THOMAS HODGSKIN,

Travels in the North of Germany (1820)

2 vols. in 1

|

|

[Created: 10 October, 2024]

[Updated: 10 October, 2024] |

The Guillaumin Collection

|

This title is part of “The Guillaumin Collection” within “The Digital Library of Liberty and Power”. It has been more richly coded and has some features which other titles in the library do not have, such as the original page numbers, formatting which makes it look as much like the original text as possible, and a citation tool which makes it possible for scholars to link to an individual paragraph which is of interest to them. These titles are also available in a variety of eBook formats for reading on portable devices. |

Source

, Travels in the North of Germany, describing the Present State of the Social and Political Institutions, the Agriculture, Manufactures, Commerce, Education, Arts and Manners in that Country, particularly in the Kingdom of Hannover, 2 vols. (Edinburgh: Archibald Constable, 1820).http://davidmhart.com/liberty/EnglishClassicalLiberals/Hodgskin/1820-TravelsNorthGermany/index.html

Thomas Hodgskin, Travels in the North of Germany, describing the Present State of the Social and Political Institutions, the Agriculture, Manufactures, Commerce, Education, Arts and Manners in that Country, particularly in the Kingdom of Hannover, 2 vols. (Edinburgh: Archibald Constable, 1820).

This title is also available in a facsimile PDF of the original [vol1 and vol2] and enhanced HTML [vol1 and vol2]; and various eBook formats - HTML, PDF, and ePub.

This book is part of a collection of works by Thomas Hodgskin (1787-1869).

CONTENTS OF VOLUME I.

- Preface

- CHAPTER I.

- Dresden—Leipsic. —Comparative cleanness of the Saxons and the Bohemians.—Situation of Dresden.—Royal library.—English newspapers.—Amusements.—Singing boys.—Festivals and medals in honour of Luther.—Of students.—Of the inhabitants of Leipsic.—A funeral.—Traits of character.—A custom—Curious Christian names.—Population.—Government of Saxony.—Leave Dresden.—Salutations of peasants.—Meissen.—A deserter.—Oschatz.—Architecture of German towns.—Christmas eve.—A mode of salutation.—Extensive cultivation of music.—Arrive at Leipsic, Page 1

- CHAPTER II.

- Leipsic—Berlin. —Displeasing politeness.—Grotesque market—place.—Churches.—A picture.—Ceremony of communion.—Funeral of a student.—A beggar.—Leipsic fairs.—A peculiar privilege.—A difference of manners.—A dirty custom.—Leave Leipsic.—A rencontre.—Cause for German indolence.—Want of roads.—Wittenberg, the seat of the Reformation.—A companion.—Trauenbritzen.—Belitz.—Weakness of German children.—Royal roads.—Potsdam.—Statues in gardens.—Arrive at Berlin. p. 42

- CHAPTER III.

- Prussia. —Berlin.—Buildings.—Animation.—University.—Curious natural collection.—Journals.—Changes in government.—Provincial states.—Privileges of nobles.—Control of education.—Administration of justice.—Orders of knighthood.—Leave Berlin.—Village alehouse.—Pedlar-gambling.—A nobleman’s toll-bar.—A character.—Burg.—A statue.—Magdeburg.—How accosted.—Change in society.—Former destruction of the city.—Trade.—Marriage feast, p. 78

- CHAPTER IV.

- Brunswick—Hannover. —Helmstädt university.—Brunswick.—Tombs of the sovereigns.—Number killed in battle.—Different characters of the former Duke.—Former state of Brunswick.—For what now remarkable.—Traits of character.—Extent of territory.—Population.—Carolina college.—Roads.—Appropriate inscription.—Hildesheim.—Hannover buildings.—Monument to Leibnitz.—Library, p. 127

- CHAPTER V.

- Hannover—Hamburg. —A mode of salutation.—Effects of mockery on character.—Appearance of country.—Freedom of German manners.—Queen Matilda.—Zucht-house.—Treatment of mad people; of criminals; prisoners of state.—A farmer chief-judge.—A wax manufactory.—Agricultural society.—Institutions.—Country.—Shepherds.—Uelzen.—Paper-mill.—Cloth manufactory.—Regulation of police.—Landlady and Pastor.—Specimen of education.—Specimen of opinions.—Lüneburg.—Nobleman farmer. —An Amt Voght.—Main chaude.—Harburg.—Bridge built by Marshal Davoust, p. 153

- CHAPTER VI.

- Hamburg, and Free Towns of Germany. —A contrast.—Jungfern Stieg.—Altona road.—Activity.—Affluence and cleanliness.—A custom.—Buildings.—Börsen Halle.—Country houses.—Rainvill’s garden.—Klopstock’s grave.—A part of his character.—Dancing saloons.—Number of children born out of marriage.—Effects on moral character.—Education.—System for the relief of the poor.—Professor Büsch.—Theatre.—Otto von Wittelsbach.—Commercial travellers.—Commercial inns.—Formation of the Hanseatic league.—Former extent.—Present influence of Hanse towns.—Number of free towns.—Present form of government.—Senates.—Citizens.—Their share in the government.—Quantity of jurisconsults.—Commissions conciliatrice.—Leave Hamburg, p. 195

- CHAPTER VII.

- Free Lands Near the Elbe. —Names.—In what their freedom consisted.—How separated.—Stade.—Forlifications.—Trade.—Appearance of country.—A difference of manners.—An adventure.—An advocate.—A country parson.—Ottendorf.—Land Hadeln.—Farmers.—Servants.—General appearance.—Budjadinger Land.—Borough English.—Opinions.—A German proverb.—Royal tolls.—Provinces of Bremen and Verden, p. 240

- CHAPTER VIII.

- Bremen—Oldenburg—Friezland. —Bremen.—Public walk.—Raths Keller.—Museum.—Town house.—Character of people.—Cultivation of wastes.—Oldenburg.—Government.—Corvees.—Friezland.—Canals.—Aurick.—Track—boat.—Company.—Embden.—Former size.—Superiority of the character of the Friezlanders.—Their origin.—Division of property.—Part they take in government.—United to Prussia.—Treatment of Prussia.—United to Hannover.—Public spirit proportionate to liberty.—Disasters.—Leave Embden.—An adventure, p. 263

- CHAPTER IX.

- Papenburg—Schauenburg Lippe. —Celebrity of Papenburg.—Origin.—Meppen.—Nature of the country.—Increase of inhabitants.—Dirtiness of women.—Meddling of government.—Lingen.—Westphalia.—Osnabrück.—Ancient abode of the Saxons.—Memorials.—A linen hall.—Gardens.—A triumphal arch.—Relics of Charlemagne.—Literature of small towns.—Justus Möser.—Tolerance.—Penitentiary.—Soil of Osnabrück.—Suhlingen.—Nienburg.—Prison.—Counties of Hoya and Diepholz.—Loccum.—Mineral waters of Rehburg.—Schauenburg.—Lippe.—Arrive at Hannover, p. 296

- CHAPTER X.

- Kalenberg—The Harz. —Frey schiessen.—A national amusement.—When introduced.—Opinions of electioneering squabbles.—Mr Malchus.—Alfeld.—Eimbeck beer.—Italian and German manners.—Göttingen.—Sudden prosperity.—Situation.—Walks.—Club.—Schwarzberg-Sondershausen.—The Harz.—Osterode.—Clausthal.—Mint.—Washing and smelting houses.—A mine.—Inhabitants of the Harz.—Goslar.—Ilsenberg.—A monument.—The Brochen. —Extensive view—Lauterberg.—Manufactory of iron ornaments.—Herzberg.—Münden.—Tomb in garden, p. 328

- CHAPTER XI.

- Hannover—Statistical and Historical View. —Different provinces of Hannover.—Names and size.—Population.—Boundaries.—Historical view.—Thirty years’ war.—Union of territories.—Their extent when the Elector was called to the throne of Great Britain.—Act of settlement gave a ninth elector to Germany.—Acquisition of Bremen and Verden.—Of territory at the Congress of Vienna, p. 367

- CHAPTER XII.

- Hannover—Government. —Passive obedience characteristic of the Germans.—Former chief minister of Hannover.—Present ministry.—The chamber.—Provincial governments.—Prevent the practice of animal magnetism.—Magistracy of towns.—Power of the sovereign over them.—Character of city magistrates.—Amts what.—Police.—Government of the church.—Pastors.—Superintendents.—Consistoriums.—An anecdote.—Appointment of clergymen.—Revenues of the church.—Secularized convents.—Appointment of an abbot.—Character of the government, p. 381

- CHAPTER XIII.

