty in Monarchies, and of arbitrary Power in Republics.

To justify the other Part of the foregoing Proposition, that in every Government the [12] Means are most wide of each other, and that the Mixtures of Monarchy and Liberty render the Yoke either more easy or more grievous. I must take Notice of a Remark of Tacitus with regard to the Romans under their Emperors, that they neither could bear total Slavery nor total Liberty, Nec totam servitutem nec totam libertatem pati possunt. This Remark a famous Poet has translated and applied to the English in his admirable Description of Queen Elizabeth's Policy and happy Government.

Et fit aimer son joug a l'Anglois indompté,

Qui ne peut ni servir, ni vivre en libertéHENRIADE, Liv. 1.

ACCORDING to these Remarks, therefore, we are to consider the Roman Government as a Mixture of Despotism and Liberty, where the Despotism prevailed; and the English Government as a Mixture of the same Kind, but where the Liberty predominates. The Consequences are exactly conformable to the foregoing Observation; and such as may be expected from those mixed Forms of Government, which beget a mutual Watchfulness and Jealousy. The Roman Emperors were, many [13] of them, the most frightful Tyrants that ever disgraced Humanity; and 'tis evident their Cruelty was chiefly excited by their Jealousy, and by their observing, that all the great Men of Rome bore with Impatience the Dominion of a Family, which, but a little before, was nowise superior to their own. On the other Hand, as the Republican Part of the Government prevails in England, tho' with a great Mixture of Monarchy, 'tis obliged, for its own Preservation, to maintain a watchful Jealousy over the Magistrates, to remove all discretionary Powers, and to secure every one's Life and Fortune by general and inflexible Laws. No Action must be deemed a Crime but what the Law has plainly determined to be such: No Crime must be imputed to a Man but from a legal Proof before his Judges: And even these Judges must be his Fellowsubjects, who are obliged by their own Interest to have a watchful Eye over the Encroachments and Violence of the Ministers. From these Causes it proceeds, that there is as much Liberty, and even, perhaps, Licence in Britain, as there was formerly Slavery and Tyranny in Rome.

[14]

THESE Principles account for the great Liberty of the Press in these Kingdoms, beyond what is indulg'd in any other Government. 'Tis sufficiently known, that despotic Power wou'd soon steal in upon us, were we not extreme watchful to prevent its Progress, and were there not an easy Method of conveying the Alarum from one End of the Kingdom to the other. The Spirit of the People must frequently be rouz'd to curb the Ambition of the Court; and the Dread of rouzing this Spirit must be employ'd to prevent that Ambition. Nothing is so effectual to this Purpose as the Liberty of the Press, by which all the Learning, Wit, and Genius of the Nation may be employ'd on the Side of Liberty, and every one be animated to its Defence. As long, therefore, as the Republican Part of our Government can maintain itself against the Monarchical, it must be extreme jealous of the Liberty of the Press, as of the utmost Importance to its Preservation.

SINCE therefore the Liberty of the Press is so essential to the Support of our mixt Government; this sufficiently decides the second Question, Whether this Liberty be advantageous [15] or prejudicial; there being nothing of greater Importance in every State than the Preservation of the ancient Government, especially if it be a free one. But I wou'd fain go a Step farther, and assert, that such a Liberty is attended with so few Inconveniencies, that it may be claim'd as the common Right of Mankind, and ought to be indulg'd them almost in every Government; except the Ecclesiastical, to which indeed it wou'd be fatal. We need not dread from this Liberty any such ill Consequences as follow'd from the Harangues of the popular Demagogues of Athens and Tribunes of Rome. A Man reads a Book or Pamphlet alone and coolly. There is none prefent from whom he can catch the Passion by Contagion. He is not hurry'd away by the Force and Energy of Action. And shou'd he be wrought up to never so seditious a Humour, there is no violent Resolution presented to him, by which he can immediately vent his Passion. The Liberty of the Press, therefore, however abus'd, can scarce ever excite popular Tumults or Rebellion. And as to those Murmurs or secret Discontents it may occasion, 'tis better they shou'd get Vent in Words, that they may come to the Knowledge [16] of the Magistrate before it be too late, in order to his providing a Remedy against them. Mankind, 'tis true, have always a greater Propension to believe what is said to the Disadvantage of their Governors than the contrary; but this Inclination is inseparable from them, whether they have Liberty or not. A Whisper may fly as quick, and be as pernicious as a Pamphlet. Nay it will be more pernicious, where Men are not accustom'd to think freely, or distinguish betwixt Truth and Falshood.

IT has also been found, as the Experience of Mankind increases, that the People are no such dangerous Monster as they have been represented, and that 'tis in every Respect better to guide them, like rational Creatures, than to lead or drive them, like brute Beasts. Before the united Provinces set the Example, Toleration was deem'd incompatible with good Government, and 'twas thought impossible, that a Number of religious Sects cou'd live together in Harmony and Peace, and have all of them an equal Affection to their common Country, and to each other. England has set a like Example of civil Liberty; and tho' this [17] Liberty seems to occasion some mall Ferment at present, it has not as yet produced any pernicious Effects, and it is to be hoped, that Men, being every Day more accustomed to the free Discussion of public Affairs, will improve in their Judgment of them, and be with greater Difficulty seduced by every idle Rumor and popular Clamour

'TIS a very comfortable Reflection to the Lovers of Liberty, that this peculiar Privilege of Britain is of a Kind that cannot easily be wrested from us, and must last as long as our Government remains, in any Degree, free and independent. 'Tis seldom, that Liberty of any Kind is lost all at once. Slavery has so frightful an Aspect to Men accustom'd to Freedom, that it must steal in upon them by Degrees, and must disguise itself in a thousand Shapes, in ordet to be received. But if the Liberty of the Press ever be lost, it must be lost at once. The general Laws against Sedition and Libelling are at present as strong as they possibly can be made. Nothing can impose a farther Restraint, but either the clapping an IMPRIMATUR upon the Press, or the giving very large discretionary Powers to the [18] Court to punish whatever displeases them. But these Concessions would be such a bare-fac'd Violation of Liberty, that they will probably be the last Efforts of a despotic Government. We may conclude, that the Liberty of Britain is gone for ever, when these Attempts shall succeed.

[19]

ESSAY III.

Of IMPUDENCE and MODESTY.↩

I HAVE always been of Opinion, that the Complaints against Providence have been ill-grounded, and that the good or bad Qualities of Men are the Causes of their good or bad Fortune, more than what is generally imagined. There are, no doubt, Instances to the contrary, and pretty numerous ones too; but few, in Comparison of the Instances we have of a right Distribution of Prosperity and Adversity: Nor indeed could it be otherwise from the common Course of human Affairs. To be endowed with a benevolent Disposition, and to love others will almost infallibly procure Love and Esteem; which is the chief Circumstance in Life, and facilitates every Enterprize and Undertaking; besides the Satisfaction, which immediately [20] results from it. The Case is much the same with the other Virtues. Prosperity is naturally, tho' not necessarily attached to Virtue and Merit; as Adversity is to Vice and Folly.

