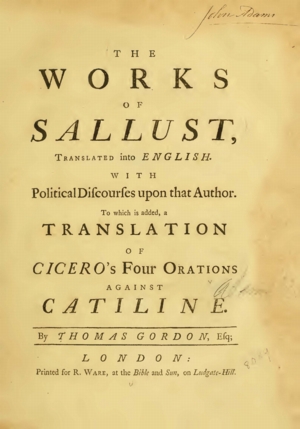

Thomas Gordon, The Works of Sallust, with Political Discourses upon that Author (1744)

|

|

| Thomas Gordon (c. 1691–1750) |

Source

Thomas Gordon, The Works of Sallust, Translated into English with Political Discourses upon that Author. To which is added, a Translation of Cicero’s Four Orations against Cataline (London: R. Ware, 1744).

See the facs. PDF of the entire book or just Gordon's Discourses.

Table of Contents

- TO His ROYAL HIGHNESS THE Duke of CUMBERLAND.

- INTRODUCTION.

- Political Discourses UPON SALLUST.

- DISCOURSE I. Of Faction and Parties.

- SECT. I. How easily the People are led into Faction, and kept in it, by their own Heat and Prejudices, and the Arts of their Leaders; how hard they are to be cured; and with what Partiality and Injustice each Side treats the other.

- SECT. II. How apt Parties are to err in the Choice of their Leaders. How little they regard Truth and Morality, when in Competition with Party. The terrible Consequences of all this; worthy Men decried and persecuted; worthless and wicked Men popular and preferred; Liberty oppressed and expiring.

- SECT. III. Party infers public Weakness: Its devilish Spirit, and sirange Blindness: What public Ruin it threatens: The People rarely interested in it; yet how eager and obstinate in it, and bewitched by it.

- DISCOURSE II. Of Patriots and Parricides.

- SECT. I. How Virtue and Vice, public Services, and public Crimes, may be said to bring their own Rewards.

- SECT. II. A suffering Patriot more happy than a successful Parricide: Public Oppressors always unhappy.

- SECT. III. Cautions against the Arts and Encroachments of Ambition. The Character of a Patriot, and that of a Parricide. How much it is the Duty, how much the Interest, of all Governors to be Patriots.

- SECT. IV. How apt the World is to be deceived with Glare and Outside, to admire prosperous Iniquity, and to slight Merit in Disgrace. Public Spirit the Duty of all Men. The Evils and Folly attending the Want of it.

- SECT. V. Considerations upon Two distinguished Romans, Cato and Cæsar; one in the Interest of his Country, the other in his own Interest: With the Fate and Issue of Cæsar’s Ambition, to himself and his Race.

- DISCOURSE III. Of the Resignation of SYLLA.

- DISCOURSE IV. Of the Pride and ill Conduct of the Patricians, after the Expulsion of Kings.

- SECT. I. The Roman Commonwealth unequally balanced. The Kingly Power, upon the Expulsion of Tarquin, engrossed, and imperiously exercised, by the Patricians. The ill Policy of this to Themselves, the Injustice of it to the Plebeians.

- SECT. II. The Plebeians, long oppressed, obtain a Remedy by Force; but a Remedy dangerous to the State.

- DISCOURSE V. Of the Institution and Power of the popular Tribunes.

- SECT. I. The blind Confidence of the People in the Tribunes: The Ambition, and violent Attempts, of those popular Leaders.

- SECT. II. Reflections on the plausible Professions, and dangerous Conduct, of the Gracchi. Public Reformations, how cautiously to be attempted.

- SECT. III. The boundless Power assumed by the Tribunes: With what Boldness and Iniquity they exercise it. The People still their Dupes.

- DISCOURSE VI. Of Public Corruption; particularly that of the Romans.

- SECT. I. The Interest of Virtue, and of the Public, every Man’s Interest.

- SECT. II. The fatal Tendency of public Corruption. The Public sometimes served by encouraging private Corruption. Other Means of Corruption, beside that of Money. Corruption sometimes practised by such who rail at it; in some Instances, by good Men, who hate it.

- SECT. III. Some Corruptions in the State to be borne, rather than removed by the Introduction of greater.

- SECT. IV. How hard to prevent Corruption, where the Means of Corruption are found.

- SECT. V. Venal Men, with what ill Grace they complain of any ill Conduct, or Corruption, in him who bought them: People once corrupted, how abandoned to all Corruption.

- SECT. VI. Amongst a corrupt People, the most debauched and desperate Leaders are the most popular.

- SECT. VII. When the People are thoroughly corrupt, all true Sense of Liberty is lost. Outrage and Debauchery then pass for Liberty, Defiance of Law for public Spirit, and Incendiaries for Patriots.

- SECT. VIII. The swift Progress of Corruption in the Roman Republic. Its final Triumph in the Dissolution of the State.

- DISCOURSE VII. Of the Corruption in the Roman Seats of Justice, and the Oppression in the Provinces.

- SECT. I. Of the extreme Difficulty in procuring Justice at Rome, against any considerable Criminal.

- SECT. II. The wonderful Guilt and Enormities of Verres in Sicily, confidently committed, from Assurance of Impunity. Cicero’s Character of the Judges: Their bold and constant Venality.

- SECT. III. The Virtue of the old Romans, in the Administration of Justice, and Government of Provinces. Their Posterity, and Successors, how unlike them. The wise and righteous Administration of Cicero, with that of the Provincial Governors in China.

- DISCOURSE VIII. Of Civil Wars.

- SECT. I. Who the first Authors of Civil War: What inslames it most, and why it is so hard to be checked.

- SECT. II. The chief Power in a Civil War, vested in the Generals, yet little reverenced by the Soldiers. Both Soldiers and People grow hardened and ungovernable.

- SECT. III. The shocking Corruption, and dissolute Manners, produced by Civil War; with the dreadful Barbarities and Devastations attending it.

- SECT. IV. The Soldiery, in a Civil War, only consider themselves: What low Instruments and Causes serve to begin and continue it.

- SECT. V. How hard to put an End to a Civil War. The Tendency of One, to produce More. How it sharpens the Spirits of Men, shocks the Civil Constitution, and produces Tyranny.

- SECT. VI. The Evils, and sudden Changes, brought by Civil War upon particular Families, and upon a Country in general; with the fierce Discontents, and Animosities, and ill Morals, which it entails.

- SECT. VII. A View of the affecting Horrors, and Calamities, produced by Civil War; taken from the History of Greece.

- DISCOURSE IX. To His Grace ARCHIBALD, Duke of Argyll. Of the Mutability of Government.

- SECT. I. Why Free Governments are more changeable in their Frame, than such as are Single and Arbitrary.

- SECT. II. The Danger to Free Government from popular Maxims, and popular Men; with the Advantages it furnishes against itself.

- SECT. III. The signal Power of Enthusiasm, and pious Imposture, in settling, changing, or perpetuating Government.

- SECT. IV. The surprising, despotic, but pacific Government, established by the Jesuits, by the Force of Imposture, in Paraguay.

- SECT. V. The inevitable Danger of trusting Ecclesiastical Persons with any Worldly Power, or any Share in Government.

- SECT. VI. The Profession of the Missionaries Abroad; how notoriously insincere, and contradictory to their Tenets and Practices at Home.

- SECT. VII. The Duration of Tyrannical single Governments, and the changeable Nature of such as are Popular and Free, further considered and illustrated.

- SECT. VIII. An Inquiry, Which is the most Equal and Perfect Government: Our own proved to be so.

- POSTSCRIPT.

- Endnotes

- DISCOURSE I. Of Faction and Parties.

- The Conspiracy of Cataline

- THE ORATIONS OF CICERO AGAINST CATILINE.

- THE WAR AGAINST JUGURTHA.

- THE SPEECH OF M. Æmilius Lepidus, the Consul, AGAINST SYLLA.

- THE SPEECH OF L. PHILIPPUS AGAINST LEPIDUS.

- POMPEY’s LETTER TO THE SENATE.

- THE ORATION OF LICINIUS, the Tribune: Addressed to the PEOPLE.

- THE LETTER WHICH Mithridates, King of Pontus, SENT TO Arsaces, King of Parthia.

- THE SPEECH OF Marcus Cotta, the Consul, TO THE PEOPLE.

- THE First Epistle of SALLUST TO CAIUS JULIUS CÆSAR: CONCERNING THE Regulation of the Commonwealth.

- THE Second Epistle of SALLUST TO CAIUS JULIUS CÆSAR: CONCERNING THE Regulation of the Commonwealth.

TO His ROYAL HIGHNESS THE Duke of CUMBERLAND.