- Hannover—Former States. —Six different states in Hannover.—Composition of those of Kalenberg; of Grubenhagen; of Lüneburg; of Bremen and Verden; of Hoya and Diepholz; of Hildesheim; of Friezland.—Their powers and privileges; in the fourteenth century; in the eighteenth century.—Alterations. —Causes.—Destruction of the clergy.—The dependence of the nobles.—The servility of magistrates of towns.—Resemblance to Scotland.—The power of the sovereign increased.—Points of difference between the parliament of Great Britain and the states of Germany, p. 418

- CHAPTER XIV.

- Hannover—The Present States. —When united.—Speech of the Duke of Cambridge.—Intention of forming a general assembly of the states.—How composed.—Dependent on the government.—Imperfect as a system of representation.—Proceedings secret.—Salaries of members.—States protect a right of the people.—Benefits and disadvantages of the new system.—Probable effects.—Remarks on the wish of the Germans for new constitutions, p. 450

- CHAPTER XV.

- Hannover.—The Army.—Revenue.—Taxes. —Strength of the army.—How recruited.—Landwehr.—Power of the sovereign over the people.—Military punishments.—Courts martial composed liberally.—Sources of revenue.—Domanial accounts not submitted to the public.—Taxes.—Debts.—Expenditure.—Manner of levying taxes.—Complaints, p. 480

- Endnotes to Volume I

CONTENTS OF VOLUME II.

- CHAPTER I.

- Courts for the Administration of Justice —Property the foundation of the right to administer justice.—Patrimonial courts.—Justice chanceries.—Appointments of judges.—Salaries.—Chief court of appeal.—An example of tolerance.—Curious distinction.—High reputation of this court.—Advocates.—Regulations concerning.—Effect of public pleading on their importance, p. 1

- CHAPTER II.

- Hannover—Civil Laws and Processes .—No civil code.—Different laws.—Dissimilarity between civil and criminal process.—Civil process described.—Great length.—Difference of opinion as to codes of law.—Opinions of Savigny and Thibaut, p. 26

- CHAPTER III.

- Criminal Laws—Processes and Punishments .—Criminal code of Hannover.—Remarks on it.—Unfitness of the code.—Is not followed in decisions.—What the judges do follow.—Torture abolished.—When last inflicted.—Criminal process secret.—Is regulated by the convenience of the judge.—Great length of processes.—Fail to instruct the people.—Tribunals formerly public.—Number of persons punished in Hannover in a year.—Proportion of females.—Proportion of thefts.—Cruelty of punishments.—Are more humane than formerly.—Few persons punished in Hannover for coining or forgery.—Punishments of the police.—Comparative statement of the number of persons punished in Great Britain and Hannover, p. 43

- CHAPTER IV.

- Hannover.—Appropriation of Landed Property .—Different sorts of proprietors.—The sovereign.—Nobles.—Corporations.—Free property.—Large farms.—Minute division.—Meyer tenure described.—Leibeigen tenure described.—Consequences.—An example.—Discussion and improvement.—Economists.—Farmers.—Bauers.—Middling class increasing.—Regulations influencing the number of poor.—One forbidding marriage without permission considered.—Manner of providing for poor.—A custom of exposing them.—Institution at Hersberg.—Benevolence and charity, p. 77

- CHAPTER V.

- Hannover—Agriculture .—Hannover an agricultural country.—Agriculture of economists.—Farm at Coldingen.—Sheep.—Shepherds.—The family.—Agriculture of the marsh lands.—A mode of mending the land.—Farmers respected.—Bauers contemned.—All follow the same agricultural methods.—Right of pasturage.—Course of crops.—Mode of paying wages.—Prices.—Implements.—Impediments to agriculture.—Origin of tithes.—Manners of female peasantry.—A custom of the bauers.—Plantage at Hannover, p. 110

- CHAPTER VI.

- Hannover.—Manufactories. —Linen the staple of Germany.—Quantity manufactured in Silesia.—In Westphalia.—Cotton.—Wool.—Paper.—Iron.—Imperfect division of labour.—Wages of.—Imperfection of German manufactures wrongly attributed to the national character of the people.—Caused by the monopoly and interference of governments.—The guilds, 154

- CHAPTER VII.

- Hannover.—Commerce .—Number of ships formerly.—Facilities for trade.—Commerce of rivers.—Regulations and tolls on the Elbe.—Regulations on the Weser.—Tolls.—Vessels employed on the Aller—on the Leine.—Limitations to the trade on the Ilmenau.—Tolls on roads.—Impediments to commerce in Germany.—Advantages of Britain.—Effect of Hanse towns on the commerce of Hannover.—Canals.—Roads—Posts, p. 186

- CHAPTER VIII.

- Hannover—Schools .—Education promoted by the clergy.—Regulations concerning.—Children obliged to go to school.—A learned landlord.—Institutions of the town of Hannover.—Lyceum; date; description; two customs of.—Palace-school described.—Hofrath Feder.—Girls’ school of the old town; of the new town; an opinion of the inspector.—Parish schools.—Orphan-house.—Sunday-school.—Military and Garrison-schools.—Seminary.—Bottcher the founder who; for what intended; described; self-teaching principle at; good effected by; small funds of.—Quantity of children taught on the whole.—Manner of teaching.—Precision of.—Head reckoning.—A novel method of teaching reading.—Religious instruction; effects of on children; on young men.—Punishments.—National education.—Observations, p. 211

- CHAPTER IX.

- University of Göttingen .—German universities founded by sovereigns; professors not attached to any particular sovereign.—Difference between German and English universities.—Funds of Göttingen.—Manner of living there.—Privileges of German universities.—Tribunals of Göttingen.—Number of professors; celebrated ones; what they teach; manner of teaching; specimen of minuteness; effects on character; salaries; honours.—Degradation of professors.—Consequences of patronage.—Number of students; what they learn; their importance; separation from the other classes of Society; manners; their comment; eccentricities; their unions.—Disturbance at Göttingen; by what occasioned.—Remarks, p. 262

- CHAPTER X.

- On the German Language .—Wrong criterions employed to judge languages by.—German language not unmusical; examples.—German articles redundant.—Declension of substantives redundant.—Adjectives absurdly declined.—Changes in verbs redundant.—German language complicated.—Source of the errors.—Is a rich language.—Kant; his merits and peculiarities, p. 324

- CHAPTER XI.

- Literature .—Drama.—Works of Messrs Oehlenschläger and Grillparzer; of Mr Müllner.—Guilt, a tragedy; King Yngurd, a tragedy; possess the characteristics of German literature.—Historical literature of Germany.—General characteristics of its fine literature.—Its faults and beauties, p. 346

- CHAPTER XII.

- Influence of the situation of the Germans on their Literature .—Influence of their historical situation; of their political situation; of not participating in the naval enterprises of Europe; of their education.—Their opinion as to authorship.—Of the recent date of their literature.—Share the inhabitants of Hannover take in the general literature.—Periodical publications.—Göttingsche gelehrte Anzeigen.—Freedom of the press in Hannover, p. 385

- CHAPTER XIII.

- Private Life and Morals .—Private life of a foreign people difficult to learn.—The religion of the Germans.—Toleration.—Examples of Catholic sovereigns with Protestant subjects.—Causes of tolerance.—Character and principles of Luther.—Church has no power.—Ceremony of confirmation.—Gentleness.—Instances of politeness.—Christmas presents.—Sociality.—Ceremoniousness.—Endearing epithets.—Free intercourse.—Commerce of the sexes.—Number of divorces.—Selection of wives.—Freedom of manners.—Extensive education of women.—Public display of affections.—Manner of announcing deaths and marriages, p. 402

- CHAPTER XIV.

- Alteration of Morals .—Are the morals of the Germans deteriorated?—Influence of the immorality of sovereigns.—Murder of Count Königsmark.—Former state of sexual intercourse.—State of morals according to Riesebeck.—German morals improved.—Source of the opinion that they have deteriorated, p. 443

- CHAPTER XV.

- Cassel and Frankfort .—Cassel; situation.—Wilhelms Höhe; date of its improvements; paid for by the blood of the Hessians.—The Museum.—Examples of the absurdities of learning.—Difference between Cassel and Hannover.—Fritzlar.—A tax on travellers.—Marburg.—Giessen.—Wetzlar.—Frankfort.—Fair.—Musicians, p. 467

- Appendix.