I MUST, however, confess, that this Rule admits of an Exception with regard to one moral Quality; and that Modesty has a natural Tendency to conceal a Man's Talents, as Impudence displays them to the utmost, and has been the only Cause why many have risen in the World, under all the Disadvantages of low Birth and little Merit. Such Indolence and Incapacity is there in the Generality of Mankind, that they are apt to receive a Man for whatever he has a Mind to put himself off for; and admits his over-bearing Airs as Proofs of that Merit, which he assumes to himself. A decent Assurance seems to be the natural Attendant of Virtue; and few Men can distinguish Impudence from it: As, on the other Hand, Diffidence, being the natural Result of Vice and Folly, has drawn Disgrace upon Modesty, which in outward Appearance so nearly resembles it.

[21]

I WAS lately lamenting to a Friend of mine, who loves a Conceit, that popular Applause should be bestowed with so little Judgment, and that so many empty forward Coxcombs should rise up to a Figure in the World: Upon which he said there was nothing surprising in the Case. Popular Fame, says he, is nothing but Breath or Air; and Air very naturally presses into a Vacuum.

As Impudence, tho' really a Vice, has the same Effects upon a Man's Fortune, as if it were a Virtue; so it is remarkable that it is almost as difficult to be attain'd, and is, in that respect, distinguish'd from all the other Vices, which are acquired with little Pains, and continually encrease upon Indulgence: Many a Man, being sensible that Modesty is extremely prejudicial to him in the making his Fortune, has resolved to be impudent and to put a bold Face upon the Matter: But 'tis observable, that such People have seldom succeeded in the Attempt, but have been obliged to relapse into their primitive Modesty. Nothing carries a Man thro' the World like a true genuine natural Impudence. Its Counterfeit is good for nothing, nor can ever support itself. In any [22] other Attempt, whatever Faults a Man commits and is sensible of, he is so much the nearer his End. But when he endeavours at Impudence, if he ever fail'd in the Attempt, the Remembrance of it will make him blush, and will infallibly disconcert him: After which every Blush is a Cause for new Blushes, 'till he be found out to be an arrant Cheat, and a vain Pretender to Impudence.

IF any thing can give a modest Man more Assurance, it must be some Advantages of Fortune, which Chance procures to him. Riches naturally gain a Man a favourable Reception in the World, and give Merit a double Lustre, when a Person is endowed with it; and supply its Place, in a great Measure, when it is absent. 'Tis wonderful to observe what Airs of Superiority Fools and Knaves, with large Possessions, give themselves above Men of the greatest Merit in Poverty. Nor do the Men of Merit make any strong Opposition to these Usurpations; or rather seem to favour them by the Modesty of their Behaviour. Their Good Sense and Experience make them diffident of their Judgment, and cause them to examine every thing with the greatest Accuracy: As [23] on the other Hand, the Delicacy of their Sentiments makes them timorous lest they commit Faults, and lose in the Practice of the World that Integrity of Virtue, of which they are so jealous. To make Wisdom agree with Confidence is as difficult as to reconcile Vice to Modesty.

THESE are the Reflections that have occur'd to me upon this Subject of Impudence and Modesty; and I hope the Reader will not be displeased to see them wrought into the following Allegory.

JUPITER, in the Beginning, joined VIRTUE, WISDOM and CONFIDENCE together; and VICE, FOLLY, and DIFFIDENCE: And in that Society set them upon the Earth. But though he thought he had matched them with great judgment, and said that Confidence was the natural Companion of Virtue, and that Vice deserved to be attended with Diffidence, they had not gone far before Dissension arose among them. Wisdom, who was the Guide of the one Company, was always accustomed, before she ventured upon any Road, however beaten, to examine it carefully; [24] to enquire whither it led; what Dangers, Difficulties and Hindrances might possibly or probably occur in it. In these Deliberations she usually consum'd some Time; which Delay was very displeasing to Confidence, who was always inclin'd to hurry on, without much Forethought or Deliberation, in the first Road he met. Wisdom and Virtue were inseparable: But Confidence one Day, following his impetuous Nature, advanc'd a considerable Way before his Guides and Companions; and not feeling any Want of their Company, he never enquir'd after them, nor ever met with them more. In like Manner, the other Society, tho' join'd by Jupiter, disagreed and separated. As Folly saw very little Way before her, she had nothing to determine concerning the Goodness of Roads, nor cou'd give the Preference to one above another; and this Want of Resolution was encreas'd by Diffidence, who with her Doubts and Scruples always retarded the Journey. This was a great Annoyance to Vice, who lov'd not to hear of Difficulties and Delays, and was never satisfy'd without his full Career, in whatever his Inclinations led him to. Folly, he knew, tho' she hearken'd to Diffidence, wou'd be easily manag'd when alone; [25] and therefore, as a vicious Horse throws his Rider, he openly beat away this Controller of all his Pleasures, and proceeded in his Journey with Folly, from whom he is inseparable. Confidence and Diffidence being, after this Manner, both thrown loose from their respective Companies, wander'd for some Time; till at last Chance led them at the same Time to one Village. Confidence went directly up to the great House, which belong'd to WEALTH, the Lord of the Village; and without staying for a Porter, intruded himself immediately into the innermost Apartments, where he found Vice and Folly well receiv'd before him. He join'd the Train; recommended himself very quickly to his Landlord; and enter'd into such Familiarity with Vice, that he was enlisted in the same Company along with Folly. They were frequent Guests of Wealth, and from that Moment inseparable. Diffidence, in the mean Time, not daring to approach the Great House, accepted of an Invitation from POVERTY, one of the Tenants; and entering the Cottage, found Wisdom and Virtue, who being repuls'd by the Land-lord had retir'd thither. Virtue took Compassion of her, and Wisdom found, from [26] her Temper, that she wou'd easily improve: So they admitted her into their Society. Accordingly, by their Means, she alter'd in a little Time somewhat of her Manner, and becoming much more amiable and engaging, was now call'd by the Name of MODESTY. As ill Company has a greater Effect than good, Confidence, tho' more refractory to Counsel and Example, degenerated so far by the Society of Vice and Folly, as to pass by the Name of IMPUDENCE. Mankind, who saw these Societies as Jupiter first join'd them, and knew nothing of these mutual Desertions, are led into strange Mistakes by those Means; and wherever they see Impudence, make account of Virtue and Wisdom, and wherever they observe Modesty call her Attendants Vice and Folly.

[27]

ESSAY IV.

