Images of Liberty and Power

[Updated June 12, 2011]

14. Tax Return Filing Day and the Tax Eaters

|

Honoré Daumier, “Gargantua” (1831)

[See larger image 1400px] |

Introduction

In the United States April 15 is the day all tax returns must be filed (April 18 in 2011 because of a public holdiay for federal workers). In honour of this important day we have gathered several illustratons and quotations which explore the idea that society is divided into two groups: that of the net tax "consumers" (or tax "eaters" as they are sometimes called) and that of the net tax "payers". These two groups have opposite interests and are therefore in conflict with each other: the tax "eaters" wanting to maintain or even increase their "food intake" and the tax payers wanting to minimize or even eradicate the amount they have to pay.

A recurrent theme in classical liberal thought both in Europe and America is the notion that those who benefit from taxes, whether by working for the state or receiving state funded subsidies and grants, form a separate group with distinct interests from those who pay the taxes from their earnings or savings. In the 19th century James Mill (the father of John Stuart) distinguished between those who "pillage" and those who are "pillaged" and this idea was an important component in the political thought of the "philosophic radicals". The English radical John Wade made this idea a key part of his analysis in his Black Book in which he listed all the beneficiaries of government subsidies in Britain in the 1820s and 1830s. In a cartoon which accompanied the 1835 edition he showed Gulliver (as the British taxpayer) bound and tied on the ground by government officials and tax recipients (as the Lilliputians) who rifle his pockets. Another depiction of this same idea was provided by the French cartoonist and caricaturist Honoré Daumier in "Gargantua" (1831) in which King Louis Philippe is shown as a classic example of the "tax eating" ruler. By the 1840s the French liberal political economist Frédéric Basiait (1801-1850) had developed these ideas into a more sophisticated analysis of what he termed "legal plunder." His planned "History of Plunder" never eventuated because of his premature death in 1850. All we have is a sketch of what he planned to write on this interesting topic. On the other side of the Atlantic the Southern agrarian Jeffersonian republican John C. Calhoun (1782-1850) concluded in a very similar fashion in his *Disquisition on Government* (1843-1848) that "the necessary result, then, of the unequal fiscal action of the government is, to divide the community into two great classes; one consisting of those who, in reality, pay the taxes, and, of course, bear exclusively the burthen of supporting the government; and the other, of those who are the recipients of their proceeds, through disbursements, and who are, in fact, supported by the government; or, in fewer words, to divide it into tax-payers and tax-consumers."

On the Online Library of Liberty we have collected a number of quotations which make this and simialr points about "Taxation":

- (10 April, 2011) Mises on the public sector as “tax eaters” who “feast” on the assets of the ordinary tax payer (1953)

- (24 January, 2011) Spooner on the difference between a government and a highwayman (1870)

- (18 January, 2011) Knox on how the people during wartime are cowered into submission and pay their taxes “without a murmur” (1795)

- (18 August, 2009) Lysander Spooner argues that according to the traditional English common law, taxation would not be upheld because no explicit consent was given by individuals to be taxed (1852)

- (13 July, 2009) Thomas Paine responded to one of Burke’s critiques of the French Revolution by cynically arguing that wars are sometimes started in order to increase taxation (“the harvest of war”) (1791)

- (9 March, 2009) Frédéric Bastiat on the state as the great fiction by which everyone seeks to live at the expense of everyone else (1848)

- (11 August, 2008) Adam Smith claims that exorbitant taxes imposed without consent of the governed constitute legitimate grounds for the people to resist their rulers (1763)

- (28 July, 2008) Alexander Hamilton denounces the British for imposing “oppressive taxes” on the colonists which amount to tyranny, a form of slavery, and vassalage to the Empire (1774)

- (26 May, 2008) Jefferson tells Congress that since tax revenues are increasing faster than population then taxes on all manner of items can be “dispensed with” (i.e. abolished) (1801)

- (4 October, 2007) Frédéric Bastiat and the state as “la grande fiction à travers laquelle Tout Le Monde s’efforce de vivre aux dépens de Tout Le Monde (1848)

- (14 March, 2007) William Graham Sumner reminds us never to forget the “Forgotten Man”, the ordinary working man and woman who pays the taxes and suffers under government regulation (1883)

- (5 March, 2007) Frank Chodorov argues that taxation is an act of coercion and if pushed to its logical limits will result in Socialism (1946)

- (28 November, 2005) John C. Calhoun notes that taxation divides the community into two great antagonistic classes, those who pay the taxes and those who benefit from them (1850)

- (11 July, 2005) David Ricardo considered taxation to be a “great evil” which hindered the accumulation of productive capital and reduced consumption (1817)

- (21 March, 2005) Thomas Hodgskin noted in his journey through the northern German states that the burden of heavy taxation was no better than it had been under the conqueror Napoleon (1820)

- (24 January, 2005) Thomas Jefferson boasts about having reduced the size of government and eliminated a number of “vexatious” taxes (1805)

We think those quotes by Calhoun and Mises deserve to be reproduced below because they are particularly insightful.