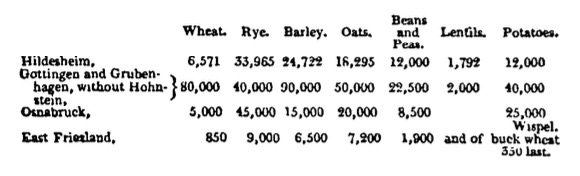

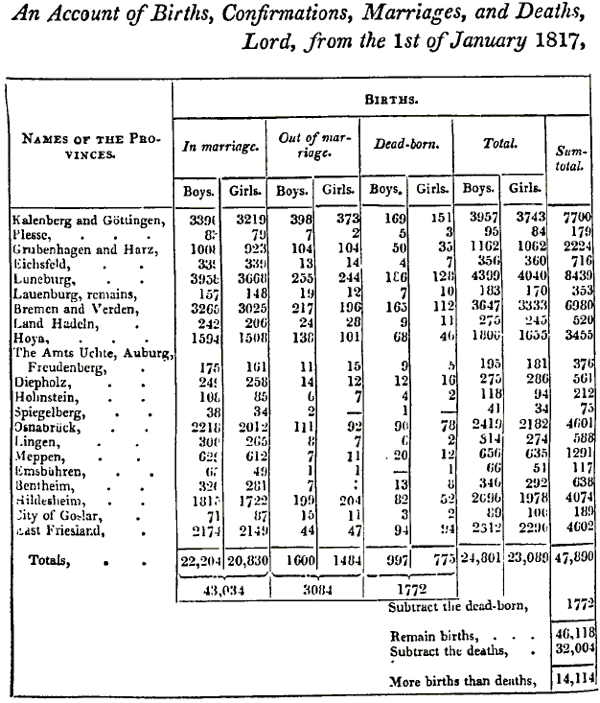

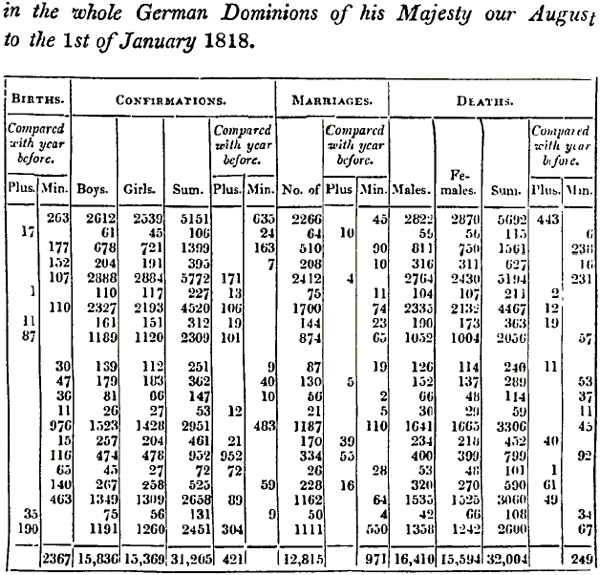

- No. I. —An Account of Births, Confirmations, Marriages, and Deaths, in the whole German Dominions of his Majesty our August Lord, from the 1st of January 1817, to the 1st of January 1818, p. 486

- No. II. —Persons composing the States of Hannover, p. 489

- No. III. — Translation. —Regulatlons for the Meeting of the General States at Hannover, the 15th December 1814, p. 494

- No. IV. —List of the Public Lectures given in one year at Göttingen, for the half year beginning in April 1818, p. 504

- No. V. —Measures, Weights, and Monies, mentioned in this Work, p. 509

- Endnotes to Volume II.

- Index

THOMAS HODGSKIN,

Travels in the North of Germany, vol. I (1820).

[I-v]

PREFACE.↩

The Work now offered to the Public contains the sum of such observations as the author had it in his power to make during a residence of some length in the North of Germany. He visited that country principally with the view of acquiring its language, and of gaining some knowledge of its literature. It was, however, suggested to him, by some of his friends, that he might be usefully employed in collecting information on the present state of the country. The governments of Northern Germany are so numerous, and individually of so little importance, that it would be more laborious than useful to describe them all. At the same time, they all resemble one another so much in their origin, [I-vi] their progress, and their present form and spirit, that an accurate account of one might be adopted as an account of the whole. Hannover was selected for the principal object of inquiry, because it was considered as interesting in itself; and though closely connected with Britain for more than a century, it happens singularly enough that less is known here regarding it than almost any other part of Germany. The observations, however, relating to the state of laws, government, agriculture, commerce, manufactories, and education in Hannover, may be applied, with few exceptions, to the other countries of the North of Germany. He has added such a portion of his travels as he thought would be interesting to the reader. Some historical notices are occasionally inserted; and many remarks are made on the effects of the public institutions which are described, on the German language and literature; and on the character and amusements of such classes of people as he had an opportunity of observing.

The author is too well aware of his own deficiencies to offer any other portion of [I-vii] his three years’ travels to the public than that which seems likely to be rendered acceptable from the importance which the present state of Germany gives to any observations relative to it. France and Italy, which he also visited, have been so often and so well described as to render any thing that he could say of them little more than a repetition of what has been said before. But the extraordinary developement of political feeling, and fermentation of ideas now taking place in Germany, allow him to hope that his observations on the present condition of its inhabitants may be, without presumption, presented to the public, although not clothed in the first style of elegance and learning. That nation, as if suddenly awakened from a long slumber, seems eager to overtake those communities which have started before it in the career of social improvement. In the excess of its zeal it appears to lose sight of the best means of obtaining the advantages for which it is struggling, and sometimes to exasperate the opposition it is unavoidably exposed to by using unnecessary violence. To [I-viii] enable us to judge what chance the Germans have of succeeding in their efforts to ameliorate their political condition, and to know if what they seek be better than what they possess, it is necessary to know those minute circumstances in the structure of their society which are continually operating on their character, and which tend to modify the more important constitutional laws.

Germany was formerly known to the rest of Europe as a great nursery of soldiers; but it is now distinguished, in an extraordinary degree, for its literary and political enthusiasm. The descendants of those philosophers whose principal ambition was to seek terms of fulsome adulation to express their submission and devotedness to their sovereigns, criticise, with bold and honest freedom, the measures of their present rulers; and are recognized by the German public as the censors and judges of men in power, and as the organs of national sentiment. The princes, formerly accustomed to look on their subjects as property to be sold at their pleasure, now find themselves controlled by [I-ix] public opinion; and, even in their worst measures, they profess a deference for its authority. These extensive and rapid changes, which are, in all probability, the precursors of other changes still more important, confer an interest on every subject connected with Germany, and anxiously fix the attention of political philosophers on its progress and future destiny.

The author has adverted to some defects in the system of government which exists in Germany; he has endeavoured to acquire an accurate notion of the composition of the ancient parliaments or states, of the nature of the new constitutions demanded, and of that which has actually been given to Hannover. Details of this kind, however, are inadequate to explain the irritation which now exists in different parts of Germany. Promises made and broken; hopes of improvement excited only to be beat down as sedition when their fulfilment was demanded; growing prosperity nipped in the bud by a change of masters and of measures; nations numbered, and transferred like cattle from one political dealer to another; are, indeed, [I-x] powerful motives for discontent, but they are local only; while discontent and a desire of change appear to disturb the repose of all Europe.

In countries in every stage of improvement, from our own mighty and well-cultivated island, where a free press has enlightened the people, and where machinery has rendered the unaided labour of the hand nearly valueless; to others at the bottom of the scale, where neither spinning-jennies nor steam-engines are known, and where industry is confined to tilling the ground, there is the same species of comparative poverty and increasing dissatisfaction. These evils may be greater in one country than another,—but they everywhere exist, and everywhere disturb the peace of society. So general a disease can arise from no local cause, or temporary circumstances: it cannot be occasioned by preaching demagogues, or enthusiastic assassins. These may be brought forth, like Hunt and Sandt, by the wants or the irritation of the moment, but they are only the excrescences, if he may so speak, of a feeling which [I-xi] appears permanent and nearly universal. This feeling, which seems to be co-extensive in every country, with the diffusion of knowledge among the governed part of the society, seems principally to arise from the total unfitness of those ancient institutions, which are so pertinaciously supported, to the wants, capacities, and intelligence of the present generation. We might pardon the presumption of men who should endeavour to legislate for a distant country, which they only knew by report. But what terms can express the absurdity of legislating for an unborn world, of the whole circumstances of which we are necessarily ignorant? Everywhere we see statesmen torturing human nature, in order to adapt it to their antiquated regulations. The opposition which ensues—the efforts which are made to resist and to subdue resistance—the expensive apparatus which is thus everywhere necessary to support governments, must, more than any local circumstances, be considered as the causes of the general discontent and misery.