That POLITICS may be reduc'd to a SCIENCE.↩

IT is a great Question with several, Whether there be any essential Difference betwixt one Form of Government and another? and, Whether every Form may not become good or bad, according as it is well or ill administred [2] ? Were it once admitted, that all Governments are alike, and that the only Difference consists in the Character and Conduct of the Governors, most political Disputes wou'd be at an End, and all Zeal for one Constitution above another must be esteem'd mere Bigotry and Folly. But though I be a profest [28] Friend to Moderation, I cannot forbear condemning this Sentiment, and should be sorry to think, that human Affairs admit of no greater Stability, than what they receive from the casual Humours and Characters of particular Men.

'TIS true, those who maintain, that the Goodness of all Government consists in the Goodness of the Administration, may cite many particular Instances in History where the very same Government, in different Hands, varies suddenly into the two opposite Extremes of good and bad. Compare the French Government under Henry III. and under Henry IV. Cruelty, Oppression, Levity, Artifice on the Part of the Rulers; Faction, Sedition, Treachery, Rebellion, Disloyalty on the Part of the Subjects: These compose the Character of the former miserable Aera. But when the Patriot and heroic Prince, who succeeded, was once firmly seated on the Throne, the Government, the People, every Thing seem'd to be totally chang'd, and all from the Change of the Temper and Sentiments of one single Man. An equal Difference of a contrary Kind, may be found in comparing the [29] Reigns of Elisabeth and James, at least with Regard to foreign Affairs; and Instances of this Kind may be multiply'd, almost without Number, from antient as well as modern History.

BUT here I wou'd beg Leave to make a Distinction. All absolute Governments (and such the English Government was, in a great Measure, till the Middle of the last Century) must very much depend on the Administration; and this is one of the great Inconveniencies of that Form of Government. But a Republican and free Government wou'd be a most glaring Absurdity, if the particular Checks and Controuls, provided by the Constitution, had really no Influence, and made it not the Interest, even of bad Men, to operate for the public Good. Such is the Intention of these Forms of Government; and such is the real Effect, where they are wisely constituted: As on the other Hand, they are the Sources of all Disorder, and of the blackest Crimes, where either Skill or Honesty has been wanting in their original Frame and Institution. So great is the Force of Laws, and of particular Forms of Government, and so little Dependence have they [30] on the Humours and Temper of Men, that Consequences as general and as certain may be deduced from them, on most Occasions, as any which the Mathematical Sciences can afford us.

THE Roman Government gave the whole Legislative Power to the Commons, without allowing a Negative, either to the Nobility, or Consuls. This unbounded Power the Commons possessed in a collective Body, not in a Representative. The Consequences were, When the People, by Success and Conquest had become very numerous, and had spread themselves to a great Distance from the Capital, the City-Tribes, tho' the most contemptible, carried almost every Vote: They were, therefore, most cajol'd by every one who affected Popularity: They were supported in Idleness by the general Distribution of Corn, and by particular Bribes, which they received from almost every Candidate: By this Means they became every Day more licentious, and the Campus Martius was a perpetual Scene of Tumult and Sedition: Armed Slaves were introduced among these rascally Citizens; so that the whole Government fell into Anarchy, and the greatest Happiness the Romans could [31] look for, was the despotic Power of the Caesars. Such are the Effects of Democracy without a Representative.

A NOBILITY may possess the whole or any Part of the legislative Power of a State after two different Ways. Either every Nobleman shares the Power as part of the whole Body, or the whole Body enjoys the Power as composed of Parts; which have each a distinct Power and Authority. The Venetian Nobility are an Instance of the first kind of Government: The Polish of the second. In the Venetian Government the whole Body of Nobility possesses the whole Power, and no Nobleman has any Authority, which he receives not from the Whole. In the Polish Government every Nobleman, by Means of his Fiefs, has a peculiar hereditary Authority over his Vassals, and the whole Body has no Authority but what it receives from the Concurrence of its Parts. The distinct Operations and Tendencies of these two Species of Government might be made most apparent even a priori. A Venetian Nobility is infinitely preferable to a Polish, let the Humours and Education of Men be ever so much vary'd. A [32] Nobility, who possess their Power in common, will preserve Peace and Order, both among themselves, and their Subjects; and no Member can have Authority enough to controul the Laws for a Moment. They will preserve their Authority over the People, but without any grievous Tyranny, or any Breach of private Property; because such a tyranninical Government is not the Interest of the whole Body, however it may be the Interest of some Individuals. There will be a Distinction of Rank betwixt the Nobility and People, but this will be the only Distinction in the State. The whole Nobility will form one Body, and the whole People another, without any of those private Feuds and Animosities, which spread Ruin and Desolation everywhere. 'Tis easy to see the Disadvantages of a Polish Nobility in every one of these Particulars.

'TIS possible so to constitute a free Government, as that a single Person, call him Duke, Prince or King, shall possess a very large Share of the Power, and shall form a proper Ballance or Counterpoise to the other Parts of the Legislature. This chief Magistrate may be either elective or hereditary; and tho' the [33] former Institution may, to a superficial View, appear most advantageous; yet a more accurate Inspection will discover in it greater Inconveniencies than in the latter, and such as are founded on Causes and Principles eternal and immutable. The filling of the Throne, in such a Government, is a Point of too great and too general Interest not to divide the whole People into Factions: From whence a Civil War, the greatest of Ills, may be apprehended, almost with Certainty, upon every Vacancy. The Prince elected must be either a Foreigner or a Native: The former will be ignorant of the People whom he is to govern; suspicious of his new Subjects, and suspected by them; giving his Confidence entirely to Strangers, who will have no other Thoughts but of enriching themselves in the quickest Manner, while their Master's Favour and Authority is able to support them. A Native will carry into the Throne all his private Animosities and Friendships, and will never be regarded, in his Elevation, without exciting the Sentiments of Envy in those who formerly consider'd him as their Equal. Not to mention, that a Crown is too high a Reward ever to be given to Merit alone, and will always [34] induce the Candidates to employ Force, or Money, or Intrigue, to procure the Votes of the Electors: So that such a Choice will give no better Chance for a superior Merit in the Prince, than if the State had trusted to Birth alone to determine their Sovereign.

IT may therefore be pronounced as an universal Axiom in Politics, That an hereditary Prince, a Nobility without Vassals, and a People voting by their Representatives, form the best MONARCHY, ARISTOCRACY and DEMOCRACY. But in order to prove more fully, that Politics admit of general Truths, which are invariable by the Humour or Education either of Subject or Sovereign, it may not be amiss to observe some other Principles of this Science, which may seem to deserve that Character.