SIR,

OBSERVATIONS upon Government, if they be just, cannot be unacceptable to a Great Subject so nearly related to Sovereignty. Whether the following be so, I humbly leave to Your Discernment; as I do to Your Good-nature, to forgive what was honestly designed, though it should be found weakly executed. All Minds truly Great are truly Humane: I am therefore sure, that though I cannot instruct Your Royal Highness, I shall not offend You.

As it is incumbent upon all Men, especially the Greatest, to support the best Government, Your Royal Highness has convinced all Men how well qualified You are to support Ours. That Ours is the best, I not only sincerely believe, but think demonstrable: Not that it is free from Faults; none ever was: Faults, I doubt, imply Decay, as Decay does a Tendency to perish. Bad Governments are scarce ever to be mended: Good Government, once overthrown, is generally overthrown for ever. What can be a greater Call to prevent such Overthrow, and whatever tends to produce it?

Your Royal Highness has acquired from many Languages, Antient and Modern, whatever becomes a Prince to have acquired: Such exact Care hath been taken of Your Education, such Your own Capacity, and such the Ability of those who were honoured with that important Trust. You can therefore readily perceive, whether my Reasoning, upon the following important Subjects, be useful and solid.

You have always become the high Rank in which You were born; You have adorned it, and shewn how eminently You are like to be, what all Men of distinguished Figure in a great State ought to be, but what too few are, an Ornament to it, and a Champion for it. Few, Sir, of Your high Rank have found at Your Years, fewer have embraced, fewer still have improved, an Opportunity of displaying military Talents, and earned such military Renown.

It hath been the Character of Your illustrious Ancestors, to be warlike: It hath been their Glory to engage young in War, and to defend Right against Violence. The King Your Father distinguished himself at Your Years, as You have done. The King Your Grandfather, in his Fifteenth Year, fought by the Side of the Prince his Father, at the Battle of Treves, where that brave Prince commanded the Confederate Cavalry, animated as well as commanded them, rallied them in Person, vanquished at their Head a Marshal of France, and routed a French Army. In that War that Prince lost many of his Family, and several Brothers, all brave Patriots like himself, exposing their Lives to rescue their common. Country from Usurpation.

That War was like This War. As Your Progenitors behaved, You have behaved; and the same Spirit which fired Them, fired You. Yet, whatever Courage then inspired You, I appeal, Sir, to Your own Heart, whether the chearful Persuasion of a righteous Cause, of relieving the Oppressed, and humbling insolent Oppressors, did not heighten as well as justify Your Ardour in the Day of Battle? This is the genuine Character, This the glorious Employment, of military Virtue: What Pity that it should ever be otherwise employed?

I congratulate You, Sir, upon Your engaging so young, in so just, so interesting a Cause. In Your first Battle You defended Justice, set invaded Nations free, crushed wanton Usurpers, and gained Glory without one Check from Your own Breast, without one Stain upon Your Fame. This was a Pursuit truly Heroic, and suitably crowned with Victory. It was a Cause of final Concernment to all Europe, a Cause worthy of Your princely Zeal, worthy of the Magnanimity of Your Royal Father, worthy of the Spirit with which He, with which You, animated by His Example, espoused it, and made it triumph. If ever Lives so important are to be exposed, it should be upon such an animating, such an alarming Occasion; To assert national Independence, to scatter Intruders, and break general Bondage.

The inglorious Cause of the War on one Side blazoned the Glory of the other, and consequently Your Glory; when all the Outrages of War were committed under Professions of Friendship; a War in Defiance of all the awful Appeals to God and Man, of private Conscience, and public Infamy; a War renewed just after Peace had been purchased at a great Price; a War pushed on, yet the Price of Peace still retained.

I question whether History ever recorded, or the World ever saw, such a daring Insult upon all public Faith and Shame; unless, perhaps, from the same Quarter, where the most solemn Engagements were never binding, Negotiations ever turned into Snares, and Treaties into Mockery.

From the same Quarter it is no Wonder to see Insincerity, and the most pernicious Morals, spread, with melancholy Success, over all Countries who sottishly derive their Modes and Maxims from thence. What can be a greater Source of ill Morals in all Shapes, than an open Contempt of all the Bonds that restrain, of all the Principles that awe, the human Soul? Surely, a People famous for Vanity and want of Truth, afford but a scandalous Pattern for Imitation: Their meanest Actions are Marvels; every Officer a Hero, every Prince more than Man, and their Monarchs Deities. Some of them, who never won a Laurel with their own Sword, have, by the inimitable Flattery of their Subjects, been crowned with more than ever graced the Head of Cæsar, or any of the antient Heroes. When, by Surprize, they had beaten their weaker Neighbours, and made some guilty Acquisitions, more by great Want of Faith, than even by great Armies; all their Depredations have been extolled and hallowed by a hireling Army of Panegyrists, as the Conquests of a Hero, nay, of a Deity.

A Hero without Heroism can only be created by Flatterers without Shame: A King void of Faith can pass for a Hero with none, but Sycophants void of Conscience. Praise not merited, but bought, rarely lives so long as the Buyer, even though he be constantly buying: If it be ingenious Praise, it will rather be the Portion of the Seller: At all Events, it will be for ever stained with the Reproach of being Sold.

I have heard of a Prince represented as sufficient upon Earth to do all that even the Divine Being could do there. The Monks and Poets scarce left Almighty God the Possession of his own Throne, with Ability to rule the Skies. They prophesied, or rather threatened, that their Grand Idol would, one Day, be at least his Coadjutor even Above.

After this, (and this was but One, of a Thousand such Excesses) no Strain of Flattery can be surprising, not even that of Divine Worship publicly paid to his Statue, erected with all the Pomp of Idolatry and holy Ceremonies, Genuflexion, and even devout Prostrations; the Courtiers, the Citizens, the Soldiers, solemnly attending, and awfully adoring this perishable Divinity. This Mockery of Omnipotence was so far from shocking Him whom it most ought to have shocked, that the foremost Idolater in the impious Worship paid to human Frailty was rewarded with a Profusion of Bounty and Honours. Such is the Intoxication of Flattery, when it is most incredible, and even blasphemous! The Title of Immortal was but a moderate Compliment, in Comparison with the rest, and very aukwardly claimed by such who always kept far from Danger.

Such Princes seem to have been insensible, that they were formed of the same Mould with other Men; that their Blood was of the same Colour; themselves liable to the same Infirmities; that with all their Power, however boasted and boundless, they could not prolong Life, much less vanquish Death; that it was their Duty, and best Glory, to shew Tenderness and Benignity to those, who, in the Grave, and beyond it, would be upon a Level with Them; that Flattery is not Fame; that a Throne is only so far glorious, as he who possesseth it acts with general Beneficence; that the most exalted Thrones have been often filled with such as were a Bane and Disgrace to human Nature; that Folly is contemptible, Iniquity detestable, even under the Blaze of a Crown.

Does not Your Royal Highness still find something very instructive, even from these offensive Characters, of Princes swoln to an enormous Size in their own Conceit, by the Poison of Flattery? Such Instances shew, what immoderate Pride may attend moderate Parts; how confidently a human Creature may claim Attributes more than human; that a vehement Appetite for Praise, is no Proof that Praise is due; that a warlike Spirit is not always necessary to do warlike Mischief; and that the World may be greatly disturbed by the meanest Characters in it; a melancholy Consideration, too apparent at most Times, never more than at this Time!

By what You have been doing, and by what You are going to do, Your Royal Highness has convinced the World, that You esteem Royal Birth, without a Display of Royal Qualities, no genuine Warrant for Fame. You know, that Virtue first made Men noble; that it is with Royalty as with Nobility (Royalty being only the most exalted Nobility); when it renounces its Foundress, it debases itself: That the Distinctions of High and Low are not produced from human Nature, but from the Nature of Society; and that the Protection and Defence of Society are the most amiable Grounds of Title and Elevation: That none but a useful and benevolent Character, can be a moral Character; that none but a moral Character, can be truly a great one: That even Courage, without Benevolence and Justice, is as great a Solecism, as Religion without Virtue.

To be brave, is a praise-worthy Character in a Prince; nor is a Prince without Resolution, fit for a princely Place: To be just and brave, is a glorious Character; glorious in a King, glorious in the Son of a King. This Island can boast such Characters, and from them the pleasing Hopes of what may be expected from the rest of the same Stock. Their greatest Danger, and consequently ours, is their being too brave.

It is no Pedantry to quote Latin to one who so well understands it. Non te fortem esse dicimus, sed querimur, was a just Complaint and Caution offered to our glorious King William. I hope his present Majesty, I hope Your Royal Highness, will not disregard the same Caution. That fine Genius, Dr. Thomas Burnet, thought it no Compliment to that great Hero, that he was brave; but complains of him as too brave, by exposing that precious Life, which endangered or secured the Lives of all, as it was itself secure, or in Danger.

