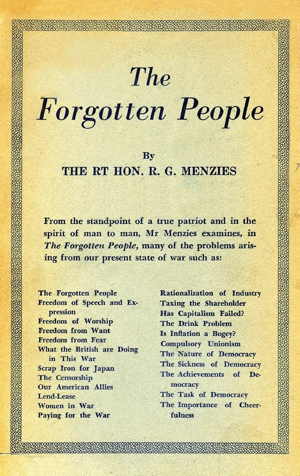

Robert Gordon Menzies, The Forgotten People: and Other Studies in Democracy (1943)

|

|

| Robert Gordon Menzies (1894-1978) |

Source

Robert Gordon Menzies, The Forgotten People: and Other Studies in Democracy (Sydney: Angus and Robertson, 1943).

These broadcasts were made over the radio between 22 May, 1942 and 20 November, 1942.

A second edition was published in 2011 by the Victorian Division of the Liberal Party: Robert Menzies, The Forgotten People: And Other Studies in Democracy. (Australia, Liberal Party of Australia, Victorian Division, 2011).

Transcripts of these brodcasts were originally published online at the Menzies Virtual Museum but have been removed and the site now seems to be inactive. Copies were retrieved from the Wayback Machine. The talk which gave the series its name, but not the other 36 talks, can be found at the Menzies Research Centre: “The Forgotten People”.

Table of Contents

- Foreword

- Chapter 1 - The Forgotten People (22 May, 1942)

- Chapter 2 - The Four Freedoms: Freedom of Speech and Expression (19 June, 1942)

- Chapter 3 - The Four Freedoms: Freedom of Speech and Expression (continued) (26 June, 1942)

- Chapter 4 - The Four Freedoms: Freedom of Worship (3 July, 1942)

- Chapter 5 - The Four Freedoms: Freedom from Want (10 July, 1942)

- Chapter 6 - The Four Freedoms: Freedom from Fear (17 July, 1942)

- Chapter 7 - The Four Freedoms: Freedom from Fear (continued) (24 July, 1942)

- Chapter 8 - Empire Control of an Empire War (30 January, 1942)

- Chapter 9 - What the British are doing in this War (6 February, 1942)

- Chapter 10 - Hatred as an Instrument of War Policy (10 April, 1942)

- Chapter 11 - Scrap iron for Japan (3 April, 1942)

- Chapter 12- The Censorship (6 March, 1942)

- Chapter 13 - The New Minister to Washington (15 May, 1942)

- Chapter 14 - Our American Allies (23 January, 1942)

- Chapter 15 - Lend-Lease (29 May, 1942)

- Chapter 16 - Women in War (20 February, 1942)

- Chapter 17 - Paying for the Wa (13 February, 1942)

- Chapter 18 - Post-war Planning (17 April, 1942)

- Chapter 19 - Rationalization of Industry (24 April, 1942)

- Chapter 20 - Taxing the Shareholder (31 July, 1942)

- Chapter 21 - Has Capitalism Failed? (7 August, 1942)

- Chapter 22 - The Drink Problem (4 September, 1942)

- Chapter 23 - Is Inflation a Bogey? (11 September, 1942)

- Chapter 24 - Compulsory Unionism (14 August, 1942)

- Chapter 25 - The Function of the Opposition in Parliament (8 May, 1942)

- Chapter 26 - The Opposition's Duty (28 August, 1942)

- Chapter 27 - The Government and Ourselves (5 June, 1942)

- Chapter 28 - Sea Power (18 September, 1942)

- Chapter 29 - The Statute of Westminster (9 October, 1942)

- Chapter 30 - Schools and the War (16 October, 1942)

- Chapter 31 - The Moral Element in Total War (21 August, 1942)

- Chapter 32 - The Law and the Citize (12 June, 1942)

- Chapter 33 - The Nature of Democracy (23 October, 1942)

- Chapter 34 - The Sickness of Democracy (30 October, 1942)

- Chapter 35 - The Achievements of Democracy (6 November, 1942)

- Chapter 36 - The Task of Democracy (13 November, 1942)

- Chapter 37 - The Importance of Cheerfulnes (20 November, 1942)

Foreword↩

“The broadcast essays in this volume were delivered weekly during 1942. Some of them deal with matters of permanent interest while others are dated by passing events. They have represented a serious attempt to clarify my own mind and assist listeners on questions which emerge in the changing currents of war. In a sense, within the acute limits of time and space, they represent a summarized political philosophy to which many thousands have been interested enough to listen and which hundreds of listeners-in have asked me to publish.

“It should perhaps be stated that their preparation and delivery have been a purely voluntary contribution on my part to the solution of contemporary problems. I am indebted to Station 2UE, Sydney, and its associated stations in Victoria and Queensland, for their courtesy in enabling this to be done; and to Messrs Robertson and Mullens Ltd of Melbourne for having published and circulated at their own cost the broadcast “The Forgotten People”, which gives its name to this book.”

Chapter 1 - The Forgotten People↩

Quite recently, a bishop wrote a letter to a great daily newspaper. His theme was the importance of doing justice to the workers. His belief, apparently, was that the workers are those who work with their hands. He sought to divide the people of Australia into classes. He was obviously suffering from what has for years seemed to me to be our greatest political disease - the disease of thinking that the community is divided into the rich and relatively idle, and the laborious poor, and that every social and political controversy can be resolved into the question: What side are you on?

Now, the last thing that I want to do is to commence or take part in a false war of this kind. In a country like Australia the class war must always be a false war. But if we are to talk of classes, then the time has come to say something of the forgotten class - the middle class - those people who are constantly in danger of being ground between the upper and the nether millstones of the false class war; the middle class who, properly regarded, represent the backbone of this country.

We do not have classes here as in England, and therefore the terms do not mean the same; so I must define what I mean when I use the expression "middle class'.

Let me first define it by exclusion. I exclude at one end of the scale the rich and powerful: those who control great funds and enterprises, and are as a rule able to protect themselves - though it must be said that in a political sense they have as a rule shown neither comprehension nor competence. But I exclude them because in most material difficulties, the rich can look after themselves.

I exclude at the other end of the scale the mass of unskilled people, almost invariably well-organized, and with their wages and conditions protected by popular law. What I am excluding them from is my definition of middle class. We cannot exclude them from the problem of social progress, for one of the prime objects of modern social and political policy is to give to them a proper measure of security, and provide the conditions which will enable them to acquire skill and knowledge and individuality.

These exclusions being made, I include the intervening range - the kind of people I myself represent in Parliament - salary earners, shopkeepers, skilled artisans, professional men and women, farmers, and so on. These are, in the political and economic sense, the middle class. They are for the most part unorganized and unselfconscious. They are envied by those whose social benefits are largely obtained by taxing them. They are not rich enough to have individual power. They are taken for granted by each political party in turn. They are not sufficiently lacking in individualism to be organized for what in these days we call "pressure politics". And yet, as I have said, they are the backbone of the nation.

The communist has always hated what he calls the "bourgeoisie", because he sees clearly that the existence of one has kept British countries from revolution, while the substantial absence of one in feudal France at the end of the eighteenth century and in Tsarist Russia at the end of the last war made revolution easy and indeed inevitable.

You may say to me, "Why bring this matter up at this stage, when we are fighting a war in the result of which we are all equally concerned?" My answer is that I am bringing it up because under the pressures of war we may, if we are not careful - if we are not as thoughtful as the times will permit us to be - inflict a fatal injury upon our own backbone.