IT may easily be observ'd, that though free Governments have been commonly the most happy for those who partake of their Freedom; yet are they the most ruinous and oppressive for their Provinces: And this Observation may, I believe, be fix'd as a Maxim of the kind we are here speaking of. When a [35] Monarch extends his Dominions by Conquest, he soon learns to consider his old and his new Subjects as on the same Footing; because in reality all his Subjects are to him the same, except the few Friends and Favourites, with whom he is personally acquainted. He does not, therefore, make any Distinction betwixt them in his general Laws; and at the same Time is no less careful to prevent all particular Acts of Oppression in the one as in the other. But a free State necessarily makes a great Distinction, and must always do so, 'till Men learn to love their Neighbours as well as themselves. The Conquerors, in such a Government, are all Legislators, and will be sure so to contrive Matters, by Restrictions of Trade and by Taxes, as to draw some private, as well as public, Advantage from their Conquests. Provincial Governors have also a better Chance in a Republick, to escape with their Plunder, by means of Bribery or Interest; and their Fellow-Citizens, who find their own State to be inriched by the Spoils of their Subject-Provinces, will be the more inclined to tolerate such Abuses. Not to mention, that 'tis a necessary Precaution in a free State to change the Governors [36] frequently; which obliges these temporary Tyrants to be more expeditious and rapacious, that they may accumulate sufficient Wealth before they give place to their Successors. What cruel Tyrants were the Romans over the World during the Time of their Common-wealth! 'Tis true, they had Laws to prevent Oppression in their Provincial Magistrates; but Cicero informs us, that the Romans could not better consult the Interest of the Provinces than by repealing these very Laws. For, says he, in that Case our Magistrates, having entire Impunity, would plunder no more than would satisfy their own Rapaciousness: Whereas, at present, they must also satisfy that of their Judges, and of all the great Men of Rome, whose Protection they stand in need of. Who can read of the Cruelties and Oppressions of Verres without Horror and Astonishment? And, who is not touched with Indignation to hear, that after Cicero had exhausted on that abandoned Criminal all the Thunders of the most divine Eloquence, and had prevailed so far as to get him condemned to the utmost Extent of the Laws; yet that cruel Tyrant lived peaceably to old Age, in Opulence and Ease, and, thirty Years afterward, [37] was put into the Proscription by Mark Anthony, upon account of his exorbitant Wealth, where he fell, along with Cicero himself, and all the most virtuous Men of Rome? After the Dissolution of the Common-wealth, the Roman Yoke became easier upon the Provinces, as Tacitus informs us; and it may be observed, that many of the worst Emperors, Domitian, for instance, were very careful to prevent all Oppression of the Provinces. In Vespasian's Time, Gaul was esteemed richer than Italy itself: Nor do I find, during the whole Time of the Roman Monarchy, that the Empire became less rich or populous in any of its Provinces; though indeed its Valour and military Discipline were always upon the Decline. If we pass from antient to modern Times, we shall find the same Observation to hold true. The Provinces of obsolute Monarchies are always better treated than those of free States. Compare the Pais conquis of France with Ireland, and you'll be convinced of this Truth; though this latter Kingdom, being almost entirely peopled from England, possesses so many Rights and Privileges as should naturally make it challenge better Treatment than that of a [38] conquered Province. Corsica is also an obvious Instance to the same Purpose.

THERE is an Observation of Machiavel, with regard to the Conquests of Alexander the Great, which, I think, may be regarded as one of those eternal political Truths, which no Time or Accidents can vary. It may seem strange, says that Politician, that such sudden Conquests as those of Alexander, shou'd be possest so peaceably by his Successors, and that the Persians, during all the Confusions and civil Wars of the Greeks, never made the smallest Effort towards the Recovery of their former independent Government. To satisfy us concerning the Cause of this remarkable Event, we may consider, that a Monarch may govern his Subjects after two different Ways. He may either follow the Maxims of the Eastern Princes, and stretch his Power so far as to leave no Distinction of Ranks among his Subjects, but what proceeds immediately from himself; no Advantages of Birth; no hereditary Honours and Possessions: And, in a Word, no Credit among the People, except from his Commission alone. Or a Monarch may exert his Power in a milder Manner, like our European [39] Princes; and leave other Sources of Honour, beside his Smile and Favour: Birth, Titles, Possessions, Valour, Integrity, Knowledge, or brave and fortunate Atchievements. In the former Species of Government, after a Conquest, 'tis impossible ever to shake off the Yoke; since no one possesses among the People so much personal Credit and Authority as to begin such an Enterprize: Whereas in the latter Species of Government, the least Misfortune or Discord of the Victors, will encourage the Vanquish'd to take Arms, who have Leaders ready to prompt and conduct them in every Undertaking.

SUCH is the Reasoning of Machiavel, which seems to me very solid and conclusive; tho' I wish he had not mixt Falshood with Truth, in asserting that Monarchies govern'd according to the Eastern Policy, tho' more easily kept when once they are subdued, yet are the most difficult to be subdued; since they cannot contain any powerful Subject, whose Discontent and Faction may facilitate the Enterprizes of an Enemy. For besides, that such a tyrannical Government enervates the Courage of Men, and renders them indifferent [40] concerning the Fortunes of their Sovereign; besides this, I say, we find by Experience, that even the temporary and delegated Authority of the Generals and Magistrates, being always, in such Governments, as absolute within its Sphere as that of the Prince himself, is able, with Barbarians, accustom'd to a blind Submission, to produce the most dangerous and fatal Revolutions. So that, in every Respect, a gentle Government is preferable, and gives the greatest Security to the Sovereign as well as to the Subject.

LEGISLATORS, therefore, shou'd not trust the future Government of a State entirely to Chance, but ought to provide a System of Laws to regulate the Administration of public Affairs to the latest Posterity. Effects will always correspond to Causes; and wise Regulations in any Common-wealth are the most valuable Legacy, which can be left to future Ages. In the smallest Court or Office, the stated Forms and Methods, by which Business must be conducted, are found to be a considerable Check on the natural Depravity of Mankind. Why shou'd not the Case be the same in public Affairs? Can we ascribe the [41] Stability and Wisdom of the Venetian Government, thro' so many Ages, to any Thing but their Form of Government? And is it not easy to point out those Defects in the original Constitution, which produc'd the tumultuous Governments of Athens and Rome, and ended at last in the Ruin of these two famous Republics? And so little Dependence has this Affair on the Humours and Education of particular Men, that one Part of the same Republic may be wisely conducted, and another weakly, by the very same Men, merely by Reason of the Difference of the Forms and Institutions, by which these Parts are regulated. Historians inform us, that this was actually the Case with Genoa. For while the State was always full of Sedition, and Tumult, and Disorder, the Bank of St. George, which had become a considerable Part of the People, was conducted for several Ages with the utmost Integrity and Wisdom [3] .

[42]

HERE then is a sufficient Inducement to maintain, with the utmost ZEAL, in every free State, those Forms and Institutions, by which Liberty is secured, the Publick Good consulted, and the Avarice or Ambition of private Men restrained and punished. Nothing does more Honour to human Nature, than to see it susceptible of so noble a Passion; as nothing can be a greater Indication of Meanness of Heart in any Man, than to see him devoid of it. A Man who loves only himself, without Regard to Friendship or Merit, is a detestable Monster; and a Man, who is only susceptible of Friendship, without publick Spirit, or a Regard to the Community, is deficient in the most material Part of Virtue.