John C. Calhoun (1782 – 1850) notes that taxation divides the community into two great antagonistic classes, those who pay the taxes and those who benefit from them (1850). In an extended critique of The Federalist, the pre-Civil War Southern political philosopher John C. Calhoun argued that any system of taxation inevitably divided citizens into two antagonistic groups - the net tax payers and the net tax consumers [see complete quote here]:

Few, comparatively, as they are, the agents and employees of the government constitute that portion of the community who are the exclusive recipients of the proceeds of the taxes. Whatever amount is taken from the community, in the form of taxes, if not lost, goes to them in the shape of expenditures or disbursements. The two—disbursement and taxation—constitute the fiscal action of the government. They are correlatives. What the one takes from the community, under the name of taxes, is transferred to the portion of the community who are the recipients, under that of disbursements. But, as the recipients constitute only a portion of the community, it follows, taking the two parts of the fiscal process together, that its action must be unequal between the payers of the taxes and the recipients of their proceeds. Nor can it be otherwise, unless what is collected from each individual in the shape of taxes, shall be returned to him, in that of disbursements; which would make the process nugatory and absurd. Taxation may, indeed, be made equal, regarded separately from disbursement. Even this is no easy task; but the two united cannot possibly be made equal.

Such being the case, it must necessarily follow, that some one portion of the community must pay in taxes more than it receives back in disbursements; while another receives in disbursements more than it pays in taxes. It is, then, manifest, taking the whole process together, that taxes must be, in effect, bounties to that portion of the community which receives more in disbursements than it pays in taxes; while, to the other which pays in taxes more than it receives in disbursements, they are taxes in reality—burthens, instead of bounties. This consequence is unavoidable. It results from the nature of the process, be the taxes ever so equally laid, and the disbursements ever so fairly made, in reference to the public service…

The necessary result, then, of the unequal fiscal action of the government is, to divide the community into two great classes; one consisting of those who, in reality, pay the taxes, and, of course, bear exclusively the burthen of supporting the government; and the other, of those who are the recipients of their proceeds, through disbursements, and who are, in fact, supported by the government; or, in fewer words, to divide it into tax-payers and tax-consumers.

But the effect of this is to place them in antagonistic relations, in reference to the fiscal action of the government, and the entire course of policy therewith connected. For, the greater the taxes and disbursements, the greater the gain of the one and the loss of the other—and vice versa; and consequently, the more the policy of the government is calculated to increase taxes and disbursements, the more it will be favored by the one and opposed by the other. The effect, then, of every increase is, to enrich and strengthen the one, and impoverish and weaken the other. This, indeed, may be carried to such an extent, that one class or portion of the community may be elevated to wealth and power, and the other depressed to abject poverty and dependence, simply by the fiscal action of the government; and this too, through disbursements only—even under a system of equal taxes imposed for revenue only. If such may be the effect of taxes and disbursements, when confined to their legitimate objects—that of raising revenue for the public service—some conception may be formed, how one portion of the community may be crushed, and another elevated on its ruins, by systematically perverting the power of taxation and disbursement, for the purpose of aggrandizing and building up one portion of the community at the expense of the other. That it will be so used, unless prevented, is, from the constitution of man, just as certain as that it can be so used; and that, if not prevented, it must give rise to two parties, and to violent conflicts and struggles between them, to obtain the control of the government, is, for the same reason, not less certain.