Dr. Burnet knew the Value of that Heroic Prince; though All did not. The Malevolence of Party, which distressed his Reign, clouded his living Glory, but hath not been able to contaminate his Fame. Is not this, Sir, a pleasing Reflection, that Justice and Praise, if they do not meet, will, first or last, overtake, solid Merit; and false Merit, however exalted, will, sooner or later, be despised? The Memory of King William fares, as that of great and good Princes ought to fare: It lives in the Voice of Fame; whilst the Memory of despicable Men, great only in Rank and Vanity, however flattered, and even worshiped, in their Life-time, will be despicable, or lost.

I could mention another Instance of the Justice of Time to great and good Characters, but that it might too nearly affect Your Royal Highness: It is that of a great Princess deceased, whose Fame hath grown with Time, and still grows: The sure Sign of high Merit! They who spoke not well of her some Years ago, do it now: They who speak with Indifference of her now, will praise her some Years hence.

The worthless Dead, as they could not expect, neither can they bear Remembrance. True Worth gains by the Grave. The Good which they did, is remembred: The little and great Falsities, raised about them, are forgotten; personal Envy ceases; the Clamour of Party is heard no more: Justice is restored, Truth prevails, and that Virtue, which stands in no Man’s Way, is by all Men applauded.

After Death, Characters are better known. The Good stand the Test of Posterity. The Great and Virtuous continue to be loved and praised. The Great and Bad are hated and blasted. Nero and Messalina are Names of Reproach and Horror, at the End of Seventeen hundred Years: Scipio and Portia are Names still celebrated, at a greater Distance of Time. They themselves indeed feel neither Obloquy, nor Praise: But they will ever live in Record, and reap eternal Renown, or eternal Infamy. It cannot but be a Pleasure to the Public, to see what laudable Claims Your Royal Highness already has to the Favour of Posterity.

Great Heroes, when they prove just Rulers, are a matchless Blessing. Such were Aristides, Epaminondas, the two Scipio’s, with many other Antients. Such was Henry IV. of France: Such was our Edward III. Such our King William. Such Blessing is the more valuable, as it is exceeding rare. Few Heroes prove just Magistrates, and therefore are imperfect Heroes, whatever Custom and Flattery may call them: They generally as little regard the Rights as the Lives of Men. A late celebrated Prince in the North, as warlike a Spirit as ever alarmed or wasted the World, had small Tenderness for Magistracy and Laws, and as little Feeling for human Calamities. Cromwell had great Talents for Government: So had Cæsar. But they were Usurpers; and as the Laws were against Them, They were against the Laws. Demetrius Poliorcetes was a Hero, at least a complete Warrior; but had utter Contempt for the civil Tribunal, and regular Administration of Justice: He knew no Decision of Property, but by the Sword, and was a Soldier in the Seat of Judgment.

Your Royal Highness will own, that the most comprehensive, the most amiable Qualities of a Prince are Justice and Fortitude. Aristotle, I think, places the latter foremost in the Rank of moral Virtues; probably because it implies a Defence of the rest. People, therefore, under a King thus qualified, have reason to think themselves happy: It is a dangerous Symptom where they do not. The best Rulers do not escape popular Censure, however poorly founded. The Athenians reproached the virtuous Cymon for having bad Wine; as the Romans did the great Scipio Africanus for sleeping, having no other Fault to find with him: The Enemies of Pompey upbraided him, for using but one Finger in scratching his Head. Plutarch, who observes this, adds, that the People, growing tired with their old Rulers, often incline to worse, out of pure Wantonness, and from a Taste utterly depraved.

For myself, Sir, I sincerely believe, that as no Prince ever oppressed or wronged his Subjects, without suffering bitter Retribution in some Shape; I am equally persuaded, that no People ever proved ungrateful to a good Prince, without paying dear for it, and punishing themselves. I hope Your Royal Highness will never see Either Case tried; I am satisfied You will contribute to Neither, but (were there Occasion) always delight to prevent Both.

I have great Pleasure in subscribing myself, as I do, with very zealous and very profound Respect,

SIR,

Your most Dutiful,

Most Obedient, and

Most Humble Servant,

T. Gordon.

INTRODUCTION.

THE following Translation of Sallust was not the earliest Part of the following Work. Most of the Discourses were begun, several of them finished, before the Translation was attempted. They consist of such Observations as occurred to me from reading Sallust, and from the signal Pravity of those Times, of that People and Government; a licentious People, a crazy Government, and therefore terrible Times; a Government generally enfeebled by a loose Administration; sometimes severely attacked, when best administred; always labouring under some dangerous Disorder and Defect; for the most part hurt by Attempts to reform it; frequently oppressed by such who professed to support it; at last, overthrown by insidious Reformers: The boldest and most pernicious Schemes often best received, and the best Men least heard, in most Peril, generally undone, for opposing the worst. The virtuous Cato dragged, like a Criminal, from the Forum, for thwarting the pestilent Projects of Cæsar; Cicero, the Saviour of the State, banished, for punishing Criminals combined to destroy the State.

In discoursing upon Tacitus, I had affecting Subjects, the Rage, the Madness, the sanguinary Politics of the first Cæsars, with all the Horrors of Imperial Jealousy, and unbounded Will; one weak, or wicked Man, grinding, exhausting, and butchering the Roman World; himself, at last, naturally butchered, to make Way for a Rival; who, unwarned by his Fate, follows his Example, perishes like him, and leaves a Successor not wiser nor happier, living a Tyrant, and dying a Victim to Tyranny; the best Princes murdered for being so; Liberty extinct, Virtue persecuted, all Attempts to retrieve either, unpardonable and fatal.

The Subjects furnished by Sallust are equally interesting, and near as affecting; the mutual Rage and Iniquity of embittered Factions; the furious Struggles between the Nobles and Commons; both oppressing, both oppressed, in their turns, with equal Wantonness and Injustice; and the Consequences equally destructive to both: Prevailing Corruption in the State; shocking Venality in the Courts of Justice, Rapine in the Provinces, barefaced Iniquity in the Senate; Parricides prospering, Patriots perishing, Liberty prostituted and expiring; Conspiracies, Usurpation, and Wars, both Civil and Foreign.

The only two intire Pieces which remain of the Works of Sallust, are Catiline’s Conspiracy, and the Jugurthine War; the latter much earlier in Time, but the former first composed; both written with Spirit, and fine Style; but the Jugurthine War the most regular, the most connected, and the most masterly Performance.

Sallust had great Talents for History, and where he adheres to it, and pursues the Thread of it, does it with great Clearness and Ability; engages, leads, and pleases his Readers; but is apt to balk them by starting from his Subject; and his Digressions, however ingenious, are too declamatory; and much good Sense is blended with much Self-sufficiency. His Prefaces have remarkably this Turn: They are more eloquent than pertinent, full indeed of curious Speculations, of high Panegyrics upon Virtue, of keen Invectives against Folly and Vice, but replete with Compliments to himself, and the Importance of his own Character and Studies, to which these Prefaces seem Introductions, rather than to his History. In them he takes care to keep the Attention of his Readers as much upon himself as upon the Subject; and, in arraigning ill Rule, and ill Rulers, his public Zeal seems heightened by private Pique. He publishes his own Picture, and Discontents, before his Works; hurts himself with his Readers, by displaying not only the Vanity, but the Sourness and Resentment of the Writer; impairs Truth by Strokes of Ostentation and Satire, the Dignity of History by Invective, and the Impartiality of an Historian by personal Disgusts.

Whatever Faults the Government had, (and great ones they were, God knows!) it is likely that he would not have railed at it, had he been in it. He flatters the Usurper Cæsar as copiously, as he inveighs against the former free Administration; and, in accepting the Rule of a Province from that Usurper, made it appear; by his insatiable and infamous Administration in it, how much he had wanted such Preferment, how unfit he was for it, how unworthy of it. He plundered Numidia without Bowels; nor amongst all the corrupt, all the rapacious provincial Rulers ever sent from Rome, did the worst of them prove more rapacious and corrupt, than this Declaimer against corrupt Rulers. His Conduct in Numidia was so flagitious and black, that even his partial Patron Cæsar, the Promoter and Defender of guilty Magistrates, and of all guilty Men, could not support him: He was forced to retire, and lived in Voluptuousness and Disgrace, upon the infinite Spoils of his inhuman Magistracy. This makes the other public Charge probable, that he had formerly dishonoured the Quæstorship by the like unbounded Corruption and Venality, had been thence doomed to public Punishment, and seems never to have forgiven the State for inflicting it.