BUT this is a Subject that need not be longer insisted on at present. There are enough of Zealots on both Sides to kindle up the Passions of their Partizans, and under the Pretence of publick Good, pursue the Interests [43] and Ends of their particular Faction. For my Part, I shall always be more fond of promoting Moderation than Zeal; though perhaps the surest Way of producing Moderation in every Party is to encrease our Zeal for the Public. Let us, therefore, try, if it be possible, from the foregoing Doctrine, to draw a Lesson of Moderation, with regard to the Parties, in which our Country is at present divided; at the same Time that we allow not this Moderation to abate the Industry and Passion with which every Individual is bound to pursue the Good of his Country.

THOSE who either attack or defend a Minister in such a Government as ours, where the utmost Liberty is allowed, always carry Matters to Extremes, and exaggerate his Merit or Demerit with regard to the Publick. His Enemies are sure to charge him with the greatest Enormities, both in domestic and foreign Management; and there is no Meanness or Crime, of which, in their Account, he is not capable. Unnecessary Wars, scandalous Treaties, Profusion of public Treasure, oppressive Taxes, every kind of Male-administration is ascribed to him. To aggravate the [44] Charge, his pernicious Conduct, it is said, will extend its baneful Influence even to Posterity, by undermining the best Constitution in the World, and disordering that wise System of Laws, Institutions and Customs, by which our Ancestors, for so many Centuries, have been so happily governed. He is not only a wicked Minister in himself, but has removed every Security provided against wicked Ministers for the future.

ON the other Hand, the Partizans of the Minister make his Panegyric run as high as the Accusation against him, and celebrate his wise, steady, and moderate Conduct in every Part of his Administration. The Honour and Interest of the Nation supported abroad, public Credit maintain'd at home, Persecution restrain'd, Faction subdu'd; the Merit of all these Blessings is ascrib'd solely to the Minister. At the same Time, he crowns all his other Merits, by a religious Care of the best Constitution in the World, which he has preserv'd inviolate in all its Parts, and has transmitted entire, to be the Happiness and Security of the latest Posterity.

[45]

WHEN this Accusation and Panegyric are receiv'd by the Partizans of each Party, no Wonder they engender a most extraordinary Ferment on both Sides, and fill the whole Nation with the most violent Animosities. But I wou'd fain perswade these Party-Zealots, that there is a flat Contradiction both in the Accusation and Panegyric, and that it were impossible for either of them to run so high, were it not for this Contradiction; if our Constitution be really [4] that noble Fabric, the pride of Britain, the Envy of our Neighbours, rais'd by the Labour of so many Centuries, repair'd at the Expence of so many Millions, and cemented by such a Profusion of Blood; I say, if our Constitution does in any Degree deserve these Elogiums, it wou'd never have endur'd a wicked and a weak Minister to govern triumphantly for a Course of Twenty Years, when oppos'd by the greatest Geniuses of the Nation, who exercis'd the utmost Liberty of Tongue and Pen, in Parliament, and in their frequent Appeals to the People. But if the Minister be wicked and weak, to the Degree so strenuously insisted on, the Constitution [46] must be faulty in its original Principles, and the Minister cannot consistently be charg'd with undermining the best Constitution of the World. A Constitution is only so far good, as it provides a Remedy against Male-administration; and if the British Constitution, when in its greatest Vigour, and repair'd by two such remarkable Events, as the Revolution and Accession, by which our antient Royal Family was sacrificed to it; if our Constitution, I say, with so great Advantages, does not, in Fact, provide any such Remedy against Male-administration, we are rather beholden to any Minister, that undermines it, and affords us an Opportunity of erecting a better Constitution in its Place.

I WOU'D make Use of the same Topics to moderate the Zeal of those who defend the Minister. If our Constitution be so excellent, a Change of Ministry can be no such dreadful Event; since 'tis essential to such a Constitution, in every Ministry, both to preserve itself from Violation, and to prevent all Enormities in the Administration. If our Constitution be bad, so extraordinary a Jealousy and Apprehension, on Account of Changes, is illplac'd; [47] and a Man shou'd no more be anxious in this Case, than a Husband, who had marry'd a Woman from the Stews, shou'd be watchful to prevent her Infidelity. Public Affairs, in such a Constitution, must necessarily go to Confusion by whatever Hands they are conducted; and the Zeal of Patriots is much less requisite in that Case than the Patience and Submission of Philosophers. The Virtue and good Intentions of Cato and Brutus are highly laudable; But to what Purpose did their Zeal serve? To nothing, but to hasten the fatal Period of the Roman Government, and render its Convulsions and dying Agonies more violent and painful.

I WOU'D not be understood to mean, that public Affairs deserve no Care and Attention at all. Wou'd Men be moderate and consistent, their Claims might be admitted; at least, might be examin'd. The Country Party might still assert, that our Constitution, tho' excellent, will admit of Male-administration to a certain Degree; and therefore, if the Minister be bad, 'tis proper to oppose him with a suitable Degree of Zeal. And on the other Side, the Court-Party may be allow'd, upon [48] the Supposition, that the Minister were good, to defend, and with some Zeal too, his Administration. I wou'd only perswade Men not to contend, as if they were fighting pro aris & focis, and change a good Constitution into a bad one, by the Violence of their Factions.

I HAVE not here consider'd any Thing that is personal in the present Controversy. In the best Constitution of the World, where every Man is restrain'd by the most rigid Laws; 'tis easy to discover either the good or bad Intentions of a Minister, and to judge, whether his personal Character deserves Love or Hatred. But such Questions are of little Importance to the Public, and ly under a just Suspicion either of Malevolence or Flattery in those who employ their Pens upon them.

[49]

ESSAY V.

Of the first PRINCIPLES of GOVERNMENT.↩

NOTHING is more surprising to those, who consider human Affairs with a Philosophical Eye; than to see the Easiness with which the many are governed by the few, and to observe the implicite Submission with which Men resign their own Sentiments and Passions to those of their Rulers. When we enquire by what Means this Wonder is brought about, we shall find, that as FORCE is always on the Side of the Governed, the Governors have nothing to support them but OPINION. 'Tis therefore, on Opinion only that Government is founded; and this Maxim extends to the most despotick and most military Governments, as well as to the most free and most popular. The Soldan of Aegypt, or [50] the Emperor of Rome, might drive his harmless Subjects, like brute Beasts, against their Sentiments and Inclination: But he must, at least, have led his Mamalukes, or Praetorian Bands, like Men, by their Opinion.