Ludwig von Mises (1881-1973) on the public sector as “tax eaters” who “feast” on the assets of the ordinary tax payer (1953). In a similar fashion to John C. Calhoun’s division of the world into net “tax-consumers” and net “tax-payers”, the Austrian economist Ludwig von Mises (1881-1973) distinguished between the ordinary citizens who paid taxes and the public sector entities like the New York subway which “consumed” the taxes paid by the former. This is a classic example of what Mises in 1945 termed “the clash of group interests” [see the full quotation here]:

Derailment of State Railroads (1953)

The financial embarrassment of the main European countries is predominantly caused by the bankruptcy of the nationalized public utilities. The deficit of these enterprises is incurable. A further rise in their rates would bring about a drop in total net proceeds. The traffic could not bear it. Daily experience proves clearly to everybody but the most bigoted fanatics of socialism that governmental management is inefficient and wasteful. But it is impossible to sell these enterprises back to private capital because the threat of a new expropriation by a later government would deter potential buyers.

In a capitalist country the railroads and the telegraph and telephone companies pay considerable taxes. In the countries of the mixed economy, the yearly losses of these public enterprises are a heavy drain upon the nation’s purse. They are not taxpayers, but tax-eaters.

Under the conditions of today, the nationalized public utilities of Europe are not merely feasting on taxes paid by the citizens of their own country; they are also living at the expense of the American taxpayer. A considerable part of the foreign-aid billions is swallowed by the deficits of Europe’s nationalization experiments. If the United States had nationalized the American railroads, and had not only to forgo the taxes that the companies pay, but, in addition, to cover every year a deficit of several billions, it would not have been in a position to indemnify the European countries for the foolishness of their own socialization policies. So what is postponing the obvious collapse of the Welfare State in Europe is merely the fact that the United States has been slow and “backward” in adopting the principles of the Welfare State’s “new economics”: it has not nationalized railroads, telephone, and telegraph.

Yet Americans who want to study the effects of public ownership of transit systems are not forced to visit Europe. Some of the nation’s largest cities—among them Detroit, Baltimore, Boston, San Francisco—provide them with ample material. The most instructive case, however, is that of the New York City subways.

New York City subways are only a local transit system. In many technological and financial respects, however, they surpass by far the national railroad systems of many countries. As everybody knows, their operation results every year in a tremendous deficit. The financial management accumulates operating deficits, planning to fund them by the issuance of serial bonds. Only a municipality of the bigness, wealth, and prestige of New York could venture on such a policy. With a private corporation financial analysts would apply a rather ugly word to its procedures: bankruptcy. No sane investor would buy bonds of a private corporation run on such a basis.

Incorrigible socialists are, of course, not at all alarmed. “Why should a subway pay?” they are asking. “The schools, the hospitals, the police do not pay; there is no reason why it should be different with a transit system.” This “why” is really remarkable. As if the problem were to find an answer to a why, and not to a wherefrom.

There is always this socialist prepossession with the idea that the “rich” can be endlessly soaked. The sad fact, however, is that there is not enough left to fill the bottomless barrels of the public treasury. Precisely because the schools, the hospitals, and the police are very expensive, the city cannot bear the subway deficit. If it wants to levy a special tax to subsidize the subway, it will have to tax the same people who are supposed to profit from the preservation of the low fare.

The other alternative is to raise the fare from the present [1953] level of ten cents to fifteen cents. It will certainly be done. And it will certainly prove insufficient. After a while a rise to twenty cents will follow—with the same unfavorable result. There is no remedy for the inefficiency of public management. Moreover there is a limit to the height at which raised rates will increase revenue. Beyond this point further rises are self-defeating. This is the dilemma facing every public enterprise.