There are other Charges against him; but, as they were not of so public a Nature, I omit them. His Affectation of old Words and Phrases is but a small Charge, and he seldom incurs it. Language is always flowing, never sixes. Yet every Generation believe their own to be just then in its Perfection; nor, when it is fallen ever so low, will they perceive it, much less suffer it to be reduced to a better Standard. The Modes of Speaking, like other prevailing Modes, seem always best, and are always most pleasing to the Many. The Ear is no more infallible than the Eye. Whoever deviates from the Phrases and Pronunciation in Fashion, is thought as absurd as if he crossed the Fashion in his Dress. The English Language seems to me, to have come to Perfection in Queen Elizabeth’s Time: It hath since received some Improvements, as well as suffered some Decay; and is still in Danger of decaying further, chiefly by following the French Language, which is itself fallen, and its Spirit greatly sunk. The learned and judicious Monsieur Pasquier, in his Recherches de la France, complains of this Decay in his Time, One hundred and Fifty Years ago; not only that many good Words were difused, and worse introduced, but the same Words were altered for the worse, and lost their Force for Glibness. He makes the same Observations of the Italian Tongue. Monsieur Passerat, Professor of Rhetoric at Paris, an able Critic, acquits Sallust from the Imputation of reviving old Words, or rather commends him for it, upon the same Principles.

His Language, upon the Whole, is pleasing and pathetic, his Narration natural, his Speeches strong and persuasive, his Descriptions exact and beautiful, the Reflections curious and poignant, the Characters striking and just; his own, that of a noble and instructive Historian, a great Writer, not without great Faults in his Writings; I do not mean only his Flattery and Partiality to Cæsar; his Prejudices to Cicero are apparent and unpardonable. He speaks very sparingly of that great Man, by Right the Hero of his History: He treats him with the Contempt of a few civil Epithets, and says of him just what he must say, in order to explain the Progress and Issue of the Conspiracy. Though he is apt to go out of his Way, in order to display his own lively Talents in drawing Characters, he exercises none of them upon that of Cicero, where there was such a loud Call for it, so much Scope for the most brilliant Colours, and such a Crime in omitting them.

This is not only a Defect, but a Stain, in his History of the Conspiracy. He gives us an accurate Portraiture of Catiline, is copious in the Display of his Abilities, as well as of his Crimes; and, not content with declaring him a great Master of Eloquence, presents us two large Specimens of his great Power in Speaking. He gives us an artful and able Speech of Cæsar’s to save the Conspirators, without owning that Cæsar meant to save them, much less that he was one of them; nay, takes Pains to justify him, and afterwards draws a pompous and amiable Character of that dangerous and guilty Man. He makes no Attempt to draw that of Cicero, who, though well known to the Romans, was not better known than Cæsar. He illustrates the Character of Memmius, by an admirable Speech of Memmius, which yet he might have spared without laming the Story. But in recounting the Defeat of a most dreadful Conspiracy, by the Vigilance and divine Abilities of Cicero, he makes Cicero do nothing but what any plain sensible Magistrate, of common Integrity and Spirit, might have done. The Consul indeed encourages the Confederates of Catiline to betray Catiline: He takes the ordinary Precautions, is pressed with Difficulties, calls the Senate, and makes them a Speech, which Sallust owns to have been a vigorous and a seasonable one, but produces not a Sentence of it. It is true, he adds, that Cicero afterwards published it: And may we not suppose, that those of Cæsar and Cato were likewise published? The Argument and Substance of both were kept, as usual, in the Journals of the Senate.

This dry and narrow Treatment of Cicero is a Notable Failing in his History, and, considering the Talents of the Historian, a Malicious Failing.

It is the Part of an Historian, and his Duty, as to cover Traitors with Detestation, and Treason with Horror, so to throw all Lustre upon public Merit, and to brighten the Character of a public Saviour. Sallust sets Catiline in a fuller Light, than he does the illustrious and immortal Consul, who conquered Catiline, and all his formidable Train. Suppose Cæsar had been in Cicero’s Place, and done what Cicero did; how differently and splendidly would he have shone in the warm and brilliant Strains of his Friend and Admirer, the Historian! Sallust should at least have given us a Summary of Cicero’s first Speech to the Senate, where the Consul encounters Catiline with such Spirit. He ought to have made an Extract of the Consul’s other Speeches, where the Consul recounts the dark Doings of him and his Accomplices, with as much Clearness as Sallust does, and adds some material Circumstances, not found in Sallust.

Cicero’s Account of the Examination of the Conspirators before the Senate, in his third Oration, is as pertinent as any thing in Sallust, and more curious. So is his Detail of the several Characters and Ranks of Men engaged with the Conspirators, in his second Oration. So is his Summary of the Civil Disorders past, compared with the present Conspiracy: So is his Relation of the Proceedings of the Senate, with the high and unparallelled Honours there decreed to himself, but not once mentioned by Sallust: So is his Character of Catiline. Indeed these Orations against Catiline furnish such essential Lights to that tremendous Conspiracy, that, as soon as I had translated Sallust, I translated Them, on purpose to supply the Defects of Sallust.

The Historian should have told us, with what masterly Address the wise Consul managed both People and Senate, and with what different Strains he addressed to each. The Historian should have exhibited at large the fourth Oration, where the Orator so artfully sooths Cæsar, and so dexterously turns to his own Purpose the artful Reasoning of Cæsar. Not a Word of all this in Sallust; an Author so fond of repeating long Speeches, even some that suspend his Narration, and hinder historical Connection.

As the Mind of Man, engaged in an interesting Story, and earnestly pressing towards the Issue, is never to be diverted but by such Incidents and Characters as tend to produce it: Equal too is the Impatience of the Readers, when they find the Historian defective, or dry, in his Display of the principal Actors, and of the Parts which they act; when they perceive him loth to represent, or malevolent in representing, or omitting to represent, such Persons and Parts. Such a Discovery provokes the Reader, and depreciates the Writer.

In Sallust you see Catiline, you see Jugurtha, at full Length, their untameable Spirit, their superior Genius, their many Qualifications, their infinite Resources, their unwearied Application, their prevailing Address: You see the dreadful Probability of their Success, and the Proximity of Ruin to the State; you rejoice in its Escape, and in their just Doom. To other great Names he does the same copious Justice. Metellus, Marius, Sylla, are all represented in sine and full Light, and their Characters and Praise minutely and impartially set before the Reader. The Story and Sufferings of the unhappy Atherbal are affectingly told, particularly from his own Mouth, in that most moving Speech of his to the Senate, one of the sinest and most interesting in History.

But the glorious Conduct of Cicero, his high Courage, his Penetration, his wise Schemes, his Address and Temporizing, his various and prevailing Eloquence, are so far from being set in a glorious Light by Sallust, that all which Cicero does and says there, is no more than what might have been done and said by a very inferior Senator. He gives you Cicero for a Man of Sense, Experience, and Credit. But in him you behold not Cicero, the consummate Statesman, the inimitable Orator, the determined Patriot, nor any Traces of a sublime and superlative Genius.

So many unnatural Omissions, and the Prejudices of the Historian against the Orator, are probably the chief Cause why the History of Catiline’s Conspiracy is so loose and defective a Performance. There are many complete Things in it, Speeches, Characters, Recitals; but the History itself is not complete. Nor was it possible he could have composed it as he ought, without giving such a Brilliancy to the great Name, and unparallelled Services, of Cicero, as a prejudiced Pen could not give. It is a Performance certainly far inferior to the History of Jugurtha.

A fine Genius doubtless he had: It is by the Strength of this, that he hides, recommends, and even dignifies his Faults; and generally rouses and delights his Readers by the Sprightliness of his Thoughts and Phrases, even when he carries his Readers out of the Way.

I found it very difficult to translate him, though not so difficult as to translate Tacitus. Neither do I think him an Author equal to Tacitus, nor to possess the same Majesty and Depth. Besides, in Tacitus you find no Traces of Conceit, no Self-praise. All his Pomp is natural, the Effect of the Subject upon his Spirit, and of his Spirit upon his Pen. Sallust studies to be eloquent: He flourishes to please himself, and to make his Reader pleased with him, and seems to enjoy his own Performance. He was a fine Genius; Tacitus a great one.

Sallust, I own, is more in the general Taste, and has more Readers, than Tacitus, because he is more easily understood, and therefore in more Hands. He is a School-Book: Boys learn him together with the Latin Tongue; and, valuing themselves for understanding Him, they value Him as the first and best Historian. Tacitus is understood by very few; it is incredible by how few: Yet all pretend to judge of his Character, and, taking his Faults upon Trust, hand the trite Exceptions against him, with notable Confidence, from one to another. There is nothing more absurd than most of these Exceptions; as I have at large shewn in my Apology for him and his Writings(a): The greatest is, that he dives malignantly into the Hearts of Princes for malignant Strokes of Policy there. But the Instances which they give, confute the Charge; not only as such Instances are natural and probable, but mentioned by other Historians no-wise suspected of Refining, or want of Veracity.