In point of political, industrial and social theory and practice there are great delays in time of war. But there are also great accelerations. We must watch each, remembering always that whether we know it or not, and whether we like it or not, the foundations of whatever new order is to come after the war are inevitably being laid down now. We cannot go wrong right up to the peace treaty and expect suddenly thereafter to go right.

Now, what is the value of this middle class, so defined and described? First, it has "a stake in the country". It has responsibility for homes - homes material, homes human, homes spiritual.

I do not believe that the real life of this nation is to be found either in great luxury hotels and the petty gossip of so-called fashionable suburbs, or in the officialdom of organized masses. It is to be found in the homes of people who are nameless and unadvertised, and who, whatever their individual religious conviction or dogma, see in their children their greatest contribution to the immortality of their race. The home is the foundation of sanity and sobriety; it is the indispensable condition of continuity; its health determines the health of society as a whole.

I have mentioned homes material, homes human, and homes spiritual. Let me take them in their order. What do I mean by "homes material"?

The material home represents the concrete expression of the habits of frugality and saving "for a home of our own". Your advanced socialist may rage against private property even while he acquires it; but one of the best instincts in us is that which induces us to have one little piece of earth with a house and a garden which is ours: to which we can withdraw, in which we can be among our friends, into which no stranger may come against our will.

If you consider it, you will see that if, as in the old saying, "the Englishman's home is his castle", it is this very fact that leads on to the conclusion that he who seeks to violate that law by violating the soil of England must be repelled and defeated.

National patriotism, in other words, inevitably springs from the instinct to defend and preserve our own homes.

Then we have homes human. A great house, full of loneliness, is not a home. "Stone walls do not a prison make", not do they make a house. They may equally make a stable or a piggery. Brick walls, dormer windows and central heating need not make more than a hotel. My home is where my wife and children are. The instinct to be with them is the great instinct of civilized man; the instinct to give them a chance in life - to make them not leaners but lifters - is a noble instinct.

If Scotland has made a great contribution to the theory and practice of education, it is because of the tradition of Scottish homes. The Scottish ploughman, walking behind his team, cons ways and means of making his son a farmer, and so he sends him to the village school. The Scottish farmer ponders upon the future of his son, and sees it most assured not by the inheritance of money but by the acquisition of that knowledge which will give him power; and so the sons of many Scottish farmers find their way to Edinburgh and a university degree.

The great question is, "How can I qualify my son to help society?" Not, as we have so frequently thought, "How can I qualify society to help my son?" If human homes are to fulfil their destiny, then we must have frugality and saving for education and progress.

And finally, we have homes spiritual. This is a notion which finds its simplest and most moving expression in "The Cotter's Saturday Night" of Burns. Human nature is at its greatest when it combines dependence upon God with independence of man.

We offer no affront - on the contrary we have nothing but the warmest human compassion - towards those whom fate has compelled to live upon the bounty of the State, when we say that the greatest element in a strong people is a fierce independence of spirit. This is the only real freedom, and it has as its corollary a brave acceptance of unclouded individual responsibility. The moment a man seeks moral and intellectual refuge in the emotions of a crowd, he ceases to be a human being and becomes a cipher. The home spiritual so understood is not produced by lassitude or by dependence; it is produced by self-sacrifice, by frugality and saving.

In a war, as indeed at most times, we become the ready victims of phrases. We speak glibly of may things without pausing to consider what they signify. We speak of "financial power", forgetting that the financial power of 1942 is based upon the savings of generations which have preceded it. We speak of "morale" as if it were a quality induced from without - created by others for our benefit - when in truth there can be no national morale which is not based upon the individual courage of men and women. We speak of "man power" as if it were a mere matter of arithmetic: as if it were made up of a multiplication of men and muscles without spirit.

Second, the middle class, more than any other, provides the intelligent ambition which is the motive power of human progress. The idea entertained by many people that, in a well-constituted world, we shall all live on the State in the quintessence of madness, for what is the State but us ? We collectively must provide what we individually receive.

The great vice of democracy - a vice which is exacting a bitter retribution from it at this moment - is that for a generation we have been busy getting ourselves on to the list of beneficiaries and removing ourselves from the list of contributors, as if somewhere there was somebody else's wealth and somebody else's effort on which we could thrive.

To discourage ambition, to envy success, to hate achieved superiority, to distrust independent thought, to sneer at and impute false motives to public service - these are the maladies of modern democracy, and of Australian democracy in particular. Yet ambition, effort, thinking, and readiness to serve are not only the design and objectives of self-government but are the essential conditions of its success. If this is not so, then we had better put back the clock, and search for a benevolent autocracy once more.

Where do we find these great elements most commonly? Among the defensive and comfortable rich, among the unthinking and unskilled mass, or among what I have called the "middle class"?

Third, the middle class provides more than perhaps any other the intellectual life which marks us off from the beast: the life which finds room for literature, for the arts, for science, for medicine and the law.

Consider the case of literature and art. Could these survive as a department of State? Are we to publish our poets according to their political colour? Is the State to decree surrealism because surrealism gets a heavy vote in a key electorate? The truth is that no great book was ever written and no great picture ever painted by the clock or according to civil service rules. These things are done by man, not men. You cannot regiment them. They require opportunity, and sometimes leisure. The artist, if he is to live, must have a buyer; the writer an audience. He finds them among frugal people to whom the margin above bare living means a chance to reach out a little towards that heaven which is just beyond our grasp. It has always seemed to me, for example, that an artist is better helped by the man who sacrifices something to buy a picture he loves than by a rich patron who follows the fashion.

Fourth, this middle class maintains and fills the higher schools and universities, and so feeds the lamp of learning.

What are schools for? To train people for examinations, to enable people to comply with the law, or to produce developed men and women?

Are the universities mere technical schools, or have they as one of their functions the preservation of pure learning, bringing in its train not merely riches for the imagination but a comparative sense for the mind, and leading to what we need so badly - the recognition of values which are other than pecuniary?

One of the great blots on our modern living is the cult of false values, a repeated application of the test of money, notoriety, applause. A world in which a comedian or a beautiful half-wit on the screen can be paid fabulous sums, whilst scientific researchers and discoverers can suffer neglect and starvation, is a world which needs to have its sense of values violently set right.

Now, have we realized and recognized these things, or is most of our policy designed to discourage or penalize thrift, to encourage dependence on the State, to bring about a dull equality on the fantastic idea that all men are equal in mind and needs and deserts: to level down by taking the mountains our of the landscape, to weigh men according to their political organisations and power - as votes and not as human beings? These are formidable questions, and we cannot escape from answering them if there is really to be a new order for the world.

I have been actively engaged in politics for fourteen years in the State of Victoria and in the Commonwealth of Australia. In that period I cannot readily recall many occasions upon which any policy was pursued which was designed to help the thrifty, to encourage independence, to recognize the divine and valuable variations of men's minds. On the contrary, there have been many instances in which the votes of the thriftless have been used to defeat the thrifty. On occasions of emergency, as in the depression and during the war, we have hastened to make it clear that the provision made by man for his own retirement and old age is not half as sacrosanct as the provision the State would have made for him had he never saved at all.

We have talked of income from savings as if it possessed a somewhat discreditable character. We have taxed it more and more heavily. We have spoken slightingly of the earning of interest at the very moment when we have advocated new pensions and social schemes. I have myself heard a minister of power and influence declare that no deprivation is suffered by a man if he still has the means to fill his stomach, clothe his body and keep a roof over his head. And yet the truth is, as I have endeavoured to show, that frugal people who strive for and obtain the margin above these materially necessary things are the whole foundation of a really active and developing national life.