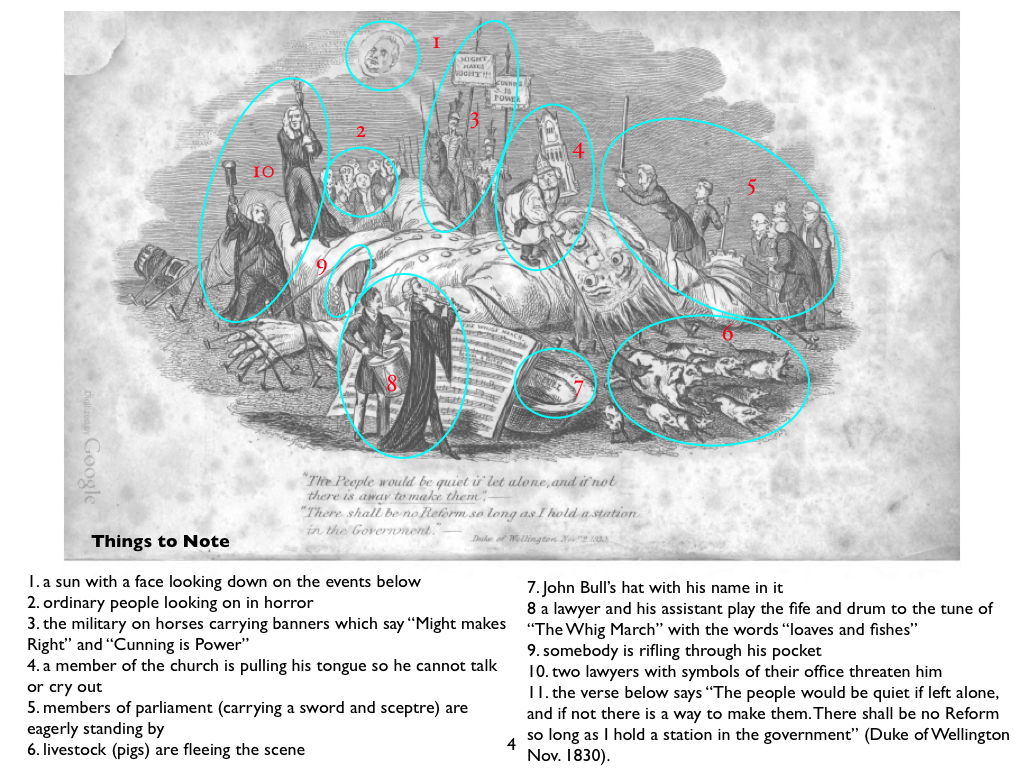

Honoré Daumier's "Gargantua" the Tax Eater (1831)

[Above] This caricature from 1831 shows how Daumier thought ordinary people were exploited by the ruling elites through taxation and regulation. It was created at a time when agitation for democratic reforms were strong in both England and France and was drawn by the French republican artist Honoré Daumier for a satirical magazine in 1831. It depicts a fat and pear-shaped King Louis Philippe as a "tax eater" (the "Gargantua" from Rabelais' novel) who takes from the ordinary people and gives privileges to the ruling elite. The taxpayers (to the right) are loading baskets full of their tax money which are carried up a ramp into the king’s open mouth. Some well dressed citizens gather around his feet to collect the coins which fall to the ground. From the king’s commode (or toilet) fall official documents which grant various privileges and honours to those waiting below, before they rush off to the National Assembly in the backgrund. For making this drawing Daumier spent 6 months in prison for offending the king.

In France there was agitation to enlarge the franchise and to weaken the power of the political elites from the aristocracy, the landowning and commercial classes, and the church. With the restoration of the monarchy in 1815 after the fall of Napoleon, the Bourbons were restored to the monarchy (Louis XVIII and then Charles X) and introduced a very limited franchise (barely 100,000 voters). Attempts by Charles X to limit freedom of speech and to compensate nobles for the loss of their land during the Revolution led to a popular uprising in July 1830 and the coming to power of a junior member of the Bourbon royal family, Louis Philippe who ruled from 1830-1848. The political satirist and republican Honoré Daumier (1808-1879) thought that very little would change under Louis Philippe and so satirized the king (whom he often drew in the shape of a pear) in many etchings such as “Gargantua” (1831) which shows the people still having to pay for the privileges of the elite through their taxes. Daumier spent 6 months in jail for this depiction of the king.

In this caricature King Louis Philippe is portrayed

as the giant Gargantua (from Rabelais’ novel Gargantua and Pantagruel (1532)).

The taxpayers (to the right) are loading baskets full of their tax money

which are carried up a ramp into the king’s open mouth. Some well dressed

citizens gather around his feet to collect the coins which fall to the ground.

From the king’s commode fall official documents which grant various privileges

and honours to those waiting below, before they rush off to the National

Assembly. Things to Note [see image below for details]:

-

in the distance we can see sun-lit buildings which suggest productive economic activities - windmills and a port

-

the taxpayers have been gathered to empty their pockets into baskets - note the man in rags putting his money in the basket and the hagged women with a baby sitting down, suggesting poverty

-

Daumier has drawn an unflattering picture of the king being fed his tax money - literally a “tax eater” (for this HD spent time in prison)

-

some well dressed men (with tricorn hats) collect coins which have fallen to the ground

-

from the king’s commode fall documents granting honours and privileges

-

with these documents in hand the men rush off to the National Assembly which is shrouded in darkness