The other Exceptions against him are equally ill-grounded, perhaps started by some sage Pedant, who did not understand him, then believed, and handed down by such as could not read him. All the Objections against him are new: He was highly admired by the great and learned Men, his Cotemporaries, who found great Excellencies in his Works, without any Flaws. Nor do I find, that he had any Censurers, as a Writer, for near Fifteen hundred Years. Are modern Critics likely to judge better of his Character or Language? Yet many such Critics there are, most of them superficial and misled. Even a false Critic, of any Reputation, is usually followed by Numbers, who deserve none.

In the Translation of Sallust, I have, throughout, used my usual Style, and hope it will not be found altogether unsuitable to the Style of Sallust. In that of Tacitus, I went into some Variations: And I believe there are few that understand Tacitus, but will own they were necessary: It is no Wonder, that such as understood him not, found fault with them. Though such Variations occur but here and there, chiefly in his Speeches and Reflections, and are nowise obscure to any intelligent Reader; they were by some confidently said to run through the Whole, and the English to be as obscure as the Latin. Such is the Truth and Candour to be found in vulgar Critics, of all Ranks, even when they can be confuted in every Bookseller’s Shop. To comply with the common Taste, I made many Alterations in the second Edition; and cased several Sentences, which were reckoned stiff. And this I did directly against the Opinion of the late Duke of Argyll, a most accomplished Judge, and of some other great Persons still amongst us, of equal Taste and Abilities, and, from their Knowlege of Men and Business, best qualified for understanding Tacitus: But the public Cry is sometimes to be humoured, even when it is ill-grounded.

In the present Translation, I have fully avoided all such Cause of Complaint. In conveying the Sense of Sallust, I do not pretend to tell all my Readers, learned or unlearned, that I have not sometimes mistaken it. I took all possible care to find it; and were I to take theirs, where they differ from me, I probably should find others, besides myself, to differ from them.

I doubt not but it is possible to find Ten Persons, all tolerable Judges, who would translate so many Sentences of Sallust, or any other Antient, Ten different Ways. Every Judge, good or bad, is apt to take himself for a competent Judge. I shall be nowise piqued against any Man for differing from me: I hope for the same reasonable Allowance and Treatment from all Men. As we are all liable to be mistaken, it is both indecent and unfair to insult over the Mistakes of one another; especially to insult falsly, when there may, perhaps, be no real Mistake, but only one raised by our own Self-sufficiency and Heat.

A Friend of mine, some Years ago, brought me a Weekly Paper, where I was treated with great Outrage, by an angry Man, for mistaking so egregiously (as He thought I did) a Passage in Tacitus. It is where Germanicus tells his mutinous Legions, that Cæsar had once reclaimed his seditious Army by a single Word, Quirites vocando: I translate it, by calling them Townsmen. ‘No, says the well-bred Fault-finder, This is not the Sense, and a School-Boy would have been whipped for so turning it. I, says he, would have translated it thus; He called them Romans, and all was quiet.’ Observe how confidently this blind Observer perverts Cæsar’s Words! It was not a Compliment, but a Rebuke: Quirites vocando; They were no longer Soldiers; he disowned them for such, declared them discharged, and called them what they now were, so many of the Populace, Townsmen, a Multitude.

The Fact and the Consent of Historians about it, of Dio, Plutarch, Suetonius, confirm this to be the Meaning of the Words; Quirites vocando, in other Words, solutos Militia, dismissed from the Service.—In Lucan’s Paraphrase it tuns

———Discedite Castris:

Tradite nostra viris, ignavi, signa, Quirites.

From these Words, and the whole Speech, may be seen, that, instead of soothing them, he treats them with sovereign Scorn and Indignation. Rowe translates these Lines thus:

For you, ye vulgar Herd, in Peace return:

My Ensigns shall by manly Hands be borne.

Lampridius, in the Life of Alexander Severus, explains the Word just as I have done. Severitatis autem tantæ fuit in milites, ut sæpe legiones integras exauctoravit, ex militibus Quirites appellans. ‘Such was his Severity in Discipline, that he often dismissed whole Legions; calling them (instead of Soldiers) Townsmen; Quirites appellans.’ The same choleric Writer asks, What Discoveries I had made about Tacitus? My Answer is, That I have discovered the Meaning of Tacitus; a Discovery which, it is plain, He had not made.

I should have taken no Notice of such vain Censure; but some of my Friends told me, that they heard it quoted in a Coffee-House (perhaps by the Author) with Approbation. It will serve too as an Example, what Confidence attends Ignorance; how prone People, especially coarse People, are to censure; what ridiculous and scurrilous Attacks an Author is liable to, for being in the Right; and with this View only I mention it.

I shall quote another Censure upon my Translation of Tacitus, a very general Censure. Tacitus says, in the Reign of Augustus, Tranquillæ res Romæ. I translate these Words, ‘In profound Tranquillity were Things at Rome.’ Is not that the Sense of the Words? Yes, say the Critics; but the Sentence is forced and transposed: It should have been, Things at Rome were in Tranquillity. The Truth is, either Way does; but the first Way is at least as common as the other amongst all our best Writers, and, in my Taste, is the best Way.

A Person of a learned Profession, who ought to be learned, for he lives by it, roundly asserted in Company, That I did not understand Tacitus. A Gentleman present, provoked at such an ungenerous Assertion, asked the Assertor, Whether he was sure, that he himself understood Tacitus? He added, That he had read both the Original and the Translation, and found such a Charge to be utterly unjust: Therefore, Sir, says he, I will send the Boy of the Coffee-House for a Tacitus, that you may convince us, that you do, or do not, understand him. The candid Critic left the Room, for fear it should come; but so Crest-fallen as to own, that he did not understand every Part of Tacitus. He did not stay to convince the Company, that he understood any Part of him.

I have carefully examined, and re-examined, every Sentence of Sallust, frequently revised the Whole, always compared it with the Original, and have had it under my Eye for many Years. There is surely great Difficulty in any such Undertaking. The Languages, the Times, and the Taste, are all so remote and different from ours, that it is next to impossible to convert antient Terms and Transactions into any modern Language, at least so to convert them, as to make them please equally with the Original; especially Works of Genius, where the Translator has not only the hard Task of conceiving and forming the same Images, of seeing them in the same Light, of animating them with the same Spirit, as his Author (a Tacitus, or a Horace) saw, formed, and conceived and animated them: He has another Task still as hard, that of finding equivalent Phrases to clothe, convey, and recommend them, in a Language of very different Idioms and Contexture, a patched Gothic Language, full of Particles and Monosyllables, so inconsistent with Harmony and Sound; and hobbling with auxiliary Verbs, so repugnant to Brevity and Force. It is small Wonder, that many Men should differ one with another about the Meaning of Words in a dead Language, when so few agree in the precise Ideas to be annexed to many Words in their own?

It is a bold Undertaking to translate any Author of Genius into any other Tongue, even a modern Author into a modern Tongue; though so many of the modern Tongues resemble and depend upon each other; and such Authors are generally mangled and cut, rather sunk and perverted, than translated. It must therefore be a very bold Attempt to undertake one of the great Antients, who are rarely to be known in a new Dress, in which their Spirit is generally degraded into Pertness, their Dignity evaporated in Bombast, their Ease lost in Flatness, and their Fluency in Chitchat. It is an Attempt I never intended to have made, and was indeed drawn into it. My first View was to write Discourses upon Tacitus, as an Author of wonderful Wisdom and Parts, who had long delighted me, and filled me with a Thousand Reflections, which I had a mind to connect and publish.

I had no Thoughts of translating him, till I was told by a Gentleman in the City(a), how ill he was translated; and he persuaded me to translate him, as well as comment upon him. Upon Examination, I found the English Translations of him to be such as I have represented them in the first Discourse prefixed to him.

I should have been extremely glad to have found a good Translation of Sallust. But that which we have of him is dry and tasteless, cold and heavy, full of Mistakes and vulgar Phrases, nothing of the Vivacity, or Fire, or Elevation, of Sallust; the Style knotty, harsh, and perplexed, so opposite to the round, perspicuous, and slowing Periods of Sallust. The Translator, far from warmed, much less inspired, by his Author, does not seem to feel him.

I therefore thought it necessary to make a new Translation, and no hard Task to make a better, however short of the Original. I thought mine the fittest to accompany the Discourses written upon him.