Though these may be partly occasioned [I-xii] by population outrunning subsistence, of which doctrine, however, legislators appear till within these few years to have been perfectly ignorant, they are by no means wholly accounted for by it. According to it we might expect with an increase of population great absolute poverty. We see, on the contrary, however, absolute wealth and only comparative poverty; or the capital of Europe has increased faster than its population. So that, if the means of subsistence or the capital, now possessed by every European society, be compared with the absolute amount of its population, it will be found greater than at any former period. Hence it seems probable that there is something fundamentally wrong in the very principles of European legislation, which may be learned by diligent investigation.

When the United States are compared with Spain, Holland with Italy, some circumstances, common to them all, may be discovered, which impede prosperity in some, and destroy it in others. Hannover may be considered as in a middle state, or as one of those nearly stationary countries, [I-xiii] in which so much is consumed that nothing remains as a nucleus for continual increase, and where things are so much regulated, that change and improvement are alike prevented. In this point it seems calculated to serve as a lesson to those politicians who have a passion for petty legislation. Social regulations the most minute and most numerous, and a perfect obedience on the part of the people, distinguish that country. The government went on in its own course, perfectly undisturbed, till the country was occupied by the French. The credit of good intentions must be given to it, for its professions of a fatherly care for its subjects have been unbounded. Its power has been nearly unlimited. The actual condition of its subjects, their progress in the arts, the events of their history, tell clearly what the government has effected.

Hannover, which has otherwise few charms for the traveller, is not uninteresting to the political philosopher. It possesses none of the wonders of nature, nor of the magical creations of art; it has no splendid buildings, and no majestic ruins of [I-xiv] ancient glory. With many fine rivers, and a considerable territory, containing valuable minerals, it has never been a commercial or manufactural nation, and has never shone on the political hemisphere like Holland, Genoa, and Venice. Prosperous countries arrest our attention to inquire into the causes of their welfare, and Hannover has a claim to our notice, because it has never been prosperous. The fields of the sluggard are as instructive as those of the industrious man, and, from a nation that has never risen to eminence, the causes may be learnt of the eminence of others.

Hannover is well supplied with schools for elementary education, and they are here described at some length. Göttingen may serve, in some measure, as a specimen of German universities. An account of it is given, with such remarks as serve to explain the importance of the German students, and the means by which they are made a distinct body from the rest of the society. At a time when an education-committee, in our country, seems disposed to subject education to the control [I-xv] of the legislature, it may be of some importance to remark, that the whole education of Germany is directed and controlled by the governments of that country. And excellent as it may be considered, it has not been so efficacious in nourishing either active or speculative talents as education in our country, where it has hitherto nearly escaped the all-regulating ambition of the magistrate.

Whatever relates to criminal jurisprudence is at present deservedly much attended to in our country. Such information as could be obtained is, therefore, given regarding that of Hannover. A list of the punishments inflicted in one year was procured, and some of the prisons were visited. Facts relative to the effects of punishment seem yet to be wanted to enable us to decide with precision on the principles which are the foundation of criminal law. One which is here presented may be worthy of repetition.—Adultery has long been punished as a crime both in France and Germany, and chastity is more frequently violated in those countries than in Britain. Forgery, and every other kind [I-xvi] of theft, is more severely punished in Britain than in France, and yet every man who has visited the latter country must be convinced, from the manner in which silver spoons and forks are used in the meanest auberge or restaurateur’s, as well as from the official statement of crimes committed in that country, which has been published, that theft and forgery are more rare in France than in England. This fact deserves the serious consideration of every advocate of severe criminal laws.

The author is sensible that he has left many points untouched, and has treated others very imperfectly. Since his return he has found reason to regret, as many other travellers much superior to him have also done, that he had not laid in a greater stock of preparatory knowledge before he left his country. Some of the deficiencies must, however, be attributed to the difficulty of obtaining information. The Germans have an abundance of works full of statistical calculations, but they have very few which critically examine the constitution of their country, or which explain the effects of their most important [I-xvii] laws. To mention the cause of an omission, however, does not always excuse it, and the critic will still find many opportunities to exercise his forbearance.

The author has never been much accustomed to composition, and when he began this Work he had been for a considerable time more in the habit of using a foreign language than his native tongue. He is now aware that this circumstance has produced many inaccuracies of style, of which, however, he was insensible till it was too late to remedy them. He hopes they are not so great as to render the text obscure, and he trusts that faults which amount only to inelegance of expression may be pardoned in a man whose pretensions to authorship are of a humble kind.

It seems as if we had long been celebrated for corrupting the orthography of other nations. Leghorn for Livorno, and Munich for München, are examples, and travellers very often take the liberty of correcting such errors as fall in their way. Dr Clarke has written Tronyem for Drontheim, and, in compliance with the orthography of the Germans, Hannover is here [I-xviii] written with two nn s. When the Germans write Hanover, the stroke over the n signifies that it ought to be doubled, and, imitating this manner of writing it, without paying attention to the stroke, has probably been the cause why we have written it with one n only. The German orthography is also followed in writing such words as bauer instead of boor,—Reichs-Thaler instead of Rix-Dollar, and others. Boor, which we have borrowed from the Dutch, implies something stupid and contemptible, which characteristics ought not to be applied to the peasantry of Germany. Bauer accurately expresses their occupation; they are the labourers or architects of the ground. Reichs-Thaler is a coin different in value from a Spanish dollar, and circulated under the guarantee of the empire, or reich. Rix-dollar is only a corruption of the same words. Some titles of office and of dignities are also preserved in the original, because the usual translation either gives a very imperfect or a very false idea of the office signified. Thus amtman, (for example,) which is usually translated by the French word bailie, [I-xix] has led some authors to speak of a respectable magistrate as the officer of a spunging-house. There are innumerable honorary titles to which we have nothing corresponding. Hofrath (translated court-councillor) confers a certain rank on the persons to whom it is given. This, and other similar titles, are sometimes used without being translated.

With these few preliminary remarks, the author commits the work to the judgment of the public. Although his inquiries into the social regulations and manners of another nation have been a source of enjoyment to him, he cannot promise himself that this will not be his only reward. It will, however, be a double gratification to him if his labours, in their present form, shall give either amusement or information to his readers.

Edinburgh, December 27, 1819.

[I-xx]

Errata↩

| VOL. I. | |||

| Page | 19, | The number of square miles requires to be multiplied by 4. | |

| 184, | for tons read hundred weight,—through the page. | ||

| 303, | note, | for pelli read velli | |

| 346, | line 10, | for Auhalt read Anhalt | |

| 347, | 18, | dele sort | |

| 372, | 2, | for Cherushers read Cheruskers | |

| VOL II. | |||

| Page | 37, | line 24 | for unsere read unsrer |

| — | — | for zur read für | |

| 87, | 26, | after law add (.) | |

| 131, | 8, | for grosscher read grosschen | |

| 149, | 9, | for to read of. |

[I-1]

TRAVELS IN GERMANY.

CHAPTER I.

dresden—leipsic.↩

Comparative cleanness of the Saxons and the Bohemians.—Situation of Dresden.—Royal library.—English newspapers.—Amusements.—Singing boys.—Festivals and medals in honour of Luther.—Of students.—Of the inhabitants of Leipsic.—A funeral.—Traits of character.—A custom—Curious Christian names.—Population.—Government of Saxony.—Leave Dresden.—Salutations of peasants.—Meissen.—A deserter.—Oschatz.—Architecture of German towns.—Christmas eve.—A mode of salutation.—Extensive cultivation of music.—Arrive at Leipsic.

After having travelled on foot, and generally alone, through part of France, Italy, Switzerland, the Tyrol, and the south of Germany, in the years 1815, 1816, 1817, I arrived at Dresden in the early part of the month of September 1817. It was only during my residence in this town that I acquired a sufficient knowledge of the German language to enable me partially to comprehend German literature, and to converse with Germans. At this period, therefore, my remarks on Germany commence.