The case for the middle class is the case for a dynamic democracy as against a stagnant one. Stagnant waters are level, and in them the scum rises. Active waters are never level; they toss and tumble and have crests and troughs; but the scientists tell us that they purify themselves in a few hundred yards.

That we are all, as human souls, of like value cannot be denied. That each of us should have his chance is and must be the great objective of political and social policy. But to say that the industrious and intelligent son of self-sacrificing and saving and forward-looking parents has the same social deserts and even material needs as the dull offspring of stupid and improvident parents is absurd.

If the motto is to be, "Eat, drink and be merry, for tomorrow you will die, and if it chances you don't die, the State will look after you; but if you don't eat, drink and be merry, and save, we shall take your savings from you", then the whole business of life will become foundationless.

Are you looking forward to a breed of men after the war who will have become boneless wonders? Leaners grow flabby; lifters grow muscles. Men without ambition readily become slaves. Indeed, there is much more slavery in Australia than most people imagine. How many hundreds of thousands of us are slaves to greed, to fear, to newspapers, to public opinion - represented by the accumulated views of our neighbours! Landless men smell the vapours of the street corner. Landed men smell the brown earth, and plant their feet upon it and know that it is good.

To all of this many of my friends will retort, "Ah, that's all very well, but when this war is over the levellers will have won the day." My answer is that, on the contrary, men will come out of this war as gloriously unequal in many things as when they entered it. Much wealth will have been destroyed; inherited riches will be suspect; a fellowship of suffering, if we really experience it, will have opened many hearts and perhaps closed many mouths. Many great edifices will have fallen, and we shall be able to study foundations as never before, because the war will have exposed them.

But I do not believe that we shall come out into the over-lordship of an all-powerful State on whose benevolence we shall live, spineless and effortless - a State which will dole out bread and ideas with neatly regulated accuracy; where we shall all have our dividend without subscribing our capital; where the Government, that almost deity, will nurse us and rear us and maintain us and pension us and bury us; where we shall all be civil servants, and all presumably, since we are equal, heads of departments.

If the new world is to be a world of men, we must be not pallid and bloodless ghosts, but a community of people whose motto shall be, "To strive, to seek, to find, and not to yield". Individual enterprise must drive us forward. That does not mean that we are to return to the old and selfish notions of laissez-faire. The functions of the State will be much more than merely keeping the ring within which the competitors will fight. Our social and industrial obligations will be increased. There will be more law, not less; more control, not less.

But what really happens to us will depend on how many people we have who are of the great and sober and dynamic middle-class - the strivers, the planners, the ambitious ones. We shall destroy them at our peril.

22 May, 1942

Chapter 2 - The Four Freedoms: Freedom of Speech and Expression↩

Speaking last year, President Roosevelt, in discussing the things at stake in this war, made use of an expression - "The Four Freedoms" - which has now found currency in most of our mouths. The four freedoms to which he referred were: freedom of speech and expression, freedom of worship, freedom from want, freedom from fear.

One has only to state them to get a response from the listener. Every one of us will at once say, "Ah yes, I believe in those freedoms. The President is right." That the President is right I have no doubt myself; but that we either fully understand or believe in these freedoms is open to some question.

I propose therefore, in this and my next few broadcasts, to take each of these four freedoms and in turn, endeavour to get at its meaning and significance, and work out what it involves in our own living and thinking.

Tonight, then, I take the first freedom - freedom of speech and expression - which connotes also freedom of thought. This is a magnificent ideal, but what does it mean?

Let us, on the threshold of our consideration, remember that the whole essence of freedom is that it is freedom for others as well as for ourselves: freedom for people who disagree with us as well as for our supporters; freedom for minorities as well as for majorities. Here we have a conception which is not born with us but which we must painfully acquire. Most of us have no instinct at all to preserve the right of the other fellow to think what he likes about our beliefs and say what he likes about our opinions. The more primitive the community the less freedom of thought and expression is it likely to concede.

All things considered, the worst crime of fascism and its twin brother, German national socialism, is their suppression of free thought and free speech. It is one of the many proofs that, with all their cleverness, they are primitive and reactionary movements. One of the first actions of the Nazis in Germany was to regiment the newspapers by telling them exactly what they could print. The result was that newspaper controversy came to an end, since all sang the same tune. When I was in Berlin in 1938 I mentioned this phenomenon to a high German official of the Foreign Office and, with about the one gleam of humour that I encountered on that visit, he replied that he thought it quite' a good idea, since it saved buying more than one newspaper. As you probably know, I am one who has in recent years had a severe battering from many newspapers, but I am still shocked to think that intelligent men, in what they believe to be a free country, can deny to the newspapers or to critics of any degree the right to batter at people or policies whom they dislike or of whom they disapprove.

Now, why is this freedom of real importance to humanity? The answer is that what appears to be today's truth is frequently tomorrow's error. There is nothing absolute about the truth. It is elusive. In the old phrase, "it lies at the bottom of a deep well". It is hard to come at. So few of us have objective minds - detached minds - and what we conceive to be the truth is very often coloured or distorted by our own passions or interests or prejudices. Hence, if truth is to emerge and in the long run be triumphant, the process of free debate - the untrammelled clash of opinion - must go on.

There are fascist tendencies in all countries - a sort of latent tyranny. And they exist, be it remembered, in radical as well as in conservative quarters. Suppression of attack, which is based upon suppression of really free thought, is the instinctive weapon of the vested interest. And vested interests are not all one way. We have, for example, waged a fairly successful war against profit-making vested interests in the last two or three years; the war has placed an almost crushing burden upon them. But it would be indeed a casual observer who failed to notice that the vested interests of the great trade unions are growing. All these interests must remember - and so must we who are ordinary members of the public - that great groups which feel their power are at once subject to tremendous temptations to use that power so as to limit the freedom of others.

Many of you will recall John Stuart Mill's famous essay on Liberty, which was published eighty-three years ago, but is still full of freshness and truth. In the course of that essay Mill stated many principles, four of which I should like to put to you in his own words. First:

There is a limit to the legitimate interference of collective opinion with individual independence: and to find that limit, and maintain it against encroachment, is as indispensable to a good condition of human affairs as protection against political despotism.

What is being pointed to in that passage is the easily forgotten truth that the despotism of a majority may be just as bad as the despotism of one man. Public opinion in a reasonable educated community will, I believe, in the long run over a term of years, tend to be sound and just; but public day-to-day opinion, which must frequently be ill-informed, is quite capable of being not only wrong, but so extravagant as to be unjust and oppressive.

My second passage from Mill is this:

The principle is, that the sole end for which mankind are warranted, individually or collectively, in interfering with the liberty of action of any of their number is self-protection. That the only purpose for which power can be rightfully exercised over any member of a civilized community, against his will, is to prevent harm to others.

Here again we have a pregnant truth. It is a good rule, not only of common law but of social morality, that we must so use our own as not to injure others. The man who claims too much aggressive liberty for himself may be getting it at the expense of somebody else. Liberty is for all, not for some.

Mill next says:

As the tendency of all changes taking place in the world is to strengthen society and diminish the power of the individual, this encroachment is not one of the evils which tend spontaneously to disappear, but, on the contrary, to grow more and more formidable.