The great Point in translating, is to pursue, or, if possible, rather to assume and possess, the Spirit and Character of the Author. To render him Word for Word, will be insipid: Though it may be exact, it can never be just, unless the Sensation of the Author be conveyed, as well as his Words, and grammatical Meaning.

An able Writer not only gives, but enforces, his own Meaning: His Manner is as significant as his Words, and therefore becomes Part of his Sentiments. It is thus in Speaking as well as Writing: The liveliest Speech in the World, rehearsed by a heavy Man, will sound heavily. What moved, and sired, and charmed the Audience, out of one Mouth, would put them to Sleep out of another. An Oration of Demosthenes, repeated like a Lease by a Clerk; or one of Cicero’s, pronounced by a Pedant; instead of Rage and Terror, would rouse Laughter and Impatience.

Who can discover the Ardour and Vivacity of Horace, in the Version of Monsieur D’Acier? Yet D’Acier knew, as well as any Man, the Meaning of every Word in Horace, with all his Figures, Allusions, and References.

Plutarch, the entertaining judicious Plutarch, is a dry Writer, as translated by the same D’Acier, though accurately translated: Plutarch, translated by Amyot, is an entertaining, a pleasing Author: Yet, in Amyot’s Translation, there are numberless Mistakes: A French Critic, and a very learned Man, Monsieur Meziriac, reckons them at Two thousand, all very gross ones. D’Acier’s is an exact Translation of Plutarch’s Words: Amyot is a Copy of Plutarch himself; resembles his Author, and writes as well. Amyot is a Genius: D’Acier is a learned Man.

I am much concerned to see so learned and useful a Writer as Plutarch, make so ill a Figure in English: Most of his Lives are poorly Englished; nor is bad Language the worst Fault: They are full of egregious Blunders. Several of them are ill translated from Amyot, by such as understood not French. Many of the instructive Pieces, called his Morals, have fared as ill. A good Translation of all his Works would be a valuable Performance.

Who would not rather read a Discourse of Archbishop Tillotson’s upon any ordinary Subject, though ever so full of Inaccuracies, than a learned Dissertation of the correct Mr. Thomas Hearn upon the best Subject?

I doubt no Work of Genius can be well translated, but by an Author of Genius; and therefore, there can never be many tolerable Translations in the World. Cicero, in translating the noblest Greek Writers, has excelled them all: Cicero was a good Translator, because he was a great Genius.

Terence is only a Translator; but he had fine Taste, Politeness, and Parts, and a Genius for Comedy and genteel Conversation. This was his great Qualification: His Knowledge of the two Languages only helped him to shew it. He might have had great Skill in both, without Success, or Fame, as a Comic Poet. Terence translated Comedy with Applause, because he had a fine Genius for Comedy. He himself is shamefully travestied by Sir Roger L’Estrange, and Dr. Echard, and much gross Ribaldry fathered upon so pure and polite a Writer.

Mr. Hobbes has translated the Historian Thucydides well; for Mr. Hobbes had equal Talents for History: But he has ill translated Homer, though he well understood Homer; for he had not equal Talents for Poetry. Mr. Dryden, with all his Faults, and many unwarrantable Freedoms, has made a fine Translation of Virgil, because he was as great a Poet as Virgil; indeed, a great and various Poet: We have Poems of his, such as, I think, Virgil could not write; one Ode particularly, equal, if not superior, to any in Antiquity.

Many of the Speeches and brightest Passages in Lucan, are rendered by Mr. Row with equal Force, in a Language so unequal, because he had a Genius as warm and poetical as Lucan; though Lucan, with infinite Sinkings, has infinite Elevation, and many glorious Lines.

I have often wished, that such a fine Genius as Dr. Burnet of the Charter-house, had translated Livy. He had grave and grand Conceptions, with harmonious flowing Periods, equal to those of the great Roman Historian. Sir Walter Raleigh would have still done it better, as he was a wonderful Master of such Subjects, and wonderfully qualified to represent them. Many Parts of his History of the World are hardly to be matched, never to be exceeded; particularly his Relation of the second Punic War; where he recounts the Conduct of the Roman and Carthaginian Commonwealths, and of their several Commanders, especially of Hannibal, with surprising Capacity, Clearness, and Force.

There occurs to me one Passage out of the English Livy, which will shew what Justice we have done that noble and elegant Writer. A great Officer says to a Roman General in the Field, (I think he calls him Sir, too) ‘Whilst you stand Shilly-shally here, as a Man may say, the Enemy will tread upon your Toes.’ Could a Groom of that General have used meaner Language to a Fellow Groom? I give the Passage upon Memory—The Words are either Shilly-shally, or with your Hands in your Pockets, or both.

A Writer of Genius, translated by one who has none, or a mean one, will appear meanly. Even the Meaning of every Word may be conveyed, yet the Meaning of the Writer missed or mangled. It is in Translating, as in Painting: Where the Air, the Spirit, and Dignity of the Original are wanting, Resemblance is wanting. To be able to translate, a Man must be able to do something like what he translates.

What can be more unlike, what more unworthy of Virgil than Hannibal Caro’s Translation of Virgil’s Æneis into Italian? Dryden justly calls it scandalously mean, and adds, that he is a Foot-Poet, ‘and lacquies by the Side of Virgil at best, but never mounts behind him.’ Yet Hannibal Caro was far from being unacquainted with Virgil’s Meaning. He saw plainly what Virgil had done, but could not do like him, though he thought that he could: Ogilby too knew the Words and Grammar in Virgil; and only wanted Capacity to write like Virgil.

Sir Samuel Garth coming one Morning to visit the late Duke of Argyll, with a Book in his Hand, the Duke asked him what it was. The Knight told him, that it was a Philosophical Work of Tully’s, translated by a very Reverend Divine, and named Mr. Collyer. The Duke asked him, How Mr. Collyer had done it? ‘Gad, my Lord Duke, replied the Knight, he makes the Orator chatter very smartly.’

I have not examined, whether Sir Samuel’s Joke was as true as it was bitter: But surely, if Mr. Collyer’s Cicero chattered, he was no longer Marcus Tullius Cicero.

It hath been generally believed, upon the Credit, I suppose, of Grammarians and Commentators, Lipsius, I think, is one of them, that Tacitus imitates Sallust: A Discovery which I could never make; unless all Authors of Spirit and masterly Expression imitate one another. There is such Painting in Tacitus, as comes from no Pencil but his own. I cannot find that he imitates any Writer. I do not know any Writer that can be said to imitate Him; nor can any Writer, who has a Manner of his own, be properly said to imitate any other. Whom does Horace imitate? It cannot be Pindar; for, in my Opinion, he exceeds Pindar; though he compliments Pindar with being inimitable. Whom does Lucretius imitate? He had his Subject and System from Epicurus: His Style and Conceptions were his own. I know one who has written like Sallust, and equalled him both in Expression and Spirit; I mean Paterculus: It is true, he is much less read; for he wrote only an Abridgment of the History of the Romans; a Sort of Work never so taking as a History at Length, equally executed. Besides, he destroyed his moral Character, by his boundless Flattery to Tiberius, and his Minister Sejanus, and has been ever since discredited by the concurring Testimony of other Historians.

The Characters of Princes are, in a great measure, in the Power of Authors. Julius Cæsar and Augustus have derived fine Characters from fine, but flattering Writers, particularly from the Poets. Tiberius bears a terrible one from the Historians; though the Evil he did was but minute and contemptible, in Comparison with what Julius and Augustus did. He dispatched particular Romans: They slaughtered the Romans by Myriads.

For myself, I am far from pretending to write like Sallust, or to be so fit, as I ought, to translate him. I think I am not vain in saying, that I have done him more Justice, than hath been yet done him in English, I hope as much as is done him in any other Language. Nor am I afraid of Criticism. Where it is just and decent, (and, without Decency, it cannot be just) I shall chearfully submit to it, and be thankful for it. Where it is gross, or false, or angry, I shall not answer what I cannot retaliate. Criticism is never to be feared, merely from the Ill-will of the Critic. Detestable is that Criticism which Ill-will dictates. It is the more harmless, by its evident Bent to do Harm.

Spire and Outrage are Signs of a bad Cause, as well as Disqualifications for managing a good. No able Man wants the Aid of Scurrility; no good Man can use such Aid. Were Grossness and Abuse to be admitted into Criticism and Controversy, the foolishest Man would have the greatest Advantage, and be victorious over the Wisest. No wise Man (a Character always implying Temper and Manners) can excel in what he never can learn: No wise Man, no good-tempered Man, can therefore vye with Champions in Railing and Contumely. Foolish Men, (a Character which takes in even tolerable Parts, governed by violent Passions; I say, foolish Men) are ever the greatest Masters in this Sort of Style and Behaviour. The basest People are best qualified to give the basest Language.