[I-2]

The first house I entered in Saxony, after coming from Bohemia, gave me a favourable idea of the Saxons. The floor was sanded; the tables, though made of fir, and edged with copper, like those which are most frequently in use, were kept washed, and looked white; the pewter pots were shining and clean, and a neat-dressed woman was sitting and sewing. All this was extremely different from any thing I had seen in passing from Vienna to Presburg, to Olmütz, Prague, and to Saxony. Through the whole of this route, the floors appeared rarely swept. It was nearly impossible to tell of what wood the tables were made without scraping them; and Bohemian landlords, who are proverbial in their own country for fatness and insolence, were equally dirty and disgusting. Much of Bohemia is a naturally fertile and fine country, but the people are yet so little acquainted with comforts, that they have hardly any other beds for themselves than straw; and the traveller, even in the large towns, is rarely provided with any other than straw strewed in the public room. This may possibly arise from a great quantity of foot travellers, Jew merchants, and mechanics, who are not rich enough to pay for beds, and the innkeepers, accustomed to them only, provide none. All travellers seem subject to the same inconveniences, those who come in carriages and those who come on foot, both men and women. [I-3] Oftentimes have I slept in these inns when the room has been full of the kind of persons mentioned. The motley group, while a three-cornered lamp, similar to those seen in old pictures, was suspended in the middle from the ceiling, reminded me sometimes of companies of pilgrims, and sometimes of hordes of banditti.

The situation of Dresden is singularly pleasing. It is built on the Elbe, which, from its windings, disappears both above and below the town; and it flows so smoothly as to resemble a lake more than a river. On the north side there is a ridge of sand hills, which have all been planted, within these few years, with pines, or some shrubs, and in many places with vines. These improvements were, in general, effected by the late Earl of Findlater, who bought some property here, or by the late minister, Count Marcolini. On the south side of the town there is also another ridge of gentle hills, which, extending both above and below it to the Elbe, and there apparently joining the opposite sand hills, shut up Dresden in a long oval vale. The mountains of Bohemia are seen at a distance; a great variety of walks, public gardens, beautiful scenery, and a well-cultivated neighbourhood, leave nothing in point of situation to be desired. The two parts of the town, situated on the opposite sides of the Elbe, are united by a long bridge, over which the people all pass on one [I-4] side, and repass on the other. There are very few good buildings in Dresden; the house appropriated to the meeting of the States, in the Pirna Street, or Parliament house, a little palace in the great garden, some distance out of the town, which was uninhabited, and falling to ruins, the Catholic Chapel, and the Japanese Palace, which is now the public library, were all that gave me any pleasure, or seemed worthy of notice. The gallery of paintings, the academy of arts, the treasury, or place where the jewels are kept, with the other curiosities, are too well known to permit me to say anything new of them, and I shall therefore content myself with merely noticing such little customs as I observed peculiar to the people.

A public library, which is open every day except Sundays and holidays, is hardly a peculiarity, for such libraries exist in most of the capitals of Germany, but it deserves mentioning, as a very useful thing. Any books it contains are given on being asked for; and there is a small well warmed room to sit in to read. A recommendation to the librarian, or a respectable citizen answering for a stranger, procures him the further advantage of taking books home with him. All the respectable inhabitants have the same privilege; few of them, therefore, frequented the library, but the number of their servants who came daily for books shewed that they were in the habit [I-5] of reading. The sovereigns have, by other means, such as establishing schools of all kinds, provided for the education of the people; and if they are not learned, ingenious, skilful, and energetic, it is not for want of the means of school instruction. Dresden, however, abounds with learned and clever men, with societies of poets and poetesses, among whom the ancient German custom of recitation is a favourite amusement, and with artists of all descriptions, who, without being greatly distinguished, pass their lives in the pursuits of science, or in the enjoyments of a cultivated taste.

The progress of the people in political knowledge, and the interest they take in political matters, is in some measure shown by there being in the town two different places where both French and English newspapers, with most of the German political and scientific journals of the day, are found. One of these is a club. It unites conveniences for playing billiards and other games, with books and newspapers, and to visit it a stranger must be introduced, but this is easily accomplished, through the English envoy, or some acquaintance. The other is a speculation, a complete cabinet literaire, such as are found in Paris and in other cities of France, to which people subscribe for a sitting, for a month, or for a year. The former of these places was much frequented, the latter hardly enough to pay the expences. The [I-6] Times, the Morning Chronicle, and the Courier, might be read here, and were a good deal read by the inhabitants; and as the Edinburgh Review was to be had at the royal library, an Englishman could keep in Dresden on a level with the course of events, both literary and political, in his own country. English and French newspapers, and periodical works, are now found in most of the large cities of Germany, and are much read by the Germans, which shows how much the communication between the nations of Europe is improved, how much the people of one country now feel interested in the political events of every other, and that there is some approximation making, by a rapid interchange of knowledge and sentiment, and opinion, to abolish all that is hateful and odious in national distinctions. The philosopher rejoices at this, but it takes much from the interest of travels; and the inhabitants of Europe can now be better known to each other through the rapid medium of the post and newspapers, than through the more expensive, and perhaps less interesting, means of travellers.

The inhabitants of Dresden are very fond of amusements, and much of their time is passed in walking to public gardens, in listening to music while they sip their coffee, in playing billiards, chess, and cards, and in conversation. The men all smoke, and the women all knit, in public places; [I-7] and the latter are so accustomed to the fumes of tobacco, that they seem to think them not an inconvenience. They often remained in crowded rooms, from which the smoke obliged me to retire. A pipe or a segar forms part of a German; and a most elegant-dressed young man, while he is making his best bow to his mistress, puts the burning tobacco under her nose, and lets her inhale at once flattery and smoke.

A great amusement of the citizens was shooting at the popinjay. A large pole, like the Maypoles of England, stands in the neighbourhood of most of the places of public entertainment. It is fixed in a sort of box, like the mast of a small vessel, so that it can be let down till it is horizontal, and elevated without much trouble. At the top a thing is placed resembling the Austrian eagle, but resplendent with feathers and gold. Those marksmen are considered the most skilful who shoot the head off. A cross-bow, but fashioned like a musket, is employed to shoot with; and it is loaded with a small iron bolt, by a person hired for the purpose of loading it, who is, in general, the owner of the cross-bows. The citizens continue to smoke their pipes, ask is it my turn, talk over their shots, and when the turn comes to any one, he lays the ready-loaded cross-bow on a bar of wood, about forty yards distant from the pole, and tries to hit the wooden bird. He [I-8] gives himself no other trouble; a boy looks after the bolts as they fall, and brings them back. It is an amusement that demands no labour and no thought; it allows of the continued enjoyment of smoking, and furnishes materials for interminable talk. This is a specimen of the manner in which the Germans shun active exertions. An amusement that requires some more exertion is nine-pins, which is also very common; but this admits of continued smoking, and demands no other labour but bowling. Dancing is the only amusement of the people that requires bodily exertion; and from their manner of dancing, which is rather slow, even this does not require much. Waltzing probably requires more.

One of the things that most early and most constantly attracted my curiosity in Dresden, was the custom of young lads singing psalms on Sundays and feast days about the town. Pious men have bequeathed funds to give a number of boys, who are, at the same time, choristers at the different churches, a cocked hat, a black scarf, and a suit of clothes, on condition of their entertaining the inhabitants with sacred music. Bands of ten or a dozen, with one for a leader, each dressed in black, with a cocked hat and a scarf, march slowly about the town, and, stopping at every second or third house, sing a psalm. I am myself too much averse to actions done from improper, [I-9] or I may call them false motives, not to find this custom rather ridiculous. The proper motive why men should sing or pray, is a correspondent state of mind, but this was singing for hire,—in fact, a sort of mockery of worship. With this small abatement, of pleasure from not liking the reason of the thing, I found this singing very agreeable. The shrill, clear voices of the youngsters, sounding, in a clear frosty morning, through the streets, though they could not be compared with the perfect music of the Royal Catholic Chapel, had something in them of simplicity that pleased my untutored ears nearly so well as the multiplied tones and warblings of the whole royal orchestra.

During my residence in Dresden, the return of the hundredth year of the Reformation was celebrated. The festival lasted three days. The churches were all hung, according to the taste of the clergymen, with flowers made into wreaths, festoons, and crowns. Orange trees were borrowed from the royal nurseries, and various shrubs and leafy ornaments were placed in the-churches, so as to give them a very gay and pleasing appearance. Religious worship, with appropriate psalms and hymns, took place on each of the days while the churches were thus ornamented, but the crowd was always so great, it was nearly impossible to get in. I unfortunately heard nothing, for even the very porches [I-10] were full. At the end of three days, a great number of the singers, accompanied by persons carrying torches, and pictures of Luther, with banners, on which various mottos were inscribed, and followed by a great multitude, paraded through the streets of the town, and came at length to the Old Market, a large clear space, surrounded by houses. Here all the multitude could assemble; and here, while the singers formed a circle, and continued singing, all the torches were thrown together, and made a splendid bonfire. The crowd, the houses, the singers, were all distinctly seen by the glare, and there appeared to be nothing wanted but that the whole multitude should have sung so well as these young men, to have made it a most imposing spectacle. In this point it failed. Nothing can equal or compensate the enthusiasm,—the heart swelling effects of a multitude of voices; and if this ceremony were intended to fix any thing eternally on the people, they should themselves have been previously instructed to join in it. But it was supposed the people could not sing so well as the choristers, and the mighty effect of their voices was sacrificed to a little scientific music. By the last glare of the bonfire the last psalm was sung, and the people all retired quietly to their homes. There were no great preparations on the part of the police, and yet there was no quarrel nor disturbance.