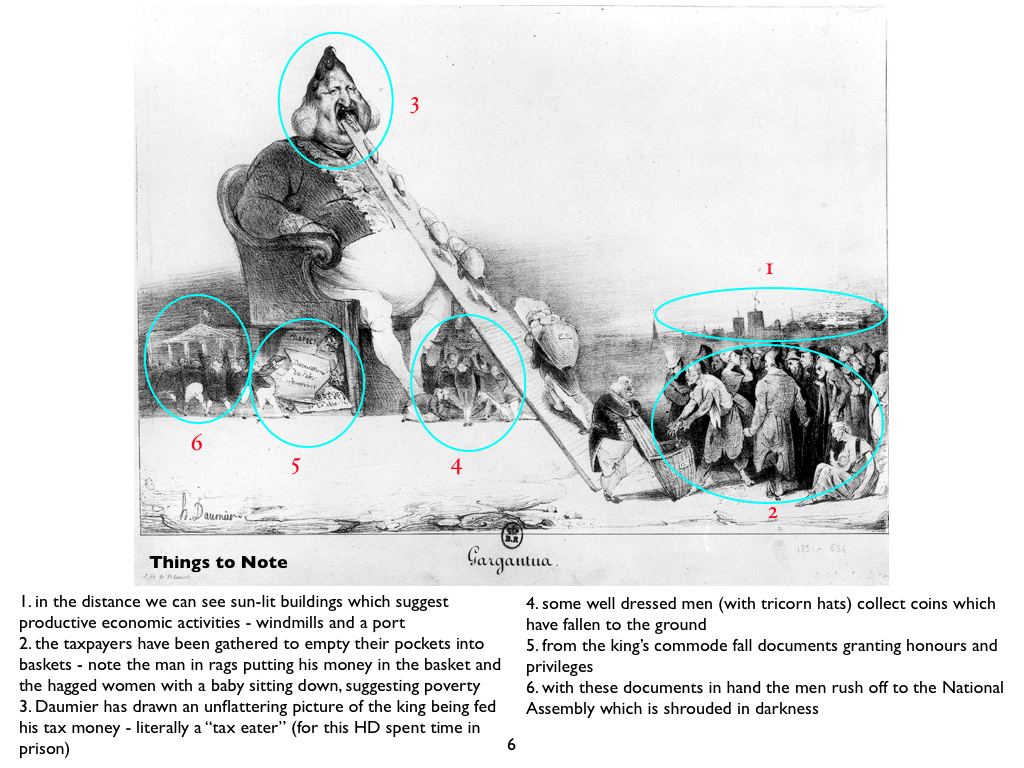

John Wade and "The Tax Stealers going through Gulliver's Pockets" (1835)

|

John Wade (1788-1875) was active in British

reform circles throughout the 1820s. This group included people such as James

Mill (the father of J.S. MIll) and other “Philosophical Radicals”. One of

their key demands was to enlarge the franchise to include better representation

of the new cities which had grown during the industrial revolution and to

reduce the number of “rotten boroughs” which were very small electorates

in the countryside which were dominated by the local landowners. The First

Reform Act of 1832 increased the size of the electorate by over 50%, enabling

some 1/6 of the English population to vote. One reason why reformers like

John Wade wanted a larger electorate was to enable them to protect themselves

from the aristocratic and wealthy elites who benefited from the large number

of government pensions, subsidies, monopolies, and other privileges which

control of Parliament gave them. He chronicled these abuses in several editions

of The Extraordinary Black Book, or Corruption Unmasked (1820-1835).

In the image above, which appeared in the 1835 edition of The Extraordinary

Black Book,

John Bull (i.e. the British people) has been

captured and tied down (like Gulliver in Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels (1726)

by the Lilliputians, who in this case are figures representing the army, the

church, members of parliament, and the judiciary. The Lilliputians taunt him

and rifle his pockets to steal his money. Things to Note (see

details below):

-

a sun with a face looking down on the events below

-

ordinary people looking on in horror

-

the military on horses carrying banners which say “Might makes Right” and “Cunning is Power”

-

a member of the church is pulling his tongue so he cannot talk or cry out

-

members of parliament (carrying a sword and sceptre) are eagerly standing by

-

livestock (pigs) are fleeing the scene

-

John Bull’s hat with his name in it

-

a lawyer and his assistant play the fife and drum to the tune of “The Whig March” with the words “loaves and fishes”

-

somebody is rifling through his pocket

-

two lawyers with symbols of their office threaten him

-

the verse below says “The people would be quiet if left alone, and if not there is a way to make them. There shall be no Reform so long as I hold a station in the government” (Duke of Wellington Nov. 1830).