It yields us some Consolation, that bitter and malevolent Tempers punish themselves: They are not always gratified; never so thoroughly as they wish, and therefore become Fuel to their own Malice. A spiteful Man is an unhappy Man, as well as an odious Character: If he would preserve Esteem, or hope for it, he must hide his Heart. He preys upon himself as much as he would upon others, and suffers under the Agnoies he would make others suffer, often under stronger Agonies. His bitter Wishes bring him more Anguish than he can inflict elsewhere; and, as he delights to hurt others, it must delight them to see him revenge them upon himself. At best, he is a wretched Being; the most he can hope for is Pity; and he is the more wretched, as he deserves none.

It is the Wisdom, it is the Goodness and Justice of Providence, to make malevolent Hearts their own Tormentors, and bad Men actually hurt themselves by wishing hurt to others. They earn and pre-occupy the Pain and Misery, which they study to inflict, and make Retribution to the Innocent and Deserving, for hating and reviling them. Envy is blasted by its own Breath; and injurious Censure turns to Praise. Who would chuse to possess the Bane of a rancorous Spirit? Who would seed the Torture of Envy? Who would burn with raging Rancour? Whoever hates any Man, pays dear for his Hate: Whoever is cursed with a revengeful Heart, needs no other Curse.

Whatever comes Abroad tolerably written, and gains Attention and Esteem, is sure to be attacked by the common Herd of Writers, who are generally foolish, malignant Men, and mad with Vanity. Amongst them there is no such Thing as a common Writer. They are all Men of Genius: A middling Poet, and a middling Painter, is not to be found; much less a bad Poet, or a bad Painter, or any bad Writer, in their own Opinion. Such as have the least Parts, boast the highest. Yet whilst they claim every Sufficiency to themselves, they will allow none elsewhere. They who want the most Indulgence, grant none. They who most try the Patience of others, exercise no Patience. Or if they have good Parts, with ill Nature, they have little to boast of: A good natured Fool is a better Character.

I have had great Experience of the Gentlemen of this Cast. I have had above an Hundred Antagonists, as great a Secret as the World would make of their Labours; to use the Words of a witty Man, very unjustly applied to a very great Man; I mean by Dr. Swift to Mr. Dryden. I found their Civility such as I could not return, and their Arguments such as needed no Answer. I have been abused most by such of them as I had most served; and thence found, that there are some Tempers so black as to be provoked with kind Usage. I have found some so vain, that no good Treatment could reach their Merit; some so craving, as only to be beholden for Favours to come; others, who having praised me too copiously, without any Court or Temptation from me, have abused me as plentifully, without being once offended by me: Others, so little scrupulous as to revile me for Writings which I never wrote: Others, who, after the highest Advantages received by my Means and Recommendation, chose me out for the chief Object of their Hate and Slander: Others, whom I have saved, with great Difficulty and Pains, from Disgrace and Ruin, have taken equal Pains to injure and asperse me. I can produce as high a Panegyric as ever was made upon Man, and as vile a Libel, both in Print, and both from the same Author; the former, without my ever having seen him, the latter, without ever having wronged him; nay, after I had done him a Thousand good Offices: And all his infinite and virulent Abuse was founded upon a crazy Mistake of his own. I have supported an Author for a whole Winter, and have had his Thanks next Summer in a furious printed Invective, whilst he was still writing me Letters full of Acknowledgement and high Professions.

The common Fraternity of Writers (a most unbrotherly Fraternity) furnish a Swarm of Critics. For, almost all Writers are Critics, in the rigorous but wrong Sense of the Word; and are therefore ready to damn and run down all superior Productions, and to shew the least Mercy to the most Merit. If any Work merit Praise, this is to them sufficient Provocation to decry it. I have known some of them appear fond of a Book, till they saw it succeed, then grow mad at its Success, and wonder at the foolish Taste of the Town. As I have received many Proofs of their Good-will, I know their Candour. I hope my Readers will judge for themselves. I have made my Thoughts clear to every understanding Reader: Foolish Readers will never understand, yet are sometimes the readiest to find Fault.

The smallest Writer has it in his Power, one Way, to imitate the greatest, with Success, by being modest and civil: If he cannot banish Spite, he may conceal it; if he shew none, he will have the Credit of having none: Whenever it appears, it brings Reproach; and he must needs be a very miserable and low Author, who produces nothing but his own Disgrace and Condemnation. To produce nothing Good, may be pardoned, if the Intention appear to be Good: To produce nothing but what deserves Reproach, is utterly unpardonable.

Ill-nature, or coarse Language, from Men of Parts, always impairs, sometimes ruins, their Character. Dr. Bentley was a most learned Man; a most sagacious and discerning Critic, though too bold a Guesser in Criticism. Had it not been for his rough Behaviour, his apparent Scorn and Contempt for all Men, particularly for those who differed from him, he would have been the most formidable Critic of his Time. His Self-sufficiency and coarse Manners sunk him, and disgraced a very extraordinary Character. This smothered his many Excellencies, and made all his Faults so glaring. Those who conquered him in Politeness, had the Applause; whilst he who conquered them in Argument, had none; as was manifestly the Case in the famous Dispute about the Epistles of Phalaris. His Name is vulgarly become a Name of Derision and Mirth, instead of Praise and Esteem. He who behaved like a Savage to all Men, was treated by all Men as a Savage. Thus he behaved, thus he wrote, and thus he fared. Though he was still formidable to those who knew his Strength; yet, many witty Men severely rallied him, and every Witling laughed at him; nay, they laughed with the World on their Side, even in Instances where he could have crushed all the Witlings in it. So much did he gain by defying all Men, and so little will every Man gain who does it. A stern dictating Pedant, whatever Learning he may have, has no Friends: Weak Men may fear him, and so may some very able Men, who care not to be exposed to Dirt and Invective; but no Man loves him.

What can smaller Writers, Men of inferior Genius, with equal Insolence and Brutality, expect, but to be as low in Contempt as they are high in Arrogance. All Authors of great and unmixed Fame, have been signal for Civility, for Candour, and Humanity, Mr. Locke, Dr. Tillotson, with another eminent Prelate now living, and Mr. Bayle: All great Names, all furiously attacked, but never returning the most furious Attacks with Fury; all engaged in Controversy, yet all exempt from controversial Sourness and Pedantry.

Mr. Bayle had more able Antagonists than ever Man had, with many who were very bitter and hot; yet, with all their Bitterness and Heat, he was never provoked to lose his Temper: He still preserved the Coolness and Dignity of a great Genius, perhaps, one of the most surprising that ever was in the World, joining so much Temper to so much Vivacity, such infinite Learning to such infinite Parts, such strong Reasoning to such delicate Raillery. As no Writings so bulky as his ever spread more, hardly so much, none will be more lasting, or deserve to be. I have always considered him and one of his snappish Antagonists, as two Animals of one Species, but as different in Temper as in Dignity and Size: With what Rage and Clamour does the Small one fly at the Great one? With what Unconcern, and Marks of Scorn, does the Great one treat the Small?

So much concerning Writers, and the Folly of Malice and Scurrility in Writings; how detrimental they are to themselves, how offensive to Readers; and how amiable and advantageous the contrary Conduct.

The Fragments of Sallust, containing some curious Tracts and Pieces of Eloquence, were translated by a Clergyman of my Acquaintance, at my Request: I knew him to be a Gentleman of polite Taste and Style, and a perfect Judge of both Languages; as his Performance will easily convince his Reader.

I have already mentioned, and shall hereafter mention, the Orations of Cicero against Catiline, translated in the following Work. I must here acquaint the Reader, that he is beholden, in a great measure, for the Translation of one of them, to one of the first Men of the Age, for Eloquence, Knowledge, and the Conduct of Affairs, and suitably distinguished in one of the first Stations in the Government.

Before I finish, I must inform my Readers, that I have more Service to offer them. I have been some Years engaged in the History of England, and intend to pursue it. They have hitherto used me well, and will, I hope, continue to do so, if I do not use them worse. So much Favour from my Readers in general, was what, I doubt, chiefly foured and disturbed some particular Readers, such especially, as, being themselves Writers, had not what they thought they deserved, equal kind Usage. It is the Lot of Writers: Whoever pleases many, is sure to offend many; and the more Approbation, the more Censure. All who can write themselves, though ever so ill, or fancy that they can, are Judges of Writing, often the severest Judges. Every peevish and conceited Reader, nay, such as cannot read, claim the same Privilege, and are ready to find many Faults, without a Capacity to discover any.