[I-11]

The same epoch was celebrated by similar festivals all over Germany, which argues, among the generality of the people, no indifference for religion. Medals also, and pictures of Luther, with the other reformers, were exposed for sale, and great numbers of them were bought and worn. Some of the medals were of silver for the rich, and of baser metals for the poor, so that all might be supplied. Luther and the reformers can only be considered as men who propagated in the world a number of moral and useful truths. So have the Bacons, the Newtons, and Lockes; and, while we celebrate the birth-day of Mr Pitt and Mr Fox, when it is perhaps impossible to ascertain any one benefit they conferred on society, we suffer those who have instructed us, and rescued us from error, to pass unhonoured; and Luther is probably only commemorated from his being a sort of leader to a large body of men whose interest it is that his tenets should be perpetuated and obeyed.

At the latter end of October, when this festival was celebrating, festivals of other kinds were common in Germany. On the eighteenth of this month, the anniversary of the battle of Leipsic, the students of the different universities of the whole of Saxony, in all about one thousand, assembled at the Wartburg, which had once long been the refuge of Luther, and there they burnt, in solemn procession, several emblems of some things they [I-12] disliked, such as the tail worn by the Hessian soldiers, the false breasts of the Prussians, an Austrian corporal’s stick, the article of the congress of Vienna, which decreed the partition of Saxony, and some books, among which was the History of the Germans, by Kotzebue. They heard speeches from some of their leaders, are said to have made vows to die for the freedom of Germany, and to have burnt the hats which they had waved as they made these vows, that they might never again serve any ignoble purpose. They were accompanied by a great many spectators, who participated in their enthusiasm; and thus a very general spirit was excited for what is supposed to be the freedom of Germany. At Dresden this event was the subject of much conversation, and there were few persons who did not express great joy at the conduct of the students, and great hope of future benefits from them. Much controversy arose. Some professors were censured for the part they took in this procession; and the whole excited a vast deal of interest throughout Germany.

The inhabitants of Leipsic commemorated the same day in a different manner. They marched to the field of battle in great numbers, and there, forming a ring, kneeled down, and celebrated with prayers the victory that had delivered Germany, though it divided their country. Whatever the monarch of Saxony might [I-13] be, the people were strongly opposed to Buonaparte and the French; they were animated by true German principles; and, unless nations are to be considered as the property of sovereigns, it was they, and not their monarch, who ought to have been thought of at the congress of Vienna; and they ought in justice, so well as in mercy, to have been spared that pain many of them expressed at the partition of their country.

Another procession, which deserves to be mentioned, was the funeral of a young lady. It was attended and followed like a funeral in England; a great number of people were, however, present, and amongst them, all the servants of the family. She was the daughter of a respectable innkeeper, and had enough of celebrity, and was enough respected, to bring a crowd together. The hearse was little more than wheels, and an appropriate place for the coffin to rest on, over which a handsome pall was thrown. The burying-ground was out of the town, near the Elbe, and the soil so sandy, that the grave was boarded up to keep it from filling before the corpse was deposited. Nothing worthy of mentioning happened till the moment of interment, when the lid of the coffin, which had never been screwed down, was lifted off, and the body, the colours just beginning to fade, was shewn to the surrounding spectators. She was in the stage,

[I-14]

“Before decay’s effacing fingers

Have swept the lines where beauty lingers.”

And

“Hers was the loveliness of death,

That parts not quite with parting breath;”

and neatly dressed and ornamented with flowers, she looked but as in a sweet undreaming bridal sleep. Every body had before wept, but at this moment tears gushed from the eyes of all the spectators; the women and girls who were present all sobbed as if she had been their dearest relative; the servants all wept bitterly, and there was no spectator who was not affected. These expressions of grief and agony continued till the coffin was fastened, and the earth covered it for ever. Many of the younger part of the females present exclaimed, Oh, why am I not also dead? why can I not be buried? I have frequently heard young women utter similar expressions when they were melancholy, which, with them, was not unfrequently the case. In the spring of life, when their hearts should be open to unknown but hoped enjoyments, and to all the charms of nature, they frequently talked of the grave, and said there was nothing they wished for so much as death. They oftentimes sang a well known German song, called the Song of the Grave, Das Lied des Grabes, descriptive of the peace to be found there, and rarely without sighing as they repeated the last lines, [I-15] “That was the only door through which the unhappy went to rest.”

This trait of sympathy may, however, be set off by the following: I one day entered a room belonging to a tailor I employed, where one of his children was lying, in the arms of a most unseemly death. Its limbs were ulcerated, it was half naked, flies buzzed about it, its throat was convulsed, and it looked shocking and disgusting. Yet its mother received me with smiles, and followed me out of the room with common unmeaning smiles, spoke to me of the weather and some other trifles, and when I pointed to the child, said, Yes, it was dying, in the same manner, and with the same tones, she had spoken to me of the weather. The father continued at his work, and seemed to have little other feeling but pleasure the child was to be taken away. This indifference is disgusting, but it is probably better than the overwrought sensibility which admits for a time of no consolation for irremediable, and yet common calamities. A person of my acquaintance, who had written works on botany and mathematics, and was considered rather a clever man, spoke to me one day of his marriage, and lamented it only because a wife cost him money, and he regretted his single state only as a cheaper one. The connection with women is so easy to be had, and so easy put off in this country, that no person appears to regard it as the great source of all the [I-16] better affections, and of an attachment to home. Marriage is spoken of as a matter to be decided solely by its money advantages.

The following little incident may also be mentioned as illustrative of character. Near Dresden, and below the bridge, there was one of those floating mills lying on the Elbe, which are common on many of the rivers of Germany and France. They generally consist of one large flat boat, or of two boats fastened together, and on them a house is built, which contains the machinery for grinding. They are moored in the rivers, and the current gives motion to the water wheel, the axis of which is in the boats. This one on the Elbe was carried away from its station by a large boat loaded with stones running foul of it. Every person near ran to give assistance; some brought ropes, and some boats, and while nothing was neglected that could assist in stopping it, there was no noise, and very little unnecessary bustle. The only exclamations noticed were, that the owner sometimes said, It is bad for me. There was a great deal of difficulty in stopping so large a machine; the people on board threw out huge stones and anchors, but they were not heavy enough to hold it against the power of the stream; at length, when it had floated nearly a mile, a rope was conveyed to it from the shore, and it was stopped. This was certainly an event calculated to excite curiosity, and would, in many [I-17] places, have produced much bustle and confusion. The Germans prevent these by thinking and regularity, and, while they possibly do more than some of their noisy screaming neighbours, they are sometimes thought stupid and dull from their possessing the virtue of self-command.

Brides in Germany carry with them to the house of their husband, what is called “der Brautschmuck,” which consists in clothes, fine linen, and jewels, proportionate to the wealth of the parents. On one of the princesses of Saxony being married to the son of the Grand Duke of Tuscany, all the linen clothes and ornaments, even to a chemise and a ring, which she was to take with her, were spread, before she went away, in the chambers of the palace for public inspection. The crowd to see the adornments of the royal bride was excessive, the centinels could scarcely keep the people back, and no conversation was heard amongst the women for several days but on the fineness of the linen, and on the beauty of the dresses and ornaments.

In Dresden, so well as in other parts of Germany, Christian names are common, which frequently recall those days of English fanaticism, when Praise God, and Hold-fast-the-Faith, were the baptismal names of our ancestors. The Germans are undoubtedly too much accustomed to these to remark them as peculiar, but a stranger smiles [I-18] as he reads Gott-lob, Gott-fried, Gott-furcht, Gott-lieb, and many other such combinations, expressing love God, fear God, praise God, God peace, &c. &c.