I find this passage particularly illuminating. Fascism and the Nazi movement are both based on social philosophy which elevates the all-powerful State and makes the rights of the individual, not matters of inherent dignity but matters merely of concession by the State. Each says to the ordinary citizen, "Your rights are not those you were born with, but those which of our kindness we allow you." It is good to be reminded by Mill that this tendency is not confined to any one country. As the organization of society becomes more complex we must be increasingly vigilant for the freedom of our minds and spirits.

My final passage from Mill is this:

Complete liberty of contradicting and disproving our opinion is the very condition which justifies us in assuming its truth for purposes of action: and on no other terms can a being with human faculties have any rational assurance of being right.

In other words, it is a poorly founded and weakly held belief which cannot resist the onset of another man's critical mind.

There are, without doubt, limits on all these matters in time of war. When the battle is on, when nations are in a death struggle with other nations, the supremacy of the national security is clear and undoubted. That is the whole justification for wartime censorship, as well as the element that sets limits to it.

But even in time of war we must watch these things. You will agree that I speak as one with some practical - occasionally painful - experience, when I say that the arrow of the critic is never pleasant and is sometimes poisoned. Much criticism is acutely partisan or actually unjust. But every man engaged in public affairs must sustain it with a good courage and a cheerful heart. He may, if he can, confute his critic, but he must not suppress him. Power is apt to produce a kind of drunkenness, and it needs the cold douche of the critic to correct it.

There are, at times like these, temptations towards political censorship or, what is just as bad, politically conscious censorship. The temptation towards suppression of thought and speech is greatest of all in time of war because at such a time people say, "Let us have strength!" - all too frequently meaning, by "strength", suppression; whereas the truth is that it requires more strength of character to sustain adverse or bitter criticism than to say, with a grand gesture, "Off with the critic's head!"

We are, if we take thought about them, conscious of certain facts. It requires great moral courage to put an unpopular view in Parliament or on the platform; to speak and vote against a popular but foolish strike at a union meeting; to denounce social evils amid the disturbed and relaxed social conditions and standards of war.

All these things are proof that we are as yet far short of really understanding or practising President Roosevelt's first freedom.

In a few minutes one can do little more than indicate the nature of the problem. But it is clear that it gives us much food for thought and self-examination.

Of all the countries I have visited, England is the one where freedom of thought and expression is best understood. And that fact has given to the English people a wide tolerance of opinion and a quiet wisdom of understanding that we have yet to achieve.

19 June, 1942

Chapter 3 - The Four Freedoms: Freedom of Speech and Expression (continued)↩

Last week when I spoke to you of the first of President Roosevelt's four freedoms - freedom of speech, I had intended to deal this week with the second freedom - freedom of worship. But the programme must, I think, be altered, for last week's broadcast, in which the theme was the importance to democratic civilisation of free criticism, was interpreted in some quarters as a special plea for some special kind of freedom for the Press. Now, I believe in a free Press, and in no way undervalue its importance; but I do not believe in a privileged Press.

There is something to be said for the view that in a democracy the eternal and real conflict is between freedom for all and privilege for some. Let me take your time tonight in explaining what I mean by that.

The Press of Australia, very naturally, devotes a good deal of space to discussing public men. They will, I am sure, have no objection to the process being, for once, courteously reversed.

I have never been able to accept the idea that newspapers have some detached existence apart from that of the human beings who conduct them. Newspapers are as a rule owned either by one man or a few men, sometimes with long family traditions; or by a public company with perhaps many investors. They are business enterprises, conducted with marked efficiency, gathering and selling news and advertisements, and seasoning the whole with topical comment and criticism. All this is quite proper, even though it has some modern features which are to be regretted.

The editor or controller of the newspaper has a perfect right to criticize, to praise, or to blame, according to the personal opinion of his proprietor, or the joint opinion of his directors or shareholders. He has a right of free thought and free speech with which we will interfere at our own peril. But his right of free thought and free speech is one which he shares with Mr Brown the butcher, and Mr Robinson the bricklayer. He can have no privilege beyond Brown and Robinson; he is equally subject to the laws of defamation. Every good newspaper will admit that you do not purchase any special privilege to defame when you acquire enough money to purchase or found a newspaper; nor do you, in my opinion, purchase a privilege to criticize beyond that enjoyed by other citizens. You merely secure a wider audience and, properly considered, shoulder greater responsibilities. For, if Brown libels me, little harm may be done; it all depends on Brown's weight and influence. But if the Daily Thunderer, with half a million readers, libels me, irreparable harm is done to me, because people impute to the Thunderer a sort of unearthly wisdom and uncommon knowledge which induces some of them to say, "It must be true. I read it in the paper." Or, more fatuously still, "I don't know, of course, old man, but where there's smoke, there's fire."

If the Press, then, is to see its function in modern society aright, it well dwell on its responsibilities - as indeed I know its best men do - as well as upon its rights, valuable and essential though those rights undoubtedly are.

What are responsibilities?

Last week I spoke with repugnance of the ever-present political temptation, particularly when the lash of the critic is still smarting, to suppress or issue orders to the newspapers. There is at least an equal temptation on the part of the newspapers to claim the right to suppress the politician, to ignore him if his views are unsatisfactory: to leave him out, not because he says nothing worth saying, but because his views, however admirably expressed, do not suit the paper's policy, or because he himself is out of favour with the newspaper's editor or reporter.

In a word, it is the duty of any newspaper which claims the right of free criticism to publish enough of both sides to make its own views and criticisms intelligible and fair. It is a commonplace of the law of libel that comment must be not only fair, but made on facts. This point is vital to the survival of the Press as a free institution. That this is not always recognized will be clear when I tell you, for example, that for months after my resignation as Prime Minister, one newspaper, evidently carrying its hostility beyond defeat, never mentioned my name except in connection with some entirely false report of my alleged political activities. There was no question of unfortunate error; nor had I become, so far as I know, suddenly and completely mentally defective. The campaign was deliberate and sustained.

Now, that is a mere personal example to illustrate something quite important. The damage done to me is of minor significance. What is really significant is that such a newspaper, following such a practice, is threatened far more by its own inherent misconception of its function than by the activities of its enemies. I say that as one who has never suppressed criticism, even when it was unfair and falsely founded, and who believes that the function of the critic, truly seen, is vital to the establishing of the truth.

There is another tendency among some newspapers to depart from the old and good journalistic tradition. That tradition was to report fairly and without comment; and, separately, to criticize strongly and, if necessary, bitterly. The public mind was informed by the reporter and persuaded by the leader-writer. But there is today a perceptible tendency to mingle report with comment so that you do not know whether you are reading what Brown said or what young Smith, the reporter, thinks of what Brown said.

Reporting of this kind is not reporting at all. It is misleading; it can confer no privilege and excite not respect. That last observation is important. A critic, to carry weight, must be respected. For a man to be respected he must respect others. A free Press must not set itself up to be the masters of the people, for in a democratic community the people should prefer the master they have themselves chosen to those who are merely self-appointed. In other words, a free Press must not seek to maintain its freedom at the expense of popular freedom and popular self-government.

In dealing with men and affairs, the newspaper which claims free speech and opinion as of the very stuff of our liberty - as indeed they are - will no more be restrained merely by the laws of defamation than honest men are merely by the policeman; it will be restrained by that sense of responsibility which should always attach to great power. For the Press has great power, and inevitably so. In a democratic world, great power destroys itself only when it seeks to become tyranny.

And so, let us have free Press, and let us have free readers whose letter will be published, even though hostile. Let us have honest and fearless criticism of politician by Press and of Press by politician, and let each be heard. Above all, let us get back to the "facts, the whole of the facts, and nothing but the facts" as the true basis of intelligent freedom.