OPINION is of two Kinds, viz. Opinion of INTEREST, and Opinion of RIGHT. By Opinion of Interest, I chiefly understand the Sense of the public Advantage which is reapt from Government; along with the Perswasion, that the particular Government, which is establish'd, is equally advantageous with any other that cou'd easily be settled. When this Opinion prevails among the Generality of a State, or among those who have the Force in their Hands, it gives great Security to any Government.

RIGHT is of two Kinds, Right to POWER, and Right to PROPERTY. What Prevalence Opinion of the first Kind has over Mankind, may easily be understood by observing the Attachment, which all Nations have to their antient Government, and even to those Names, which have had the Sanction of Antiquity. Antiquity always begets the Opinion of Right; [51] and whatever disadvantageous Sentiment we may entertain of Mankind, they are always found to be prodigal both of Blood and Treasure, in the Maintenance of public Right. This Passion we may denominate Enthusiasm, or may give it what Appellation we please; but a Politician, who wou'd overlook its Influence on human Affairs, wou'd prove himself to have but a very limited Understanding.

'TIS sufficiently understood, that the Opinion of Right to Property is of the greatest Moment in all Matters of Government. A noted Author has made Property the Foundation of all Government; and most of our political Writers seem inclin'd to follow him in that Particular. This is carrying the Matter too far; but still it must be own'd, that the Opinion of Right to Property has a great Influence in this Subject.

UPON these three Opinions, therefore, of Interest, of Right to Power, and of Right to Property, are all Governments founded, and all Authority of the few over the many. There are indeed other Principles, which add Force to these, and determine, limit, or alter their [52] Operation; such as Self-Interest, Fear, and Affection: But still I assert, that these other Principles can have no Influence alone, but suppose the antecedent Influence of those Opinions above-mention'd. They are, therefore, to be esteem'd the secondary, not the original Principles of Government.

FOR first, as to Self-Interest, by which I mean the Expectation of particular Rewards, distinct from the general Protection which we receive from Government; 'tis evident, that the Magistrate's Authority must be antecedently establish'd, or at least be hop'd for, in order to produce this Expectation. The Expectation of Reward may augment the Authority with regard to some particular Persons; but can never give Birth to it with regard to the Public. Men naturally look for the greatest Favours from their Friends and Acquaintance; and therefore, the Hopes of any considerable Number of the State, wou'd never center in any particular Set of Men, if these Men had no other Title to Magistracy, and had no Influence over the Opinions of Mankind. The same Observation may be extended to the other two Principles of Fear and [53] Affection. No Man wou'd have any Reason to fear the Fury of a Tyrant, if he had no Authority over any but from Fear; since, as a single Man, his bodily Force can reach but a small Way, and whatever Power he has beyond, must be founded either on our own Opinion, or on the presum'd Opinion of others. And tho' Affection to Wisdom and Virtue in a Sovereign extends very far, and has great Influence; yet he must be antecedently suppos'd to be invested with a publick Character, otherwise the public Esteem will serve him in no Stead, nor will his Virtue have any Influence beyond his private Sphere.

A GOVERNMENT may endure for several Ages, though the Ballance of Power, and the Ballance of Property do not agree. This chiefly happens, where any Member of the State has acquired a large Share of the Property; but from the original Constitution of the Government has no Share of the Power. Under what Pretext would any Individual of that Order pretend to intermeddle in public Affairs? As Men are commonly much attacht to their antient Government, it is not to be expected, that the Public would ever favour [54] such Usurpations. But where the original Constitution allows any Share of the Power, though small, to an Order of Men, that possesses a large Share of Property, 'tis easy for them gradually to stretch their Authority, and bring the Ballance of Power to coincide with that of Property. This has been the Case with the House of Commons in England.

MOST Writers, that have treated of the British Government, have supposed, that as the House of Commons represents all the Commons of Great-Britain; so its Weight in the Scale is proportioned to the Property and Power of all whom they represent. But this Principle must not be received as absolutely true. For though the People are apt to attach themselves more to the House of Commons than to any other Member of the Constitution, that House being chosen by them as their Representatives, and as the public Guardians of their Liberty; yet are there Instances where the House, even when in Opposition to the Crown, has not been follow'd by the People; as we may particularly observe in the Tory House of Commons in the Reign of King William. Were the Members [55] of the House obliged to receive Instructions from their Constituents, like the Dutch Deputies, this would entirely alter the Case; and if such immense Power and Riches, as those of the whole Commons of Britain, were brought into the Scale, 'tis not easy to conceive, that the Crown could either influence that Multitude of People, or withstand that Over-ballance of Property. 'Tis true, the Crown has great Influence over the collective Body of Britain in the Elections of Members; but were this Influence, which at present is only exerted once in seven Years, to be employ'd in bringing over the People to every Vote, it would soon be wasted; and no Skill, Popularity or Revenue could support it. I must, therefore, be of Opinion, that an Alteration in this particular would introduce a total Alteration in our Government, and would soon reduce it to a pure Republic; and perhaps, to a Republic of no inconvenient Form. For though the People collected in a Body, like the Roman Tribes, be quite unfit for Government, yet when dispersed in small Bodies, they are more susceptible both of Reason and Order; the Force of popular Currents and Tides is, in some Measure, broke; and the [56] public Interest may be pursued with Method and Constancy. But 'tis needless to reason any farther concerning a Form of Government, which is never likely to have place in Britain, and which seems not to be the Aim of any Party amongst us. Let us cherish and improve our antient Government as much as possible, without encouraging a Passion for such dangerous Novelties.

I SHALL conclude this Subject with observing, that the present political Controversy, with regard to Instructions, is a very frivolous one, and can never be brought to any Decision, as it is managed by both Parties. The Country-Party do not pretend, that a Member is absolutely bound to follow such Instructions, as an Ambassador or General is confined by his Orders, and that his Vote is not to be received in the House but so far as it is conformable to them. The Court-Party, again, do not pretend, that the Sentiments of the People ought to have no Weight with every Member; much less that he ought to despise the Sentiments of those whom he represents, and with whom he is more particularly connected. And if their Sentiments be [57] of Weight, why ought they not to express these Sentiments? The Question, then, is only concerning the Degrees of Weight, which ought to be plac'd on Instructions. But such is the Nature of Language, that 'tis impossible for it to express distinctly these different Degrees; and if Men will carry on a Controversy on this Head, it may well happen, that they may differ in their Language, and yet agree in their Sentiments; and differ in their Sentiments, and yet agree in their Language. Besides, how is it possible to fix these Degrees, considering the Variety of Affairs that come before the House, and the Variety of Places, which Members represent? Ought the Instructions of Totness to have the same Weight as those of London? Or Instructions, with regard to the Convention, which respected foreign Politics, to have the same Weight as those with regard to the Excise, which respected only our domestic Affairs?

[59]

ESSAY VI.