It might be considered as unpardonable if I were to take my leave of Dresden without mentioning, that on a hill on the south side of the town, about three quarters of a mile distant from it, is the place where General Moreau was standing when he was wounded, and that on this spot a small monument has been erected to his memory. It is merely a square block of granite, on which some instruments and ornaments of war, sculptured in stone, are placed, and it bears, if my memory is correct, the simple inscription, To the Memory of General Moreau. Zum Andenken General Moreaus. A few trees are planted round it, and the spot commands a very good view of the town.

In consequence of the Earl of Findlater having given the property, which I have before mentioned he had improved, to a German, who is known in Dresden by the name of Secretary, which title he derived from his services to the Earl, it is now converted into a place of public entertainment; and, from its commanding a most beautiful view of the Elbe, it is a very fashionable one, and is much frequented. It still bears the name of Findlater, and I notice the circumstance, to remark the curious coincidence of a British nobleman giving his name to a German tavern.

[I-19]

The following is a brief account of the present extent of Saxony, its form of government, and other little statistical notices, chiefly taken from the work of Dr George Hassel.

Its extent is 1352 square miles; it contains 1,232,644 inhabitants. It has preserved most of its manufacturing districts, and the richest of its mines, but it now produces very little corn, and contains no salt. It is divided into the following circles: 1. Of Meissen, containing 300 square miles, 297,945 inhabitants. 2. Of Leipsic, 276 square miles, 206,917 inhabitants. 3. Of Erzegeberge, 410 square miles, 459,264 inhabitants. 4. Of Voigtland, 132 square miles, and 88,639 inhabitants. A small part of Merseburg and Naumburg, 14 square miles, and 10,000 inhabitants. A part of Upper Lusatia, 220 square miles, and 169,879 inhabitants. The monarch is Catholic, the greater number of the inhabitants are Protestants, following the confession of Augsburgh, but other religions are fully tolerated. Jews, however, are tolerated only in Dresden and Leipsic, and have not the rights of citizenship. The difference between the ständes, or different classes of society, is strongly marked, and they consist in great nobility, in small nobility, in learned men, in citizens, and in peasants, who are yet in Upper Lusatia in a state of servitude.

The revenues are derived from domains, under [I-20] which term are comprehended several estates—from regalia, such as mines, forests, tolls, the post, &c., and from several taxes, the principal of which, however, is a land-tax. The amount of the whole does not now exceed from eight to ten millions of florins, or L. 1,000,000 Sterling. The debt amounts to 50,000,000 florins, or between L. 5,000,000 and L. 6,000,000 Sterling. The taxes are unequally levied, the greater and small nobility being almost totally exempted. The army may amount to 18,000 men.

The monarch is bound by law not to alter the religion of the people. He must call on the states for their advice when he wants to levy new taxes, or to make new laws. The domains and regalia are not all in the hands of the monarch, many still belong to the great nobility. Some of these, as the House of Shönburg, have the right to tax their vassals, paying a third of the tax to the crown, and this house also possesses the power of remitting all punishments less than death. With these exceptions, and if followed up they comprise a large portion of the power of the state, this monarch has, however, all the remainder of it in his own hands. The different provinces, or circles, have different constitutions and privileges, which yet actually exist, though they are abolished in name. The great division is in united and not united provinces. Out of the ständes or different classes [I-21] of the united provinces, the general assembly of the states for the kingdom is collected. The persons composing the states are distinguished into those who directly, and those who indirectly, form them. The first are divided into four circles, those of Meissen, of Leipsic, of Erzegeberge, and of the Voigtland.

The different classes living in these circles, who directly form the states, have a personal right to appear at the assembly of the states, while those who indirectly form them, the prebends of Meissen, and the university of Leipsic, have this right by virtue of their office. All the ständes of these provinces and circles, with the clerical establishments, are now united into a General Assembly of States for the whole of Saxony. The king has the power of calling them together when and where he will; generally he calls them together every sixth year. This assembly is divided into three classes; the first is composed of the clergy, and the great nobility; the second of the small nobility, Rittershaft; and the third of deputies from cities. The second class, or Rittershaft, are possessors of noble properties, and they are only permitted to attend personally when their forefathers have been enrolled in the College of Heralds for eight generations. Among that part of this class of the nobility who do not boast of eight ancestors, there are other distinctions. [I-22] Some hold their property independent of the jurisdiction of the local magistrate, and subject only to the jurisdiction of the Hofgericht; this property is called Schriftsässigen Güter, —the property of the others is subject to the jurisdiction of the local magistrates; this is Amtsässigen Güter. The former, the possessors of Schriftsässigen Güter, may appear personally; the latter, the possessors of Amtsässigen Güter, must elect deputies from the class which boasts eight known generations of ancestors. Among the holders of those noble properties, which are independent of local jurisdiction, Schriftsässigen Güter, there is yet a distinction into old and new. The latter may appear personally at the assembly, but they receive no diet money. This second class of the states, the Rittershaft, appoints, from out of the whole body, a small and a large committee, whose resolutions may be set aside or confirmed by the whole, but who, in general, manage the whole business for the class. These two committees, and the rest of the small nobility, are called the three colleges of the assembled smaller nobility. The deputies of the cities, who are the third class, have, in like manner, their small and large committees.

The first class makes representations for itself, and deliberates for itself on the royal propositions, so far as they concern their own interest only. The nobles of this class form a power almost independent of the monarch. The clergy and the university of [I-23] Leipsic, who form part of the first class, are dependant on the crown. The other classes, in like manner, deliberate apart, and when each of them has come to a decision, they confer together, and make a resolution in common. These resolutions, with the king’s consent, become laws, though they do not affect the first class, and are published under the name of the Land Tags-abschied. So far as I have been able to comprehend the constitution of this assembly, it appears little capable of transacting business; and, though it was sitting when I was at Dresden, I heard of nothing amongst the people but expressions of impatience that it might soon separate, as it cost the country a considerable sum, most of the members being paid. It is the ancient parliament of the land, and has become a burthen, because it has never been reformed.

There are two distinct codes of laws in Saxony. The first is composed of various provincial laws, and much of it is taken from the famous Sachsen-spiegel. The second is the code of Augustus of Saxony. Recourse is also had to the Roman and the Canon law to explain the others, and each particular province has laws that are proper to it alone; the laws are uncertain, the processes long and costly, and it remains with the advocates to let them go to a conclusion when they please.

The different departments of the executive government are administered by different ministers, as [I-24] in other European countries. For the administration of justice, there are the following tribunals: The Court of Appeals is the highest court, and, in cases of dispute relative to the property of the crown, this decides even on the rights of the sovereign. It is composed of one president, one vice-president, six noble counsellors, and twelve counsellors not noble, who are the judges. The Oberhofgericht at Leipsic is a court for particular persons, generally, I believe, for nobles. The Schoppenstuhl, which is composed of some of the members of the faculty of jurisprudence at Leipsic, and the whole of that faculty, form separate courts of appeal. The Berg Schoppenstuhl at Freyberg is the court for the miners, and all that relates to them, and at Bautzen is a court for Upper Lusatia. In each province there is a sort of local government, to whom the police and smaller jurisdictions are committed.

Saxony boasts one university, at Leipsic, royal schools at Meissen, Wurzen, and Grimma, with several lyceums, town schools, and village schools. There is an academy of arts at Dresden, and regular schools at Freyberg, for the instruction of miners. The whole of the education is under the direction of the chief consistorium; but the manner in which it is extended amongst the people will be better explained in the chapter on Education.

The spirit of every government, directed by one [I-25] or a few persons, and not by the great mass of the society, must always depend on the dispositions of the ruling individual; and the aged sovereign of Saxony has been, through a long life, a mild and a quiet king. Hence, with his government few people are discontented, and, in fact, every body whom I spoke with praised and pitied him very much.

The same circumstance has a great effect on the manners and morals of a whole people. And the decencies, the regularity, of the present court, even if they should be somewhat hypocritical, while they contrast finely with the libertinism of a former period, are tending to restore to the Saxons that regard for decency of which the voluptuous court of Augustus must have partially deprived them. The brutality of this man, which seems to have been all that could outrage morality in the unrestrained indulgence of strong passions, is often dignified by the name of brilliant fetes; and the giants’ hall is pointed out in the palace at Dresden, as the place where they were chiefly given, and the cup is still preserved at Moritzburg, a hunting castle at a little distance from Dresden, out of which he drank large quantities of wine to the health of his beautiful countess, and to the destruction of his own. Surely to denominate the lusts of this man brilliant is a misnomer; it, is, indeed, an untruth which [I-26] men are obliged to tell, in order to justify to themselves the weakness of reverencing and honouring such persons. The value of truth never appears so great as when it is applied to the deeds of men, and we shall have put on the three league boots of moral improvement, when we have learnt to give the actions of monarchs their right names. The brilliant fetes, as they are called, of Augustus of Saxony, ought to be named bacchanalian carousals, that would have disgraced a vulgar trooper, and that destroy the vigour both of body and mind.