"And ye shall know the truth, and the truth shall make you free." If our diet is to become one of half-truths and prejudice and unfounded comment, either in Parliament or the Press, we shall become slaves.

In time of war these questions, far from disappearing, become particularly acute. The power of censorship offers great temptation to political administrators. The eagerness of millions of people for the latest news, and perhaps excitement, and the natural tendency to look for scapegoats after every defeat offer temptations to the Press. It is unfortunate that both Parliament and Press cannot regard themselves as engaged in a vital joint enterprise in which each must be fearless but restrained; in which each is looked to for good judgement; in which each should look to discharge its own function without seeking to control or discredit the other. In this way authority and freedom would show that they could march side by side to a battle where both must win if either is to survive.

26 June, 1942

Chapter 4 - The Four Freedoms: Freedom of Worship↩

President Roosevelt's second freedom is freedom of worship. What does it mean? Do we really understand it? Do we really believe in it?

I remember having a curious conversation once at my back door with an earnest partisan who demanded to know of me - this was when I was Attorney-General of Victoria - why the Government had not prohibited a Eucharistic procession. On my mildly asking why, he opened up on me. "My ancestors," he said, "fought for religious freedom and not to have a lot of people conducting a procession that's an affront to every Protestant."

Now, though a Protestant myself, this took me aback, and when I recovered I pointed out to him - for I gathered that he was a Scotsman, - that the religious freedom for which the Scottish Covenanters fought was freedom for all, Catholic or Protestant, Jew or Gentile, and that to deny it was to go back to the dark ages of man. Religious persecution was the denial of freedom. Freedom of worship is the victorious enemy of persecution.

And so I revert to the theme of my broadcast on the first freedom - that freedom, if it is to mean anything, must mean freedom for my neighbour as well as for myself. There is nothing defiant or sectional about a demand for genuine freedom of worship, which is freedom for all.

And what does freedom for all mean? It means, among other things, that we must be free to worship or not to worship. There have been honest and indeed noble men in this world who have never been able to find a God. Are we to deny them their place? There are many men who, profoundly and instinctively religious by nature, have never been able to accept what we call "revealed religion" or the doctrine of any church. There are many millions who find a guide and comfort in life through the doctrine and authority of the church of Rome. There are millions of others who reject that doctrine and authority and, as Anglicans, Presbyterians, Methodists, or otherwise, worship God in their own way. And so one might go on.

We are a diversity of creatures, with a diversity of minds and emotions and imaginations and faiths. When we claim freedom of worship we claim room and respect for all.

Sectarian strife is the enemy of freedom or worship, not its friend. It is the denial of Christianity, not its proof. It is indeed a poor religion which consists merely of opposing somebody else's faith, which produces not faith itself nor understanding nor tolerance nor generosity, but malice and hatred and all uncharitableness.

One of the most upright men and choicest spirits to serve the people in Parliament in my time was the late Thomas Rainsford Bavin, formerly Premier of New South Wales. Himself a Protestant, he spoke as Premier, in 1928, at St Mary's Cathedral, Sydney, during a Eucharistic congress. The small-minded - those to whom freedom of worship means "freedom for my kind of worship, but not yours" - complained.

But what did Bavin say? I quote his noble words:

This Cathedral embodies and represents for us those spiritual instincts, that insistent craving for something beyond and above merely material ends which, though often covered up by the dust and ashes for our everyday life, is after all the strongest force in human life - the fountain light of all our day, the master light of all our seeing.

Those instincts express themselves in many forms and in various creeds. They sometimes have led to strife and discord. This should not be so. They should, and I hope will, remind us that the things which unite us as human beings are deeper and more lasting that the things that divide us as members of different creeds. They should be a source of harmony and unity, not of discord and strife; of tolerance and generosity, not of intolerance and bigotry. For, after all, what are they but the gold chains by which the whole round earth is bound in every way about the feet of God?

The Apostle Paul had something like this in mind when he wrote his famous words: "And now abideth faith, hope, charity, these three; but the greatest of these is charity."

We saw on a previous occasion how the Nazi tyranny has struck at freedom of thought and speech; we know how it has also struck at freedom of worship. Not only is the citizen to be told how he shall think and speak of the affairs of his fellow men, but the secret communings of his spirit are also to be controlled. With all our modern cleverness - with our wireless waves and aeroplanes and almost thinking machines - we are still only on the fringes of the universe of thought. We grope out towards the light, seeing an occasional flash of beauty or of understanding, hearing occasionally the penetrating voices of reason. Civilization is in the heart and mind of man, not in the work of his hands. An in the heart of every man, whatever he may call himself, is that instinct to touch the unknown, to know what comes after, to see the invisible.

There is a great instinct in all of us for immortality. There is a consciousness in most of us that some day all will come to light and we shall be judged.

As we put out upon this vast territory of the soul, is there not room for all of us? Shall we turn aside from the search to wrangle, to attack and to defend, or shall we get wisdom and understanding, and with them tolerance, and a true freedom?

To some good people I know, tolerance means a weak evasion of the duty to denounce and frustrate evil. But they are wrong. We are bound to be enemies to evil when we see it, but we are not bound to be enemies to our fellowman. Tolerance does not mean laziness. The truly free man is tolerant, not of those corroding and corrupting things that all free men will try to destroy, but of other honest men who, hating the same evil, see a different road by which to come against it.

"In my Father's house there are many mansions." That is no reference to the architecture of a physical heaven. All it means is that there is room for all of us, so that we be honest men. Each of us has his own faith, and no mortal man may compel it or suppress it. That is, I believe, a freedom worth fighting for.

3 July, 1942

Chapter 5 - The Four Freedoms: Freedom from Want↩

My subject tonight is the third of President Roosevelt's four freedoms - freedom from want.

Here we have one of the most complex of human problems. As we approach it we find ourselves pressed by two considerations, each of which is powerful, each of which acts in opposition to the other. Perhaps in the result we shall find ourselves using these competing pressures in order to establish a firm structure.

On the one hand we have the fact that the struggle for existence and for progress brings out the best in man, and leads, as history has repeatedly shown, to strength and endurance. On the other hand we have the equally clear fact that a never-ending and never-quite-succeeding struggle on the fringe of reasonable existence is destructive of hope and of humanity, which naturally looks for the time, in Browning's words, "when body gets its sop, and holds its noise, and leaves soul free a little".

Let me put the matter in another way. The arriving at a true answer to any difficult problem requires a just balancing of various factors. If our motto is to be, "Each for himself and the devil take the hindmost", then want will be the portion of the least active or the least fortunate, and our civilization will be disfigured by those extremes of wealth and poverty, of comfort and despondency, which have defaced our history in the past, and which a proper understanding of human dignity will roundly condemn.

But if the motto is to be that each citizen is entitled, whatever his own effort or deserts (sic), to a maintenance which will suffice without labour; in other words, that utter security in the economic sense is our divinely allotted portion; all incentive to effort will vanish and we shall become a race ready for the destroyer.

We would need to be blind not to have noticed already in this war the corroding effect of a generation of Government paternalism, of a political tradition of pandering and promises, of a growing belief that life owes the individual the fullest protection and security while the individual owes life nothing at all. We are threatened by the dry-rot of social and political doctrines which encourage the citizen to lean on the State, which discourage thrift, which despise as reactionary those qualities of self-reliance which pioneered Australia.