Of LOVE and MARRIAGE.↩

I Know not whence it proceeds, that Women are so apt to take amiss every Thing that is said in Disparagement of the married State; and always consider a Satyr upon Matrimony as a Satyr upon themselves. Do they mean by this, that they are the Parties principally concerned, and that if a Backwardness to enter into that State should prevail in the World, they would be the greatest Sufferers? Or, are they sensible, that the Misfortunes and Miscarriages of the married State are owing more to their Sex than to ours? I hope they do not intend to confess either of these two Particulars, or to give such an Advantage to their Adversaries, the Men, as even to allow them to suspect it.

[60]

I HAVE often had Thoughts of complying with this Humour of the Fair Sex, and of writing a Panegyric upon Marriage: But, in looking around for Materials, they seem'd to be of so mix'd a Nature, that at the Conclusion of my Reflections, I found I was as much dispos'd to write a Satyr, which might be plac'd on the opposite Pages of my Panegyrick: And I am afraid, that as Satyr is, on most Occasions, thought to have more Truth in it than Panegyric, I shou'd have done their Cause more Harm than Good by this Expedient. To misrepresent Facts is what, I know, they will not require of me. I must be more a Friend to Truth, than even to them, where their Interests are opposite.

I SHALL tell the Women what it is our Sex complains of most in the married State; and if they be disposed to satisfy us in this Particular, all the other Differences will be easily accomodated. If I be not mistaken, 'tis their Love of Dominion which is the Ground of the Quarrel; though 'tis very likely, that they will think it an unreasonable Love of it in us, which makes us insist so much upon that Point. However this may be, no Passion [61] seems to have more Influence on female Minds than this for Power; and there is a remarkable Instance in History of its prevailing above another Passion, which is the only one that can be supposed a proper Counter-poise for it. We are told, that all the Women in Scythia once conspired against the Men, and kept the Secret so well, that they executed their Design before they were suspected. They surprised the Men in Drink, or asleep, bound them all fast in Chains, and having called a solemn Council of the whole Sex, it was debated what Expedient should be used to improve the present Advantage, and prevent their falling again into Slavery. To kill all the Men did not seem to the Relish of any Part of the Assembly, notwithstanding the Injuries formerly receiv'd; and they were afterwards pleased to make a great Merit of this Lenity of theirs. It was, therefore, agreed to put out the Eyes of the whole male Sex, and thereby resign for ever after all the Vanity they could draw from their Beauty, in order to secure their Authority. We must no longer pretend to dress and Show, say they; but then we shall be free from Slavery. We shall hear no more tender [62] Sighs; but in return we shall hear no more imperious Commands. Love must for ever leave us; but he will carry Subjection along with him.

'TIS regarded by some as an unlucky Circumstance, since the Women were resolved to main the Men, and deprive them of some of their Senses, in order to render them humble and dependent, that the Sense of hearing could not serve their Purpose, since 'tis probable the Females would rather have attack'd that than the Sight: And I think it is agreed among the Learned, that, in a married State, 'tis not near so great an Inconvenience to lose the former Sense as the latter. However this may be, we are told by modern Anecdotes, that some of the Scythian Women did secretly spare their Husbands Eyes; presuming, I suppose, that they could govern them as well by means of that Sense as without it. But so incorrigible and intractable were these Men, that their Wives were all obliged in a few Years, as their Youth and Beauty decay'd, to imitate the Example of their Sisters; which it was no difficult Matter to do in a State where the female Sex had once got the Superiority.

[63]

I KNOW not if our Scotish Ladies derive any Thing of this Humour from their Scythian Ancestors; but I must confess, that I have often been surpriz'd to see a Woman very well pleas'd to take a Fool for her Mate, that she might govern with the less Controul; and cou'd not but think her Sentiments, in this Respect, still more barbarous than those of the Scythian Women above-mention'd, as much, as the Eyes of the Understanding are more valuable than those of the Body.

BUT to be just, and to lay the Blame more equally, I am afraid it is the Fault of our Sex, if the Women be so fond of Rule, and that if we did not abuse our Authority, they wou'd never think it worth while to dispute it. Tyrants, we know, produce Rebels; and all History informs us, that Rebels, when they prevail, are apt to become Tyrants in their Turn. For this Reason, I cou'd wish there were no Pretensions to Authority on either Side; but that every Thing was carry'd on with perfect Equality, as betwixt two equal Members of the same Body. And to induce both Parties to embrace those amicable Sentiments, I shall [64] deliver to them Plato's Account of the Origin of Love and Marriage.

MANKIND, according to that fanciful Philosopher, were not, in their Original, divided into Male and Female, as at present; but each individual Person was a Compound of both Sexes, and was in himself both Husband and Wife, melted down into one living Creature. This Union, no Doubt, was very entire, and the Parts very well adjusted together, since there resulted a perfect Harmony betwixt the Male and Female, altho' they were oblig'd to be inseparable Companions. And so great was the Harmony and Happiness flowing from it, that the ANDROGYNES (for so Plato calls them) or MEN-WOMEN, became insolent upon their Prosperity, and rebell'd against the Gods. To punish them for this Temerity, Jupiter cou'd contrive no better Expedient, than to divorce the Male-Part from the Female, and make two imperfect Beings of the Compound, which was before so perfect. Hence the Origin of Men and Women, as distinct Creatures. But notwithstanding this Division, so lively is our Remembrance of the Happiness we enjoy'd in our primaeval State, that we [65] are never at Rest in this Situation; but each of these Halves is continually searching thro' the whole Species to find the other Half, which was broken from it: And when they meet, they join again with the greatest Fondness and Sympathy. But it often happens, that they are mistaken in this Particular; that they take for their Half what no Way corresponds to them; and that the Parts do not meet nor join in with each other, as is usual in Fractures. In this Case the Union is soon dissolv'd, and each Part is set loose again to hunt for its lost Half, joining itself to every one it meets by Way of Trial, and enjoying no Rest, till its perfect Sympathy with its Partner shews that it has at last been successful in its Endeavours.

WERE I dispos'd to carry on this Fiction of Plato, which accounts for the mutual Love betwixt the Sexes in so agreeable a Manner, I wou'd do it by the following Allegory.