My first Intention was to write the Life of Cromwell only: But as I found, that in order to describe his Times, it was necessary to describe the Times which preceded and introduced his, and that I could not begin even at the Reformation, without recounting many public Incidents before the Reformation; I have begun at the Conquest, and gone through several Reigns, some of them seen and approved by the ablest Judges; such Judges as would animate the slowest Ambition. Half of it will probably appear a few Years hence: The Whole will conclude with the History of Cromwell.

POSTSCRIPT.

THOUGH I have, in general, blamed the Translation of Plutarch, I own there are some of his Lives translated very well.

The ill-natured and unjust Sneer I have quoted, as thrown at Mr. Dryden in the Tale of a Tub, I find, upon looking into the Book, to be applied to Mr. Tate, the Poet Laureat: But there presently follows something as bitter, said without Truth, of Mr. Dryden.

The Inscription of the last Discourse to a most noble Person, may create Inquiry, why nothing more is said to him, or of him, though there was Room for so much. I will only add, Something further would have been said, but for his express Commands to the contrary.

Endnotes

[(a) ] See the Second Discourse prefixed to the Annals of Tacitus.

[(a) ] Mr. Pate, the Woollen-draper, who knows more of the Character and Excellencies of the Classics than many who profess Languages and Science, and bear learned Appellations. He said, pleasantly, ‘That Tacitus was indeed unclassicked, but not translated.’

Political Discourses UPON SALLUST.

DISCOURSE I. Of Faction and Parties.

SECT. I. How easily the People are led into Faction, and kept in it, by their own Heat and Prejudices, and the Arts of their Leaders; how hard they are to be cured; and with what Partiality and Injustice each Side treats the other.

SALLUST observes, ‘That whoever raised Civil Dissentions in the Commonwealth, used plausible Pretences; some seeming to vindicate the Rights of the People; others to exalt the Authority of the Senate; Both Sorts to pursue the public Good; yet all only striving severally to procure Weight and Power to themselves. Neither, in these their Civil Contests, did any of them observe Moderation or Bounds: Whatever Party conquered, still used their Victory with Violence and Inhumanity.’ This, I doubt, is true of all Parties in their Pursuits and Success: I have, therefore, thought it pertinent to discourse here at large upon Faction and Parties.

The People are so apt to be drawn into Faction, and blindly to pursue the Steps of their Leaders, generally to their own special Prejudice, Loss, and Disquiet, if not to their utter Ruin, that he who would sincerely serve them, cannot do it more effectually, than by warning them against such ready and implicit Attachment to Names and Notions, however popular and plausible. From this evil Root have sprung many of the sore Calamities that, almost every-where, afflict Mankind. Without it the World had been happily ignorant of Tyranny and Slavery, the Two mighty Plagues that now haunt and devour the most and best Parts of it; together with the subordinate and introductory Miseries, of national Discord, Devastation, and Civil War.

People, as well as Princes, have been often undone by their Favourites. A great Man amongst them, perhaps, happened to be cried up for his fine Actions, or fine Qualities, both often overrated; and became presently their Idol, and they trusted him without Reserve: For their Love, like their Hate, is generally immoderate; nor from a Man who has done them, or can do them, much Good, have they any Apprehension of Evil; till some Rival for their Affection appear superior to their first Favourite in Art or Fortune; one who persuades them, that the other has abused them, and seeks their Ruin. Then, it is like, they make a sudden Turn, set up the latter against the former; and, having conceived an immoderate Opinion of Him, too, put immoderate Confidence in him; not that they are sure that the other had wronged them, or abused his Trust, but take it for granted, and punish him upon Presumption; trusting to the Arts and Accusations of their new Leader, who probably had deceived and inflamed them.

Thus Themistocles supplants Aristides, and is himself forced to yield to the superior Popularity of Cimon. Not that the People always want Judgment; for they sometimes judge truly, according to the Information which they have; but they are apt to credit Information too suddenly. Sometimes their Favourite preserves himself in their Esteem, in spight of all Rivals and Efforts; and pays them his Thanks for supporting him, by enslaving them. Thus acted Cæsar, Pisistratus, and Agathocles: Thus Alcibiades aimed at acting; and Pericles, in a good Degree, succeeded in his Aim; being a Tyrant without Arms, as one of the antient Writers calls him.

And as the People sometimes think themselves to have erred in their Choice, when they really have not, but are only seduced by false Insinuations; as in the Case of Aristides, who was certainly an upright Man: So when they have been mistaken, they often come to know it when it is too late; as in the Case of Cæsar; who, to fortify himself, had entered into a Confederacy with Pompey and Crassus, and thence formed the first Triumvirate. Upon this Occasion he suffered many popular Insults; and had the Mortification to see the Tide of popular Affection and Applause follow his warmest Opponents. But what availed it? He had carried his Point; and they came to their Senses too late(a).

They may possibly commit themselves to the Guidance of a Man, who certainly means them well, and seeks no base Advantage to himself: But such Instances are so rare, that the Experiment is never to be tried. Men, especially Men of Ambition, who are the forwardest to grasp at such an Office, do, chiefly, and in the first Place, consider Themselves; and, whilst guided by Partiality for themselves, cannot judge indifferently. Such a Man, measureing Reason and Justice by his Interest, may think, that it is right, that the People should always be deceived, should always be kept low, and under a severe Yoke, to hinder them from judging for Themselves, and throwing off Him, and to prevent their growing wanton and ungovernable. In short, the Fact is, (almost eternally) That their Leader only finds his Account in leading them, and They never, in being led. They make him considerable; that is, throw him into the Way of Power and Profit: This is his Point and End; and, in Consideration of all this, what does do he do for them? At best, he generally leaves them where he found them. Yet this is tolerable, nay, kind, in comparison of what oftener happens: Probably he has raised Feuds and Animosities amongst them, not to end in an Hundred Years; Fuel for intestine Wars; a Spirit of Licentiousness and Rebellion, or of Folly and Slavery.

In the midst of the Heats, and Zeal, and Divisions, into which they are drawn, for This Man against That, are they ever thoroughly apprised of the Merits and Source of the Dispute? Are they Masters of the real Facts, sufficient for accusing one, or for applauding another? Scarce ever. What Information they have, they have generally from interested Men, at best, quite partial and disguised, often utterly false and forged. But the Truth is, they have generally no Information at all; but only a few Cant Words, such as will always serve to animate a Mob; ‘I am for John: He is our Friend, and very honest. I am against Thomas: He is our worst Enemy, and very wicked, and deserves to be punished.’ And so say They who have taken a Fancy to Thomas, and are prejudiced against John. When it is likely, that neither John nor Thomas have done them much Harm, or much Good; or, perhaps, both John and Thomas study to delude and enthral them. But, when Passion prevails, Reason is not heard.

There is a sort of Witchcraft in Party, and in Party Cries, strangely wild and irresistible. One Name charms and composes; another Name, not better nor worse, fires and alarms. I remember when one Party could not hear, with Decency or Temper, the Name of the late Lord Oxford: I likewise remember, when that of the late Lord Godolphin was equally disgustful to another Party. I have lived to see both these Noble Persons mentioned with Applause, at least without Rancour, by many of all Parties indifferently. If one had then told any of those Party-Men, that the Time would come, when they would certainly change their Note, and give these two Ministers very different and favourable Characters, he would not have been believed: For angry Men fansy, that they shall always retain the same angry Ideas; and probably resolve it. They do not consider, that their Blood will not always boil, nor the same Object continue always to inflame them. They would do well, therefore, to reflect, that their present Passion, be it Rancour or Fondness, will certainly, some time or other, subside; and therefore should restrain it, lest it betray them into Inconsistency, and make them say now, what they will, perhaps, contradict hereafter; for then they must allow, that they acted from Warmth and Mistake. Such a Consideration would make Men wary of running headlong into Partialities, and of condemning, or adoring, merely because it is the Cry, and the Fashion; for nothing is so deceitful, and even fleering, as these Cries and Fashions are. It is common to see a Man idolized one Winter, and forgot before the next.

I am far from intending, by what I say, to dissuade People from inquiring into the Condition they are in, or how it fares with the Public. This is a just and necessary Inquiry, and deserves all Encouragement. But let them be sure to inquire conscientiously, and upon solid Grounds, and be thoroughly informed, before they judge, or censure, or applaud. What I blame, is, their swallowing current Lyes, believing Misrepresentations, and false Characters, and thence bearing Ill-will to some, who deserve it not; or entertaining extravagant Fondness for others, who deserve it as little. There is no Reliance upon what Parties say of one another, to the Praise of their Friends, or in Detraction from their Rivals; it is all Satire, or all Praise. This is enough to shew, that it deserves no Credit; since no Party was ever composed of Men altogether good, or altogether bad; all Bodies of Men are mixt, as are the Qualities of particular Men.