I mixed so much with the inhabitants of Dresden as my imperfect knowledge of the language of the country, and other circumstances, allowed. The kindness and gentleness of the people pleased me. The city contains many amusements, and has many charms. At the moment I left it, on the morning of the 23d of December, it snowed, and the weather was cold, and thick; nothing was to be seen, either behind as a remembrance, or before to cheer me as a hope; the gloom added to my regret. I was scarcely out of the town before every object but the trees by the road side were hid from my view, and I felt perfectly alone. Regret was in some measure augmented by the approaching festivities, from which I was running away, when people were collecting in the town from all the neighbourhood to celebrate them. All my acquaintance exclaimed, [I-27] What, going before the festival? where will you celebrate it, then? A stranger, I replied, could have no festivals; they demand a union of friends and relations, of the endearments of love and of home, and the wanderer, the sojourner of a moment, may have a thousand wild and tumultuous pleasures in the endless variety he sees; his every day may be a day of enjoyment, but while he wanders, he can have no festivals with friends. Christmas is here, as in other countries, a family festival, occasioned by a religious ceremony; relations and friends meet and are happy in each other’s company, the time is passed in merriment and gladness, and the joy is attributed to religion. Such feelings, and such, perhaps, mistaken expressions for them, are common to all people. There are other feelings, different at different periods of life, which it is curious to see spread themselves over a stranger. The elderly people ask him if his parents are yet living, the middle aged if he is married, and the young, what his beloved thinks of his absence. But the most general questions, so general, indeed, as the appetites and desires which dictate them, are always of the prices of commodities, of the cheapness or dearness of food and clothes.

Despondency seldom lasts long when any thing is to be performed, and the good wishes of my acquaintance, as I remembered them, served to lighten my regret. My reveries were soon disturbed, [I-28] and my reflections driven into another channel, by the multiplied greetings I received from the peasants, men and women, chiefly women, however, who were carrying in baskets on their backs, or wheeling in barrows, the produce of their little gardens or labours, to market. With each of these I exchanged a courteous good morning, and the momentary disposition of the person saluting me might be guessed from the salutation. Some were light of heart. They had possibly received good Christmas gifts, or had good ones to give. They did not feel their loads, and their greeting was rapid and cheerfully given,—danced out as it were; others seemed to feel their load too heavy, and so much occupied by it as hardly to have time to say good morning; others had not yet shaken off the drowsiness of night, and, half asleep, grumbled out their salutation; others, and these were the greatest number, seemed to think of nothing but how softly they could say good morning, in order to convince you of that kindness which is so general a disposition of the German women. If the reader have lolled all his life in a silk-lined coach, or always lived in the parlours or saloons of polished society,—if he have never been solitary in the world—he will be unable to appreciate the pleasure derived from this passing salutation of peasant women. To me it gave animation, and seemed, when combined with the good wishes for fine weather [I-29] and pleasant journey, which yet sounded in my ears, to be paramount to an influence on the seasons. Though they could not make the snow cease to fall, the heavens bright, or the wind less piercing, yet they gave an elasticity of thought which made the snow and the cold disregarded, and I mused, with great pleasure, over a variety of circumstances, as I splashed along in the dirt, without taking “heed to my steps.” As I walked farther from the town, I ceased to meet any more women. It was yet dark, and I was left to my own reflections. They were not unpleasant. I had been told in Dresden I was always finding out the advantages of whatever happened; that I was a Candid. The thought did not displease me, and, to justify my conduct, I sought now for the advantages of candidism. It makes men content with the evils which they cannot remedy, while it encourages no supine submission to them. I thought I did not walk so well as formerly, and began to reflect I was growing old, and candidism made me find the advantages of age. Hitherto thought had been pleasing to me; I had a stock of materials for constant reflection, and there was no reason to believe, that, as vigour of limb decayed, vigour of thought might not remain. Former days recurred to me; I compared them with what I then enjoyed,—with what I might still hope to enjoy, and it appeared to me that youth had not been for me [I-30] the happiest period of existence. It is perhaps a mistake to suppose that it generally is. When it is past, life no longer boils and bubbles; it no longer sparkles nor ferments,—but it no longer sours, nor leaves, when the fermentation is over, a filthy scum. It is a disposition similar to candidism in all men, though perhaps disavowed, which makes them find out the advantages of things as they are, and which suggests to the bishop a load of benefits to the rest of mankind in the dominion of the church, and to the statesman in arbitrary rule.

After some time the sky became clear, and I could see the surrounding country. A ridge of sand-hills was on my right, and the Elbe on my left. Small parallel walls are built along the sides of the hills, to prevent the earth from being washed down, and to which the vines are at the same time trained. In the spaces between the walls they are tied to little stakes planted in the ground. At this season they were all cut close, and laid down under the ground, or covered with straw. Those against the houses were all carefully tied up in matting. At a distance of eight miles from Dresden, these hills extend down to the Elbe, and as there appears a continuation of them on the opposite side of the river, it looks as if the river had here forced its way between them. At this point also, the granite rocks which form the masses of these hills, whose surfaces are covered with sand, shew themselves [I-31] to the very top. It is said that some of the granite hills of Germany, particularly the Harz, are in a constant state of decomposition and destruction, and, probably, most of the high peaks of the world are gradually crumbling away. At least, I amused myself with thinking so, though I shall not defend my speculations against either the Huttonians or the Wernerians. They may not contain quite so much truth as theirs, but they were probably equally useful, for they afforded me a moment’s amusement, and the amount of the utility of all geological speculations is the amusement they afford to otherwise unemployed men.

Meissen was the first town I reached, and it lay on the opposite side of the Elbe. The bridge over the river here has rather a curious appearance, from having been built or repaired at three different times, and from uniting three different manners of turning arches. Some are turned after the common manner; there are wooden arches; and there are some, which are the most ancient, turned after the Gothic manner. Some parts of the bridge are of stone; some of brick; and some of wood. Meissen is the place where the Dresden china is manufactured, but it is not permitted to see the process without a particular permission from the superior inspector, which I did not seek. There is an exhibition-room, which everybody is allowed to enter. The old castle stands on a high projecting rock, that domineers [I-32] over the river and the town, and it encloses the cathedral within its walls. This is frequently the case, and it is a type of the moral union of church and state. Protection and favour are given for the obedience which the church inculcates. I dined at Meissen, and, on entering an inn, a barber offered his services. I declined them; they were accepted, however, by several persons, and he scattered his soap-suds about, shaving them in the same room where several people were dining.

The dialect of Meissen is celebrated as one of the purest of Germany, but, unfortunately, the purity does not extend to the people. On pursuing my journey, I had a peasant for a companion, who had been at Meissen, and was carrying home a finely painted red, yellow, and green distaff, and a spinning-wheel, as Christmas-presents for his wife. I hardly understood his language, it was so different from the German to which I had been accustomed, and therefore our conversation was very limited. He had some visits to pay in his way home, and we soon parted.

Soon afterwards I came to a close carriage, with the fore-wheel broke. It had been supported, and, while another wheel was putting on, which had occupied two hours, none of the persons in it had descended. A most elegant woman was standing up in it, and looking out of the window; she laughed and joked with [I-33] her companions within, whom I could not see. To her I paid my compliments of condolence, which she seemed very little to need. She was rather merry than sad. Two servants, who had been riding outside, had got down, but apparently only to light their pipes with greater ease. One of them was doing nothing but smoking, and the other, while he held fast hold of his pipe with one hand, was assisting the wheelwright to put on a new wheel with the other. German patience is a virtue, for it diminishes unavoidable evils.

A man I overtook told me, in very few words, that he was a deserter from the army; that he was tired of being a soldier at twopence-farthing per day, and that he was returning to his friends, who lived in what was at present the territories of Prussia; and there he hoped to escape Saxon punishment. I hardly knew how to reconcile the fear he expressed of being taken with his confession to a stranger, unless he had found, from experience, that every person not immediately interested in stopping him helped him to escape. His appearance had not suffered by his not having ate any thing that day; it was healthy, and might have been envied him by a glutton. He had looked at the lady in the broken carriage, which he had also seen, with the eyes of a man;—he called her a charming woman, eine charmante frau.