WHEN Jupiter had separated the Male from the Female, and had quell'd their Pride and Ambition by so severe an Operation, he cou'd not but repent him of the Cruelty of his Vengeance, [66] and take Compassion on poor Mortals, who were now become incapable of any Repose or Tranquility. Such Cravings, such Anxieties, such Necessities arose, as made them curse their Creation, and think Existence itself a Punishment. In vain had they Recourse to every other Occupation and Amusement. In vain did they seek after every Pleasure of Sense, and every Refinement of Reason. Nothing cou'd fill that Void, which they felt in their Hearts, or supply the Loss of their Partner, who was so fatally separated from them. To remedy this Disorder, and to bestow some Comfort, at least, on human Race in their forelorn Situation, Jupiter sent down LOVE and HYMEN to collect the broken Halves of human Kind, and piece them together, in the best Manner possible. These two Deities found such a prompt Disposition in Mankind to unite again in their primitive State, that they proceeded on their Work with wonderful Success for some Time; till at last, from many unlucky Accidents, Dissension arose betwixt them. The chief Counsellor and Favourite of Hymen was CARE, who was continually filling his Patron's Head with Prospects of Futurity; a Settlement, Family, Children, Servants; so [67] that little else was regarded in all the Matches they made. On the other Hand, Love had chosen PLEASURE for his Favourite, who was as pernicious a Counsellor as the other, and wou'd never allow Love to look beyond the present momentary Gratification, or the satisfying of the prevailing Inclination. These two Favourites became, in a little Time, irreconcilable Enemies, and made it their chief Business to undermine each other in all their Undertakings. No sooner had Love fixt upon two Halves, which he was cementing together, and forming to a close Union, but Care insinuates himself, and bringing Hymen along with him, dissolves the Union produc'd by Love, and joins each Half to some other Half, which he had provided for it. To be reveng'd of this, Pleasure creeps in upon a Pair already join'd by Hymen; and calling Love to his Assistance, they Under-hand contrive to join each Half, by secret Links, to Halves, which Hymen was wholly unacquainted with. It was not long before this Quarrel was felt in its pernicious Consequences; and such Complaints arose before the Throne of Jupiter, that he was oblig'd to summon the offending Parties to appear before him, in order to give [68] an Account of their Proceedings. After hearing the Pleadings on both Sides, he order'd an immediate Reconcilement betwixt Love and Hymen, as the only Expedient for giving Happiness to Mankind: And that he might be sure this Reconcilement shou'd be durable, he laid his strict Injunctions on them never to join any Halves without consulting their Favourites, Care and Pleasure, and obtaining the Consent of both to the Conjunction. Where this Order is strictly observ'd, the Androgyne is perfectly restor'd, and human Race enjoy the same Happiness as in their primaeval State. The Seam is scarce perceiv'd, that joins the two Beings together; but both of them combine to form one perfect and happy Creature.

[69]

ESSAY VII.

Of the STUDY of HISTORY.↩

THERE is nothing I would recommend more earnestly to my female Readers than the Study of History, as an Occupation, of all others, the best suited both to their Sex and Education; much more instructive than their ordinary Books of Amusement, and more entertaining than those serious Compositions, which are usually to be found in their Closets. Among other important Truths, which they may learn from History, they may be informed of two Particulars, the Knowledge of which may contribute very much to their Quiet and Repose; That our Sex, as well as theirs, are far from being such perfect Creatures as they are apt to imagine, and, That Love is not the only Passion, that governs the Male-World, but is often overcome [70] by Avarice, Ambition, Vanity, and a thousand other Passions. Whether they be the false Representations of Mankind in those two Particulars, that endear Romances and Novels so much to the fair Sex, I know not; but must confess I am sorry to see them have such an Aversion to Matter of Fact, and such an Appetite for Falshood. I remember I was once desired by a young Beauty, for whom I had some Passion, to send her some Novels and Romances for her Amusement in the Country; but was not so ungenerous as to take the Advantage, which such a Course of Reading might have given me, being resolved not to make Use of poisoned Arms against her. I therefore sent her Plutarch's Lives, assuring her at the same Time, that there was not a Word of Truth in them from Beginning to End. She perused them very attentively, 'till she came to the Lives of Alexander and Caesar, whose Names she had heard of by Accident: and then returned me the Book, with many Reproaches for deceiving her.

I MAY indeed be told, that the fair Sex have no such Aversion to History, as I have represented, provided it be secret History, and [71] contain some memorable Transaction proper to excite their Curiosity. But as I do not find that Truth, which is the Basis of History, is at all regarded in those Anecdotes, I cannot admit of this as a Proof of their Passion for that Study. However this may be, I see not why the same Curiosity might not receive a more proper Direction, and lead them to desire Accounts of those who lived in past Ages as well as of their Contemporaries. What is it to Cleora, whether Fulvia entertains a secret Commerce of Love with Philander or not? Has she not equal Reason to be pleased, when she is informed, (what is whispered about among Historians) that Cato's Sister had an Intrigue with Caesar, and palmed her Son, Marcus Brutus, upon her Husband for his own, though in Reality he was her Gallant's? And are not the Loves of Messalina or Julia as proper Subjects of Discourse as any Intrigue, that this City has produced of late Years.

BUT I know not whence it comes, that I have been thus seduced into a kind of Raillery against the Ladies: Unless, perhaps, it proceed from the same Cause, that makes the Person, who is the Favourite of the Company, [72] be often the Object of their good-natur'd Jests and Pleasantries. We are pleased to address our selves after any manner to a Person that is agreeable to us; and at the same Time presume, that nothing will be taken amiss by one who is secure of the good Opinion and Affections of every one present. I shall now proceed to handle my Subject more seriously, and shall point out the many Advantages, that flow from the Study of History, and show how well suited it is to every one, but particularly to those who are debarred the severer Studies by the Tenderness of their Complexion and the Weakness of their Education. The Advantages found in History seem to be of three kinds, as it amuses the Fancy, as it improves the Understanding, and as it strengthens Virtue.

IN reality, what more agreeable Entertainment to the Mind, than to be transported into the remotest Ages of the World, and to observe human Society in its Infancy, making the first faint Essays towards the Arts and Sciences: To see the Policy of Government, and the Civility of Conversation refining by Degrees, and every thing that is ornamental to [73] human Life advancing towards its Perfection. To remark the Rise, Progress, Declension and final Extinction of the most flourishing Empires: The Virtues, which contributed to their Greatness; and the Vices, which drew on their Ruin. In short, to see all human Race, from the Beginning of Time, pass, as it were, in Review before us, appearing in their true Colours, without any of those Disguises, which, during their Life-time, so much perplexed the Judgments of the Beholders. What Spectacle can be imagined so magnificent, so various, so interesting? What Amusement, either of the Senses or Imagination, can be compared with it? Shall those trifling Pastimes, which engross so much of our Time, be preferr'd as more satisfactory, and more fit to engage our Attention? How perverse must that Taste be, which is capable of so wrong a Choice of Pleasures?

BUT History is a most improving Part of Knowledge, as well as an agreeable Amusement; and indeed, a great Part of what we commonly call Erudition, and value so highly, is nothing but an Acquaintance with historical Facts. An extensive Knowledge of this [74] kind belongs to Men of Letters; but I must think it an unpardonable Ignorance in Persons of whatever Sex or Condition, not to be acquainted with the History of their own Country, along with the Histories of antient Greece and Rome. A Woman may behave herself with good Manners, and have even some Vivacity in her Turn of Wit; but where her Mind is so unfurnish'd, 'tis impossible her Conversation can afford any Entertainment to Men of Sense and Reflection.