For a generation in Australia many of us have not been training for the battle of life, but have been disposed to sit back, to rest on our laurels, to leave the struggle to others - in particular, as we are now grimly reminded, to the Germans and the Japanese.

If then freedom from want means an absolutely guaranteed material life "come rain, come fine", it should not be welcomed by us, for it would surely mean national inertia and decadence. When the poet said, "for we all know security is mortal's chiefest enemy", his statement, odd as it sounds at first, had truth in it.

Should we then reject Roosevelt's third freedom - freedom from want?

Not at all!! We should and we shall struggle for it, but we should seek to understand what it means and what it involves. The President is not so superficial as to think that any freedom once purchased may be enjoyed for ever without labour and without sacrifice. Freedom is not a commodity you buy over a counter. It is a principle of life. It must be strong to resist its enemies. It is a source of power, not something passive or dead. My right to be free imposes on me obligations of the most absolute kind to defend my freedom. And so if I am to have freedom from want I must pay the price of that freedom. I must work and strive. In the seat of my brow must I earn bread.

Thus it is that freedom from want does not mean paid idleness for all. The country has great and imperative obligations to the weak, the sick, the unfortunate. It must give to them all the sustenance and support it can. We look forward to social and unemployment insurances, to improved health services, to a wiser control of our economy to avert if possible all booms and slumps which tend to convert labour into a commodity, to a better distribution of wealth, to a keener sense of social justice and social responsibility. We not only look forward to these things, we shall demand and obtain them.

To every good citizen the State owes not only a chance in life but a self-respecting life. But this does not obscure the fact that the State cannot and must not put a premium on idleness or incompetence. It must still offer rewards to the enterprising. It must at all times show that security is to be earned, to be merited, and is not to fall, like manna, from heaven.

I know that it is or was fashionable to speak of the new order which is to follow the war as if it will represent a sort of golden age of long life, reduced effort, high incomes and great comfort. It is a pleasing picture, but truth requires us to admit that it is probably false. Long years of the ruin and waste of war must be paid for. We shall work harder than before the war, not less. Most of us shall carry burdens greater than those we were accustomed to bear before the war. Materially we may well - as a nation and as a race - be poorer.

But all this will be more than compensated for by the facts that our sufferings and victory will have preserved our spiritual freedom, that our goods will be more justly shared, and that a better recognition of human values will have quickened our sense of human responsibility.

But let me say this in conclusion, that if to most or many of us the war is just an excuse for getting and spending more money, while the new order of our dreams is just a vista of an easy-going and comfortable majority supplied and fed by a laborious minority, we shall most assuredly lose the war, and the new order will be made in Berlin.

Roosevelt's freedom from want is therefore not a fixed and guaranteed state. It promises the just reward for the good citizen. Properly seen, it is not part of a gospel of ease, but calls us to action.

10 July, 1942

Chapter 6 - The Four Freedoms: Freedom from Fear↩

When the President made freedom from fear one of his four freedoms for which the Allies are fighting, he no doubt had in mind freedom from international crime which cast a shadow over the world for years before the war actually broke out.

How are we to win freedom from this kind of fear?

First, by utterly defeating the Axis Powers. The criminal must be resisted and defeated if honest men are to sleep quietly in their beds. And "utterly defeated" means what it says. No compromise, no partial victory will do. However many years of struggle it may mean for us in our generation, there must be no peace without complete victory. A half-won peace would be no better than an armed neutrality. Fear would continue. The volcano would smoke and rumble and no man would feel safe.

It is perhaps easier to say "no peace without complete victory" than it will be to live up to it. We shall all grow terribly weary, and sometimes sick at heart. We shall from time to time find ourselves looking back to those earlier days of peace which, in retrospect, will look so sunny and carefree. But we shall have to conquer weariness and look and move ever forward. For upon our complete victory the future of our race and of the world will assuredly depend.

It is a hard doctrine but a true one that Germany and Japan, the arch law-breakers, the dark angels of fear, must be made to know the whole anguish of war and learn the salutary lessons of defeat. Too often in modern times has war been to Germany an expedition of power and glory on other people's soil. She must know what it means on her own. She must be made to realise that war does not pay; that crime leads to punishment; that the rights of the world are greater than those of the German Empire.

And so of Japan. She, too, has fought her wars in Manchuria and China and the East Indies, and must learn the grim lesson that war comes home.

Second, when victory has come, how is the peace to be kept? For if it is not kept, fear will revive, and the grievous burden of armaments will once more bear down men's minds. Do not let us try to answer this question dogmatically, because we are as yet a long way from winning the war and nobody can foresee the exact shape or even the vague outline of the post-war problem.

But meanwhile, certain things are worth remembering and thinking about. Why did the League of Nations fail to prevent war? Was it because the United States of America stood aloof? Perhaps that was part of the reason. The league, with the United States in and active, would have been much more like a League of Nations and much less like a partial league of some nations.

But that is not the fundamental reason for the league's failure. I am convinced that it failed because it never succeeded in being more than an alliance for certain purposes between certain nations who retained their full sovereignty, their own policies, their own armies and navies and air forces, and prides, and ambitions.

The idea of a League of Nations was that international law should prevail among nations just as our domestic laws prevail inside our own boundaries. But men live peaceably, and for the most part law-abidingly, inside their own countries for three main reasons: Each citizen gives up his own absolute individual sovereignty in favour of the greater sovereignty of the State and the greater average security and freedom which will result from such sacrifice. It is only in a state of anarchy that men claim absolute sovereignty for themselves. Next, each citizen gives up the right to defend his own security by armed force and in return gets force used as an instrument of the State. In other words, private bodyguards become public police. And finally, the great majority of citizens inside a country have an instinct to obey the law, and that instinct has, as a rule and with no doubt certain setbacks, grown in strength with time.

Now, this third reason will not for many years apply to nations as it does to men. But can the first two?

Would you, if you were in charge of our affairs at the end of the war, be willing for us to enter a League of Nations which was a sort of super-State and which could give us orders?

Would you be agreeable to complete national disarmament, permitting perhaps a small force to restrain domestic violence, and the putting of all armed forces into the hands of the super-

State - the League of Nations? The Royal Navy, the Royal Air Force and so on, would disappear. The League of Nations, on a sort of international federal system, would keep the peace while the constituent nations attended to their civil affairs.

If you tell me that this sounds fanciful, I am bound to agree. The difficulties in the way of it are enormous. Our deep-seated national instincts, traditions, may make it impossible. "What?" we shall say, "A sovereign people abandoning some of their own sovereignty?

And yet we must think earnestly about it, because the alternative to a real League of Nations with real power - and no League of Nations can have real power if all its members are themselves armed to the teeth - is the old system of military alliances, nations being grouped and balanced according to their understanding of their mutual interest. And while nations A, B and C are allies in one group and nations D, E and F allies in another, we can never be free from international fear. It may be that such a system is the only one which is practicable in this world of men, but if it is there can be no guarantee of peace.

Once more I point out that I am not professing to make answers. I cannot see the future. The world may come out of this struggle so nauseated by the destruction and beastliness of war tht the most revolutionary ideas on national status will be accepted with quick relief. But, on the other hand, we may come out with such detestation of everything that Germany has stood for that we shall refuse to admit her to any society of nations, least of all one in which we are a relatively unarmed member.

But the point is that, whatever the answer is to be, we shall make it at the right time and place more intelligently if we face up in our thinking to the basic fact that freedom from international fear will require more than a striking phrase, more even than a passionate longing and belief. It will require some international machinery, the blue-prints of which will demand the best brains of every nation.

But governments may be restrained from war not only by force from without but by pressure from within. As Field Marshal Smuts has said, "The individual is basic to any world order that is worth while." If the individual, as in the past generation, neglects politics - except as a means of obtaining some selfish end - then the people will at times of crisis be dumb and impotent, and despotic rulers will make war.

I cannot elaborate this theme at present, but if you reflect upon it you will see that it adds the third and vital element to our analysis. We have seen two of them: a passionate longing for peace, and an international machinery for peace. The third is the motive power for the machine: that intelligent citizenship among ordinary men and women which rulers will respect and which will be the greatest enemy of war.

17 July, 1942

Chapter 7 - The Four Freedoms: Freedom from Fear (continued)↩

Last week I spoke to you about the fourth of the President's freedoms - freedom from fear - with particular reference to freedom from international fear and the things which seemed to me to be necessary if we were to get rid of it.

Tonight I want to say something more about the fourth freedom from a different point of view - the local or domestic point of view as distinct from the international. For we must frankly admit that fear has not only been a large and deadly element in international relations. It has also been a recognized and potent instrument of domestic policy. Indeed, a powerful case might be made out for the view that the emotion of fear is the most significant of all the emotions on the field of politics.

Take the case of Germany. The picture so readily conjured up in our minds about living conditions in Germany is one of the shadow of the Gestapo, the spy, the informer, falling across what might otherwise be happy and united homes. When Hitler set up his dictatorship he saw at once that nothing sustains a dictatorship as does fear.

He began a reign which was in every essential particular a reign of terror. Every man knew that though he might be a Nazi in high standing today, he might be the victim of a purge tomorrow. And so fear stalked through the land and produced its own iron discipline. Men's minds were beaten upon by highly organized mass demonstrations which left the minority afraid and silent.

And all this was, in its fashion, good psychology on the part of Hitler, for frightened people are much more pliant instruments and much readier receptacles for notions of hatred and revenge than people who move and have their beings in the brave daylight of a free mind.

Now, we recoil from this kind of thing. Indeed, as the war shows, we are prepared to fight against this kind of thing. But when we do, are we fighting an entirely alien enemy? If we look about us, will we be quite satisfied that fear is not an instrument of policy even in democracy?

Let us reason together quite plainly on this matter because, even if we can never hope at all times and under all circumstances to be entirely courageous, we can at least hope to be completely honest. If honest, must we not admit that fear colours our political and social life profoundly?

Suppose we are a group of politicians compiling a policy for a popular election. Shall we simply say, "These things are right and good for Australia, therefore we shall advocate them", or shall we, if we are really shrewd men - in the popular sense of the word "shrewd" - ask ourselves what we can promise people in exchange for their votes, or wonder hopefully whether on some issue we can frighten the people into voting for us? Every student of political history knows that there have been political elections in Australia won by an appeal to greed and others won by an appeal to fear. And the fact that they were won shows that the politicians did not misjudge the people. You, the people of Australia, have encouraged these practices. Woe betide the member of Parliament who takes a strong line which is not at first blush the line that his electors would have taken!

Indeed, in recent years a great many people calling themselves democrats have discovered and practised the art of what is called "pressure politics", the "pressure" taking the form of hundreds, and in some cases that I can remember thousands, of stereotyped letters signed and sent to members of Parliament, on some particular topic, by their constituents, the usual ending being that "if you do not act in accordance with this view I will do all I can to have you defeated at the next election".

This kind of pressure, much attempted a few years ago, for example, by the Douglas Credit people, really represents an endeavour to exploit the instinct of fear. The hope is that the member of Parliament will be sufficiently spineless to abandon his own reasoned convictions for fear of losing his seat in Parliament.

We may go farther in this examination. It is notorious that many electors believe that the function of their member of Parliament is to ascertain, if he can, what a majority of his electors desire, and then plump for it in Parliament. A more stupid and humiliating conception of the function of a member of Parliament can hardly be imagined. If you want mere phonograph records or sounding boards in Parliament, then phonograph records or sounding boards you shall get - and statemanship will die; and democracy will die with it!!

The true function of a member of Parliament is to serve his electors not only with his vote but with his intelligence. If some problem arises in Parliament about which he has knowledge and to which he has devoted his best thought, how absurd it would be - indeed how dangerous it would be - if he should allow his considered conclusion to be upset by a temporary clamour by thousands of people, most of whom in the nature of things could not have his sources of information, and have probably in any event not thought the problem out at all.

Nothing can be worse for democracy than to adopt the practice of permitting knowledge to be overthrown by ignorance. If I have honestly and thoughtfully arrived at a certain conclusion on a public question and my electors disagree with me, my first duty is to endeavour to persuade them that my view is right. If I fail in this, my second duty will be to accept the electoral consequences and not to run away from them. Fear can never be a proper or useful ingredient in those mutual relations of respect and goodwill which ought to exist between the elector and the elected.

And so, as we think about it we shall find more and more how disfiguring a thing fear is in our own political and social life.

"Men fear the unknown as children fear the dark." It is that kind of fear which too often restrains experiment and keeps us from innovations which might benefit us enormously. It is the fear of knowledge which prevents so many of us from really using our minds, and which makes so many of us ready slaves to cheap and silly slogans and catch-cries. It is the fear of life and its problems which makes so many of us yearn for nothing so much as some safe billet from which risk and its twin brother enterprise are alike abolished.

In time of war it is the absence of fear in individuals and groups which gives dignity and strength to the nation's bearing in the midst of difficulties. It is the presence of fear and the yielding to it which produces hysteria and greed and burden-dodging.

Indeed, when you come to think of it you will see that the belief apparently entertained in some quarters that the people must be kept gloomy if they are to see their duty aright, is in reality a belief that fear is the best emotion for the production of patriotic effort. Nothing could be further from the truth. Patriotism is the product of courage, not of defeatism. Confidence is the product of a brave optimism; to dismiss it as complacency is to misconceive its nature and gravely to misunderstand its supreme value in a time of trial.

If there was one thing outstanding to the eye when I was in England last year, at a time when the country was being battered every night, it was that there were no signs of fear or of gloom.

It is of course true that light minds flutter easily from one extreme to the other. But balanced minds - sensible minds - will not turn readily to extremes. They will see all the difficulties and admit all the dangers; but they will remain cheerful, because they will know that the greatest enemy is neither defeat nor victory, death nor life, but fear.

If freedom from fear is really to be one of the great freedoms enjoyed by mankind, we shall need to prosecute to victory not only our war against Germany and Japan, but a constant war against ourselves.

24 July, 1942

Chapter 8 - Empire Control of an Empire War↩

A great debate has been taking place this week in the House of Commons on various aspects of the war, and in particular on the extent to which it is possible to set up representative machinery for joint control.

You will have noticed that in the course of a notable speech, full of characteristic vigour and a refusal to yield to either fear or clamour, Mr Churchill indicated that he was prepared to give to Australia and New Zealand and to any other dominion desiring it, a limited form of representation in the British War Cabinet, the representative having the right to be heard but not the right to join in the making of decisions. In other words, the dominion representative will listen, discuss, and report back to his own Government. Such a scheme has its merits - great merits - but it stops short of full participation by, for example, Australia in the British War Cabinet.

Unfortunately, a good deal of the discussion of the last few days has been clouded by misunderstanding of Australia's point of view. To listen to some people you would think that Australia - as yet untouched by any enemy shot or bomb - was suffering from a wave of fear and was sending out a sort of S O S to the world. To listen to some others you would think that Australia, whose war effort, notable as it has been, stops far short, man for man, of that of the United Kingdom, was full of resentment against the United Kingdom for not having done for us in the past few years things that we were apparently unwilling to do for ourselves. To listen to others again, you would think that the supreme proof of good Australianism is to conduct all your discussions with Great Britain not only publicly but with galleries full of applauding onlookers.

Quite frankly, I denounce all these views as not only thoroughly un-Australian, but as inimical to the best interest of Australia and of the whole Allied cause in this war. Australians are none the less good Australians because they are unhesitatingly British, and there is no reason to doubt that they will meet whatever attack comes to them with the same courage as that displayed by the many millions of people in Great Britain who have known bombing and attack as almost their daily and nightly portion for a long period of time, during which many of us in Australia have lived happily and peacefully in the sun, and have been able to go regularly to the races and the football.

The real problem which has been under consideration this week should therefore be looked at without any of these absurd accompaniments of exaggeration and excitement which have disfigured some of the speeches of some of the partisans.

I believe that the logically perfect thing in this war would be an Empire Executive sitting in London, and full Empire participation in a Pacific Executive sitting in Washington. I say this because I believe that the voice of Australia is a voice entitled to consideration and respect, and because I am a great believer in personal contact and personal discussion. Discussions "inside the family" should not be conducted for the benefit of the neighbours. They should occur in a family conclave, face to face.

I notice with regret that there is a tendency in the last few weeks for ill-informed persons, either in print or over the air, to suggest that my own Government simply said "yes" to whatever the British Government might have put forward. This is utter nonsense, as the world will learn if and when the communications between Governments can be published. But I confess that when I had occasion to put the strongest views direct to Mr Chamberlain and subsequently to Mr Churchill on various matters affecting Australia I did not feel called upon to rush out and announce either that I was doing it or what I was saying. As the Prime Minister of this country, I should have resented the Prime Minister of Great Britain publicly announcing what he was privately cabling to me, and I did not see why the rule should not operate both ways.

Incidentally, of late there have been constant references to what is understood to be an entirely new system by which the Prime Minister of Australia communicates direct with the Prime Minister of Great Britain and the President of the United State.

Now, the constitutional history of our own country is, even under the present urgent circumstances, of great interest to us, and its contemporary facts might as well be accurately stated.

It is no new thing for the Prime Minister of Australia to communicate direct with the Prime Minister of Great Britain. To my own knowledge Mr Lyons did it many times when he was Prime Minister. Equally, I did it many times myself, both with Mr Chamberlain and Mr Churchill, by direct Prime Minister to Prime Minister cables, without the intervention of the Dominions Office, without any red tape or circumlocution. (I should tell you at once that Mr Curtin himself has not in any way claimed that any such communications are novel, but some of his more ardent followers have apparently imagined that they are.) Again, a direct communication between the Prime Minister of Australia and the President of United States is not novel. For all I know, my predecessor engaged in it. I certainly did on at least one notable occasion in 1940, when France was on the point of collapse.

If any Australian imagines that any Prime Minister of this country would allow circumstances of precedent or red tape to stand in the way of the most direct statements to other people by him, that person is a stranger to the whole modern tradition of Australian Government.

Now, you will be able to make up your own minds as to what you think of this latest move towards giving Australia a representative voice in Empire councils. I may perhaps best help you by sketching very briefly the existing machinery, and I do this because it is far from being well known.

How does the Government of the United Kingdom, engaged in some international discussion, obtain the views of Australia? How does Australia obtain the views of the Government of the United Kingdom?

In various ways. Each day - I am speaking now particularly of the period of the war - the Secretary of State for The Dominions interviews the High Commissioners for the various dominions. He informs them of the discussions that have taken place by the War Cabinet and of the despatches received and sent by the Government. He invites their views. They give them, and he gives his. This is a most useful proceeding, and would be much more useful if the Dominions Secretary were a member of the War Cabinet, which by some curiosity of illogicality, he is not.

Each day the Dominions Office sends circular cables to all the dominions, giving current official news, and almost every day special cables are sent to special dominions about problems which particularly concern those dominions.

While all this is going on in London, each dominion has at its capital a High Commissioner from the United Kingdom. At Canberra we have Sir Ronald Cross, a former British minister of great distinction and ability, and he receives from his Government confidential cables, the substance of which he discusses with the Government of this country.

Periodically, we have the best of all interchanges of ideas when some Prime Minister or minister goes from Australia to Great Britain and meets British ministers on common ground and discusses with them quite frankly problems of common interest.

Now, if you have done me the honour of listening so far, you will at once realize that all this machinery, excellent as it is, is limited by its own nature.

Take the cables. The cable is one of the marvels of modern science and, given the necessary time and space, you can say a great deal in a cable. But the one thing you cannot adequately do by cable is to conduct an argument. The whole thing lacks flexibility. When you receive the other man's cable, instead of seeing him and noting the modulations of his voice, and gathering, as you do, the whole atmosphere of the discussion, you simply have a cold-blooded collection of words put in front of you. With the best will in the world you find yourself saying, "Now, what does he mean by that?" You look at some particular sentence and you say, "Well, that might mean so-and-so, and therefore perhaps I should be guarded in my complete acceptance of it".

These things are the inevitable result of mechanical means of communication.

I tell you quite frankly that when I look back and remember how my distinguished predecessor, Mr Lyons, was abused in Australia because he sent some sort of ministerial delegation to Great Britain practically every year, I almost weep, because if I am certain of one thing, it is this - that these repeated, regular, personal contacts have been the best possible things for Australia and the best possible thing for the British Empire. If Mr Lyons had taken a foolish, parochial view of this problem, the view point of our country would be much less understood at Whitehall than it is at this moment.

But it has been said in London that while Australia would like this kind of personal Cabinet representation, Canada and South Africa are indifferent to it. Well, it is not for Australia to sit in judgement upon the views of either Canada or South Africa. Each of these great dominions has its own problems and its own point of view. Each of them is to be respected and understood by us. But when all the discussion is over we shall go back to the proposition that, whatever they may want - and that is for them to say - we have most urgently desired an effective voice, at the time when decisions are being made, in the place where those decisions will be taken.

This is not to say that we distrust Great Britain. The expression of my views is, above all, not to be taken as lending any countenance whatever to the miserable grumbling which goes on in certain quarters about the British and what the British are doing in this war. Quite bluntly, when we do as much in this war as the people of Great Britain, we shall have some occasion to grumble - if indeed we feel like it under those circumstances.

I am, like most of you, enthusiastically for the British character of this great Commonwealth of ours. But the truth is that this British character will be best maintained by giving all the adult members of the family an effective voice in the family policy. There is nothing anti-family in that; on the contrary, it is the best way to wage a family war against the marauding outsider.

Additional note

Events have moved a good deal since this broadcast was delivered but it is included because it may still have some significance

30 January, 1942

Chapter 9 - What the British are doing in this War↩

It would be useless to pretend that Australia is not in more acute danger today than she has ever been before. It is equally clear that, having regard to the rapid Japanese progress in the Far East and her great present superiority in the air and on the water, our own unaided defences are not all that we would desire.

In brief, we have reached a point where we must call upon ourselves for the last ounce of man power and material production, and when we are entitled to look also to Great Britain and to the United States for the greatest and quickest assistance within their power.

Tonight, I want to try to clear up any misconceptions that may arise from some of the circumstances attending our appeal to Great Britain.